Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that is diagnosed largely on clinical grounds due to characteristic motor manifestations that result from the loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. While traditional pharmacological approaches to enhance dopamine levels, such as with l-dopa, can be very effective initially, the chronic use of this dopamine precursor is commonly plagued with motor response complications. Additionally, with advancing disease, non-motor manifestations emerge, including psychosis and dementia that compound patient disability. The pathology includes hallmark intraneuronal inclusions known as Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites that contain fibrillar α-synuclein aggregates. Evidence has also accumulated that these aggregates can propagate across synaptically connected brain regions, a phenomenon that can explain the progressive nature of the disease and the emergence of additional symptoms over time. The level of α-synuclein is believed to play a critical role in its fibrillization and aggregation. Accordingly, nucleic acid–based therapeutics for PD include strategies to deliver dopamine biosynthetic enzymes to boost dopamine production or modulate the basal ganglia circuitry in order to improve motor symptoms. Delivery of trophic factors that might enhance the survival of dopamine neurons is another strategy that has been attempted. These gene therapy approaches utilize viral vectors and are delivered stereotaxically in the brain. Alternative disease-modifying strategies focus on downregulating the expression of the α-synuclein gene using various techniques, including modified antisense oligonucleotides, short hairpin RNA, short interfering RNA, and microRNA. The latter approaches also have implications for dementia with Lewy bodies. Other PD genes can also be targeted using nucleic acids. In this review, we detail these various strategies that are still experimental, and discuss the challenges and opportunities of nucleic acid–based therapeutics for PD.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13311-019-00714-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: α-Synuclein, Antisense oligonucleotides, MicroRNA, Gene therapy, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease, affecting 1% of the population over the age of 60. In addition to classic motor symptoms of resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, gait disturbances, and postural instability, PD patients often present with non-motor symptoms, including autonomic nervous system disorders such as constipation, bladder dysfunction, and orthostatic hypotension; REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD); and olfactory impairment [1]. The abnormal accumulation of the protein α-synuclein in fibrillar form is associated with neuronal damage, particularly degeneration of dopaminergic neurons projecting from the substantia nigra pars compacta to the striatum, leading to dopamine deficiency and motor symptoms. In early-stage disease, the motor symptoms can be relieved by oral intake of l-dopa, the precursor of dopamine, or dopamine receptor agonists. However, as neurodegeneration progresses, the effects of the drugs become short lived as in l-dopa, or less effective as in dopamine agonists, and wearing-off and on-off phenomena as well as adverse motor and psychiatric effects appear. All these complicate the pharmacological management of patients as the disease advances. Braak’s hypothesis supports the emergence of various symptoms of PD at different stages of the disease, with premotor symptoms such as RBD, hyposmia, and constipation early on, and cognitive and psychiatric manifestations in later stages of the disease. This hypothesis suggests that abnormal or excessive accumulation/aggregation of α-synuclein—which is an abundant component of the hallmark pathologic lesions (Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites), and its mutations and multiplication are linked to dominantly inherited PD—spreads from the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve and olfactory bulb and perhaps even the periphery from the myenteric plexus to the lower brainstem [2]. As the disease progresses, α-synuclein spreads further to the diencephalon and cerebrum via cell-to-cell transmission. Therefore, a strategy that targets α-synuclein is believed to be a fundamental treatment for blocking the progression of neurodegeneration. In the present article, we discuss the potential of treating PD by regulating α-synuclein expression with a focus on nucleic acid medicine, a strategy that is being incorporated into clinical practice for the treatment of other neurodegenerative diseases. In addition to targeting α-synuclein, we discuss nucleic acid–based therapeutics aimed at controlling motor symptoms or improving the response to l-dopa using gene therapy to deliver dopamine biosynthetic enzymes.

Treatment of PD with Nucleic Acid Medicine Using Antisense Oligonucleotides and RNA Interference

