Abstract

Background

Long-term care for patients with chronic diseases poses a huge challenge in primary care. In particular, there is a deficit regarding monitoring and structured follow-up. Appropriate electronic medical records (EMRs) could help improving this but, so far, there are no evidence-based specifications concerning the indicators that should be monitored at regular intervals.

Objective

The aim was to identify and collect a set of evidence-based indicators that could be used for monitoring chronic conditions at regular intervals in primary care using EMRs.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Elsevier), the Cochrane Library (Wiley), the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews, and the content of clinical guidelines. We included primary studies and guidelines reporting about indicators that allow for the assessment of care and help monitor the status and process of disease for five chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, asthma, arterial hypertension, chronic heart failure, and osteoarthritis.

Results

The use of the term “monitoring” in terms of disease management and long-term care for patients with chronic diseases is not widely used in the literature. Nevertheless, we identified a substantial number of disease-specific indicators that can be used for routine monitoring of chronic diseases in primary care by means of EMRs.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review summarizing the existing scientific evidence on the standardized long-term monitoring of chronic diseases using EMRs. In a second step, our extensive set of indicators will serve as a generic template for evaluating their usability by means of an adapted Delphi procedure. In a third step, the indicators will be summarized into a user-friendly EMR layout.

Keywords: monitoring of chronic diseases, indicators, primary care, systematic review, electronic medical record, diabetes mellitus type 2, arterial hypertension, asthma, osteoarthritis, chronic heart failure

Introduction

In 2016, the World Health Organization estimated that 71% of the overall deaths worldwide occurred due to noncommunicable diseases [1]. The majority of these diseases include cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes. In particular, the prevalence of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, asthma, chronic heart failure, and musculoskeletal diseases is increasing rapidly around the world leading to increased multimorbidity and polypharmacy, especially in the older population [1,2]. The burden of these diseases consequently imposes a significant threat to health, quality of life, and economic status in the affected population. Moreover, the regular monitoring of chronic diseases poses huge challenges and requires knowledge and communication skills, as well as the capability of organization and coordination. The chronic care model (CCM) was originally introduced to graphically picture the concept of disease management [3]. The eHealth enhanced chronic care model was subsequently introduced as the means to improve the CCM in view of the progress and development of information and communication technology [4]. This model shows the existing variety of technically well-advanced applications as part of the monitoring process. Too many clinical offices in Switzerland lack basic electronic devices since many general practitioners still use paper-based patient records.

In 2012, 31 European countries were ranked based on the usage of electronic medical records (EMRs) in primary care [5]. In this global ranking of EMR usage, Switzerland ranked number 24. In a Swiss study, only up to 44.8% of the participating primary care physicians reported the usage of EMRs [6]. Therefore, it is currently almost impossible to exchange data with digital applications that are increasingly available and used by patients [6]. To efficiently monitor patients with chronic diseases, a well-structured and organized EMR system is crucial to ensure that all necessary information can be easily entered and retrieved, while no essential information is missed. Surprisingly, there are no evidence-based specifications concerning the indicators that should be monitored at regular intervals. On one hand, there are currently no international standards for the monitoring of patients with chronic diseases by means of EMR in primary care. On the other hand, there are deficits regarding the actual monitoring and structured follow-up. Therefore, we aimed to identify and collect a set of evidence-based indicators that could be used for monitoring patients with chronic conditions at regular intervals in primary care using EMRs.

Methods

Systematic Identification and Assessment of Supporting Evidence

We followed the principles of systematic reviews [7] and developed a protocol a priori to guide the identification and assessment of the monitoring indicators.

Inclusion Criteria

We included clinical guidelines and primary peer-reviewed studies of any design, carried-out mainly in primary care (ie, family health care) patients aged 18 years and older, who were diagnosed with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, asthma, chronic heart failure, or osteoarthritis. The first four diseases are among the most common noninfectious diseases worldwide. Osteoarthritis, in particular, generates a large part of indirect costs [2]. In order to be included, studies must have also reported on indicators that allow the assessment of care and help monitor the status and process of disease for these five chronic conditions. Therefore, we considered disease indicators that help reduce the risk of exacerbation, such as intermediate outcome indicators (eg, hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] for diabetics or blood pressure measurements for hypertensive patients) and process indicators (eg, regular foot care or nutrition counselling). We included studies regardless of whether specific interventions were evaluated. In addition, all studies and clinical guidelines should have been published in English or German.

Search Methods and Study Identification

We developed a comprehensive search strategy in collaboration with an expert librarian. The librarian conducted the search and produced a set of studies that matched the predefined search criteria. We identified studies published between 2000 and 2015 by applying this strategy in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Elsevier), and the Cochrane Library (Wiley). No restrictions were made regarding the country of origin of the studies. The search strategy included a combination of the concepts and terminology, synonyms and related words for monitoring and for medical, health, electronic, patient, or file records. It also included primary, family, health care, or general practitioner, and the five chronic conditions (ie, type 2 [non-insulin-dependent] diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, asthma, chronic heart failure, and osteoarthritis). The focused search also included the terminology indicators, parameter, and management. An example of the full search strategy is available in Multimedia Appendix 1.

We identified additional publications by manually searching the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews. We also searched for monitoring indicators in the clinical guidelines in order to identify as many indicators as possible and to enable a holistic management of chronic diseases. Given that most guidelines are not indexed in the former medical literature databases, and to identify the clinical guidelines related to any of the five chronic diseases, we searched World Wide Web-based databases, including the National Guideline Clearinghouse for US guidelines [8] and the Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften eV (AWMF) [9] for German guidelines.

Study Selection and Assessment

For study selection, we created a system to prioritize the studies. One reviewer identified eligible studies by first screening the titles and abstracts of all records retrieved by the searches based on the inclusion criteria. All potentially eligible abstracts were rated manually from one to five stars according to their relevance for this review. The stars were assigned based on whether or not the key terms were mentioned (ie, “indicator,” “monitoring,” “assessment,” “management,” and/or “guideline”). The ranking was assigned as follows:

One star: Remote reference to the key terms; no indicators expected in full text.

Two stars: Little reference to the key terms; indicators in full text unlikely.

Three stars: Reference of at least one key term; indicators in full text possible.

Four stars: Reference of at least one key term; indicators in full text very possible.

Five stars: Reference of indicators, monitoring, or interval of measuring indicators.

