Abstract

Objective:

To address the organization of conversations in oncology visits by taking an “interaction order” perspective and asking how these visits are intrinsically organized.

Methods:

Conversation analysis.

Results:

Using audio recordings of talk in oncology visits involving patients with non-small cell lung cancer, we identify and analyze an “appreciation sequence” that is designed to elicit patients’ understanding and positive assessment of treatments in terms of their prolongation of life.

Conclusion:

An “appreciation sequence,” regularly initiated after the delivery of scan results and/or treatment recommendations, simultaneously reminds patients of their mortality while suggesting that the treatment received has prolonged their lives, and in some cases significantly beyond the median time of survival.

Practice implications:

We explore the functions of the appreciation sequence for cancer care and set the stage for considering where and when physicians have choices about the order and direction the talk can take and how to allocate time for end of life and quality of life conversations.

1. Introduction

In the popular press [1,2] and in medical research [3], investigators suggest that, beyond managing symptoms and pain, cancer care should include maintaining quality of life, knowing patients’ attitudes toward aggressive treatment and resuscitation orders, and facilitating a sense of completion by allowing for timely life review, saying goodbye, and resolving unfinished business. However, as doctors, nurses, patients and caregivers work diligently to stave off death, conversations by which they address quality and end of life are at best infrequent and at worst nonexistent [4,5]. This matter has been documented again and again in various ways—through surveys and experiments [6,7], patient ratings of doctors [8] ethnographic studies [9,10:1380], content analysis, coding, or conversation analysis of audio recordings [11–14], and clinical experience and research [1]. These investigations, from Britain, Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the U.S., use concepts such as avoidance, allusiveness, routinizing, vagueness, and withholding to characterize physician behaviors and patient contributions—or lack thereof—regarding end of life and quality of life discussions. In other cultures as well, it appears that “most patients do not know the implications of their illness, and they do not know their prognosis” [15:148,cf. 16].

2. Theory and methods

In the face of cross-national consensus about what is not occurring in oncology clinics, it seems compelling to ask exactly what is going on. Our approach to these questions is to follow the notion of the “interaction order” as the sociologist Erving Goffman formulated it. The interaction order is a “substantive domain” whose elements or features “fit together more closely than with elements beyond the order” [17:2]. Elements from beyond the interaction order could derive from economic, political, demographic, ethnic, and other domains that social scientists often investigate for their effects on interaction without treating interaction on its own terms.

Our use of interaction order theory [18] is to highlight how studies that employ survey questions to evaluate cancer communication draw on extra-situational concepts and measures to characterize occurrences within a social situation that has its own parameters. Studies that utilize ethnographic observations or interviews also may gage interaction—often with a focus on physician behavior—using concepts such as “open communication” or what the researchers know is potentially communicable between doctor and patient. Hence, investigators regularly use rubrics that have their provenance outside of the interaction and deflect full attention from the issues that emerge from within, according to the displayed orientations of doctor, patient, and caregiver. Accordingly, our goal in this paper is not to document further how—or explain why—prognostic conversations are largely absent from the oncology clinic. More modestly, we aim only to say what does happen during interaction in the clinic and how a particular facet of that interaction is configured. In so doing, we first explore the overall organization of the routine post-diagnosis oncology interview, and then document a phenomenon—the occurrence of an “appreciation sequence,” which bears on a particular communicative challenge for physicians: achieving positivity when presenting news about a patient’s ongoing cancer that, whether the tidings are relatively bad or good, also can serve as a reminder of the ultimately fatal nature of the disease.

We draw on the field of conversation analysis (CA), which is a sociological approach to the study of talk and interaction among humans. Applied to encounters in medical settings, CA regards the arena as one of “naturally occurring” interaction, where it is possible to use audio or video recordings and transcripts thereof to capture real-time utterances and other behaviors of participants (see Appendix A for transcribing conventions) [19]. Doctors, patients, and (if co-present) family members together construct actions relevant to their small, collective endeavors, whether it is talking sociably, taking or giving a medical history, doing diagnosis, discussing treatment recommendations, or engaging in other such efforts [20]. Maynard and Heritage [21] discuss other features of CA as applied to medical settings, including the primary orientation to sequencing as a feature of interaction and a methodological tool for capturing structure, an orientation to detail as a site of order and organization, the grounding of analysis in participant orientations, and working with both single cases and collections of patterns for developing generalizations.

