Abstract

As populations increase their life expectancy, age-related neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease have become more common. I2-Imidazoline receptors (I2-IR) are widely distributed in the central nervous system, and dysregulation of I2-IR in patients with neurodegenerative diseases has been reported, suggesting their implication in cognitive impairment. This evidence indicates that high-affinity selective I2-IR ligands potentially contribute to the delay of neurodegeneration. In vivo studies in the female senescence accelerated mouse-prone 8 mice have shown that treatment with I2-IR ligands, MCR5 and MCR9, produce beneficial effects in behavior and cognition. Changes in molecular pathways implicated in oxidative stress, inflammation, synaptic plasticity, and apoptotic cell death were also studied. Furthermore, treatments with these I2-IR ligands diminished the amyloid precursor protein processing pathway and increased Aβ degrading enzymes in the hippocampus of SAMP8 mice. These results collectively demonstrate the neuroprotective role of these new I2-IR ligands in a mouse model of brain aging through specific pathways and suggest their potential as therapeutic agents in brain disorders and age-related neurodegenerative diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13311-018-00681-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Imidazoline I2 receptors, (2-imidazolin-4-yl)phosphonates, Behavior, Cognition, Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection, Aging

Introduction

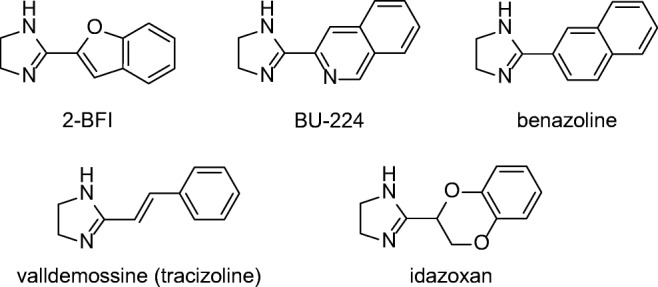

Imidazoline receptors (non-adrenergic receptors for imidazolines) [1] have been identified as a promising biological target that deserves further investigation using multidisciplinary approaches to build a comprehensive understanding of their pharmacological possibilities. To date, three main imidazoline receptors, I1-, I2- and I3-IR, have been identified as binding sites that recognize different radiolabeled ligands involving different locations and physiological functions [2–4]. The pharmacological characterization of I1-IR is understood the best, and they are used in the antihypertensive drugs moxonidine [5] or rilmenidine [6]. To date, I2-IR have not been structurally described, although García-Sevilla’s group has defined distinct binding proteins corresponding to subgroups of I2-IR sites [7]. I2-IR are involved in analgesia [8], glial tumors [9], inflammation [10] and a plethora of brain disorders, such as AD [11, 12], Parkinson’s disease (PD) [13], and different psychiatric disorders [14–16]. The efficacy of the analgesic CR4056 in osteoarthritis has advanced this compound in the first-in-class I2-IR ligand to achieve phase II clinical trials [17]. I2-IR are widely distributed in the CNS, bind imidazoline-based compounds [18, 19], such as idazoxan or valldemossine [20], and have been associated with the catalytic site of monoamine oxidase enzyme (MAO) [21]. A neuroprotective role for I2-IR was described through the pharmacological activities observed for their ligands [22]. Idazoxan reduced neuron damage in the hippocampus after global ischemia in the rat brain [23] and agmatine, identified as the endogenous I2-IR ligand [24], has demonstrated modulatory actions in several neurotransmitters that produce neuroprotection both in vitro and in rodent models [25]. The compelling evidence has demonstrated that other selective I2-IR ligands (Fig. 1) provide benefits such as being neuroprotective against cerebral ischemia in vivo [26, 27], inducing beneficial effects in several models of chronic opioid therapy, leading to neuroprotection by direct blocking of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) mediated intracellular [Ca2+] influx [28], or provoking morphological/biochemical changes in astroglia that are neuroprotective after neonatal axotomy [22].

Fig. 1.

Representative I2-IR ligands

At a cellular level, I2-IR are situated in the outer membrane of the mitochondria in astrocytes [29], and a direct physiological function of glial I2-imidazoline preferring sites that regulate the level of the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap) has been proposed [30]. In addition, astrogliosis is a pathophysiological trend in brain neurodegeneration as in AD [31]. The density of I2-IR is markedly increased in the brains of patients with AD [13], and in gliosis associated with brain injury [32].

The pharmacological characterization of these receptors relies on the discovery of selective I2-IR ligands devoid of a high affinity for I1-IR and α2-adrenoceptors. The reported I2-IR ligands are structurally restricted, featuring rigid substituted pattern imidazolines, and most of which are not entirely selective and thus interact with α-adrenoceptors [19], which causes side effects [33]. Our chemistry program aimed to find new selective I2-IR ligands to increase the arsenal of pharmacological tools to exploit the therapeutic potential of I2-IR in neuroprotection.

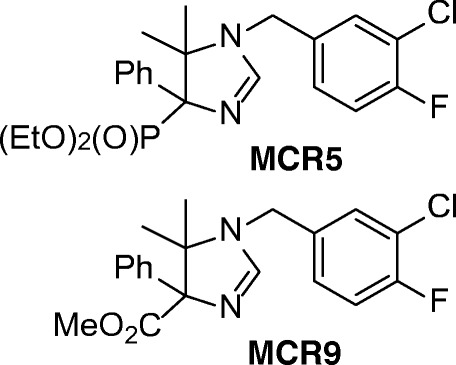

We have recently synthesized a series of new chemical scaffolds, 2-imidazolin-4-yl)phosphonates [34], by an isocyanide-based multicomponent reaction under microwave irradiation to avoid using solvents. The experimental synthetic conditions fulfill the principles of green chemistry, giving access to novel compounds with high selectivity and affinity for I2-IR. Among them, we tested MCR5 [diethyl (1-(3-chloro-4-fluorobenzyl)-5,5-dimethyl-4-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-4-yl)phosphonate] in a previous work to demonstrate its neuroprotective and analgesic effects, and it showed promising results in models of brain damage [35]. In particular, mechanisms of neuroprotection related to regulating apoptotic pathways or inhibiting p35 cleavage mediated by this new active compound have been found. In the present work, we explored the behavioral and cognitive status, including molecular changes associated with age and neurodegenerative processes, presented by SAMP8 mice when treated with the new highly selective I2-IR ligands MCR5 and MCR9 [methyl 1-(3-chloro-4-fluorobenzyl)-5,5-dimethyl-4-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazole-4-carboxylate] (Fig. 2). SAMP8 is a naturally occurring mouse strain that displays a phenotype of accelerated aging with cognitive decline, as observed in AD, and is widely used as a feasible rodent model of cognitive dysfunction [36]. To the best of our knowledge, this manuscript reports the first study that includes cognitive and behavioral parameters of novel I2-IR ligands in a well-characterized animal model for studying brain aging and neurodegeneration.

Fig. 2.

Structure of I2-IR ligands MCR5 and MCR9

Material and Methods

Synthesis of I2-IR Ligands MCR5 and MCR9

The compounds were prepared using our previously optimized conditions [34]. I2-IR pKi for MCR5 and MCR9 were determined as 9.42±0.16 nM and 8.85±0.21 nM, respectively, showing that both compounds also had high selectivity against α2 adrenergic receptors (457 and 1862, respectively) [35].

The Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Determination Method

The in vitro permeability (Pe) of the novel compounds through a lipid extract of the porcine brain was determined using a mixture of PBS/EtOH 70:30. The concentration of drugs was determined using a UV/VIS (250-500 nm) plate reader. Assay validation was carried out by comparing the experimental and reported permeability values of 14 commercial drugs (see supporting information), which provided a good linear correlation: Pe (exp) = 1.003 Pe (lit) _ 0.783 (R2 = 0.93). Using this equation and the limits established by Di et al. [37] for BBB permeation, the following ranges of permeability were established: Pe (10-6 cm·s-1) > 5.18 for compounds with high BBB permeation (CNS+); Pe (10-6 cm·s-1) < 2.06 for compounds with low BBB permeation (CNS_); and 5.18 > Pe (10-6 cm·s-1) > 2.06 for compounds with uncertain BBB permeation (CNS±).