The full text of all studies with an abstract that was rated with at least two stars was obtained, if available, and further evaluated based on the reporting of indicators. For studies where the full text was not available but were deemed important to inform our monitoring tool, we used the data reported in the abstract. When it was necessary, the study team was consulted throughout the evaluation process to confirm the eligibility of indicators.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each included study, we extracted the bibliographic details (ie, author, year, and country of origin), all the monitoring indicators reported, the guideline on which the indicators were based, and the country of origin of the guidelines for each of the five chronic diseases. One reviewer extracted all data, and another reviewer verified the extracted data. We compiled a data profile for each study or guideline, and generated a set of indicators using Microsoft Excel. We report a descriptive summary of the indicators for each of the chronic conditions.

Results

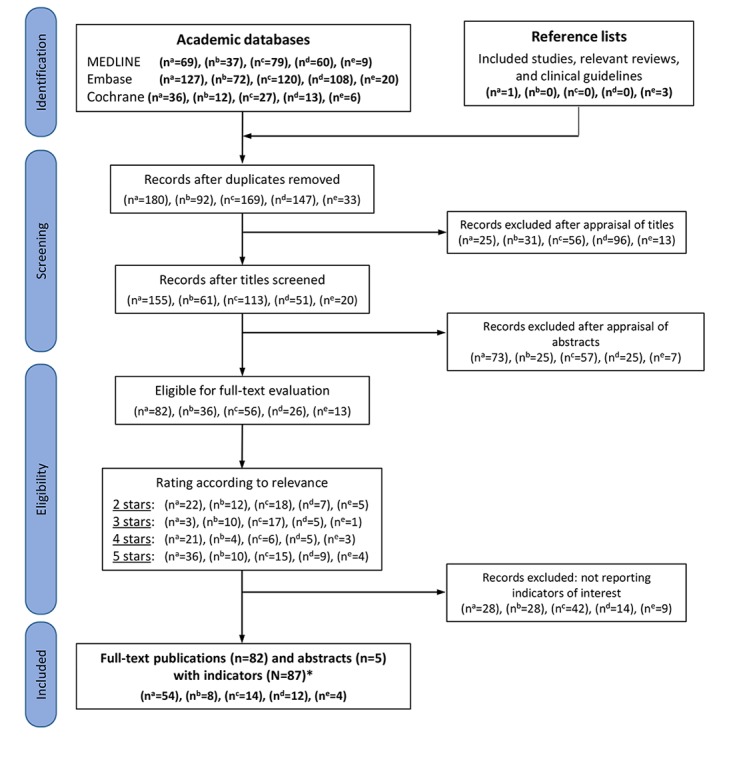

Our literature searches identified 795 original records (see Figure 1). After deduplication and perusal of titles and abstracts, we screened 621 records (range by disease: 33-180) and excluded 408 records that did not meet our inclusion criteria (eg, focused on specific therapy or medication or did not cover the topic). We examined in detail the full text, where available, of 213 publications (range by disease: 13 to 82).

Figure 1.

Flowchart demonstrating the identification and selection of evidence. a: type 2 diabetes mellitus; b: asthma; c: arterial hypertension; d: heart failure; e: osteoarthritis; *: 5 of 87 publications (6%) reported indicators for more than one disease of interest.

We included 87 original publications, 5 (6%) in abstract form only, reporting indicators for diabetes mellitus [10-63], asthma [60,64-70], arterial hypertension [10,35,39,71-81], heart failure [33,82-92], and osteoarthritis [93-96]. Multimedia Appendix 2 presents a list of all included studies that reported monitoring indicators for the five chronic conditions. A total of 5 publications (6%) reported indicators for more than one chronic disease [10,33,35,39,60]. The number of included publications by disease with at least one indicator ranged from 4 to 54. Most records (54/87, 62%) were published on type 2 diabetes mellitus, while osteoarthritis was the most underrepresented of the five diseases, with only 4 records (5%). A total of 74 of all 87 included studies (85%) contained process indicators, the most significant type of indicators. Concerning diabetes mellitus, a third of all publications (54/179, 30.2%) reported at least one indicator. For arterial hypertension and heart failure, only 8% (7/87) of all publications reported at least one indicator. Overall, most records used guidelines from the United States, followed by the United Kingdom. For diabetes mellitus, the American Diabetes Association and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence were the most-used guidelines. The most frequently mentioned indicators for diabetes are presented in Table 1. The indicators for the other four diseases are presented in Multimedia Appendices 3-6.

Table 1.

Diabetes mellitus indicators that are most frequently mentioned in guidelines and studies. The indicators are sorted first by guidelines and then by studies.

| Indicators for diabetes mellitus | Number of guidelines where indicators are mentioned (guidelines) | Number of studies where indicators are mentioned |

| Fundoscopic examination | 7 (a-g)a | 20 [10,12,13,18,21,23,25,30-32,41,43-46,50-52,60,61] |

| Height, weight, and body mass index | 7 (a-g) | 33 [11-16,18,20,21,23-25,27-29,32,33,35,40,41,44,45,48, 49,53-56,58-60,62,63] |

| Blood pressure measurement | 7 (a-g) | 45 [11,13,15-27,29-36,39-45,47-49,52,53,55,56,58-63] |

| 10 g monofilament | 7 (a-g) | N/Ab |

| Hemoglobin A1c (ie, glycated hemoglobin) | 7 (a-g) | 46 [10,12,13,15-23,26,28-37,39-45,47-54,56-63] |

| Foot inspection | 7 (a-g) | 17 [12,15,18,21,23,25,30-32,43-46,50-52,61] |

| Erectile dysfunction | 7 (a-g) | N/A |

| Albuminuria | 7 (a-g) | 18 [12,13,18,22,23,25,31,32,35,41,43-46,51,55,61,62] |

| Lipid profile | 7 (a-g) | 8 [25,26,30,43,45,46,52,61] |

| Low-density lipoprotein | N/A | 30 [11,12,15,18-20,22-24,29,31-37,41-44,47-49,52-54,63] |

| High-density lipoprotein | N/A | 14 [11,20,23,28,29,33,37,39,49,51,53,54,62,63] |

| Triglyceride | N/A | 15 [20,29,30,33,37,39,48,49,51,53-55,57,62,63] |

| Creatinine | 7 (a-g) | 18 [13,15,16,22,25-27,29,33,41,46,51,55,57-60,62] |

| Alcohol intake | 7 (a-g) | 2 [24,53] |

| Neuropathy and history of foot lesion | 7 (a-g) | 3 [18,20,55] |

| History of myocardial infarction (ie, cardiovascular disease) | 6 (a-f) | 2 [18,22] |