Our data are audio recordings from an earlier study [22] evaluating the effects of an internet-based support system for patients and caregivers. Patient-caregiver dyads were recruited and recorded at four cancer-center hospitals in the East, Midwest, and Southwest U.S. between September 2004 and May 2009. Although patients with a variety of cancer types participated in several different studies, we had access only to recordings involving only patients with locally advanced (stage IIIB) and metastatic (stage IV) non-small cell lung (NSCLC) cancer. Of 128 recorded visits, half (64) were transcribed for intensive study, involving 51 triads of patient, caregiver, and doctor (some patients had more than one visit). Given the practicalities of doing conversation analytic research including the effort require for detailed transcriptions [21], our selections of interviews excluded those that had no delivery of scan results, discussion of ongoing treatment, or physician involvement (only the nurse saw the patient). Of the 51 patients in our collection, 29 were female and 22 were male, with a mean age of 64 years. Forty patients were white and 6 were non-white; for 5 patients, we did not have ethnic information. Twelve of the caregivers were adult children of the patient, and 36 were a spouse or partner (with no information for three).

3. Results and discussion

Just as medical interviews in primary care have an organization of component activities [23–26], oncology care (consultations that follow the initial diagnosis) has a phase structure. Beside the opening and closing, in our data there are three central components that regularly follow this order: review of symptoms (including medication side effects), presentation of imaging test results (e.g., X-ray, computerized axial tomography or CAT scan), and treatment discussions or recommendations, a necessary and vital consideration as physicians monitor the progress of the disease using their symptom reviews and scan results.1 It is within this organization that the appreciation sequence appears, just after the presentation of scan results and before treatment recommendations.

3.1. Delivering scan results

In the oncology clinic, physicians deliver news that is post-diagnosis and involves the results from scans or X-rays rather than initial identification of illness [28–31 ]. Ideally, because physicians have disclosed that there is no cure and that the median time from diagnosis to death is about 12 months, subsequent news deliveries about symptoms and scans occur in a context of “open” death awareness, where patients and family members as well as clinicians know that the person is dying [32–34]. In fact, however, for many reasons patients may be in other kinds of “awareness contexts” about the imminence of death, from “closed” to “suspected” to “mutual pretense” [32:11]. When oncologists have the results of an imaging test to report, the news falls into one of three categories as the cancer may have improved, remained stable—the patient’s tumor is found neither to have grown nor subsided within a standardized range [35]—or worsened. Patients are more or less cognizant of these distinct possibilities, and these news deliveries about an ongoing cancer have the typical talk-based asymmetries associated with favorable and unfavorable diagnoses [29,36,37]. It is in the context of stable news that we first noticed what we have come to call the appreciation sequence. Accordingly, we begin by considering such news and how the appreciation sequence emerges and is organized. Subsequently, we show its presence in relation to both bad and good cancer news.2

3.2. Tumor stability; occasioning appreciation

The most frequent kind of news in our data is that which suggests the patient’s tumor had neither grown nor subsided. Physicians use different expressions of this stability, as in “It doesn’t look any different (5.19), “looked exactly the same as before (16.16), “things look stable” (12.31), or “Your lung scan looked pretty darn uh stable” (11.19). Physicians deliver such news mostly as they do with good tidings, enacting patterns of “exposing” the news. Much as physicians may present the news as good, however, patients often receive it in a very measured kind of way, as if it were bad news.

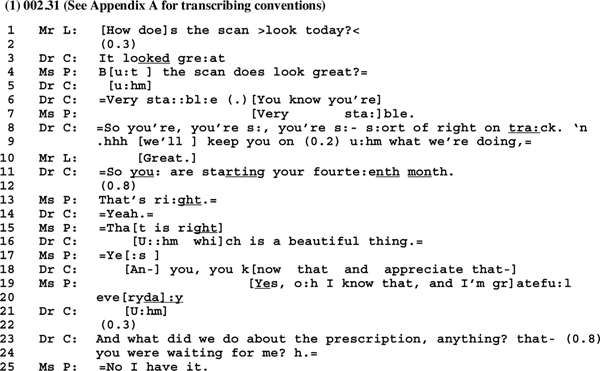

Extract 1 below is an example. Before the extract, there has been a symptom review, in which the patient, Ms. P, expressed a worry about the cancer spreading to her bones, and asked whether they should get a new scan. She also reported tiredness, nosebleeds, cold sores, eye irritation, and a cough. Suggesting a move from this kind of symptom talk to the next phase of the visit, it is the caregiver (“Mr. L”), who initiates the delivery of scan results (line 1). The news is prefaced with an assessment (line 3) suggestive of good news, after which Ms. P asks for confirmation (line 4). Dr. C confirms by pronouncing the reading as “very sta::ble” (line 6), which the patient receives with a downward-intoned repetition (line 7) of that pronouncement.

Dr. C, whose continuation (line 6) occurs in overlap with Ms. P’s utterance, retrieves the continuation with an upshot marker at line 8, suggesting the patient as being “right on track.” This utterance ends with final intonation, but the doctor appends a connective (“n” = “and”) and takes an inbreath, suggestive of effort to elicit a response from the patient. Instead, it is the caregiver who produces a delayed, downward intoned and thereby lax assessment (line 10). Dr. C’s continuation (line 9) consists of a proposal that the treatment regimen be extended. Latched to this proposal is a formulation about the length of time the patient has been dealing with the cancer (line 11). Representing something of a topic shift, this utterance is curious, and in the conversation analytic tradition [38:299], raises the “pervasively relevant” question, “why that now?”

