Abstract

Bacterial exotoxins are major causative agents that infect by promoting cell and tissue damages through disabling the invading host immune system. However, the mode of action by which toxins modulate host immune system and lead cell death is still not completely understood. The nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans has been used as an attractive model host for toxicological studies. In this regard, the present study was undertaken to assess the impact of Staphylococcus aureus toxin (PemK) on the host C. elegans through global proteomics approach. Our proteomic data obtained through LC-MS/MS, subsequent bioinformatics and biochemical analyses revealed that in response to PemKSa a total of 601 proteins of C. elegans were differentially regulated in response to PemKSa. The identified proteins were found to mainly participate in ATP generation, protein synthesis, lipid synthesis, cytoskeleton, heat shock proteins, innate immune defense, stress response, neuron degeneration, and muscle assembly. Current findings suggested that involvement of several regulatory proteins that appear to play a role in various molecular functions in combating PemKSa toxin-mediated microbial pathogenicity and/or host C. elegans immunity modulation. The results provided a preliminary view of the physiological and molecular response of a host toward a toxin and provided insight into highly complex host-toxin interactions.

Keywords: Cloning, PemKSa toxin protein, C. elegans, proteomics analysis, oxidative stress pathways, Western blotting, immune pathways, bioinformatic analysis

Introduction

Caenorhabditis elegans has a number of features that make it quite powerful model for biological studies and relevant to higher eukaryotes in areas such as genetics, cell death, neuroscience, aging, and development (Brenner, 1974; Horvitz, 2003; Sulston, 2003; Kenyon, 2005). The use of whole-organism for assays allows us to study the entire functional multicellular unit instead of a single cell (Kaletta and Hengartner, 2006). C. elegans has served as a successful model for assessing various neurotoxic chemicals (Boyd et al., 2003; Anderson et al., 2004; Melstrom and Williams, 2007; Rajini et al., 2008). Toxicological studies of C. elegans are likely relevant to higher eukaryotes. In addition, the ability to perform both forward and reverse genetic screens in C. elegans make it highly useful to understand host-toxin interactions at molecular levels (Brenner, 1974; Jorgensen and Mango, 2002).

In its natural environment, C. elegans interacts with a diverse range of microorganisms, including bacteria that can serve as food source. Certain soil bacteria have evolved their systems to fight against nematode predation. Some pathogenic bacteria are capable of proliferating in and killing the nematode by an infectious process or through the toxin secretions (Tan, 2002; Burlinson et al., 2013; Nandi et al., 2015). Bacterial pore-forming toxins are proteinaceous, that play a key role in pathogenesis (Huffman et al., 2004a; Aroian and Van Der Goot, 2007; Gonzalez et al., 2008) and constitute the single largest class of bacterial virulence factors, comprising 25–30% of all bacterial toxins (Alouf, 2003; Matarrese et al., 2007). Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) coexists with C. elegans in its natural habitat. An important characteristic of Bt strains is to produce insecticidal crystal proteins (Cry) during sporulation stage. These proteins are highly specific and target insects and nematodes, and act as a viable alternative for agriculture pesticide (Pardo-Lopez et al., 2012). Several families of crystal proteins were observed to be toxic to C. elegans, such as Cry5, Cry6, Cry12, Cry14, Cry21, and Cry55 (Zhang et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2014).

Most of the bacterial toxins are targeting the mitochondria, which is a common strategy of pathogenesis in order to accomplish apoptosis (Matarrese et al., 2007). The mode of action of pore- forming toxins are to make holes in the cell plasma membrane, disrupting the membrane potential, ion balance, and breaching the cellular reliability which results in cell death or other faults, remarkably aiding in bacterial pathogenesis (Bravo et al., 2007). C. elegans appears to be utilizing various defense responses against pathogens and harmful toxins through its innate immune system (Hasshoff et al., 2007) and behavioral defenses (Schulenburg and Müller, 2004). Previous studies have confirmed that C. elegans acquire a range of innate immune responses to protect itself when intoxicated by Bt toxic proteins such as activating p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and c-Jun N-terminal-like kinase (JNK) pathway (Huffman et al., 2004b), triggering an unfolded protein response (Bischof et al., 2008), stress, and a hypoxic response (Bellier et al., 2009). C. elegans might use all innate immune responses in natural habitat, to protect from a diverse range of pathogens and their toxins. The Pem is a toxin-antitoxin loci of the R1/R100 plasmid (Bravo et al., 1987), and the term PemKSa, is derived as follows: Pem indicates the loci, K represents killer protein and Sa represents S. aureus bacteria. The toxin (PemKSa) is a sequence-specific endoribonuclease that recognizes the tetrad sequence UAUU. Data suggests PemK intoxication changes the translation of large pool of host genes; degrades the cellular RNA, limit the cell growth. The prolonged activation of PemKSa leads to cell death (Bukowski et al., 2013).

The endeavor of the current study is to identify the involvement of host proteins and their contribution during PemKSa toxin exposure. To gain insight, a proteomic analysis using nano-LC-MS/MS was performed to monitor the changes in protein regulation. The biological significance of this study is to identify system-wide effects of PemKSa intoxication on C. elegans at the protein level, growing the list of immune effectors potentially acting toward the bacterial toxins. This finding may help to understand the mechanism of bacterial pathogenesis during host-pathogen toxin interaction in other organisms.