Measurements of Hypothermic Effects

For this study, 25 adult male CD-1 mice (30-40 g) bred in the animal facility at the University of the Balearic Islands were used. Mice were housed in standard cages under defined environmental conditions (22°C, 70% humidity, and a 12-h light/dark cycle, lights on at 8:00 AM) and with free access to a standard diet and tap water. Experimental procedures followed the ARRIVE [38] and standard ethical guidelines (European Communities Council Directive 86/609/EEC and Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research, National Research Council 2003) and were approved by the Local Bioethics Committee (UIB-CAIB). All efforts were made to minimize the number of mice used and their suffering.

Mice were handled and weighed by the same person for 2 days so they could habituate to the experimenter before any experimental procedures were initiated. For the acute treatment, mice received a single dose of MCR9 (20 mg/kg, i.p., n=6) or vehicle (a mixture of equal parts of DMSO and saline, i.p., n=7). For the repeated treatment, mice were treated daily with MCR9 (20 mg/kg, i.p., n=6) or vehicle (a mixture of equal parts of DMSO and saline, i.p., n=6) for 5 consecutive days. The hypothermic effect of compound MCR9 was evaluated by measuring rectal temperature before any drug treatment (basal value) and 1 h after drug injection by a rectal probe connected to a digital thermometer (compact LCD thermometer, SA880-1M, RS, Corby, UK). Mice were sacrificed immediately after the last measurement of rectal temperature.

SAMP8 Mouse In Vivo Experiments

SAMP8 female mice (n=26) (12 months old) were used to carry out cognitive and molecular analyses. We divided these animals randomly into three groups: SAMP8 Control (n=10) and SAMP8 treated with I2-IR ligands (MCR5, n=8 and MCR9, n=8). Animals had free access to food and water and were kept under standard temperature conditions (22±2°C) and a 12-h light/dark cycle (300 lux/0 lux). MCR5 and MCR9 (5 mg/Kg/day) were dissolved in 1.8% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and administered through drinking water for 4 weeks. Water consumption was controlled each week, and I2-IR ligand concentrations were adjusted accordingly to reach the optimal dose.

Studies and procedures involving mice brain dissection and subcellular fractionation were performed by the ARRIVE [38] and international guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (see above) and approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation at the University of Barcelona.

Open Field (OFT), Elevated Plus Maze (EPM), and Novel Object Recognition Test (NORT)

The OFT apparatus was a white polywood box (50x50x25 cm). The floor was divided into two areas defined as center zone and peripheral zone (15 cm between the center zone and the wall). Behavior was scored with SMART® vers. 3.0 software, and each trial was recorded for later analysis using a camera situated above the apparatus. Twenty-six mice (n=8-10 per group) were placed at the center and allowed to explore the box for 5 min. Afterward, the mice were returned to their home cages and the OFT apparatus was cleaned with 70% EtOH. The parameters scored included center staying duration, rears, defecations, and the distance traveled, calculated as the sum of total distance traveled in 5 min.

The EMP apparatus consists of opened arms and closed arms, crossed in the middle perpendicularly to each other, and a central platform (5×5cm) constructed of dark and white plywood (30×5×15 cm). To initiate the test session, 26 mice (n=8-10 per group) were placed on the central platform, facing an open arm, and allowed to explore the apparatus for 5 min. After the 5-min test, mice were returned to their home cages, and the EPM apparatus was cleaned with 70% EtOH and allowed to dry between tests. Behavior was scored with SMART® vers. 3.0 software, and each trial was recorded for later analysis using a camera fixed to the ceiling at a height of 2.1 m and situated above the apparatus. The parameters recorded included time spent on opened arms, time spent on closed arms, time spent in the center zone, rears, defecation and urination.

The NORT protocol employed was a modification of that of Ennaceur and Delacour [39]. In brief, 26 mice (n=8-10 per group) were placed in a 90°, two-arm, 25-cm-long, 20-cm-high, 5-cm-wide black maze. The walls could be removed for easy cleaning. Light intensity in mid-field was 30 lux. Before performing the test, the mice were individually habituated to the apparatus for 10 min for 3 days. On day 4, the animals were submitted to a 10-min acquisition trial (first trial), during which they were placed in the maze in the presence of two identical, novel objects (A+A or B+B) at the end of each arm. A 10-min retention trial (second trial) was carried out 2 h and 24 h later, with one of the two objects changed. During these second trials, mice behavior was recorded with a camera. The time with the new object (TN) and the time with the old object (TO) were measured. A discrimination index (DI) was defined as (TN−TO)/(TN+TO). The maze and the objects were cleaned with 96% EtOH after each test to eliminate olfactory cues.

Brain Processing

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation 1 day after the behavioral and cognitive tests finished. Brains were immediately removed from the skull. The hippocampus of each mouse was then isolated and frozen in powdered dry ice. Each hippocampus was maintained at -80°C for further use. Tissue samples were homogenized in lysis buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Cocktail II, Sigma-Aldrich). Total protein levels were obtained and the Bradford method was used to determine protein concentration.

Protein Levels Determination by Western Blot (WB)

For WB, aliquots of 15 μg of hippocampal protein were used. Protein samples from 15 mice (n=5 per group) were separated by SDS-PAGE (8-12%) and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). Afterward, membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk in 0.1% Tween20 TBS (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with the primary antibodies listed in Table 1 (Supporting Information). Membranes were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive proteins were viewed with a chemiluminescence-based detection kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol (ECL Kit; Millipore) and digital images were acquired using a ChemiDoc XRS+ System (BioRad). Semi-quantitative analyses were carried out using ImageLab software (BioRad), and results were expressed in arbitrary units, considering control protein levels as 100%. Protein loading was routinely monitored by immunodetection of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Determination of OS in the Hippocampus

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) from 12 mice (n=4 per group) was measured in hippocampal tissue protein extracts obtained as described above. It was used as an indicator of OS and was quantified using a hydrogen peroxide assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Determination

Total RNA isolation was carried out using the TRIzol® reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions. The yield, purity, and quality of RNA were determined spectrophotometrically with a NanoDrop™ ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific) apparatus and an Agilent 2100B Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). RNAs with 260/280 ratios and RIN higher than 1.9 and 7.5, respectively, were selected. Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) was performed as follows: 2 μg of mRNA was reverse-transcribed using the high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was employed to quantify the mRNA expression of OS genes heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 (Hmox1), aldehyde oxidase 1 (Aox1), cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2), inflammatory genes interleukin 6 (Il-6), interleukin 1 beta (Il-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnf-α), amyloid processing gene disintegrin, and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 (Adam10) and amyloid degradation gene neprilysin (NEP). The primers are listed in Table 2 (Supporting Information).

SYBR® Green real-time PCR was performed in a Step One Plus Detection System (Applied-Biosystems) employing SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied-Biosystems). Each reaction mixture contained 7.5 μL of cDNA (a 2-μg concentration), 0.75 μL of each primer (a 100-nM concentration, each), and 7.5 μL of SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (2X).

TaqMan-based real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems) was also performed in a Step One Plus Detection System (Applied-Biosystems). Each 20 μL of TaqMan reaction contained 9 μL of cDNA (25 ng), 1 μL 20X probe of TaqMan Gene Expression Assays and 10 μL of 2X TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix.

Data were analyzed using the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method (ΔΔCt), where the housekeeping gene level was used to normalize differences in sample loading and preparation. Normalization of expression levels was performed with actin for SYBR® green-based real-time PCR results and Tbp for TaqMan-based real-time PCR. Each sample (n=4-5 per group) was analyzed in duplicate, and the results represent the n-fold difference of the transcript levels among different groups.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism ver. 6 statistical software. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Means were compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc test or two-tailed Student’s t-test when necessary. Statistical significance was considered when p values were <0.05. Statistical outliers were performed out with Grubbs' test and were removed from the analysis.

Results

BBB Permeation Assay for I2-IR Ligands MCR5 and MCR9

The tested compounds MCR5 and MCR9 had Pe values of 13.5±0.9 and 26.9±1.7, respectively, well above the threshold for high BBB permeation, so they were predicted to be able to cross the BBB and reach their biological target in the CNS. Supplementary information on results analysis can be found in the supporting material (Table 3).

