Abstract

Prostaglandins (PGs) are early and key contributors to chronic neurodegenerative diseases. As one important member of classical PGs, PGA1 has been reported to exert potential neuroprotective effects. However, the mechanisms remain unknown. To this end, we are prompted to investigate whether PGA1 is a useful neurological treatment for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or not. Using high-throughput sequencing, we found that PGA1 potentially regulates cholesterol metabolism and lipid transport. Interestingly, we further found that short-term administration of PGA1 decreased the levels of the monomeric and oligomeric β-amyloid protein (oAβ) in a cholesterol-dependent manner. In detail, PGA1 activated the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) and ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) signalling pathways, promoting the efflux of cholesterol and decreasing the intracellular cholesterol levels. Through PPARγ/ABCA1/cholesterol-dependent pathway, PGA1 decreased the expression of presenilin enhancer protein 2 (PEN-2), which is responsible for the production of Aβ. More importantly, long-term administration of PGA1 remarkably decreased the formation of Aβ monomers, oligomers, and fibrils. The actions of PGA1 on the production and deposition of Aβ ultimately improved the cognitive decline of the amyloid precursor protein/presenilin1 (APP/PS1) transgenic mice.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13311-018-00704-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Words: Prostaglandin A1, Alzheimer’s disease, cholesterol, ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1, presenilin enhancer protein 2

Introduction

As an inducible enzyme, activation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) results in the production of a series of biologically relevant prostaglandins (PGs): PGI2, PGF2α, PGD2, TXA2, PGE2, PGJ2, and PGA1 [1]. Each of these molecules participates in distinct functional pathways and has diverse physiological consequences, such as immuno- or vaso-modulatory effects, which are beneficial or deleterious to different organs, depending on the tissue substrate and clinical context [2]. Recently, increasingly targeted exploitation of downstream PGs signalling pathways was shown to be involved in the development and progression of AD [3]. For instance, PGI2 upregulates the expression of anterior pharynx-defective-1α and anterior pharynx-defective-1β (APH-1α/1β) in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin1 (APP/PS1) transgenic (Tg) mice [4]. PGE2 signalling suppresses beneficial functions of microglial cells in AD models [5]. Excitotoxicity-induced production of PGD2 resulted in sustaining microglial activation and delaying neuronal death [6]. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), a dehydration product of PGD2 is a potential target for halting inflammation-induced AD [7, 8]. However, a quite limited research has been reported describing the impact of PGA1 on AD. As one important member of classical CyPGs, PGA1 may exert neuroprotective effects by inhibiting NF-κB-mediated transcriptional activation [9], activating nuclear receptor PPARγ [10]. In addition, PGA1 profoundly changed the functions of cellular nucleophiles via Michael addition [11]. For instances, PGA1 has been postulated to attenuate rotenone-induced cytotoxicity in cultured SH-SY5Y cells [12] and upregulate the expression of neurotrophic factors in C6 glioma cells [13]. PGA1 also exerts protective effects on neurons against the stimulation of quinolinic acid or focal ischemia in vivo [14]. Because these effects are potentially neuroprotective, the therapeutic potential of PGA1 in neurodegenerative disorders, in which excitotoxicity may contribute to pathogenesis, has been evaluated using many models. However, further detailed studies have not yet been performed.

AD is an age-related disorder characterized by the deposition of β-amyloid protein (Aβ), the presence of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and degeneration of neurons in different brain regions, resulting in progressive cognitive dysfunction [15]. Various factors may be involved in the etiology, pathogenesis, and progression of AD [16]. Because this increasingly detailed understanding of AD pathogenesis has yet to lead to the development of an effective therapeutic intervention, novel approaches warrant urgent development and rigorous evaluation [17]. Refolo et al. revealed a correlation between hypercholesterolemia, an early risk factor for AD, with aberrant activation of β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing pathways and increased Aβ production [18]. Based on accumulating evidence, elevated cholesterol levels stimulated the activities of β- and γ-secretases, and a low cholesterol environment inhibits the production of Aβ [19]. In addition, a decreased incidence of AD is associated with the use of the cholesterol-lowering drugs, such as simvastatin (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor) [20]. Likewise, methyl-β-cyclodextrin, the cholesterol-extracting reagent strongly reduces intracellular and extracellular levels of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 peptides in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons and mixed cortical neurons [21]. Interestingly, high cholesterol diets have the ability to accelerate the deposition of Aβ even though cholesterol could not cross into the brain from the bloodstream in the brain of rabbits, guinea pigs, and rats [18]. To the reason, the effect of cholesterol on AD is recently found to be largely dependent on carriers and storage, such as apolipoprotein E (apoE), acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT), and ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) [22, 23]. In detail, ACAT has been regarded as a drug target of AD [24]. Overexpression of ABCA1 reduces the deposition of Aβ in the PDAPP mouse model of AD [25]. Deletion of ABCA1 increases the deposition of Aβ in the PDAPP mouse model of AD [26]. More directly, cholesterol is concentrated in the core of dendritic amyloid plaques (APs) [27]. All in all, cholesterol appears to play a key role in Aβ aggregation via its transport.

As the potential roles of cholesterol in the deposition of Aβ, the molecules involved in regulating the metabolism of cholesterol should be further identified. To this end, a few studies have revealed a connection between PGs and cholesterol [28]. For example, 15d-PGJ2/PPARγ/CD36 pathways participate in regulating the metabolism of cholesterol [29]. In addition, increased synthesis of PGs may also be involved in the niacin-induced activation of the PPARγ/liver X receptor alpha (LXRα)/ABCA1 pathway in adipocytes [30]. For ABCA1, it has the ability to modulate the cholesterol levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and influences the age at onset of AD [31]. Along these lines, the identification of a novel pathway that regulates ABCA1 expression may represent a new strategy for regulating Aβ levels. PGA1 acts as a potent and specific ligand/activator of PPARγ, and this pathway regulates lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Therefore, does cholesterol mediate the neuroprotective effect of PGA1?

Materials and Methods

Reagents

GW9662, a PPARγ antagonist, was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). DIDS, an ABCA1 inhibitor, was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). PGA1 and biotin-PGA1 (b-PGA1) were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Streptavidin-HRP (str-HRP) and Neutravidin-agarose were purchased from GenScript Biotech Corp. (Piscataway, NJ). Antibodies against β-actin, PPARγ, PEN-2, Aβ, NeuN, and GFAP, and Alexa Fluor 488-, Alexa Fluor 555-, and HRP-labelled secondary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signalling Technology (Danvers, MA). Iba-1 and p-PPARγ (Ser82) antibodies were purchased from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Hesse, Germany). The ABCA1 antibody was obtained from Abcam (Shanghai, China). Antibodies against α-cleavage of APP (sAPPα) and β-cleavage of APP (sAPPβ) were obtained from IBL International Corp. (Toronto, ON, Canada). We constructed retroviruses expressing specific guide RNAs (gRNAs) against mouse ABCA1 and PPARγ using vectors obtained from GENEWIZ, Inc. (Suzhou, Jiangsu, China). DAPI was obtained from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Haimen, Jiangsu, China), and the Aβ1-42 enzyme immunoassay kit was purchased from Life Technologies/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All reagents used for the quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and SDS-PAGE experiments were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA), and all other reagents were purchased from Life Technologies/Invitrogen, unless specified otherwise.

Tg Mice and Treatments

The male wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice or APP/PS1 Tg mice [B6C3-Tg (APPswe, PSEN1dE9) 85Dbo/J (#004462)] were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), as a model of AD. Genotyping was performed at 3 to 4 weeks after birth. Mice were housed in groups of five animals per cage in a controlled environment with a standard room temperature and relative humidity and a 12-h light–dark cycle, with free access to food and water. 6-month-old mice were treated with PGA1 (2.5 mg/kg/day) by an intranasal instillation for 6 months before Aβ was determined. The mean body weight of the mice was 20 g. Based on the results from studies showing that the degree of enhancement of learning ability by PGA1 is higher in aged rats than in young rats [32], 6-month-old mice were treated with PGA1 for 3 months before their cognitive abilities were assessed by the Morris water maze test or nest construction test. The general health and body weights of animals were monitored daily. Mice from the different groups were anesthetized, perfused with fixative, and brains were removed.

Whole-Transcriptome RNA Sequencing and Analysis

400 ng of RNA were utilized for library preparation by the NEBNext® rRNA Depletion Kit, NEBNext® Ultra II Directional RNA Kit and NEBNext® Multiplex Oligos for Illumina® (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The quality control of final reads with a size 350 bp was performed by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Then, the reads were sequenced on a sequencing platform based on HiSeq Xten illumina (Novogene Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). The resulting single-end RNA-seq reads were mapped to the mouse genome assembly. Genes with FDR < 0.05 and minimum log2 FC of ± 1 were used for downstream analysis. Enriched pathways identified in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) or gene ontology (GO) analysis are listed Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Morris Water Maze

The mice were trained and tested in a Morris water maze after a 3-month treatment with PGA1. Briefly, the mice were pretrained in a circular water maze with a visible platform for 2 days. The platform was then submerged inside the maze, with the deck located 0.5 cm below the surface of the water for the subsequent experiments. Milk was added to the water to hide the platform from sight. The mice were placed in the maze and allowed to swim freely until they located the hidden platform. The whole experiment lasted for 7 days. For the first 6 days, the mice were allowed to swim in the maze, with a maximum time of 60 s to find the platform. The learning sessions were repeated for 4 trials each day, with an interval of 1 h between each session. The spatial learning scores (the latency needed to locate and climb onto the hidden platform and the length of the path to the platform) were recorded. On the last day, the platform was removed, and the times that the mice passed through the memorized region were recorded for a period of 2 min (120 s). Finally, the recorded data were analyzed with a statistical program.