Answering why-that-now involves observations about what has happened sequentially in the talk up until this point (i.e., line 11). For one matter, the symptom review not only has turned up a number of difficulties, some of which are side effects of the medication, but the patient also expressed a worry about the cancer spreading. More immediately and concretely, Ms. P’s display of recipiency regarding the assessment of the scan looking great (the request for confirmation, line 4) consists of a questioning stance; her receipt of the news of stability (line 7) simply repeats (with downward intonation) what Dr. C has said, rather than, for instance, assessing the news in a positive way that might match the prefacing “great” of the doctor.3

When Dr. C proposes her patient to be “on track” (line 8) there is no audible uptake from Ms. P and the caregiver interjects a delayed acknowledgement (line 10). Accordingly, “starting your fourteenth month” (line 11) addresses the displays of reticence on the part of the patient. It can act as a reminder that Ms. P has already outlived expectations and, given how long her cancer has been stabilized, provides an optimistic version of that stability. For this reason, we call the utterance a laudable event proposal. It offers a praiseworthy, “appreciable” version of the scan results just reported, suggesting that they be seen in the context of the post-diagnosis trajectory of the illness. Notice also that after the patient’s agreements (lines 13 and 15), Dr. C adds to the proposal, suggesting it as a “beautiful thing” (line 16), a term related to “extreme case formulations” [40], but here specifically maximizing a “state of affairs. .. when there are grounds … for expecting an unsympathetic hearing [41:34].” The preceding agreements and subsequent one (“Yes, ” line 17) act as “go-ahead” moves for production of the appreciation sequence: Dr. C, by way of overtly proposing the patient’s appreciation (line 18), solicits an expression of just that. However, Ms. P intersects that solicitationwith an agreeing turn of talk, a claim to know the “beautiful thing,” and a strong statement of gratefulness (lines 19–20). This achievement allows for Dr. C’s subsequent transition to treatment related talk (lines 21–24).

3.3. The appreciation sequence in cancer care

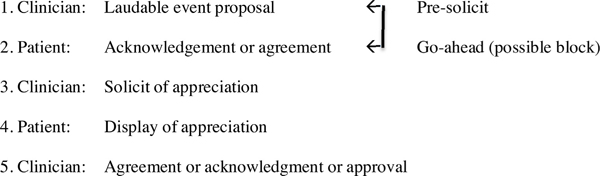

In our data, trajectories toward appreciation sequences appear with regularity. They are present in 19 of our 54 cases and deal with the downgraded ways in which patients often receive news about their CAT scans and other measures of tumor processes. The architecture of the sequence looks like this, with the first two components acting as a pre-sequence to the base appreciation sequence in components 3–5 as such [cf. 42]:

Patients can resist aligning to laudable event proposals such that progress to the appreciation sequence is forestalled and sometimes halted altogether. At step 2 above, silences, hesitation markers, and the prosody of an acknowledgment (involving low volume and downward intonation), can resist the forward movement of the sequence and, at times, even block its production. Out of 19 instances of identifiable laudability pre-sequences, eight eventuate in the appreciation sequence. (The selections of laudability pre-sequences and appreciation sequences in this paper are representative of other instances in our collection.) Blocking of the appreciation sequence as such happens in an example of bad news.

3.4. Tumor bad news

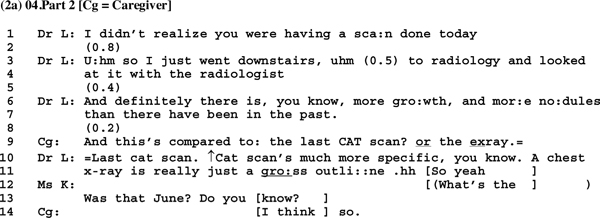

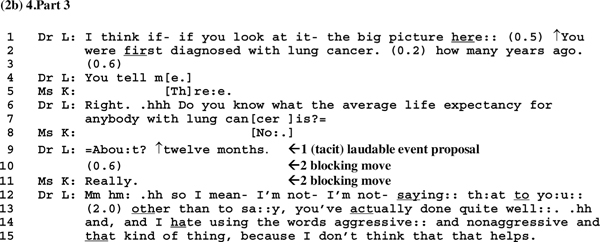

In the following case, involving a 69 year old female patient with stage IIIB NSCLC, the interview began, after exchanges of “how are you” [43], with a review of medications; the patient had seen another doctor who had recommended that she move from one anti-tumor therapy to another, and the present doctor endorsed this proposal. Subsequently, the patient (Ms. K) and Dr. L reviewed a persistent cough the patient was experiencing. The patient was concerned about treatment plans, re-raising the issue of whether to switch to the different medication, whereupon Dr. L suggested that it was a “personal decision.” At this point, Ms. K asked, “What about the CAT scan that was taken today?” Dr. L did not know that a scan had been done, and asked to go to the workroom to read the scan. When she returned, she started the conversation with an apology and said something mostly inaudible about the scans (not on transcript), and went on with an account or excuse (line 1). Following a silence, she narrates her trip “to radiology” (line 3), tells about looking at the scan collaboratively (lines 3–4), pauses (line 5), continues (lines 6–7) with an emphasis term (“And definitely”), hesitates (“you know”), and reports the “more growth, and “more nodules” result (phrases that are stretched in a turn with downward pitch).

