Abstract

Policy Points.

Stigma is an established driver of population‐level health outcomes. Antidiscrimination laws can generate or alleviate stigma and, thus, are a critical component in the study of improving population health.

Currently, antidiscrimination laws are often underenforced and are sometimes conceptualized by courts and lawmakers in ways that are too narrow to fully reach all forms of stigma and all individuals who are stigmatized.

To remedy these limitations, we propose the creation of a new population‐level surveillance system of antidiscrimination law and its enforcement, a central body to enforce antidiscrimination laws, as well as a collaborative research initiative to enhance the study of the linkages between health and antidiscrimination law in the future.

Context

Stigma is conceptualized as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Antidiscrimination law is one important lever that can influence stigma‐based health inequities, and yet several challenges currently limit the law's potential to address them.

Methods

To determine whether antidiscrimination law adequately addresses stigma, we compared antidiscrimination law for its applicability to the domains and statuses where stigma is experienced according to the social science literature. To further examine whether law is a sufficient remedy for stigma, we reviewed law literature and government sources for the adequacy of antidiscrimination law enforcement. We also reviewed the law literature for critiques of antidiscrimination law, which revealed conceptual limits of antidiscrimination law that we applied to the context of stigma.

Findings

In this article, we explored the importance of antidiscrimination law in addressing the population‐level health consequences of stigma and found two key challenges—conceptualization and enforcement—that currently limit its potential. We identified several practical solutions to make antidiscrimination law a more available tool to tackle the health inequities caused by stigma, including (1) the development of a new surveillance system for antidiscrimination laws and their enforcement, (2) an interdisciplinary working group to study the impact of antidiscrimination laws on health, and (3) a central agency tasked with monitoring enforcement of antidiscrimination laws.

Conclusions

Antidiscrimination law requires better tailoring based on the evidence of who is affected by stigma, as well as where and how stigma occurs, or it will be a poor tool for remedying stigma, regardless of its level of enforcement. Further interdisciplinary research is needed to identify the ways in which law can be crafted into a better tool for redressing the health harms of stigma and to delimit clearer boundaries for when law is and is not the appropriate remedy for these stigma‐induced inequities.

Keywords: stigma, antidiscrimination law, civil rights protections, population health

Civil rights are at a critical juncture. a majority of Americans report experiencing discrimination,1 and stigma and discrimination pervade many facets of ordinary life, from whether we obtain mental health or substance abuse treatment, to how we police our borders and our communities, to how women are treated in the workplace. Yet, the federal government is currently reducing antidiscrimination protections by, for instance, cutting federal civil rights agencies’ budgets and taking legal stances against antidiscrimination protections for sexual minorities in health care,2 employment,3 and public accommodations.4 This diminishment of antidiscrimination and civil rights laws comes at a time when researchers increasingly observe that stigma is a driver of health inequality across the population.5 The role of law in addressing population‐level health harms from stigma needs to be better understood, especially in light of the current erosion of these protections. Foremost, the paper emphasizes that antidiscrimination law is one important lever that can influence population health inequities. To that end, we present a preliminary discussion of two key challenges—conceptualization and enforcement—that currently limit the law's potential to address stigma‐based health inequalities, and we identify several practical solutions that act as starting points to address these challenges.

We divide our discussion into five sections. First, we introduce the concept of stigma and the various ways it drives population health inequality. Second, we briefly describe prior studies on how law can ameliorate or exacerbate stigma. In the third and fourth sections, we discuss two key challenges that limit the scope of law in reducing stigma‐based health harms at a population level. One challenge is conceptual problems that limit the law's reach, including protected‐class frameworks that do not accord with all of the groups and domains where stigma occurs, and an overemphasis on interpersonal stigma over structural forms of discrimination. A second challenge is enforcement of antidiscrimination laws. Enforcement includes private lawsuits by harmed individuals, government lawsuits against bad actors, and actions by government agencies to monitor and ensure compliance with the law. In many instances, enforcement is weak and insufficient to capture the full range of harms. In the final section, we address the question, if the law plays an important role in redressing stigma but currently faces several obstacles, then what can be done? We offer some concrete solutions, large and small, to advance the role of law in reducing stigma‐based inequalities. Our paper is the beginning, we hope, of further exploration and discussion across disciplines on this important topic.

Stigma and Population Health Inequalities

Since Goffman's pioneering book Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity,6 published in the early 1960s, social scientists have been interested in understanding the causes and consequences of stigma. Amidst this proliferation of research, a number of definitions of stigma have been offered in the literature, which led to some confusion about what the term means and its boundary characteristics. In part to address this confusion, Link and Phelan advanced a highly influential conceptualization of stigma,7 which defines stigma as follows:

In our conceptualization, stigma exists when the following interrelated components converge. In the first component, people distinguish and label human differences. In the second, dominant cultural beliefs link labeled persons to undesirable characteristics—to negative stereotypes. In the third, labeled persons are placed in distinct categories so as to accomplish some degree of separation of “us” from “them.” In the fourth, labeled persons experience status loss and discrimination that lead to unequal outcomes. Stigmatization is entirely contingent on access to social, economic and political power that allows the identification of differentness, the construction of stereotypes, the separation of labeled persons into distinct categories and the full execution of disapproval, rejection, exclusion and discrimination. Thus we apply the term stigma when elements of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination co‐occur in a power situation that allows them to unfold.7 (p367)

Thus, in this conceptualization, discrimination at the interpersonal level (ie, unequal treatment that arises from group membership) and at the structural level (ie, societal conditions that constrain an individual's life chances) is a fundamental feature of stigma. In fact, the term stigma “cannot hold the meaning we commonly assign to it” when discrimination is absent.7 (p370) However, because stigma incorporates several other elements in addition to discrimination—including labeling and stereotyping—the stigma concept is broader than discrimination.5, 8 Moreover, there is a large body of literature demonstrating that stigma produces negative consequences even in the absence of discrimination, and even without another person present in the immediate situation.7, 9 Thus, we focus our analysis more broadly on stigma, rather than limit our scope to a discussion of discrimination, because this concept of stigma captures numerous pathways that produce disadvantage outside of discriminatory action.