Strategies to Downregulate α-Synuclein Expression

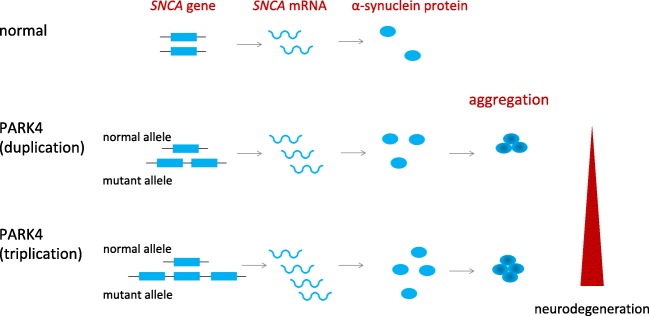

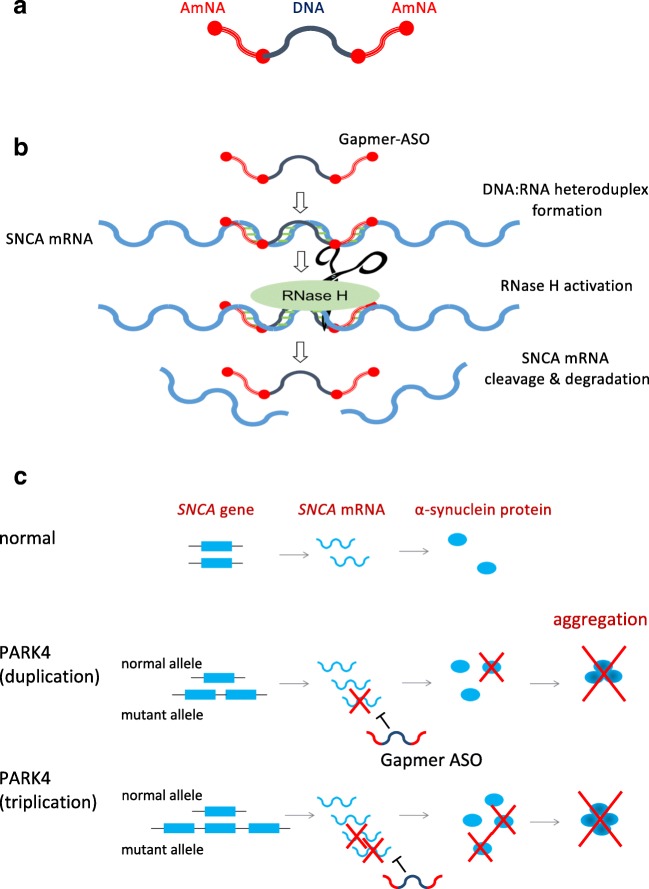

Neurodegeneration in PD can be induced by abnormal or excessive levels of α-synuclein protein, suggesting that suppressing the expression of its gene SNCA may prevent further neurodegeneration, thereby slowing disease progression. And in particular, nucleic acid medicine aimed at reducing α-synuclein protein levels is theoretically an ideal treatment for PARK4, a type of autosomal dominantly inherited PD caused by SNCA gene multiplication with clinical features that include cognitive impairment [3]. In healthy individuals, there is one copy of the SNCA gene on each chromosome, while in PARK4 patients, three (1 + 2) or four (1 + 3) copies are expressed as a result of duplication or triplication (Fig. 1). This results in excessive levels of α-synuclein protein, and its accumulation/aggregation is believed to have an adverse effect on neurons in these patients. Therefore, a strategy to reduce SNCA messenger RNA (mRNA) expression to normal levels by degrading excessive SNCA mRNA in these individuals may lead to suppression of α-synuclein protein levels and prevention of neurodegeneration (Figs. 1 and 2C).

Fig. 1.

SNCA duplication/triplication in PARK4. PARK4 is a dominantly inherited Parkinson’s disease due to multiplication of the SNCA gene locus. In PARK4 patients, α-synuclein protein is produced in excess, leading to its accumulation/aggregation and neurodegeneration

Fig. 2.

Treatment strategy for PARK4 by Gapmer-ASOs. (A) Structure of Gapmer-ASOs. The Gapmer design includes two chemically modified nucleotide sequences at the two ends, flanking a central stretch of DNA sequence. The central gap can activate RNase H, whereas the flanking sequence provides high stability and affinity. (B) Mechanism of action of Gapmer-ASOs. When Gapmer-ASOs bind to the target mRNA, RNase H recognizes the DNA:RNA heteroduplex and cleaves the RNA strand. (C) Gapmer-type antisense nucleic acid degrades α-synuclein mRNA, thereby preventing the pathological accumulation of α-synuclein in PARK4

Repression of SNCA expression by reducing its mRNA level through the use of nucleic acid medicine has been tested experimentally using various approaches in preclinical models with the aim of developing a disease-modifying treatment for PD (Table 1). For example, a therapeutic approach using ribozyme expressed by adeno-associated virus (AAV) has been attempted to degrade SNCA mRNA and allowed the survival of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)–positive neurons in the substantia nigra of rats challenged with the dopaminergic toxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) [4]. In addition, other methods that use short hairpin RNA (shRNA) and short interfering RNA (siRNA) to suppress SNCA expression have been tested [5–13]. For example, partial silencing of α-synuclein expression in striatal neurons can be achieved using a lentiviral vector expressing SNCA-targeting shRNA [5]. In addition, AAV-mediated expression of shRNA targeting SNCA in the substantia nigra in rats with ectopically expressed α-synuclein also ameliorated behavioral deficits [7, 8]. And, infusion of AAV-shRNA targeting SNCA into the substantia nigra of wild-type rats can knockdown α-synuclein protein levels by about 35% and protect against the mitochondrial toxin rotenone [9]. Direct injection of siRNA targeting SNCA into the mouse hippocampus can also result in moderate reduction of SNCA expression [10]. Infusion of siRNA targeting SNCA into the substantia nigra of non-human primates achieved a 40 to 50% reduction of α-synuclein expression [13]. Additionally, new techniques of drug delivery have been attempted to downregulate α-synuclein expression in the brain. Systemic injection of modified exosomes expressing Rabies virus glycoprotein loaded with siRNA targeting SNCA into the mouse tail vein resulted in widespread distribution of siRNA in the brain and around 50% reduction of SNCA mRNA and protein expression in the midbrain and striatum [11]. More recently using α-synuclein transgenic mice, intracerebroventricular infusion of polyethylenimine (PEI)/siRNA complex against α-synuclein resulted in 65% suppression of SNCA mRNA expression accompanied by a 50% reduction of α-synuclein protein in the striatum [12].

Table 1.

Preclinical experimental studies to knock down SNCA expression using nucleic acid medicine

| Reference | Oligonucleotides | Model | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hayashita-Kinoh et al. (2006) [4] | AAV-ribozyme | MPP+-treated PD model rat | Survival of TH-positive neurons in the SN |

| Sapru et al. (2006) [5] | Lenti-shRNA | Rat overexpressing hSNCA in the striatum by lentivirus vector | Silencing SNCA protein in striatal neurons |

| Gorbatyuk et al. (2010) [6] | AAV-shRNA | WT rat | Neurodegeneration in the SN |

| Khodr et al. (2011) [7] | AAV-shRNA | Rat overexpressing hSNCA in the SN by AAV | Amelioration of behavioral deficit and DA neuron loss |

| Kohdr et al. (2014) [8] | miRNA | Rat overexpressing hSNCA in the SN by AAV | Amelioration of behavioral deficit and inflammation |

| Zharikov et al. (2015) [9] | AAV-shRNA | WT rat/rotenone-exposed rat | 35% SNCA knockdown in the SN, improvement of motor function, and protection of DA neurons |

| Lewis et al. (2008) [10] | siRNA | WT mouse | Moderate reduction of SNCA in the hippocampus |

| Cooper et al. (2014) [11] | Exosomal siRNA | WT mouse/hSNCA transgenic mouse | 50% reduction of SNCA in the midbrain and striatum |

| Helmschrodt et al. (2017) [12] | PEI/siRNA complex | hSNCA transgenic mouse | 65% SNCA knockdown in the striatum |

| McCormack et al. (2010) [13] | siRNA | WT monkey | 40 to 50% SNCA knockdown in SN |

AAV = adeno-associated virus; DA = dopaminergic; MPP+ = 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium; PEI = polyethylenimine; SN = substantia nigra; TH = tyrosine hydroxylase; WT = wild-type

However, none of these approaches has produced ideal outcomes, and achieving long-term effects has proven challenging due to intracellular instability of these RNA-based nucleic acid compounds. Additionally, AAV-mediated expression of shRNA-SNCA can have negative effects such as increased inflammatory response, reduced TH expression, and nigrostriatal degeneration [6–8]. Thus, AAV-mediated shRNA-SNCA expression requires further optimization before it can be exploited for potential therapeutic use. Certain AAV serotypes appear to contribute to this inflammatory response.

