Abstract

Intramembrane cleavage of the β-amyloid precursor protein C99 substrate by γ-secretase is implicated in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Biophysical data have suggested that the N-terminal part of the C99 transmembrane domain (TMD) is separated from the C-terminal cleavage domain by a di-glycine hinge. Because the flexibility of this hinge might be critical for γ-secretase cleavage, we mutated one of the glycine residues, G38, to a helix-stabilizing leucine and to a helix-distorting proline. Both mutants impaired γ-secretase cleavage and also altered its cleavage specificity. Circular dichroism, NMR, and backbone amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange measurements as well as molecular dynamics simulations showed that the mutations distinctly altered the intrinsic structural and dynamical properties of the substrate TMD. Although helix destabilization and/or unfolding was not observed at the initial ε-cleavage sites of C99, subtle changes in hinge flexibility were identified that substantially affected helix bending and twisting motions in the entire TMD. These resulted in altered orientation of the distal cleavage domain relative to the N-terminal TMD part. Our data suggest that both enhancing and reducing local helix flexibility of the di-glycine hinge may decrease the occurrence of enzyme-substrate complex conformations required for normal catalysis and that hinge mobility can thus be conducive for productive substrate-enzyme interactions.

Introduction

Proteolysis in the hydrophobic core of membranes is a fundamental cellular process that mediates critical signaling events as well as membrane protein turnover (1). Intramembrane proteases are polytopic membrane proteins carrying their active-site residues in transmembrane helices (2). Apart from the fact that they typically cleave their substrates within the transmembrane domain (TMD), little is still known about the substrate determinants of intramembrane proteases because they typically do not recognize consensus sequences, as observed with most soluble proteases. Soluble proteases are known to cleave their substrates within extended sequences (i.e., β-strands) or loops (3), and cleavage sites that reside in α-helices (4, 5) are assumed to be intrinsically prone to unfolding (6). Therefore, rather than sequence motifs, the innate dynamics of substrate TMD helices is now increasingly discussed as a critical factor for substrate recognition and/or the cleavage reaction (7, 8). Helix flexibility could be induced by, e.g., glycine residues in case of substrates of signal peptide peptidase (SPP) (9), the related SPP-like protease SPPL2b (10), and rhomboid (11). In the case of the site-2 protease SREBP substrate, a short helix-distorting asparagine-proline motif is thought to affect substrate recognition and/or cleavage (12, 13).

γ-Secretase is a pivotal intramembrane protease complex (14, 15) that cleaves a plethora of type I membrane protein substrates, including signaling proteins essential for life such as Notch1 as well as the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is central to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (16, 17). It is widely believed that an aberrant generation and accumulation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) in the brain triggers the disease (18, 19). Aβ is a heterogeneous mixture of secreted small peptides of 37–43 amino acids. Besides the major form Aβ40, the highly aggregation-prone longer forms Aβ42 and Aβ43 are pathogenic Aβ variants (18, 19). Aβ species are generated by γ-secretase from an APP C-terminal fragment (CTF; C99) that originates from an initial APP cleavage by β-secretase (15, 20). C99 is first endoproteolytically cleaved in its TMD by γ-secretase at the ε-sites close to the cytoplasmic TMD border to release the APP intracellular domain (AICD) and then processed stepwise by tripeptide-releasing C-terminal trimming in two principal product lines, thereby releasing the various Aβ species from the membrane (21, 22). Mutations in presenilin, the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase, are the major cause of familial forms of Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) and are associated with increased Aβ42 to total Aβ ratios (15, 23). Rare mutations in the cleavage region of the C99 TMD also shift Aβ profiles and represent another cause of FAD (15, 23).

The molecular properties of substrates that are recognized by γ-secretase are still largely enigmatic. Established general substrate requirements are not only the presence of a short ectodomain (24, 25), which is typically generated by sheddases such as α- or β-secretase, but, equally important, also permissive transmembrane and intracellular substrate domains (26). Recent studies suggest that the recruitment of C99 to the active site occurs in a stepwise process involving initial binding to exosites (i.e., substrate-binding sites outside the active site) in the nicastrin, PEN-2, and presenilin-1 (PS1) N-terminal fragment subunits of γ-secretase (27). Finally, before catalysis, interactions of C99 with the S2′ subsite pocket of the enzyme are critical for substrate cleavage and Aβ product line selection (22).

Kinetic studies have shown that intramembrane proteolysis is a surprisingly slow process in the minute range, i.e., much slower than cleavage by soluble proteases (28, 29, 30). The basis for the slow kinetics is not yet understood. With regard to C99 cleavage by γ-secretase, one reason could be that slow unwinding of the TMD helix at the initial ε-sites is rate limiting. This view is in line with biophysical studies demonstrating that the helical structure of the C99 TMD is extremely stable, particularly in its C-terminal region harboring the ε-sites (31). Indeed, a detailed recent analysis showed that di-glycine motifs introduced near the ε-sites enhance the initial cleavage, supporting the view that the helix must be locally destabilized to allow the cleavage reaction to occur (32). On the other hand, several reports also indicated that other regions than that harboring the cleavage sites of C99 play an important role for γ-secretase cleavage. For instance, mutations introduced at the luminal juxtamembrane boundary (33, 34), as well as within the N-terminal part of the TMD (i.e., at sites distant from the cleavage region), can alter cleavage efficiency and shift cleavage sites (35, 36). Furthermore, local destabilization and the length of the membrane-anchoring domains at the cytosolic juxtamembrane boundary, as well as β-sheet segments within the extracellular domain of C99, have been reported as important players for γ-secretase cleavage of C99 (37, 38, 39). Interestingly, NMR structures in detergent micelles (40, 41) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in membrane bilayers (42, 43, 44, 45, 46) suggested that the C99 TMD also contains a flexible hinge region at the G37G38 residues, which may provide the necessary flexibility for the interaction with the enzyme (7, 8, 43, 45, 46). Remarkably, although most C99-related FAD mutations are in the vicinity of the cleavage sites (15), these mutations do not destabilize H-bonds at the ε-sites but have a major impact on upstream H-bond stability, including the region around the G37G38 hinge (47, 48). The latter biophysical studies indicate that the G37G38 motif may play a crucial role in coordinating large-scale bending movements of the C99 TMD, which might facilitate the C-terminal part of the helix to move into the active site of γ-secretase (7, 49, 50). Interestingly, earlier studies with a different focus found that certain mutations at the G37G38 hinge can diversely affect γ-secretase cleavage efficiency (27, 51).

Because it is thus possible that the innate flexibility of the C99 TMD enabled by the G37G38 hinge could play a role for γ-secretase cleavage and because a link of biochemical assays of substrate cleavage with biophysical studies of backbone dynamics is still missing, we aimed to address the following questions: 1) how intrinsic structural and dynamic properties of different domains of the TMD, such as local conformation, H-bond instability, bending propensity and relative spatial orientation, are interrelated; 2) whether conformational changes of the C99 TMD allowed by its intrinsic properties play a role in the initial encounter with the enzyme, its fitting into the active site, and/or the subsequent catalytic event; and 3) whether the local unfolding of the helix required for initial substrate cleavage depends on the intrinsic structural and dynamic properties of the domain harboring the ε-sites or is rather determined by the interaction of the latter domain with the enzyme.

To modulate G37G38 hinge bending, we generated two mutations of the C99 TMD. A G38L mutation was introduced to reduce helix flexibility and a G38P mutation to increase bending, considering the classical helix-breaking potential of proline in soluble (52) and membrane proteins (53). Assuming that a less flexible G37G38 hinge would impair the presentation of the cleavage domain to the active site, we hypothesized that the G38L mutation would reduce γ-secretase cleavage, whereas the G38P mutation would have the opposite effect. Additionally, we expected contrary effects of the G38L and G38P mutations on the dynamic properties of the C99 TMD, such as the intrinsic H-bond stability and relative spatial orientation of the distal region harboring the ε-sites.

In an interdisciplinary approach, we combined γ-secretase cleavage assays of recombinant full-length C99-derived substrates with biophysical measurements and MD simulations of peptides comprising the TMD of C99 to study its intrinsic structural and dynamical properties in model membranes composed of POPC, i.e., before binding to the enzyme. In addition, we used a trifluoroethanol/water (TFE/H2O) mixture, a well-established α-helix-stabilizing hydrophobic yet hydrated solvent that has been used previously to mimic the interior of proteins (54, 55), as well as the catalytic cleft of γ-secretase (31, 46, 47, 48, 49, 56, 57). In particular, we asked whether cleavability could be correlated with G37G38 hinge-linked structural and dynamical properties of the TMD per se and, if so, what kind of properties would be functionally relevant.

