Abstract

Background

There is an urgent need to explore and utilize naturally occurring products for combating harmful agricultural and public health pests. Secondary metabolites in the leaves of the Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus altissima L. have been reported to be herbicidal and insecticidal. The mode of action, however, of the active compounds in A. altissima are not understood. In this paper, we report the chemical characteristics of the herbicidal and insecticidal components in this tree, and will discuss the effect of light on the bioactivity of the active components.

Results

Extracts from the fresh leaves of A. altissima showed a strong plant germination/growth inhibitory effect in laboratory bioassays against alfalfa (Medicago sativa). The effect was dose-dependent. The growth inhibitory components were in the methylene chloride soluble fraction of the extract. The effect was greater in the light than in the dark. Other fractions had plant growth enhancing effect at lower concentrations. The extract was slightly insecticidal against yellow fever mosquito larvae (Aedes aegypti).

Conclusions

The extract or its semi-purified fractions of A. altissima were strong plant growth inhibitors, therefore good candidates as potential environmentally safe and effective agricultural pest management agents. The finding that light affects the activity will be useful in the application of such natural products.

Background

Plants, insects, and other organisms have co-existed for more than three hundred million years. During this time, plants have been under a continuous selection pressure from predators and numerous environmental factors. Due to their lack of mobility, plants must rely on both physical and chemical defense mechanisms such as producing various toxic metabolites to survive the predatory attacks of other organisms such as insects, bacteria, and fungi, and to adequately compete with other plant species for light and nutritional resources. The defense chemicals or secondary metabolites of plants can serve several types of functions. They can be insecticidal [1-4], or antimicrobial to bacteria, fungi and viruses [5-8]; some are also herbicidal [9,10], and some possess other types of biological activities [11,12]. These beneficial, bioactive chemical substances are found in abundance in plant species. Of the 5–10% of the higher plants which have been phytochemically analyzed, more than 30,000 secondary metabolites have been reported [13].

Due to the public concern over the toxicity and environmental impact of conventional synthetic pesticides, exploitation and utilization of naturally occurring products in order to combat harmful agricultural and public health pests have been increasingly the focus of researchers, environmentalists and industry. Because "natural" pesticides, or pesticides derived from natural products, support both crop production and the environment by being effective in pest control, less toxic to non-target organisms and biodegradable at the same time, they may be safer than synthetic pesticides. Repeated use of a single synthetic pesticidal ingredient can result in resistance amongst the target populations; whereas, natural products in plant defense mechanisms often consist of a variety of toxins which make adaptation of the predator unfavorable [13].

Ailanthus altissima is a plant in the family Simaroubaceae. It grows aggressively in harsh environments where it invades abandoned fields or cracked city sidewalks. The invasive success of A. altissima, or Tree of Heaven, can be attributed to its physiological characteristics such as sexual and asexual reproductive behavior [14,15], and to the phytotoxic compounds found in its roots and leaves [16-19]. Heisey [15,20] found that the water extract of A. altissima leaves inhibites the growth of Lepidium satium (garden cress), and the activity of the water extract was not affected by further extraction with methylene chloride, but was greatly affected by extraction with methanol. He concluded that the active herbicidal component is hydrophilic and therefore is present in the water solution. A. altissima extract has also been reported to have insecticidal activities. Secondary compounds of A. altissima have been used to control insects such as Pieris rape, Platyedra gussypiella, and aphids [19]. The quassinoids (degraded triterpenes), ailanthone, amarolide, acetyl amarolide, and 2-dihydroxyailanthone, are some of the bioactive products present in A. altissima chemical make-up [21,22]. A. altissima has also been used medicinally, to treat tumors and amoebic dysentery [23]. Lin et al.[24] have identified ailanthone as the principal plant growth inhibitor in A. altissima against Brassica juncea, Eragrostis tef and Lemna minor.

On the other hand, certain naturally occurring compounds are more bioactive in the light [10,25]. Polyacetylene and thiophene compounds such as cis-dehydromatricaria ester and α-terthienyl are two typical examples. These compounds themselves may have no or very low bioactivity, but when light, especially UV-A light, is present they show strongly enhanced bioactivity [10,25].

There are no reports on the growth regulatory effect of the A. altissima related compounds or extracts, and the role of light on the effect has not been studied. The primary goal of this project is to reconfirm the observation of the growth inhibitory effect of A. altissima under controlled laboratory conditions, and to study the characteristics and the effect of light on the herbicidal and insecticidal activities of the extract.