In other words, Dr. L provides evidence for the news in narrative fashion, hesitantly pushing it to the end of her turn, which is a type of “shrouding” [29] that represents a facet of a bad news delivery. Moreover, after a brief silence (line 8), it is the caregiver who first responds to the news (line 9) by asking a comparative question. Following clarification of the type of scan being reported (lines 10–11), the patient furthers the comparative question in terms of when the previous scan was done (lines 12–13). After the caregiver answers (line 14), Dr. L estimates the time and then begins looking at her papers (there is audible shuffling of documents). This timing and comparison talk goes on for some time, followed by discussion of treatment for the cough as well as for the cancer.

At this point, Dr. L initiates talk about “the big picture” (lines 1–2 below), and produces an adumbrated laudable event proposal, asking the patient about the duration of her post-diagnosis disease. The patient resists answering (silence, line 3), suggesting that she may be working to forestall the time since diagnosis as a laudable event and to block movement toward appreciation. Nevertheless, Dr. L pursues a response (line 4), and the patient answers (line 5) in a way that confirms a state of knowledge whose display was initially withheld.

Dr. Lthen agrees and asks a question (lines 6–7) that can project a favorable contrast between how long the patient has stayed alive and the “average life expectancy,” but which generates further resistance by way of the patient’s terse claim not to know that expectancy (line 8), such that the doctor produces the number (line 9). This utterance works to establish a tacit laudable event proposal. Following this is not only a silence (line 10) but a classic example of what Jefferson [44] calls a “news receipt” (line 11) that curtails [45:339–344] or discourages [29:102–103] further talk on the matter. For the appreciation sequence, the silence and news receipt block proceeding to a part 3 solicit of appreciation, as Dr. L produces a minimal token (line 12) and then a defensive discussion of her having broached the topic and a return to a topic that the participants addressed earlier in the context of discussing treatment.

3.5. Overcoming resistance to appreciation

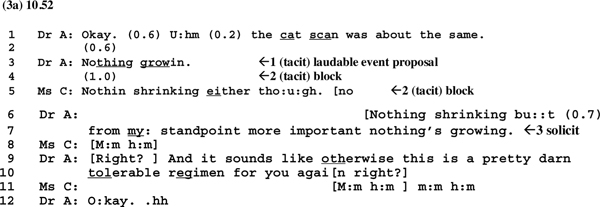

In the case fromwhich extracts 2a and 2b are taken, there is no progression to an appreciation sequence, which raises a question of whether the doctor’s line of talk (lines 1–2,4, 6–7) in fact could be projecting an appreciation sequence.4 That is, because no appreciation sequence is produced in extracts 2a or 2b, what is the evidence that the sequence is projectable, and that the patient opposes its production? How the patient’s silence (line 3) and disclaimer of knowledge (lines 6–7) constitute a blocking move can be seen in different example. In this one also, the physician tacitly produces a laudable event proposal and the patient shows resistance. Instead of leaving the matter to lie, the physician works to obtain a go-ahead rather than blocking move, such that eventually an appreciation sequence is induced. The news here is of stability (line 1below), which meets with silence(line2). In line3, Dr. Adeals with the silence by way of a tacit laudable event proposal(line3). She uses a litotes—a rhetorical device for alluding to an upshot and inviting the recipient to provide that upshot [47:150]. Here, Dr. A’s “Nothing growin” formulation can invite a positive assessment from the patient, upon which an appreciation sequence could be built, but the patient withholds acknowledgment (line 4), and then reverses Dr. A’s optimistic “nothing growin” formulation (line 3) to its converse pessimistic version in an utterance spoken with downward intonation (line 5). Both of these moves (lines 4 and 5) effectively block progression toward appreciation.

At this point, Dr. A agrees (line 6) and, following a contrast term (“but,” line 6) she asserts her epistemic status as a doctor (“from my standpoint,” line 7) before reproducing the news in a declarative way that represents an assertion of “standpoint” or epistemic stance [48], suggesting that a stable tumor is “more important” than a reducing one (implying that, at least, the tumor is not growing). This is an appreciation solicit, which Ms. C treats with an acknowledgement (line 8) in overlap with Dr. A’s delayed tag question (line 9) to which Dr. A also latches a treatment recommendation (lines 9–10). So here, the appreciation solicit, meeting only with an acknowledgement, occasions another kind of action rather than an attempt to obtain a display of gratitude for the achievement of stability.