Decades of social science research have repeatedly and robustly shown that stigma is pervasive,10 that it affects a substantial number of people,11 that it is a source of social inequalities in life chances that are themselves powerful determinants of health (including, but not limited to, education and academic achievement, housing, employment and income, and beneficial social relationships),5 and that it has a direct, corrosive impact on the health of populations.7, 12 For these reasons, stigma has been conceptualized as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities.5

Based on this literature, there is widespread agreement that ameliorating population health inequalities requires targeting stigma and its negative consequences. Stigma is a multifaceted phenomenon and reducing it requires a multilevel, multipronged approach,7 of which law is one, among many, important levers. Our contribution in this article is to consider the role, scope, and potential limitations of law in addressing population‐level stigma‐based health inequalities. For brevity, we use the term law throughout the paper to mean antidiscrimination statutes, although we occasionally consider agency regulations or judges’ opinions.

Stigma and Law

The intersection between stigma and the law is not new. Researchers have underscored these linkages both conceptually13, 14, 15 and empirically.16 The role of the law in diminishing or perpetuating stigma against particular groups—particularly stigma in the context of disability,17 abortion,18 and obesity19—are just some examples of the focus of legal research. Furthermore, scholars have considered some of the potential pathways through which the law may affect stigma processes. Law may reach stigma by serving an expressive function. As Burris observes, law can send messages about which social distinctions are salient, as categorizations of “good” or “bad” differences are underscored by the legislatures and the courts13—for example, early courts’ advocating for HIV‐positive children to have access to public schools. Law can also provide potential remedies14 and deter discriminatory behaviors, including hate crimes that target stigmatized groups.20 Lastly, law can operate to address stigma by promoting resistance among the stigmatized. For example, advocates can use the law as a way of mobilizing groups (for example, early advocacy around HIV/AIDS), and it can change individual perceptions of stigma by helping shift individuals’ self‐identities to rights‐bearers rather than oppressed victims.13

In this article, we argue that law is central to any effort to reduce stigma‐based health harms13, 14, 17, 18, 19 for two reasons. First, social scientists have initiated a recent line of work on the role of law in shaping the distribution of life chances among members of stigmatized groups.16 A review of this literature is beyond the scope of the current paper, but a few examples illustrate this point. Using a quasi‐experimental design, Krieger and colleagues documented that in the years preceding the abolition of Jim Crow laws, the infant death rate among blacks was higher in states with Jim Crow laws than in states without these laws; in the years following the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which overturned Jim Crow laws, the infant death rate among blacks was statistically indistinguishable between the Jim Crow and non–Jim Crow states.21 There was no temporal change in the relationship between the abolition of Jim Crow laws by birth cohort for white infants, documenting result specificity to the stigmatized group. In another quasi‐experimental study, researchers showed that lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals who lived in states that implemented laws denying services to same‐sex couples (also known as religious exemption laws) experienced a 46% relative increase in mental distress; there was no association between the law and mental health among heterosexual populations, documenting specificity to the stigmatized group.22 Thus, there is ample social science data indicating that laws can either (1) reinforce stigma processes, thereby creating or exacerbating health inequalities, or (2) interrupt stigma processes, and in so doing mitigate harm against members of stigmatized groups.

Second, laws and policies reflect cultural values;23 however, recent research has also provided evidence that laws and policies shape individual attitudes as well as collective social norms about members of stigmatized groups.24, 25, 26, 27 For instance, after laws banning same‐sex marriage were passed, respondents reported even more negative attitudes toward gays and lesbians compared to their initial attitudes before the law was passed;28 conversely, following the Supreme Court decision ruling in favor of same‐sex marriage in 2015, respondents reported an increase in perceived social norms—that is, impressions of what opinions or behaviors are common among a particular group of people—supporting same‐sex marriage.25 Taken together, the legal and social science literature indicates that the law represents an important remedy for reducing stigma (in the form of attitudes) and its negative health consequences for the stigmatized, and thus provides support for our focus on the law as one lever (among many) for addressing stigma‐based harms.

We have narrowed the scope of this paper to focus on antidiscrimination laws, which, though they do not mention stigma by name, are designed to address intentional or unintentional differential treatment of groups of people based on shared traits. We recognize that other bodies of law may also have an indirect or direct impact on stigma processes; voting rights, education law, and constitutional protections are a few examples. A full discussion of other legal issues is beyond the scope of this paper but merits consideration in future research. We focus on federal law because protections are eroding there and because federal law represents the universal floor for legal protections for all citizens; state and local laws can sometimes be more protective but, without adequate federal safeguards, they also can be less so, especially in environments where stigma is prevalent.29 Future research might consider state and local law, or even professional guidelines, as tools for fighting stigma.