Surprisingly, γ-secretase cleavage of both the G38L and particularly the G38P mutant of C99 was decreased compared to the wild type (WT), although the biophysical studies of the C99 TMD peptides corroborated the expected “stiffening” and “loosening” effects of the G38L and G38P mutants, respectively. Furthermore, effects of the G38 mutations on H-bond stability in the C99 TMD were observed only in the vicinity of the hinge and did not extend to residues around the ε-cleavage sites. MD simulations demonstrated that altered hinge flexibility leads to mutant specific distortions of the relative orientations of the helical turn harboring the ε-sites, which may consequently alter the interaction of the substrate with the active site of the enzyme, thereby impairing efficiency of the initial cleavage of both mutants. Our data thus suggest that complex global motions of the C99 TMD, controlled by the G37G38 hinge, may determine proper positioning of the substrate at the active site of the enzyme.

Materials and Methods

Materials

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) as well as sn-1 chain perdeuterated POPC-d31 were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). 1,1,1-3,3,3-Hexaflouroisopropanol (HFIP) and 2,2,2-TFE were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Peptides

For all circular dichroism (CD), solution NMR, solid-state NMR (ssNMR), and D/H exchange (DHX) experiments, C9926–55, a 30-amino-acid-long peptide comprising residues 26–55 of C99 (C99 numbering; see Fig. 1 A) with N-terminal acetylation and C-terminal amidation was used. WT peptide and G38L and G38P mutants thereof (Table 1) were purchased from Peptide Specialty Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany and from the Core Unit Peptid-Technologien, University of Leipzig, Germany. For electron transfer dissociation (ETD) measurements, to enhance fragmentation efficiency, we substituted the N-terminal SNK sequence of C9926–55 with KKK. In all cases, purified peptides were >90% purity, as judged by mass spectrometry (MS).

Figure 1.

C99 G38P and G38L mutants distinctly alter γ-secretase cleavage and processivity. (A) The primary structure of C99 (Aβ numbering) and its major γ-secretase cleavage sites are shown. (B) Levels of AICD were analyzed by immunoblotting after incubation of C100-His6 WT and mutant constructs with CHAPSO-solubilized HEK293 membrane fractions at 37°C. As controls, samples were incubated at 4°C or at 37°C in the presence of the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 (60). (C) Quantification of AICD levels from (B) is shown. Values are shown as a percentage of the WT, which was set to 100%. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3, each n represents the mean of three technical replicates). (D and E) Corresponding analysis of Aβ is shown. (F) Representative MALDI-TOF spectra of the different Aβ species generated for WT and the G38 mutants are shown. The intensities of the highest Aβ peaks were set to 100% in the spectra.

Table 1.

Sequences of Investigated Peptides

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| C9926–55 | Ac-SNKGAIIGLMVGGVVI ATVIVITLVMLKKK-NH2 |

| C9926–55 G38L | Ac-SNKGAIIGLMVGLVVI ATVIVITLVMLKKK-NH2 |

| C9926–55 G38P | Ac-SNKGAIIGLMVGPVVI ATVIVITLVMLKKK-NH2 |

| KKK-C9926–55 | Ac-KKKGAIIGLMVGGVVI ATVIVITLVMLKKK-NH2 |

| InsW-C9926–55 | Ac-SNKWGAIIGLMVGGVVI ATVIVITLVMLKKK-NH2 |

γ-Secretase in vitro assay

C99-based WT and mutant substrates were expressed in Escherichia coli as C100-His6 constructs (C99 fusion proteins containing an N-terminal methionine and a C-terminal His6 tag) (58) and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. To analyze their cleavability by γ-secretase, 0.5 μM of the purified substrates was incubated overnight at 37°C with 3-([3-cholamidopropyl]dimethylammonio)-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPSO)-solubilized HEK293 membrane fractions containing γ-secretase as described (59). Incubations in the presence of the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 (60) (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA) or at 4°C served as controls. Generated Aβ and AICD were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibody 2D8 (61) and Penta-His (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), respectively, and quantified by measuring the chemiluminescence signal intensities with the LAS-4000 image reader (Fujifilm Life Science, USA). Analysis of γ-secretase activity was repeated with three independent substrate purifications in three technical replicates for each of the constructs.

MS analysis of Aβ species

Aβ species generated in the γ-secretase vitro assays were immunopreciptated with antibody 4G8 (Covance) and subjected to MS analysis on a 4800 MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight)/TOF Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA/MDS SCIEX, Framingham, MA) as described previously (62, 63).

CD and UV spectroscopy

C9926–55 WT and G38L and G38P mutant peptides were incorporated into large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) composed of POPC at a lipid/protein molar ratio of 30:1. First, 500 μg peptide and 3.72 mg POPC were comixed in 1 mL HFIP. After evaporation of the HFIP, the mixture was dissolved in 1 mL cyclohexane and lyophilized. The resulting fluffy powder was dissolved in 977 μL buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4)). After 10 freeze-thaw cycles, LUVs were prepared by extrusion using a 100-nm polycarbonate membrane and a LipoFast extruder device (Armatis, Mannheim, Germany). CD spectra were recorded with a Jasco 810 spectropolarimeter. A cuvette with a 1 mm pathlength was filled with 200 μL of the LUV-C9926–55 preparation in which the final peptide concentration was 83 μM and the lipid concentration 2.5 mM. Mean molar residue ellipticities ([Θ]) were calculated based on the peptide concentrations. The ultraviolet (UV) absorbance at 210 nm of the WT peptide was used as a reference to normalize the final concentration of the reconstituted mutant peptides. Alternatively, for the peptides dissolved in TFE/H2O (80/20 v/v), the concentrations were determined using the UV absorbance of the peptide bond at 205 nm. The calculated extinction coefficient at 205 nm was the same (ε205 = 87.5 × 103 M−1 cm−1) for the WT and G38 mutants based on the sequences for the C9926–55 WT and mutant peptides (64). Additionally, an experimental value of ε205 = 73.6 × 103 M−1 cm−1 for a homologous peptide (InsW-C9926–55, Table 1) dissolved in TFE/H2O was determined calibrating with ε280 = 5600 mol−1 cm−1 of the additional tryptophan.

Solution NMR

Dry C9926–55 WT (15N/13C-labeled at positions G29, G33, G37, G38, I41, V44, M51, and L52) and G38L and G38P mutant peptides were dissolved in 500 μL 80% TFE-d3 and 20% H2O, respectively. pH was adjusted to 5.0 by adding the corresponding amount of NaOH. Peptide concentrations ranged between 50 and 500 μM. The NMR spectra of the peptides were obtained on a 600 MHz AVANCE III spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Rheinstetten, Germany) equipped with a TXI cryoprobe at a temperature of 300 K. To assign 1H and 13C resonances of the peptides, a set of two-dimensional spectra was recorded: 1H-1H-TOCSY with a mixing time of 60 ms, 1H-1H-NOESY with a mixing time of 200 ms, and 1H-13C-HSQC. Spectra were recorded with 24 scans and 1000 data points in the indirect dimension. The NMR spectra were analyzed using NMRViewJ (One Moon Scientific).

For H/D exchange (HDX) measurements (NMR-HDX), dry peptides were dissolved in 80% TFE-d3 and 20% D2O. Measurements were done at at least three different pH values to access all exchangeable protons, using the correlation of exchange rate and pH value. pH was adjusted using NaOD and DCl. 11 TOCSY or ClipCOSY (65) spectra with an experimental time of 3 h 26 min each (mixing time 30 ms, 24 scans, 300 data points in the indirect dimension) were acquired sequentially. Additionally, 11 1H-15N-HSQC spectra of the WT were recorded (two scans, 128 points in the indirect dimension) in between.

The exchange of the first five to six and the last two residues was too fast to measure. M35 and A42 cross peak intensities were significantly lower than those of other amino acids. The HDX rate constant (kexp,HDX) was obtained fitting the crosspeak intensities over time to Eq. 1:

| (1) |

where t is time and a and c are constants. Rate constants were calculated for all three pH values and then scaled to pH 5.

ssNMR

For ssNMR, A30, G33, L34, M35, V36, G37, A42, and V46 were labeled in the C9926–55 WT peptide with 13C and 15N. In the two mutant peptides, only A30, L34, V36, and G37 were labeled as a compromise between expensive labeling and the highest information impact to be expected. Multilamellar vesicles were prepared by cosolubilizing POPC and the selected C9926–55 peptide in HFIP at a 30:1 molar ratio. After evaporation of the solvent in a rotary evaporator, the sample film was dissolved by vortexing in cyclohexane. Subsequently, the samples were lyophilized to obtain a fluffy powder. The powder was hydrated with buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)) to achieve a hydration level of 50% (w/w) and homogenized by 10 freeze-thaw cycles combined with gentle centrifugation. Proper reconstitution of the C9926–55 WT and G38 mutants into the POPC membranes was confirmed by an analysis of the 13Cα chemical shifts of A30.