With recent advances in nucleic acid modification technology, dramatic improvements have been made to develop nucleic acid medicines with enhanced binding affinity, increased in vivo stability, and reduced toxicity [14]. In particular, specifically designed antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) that lead to target mRNA degradation are drawing increasing attention. These ASOs have unique configurations, such as the Gapmer structure, with modified nucleic acids at both ends of a linear single-stranded oligonucleotide and normal DNA located in the center (gap) (Fig. 2A). When a Gapmer-type antisense nucleic acid with this structure binds to its target mRNA, the RNA-degrading enzyme RNase H recognizes the DNA:RNA hybrid structure formed by the DNA portion of the ASOs and the mRNA target (Fig. 2B). Additionally, the target binding affinity of the ASOs is enhanced by the modified nucleic acids placed at both ends, while also improving resistance to DNA-degrading enzymes present in the cell. After degrading the initial target mRNA, these Gapmer-type ASOs can continue to degrade other target mRNA molecules, further increasing their potency. Furthermore, because of their high resistance to nucleolytic enzymes, Gapmers can theoretically produce long-term effects at a low dose once they reach the nucleus of target cells. Notably, the effects of Gapmer-type ASOs with target degradation properties have been shown to last for a year following systemic administration in an animal model of myotonic dystrophy type 1 [15]. Clinical trials are underway for the use of Gapmer-type ASOs for the treatment of myotonic dystrophy type 1 (clinicaltrial.gov; NCT02312011), Huntington’s disease (clinicaltrial.gov; NCT02519036), as well as various other disorders.

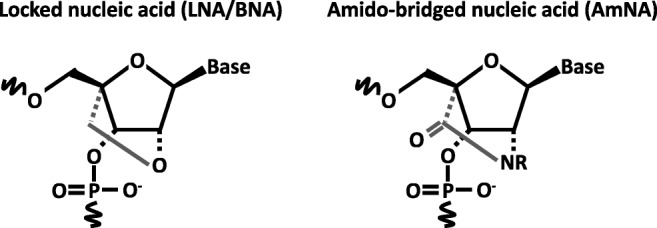

As another strategy to overcome the obstacles is associated with the stability of nucleic acid medicines in vivo and their delivery into the brain, we introduced a novel technology of nucleotide modification called amido-bridged nucleic acid (AmNA), a locked nucleic acid (LNA/BNA) analog, with increased target binding affinity and reduced toxicity [16] (Fig. 3). We have completed the optimization of the nucleic acid sequence and Gapmer-ASO structure for effective degradation of SNCA mRNA. We are currently conducting translational research to reveal the efficacy and safety in animal models for future clinical trials.

Fig. 3.

Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) chemical structures. Schematic of locked nucleic acid (LNA/BNA, left) and amido-bridged nucleic acid (AmNA, right)

In addition to ASOs, advances in CRISPR-based technology allow a novel therapeutic approach for fine-tuned downregulation of α-synuclein levels by inducing DNA methylation at the SNCA gene. A recent publication demonstrated that CRISPR-deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused with the catalytic domain of DNA-methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) reduces expression levels of SNCA mRNA and protein mediated by targeted DNA methylation at intron 1 in human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)–derived dopaminergic neurons from a PD patient with SNCA triplication [17].

Because PARK4 is a hereditary condition, it is possible to identify patients in these families with early and mild disease. It is hypothesized that preventing progression with early treatment using nucleic acid medicine for mild PARK4 will allow these patients to maintain a good level of activities of daily living (ADLs) as well as cognitive function throughout life. Additionally, establishing the efficacy of treatment using nucleic acid medicine in PARK4 patients may allow us to apply this treatment to sporadic PD as well, which is associated with abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein. This strategy may also be applied to dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), which is characterized clinically by cognitive decline and hallucinations, and pathologically by diffuse Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites containing abundant α-synuclein fibrils across various brain regions. If abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein and the spread of the proteinopathy are key in the progression of PD, as proposed in Braak’s hypothesis, this treatment strategy may be able to prevent the onset of motor symptoms if initiated early when pre-motor symptoms appear, by preventing abnormal α-synuclein propagation to substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Thus, treatment with ASOs that reduce α-synuclein may possibly be extended to all α-synucleinopathies even when α-synuclein mutation is not the cause of the disease.

Since a near-complete loss of SNCA may have adverse effects on neuronal function or integrity, the extent of downregulating SNCA should be carefully controlled. This is because α-synuclein is abundantly expressed in the normal central nervous system, especially at presynaptic terminals. Although its exact physiologic function remains to be fully understood, previous reports have suggested that α-synuclein is involved in synaptic vesicle pool maintenance, neuronal plasticity, dopamine metabolism, and insoluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex assembly critical for neurotransmitter release, vesicle recycling, and synaptic integrity [18].

Targeting Other PD Genes with Nucleic Acids

Target knockdown by nucleic acid medicine can also be applied to other gain-of-function genetic mutations that cause dominantly inherited PD. Mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) are linked to the most common familial form of PD (PARK8) [19, 20]. shRNAs specifically targeting mutations in LRRK2 were shown to lead to mutant allele-specific knockdown in human embryonic kidney (HEK)–derived 293FT or 293 cells [21, 22]. In addition, an artificial mirtron, a short hairpin intron that serves as a Drosha-independent Dicer substrate for microRNA biogenesis, targeting LRRK2 reduced endogenous LRRK2 transcripts in human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cell line [23]. Furthermore, intracerebroventricular injection in mice of ASOs targeting LRRK2 reduced mRNA and protein levels of LRRK2 as well as decreased α-synuclein inclusions in the substantia nigra induced by intrastriatal injection of preformed α-synuclein fibrils [24].

The clinical application of ASOs to various diseases is advancing rapidly due to the high target specificity and long-lasting therapeutic effects of this strategy. Research and clinical trials are underway to investigate their use in treating neurodegenerative diseases as intrathecal administration shows favorable entry to the central nervous system. Routes of administration other than intrathecal administration, such as oral, intravenous, and transdermal, are desirable when considering their use as therapeutic drugs for chronic progressive diseases such as PD, as repeated administration of nucleic acid medicines is required. With recent advances in modified nucleic acid technology and improvements in delivery systems to enhance drug delivery to target organs [25], it is hoped that a fundamental treatment for PD and DLB using nucleic acid medicine will become available in the near future.

Pathogenetic Role of MicroRNAs and Their Therapeutic Potential for PD

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small (20–25-nt) noncoding RNAs in the eukaryotic transcriptome that can regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of their target mRNAs [26]. miRNAs regulate the expression of their mRNA targets either by cleavage/degradation of mRNA or inhibition of translation. Altered expression of certain miRNAs in the brains of patients with neurodegenerative diseases including PD suggests that miRNAs could have a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of these diseases [27, 28]. The pathogenetic role of miRNAs in PD and their therapeutic potential are the subject of increasing interest in recent years.