Limits of Antidiscrimination Law: Conceptual

We begin with a simple question of whether federal antidiscrimination law covers all of the people and places where the empirical literature demonstrates that stigma prevails. Finding that it does not, we discuss key conceptual limits that weaken antidiscrimination law's ability to address health‐harming stigma.

Stigma Domains and Groups

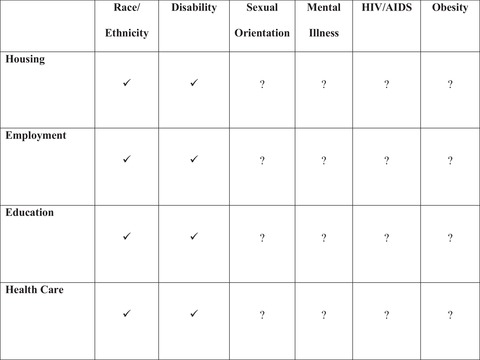

To address this topic, we drew on the work of Hatzenbuehler and colleagues,5 who reviewed the literature on six stigmatized statuses (ie, race/ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, mental illness, HIV/AIDS, and obesity) together with multiple stigma‐related domains (eg, housing, education, employment, health care). We then searched relevant federal antidiscrimination statutes (and, where necessary, regulations and court cases) to determine whether current federal antidiscrimination laws address these stigmatized statuses and domains identified by Hatzenbuehler and colleagues’ review.5 We found that the law addresses some but not all of these stigmatized statuses in some but not all of these domains (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Federal Antidiscrimination Law and Common Types of Stigma

Data derived from authors’ analysis of federal antidiscrimination laws related to six statuses (race, disability, sex, mental illness, HIV/AIDS, and obesity) across four domains (housing, employment, education, health care).5 Check marks designate explicit coverage of the status and domain. Question marks designate uncertainty, typically that the status itself is not explicitly covered by the law, but not necessarily that it is outright excluded. Typically, instead, the litigant must meet additional legal criteria. For example, statutes do not explicitly address HIV discrimination; instead, a litigant must show that HIV is a disability.

Specifically, discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities is explicitly covered by antidiscrimination laws in all four resource‐related domains, as is discrimination against people with disabilities if they meet certain criteria that their disability affects major life activities. The Fair Housing Act prohibits some forms of discrimination in housing for race and disability, while the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 also prohibit some housing discrimination against disabled persons. Employment discrimination is prohibited under the ADA and the Rehab Act for disability and Titles VI and VII for race‐based claims. Education claims are governed under the Individuals with Disability Education Act (IDEA), Rehab Act, and ADA for the disabled, and Title VI for race‐based claims. Health care has had the smallest number of antidiscrimination protections historically. The ADA prohibits discrimination in private doctors’ offices, private hospitals, and insurers under Title III. Apart from disability, nondiscrimination prohibitions have mainly been limited to entities receiving federal funding, but this has expanded greatly with Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, which extends antidiscrimination protections for many private and public health care providers and insurers on the basis of race, sex, age, and disability. Even if these protections are offered in name for racial/ethnic minorities and individuals with disabilities, there may be various challenges to actually enforcing such laws, as will be discussed in later sections.

In contrast, for other stigmatized groups (sexual minorities and people with HIV/AIDS, obesity, or mental illness), protection is not explicit; instead, the litigant must tie herself to some other protected identity to bring a successful claim. Sex discrimination is prohibited in housing by the Fair Housing Act, education by Title IX, employment by Title VII, and health care by Section 1557 of the ACA. Yet, sexual minorities (ie, LGBT populations) are not explicitly addressed in most antidiscrimination statutes, and courts and regulatory agencies have varied in whether these sex‐based laws extend to gender identity and sexual orientation. Federally, litigants typically have to claim sex stereotyping, for example, in the context of employment.30 During the Obama administration, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) clearly forbade sexual minority discrimination in employment. This stance has changed with the Trump administration, which has argued against including sexual minority protections in public accommodations,4 employment,3 and health care.2

At the state level, some states forbid discrimination against sexual orientation or gender identity in their public accommodation laws,31 but a majority of states do not. In the recent Supreme Court case, Masterpiece Cake Shop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission,4 the Department of Justice advocated for fewer rights for sexual minorities by arguing that public accommodation laws infringe on religious liberties for those individuals who do not wish to serve sexual minorities. In a narrow holding, Justice Kennedy appeared to take no issue with public accommodation laws that protect sexual minorities, but sided with the cake maker because the state's commission had violated religious neutrality.

Mental illness, HIV/AIDS, and obesity are also not expressly addressed by the law and, instead, people with these conditions must demonstrate that they are disabled. Courts have a record of clearly considering HIV/AIDS a disability.32 Not all mental illnesses will constitute a disability, however, just as not all physical conditions are disabilities. Courts will consider whether the mental illness substantially limits a major life activity, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) expressly excludes addiction from its scope unless the person is no longer using substances.33 Courts will often not consider obesity a disability unless it affects some other physiological function or the person with obesity clearly cannot perform job functions.34

Our analysis reveals a mismatch between social science and antidiscrimination law; despite the clear linkages between stigma and population health inequalities reviewed earlier,5 the law currently only reaches a small number of groups across a limited number of domains or contexts in which discrimination occurs. In sum, case‐by‐case, fragmented protections appear inadequate to ameliorate the population health effects of stigma as revealed in social science research. The lack of existing protections is further emphasized when one considers that the work of Hatzenbuehler and colleagues, whose work we drew on to create Figure 1, underestimates the full influence of stigma on life chances, because they chose only six stigmatized statuses that had been the focus of quantitative (eg, meta‐analytic) and qualitative reviews. Although the field has not reached consensus on the exact number of stigmatized identities/statuses, recent work by Pachankis et al.11 identifies as many as 93 stigmatized categories experienced in the general population (eg, criminal record, drug dependency, Muslim, undocumented immigrant, homeless), the vast majority of which are not explicitly recognized in the legal system as protected classes.