13C magic-angle-spinning (MAS) NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer (resonance frequency 600.1 MHz for 1H, 150.9 MHz for 13C) using 4 and 3.2 mm double-resonance MAS probes. The cross-polarization contact time was 700 μs, and typical lengths of the 90° pulses were 4 μs for 1H and 4–5 μs for 13C. For heteronuclear two-pulse phase modulation decoupling, a 1H radio frequency field of 62.5 kHz was applied. 13C chemical shifts were referenced externally relative to tetramethylsilane. 1H-13C dipolar couplings were measured by constant-time DIPSHIFT experiments using frequency-switched Lee-Goldburg for homonuclear decoupling (80 kHz decoupling field) (66). The 1H-13C dipolar coupling was determined by simulating dipolar dephasing curves over one rotor period. These dipolar couplings were divided by the known rigid limit as reported previously (67). MAS experiments for the site-dependent order parameter were carried out at an MAS frequency of 3 kHz and a temperature of 30°C. DIPSHIFT 1H-13C order parameters were analyzed with a variant of the established GALA model (68) to evaluate RMSD values for combinations of tilt and azimuthal angles of the TMD helix, explained in detail in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

MS experiments of DHX

All mass spectrometric experiments were performed on a Synapt G2 high definition mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA). A 100 μL Hamilton gas-tight syringe was used with a Harvard Apparatus 11 plus, and the flow rate was set to 5 μL/min. Spectra were acquired in a positive-ion mode with one scan for each second and 0.1 s interscan time.

Solutions of deuterated peptide (100 μM in 80% (v/v) d1-TFE in 2 mM ND4-acetate) were diluted 1:20 with protiated solvent (80% (v/v) TFE in 2 mM NH4-acetate (pH 5.0)) to a final peptide concentration of 5 μM (at which the helices remain monomeric (46)) and incubated at a temperature of 20°C in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Incubation times were 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 min and 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. Exchange reactions were quenched by placing the samples on ice and adding 0.5% (v/v) formic acid, resulting in a pH ≈ 2.5. Mass/charge ratios were recorded and evaluated as previously described (69, 70), including a correction for the dilution factor. For ETD, we preselected the 5+ charged peptides via MS/MS and used 1,4-dicyanobenzene as a reagent. The fragmentation of peptides was performed as described (69). Briefly, ETD MS/MS scans were accumulated over 10 min scan time, smoothed (Savitzky-Golay, 2 × 4 channels), and centered (80% centroid top, heights, three channels). MS-ETD measurements were performed after 13 different incubation periods (from 1 min to 3 d) in which exchange took place at pH 5.0. Shorter (0.1 min, 0.5 min) and longer (5 d, 7 d) incubation periods were simulated by lowering the pH to 4.0 or elevating pH to 6.45, respectively, using matched periods. The differences to pH 5.0 were considered when calculating the corresponding rate constants. We note that base-catalyzed exchange is responsible for at least 95% of total deuteron exchange at pH 4.0 and above. The resulting ETD c and z fragment spectra were evaluated using a semiautomated procedure (MassMap_2017-11-16_LDK Software; MassMap KG, Freising, Germany) (47). The extent of hydrogen scrambling could not be calculated with the ammonia loss method (71) because of the blocked N-termini. However, previous experiments with similar peptides showed scrambling to be negligible under our conditions (72). During all MS-DHX experiments, a gradual shift of monomodal shaped isotopic envelopes toward lower mass/charge values was observed. This is characteristic of EX2 kinetics with uncorrelated exchange of individual deuterons upon local unfolding (73, 74).

MD simulations

The C9926–55 WT, C9926–55 G38L, and C9926–55 G38P model peptide (for sequences, see Table 1) were investigated in a fully hydrated POPC bilayer and in a mixture of 80% TFE with 20% TIP3 water (v/v). Because no experimental structures were available for the G38 mutants, we used a stochastic sampling protocol to generate a set of 78 initial start conformations (for details, see (75)).

All-atom simulations in 80% TFE and 20% TIP3 (v/v) were set up as described previously (75). Each start conformation was simulated for 200 ns using settings as described in (46). Production runs were performed in an NPT ensemble (T = 293 K, p = 0.1 MPa) using NAMD 2.11 (76). Frames were recorded every 10 ps. The last 150 ns of each simulation were subjected to analysis, leading to an effective aggregated analysis time of 11.7 μs for each peptide.

For all-atom simulations in POPC bilayers, the stochastically sampled conformations were hierarchically clustered, and the centroid of the cluster with the highest population was placed in a symmetric bilayer, consisting of 128 POPC lipids, using protocols as provided by CHARMM-GUI (77). Simulations of 2.5 μs (T = 303.15 K, p = 0.1 MPa) were performed using NAMD 2.12 (76). Frames were recorded every 10 ps. Only the last 1.5 μs of the trajectory were subjected to analysis. All atomistic simulations use the CHARMM36 force field (78). Analysis of the H-bond occupancies, tilt, and azimuthal angles, as well as bending and twisting motions, is explained in detail in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

For the analysis of substrate TMD encounter with γ-secretase, we apply the DAFT approach (79) with a coarse-grained description of POPC lipids, water, C9926–55 TMD, and γ-secretase. The use of >750 replicas per TMD starting from unbiased noninteracting initial states, sampling for at least 1 μs per replicate, and inclusion of low-amplitude backbone dynamics of γ-secretase (80) provided exhaustive sampling of potential contact sites and exceeds previous assessments of C99 binding sites with respect to both the number of replicates and simulation time (81, 82). For further details, see the Supporting Materials and Methods and (83).

Results

G38L and G38P mutations in the C99 TMD differently impair γ-secretase cleavage

To examine whether and how leucine and proline mutations in the G37G38 hinge in the TMD of C99 affect the cleavage by γ-secretase (Fig. 1 A), G38L and G38P mutants of the C99-based recombinant substrate C100-His6 (58) were purified and used to assess their cleavability in an established in vitro assay (59). As expected, AICD generation resulting from the initial ε-cleavage was reduced to ∼38% for the G38L mutant compared to WT (Fig. 1, B and C). Surprisingly, contrary to our hypothesis, ε-cleavage of the G38P mutant was even more reduced to only ∼8%. Concomitantly, Aβ levels were reduced for both G38L and G38P mutants to ∼47 and ∼16%, respectively (Fig. 1, D and E). To also investigate the impact of the mutations on the C-terminal trimming activity of γ-secretase, i.e., its processivity, we analyzed the distribution of the lengths of the Aβ species by MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 1 F). Strikingly, although Aβ40 was, as expected, the predominant species for the cleavage of the WT substrate, Aβ37 was the major cleavage product for the G38L mutant. Thus, although the initial ε-cleavage was impaired for the G38L mutant, its processivity was enhanced. Aβ40 remained the major cleavage product for the G38P mutant, but in contrast to the WT, no Aβ37 and Aβ38 species were produced. Additionally, Aβ43 was also detected for this mutant. Remarkably, for both mutants, the unusual Aβ39 species was detected, which was barely detected for the WT. Thus, for both mutants in the G37G38 hinge, γ-secretase cleavage was decreased, and the processivity was markedly and distinctly affected. We next sought to investigate the underlying basis of these observations.

G38 mutants do not alter contact probabilities with γ-secretase

Because the G38 mutations are localized close to potential TMD-TMD interaction interfaces (i.e., G29XXXG33, G33XXXG37, and G38XXXA42 motifs (43, 46)), a possible explanation for the impaired γ-secretase cleavage of the G38 mutants could be altered contact preferences with γ-secretase. To screen for contact interfaces of the C99 TMD with γ-secretase, we set up an in silico docking assay for transmembrane components (DAFT (79)) using a coarse-grained description of POPC lipids, water, C99 TMD (C9926–55), and γ-secretase. This protocol was previously shown to reliably reproduce experimentally verified protein-protein interaction sites in a membrane (79, 84).

Our calculations showed that the C9926–55 WT and both mutant peptides could principally interact with the surface of the γ-secretase complex and contact all four complex components (Fig. 2 A). In agreement with previous substrate cross-linking experiments (27), the C9926–55 showed the highest binding preference for the PS1 N-terminal fragment (NTF) (Fig. 2 A). The normalized C9926–55 proximities for each residue of γ-secretase (Fig. 2 B) indicated that the presenilin TMD2 may represent a major exosite of γ-secretase and revealed that contacts with the highest probabilities were formed between the juxtamembrane S26NK28 residues of C9926–55 and the two threonine residues T119 and T124 in the hydrophilic loop 1 between TMD1 and TMD2 of PS1 (Fig. S1). Interactions between PS1 TMD2 and the C99 TMD could mainly be attributed to contacts of the A30, G33, G37, and V40 of the C99 TMD with residues L130, L134, A137, and S141 of PS1 TMD2 (Figs. 2 C and S1). Additional contact sites of the C99 TMD at V44 and I47 are located on the same face of the C99 TMD helix as the main contact sites (Fig. 2 C). However, the probabilities of the observed dominant contacts with the enzyme were not significantly altered by the G38 mutations. Thus, based on our substrate docking simulations, the structural alterations of the C99 G38 mutant TMD helices may not cause gross alterations in initial substrate-enzyme interactions.