Results and Discussion

Phytotoxicity of the Ailanthus altissima extract

Although in some reports plant leaves and other parts have been dried and ground before solvent extraction, we chose fresh leaves of A. altissima and a polar solvent methanol in the extraction because most of the bioactive components have been reported to be hydrophilic [15,20]. The plant leaves were cut into small pieces, then soaked or blended in the solvent. No significant difference was found between the two extraction methods in total extractables (Table 1). Data in the right column of Table 1 were used in serial dilutions for the bioassays.

Table 1.

Solid extractables from Ailanthus altissima leaves from two different extraction methods.

| g extractables / 500 g fresh leaves | ||

| fraction | blended | non-blended |

| Fraction A | 8.89* | 7.78 |

| Fraction B | 8.46 | 7.26 |

| Fraction C | 0.16 | 0.15 |

* average of two replicates.

The crude extract of A. altissima leaves showed strong growth inhibition against alfalfa (Medicago sativa) under both light and dark conditions. However, the activity of the extract, as expressed in IC50 (the concentration that inhibits the growth of the alfalfa radicle by 50%), was about 2–3 fold higher when light was present (Table 2). The IC50 of Fraction A was 12.3 ppm in the light, nearly half of the concentration that was needed for the same inhibition in the dark (Table 2). The IC50 of Fraction B in the light and dark were 63.0 ppm and 108.1 ppm, respectively, significantly less toxic than Fraction A. This indicated that the active components might be extracted into methylene chloride (Fraction C). Fraction B had a different effect on the alfalfa seedlings. At lower concentrations, when incubated in the dark, the radicles of the seedlings were elongated, while the photoactivated growth inhibition seemed to happen at higher concentrations (data not shown). Fraction C, the methylene chloride extract, showed the highest inhibitory effect on the growth of M. sativa. The IC50's were 4.7 ppm and 12.8 ppm when the seedlings were incubated in the light and dark, respectively (Table 2). The higher activity of Fraction C indicated that the active components might be more soluble in methylene chloride than what was previously reported [15,20]. It was reported that the active components in water extract were not removable by methylene chloride, and that methylene chloride did not alter the phytotoxicity of the aqueous extract, but methanol did [20]. However, in that study, the methylene chloride extract was not tested for its activity [20]. In our study, we found that Fraction C (methylene chloride extract) had a higher activity against both Lactuca sativa (data not shown) and Medicago sativa (Table 2). Considering fraction C was only 1.2% of the crude extract (Fraction A), we concluded that the major growth inhibitory compounds were in this fraction (Table 1).

Table 2.

The growth inhibitory effect of different extract and fractions of Ailanthus altissima.

