Abstract

Sandhoff disease is an incurable neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutations in the lysosomal hydrolase β-hexosaminidase. Deficiency in this enzyme leads to excessive accumulation of ganglioside GM2 and its asialo derivative, GA2, in brain and visceral tissues. Small molecule inhibitors of ceramide-specific glucosyltransferase, the first committed step in ganglioside biosynthesis, reduce storage of GM2 and GA2. Limited brain access or adverse effects have hampered the therapeutic efficacy of the clinically approved substrate reduction molecules, eliglustat tartrate and the imino sugar NB-DNJ (Miglustat). The novel eliglustat tartrate analog, 2-(2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-yl)-N-((1R,2R)-1-(2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-1-hydroxy-3-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)propan-2-yl)acetamide (EtDO-PIP2, CCG-203586 or “3h”), was recently reported to reduce glucosylceramide in murine brain. Here we assessed the therapeutic efficacy of 3h in juvenile Sandhoff (Hexb −/−) mice. Sandhoff mice received intraperitoneal injections of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or 3h (60 mg/kg/day) from postnatal day 9 (p-9) to postnatal day 15 (p-15). Brain weight and brain water content was similar in 3h and PBS-treated mice. 3h significantly reduced total ganglioside sialic acid, GM2, and GA2 content in cerebrum, cerebellum and liver of Sandhoff mice. Data from the liver showed that 3h reduced the key upstream ganglioside precursor (glucosylceramide), providing direct evidence for an on target mechanism of action. No significant differences were seen in the distribution of cholesterol or of neutral and acidic phospholipids. These data suggest that 3h can be an effective alternative to existing substrate reduction molecules for ganglioside storage diseases.

Keywords: Glycosphingolipid, Ganglioside, Lysosomal Storage Disease, Neurodegeneration, Substrate Reduction Therapy, Sandhoff Disease

INTRODUCTION

Sandhoff disease is an incurable neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disease (LSD) caused by autosomal recessive mutations in the beta subunit of β-hexosaminidase (1). The deficiency of hexosaminidase A and B results in the storage of ganglioside GM2 and its asialo derivative (GA2) primarily in neurons. Hexb−/− mice suffer from neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, demyelination, progressive motor deterioration, and premature death by 16 weeks (2–6). Substrate reduction therapy (SRT) aims to prolong longevity in LSDs by reducing the production and load of stored lipid. Small molecule inhibitors of the ceramide-specific glucosyltransferase (glucosylceramide ceramide synthase) reduce downstream biosynthesis of gangliosides (7, 8). SRT has improved outcomes in murine models of Sandhoff disease, Tay-Sachs disease, GM1 gangliosidosis, Niemann Pick type C (NPC), Gaucher disease, and Fabry disease (9–20). Current clinically approved SRT molecules include imino sugar N-butyldeoxynojirimycin (NB-DNJ, Miglustat, Zavesca) and the D-threo-1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-propanol (PDMP) analog Genz-112638 (eliglustat tartrate). Both of these molecules have been administered to type 1 Gaucher disease patients (20–26). Due to its non-specificity, NB-DNJ has some adverse effects associated with prolonged usage, including weight loss, diarrhea, poor appetite, and tremor (20, 23). In addition, NB-DNJ binds directly to β-glucocerebrosidase where it acts as a molecular chaperone suggesting a more complicated mechanism of action on glucosylceramide metabolism (27, 28). Although eliglustat tartrate is therapeutically effective at lower doses (IC 50; 24 nM), therapeutic efficacy for neuronal LSDs is limited due to poor blood brain barrier (BBB) permeability (29, 30).

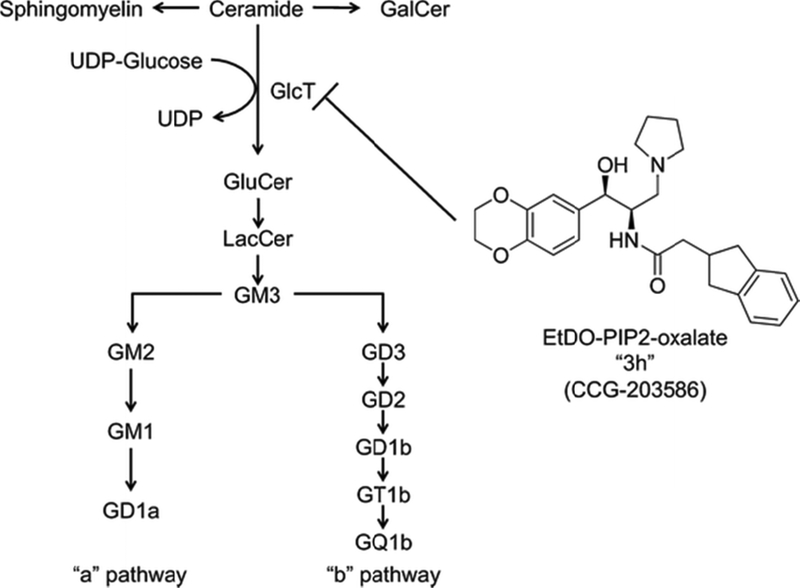

In contrast to eliglustat tartrate, its novel analog, D-threo-3’,4’-ethylenedioxy-1-phenyl-2-indanylacetoamino-3-pyrrolidino-1-propanol-oxalate (EtDO-PIP2, or 3h), enters the brain and reduces glucosylceramide in normal mice (Figure 1) (30). In this study, we have assessed the therapeutic effectiveness of 3h in Sandhoff mice. Juvenile Hexb−/− mice treated with 3h showed significant reductions in total ganglioside and GM2 content in brain and liver. The ganglioside reductions in brain were similar to those reported previously in LSD mice treated with the imino sugars, NB-DNJ and NB-DGJ (9, 10, 13, 14). Our results suggest that 3h could be a better substrate reduction therapy for prolonged treatment of peripheral and CNS LSDs.