Figure 2.

Probability of initial contacts of C9926–55 peptides with γ-secretase is not altered for G38 mutants compared to WT, as revealed by in silico modeling of the encounter complex. (A) Kernel densities of the center-of-mass location of the C9926–55 peptide are shown. Darker colors indicate higher contact probabilities. The representation shows the parts of γ-secretase that are embedded in the membrane, pertaining to the subunits nicastrin (green), PS1 NTF (blue), PS1 CTF (cyan), APH-1a (purple), and PEN-2 (yellow). Black arrows highlight TMD2, TMD3, and TMD6 of PS1, and the active-site aspartate residues in PS1 TMD6 and TMD7 are indicated by red spheres. (B) Normalized proximities between residues of γ-secretase subunits and the C9926–55 peptide are shown. Gray areas indicate residues that are part of the indicated TMDs of PS1. (C) Normalized proximities between C9926–55 residues and TMD2 of PS1 are shown.

G38 hinge mutations cause structural changes of the C99 TMD helix

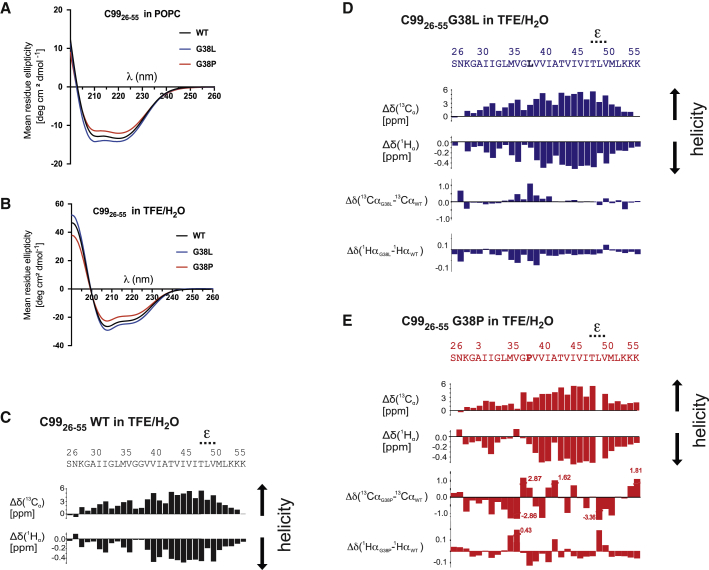

We thus next investigated how the G38 mutations affect structural and dynamical properties of the C99 TMD. To compare the effects of the G38L and G38P mutants on the helical conformation of the C99 TMD, WT, and mutant C9926–55 peptides were incorporated into LUVs composed of POPC. As shown in Fig. 3 A, CD spectroscopy measurements demonstrated that the peptides contain a high content of α-helical conformation in the lipid bilayer. As expected, the helical conformation was stabilized for the G38L (indicated by the more negative ellipticity at 220 nm) and destabilized for the G38P mutant. Similar effects were found when the peptides were analyzed in TFE/H2O (80/20 v/v) (Fig. 3 B). In this solvent, ellipticity and the shape of the spectra was different compared to POPC, but the minima at 208 and 220 nm were nevertheless indicative of a high degree of helicity.

Figure 3.

Helicity of C9926–55 TMD peptides is increased by the G38L and distorted by the G38P mutation. (A) CD spectra of C9926–55 WT and G38L and G38P mutant peptides reconstituted in POPC model membranes and (B) dissolved in TFE/H2O are shown. (C) Chemical shift indices (Δδ) for 13Cα and 1Hα atoms of each residue of C9926–55 WT obtained from solution NMR in TFE/H2O are shown. (D and E) Results of solution NMR measurements as in (C) of the G38L and G38P mutants, respectively, are shown, in which the differences between Δδ values of mutants and WT are also depicted.

The high helical content of the WT and mutant C99 TMDs was corroborated by solution NMR, in which structural information was derived from secondary chemical shifts (Δδ) (Fig. 3 C; for complete data set, see Fig. S2) and nuclear overhauser effect (NOE) patterns (Fig. S2). Over the entire TMD sequence, C9926–55 WT showed cross peaks that are typical for an ideal α-helix (containing 3.6 residues per turn; Fig. S2). Δδ(13Cα) and Δδ(1Hα) chemical shifts in particular, as well as Δδ(13Cβ), indicated a strong helicity for the C-terminal domain (TMD-C) ranging from V39 to L52 (Fig. 3 C; Fig. S2). In contrast, the N-terminal domain (TMD-N), ranging from G29 up to V36, seemed to form a less stable helix. At positions G37 and G38, the helical pattern appeared to be disturbed, which is obvious from the reduced Δδ(1Hα) values at these residues. This observed pattern of TMD-N and TMD-C domains flanking the short G37G38 segment of lower stability is consistent with previous results (40, 46, 48, 49).

With regard to the G38 mutants, no major overall changes in the NOE patterns and secondary chemical shifts were observed. However, a detailed view showed small but distinct differences in secondary chemical shifts both for G38L and G38P. G38L appeared slightly stabilized compared to the WT. Chemical shift changes were restricted to the two helical turns around L38 (M35–I41) and the immediate termini (Fig. 3 D). For G38P, the high number of differences in both Δδ(13Cα) and Δδ(1Hα) shifts compared to those of the WT values (Fig. 3 E) indicated changes in structure or stability induced by the mutation that, however, were too subtle to also result in altered NOE patterns (Fig. S2). This stems from the fact that NOEs for dynamic helices are dominated by the most stable conformation, whereas the highly sensitive chemical shifts are affected even by minuscule changes. Particularly, the helicity of the N-terminal part up to V36 had decreased for G38P according to the chemical shift pattern, but also the remaining C-terminal part showed significant and irregular deviations compared to the WT. Concomitantly, for G38P, we observed an overall increase of HN resonance line widths, which is indicative of an increased global conformational exchange (Fig. S3). Here, also, several minor alternative conformations were visible that resulted in more than one HN/Hα resonance for many residues (up to four for some residues) (Fig. S3). The overall helical conformation was also confirmed by the profile of mean-squared fluctuations obtained from the MD simulations (Fig. S4). The w-shape is a fingerprint of the large-amplitude bending motion (48), which is characteristic for helices. In POPC as well as in TFE/H2O, the G38 mutations impacted mainly local flexibility in the helix center but conserved below-average fluctuations in the cleavage domain (Fig. S4).

Taken together, consistent with the CD data, the solution NMR data and MD simulations show that the C9926–55 peptide has a high propensity to form a helical structure that is only slightly reduced in the G37G38 hinge region. Interestingly, the TMD-C, i.e., the region in which the cleavages by γ-secretase occur, has a much stronger helicity compared to the TMD-N. The G38L mutation caused a stabilization of the helix around the G37G38 hinge, albeit small, whereas the G38P mutation disturbed the helix both in its TMD-N and TMD-C parts.

G38 mutant TMD helices display altered hydrogen-bond stability around the G37G38 hinge

To further investigate the impact of the G38 mutations on conformational flexibility of the C99 TMD, we next analyzed the stability of intrahelical H-bonds of the C9926–55 WT and mutant helices. To this end, we performed backbone amide DHX experiments in TFE/H2O using MS (MS-DHX) as well as HDX using NMR (NMR-HDX). Determining amide exchange in POPC membranes was not feasible because the bilayer effectively shields central parts of the TMD helix (69, 70). Generally, although exchange rate constants also depend on the local concentration of hydroxyl ions (i.e., the exchange catalyst) and are influenced by side-chain chemistry (73), the reduced stability of backbone amide H-bonds associated with more flexible helices results in faster amide exchange. Fig. 4 A shows the overall MS-DHX of >98% deuterated C9926–55 WT and mutant peptides (5 μM) in TFE/H2O. Consistent with previous results (31, 46, 49), overall DHX kinetics was characterized by rapid deuteron exchange within minutes, followed by a relatively fast exchange over 60 min (Fig. 4 A, inset) and a subsequent very slow process. Near complete exchange was seen after 3 days. Relative to the WT, the G38L mutation slowed hydrogen exchange, whereas an apparent slight enhancement of exchange was observed for G38P. This enhancement is, however, largely ascribed to the fact that proline does not contribute an amide deuterium, thus reducing the number of exchangeable deuterons in DHX (Fig. 4 A, inset).

Figure 4.