Nest Construction Test

The mice were housed in cages with corncob bedding for 1 week before the nest construction test [33]. Two hours before the onset of the dark phase of the light cycle, 8 pieces of paper (5 × 5 cm2) were introduced into the home cage to create conditions for nesting. The nests were scored on the following morning using a 4-point system: 1, no biting/tearing and random dispersion of the paper; 2, no biting/tearing of the paper, with paper gathered in a corner/side of the cage; 3, moderate biting/tearing of the paper, with gathering in a corner/side of the cage; and 4, extensive biting/tearing of the paper, with gathering in a corner/side of the cage [34].

CSF Collection

CSF was collected according to a published method [35]. Briefly, the mice were anesthetized and placed in prone position on the stereotaxic instrument (RWD Life Science Inc., San Diego, CA). A sagittal incision of the skin was made inferior to the occiput. Under a dissection microscope, the subcutaneous tissue and neck muscles were bluntly separated through the midline. A micro-retractor was used to hold the muscles apart. Next, the mouse was placed with the body at a 135° angle while the head was fixed. At this angle, the dura and spinal medulla were visible, with a characteristic glistening and clear appearance, and the circulatory pulsations of the medulla (i.e., a blood vessel) and adjacent CSF space were visible. The dura was then penetrated with a 6-cm glass capillary with a tapered tip and an outer diameter of 0.5 mm. After a noticeable change in resistance to capillary insertion, the CSF flowed into the capillary. The average volume of CSF obtained was 7 μL. All samples were stored in polypropylene tubes at − 80 °C.

Intracerebroventricular Injection

5 μL of vehicle (DMSO), PGA1 (1 μg/μL), cholesterol (1 mM), DIDS (1 mM), or GW9662 (40 μM) was injected (i.c.v.) into experimental mice [36]. Briefly, stereotaxic injections were performed at the following coordinates from the bregma: mediolateral, − 1.0 mm; anteroposterior, − 0.22 mm; and dorsoventral, − 2.8 mm. After the injection, each mouse recovered spontaneously on a heated pad. The reliability of the injection sites was validated by injecting trypan blue dye (Life Technologies/Invitrogen) in separate cohorts of mice and observing staining in the cerebral ventricles. 48 h after the injection, the mice were anesthetized, euthanized, and perfused.

Semi-denaturing Detergent Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

Semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE) was performed as previously described [37]. The gel containing a 1.5% agarose solution in 1× Tris-acetate buffer (TAE) and 0.1% SDS was prepared. The gel was subjected to electrophoresis at a low voltage (3 V/cm gel length) until the dye front reached ~ 1 cm from the end of the gel. The gel was then transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane for a minimum of 3 h. After transfer, the membrane was processed using standard Western blot techniques.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Aβ ELISA Kit

The mouse or human Aβ1-42 kit is a solid phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which was purchased from Life Technologies/Invitrogen. A monoclonal antibody against the NH2-terminus of human Aβ was used to coat the wells of the microtiter strips provided. During the first incubation, standards with a known human Aβ1-42 content, controls, and unknown samples were pipetted into the wells and co-incubated with a rabbit antibody against the COOH-terminus of the Aβ1-42 sequence. This COOH-terminal sequence is created upon cleavage of the analyzed precursor. After washes, the bound rabbit antibody was detected by the addition of a horseradish peroxidase-labelled anti-rabbit antibody. After a second incubation and washing step to remove all unbound enzyme, a substrate solution was added, which is acted upon by the bound enzyme to produce a colored product. The intensity of this colored product is directly proportional to the concentration of human Aβ1-42 present in the original specimen.

Cholesterol ELISA Kit

The cholesterol quantitation kit from Sigma-Aldrich was used to determine the concentrations of free cholesterol, cholesteryl esters, or both (total). In this kit, the total cholesterol concentration was determined by a coupled enzyme assay, which results in a colorimetric (570 nm)/fluorometric product that is proportional to the concentration of cholesterol present in the sample.

Cell Culture

Mouse neuroblastoma N2a cells and N2a cells stably expressing human APP carrying the K670N/M671L Swedish mutation (APPsw cell) were grown (37 °C and 5% CO2) on 6 cm tissue culture dishes (1 × 106 cells per dish) in an appropriate medium. In a separate set of experiments, cells were grown in serum-free medium for an additional 12 h before incubation with inhibitors in the absence or presence of PGA1.

Cell Fractionation

APPsw cells were treated with vehicle or PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. Nuclear and cytosol were separated according to previously described methods [38]. Protein content was determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific-Pierce, Rockford, IL) for cytosolic extracts and the Bradford method for nuclear extracts. Aliquots from the fraction of nuclear or cytosolic extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, which were further probed with antibody against c-Jun and RhoGDI as a marker of nuclear and cytosol, respectively.

Pull-Down Assay

Cytosolic fractions from APPsw cells treated with vehicle or b-PGA1 were purified on Neutravidin-agarose [11]. Briefly, cytosolic fractions containing 100 μg of protein were adsorbed onto Neutravidin-agarose in the presence of 1% NP-40 and 0.1% SDS by batch-wise incubations for 1 h at 4 °C in a rotary shaker. Unbound proteins were removed by extensive washes with 0.1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1% NP-40, and 0.1% SDS. Then, biotinylated proteins bound to Neutravidin-agarose were boiled for 10 min. The supernatant was used for Western blot analysis.

qRT-PCR

qRT-PCR assays were performed with the MiniOpticon Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using total RNA and the GoTaq One-step Real-Time PCR kit with SYBR green (Promega, Madison, WI). Forward and reverse primers for mouse ABCA1 were 5′-CATAGACCCAGAATCCAGGGAGAC-3′ and 5′-GCAGGACAATCTGAGCAAAGAAAC-3′, respectively. The gene expression levels were normalized to GAPDH, whose forward and reverse primers were 5′-GCTCATGACCACAGTCCATGCCAT-3′ and 5′-TACTTGGCAGGTTTCTCCAGGCGG-3′, respectively.

Western Blot Analysis

Tissues or cells were lysed with RIPA buffer [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS, containing protease inhibitors and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail] (Thermo Scientific-Pierce). The protein concentrations in the cell lysates were determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific-Pierce). The total cell lysates (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a membrane, and probed with a panel of specific antibodies. Each membrane was probed with only one antibody and β-actin served as a loading control.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse brains were collected from WT or vehicle-/PGA1-treated APP/PS1 Tg mice, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were cut at a 5 μm thickness and mounted on Superfrost plus slides (VWR Scientific, West Chester, PA). Sections were dewaxed with a xylene solution, rehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions, submerged in 3% hydrogen peroxide to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity, and subjected to antigen retrieval in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave oven at 450 W for 15 min. Sections were then incubated with UV block (Thermo Scientific-Pierce) containing 10% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min and then incubated with the primary antibody diluted in PBS containing 4% BSA (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) overnight in a humid chamber at 4 °C. A mouse monoclonal anti-ABCA1 antibody (1:100, 1 μg/μL) and rabbit monoclonal anti-PEN-2 antibody (1:200, 1 μg/μL) were used as the primary antibodies. On the next day, sections were incubated with a biotin-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, followed by streptavidin-HRP for 30 min. Then, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin 30 s and differentiated with a hydrochloric acid/alcohol mixture. Finally, after the DAB stain was applied for 1 min, sections were washed with water for 30 min. Images of immunohistochemical staining were captured with a Leica camera and microscope.

Immunofluorescence

APPsw cells were cultivated on coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) in Cell Bind 6-well plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY). After treatment with the vehicle or PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with ice-cold methanol, and rehydrated with PBS. A blocking step was performed with a blocking solution containing 2% BSA and 4% goat serum from Sigma-Aldrich. A mouse monoclonal antibody against ABCA1 (1:100, 1 μg/μL) or rabbit monoclonal antibody against PEN-2 (1:200, 1 μg/μL) was added to cells and incubated overnight at 4 °C. On the following day, cells used for double labelling were washed with PBS-T (0.03% Tween-20). And then, cells were incubated with species-specific secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG) at a final dilution of 1:500 for 1 h at room temperature, followed by washed extensively with PBS. Finally, the cells were counterstained with DAPI and mounted with fluorescent mounting medium (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA). Confocal scanning and immunofluorescence microscopy were used to analyze the subcellular localization of ABCA1 or PEN-2 in APPsw cells.

Luciferase Reporter Assays

A dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega) was used to measure the regulatory effects of PGA1 on the activity of PPARγ promoter. In addition, the above method was also used to determine the effect of PPARγ depletion on the activity of ABCA1 promoter in PGA1-stimulated cells. Firefly/Renilla luciferase activities were measured with a Spark 10 M luminometer (TECAN, Mannedorf, Switzerland) [39].

PPARγ Promoter Reporter Assay

APPsw cells were plated in triplicate wells of a 24-well plate. When the confluence reached 80%, cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of pGL4.27-PPARγ promoter or pGL4.27 firefly luciferase promoter reporter plasmids (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) using Lipofectamine 2000. Additionally, cells were transfected with 10 ng of pRL-CMV (Promega), which encodes Renilla luciferase and was used for subsequent normalization of the cell number. The media were replaced with fresh media supplemented with vehicle or PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM after 6 h, and the ratio of firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were calculated at 48 h.