Figure 1. Ethylenedioxy PIP2 oxalate, an inhibitor of ceramide glucosyltransferase.

The compound was synthesized and reported by Larsen et al. (30).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The SV/129 Hexb−/− mice were obtained from Dr. Richard Proia (NIH). These mice were derived by the disruption of the murine Hexb gene and transferring this gene into the mouse genome via homologous recombination and embryonic stem cell technology as previously described (2). The genotypes of mice were determined by PCR as previously described. Mice were propagated in the Boston College Animal Facility and were housed in plastic cages with filter tops containing Sani-Chip bedding (P.J. Murphy Forest Products Corp.; Montville, NJ). Food and water were provided ad libitum. Nursing females were provided with cotton nesting pads for the duration of the experiment. All animal experiments were carried out with ethical committee approval in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee.

3h treatment and tissue collection

The 3h molecule, D-threo-3’,4’-ethylenedioxy-1-phenyl-2-indanylacetoamino-3-pyrrolidino-1-propanol-oxalate, was produced at the Vahlteich Medicinal Chemistry Core, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. 3h was resuspended to a concentration of 1 mM in CHCl3: CH3OH 1:2 (v/v). The solution was dried under nitrogen, resuspended in 3.6 ml dH2O, and then dissolved at 42°C in shaking water bath. The solution was neutralized by adding 400 μl of 10 × phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and was sterilized following passage through an Acrodisc 0.2 μm syringe filter (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The final solution contained ~6.0 mg/ml of 3h. Mice were weighed daily and received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections equivalent to 60 mg/kg from postnatal day 9 (p-9) to postnatal day 15 (p-15). Control mice received i.p. injections of PBS. Injections were performed using a Hamilton syringe (26 gauge, point style 2, 0.5 inch needle) (Hamilton, Reno, NV), and volumes ranged from 50 μl to 100 μl/mouse. Mice were sacrificed 4 hrs after the final injection on p-15. Cerebrum, cerebellum, and liver were dissected and frozen on dry ice to determine wet weight. The tissues were then homogenized in 3.0 ml dH2O, and 150 μl of each homogenate was set aside for analysis of protein and lysosomal enzyme activities. The remaining homogenate was frozen at −80°C, was lyophilized, and was then weighed before lipid extraction.

Enzyme assays

β-hexosaminidase and β-galactosidase specific activities were measured using either 1 mM 4-methylumbelliferyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as the substrates, respectively (31). Tissue homogenates were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 2,000 × g. The collected supernatants were dispensed in duplicate to BD Falcon 96-well plates on ice. Increasing volumes of 40 μM 4-methylumbelliferone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 0.9% NaCl were used as standards. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes after the addition of substrate. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.5 M sodium carbonate (pH 10.7). A SpectraMax M5 micro-plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with excitation and emission set at 355 nm and 460 nm was used to estimate fluorescent emission of 4-methylumbelliferone. Total protein concentrations for each tissue were determined by mixing an aliquot of each sample with Bio-Rad Protein Dye Reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) diluted 1:4 (v/v) in water. Increasing concentrations of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used as standards. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes, and read at 595 nm in the SpectraMax M5. Specific enzyme activity was expressed as nmol/mg protein/hr.

Lipid isolation, purification, and quantitation

Total Lipid Isolation and Purification

Lipid extraction of lyophilized tissue was performed overnight in 5 ml CHCl3: CH3OH 1:1 (v/v) according to our standard procedures (32). Samples were spun down at 2500 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected. Pellets were washed in 2 ml CHCl3: CH3OH 1:1 (v/v), spun down again, and the total 7 ml of supernatant was brought up to a final volume of 19.6 ml at a ratio of 30:60:8 CHCl3: CH3OH: dH20 (v/v/v). Neutral lipids and cholesterol were separated from acidic lipids and gangliosides by ion exchange chromatography as we described (13, 32, 33). The column was washed twice with 20 mL solvent A and the entire neutral lipid fraction, consisting of the initial eluent plus washes, was collected. This fraction contained cholesterol, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine and plasmalogens, sphingomyelin, and neutral GSLs, including cerebrosides and asialo-GM2 (GA2). Next, acidic lipids were eluted from the column with 35 mL CHCl3: CH3OH: 0.8 M Na acetate, 30:60:8 by volume. Gangliosides were separated from acidic phospholipids by Folch partitioning, base treated, and desalted as previously described (13, 33). Neutral lipids were dried by rotary evaporation and resuspended in 10 mL CHCl3: CH3OH (2:1; v/v). A 4 mL aliquot was evaporated under nitrogen, base treated with 1 N NaOH, and Folch partitioned. The Folch lower phase containing GA2 and GlcCer was evaporated under nitrogen and resuspended in 4 mL CHCl3: CH3OH (2:1; v/v).

Ganglioside Sialic Acid Quantification

Total ganglioside content was quantified before and after desalting using the resorcinol assay as we previously described (33). Sialic acid values were fit to a standard curve using N-acetylneuraminic acid as a standard.