| Foot pulses | 6 (a-f) | 3 [18,32,60] |

| Smoking status | 6 (a-f) | 24 [11-15,18,20,22-24,26,28,29,31,35,41,44,48,50,53, 58-61] |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 5 (a, b, d, e, g) | N/A |

| Skin inspection | 5 (a, b, d, f, g) | N/A |

| Vibration by 128 Hz tuning fork | 5 (a-d, g) | 1 [60] |

| Plasma glucosis | 4 (b-d, g) | 12 [11,21,24,33,39,45,51,54,55,57,59,63] |

| Onset of diabetes | 3 (b, c, f) | 9 [11,18,22,23,28,48,55,58,59] |

| Indicators appeared in fewer than five guidelines | 225 | N/A |

| Indicators appeared in fewer than 10 studies | N/A | 76 |

aThe letters a-g refer to the guidelines listed in Multimedia Appendices 7-11.

bN/A: not applicable.

In total, there were 249 indicators for type 2 diabetes mellitus, 183 for asthma, 335 for arterial hypertension, 231 for chronic heart failure, and 164 for osteoarthritis. The majority of indicators were identified by screening both peer-reviewed articles and clinical guidelines. A few extra indicators were reported only in peer-reviewed articles. That is, clinical guidelines on their own contributed to the great majority of all indicators identified. Surprisingly, only a few guidelines, such as the American guideline for asthma, included a section dedicated to monitoring or follow-up. Most of the guidelines that we screened did not specify the interval at which the indicators should be monitored. Also, in some guidelines, self-monitoring was a big topic for chronic heart disease (ie, weight control), asthma (ie, peak expiratory flow), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (ie, glucose monitoring).

Our systematic review also found that the term “monitoring,” in the sense of long-term patient care, was not widely used. Although publications reported the actual monitoring indicators, the process of monitoring for the different diseases, including, for example, the potential risks associated with overmonitoring, was only scarcely addressed. The publication by Glasziou was the only one giving a broader overview on the topic [97]. Only a handful of publications reported a complete set of indicators that can be used for monitoring, but these were either not specific for primary care or not eligible for implementation in EMRs [98-101].

Discussion

Principal Findings

To our knowledge, this study represents the first summary of the existing scientific evidence about the indicators that help standardize the monitoring of chronically ill patients in primary care by the use of EMRs. Long-term care of patients with chronic diseases is challenging and there are deficits regarding their monitoring and structured follow-up. Chronic care often involves collaboration between several people involved in the treatment process. That is only one reason for its complexity. Interpersonal differences in monitoring can decrease the quality of monitoring processes. Surprisingly, there are currently no gold standards or consensus regarding the systematic monitoring of patients with chronic diseases, in particular by means of EMRs. To efficiently monitor patients with chronic diseases, a well-structured and organized EMR system is crucial to ensure that all necessary information can be easily entered and retrieved and that no essential information is missed. Our study is, thus, the first initiative toward the urgent need of standardization for monitoring patients with chronic diseases in primary care.

Our systematic literature review showed that the term “monitoring” in terms of disease management and long-term patient care is not widely used. There is a plethora of literature about quality indicators that might have the potential to improve the outcome of a disease. The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in the United Kingdom, for example, assesses indicators for such purposes [102]. Beyond identifying indicators that can be easily assessed, such as the indicators used by the QOF, our goal was to summarize the existing literature on all the indicators available for long-term monitoring.

So far, only a few authors have focused on the topic of the monitoring of chronic diseases. According to Glasziou, the process of monitoring aims to establish the response to treatment and to detect both adverse effects and the need to adjust treatment [97]. The process of monitoring can be divided into different phases (ie, pretreatment, during treatment, and after treatment). Each phase requires measurements at different intervals.

When analyzing different diseases, monitoring is probably most widely mentioned in blood pressure management. There are various publications reporting on the optimal way and interval of measuring blood pressure [76,103,104]. However, literature beyond the indicator of blood pressure measurement remains scarce. Regarding diabetes mellitus, there is an extended monitoring tool that was designed as a disease management tool for practice nurses [101]. The tool’s design is based on a traffic light scheme to detect any deficit and need for action. In addition, a detailed guideline on how to monitor the diabetic foot is provided by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot [105]. As for bronchial asthma, two study groups have addressed the optimal way and potential problems of finding and evaluating indicators to monitor patients with asthma, including an overview of the most important indicators [98,100]. Similarly, Grypdonck presents a small set of indicators for monitoring patients with osteoarthritis of the knee [93]. Self-monitoring seems to be an important topic concerning osteoarthritis and asthma. An English study conducted by interviewing general practitioners about osteoarthritis showed that the majority of respondents thought monitoring of osteoarthritis is important, even though almost half did not monitor patients at all. Interestingly, more than half of the respondents felt that patients should do self-monitoring [106]. Patient involvement is crucial for monitoring. Particularly, in high-frequency monitoring situations such as chronic heart failure, telecardiological service, including transtelephonic monitoring, reduces the length of hospitalization and improves quality of life [91]. Surprisingly, publications concerning monitoring of chronic heart failure seem to be scarce [90]. The underrepresentation of osteoarthritis and chronic heart failure is also reflected in the number of indicators detected in the primary literature, compared to a large number of records reporting on indicators for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Another topic repeatedly found in the results was the involvement of a clinical practice nurse in monitoring [101,107-109]. The clinical nurse can, for example, fill out a monitoring questionnaire in face-to-face sessions with the patient, on the phone, or even electronically. This could counteract the problem of workload and time constraints as a frequent response to why monitoring is not conducted [106].

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this study represents the first scientifically founded recommendation for the standardized long-term monitoring of chronically ill patients in primary care. Usually, systematic reviews only concentrate on primary literature and do not include guidelines in their search strategy, since most guidelines are not indexed in databases. In our study, we explicitly searched for guideline programs such as the National Guideline Clearinghouse for American guidelines and the AWMF for German guidelines. We added a substantial number of manual searches within reference lists and search engines in order to gain a maximal insight of the existing literature. This strategy was worth the extra effort, considering that most relevant indicators were found in guidelines and not in the primary literature. Possible confounders are that publications and guidelines reported in languages other than German and English were excluded.

Outlook

In a second step, our extensive set of indicators obtained from this work will serve as a generic template for a monitoring tool. By means of an adapted Delphi procedure, the indicators will be further evaluated in terms of their usability. In a third step, the indicators will be summarized into a user-friendly EMR layout.