DHX rates along the TMD of C9926–55 reveal an impact of the G38 mutations on H-bond stability around the mutation sites but not at the ε-sites. (A) Overall DHX kinetics of C9926–55 WT and G38L and G38P mutant peptides measured with MS-DHX is shown. Complete deuteration was followed by back-exchange in TFE/H2O (pH 5.0), T = 20°C. Exchange kinetics during the first 60 min (inset) and 72 h were measured (n = 3, error bars showing SD are smaller than the size of the symbols). Note that the lower deuterium content in G38P mainly resulted from the lack of one amide deuteron at the cyclic side chain of proline. (B) Site-specific DHX rate constants (kexp,DHX (min−1)) of C9926–55 WT and G38L and G38P mutants dissolved in TFE/H2O are shown, as determined by MS-ETD (error bars show 95% CI). (C) Site-specific HDX rate constants (kexp,HDX (min−1)) determined by NMR are shown (n = 3, error bars show SD). (D) Site-specific kDHX (min−1) computed from MD simulations are shown (error bars show 95% CI). (E) Backbone H-bond occupancy of the individual residues of C9926–55 WT and its G38L and G38P mutants in POPC and (F) in TFE/H2O is shown, calculated by MD simulations (error bars show 95% CI). An amide H-bond is counted as closed if either the α- or 310-H-bond is formed. Note that G38P cannot form H-bonds at residue 38 because of the chemical nature of proline.

To obtain insight into local amide H-bond strength, we next measured residue-specific amide DHX rate constants (kexp,DHX) using ETD of our TMD peptides in the gas phase after various periods of exchange (MS-ETD-DHX) (47, 72). To enhance fragmentation efficiency, we substituted the N-terminal SNK sequence of the C9926–55 TMD by KKK (75). The rate constants shown in Fig. 4 B reveal that DHX occurred within minutes for residues up to M35 within TMD-N and at the C-terminal KKK residues for all three peptides. Rate constants gradually decreased by up to two orders of magnitude in the region harboring the G37G38 motif. Compared to the WT, both G38 mutants perturbed exchange downstream of the mutation site in the region around the γ-40 cleavage site. Although the G38L mutation decreased kexp,DHX significantly between V39 and T43, G38P increased kexp,DHX, mainly for V39 and V40. Very slow exchange was observed in the TMD-C, containing the ε-cleavage sites, which was not affected by the G38 mutants. Additionally, we measured HDX by NMR spectroscopy. The shape of the NMR-HDX profile (Fig. 4 C) roughly matched the MS-ETD-DHX profile in that exchange within the TMD-N was faster than within the TMD-C (Fig. 4 B). NMR confirmed the locally reduced exchange rates for the G38L mutant and the locally enhanced rates for G38P, although the experimental errors prevented clear assignments of the differences to individual residues. As for MS-ETD-DHX, the G38 mutants did not affect the NMR-HDX in the vicinity of the ε-cleavage sites. The generally lower H/D rate constants, relative to the respective D/H values, are ascribed to the intrinsically slower chemical HDX as compared to DHX (75, 85).

DHX rate constants reconstructed from the fraction of open H-bonds and the local water concentration as calculated from the MD simulations could reproduce the overall MS-DHX kinetics well (0.400 ≤ χ2 ≤ 1.493, Fig. S5). In accordance with the ETD-derived rate profile, the calculated site-specific kDHX exchange rate constants (Fig. 4 D) revealed fast exchange at both termini and very slow exchange in the TMD-C. Additionally, the slow exchange at the ε-sites, without significant differences between WT and the G38 mutants, was confirmed. Taken together, for all peptides, local amide exchange rates determined by three different techniques consistently reported reduced H-bond strength in the helix-turn downstream to the G38 mutation site in the γ-cleavage site region compared to very strong H-bonds around the ε-sites.

To gain further insight into the distribution of backbone flexibility along the C9926–55 peptides, we focused on the site-specific population of α-H-bonds (NH(i)…O (i–4)) and 310-H-bonds (NH(i)…O (i–3)). The population of both H-bonds is of significant interest because switching between α- and 310-H-bonds allows for conformational flexibility of the TMD helix without inducing a permanent structural change (86). As such behavior was detected previously for C9928–55 (46, 48, 49) as well as for other TMDs (72, 86), we calculated both α- and 310-H-bond occupancies for each residue of C9926–55 in POPC and TFE/H2O, respectively, from the MD simulations (Fig. S6). In POPC, for the WT and G38L peptides, but not for G38P, a 10% lower occupancy of α-H-bonds emanating from backbone amides of V39 was largely compensated through the formation of 310-H-bonds (Fig. S6). In TFE/H2O, a larger-stretch of H-bonds spanning from the G33 carbonyl-oxygen to the amide-hydrogen at I41 was destabilized (Fig. S6). In this segment, for all peptides, a maximal drop in α-helicity by 40% was only partially compensated by the formation of 310-H-bonds, indicating enhanced conformational variability. Note that the HDX reflects the combined occupancies (Fig. 4, E and F), in which an amide is regarded as protected from exchange if either the α- or the 310-H-bond is formed. As shown in Fig. 4, E and F, intrahelical H-bonds were distorted only around the G37G38 sites, which correlated with the flexibility at the G37G38 hinge where H-bonds on the opposite face of the hinge have to stretch to allow for bending. This distortion around the G37G38 hinge for WT and the expected effects of the G38 mutations were consistent with the above-described DHX experiments (Fig. 4, B and C).

With regard to the cleavage domain, of all C9926–55 peptides both in POPC and TFE/H2O, we found a 5–10% population of 310-H-bonds around the amides of T43/V44 and T48/L49 as well as enhanced 310-H-bond propensity at the border to the C-terminal juxtamembrane residues (Fig. S6). However, neither shifting between α- and 310-H-bonds nor helix distortions involving the carbonyl-oxygen at the ε-sites or other signs of helix distortions could be detected for the G38 mutants (Fig. 4, E and F; Fig. S6). Remarkably, the occupancies of 310-H-bonds in the cleavage domain did not change when changing solvent from POPC to the hydrophilic environment in the TFE/H2O solution (Fig. S6). This demonstrates that the ε-sites are in a rather stable helical conformation, regardless of the solvent, that is not perturbed by the G38 mutations. In summary, the MD simulation findings and the H/D experiments indicate that alterations of the flexibility of the G37G38 hinge caused by the G38 mutations do not result in altered backbone dynamics at the ε-sites.

G38 mutants alter the spatial orientation of the ε-cleavage site region

In addition to local variations of the structure and stability of the C99 TMD, global orientation of the TMD helix in the bilayer may play an important role in substrate recognition and cleavage. TMD helices usually tilt to compensate hydrophobic mismatching between the length of the hydrophobic domain of the TMD and the hydrophobic thickness of the lipid bilayer (87, 88). Additionally, azimuthal rotations of the tilted helix around its axis are not randomly distributed but reflect preferential side-chain interactions with the individual components of the phospholipid bilayer (88, 89, 90). To explore a potential influence of the G38 mutations on these properties, we investigated the distribution of tilt (τ) and concomitant azimuthal rotation (ρ) angles (Fig. S7 A) of C9926–55 embedded in a POPC bilayer by ssNMR and MD simulations. The Cα-Hα order parameters of residues A30, L34, M35, V36, G37, A42, and V46 of C9926–55 (Table S1), chosen to represent the helical wheel with Cα-Hα bond vectors pointing in many different directions, were derived from DIPSHIFT experiments, which also confirmed the proper reconstitution of the peptides in the POPC bilayer (Fig. S8). To estimate τ and ρ of the TMD helix in C9926–55, a variant of the GALA model (68) was used (see Supporting Materials and Methods).

In Fig. 5 A, the normalized inverse of the root mean-square deviation (RMSDNorm) between data and model is shown as function of tilt and azimuthal rotation angles. For all three peptides, relatively broad τ,ρ landscapes with several possible orientations were found. Reliable helix orientations comprising helix tilt angles on the order of τ < 30° were found for all three peptides, although the G38P landscape deviated from the similar landscapes of WT and the G38L mutant. A tilt angle below 30° for the WT C99 TMD was also reported by others (91), although in the latter study a very heterogeneous picture with different orientation and dynamics of several helix parts was drawn. As shown in Fig. 5 B, the calculated probability distributions of (τ,ρ) combinations from MD simulations were in agreement with the ssNMR observations. Average tilt angles were also below 30° (WT: 23.1° with 95% CI (20.2, 26.2°), in agreement with previous results (43), G38L: 21.8° (18.7, 25.2°), and G38P: 25.9° (22.2, 29.9°)). A precise average ρ angle could not be calculated from the order parameters obtained from ssNMR nor obtained from the MD simulation but only a range of possible orientations, which is indicative of high TMD helix dynamics in liquid-crystalline membranes. In fact, all possible angles of ρ are observed in the MD simulations with considerable probability (Fig. 5 B). Consistent with only small mutation-induced variations in helix tilt and rotation angles, no significant differences of the mean residue insertion depths in the POPC bilayer were observed in the MD simulations, indicating quite similar vertical z-position of the cleavable bonds in the membrane for the WT and mutants (Fig. S9).

Figure 5.