Genetic Models with Dicer Mutants

miRNAs are derived from long primary transcripts through sequential processing by the Drosha ribonuclease and the Dicer enzyme. Dicer expression is reduced in the ventral midbrain of aged mice [29]. In addition, targeted deletion of the Dicer gene in the dopaminergic (DA) neurons of mice reportedly led to a progressive loss of DA neurons with severe locomotor deficits [30]. The latter finding suggests that Dicer is essential for DA neuron survival, and that loss of mature miRNAs due to deletion of the Dicer gene may be involved in the development and/or progression of PD.

miRNA Profiling Studies

Identifying miRNAs that are differentially expressed in postmortem brain tissue from PD brains and nonaffected controls helps in understanding the role of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of PD and may lead to recognizing potential therapeutic opportunities. Several studies of this nature have been carried out, and dysregulated miRNAs identified from these studies are listed in Table 2 [30–37]. Initially, profiling miRNAs obtained from the midbrains of PD and control subjects showed that miR-133b is highly enriched in the midbrain but found to be low in PD brains [30]. However, this finding was later challenged by another report showing that miR-133b levels were unaltered in midbrain tissue from PD brains [38]. Another miRNA profiling study identified miR-34b and miR-34c to be decreased in PD brains [37], but this finding too was not replicated in another report [34]. Subsequent studies revealed multiple miRNAs are dysregulated in PD, but few are common among the list of dysregulated miRNAs in PD across all the studies (Table 2). Discrepancies among such studies may result from a number of biological as well as technical differences. For example, differences in the analyzed brain region (e.g., midbrain vs frontal cortex) can yield disparate results. Even when the substantia nigra is analyzed, the relative numbers of DA neurons in the nigra differ significantly among individual PD brains as well as between PD brains and controls. Another factor that can critically affect outcomes using human postmortem material is variation in RNA quality/integrity due to end-of-life conditions, autolysis time, and tissue harvesting and preservation [39–41].

Table 2.

MicroRNA profiling studies in PD patients

| Reference | Sample number | Tissue | Key findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Downregulated | |||

| Tatura et al. (2016) [31] |

22 PD 10 controls |

Anterior cingulate gyri | miR-199b, miR-544a, miR-488, miR-221, miR-144 | miR-7, miR-145, miR-543 |

| Nair and Ge (2016) [32] |

12 PD 12 controls |

Putamen | miR-3195, miR-204-5p, 485-3p, 221-3p, miR-95, miR-425-5p | miR-155-5p, miR-219-2-3p, miR-3200-3p, miR-423-5p, miR-4421, miR-421, miR-382-5p |

| Hoss et al. (2016) [33] |

29 PD 33 controls |

Prefrontal cortex | miR-16-5p | let-7i-3p/5p, miR-184, miR-1224, miR-127-5p |

| Briggs et al. (2015) [34] |

8 PD 8 controls |

DA neurons collected by laser microdissection | miR-106a, miR-135a, miR-148a, miR-223, miR-26a, miR-28-5p, miR-335, miR-92a in male | (Up) let-7b, miR-106a, miR-95 in female |

| Cardo et al. (2014) [35] |

8 PD 4 controls |

Substantia nigra | miR-549d | miR-198, miR-485-5p, miR-339-5p, miR-208b, miR-135b, miR-299-5p, miR-330-5p, miR-542-3p, miR-379, miR-337-5p |

| Thomas et al. (2012) [36] |

8 PD 8 controls |

Frontal cortex | miR-200b*, miR-200a*, miR-195*, miR-424* | miR-200a, miR-199a-3p, miR-148a, miR-451, miR-144, miR-429, miR-190 |

| Minones-Moyano et al. (2011) [37] |

23 PD 28 controls |

Amygdala, substantia nigra, frontal cortex, cerebellum | miR-34b, miR-34c | |

| Kim et al. (2007) [30] |

3 PD 3 controls |

Midbrain, cerebellum, cerebral cortex | miR-133b | |

PD-Causing Genes and miRNAs

Considering the critical role of α-synuclein in PD, understanding the mechanism(s) regulating its expression is helpful in efforts to control it for therapeutic intent. Initially, we identified miRNA-7 to bind to the 3′-UTRs of α-synuclein mRNA and downregulate its expression [42]. Since then, five additional miRNAs, miR-153, miR-34b, miR-34c, miR-214, and miR-1643, were also found to bind to the 3′-UTR of α-synuclein mRNA and inhibit its expression [43–46]. Among these, miR-7, miR-34b, and miR-34c were shown to be decreased in PD brains [31, 37], suggesting that decreased expression of these particular miRNAs in PD brains can result in elevated α-synuclein levels and contribute to PD pathogenesis. Furthermore, we recently found that miR-7 also accelerates the clearance of α-synuclein and its aggregates by promoting autophagy and expedites the degradation of preformed fibrils of α-synuclein endocytosed from outside the cells [47]. This additional mechanism for reducing α-synuclein levels reinforces the notion that miR-7 is an important molecular target for PD therapeutics.

LRRK2 is the commonest genetic cause of the disease and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner with reduced penetrance [19, 20]. miRNA-205 has been reported to bind to the 3′-UTR of LRRK2 mRNA and repress its expression [48]. The levels of miR-205 were found to be decreased in the frontal cortex and striatum from PD patients, and the expression of LRRK2 was significantly upregulated in these brains [48]. This observation suggests that downregulation of miR-205 might contribute to the pathogenic increase of LRRK2 in PD brains.

Genetic Variation of miRNAs and miRNA Target Sites

Variations in miRNAs and their binding sites on target mRNAs can contribute to PD. For example, a significant association has been reported in PD with SNP (rs12720208 [C/T]) located in the 3′-UTR of FGF20 mRNA. This genetic variation lies within a predicted binding region for miR-433 [49]. The risk allele inhibits the binding of the mRNA with miR-433 and enhances FGF20 expression. This variation appears to augment the vulnerability to PD through increasing α-synuclein expression, which is mediated by FGF20. However, other reports have failed to reproduce an association between SNPs of FGF20 and PD risk, or the relationship between the variation at rs12720208 and α-synuclein protein levels [50, 51].