Conclusion

This is the first study that systematically summarizes the existing scientific evidence about the standardized long-term monitoring of chronic diseases by means of EMRs. It aims to help improve care for patients with chronic diseases in primary care.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Martina Gosteli for her assistance with the search strategy. This project was funded by the Institut für Praxisinformatik, mandated by the Swiss Medical Association FMH.

Abbreviations

- AWMF

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften eV

- CCM

chronic care model

- EMR

electronic medical record

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- QOF

Quality and Outcomes Framework

Search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Elsevier), and the Cochrane Library (Wiley).

List of all included studies, including monitoring indicators for the five chronic conditions.

Asthma indicators mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Arterial hypertension indicators mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Chronic heart failure indicators most frequently mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Osteoarthritis indicators most frequently mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Guidelines screened for indicators for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Guidelines screened for indicators for asthma.

Guidelines screened for indicators for arterial hypertension.

Guidelines screened for indicators for chronic heart failure.

Guidelines screened for indicators for osteoarthritis.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: LF was involved in designing the search strategy, performing the systematic screening and review of the literature, and writing of the manuscript. MZ was involved in study design and revised the manuscript. NAMG contributed to the study design and search strategy; NAMG also revised and improved the manuscript. TR supervised the development and methodology of the study and helped improve the final version of the manuscript. CC was involved in the study design, study selection, and prioritization; CC also verified the extracted data, and supervised and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring Health for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. [2019-05-14]. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2016/Annex_B/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann N, Burla L, Kohler D, Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium . Gesundheit in der Schweiz: Fokus Chronische Erkrankungen. Nationaler Gesundheitsbericht 2015. Bern, Switzerland: Hogrefe Verlag; 2015. [2019-05-13]. https://www.obsan.admin.ch/sites/default/files/publications/2015/gesundheitsbericht_2015_d.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gee PM, Greenwood DA, Paterniti DA, Ward D, Miller LM. The eHealth Enhanced Chronic Care Model: A theory derivation approach. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Apr 01;17(4):e86. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4067. http://www.jmir.org/2015/4/e86/ v17i4e86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Rosis S, Seghieri C. Basic ICT adoption and use by general practitioners: An analysis of primary care systems in 31 European countries. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015 Aug 22;15:70. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0185-z. https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-015-0185-z .10.1186/s12911-015-0185-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djalali S, Ursprung N, Rosemann T, Senn O, Tandjung R. Undirected health IT implementation in ambulatory care favors paper-based workarounds and limits health data exchange. Int J Med Inform. 2015 Nov;84(11):920–932. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.08.001.S1386-5056(15)30025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger M, Smith GD. Principles of and procedures for systematic reviews. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta‐Analysis in Context. 2nd edition. London, UK: BMJ Publishing Group; 2008. pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. National Guideline Clearinghouse https://www.guideline.gov/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.AWMF Das Portal der wissenschaftlichen Medizin. Leitliniensuche http://www.awmf.org .