Hypothermic Effects of MCR9 in Mice

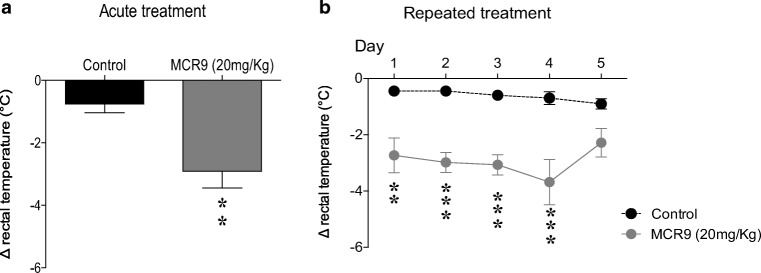

Selective I2-IR ligands induce hypothermia in rodents [4]. In particular, the hypothermic effect of compound MCR5 in mice was evaluated in a recent study from our research group (results for compound 2c in ref 35) [35]. Similar to MCR5, MCR9 induced mild hypothermia as assessed by a moderate reduction (-2.3°C) in rectal temperature 1 h after injection at the tested dose of 20 mg/kg in adult CD-1 mice and as compared with vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 3a, day 1). While repeated (5 days) administration (20 mg/kg) revealed persistently the hypothermic effects of MCR9 from days 1 to 4 (range from -2.3 to -3.2°C), on day 5 no significant change was observed in body temperature (-1.8°C change) as compared with vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Acute and repeated measurement of the hypothermic effect of compound MCR9 in mice. a Effect of acute treatment with MCR9 (20 mg/kg, i.p.) on rectal body temperature in mice. Columns are means ± SEM of the difference (Δ, 1 h - basal value) in body temperature (°C) for MCR9-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated Control mice. Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test. **p<0.01. b Effect of repeated (5 days) treatments with MCR9 (20 mg/kg, i.p., closed circles) on rectal body temperature in mice. Circles are means ± SEM of the difference (Δ, 1 h - basal value) in body temperature (°C) for MCR9-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated Controls. Data were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; (n=6−7 animals per group)

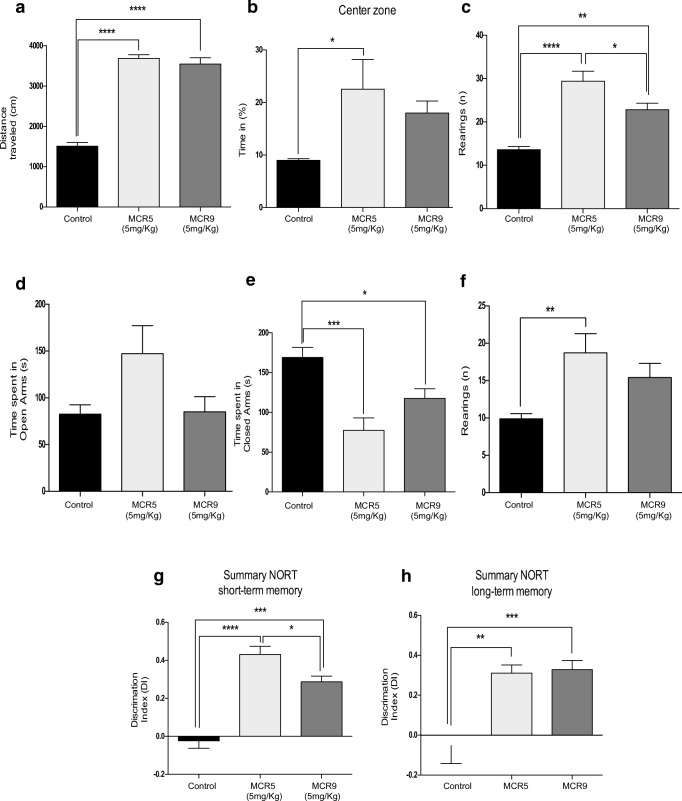

Beneficial Effects on Behavior and Cognition Induced by MCR5 and MCR9 in SAMP8 Mice

Results obtained in OFT demonstrated that both compounds increased locomotor activity and time spent in the center zone (Fig. 4a and b). Furthermore, a significant increment in the vertical activity, quantified by the number of total rears, was observed in mice treated with MCR5 or MCR9 in OFT and the EPM (Fig. 4c and f). EPM data indicated a reduction in anxiety-like behavior by a significant decrease in time spent in closed arms for treated animals compared with controls (Fig. 4e). These results are supported by a preference for opened arms, although not significant, for MCR5 (Fig. 4d). Moreover, a significant increase in the DI indicates an improved performance in recognition of the new object in the NORT between MCR5- and MCR9-treated SAMP8 mice compared with the control group. A robust effect in short (2 h) and long-term (24 h) memory was found for the two tested compounds (Fig. 4g and h).

Fig. 4.

Behavioral and cognitive improvement in 12-month-old treated SAMP8 mice with both I2-IR ligands. a A significant increase in the distance traveled in the open field test in the I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group. b A significant increase in the percentage of time in the center zone of the opened field test in the MCR5 treated group compared with the Control group, and no significant difference between the MCR9 and Control groups. c A significant increase in the number of total rears of the opened field test among groups. d The time spent in the opened arms of the EPM did not differ among groups. e A significant increase in the time spent in the closed arms among the Control group compared with the treated groups. f A significant increase in the number of total rears of the EPM in the MCR5 group compared with the Control group. g The results of the NORT in the short-term memory (2 h) revealed a significant increase in both I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group as well as a significant reduction in the DI of the MCR9 group compared with MCR5 group, and (h) a significant increase in the DI of the long-term memory (24 h) in both I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group. Data expressed as means ± SEM (n=8-10 animals per group) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001

