We report the genome sequence of Brucella abortus biovar 3 strain BAU21/S4023, isolated from a dairy cow that suffered an abortion in Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. The genome sequence length is 3,244,234 bp with a 57.2% GC content, 3,147 coding DNA sequences (CDSs), 51 tRNAs, 1 transfer messenger RNA (tmRNA), and 3 rRNA genes.

ABSTRACT

We report the genome sequence of Brucella abortus biovar 3 strain BAU21/S4023, isolated from a dairy cow that suffered an abortion in Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. The genome sequence length is 3,244,234 bp with a 57.2% GC content, 3,147 coding DNA sequences (CDSs), 51 tRNAs, 1 transfer messenger RNA (tmRNA), and 3 rRNA genes.

ANNOUNCEMENT

Since its first description in 1906 (1), Brucella abortus remains one of the most important zoonotic and endemic diseases in several parts of the world (2). Brucella species are a group of aerobic, intracellular, small, non-spore-forming, nonencapsulated, and nonmotile Gram-negative coccobacilli (2, 3). They infect all livestock—avian, bovine, caprine, camelid, equine, ovine, and porcine (4, 5) and also wild animals (6, 7) and marine mammals (8). Human brucellosis causes a significant global public health and economic burden (9). Some species are subdivided into biovars; i.e., B. abortus species include eight biovars (1 to 7 and 9) (3). B. abortus causes infection predominantly in cattle, leading to substantial economic losses in dairy animals through stillbirths and decreased milk production (10). In Bangladesh, B. abortus infection is endemic in livestock and was reported to cause brucellosis in humans (11–13).

The genome sequence of B. abortus isolates from Bangladesh is essential because of its potential animal and public health impacts in this region. It allows in-depth analysis of genomic structure and will help us to understand its virulence, pathogenesis, host specificity, biotyping difference, and phylogenetic relationships and help to identify potential targets for the development of vaccines and diagnostics to prevent and control brucellosis.

Here, we report the first whole-genome sequence of B. abortus biovar 3 strain BAU21/S4023, isolated from a crossbred dairy cow (Bos taurus) in Bangladesh in March 2017. The Brucella strain was isolated from cow number 4023 (which suffered an abortion on a dairy farm in Savar, Bangladesh) by the streaking of a uterine discharge sample onto Brucella selective agar (HiMedia, India), which was then incubated at 37°C for 7 days in the presence of 5% CO2. Conventional bacteriological methods, classical biotyping, and enhanced AMOS-ERY PCR analysis confirmed the isolate as B. abortus biovar 3 (14, 15).

For genome sequencing, DNA was extracted from a single colony of strain BAU21/S4023 using a GeneJET genomic DNA purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). DNA concentrations were quantitated using the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer for a double-stranded DNA high-sensitivity assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA). Genomic libraries were constructed using a NEBNext Ultra DNA library prep kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). The library size selection was 350 bp, and a paired-end (PE) sequencing strategy (2 × 150 bp) was performed by Apical Scientific (Selangor, Malaysia) using a HiSeq 4000 instrument (Illumina, Inc.). A total of 1,294 Mb (or ∼1.3 Gb) raw data reads were generated, and a total of 1.191 Mb (or ∼1.2 Gb) clean reads were obtained using Perl script to trim off Illumina adaptor sequences and remove low-quality reads. A total of 3.97 million reads passed the quality filter; reads averaged 150 bp in length and showed an average quality score above Q30 in more than 90% of the bases. Sequences were assembled using SPAdes version 3.11.0 (16) into 24 contigs at least 200 nucleotides (nt) long and a coverage of >10×, for a total of 3,244,234 bp with a GC content of 57.2%, an N50 value of 367,095, and an L50 value of 4 and containing 3,147 coding DNA sequences (CDSs), 51 tRNAs, 1 transfer messenger RNA (tmRNA), and 3 rRNA genes as identified by annotation using Prokka version 1.13 with default settings (17).