Materials and Methods

Nematode C. elegans and Bacterial Strain Maintenance

Nematodes used in the present study were wild type N2 Bristol, and out-crossed mutant ogt-1 (RB653) which were obtained from the CGC (Caenorhabditis Genetic Center, MN, USA). The animals were cultured as described earlier Stiernagle (2006). The plates were seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 strain, which was used as the food source for C. elegans. Eggs were isolated from mixed stage cultures of C. elegans grown on NGM plates using a simple bleaching protocol (5M KOH and bleach as 1:1 ratio) to grow synchronized L4 stage worms for the experiments.

Preparation of E. coli BL21 DE3 Competent Cell

The synthetic pETDuet1-PemKSa vector was kindly provided by Dr. Benedykt Wladyka Malopolska, Center of Biotechnology, Gronostajowa Krakow, Poland. Transformation was performed as described by Sambrook and Russell (2006). Briefly, an overnight grown high-efficiency protein expression E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells were seeded into 20 mL of LB broth and incubated at 37°C with shaking speed (220–250 rpm) till the OD600nm reaches 0.4–0.6. The culture was kept in ice for 30 min. After incubation, the cell pellet was collected using centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was decanted and the pellet was suspended in 25 mL of ice cold 100 mM CaCl2 and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was dissolved in 500 μL of ice cold 100 mM CaCl2. Aliquots of 100 μL of BL21 (DE3) cell were dispersed into pre-chilled microfuge tubes, used for transformation.

Protein Purification

Briefly, a single DE3 transformed colony was selected and inoculated overnight in 5 mL of LB media supplemented with ampicillin (100 mg/L), incubated at 37°C overnight for the expression analysis. later, 1 mL of mother culture was sub-cultured into 20 mL of LB media supplemented with ampicillin (100 mg/L) and incubated at 37°C till the growth reached mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.6). After reaching the required OD, the culture was induced by (0.1 mM) IPTG and incubated at 37°C with continuous shaking (200 rpm) for 4 h. After incubation, the cell pellets were collected using centrifugation and stored at −80°C for further analysis. Cells were lysed with an ultrasonication (Sonics & Materials, Danbury, CT, USA) in 1X PBS (NaCl 8 g, KCl 0.2 g, Na2HPO4 1.44 g, and KH2PO4 0.44 g, pH 7.5) with 5 μg/mL of DNase I, along with protease inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. Soluble recombinant proteins were affinity purified by using Ni-NTA His Bind Resin (Novagen 70666) as per the instructions. The PemKSa protein fractions was collected and stored at −80°C until use and purity of proteins was analyzed by gradient SDS-PAGE. The collected protein fractions were dialyzed by benzoylated dialysis tubing (Sigma Aldrich) as per manufacturer's protocol against 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mM NaCl buffer to remove the imidazole.

Toxicity Assay

Caenorhabditis elegans intoxication assay was performed to determine the impact of toxin on nematode. Approximately, 20 L4 stage age-synchronized C. elegans were transferred from a lawn of E. coli OP50 to a 24-well plate containing E. coli DE3 (control), and transformed E. coli DE3 cells with and without IPTG induction (treated). Other experimental sets contain E. coli OP50 (control) or purified PemKSa toxin protein plus E. coli OP50 (treated), respectively. The plates were incubated at 20°C. C. elegans life span changes were monitored during the assays. The plates were scored for C. elegans viability after every 6 h. The worms that failed to respond to gentle touch using a worm picker were considered dead. All the experiments were carried out independently in biological triplicates. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to compare the mean lifespan of control and treated nematodes and the error bars represent the mean ± SD (*p < 0.05).

Morphological Assay

The age synchronized L4 stage C. elegans were exposed to 24 h with various concentrations (100 and 200 μg) of purified PemKSa. After incubation worms were washed thoroughly with M9 buffer to take away the surface bound proteins. Morphological changes of C. elegans were examined using Light Microscope (Nikon).

