SUMMARY

Preterm birth (PTB) is a syndrome with many origins. Among them, infection or inflammation are major risk factors for PTB; however, local defense mechanisms to mount anti-inflammatory responses against inflammation-induced PTB are poorly understood. Here, we show that endothelial TLR4 in the decidual bed is critical for sensing inflammation during pregnancy because mice with endothelial Tlr4 deletion are resistant to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced PTB. Under inflammatory conditions, IL-6 is readily expressed in decidual endothelial cells with signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) phosphorylation in perivascular stromal cells, which then regulates expression of anti-inflammatory IL-10. Our observation that administration of an IL-10 neutralizing antibody predisposing mice to PTB shows IL-10’s anti-inflammatory role to prevent PTB. We show that the integration of endothelial and perivascular stromal signaling can determine pregnancy outcomes. These findings highlight a role for endothelial TLR4 in inflammation-induced PTB and may offer a potential therapeutic target to prevent PTB.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Deng et al. show a balance between inflammation and anti-inflammation involving endothelial and decidual cells in pregnancy. Tipping this balance toward inflammation contributes to preterm birth. A mechanism to preserve homeostatic balance in pregnancy under inflammation is mediated by a cross-talk between endothelial and perivascular stromal cells.

INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth (PTB) is a leading cause of child mortality and morbidity and often incurs life-long clinical and psychological challenges for the survivors (Moster et al., 2008). Many risk factors, including genetic predisposition, bacterial infection or inflammation, maternal aging, hormonal imbalances, and environmental stresses, contribute toward this complex pathology (Goldenberg et al., 2008; Romero et al., 2014). PTB can result from both systemic and local inflammation in the reproductive tract and/or feto-placental unit (Elovitz and Mrinalini, 2004). The mechanism underlying PTB remains intangible, especially in humans due to logistical and ethical difficulties in accessing meaningful samples. Suitable animal models to recapitulate the human conditions are alternative viable options. Genetic and/or experimentally manipulated mouse models predisposed to PTB can mimic certain aspects of PTB in humans (Cha et al., 2013). In this context, mouse models can provide the advantage of studying gene-environment influences on PTB in a defined set of experimental and dietary conditions as opposed to human tissue analyses obtained from placentas under diverse settings. Genetic mouse models can also offer opportunities to explore the interplay between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways in PTB. The availability of a sufficient number of placentas from diverse groups with different ethnic backgrounds with different food habits, living conditions, and environment may be limiting factors to provide meaningful results. The scenario is more challenging for the socioeconomically depressed population groups, which often show higher rate of PTB. Because PTB is a disorder with many origins (Romero et al., 2014), studies in both animal models and humans will provide more meaningful results that could be relevant to humans and other species.

Both the maternal decidua and feto-placental unit are thought to participate in PTB in response to infection or inflammation. However, whether causes of PTB originate from the decidua, placenta, and/or fetus has not been clearly distinguished. The maternal decidua serves as a “signaling hub” that coordinates interactions between the mother and feto-placental unit (Moffett and Loke, 2006). Effective reciprocal cross-talk between the decidua and feto-placental unit involving genetics, epigenetic modification, and transcription factors in combination with morphogens, cytokines, and signaling molecules creates a favorable milieu to support fetal growth and development and successful completion of pregnancy (Romero et al., 2014; Rubens et al., 2014). There is increasing interest in the decidua’s role in orchestrating the homeostatic balance between the mother and fetus, and studies suggest that the decidua is a critical regulator of birth timing and pregnancy well-being (Cha et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2016; Hirota et al., 2011; Hirota et al., 2010).

LPS, a gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide, is a leading cause of inflammation through increased production of cytokines and chemokines. LPS primarily executes its function by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (Miller et al., 2005). Until now, the mechanism by which TLR4-induced inflammation induces PTB has largely been descriptive. There are reports that decidual macrophages and neutrophils express TLR4 and may play a role in inflammation-induced PTB (Kadam et al., 2017; Robertson et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018); whether other TLR4-expressing cells are involved in inflammation-induced PTB remains unknown. Using genetic mouse models and breeding strategies, we sought to dissect the role of maternal decidua apart from the fetal-placental entity in response to systemic LPS injection. The uterus is comprised of heterogeneous tissues and cell types, and it is not known whether TLR4 expression and function are tissue- or cell-specific. Here, we explored the site of TLR4-mediated function in the uterus.

Using genetic and molecular approaches, we show that the decidua is a major site of expression of TLR4, which is sensitive to LPS exposure and release of cytokines. Further investigation found that decidual endothelial TLR4 is primarily responsible for rapid induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines if exposed to systemic LPS administration. This inflammatory insult initiates cross-talk between the decidual endothelial and perivascular stromal cells to mount a counter, anti-inflammatory response. Using conditional deletion of Tlr4 in deciduae by a Pgr-Cre driver, we observed that dams with a loss of decidual Tlr4 have reduced litter size and increased fetal resorption and they are highly sensitive to PTB by an ultra-low dose of LPS. We found that Il6 is induced in endothelial cells by LPS and associated with activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pStat3) in perivascular stromal cells; Stat3 activation is known to regulate Il10 expression. Intriguingly, the deletion of endothelial Tlr4 by a highly specific Tie2-Cre driver (Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f) shows resistance to even a high dose of LPS (40 mg/mouse) to PTB in these mice; this dose induces PTB in 100% of Tlr4f/f females. There is evidence that interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces anti-inflammatory IL-10 expression through pStat3 (Saraiva and O’Garra, 2010). Indeed, administration of IL-10-neutralizing antibodies predisposes mice to PTB if exposed to a very low dose of LPS. Collectively, our results show tissue-specific interactions and responses to inflammation to protect pregnancy against inflammatory insults. This study elucidates a role for endothelial TLR4 in calibrating proinflammatory versus anti-inflammatory responses in the decidua to determine the fate of pregnancy outcomes and inflammation-induced PTB in the context of LPS exposure and genetic predisposition.

RESULTS

Differential TLR4 Expression in the Decidua and Placenta

The uterus is comprised of heterogeneous tissue and cell types. LPS primarily executes its function by TLR4, leading to increased release of cytokines (Miller et al., 2005). It is not known if TLR4 function is tissue or cell type specific. TLRs belong to a large family, and our RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data in isolated mouse epithelial and stromal cells show that Tlr4 expression is highest among other members of the family in stromal cells (Figure 1A). More interestingly, Tlr4 expression is much higher in day 16 deciduae than other organs, such as the liver, spleen, lung, ovary, and placenta (Figure 1B). The lower Il10 expression in the placenta also suggests that the decidua is more active in anti-inflammatory responses (Figure S1A). As recently reported (Nancy et al., 2018), RNA-seq data in purified stromal cells on days 8 and 16 of pregnancy show highest Tlr4 expression in deciduae, supporting our results and suggesting a potential role of TLR4 in the decidua (Figures S1B and S1C). Our in situ hybridization (ISH) results show that the expression of TLR4 is highly localized in day 16 deciduae with much lower expression in the placenta (Figure 1C), suggesting that the decidua is a potential site that modulates the balance between inflammation and anti-inflammation.

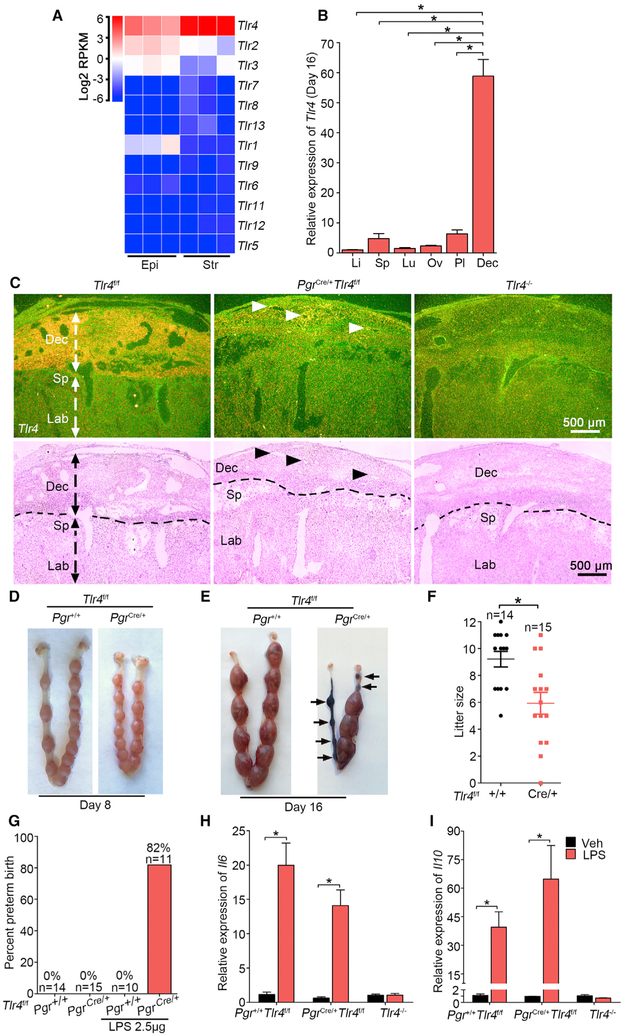

Figure 1. TLR4 Is Beneficial during Normal Pregnancy.