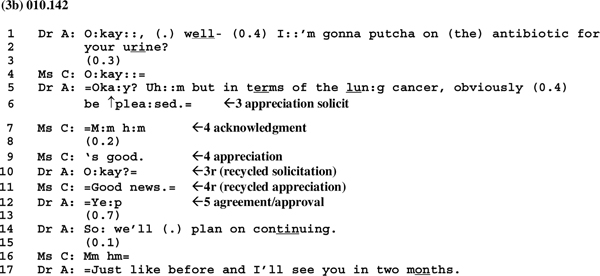

However, that is not the end of the matter. Dr. A briefly examines Ms. C’s abdomen and asks about how her at-home chemotherapy injections were going (not excerpted here). She then recommends an antibiotic for her urine infection (lines 1–2 below). Subsequent to Ms. C’s indication of acceptance (line 4), the doctor issues a closing “okay” (line 5), and then, having earlier (in 3a) engaged in the production of parts 1 and 2 of an appreciation sequence, as well as a tacit part 3, she moves to an overt part 3 (arrow 3, lines 5–6), re-soliciting a display of appreciation. The use of “obviously” in line 5 is a “tying” term that links to the previous utterance of the doctor (extract 3a, line 7) displaying her authoritative standpoint on the scan results:

Ms. C accepts the appreciation solicit by producing an acknowledgement (line 7) and positive assessment (line 9), after which is an upgraded recycling of the solicitation and acceptance (lines 10–11, arrows 3r and 4r) and a part 5 agreement or approval on Dr. A’s part (line 12). Ms. C’s initial displays of resistance have been overcome. Then the interview is brought to a close (lines 14–17).

3.6. The regular use of appreciation sequences: tumor good news

Appreciation sequences, we have shown, may accompany the delivery of scan results that are about stability (extracts 1, 3a and b) or that embody bad news because of evident tumor growth and/or more nodules, although the full sequence is sometimes blocked when pre-sequence resistance is strong (extracts 2a and b). In addition, the appreciation sequence also can work with good news about a scan. In fact, oncologists may attempt to exit all three types of encounters with a good news structure by way of the appreciation sequence.

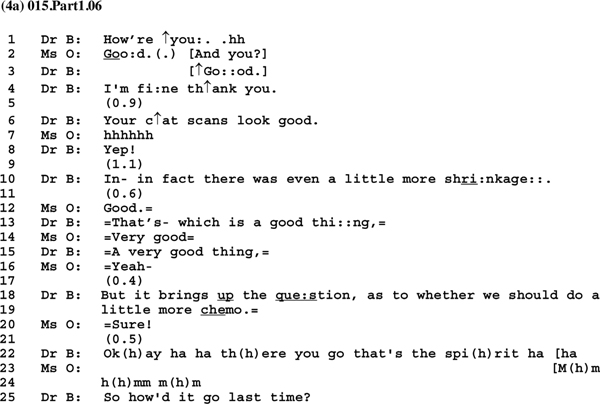

With chemotherapy treatment, although a lung tumor cannot be eliminated, it can be reduced. When that happens, the scan news is both delivered and received according to patterns associated with good news—rather than being shrouded, it is exposed in various ways. Extract 4a is an instance. One aspect of its exposure is that the physician, Dr. B, instead of commencing the interview with a review of symptoms or physical exam, in a sense breaches the usual phase structure and delivers the news immediately upon entering the examination room after exchanging how-are-you sequences with the patient, Ms. O (lines 1–4). Following a silence (line 5), but otherwise without hesitation, Dr. B delivers the news with an initial positive assessment, after which the patient’s audible outbreath (line 7) constitutes a kind of sighing expression.5 Dr. B then affirms the news (line 8) and, pausing (line 9; she may be looking at or showing the scan), suggests “a little more shrinkage” (line 10). From the inception of the visit, the doctor sounds upbeat in producing each of her early turns with rising pitch on some components (lines 1, 3, and 6), and, after the patient’s sighing outbreath (line 7) exclaiming her affirmation (line 8) and adding a description about “shrinkage” (line 10), to which Ms. O replies with a positive assessment (line 12).

Dr. B affirms the assessment (line 13), after which Ms. O upgrades her assessment (line 14) and Dr. B agrees (line 15). Then, after the further agreement token from Ms. O, there is immediate transition to the issue of treatment and “whether” they should do “more chemo” (lines 18–19). Although markedly cautious by way of posing a question rather than asserting, Dr. B’s utterance has positive polarity. That is, with its “we should do … ” modal formatting, it tacitly proposes continuation of the current treatment. The patient’s alignment to this proposal is instantaneous (per the latch marks or equal signs at lines 19–20) and strongly affirmative (“Sure!”). Possibly due to the misfit between the cautious proposal of “more chemo” and the patient’s immediate and forceful agreement, the doctor shows surprise—there’s a brief pause (line 21) and then both a laughing “surprise token” [51] and a laughter-infused commendation of the patient that may account for the surprise (line 22, the patient has shown good “spirit”).