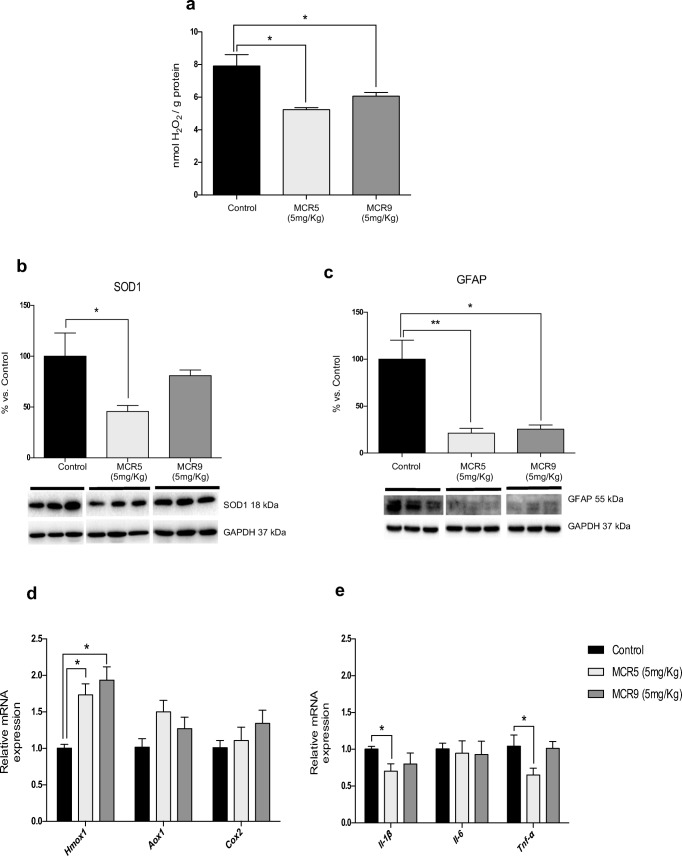

OS and Inflammatory Markers Reduced by MCR5 and MCR9 in SAMP8 Mice

OS and neuroinflammation are thought to be key risk factors in the development of neurodegeneration. The hydrogen peroxide levels in the hippocampus were significantly reduced in brains of mice treated with either MCR5 or MCR9 compared with the control group (Fig. 5a). Of note, superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) protein levels in treated mice were reduced by MCR5 but not by MCR9 (Fig. 5b). Moreover, Hmox1 gene expression, an important key enzyme in cellular antioxidant-defense, was also significantly increased with both MCR5 and MCR9 (Fig. 5d). Other OS markers, such as Aox1 or Cox2, were not significantly altered (Fig. 5d). Regarding the inflammation markers, no changes were observed in Il-6 gene expression for tested compounds, but a significant decrease in Il-1β and Tnf-α for MCR5 treated SAMP8 mice was found (Fig. 5e). Moreover, a significant diminution in Gfap gene expression was determined, reinforcing the prevention of inflammatory processes by MCR5 and MCR9 (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Reduced OS and inflammatory markers in 12-month-old treated SAMP8 mice with both I2-IR ligands. a There was a significant reduction in the hydrogen peroxide concentration in both I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group in homogenates of the hippocampus tissue. b A significant reduction in SOD1 protein levels in the MCR5 group compared with the Control group and no difference between the MCR9 and Control groups. c A significant reduction in Gfap protein levels in the MCR5 and MCR9 groups compared with the Control group. d Gene expression of antioxidant enzymes in the mouse hippocampus. A significant increase in Hmox1 gene expression, but not for Aox1 and Cox2, among both I2-IR ligand treated groups and the Control group. e A significant reduction in gene expression of Il-1β and Tnf-α in the MCR5 group compared with the Control group, and a tendency for the same genes to reduce in the MCR9 group. However, Il-6 gene expression did not differ among groups. Values in bar graphs are adjusted to 100% for protein level of the Control group. Gene expression levels were determined by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n=4-5 animals per group) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *p<0.05

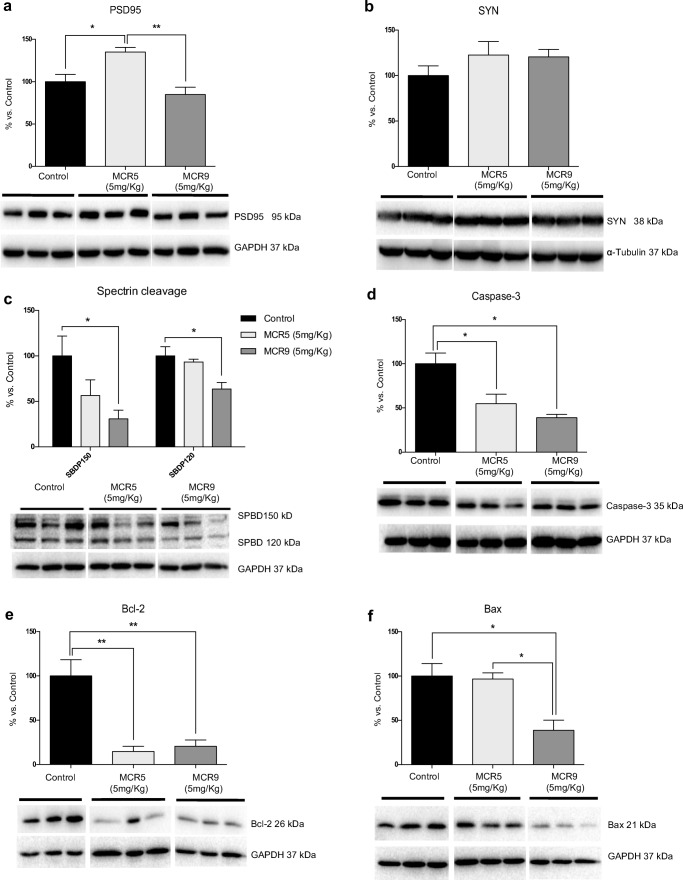

Changes in Synaptic Markers and Apoptotic Factors Induced by MCR5 and MCR9 in SAMP8 Mice

MCR5, but not MCR9, induced an increase in postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) protein levels (Fig. 6a). Protein levels for synaptophysin (SYN), a presynaptic protein, showed a slight increase for both compounds, although it did not reach significance (Fig. 6b). To determine the implication of proteolytic processes in the MCR5 and MCR9 compounds, we found reduced levels of calpain (data not shown) with a significant diminution in 150 α-spectrin breakdown fragment (SPBD) (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, MCR9 and MCR5 reduced caspase-3 activity in SAMP8 mouse hippocampi, because of the diminution of caspase-3 protein levels and 120 SPBD fragments, which reached significance for MCR9 (Fig. 6c and d). Moreover, B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) levels were diminished, and Bcl-2-associated X (Bax), a key protein in the apoptotic cascade, was reduced by MCR5 (Fig. 6e and f), supporting a possible implication of I2-IR in apoptosis processes.

Fig. 6.

Changes in synaptic markers and apoptotic factors in 12-month-old treated SAMP8 mice with both I2-IR ligands. a A significant increase in PSD95 protein levels in the MCR5 group compared with the other two groups. b A tendency for SYN protein levels to increase in both I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group. c A tendency for a reduction in the spectrin fragment SPBD 150, and a significant reduction in the spectrin fragment SPBD 120 in the MCR9 group compared with the Control group. d A significant reduction in Caspase-3 protein levels in both I2-IR ligand groups compared with the Control group. e A significant reduction in Bcl-2 protein levels in both I2-IR ligand groups compared with the Control group. f A significant reduction in Bax protein levels in the MCR9 group compared with the other groups. Values in bar graphs are adjusted to 100% for protein level of the Control group. Representative WB for each protein in the mouse hippocampus is shown. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n=5 animals per group) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *p<0.05, **p<0.001

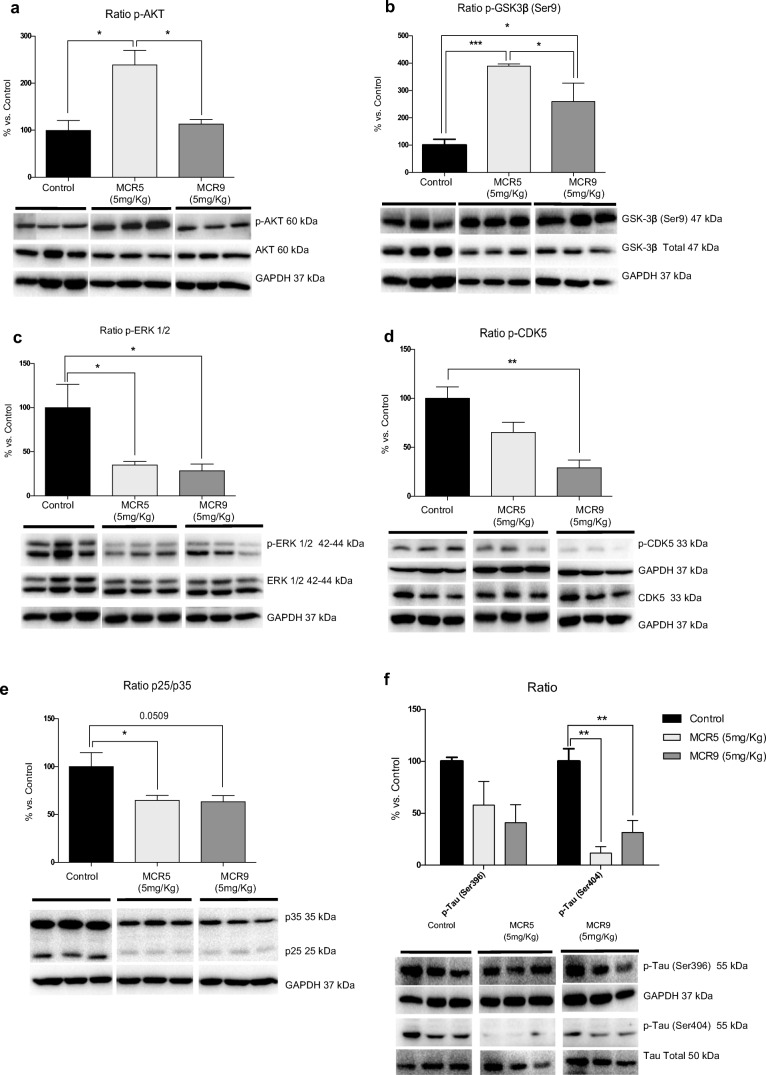

Changes in Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling Pathways Reduced Hyperphosphorylation of Tau Induced by MCR5 and MCR9 in SAMP8 Mice

Key proteins associated with molecular pathways disturbed in brain disorders and neurodegeneration were evaluated by WB. Interestingly, MCR5, but not MCR9, increased the p-AKT/AKT ratio (protein kinase B) (Fig. 7a). Accordingly, higher levels of inactivated glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), phosphorylated in Ser9, were determined (Fig. 7b). Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK½) inhibition by MCR5 and MCR9 was demonstrated by a reduction of the p-ERK½ ratio (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, cyclin-dependent kinases 5 (CDK5) measured by the p-CDK5/CDK5 and p25/p35 ratios were also reduced (Fig. 7d and e). Taking into account the results obtained on kinases CDK5, GSK3β, AKT, and ERK½, we studied Tau hyperphosphorylation levels in the hippocampi of SAMP8 mice. A significant reduction in Tau phosphorylation in treated SAMP8 mice was found, specifically for the Ser404 phosphorylation site, whereas the Ser396 phosphorylation site was reduced without reaching significance (Fig. 7f).