(A) Heatmap of RNA-seq analysis of Tlr mRNAs (log2 RPKM) in separated epithelial (Epi) and stromal cells (Str) from day 4 pregnant uteri (n = 3). RPKM, reads per kilobase per million.

(B) Relative Tlr4 expression levels in various organs in day 16 pregnant Tlr4f/f mice by qPCR. rpL7 was used as internal controls. Li, liver; Sp, spleen; Lu, lung; Ov, ovary; Pl, placenta; Dec, decidua; n = 4, *p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

(C) Dark-field and bright-field images of in situ hybridization for Tlr4 in Tlr4f/f, PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f, and Tlr4 genomic knockout (Tlr4−/−) mice. Arrow heads indicate remaining Tlr4 in PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice. Dotted lines demarcate the interface between maternal decidua and spongiotrophoblast. Dec, decidua; Sp, spongiotrophoblast; Lb, labyrinth. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(D and E) Days 8 (D) and 16 (E) implantation sites in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice. Arrows indicate resorption sites.

(F) Live litter size in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice. n, animal number in each group, *p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

(G) The ratio of preterm birth to total number of pups per gestation in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice with or without exposure to a low dose LPS (2.5 μg/mouse). n indicates the number of total mice examined in each group.

(H and I) qPCR of Il6 (H) and Il10 (I) mRNA levels in Tlr4f/f, PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f, and Tlr4−/− mice after 1 h of LPS treatment. *p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4).

See also Figure S1.

The above results prompted us to explore if TLR4 expression exhibits a similar pattern in humans. Indeed, TLR4 expression is highest among the family members in endometrial biopsies obtained from 20 healthy fertile women in the mid-secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, i.e., 8 days after luteinizing hormone peak (LH+8) (Figure S1D) (Altmäe et al., 2017). Another recent study that used single-cell RNA-seq analyses of first trimester deciduae and placentas shows that TLR4 expression is much higher in decidual stromal cells, decidual fibroblasts, and decidual vascular endothelial cells than those in placental cells (Figure S1E) (Suryawanshi et al., 2018). Higher expression of TLR4 in the human endometrium compared with other members is also seen in apparently normal patients in the TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) database (Figure S1F). Taken together, these results suggest that TLR4 in human decidual cells may respond to inflammation/infection similar to that noted in mice.

Role of TLR4 in Decidual Stromal Cells versus Decidual Endothelial Cells

These results led us to explore the site of TLR4-mediated function in the pregnant mouse uterus. Our previous study showed that genetically predisposed mice are extremely sensitive to ultra-pure TLR4-specific LPS to induce PTB (Cha et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2016). However, the homeostatic balance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses remains unknown. Because progesterone receptors are expressed in all major uterine cell types, we generated conditional Tlr4 mutant mice using Pgr-Cre driver (PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f) to investigate the physiological significance of TLR4 in the decidua (Figures 1C and S2A–S2C). Increased incidence of embryo resorption is observed in some mothers on day 16 but not apparent on day 8, along with decreased live litter sizes, indicates an important role of TLR4 during pregnancy (Figures 1D–1F). We speculated that mice with decidual deletion of Tlr4 should be resistant to LPS, similar to that observed in Tlr4 systematic knockout mice (Tlr4−/−) (Wahid et al., 2015). Unexpectedly, these PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice show exquisite sensitivity to PTB even upon an exposure to a low dose of LPS; LPS at 2.5 μg/mouse widely induces PTB (82%) with 92% dead pups. This low dose does not elicit adverse effects in Tlr4f/f pregnant mice (Figures 1G and S2D). One may argue that increased sensitivity of PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice is due to compromised TLR4 activity in resident leucocytes. However, co-staining of CD45, dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA)-lectin (natural killer [NK] cells), F4/80, Ly6G, and CD4 with PR in day 16 deciduae shows no overlap, excluding the possibility of deletion of TLR4 by the Pgr-Cre driver in decidual leucocyte populations (Figure S2E). Non-uterine tissues, such as spleen and liver, do not show specific PR staining (Figure S3). Using T cell-specific deletion of PR and glucocorticoid receptor (GR), it was shown that P4-induced T cell death is mediated by GR but not PR (Hierweger et al., 2019). In a recent study, single-cell analysis of human decidual cells in the first trimester shows that PR expression is very low to undetectable in NK cells, dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes, macrophages, and T cells as opposed to a significant presence of GR expression in these cell types. PR is primarily expressed in stromal cells (Vento-Tormo et al., 2018).

IL-6 is considered important for both LPS-induced PTB and normal delivery because the loss of Il6 shows delayed parturition and resists LPS-triggered PTB (Robertson et al., 2010). To investigate responses of LPS over time, Tlr4f/f mice were treated with LPS (2.5 μg) for 1, 3, and 6 hours. Both Il6 and Il10 were rapidly induced at 1 hour followed by their gradual downregulation. Cox2 was also induced at 1 hour with further increases at 3 and 6 hours (Figures S4A–S4C). Co-staining of CD31 and Cox2 presents evidence that Cox2 is induced in the endothelial cells (Figure S4D). The finding of rapid induction of Il6 and Il10 in day 16 decidua by LPS led us to analyze the expression of these cytokines in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice. Surprisingly, the expressions of Il6 and Il10 are significantly induced in the decidua by LPS in both Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice with no induction of these cytokines in Tlr4 systematic knockout mice (Figures 1H and 1I).

Cross-Talk between Endothelial Cells and Perivascular Stromal Cells

To further evaluate LPS-induced signaling pathways, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) and pStat3, critical mediators of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses, respectively, in the context of cell types and experimental conditions, were investigated after LPS injection. Western blotting analysis shows that induction of pStat3 by LPS in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice is comparable with no pStat3 induction in TLR4 systemic knockout mice (Figures 2A and 2B). Our ISH results also show that Il6 and Cox2 are induced in endothelial cells of PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f deciduae after LPS treatment, similar to that of Tlr4f/f mice on day 16 (Figure 2C). Immunofluorescence (IF) as well as results of isolated cytoplasm and nuclei reveal perivascular localization of pStat3 and nuclear translocation of NF-kB in endothelial cells in PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f deciduae, which are similar to Tlr4f/f mice after LPS exposure (Figures 2D–2F). The localization of pStat3 in the decidual cells and CD31 in endothelial cells (Figures 2D, S4E, and S4F) indicates a cross-talk between perivascular stromal cells and endothelial cells.

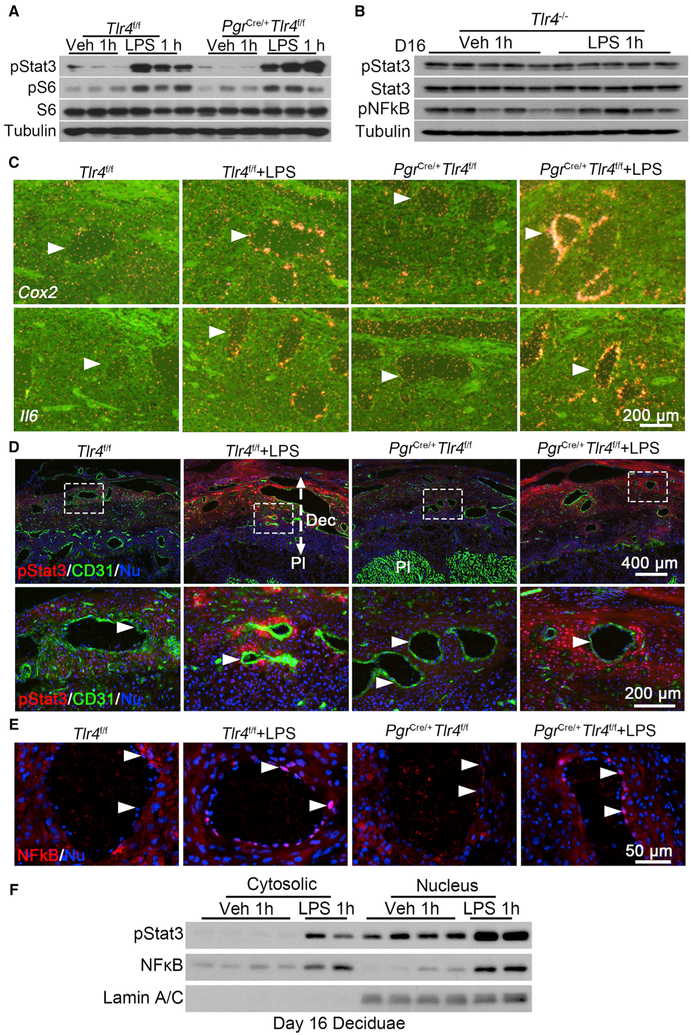

Figure 2. Interactions between Endothelial and Perivascular Stromal Cells in the Decidual Bed of PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f Mice.

(A) Western blotting of pStat3 and pS6 levels in day 16 uteri of Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f dams exposed to LPS (2.5 μg/mouse), n = 3.

(B) Western blotting results of pStat3, Stat3, and pNFkB levels in day 16 deciduae after LPS treatment for 1 hour in Tlr4−/− mice, n = 5.