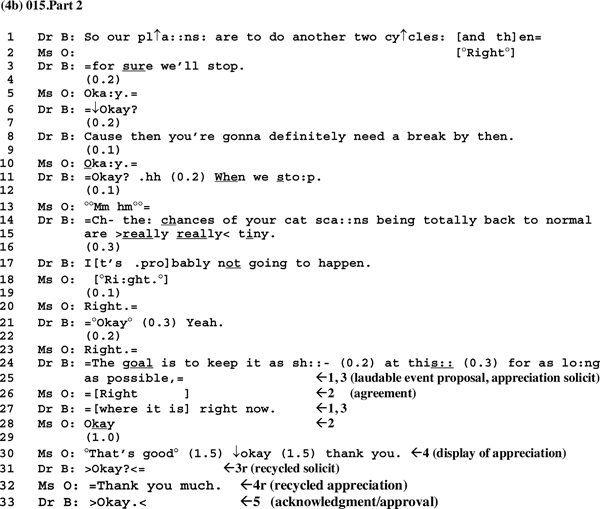

Subsequently, and again somewhat out of phase order because of the preemptive exposing of the good scan news, there is a review of the patient’s symptoms, which are mostly mild, and the physician, Dr. B, listens to her heart. They establish a plan for more of this chemotherapy and then stopping treatment for a period. Coming to the end of the interview, Dr. B summarizes the visit (lines 1–3 below) and suggests the need for “a break” (line 8):

The patient’s receipts of the plan formulation and reason are quiet (line 2), delayed (lines 4, 9) and/or spoken with downward intonation on “okay” type tokens (lines 5, 10), suggesting at least slight resistance. Then, the doctor produces a prognostic proposal with negative valence (lines 11, 14–15, 17). This seems to be a rare case where good news, as delivered at the beginning of the interview, is counterbalanced with a kind of bad news forecast. To put the matter colloquially, it is as if the physician does a dance to balance the good news and the patient’s enthusiastic receipt and endorsement of continued treatment with a reminder about ultimate prognosis [52,53].

The matter is not yet laid to rest. After the patient’s receipts (lines 18, 20, 23) of the bad news forecast, the doctor proceeds to suggest “the goal” of the patient’s treatment regimen—namely, keeping the tumor stable. In so doing, and partly through a kind of extreme or at least maximum case formulation [40]—”as long as possible,” lines 24–25)—Dr. B can be working to initiate an appreciation sequence (lines 24–25,27) related to the goal, in a way that embodies both a pre-sequence laudable event proposal (part 1) and a tacit appreciation solicit (part 3). Ms. O aligns to the initiation (lines 24–25) with an agreement (line 26) and to an addition (line 27) with an acknowledgement (line 28).6 The silence (line 29) indicates lack of turn transition and can be a point where Dr. B awaits her patient’s apprehension, as in a display of understanding, of the tacit solicitation. Ms. O evidently treats the silence that way (as awaiting her response) with a positive assessment (line 30) and, across two further silences (also at line 30), with an eventual gratuity token, “thank you.” Turns 3 and 4 of the appreciation sequence are recycled at lines 31 and 32 before Dr. B closes off the sequence (line 33) and provides for exiting the interview (subsequent discussion is about whether the patient should go to the on-site laboratory or to the chemotherapy unit).

4. Conclusion and practice implications

4.1. Conclusion

This paper began with the assertion that we need to take an interaction order approach to understanding communications in the cancer clinic. The strategy is to come to grips with what does happen as the organization of talk and social interaction in the situation. Instead of further documenting evasion, allusive talk, distancing, avoidance, withholding of end of life talk, we have analyzed an “appreciation sequence,” regularly initiated after the delivery of scan results and/or treatment recommendations, which simultaneously reminds patients of their mortality while suggesting that the treatment received has prolonged their lives, and in some cases significantly beyond the median time of survival. The simple message is that it is appreciably good that treatments of the patient have prolonged his or her life, even if the tumor is now growing or spreading.

When participants and observers of the oncology clinic are wanting something different, something changed, or something better suited to ex situ or extra-situational notions of best practices in regard to end of life and quality of life discussions, our analysis suggests an avenue within the local interaction order. As part of this order, appreciation sequences deal with the full reality of the patient’s cancer, and are therefore a foundation upon which participants can elect to mount other conversations. Despite the patient’s terminal prognosis, these sequences induce “out loud” or public displays of gratitude for the efficacy of their cancer care so far. From a physician’s point of view, these exhibits of appreciation may facilitate patient commitment to further treatment. For patients, although such sequences may be difficult (as shown in their patterns of resistance), they may be necessary reminders about the nature and trajectory of their illness. Then, having together acknowledged what the patient’s disease is and how they are dealing with it, and whereas the usual progression of the interview is toward the phase of further treatment discussions, something else is possible. Given that it is the physician who initiates an appreciation sequence, at the completion of the sequence is an opportunity for the physician to temporarily forego treatment discussions and instead to direct the conversation toward prognostic awareness. If the physician does not do so, patients thereby have a juncture at which to raise such issues themselves.