Fig. 7.

Changes in kinase signaling pathways reduced hyperphosphorylation of Tau in 12-month-old SAMP8 mice treated with both I2-IR ligands. a A significant increase in the p-AKT ratio in the MCR5 group compared with the other two groups. b A significant increase in inactive p-GSK3β (Ser9) protein levels in both I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group. c A significant reduction in p-ERK½ in both I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group. d Changes in the p-CDK5/CDK5 ratio induced by MCR5 and MCR9 treatment. e Changes in the p25/p35 ratio in the MCR5 and MCR9 groups compared with the Control group. Representative WB are shown. f A reduction in p-Tau (Ser396), as well as a significant reduction in p-tau (Ser404) in both I2-IR ligand treated groups compared with the Control group. Values in bar graphs are adjusted to 100% for protein level of the Control group. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n=5 animals per group) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

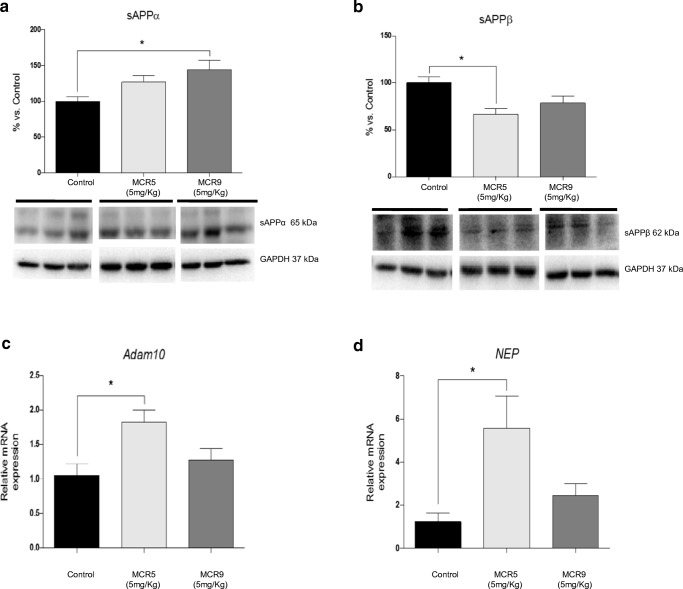

Changes in APP Processing and Aβ Degradation Induced by MCR5 and MCR9 in SAMP8 Mice

We found a significant increase in sAPPα protein levels in MCR9 treated SAMP8 mice (Fig. 8a) and a significant reduction in sAPPβ protein levels in MCR5 treated SAMP8 mice (Fig. 8b). Furthermore, a significant increase in gene expression for Adam10, an α-secretase that cleaves APP and NEP, an Aβ degrading enzyme (Fig. 8c and d), was observed in both treated mice groups compared with that in non-treated animals.

Fig. 8.

Changes in APP processing and Aβ degradation enzymes in 12-month-old SAMP8 mice treated with both I2-IR ligands. Representative WB of the APP and its fragments. a A significant increase in sAPPα protein levels in the MCR9 group compared with the Control group, and no significant difference between the MCR5 and Control groups. b A significant reduction in sAPPβ protein levels in the MCR5 group compared with the Control group, and no significant difference between the MCR9 and Control groups. c A significant increase in Adam10 gene expression in the MCR5 group compared with the Control group, and no significant difference in the MCR9 group. d A significant increase in NEP gene expression in the MCR5 group compared with the Control group, and no significant difference in the MCR9 group. Values in bar graphs were adjusted to 100% for protein level of the Control group. Gene expression levels were determined by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n=4-5 animals per group) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *p<0.05

Discussion

I2-IR are related to several physiological and pathological processes, including those of the CNS, such as pain [8], neuropathic pain [40], seizures [41, 42], and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [14, 43]. Our lab has a research line on developing new high affinity and selectivity I2-IR ligands, maintaining the imidazoline scaffold and incorporating several substituents in the imidazoline ring. Some of these were previously tested for their neuroprotective role [35].

Given the enormous potential of I2-IR and their implications in brain disorders and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, we set out to explore whether MCR5 and MCR9, two members of a structurally new family of I2-IR ligands, might improve the behavioral and cognitive status in SAMP8 model mice. The main chemical structural differences were a phosphonate substituent on the imidazoline ring for MCR5 in contrast with an ester group for MCR9 (Fig. 2).

Published results from our lab demonstrated that MCR5 presented a pKi for the I2-IR of 9.42±0.16 and high selectivity when compared with the α2 receptor affinity [35]. Likewise, MCR9 is a high-affinity I2-IR ligand (pKi 8.85±0.21) but with a higher selectivity against α2 receptors. Both MCR5 and MCR9 were predicted to be able to cross the BBB, an important drug characteristic when action is expected in the CNS.

Previous studies have evaluated the effects of selective I2-IR ligands on inducing hypothermia in rodents [e.g., idazoxan or BU224] [44]. Accordingly, MCR5 can induce hypothermia in mice, and showed a neuroprotective role in kainate-induced seizures, modifying levels of a Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) receptor [35]. While acute MCR5 (5 and 20 mg/kg) induced mild hypothermia, repeated (20 mg/kg, 5 days) administration of MCR5 revealed significantly attenuated hypothermic effects from day 2, which indicated the induction of tolerance to the hypothermic effects of the drug [35]. For MCR9, repeated (20 mg/kg, 5 days) administration revealed persistent hypothermic effects up to day 4. These results suggest that the slow induction of tolerance to the hypothermic effects caused by MCR9 might be started following 5 days of drug administration, although a more extended treatment paradigm might be needed for confirmation.

The hypothermic effects exerted by MCR5 and MCR9 might be relevant to induce neuroprotection because it was previously proposed for some of the neuroprotective effects induced by the I2-IR selective ligand idazoxan. Several experiments have ascertained a possible role for hypothermia in mediating neuroprotection. For example, small drops in temperature exerted neuroprotection in cerebral ischemia [45] and are typically used in the clinic to improve the neurological outcome under various pathological conditions (e.g., stroke, brain injury). Although the mechanisms explaining the neuroprotective effects mediated by hypothermia are not well understood, some researchers have suggested that they might be related to the inhibition of glutamate release [46].

SAMP8 mice have been studied as a non-transgenic murine mouse model of accelerated senescence and late-onset AD. These mice exhibit cognitive and emotional disturbances, probably due to the early development of pathological brain hallmarks, such as OS, inflammation, and activation of neuronal death pathways, which mainly affect the cerebral cortex and hippocampus [47, 48]. To date, this rodent model has not been used to test I2-IR ligands. Thus, this work is the first investigation of the effects of the improvement of cognitive impairment and behavior in this mouse model after treatment with I2-IR ligands.

Behavioral and cognitive effects were investigated through three well-established tests in SAMP8 mice: the OFT, which is an experiment used to assay general locomotor activity and anxiety in rodents [49]; the EPM, one of the most widely used tests for measuring anxiety-like behavior [50]; and the NORT, as a standard measure of cognition (for short- and long-term memory) [51].

The OFT and EPM parameters indicated a reduction in cognitive impairment through showing improved locomotor activity jointly with an anti-anxiousness effect. Likewise, the NORT results demonstrated an improvement in cognitive and short- and long-term learning capabilities in hippocampal memory processes. Therefore, all the assessed parameters showed robust beneficial effects on cognition and behavior after MCR5 and MCR9 treatment in SAMP8 mice.