(C) In situ hybridization for Cox2 and Il6 mRNAs in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice after exposure to LPS for 1 hour. Arrowheads indicated endothelial cells. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(D) Immunofluorescence staining of pStat3 (red) and CD31 (green) in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice after exposure to LPS for 1 hour. Scale bar of upper panels, 400 μm. Bottom panels show images at higher magnification of those within the demarcated rectangles in the upper panels. Dec, decidua; Pl, placenta. Arrowheads indicate endothelial cells. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(E) Immunostaining showing nuclear NF-kB (red) in Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice after exposure to LPS for 1 hour. Arrowheads indicate endothelial cells. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(F) Western blotting for pStat3 and NF-kB in cytosolic and nuclear fractions of day 16 deciduae after 1 h of vehicle or LPS treatment in Tlr4f/f females. Lamin AC was used as nuclear internal control.

See also Figures S2, S3, and S4.

Endothelial-Specific Deletion of Tlr4 Protects against LPS-Induced PTB

Undiminished TLR4 response in PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice suggested another site of activation of TLR4 mediates its response to LPS. Induction of Il6 and Cox2 in endothelial cells led us to speculate that decidual endothelial TLR4 might contribute to this disparity. To explore if endothelial TLR4 sufficiently responds to LPS exposure, we first confirmed the expression of Tlr4 in both Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice. The persistent expression of Tlr4 in PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f endothelial cells suggests that endothelial TLR4 is an effective sensor to propagate LPS signaling to induce PTB because Pgr-Cre is incapable of deleting endothelial Tlr4 (Figure 3A). Indeed, co-staining of PR and CD31 clearly shows that endothelial cells in days 4 and 16 uterus are PR negative during pregnancy (Figure 3B). We investigated the significance of endothelial TLR4 by using a Tie2-Cre driver to circumvent the limitation of the Pgr-Cre driver. The results from Tie2Cre/+ Rosa26Tomato reporter mice show that Tie2-Cre is primarily expressed in blood vessel endothelia in the decidua (Figure S4G). We also observed that Tie2-Cre does not show any recombination in immune cells, indicating Tie2 expression is specific to endothelial cells, which was verified by the absence of tomato reporter in the stromal compartment (Figure S4G). The deletion efficiency of Tlr4 was confirmed by qPCR and digoxin (DIG)-ISH (Figures S4H and S4I). Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice exposed to LPS show normal litter size and parturition without any apparent adverse effects on viability and growth rate of pups or apparent distress of the mother upon delivery (Figures 3C–3E and S4J). In contrast to PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice, LPS at a low dose (2.5 μg/mouse) does not provoke harmful effects in Tlr4f/f or Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice. Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice were then challenged with a higher dose of LPS (40 μg/mouse). Although 100% of Tlr4f/f mice show PTB at this high dose, no observable deleterious effects were noted in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice. They show normal litter sizes and parturition timing (Figures 3C–3E). The total abrogation of LPS-induced PTB in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice suggests that endothelial TLR4 activation is indispensable for LPS-triggered signal transduction in the decidua.

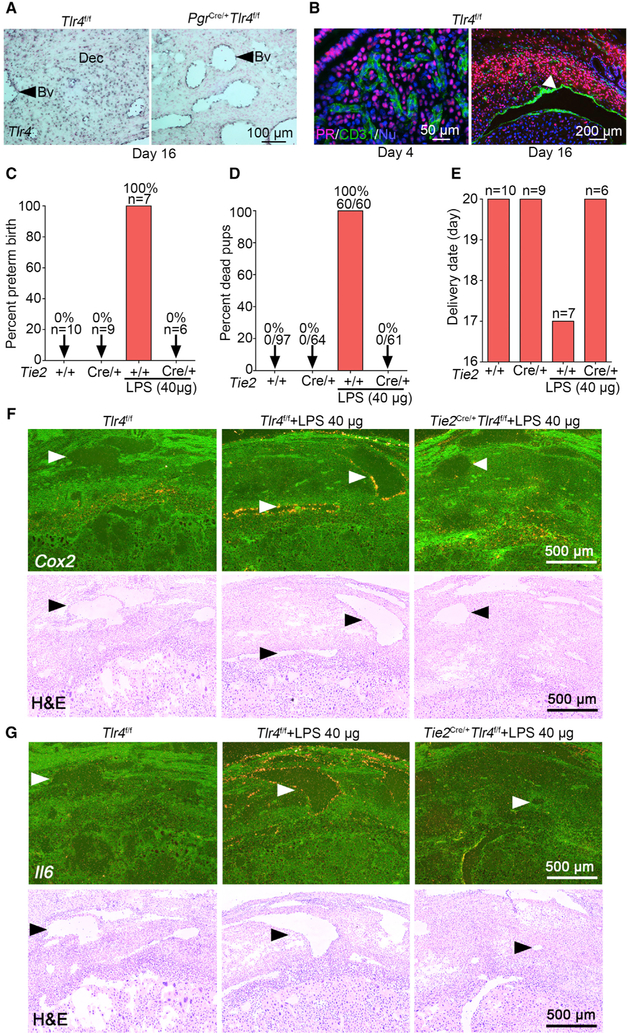

Figure 3. Endothelial-Specific Tlr4 Deletion with a Tie2-Cre Driver Protects against LPS-Induced Preterm Birth.

(A) DIG-in situ hybridization for Tlr4 in decidual endothelia of Tlr4f/f and PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice on day 16 of pregnancy. Blue color indicates the Tlr4 signal. Dec, decidua. Arrow heads indicate blood vessels (Bv). Scale bar, 100 μm.

(B) PR (progesterone receptor)-positive cells are absent in the endothelium in days 4 (left) and 16 (right) uteri. Arrow head indicates blood vessel. Scale bars for the left and right panels represent 50 μm and 200 μm, respectively.

(C and D) The ratio of preterm birth (C) and dead pups (D) compared to total number of pups in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice with or without a high dose of LPS (40 μg/mouse). n, number of dams examined.

(E) Parturition timing in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice with or without LPS. n, number of dams examined.

(F) Dark-field and bright-field images of in situ hybridization for Cox2 in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f deciduae after 1 h of LPS exposure (40 μg/mouse). Arrow heads indicate blood vessels. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(G) Dark-field and bright-field images of in situ hybridization for Il6 in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f deciduae after 1 h of LPS exposure (40 μg/mouse). Arrow heads indicate blood vessels. Scale bar, 500 μm.

See also Figure S4.

To better understand the underlying cause of LPS resistance in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice, we examined the expression of inflammation-associated cytokines in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice in the absence or presence of LPS. The expression of Cox2 and Il6 is primarily induced in endothelial cells of Tlr4f/f mice by LPS but not in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice (Figures 3F and 3G). Our fluorescence ISH (RNA-FISH) coupled with Il6 DIG probe is consistent with radioactive ISH results (Figure S4K). qPCR results show that both Il6 and Il10 are induced at low and high doses (2.5 or 40 μg/mouse) of LPS in Tlr4f/f mice, whereas these inductions are not seen in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice (Figures 4A and 4B). We also observed higher induction of Il6 in Tlr4f/f mice in the presence of a higher dose of LPS (Figure 4A). The decreased ratio of expression Il10/Il6 in Tlr4f/f mice at a high dose of LPS further supports that the balance between pro-inflammation and anti-inflammation is disturbed under higher LPS dose in floxed mice (Figure 4C). This imbalance of IL-10 and IL-6 is likely to account for PTB at a higher dose of LPS.

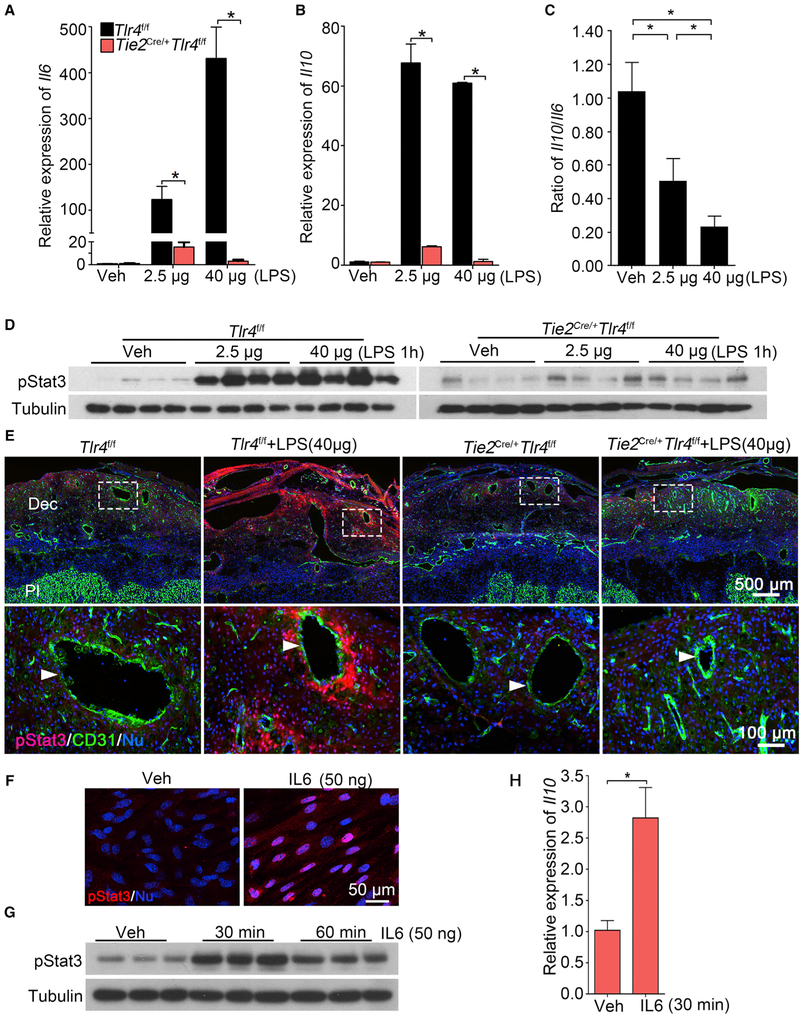

Figure 4. Endothelial TLR4 Is Critical for Sensing LPS-Induced Responses in Decidua.