ABCA1 Promoter Reporter Assay

APPsw cells stably expressing gRNA-PPARγ were used for this experiment. The promoter was then analyzed using a ~ 1-kilobase fragment (from − 847 to + 244 bp) of the mouse ABCA1 promoter that was linked to the firefly luciferase reporter gene [40]. The experimental procedure was the same as described above for analyzing the promoter activity of the PPARγ, except for the pGL4.27-ABCA1 promoter plasmid.

Construction and Stereotaxic Injection of Engineered Retroviruses

Sequences encoding short gRNAs were constructed in the lentiCRISPR v2-Blast vector under the control of the human EF-1α promoter (Addgene, Cambridge, MA), which were then transfected into cells. Cells were grown for 5 days before plating to produce single colonies. Multiple candidate clones were picked and tested for gene disruption by Western blot. Three gRNAs against mouse ABCA1 and PPARγ were used. The sequences of the gRNA producing the optimal effects among the three candidates were 5′-TGATCTGCCGTAACATTCTC-3′ (gRNA-ABCA1) and 5′-AGTGGTCTTCCATCACGGAG-3′ (gRNA-PPARγ). Retroviral vectors were cotransfected with the lentivirus packaging vectors pLP-VSVG, pRSV-Rev and pMDLg pRRE into HEK293T cells to validate the specificity and efficiency of the gRNAs in vitro. The collected virus was used for cell transfection or stereotaxic injection.

Animal Committee

All animals were handled according to the guidelines for the care and use of medical laboratory animals (Ministry of Health, Peoples Republic of China, 1998) and the guidelines of the laboratory animal ethical standards of Northeastern University and China Medical University.

Human Brain Samples

Human brain samples were obtained from the New York Brain Bank (Columbia University, New York, NY): serial numbers P535-00 (normal), T4308 (middle stage of AD, an 86-year-old man with moderate AD), and T4304 (late stage of AD, an 84-year-old woman with severe and end-stage AD).

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the means ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. The statistical significance of the differences between the means was determined using Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance, where appropriate. If the means were significantly different, multiple pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s post hoc test.

Results

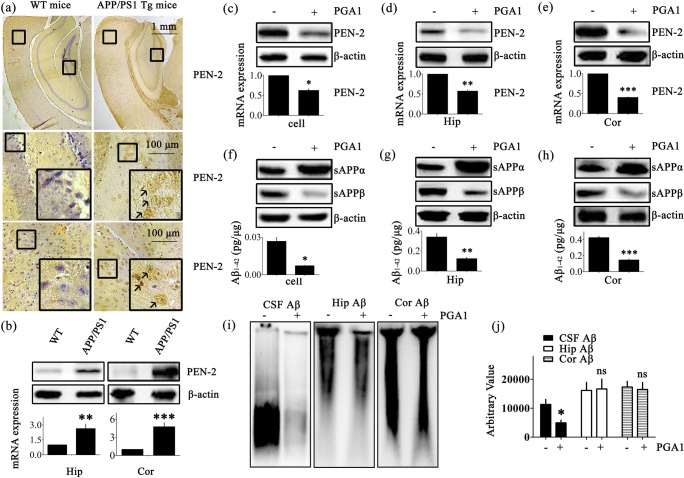

PGA1 Decreases Aβ Production

According to diverse lines of evidence, Aβ protein has a causal role in AD pathogenesis [41]. As shown in Fig. S1, a dense mass of β-amyloid plaques (APs) was deposited in the brains of AD patients and APP/PS1 Tg mice with different degrees of senile dementia. As senile dementia was aggravated, the number of APs was noticeably increased. Based on studies that have suggested essential roles for PEN-2 in catalyzing the intramembrane cleavage of integral membrane proteins such as APP, we evaluated the levels of PEN-2 in the brains of 3-month-old APP/PS1 Tg mice. PEN-2 was mainly expressed in the cerebral cortex (Cor) and at lower levels in the hippocampus (Hip). The expression of PEN-2 was substantially upregulated in the APP/PS1 Tg mice compared to the WT mice (Fig. 1a). To further confirm this finding, we examined the levels of the PEN-2 mRNA and protein in the APP/PS1 Tg mice. Consistent with the immunostaining data, the levels of the PEN-2 mRNA and protein were upregulated in both the Hip and Cor of the APP/PS1 Tg mice (Fig. 1b). These observations further reinforced the potential involvement of PEN-2 in AD.

Fig. 1.

PGA1 decreased Aβ production. (a, b) The brains of 3-month-old WT or APP/PS1 Tg mice were collected after the mice had been anesthetized and perfused. (c–j) For PGA1 treatment, APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. In the APP/PS1 Tg mice, 5 μL of PGA1 was injected (i.c.v.) to the cerebral ventricles at a concentration of 1 μg/μL for 48 h. (a) PEN-2 immunoreactivity was determined by IHC with an anti-PEN-2 antibody. The arrows indicated positive staining for PEN-2. (b–e) The level of the PEN-2 protein was determined using Western blot analysis and β-actin served as the internal control (upper panel). PEN-2 mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR, with the total amount of GAPDH serving as the internal control (lower panel). (f–h) Levels of the sAPPα and sAPPβ were determined by Western blot analysis and β-actin served as the internal control (upper panel). The production of Aβ1-42 was analyzed by ELISA (lower panel). (i) The aggregated forms of Aβ in the CSF, Hip, or Cor of APP/PS1 Tg mice were analyzed by SDD-AGE. (j) The relative intensity of SDD-AGE bands was calculated by the Image J software. The data represent means ± S.E. of 6 independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to WT, vehicle-treated APPsw cells, or APP/PS1 Tg mice

Although research on the role of PGA1 in neurodegenerative diseases is still lacking, a study has convinced the neuroprotective effects of PGA1 on neurons [42]. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of PGA1 on the production of Aβ by activating γ-secretase. As shown in Fig. 1c–e, the increased levels of the PEN-2 mRNA and protein were significantly decreased in APPsw cells pretreated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM and APP/PS1 Tg mice injected (i.c.v.) with PGA1 (5 μL, 1 μg/μL). In addition, the extent of sAPPα was markedly increased, but sAPPβ showed the opposite trend (Fig. 1f–h). As a consequence, Aβ1-42 levels were obviously decreased in PGA1-treated subjects. As shown in Fig. 1i, j, the injection (i.c.v.) of PGA1 significantly reduced the CSF levels of low molecular weight Aβ oligomers. However, short-term administration of PGA1 did not affect the levels of high molecular weight Aβ aggregates or fibrils in the Hip and Cor of 9-month-old APP/PS1 Tg mice.

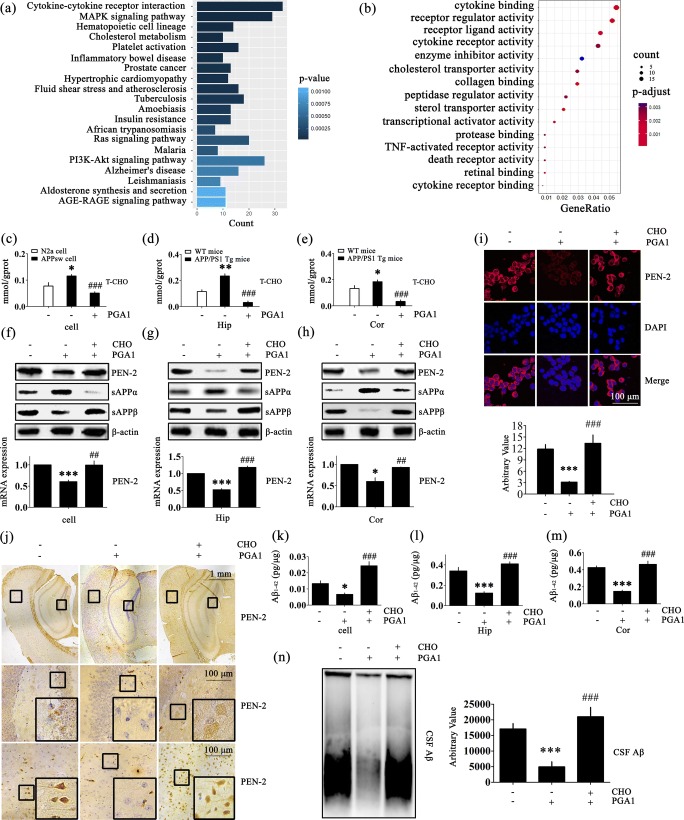

Cholesterol Mediates the Effects of PGA1 on Decreasing the Production and Deposition of Aβ

We conducted high-throughput sequencing experiments to determine which pathways played key roles in the mechanism by which PGA1 regulated the production and deposition of Aβ. As a consequence, we identified 360 upregulated and 346 downregulated genes that were differentially expressed (log2 fold change of ± 1 (log2 FC (± 1)); false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) in response to PGA1 (Tables S1 and S2). The subsequent functional annotation analysis performed by clusterProfiler to determine important biological processes (GO) and cellular pathways (KEGG) revealed that the differentially expressed genes were associated with regulating cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, MAPK signalling pathway, hematopoietic cell lineage, cholesterol metabolism and lipid transport, etc. Among these mechanisms, PGA1 had not been previously reported to be involved in cholesterol metabolism and lipid transport (Fig. 2a, b). To this end, we continue to investigate the roles of PGA1 in regulating the development and progression of AD via modulating the cholesterol metabolism and lipid transport.