G38 mutations of the C9926–55 peptide do not significantly alter its global membrane orientation but change the relative orientation of the ε-sites region. (A) Heat maps of tilt (τ) and azimuthal rotation (ρ) angle combinations of C9926–55 WT and G38L and G38P mutant peptides in a POPC bilayer are given as determined by ssNMR. The colors represent the RMSDNorm of the given (τ,ρ) pair. Maxima (dark areas) represent possible orientations. The circles represent the likeliest (red), second likeliest (blue), and third likeliest (green) solutions. (B) Probability distributions P (τ,ρ) of τ and ρ angle combinations of C9926–55 WT and G38L and G38P mutants in a POPC bilayer are shown, calculated from MD simulations. Dark areas represent high probabilities. (C) Probability distributions of bending (θ) and swivel (ϕ) angle combinations characterizing the orientation of ε-sites in C9926–55 WT and G38L and G38P mutants in POPC and in TFE/H2O are shown, calculated from MD simulations. (D and E) Representative conformations for WT and G38 mutants in (D) POPC and (E) TFE/H2O determined by K-means clustering of (θ,ϕ) combinations in cos-sin space are shown. Domains colored in red (domain A) represent the TMD-N segment I31-M35 and were also used to overlay the structures. Domains colored in blue (domain B) indicate the TMD-C segment I47-M51 carrying the ε-sites. The G37G38 hinge is colored in green. For the G38 mutants, the L and P residues are depicted in orange. Green spheres represent the Cα atom of G33 used as reference for the determination of swivel angles. (F) Distribution of conformations according to their bending angles θ are shown. The last class summarizes all conformations with θ > 80°.

Helices not only tilt and rotate in the membrane as a rigid body but are able to reorient intrahelical segments relative to each other, which in the case of the C99 TMD is enabled by the G37G38 hinge (46, 47, 48). We thus next sought to investigate the impact of the G38 mutations on the relative orientation of the helical turn carrying the ε-sites in the TMD-C to that of the TMD-N by analyzing the probability distributions of bending and swivel angles. The bending angle (θ) is defined as the angle between the axes through segment A (residues I31–M35) in the TMD-N and segment B (containing the ε-sites) in the TMD-C (residues I47–M51, Fig. S7 B). The swivel angle (ϕ) is defined by the horizontal rotation of domain B relative to the Cα atom of G33 as reference in domain A (Fig. S7 B). Positive ϕ-angles represent counterclockwise rotation. We analyzed the bend and swivel conformational sampling from the MD simulations for the C9926–55 WT and G38 mutant peptides in POPC and TFE/H2O (Table S2). In POPC, domain B of the WT and G38L peptides exhibited bending rarely exceeding 30° with a mean value of ∼12° (Fig. 5 C). For the G38P mutant, an increased population of conformations with θ even larger than 40°, lack of conformations with θ < 15°, and an average bending of ∼32° reveal a persistent reorientation of the ε-sites (Fig. 5 C, D, and F). The range of bending angles sampled around their average value was similar (±30°) for all peptides. Generally, we observed that C99 TMD bending is anisotropic. Notably, the horizontal rotation (i.e., swivel angle) of the ε-site orientation was sensitively influenced by the mutations with respect to both direction and extent of fluctuations (Fig. 5 C). Thus, both G38 mutations imparted a counterclockwise shift of the sampled swivel angles compared to WT. The average ϕ angle shifted by 10° for the G38L mutant and by 40° for the G38P mutant with respect to the WT (Table S2). Furthermore, compared to WT and G38L peptides, which sampled a swivel angle range of ±60°, the G38P mutation favored a much narrower range (±30°) (Fig. 5 C). Changing from the POPC membrane to TFE/H2O did not shift the preference of the peptides for the particular range of swivel angles (Fig. 5, C and E). However, in TFE/H2O, we generally noted an increase in the fraction of conformations with larger bending angles (Fig. 5 F). In the case of the G38P peptide, we even noticed excursions to a population with large bending angles θ > 80° (Fig. 5 F; Table S2).

The comparison of the bend and swivel behavior of ε-site orientations revealed that the preference for specific helix conformations depends on the mutation at G38. The G38P mutation alters both bend and swivel angles, i.e., vertical and horizontal position of the ε-cleavage site region with respect to TMD-N. In contrast, the G38L mutation mainly impacts the swivel angles and thus misdirects the ε-cleavage region horizontally. Taken together, we found that compared to the WT, the relative orientation of the domain containing the ε-sites is misdirected for both mutants. The latter could explain the reduced cleavage of both mutants by γ-secretase, as will be discussed below.

G38 mutations relocate hinge sites and alter extent of hinge bending and twisting

The results obtained so far revealed that the impact of the G37G38 hinge mutations on H-bond stability is confined to a small number of residues in the hinge region. Although H-bonding around the ε-sites was not altered, we noticed that sampling of ε-site orientations is distorted in the mutants. Because TMD helices generally bend and twist around various flexible sites, leading to changes in the helical pitch or the direction of the helix axis (92, 93, 94, 95), we next asked whether such helix motions could contribute to the relative orientation of the ε-cleavage site region. MD simulations allow for analyzing the fundamental types of helix motions, i.e., bending or twisting around a single hinge (referred to as types B and T) and combined bending and/or twisting around a pair of hinges (referred to as types BB, BT, TB, and TT) (48, 72). These six types of subdomain motions are exemplified in Fig. 6 A for C9926–55 WT.

Figure 6.

G38 mutations alter global bending and twisting motions. (A) The fundamental motions of helices exemplified for the C9926–55 WT peptide are shown. Motion types are bending (B) and twisting (T) coordinated by a single hinge, as well as combinations of bending and twisting (types BB, BT, TB, and TT) coordinated by a pair of hinges. Helical segments moving as quasi-rigid domains are colored in blue and red. Residues that act as flexible hinges are colored in green. Spheres represent Cα atoms of G37 and G38 and are colored according to the domain in which they are located. Screw axes passing the hinge regions are shown in gray. A screw axis perpendicular to the helix axis indicates a bending-like motion, whereas a screw axis parallel to the helix axis indicates a twisting-like motion. For mixed bending and twisting motions, a larger projection of the screw axis with respect to the helix axis indicates a higher percentage of twisting. (B) Probability of all six types of hinge bending and twisting motions in POPC and (C) TFE/H2O is shown. (D and E) Probability of each residue to act as a hinge site in the single-hinge (B + T) and double-hinge motions (BB + BT + TB + TT) for peptides in (D) POPC and (E) TFE/H2O is shown.

To understand the impact of the G38 mutations on the variability of the relative orientations of the ε-cleavage site region, we investigated the subdomain motions in WT and mutant peptides. Hinge sites are detected as flexible joints, coordinating the motions of quasi-rigid flanking segments (48, 72, 75, 96). The individual contribution of each type of subdomain motion to the overall dynamics is depicted in Fig. 6, B and C. More than 90% of the sampled conformations deviated from a straight helix. In the POPC bilayer, bending and twisting around a single hinge (types B + T) contributed ∼55% to overall backbone flexibility, and motions around a pair of hinges (types BB, BT, TB, and TT) contributed ∼35%. Note that the same residues are able to provide bending as well as twisting flexibility. The loss of packing constraints from lipids as well as enhanced H-bond flexibility in TFE/H2O (Fig. 4, E and F) correlated with favored helix bending (types B and BB) in WT and G38L. Remarkably, for G38P, both single bending (type B) as well as twisting (type T) around the G37G38 motif were enhanced at the expense of all other hinge motions. The marked helix bending indicates that the broader distributions of tilt and azimuthal rotation angles observed for G38P and the slightly narrower distributions for G38L compared to the WT, as found in the MD simulations and also experimentally by ssNMR (Fig. 5 A), might not only indicate differences between these mutants in their intrinsic membrane orientation but could also reflect the increased bending of G38P.

Because of their reduced H-bond stabilities, combined with extensive shifting between α- and 310-H-bonding (Fig. S6) and the absence of steric constraints, the V36GGV39 sites in the C99 TMD are optimally suited to act as hinges, an observation discussed already previously (40, 43, 45, 48, 49). Interestingly, a second hinge located in the TMD-C, upstream of the ε-sites appearing around residues T43VI45, was revealed (Fig. 6, D and E), consistent with previous results (48, 75). When acting in combination (motion types BB, BT, TB, and TT), both hinges coordinate bending/twisting of the flanks (domains A and B) with respect to the middle part of the helix (residues V36–V46). A change of local H-bond flexibility (Fig. S6) is able to alter the location of the flexible joints coordinating the motions of the flanking segments (Fig. 6, D and E) (72). In POPC, the hinge propensities of G38P, compared to WT and G38L, clearly shifted from G38 to G37 for all types of motions (Fig. 6 D). The shift of a hinge site by one residue correlates with the counterclockwise reorientation of the ε-sites, as also documented in Fig. 5 C, by a shift of the swivel angle distribution toward more positive values (also see Table S2). The most severe impact on single-hinge location was noticed for the G38L mutant in POPC. Restricted rotational freedom around L38 in the tightly packed lipid environment eliminates preference for single-hinge bending and twisting around the G37G38 hinge and enhances bending around the second T43VI45 hinge (Fig. 6 D). Most importantly, although WT and G38L peptides sample ε-site orientations characterized by similar bend and swivel angles (Fig. 5 C), the backbone conformations contributing to the orientation variability were different. In TFE/H2O, anisotropic bending over the G37G38 hinge was confirmed by the equal hinge propensity of these two residues in the WT peptide, whereas both mutants slightly preferred bending over G37 (Fig. 6 E).