- 10.Suija K, Kivisto K, Sarria-Santamera A, Kokko S, Liseckiene I, Bredehorst M, Jaruseviciene L, Papp R, Oona M, Kalda R. Challenges of audit of care on clinical quality indicators for hypertension and type 2 diabetes across four European countries. Fam Pract. 2015 Feb;32(1):69–74. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu078.cmu078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah AD, Langenberg C, Rapsomaniki E, Denaxas S, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Gale CP, Deanfield J, Smeeth L, Timmis A, Hemingway H. Type 2 diabetes and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: A cohort study in 1·9 million people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Feb;3(2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70219-0. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213-8587(14)70219-0 .S2213-8587(14)70219-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devkota BP, Ansstas M, Scherrer JF, Salas J, Budhathoki C. Internal medicine resident training and provision of diabetes quality of care indicators. Can J Diabetes. 2015 Apr;39(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.10.001.S1499-2671(14)00626-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barkhuysen P, de Grauw W, Akkermans R, Donkers J, Schers H, Biermans M. Is the quality of data in an electronic medical record sufficient for assessing the quality of primary care? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):692–698. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001479. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24145818 .amiajnl-2012-001479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szczech LA, Stewart RC, Su H, DeLoskey RJ, Astor BC, Fox CH, McCullough PA, Vassalotti JA. Primary care detection of chronic kidney disease in adults with type-2 diabetes: The ADD-CKD Study (awareness, detection and drug therapy in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease) PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e110535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110535. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110535 .PONE-D-14-21749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Melle MA, Lamkaddem M, Stuiver MM, Gerritsen AA, Devillé WL, Essink-Bot ML. Quality of primary care for resettled refugees in the Netherlands with chronic mental and physical health problems: A cross-sectional analysis of medical records and interview data. BMC Fam Pract. 2014 Sep 23;15:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-160. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2296-15-160 .1471-2296-15-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Djalali S, Frei A, Tandjung R, Baltensperger A, Rosemann T. Swiss quality and outcomes framework: Quality indicators for diabetes management in Swiss primary care based on electronic medical records. Gerontology. 2014;60(3):263–273. doi: 10.1159/000357370.000357370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goff SL, Murphy L, Knee AB, Guhn-Knight H, Guhn A, Lindenauer PK. Effects of an enhanced primary care program on diabetes outcomes. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Mar 01;23(3):e75–e81. https://www.ajmc.com/pubMed.php?pii=87029 .87029 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vidal-Pardo JI, Pérez-Castro TR, López-Álvarez XL, Santiago-Pérez MI, García-Soidán FJ, Muñiz J. Effect of an educational intervention in primary care physicians on the compliance of indicators of good clinical practice in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus [OBTEDIGA project] Int J Clin Pract. 2013 Aug;67(8):750–758. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sidorenkov G, Voorham J, de Zeeuw D, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Denig P. Treatment quality indicators predict short-term outcomes in patients with diabetes: A prospective cohort study using the GIANTT database. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Apr;22(4):339–347. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001203.bmjqs-2012-001203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkley K, Thomas SM, Sivaprasad S, Chamley M, Stahl D, Ismail K, Amiel SA. The clinical characteristics at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in a multi-ethnic population: The South London Diabetes cohort (SOUL-D) Diabetologia. 2013 Jun;56(6):1272–1281. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavran L, Zildzic M, Batic-Mujanovic O, Alic A, Gledo I, Prasko S. Auditing of medical chart among type 2 diabetic patient done by primary care physicians. Med Arch. 2012;66(6):388–390. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2012.66.388-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knudsen ST, Mosbech TH, Hansen B, Kønig E, Johnsen PC, Kamper A. Screening for microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes is incomplete in general practice. Dan Med J. 2012 Sep;59(9):A4502.A4502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mata-Cases M, Roura-Olmeda P, Berengué-Iglesias M, Birulés-Pons M, Mundet-Tuduri X, Franch-Nadal J, Benito-Badorrey B, Cano-Pérez JF, Diabetes Study Group in Primary Health Care (GEDAPS: Grup d’Estudi de la Diabetis a l’Atenció Primària de Salut‚ Catalonian Society of Family and Community Medicine) Fifteen years of continuous improvement of quality care of type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care in Catalonia, Spain. Int J Clin Pract. 2012 Mar;66(3):289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02872.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nouwens E, van Lieshout J, Wensing M. Comorbidity complicates cardiovascular treatment: Is diabetes the exception? Neth J Med. 2012 Sep;70(7):298–305. http://www.njmonline.nl/njm/getarticle.php?v=70&i=7&p=298 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satman I, Imamoglu S, Yilmaz C, ADMIRE Study Group A patient-based study on the adherence of physicians to guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes in Turkey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012 Oct;98(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.003.S0168-8227(12)00164-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marley JV, Nelson C, O'Donnell V, Atkinson D. Quality indicators of diabetes care: An example of remote-area Aboriginal primary health care over 10 years. Med J Aust. 2012 Oct 01;197(7):404–408. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10275.10.5694/mja12.10275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patapas JM, Blanchard AC, Iqbal S, Vasilevsky M, Dannenbaum D. Management of aboriginal and nonaboriginal people with chronic kidney disease in Quebec: Quality-of-care indicators. Can Fam Physician. 2012 Feb;58(2):e107–e111. http://www.cfp.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=22439172 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staff M. Can data extraction from general practitioners' electronic records be used to predict clinical outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes? Inform Prim Care. 2012;20(2):95–102. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v20i2.30. http://hijournal.bcs.org/index.php/jhi/article/view/30 .30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill F, Bradley C. A computer based, automated analysis of process and outcomes of diabetic care in 23 GP practices. Ir Med J. 2012 Feb;105(2):45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alfadda AA, Bin-Abdulrahman KA, Saad HA, Mendoza CD, Angkaya-Bagayawa FF, Yale JF. Effect of an intervention to improve the management of patients with diabetes in primary care practice. Saudi Med J. 2011 Jan;32(1):36–40.0' [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickerson LM, Ables AZ, Everett CJ, Mainous AG, McCutcheon AM, Bazaldua OV, Weber CA, Carter BL, National Interdisciplinary Primary Care Practice-Based Research Network Measuring diabetes care in the national interdisciplinary primary care practice-based research network (NIPC-PBRN) Pharmacotherapy. 