| Light | Dark | |||

| fraction | IC50 (ppm) | 95% FL | IC50 (ppm) | 95% FL |

| Fraction A | 12.3 | 8.0–18.8 | 24.1 | 18.4–31.6 |

| Fraction B | 63.0 | 46.2–85.9 | 108.1 | 75.9–154.0 |

| Fraction C | 4.7 | 3.5–6.3 | 12.8 | 9.2–18.0 |

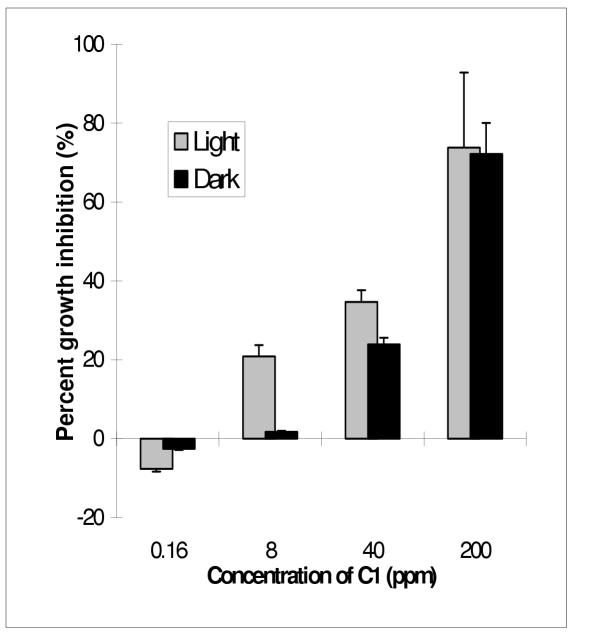

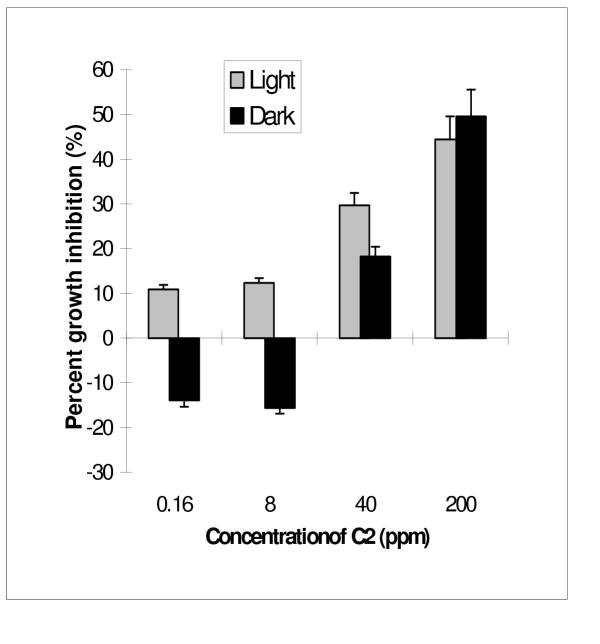

Since methylene chloride extracted the most active ingredients from the methanol/water extract of A. altissima, our focus was shifted to Fraction C. Fraction C was further fractionated into C1, C2, C3 and C4 using preparative TLC. Fraction C4, which had the lowest Rf value showed significantly stronger growth and germination inhibition than the other three fractions of higher Rf values (Table 3). The growth inhibitory effect of C4 was found under both light and dark conditions. The IC50's of C4 against the radicles of M. sativa in the light and dark were 3.2 and 4.2 ppm, respectively (Table 3). Germination of alfalfa seeds was completely stunted by C4 at 200 ppm. IC50's of C1, the least hydrophilic fraction, were 71.8 ppm and 98.5 ppm in the light and dark. However, it was interesting to notice that radicles of seeds treated with lower concentrations of fraction C1 grew significantly longer than those in the control, especially when incubated in the dark (Fig. 1). C2 had the least phytotoxicity. The IC50's of C2 were >200 ppm both in the light and dark. However, C2 had the strongest radicle elongation effect among the 4 fractions. Radicle lengths of alfalfa treated in the dark with C2 at 1.6 and 8 ppm were 13% and 17% longer than those in the control (Fig. 2). Fraction C3 also had slight growth stimulating effects at lower concentrations, and some inhibitory effect at higher concentrations. The IC50's of Fraction C3 were 76.0 ppm in the light and 95.2 ppm in the dark (Table 3).

Table 3.

The growth inhibitory effect of different fractions of the methylene chloride extractables extract from Ailanthus altissima.

| Light | Dark | |||

| fraction | IC50 (ppm) | 95% FL | IC50 (ppm) | 95% FL |

| Fraction C1 | 71.8 | 48.2–107.0 | 98.5 | 80.7–120.3 |

| Fraction C2 | >200 | - | >200 | - |

| Fraction C3 | 76.0 | 50.7–113.9 | 95.2 | 78.8–114.9 |

| Fraction C4 | 3.2 | 2.3–4.3 | 4.2 | 3.2–5.5 |

Figure 1.

Plant growth regulatory effect of Fraction C1 on alfalfa Medicago sativa. (Note the negative inhibition is in fact the enhancement of growth). Error bars are standard deviation of three replicates.

Figure 2.

Plant growth regulatory effect of Fraction C2 on alfalfa Medicago sativa. (Note the negative inhibition is in fact the enhancement of growth). Error bars are standard deviation of three replicates.