The results in cognitive and behavioral effects were supported by a cellular and biochemical assessment of characteristic parameters related to cognitive decline and AD. The compelling evidence demonstrated a neuroprotective role for I2-IR. The neuroprotective role can be related to OS and inflammation [52] by measuring OS indicators and inflammation markers in SAMP8 mouse brain tissue treated with the I2-IR ligands, MCR5 and MCR9. Results showed significant reduced hydrogen peroxide levels in hippocampal tissue and increased Hmox1 gene expression in treated MCR5 and MCR9 SAMP8 mice, but not in other sensors for OS, such as Aox1 or Cox2. SOD1 protein levels were reduced by MCR5 but not by MCR9. Regarding inflammation markers, no changes were observed in Il-6 gene expression for tested compounds, but a significant decrease in Il-1β and Tnf-α for MCR5 treated SAMP8 mice was found. In addition, reduced astrogliosis was found in treated animals, corroborating a reduced inflammatory environment in hippocampi of MCR5 and MCR9 treated SAMP8 mice. Altogether these results showed a relatively weak influence in OS and inflammation mechanisms by I2-IR ligands in SAMP8 mice [53–57]. However, a role for those two pathological conditions related to I2-IR ligand interaction cannot be discarded because MCR5 elicited beneficial effects despite the old age of the SAMP8 mice. Aged SAMP8 mice present lower inflammation and OS due to being at the endpoint of the senescence process [56, 57]. Therefore, it can be challenging to determine drug effects on these processes in aged SAMP8 mice.

MCR5 and MCR9 effects on key molecular markers for synapsis and apoptosis were studied to unravel the prevention of cognitive decline by I2-IR ligands in SAMP8 mice, which is characterized by alterations in those processes. In consonance with better cognitive performance, the compounds tested increased synaptic markers such as SYN and PSD95, indicating a neuroprotective role for MCR5 and MCR9.

There are several cellular and molecular pathways related to better synaptic performance, including proteolytic and phosphorylation activities or apoptotic processes. Regarding proteolytic processes, calpain is an intracellular protease that cleaves the CDK5 activator p35 to a p25 fragment. MCR5 and MCR9 diminished calpain levels and its activity with a reduced 150 SPBD fragment. Moreover, a significant reduction in p25 protein levels was found in treated SAMP8 mice. A decrease in p25 can also influence CDK5 activity, as implicated in Tau phosphorylation [58, 59]. These results indicate that CDK5 phosphorylation activity should be diminished after I2-IR ligand treatment, corroborating results obtained previously for MCR5 in a kainate model of neuronal damage [60].

Caspase 3 mediated apoptosis was also addressed. A significant reduction of caspase 3 activity and diminution of Bax protein were found in MCR9 treated SAMP8 mice. Because Bax is described as a pro-apoptotic protein, its diminution indicates a possible protective role for I2-IR ligands in neurons [61]. By contrast, reduced levels of Bcl-2, considered an anti-apoptotic protein, deserve further studies. Several authors have indicated that when Bax is reduced, Bcl-2 is less necessary for blocking Bax dimer to form the mitochondrial pore; in this situation cells reduce the Bcl-2 levels as a control mechanism [62].

An increase in p-AKT was induced by the I2-IR ligands, whereas a decrease in ERK½ activation was observed. p-AKT inactivated GSK3β, a key kinase involved in the process of Tau hiperphosphorylation, by phosphorylation in Ser9. To this point, MCR5- and MCR9-treated SAMP8 mice showed an increase of Ser9 phosphorylated GSK3β and reduced Tau hyperphosphorylation.

ERK½ inhibition (that reduction of p42/p44) by MCR5 and MCR9 can contribute to the beneficial effect elicited by I2-IR on synaptic markers and Tau phosphorylation processes. ERK½ belongs to a subfamily of MAPKs and plays diverse roles in the CNS, such as neuronal survival or death, synaptic plasticity, and learning and memory through phosphorylation of regulatory enzymes and kinases [63, 64]. Although crucial for neuronal survival, there is some evidence that prolonged activation of the ERK pathway can induce a deleterious effect to the cell [65, 66]. Interestingly, long-lasting ERK activation in neurons has been demonstrated in neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [67, 68] and PD [69]. Here, the inhibition of this kinase participates in post-translational modifications in cytoskeletal proteins such as Tau, ameliorating the neuronal network functioning, as demonstrated with an increase in synaptic markers.

The relationship among MAPKs, such as ERK½ [70], and PI3K, such as AKT, and imidazoline receptors is well defined [71, 72]. In this respect, it has been described that either ERK or AKT can be associated with the multifunctional Fas/FADD complex [73, 74]. Apoptosis is an important contributor to neurodegeneration [75], and in this regard, the FADD protein has been suggested as a putative biomarker for pathological processes associated with the course of clinical dementia [76]. It has been reported that total FADD has a central role in promoting apoptosis [77, 78] and its phosphorylation at Ser191/194 mediates non-apoptotic actions such as cell growth and differentiation [79]. In our previous work, we demonstrated that MCR5 modified FADD phosphorylation (i.e., it increased the p-FADD/FADD ratio) in a kainate-treated rat model [35]. These results could explain the modulation of proteins from the apoptotic pathway mentioned before (e.g., a diminution in caspase 3 activation and significant changes in Bcl-2 and Bax), which seems to favor anti-apoptotic actions mediated through I2-receptors, and especially by MCR5.

Tau hyperphosphorylation is a histological trend in many neurodegenerative diseases characterized by cognitive decline, including AD. Therefore, we studied APP processing pathways. Aberrant APP processing is a hallmark of cognitive decline diseases [80]. To assess the capacity of the tested compounds to modify this pathological hallmark, we evaluated APP fragments, specifically, sAPPα and sAPPβ. Despite neither APP fragment reaching significance in either I2-IR ligand-treated SAMP8 mice group, we found a clear tendency that indicates the non-amyloidogenic pathway preference. Moreover, sAPPα is described as a neuroprotective, neurotrophic and cell excitable regulator with synaptic plasticity [81]. Adam10 [82] and NEP [83] gene expression were higher in MCR5 and MCR9 treated mice groups than in non-treated animals. In sum, I2-IR ligands foster a diminution in the amyloidogenic pathway and higher degradation of β-amyloid in the SAMP8 mice model.

In conclusion, the effectiveness of the two new I2-IR ligands in an in vivo female model for cognitive decline was demonstrated in this study. SAMP8 model mice are gated to neurodegenerative processes, such as AD, and our research has shown that MCR5 and MCR9 can open new therapeutic avenues against these pathological conditions that currently have unmet medical needs. Although different authors have previously indicated the relationship between I2-IR and cognitive decline, this study is the first experimental evidence that demonstrates the possibility of using this receptor as a target for cognitive impairment. Here, we demonstrate that this strategy could represent a future approach to treating devastating conditions such as AD.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 26 kb)

(PDF 498 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain (SAF2016-77703 and SAF2014-55903-R) and the Basque Government (IT616/13). C.G.-F., F.V., F.X.S., C.E. and M.P. belong to 2017SGR106 (AGAUR, Catalonia). J.A.G.-S. is a member emeritus of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans (Barcelona, Catalonia). Financial support was provided for F.V. (University of Barcelona, APIF_2017), S.R.-A. (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018FI_B_00227) and A.B. (Institute of Biomedicine UB_2018).