For the remainder of this section, we discuss how two conceptual flaws in antidiscrimination law—a reliance on protected classes, and an almost exclusive focus on interpersonal (as opposed to structural) discrimination—partly explain the law's current weakness in reaching stigma.

Protected Classes

The scope of existing antidiscrimination law is hindered, in large part, by a protected‐class framework undergirding the law, in which only certain classes are protected, leaving many stigmatized populations without access to legal recourse. To be sure, the protected‐class framework served important historical and political purposes. Identity‐based social movements have succeeded in garnering legal protections for certain groups, like racial minorities and women, in various civil rights movements throughout the 20th century.35 Further, identity‐based movements were, in part, necessary in order to frame rights under the equal protections clause and to organize rights‐seeking individuals around common goals and identities. However, protected‐class‐based approaches have been critiqued for overly narrowing legal protections to a few groups, while leaving out many stigmatized identities altogether, or for forcing groups to try to fit awkwardly into existing legal protections.36 Laws that focus on group protections can be problematic by entrenching and cultivating our understanding that some groups are inherently worthier of legal protection than others and by fueling group resentment.37

An emphasis on protected classes can also be overly reductive and fail to capture meaningful intersectionality; in order to receive legal protection, one must identify as a woman, or a black person, failing to capture the unique experience of black women, for instance.38 In fact, a recent systematic analysis of 93 stigmas in the general population showed that, on average, each individual reported approximately six stigmas,11 highlighting the important point that intersectional stigmatized identities may be the norm rather than the exception.

Interpersonal vs. Structural Stigma

Social science research has consistently established that stigma operates at individual, interpersonal, and structural levels and that each level can contribute to untoward social, academic, psychological, and health outcomes among the stigmatized.7, 39 Individual forms of stigma refers to the cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes in which individuals engage in response to stigma. These intrapersonal responses include identity concealment, or hiding aspects of your stigmatized status/condition/identity to avoid rejection and discrimination;40 self‐stigma, or the internalization of negative societal views about your group;41 and rejection sensitivity, or the tendency to anxiously expect, and readily perceive, that one will be rejected based on one's stigmatized status/identity/condition.42 In contrast, interpersonal stigma refers to prejudice and discrimination as expressed by one person toward another—that is, to interactional processes that occur between the stigmatized and the nonstigmatized. Interpersonal forms of stigma include not only intentional, overt actions, such as bias‐based hate crimes,43 but also unintentional, covert actions, like microaggressions.44

Structural stigma encompasses stigma processes that occur above the individual and interpersonal levels; it has been defined as “societal‐level conditions, cultural norms, and institutional policies that constrain the opportunities, resources, and well‐being of the stigmatized.”45 (p2) As is evident in this definition, laws and policies are one important component of structural stigma;14, 46 examples include marriage bans for gays and lesbians, differential sentencing for crack as opposed to powdered cocaine for racial and ethnic minorities, laws that allow special scrutiny of people “suspected” of being undocumented, and a lack of parity for mental illness treatment versus other medical care.16

As these definitions and examples illustrate, there can be some overlap in different forms of stigma. For example, employer discrimination can be either interpersonal or structural, depending on how it is measured in a particular study. If the measure captures an action that one employer takes against an employee (eg, fires her because of her race), this represents an example of interpersonal discrimination. If, instead, the measure captures an institutional policy or practice that promotes unequal treatment based on race, this would be an example of structural discrimination.

Despite the various forms that stigma might take, antidiscrimination laws typically address only interpersonal stigma.17, 47 Moreover, these laws prioritize intentional discrimination, failing to capture forms of bias at the structural level.48 Scholars have often acknowledged that disparate impact claims—that is, claims of unintentional discrimination—are better served in reaching structural discrimination than disparate treatment claims, which argue intentional discrimination, because one does not have to prove discriminatory intent.49 However, disparate impact claims are sometimes unavailable; for example, Title VI litigants cannot privately sue.34 And laws are often narrowly construed, highly fragmented, and arbitrary in their limits: one has to have been discriminated against in the “right” time, the “right” place, and by the “right” party (whatever the requirements of any specific antidiscrimination statute) in order for it to count as “unlawful” discrimination, and this often has little to do with how unfair, harmful, or blatant the discrimination was.50 A disabled person, for example, might be able to bring a suit if she has 20 coworkers, but if she has only 12 she is out of luck. Courts can make sure that laws are read as expansively as possible, but they can also play a role in limiting the scope of antidiscrimination laws. For instance, after a string of court cases read the ADA in narrow and restrictive ways, Congress had to pass the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 to ensure the law was interpreted by the courts as having the broad protections that Congress had originally intended. For many of these reasons, some scholars question whether the legal system can ever sufficiently tackle structural discrimination.51

The emphasis on the interpersonal in antidiscrimination law also overlooks individual forms of stigma, or how individuals internalize and respond to stigma. Many studies suggest that social isolation, psychological and behavioral responses to stigma (eg, coping behaviors), and the experience of stress from stigma can all have important effects on population health inequalities resulting from stigma.5 These processes that mitigate or exacerbate stigma are not easily reached by antidiscrimination law currently, as these processes involve how individuals cope with stigma, and not how stigma is enacted between parties.