Fig. 2.

Cholesterol mediates the effects of PGA1 on decreasing the production and deposition of Aβ. (a, b) APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h, and total RNA was isolated for RNA sequencing. The differentially expressed genes were analyzed by functional annotation clustering. (c–e) For PGA1 treatment, APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. In the APP/PS1 Tg mice, 5 μL of PGA1 was injected (i.c.v.) to the cerebral ventricles at a concentration of 1 μg/μL for 48 h. (f–n) APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM in the absence or presence of cholesterol in a final concentration of 100 μM for 48 h. In the APP/PS1 Tg mice, 5 μL of PGA1 was injected (i.c.v.) to the cerebral ventricles at a concentration of 1 μg/μL in the absence or presence of cholesterol (5 μL, 1 mM) for 48 h. Using ClusterProfiler, the top 20 biological processes were identified by KEGG pathway analysis (a), and the top 15 biological processes were identified by GO pathway analysis (b) by measuring two indicators of their associated counts and P values. (c–e) Intracellular cholesterol levels were analyzed by ELISA. (f–h) The protein levels of PEN-2, sAPPα and sAPPβ were determined using Western blot analysis, and β-actin served as the internal control (upper panel). PEN-2 mRNA levels were determined using qRT-PCR, with the total amount of GAPDH serving as the internal control (lower panel). (i) Immunofluorescence was determined, with a primary rabbit anti-PEN-2 antibody and Alexa Fluor 555-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG as the secondary antibody (upper panel). The relative intensity of immunofluorescence was calculated by Image J software (lower panel). (j) IHC was determined with an anti-PEN-2 antibody. (k–m) The production of Aβ1-42 was analyzed by ELISA. (n) SDD-AGE of Aβ in CSF of APP/PS1 Tg mice was performed. The relative intensity of SDD-AGE bands was calculated by the Image J software. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01,***p < 0.001 compared to N2a cells, WT mice, vehicle-treated APPsw cells, or APP/PS1 Tg mice. ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 compared to APPsw cells, vehicle-treated APP/PS1 Tg mice, PGA1-treated APPsw cells, or APP/PS1 Tg mice

As cholesterol has been widely reported to exhibit a close association with AD [43], we firstly confirmed that the levels of cholesterol are elevated in AD models (Fig. 2c–e). More interestingly, cholesterol levels were substantially reduced in PGA1 treatment groups compared to the untreated group (Fig. 2c–e). To further explore whether cholesterol mediates the downregulation of Aβ by PGA1, experimental groups were pre-administered excess cholesterol. The cholesterol pretreatment of APPsw cells or injection (i.c.v.) of cholesterol into 9-month-old APP/PS1 Tg mice thoroughly restored the inhibitory effect of PGA1 on downregulating the expression of the PEN-2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 2f–h). Cells were also stained with a PEN-2-specific antibody following treatment with or without cholesterol to validate the results from the Western blot and qRT-PCR analysis. As expected, the PGA1 treatment clearly suppressed the immunofluorescence staining for PEN-2 in the APPsw cells, but the pretreatment with cholesterol produced similar fluorescence intensity to the control group (Fig. 2i). Subsequent immunohistochemical staining for PEN-2 yielded an extremely weak positive reaction in PGA1-treated group, whereas an overdose of cholesterol hindered this process (Figs. 2j and S2a). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 2f–h, excess cholesterol completely reversed the trends in sAPPα and sAPPβ levels induced by PGA1. Therefore, cholesterol pretreatment thoroughly restored the CSF levels of Aβ1-42 and low molecular weight Aβ oligomers in PGA1-trated mice (Fig. 2k–n). Taken together, our results reveal a pivotal role for cholesterol in blocking the effects of PGA1 on suppressing the production of Aβ.

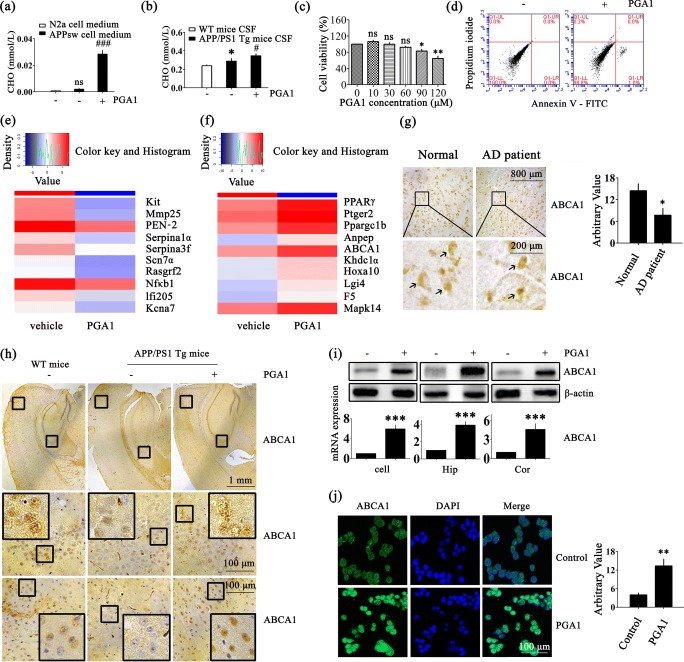

PGA1 Upregulated the Expression of ABCA1

As shown in Fig. 3a, b, addition of PGA1 induced a marked accumulation of cholesterol in the supernatant of APPsw cells and CSF of APP/PS1 Tg mice. Because a few studies had reported that PGA1 was cytotoxic and the cells released cholesterol depending on the growth state of cells, we characterized whether the PGA1 induction of cholesterol efflux was relevant to its cytotoxicity [44], we characterized whether cholesterol efflux induced by the PGA1 treatment was relevant to its cytotoxicity. Based on the results from the cytotoxicity assays, significant cytotoxicity was not observed when cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM (Fig. 3c). An analysis of the flow cytometry data did not reveal obvious apoptosis (Fig. 3d). Moreover, compared to untreated cells, the heat map summarizes the hierarchical clustering of the top 10 differentially downregulated and upregulated RNAs (log2 FC (± 1); FDR < 0.05). Interestingly, the lipid transport-related gene PPARγ and ABCA1 were identified to be regulated by PGA1 treatment (Figs. 3e, f and S2b). Therefore, PGA1-induced cholesterol efflux was not due to cytotoxicity, but rather by a transporter that was potentially related to transmembrane lipid transport. As expected, we observed a slight decrease in ABCA1 levels in patients and mouse models of AD compared to age-matched normal controls, suggesting that this change might be responsible for the disturbance of cholesterol homeostasis in AD models (Fig. 3g, h). As shown in Fig. 3i, PGA1 significantly increased the mRNA and protein levels of the ABCA1 in APPsw cells and APP/PS1 Tg mice. Further experiments verified the accuracy of this result using anti-ABCA1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunocytochemistry (Figs. 3h, j and S2c). Based on these results, ABCA1 might play a critical role in the mechanism by which PGA1 regulates cholesterol and Aβ levels.

Fig. 3.

PGA1 upregulated the expression of ABCA1. (a, b, d, h–j) APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. In the APP/PS1 Tg mice, 5 μL of PGA1 was injected (i.c.v.) to the cerebral ventricles at a concentration of 1 μg/μL for 48 h. (c) APPsw cells were treated with different concentrations of PGA1. (e, f) APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h, and total RNA was isolated for RNA sequencing. (g) Tissue blocks of human brains with AD were collected by the New York Brain Bank. Free-floating slices (40 μm) were prepared using a cryostat. (a) The levels of extracellular cholesterol in the conditional medium were analyzed by ELISA. (b) Cholesterol levels in CSF were analyzed by ELISA. (c) Cell viability was determined by the cytotoxicity assays. (d) The apoptosis of the cells was determined by Annexin V/PI staining and detected by flow cytometry. (e) Top 10 downregulated genes (log2 FC (− 1); FDR < 0.05) and (f) top 10 upregulated genes (log2 FC (+ 1); FDR < 0.05) are shown in the heat map. (g) The immunoreactivity of ABCA1 was determined by IHC in tissue blocks of brains from AD patients compared to normal controls. The arrows indicated positive staining for ABCA1 (left). The relative intensity of IHC was calculated by the Image J software (right). (h) IHC for ABCA1 was determined using a primary mouse anti-ABCA1 antibody. (i) The protein levels of ABCA1 were determined using Western blot analysis, and β-actin served as the internal control (upper panel). ABCA1 mRNA levels were determined using qRT-PCR, with the total amount of GAPDH serving as the internal control (lower panel). (j) Immunofluorescence staining was performed to determine the expression of ABCA1, with a primary mouse anti-ABCA1 antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG as the secondary antibody (left). The relative intensity of immunofluorescence was calculated by the Image J software (right). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to conditional medium of N2a cells, the CSF of WT mice, normal brain of humans, vehicle-treated APPsw cells, or APP/PS1 Tg mice. #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 compared to conditional medium of vehicle-treated APPsw cells or the CSF of APP/PS1 Tg mice