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Adam10

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10

- ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- Aox1

Aldehyde oxidase 1

- AKT

Protein kinase B

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- CDK5

Cyclin-dependent kinase 5

- CNS

Central nervous system

- Cox2

Cyclooxygenase 2

- Ct

Cycle threshold

- DI

Discrimination index

- EPM

Elevated plus maze

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- FADD

Fas-associated protein with death domain

- Gfap

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GSK3β

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

- Hmox1

Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1

- I2-IR

I2-Imidazoline receptors

- Il-1β

Interleukin 1 beta

- Il-6

Interleukin 6

- MAO

Monoamine oxidases

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NEP

Neprilysin

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NORT

Novel object recognition test

- OFT

Open field test

- OS

Oxidative stress

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- Pe

Permeability

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- PSD95

Postsynaptic density protein 95

- SAMP8

Senescence accelerated mouse prone 8

- SPBD

Spectrin breakdown

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SOD1

Superoxide dismutase 1

- SYN

Synaptophysin

- TBP

Tata-binding protein

- TN

Time with new object

- Tnf-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TO

Time with old object

- WB

Western blot

Author Contributions

C.G.-F. and F.V. contributed equally. C.G.-F., C.E., L.F.C. and M.P. designed the study. B.P. performed the PAMPA-BBB permeation experiments. C.G.-F. and F.V. carried out the behavior and cognition studies and cellular parameters determination (OS and inflammation markers, synaptic markers and apoptotic factors, and hyperphosphorylation of Tau). J.A.G.-S. and M.J.G.-F. performed the hypothermic studies. S.A., S.R.-A. and A.B. synthesized and purified the l2-IR ligands. C.G.-F., L.F.C., F.X.S., J.A.G.-S., M.J.G.-F., C.E. and M.P. contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Christian Griñán-Ferré and Foteini Vasilopoulou contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bousquet P, Feldman J, Schwarts J. Central cardiovascular effects of alpha-adrenergic drugs: differences between catecholamines and imidazolines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1984;230:232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Head GA, Mayorov DN. Imidazoline receptors, novel agents and therapeutic potential. Cardiovasc. Hematol Agents Med. Chem. 2006;4:17–32. doi: 10.2174/187152506775268758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowry JA, Brown JT. Significance of the imidazoline receptors in toxicology. Clin. Toxicol. 2014;52:454–469. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.898770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JK. Imidazoline I2 receptors: An update. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017;178:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton C, Keating GM, Lyseng-Williamson KA. Moxonidine: a review of its use in essential hypertension. Drugs. 2006;6:477–496. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid JL. Rilmenidine: A clinical overview. Am. J. Hypertens. 2000;13:106S–111S. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(00)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olmos G, Alemany R, Boronat MA, García-Sevilla JA. Pharmacologic and molecular discrimination of I2-imidazoline receptor subtypes. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;881:144–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li JX, Zhang Y. Imidazoline I2 receptors: target for new analgesics? Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;658:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callado LF, Martín-Gomez JI, Ruiz J, Garibi J, Meana JJ. Imidazoline I2 receptors density increases with the malignancy of human gliomas. J. Neurol., Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2004;75:785–787. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.020446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regunathan S, Feinstein DL, Reis DJ. Anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory actions of imidazoline agents. Are imidazoline receptors involved? Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;881:410–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruíz J, Martín I, Callado LF, Meana JJ, Barturen F, García-Sevilla JA. Non-adrenoreceptor [3H] idazoxan binding sites (I2-imidazoline sites) are increased in postmortem brain from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;160:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90925-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Sevilla JA, Escribá PV, Walzer C, Bouras C, Guimón J. Imidazoline receptor proteins in brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;247:95–98. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gargalidis-Moudanos C, Pizzinat N, Javoy-Agid F, Remaury A, Parini A. I2-imidazoline binding sites and monoamine oxidase activity in human postmortem brain from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 1997;30:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0186(96)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meana JJ, Barturen F, Martín I, García-Sevilla JA. Evidence of increased non-adrenoreceptor [3H]idazoxan binding sites in the frontal cortex of depressed suicide victims. Biol. Psychiatry. 1993;34:498–501. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Sevilla JA, Escribá PV. Sastre, et al. Immunodetection and quantitation of imidazoline receptor proteins in platelets of patients with major depression and in brains of suicide victims. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:803–810. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830090049008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith KL, Jessop DS, Finn DP. Modulation of stress by imidazoline binding sites: implications for psychiatric disorders. Stress. 2009;12:97–114. doi: 10.1080/10253890802302908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Comi E, Lanza M, Ferrari F, Mauri V, Caselli G, Rovati LC. Efficacy of CR4056, a first-in-class imidazoline-2 analgesic drug, in comparison with naproxen in two rat models of osteoarthritis. J. Pain Res. 2017;10:1033–1043. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S132026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regunathan S, Reis DJ. Imidazoline receptors and their endogenous ligands. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;36:511–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dardonville C, Rozas I. Imidazoline binding sites and their ligands: an overview of the different chemical structures. Med. Res. Rev. 2004;24:639–661. doi: 10.1002/med.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boronat MA, Olmos G, García-Sevilla JA. Attenuation of tolerance to opioid-induced antinociception and protection against morphine-induced decrease of neurofilament proteins by idazoxan and other I2-imidazoline ligands. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:175–185. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald GR, Olivieri A, Ramsay RR, Holt A. On the formation and nature of the imidazoline I2 binding site on human monoamine oxidase B. Pharmacol. Res. 2010;62:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casanovas A, Olmos G, Ribera J, Boronat MA, Esquerda JE, García-Sevilla JA. Induction of reactive astrocytosis and prevention of motoneuron cell death by the I2-imidazoline receptor ligand LSL 60101. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1767–1776. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gustafson I, Westerberg E, Wieloch T. Protection against ischemia-induced neuronal damage by the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist idazoxan: influence of time of administration and possible mechanisms of action. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:885–894. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu WW, Zheng RY. Neuroprotective effects of receptor imidazoline 2 and its endogenous ligand agmatine. Neurosci. Bull. 2006;22:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilad GM, Gilad VH. Accelerated functional recovery and neuroprotection by agmatine after spinal cord ischemia in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;296:97–100. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han Z, Xiao MJ, Shao B, Zheng RY, Yang GY, Jin K. Attenuation of ischemia induced rat brain injury by 2-(-2-benzofuranyl)-2-imidazoline, a high selectivity ligand for imidazoline I(2) receptors. Neurol. Res. 2009;31:390–395. doi: 10.1179/174313209X444116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maiese K, Pek L, Berger SB, Reis DJ. Reduction in focal cerebral ischemia by agents acting at imidazole receptors. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:53–63. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang SX, Zheng RY, Zheng JQ, Li XL, Han Z, Hou ST. Reversible inhibition of intracellular calcium influx through NMDA receptors by imidazoline (I)2 receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;629:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruggiero DA, Regunathan S, Wang H, Milner TA, Reis DJ. Immunocytochemical localization of an imidazoline receptor protein in the central nervous system. Brain Res. 1998;780:270–293. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olmos G, Alemany R, Escriba PV, García-Sevilla JA. The effects of chronic imidazoline drug treatment on glial fibrillary acidic protein concentrations in rat brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;111:997–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez-Arellano JJ, Parpura V, Zorec R, Verkhratsky A. Astrocytes in physiological aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2016;323:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martín-Gómez JI, Ruíz J, Barrondo S, Callado LF, Meana JJ. Opposite changes in Imidazoline I2 receptors and α2-adrenoceptors density in rat frontal cortex after induced gliosis. Life Sci. 2005;78:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sica DA. Alpha 1-adrenergic blockers: current usage considerations. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2005;7:757–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.05300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abás S, Estarellas C, Luque FJ, Escolano C. Easy access to (2-imidazolin-4-yl)phosphonates by a microwave assisted multicomponent reaction. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:2872–2881. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2015.03.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abás S, Erdozain AM, Keller B, et al. Neuroprotrective effects of a structurally new family of high affinity imidazoline I2 receptors ligands. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017;8:737–742. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morley JE, Farr SA, Kumar VB, Armbrecht HJ. The SAMP8 mouse: a model to develop therapeutic interventions for Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012;18:1123–1130. doi: 10.2174/138161212799315795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di L, Kerns EH, Fan K, McConnell OJ, Carter GT. High throughput artificial membrane permeability assay for blood-brain barrier. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003;38:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S0223-5234(03)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGrath JC, Lilley E. Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015;172:3189–3193. doi: 10.1111/bph.12955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ennaceur A, Delacour J. A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: Behavioral data. Behav. Brain Res. 1988;31:47–59. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(88)90157-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrari F, Fiorentino S, Mennuni L, Garofalo P, Letari O, Mandelli S, Giordani A, Lanza M, Caselli G. Analgesic efficacy of CR4056, a novel imidazoline-2 receptor ligand, in rat models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. 2011;4:111-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Jackson HC, Ripley TL, Dickinson SL, Nutt DJ. Anticonvulsant activity of the imidazoline 6,7-benzoidazoxan. Epilepsy Res. 1991;9(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(91)90022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min JW, Peng BW, He X, Zhang Y, Li JX. Gender difference in epileptogenic effects of 2-BFI and BU224 in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;718(1-3):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keller B, García-Sevilla JA. Immunodetection and subcellular distribution of imidazoline receptor proteins with three antibodies in mouse and human brains: Effects of treatments with I1- and I2-imidazoline drugs. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(9):996–1012. doi: 10.1177/0269881115586936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorn DA, An XF, Zhang Y, Pigini M, Li JX. Characterization of the hypothermic effects of imidazoline I2 receptor agonist in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;166:1936–1945. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Craven JA, Conway EL. Effects of alpha 2-adrenoceptor antagonists and imidazoline 2-receptor ligands on neuronal damage in global ischemia in the rat. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1997;24:204–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Illevich UM, Zornow MH, Choi KT, Scheller M, Strnat MA. Effects of hypothermic metabolic suppression on hippocampal glutamate concentrations after transient global cerebral ischemia. Anesth. Analg. 1994;78:905–911. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeda T. Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM) with special references to neurodegeneration models, SAMP8 and SAMP10 mice. Neurochem. Res. 2009;34:639–659. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9922-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pallàs M. Senescence-accelerated mice P8: a tool to study brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease in a mouse model. ISRN Cell Biol. 2012:1-12.