(A and B) Relative expression of Il6 (A) and Il10 (B) mRNAs in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice after a low dose (2.5 μg/mouse) or high dose (40 μg/mouse) of LPS treatment for 1 hour. n = 4. *p < 0.05. Results are shown as mean ± SEM.

(C) Ratio of mRNA levels of Il10 versus Il6 in deciduae of Tlr4f/f mice under a low and high dose of LPS. n = 4. *p < 0.05. Results are shown as mean ± SEM.

(D) western blotting of protein levels for pStat3 in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice after 1 h of a low or high dose of LPS treatment on day 16 of pregnancy, n = 4.

(E) Co-immunostaining of pStat3 (red) and CD31 (green) in LPS-treated deciduae of Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice. Scale bar of upper panels, 500 μm. Bottom panels show images of higher magnification of those within the demarcated rectangles (Scale bar, 100 μm). Arrowheads indicate endothelial cells. Dec, deciduae; Pl, placenta.

(F) pStat3 nuclear translocation by IL-6. Isolated stromal cells were treated with recombinant IL-6 (50 ng) for 30 min. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(G and H) pStat3 levels (G) and Il10 mRNA levels (H) after recombinant interleukin 6 (rIL-6) challenge. Tubulin and rpL7 were used as internal controls for western blotting and qPCR, respectively. n = 3. *p < 0.05. Results are shown as mean ± SEM.

See also Figures S5, S6, and S7.

IL-6 Can Activate Stat3 and Il10 Expression in Decidual Cells in Culture

Activation of Stat3 (pStat3) is seen in Tlr4f/f deciduae after LPS exposure, but this activation is absent in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice after exposure to LPS (Figures 4D and 4E). To examine if IL-6 can directly activate Stat3, isolated stromal cells from pregnant day 4 uterus were cultured to decidualized cells by estrogen and P4 (Deng et al., 2016), followed by exposure to IL-6. We found significant nuclear pStat3 enrichment and elevated pStat3 levels along with higher Il10 mRNA levels (Figures 4F–4H). IL-6 mediates its function by engaging IL-6 receptor (Il6r) and Gp130 to trigger Stat3 phosphorylation (Johnson et al., 2018). ISH results show expression of Il6r and Gp130 in the decidua (Figure S5A). qPCR results show that their expression levels are comparable in both genotypes with or without LPS exposure (Figure S5E).

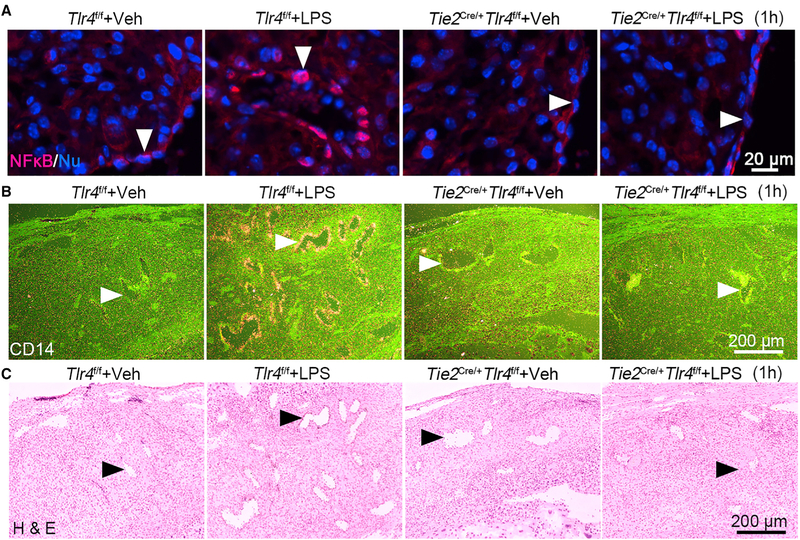

Furthermore, cytoplasmic NF-kB fails to translocate to endothelial cell nuclei after LPS treatment in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice (Figure 5A). CD14 is a co-receptor of TLR4 for LPS binding and cellular uptake; its expression is dependent on NF-kB signaling (Zanoni et al., 2011). Our results show that CD14 is primarily induced by LPS in endothelial cells in Tlr4f/f mice but not in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice, suggesting that NF-kB activation in the endothelium is abrogated in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice (Figures 5B and 5C).

Figure 5. Endothelial NF-kB and CD14 Are Downregulated in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f Deciduae.

(A) Immunostaining shows nuclear translocation of NF-kB (red) in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice after exposure to LPS (40 μg/mouse) for 1 hour. Arrow heads indicate endothelial cells. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(B and C) LPS-induced expression of Cd14 by radioactive in situ hybridization (B) in day 16 decidual endothelial cells in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice. The lower panel (C) represents H&E-stained images. Arrow heads indicate endothelial cells. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Resident Decidual Immune Cells Are Not a Target of LPS

Because immune cells are considered a major source of cytokines, we examined the distribution of immune cells in deciduae after exposure to LPS. An abundant population of uterine NK (uNK) cells were noted in deciduae of both Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+ Tlr4f/f mice, but their distribution patterns were comparable after LPS challenge in the presence or absence of endothelial TLR4 (Figure S5B). As Stat3 is important for the production of cytokines in NK cells (Saraiva and O’Garra, 2010), we explored if pStat3 is activated in uNK cells after LPS treatment. Co-staining shows that pStat3 and uNK cells are rarely co-localized in the presence of LPS (Figure S5C). The unaltered expression of GzmA and GzmC, major markers of NK cells, is consistent with the finding of unaltered distribution of uNKs (Figures S5D and S5E).

The number of macrophages is scanty in the decidua and restricted in the myometrium as previously reported (Nancy et al., 2012; Tachi and Tachi, 1986). Macrophage population remains unchanged before and after LPS challenge for 1 and 6 hours (Figures S6 and S7) and that neutrophil distribution was rare in uterine decidua even after LPS exposure; only a few are seen adhered to the endothelium (Figures S6 and S7). The staining of CD45, a common marker of leukocytes, also did not show obvious changes in distribution (Figures S6 and S7), suggesting that endothelial TLR4 is minimally or not engaged with immune cells to produce cytokines in the decidua to provoke PTB. Similar to PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice, the immune cells do not exhibit PR expression in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f mice (Figures S6 and S7).

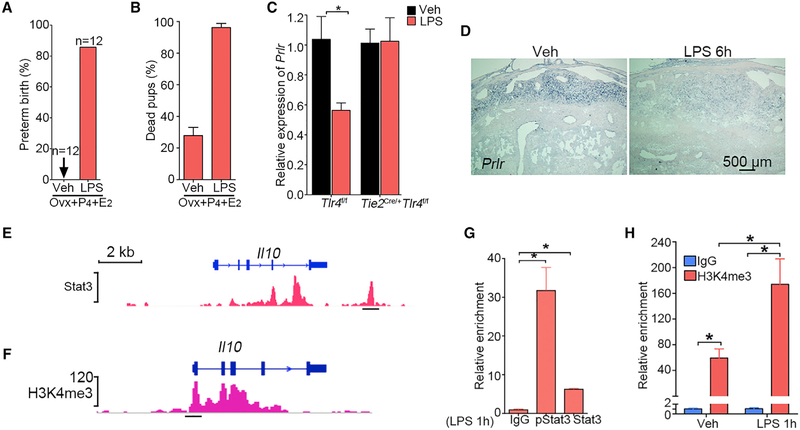

The Ovary Is Not a Target of PTB When LPS Is Given on Day 16

There are reports that LPS targets the ovary and induces PTB by reducing P4 levels (Aisemberg et al., 2013; Cha et al., 2013). Our results show that Tlr4 expression is quite low in the ovary (Figure 1B), and evidence suggests that decidual health, as evident from the expression of PlpJ and Prlr, is critical for the functional lifespan of the corpus luteum (Cha et al., 2013). To circumvent the effects of LPS-induced ovarian steroid hormonal changes, day 16 pregnant females were ovariectomized and injected with a combination of hormones, which maintains pregnancy with normal parturition timing. In contrast, an LPS (40 μg) injection on day 16 along with similar hormones injections induces PTB within 48 hours with stillbirths (Figures 6A and 6B). Considering the high abundance of TLR4 expression in the decidua with rapid response to LPS, these results strongly support that the decidua is a direct target of LPS and by inference other bacterial infections. Downregulation of Prlr by LPS in Tlr4f/f mice but not in Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice further supports that LPS dampens decidual health through endothelial TLR4 (Figures 6C and 6D).

Figure 6. LPS Targets Deciduae, Not Ovaries, and Regulation of IL-10 by Stat3.