Protein Extraction and Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

Based on the killing assay, final concentration of PemKSa toxin protein was maintained at 0.400 μg/mL and exposure time 24 h was chosen for subsequent translational studies. After toxin protein exposure, the C. elegans were washed thoroughly with M9 buffer to take away the surface bound toxin proteins. The washed animals were dissolved into 30 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5 along with protease inhibitor cocktail). Subsequently, the solid homogenate was sonicated on ice for 3 min at 10 s pulse interval, debris was removed by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 5 min and the resulting supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was determined by using Bradford reagent (Sigma Aldrich) (Bradford, 1976) and the protein concentration was maintained at 100 μg per sample. The collected samples were purified using 2D cleanup kit (GE Healthcare) per manufacturer's instructions. The protein profiling and quantification analysis has been done at out-sourcing center in Rajiv Gandhi Center for Biotechnology Kerala, India. Equal amounts of proteins from the control and treated C. elegans groups were subjected to in-solution trypsin digestion to make peptides. Prior to digestion the proteins samples were reduced by adding 5 μL of 100 mM DTT at 60°C for 30 min in the dark, alkylated by adding 5 μL of 200 mM iodoacetamide at 37°C for 30 min in the dark and vacuum dried for 30 min. Subsequently, the proteins were digested with trypsin (sequencing-grade modified trypsin, Sigma-Aldrich, USA; 1:25 w/w) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer by incubating overnight at 37°C. The trypsinization was inhibited by adding 1 μL of formic acid for 20 min at 37°C. The digested peptides were centrifuged at 20,817 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C for LC-MS/MS analysis. The peptides were analyzed by employing the two-dimensional (2D) nanoacquity UPLC® system coupled with Quadrupole-time of flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer (SYNAPT-G2-HDMS, Waters, UK). Both systems were operated and controlled by MassLynx4.1 SCN781 software. The peptide level fractionation were performed using reverse phase column 1 at high pH (pH-8) in the first dimension, followed by RP column 2 at low pH (pH 2) in the second dimension.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Peptides eluted from the nano-LC were subjected to mass spectrometric analysis on a SYNAPT® G2 High Definition MS™ System (Waters, UK). The parameters were used as described in Dharmaprakash et al. (2014). The mass spectrometer was operated in the “resolution mode” with a resolving power of 18,000 FWHM and the data was obtained in “continuum” format. The data was acquired by quickly alternating between low energy functions and high energy function. The LC-MS data were analyzed using ProteinLynx Global SERVER™ v2.5.3 (Waters, UK) as per Gopinath et al. (2015) for protein identification as well as for the relative protein quantification. Noise reduction thresholds for high energy scan ion and low energy scan ion, peptide intensity were fixed at 150, 50, and 500 counts, respectively. The NCBI reference sequence database for C. elegans was used for search, throughout the database search; the protein false discovery rate was set to 4%. Work flow was planned in such a way that a protein was necessary to have at least one fragment ion matches and one peptide match, whereas a peptide was required to have at least three fragment ion match. Mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm for precursor ions and 20 ppm for fragment ions. Trypsin was selected as the primary digest reagent, used with a specificity of one missed cleavage. Oxidation of methionine was selected as the variable modification and carbamidomethylation of cysteine was selected as the fixed modification.

Bioinformatics Analysis

High throughput protein profile and expression data were further subjected to bioinformatics analysis as per Schmidt et al. (2014). The gene ontology (GO) classification of differentially regulated proteins in this study was performed using the UniProt KB tool. Interaction among the differentially regulated proteins was performed using the STRING tool (Version 10.5) with a highest confidence score of 0.900. Functional annotation and gene enrichment scores of differentially regulated proteins were generated using the DAVID tool. The PANTHER tool was used to identify regulated protein class and pathways during toxin exposure (Myers et al., 2015; Villaveces et al., 2015).

Detection of Oxidants and Antioxidants

The L4 stage C. elegans were exposed to E. coli OP50 and PemKSa toxin. Both exposed and control worms were washed several times thoroughly. Subsequently, the bacteria free worms were homogenized and protein concentration was kept at 100 μg/mL. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured as per Scherz-Shouval et al. (2007) to study the level of ROS in host during PAO1 exposure. The H2O2 level in cell lysate supernatant was measured as described earlier (Wolff, 1994). SOD activity of C. elegans cell lysate supernatant (100 μg/mL of protein) was measured as per Paoletti and Mocali (1990). Catalase activity of C. elegans was measured as described earlier (Aebi, 1984). C. elegans carbonyl content was measured as per Levine et al. (1990). Each experiment was performed in biological triplicates and the error bars represent the mean ± SD (*p < 0.05).

Lipid Peroxidation Quantification

Lipid peroxidation was determined as described earlier (Ohkawa et al., 1979). Briefly, the C. elegans cell lysate supernatant contained (100 μg/mL of protein) in a 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was mixed with 1:1 of ice-cold 10% TCA and centrifuged at 1,100 × g for 20 min. Five different concentrations (100–500 ng) of malondialdehyde (MDA) were used as standard. Equal volumes of 0.33% of 2-Thiobarbituric acid (TBARS) dissolved in 50% glacial acidic acid was added to the supernatant and the samples were mixed gently and boiled at 100°C for 20 min. After incubation, the samples were allowed to cool at room temperature and absorbance was measured at 532 nm.

Extraction of C. elegans Lipids

Caenorhabditis elegans lipids were extracted as per Shi et al. (2016) with small modifications. Approximately, 10–12 large (10 cm) plates containing L4 stage C. elegans were washed from NGM plates, to a 24-well plate containing E. coli OP50 and PemKSa toxin for 24 hrs. After incubation, worms were washed thoroughly several times to remove the surface bound bacteria/ toxin proteins, and at −80°C. Lipids were extracted by adding 2 mL of ice-cold chloroform: methanol (1:1) to the frozen worm samples, mixed vigorously and incubated at −20°C overnight with occasional shaking. The following day, 400 μL of Hajra's solution (0.2 M H3PO4, 1M KCl) was added to each sample and mixed vigorously for a minute and centrifuged at 4,500 × g for minute which resulted separation of the organic and aqueous phase. The organic phase (lower chloroform phase) was removed and dried under CentriVap centrifugal vacuum concentrator and samples were directly used for Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic (FT-IR).