In conclusion, the simulations show that the heterogeneous distribution of flexibility in the C99 TMD results from several residues coordinating bending and twisting motions. These hinge motions are favored by the absence of steric constraints as well as by flexible H-bonds shifting between i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 partners. Furthermore, the helix deformations associated with these motions and the location of the hinges are determined by sequence (WT versus G38L or G38P) as well as by packing constraints imposed by the environment (POPC membrane versus TFE/H2O). Thus, although the ε-sites reside in a stable helical domain, they possess mobility because of a variety of backbone motions enabled by two flexible regions acting as hinges, the V36GGV39 region and the T43VI45 region. The kind and relative contributions of these motions are distinctly altered by both G38 mutations, leading to a shift of the predominant relative spatial orientation of the ε-sites.

Discussion

To investigate the hypothesis that the flexibility of the TMD helix induced by the G37G38 hinge could possibly play an important role for the cleavage of the C99 γ-secretase substrate, the G38 hinge residue was mutated to leucine or proline. CD and solution NMR experiments, as well as MD simulations, confirmed our rationale that exchanging G38 with leucine leads to a globally more stable helix, whereas the G38P mutation reduces overall helicity. Unexpectedly, both mutants strongly reduced cleavage efficiency in the C99 γ-secretase cleavage assay. Moreover, the processivity of γ-secretase was also changed. These observations show that the G38 mutations have a dramatic impact on both the initial cleavage at the ε-site and the subsequent C-terminal trimming by γ-secretase.

One possibility to explain the impaired cleavage of the mutant substrates could be an altered encounter with γ-secretase due to changes of the global orientation of mutant C99 within the membrane. For instance, the different profile in mean-squared fluctuations, as well as the altered average bending angle for the G38P TMD, could alter the initial binding of this mutant with the enzyme. However, the ssNMR measurements and corresponding MD simulations revealed no significant differences of the tilt angles of the TMD of WT and the G38 mutants in a POPC bilayer. Additionally, MD simulations of the initial contact between the C9926–55 peptide and γ-secretase in a POPC bilayer did not disclose major differences between the G38 mutants and WT. Consistent with previous studies (27), the PS1 NTF subunit of γ-secretase was found as most prominent contact region. However, substrate contacts with the catalytic cleft of the γ-secretase complex were not observed in these simulations. It is likely that relaxations of the enzyme-substrate complex after binding as well as the substrate transfer to the active site take more time than the ∼370 μs total simulation time per peptide used in this analysis. Apparently, the differences between WT and mutant substrates become relevant at a stage beyond these initial contacts in the substrate recruitment process.

We also assessed whether modified backbone dynamics in the proximity of the ε-sites might explain the altered cleavability of the mutants. Backbone amide DHX experiments showed that, compared to the WT, the overall exchange kinetics was slower for G38L and somewhat faster for G38P. A more detailed residue-specific analysis revealed that effects only occurred near the G37G38 hinge, whereas residues around the ε-sites were not affected. Near these sites, MS-ETD-DHX, NMR-HDX, and MD simulations consistently reported low exchange rates and stable intrahelical H-bonds. Neither weaker H-bonds nor interchanging populations of α- and 310-H-bonds were observed at these sites. Although these results confirm previous studies (31, 46, 49), they seem to be in contrast with a recent study by Cao et al. (97), who calculated D/H fractionation factors from ratios of exchange rates to determine H-bond strengths in the cleavage domain of C99 in lysomyristoyl-phosphatidyl glycerol micelles. However, as explained elsewhere (75), H-bond strengths derived by the approach of Cao et al. (97) describe the preference for deuterium in an amide-to-solvent H-bond rather than the properties of the intrahelical amide-to-carbonyl H-bonds. Thus, altered backbone dynamics at the ε-sites cannot explain the reduced cleavage by γ-secretase of both the G38L and the G38P mutants. Apparently, breaking the H-bonds in the vicinity of the ε-sites might be the major hurdle for substrate cleavage that can be overcome only by interactions with the enzyme. Interestingly, also at the γ-cleavage sites of the C9926–55 peptide, DHX rates were decreased for the G38L mutation and slightly increased for G38P compared to the WT. However, these findings do not necessarily explain the altered processivity of the mutants because the backbone dynamics of the shortened C99 TMD is likely to change after the AICD has been cleaved off.

Advanced models for enzyme catalysis provide evidence that the intrinsic conformational dynamics of substrates and enzymes play a key role for recognition and catalytic steps (98, 99, 100, 101). Large-scale shape fluctuations might be selected to enable recognition, whereas lower-amplitude, more localized motions help to optimize and stabilize the enzyme-bound intermediate states (98, 99, 100, 101, 102). The chemical reaction is thought to be a rare, yet rapid, event (103) that occurs only after sufficient conformational sampling of the enzyme-substrate complex to generate a configuration that is conducive to the chemical reaction. For the complex between γ-secretase and the substrate, this sampling could be at the level of substrate transfer from exosites to the active site as well as at the level of substrate fitting into the active site. After the initial binding, a series of relaxations and mutual adaptation steps of the substrate’s TMD and the enzyme might be required before the scissile bond fits into the active site. In such a way, multiple conformational selection steps may play a decisive role in whether cleavage can take place (100). With regard to C99, the organization of rigidity and flexibility along the helix backbone rather than local flexibility at the ε-cleavage sites alone might be the essential property. Residues enjoying higher flexibility can act as hinges, coordinating the motions of more rigid flanking segments. These flexible hinges might provide the necessary bending and twisting flexibility for orienting the reaction partners properly. Our simulations and previously reported MD simulations reveal that the residues T43VI45 upstream of the ε-sites provide additional hinge flexibility that may be of importance for conformational adaptation of the TMD to interactions with the enzyme, where large-scale bending around the G37G38 hinge is obstructed (48, 75). In addition to bending around the G37G38 sites, twisting and more complex motions, including combinations of bending and twisting around the pair of hinges, can occur. The resulting distribution of conformations translates into a diversity of ε-site orientations. The perturbation of this distribution found in our MD simulations might provide plausible explanations of the reduced cleavability of both the G38L and the G38P mutant. Particularly, the counterclockwise shifts of the orientation of the ε-sites for both G38L and G38P mutants in POPC and the absence of small bending angles for G38P indicate that presentation of the scissile bond to the active site of presenilin can be misdirected for each mutant in its own way and differently compared to WT.

Notably, the TMD of Notch1 as well as the TMD of the insulin receptor, two other substrates of γ-secretase (16), have conformations very different from that of the C99 TMD as determined from solution NMR of single-span TM helices in membrane mimics (104, 105). In particular, Notch1 appears to be a straight helix, whereas the TMD helix of the insulin receptor is S-shaped, resembling the minor population of double-hinge conformations of the C99 TMD in a POPC bilayer found in our study. These observations seem to challenge the model assuming a central hinge as an integral step for the passage of the substrate toward the active site. Nevertheless, the conformational repertoire of the TMD of the substrates is determined by the α-helical folding, in which helices bend and twist around several sites. The relative importance of the individual conformations reflects sequence-specific differences in local flexibility. Functionally relevant conformational states are not necessarily among the highest-populated ones. Rather, conformations for which the protein has a low intrinsic propensity might be selected for productive interactions with the enzyme regulating or coordinating mechanistic stages preceding catalysis. These so-called “hidden,” “invisible,” or “dark” states are amenable by NMR or MD methods (102, 106, 107, 108). Thus, although missing a central flexible hinge, Notch1 and insulin receptor (and even other substrates of γ-secretase) might nevertheless provide the repertoire of functionally important motions necessary to adapt to interactions with the enzyme at different stages of the catalytic cycle. Furthermore, binding and conformational relaxation steps of different substrates might follow different pathways to optimize the catalytically competent state (99, 100).