(A) Incidence of PTB in pregnant mice ovariectomized on day 16 with or without exposure to LPS (40 μg/mouse) followed by P4 injections (1 mg) on days 16 and 17 and 250 μg of P4 on day 18 with an additional injection of estradiol-17β (100 ng) on day 19. All ovariectomized (Ovx) mice given P4 and E2 without LPS showed normal delivery, albeit 40% dead pups. In contrast, over 90% of LPS-treated mice delivered dead pups before day 19 with 100% dead pups. Ovx, ovariectomy. n, number of mice examined in each group.

(B) Rate of dead pups in mice with or without LPS injection after ovariectomy followed by P4 and E2 injection. n = 12.

(C) Relative expression of Prlr mRNA in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice after exposure to LPS (40 μg/mouse) for 1 hour. n = 4, *p < 0.05. Results are shown as mean ± SEM.

(D) DIG-in situ hybridization for Prlr in Tlr4f/f mice after 6 h of LPS (40 μg/mouse) treatment. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(E and G) Graphic representation of predicted Stat3 binding site on the Il10 gene (E) and ChIP-qPCR confirmation of binding by both pStat3 and Stat3 antibodies in deciduae after LPS injection for 1 h (G). n = 3, *p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

(F and H) Graphic representation of H3K4me3 enrichment at the Il10 promoter region (F) with ChIP-qPCR confirmation in deciduae after LPS injection for 1 h (H). n = 3, *p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

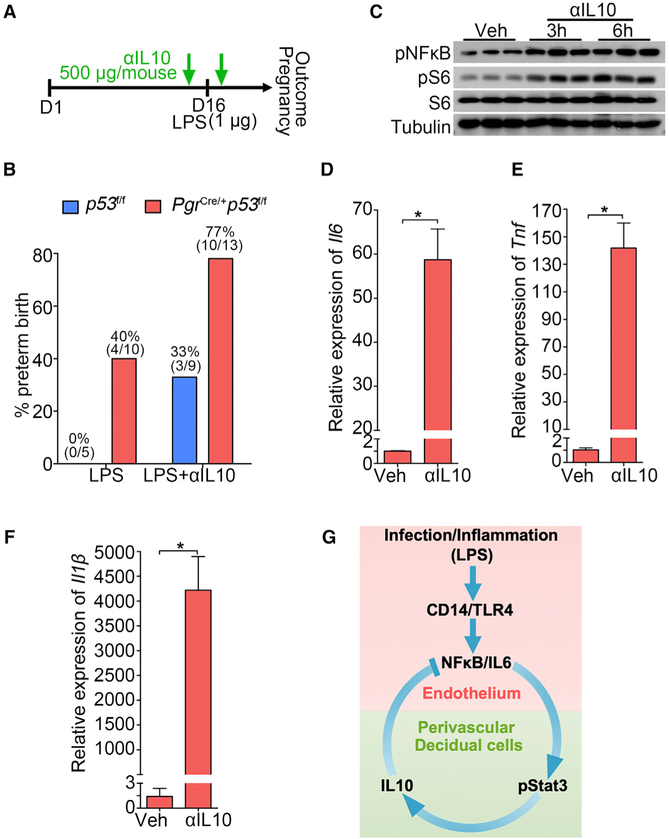

IL-10 Confers Protection against PTB in Response to Inflammation

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine and safeguards against infection or inflammation, and Stat3 is considered a major regulator of IL-10 expression (Saraiva and O’Garra, 2010). The mining of the published chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) database suggests a potential Stat3 binding site at the downstream region of Il10 gene and histone modification at the promoter region (Figures 6E and 6F). We verified the binding by ChIP-qPCR by using both pStat3 and Stat3 antibodies as well as H3K4me3 antibody in LPS-treated decidua (Figures 6G and 6H); samples from untreated uteri were below the detection levels. Our results suggest that IL-10 is transcriptionally and epigenetically regulated by LPS.

We next asked if neutralization of IL-10 enhances PTB incidence. IL-10 knockout mice are extremely sensitive to external infection and show inflammatory bowel disease syndrome (Kühn et al., 1993). Therefore, we adopted a different approach to neutralize endogenous IL-10. A neutralizing antibody to IL-10 (500 μg/mouse) was injected into both wild-type (WT) (p53f/f) and PTB predisposed mice (PgrCre/+p53f/f) 30 min before and after an LPS injection on day 16 to monitor parturition timing (Clemente-Casares et al., 2016). We found increased incidence of PTB in both genotypes even at a dose as low as 1 μg/mouse LPS with increased incidence of PTB in predisposed mice (Figures 7A and 7B). Normally, administration of 2.5 μg LPS does not lead to any adverse pregnancy effects in p53f/f (WT) mice, but administration of an IL-10 neutralizing antibody substantially increases the sensitivity of these mice to LPS. To better understand the underlying mechanism of increased PTB rate upon IL-10 inhibition, decidualized stromal cells were treated with an anti-IL-10 antibody. Increased phosphorylated nuclear factor NF-kappa-B (pNFkB) levels indicate heightened inflammation after administration of IL-10 neutralizing antibody (Figure 7C). pS6 levels are also substantially elevated by the IL-10 antibody (Figure 7C), mimicking some aspects of LPS-treated deciduae (Figure 2A). Notably, higher levels of Il6, Tnf, and Il1β after IL-10 neutralization also suggest the anti-inflammatory role of IL-10 in decidualized stromal cells (Figures 7D–7F). Our previous results suggest that increased mTORC1 signaling is an important determinant of PTB. Thus, increased pS6 levels by LPS and anti-IL-10 indicates that the function of IL-10 in parturition at least partially influences the mTORC1 signaling pathway, which is supported by a recent study (Ip et al., 2017).

Figure 7. The Role of IL-10 in PTB Prevention.

(A) A scheme of treatment schedule of IL-10 neutralizing antibody (αIL-10).

(B) Preterm birth rate of p53f/f and PgrCre/+p53f/f mice after IL-10 neutralizing antibody (αIL-10) injection in the presence of a ultra-low dose of LPS exposure (1 μg/mouse). The number in parentheses indicates the incidence of PTB in total number of mice analyzed.

(C) Western blot results for pNFkB and pS6 levels in decidualized stromal cells after IL-10 neutralizing antibody treatment for 3 and 6 hours.

(D–F) Il6 (D), Il1b (E), and Tnf (F) mRNA levels by IL-10 neutralizing antibody treatment. n = 3, *p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

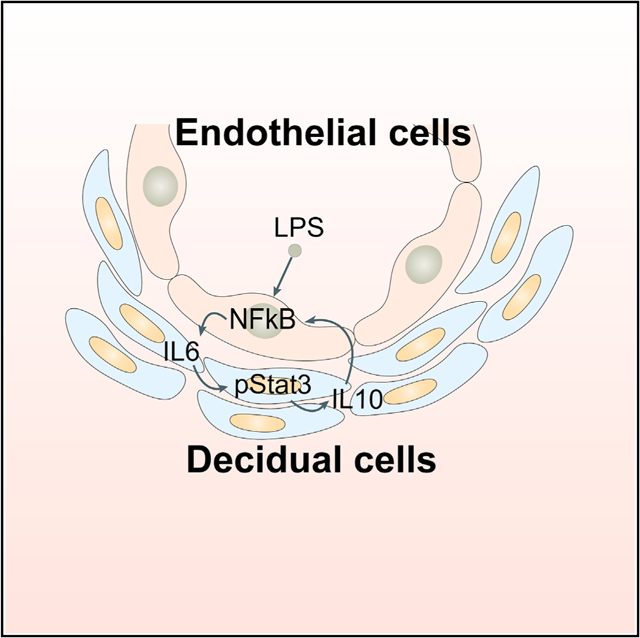

(G) A representative scheme of a physiological role of endothelial TLR4 in LPS-induced inflammation. After binding with LPS, endothelial TLR4 directs NFkB nuclear translocation to stimulate endothelial IL-6 expression in endothelial cells. Locally generated IL-6 stimulates Stat3 phosphorylation in perivascular decidual cells for IL-10 expression. Activation of endothelial TLR4 by LPS, which counters endogenous IL-10 production, results in preterm birth. CD14 is a co-receptor for TLR4 and highly induced in endothelial cells after LPS stimulation.

DISCUSSION

Our observation of abundant expression of TLR4 in the decidua suggests that the signal transduced by this member of the TLR family plays a functional role during normal pregnancy. In this respect, the findings of highest levels of Tlr4 mRNA among the other family members in the decidua support TLR4 function in pregnancy outcomes. In contrast, surprisingly low levels of Tlr4 expression in the placenta suggest that the decidua plays a major role in modulating systemic infection or inflammation during pregnancy, although placental roles in regulating inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses under local microbial infection cannot be ruled out. We have provided evidence that endothelial TLR4 in coordination with perivascular stromal cells in the decidual bed calibrates the degree of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses to inflammation in pregnancy. The role of endothelial TLR4 has not been widely explored in other systems, although our results are consistent with only two published reports showing a protective role of endothelial TLR4 deletion in the intestine and brain (Tang et al., 2017; Yazji et al., 2013). Here, we show that endothelial TLR4 in the decidual bed is also a major target for inflammation-induced PTB, but the function of decidual TLR4 remains obscure. However, compromised pregnancy outcomes of PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice in the absence of LPS and sensitivity of these mice to LPS driving PTB suggest that decidual TLR4 has a role in pregnancy, the function of which is not clearly understood at this time and is a subject of future investigation.