Whether these criticisms reflect inherent or modifiable problems within the law is a critical issue to consider more, and one that we briefly discuss in our final section.

Limits of Antidiscrimination Law: Enforcement

Despite these weaknesses, antidiscrimination laws still cover some stigmatized groups in important domains. However, even when there are laws on the books, this does not mean that the rights in those laws are safeguarded in practice. Inadequate enforcement of existing laws presents an additional challenge to the use of law in reducing stigma‐based inequalities, either because it is too challenging for individuals to bring suits, or because the government fails to monitor and enforce people's rights.

Antidiscrimination challenges can typically be brought through several pathways: a private litigant can bring a lawsuit against the offending party (a private cause of action), or the government can investigate and bring suit either independently or in response to a complaint. Additionally, the government can create and enforce specific antidiscrimination laws that can lead to deterrence of certain conduct, regardless of whether a lawsuit is brought.

Unfortunately, individuals can face a variety of hurdles in fighting for their own rights in the courts. Some stigmatized individuals may have legitimate injuries but may not feel that they can or should file lawsuits. They may internalize stigma and believe that the discrimination is warranted or that they have no rights. And, in many cases, people who are injured do not bring legal claims even if they would be likely to succeed for a variety of cultural, social, and structural reasons.52, 53, 54 At the same time, some literature suggests that the existence of antidiscrimination law (even if people do not sue) can help people reshape their self‐image as rights‐bearers.55

Practically, litigants may be hamstrung by procedural requirements that are time‐intensive and burdensome; for example, many antidiscrimination statutes require the injured party to exhaust all administrative relief before suing. Moreover, litigation is prohibitively costly for many litigants and often litigants are seeking injunctions instead of monetary damages, so they (and their lawyers) may have little financial incentive to bring lawsuits.

Government enforcement is critical, yet administrations frequently choose to privilege some forms of antidiscrimination rights while ignoring or harming others, and to significantly reduce financing and staffing of various civil rights offices. Of course, without government enforcement of antidiscrimination laws, entities that are supposed to comply with these laws—like educational institutions, employers, and health care providers—may feel emboldened to offer fewer protections than are required of them by the law.

And, in some instances, government enforcement may well weaken the law rather than increase enforcement. Some scholars have critiqued the EEOC, which, in shifting legal claims from the courts to administrative proceedings, should make legal claims more affordable and easier to access. However, these scholars argue that the EEOC was underfunded and never capable of handling claims in a timely manner, acted as a useless roadblock that postponed litigants’ day in court,56 and ironically (given its mission) discriminated against certain groups such as individuals with mental illness.57, 58, 59 This is another example of how law and legal systems might sometimes generate or exacerbate stigma.

The government's handling of civil rights complaints is also fragmented. Laws are drafted to handle one stigma in one domain and different agencies enforce different antidiscrimination statutes; for example, health care complaints are handled by the Department of Health and Human Services, education complaints by the Department of Education, and employment claims by the EEOC. This approach is acceptable to address the health harms of a single stigma against a single group in a single domain. But, without coordination, it is difficult to comprehensively assess the enforcement of these laws at a population level for all forms of stigma.

In sum, we suggest that conceptual and enforcement challenges, taken collectively, currently limit the role of the law in mitigating stigma. However, as discussed in the next section, greater attention paid to addressing and overcoming these challenges may make change possible and may allow the law to be a better tool against stigma in the future.

Future Research Proposals

Our analysis has revealed several future directions for research and policy that are necessary to advance the field. In this section, we propose several concrete initiatives that we believe can address some of the key challenges of law in combating the health harms of stigma. We also raise additional topics that require more theoretical and empirical attention. We believe that the proposals we outline here should be addressed through an interdisciplinary lens that incorporates theories and analytic frameworks from the social sciences, law, ethics, and public policy, consistent with Burris's admonition that “the stigma research agenda thus demands greater integration of health, science, and the law.”14 (p531)

Initiating a New Population‐Level Surveillance System on Antidiscrimination Law and Enforcement

Our analysis suggests that conceptualization and enforcement issues may limit antidiscrimination law's potential impact in redressing stigma‐based harms. But, ultimately, gathering further evidence for this theory is difficult without a transparent, systematic way to demonstrate whether, and to what extent, the law reaches—in theory and in practice—the stigmatized groups for which it has been designed. There is currently no central mechanism by which government or private actors initiate and track surveillance of antidiscrimination laws and their enforcement. We argue that antidiscrimination law and its enforcement is an important piece of public health information that needs to be made available to the public and to researchers. We therefore propose a population‐level antidiscrimination data collection effort that longitudinally monitors the changing landscape of antidiscrimination laws as well as all government enforcement of these laws (including stigmatized groups, agencies involved, cost to government, outcome) and private litigation efforts related to antidiscrimination (including suits brought under specific laws and outcomes of those suits). The database should be expansive and should capture as many relevant laws and policies as feasible; this might include federal and state law, city ordinances, professional codes of ethics, and private entities’ policies, where relevant. The data should also encompass as many broad domains and stigmatized statuses as possible, to reflect the current state of the social science literature. The data repository could be modeled after other public health data collection efforts that make health determinants and outcomes available to researchers for free. Examples include the Policy Surveillance Program at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University (lawatlas.org), which has created a data repository for many laws that are relevant to public health (eg, housing, health services, food safety), as well as numerous annual health surveillance data sets that measure the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States, which are coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (eg, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System).