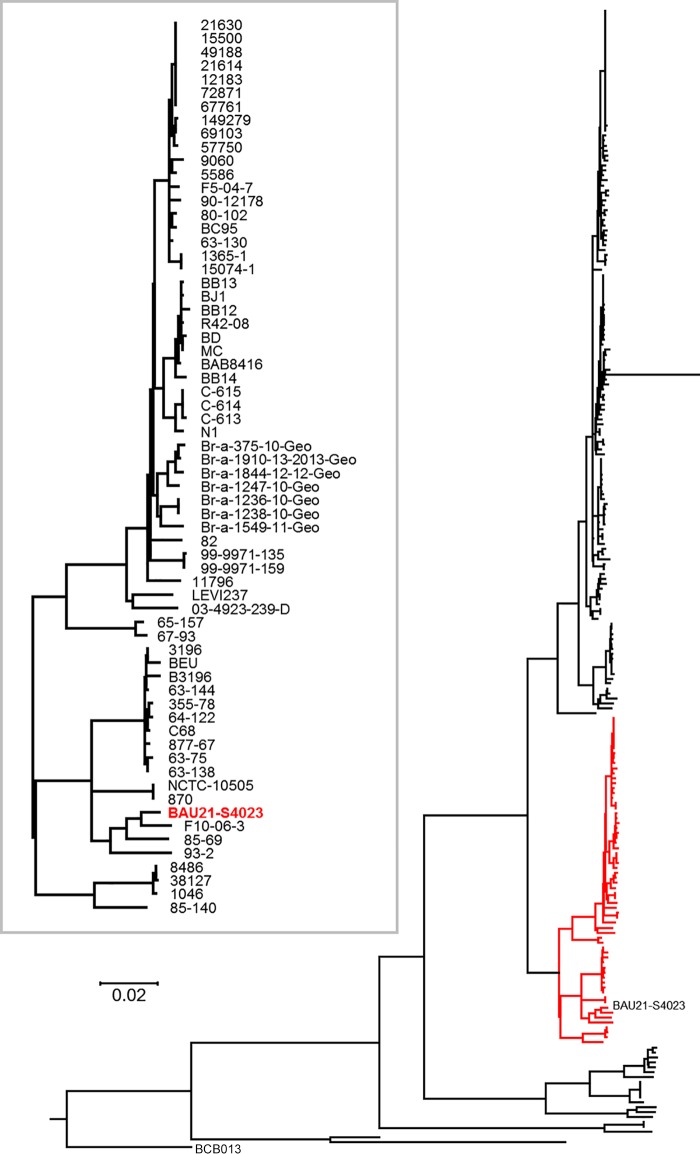

A core genome single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) tree of 228 genomes from GenBank was constructed to determine the relationship between the BAU21/S4023 strain and other available B. abortus isolates. B. abortus genomes were downloaded from the NCBI genome database using ncbi-genome-download version 0.2.9 (https://github.com/kblin/ncbi-genome-download), and core genome SNPs were identified and used for the construction of a phylogenetic tree using ParSNP version 1.2 (18) with the settings “-a 13” and “-x” as described previously (19). The genome of BAU21/S4023 was clustered closely with reference B. abortus genomes such as NCTC10505 (biovar 6), 870 (biovar 6), and C68 (biovar 9) (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree of 229 B. abortus genome sequences based on core genome single nucleotide polymorphisms as identified using ParSNP. The position of the B. abortus BAU21/S4023 genome sequence is indicated in the tree, which was rooted with the genome sequence of B. abortus BCB013. The inset shows the part of the tree where the B. abortus BAU21/S4023 genome sequence clusters, with the closest relatives named.

Data availability.

This whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the BioProject number PRJNA529883 and accession number SRJJ00000000. The version described in this paper is version SRJJ02000000. The sequences have been submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number SRX5762378.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Bangladesh Academy of Sciences and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (BAS-USDA), project number LS-02, for financial support of the study.

We thank Stephen M. Boyle from Virginia Tech for editorial comments on the article and Rebecca Wattam from the University of Virginia for her comments. We thank Massimiliano S. Tagliamonte from the Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, and Emerging Pathogen Institute, University of Florida (Gainesville, FL, USA), for his assistance and Francy L. Crosby from the Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida (Gainesville, FL, USA), for her support.