High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography

All lipids were analyzed qualitatively by high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) according to previously described methods (32, 33). The amount of lipid per lane was equivalent to 1.5 μg of total sialic acid for gangliosides, and 70 μg, 200 μg, and 300 μg of tissue dry weight for neutral lipids, acidic lipids, and GA2, respectively. For GlcCer analysis in liver, a total of 5.0 mg of tissue dry weight were spotted on the plate. HPTLC plates were developed by a single 90 min ascending run with CHCl3: CH3OH: dH2O (55:45:10; v/v/v for gangliosides; 65:35:8, v/v/v for GA2) containing 0.02% CaCl2 −2H2O. The plates were sprayed with either the resorcinol-HCl reagent or the orcinol-H2SO4 reagent and heated at 95°C for 10 min to visualize gangliosides or neutral glycosphingolipids (GA2 and glucosylceramide, GlcCer), respectively. The HPTLC distribution of neutral and acidic lipids was as previously described (10, 32). The bands were visualized by charring with 3% cupric acetate in 8% phosphoric acid solution (34). For GlcCer analysis in liver, a total of 5.0 mg of tissue dry weight were spotted on the HPTLC and developed by a single 30 min ascending run with CHCl3: CH3OH: dH2O (65:35:8, v/v/v).

Quantitation of Individual Lipids

The total brain ganglioside distribution was normalized to 100%, and the percentage distribution values were used to calculate sialic acid concentration (micrograms of sialic acid per 100 mg dry weight) of individual gangliosides. The density values for neutral lipids, acidic lipids, GA2 and GlcCer were fit to either a standard curve or known standard and were used to calculate individual concentrations expressed as milligrams per 100 mg dry weight. Oleyl alcohol was also run on the HPTLC plates as an internal standard for quantitation of cholesterol, and the neutral and acid phospholipids (10, 34).

Results

Our objective was to determine the influence of 3h on brain development and to assess whether 3h might be an effective substrate reduction therapy for juvenile Sandhoff disease (Hexb −/−) mice. The motor behavior of the 3h-treated mice with respect to ambulation was not noticeably different from that of the PBS control mice. Brain water content, β-hexosaminidase specific activity, and β-galactosidase specific activity were similar in the control and Hexb −/− mice treated with 3h at 60 mg/kg/day from p-9 to p-15 (Table 1). Water content is a sensitive indicator of brain development (35, 36). Body weight was slightly higher in the 3h-treated Hexb −/− mice than in the control Hexb −/− mice and was similar to that seen in the normal Hexb +/− mice. Total sialic content in 3h-treated mice was significantly lower in the 3h-treated Hexb −/− mice than in the control Hexb −/− mice in cerebrum (11%), cerebellum (14%), and in liver (38%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Body weight, brain water content, and enzymatic activity in p-15 Sandhoff mice treated with 3h.

| Hexb genotype | Treatment | na | Bodyweight (g) | Wet weight | Water content | β-Hexosaminidase specific activity |

β-Galactosidase specific activity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrum (mg) | Cerebellum (mg) | Cerebrum (%) | Cerebellum (%) | Cerebrum (nmol/mg protein g/h) |

Cerebellum (nmol/mg protein g/h) |

Cerebrum (nmol/mg protein g/h) |

Cerebellum (nmol/mg protein g/h) |

||||

| +/− | PBSb | 4 | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 287.6 ± 2.5 | 94.1 ± 6.6 | 84.45 ± 0.01 | 83.72 ± 0.01 | 293.8 ± 3.5 | 107.5 ± 4.4 | 42.0 ± 1.6 | 33.2 ± 1.7 |

| −/− | PBSb | 4 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | 264.4 ± 6.8 | 102.0 ± 4.0 | 84.59 ± 0.01 | 84.09 ± 0.01 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 62.5 ± 3.4 | 61.1 ± 1.7 |

| −/− | 3hc | 3 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 271.0 ± 2.3 | 87.7 ± 7.7 | 84.45 ± 0.01 | 83.88 ± 0.01 | 4.5 ± 0.0 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 69.4 ± 6.0 | 54.8 ± 7.6 |

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM)

n, the number of independent samples per group

Mice were injected daily from p-9 to p-15 with 1 × phosphate buffer saline

Mice were injected daily from p-9 to p-15 with 3h (EtDO-PIP2 oxalate) at 60 mg/kg/day

Table 2.

Effect of 3h on total ganglioside content in cerebrum, cerebellum and liver in p-15 Sandhoff mice

| Genotype | Treatment | na | Ganglioside sialic acid (mg/100 mg dry weight)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrum | |||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | 487 ± 11 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 500 ± 4 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 432 ± 11* |

| Cerebellum | |||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | 373 ± 6 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 391 ± 17 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 318 ± 15* |

| Liver | |||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | 57 ± 5 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 113 ± 6 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 70 ± 5** |

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Significantly different from the PBS-treated −/− group a P < 0.05 using the student’s t test.

Significantly different from the PBS-treated −/− group a P < 0.01 using the student’s t test.

n, the number of independent samples per group.

Total sialic acid content was determined by the resorcinol assay.

Mice were injected daily from p-9 to p-15 with 1 × phosphate buffered saline.

Mice were injected daily from p-9 to p-15 with 3h (EtDO-PIP2 oxalate) at 60 mg/kg/day.