Figure 1 is a starting point, as it presents the laws covering primary statuses and domains that stigma impacts. The authors, through gathering this data, were able to demonstrate in specific ways how current federal antidiscrimination laws fall short of the social science literature on stigma in protected class and domain. However, a complete database would keep track of more domains, more statuses, and any changes in the law, for instance, recent court cases or regulatory reforms. A database would enable cross‐comparisons of longitudinal changes in antidiscrimination law and enforcement, along with the possibility to compare how these data points correlate with other changes in health outcome measures. As just one example, if the Trump administration and its agencies were to narrowly define gender as biological and immutable, researchers, policymakers, and others could study health outcomes of sexual and gender minorities before and after this change and draw inferences about how this political decision influenced population health.

The existence of antidiscrimination law can serve as a public statement of social values and can help to alleviate self‐stigma for some, even if they never file suit or make any legal claims.55 Such a database could be a tool used by activists and educators to help raise public awareness about legal rights and, through this, help to address some self‐stigma. Lastly, such a database could be used by policymakers, government agencies, and legal activists as a tool to identify important gaps and trends in antidiscrimination law and enforcement.

In proposing such a database, we recognize that there will be challenges. As in other data collection efforts involving powerful interest groups (eg, collection of reliable hate crime data and of gun sales), there can be pushback against the provision of transparent information. Additionally, the data repository would require frequent updates to keep up with the law's fluidity. To address some of these challenges, the database could leverage existing data that is collected by government or private entities, sometimes behind paywalls. For example, PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) catalogs federal litigation, beginning at the complaint stage, while state courts typically have their own individual websites. Additionally, some Office for Civil Rights (OCR) offices gather and report data. For instance, the US Department of Education runs the Civil Rights Data Collection, which gathers data from public educational institutions and schools to ensure compliance with antidiscrimination provisions. The EEOC engages in similar efforts with select employers. Assembling these disparate sources into a single data set, and adding to it, will enable population‐level study of antidiscrimination laws and enforcement.

Unfortunately, some data may be difficult to obtain without significant changes to the way our legal system is currently structured. Legislation may be necessary to mandate that certain entities make such data regularly available, similar to other public health reporting requirements. Additionally, a large percentage of discrimination suits settle or go to arbitration (often with privacy clauses), and it is difficult to measure how successful that litigant was without an approximation of the settlement and any concessions granted. More investigation would be required to determine whether some data could still be gathered—for instance, by removing any identifiable information. Some success has been demonstrated in the private sector; for example, Lex Machina evaluates employment discrimination cases for wins, losses, and settlements as a way for firms to predict winning cases and strategies. Again, however, this information is not publicly available, for free, to researchers. Similar efforts could be undertaken, with funding, to enable researchers to access this important public health information. The key is to begin to view this information as a matter of public health concern, meriting surveillance.

Considering a Centralized Government Agency

Another major challenge of addressing stigma at the population level through law is the lack of a central entity responsible for antidiscrimination enforcement. We believe that a coordinating agency that addresses the current balkanization in the implementation of antidiscrimination law may be necessary, but we are agnostic about how this might best be accomplished because existing options come with important limitations. One option would be to enhance the capabilities of an existing governmental agency, such as the US Commission on Civil Rights; but that requires congressional action and an administration that is not hostile to the enforcement of such laws. An alternative would be an independent nongovernmental organization, which could be formed more readily and liaise with relevant governmental agencies; however, this option lacks enforcement capabilities. We believe bold and creative new strategies are needed to tackle this significant barrier to effective enforcement of antidiscrimination law. While this would be a difficult task—far harder to achieve than a database—we pose this aspirational idea to promote dialogue and further study and because this may be a necessary step to fully achieve some of the enforcement issues we raised earlier. State and local governments may similarly consider whether balkanization is an issue and whether greater coordination is merited.

Rethinking the Purpose of Antidiscrimination Law

Perhaps the most stubborn problem is whether the law is truly designed to be a partner‐in‐arms in the battle over stigma and health and whether there is will on the part of lawmakers and others to make it so. There is no universal agreement on what antidiscrimination laws should achieve, but there is good support for the idea that antidiscrimination law should address stigma. Some theories of antidiscrimination law, such as anticlassification, propose only that the law root out discrimination that is plainly based on a person's membership in a class—for instance, a school should not be free to treat a child differently based on race.36 But most other theories of antidiscrimination law (say, antiessentialism or antisubordination) go further, having as their goal the rectifying of long‐standing historic subordination and harmful stereotyping and the recognition that labels and group distinctions are often social constructs.36 Some theories, including antibalkinization,37 even consider how to level the playing field for historically devalued persons without triggering group resentment by majority groups. These theories collectively suggest that antidiscrimination law goes beyond mere differential treatment and, instead, assumes as one of its goals these broader concerns of power, status loss, and subordination that are at the heart of stigma, especially structural forms.7 Thus far, however, antidiscrimination law as currently constructed reflects neither these theoretical legal critiques nor the empirical social science literature regarding how stigma at multiple levels—including the structural level—affects the distribution of life chances among the stigmatized.5, 16

Even if the law should reach stigma, it is hard to ignore a history in which law has fallen short or been used as a tool for disenfranchisement. Stigmatization may drive the law to be written, conceptualized, and enforced in ways that fail to adequately redress stigma‐induced harms. This paradox speaks to the importance of a multipronged approach to reducing stigma. Multiple strategies, and the power to enact them, are needed to address the motivations to stigmatize. This will in turn render legal approaches more effective in combating stigma and its negative consequences for population‐level health inequalities.