11.2. Practice implications

In his discussion of diagnosis in the primary care encounter, Heath [28:264] remarks, “It is… important that any initiative to transform behavioral features of the consultation is sensitive to the interactional organizations in and through which the diagnosis of disease and its management are accomplished.” As we continue our research, we are exploring how clinicians can identify interactional organization and spot those moments within this organization where and when they have choices about the direction the talk can take. The immediacy with which there may be movement from symptom talk to reporting scan results to appreciation sequences to treatment recommendations, although orderly in its own right, is not a fixed phenomenon. Rather it is susceptible to interventions regarding the order and relative amount of time devoted to these phases to allow for end of life and quality of life discussions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of funding

National Cancer Institute grant #P50CA095817

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for very helpful comments on previous versions of the paper. We are also grateful to James F. Cleary, Lori Dubenske, and David Gustafson for sharing audio recordings from the parent study.

Footnotes

Sandén et al. [27] discuss a three-phase core to the interview that differs slightly from ours. Their subjects were patients with testicular cancer, and they refer to updating, discussion of news regarding test results and X-rays, and planning. What we are calling treatment recommendations could be considered as planning, although Sandén et al. [27] refer mainly to scheduling next visits and the like. When their and our three phases are put together with openings and closings, it would appear that oncology visits have similar structures across types of cancer.

Fifty-four of our cases have deliveries of scan news; approximately 15% were good news, 24% were bad news, and 56% involved stable news. The remaining 5% involved a mixture of two types of news, usually bad and stable.

Assessments are a regular final turn in a news delivery sequence, and often match the valence that the speaker accords to the news [29,39].

For another example of a failed attempt at an appreciation sequence, see example 5 in Costello and Roberts [46:250].

See the discussion in Beach et al. [49:898 ] regarding how non-vocal aspects of a patient’s recipiency can display an orientation to her “extended and complicated medical history,” including what Peräkylä [50] has called a “dreaded future.”

See Levinson [54:356–364] on ways in which a pre-sequence can embody the sequence to which it is otherwise a “pre”—i.e., a position 1 item may be built to occasion a position 4 turn of talk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016Zj.pec.2015.07.015.

References

- [1].Gawande A Letting Go New Yorker. 2010; August 2:36–49. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gawande A, Being Mortal Medicine and What Matters in the End, Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt, New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. , Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 19 (2000) 2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schaepe K, Maynard DW, After the diagnosis: news disclosures in long-term cancer care, in: Hamilton HE, Chou W-yS. (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and health Communication, Routledge, New York, 2014, pp. 443–458. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schaepe KS, Affective Communication: Management of Bad News Following Cancer Diagnosis and Stem Cell Transplant, University of Wisconsin, Madison WI, 2012. (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation). [Google Scholar]