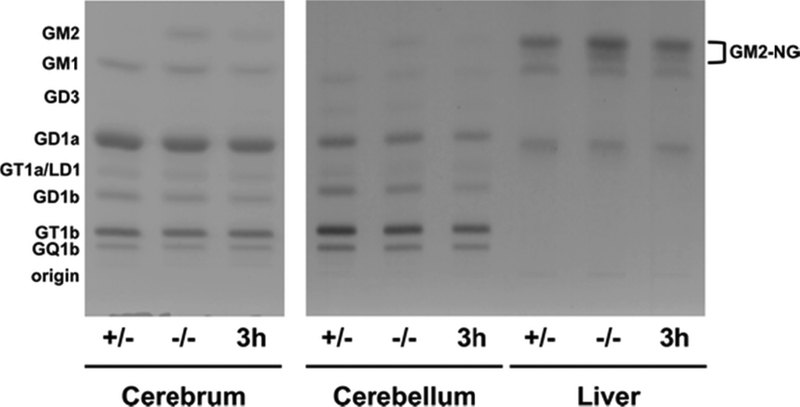

The influence of 3h on the qualitative and quantitative distribution of brain gangliosides is shown in Figure 2 and Table 3. Gangliosides that were undetectable or represented less than 1% of the total distribution (such as GD3 in cerebrum) were omitted from the analysis. Ganglioside GM2 comprised ~5% of ganglioside sialic acid content in p-15 Hexb −/− mouse cerebrum and cerebellum (Figure 2 and Table 3). 3h reduced GM2 content by 52% and 53%, respectively, in cerebrum and cerebellum of Hexb −/− mice. GM1, GD1a, GD1b, and GT1b content were also significantly reduced in cerebrum of Hexb −/− mice treated with 3h (Table 3). GD3, GD1b, and GT1b were significantly reduced in cerebellum of Hexb −/− mice treated with 3h (Table 3). In normal and Sandhoff mouse liver, GM2 containing N-glycolylneuraminic acid (NGNA) is the primary ganglioside (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). NGNA-GM2 content was significantly reduced by 45% in Hexb −/− mice treated with 3h compared to PBS-treated Hexb −/− controls (Table 2).

Figure 2. HPTLC of gangliosides from p-15 Sandhoff mice brain and liver.

Gangliosides from PBS-treated normal mice (+/−), PBS-treated Sandhoff mice (−/−), and Sandhoff mice treated with 3h at 60 mg/kg/day from p-9 to p-15 (3h) were separated in a single 90 min ascending run in CHCl3: CH3OH: dH20, 55: 45: 10 (v/v/v) with 0.02% CaCl2. The equivalent of 1.5 μg of sialic acid was spotted for each sample. The plate was sprayed with the resorcinol-HCl reagent and then charred at 95°C to visualize the ganglioside bands. A summary of the densitometric analyses of the HPTLC plates is shown in Table 2.

Table 3.

Effect of 3h on cerebrum, cerebellum, and liver ganglioside distribution in p-15 Sandhoff mice.

| Hexb Genotype | Treatment | nb | Concentration (μg sialic acid/100 mg dry weight)a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM2 | GM1 | GD3 | GD1a | |||||||

| Percent | Concentration | Percent | Concentration | Percent | Concentration | Percent | Concentration | |||

| Cerebrum | ||||||||||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | ND | ND | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 38.6 ± 1.3 | ND | ND | 44.5 ± 0.5 | 217.0 ± 5.6 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 25.6 ± 1.4 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 34.8 ± 1.5 | ND | ND | 43.0 ± 0.4 | 215.1 ± 3.1 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 2.8 ± 0.1* | 12.3 ± 0.3** | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 26.4 ± 1.6* | ND | ND | 43.4 ± 0.3 | 187.4 ± 5.2* |

| Cerebellum | ||||||||||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | ND | ND | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 24.2 ± 1.4 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 19.8 ± 1.6 | 22.8 ± 0.7 | 84.9 ± 3.6 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 20.8 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 22.9 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 19.2 ± 1.1 | 22.7 ± 0.2 | 88.7 ± 4.5 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 3.1 ± 0.1* | 9.8 ± 1.2** | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 17.4 ± 1.4 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 13.6 ± 0.7** | 24.1 ± 0.3* | 76.6 ± 3.7 |

| Liver | ||||||||||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | 59.5 ± 1.4 | 33.6 ± 2.5 | 25.3 ± 0.7 | 14.5 ± 1.6 | ND | ND | 15.2 ± 1.2 | 8.6 ± 1.1 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 68.7 ± 2.8 | 77.1 ± 4.8 | 18.0 ± 1.3 | 20.3 ± 1.9 | ND | ND | 13.3 ± 1.6 | 15.1 ± 2.2 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 60.5 ± 1.3 | 42.1 ± 2.6** | 21.9 ± 1.5 | 15.4 ± 2.1 | ND | ND | 17.6 ± 1.1 | 12.2 ± 0.3 |

| Hexb Genotype | Treatment | nb | Concentration (μg sialic acid/100 mg dry weight)a | |||||||

| GT1a/LD1 | GD1b | GT1b | GQ1b | |||||||

| Percent | Concentration | Percent | Concentration | Percent | Concentration | Percent | Concentration | |||

| Cerebrum | ||||||||||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 19.4 ± 1.4 | 9.6 ± 0.2 | 46.9 ± 1.3 | 27.0 ± 0.3 | 137.7 ± 4.3 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 33.8 ± 0.9 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 18.9 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.1 | 42.2 ± 0.9 | 26.2 ± 0.5 | 131.3 ± 3.2 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 32.4 ± 0.5 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 20.8 ± 0.7* | 7.3 ± 0.1* | 31.7 ± 0.5** | 27.8 ± 0.1* | 119.8 ± 3.3 | 7.7 ± 0.1* | 33.3 ± 0.7 |

| Cerebellum | ||||||||||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 21.0 ± 1.7 | 17.1 ± 0.4 | 63.7 ±2.3 | 30.8 ± 1.0 | 114.6 ± 3.5 | 12.0 ± 0.6 | 44.7 ± 2.1 |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 25.3 ± 1.2 | 15.2 ± 0.2 | 59.3 ± 2.9 | 29.1 ± 0.1 | 113.7 ± 5.3 | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 41.1 ± 1.1 |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | 7.2 ± 0.1* | 22.9 ± 1.0 | 13.2 ± 0.1* | 42.1 ± 2.0** | 29.7 ± 0.8 | 94.4 ± 3.9* | 12.9 ± 0.1 | 41.3 ± 3.8 |

| Liver | ||||||||||

| +/− | PBSc | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| −/− | PBSc | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| −/− | 3hd | 3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Significantly different from the PBS-treated −/− group at P < 0.05 using the student’s t test.