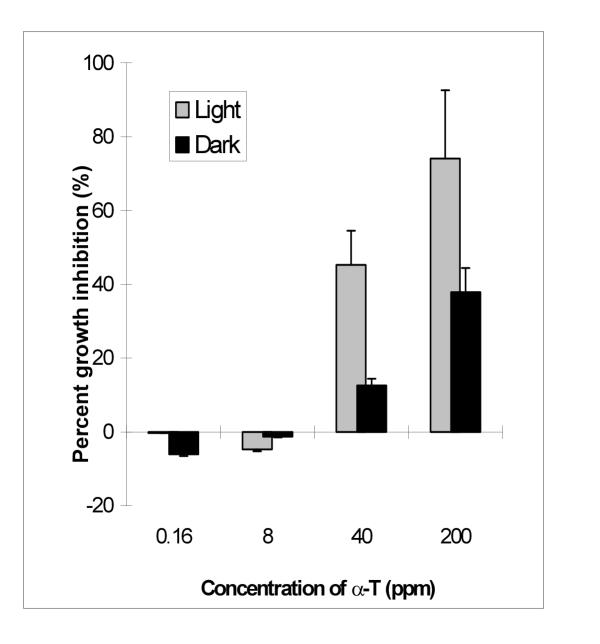

Our results clearly indicated the involvement of chemical factors in the growth inhibitory and stimulating effects of A. altissima against other plants such as alfalfa. Other researchers have isolated ailanthone from of A. altissima and found it herbicidal toward various weeds [24]. Although we did not isolate the individual chemicals responsible for the growth regulatory effect found with our extract and sub-fractions, it was evident that multiple chemicals were involved. Ailanthone may be one of the principal growth inhibitory components in A. altissima, however it may not be the only one. In addition, some chemicals in the extracts of A. altissima showed growth enhancement effect. These two totally different effects indicated possible plant growth regulatory effects, namely, enhance the growth at lower concentrations and inhibit the growth at higher concentrations. Our results also agreed to the finding of Lin et al. [24] that light played an important role in the herbicidal activity of ailanthone. We found that, in most cases, the growth inhibitory effect was stronger in the presence of light. The growth regulatory effect of C1 and C2 was similar to α-terthienyl, a well known naturally occurring photosensitizer (Table 3, Fig. 1,2,3). α-terthienyl showed typical photoactivated inhibition of the growth of M. sativa radicles at high concentration and plant growth stimulation effect at low concentration (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Plant growth regulatory effect of α-terthienyl on alfalfa Medicago sativa. (Note the negative inhibition is in fact the enhancement of growth). Error bars are standard deviation of three replicates.

Insecticidal activity on mosquito larvae

Only Fraction A showed some degree of insecticidal activity against the yellow fever mosquito larvae (Adedes aegypti) (Table 4). The mortalities of the larvae were 100% and 50% after 24 h of exposure to 778 ppm and 195 ppm of Fraction A, respectively. Fraction B and C did not show any toxicity at all concentrations tested. However, compared to α-terthienyl which killed 100% of the mosquito larvae at 0.1 ppm in the light and 1 ppm in the dark (Table 4), the insecticidal activity of the Ailanthus extracts were much less significant than the effect against the growth of plants.

Table 4.

Insecticidal activity of the extracts of Ailanthus altissima against second-instar yellow fever mosquito larvae (Aedes aegypti) 24 h post-treatment*.

| Fraction A | Conc. (ppm) | 0 | 49 | 195 | 778 |

| Mortality (%) | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 | |

| Fraction B | Conc. (ppm) | 0 | 46 | 182 | 726 |

| Mortality (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| Fraction C | Conc. (ppm) | 0 | 38 | 150 | 778 |

| Mortality (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| α-terthienyl | Conc. (ppm) | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0** | - |

| Mortality (%) | 0 | 100 | 100 | - |

*Data are the average of three replicates. ** Tested in dark. The others are in the ambient room light.

Conclusion

Although the extracts of A. altissima were practically non-toxic to the mosquito, the extracts had strong effects on plant growth in the alfalfa assay. The inhibitory effect on plant growth by the crude extract and some sub-fractions was enhanced by the presence of light. Some fractions showed plant growth regulatory effect against the alfalfa by inhibiting the growth of radicle at higher concentrations and enhancing the growth at lower concentrations. These effects of the extracts of A. altissima could lead to a new natural herbicide and plant growth regulators, since these natural products would likely be very biodegradable, thus posing less risk to the environment. Further investigations are needed to isolate the individual chemical(s), and to study their growth inhibitory and enhancing effects.

Materials and Methods

Extracting bioactive components from plants

Leaves and stems of A. altissima were collected from trees less than one year old (July, 1995, Iowa State University Campus, Ames). The leaves were cut to ca. 2.5 cm in length and soaked in certified methanol in a glass container (500 g of fresh leaves in 2750 ml of methanol). This was allowed to sit at room temperature (25°C) for 72 h.

The methanol extract was filtered in vacuo through a Buchner funnel (110 mm diameter) and Whatman #4 filter paper. The filtrate was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at < 40°C to ca. 150 ml until all the methanol evaporated.