In this study, we provide evidence that the decidua functions as a rheostat to establish a homeostatic balance between inflammation and anti-inflammation following infection or inflammation in pregnancy, and this balance is crucial to pregnancy success. This study shows that the decidua is endowed with anti-inflammatory activity that can offset certain inflammatory responses. Under infection or inflammation, the dynamic balance is challenged, and PTB occurs if the degree of inflammation is excessive. Our results illustrate a rapid inflammatory response after LPS challenge in day 16 deciduae that gradually decreases to a basal level. The prompt release of inflammatory cytokines after LPS exposure often generates an inflammatory cytokine stress in genetically predisposed mice, such as PgrCre/+p53f/f mice (Hirota et al., 2010) or PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f mice. These mice experience PTB, even after a small dose of LPS challenge that is tolerable in normal pregnant mice.

The expression of IL-6 and Cox2 in decidual endothelial cells and induction of pStat3 in the nuclei of perivascular decidual cells following LPS stimulation perhaps initiate a cascade of signaling events. Myometrial contractions driven by increased prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) is considered important for delivery. However, previous and present results show that Cox2 expression is primarily expressed in the decidual stromal cells and endothelial cells, but not muscle cells, under normal and after LPS challenge. These results suggest that PGs originating in the decidua influence myometrial contractility (Hirota et al., 2010). Because IL-6 is known to activate Stat3 (Johnson et al., 2018; Yasukawa et al., 2003), it is assumed that IL-6 induces perivascular Stat3 phosphorylation, which is promptly followed by anti-inflammatory responses as a protective measure, as seen in WT mice in response to mild inflammation (low LPS doses) to preserve pregnancy. PTB ensues if the initial inflammatory response is overwhelming and overcomes physiologic anti-inflammatory responses, as seen in PTB-predisposed mice. Enhanced expression of pro-inflammatory mediators with dysfunctional anti-inflammatory pathways in Stat3-deleted macrophages and neutrophils suggests anti-inflammatory effects of Stat3 (Takeda et al., 1999). We suspect that pStat3 in decidual cells also confers protection against inflammation by regulating IL-10 expression, which is supported by studies in other systems (Saraiva and O’Garra, 2010). IL-10 is one of the earliest identified anti-inflammatory cytokines upregulated after LPS injection (Manzanillo et al., 2015). Our findings of increased decidual levels of IL-10 by LPS suggest that this cytokine plays a critical role in maintaining a homeostatic balance between the pro- and anti-inflammatory responses to resist PTB within a certain limit of infection or predisposition.

It is possible that resident immune cells in the decidua have a role in responding to LPS exposure in pregnancy. Although it cannot be completely excluded, our results show comparable distribution of CD45-positive cells in Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f deciduae after LPS treatment. These results suggest that immune cells do not play a major role in generating cytokines at the early stage of LPS challenge in the decidua. This is consistent with the observation that T cells and macrophages are predominantly confined to the myometrium in normal pregnancy (Nancy et al., 2012; Tachi and Tachi, 1986). Notably, deciduae on day 16 shows abundant NK (uNK) cells, which are thought to participate in vessel remodeling and nourishing the developing embryo (Fu et al., 2017). However, the distribution of uNK cells remains unaltered in the decidua after LPS treatment. In this context, our results suggest that decidual endothelial cells are endowed with a function that was previously attributed to immune cells.

It is possible that increases in inflammatory circulating cytokines originating from other organs contribute to PTB after LPS challenge. Whether circulating cytokines can directly target endothelial cells and then stromal cell gene expression is not known. It is more reasonable that local production of these cytokines by endothelial TLR4 in response to LPS or gram-negative bacteria would induce gene expression in a paracrine manner in perivascular stromal cells in the decidua. A comprehensive understanding to address this issue would necessitate generation of endothelial-specific Cre drivers for each organ, but this is a daunting task with the current state of our knowledge. Nonetheless, a critical role of endothelial TLR4 to mount an inflammatory insult to pregnancy after an injection of LPS is profound. TLR4 expression and its functions in resident immune cells in the decidua and uterus in PTB are not clearly understood at this time. Under our experimental conditions, Tie2 and PR are not expressed in these immune cells. Furthermore, Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f mice fail to evoke PTB with intact TLR4 in resident immune cells upon exposure to LPS even at a higher dose (40 μg/mouse). These results suggest that endothelial cell TLR4 is a primary inducer of PTB after LPS challenge.

Our previous studies have shown that decreased 5ʹ-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling with heightened mTORC1 activity contributes to premature decidual aging, leading to increased predisposition to infection or inflammation and PTB (Cha et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2016; Hirota et al., 2011; Hirota et al., 2010). Therefore, restraining adverse effects of mTORC1 signaling by IL-10 could be a mechanism by which this anti-inflammatory cytokine protects pregnancy from inflammatory insults (Ip et al., 2017).

IL-10 expression is regulated by many pathways and transcription factors (Saraiva and O’Garra, 2010). The spatiotemporal relationship of Stat3 phosphorylation and IL-10 induction after LPS stimulation in deciduae strongly suggest a connection between them. Stat3 has been shown to promote both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects through fine tuning of the expression of cytokines, such as IL-12 and IL-23 (Kortylewski et al., 2009), and a similar relationship between IL-10 and IL-6 is envisioned in the decidua, in which the ratio is likely to shift the balance toward or against a pro-inflammatory response in pregnancy. Our results of the ratio of Il10/Il6 mRNAs toward pro-inflammation under high doses of LPS leading to PTB corroborate this conjecture.

The observation that TLR4-dependent nuclear translocation of NFkB in endothelial cells and Stat3 activation in the perivascular decidual stromal cells with induction of cytokines by LPS suggests that one function of the decidua is to counter infection or inflammation during pregnancy within a certain limit but fails to do so in genetically predisposed mothers to PTB. The function of TLR4 in humans is not clearly understood. One study suggests that TLR4 is one of the master regulators for human delivery through regulation of a cohort of gene expression (Lui et al., 2018).

Taken together, this work reveals a potential mechanism of anti-inflammatory activity of IL-10 regulated by endothelial TLR4 in deciduae (Figure 7G). We provide evidence of transcriptional regulation of IL-10 by Stat3 in the decidua. Considering that a similar signature of IL-10 expression and regulation operates in human deciduae, our findings may contribute to potential strategies to combat PTB. In conclusion, our present results put forward a concept that decidual endothelial cells are critical for mounting inflammation resulting from infection with subsequent activation of anti-inflammation machinery in late pregnancy.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to, and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact S. K. Dey (SK.Dey@cchmc.org).

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animal care and housing

PgrCre/+Tlr4f/f and Tie2Cre/+Tlr4f/f female mice were generated by crossing Tlr4 floxed (Tlr4f/f, C57BL/6,129 mixed background) females with PgrCre/+ and Tie2Cre/+ males (C57BL/6,129 and albino B6 mixed background) (Kisanuki et al., 2001; Soyal et al., 2005). Tie2Cre/+Rosa26tdTomato mice were generated by crossing Tie2cre/+ males with Rosa26tdTomato female mice (Jackson lab). PgrCre/+p53f/f mice were generated by crossing p53 floxed mice (Hirota et al., 2010) with PgrCre/+ males. Tlr4 floxed mice have previously been described and were originally obtained from Chris Karp’s group (McAlees et al., 2015). Tlr4−/− (C57BL/6,129 mixed background) mice have previously been described (Hoshino et al., 1999). At least three female mice from each genotype were used for individual experiments. All mice used in this study were housed in the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Animal Care Facility according to NIH and institutional guidelines for the use of laboratory animals. All protocols of the present study were reviewed and approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were given autoclaved rodent LabDiet 5010 (Purina) and UV light–sterilized RO/DI constant circulation water ad libitum and were housed under a constant 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle.

Cell cultures and treatments

Stromal cells from day 4 of WT pregnant mice were collected by enzymatic digestion as previously described (Deng et al., 2016). The purity of stromal was confirmed by Vimentin and Desmin staining according to our published study (Daikoku et al., 2005). Isolated stromal cells were decidualized by estradiol-17β (E2, 10 nM) and progesterone (P4, 1 μM) in phenol red–free DMEM/F12 media supplemented with charcoal-stripped 1% FBS (vol/vol) for 4 days and medium was changed every 2 days.

METHOD DETAILS

Analysis of pregnancy outcomes

Three adult females from each genotype were housed with floxed fertile males from respective backgrounds overnight in separate cages. Successful mating (day 1 of pregnancy) was defined as the morning of finding the presence of a vaginal plug. Plug-positive females were housed separately until processed for experiments. Litter size, pregnancy rate and outcomes were monitored in timed pregnant mice. Ultrapure TLR4-specific LPS (2.5 μg/mouse and 40 μg/mouse, InvivoGen) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) on day 16 of pregnancy. Parturition was monitored from days 16 through 21 by daily observation of mice in the morning, noon and evening. Birth timing was defined by the observation of the first pup born. PTB was defined as birth occurring earlier than day 19 of pregnancy (day 1 = vaginal plug in the morning). Resorption sites and placental scars were identified in dams showing preterm or difficult deliveries by examination of the uterus. The number of pups/masses delivered was compared with the number of resorption sites and placental scars. Anti-IL10 antibody (500 μg/mouse, i.p., custom made, JES5–2A5) (Clemente-Casares et al., 2016) was injected in both p53f/f and PgrCre/+p53f/f mice 30 min before and after LPS injection (1 mg/mouse, i.p.). At least three independent mice in each genotype were used for biochemical and immunostaining assays.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Frozen sections (12 μm) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After blocking in 5% BSA, sections were incubated with specific primary antibodies at 4°C overnight (Yuan et al., 2016). After incubation with first antibody, slides were incubated in secondary antibodies conjugated with Cy-2, Cy-3, Alexa 488 or Alexa 594 (1:300, Jackson Immuno Research). Nuclear staining was performed using Hoechst 33342 (1:500, H1399, Thermo Scientific).