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have also identified variations in miR-4519 (rs897984) and miR-548at-5p (rs11651671), which are associated with PD [52]. Mutant alleles of both miRNAs change the secondary structure and result in a decrease in the level of each miRNA. Therefore, it is predicted that increased expression of certain target mRNAs resulting from decreased expression of these mutant microRNA alleles somehow contributes to PD pathogenesis. It remains to be discovered which proteins or cellular pathways regulated by these miRNAs could contribute to PD. In addition, a number of PD-associated SNPs located in the 3′-UTR of 13 genes such as α-synuclein, tau, diacylglycerol kinase theta, and transmembrane protein 175, have been identified [52]. These SNPs are predicted to influence miRNA-mediated regulation of their target genes by disrupting, generating, or modifying miRNA binding sites. Future studies are needed to determine the relationship between identified SNPs and miRNA-mediated gene regulation in the context of PD pathogenesis.

miRNA-Based Therapeutics

With the emergence of miRNAs as crucial regulators of gene expression involved in several diseases including PD, targeting miRNAs provides a potential therapeutic opportunity for PD. Two miRNA-based therapeutic approaches are currently being explored in other diseases [53]: microRNA mimics and anti-microRNAs. miRNA mimics, which are small RNA molecules that resemble miRNA precursors, are used to inhibit the expression of target proteins. The target protein can be from any gene involved in disease pathogenesis, or the disease gene itself that harbors a gain-of-function pathogenic mutation or multiplication of the gene locus. The goal of this approach is based on the hypothesis that downregulating the level of the specific protein itself is a protective therapeutic strategy. The second strategy of miRNA-based therapeutics is to utilize anti-miRNA molecules to generate a loss of function in the miRNA of interest [54]. In particular circumstances in which miRNAs are overexpressed, the intent would be to block these miRNAs by injecting a complementary RNA sequence that binds to and inactivates the target miRNAs.

Although there is no established therapy or ongoing clinical trials using miRNAs, targeting miRNAs seems to be a potential therapeutic intervention for PD. Since elevated levels of α-synuclein are toxic [55, 56], miRNAs that target and repress α-synuclein expression can be exploited to develop therapeutics for PD. Among α-synuclein targeting miRNAs, miRNA-7 is unique in several respects. In addition to targeting the 3′-UTR of α-synuclein mRNA [42], miRNA-7 facilitates the clearance of preformed α-synuclein aggregates by promoting autophagy [47]. Further, miRNA-7 displays protective effects against MPP+/1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced toxicity through α-synuclein-independent mechanisms including targeting RelA, which stimulates glycolysis, the Nrf2 pathway, and mitochondrial health [57–60]. In addition, miRNA-124 has been reported to be decreased in the MPTP-challenged mouse model, and the delivery of miR-124 to the right lateral ventricle protected TH-positive neurons from this toxin [61].

Considering that neuroinflammation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of PD [62], strategies to inhibit neuroinflammation can be exploited to impact PD as well. In this regard, miRNA-155, a well-known modulator of inflammatory response, is reportedly upregulated in the substantia nigra of mice injected with AAV2-α-synuclein. On the other hand, deletion of the miR-155 gene prevented microglial activation and mitigated the loss of TH-positive nigral neurons in AAV2-α-synuclein–injected mice [63]. Interestingly, in addition to modulating α-synuclein levels and processing, miR-7 plays a role in neuroinflammation as well. Stereotactic injection of miR-7 mimics into the mouse striatum has been shown to reduce the neuroinflammation and exert neuroprotective effects in MPTP-lesioned mice by targeting the 3′-UTR of NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) mRNA. The latter encodes a protein that is a key constituent of inflammasomes that are highly expressed in microglial cells and are important in neuroinflammation [64]. This finding suggests that miRNA-7 ameliorates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation and highlights the various neuroprotective mechanisms of miRNA-7 and, therefore, its therapeutic potential for PD.

Gene Therapy for PD

Delivery of Neurotransmitter Biosynthetic Enzymes

Gene therapy is a method to treat a disease by exogenously delivering genetic material into cells with genetic abnormalities or other biochemical deficiencies in order to recover normal function [65]. Viral vectors are primarily used as a means of introducing genes to cells. Clinical research with viral vectors made great headway in the early 1990s, and gene therapy was tested in various disease targets. Unfortunately, a series of some 2000 reports describing adverse effects, some of which were serious including death, led to a stagnation period in the field [66]. However, because of steady progress in basic research resulting in increased safety and reliability, gene therapy is once again drawing attention. With the development of viral vectors that effectively introduce therapeutic genes into target neurons and myocytes, in vivo gene therapy, a technique in which genes are directly introduced into the body using vectors containing the therapeutic genes, is being tested in neurodegenerative diseases and myopathies. AAV vectors are primarily used in gene therapy in these conditions. This is because AAV vectors are safe, as they are derived from AAV, which is a nonpathogenic virus. These vectors can deliver genes to terminally differentiated nondividing cells such as neurons and myocytes, and they are expected to enable long-term expression of the introduced genes [65]. In addition, one of the advantages of AAV vectors is that integration into chromosomal DNA occurs rarely, thus minimizing the risk of inactivating tumor suppressor genes or activating protooncogenes. Furthermore, numerous AAV serotypes are available with different tissue tropisms, and serotypes 1, 2, 5, 8, and 9 show affinity for the nervous system.