Significantly different from the PBS-treated −/− group at P < 0.01 using the student’s t test. ND, not dectectable; 3h, ethylenedioxy-PIP2 oxalate.

Percent distribution and concentration of individual gangliosides were determined by densitometric scanning of HPTLC plates.

n, the number of independent samples per group.

Mice were injected daily from p-9 to p-15 with 1 × phosphate buffered saline.

Mice were injected daily from p-9 to p-15 with 3h (EtDO-PIP2 oxalate) at 60 mg/kg/day.

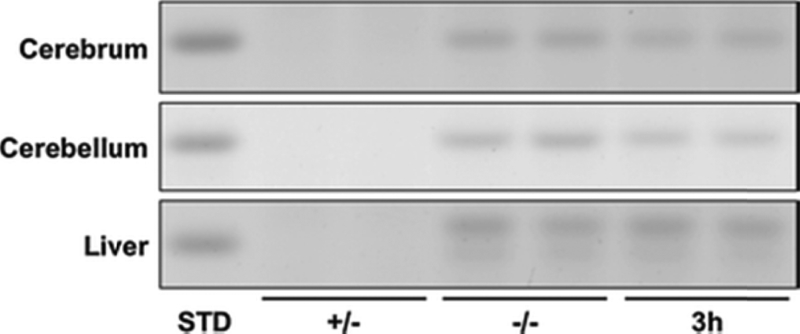

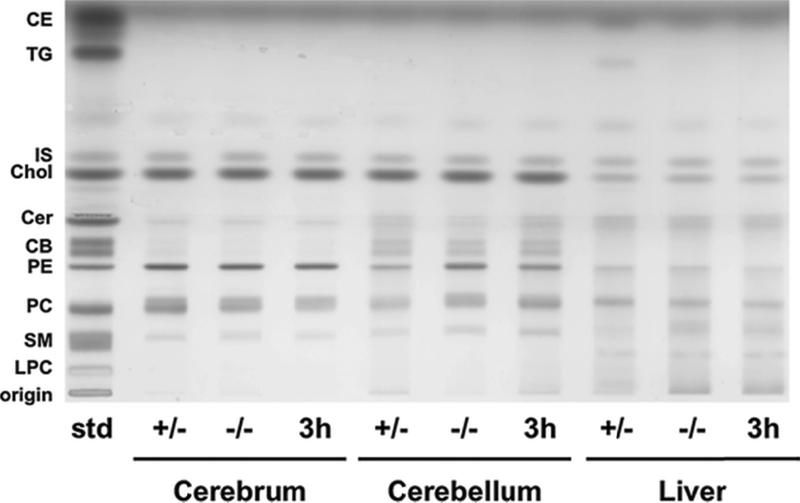

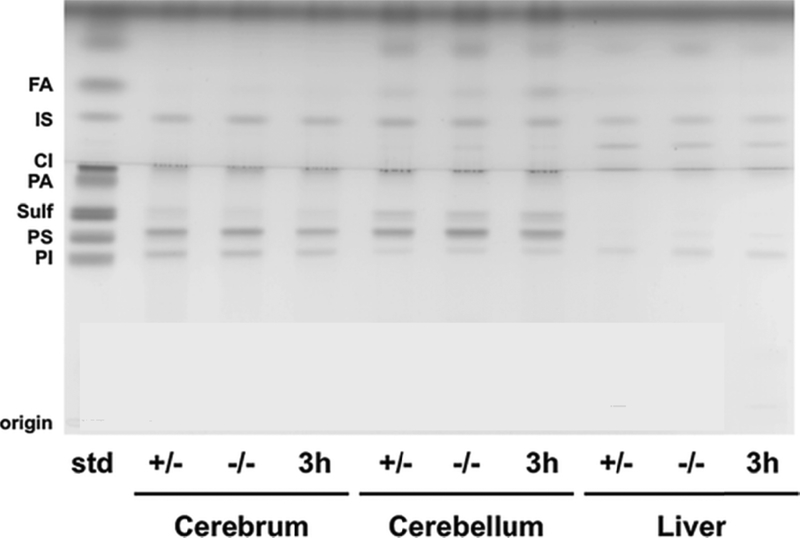

The influence of 3h on storage of asialo GM2 (GA2) is shown in Figure 3. GA2 is undetectable in normal mouse brain and liver (Figure 3, Table 4). GA2 in liver resolved as a doublet, similar to NGNA-GM2 (Figure 3, Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S1). 3h reduced GA2 in Hexb −/− liver, but this difference was not significant (p < 0.06). There were no differences in neutral and acidic lipid content for Sandhoff mice treated with PBS or 3h (Figure 4, Figure 5, Table 4). Notably, cerebellar cerebrosides, consisting of largely of galactosylceramide, were unchanged in Hexb −/− mice receiving 3h (Table 4). The content of GlcCer was evaluated only in liver, as liver did not contain detectable galactosylceramide, which would obscure low amounts of GlcCer. The content of GlcCer (μg/100 mg dry weight) in two independent liver samples from the control (PBS)-treated SD mice was 4.38 μg and 6.84 μg, whereas the GlcCer content in two independent liver samples from the 3h-treated SD mice was 2.91 μg and 3.62 μg. The average reduction in liver GlcCer content (41%) was comparable to the reduction of liver GM2 content (Table 2). These findings indicate that 3h targets the glucosyltransferase as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 3. HPTLC of GA2 from p-15 Sandhoff mice brain and liver.

Asialo The HPTCL was developed in a single 90 min ascending run in CHCl3: CH3OH: dH20, 65: 35: 8 (v/v/v) with 0.02% CaCl2. The amount of neutral lipid spotted per lane was equivalent to 300 μg tissue dry weight. The equivalent of 4 μg GA2 is shown in the standard (STD) lane. The bands were visualized by spraying the plate with orcinol-H2S04 and charring at 95°C. Other conditions were as described in Figure 2. A summary of the densitometric analyses is shown in Table 3.