Conclusions

Taken together, our study reveals that helix-flexibility-modulating G38L and G38P mutations have a severe impact on cleavage efficiency and processivity of the C99 substrate by γ-secretase. Notably, the G38 mutations do not have an impact on the H-bond stability around the ε-cleavage. We therefore conclude that necessary conformational relaxations required to facilitate the proteolytic event at the active site are not necessarily due to intrinsically enhanced flexibility of the C99 substrate around its ε-cleavage site but must be induced by interactions of the substrate with the enzyme. This interpretation of our data is in line with conclusions from recent vibrational spectroscopy and NMR studies of enzyme-substrate interactions of PSH, an archaeal homolog of presenilin. These studies provided evidence that PSH can induce local helical unwinding toward an extended β-strand geometry in the center of the TMD of the substrate Gurken (109), as well as in the ε-cleavage site region of a C99-TMD-derived substrate (110). Strong evidence for the local unfolding of the substrate TMD helix was also recently provided by cryogenic electron microscopy structural data for γ-secretase in complex with Notch1 or C83 (111, 112). For both substrates, unfolding at the ε-cleavage sites was induced and stabilized by the formation of a hybrid β-sheet composed of β-strands of PS1 and a β-strand comprising amino acids near the substrate’s TMD C-terminus. Our study suggests that, before the catalytic event, intrinsic conformational flexibility of the substrate in regions remote from the initial cleavage site is also necessary to prepare access to the active site and orient the reaction partners properly. Because conformational adaptability of the C99 substrate TMD is provided by flexible regions coordinating motions of helical segments, subtle changes of H-bond flexibility induced around the G37G38 hinge by the G38L and G38P mutations alter the local mechanical linkage to other parts of the helix. As a consequence, irrespective of whether the mutation at the G37G38 hinge is helix-stabilizing or helix-destabilizing, the orientation of the distal initial cleavage sites can be distorted in such a way that the probability of productive orientations with the active site of γ-secretase is decreased, thereby leading to impaired cleavage and altered processivity.

Author Contributions

D.H., B.L., D.L., C.S., C.M.-G., and H.S. conceived the study, designed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and supervised research. A.G. performed all-atom and S.M. coarse-grained MD simulations. F.K. performed CD spectroscopy. N.M. performed cleavage assays. P.H. performed HDX experiments, and M.S., H.H., A.V., and H.F. performed NMR spectroscopy. A.G., S.M., F.K., N.M., P.H., M.S., H.H., A.V., and H.F. analyzed and interpreted data. F.K. coordinated the drafting and writing of the manuscript. F.K., C.M.-G., A.G., C.S., and H.S. wrote the manuscript with contributions of all authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Zacharias for providing results of all-atom simulations of γ-secretase and Marius Lemberg for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR2290) (D.H., B.L., D.L., C.S., and H.S.) and in part by the VERUM Foundation (F.K.). The Gauss Centre for Supercomputing and the Leibniz Supercomputing Center provided computing resources through grants pr48ko and pr92so (C.S.).

Editor: Alan Grossfield.

Footnotes

Nadine Mylonas, Philipp Högel, and Mara Silber contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.04.030.

Contributor Information

Christina Scharnagl, Email: christina.scharnagl@tum.de.

Claudia Muhle-Goll, Email: claudia.muhle@kit.edu.

Harald Steiner, Email: harald.steiner@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Wolfe M.S. Intramembrane-cleaving proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:13969–13973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800039200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wolfe, M. S. 2009. Intramembrane-cleaving proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 284:13969-13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Sun L., Li X., Shi Y. Structural biology of intramembrane proteases: mechanistic insights from rhomboid and S2P to γ-secretase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016;37:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sun, L., X. Li, and Y. Shi. 2016. Structural biology of intramembrane proteases: mechanistic insights from rhomboid and S2P to γ-secretase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 37:97-107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Madala P.K., Tyndall J.D., Fairlie D.P. Update 1 of: proteases universally recognize β strands in their active sites. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:PR1–PR31. doi: 10.1021/cr900368a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Madala, P. K., J. D. Tyndall, …, D. P. Fairlie. 2010. Update 1 of: proteases universally recognize β strands in their active sites. Chem. Rev. 110:PR1-PR31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Timmer J.C., Zhu W., Salvesen G.S. Structural and kinetic determinants of protease substrates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Timmer, J. C., W. Zhu, …, G. S. Salvesen. 2009. Structural and kinetic determinants of protease substrates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:1101-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Belushkin A.A., Vinogradov D.V., Kazanov M.D. Sequence-derived structural features driving proteolytic processing. Proteomics. 2014;14:42–50. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Belushkin, A. A., D. V. Vinogradov, …, M. D. Kazanov. 2014. Sequence-derived structural features driving proteolytic processing. Proteomics. 14:42-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Robertson A.L., Headey S.J., Bottomley S.P. Protein unfolding is essential for cleavage within the α-helix of a model protein substrate by the serine protease, thrombin. Biochimie. 2016;122:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Robertson, A. L., S. J. Headey, …, S. P. Bottomley. 2016. Protein unfolding is essential for cleavage within the α-helix of a model protein substrate by the serine protease, thrombin. Biochimie. 122:227-234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Langosch D., Scharnagl C., Lemberg M.K. Understanding intramembrane proteolysis: from protein dynamics to reaction kinetics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015;40:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Langosch, D., C. Scharnagl, …, M. K. Lemberg. 2015. Understanding intramembrane proteolysis: from protein dynamics to reaction kinetics. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40:318-327. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Langosch D., Steiner H. Substrate processing in intramembrane proteolysis by γ-secretase - the role of protein dynamics. Biol. Chem. 2017;398:441–453. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2016-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Langosch, D., and H. Steiner. 2017. Substrate processing in intramembrane proteolysis by γ-secretase - the role of protein dynamics. Biol. Chem. 398:441-453. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lemberg M.K., Martoglio B. Requirements for signal peptide peptidase-catalyzed intramembrane proteolysis. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00655-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lemberg, M. K., and B. Martoglio. 2002. Requirements for signal peptide peptidase-catalyzed intramembrane proteolysis. Mol. Cell. 10:735-744. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Fluhrer R., Martin L., Haass C. The α-helical content of the transmembrane domain of the British dementia protein-2 (Bri2) determines its processing by signal peptide peptidase-like 2b (SPPL2b) J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:5156–5163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.328104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fluhrer, R., L. Martin, …, C. Haass. 2012. The α-helical content of the transmembrane domain of the British dementia protein-2 (Bri2) determines its processing by signal peptide peptidase-like 2b (SPPL2b). J. Biol. Chem. 287:5156-5163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Moin S.M., Urban S. Membrane immersion allows rhomboid proteases to achieve specificity by reading transmembrane segment dynamics. eLife. 2012;1:e00173. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Moin, S. M., and S. Urban. 2012. Membrane immersion allows rhomboid proteases to achieve specificity by reading transmembrane segment dynamics. eLife. 1:e00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ye J., Davé U.P., Brown M.S. Asparagine-proline sequence within membrane-spanning segment of SREBP triggers intramembrane cleavage by site-2 protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5123–5128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ye, J., U. P. Dave, …, M. S. Brown. 2000. Asparagine-proline sequence within membrane-spanning segment of SREBP triggers intramembrane cleavage by site-2 protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:5123-5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Linser R., Salvi N., Wagner G. The membrane anchor of the transcriptional activator SREBP is characterized by intrinsic conformational flexibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:12390–12395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513782112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Linser, R., N. Salvi, …, G. Wagner. 2015. The membrane anchor of the transcriptional activator SREBP is characterized by intrinsic conformational flexibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112:12390-12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.De Strooper B., Iwatsubo T., Wolfe M.S. Presenilins and γ-secretase: structure, function, and role in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006304. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; De Strooper, B., T. Iwatsubo, and M. S. Wolfe. 2012. Presenilins and γ-secretase: structure, function, and role in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a006304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Steiner H., Fukumori A., Okochi M. Making the final cut: pathogenic amyloid-β peptide generation by γ-secretase. Cell Stress. 2018;2:292–310. doi: 10.15698/cst2018.11.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Steiner, H., A. Fukumori, …, H. Okochi. 2018. Making the final cut: pathogenic amyloid-β peptide generation by γ-secretase. Cell Stress. 2:292-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Haapasalo A., Kovacs D.M. The many substrates of presenilin/γ-secretase. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:3–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Haapasalo, A., and D. M. Kovacs. 2011. The many substrates of presenilin/γ-secretase. J. Alzheimers Dis. 25:3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Jurisch-Yaksi N., Sannerud R., Annaert W. A fast growing spectrum of biological functions of γ-secretase in development and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:2815–2827. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jurisch-Yaksi, N., R. Sannerud, and W. Annaert. 2013. A fast growing spectrum of biological functions of γ-secretase in development and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1828:2815-2827. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Holtzman D.M., Morris J.C., Goate A.M. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:77sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Holtzman, D. M., J. C. Morris, and A. M. Goate. 2011. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci. Transl. Med. 3:77sr1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Selkoe D.J., Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Selkoe, D. J., and J. Hardy. 2016. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 8:595-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lichtenthaler S.F., Haass C., Steiner H. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis--lessons from amyloid precursor protein processing. J. Neurochem. 2011;117:779–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lichtenthaler, S. F., C. Haass, and H. Steiner. 2011. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis--lessons from amyloid precursor protein processing. J. Neurochem. 117:779-796. [DOI] [PubMed]