RNA Isolation and qPCR

RNA from tissue or cells in TRIzol was extracted by chloroform and isopropanol. Up to 500ng total RNA after removing genomic DNA from each sample was reverse transcribed with cDNA kit, and quantitative RT-PCR was performed in ABI Thermal Cyclers Real-Time PCR machine by 2−ΔΔCT method (Yuan et al., 2018). rpL7 served as an internal control and the relative expression was calculated according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoblotting

Samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors and quantified using a BCA kit. The protein extracts were run in 10% Bis-acrylamide gel and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking in 5% non-fat milk, the membranes were incubated with indicated antibodies overnight in 4°C. The membranes were washed in TBS-T and incubated with HRP conjugated secondary antibodies. The signal was visualized with an ECL kit.

Isolations of nuclei and cytoplasm

Deciduae from day 16 were collected and dissected from placenta, then subjected to homogenization by Dounce tissue grinder in PBS with proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors. After centrifuging, cells were resuspended in Buffer A (10 mM HEPES pH7.9, 10mM KCl, 0.1mM EDTA, 1mM DTT and 0.5mM PMSF, 2.5% NP40). Then the samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 15000 rpm. The supernatant was kept for cytoplasm and the remaining nuclei were dissolved in Buffer C (20 mM HEPES pH7.9, 400mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM DTT and 1mM PMSF) by vibrating for 30 mins. Both cytoplasm and nuclei were normalized to the same concentrations of protein.

In situ hybridization

Paraformaldehyde-fixed frozen sections from control and experimental groups were processed onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides and hybridized in formamide buffer with specific 35S-labeled cRNA probes. The slides were then coated with Carestream NTB emulsion and autoradiographs were developed and visualized under a Nikon dark-field microscope. Mouse-specific anti-sense cRNA probes for Cox2, Il6, Tlr4 GzmA, GzmC, Il6r and Gp130 were used. For DIG-ISH, DIG-labeled probes were generated according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche). After hybridization in formamide buffer, the slides were blocked in blocking buffer and incubated with Alkaline Phosphatase conjugated anti-Dig antibody and visualized by NBT/BCIP substrate (Yuan et al., 2016).

RNA-FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization was developed in our lab based on previously established DIG in situ hybridization (Yuan et al., 2016). In brief, following proteinase K (5 mg/ml) digestion and acetylation, slides were hybridized with DIG-labeled probes at 55°C. Anti-Dig-peroxidase was applied onto hybridized slides following washing and peroxide quenching. Color was developed by TSA (Tyramide signal amplification) Fluorescein according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PerkinElmer).

ChIP-PCR Assays

Day 16 decidua tissues from vehicle and LPS treated group were homogenized by Dounce tissue grinder in cold PBS with proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors. After centrifuging, the decidual stromal cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 10 mL of PBS containing 1% formaldehyde, then terminated by adding 2.5 M glycine. After incubation in Mg-NI buffer (15 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 60 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 15 mM NaCl, and 300 mM sucrose) and Mg-NI-Nonidet P-40 buffer (Mg-NI buffer with 1% Nonidet P-40), cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 0.5 mM EDTA) and sonicated by repeating a program (15 s on and 30 s off at 45% amplitude) 8 times. After the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min to pellet cell debris, the soluble chromatin was harvested. Immunoprecipitation was performed by incubation with antibody coated magnet beads. After washing, DNA was eluted from the beads and subjected to Real-time PCR with specific primers.

Identification of whole-genome binding sites of Stat3 and H3K4me3

The datasets used in this study were from GSM540722 (Durant et al., 2010) and GSE60005 (Choukrallah et al., 2015). Sequenced reads were aligned to the mouse genome (mm9) by bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Only non-redundant reads that passed the quality score were kept for downstream analysis. MACS2 (Model-Based Analysis of ChIP-Seq)(Zhang et al., 2008) was used to identify the peaks. The peaks were visualized in IGV browser.

Expression status of Tlrs identified by RNA-Seq analysis

Day 4 stromal and epithelial cells were isolated by enzyme digestion and total mRNA were extracted by TRIzol (Yuan et al., 2018). Total rRNAs were removed by RiboZero and the remaining RNAs were sequenced by HiSeq2500. The RNA-seq results of reported decidualized mouse stromal cells from day 8 and day 16 (Nancy et al., 2018) were re-analyzed by Tophat2 (Kim et al., 2013) and visualized by R (GEO: GSE105456). The RNA-Seq data of human normal endometrium data was downloaded from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) Data Portal. The expression of TLR4 in human endometrium cells was represented by RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization) and visualized by R.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Each experiment was repeated several times depending on the consistency of the results. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed Student’s t test and ANOVA. Shapiro-Wilk test was applied for normality test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. RNA-seq data of day 4 epithelium and stroma have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GEO: GSE116096.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rat anti-CD31 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 553370; RRID:AB_563954 |

| Rabbit anti-PR | Cell Signaling | Cat# 8757s; RRID:AB_2797144 |

| Rabbit anti-pStat3 | Cell Signaling | Cat#9145s; RRID:AB_2491009 |

| Rabbit anti-NFiκB | Cell Signaling | Cat# 8242s; RRID:AB_10859369 |

| Rabbit anti-pNFiκB | Cell Signaling | Cat# 3031s; RRID:AB_330559 |

| Rabbit anti-Cox2 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 12282s; RRID:AB_2571729 |

| Rabbit anti-H3K4me3 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9751s; RRID:AB_2616028 |

| Rabbit anti-pS6 | Cell Signaling | Cat#2211s; RRID:AB_331679 |

| Rabbit anti-S6 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 2217s; RRID:AB_331355 |

| Rabbit anti-Tubulin | Cell Signaling | Cat#2144s; RRID:AB_2210548 |

| Rabbit anti-Lamin A/C | Cell Signaling | Cat# 2032s; RRID:AB_10694918 |

| Rabbit anti-TLR4 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 14358s; RRID:AB_2798460 |

| Rat anti-CD4 (RM4–5) | Biolegend | Cat# 100505; RRID:AB_312708 |

| Rat Anti-CD45 | Biolegend | Cat# 103102; RRID:AB_312967 |

| Rat Anti-Ly6G | BD Bioscience | Cat# 551459; RRID:AB_394206 |

| Rat Anti-F4/80 | Bio-Rad | Cat# MCA497R; RRID:AB_323279 |

| Fluorescein labeled Dolichos Biflorus Agglutinin (DBA) | Vectorlabs | Cat#FL-1031–2 |

| Cy3 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rat IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#712-165-150; RRID:AB_2340666 |

| Cy3 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 705-165-147; RRID:AB_2307351 |

| Alexa Fluor® 594 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 711-585-152; RRID:AB_2340621 |

| Alexa Fluor® 488 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 711-545-152; RRID:AB_2313584 |

| Cy2 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rat IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 712-225-153; RRID:AB_2340674 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| LPS | Invivogen | Cat#tlrl-3pelps |

| rIL6 | Peprotech | Cat# 216–16 |

| BSA | Thermo Scientific | Cat#AM2616 |

| Hoechst 33342 | Thermo Scientific | Cat#H1399 |

| Anti-IL10 | Custom made | N/A |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Day 4 uterus RNA-Seq data | This study | GEO:GSE116096 |

| Day 8 and 16 stromal cells RNA-Seq data | Nancy et al., 2018 | SRA: SRP120624 |

| Stat3 ChIP-Seq | Durant et al., 2010 | SRA: SRX020337 |

| H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq | Choukrallah et al., 2015 | SRA: SRX668829 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Tlr4f/f | McAlees et al., 2015 | N/A |

| Mouse: p53f/f | Hirota et al., 2010 | N/A |

| Mouse: PgrCre/+ | Soyal et al., 2005 | N/A |

| Mouse: Tie2Cre/+ | Kisanuki et al., 2001 | N/A |

| Mouse: Tlr4−/− | Hoshino et al., 1999 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Bowtie2 | Langmead and Salzberg, 2012 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| MACS2 | Zhang et al., 2008 | https://github.com/taoliu/MACS |

| TopHat2 | Kim et al., 2013 | https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientificsoftware/prism/ |

Highlights.