Table 4.

Neutral and acidic lipid content in p-15 Sandhoff mice treated with 3h.

| Cerebrum | Cerebellum | Liver | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/− | −/− | 3h | +/− | −/− | 3h | +/− | −/− | 3h | |

| Neutral lipida | |||||||||

| TG | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.34 ± 0.28 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.07 |

| Choi | 5.35 ± 0.09 | 5.22 ± 0.11 | 5.13 ± 0.11 | 4.00 ± 0.28 | 4.70 ± 0.55 | 3.55 ± 0.33 | 1.43 ± 0.02 | 1.37 ± 0.04 | 1.48 ± 0.07 |

| Cer | 0.59 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 2.23 ± 0.49 | 1.02 ± 0.17 | 1.54 ± 0.29 | 4.37 ± 0.29 | 4.49 ± 0.08 | 4.01 ± 0.18 |

| CB | Trace | Trace | Trace | 2.11 ± 0.08 | 1.81 ± 0.14 | 1.61 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | ND |

| PE | 9.95 ± 0.35 | 9.77 ± 0.65 | 9.11 ± 0.58 | 3.34 ± 0.63 | 5.34 ± 1.31 | 3.12 ± 0.94 | 6.65 ± 0.18 | 5.22 ± 0.16 | 5.27 ± 0.94 |

| PC | 5.55 ± 0.33 | 5.91 ± 0.74 | 5.02 ± 0.91 | 3.70 ± 0.30 | 4.93 ± 0.81 | 3.68 ± 0.34 | 3.75 ± 0.10 | 2.27 ± 0.09 | 2.73 ± 0.33 |

| SM | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 1.20 ± 0.02 | 1.34 ± 0.04 |

| GA2 | ND | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.01** | ND | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.55 0.01* | ND | 1.31 ± 0.07 | 1.10 ± 0.05 |

| Acidic lipids | |||||||||

| CL | 1.63 ± 0.03 | 1.70 ± 0.07 | 1.62 ± 0.11 | 4.45 ± 0.15 | 3.63 ± 0.24 | 4.16 ± 0.09 | 1.51 ± 0.22 | 2.02 ± 0.26 | 2.88 ± 0.35 |

| Sulf | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 2.33 ± 0.29 | 1.97 ± 0.19 | 1.81 ± 0.56 | ND | ND | ND |

| PS | 4.21 ± 0.22 | 4.38 ± 0.30 | 4.08 ± 0.14 | 5.91 ± 0.16 | 5.69 ± 0.13 | 5.37 ± 0.35 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 1.03 ± 0.07 | 1.17 ± 0.06 |

| PI | 2.20 ± 0.06 | 2.22 ± 0.12 | 2.14 ± 0.12 | 1.75 ± 0.04 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | 1.57 ± 0.11 | 2.50 ± 0.14 | 2.46 ± 0.12 | 2.54 ± 0.10 |

Values are expressed as mg/100 mg dry weight. N= 3–4 mice per group.

Significantly different from the PBS-treated −/− group at P < 0.05 using the student’s t test.

Significantly different from the PBS-treated −/− group at P < 0.01 using the student’s t test. ND, not detectable; 3h, EtDO-PIP2. Lipid abbreviations are described in Figs. 4 and 5.

Concentrations of individual lipids were determined by densitometric scanning of HPTLC plates.

Figure 4. HPTLC of neutral lipids from p-15 Sandhoff mice brain and liver.

The HPTLC was developed to a height of 4.5 cm with chloroform: methanol: acetic acid: formic acid: water (35:15:6:2:1;v/v/v/v/v), then run to the top with hexane: diisopropyl ether: acetic acid (65:35:2; v/v/v). The amount of neutral lipid spotted per lane was equivalent to 70 μg tissue dry weight. The bands were visualized by charring with 3% cupric acetate in 8% phosphoric acid solution. Other conditions were as described in Figure 2. CE – Cholesterol Esters; TG – Triglycerides; IS – Internal Standard (Oleyl Alcohol); Chol – Cholesterol; Cer – Ceramide; CB – Cerebrosides (doublet); PE-phosphatidylethanolamine; PC – Phosphatidylcholine; SM – Sphingomyelin.

Discussion

Substrate reduction therapies using N-butyldeoxynojirimycin (NB-DNJ, Miglustat, Zavesca) or the glucose analog of NB-DGJ (N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin), are effective in reducing ganglioside storage and pathogenesis in mouse models of Tay–Sachs disease, Sandhoff disease, and GM1 gangliosidosis (4, 10–14, 17, 37, 38). Recently, we showed that intraperitoneal administration of the novel eliglustat tartrate analog, 3h, to normal adult C57BL/6 mice for three days caused a significant dose dependent decrease in the content of brain glucosylceramide, the upstream precursor for ganglioside biosynthesis (Figure 1) (30). It was not determined from this study, however, whether the reduction of glucosylceramide was associated with reduction of downstream synthetic products (gangliosides).

In this study we show that the daily injection of 3h from postnatal day 9 to 15 significantly reduced the total content of brain and liver gangliosides in SD (Hexb −/−) mice. Despite the absence of hexosaminidase β subunit, the degree of GM2 storage is considerably less in the SD mouse brain than in the infantile human SD brain (32). This might result in part from the activity of the hexosaminidase α subunit towards the GM2 substrate (2). 3h significantly reduced the accumulation of GM2 and GA2 in cerebrum, cerebellum, and in liver indicating a systemic therapeutic response. The reduction of ganglioside in liver was likely linked to the reduction observed for GlcCer, the up-stream metabolic precursor.