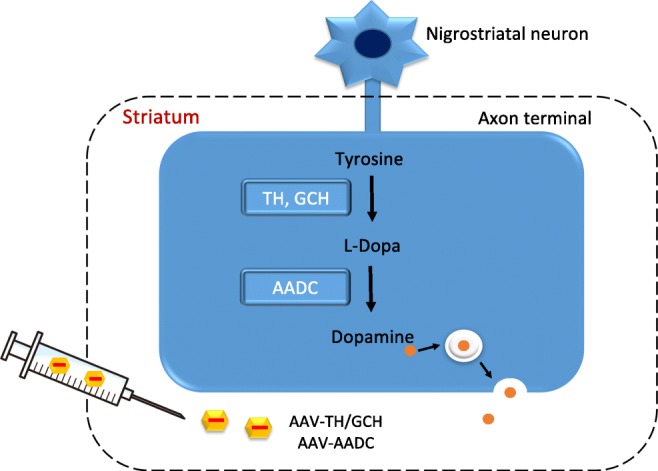

The classic motor symptoms of PD are due to dopamine deficiency in the striatum caused by degeneration of nigrostriatal neurons. TH, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine biosynthesis, converts the amino acid tyrosine to l-dopa in axon terminals projecting from the substantia nigra pars compacta to the striatum. Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) further converts l-dopa into dopamine (Fig. 4). In addition, guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I (GCH) plays an important role in the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin, a coenzyme of TH. Therefore, strategies for enhancing dopamine synthesis by delivering its synthetic enzymes using viral vectors have been examined (Table 3). In an open-label phase 1 trial in PD patients conducted in the USA, delivery of AADC-expressing AAV type 2 vector (AAV2-AADC) into the putamen bilaterally resulted in a 36% improvement in the motor score of the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) in the off l-dopa state [67]. In another open-label phase 1 trial conducted in Japan, the AAV2-AADC vector delivered bilaterally into the putamen resulted in 46% improvement in the UPDRS score in the off state and increased uptake of the AADC tracer 6-[18F]fluoro-l-m-tyrosine on positron emission tomography (PET) imaging [68]. Notably, long-term follow-up of subjects in another phase 1 trial of AAV2-AADC reported stable transgene expression for 4 years or longer [69]. In addition, an open-label phase 1/2 trial, in which not only AADC but also TH and GCH genes were expressed simultaneously using equine infectious anemia virus, a putative lentivirus, and delivered into the putamen bilaterally, was attempted in Europe [70]. Motor function, as measured by UPDRS part III scores off l-dopa, improved in all patients at 6 months and 1 year after the administration of this gene therapy drug named ProSavin®, and daily l-dopa equivalent dose was reduced or remained stable [70]. PET imaging with [11C]-raclopride as a tracer was consistent with increased dopamine production in the putamen.

Fig. 4.

Dopamine biosynthesis in the striatum, and gene therapy approaches to increase dopamine production in PD. In axonal terminals in the striatum, tyrosine is converted to l-dopa by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and further converted into dopamine by aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC). In advanced stages of PD, the activity of these enzymes decreases dramatically due to a loss of neuronal terminals. Gene therapy for PD introduces these enzymes into the striatum using viral vectors

Table 3.

Clinical trials with gene therapy approaches in PD

| Reference | Strategy | Target gene/vector | Injection site | Study | Number of participants | Therapeutic effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christine et al. (2009) [67] | Dopamine biosynthesis | AADC/AAV | Bilateral intraputaminal infusion | Phase 1, open-label | 10 |

Safe and well tolerated Average 30% increase in 6-[(18)F]fluoro-l-m-tyrosine uptake by PET in the putamen |

| Muramatsu et al. (2010) [68] | Dopamine biosynthesis | AADC/AAV | Bilateral intraputaminal infusion | Phase 1, open-label | 6 |

Safe and well tolerated Motor function in the off-medication state improved an average of 46% based on the UPDRS scores |

| Mittermeyer et al. (2012) [69] | Dopamine biosynthesis | AADC/AAV | Bilateral intraputaminal infusion | Phase 1, open-label | 10 |

Safe and well tolerated UPDRS scores off l-dopa for 12 h improved in all patients in the first 12 months |

| Palfi et al. (2014) [70] | Dopamine biosynthesis | TH, AADC, GCH/EIAV | Bilateral intraputaminal injection | Phase 1/2, open-label | 15 |

No serious adverse events Off-medication improvement in mean UPDRS part III motor scores was recorded in all patients at 6 months and 12 months compared with baseline |

| Kaplitt et al. (2007) [71] | STN activity modulation | GAD/AAV | Unilateral subthalamic nucleus injection | Phase 1, open-label | 12 |

No adverse events related to gene therapy Improvement in motor UPDRS scores at 3 months |

| LeWitt et al. (2011) [72] | STN activity modulation | GAD/AAV | Bilateral subthalamic nucleus injection | Phase 2, double-blind, sham surgery controlled, randomized | 66 | Improvement from baseline in UPDRS scores compared with the sham group over the 6-month course of the study |

| Marks et al. (2010) [73] | Neurotrophic factor | Neurturin/AAV | Bilateral intraputaminal injection | Phase 2, double-blind, sham surgery controlled, randomized | 58 |

No significant difference in the primary endpoint Serious adverse events occurred in 13 of 38 patients |

| Olanow et al. (2015) [74] | Neurotrophic factor | Neurturin/AAV | Bilateral intraputaminal and substantia nigra injection | Phase 2, double-blind, sham surgery controlled, randomized | 51 | No significant difference in the primary endpoint |

| Neurotrophic factor | GDNF/AAV | Bilateral putamina | Phase 1 | Ongoing |

AADC = aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase; AAV = adeno-associated virus; EIAV = equine infectious anemia virus; GAD = glutamic acid decarboxylase; GCH = guanosine triphosphate cyclohydroxylase I; TH = tyrosine hydroxylase; GDNF = glial fibrillary acidic protein

Decreased dopamine levels in the putamen are suggested to lead to disinhibition of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) in PD [65]. The increased excitatory drive of the STN to the internal portion of globus pallidus and substantia nigra pars reticulate exerts inhibitory effects on the thalamocortical projection and brainstem nuclei and exacerbates motor symptoms in PD. Treatments are currently being tested in which the glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) gene, required for the synthesis of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, is introduced using AAV vectors with the goal of modulating STN activity in PD patients. In an open-label phase 1 trial conducted in the USA involving gene introduction to the subthalamic nucleus unilaterally, improvement in the UPDRS motor score was observed on the contralateral side 3 to 12 months following AAV-GAD administration [71]. A double-blind, sham surgery–controlled, randomized phase 2 trial with bilateral subthalamic nucleus injections in 66 patients with advanced PD also showed a modest but significant improvement from baseline in UPDRS scores (8.1 points) compared with the sham group (4.7 points) over the 6-month course of the study [72].

Delivery of Trophic Factor Genes

Neurotrophic factor delivery using viral vectors has also been attempted in order to protect dopaminergic neurons in PD. In a phase 2, double-blind, sham surgery–controlled, randomized trial where neurturin, a neurotrophic factor for dopaminergic neurons, was expressed bilaterally in the putamen using AAV2, there was no significant difference in the degree of improvement in motor symptoms 12 months later compared to the control group [73]. A follow-up double-blind trial delivering neurturin bilaterally in both the putamen and substantia nigra in patients with advanced PD also failed to show a benefit [74]. An open-label phase 1 trial of AAV2-glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor delivered bilaterally into both putamina of advanced PD patients using convection-enhanced delivery is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01621581). In addition to viral vector–mediated delivery of neurotrophic factors, nucleic acid–based therapy with activatory RNA–based molecules may be applied for PD treatment by increasing the expression of neurotrophic factors, as well as compensatory factors in cases of loss-of-function mutations in PD. This state-of-the-art nucleic acid–based technology contains small activating RNAs (saRNAs), artificial transactivators NMHVs (an acronym for nuclear localization signal-MS2 coat protein RNA–interacting domain-HA epitope-(3x)VP16–transactivating domain), AntagoNATs that inhibit natural antisense lncRNA transcripts (NATs), and SINEUPs that stimulate translation of target mRNA (details are provided in a review by Gustincich et al. [75]).