M.E.E.Z. prepared the manuscript; M.S.I., M.T.R., M.A.I., M.M.K., and S.S. conducted diagnostic tests; A.H.M.V.V. and S.T. performed phylogenetic analysis; and M.E.E.Z., A.H.M.V.V., M.A.I., M.T.R., and A.N. reviewed the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bang B. 1906. Infectious abortion in cattle. J Comp Pathol Ther 19:191–202. doi: 10.1016/S0368-1742(06)80043-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen S, Palmer M. 2014. Advancement of knowledge of Brucella over the past 50 years. Vet Pathol 51:1076–1089. doi: 10.1177/0300985814540545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garin-Bastuji B, Mick V, Le Carrou G, Allix S, Perrett LL, Dawson CE, Groussaud P, Stubberfield EJ, Koylass M, Whatmore AM. 2014. Examination of taxonomic uncertainties surrounding Brucella abortus bv. 7 by phenotypic and molecular approaches. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1570–1579. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03755-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gwida M, El-Gohary A, Melzer F, Khan I, Rösler U, Neubauer H. 2012. Brucellosis in camels. Res Vet Sci 92:351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pappas G. 2010. The changing Brucella ecology: novel reservoirs, new threats. Int J Antimicrob Agents 36:S8–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlabritz‐Loutsevitch NE, Whatmore AM, Quance CR, Koylass MS, Cummins LB, Dick EJ Jr, Snider CL, Cappelli D, Ebersole JL, Nathanielsz PW, Hubbard GB. 2009. A novel Brucella isolate in association with two cases of stillbirth in non‐human primates—first report. J Med Primatol 38:70–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2008.00314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiller RV, Gee JE, Frace MA, Taylor TK, Setubal JC, Hoffmaster AR, De BK. 2010. Characterization of novel Brucella strains originating from wild native rodent species in North Queensland, Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5837–5845. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00620-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster G, Osterman BS, Godfroid J, Jacques I, Cloeckaert A. 2007. Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 57:2688–2693. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean AS, Crump L, Greter H, Schelling E, Zinsstag J. 2012. Global burden of human brucellosis: a systematic review of disease frequency. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deka RP, Magnusson U, Grace D, Lindahl J. 2018. Bovine brucellosis: prevalence, risk factors, economic cost and control options with particular reference to India—a review. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 8:1556548. doi: 10.1080/20008686.2018.1556548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Islam MA, Khatun MM, Werre SR, Sriranganathan N, Boyle SM. 2013. A review of Brucella seroprevalence among humans and animals in Bangladesh with special emphasis on epidemiology, risk factors and control opportunities. Vet Microbiol 166:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahman AA, Saegerman C, Berkvens D, Melzer F, Neubauer H, Fretin D, Abatih E, Dhand N, Ward M. 2017. Brucella abortus is prevalent in both humans and animals in Bangladesh. Zoonoses Public Health 64:394–399. doi: 10.1111/zph.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam MS, Islam MA, Khatun MM, Saha S, Basir MS, Hasan M-M. 2018. Molecular detection of Brucella spp. from milk of seronegative cows from some selected area in Bangladesh. J Pathog 2018:9378976. doi: 10.1155/2018/9378976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alton G, Jones L, Angus R, Verger J. 1988. Bacteriological methods, p 13–61. In Techniques for the brucellosis laboratory. Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique Publications, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ocampo-Sosa AA, Agüero-Balbín J, García-Lobo JM. 2005. Development of a new PCR assay to identify Brucella abortus biovars 5, 6 and 9 and the new subgroup 3b of biovar 3. Vet Microbiol 110:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455-77. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. 2014. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol 15:524. doi: 10.1186/PREACCEPT-2573980311437212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pornsukarom S, van Vliet AH, Thakur S. 2018. Whole genome sequencing analysis of multiple Salmonella serovars provides insights into phylogenetic relatedness, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence markers across humans, food animals and agriculture environmental sources. BMC Genomics 19:801. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the BioProject number PRJNA529883 and accession number SRJJ00000000. The version described in this paper is version SRJJ02000000. The sequences have been submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number SRX5762378.