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis

FT-IR spectroscopic analysis for C. elegans lipids was carried out as per described in Sheng et al. (2016) to validate the alterations or possible functional group change of the C. elegans lipid structure during the host-toxin interactions. The infrared spectra of isolated lipid of L4 stage C. elegans were recorded on FT-IR (Nicolet iS5, Thermo Scientific, USA) spectrometer. The spectra were obtained using potassium bromide (KBr) pellet technique. Briefly, potassium bromide (AR grade) was dried under vacuum at 45°C for 1 h, and 50 mg of KBr was added to 1 mg of sample to prepare KBr pellet. The spectra were scanned in the 4,000–400 cm−1 range. All the IR spectra were plotted as absorbance units, vs. wave number using Origin software (JebaMercy et al., 2013).

Western Blotting

The protein content of whole cell extracts (at different time points of exposure) was prepared using 1X PBS buffer along with protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay. For each time point, 100–200 μg of total protein was boiled in 5X Laemmli's buffer for 3 min followed by short spin at 3,000 × g. The protein samples were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer on nitrocellulose membranes as described earlier (Durai et al., 2014). After transfer, the membranes were exposed to primary antibodies overnight at 4°C on a shaker. Before and after incubation with secondary antibodies the membranes were washed extensively using alkaline phosphate-buffer (TBS) containing Tween. The binding of antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence containing substrate nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4- chloro-3-indolyphosphate. The antibodies used in the present study were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. PDI [sc-20132], JNK-1[sc-571], p38 [sc-17852], HSF-1[sc-9144], HSF-90 [sc-1055], SGK-1 [sc-33774] RACK-1[17754], Caspases-3 [sc-7148], and beta-actin purified mouse immunoglobulin (A1978) purchased form (Sigma-Aldrich) working concentration was kept at 1:1,000–1:2,000.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed independently in triplicate. The statistical significance of data was analyzed by -one way ANOVA and Duncan test (SPSS Chicago, IL, USA) at significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Plasmid pETDuet1-PemKSa Expression

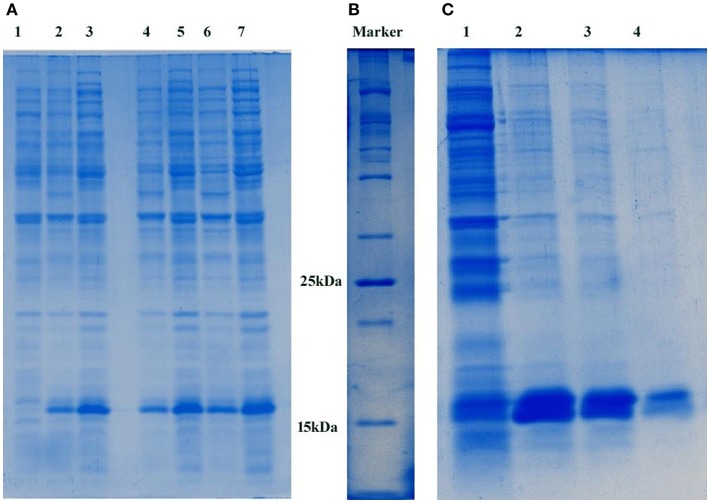

The pETDuet1-PemKSa plasmid which encodes a toxin protein (PemKSa; 112 amino acids) was transformed into E. coli DE3 cells, the desired recombinant cells are provided in Figure S1A. Plasmid DNA was extracted, and the purity of the plasmid was analyzed in 1% agarose gel as provided in Figure S1B. The extracted pETDuet1-PemKSa plasmid DNA was extracted (molecular weight of 5.5 kb) (Supplementary Figure 1C) and double digested using restriction enzyme (EcoR1 and Sac1). Purity of the digested plasmid was checked, a DNA bands were observed in the agarose gel with an approximate molecular weight of 1.5 kb and 750 bp, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1D). Upon induction with IPTG, E. coli DE3 cells carrying vector (pETDuet1-PemKSa) expressed large quantities of tagged His6-PemKSa protein, as evidenced by gradient SDS-PAGE. Approximately, the visualized protein band with an approximate molecular weight 16 kDa is PemKSa protein as provided in Figure 1A. The highest yields were obtained between 4 and 5 h after induction by 1 μL/1 mL of IPTG at 37°C temperature. Figure 1B is a 100 kDa protein marker. Un-induced culture showed some leaky expression of PemKSa toxin protein, whereas the culture induced by IPTG expressed the PemKSa protein in bulk quantity. The PemKSa toxin was purified per manufacturers protocol described under experimental procedures and purified elution fraction was analyzed by using the 12% SDS-PAGE as provided in Figure 1C.

Figure 1.

(A) Expression of PemKSa toxin protein. Lane 1 contains E. coli DE3 total cell lysate protein, Lanes 2, 4, and 6 contains uninduced total cell lysate protein of E. coli DE3. Lanes 3, 5, and 7 contains IPTG induced total cell lysate protein of E. coli DE3. Concentration: Lanes 1, 2, and 3 (50 μg) Lanes 4 and 5 (75 μg) and Lanes 6 and 7 (100 μg), respectively. (B) 100 kDa protein marker (C) Molecular weight corresponding to PemKSa is ~16 kDa. PemKSa protein was purified affinity binding analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. Lane 2, 3, and 4 contains purified elute fractions of PemKSa protein.