In contrast to NB-DNJ, which is known to reduce mouse body weight (16, 38), no adverse effects of 3h were detected on body weight over the treatment period. The reduction of total brain gangliosides and of GM2 and GA2 content in the Hexb −/− mice was obtained with a 3h dosage of 60 mg/kg/day. Although the reductions in mouse brain ganglioside content seen using 3h were similar to those seen previously using the NB-DNJ or NB-DGJ imino sugars, the therapeutic dosages used in the studies with the imino sugars ranged from 400–1200 mg/kg body weight (10, 11, 13, 14, 38). The influence of 3h on brain ganglioside content that we observed in this study and in our previous studies with the NB-DNJ or NB-DGJ imino sugars are markedly different from the findings reported recently for the Genzyme drug Genz-529468 (39). Although Genz-529468 is also an imino sugar, it increases rather than decreases GlcCer and GM2 content in the Hexb −/− mice (39). Both NB-DNJ and NB-DGJ significantly reduce GlcCer content in mouse embryos and in proliferating cells (7, 40, 41). The 3h-induced reduction of GlcCer we observed in liver and the 3h-induced inhibition of glucosyltransferase seen previously (30), indicates that these imino sugars and 3h target the same synthetic pathway. 3h may offer improved outcome over Genz-529468, as 3h targets GlcCer synthase and decreases rather than increases the deleterious storage materials. The concentration of therapeutic efficacy also appears to be better for 3h (60 mg/kg) than for the imino sugars (10, 38).

We previously showed that the therapeutic efficacy of NB-DNJ in targeting ganglioside storage could be enhanced when administered with a calorie restricted ketogenic diet (38). Although the mechanism remains unclear, the restricted ketogenic diet appears to enhance delivery of NB-DNJ through the blood brain barrier. Further studies will be needed to determine whether the ketogenic diet can enhance delivery of 3h to the brain. Long term survival studies and behavioral assessments will determine if 3h (CCG-203586) is a more efficient SRT than are the imino sugars for glycosphingolipid storage diseases.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5. HPTLC of acidic lipids from p-15 Sandhoff mice brain and liver.

The HPTLC was developed to a height of 6.0 cm with chloroform: methanol: acetic acid: formic acid: water (35:15:6:2:1; v/v/v/v/v), then run to the top with hexane: diisopropyl ether: acetic acid (65:35:2; v/v/v). The amount of acidic lipid spotted per lane was equivalent to 200 μg tissue dry weight. The bands were visualized by charring with 3% cupric acetate in 8% phosphoric acid solution. Other conditions were as described in Figure 2. FA – Fatty Acids; IS – Internal Standard (Oleyl alcohol) CL – Cardiolipin; PA – Phosphatidic Acid; Sulf – Sulfatides (doublet); PS - Phosphatidylserine; PI – Phosphatidylinositol.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported in part from NIH grants R21NS079633–1, 2RO1 DK055823, (JAS) and NS055195 (TNS) and the Boston College Research Expense Fund.

Abbreviations:

- GSL

glycosphingolipid

- GlcCer

glucosylceramide

- LSD

lysosomal storage disease

- SD

Sandhoff disease

- 3h

EtDO-PIP2-oxalate, ethylenedioxy-PIP2-oxalate, CCG-203586, 2-(2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-yl)-N-((1R,2R)-1-(2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-1-hydroxy-3-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)propan-2-yl)acetamide oxalate NGNA, N-glycolylneuraminic acid

- NB-DNJ

N-butyldeoxynojirimycin

- NB-DGJ

N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin.