The concentrated extract was diluted up to a volume of 500 ml with distilled water in a volumetric flask. Half of the solution, 250 ml (Fraction A), was employed directly into the bioassays on alfalfa and mosquito larvae. The remaining 250 ml was extracted in a separatory funnel by partitioning with methylene chloride (75 ml three times). The combined methylene chloride portion was passed over anhydrous sodium sulfate to remove traces of water. The remaining aqueous layer was evaporated with a rotary evaporator to get rid of any residual methylene chloride, and re-diluted to 250 ml with water and designated Fraction B. The methylene chloride extract was then evaporated to dryness, and the residue was re-dissolved in 250 ml of acetone (Fraction C). Aliquots of all fractions were freeze-dried or dried using rotary evaporator (acetone solution) to get the total extractables, and the concentrations of all samples were calculated based on the dry weight of extractables.

The methylene chloride extract (Fraction C) was further fractionated into four fractions (C1–C4) of different Rf values using preparative thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (0.2 mm, POLYGRAM® SIL G/UV254, Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co, Duren, Germany) and a solvent system: acetone:ethyl acetate = 1:4 (v/v). The Rf values for Fraction C1, C2, C3 and C4 were 1–0.76, 0.76–0.50, 0.50–0.29 and 0.29–0.00, respectively.

α-Terthienyl was purchased from Aldrich Chemical Inc. (Milwaukee, WI). This compound was tested as a standard for photoactivated bioactivities. All other solvents used were of certified grade from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Bioassays

1. Alfalfa seeds test

All extracts or fractions were diluted to 4–5 different concentrations, and tested against the seeds of alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Five ml of each of the water solutions were directly transferred into Fisher disposable Petri dishes (9 cm diam.) that were lined with Whatman #1 filter paper. Distilled water was used as control. For acetone solutions (Fraction C, C1–C4, and α-T), 0.5 ml of each solution was pipetted onto the Whatman #1 filter paper lined in the Petri dish. After allowing acetone to dry for five min in a fume hood, five ml of distilled water was pipetted into the Petri dish. In the control, the same amount of acetone was used instead.

To each treated dish, 10–30 alfalfa seeds were added, and the dishes were covered with the lids. Three replicates were prepared for each dilution and for both light and dark conditions. The dark condition was created by putting the dishes into a cardboard box which was then covered with aluminum foils. The treated seeds were incubated in a greenhouse (25 ± 1°C, r. h. 100%). Water was added as needed to the light treatments to keep them moist. There was no need to add water to the treatments under the dark condition, because they were moist enough by the time the test was terminated. The treated seeds were allowed to germinate and grow for six days. The lengths of radicles were measured and recorded.

2. Mosquito larvae test

The yellow fever mosquito colony (Aedes aegypti) was maintained in the Department of Entomology at Iowa State University. The second-instar larvae were used in the assays. Fractions A and B were diluted with water to three different concentrations: 49, 195 and 778 ppm for Fraction A, and 46, 182 and 726 ppm for Fraction B. At least 10 second-instar mosquito larvae were introduced to 10 ml of each concentration in a glass jar covered with a nylon mesh. Distilled water was used in the control. Fraction C was diluted with acetone to 38, 150 and 778 ppm, and α-terthienyl at 0.1 and 1.0 ppm. The acetone solution (100 μl) was added to 10 ml of water in a glass jar, and allowed acetone to evaporate in a fume hood for 15 minutes before introducing the mosquito larvae. Pure acetone was used in the control for fraction C. All jars were then incubated at room temperature (ca. 23 ± 1°C) for 24 h. The live and dead mosquitoes were then recorded.

The percent growth inhibitory effect was calculated as follows:

Inhibition (%) = (Lcontrol - Ltreatment)/ Lcontrol*100

where Lcontrol is the radicle length of alfalfa seedlings in the control, and Ltreatment is the radicle length of alfalfa seedlings treated with extracts or fractions of the extracts. Probit analysis was used to determine IC50 and 95% FL according to the methods outlined by Finney [26].

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Women in Science and Engineering Program of Iowa State University for partially supporting this project. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Wayne Rowley and Mr. John VanDyk of the Department of Entomology, Iowa State, for providing the mosquito larvae. This is Scientific Contribution #S090 of the Food Research Program, Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada.

Contributor Information

Rong Tsao, Email: caor@em.agr.ca.

Frieda E Romanchuk, Email: frieda.e.romanchuk@bellatlantic.com.