Killing Assay

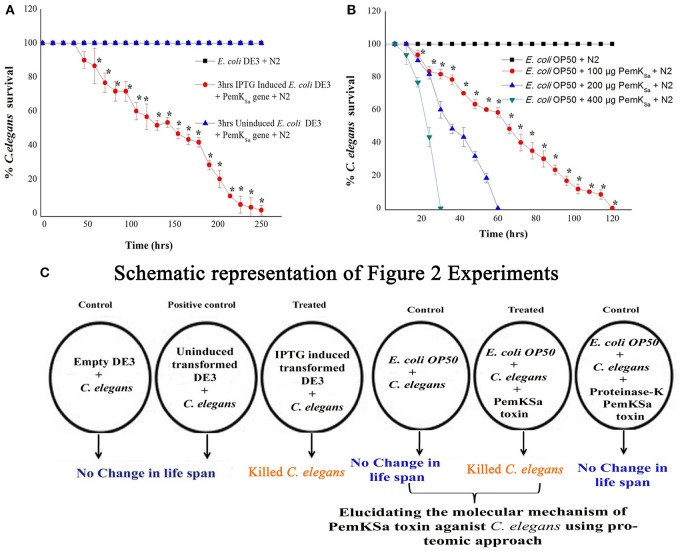

To evaluate the intoxication effect of a PemKSa toxin protein on bacterial-feeding nematode a liquid killing assay was performed C. elegans fed with IPTG induced E. coli DE3 (transformed) strain intoxicated the nematodes after exposure. In other side, C. elegans fed on wild type E. coli DE3 as well as with IPTG un-induced transformed cells not led mortality or any other adverse affect to nematodes. Quantitative result of this killing assay is graphically represented in Figure 2. In almost all cases where intoxication was seen, the nematodes were died within a time frame. However, IPTG induced DE3 PemKSa required 250 ± 10 h (p < 0.05) for the complete killing of C. elegans (Figure 2A). Killing assay time points revealed that the continuous exposure of C. elegans with 3 h IPTG induced E. coli DE3 in liquid media led to a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the life span of nematodes.

Figure 2.

Physiological assays showing the impact of PemKSa toxin proteins on C. elegans. (A) In liquid killing assays, IPTG induced E. coli DE3 significantly (p < 0.05) killed C. elegans at 250 ± 10 hrs. (B) In liquid killing assays, purified PemKSa toxin protein fractions caused complete killing of C. elegans concentration at 200 and 400 μg/mL killed C. elegans at 30 and 60 h, respectively. PemKSa protein concentration maintained at 400 μg/mL treated overnight with Proteinase-K enzyme at 37°C has not killed the nematode, which ensured death was due to protein only. (C) A graphically representation of the outcome of Figure 2. Each experiment was performed in triplicates. *Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

To determine the impact of PemKSa toxin on host, the nematode toxicity assay was performed with purified PemKSa toxin protein and killing ability of PemKSa on C. elegans were tested. In liquid killing assay, the N2 worms exposed with PemKSa toxin led to a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the life span of nematodes. PemKSa required 30 ± 2 h (p < 0.05) for the complete killing of C. elegans (Figure 2B). For LT50, (time for half to die) it required 15 ± 3 h. N2 C. elegans grown on control bacteria (worms in E. coli OP50) displayed a normal life span. Liquid killing assay revealed that the continuous exposure of C. elegans with PemKSa toxin causes mortality. The survival percentages of C. elegans in the presence of PemKSa toxin were significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared with the E. coli OP50. The purified PemKSa toxin protein completely killed C. elegans on 30, 60, and 120 h at the concentrations of 400, 200, and 100 μg, respectively. The PemKSa, toxin proteins fractions treated with proteinase-K overnight at 37°C showed no significant difference in the lifespan between control and worms exposed with proteinase-K treated PemKSa toxin protein fractions (Figure 2B). It suggested that the toxin protein fractions modulated the C. elegans lifespan and morphology after exposure. Each experiment was performed in biological triplicates and the error bars represent the mean ± SD (*p < 0.05).

Global Proteome Response of C. elegans Upon PemKSa Toxin Exposure

The total proteome of control and treated N2 C. elegans were initially analyzed using the SDS-PAGE in which prominent differential regulated protein bands were identified and listed as provided in Figure S2. The results of the killing assay and differential protein pattern of C. elegans on SDS-PAGE have lead us to investigate the primary molecular mechanism that have caused C. elegans mortality through proteomic approach using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify the proteins involved in C. elegans mortality and other physiological changes. Based on the post-MS data protein identification and expression analysis, a total of 601 differential regulated proteins were detected. The relative expression ratio of downregulated and upregulated proteins between control and treated samples was fixed as ≥-1.5 and ≥1.5, respectively, of all the biological replicates (p < 0.05). Among the 601 differentially regulated proteins 361 and 240 proteins were found to be downregulated and upregulated, respectively. The list of differentially regulated proteins is provided in Tables S1, S2. High throughput protein profile and expression data were further subjected to bioinformatic analysis.