- 49.Archer J. Tests for emotionality in rats and mice: A review. Anim. Behav. 1973;21:205–235. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(73)80065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dawson GR, Tricklebank MD. Use of the elevated plus maze in the search for novel anxiolític agents. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995;16:33–36. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)88973-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antunes M, Biala G. The novel object recognition memory: neurobiology, test procedure, and its modifications. Cogn. Process. 2012;13:93–110. doi: 10.1007/s10339-011-0430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao H-M, Zhou H, Oxidative Stress HJS. Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegeneration. In: Peterson PK, Toborek M, editors. Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujibayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Waki A, Konishi J, Yonekura Y. Increased mitochondrial DNA deletion in the brain of SAMP8, a mouse model for spontaneous oxidative stress brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;254:109–112. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00667-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sureda FX, Gutierrez-Cuesta J, Romeu M, Mulero M, Canudas AM, Camins A, Mallol J, Pallàs M. Changes in oxidative stress parameters and neurodegeneration markers in the brain of the senescence-accelerated mice SAMP-8. Exp. Gerontol. 2006;41:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gutierrez-Cuesta J, Sureda FX, Romeu M, Canudas AM, Caballero B, Coto-Montes A, Camins A, Pallàs M. Chronic administration of melatonin reduces cerebral injury biomarkers in SAMP8. J. Pineal Res. 2007;42:394–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griñán-Ferré C, Palomera-Avalos V, Puigoriol-Illamola D, Camins A, Porquet D, Plà V, Aguado F, Pallàs M. Behaviour and cognitive changes correlated with hippocampal neuroinflammaging and neuronal markers in SAMP8, a model of accelerated senescence. Exp. Gerontol. 2016;80:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Griñan-Ferré C, Puigoriol-Illamola D, Palomera-Ávalos V, et al. Environmental enrichment modified epigenetic mechanisms in SAMP8 mouse hippocampus by reducing oxidative stress and inflammaging and achieving neuroprotection. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao L, Tian S, Gao H. Xu Y. Hypoxia increases Abeta-induced tau phosphorylation by calpain and promotes behavioral consequences in AD transgenic mice. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2013;51:138–147. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-9966-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kimura T, Ishiguro K, Hisanaga S. Physiological and pathological phosphorylation of tau by Cdk5. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2014;7:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keller B, García-Sevilla JA. Regulation of hippocampal Fas receptor and death-inducing signaling complex after kainic acid treatment in mice. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;3(63):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng EH, Wei MD, Weiler S, Flavell RA, Mak TW, Lindster T, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2, BCL-X(L) sequester BH3 domain-only molecules preventing BAX- and BAK-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:705–711. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin LJ. Mitochondrial and Cell Death Mechanisms in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:839–915. doi: 10.3390/ph3040839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sweatt JD. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hardingham GE, Bading H. Synaptic versus extransynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:682–696. doi: 10.1038/nrn2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imajo M, Tsuchiya Y, Nishida E. Regulatory mechanisms and functions of MAP Kinase signalling pathways. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:312–317. doi: 10.1080/15216540600746393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cruz CD, Cruz F. The ERK 1 and 2 pathway in the nervous system: from basic aspects to possible clinical applications in pain and visceral dysfunction. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2007;5:244–252. doi: 10.2174/157015907782793630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hyman BT, Elvhage TE, Reiter J. Extracellular signal regulated kinases. Localization of protein and mRNA in the human hippocampal formation in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1994;144:565–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Russo C, Dolcini V, Salis S, Venezia V, Zambrano N, Russo T, Schettini G. Signal transduction through tyrosine-phosphorylated C-terminal fragments of amyloid precursor protein via an enhanced interaction with Shc/Grb2 adaptor proteins in reactive astrocytes of Alzheimer’s disease brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:35282–35288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kulich SM, Chu CT. Sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation by 6-hydroxydopamine: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2001;77:1058–1066. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montolio M, Gregori-Puigjané E, Pineda D, Mestres J, Navarro P. Identification of small molecule inhibitors of amyloid β-induced neuronal apoptosis acting through the imidazoline I(2) receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55(22):9838–46. doi: 10.1021/jm301055g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang F, Ding T, Yu L, Zhong Y, Dai H, Yan M. Dexmedetomidine protects against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced injury through the I2 imidazoline receptor-PI3K/AKT pathway in rat C6 glioma cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64(1):120–7. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xuanfei L, Hao C, Zhujun Y, Yanming L, Jianping Imidazoline I2 receptor inhibitor idazoxan regulates the progression of hepatic fibrosis via Akt-Nrf2-Smad2/3 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):21015–21030. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.García-Fuster MJ, Miralles A, García-Sevilla JA. Effects of opiate drugs on Fas-Associated Protein with Death Domain (FADD) and effector caspases in the rat brain: Regulation by the ERK1/2 MAP kinase pathway. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:399–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramos-Miguel A, García-Fuster MJ, Callado LF, La Harpe R, Meana JJ, García-Sevilla JA. Phosphorylation of FADD (Fas-associated death domain protein) at serine 194 is increased in the prefrontal cortex of opiate abusers: relation to mitogen activated protein kinase, phosphoprotein enriched in astrocytes of 15 kDa, and Akt signaling pathways involved in neuroplasticity. Neuroscience. 2009;161:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Papaliagkas V, Anogianaki A, Anogianakis G, Ilonidis G. The proteins and the mechanisms of apoptosis: A mini-review of the fundamentals. Hippokratia. 2007;11:108–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramos-Miguel A, García-Sevilla JA, Barr A, et al. Decreased cortical FADD protein is associated with clinical dementia and cognitive decline in an elderly community sample. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12:26. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0168-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chinnaiyan AM, O’Rourke K, Tewari M, Dixit VM. FADD, a novel death domain-containing protein, interacts with the death domain Fas and initiates apoptosis. Cell. 1997;81:505–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scott FL, Stec B, Pop C, et al. The Fas-FADD death domain complex structure unravels signalling by receptor clustering. Nature. 2009;457:1019–1022. doi: 10.1038/nature07606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alappat EC, Feig C, Boyerinas B, et al. Phosphorylation of FADD at serine 194 by CKIα regulates its nonapoptotic activities. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;34:185–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gralle M, Botelho MG, Wouters FS. Neuroprotective secreted amyloid precursor protein acts by disrupting amyloid precursor protein dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;284:15016–15025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808755200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lichtenthaler SF. Alpha-secretase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein: proteolysis regulated by signaling pathways and protein trafficking. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:165–177. doi: 10.2174/156720512799361655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.El-Amouri SS, Zhu H, Yu J, Marr R, Verma IM, Kindy MS. Neprilysin: An Enzyme Candidate to Slow the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;172:1342–1354. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 26 kb)

(PDF 498 kb)