2011 Jan;31(1):23–30. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.1.23.10.1592/phco.31.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vidal Pardo JI, Pérez Castro TR, López Álvarez XL, García Soidán FJ, Santiago Pérez MI, Muñiz J. Quality of care of patients with type-2 diabetes in Galicia (NW Spain) [OBTEDIGA project] Int J Clin Pract. 2011 Oct;65(10):1067–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weenink J, van Lieshout J, Jung HP, Wensing M. Patient care teams in treatment of diabetes and chronic heart failure in primary care: An observational networks study. Implement Sci. 2011 Jul 03;6:66. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-66. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-6-66 .1748-5908-6-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gladstone J, Howard M. Effect of advanced access scheduling on chronic health care in a Canadian practice. Can Fam Physician. 2011 Jan;57(1):e21–e25. http://www.cfp.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21252121 .57/1/e21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holbrook A, Pullenayegum E, Thabane L, Troyan S, Foster G, Keshavjee K, Chan D, Dolovich L, Gerstein H, Demers C, Curnew G. Shared electronic vascular risk decision support in primary care: Computerization of Medical Practices for the Enhancement of Therapeutic Effectiveness (COMPETE III) randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Oct 24;171(19):1736–1744. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.471.171/19/1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JM, Rush WA, Johnson PE, Amundson GH, Asche SE, Ekstrom HL, Gilmer TP. Impact of electronic health record clinical decision support on diabetes care: A randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(1):12–21. doi: 10.1370/afm.1196. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21242556 .9/1/12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sundquist K, Chaikiat A, León VR, Johansson S, Sundquist J. Country of birth, socioeconomic factors, and risk factor control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A Swedish study from 25 primary health-care centres. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011 Mar;27(3):244–254. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reddy P, Philpot B, Ford D, Dunbar JA. Identification of depression in diabetes: The efficacy of PHQ-9 and HADS-D. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 Jun;60(575):e239–e245. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X502128. http://bjgp.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20529487 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samoutis GA, Soteriades ES, Stoffers HE, Philalithis A, Delicha EM, Lionis C. A pilot quality improvement intervention in patients with diabetes and hypertension in primary care settings of Cyprus. Fam Pract. 2010 Jun;27(3):263–270. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq009.cmq009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah BR, Bhattacharyya O, Yu C, Mamdani M, Parsons JA, Straus SE, Zwarenstein M. Evaluation of a toolkit to improve cardiovascular disease screening and treatment for people with type 2 diabetes: Protocol for a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. Trials. 2010 Apr 23;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-44. https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1745-6215-11-44 .1745-6215-11-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrazzuoli F, Soler JK, Buono N, Dobbs F. Quality of care for hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes in a rural area of Southern Italy: Is the recording of patient data and the achievement of quality indicators targets satisfactory? Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1258. http://www.rrh.org.au/articles/subviewnew.asp?ArticleID=1258 .1258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sperl-Hillen JM, O'Connor PJ, Rush WA, Johnson PE, Gilmer T, Biltz G, Asche SE, Ekstrom HL. Simulated physician learning program improves glucose control in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010 Aug;33(8):1727–1733. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0439. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20668151 .dc10-0439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen ML. Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Greenland, 2008: Examining the quality and organization of diabetes care. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009 Apr;68(2):123–132. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i2.18322.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holbrook A, Thabane L, Keshavjee K, Dolovich L, Bernstein B, Chan D, Troyan S, Foster G, Gerstein H, COMPETE II Investigators Individualized electronic decision support and reminders to improve diabetes care in the community: COMPETE II randomized trial. CMAJ. 2009 Jul 07;181(1-2):37–44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081272. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19581618 .181/1-2/37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moharram MM, Farahat FM. Quality improvement of diabetes care using flow sheets in family health practice. Saudi Med J. 2008 Jan;29(1):98–101.20070760' [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novo A, Jokić I. Medical audit of diabetes mellitus in primary care setting in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croat Med J. 2008 Dec;49(6):757–762. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.49.757. http://www.cmj.hr/2008/49/6/19090600.htm . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samuels TA, Bolen S, Yeh HC, Abuid M, Marinopoulos SS, Weiner JP, McGuire M, Brancati FL. Missed opportunities in diabetes management: A longitudinal assessment of factors associated with sub-optimal quality. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Nov;23(11):1770–1777. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0757-z. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18787908 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith SA, Shah ND, Bryant SC, Christianson TJ, Bjornsen SS, Giesler PD, Krause K, Erwin PJ, Montori VM, Evidens Research Group Chronic care model and shared care in diabetes: Randomized trial of an electronic decision support system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008 Jul;83(7):747–757. doi: 10.4065/83.7.747.S0025-6196(11)60913-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voorham J, Denig P, Wolffenbuttel BH, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Cross-sectional versus sequential quality indicators of risk factor management in patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Care. 2008 Feb;46(2):133–141. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815b9da0.00005650-200802000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wens J, Dirven K, Mathieu C, Paulus D, Van Royen P, Belgian Diabetes Project Group Quality indicators for type-2 diabetes care in practice guidelines: An example from six European countries. Prim Care Diabetes. 2007 Feb;1(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2006.07.001.S1751-9918(06)00003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nitiyanant W, Chetthakul T, Sang-A-kad P, Therakiatkumjorn C, Kunsuikmengrai K, Yeo JP. A survey study on diabetes management and complication status in primary care setting in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007 Jan;90(1):65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herrin J, Nicewander DA, Hollander PA, Couch CE, Winter FD, Haydar ZR, Warren SS, Ballard DJ. Effectiveness of diabetes resource nurse case management and physician profiling in a fee-for-service setting: A cluster randomized trial. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2006 Apr;19(2):95–102. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2006.11928137. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16609732 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wan Q, Harris MF, Jayasinghe UW, Flack J, Georgiou A, Penn DL, Burns JR. Quality of diabetes care and coronary heart disease absolute risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Australian general practice. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Apr;15(2):131–135. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.014845. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16585115 .15/2/131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al Khaja KA, Sequeira RP, Damanhori AH. Comparison of the quality of diabetes care in primary care diabetic clinics and general practice clinics. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005 Nov;70(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.03.029.S0168-8227(05)00123-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cueto-Manzano AM, Cortes-Sanabria L, Martinez-Ramirez HR, Rojas-Campos E, Barragan G, Alfaro G, Flores J, Anaya M, Canales-Munoz JL. Detection of early nephropathy in Mexican patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005 Aug;(97):S40–S45. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09707.x. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0085-2538(15)51247-7 .S0085-2538(15)51247-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lusignan S, Sismanidis C, Carey IM, DeWilde S, Richards N, Cook DG. Trends in the prevalence and management of diagnosed type 2 diabetes 1994-2001 in England and Wales. BMC Fam Pract. 2005 Mar 22;6(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-13. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2296-6-13 .1471-2296-6-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sequeira RP, Al Khaja KA, Damanhori AH. Evaluating the treatment of hypertension in diabetes mellitus: A need for better control? J Eval Clin Pract. 2004 Feb;10(1):107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00404.x.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wermeille J, Bennie M, Brown I, McKnight J. Pharmaceutical care model for patients with type 2 diabetes: Integration of the community pharmacist into the diabetes team--A pilot study. Pharm World Sci. 2004 Feb;26(1):18–25. doi: 10.1023/b:phar.0000013465.24857.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goudswaard AN, Lam K, Stolk RP, Rutten GE. Quality of recording of data from patients with type 2 diabetes is not a valid indicator of quality of care: A cross-sectional study. Fam Pract. 2003 Apr;20(2):173–177. doi: 10.1093/fampra/20.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campbell SM, Hann M, Hacker J, Durie A, Thapar A, Roland MO. Quality assessment for three common conditions in primary care: Validity and reliability of review criteria developed by expert panels for angina, asthma and type 2 diabetes. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002 Jun;11(2):125–130. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.125. http://qhc.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12448803 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parchman ML, Burge SK, Residency Research Network of South Texas Investigators Continuity and quality of care in type 2 diabetes: A Residency Research Network of South Texas study. J Fam Pract. 2002 Jul;51(7):619–624.jfp_0702_00619 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Renders CM, Valk GD, Franse LV, Schellevis FG, van Eijk JT, van der Wal G. Long-term effectiveness of a quality improvement program for patients with type 2 diabetes in general practice. Diabetes Care. 2001 Aug;24(8):1365–1370. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Linmans JJ, Spigt MG, Deneer L, Lucas AE, de Bakker M, Gidding LG, Linssen R, Knottnerus JA. Effect of lifestyle intervention for people with diabetes or prediabetes in real-world primary care: Propensity score analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2011 Sep 13;12:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-95. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2296-12-95 .1471-2296-12-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Minard JP, Dostaler SM, Taite AK, Olajos-Clow JG, Sands TW, Licskai CJ, Lougheed MD. Development and implementation of an electronic asthma record for primary care: Integrating guidelines into practice. J Asthma. 2014 Feb;51(1):58–68. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.845206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lim KG, Rank MA, Cabanela RL, Furst JW, Rohrer JE, Liesinger J, Muller L, Wagie AE, Naessens JM. The asthma ePrompt: A novel electronic solution for chronic disease management. J Asthma. 2012 Mar;49(2):213–218. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.654419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lougheed MD, Minard J, Dworkin S, Juurlink M, Temple WJ, To T, Koehn M, Van Dam A, Boulet L. Pan-Canadian REspiratory STandards INitiative for Electronic Health Records (PRESTINE): 2011 national forum proceedings. Can Respir J. 2012;19(2):117–126. doi: 10.1155/2012/870357. doi: 10.1155/2012/870357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oei SM, Thien FC, Schattner RL, Sulaiman ND, Birch K, Simpson P, Del Colle EA, Aroni RA, Wolfe R, Abramson MJ. Effect of spirometry and medical review on asthma control in patients in general practice: A randomized controlled trial. Respirology. 2011 Jul;16(5):803–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nokela M, Arnlind MH, Ehrs P, Krakau I, Forslund L, Jonsson EW. The influence of structured information and monitoring on the outcome of asthma treatment in primary care: A cluster randomized study. Respiration. 2010;79(5):388–394. doi: 10.1159/000235548. https://www.karger.com?DOI=10.1159/000235548 .000235548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yawn BP, Bertram S, Wollan P. Introduction of Asthma APGAR tools improve asthma management in primary care practices. J Asthma Allergy. 2008 Aug 31;1:1–10. doi: 10.2147/jaa.s3595. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21436980 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baddar S, Worthing EA, Al-Rawas OA, Osman Y, Al-Riyami BM. Compliance of physicians with documentation of an asthma management protocol. Respir Care. 2006 Dec;51(12):1432–1440. http://www.rcjournal.com/contents/12.06/12.06.1432.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hasselström J, Zarrinkoub R, Holmquist C, Hjerpe P, Ljungman C, Qvarnström M, Wettermark B, Manhem K, Kahan T, Bengtsson Boström K. The Swedish Primary Care Cardiovascular Database (SPCCD): 74 751 hypertensive primary care patients. Blood Press. 2014 Apr;23(2):116–125. doi: 10.3109/08037051.2013.814829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tong SF, Khoo EM, Nordin S, Teng C, Lee VK, Zailinawati AH, Chen WS, Mimi O. Process of care and prescribing practices for hypertension in public and private primary care clinics in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012 Sep;24(5):764–775. doi: 10.1177/1010539511402190.1010539511402190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pavlik VN, Greisinger AJ, Pool J, Haidet P, Hyman DJ. Does reducing physician uncertainty improve hypertension control?: Rationale and methods. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009 May;2(3):257–263. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.849984. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20031846 .2/3/257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chan PF, Chao DVK. The Hong Kong Practictioner. 2006. Dec, [2019-05-13]. An audit on management of hypertension in a hospital authority general outpatient clinic http://www.hkcfp.org.hk/Upload/HK_Practitioner/2006/hkp2006vol28dec/original_article.html .