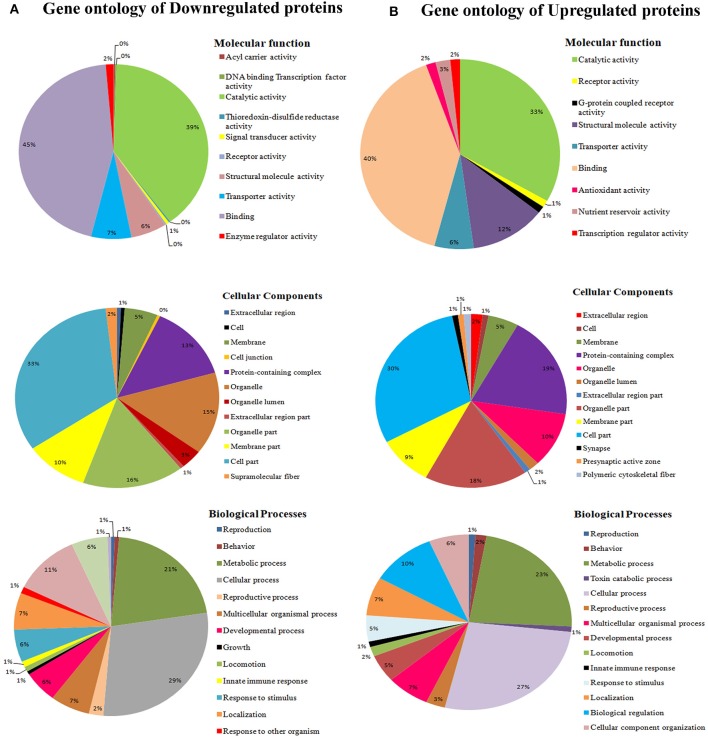

Gene Ontology Annotation for Differentially Regulated Proteins

To classify the regulated proteins of C. elegans exposed to PemKSa toxin into potential physiological functions. A Gene ontology (GO) annotation and functional enrichment analysis was carried out using the UniProtKB tool. The differentially regulated proteins were categorized into molecular functions, biological processes and cellular components. According to the GO functional annotation, the largest set of downregulated and upregulated proteins belongs to a functional groups involved in binding activity, catalytic activity and structural molecule activity. The predominant biological processes of differentially regulated proteins are involved in the metabolic process and cellular process as shown in Figures 3A,B. Several identified regulated proteins are involved in Na2+ and Ca2+ voltage gated channels which lead to degradation in the synapses of neurons and immune response pathway.

Figure 3.

(A) Gene ontology analysis using the UniProtKB online tool showed downregulated proteins are involved in binding activity, catalytic activity, cell parts, cellular processes, single organism process, metabolic processes locomotion, oxidative stress, and developmental processes. (B) Whereas, C. elegans upregulated proteins are involved catalytic activity, receptor activity, cell part, macromolecular complex, and metabolic processes.