Endothelial TLR4-mediated inflammation in the decidual bed contributes to preterm birth

Endothelial-stromal cell cross-talk confers a homeostatic balance in pregnant uteri

TLR4-Stat3 signaling regulates anti-inflammatory IL-10 expression to protect pregnancy

Tipping the balance toward inflammation induces preterm birth

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our sincere thanks to Katie Gerhardt for her efficient editing of the manuscript. We also thank Chris Karp and his group for proving the Tlr4 floxed and systemic Tlr4 mutant mice and Richard Lang for Tie2-Cre mice. This work was supported in part by NIH grants (R01HD068524, DA006668, and P01CA77839 to S.K.D.) and a center grant from the March of Dimes (22-FY17–889).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.049.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Aisemberg J, Vercelli CA, Bariani MV, Billi SC, Wolfson ML, and Franchi AM (2013). Progesterone is essential for protecting against LPS-induced pregnancy loss. LIF as a potential mediator of the anti-inflammatory effect of progesterone. PLoS One 8, e56161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmäe S, Koel M, Vôsa U, Adler P, Suhorut senko M, Laisk-Podar T, Kukushkina V, Saare M, Velthut-Meikas A, Krjut skov K, et al. (2017). Meta-signature of human endometrial receptivity: a meta-analysis and validation study of transcriptomic biomarkers. Sci. Rep 7, 10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha J, Bartos A, Egashira M, Haraguchi H, Saito-Fujita T, Leishman E, Bradshaw H, Dey SK, and Hirota Y (2013). Combinatory approaches prevent preterm birth profoundly exacerbated by gene-environment interactions. J. Clin. Invest 123, 4063–4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choukrallah MA, Song S, Rolink AG, Burger L, and Matthias P (2015). Enhancer repertoires are reshaped independently of early priming and heterochromatin dynamics during B cell differentiation. Nat. Commun 6, 8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Casares X, Blanco J, Ambalavanan P, Yamanouchi J, Singha S, Fandos C, Tsai S, Wang J, Garabatos N, Izquierdo C, et al. (2016). Expanding antigen-specific regulatory networks to treat autoimmunity. Nature 530, 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku T, Tranguch S, Friedman DB, Das SK, Smith DF, and Dey SK (2005). Proteomic analysis identifies immunophilin FK506 binding protein 4 (FKBP52) as a downstream target of Hoxa10 in the periimplantation mouse uterus. Mol. Endocrinol 19, 683–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Cha J, Yuan J, Haraguchi H, Bartos A, Leishman E, Viollet B, Bradshaw HB, Hirota Y, and Dey SK (2016). p53 coordinates decidual sestrin 2/AMPK/mTORC1 signaling to govern parturition timing. J. Clin. Invest 126, 2941–2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant L, Watford WT, Ramos HL, Laurence A, Vahedi G, Wei L, Takahashi H, Sun HW, Kanno Y, Powrie F, and O’Shea JJ (2010). Diverse targets of the transcription factor STAT3 contribute to T cell pathogenicity and homeostasis. Immunity 32, 605–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elovitz MA, and Mrinalini C (2004). Animal models of preterm birth. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 15, 479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu B, Zhou Y, Ni X, Tong X, Xu X, Dong Z, Sun R, Tian Z, and Wei H (2017). Natural Killer Cells Promote Fetal Development through the Secretion of Growth-Promoting Factors. Immunity 47, 1100–1113.e1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, and Romero R (2008). Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 371, 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierweger AM, Engler JB, Friese MA, Reichardt HM, Lydon J, DeMayo F, Mittrücker HW, and Arck PC (2019). Progesterone modulates the T-cell response via glucocorticoid receptor-dependent pathways. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 81, e13084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Daikoku T, Tranguch S, Xie H, Bradshaw HB, and Dey SK (2010). Uterine-specific p53 deficiency confers premature uterine senescence and promotes preterm birth in mice. J. Clin. Invest 120, 803–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y, Cha J, Yoshie M, Daikoku T, and Dey SK (2011). Heightened uterine mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling provokes preterm birth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18073–18078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, and Akira S (1999). Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J. Immunol 162, 3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip WKE, Hoshi N, Shouval DS, Snapper S, and Medzhitov R (2017). Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science 356, 513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, and Grandis JR (2018). Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 15, 234–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam L, Gomez-Lopez N, Mial TN, Kohan-Ghadr HR, and Drewlo S (2017). Rosiglitazone Regulates TLR4 and Rescues HO-1 and NRF2 Expression in Myometrial and Decidual Macrophages in Inflammation-Induced Preterm Birth. Reprod. Sci 24, 1590–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, and Salzberg SL (2013). TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanuki YY, Hammer RE, Miyazaki J, Williams SC, Richardson JA, and Yanagisawa M (2001). Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev. Biol 230, 230–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortylewski M, Xin H, Kujawski M, Lee H, Liu Y, Harris T, Drake C, Pardoll D, and Yu H (2009). Regulation of the IL-23 and IL-12 balance by Stat3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 15, 114–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn R, Löhler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, and Müller W (1993). Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell 75, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, and Salzberg SL (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui S, Duval C, Farrokhnia F, Girard S, Harris LK, Tower CL, Stevens A, and Jones RL (2018). Delineating differential regulatory signatures of the human transcriptome in the choriodecidua and myometrium at term labor. Biol. Reprod 98, 422–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanillo P, Eidenschenk C, and Ouyang W (2015). Deciphering the crosstalk among IL-1 and IL-10 family cytokines in intestinal immunity. Trends Immunol. 36, 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlees JW, Whitehead GS, Harley IT, Cappelletti M, Rewerts CL, Holdcroft AM, Divanovic S, Wills-Karp M, Finkelman FD, Karp CL, and Cook DN (2015). Distinct Tlr4-expressing cell compartments control neutrophilic and eosinophilic airway inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SI, Ernst RK, and Bader MW (2005). LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 3, 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett A, and Loke C (2006). Immunology of placentation in eutherian mammals. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6, 584–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moster D, Lie RT, and Markestad T (2008). Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N. Engl. J. Med 359, 262–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancy P, Tagliani E, Tay CS, Asp P, Levy DE, and Erlebacher A (2012). Chemokine gene silencing in decidual stromal cells limits T cell access to the maternal-fetal interface. Science 336, 1317–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancy P, Siewiera J, Rizzuto G, Tagliani E, Osokine I, Manandhar P, Dolgalev I, Clementi C, Tsirigos A, and Erlebacher A (2018). H3K27me3 dynamics dictate evolving uterine states in pregnancy and parturition. J. Clin. Invest 128, 233–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SA, Christiaens I, Dorian CL, Zaragoza DB, Care AS, Banks AM, and Olson DM (2010). Interleukin-6 is an essential determinant of on-time parturition in the mouse. Endocrinology 151, 3996–4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SA, Wahid HH, Chin PY, Hutchinson MR, Moldenhauer LM, and Keelan JA (2018). Toll-like Receptor-4: A New Target for Preterm Labour Pharmacotherapies? Curr. Pharm. Des 24, 960–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Dey SK, and Fisher SJ (2014). Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science 345, 760–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubens CE, Sadovsky Y, Muglia L, Gravett MG, Lackritz E, and Gravett C (2014). Prevention of preterm birth: harnessing science to address the global epidemic. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 262sr5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva M, and O’Garra A (2010). The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol 10, 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyal SM, Mukherjee A, Lee KY, Li J, Li H, DeMayo FJ, and Lydon JP (2005). Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis 41, 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryawanshi H, Morozov P, Straus A, Sahasrabudhe N, Max KEA, Garzia A, Kustagi M, Tuschl T, and Williams Z (2018). A single-cell survey of the human first-trimester placenta and decidua. Sci. Adv 4, eaau4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachi C, and Tachi S (1986). Macrophages and implantation. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci 476, 158–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Clausen BE, Kaisho T, Tsujimura T, Terada N, Förster I, and Akira S (1999). Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity 10, 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang AT, Choi JP, Kotzin JJ, Yang Y, Hong CC, Hobson N, Girard R, Zeineddine HA, Lightle R, Moore T, et al. (2017). Endothelial TLR4 and the microbiome drive cerebral cavernous malformations. Nature 545, 305–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vento-Tormo R, Efremova M, Botting RA, Turco MY, Vento-Tormo M, Meyer KB, Park JE, Stephenson E, Polański K, Goncalves A, et al. (2018). Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal-fetal interface in humans. Nature 563, 347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid HH, Dorian CL, Chin PY, Hutchinson MR, Rice KC, Olson DM, Moldenhauer LM, and Robertson SA (2015). Toll-Like Receptor 4 Is an Essential Upstream Regulator of On-Time Parturition and Perinatal Viability in Mice. Endocrinology 156, 3828–3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Li H, Zhu L, Gao J, Li P, and Zhang Z (2018). Increased TLR4 and TREM-1 expression on monocytes and neutrophils in preterm birth: further evidence of a proinflammatory state. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med 25, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, Murakami M, Chinen T, Aki D, Hanada T, Takeda K, Akira S, Hoshijima M, et al. (2003). IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat. Immunol 4, 551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazji I, Sodhi CP, Lee EK, Good M, Egan CE, Afrazi A, Neal MD, Jia H, Lin J, Ma C, et al. (2013). Endothelial TLR4 activation impairs intestinal microcirculatory perfusion in necrotizing enterocolitis via eNOS-NO-nitrite signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9451–9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Cha J, Deng W, Bartos A, Sun X, Ho HH, Borg JP, Yamaguchi TP, Yang Y, and Dey SK (2016). Planar cell polarity signaling in the uterus directs appropriate positioning of the crypt for embryo implantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E8079–E8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Deng W, Cha J, Sun X, Borg JP, and Dey SK (2018). Tridimensional visualization reveals direct communication between the embryo and glands critical for implantation. Nat. Commun 9, 603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Marek LR, Barresi S, Barbalat R, Barton GM, Granucci F, and Kagan JC (2011). CD14 controls the LPS-induced endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4. Cell 147, 868–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, and Liu XS (2008). Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. RNA-seq data of day 4 epithelium and stroma have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GEO: GSE116096.