And, lastly, there is the question of how to make law better suited to tackle stigma. Much of this paper has emphasized the shortcomings of antidiscrimination law generally and, more specifically, the ways that law is too narrowly conceived of to reach some forms of stigma. One broad‐sweeping solution could be that antidiscrimination law move away from the protected‐class‐based framework and instead focus on universal rights and liberties that ought to be enjoyed by all.36, 60, 61

Yoshino suggests Lawrence v. Texas as a model;62 the Supreme Court articulated a right of consensual sex in one's homes to be free from government intrusion, not because the particular couple were two men being treated differently than a heterosexual couple (though they were), but because all couples should enjoy that right. These arguments have been made for different legal and social reasons; what our analysis adds to this debate is the incorporation of evidence from the social science literature on stigma. The merits and consequences of a pivot to a liberty‐based legal framework, along with the practical questions of how it can and should be enacted, require greater attention in federal, state, and local contexts. A liberty‐based framework will likely require discussions around which liberty interests require universal protection, but as the stigma literature suggests, this may be a more realistic, comprehensive, and equitable approach when compared to deciphering which of the myriad stigmatized groups merit legal protections and in which domains. At the same time, scholars acknowledge that legal protections that name certain groups as meritorious of protection is a useful tool in tackling self‐stigma.55 This is a serious trade‐off that must be considered in a decision on whether to adopt a liberty‐based system.

Convening an Interdisciplinary Working Group to Explore Boundaries of Law

Ultimately, there may be ways in which law is simply not an effective tool or in which it is impractical or impossible to expand the law as needed to effectively address stigma, as we suggest throughout this paper. Therefore, we propose the convening of an interdisciplinary working group, coordinated by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), that brings together lawyers, social scientists, public health experts, and other relevant entities to consider the outer boundaries with respect to the law as a remedy for addressing stigma‐based health harms. A working group specifically convened by the NAS offers several unique strengths: the Academy is independent from the government; it is nonprofit and nonadvocacy; it is able to draw on leading experts across relevant stakeholder groups; and its reports are respected, given their high level of rigor, transparency, and independence from external influence. Such a group could broadly consider the extent of stigma in society according to researchers and the various legal tools available, while identifying areas where expansion of the law is feasible and areas where stigma is better addressed through other mechanisms. This work, which would hopefully culminate in a full consensus report, may be in concert with the efforts proposed in this paper to consider ways in which law should be reshaped theoretically to better capture stigma.

Conclusions

Antidiscrimination law, as currently written, does not always reach the groups who are stigmatized or the domains in which they are stigmatized. Antidiscrimination law as currently conceptualized, including the narrow focus on protected groups and on interpersonal forms of discrimination, renders the law ineffective in reaching many forms of stigma for many groups. We have argued that antidiscrimination law must be better tailored based on the evidence of who is affected by stigma, as well as where and how stigma occurs, or it will be a poor tool for remedying stigma, regardless of its level of enforcement. We have suggested some immediate strategies—including the development of a new surveillance system for antidiscrimination law and its enforcement—but further interdisciplinary research is also needed to identify the ways in which law can be crafted into a better tool for redressing the health harms of stigma and to delimit clearer boundaries for when law is (and is not) the appropriate remedy for these stigma‐induced inequities.

We are clear‐eyed about the challenges of implementing our recommendations. Some challenges, such as reporting procedures, are largely logistical in nature, and we believe these can be overcome. Other recommendations, however, face greater hurdles, and these result from a core aspect of stigma—namely, that stigmatizers have the social, political, and economic power to achieve certain ends (eg, exploitation/dominance, enforcement of social norms),8 precisely because they have constructed the law to ensure their objectives are achieved.

Funding/Support

None.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Both authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No conflicts were reported.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Ronald Bayer and Kristen Underhill for helpful comments on an earlier draft and the West Virginia University College of Law and the Hodges Research Fund for research support.

References

- 1. Discrimination pervades daily life, affects health across groups in the U.S., NPR/Harvard/RWJF poll shows. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation website. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2017/10/discrimination-pervades-daily-life-affects-health-across-groups.html. Published October 24, 2017. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- 2. Franciscan Alliance, Inc. v. Burwell , 7:16‐cv‐00108 District Court (ND Tex 2016).

- 3. Zarda v. Altitude Express, Inc., No. 15–3775 (2d Cir 2018).

- 4. Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission , 584 US—(2018).