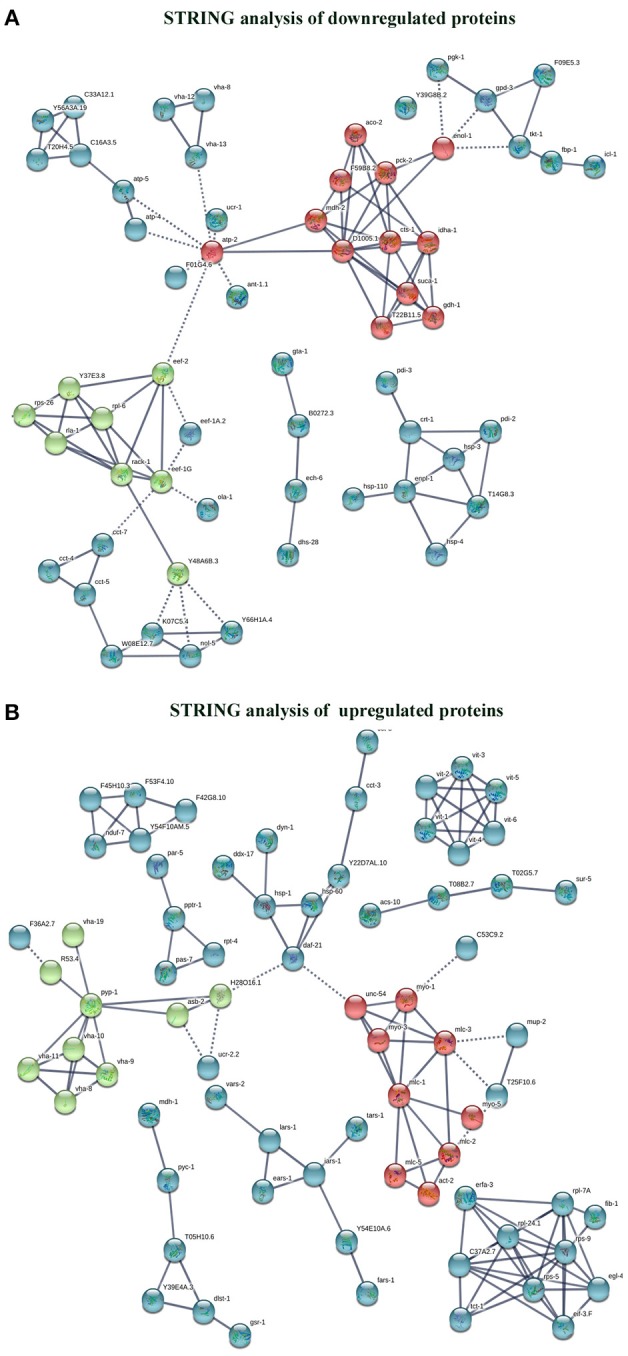

The interactome network using STRING tool was built separately for both downregulated and upregulated proteins to find out the interaction among regulated proteins and predicted the functional association. The interaction map of downregulated proteins displayed the relationship between molecular players involved in translation, ATP biosynthesis and metabolism, ETC chain, chaperon, adult life span, ribosome biogenesis, cytochrome family and oxidation-reduction processes (Figure 4A). The proteins associated with these processes either directly interacting with each other, or interact through their partners. The potential deregulation pathways connected with PemKSa intoxication was identified using the STRING and PANTHER tools. The pathways mostly downregulated by PemKSa toxin are presented in Table 1. The STRING analysis of upregulated proteins show interaction between HSP proteins with PDI-6 (stress proteins), ATP synthetic subunits (H28016.1), ribosomal proteins (RPL-2), and MYO-3 and UNC-54 (muscle proteins), presented in Figure 4B. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling pathway is the major upregulated pathway connected with PemKSa intoxication in C. elegans presented in Table 1. Protein classes mostly affected by PemKSa toxin are presented in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Interactome map among regulated proteins was performed using STRING tool with a highest confidence threshold score (0.900). The interaction map showed link between identified regulated proteins of C. elegans. (A) The downregulated proteins showed interaction among translation, ATP biosynthesis, ETC chain, chaperon, cytochrome c family, nucleotide binding, and oxidation-reduction responsible proteins. (B) Whereas, upregulated proteins showed interaction between HSP, stress, muscle, mitochondrial, and ribosomal proteins.

Table 1.

Several pathways regulated in C. elegans during PemKSa toxin protein exposure were identified using online PANTHER tool [downregulated (D); upregulated (U)].

| S. No | PANTHER pathways | Expected | Fold enrichment | Raw P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ATP synthesis (D) | 0.11 | 27.64 | 3.91E-04 | 7.42E-03 |

| 2 | Pyruvate metabolism (D) | 0.16 | 25.80 | 4.73E-05 | 1.80E-03 |

| 3 | TCA cycle (D) | 0.12 | 24.18 | 5.31E-04 | 8.97E-03 |

| 4 | Glycolysis (D) | 0.17 | 23.45 | 6.37E-05 | 1.61E-03 |

| 5 | Parkinson disease (D) | 0.82 | 12.17 | 3.73E-08 | 2.83E-06 |

| 6 | Cytoskeletal regulation by Rho GTPase (D) | 0.48 | 10.40 | 2.05E-04 | 4.46E-03 |

| 7 | Ubiquitin proteasome pathway (D) | 0.60 | 9.92 | 5.96E-05 | 1.81E-03 |

| 8 | Apoptosis signaling pathway (D) | 0.47 | 8.60 | 1.72E-03 | 2.62E-02 |

| 9 | Huntington disease (D) | 0.98 | 8.19 | 1.25E-05 | 6.32E-04 |

| 10 | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling pathway (U) | 0.67 | 8.97 | 8.13E-05 | 6.18E-03 |

Table 2.

PemKSa intoxication has regulated several protein classes identified using online PANTHER tool.

| PANTHER protein class | Expected | Fold enrichment | Raw P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage protein | 0.07 | 87.46 | 9.83E-10 | 3.87E-08 |

| Chaperonin | 0.09 | 34.98 | 1.62E-04 | 2.46E-03 |

| Chaperone | 0.38 | 13.25 | 5.91E-05 | 1.16E-03 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.17 | 23.32 | 4.70E-05 | 1.03E-03 |