References

- 1.Kolter T, Sandhoff K (2006) Sphingolipid metabolism diseases. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1758:2057–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sango K, Yamanaka S, Hoffmann A et al. (1995) Mouse models of Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff diseases differ in neurologic phenotype and ganglioside metabolism. Nat Genet 11:170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phaneuf D, Wakamatsu N, Huang JQ et al. (1996) Dramatically different phenotypes in mouse models of human Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff diseases. Hum Mol Genet 5:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeyakumar M, Butters TD, Dwek RA et al. (2002) Glycosphingolipid lysosomal storage diseases: therapy and pathogenesis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 28:343–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeyakumar M, Thomas R, Elliot-Smith E et al. (2003) Central nervous system inflammation is a hallmark of pathogenesis in mouse models of GM1 and GM2 gangliosidosis. Brain 126:974–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyrkanides S, Miller AW, Miller JN et al. (2008) Peripheral blood mononuclear cell infiltration and neuroinflammation in the HexB−/− mouse model of neurodegeneration. J Neuroimmunol 203:50–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Platt FM, Neises GR, Karlsson GB et al. (1994) N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin inhibits glycolipid biosynthesis but does not affect N-linked oligosaccharide processing. J. Biol. Chem 269:27108–27114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichikawa S, Hirabayashi Y (1998) Glucosylceramide synthase and glycosphingolipid synthesis. Trends Cell Biol 8:198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baek RC, Kasperzyk JL, Platt FM et al. (2008) N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin reduces brain ganglioside and GM2 content in neonatal Sandhoff disease mice. Neurochem Int 52:1125–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthur JR, Lee JP, Snyder EY et al. (2012) Therapeutic effects of stem cells and substrate reduction in juvenile Sandhoff mice. Neurochemical research 37:1335–1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platt FM, Neises GR, Reinkensmeier G et al. (1997) Prevention of lysosomal storage in Tay-Sachs mice treated with N-butyldeoxynojirimycin. Science (New York, N.Y 276:428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeyakumar M, Butters TD, Cortina-Borja M et al. (1999) Delayed symptom onset and increased life expectancy in Sandhoff disease mice treated with N-butyldeoxynojirimycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 96:6388–6393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasperzyk JL, d’Azzo A, Platt FM et al. (2005) Substrate reduction reduces gangliosides in postnatal cerebrum-brainstem and cerebellum in GM1 gangliosidosis mice. J Lipid Res 46:744–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasperzyk JL, El-Abbadi MM, Hauser EC et al. (2004) N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin reduces neonatal brain ganglioside content in a mouse model of GM1 gangliosidosis. J Neurochem 89:645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson U, Butters TD, Dwek RA et al. (2000) N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin: a more selective inhibitor of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis than N-butyldeoxynojirimycin, in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Pharmacol 59:821–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson U, Smith D, Jeyakumar M et al. (2004) Improved outcome of N-butyldeoxygalactonojirimycin-mediated substrate reduction therapy in a mouse model of Sandhoff disease. Neurobiol Dis 16:506–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliot-Smith E, Speak AO, Lloyd-Evans E et al. (2008) Beneficial effects of substrate reduction therapy in a mouse model of GM1 gangliosidosis. Mol Genet Metab 94:204–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall J, Ashe KM, Bangari D et al. (2010) Substrate reduction augments the efficacy of enzyme therapy in a mouse model of Fabry disease. PloS one 5:e15033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall J, McEachern KA, Chuang WL et al. (2010) Improved management of lysosomal glucosylceramide levels in a mouse model of type 1 Gaucher disease using enzyme and substrate reduction therapy. J Inherit Metab Dis 33:281–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollak CE, Hughes D, van Schaik IN et al. (2009) Miglustat (Zavesca) in type 1 Gaucher disease: 5-year results of a post-authorisation safety surveillance programme. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 18:770–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukina E, Watman N, Arreguin EA et al. (2010) A phase 2 study of eliglustat tartrate (Genz-112638), an oral substrate reduction therapy for Gaucher disease type 1. Blood 116:893–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukina E, Watman N, Arreguin EA et al. (2010) Improvement in hematological, visceral, and skeletal manifestations of Gaucher disease type 1 with oral eliglustat tartrate (Genz-112638) treatment: 2-year results of a phase 2 study. Blood 116:4095–4098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machaczka M, Hast R, Dahlman I et al. (2012) Substrate reduction therapy with miglustat for type 1 Gaucher disease: a retrospective analysis from a single institution. Ups J Med Sci 117:28–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shayman JA (2010) ELIGLUSTAT TARTRATE: Glucosylceramide Synthase Inhibitor Treatment of Type 1 Gaucher Disease. Drugs Future 35:613–620 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox TM, Aerts JM, Andria G et al. (2003) The role of the iminosugar N-butyldeoxynojirimycin (miglustat) in the management of type I (non-neuronopathic) Gaucher disease: a position statement. J Inherit Metab Dis 26:513–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox TM (2010) Eliglustat tartrate, an orally active glucocerebroside synthase inhibitor for the potential treatment of Gaucher disease and other lysosomal storage diseases. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 11:1169–1181 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brumshtein B, Greenblatt HM, Butters TD et al. (2007) Crystal structures of complexes of N-butyl- and N-nonyl-deoxynojirimycin bound to acid beta-glucosidase: insights into the mechanism of chemical chaperone action in Gaucher disease. The Journal of biological chemistry 282:29052–29058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alfonso P, Pampin S, Estrada J et al. (2005) Miglustat (NB-DNJ) works as a chaperone for mutated acid beta-glucosidase in cells transfected with several Gaucher disease mutations. Blood Cells Mol Dis 35:268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McEachern KA, Fung J, Komarnitsky S et al. (2007) A specific and potent inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthase for substrate inhibition therapy of Gaucher disease. Mol Genet Metab 91:259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen SD, Wilson MW, Abe A et al. (2012) Property-based design of a glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor that reduces glucosylceramide in the brain. J Lipid Res 53:282–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galjaard H (1979) Early diagnosis and prevention of genetic disease. Ann Clin Biochem 16:343–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek RC, Martin DR, Cox NR et al. (2009) Comparative analysis of brain lipids in mice, cats, and humans with Sandhoff disease. Lipids 44:197–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hauser EC, Kasperzyk JL, d’Azzo A et al. (2004) Inheritance of lysosomal acid beta-galactosidase activity and gangliosides in crosses of DBA/2J and knockout mice. Biochem Genet 42:241–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macala LJ, Yu RK, Ando S (1983) Analysis of brain lipids by high performance thin-layer chromatography and densitometry. J Lipid Res 24:1243–1250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seyfried TN, Glaser GH, Yu RK (1979) Genetic variability for regional brain gangliosides in five strains of young mice. Biochem. Genet 17:43–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seyfried TN, Yu RK (1980) Heterosis for brain myelin content in mice. Biochem. Genet 18:1229–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JP, Jeyakumar M, Gonzalez R et al. (2007) Stem cells act through multiple mechanisms to benefit mice with neurodegenerative metabolic disease. Nature medicine 13:439–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denny CA, Heinecke KA, Kim YP et al. (2010) Restricted ketogenic diet enhances the therapeutic action of N-butyldeoxynojirimycin towards brain GM2 accumulation in adult Sandhoff disease mice. J Neurochem 113:1525–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashe KM, Bangari D, Li L et al. (2011) Iminosugar-based inhibitors of glucosylceramide synthase increase brain glycosphingolipids and survival in a mouse model of Sandhoff disease. PloS one 6:e21758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brigande JV, Platt FM, Seyfried TN (1998) Inhibition of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis does not impair growth or morphogenesis of the postimplantation mouse embryo. J. Neurochem 70:871–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Platt FM, Neises GR, Dwek RA et al. (1994) N-butyldeoxynojirimycin is a novel inhibitor of glycolipid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem 269:8362–8365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.