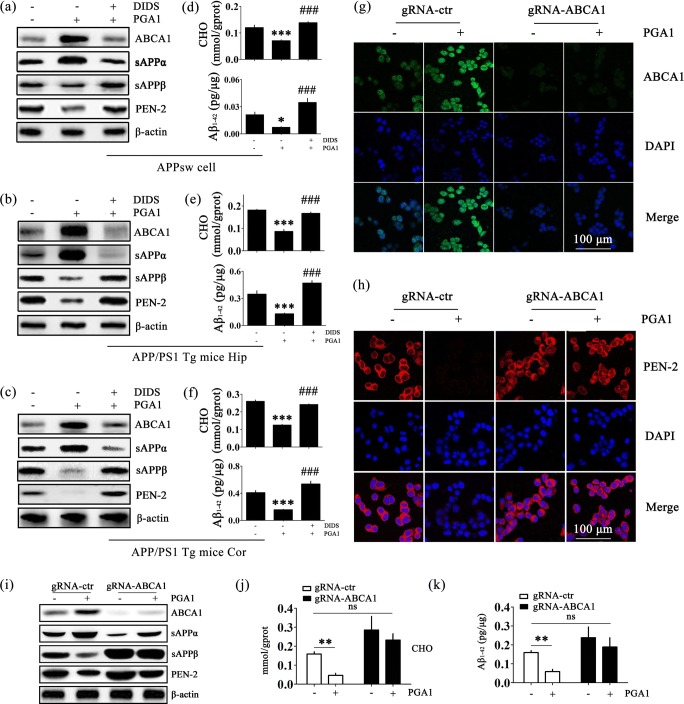

The ABCA1/CHO Signalling Pathway Mediates the Suppressive Effects of PGA1 on the Production of Aβ1-42

Using double staining and confocal microscopy, positive ABCA1 staining was predominantly observed in neurons and microglial cells (Fig. S3a, b), and positive PEN-2 staining was predominantly observed in neurons (Fig. S3c, d). Consistent with these observations, ABCA1 was enriched in neurons and microglial cells, and comparatively weaker expression was observed in astrocytes [45, 46]. PEN-2 was enriched in neurons, but was very weakly expressed in microglial cells and astrocytes [47]. By these observations, we sought to elucidate the signalling pathways of ABCA1 regulation in PGA1-treated APPsw cells. For an in-depth analysis of the signalling pathways through which PGA1 regulates ABCA1 expression and cholesterol efflux, we treated AD models with PGA1 in the absence or presence of DIDS, a specific ABCA1 inhibitor. Treatment of APPsw cells and APP/PS1 Tg mice with DIDS reversed the effects of PGA1 on increasing the synthesis of ABCA1 (Figs. 4a–c and S4a–c). Meanwhile, DIDS reversed the effects of PGA1 on inducing cholesterol efflux to a large extent (Fig. 4d–f, upper panels). Next, we evaluated the effect of DIDS on the expression of PEN-2 in PGA1-treated cells or mice. As expected, the blockade of ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux completely abolished the effects of PGA1 on suppressing the expression of PEN-2 (Figs. 4a–c and S4d–f). Therefore, DIDS blocked the effects of PGA1 on decreasing the production of Aβ1-42 (Fig. 4d–f, lower panels).

Fig. 4.

The signalling pathway of ABCA1/CHO mediates the suppressive effects of PGA1 on the production of Aβ1-42. (a–f) APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM in the absence or presence of DIDS in a final concentration of 100 μM for 48 h. In the APP/PS1 Tg mice, 5 μL of PGA1 was injected (i.c.v.) to the cerebral ventricles at a concentration of 1 μg/μL in the absence or presence of DIDS (5 μL, 1 mM) for 48 h. (g–k) gRNA-ABCA1 or gRNA-control transfected APPsw cells were treated with or without PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. (a–c, i) The protein levels of ABCA1, sAPPα, sAPPβ, and PEN-2 were determined using Western blot analysis and β-actin served as the internal control. (d–f) Intracellular cholesterol (upper panel) and Aβ1-42 (lower panel) were determined by ELISA. (g, h) Immunofluorescence staining was performed to determine the expression of ABCA1 or PEN2, using IHC with a primary mouse anti-ABCA1 or rabbit anti-PEN2 antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 555-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG as the secondary antibody. Intracellular cholesterol (j) or Aβ1-42 (k) levels were determined by ELISA. The data represent means ± S.E. of 6 independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to vehicle-treated APPsw cells or APP/PS1 Tg mice or vehicle-treated gRNA-control transfected APPsw cells. ###p < 0.001 compared to PGA1-treated APPsw cells or APP/PS1 Tg mice

To eliminate any potential nonspecific effects of DIDS as the pharmacological inhibitor, experiments were performed by transfecting APPsw cells with a gRNA oligonucleotide sequence specific targeted ABCA1. ABCA1 knockout cells exhibited low levels of ABCA1 even stimulating with PGA1 (Figs. 4g, i and S4g). Similarly, ABCA1 knockout completely reversed the effects of PGA1 on downregulating the expression of PEN-2 (Figs. 4h, i and S4h). Consistent with these observations, ABCA1 knockout also abolished the effects of PGA1 on inducing cholesterol efflux (Fig. 4j) and decreasing the levels of Aβ1-42 (Fig. 4k). Therefore, ABCA1 mediated the effects of PGA1 on suppressing the levels of Aβ1-42.

The Signalling Pathway of PPARγ/ABCA1/CHO Mediates the Effects of PGA1 on Decreasing the Levels of Aβ1-42

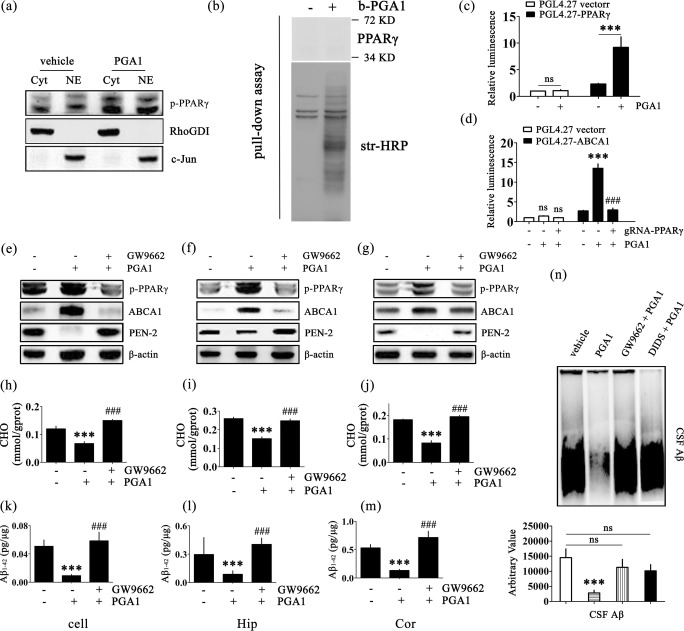

The results of multipathway luciferase reporter arrays in human HEK293T cells strongly confirmed that PGA1 increased the expression of PPARγ; we therefore evaluated whether the PPARγ pathway mediates the regulatory effects of PGA1 on ABCA1 expression or not (Fig. S5a). To this purpose, we firstly explored the regulatory effects of PGA1 on PPARγ activation in the nucleus and cytoplasm. The results showed that PPARγ was significantly activated in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 5a). Because PGA1 is reported to activate PPARγ through multiple pathways, we examined the two most important regulatory approaches, Michael addition and transcriptional control [48, 49]. Based on the results from the pull-down assay, PGA1 did not regulate PPARγ activation by Michael addition (Fig. 5b). We designed two pGL4.27 promoter/luciferase reporter assays to further confirm the relationships between PPARγ and ABCA1 in the mechanism by which PGA1 regulates Aβ levels. As shown in Fig. 5c, PGA1 treatment clearly increased the activity of PPARγ promoter. Therefore, PGA1 regulated the phosphorylation of PPARγ through a transcription-dependent mechanism. However, PGA1 no longer increased the activity of ABCA1 promoter in the presence of gRNA-PPARγ (Fig. 5d). Clearly, PPARγ was indispensable for the pathway by which PGA1 regulated ABCA1 expression.

Fig. 5.

The signalling pathway of PPARγ/ABCA1/CHO mediates the effects of PGA1 on decreasing the levels of Aβ1-42. (a) Nuclear (NE) and cytosolic (Cyt) fractions were obtained from APPsw cells treated with or without PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. Western blot for p-PPARγ were analyzed with an anti-p-PPARγ antibody. RhoGDI served as cytosolic marker, and c-Jun served as nuclear marker. (b) APPsw cells treated with or without b-PGA (60 μM, 2 h) were used for the pull-down assay. Western blot for PPARγ were analyzed with an anti-PPARγ antibody. Total biotinylated proteins were analyzed with str-HRP. (c) Cells transfected with the pGL4.27 vector or pGL4.27-PPARγ were treated with or without PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. (d) Cell transfected with the pGL4.27 vector or pGL4.27-ABCA1 were treated with or without PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM in the absence or presence of gRNA-PPARγ for 48 h. The relative luminescence (firefly/Renilla) was calculated and normalized to the control reporter in the cells. (e–n) APPsw cells were treated with PGA1 in a final concentration of 10 μM in the absence or presence of GW9662 in a final concentration of 1 μM for 48 h. In the APP/PS1 Tg mice, 5 μL of PGA1 was injected (i.c.v.) to the cerebral ventricles at a concentration of 1 μg/μL in the absence or presence of GW9662 (5 μL, 40 μM) for 48 h. (e–g) The phospohrylation of PPARγ and protein levels of ABCA1 and PEN-2 were analyzed by Western blot and β-actin served as the internal control. Intracellular levels of cholesterol (h–j) or the levels of Aβ1-42 (k-m) were determined by ELISA. (n) The aggregated form of Aβ determined by SDD-AGE (upper panel). The relative intensity of SDD-AGE bands was calculated by the Image J software (lower panel). The data represent means ± S.E. of 6 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 compared to vehicle-treated cells or mice. ###p < 0.001 compared to PGA1-treated cells