- [6].Christakis NA, The ellipsis of prognosis in modern medical thought, Soc. Sci. Med. 44 (1997) 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ, Attitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists, Arch. Intern. Med. 158 (1998) 2389–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, et al. , Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD, Euro. Respir. J. 24 (2004) 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Taylor KM, Telling bad news: physicians and the disclosure of undesirable information, Soc. Health Illn. 10 (1988) 109–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].The AM, Hak T, Koeter G, et al. , Collusion in doctor-patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study, Br. Med. J. 321 (2000) 1376–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fagerlind H, Lindblad AK, Bergstrom I, et al. , Patient-physician communication during oncology consultations, Psychooncology 17 (2008) 975–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Audrey S, Abel J, Blazeby JM, et al. , What oncologists tell patients about survival benefits of palliative chemotherapy and implications for informed consent: qualitative study, Br. Med. J. (2008) 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. , Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171 (2005) 844–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lutfey K, Maynard DW, Bad news in oncology: how physician and patient talk about death and dying without using those words, Soc. Psychol. Q. 61 (1998) 321–341. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Tsilika E, et al. , Information disclosure in different cultural contexts, Support Care Cancer 12 (2004) 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Surbone A, Persisting differences in truth telling throughout the World, Support Care Cancer 12 (2004) 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Goffman E, The interaction order, Am. Soc. Rev. 48 (1983) 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rawls AW, The interaction order sui generis: Goffman’s contribution to social theory, Soc. Theory 5 (1987) 136–149. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Clayman SE, Gill VT, Conversation analysis, in: Gee JP, Handford M (Eds.), The Routledge; Handbook of Discourse Analysis, New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Heritage J, Maynard DW, Communication in Medical Care: Interactions between Primary Care Physicians and Patients, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Maynard DW, Heritage J, Conversation analysis, doctor-patient interaction and medical communication, Med. Educ. 39 (2005) 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gustafson DH, DuBenske LL, Namkoong K, et al. , An eHealth system supporting palliative care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer, Cancer 119 (2013) 1744–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Byrne PS, Long BEL 1976, Doctors Talking to Patients: A Study of the Verbal Behaviours of Doctors in the Consultation, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Frankel RM, Talking in interviews: a dispreference for patient-initiated questions in physician-patient encounters, in: Psathas G (Ed.), Interaction Competence, University Press of America, Lanham, mD, 1990, pp. 231–262. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Heritage J, Maynard DW, Problems and prospects in the study of physician-patient interaction: 30 years of research, Annu. Rev. Soc. 32 (2006) 351–374. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Robinson JD, An interactional structure of medical activities during acute visits and its implications for patients’ participation, Health Commun. 15 (2003) 27–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sandén I, Linell P, Starkhammar H, et al. , Routinization and sensitivity: interaction in oncological follow-up consultations, Health 5 (2001) 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Heath C, Diagnosis and assessment in the medical consultation, in: Drew P, Heritage J (Eds.), Talk at Work, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, pp. 235–267. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Maynard DW, Bad News, Good News: Conversational Order in Everyday Talk and Clinical Settings, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 20032003. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Maynard DW, Does it mean I’m gonna die?: on meaning assessment in the delivery of diagnostic news, Soc. Sci. Med. 62 (2006) 1902–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Peräkylä A, Authority and accountability: the delivery of diagnosis in primary health care, Soc. Psychol. Q. 61 (1998) 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Glaser BG, Strauss AL, Awareness contexts and social interaction, Am. Soc. Rev. 29 (1965) 699–779. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Seale C, Communication and awareness about death: a study of a random sample of dying people, Soc. Sci. Med. 8 (1991) 943–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Seale C, Awareness of dying: prevalence, causes and consequences, Soc. Sci. Med. 45 (1997) 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Eisenhauer EA, Therrase P, Bogaerts J, et al. , New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guidline (version 1.1), Eur. J. Cancer 45 (2009) 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Freese J, Maynard DW, Prosodic features of bad news and good news in conversation, Lang. Soc. 27 (1998) 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Maynard DW, Freese J, Good news, bad news, and affect: practical and temporal ‘emotion work’ in everyday life, in: Peräkylä A, Sorjonen M-L (Eds.), Emotion in Interaction, Oxford, New York, 2012, pp. 92–112. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schegloff EA, Sacks H, Opening up closings, Semiotica 8 (1973) 289–327. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Maynard DW, Good news, bad news, and affect: practical and temporal ‘emotion work’ in everyday life, in: Peräkylä A, Sorjonen M-L (Eds.), Emotion in Interaction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, 2012, pp. 92–112. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pomerantz A, Extreme case formulations: a way of legitimizing claims, Hum. Stud. 9 (1986) 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Edwards D, Managing subjectivity in talk, in: Hepburn A, Wiggins S (Eds.), Discursive Research in Practice: New Approaches to Psychology and Interaction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 2007, pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schegloff EA, Sequence Organization, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Frankel RM, Some answers about questions in clinical interviews, in: Morris GH, Chenail RJ (Eds.), The Talk of the Clinic: Explorations in the Analysis of Medical and Therapeutic Discourse, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1995, pp. 223–257. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jefferson G. The Abominable ‘Ne?’: A Working Paper Exploring the Phenomenon of Post-Response Pursuit of Response. Manchester, England, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Heritage J, A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement, in: Atkinson JM, Heritage J (Eds.), Structures of Social Action, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1984, pp. 299–345. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Costello BA, Roberts F, Medical recommendations as joint social practice, Health Commun. 13 (2001) 241–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bergmann JR, Veiled morality notes on discretion in psychiatry, in: Drew P, Heritage J (Eds.), Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Heritage J, Epistemics in conversation, in: Sidnell J, Stivers T (Eds.), Handbook of Conversation Analysis, Blackwell, New York, 2013, pp. 370–394. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Beach WA, Easter DW, Good JS, et al. , Disclosing and responding to cancer ‘fears’ during oncology interviews, Soc. Sc. Med. 60 (2005) 893–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Peräkylä A, Invoking a hostile world: discussing the patient’s future in aids counselling, Text 13 (1993) 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wilkinson S, Kitzinger C, Surprise as an interactional achievement: reaction tokens in conversation, Soc. Psychol. Q. 69 (2006) 150–182. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Beach WA, Managing optimism, in: Glenn P, LeBaron CD, Mandelbaum J (Eds.), Studies in Language and Social Interaction: In Honor of Robert Hopper, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, 2003, pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Beach WA, Managing Hopeful Moments: initiating and responding to delicate concerns about illness and health, in: Hamilton HE, Chou W.yS (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Health Communication, Routledge, New York, 2014, pp. 459–476. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Levinson SC, Pragmatics Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.