Chris J Peterson, Email: cjpeterson@fs.fed.us.

Joel R Coats, Email: jcoats@iastate.edu.

References

- Rice EL. Allelopathy. Academic Press, Inc, Orlando. 1984.

- Bowers WS, Nishida R. Junocimenes: potent juvenile hormone mimics from sweet basil. Science. 1980;209:1030–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.209.4460.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonhoven LM. Insects and phytochemicals-nature's economy. In: Van Beek TA, Breteler H, editor. Phytochemistry and Agriculture. Clarendon Press, Oxford; 1993. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao R, Coats JR. Starting from nature to make better insecticides. Chemtech, 1995;25:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Oh HK, Sakai T, Jones MB, Longhurst WM. Effect of various essential oils isolated from Douglas fir needles upon sheep and deer rumen microbial activity. Appl Microbiol. 1967;15:777–784. doi: 10.1128/am.15.4.777-784.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell SP, Wiemer DF, Adeiare A. An antifungal terpenoid defends a neotropical tree (Hymenaea) against attack by fungus-growing ants (Atta). Oecologia. 1983;60:321–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00376846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp MS, Burden RS. Phytoalexins and stress metabolites in the sapwood of trees. Phytochem. 1986;25:1261–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)81269-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harbone JB. Introduction to ecological biochemistry. Academic Press, New York. 1988.

- Whittaker RH, Feeny P. Allelochemicals: chemical interactions between species. Science. 1971;171:757–770. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3973.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao R, Eto M. Photo-dependent plant growth inhibitory effect of the naturally-occurring allelochemical cis-dehydromatricaria ester(cis-DME) on lettuce. Chemosphere, 1996;32:1307–1317. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(96)00042-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold AS, Erwin M, Oti J, Browing B. Phytoestrogens: adverse effects on reproduction in California quail. Science. 1976;191:98–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1246602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherst RW, Jones RJ, Schnitzerling HJ. Tropical legumes of the genus Stylosanthes immobilize and kill cattle ticks. Nature, 1982;295:320–321. doi: 10.1038/295320a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink M. Production and application of phytochemicals from an agricultural perspective. In: Wink M, editor. Phytochemistry and Agriculture. Clarendon Press: Oxford; 1993. pp. 171–213. [Google Scholar]

- Pan E, Bassuk N. Effects on soil types and compaction on the growth of Ailanthus altissima seedlings. J Environ Hortic. 1986;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Heisey RM. Evidence for allelopathy by tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima). J Chem Ecol. 1990;16:2039–2055. doi: 10.1007/BF01020515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergen F. A toxic principle in the leaves of Ailanthus. Bot Gaz. 1959;121:32–36. doi: 10.1086/336038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heisey RM, Delwiche CC. A survey of California plants for water-extractable and volatile inhibitors. Bot Gaz. 1983;144:382–390. doi: 10.1086/337387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grainge M, Ahmed S. Handbook of plants with pest-control properties. Wiley, New York. 1988.

- Yang RZ, Tang CS. Plants used for pest control in China: a literature review. Econ Bot. 1988;42:376–406. [Google Scholar]

- Heisey RM. Allelopathic and herbicidal extracts from tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). American J of Botany. 1990;77:662–670. [Google Scholar]

- Casinovi CG, Ceccherelli P, Fardella G, Grandolini G. Isolation and structure of a quassinoid from Ailanthus glandulosa. Phytochem. 1983;22:2871–2873. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97722-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aono H, Koike K, Kaneko J, Ohmoto T. Alkaloids and quassinoids from Ailanthus malabarica. Phytochem. 1994;37:579–584. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(94)85104-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Duke JA. A Field Guide to Medicinal Plants. Houghton Mifflin Co, Boston. 1990.

- Lin LJ, Peiser G, Ying BP, Mathias K, Karasina F, Wang Z, Itatani J, L Green, Hwang YS. Identification of plant growth inhibitory principles in Ailanthus altissima and Castela tortuosa. J Agric Food Chem, 1995;43:1708–1711. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G, Lambert JDH, Arnason T, Towers GHN. Allelopathic properties of α-terthienyl and phenylheptatriyne, naturally occurring compounds from species of Asteraceae. J Chem Ecol. 1982;8:961–972. doi: 10.1007/BF00987662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney S. Probit Analysis. Cambridge University Press Cambridge, United Kingdom. 1971.