To further validate the above observations, the treatment of APPsw cells with PGA1 induced the phosphorylation of PPARγ (Fig. 5a). In addition, treatment of cells with GW9662, a specific PPARγ antagonist, abrogated the effects of PGA1 on upregulating the expression of ABCA1 (Fig. 5e). Moreover, GW9662 completely hindered the process of cholesterol efflux induced by PGA1 (Fig. 5h). Similarly, GW9662 abolished the effects of PGA1 on decreasing the levels of Aβ (Fig. 5k). Taken together, these observations prompted us to conclude that PPARγ/ABCA1/CHO signalling pathway was responsible for mediating the effects of PGA1 on reducing the levels of Aβ in vitro. Therefore, we next examined this regulatory mechanism in vivo. As shown in Fig. 5f, g, i, j, the regulation of these key elements by PGA1 in the Hip and Cor of APP/PS1 Tg mice was consistent with the findings from APPsw cells. In addition, GW9662 inhibits the effects of PGA1 on suppressing the production of Aβ monomers and low molecular weight Aβ oligomers in the CSF, Hip and Cor of APP/PS1 Tg mice (Fig. 5l–n). Therefore, the PPARγ/ABCA1/CHO signalling pathway plays an essential role in mediating the effects of PGA1 on reducing the production and aggregation of Aβ.

PGA1 Administration Alleviates the Cognitive Decline of APP/PS1 Tg Mice

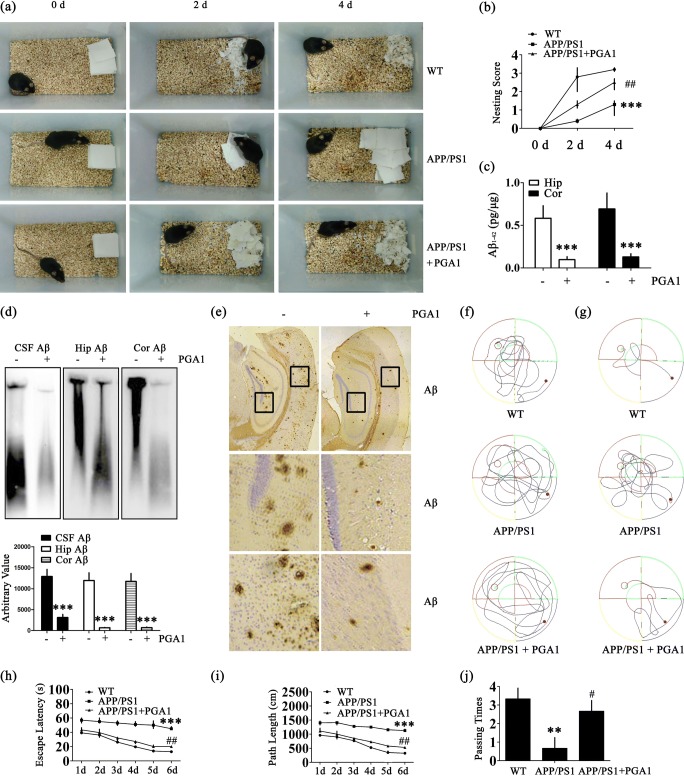

Because the PGA1 treatment attenuated Aβ production by suppressing the expression of PEN-2, we next investigated the effect of long-term administration of PGA1 on improving the memory of APP/PS1 Tg mice. Intranasal administration of PGA1 (2.5 mg/kg/day) was initiated at 6 months of age. After 3 months of PGA1 treatment, we assessed social behaviors and spatial learning and memory abilities using the nest construction and Morris water maze tasks. Nest construction is an affiliative social behavior, and it became progressively impaired in APP/PS1 Tg mice; this impairment was partially reversed by the PGA1 treatment (Fig. 6a, b). Long-term administration of PGA1 remarkably decreased the levels of different forms of Aβ, namely, Aβ monomers, oligomers, and fibrils (Figs. 6c–e and S5b). The results of the pretraining visible platform tests from the APP/PS1 and PGA1-treated APP/PS1 groups did not differ from the WT groups (Fig. 6f), suggesting that neither APP/PS1 overexpression nor PGA1 administration significantly altered the motility or vision of the WT mice. In the hidden platform tests, untreated APP/PS1 Tg mice exhibited unequivocal learning deficits in this task. The PGA1-treated APP/PS1 Tg mice performed similarly to the WT mice (Fig. 6g–i). When we performed a probe test 24 h after the last training trial, the untreated APP/PS1 Tg mice showed no preference for the target quadrant, indicating significant memory impairment, whereas the PGA1-treated APP/PS1 Tg mice performed as well as the WT mice (Fig. 6j).

Fig. 6.

Learning ability was improved in PGA1-treated APP/PS1 Tg mice. (a, b, f–j) Morris water maze and nest construction test were performed in 9-month-old WT and APP/PS1 Tg mice treated with or without PGA1 (2.5 mg/kg/day) for 3 months via an intranasal instillation. (c–e) Aβ was detected in 12-month-old WT and APP/PS1 Tg mice treated with or without PGA1 (2.5 mg/kg/day) for 6 months via an intranasal instillation. (a) Nest construction was quantified. Baseline data were obtained on 0 day, after the addition of paper towels to clean cages. (b) Habituation behaviour was recorded daily. (c) Aβ1-42 levels were determined by ELISA. (d) The aggregated forms of Aβ in the CSF, Hip, or Cor of APP/PS1 Tg mice were analyzed by SDD-AGE (upper panel). The relative intensity of SDD-AGE bands was calculated by the Image J software (lower panel). (e) Aβ immunoreactivity was determined by IHC with an anti-Aβ antibody. (f–j) Cognitive ability was evaluated using the Morris water maze test. (f) The escape paths used by the mice in the different groups to locate the pretraining visible platform tests from 1 to 2 days are shown. The escape paths (g), escape latency (h), and path length (i) are shown in the hidden platform tests. (j) In the probe trial, the number of times mice in the different groups passed over the previous location of the platform was recorded. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to WT mice or vehicle-treated APP/PS1 Tg mice. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to vehicle-treated APP/PS1 Tg mice

In summary, PGA1 activates the signalling pathways in APP/PS1 Tg mice, which promoted cholesterol efflux. Highly activated signalling pathways of PPARγ/ABCA1/CHO result in the suppression of PEN2, which improved the cognitive decline of AD by inhibiting the production and deposition of Aβ.

Discussion

PGA1 Exerts a Neuroprotective Effect on AD Models

Recently, PGA1 has been reported to exert neuroprotective effects because it blunts N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-mediated neuronal apoptosis and inhibits enhancement of the intracellular calcium concentration, TXA2 production, and platelet activation in rodent models of stroke [50]. Our experimental results are clearly consistent with this hypothesis that PGA1 suppressed the production and aggregation of Aβ, which is extremely toxic to neurons. In agreement with our observations, a series of investigations have validated our data suggesting that PGA1 may have cytoprotective activity against oxidative stress in monocytes and macrophages [51] and inhibits the apoptosis of striatal neuron in rat striatum [14]. In addition, whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing indicated that PGA1 regulates a large number of neuroprotective pathways, such as inflammatory, NF-κB, and AD pathways. Mass spectrometry further identified multiple neuroprotection-associated molecules, heat shock proteins, and the microtubule-associated protein (tau) as the activating targets of PGA1 (data not shown). Therefore, we postulate that PGA1 regulates AD through a comprehensive mechanism involving multiple elements. As we are interested in deciphering the mechanisms of PGA1 in protecting the nervous system, we firstly investigated its roles in producing Aβ by regulating the expression of secretases, such as β- or γ-secretase. As a consequence, PGA1 did not regulate the activity of β-secretase, BACE-1. We thereby focused our analysis on the activity of γ-secretase, which is a membrane protein complex comprised of presenilins, nicastrin (NCT), anterior pharynx-defective-1α and anterior pharynx-defective-1β (APH-1α/1β), and presenilin enhancer protein 2 (PEN-2) [52]. Among these subunits of γ-secretase, PEN-2 was significantly suppressed by PGA1 (Fig. 1c–e). Of note, the activity of PEN-2 is responsible for the production of Aβ, as evidenced by the fact that PEN-2 is overexpressed in AD models [53, 54]. In addition, PEN-2 is required for Notch signalling pathway, through which γ-secretase cleaved sAPPβ to produce Aβ. Therefore, we focused on its ability to regulate the production of sAPPα, sAPPβ, and Aβ. As expected, short-term administration of PGA1 significantly reduced the levels of Aβ monomers and oligomers in AD models. Long-term administration of PGA1 induced relatively substantial degradation of Aβ fibrils, which improved the memory and learning abilities of APP/PS1 Tg mice.