- 75.Asnani M, Brown P, O'Connor D, Lewis T, Win S, Reid M. A clinical audit of the quality of care of hypertension in general practice. West Indian Med J. 2005 Jun;54(3):176–180. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442005000300004.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rabinowitz I, Tamir A. The SaM (Screening and Monitoring) approach to cardiovascular risk-reduction in primary care: Cyclic monitoring and individual treatment of patients at cardiovascular risk using the electronic medical record. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005 Feb;12(1):56–62.00149831-200502000-00009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mitchell E, Sullivan F, Grimshaw JM, Donnan PT, Watt G. Improving management of hypertension in general practice: A randomised controlled trial of feedback derived from electronic patient data. Br J Gen Pract. 2005 Feb;55(511):94–101. http://bjgp.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15720929 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alli C, Mariotti G, Avanzini F, Colombo F, Barlera S, Tognoni G, Studio sulla Pressione Arteriosa nell'Anziano (SPAA) Long-term prognostic impact of repeated measurements over 1 year of pulse pressure and systolic blood pressure in the elderly. J Hum Hypertens. 2005 May;19(5):355–363. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001827.1001827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tierney WM, Brunt M, Kesterson J, Zhou X, L'Italien G, Lapuerta P. Quantifying risk of adverse clinical events with one set of vital signs among primary care patients with hypertension. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(3):209–217. doi: 10.1370/afm.76. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15209196 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lackland DT, Lin Y, Tilley BC, Egan BM. An assessment of racial differences in clinical practices for hypertension at primary care sites for medically underserved patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2004 Jan;6(1):26–31; quiz 32. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.03089.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1524-6175&date=2004&volume=6&issue=1&spage=26 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frijling BD, Lobo CM, Hulscher ME, Akkermans RP, van Drenth BB, Prins A, van der Wouden JC, Grol RP. Intensive support to improve clinical decision making in cardiovascular care: A randomised controlled trial in general practice. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003 Jun;12(3):181–187. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.3.181. http://qhc.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12792007 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amarasingham R, Patel PC, Toto K, Nelson LL, Swanson TS, Moore BJ, Xie B, Zhang S, Alvarez KS, Ma Y, Drazner MH, Kollipara U, Halm EA. Allocating scarce resources in real-time to reduce heart failure readmissions: A prospective, controlled study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Dec;22(12):998–1005. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001901. http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=23904506 .bmjqs-2013-001901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Logeart D, Isnard R, Resche-Rigon M, Seronde M, de Groote P, Jondeau G, Galinier M, Mulak G, Donal E, Delahaye F, Juilliere Y, Damy T, Jourdain P, Bauer F, Eicher J, Neuder Y, Trochu J, Heart Failure of the French Society of Cardiology Current aspects of the spectrum of acute heart failure syndromes in a real-life setting: The OFICA study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013 Apr;15(4):465–476. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs189. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs189.hfs189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lind L, Klompstra L, Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. Implementation and testing of a digital pen and paper tool to support patients with heart failure and their health care providers in detecting early signs of deterioration and monitor adherence. Int J Integr Care. 2011 Jul 21;11(7):e115. doi: 10.5334/ijic.787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maddocks H, Marshall JN, Stewart M, Terry AL, Cejic S, Hammond J, Jordan J, Chevendra V, Denomme LB, Thind A. Quality of congestive heart failure care: Assessing measurement of care using electronic medical records. Can Fam Physician. 2010 Dec;56(12):e432–e437. http://www.cfp.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21156884 .56/12/e432 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Korb K, Hummers-Pradier E, Stich K, Chenot J, Scherer M. Implementation of recommendations for the diagnosis of heart failure. [corrected] [Article in German] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2010 Jan;135(4):120–124. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Heywood JT, McBride ML, Inge PJ, Mehra MR, O'Connor CM, Reynolds D, Walsh MN, Yancy CW. Improving evidence-based care for heart failure in outpatient cardiology practices: Primary results of the Registry to Improve the Use of Evidence-Based Heart Failure Therapies in the Outpatient Setting (IMPROVE HF) Circulation. 2010 Aug 10;122(6):585–596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934471.CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vercauteren S, Castadot M, Vanhalewyn M, Boulanger S, Robert A, Bouvy C, Colpaert D, Sbaysi S, Zanelli G, Col J. BELGIUM-HF (Better Efficacy in Lowering events by General practitioner's Intervention Using remote Monitoring in Heart Failure): Concept and feasibility. Proceedings of the Belgian Society of Cardiology, 28th Annual Scientific Meeting; Belgian Society of Cardiology, 28th Annual Scientific Meeting; January 29-31, 2009; Brussels, Belgium. 2009. Feb, p. 117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Majeed A, Williams J, de Lusignan S, Chan T. Management of heart failure in primary care after implementation of the National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease: A cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2005 Feb;119(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.06.006.S0033-3506(04)00145-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Subramanian U, Fihn SD, Weinberger M, Plue L, Smith FE, Udris EM, McDonell MB, Eckert GJ, Temkit M, Zhou X, Chen L, Tierney WM. A controlled trial of including symptom data in computer-based care suggestions for managing patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2004 Mar 15;116(6):375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.021.S0002934303008040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roth A, Kajiloti I, Elkayam I, Sander J, Kehati M, Golovner M. Telecardiology for patients with chronic heart failure: The 'SHL' experience in Israel. Int J Cardiol. 2004 Oct;97(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.07.030.S0167527303005722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gnani S, Gray J, Khunti K, Majeed A. Managing heart failure in primary care: First steps in implementing the National Service Framework. J Public Health (Oxf) 2004 Mar;26(1):42–47. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grypdonck L, Aertgeerts B, Luyten F, Wollersheim H, Bellemans J, Peers K, Verschueren S, Vankrunkelsven P, Hermens R. Development of quality indicators for an integrated approach of knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014 Jun;41(6):1155–1162. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130680.jrheum.130680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jansen MJ, Hendriks EJ, Oostendorp RA, Dekker J, De Bie RA. Quality indicators indicate good adherence to the clinical practice guideline on "Osteoarthritis of the hip and knee" and few prognostic factors influence outcome indicators: A prospective cohort study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Sep;46(3):337–345. http://www.minervamedica.it/index2.t?show=R33Y2010N03A0337 .R33102240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.MacLean CH, Saag KG, Solomon DH, Morton SC, Sampsel S, Klippel JH. Measuring quality in arthritis care: Methods for developing the Arthritis Foundation's quality indicator set. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Apr 15;51(2):193–202. doi: 10.1002/art.20248. doi: 10.1002/art.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Peat G, Lawton H, Hay E, Greig J, Thomas E, KNE-SCI Study Group Development of the Knee Standardized Clinical Interview: A research tool for studying the primary care clinical epidemiology of knee problems in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002 Oct;41(10):1101–1108. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.10.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Glasziou P, Irwig L, Mant D. Monitoring in chronic disease: A rational approach. BMJ. 2005 Mar 19;330(7492):644–648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7492.644. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/15774996 .330/7492/644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van Steenkiste BC, Jacobs JE, Verheijen NM, Levelink JH, Bottema BJ. A Delphi technique as a method for selecting the content of an electronic patient record for asthma. Int J Med Inform. 2002 Apr;65(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(01)00223-4.S1386505601002234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gensichen J, Peitz M, Torge M, Mosig-Frey J, Wendt-Hermainski H, Rosemann T, Gerlach FM, Löwe B. The "Depression Monitoring list" (DeMoL) with integrated PHQ-D-Rationale and design of a tool for the case management for depression in primary care [Article in German] Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich. 2006;100(5):375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lougheed MD, Taite A, ten Hove J, Morra A, Van Dam A, Ducharme FM, Ferrone M, Gershon A, Goodridge D, Graham B, Gupta S, Licskai C, MacPherson A, Styling G, Tamari IE, To T. Pan-Canadian asthma and COPD standards for electronic health records: A Canadian Thoracic Society Expert Working Group Report. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2018 Nov 05;2(4):244–250. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2018.1517623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chmiel C, Birnbaum B, Gensichen J, Rosemann T, Frei A. The diabetes traffic light scheme: Development of an instrument for the case management in patients with diabetes mellitus in primary care [Article in German] Praxis (Bern 1994) 2011 Nov 30;100(24):1457–1473. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a000751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roland M. Linking physicians' pay to the quality of care: A major experiment in the United Kingdom. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 30;351(14):1448–1454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr041294.351/14/1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chmiel C, Senn O, Rosemann T, Del Prete V, Steurer-Stey C. CoCo trial: Color-coded blood pressure Control, a randomized controlled study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1383–1392. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S68213. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S68213.ppa-8-1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schectman G, Barnas G, Laud P, Cantwell L, Horton M, Zarling EJ. Prolonging the return visit interval in primary care. Am J Med. 2005 Apr;118(4):393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.003.S0002-9343(05)00004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC, International Working Group on Diabetic Foot Editorial Board Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012 Feb;28 Suppl 1:225–231. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Clarson LE, Nicholl BI, Bishop A, Edwards JJ, Daniel R, Mallen CD. Monitoring osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional survey in general practice. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;6:85–91. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S12606. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24324351 .cmamd-6-2013-085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Scalvini S, Martinelli G, Baratti D, Domenighini D, Benigno M, Paletta L, Zanelli E, Giordano A. Telecardiology: One-lead electrocardiogram monitoring and nurse triage in chronic heart failure. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11 Suppl 1:18–20. doi: 10.1258/1357633054461750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morilla-Herrera JC, Garcia-Mayor S, Martín-Santos FJ, Kaknani Uttumchandani S, Leon Campos Á, Caro Bautista J, Morales-Asencio JM. A systematic review of the effectiveness and roles of advanced practice nursing in older people. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016 Jan;53:290–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.010.S0020-7489(15)00311-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Agrinier N, Altieri C, Alla F, Jay N, Dobre D, Thilly N, Zannad F on behalf of ICALOR. The ICALOR home-nurse led disease management programme in heart failure prevents hospital readmission: A French nationwide time-series comparison. Proceedings of the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2012; European Society of Cardiology Congress 2012; August 25-29, 2012; Munich, Germany. 2012. pp. 159–160. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article-pdf/33/suppl_1/19/1188353/ehs281.pdf . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Elsevier), and the Cochrane Library (Wiley).

List of all included studies, including monitoring indicators for the five chronic conditions.

Asthma indicators mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Arterial hypertension indicators mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Chronic heart failure indicators most frequently mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Osteoarthritis indicators most frequently mentioned in guidelines and studies.

Guidelines screened for indicators for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Guidelines screened for indicators for asthma.

Guidelines screened for indicators for arterial hypertension.

Guidelines screened for indicators for chronic heart failure.

Guidelines screened for indicators for osteoarthritis.