- 5. Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813‐821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363‐385. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Phelan J, Link B, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: one animal or two? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:358‐367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Major B, O'Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:393‐421. 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pescosolido BA, Martin JK. The stigma complex. Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41:87‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Wang K, et al. The burden of stigma on health and well‐being: a taxonomy of concealment, course, disruptiveness, aesthetics, origin, and peril across 93 stigmas. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2017;44(4):451‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528‐529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burris S. Disease stigma in US public health law. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30(2):179‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burris S. Stigma and the law. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):529‐531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC. Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):481‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Link B, Hatzenbuehler ML. Stigma as an unrecognized determinant of population health: research and policy implications. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41(4):653‐673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bagenstos SR. The structural turn and the limits of antidiscrimination law. Calif Law Rev. 2006;94(1):1‐47. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abrams P. The bad mother: stigma, abortion and surrogacy. J Law Med Ethics. 2015;43(2):179‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shame Wiley LF., blame, and the emerging law of obesity control. U C D L Rev. 2013;47:121‐188. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levy BL, Levy DL. When love meets hate: the relationship between state policies on gay and lesbian rights and hate crime incidence. Soc Sci Res. 2017;61(1):142‐159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krieger N, Chen JT, Coull B, Waterman PD, Beckfield J. The unique impact of abolition of Jim Crow laws on reducing inequities in infant death rates and implications for choice of comparison groups in analyzing societal determinants of health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2234‐2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, Hatzenbuehler ML, Galea S. State laws permitting denial of services to same‐sex couples and mental distress among sexual minority adults: a difference‐in‐difference‐in‐differences analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:671‐677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Law Cohen D., social policy, and violence: the impact of regional cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(5):961‐978. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luís S, Palma‐Oliveira J. Public policy and social norms: the case of a nationwide smoking ban among college students. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2016;22(1):22‐30. 10.1037/law0000064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tankard M, Paluck EL. The effect of a Supreme Court decision regarding gay marriage social norms and personal attitudes. Psychol Sci. 2017;28(9):1334‐1344. 10.1177/0956797617709594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kreitzer RJ, Hamilton AJ, Tolbert CJ. Does policy adoption change opinions on minority rights? The effects of legalizing same‐sex marriage. Polit Res Q. 2014;67(4):795‐808. 10.1177/1065912914540483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pacheco J. Attitudinal policy feedback and public opinion: the impact of smoking bans on attitudes towards smokers, secondhand smoke, and antismoking policies. Public Opin Q. 2013;77(3):714‐734. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donovan T, Tolbert C. Do popular votes on rights create animosity toward minorities? Polit Res Q. 2013;66(4):910‐922. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sutton JS. 51 Imperfect Solutions: States and the Making of American Constitutional Law. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins , 490 US 228 (1989).

- 31. State public accommodation laws. National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) website. http://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/state-public-accommodation-laws.aspx. Published July 13, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- 32. Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 US 624 (1998).

- 33. 42 US Code §12114(a), Illegal use of drugs and alcohol.

- 34. Pomeranz JL, Puhl RM. New developments in the law for obesity discrimination protection. Obesity. 2013;21(3):469‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eskridge W. Some effects of identity‐based social movements on constitutional law in the twentieth century. U Penn L Rev. 2001;150:419‐525. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clarke J. Against immutability. Yale L J. 2015;125:1‐102. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Balkin JM, Siegel RB. The American civil rights tradition: anticlassification or antisubordination? U Miami L Rev. 2003;58:9‐33. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989] . New York: Routledge; 2018:57‐80. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 2016;71(8):742‐751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: a cognitive‐affective‐behavioral model. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(2):328‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Corrigan PW, Sokol KA, Rüsch N. The impact of self‐stigma and mutual help programs on the quality of life of people with serious mental illnesses. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mendoza‐Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, Pietrzak J. Sensitivity to status‐based rejection: implications for African American students’ college experience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(4):896‐918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Herek GM. Hate crimes and stigma‐related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(1):54‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hatzenbuehler ML, Link BG. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Heyrman ML, et al. Structural stigma in state legislation. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(5):557‐563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rich SM. Against prejudice. Geo Wash L Rev. 2011;80:1‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Goldberg SB. Discrimination by comparison. Yale Law J. 2010;120:728‐812. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Burris S. Foreword: envisioning health disparities. Am J Law Med. 2003;29:151‐158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Satz A. Overcoming fragmentation in disability and health law. Emory L J. 2010;60:277, 289. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sturm S. Second generation employment discrimination: a structural approach. Colum L Rev. 2001;101(3):458‐568. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Felstiner WLF, Abel RL, Sarat A. The emergence and transformation of disputes: naming, blaming, and claiming. Law Soc Rev. 1980;15(3/4):631‐654. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vidmar N, Kritzer HM, Bogart WA. The aftermath of injury: cultural factors in compensation seeking in Canada and the United States. Law Soc Rev. 1991;25:499‐543. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moss K, Ullman M, Swanson JW, Ranney LM, Burris S. Prevalence and outcomes of ADA employment discrimination claims in the federal courts. Mental & Physical Disability Law Reporter. 2005;39:303‐311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Engel DM, Munger FW. Law and Identity in the Life Stories of Persons With Disabilities. Chicago, IL: Univeristy of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Moss K, Burris S, Ullman MD, Johnsen M, Swanson JW. Unfunded mandate: an empirical study of the implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Kansas L Rev. 2001;50(1). [Google Scholar]

- 57. Moss K, Swanson J, Ullman M, Burris S. Mediation of employment discrimination disputes involving persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(8):988‐994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Moss K, Ullman M, Starrett BE, Burris S, Johnsen MC. Outcomes of employment discrimination charges filed under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(8):1028‐1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Burris S, Swanson JW, Moss K, Ullman MD, Ranney LM. Justice disparities: does the ADA enforcement system treat people with psychiatric disabilities fairly? Maryland L Rev. 2007;66. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fineman M. The vulnerable subject and the responsive state. Emory L J. 2010;60:251‐275. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yoshino K. Covering: The Hidden Assault on Our Civil Rights. New York: Random House; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lawrence v. Texas, 539 US 558 (2003).