PGA1 Activates PPARγ Through a Transcription-Dependent Mechanism, Which in Turn Modulating the Development and Progression of AD

PPARγ is a widely expressed receptor that governs the expression of genes involved in the development and progression of metabolic diseases [55, 56]. PPARγ has been identified as the natural receptor of PGs, such as 15d-PGJ2, through which modulates the biological functions of microglial cells [57]. Apart from 15d-PGJ2, Yu et al. disclosed that PGA1 also played a physiological role via activating PPARγ. According to these observations, PGA1 might exert its effects via PPARγ. To this hypothesis, prior works have demonstrated that PGA1 regulates the vast majority of physiological processes by Michael addition and transcription-dependent regulatory pathways [58]. For Michael addition, α,β-unsaturated ketone is a core moiety of natural ligands for covalently binding to PPARγ [59]. However, our data showed no evidence of Michael addition as a regulatory approach (Fig. 5b). In contrast, our data are consistent with prior works [10] showing that PGA1 tends to regulate the activity of PPARγ at the transcriptional levels (Fig. 5c). Indeed, the activation of PPARγ has been reported to be efficacious in reducing the incidence and risk of AD and delaying the progression of the disease [60]. To the reason, the ability of PPARγ in reducing levels of cytokines-induced soluble Aβ1-42 peptide might be the inherent cause for delaying the development of AD [61]. Of note, activation of PPARγ is also able to inhibit the progression of AD via activating ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family proteins [62]. In addition, there is report suggesting that PPARγ induces a fast, cell-bound clearing mechanism responsible for the removal of the Aβ [63]. To the mechanism, PPARγ agonists strongly reduced the activities of β- or γ-secretase [19]. More convincingly, rapid activation of PPARγ improved the cognitive decline of murine model of AD via decreasing the loading of Aβ [64]. Along these lines, PGA1 delayed the development and progression of AD via activating PPARγ (Fig. 5).

Cholesterol Acts as a Bridge in the Mechanism by Which PGA1 Regulates the AD Model

Although no reports have identified the connection between PGA1 and cholesterol, recent findings have indicated that elevated serum and plasma levels of cholesterol are a potential risk factor for the development of AD [65]. By high-throughput sequencing, we found that PGA1 potentially regulates cholesterol metabolism and lipid transport. Therefore, we speculated that lipid metabolism plays an extremely important role in the mechanism by which PGA1 regulates AD. Next, this hypothesis was confirmed, as PGA1 reduced cholesterol levels, whereas an overdose of cholesterol reversed the regulatory effect of PGA1 on AD models (Fig. 2). By these observations, the question is easily rose if there is the natural relationship between cholesterol and AD. In Aβ23-35-injected APOE knockout mice, diet-induced hypercholesterolemia induces the deposition of Aβ in APs [18]. This observation was further supported by the findings in mice fed diets enriched in cholesterol [66, 67]. To the reason, cholesterol was found to be colocalized with most of the components involved in amyloidogenic pathway, such as APP, the proteolytic enzymes BACE1 and PS1/2, Aβ, and γ-secretase in lipid rafts [68, 69]. More closely, cholesterol can regulate APP accumulation in lipid rafts and amyloidogenesis because C99 fragment of APP (product of APP cleavage by BACE1) exhibits a binding site for cholesterol [70, 71]. Moreover, the α-secretase activity that depends on membrane fluidity is reversibly modulated by cholesterol [71], which inhibits the secretion of sAPPα. Apart from regulating the activity of α-secretase, cholesterol was also reported to induce the expression of the PS1 and PS2 in SK-N-BE cells [72]. Based on these observations, we extended the prior works to find that cholesterol stimulated the expression of PEN-2, which is an integral component of the γ-secretase complex [73]. As the critical roles of cholesterol in the activities of secretases, we further found that cholesterol had the ability to induce the production of Aβ, which results in the cognitive decline of AD [74]. In line with our observations, cholesterol was also reported to be required for Aβ formation, aggregation, and deposition, and cholesterol depletion inhibited the generation and aggregation of Aβ [74–76]. Furthermore, we also came to a conclusion consistent with our report showing that cholesterol plays a role in late stage of cognitive function and the risk of dementia [77]. In detail, lowering the levels of cholesterol prevented cognitive decline via decreasing amyloidogenic process [78]. Given the critical roles of PGA1 on cholesterol efflux, PGA1 was found to be responsible for ameliorating the cognitive decline of AD via deactivating PEN2 in a cholesterol-dependent mechanism.

ABCA1 Plays an Important Role in Mechanism by Which PGA1 Regulates AD Models

Given the critical roles of cholesterol in AD, we further explored the mechanisms. As a consequence, we found that ABCA1 involved in the process (Figs. 3 and 4). In agreement with our observations, statins, which is able to lower the levels of serum cholesterol, have also been proposed for treating AD [79]. Compared to statins, PGA1 has the ability to induce cholesterol efflux as a natural substance produced in the body with lower side effects [80]. In addition, PGA1 showed its effects on inducing the expression of ABCA1 (Fig. 3h–j). In concert with our observation, Chawla et al. [81] reported that ligand activation of PPARγ leads to the induction of ABCA1.

As a gatekeeper for eliminating excess tissue cholesterol levels, ABCA1 is temporally expressed in the developing and adult mouse brain [82]. In addition, ABCA1 is highly expressed in the Hip, Cor and choroids plexus [83]. Moreover, Yassine et al. [84] suggested that the ABCA1, which is responsible for cholesterol efflux to the CSF, is reduced in patients with mild cognitive impairment and AD. In addition, loss-of-function ABCA1 gene variants are associated with an increased risk of AD [85]. More closely, ABCA1 has the ability to decrease the activity of γ-secretase via inhibiting its recruitment to C99 [86]. In addition, activation of ABCA1 reduces Aβ levels, which results in improving outcome after traumatic brain injury [87]. By regulating cholesterol homeostasis, ABCA1 deeply influences synaptic function and improves cognitive decline [88]. Thus, as an upregulator of ABCA1 expression, PGA1 may provide a new therapeutic benefit for patients with cardiovascular disease and AD.

PPARγ Is Indispensable for PGA1-Mediated Regulation of ABCA1 Expression

As PGA1 has the ability to activate both PPARγ and ABCA1, we are prompted to reveal the inherent relationship among these molecules. The results demonstrated that PGA1 upregulated the expression of ABCA1 via PPARγ pathway (Fig. 5). In concert with our observations, previous studies have revealed that activation of PPARγ enhanced the expression of ABCA1 by PPAR agonists 15d-PGJ2 [89, 90]. Moreover, PPAR agonists and antagonists could also alter cholesterol efflux, which is critical for the pathogenesis of AD [91]. Hence, PPARγ is indispensable for PGA1-regulated expression of ABCA1. Based on these findings, we confirmed that PGA1 is useful for treating AD via upregulating the expression of ABCA1 via PPARγ in a cholesterol efflux-dependent mechanism.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 4323 kb)

(XLS 41 kb)

(XLSX 78 kb)

(PDF 487 kb)

(PDF 487 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part or in whole by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81870840, 31571064, 81771167, and 81500934) and the Fundamental Research Foundation of Northeastern University, China (N172008008 and N172004005).

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhan-You Wang, Email: wangzy@mail.neu.edu.cn.