In conclusion, the potential for nucleic acid–based therapies in PD is varied and diverse with multiple approaches and targets. While none is available to patients at this time, the prospects are clear and encouraged by recent advances in other neurologic conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by AMED under Grant Number JP17ek0109195. E.J. is supported by the NIH (NS070898 and NS095003) and the State of New Jersey. M.M.M. is the William Dow Lovett Professor of Neurology and is supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the American Parkinson Disease Association, and the New Jersey Health Foundation/Nicholson Foundation, and by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (AT006868, NS073994, NS096032, and NS101134).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Disclosures

M.N. and H.M. have a pending patent (WO2017119463A1) relevant to this work. E.J. and M.M.M. hold patents on RNA targeting in alpha-synucleinopathies.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Titova N, Qamar MA, Chaudhuri KR. The Nonmotor Features of Parkinson’s Disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;132:33–54. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuda T, Mochizuki H. The regulatory role of alpha-synuclein and parkin in neuronal cell apoptosis; possible implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Apoptosis. 2010;15:1312–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashita-Kinoh H, Yamada M, Yokota T, Mizuno Y, Mochizuki H. Down-regulation of alpha-synuclein expression can rescue dopaminergic cells from cell death in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s disease rat model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sapru MK, Yates JW, Hogan S, Jiang L, Halter J, Bohn MC. Silencing of human alpha-synuclein in vitro and in rat brain using lentiviral-mediated RNAi. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorbatyuk OS, Li S, Nash K, et al. In vivo RNAi-mediated alpha-synuclein silencing induces nigrostriatal degeneration. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khodr CE, Sapru MK, Pedapati J, et al. An alpha-synuclein AAV gene silencing vector ameliorates a behavioral deficit in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease, but displays toxicity in dopamine neurons. Brain Res. 2011;1395:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khodr CE, Becerra A, Han Y, Bohn MC. Targeting alpha-synuclein with a microRNA-embedded silencing vector in the rat substantia nigra: positive and negative effects. Brain Res. 2014;1550:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zharikov AD, Cannon JR, Tapias V, et al. shRNA targeting alpha-synuclein prevents neurodegeneration in a Parkinson’s disease model. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2721–2735. doi: 10.1172/JCI64502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis J, Melrose H, Bumcrot D, et al. In vivo silencing of alpha-synuclein using naked siRNA. Mol Neurodegener. 2008;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper JM, Wiklander PB, Nordin JZ, et al. Systemic exosomal siRNA delivery reduced alpha-synuclein aggregates in brains of transgenic mice. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1476–1485. doi: 10.1002/mds.25978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmschrodt C, Hobel S, Schoniger S, et al. Polyethylenimine Nanoparticle-Mediated siRNA Delivery to Reduce alpha-Synuclein Expression in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2017;9:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormack AL, Mak SK, Henderson JM, Bumcrot D, Farrer MJ, Di Monte DA. Alpha-synuclein suppression by targeted small interfering RNA in the primate substantia nigra. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evers MM, Toonen LJ, van Roon-Mom WM. Antisense oligonucleotides in therapy for neurodegenerative disorders. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;87:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheeler TM, Leger AJ, Pandey SK, et al. Targeting nuclear RNA for in vivo correction of myotonic dystrophy. Nature. 2012;488:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature11362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto T, Yahara A, Waki R, et al. Amido-bridged nucleic acids with small hydrophobic residues enhance hepatic tropism of antisense oligonucleotides in vivo. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:3757–3765. doi: 10.1039/C5OB00242G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kantor B, Tagliafierro L, Gu J, et al. Downregulation of SNCA Expression by Targeted Editing of DNA Methylation: A Potential Strategy for Precision Therapy in PD. Mol Ther. 2018;26:2638–2649. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mochizuki H, Choong CJ, Masliah E. A refined concept: alpha-synuclein dysregulation disease. Neurochem Int. 2018;119:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, et al. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Ynigo-Mojado L, Martin-Ruiz I, Sutherland JD. Efficient allele-specific targeting of LRRK2 R1441 mutations mediated by RNAi. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sibley CR, Wood MJ. Identification of allele-specific RNAi effectors targeting genetic forms of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibley CR, Seow Y, Curtis H, Weinberg MS, Wood MJ. Silencing of Parkinson’s disease-associated genes with artificial mirtron mimics of miR-1224. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9863–9875. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao HT, John N, Delic V, et al. LRRK2 Antisense Oligonucleotides Ameliorate alpha-Synuclein Inclusion Formation in a Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Model. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:508–519. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishina K, Piao W, Yoshida-Tanaka K, et al. DNA/RNA heteroduplex oligonucleotide for highly efficient gene silencing. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7969. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junn E, Mouradian MM. MicroRNAs in neurodegenerative disorders. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1717–1721. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.9.11296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Junn E, Mouradian MM. MicroRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases and their therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chmielarz P, Konovalova J, Najam SS, et al. Dicer and microRNAs protect adult dopamine neurons. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2813. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J, Inoue K, Ishii J, et al. A MicroRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science. 2007;317:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1140481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatura R, Kraus T, Giese A, et al. Parkinson’s disease: SNCA-, PARK2-, and LRRK2- targeting microRNAs elevated in cingulate gyrus. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;33:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nair VD, Ge Y. Alterations of miRNAs reveal a dysregulated molecular regulatory network in Parkinson’s disease striatum. Neurosci Lett. 2016;629:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoss AG, Labadorf A, Beach TG, Latourelle JC, Myers RH. microRNA Profiles in Parkinson’s Disease Prefrontal Cortex. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:36. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Briggs CE, Wang Y, Kong B, Woo TU, Iyer LK, Sonntag KC. Midbrain dopamine neurons in Parkinson’s disease exhibit a dysregulated miRNA and target-gene network. Brain Res. 2015;1618:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardo LF, Coto E, Ribacoba R, et al. MiRNA profile in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s disease and healthy subjects. J Mol Neurosci. 2014;54:830–836. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0428-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas RR, Keeney PM, Bennett JP. Impaired complex-I mitochondrial biogenesis in Parkinson disease frontal cortex. J Parkinsons Dis. 2012;2:67–76. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2012-11074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minones-Moyano E, Porta S, Escaramis G, et al. MicroRNA profiling of Parkinson’s disease brains identifies early downregulation of miR-34b/c which modulate mitochondrial function. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3067–3078. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlaudraff F, Grundemann J, Fauler M, Dragicevic E, Hardy J, Liss B. Orchestrated increase of dopamine and PARK mRNAs but not miR-133b in dopamine neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2302–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kingsbury AE, Daniel SE, Sangha H, Eisen S, Lees AJ, Foster OJ. Alteration in alpha-synuclein mRNA expression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2004;19:162–170. doi: 10.1002/mds.10683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dachsel JC, Lincoln SJ, Gonzalez J, Ross OA, Dickson DW, Farrer MJ. The ups and downs of alpha-synuclein mRNA expression. Mov Disord. 2007;22:293–295. doi: 10.1002/mds.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grundemann J, Schlaudraff F, Haeckel O, Liss B. Elevated alpha-synuclein mRNA levels in individual UV-laser-microdissected dopaminergic substantia nigra neurons in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Junn E, Lee KW, Jeong BS, Chan TW, Im JY, Mouradian MM. Repression of alpha-synuclein expression and toxicity by microRNA-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13052–13057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906277106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doxakis E. Post-transcriptional regulation of alpha-synuclein expression by mir-7 and mir-153. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12726–12734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.086827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabaria S, Choi DC, Chaudhuri AD, Mouradian MM, Junn E. Inhibition of miR-34b and miR-34c enhances alpha-synuclein expression in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang ZH, Zhang JL, Duan YL, Zhang QS, Li GF, Zheng DL. MicroRNA-214 participates in the neuroprotective effect of Resveratrol via inhibiting alpha-synuclein expression in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mouse. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;74:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim W, Song G. Identification of novel regulatory genes in development of the avian reproductive tracts. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi DC, Yoo M, Kabaria S, Junn E. MicroRNA-7 facilitates the degradation of alpha-synuclein and its aggregates by promoting autophagy. Neurosci Lett. 2018;678:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho HJ, Liu G, Jin SM, et al. MicroRNA-205 regulates the expression of Parkinson’s disease-related leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 protein. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:608–620. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang G, van der Walt JM, Mayhew G, et al. Variation in the miRNA-433 binding site of FGF20 confers risk for Parkinson disease by overexpression of alpha-synuclein. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Mena L, Cardo LF, Coto E, et al. FGF20 rs12720208 SNP and microRNA-433 variation: no association with Parkinson’s disease in Spanish patients. Neurosci Lett. 2010;479:22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wider C, Dachsel JC, Soto AI, et al. FGF20 and Parkinson’s disease: no evidence of association or pathogenicity via alpha-synuclein expression. Mov Disord. 2009;24:455–459. doi: 10.1002/mds.22442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghanbari M, Darweesh SK, de Looper HW, et al. Genetic Variants in MicroRNAs and Their Binding Sites Are Associated with the Risk of Parkinson Disease. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:292–300. doi: 10.1002/humu.22943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wen MM. Getting miRNA Therapeutics into the Target Cells for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Mini-Review. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:129. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meister G, Landthaler M, Dorsett Y, Tuschl T. Sequence-specific inhibition of microRNA- and siRNA-induced RNA silencing. RNA. 2004;10:544–550. doi: 10.1261/rna.5235104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maraganore DM, de Andrade M, Elbaz A, et al. Collaborative analysis of alpha-synuclein gene promoter variability and Parkinson disease. JAMA. 2006;296:661–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cookson MR. alpha-Synuclein and neuronal cell death. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi DC, Chae YJ, Kabaria S, et al. MicroRNA-7 protects against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced cell death by targeting RelA. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12725–12737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0985-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaudhuri AD, Kabaria S, Choi DC, Mouradian MM, Junn E. MicroRNA-7 Promotes Glycolysis to Protect against 1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced Cell Death. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12425–12434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.625962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kabaria S, Choi DC, Chaudhuri AD, Jain MR, Li H, Junn E. MicroRNA-7 activates Nrf2 pathway by targeting Keap1 expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaudhuri AD, Choi DC, Kabaria S, Tran A, Junn E. MicroRNA-7 Regulates the Function of Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore by Targeting VDAC1 Expression. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6483–6493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.691352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanagaraj N, Beiping H, Dheen ST, Tay SS. Downregulation of miR-124 in MPTP-treated mouse model of Parkinson’s disease and MPP iodide-treated MN9D cells modulates the expression of the calpain/cdk5 pathway proteins. Neuroscience. 2014;272:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirsch EC, Vyas S, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(Suppl 1):S210–212. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thome AD, Harms AS, Volpicelli-Daley LA, Standaert DG. microRNA-155 Regulates Alpha-Synuclein-Induced Inflammatory Responses in Models of Parkinson Disease. J Neurosci. 2016;36:2383–2390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3900-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou Y, Lu M, Du RH, et al. MicroRNA-7 targets Nod-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome to modulate neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:28. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0094-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choong CJ, Baba K, Mochizuki H. Gene therapy for neurological disorders. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16:143–159. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2016.1114096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naldini L. Gene therapy returns to centre stage. Nature. 2015;526:351–360. doi: 10.1038/nature15818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Christine CW, Starr PA, Larson PS, et al. Safety and tolerability of putaminal AADC gene therapy for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1662–1669. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c29356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muramatsu S, Fujimoto K, Kato S, et al. A phase I study of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1731–1735. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mittermeyer G, Christine CW, Rosenbluth KH, et al. Long-term evaluation of a phase 1 study of AADC gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:377–381. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palfi S, Gurruchaga JM, Ralph GS, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of ProSavin, a lentiviral vector-based gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease: a dose escalation, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1138–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61939-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, et al. Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson’s disease: an open label, phase I trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.LeWitt PA, Rezai AR, Leehey MA, et al. AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:309–319. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marks WJ, Jr, Bartus RT, Siffert J, et al. Gene delivery of AAV2-neurturin for Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1164–1172. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Warren Olanow C, Bartus RT, Baumann TL, et al. Gene delivery of neurturin to putamen and substantia nigra in Parkinson disease: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:248–257. doi: 10.1002/ana.24436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gustincich S, Zucchelli S, Mallamaci A. The Yin and Yang of nucleic acid-based therapy in the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;155:194–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)