Pu Wang, Email: wangpu@mail.neu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Smith WL, Marnett LJ, DeWitt DL. Prostaglandin and thromboxane biosynthesis. Pharmacol Therapeut. 1991;49:153–179. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90054-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cudaback E, Jorstad NL, Yang Y, Montine TJ, Keene CD. Therapeutic implications of the prostaglandin pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazan NG, Colangelo V, Lukiw WJ. Prostaglandins and other lipid mediators in Alzheimer’s disease. Prostag Oth Lipid M. 2002;68-69:197–210. doi: 10.1016/S0090-6980(02)00031-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang P, Guan P-P, Guo J-W, et al. Prostaglandin I2 upregulates the expression of anterior pharynx-defective-1α and anterior pharynx-defective-1β in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 transgenic mice. Aging Cell. 2016;15:861–871. doi: 10.1111/acel.12495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson JU, Woodling NS, Wang Q, et al. Prostaglandin signaling suppresses beneficial microglial function in Alzheimer’s disease models. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:350–364. doi: 10.1172/JCI77487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang X, Wu L, Hand T, Andreasson K. Prostaglandin D2 mediates neuronal protection via the DP1 receptor. J Neurochem. 2005;92:477–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scher JU, Pillinger MH. 15d-PGJ2: the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin? Clin Immunol. 2005;114:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueiredo-Pereira ME, Corwin C, Babich J. Prostaglandin J2: a potential target for halting inflammation-induced neurodegeneration. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2016;1363:125–137. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H-L, Huang ZH, Zhu Y, et al. Neuroprotective effects of prostaglandin A1 in animal models of focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2005;1039:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H-L, Gu Z-L, Savitz SI, et al. Neuroprotective effects of prostaglandin A1 in rat models of permanent focal cerebral ischemia are associated with nuclear factor-κB inhibition and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ up-regulation. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1132–1141. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garzón B, Gayarre J, Gharbi S, et al. A biotinylated analog of the anti-proliferative prostaglandin A1 allows assessment of PPAR-independent effects and identification of novel cellular targets for covalent modification. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;183:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Qin ZH, Leng Y, et al. Prostaglandin A1 inhibits rotenone-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1094–1102. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirata Y, Furuta K, Suzuki M, et al. Neuroprotective cyclopentenone prostaglandins up-regulate neurotrophic factors in C6 glioma cells. Brain Res. 2012;1482:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin Z-H, Wang Y, Chen R-W, et al. Prostaglandin A1 protects striatal neurons against excitotoxic injury in rat striatum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:78–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ittner LM, Götz J. Amyloid-β and tau—a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;12:67. doi: 10.1038/nrn2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nitsch RM, Hock C. Targeting β-amyloid pathology in Alzheimer’s disease with Aβ immunotherapy. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Refolo LM, Pappolla MA, Malester B, et al. Hypercholesterolemia accelerates the Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:321–331. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong H, Callaghan D, Jones A, et al. Cholesterol retention in Alzheimer’s brain is responsible for high β- and γ-secretase activities and Aβ production. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fassbender K, Simons M, Bergmann C, et al. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid peptides Aβ42 and Aβ40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081620098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Paolo G, Kim T-W. Linking lipids to Alzheimer’s disease: cholesterol and beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:284–296. doi: 10.1038/nrn3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puglielli L, Konopka G, Pack-Chung E, et al. Acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase modulates the generation of the amyloid β-peptide. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:905–912. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C-C, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huttunen HJ, Kovacs DM. ACAT as a drug target for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5:212–214. doi: 10.1159/000113705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wahrle SE, Jiang H, Parsadanian M, et al. Overexpression of ABCA1 reduces amyloid deposition in the PDAPP mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:671–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI33622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wahrle SE, Jiang H, Parsadanian M, et al. Deletion of Abca1 increases Aβ deposition in the PDAPP transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43236–43242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirier J. Apolipoprotein E and cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med. 2003;9:94–101. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(03)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awad AB, Toczek J, Fink CS. Phytosterols decrease prostaglandin release in cultured P388D1/MAB macrophages. Prostag Leukotr Ess. 2004;70:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore KJ, El Khoury J, Medeiros LA, et al. A CD36-initiated signaling cascade mediates inflammatory effects of β-amyloid. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47373–47379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubic T, Trottmann M, Lorenz RL. Stimulation of CD36 and the key effector of reverse cholesterol transport ATP-binding cassette A1 in monocytoid cells by niacin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wollmer MA, Streffer JR, Lütjohann D, et al. ABCA1 modulates CSF cholesterol levels and influences the age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:421–426. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu X, Guan P-P, Guo J-W, et al. By suppressing the expression of anterior pharynx-defective-1α and -1β and inhibiting the aggregation of β-amyloid protein, magnesium ions inhibit the cognitive decline of amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2015;29:5044–5058. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-275578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo JW, Guan PP, Ding WY, et al. Erythrocyte membrane-encapsulated celecoxib improves the cognitive decline of Alzheimer’s disease by concurrently inducing neurogenesis and reducing apoptosis in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Biomaterials. 2017;145:106–127. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morales-Corraliza J, Schmidt SD, Mazzella MJ, et al. Immunization targeting a minor plaque constituent clears β-amyloid and rescues behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, Herukka S-K, Minkeviciene R, van Groen T, Tanila H. Longitudinal observation on CSF Aβ42 levels in young to middle-aged amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 doubly transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piermartiri TCB, Figueiredo CP, Rial D, et al. Atorvastatin prevents hippocampal cell death, neuroinflammation and oxidative stress following amyloid-β1-40 administration in mice: evidence for dissociation between cognitive deficits and neuronal damage. Exp Neurol. 2010;226:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halfmann R, Lindquist S. Screening for amyloid aggregation by semi-denaturing detergent-agarose gel electrophoresis. J Vis Exp 2008; 17: 10.3791/3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Manuela D’ I-C, Dolores P-S, Lamas S. Dual effect of nitric oxide donors on cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:943–952. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V105943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diepenbruck M, Tiede S, Saxena M, et al. miR-1199-5p and Zeb1 function in a double-negative feedback loop potentially coordinating EMT and tumour metastasis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1168. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01197-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Zhang S, Blander G, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates and positively regulates the nuclear receptor LXR. Mol Cell. 2007;28:91–106. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X-H, Zhang H-L, Han R, Gu Z-L, Qin Z-H. Enhancement of neuroprotection and heat shock protein induction by combined prostaglandin A1 and lithium in rodent models of focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2006;1102:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolozin B. Cholesterol and the biology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2004;41:7–10. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00840-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanson AJ, Prasad JE, Nahreini P, et al. Overexpression of amyloid precursor protein is associated with degeneration, decreased viability, and increased damage caused by neurotoxins (prostaglandins A1 and E2, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric oxide) in differentiated neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:148–159. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Zhou S, Burgess BL, et al. Deficiency of ABCA1 impairs apolipoprotein E metabolism in brain. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41197–41207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim WS, Rahmanto AS, Kamili A, et al. Role of ABCG1 and ABCA1 in regulation of neuronal cholesterol efflux to apolipoprotein E discs and suppression of amyloid-β peptide generation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2851–2861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu X, Guan PP, Zhu D, et al. Magnesium ions inhibit the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha and the activity of gamma-secretase in a beta-amyloid protein-dependent mechanism in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:172. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giaginis C, Tsourouflis G, Theocharis S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) ligands: novel pharmacological agents in the treatment of ischemia reperfusion injury. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:562–579. doi: 10.2174/156652408785748022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kulkarni AA, Thatcher TH, Olsen KC, et al. PPAR-gamma ligands repress TGFbeta-induced myofibroblast differentiation by targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway: implications for therapy of fibrosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Y, Gu ZL, Liang ZQ, Zhang HL, Qin ZH. Prostaglandin A1 inhibits increases in intracellular calcium concentration, TXA(2) production and platelet activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:549–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HY, Kim JR, Kim HS. Upregulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-10 by prostaglandin A1 in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;18:1170–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Strooper B. Aph-1, pen-2, and nicastrin with presenilin generate an active γ-secretase complex. Neuron. 2003;38:9–12. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crystal AS, Morais VA, Fortna RR, et al. Presenilin modulates pen-2 levels posttranslationally by protecting it from proteasomal degradation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3555–3563. doi: 10.1021/bi0361214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nam SH, Seo SJ, Goo JS, et al. Pen-2 overexpression induces Abeta-42 production, memory defect, motor activity enhancement and feeding behavior dysfunction in NSE/Pen-2 transgenic mice. Int J Mol Med. 2011;28:961–971. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monsalve FA, Pyarasani RD, Delgado-Lopez F, Moore-Carrasco R. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor targets for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Mediat Inflamm. 2013;2013:549627. doi: 10.1155/2013/549627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chawla A, Barak Y, Nagy L, et al. PPAR-γ dependent and independent effects on macrophage-gene expression in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nat Med. 2001;7:48–52. doi: 10.1038/83336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernardo A, Levi G, Minghetti L. Role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) and its natural ligand 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 in the regulation of microglial functions. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2215–2223. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elia G, Polla B, Rossi A, Santoro MG. Induction of ferritin and heat shock proteins by prostaglandin A1 in human monocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1999;264:736–745. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shiraki T, Kamiya N, Shiki S, et al. Alpha,beta-unsaturated ketone is a core moiety of natural ligands for covalent binding to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14145–14153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Landreth G, Jiang Q, Mandrekar S, Heneka M. PPARγ agonists as therapeutics for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heneka MT, Sastre M, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, et al. Acute treatment with the PPARgamma agonist pioglitazone and ibuprofen reduces glial inflammation and Abeta1-42 levels in APPV717I transgenic mice. Brain. 2005;128:1442–1453. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koldamova R, Fitz NF, Lefterov I. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1: from metabolism to neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;72:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Camacho IE, Serneels L, Spittaels K, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ induces a clearance mechanism for the amyloid-β peptide. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10908–10917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3987-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mandrekar-Colucci S, Karlo JC, Landreth GE. Mechanisms underlying the rapid peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-mediated amyloid clearance and reversal of cognitive deficits in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32:10117–10128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5268-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gibson WW, Ling L, MW E, EG P. Cholesterol as a causative factor in Alzheimer’s disease: a debatable hypothesis. J Neurochem. 2014;129:559–572. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shie F-S, Jin L-W, Cook DG, Leverenz JB, LeBoeuf RC. Diet-induced hypercholesterolemia enhances brain Aβ accumulation in transgenic mice. Neuroreport. 2002;13:455–459. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200203250-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thirumangalakudi L, Prakasam A, Zhang R, et al. High cholesterol-induced neuroinflammation and amyloid precursor protein processing correlate with loss of working memory in mice. J Neurochem. 2008;106:475–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arbor SC, LaFontaine M, Cumbay M. Amyloid-beta Alzheimer targets—protein processing, lipid rafts, and amyloid-beta pores. Yale J Biol med. 2016;89:5–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Colin J, Gregory-Pauron L, Lanhers M-C, et al. Membrane raft domains and remodeling in aging brain. Biochimie. 2016;130:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barrett PJ, Song Y, Van Horn WD, et al. The amyloid precursor protein has a flexible transmembrane domain and binds cholesterol. Science. 2012;336:1168. doi: 10.1126/science.1219988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang X, Sun GY, Eckert GP, JC-M L. Cellular membrane fluidity in amyloid precursor protein processing. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;50:119–129. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8652-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crestini A, Napolitano M, Piscopo P, Confaloni A, Bravo E. Changes in cholesterol metabolism are associated with PS1 and PS2 gene regulation in SK-N-BE. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;30:311–322. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:3:311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kimberly WT, LaVoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, et al. γ-Secretase is a membrane protein complex comprised of presenilin, nicastrin, aph-1, and pen-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6382–6387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037392100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]