| Ligase | 1.54 | 5.83 | 3.56E-05 | 8.76E-04 |

| ATP synthase | 0.23 | 17.28 | 1.33E-04 | 2.18E-03 |

| Cation transporter | 1.01 | 5.93 | 6.76E-04 | 8.32E-03 |

| Ribosomal protein | 1.08 | 16.66 | 3.17E-16 | 3.12E-14 |

| RNA binding protein | 4.12 | 6.06 | 1.32E-12 | 8.68E-11 |

| Nucleic acid binding | 8.22 | 3.77 | 2.67E-10 | 1.31E-08 |

| Dehydrogenase | 1.44 | 7.64 | 3.93E-07 | 1.11E-05 |

| Oxidoreductase | 3.39 | 5.02 | 9.01E-08 | 2.96E-06 |

| Translation factor | 0.58 | 6.86 | 3.31E-03 | 3.84E-02 |

| Actin family cytoskeletal protein | 1.04 | 6.75 | 1.13E-04 | 2.03E-03 |

| Cytoskeletal protein | 2.27 | 3.96 | 5.79E-04 | 7.61E-03 |

| Hydrolase | 8.20 | 2.44 | 2.46E-04 | 3.47E-03 |

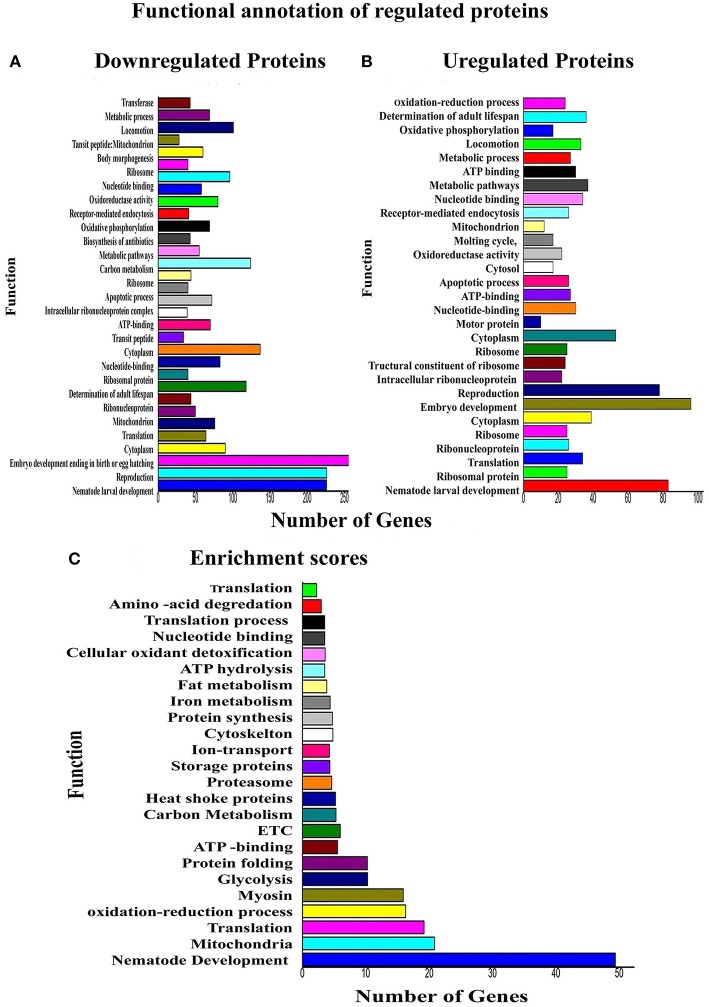

Functional Annotation and Gene Enrichment Score

Regarding the functional annotation reflects the nature of biology, whereby one protein could play multiple roles in different biological processes. Functional annotation of downregulated [N = 361] and upregulated [N = 240] proteins was performed using the DAVID tool. Physiological functions that are highly affected in response to PemKSa toxin proteins exposure are embryo development; reproduction, nematode development and cytoplasm are presented in Figures 5A, B. The biological functions that have the highest protein enrichment scores of differentially regulated proteins in response to PemKSa exposure are nematode development, mitochondrion, translation, and oxidation reduction processes are presented in Figure 5C.

Figure 5.

Functional annotations and protein enrichment scores of regulated proteins was performed using the DAVID tool. (A) The biological functions which have more number of downregulated proteins in response to PemKSa toxin exposure were embryo development; nematode development and reproduction. (B) Biological Functions which contains more number of upregulated proteins against toxin exposure is embryo development. (C) Physiological function having highest protein enrichment scores is nematode development and mitochondrial functions.

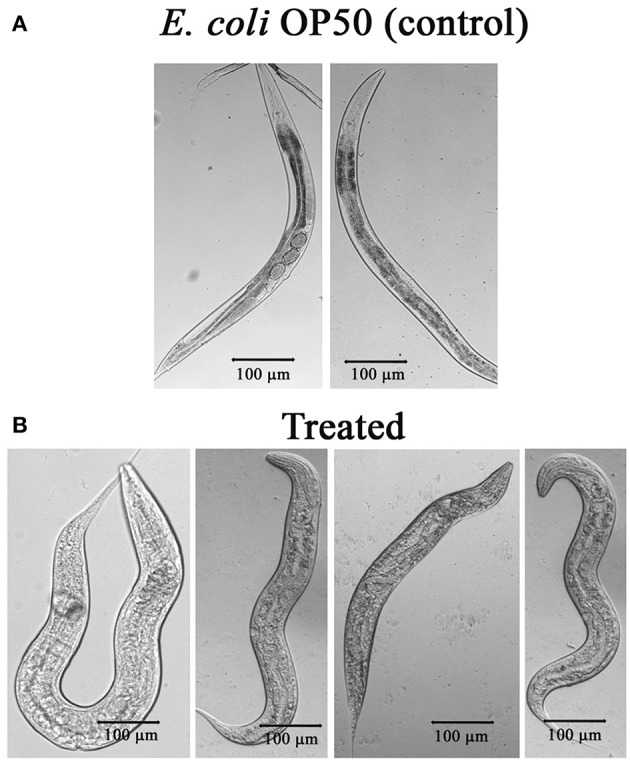

PemKSa Toxin Affected Nematodes Intestine

The mechanism of toxicity of Bt crystal proteins toward insects is accepted that it damages the gut of nematode (Wei et al., 2003). To study the impact of the PemKSa intoxication on nematode morphology, microscopic images [Nikon Eclipse Ti-S, Japan] of toxin exposed C. elegans were analyzed. Size of the worms was determined and compared by taking the photographs. The results showed, the intoxicated worms have full swollen body, damaged and disintegrated underlying inner body tissues, and digestive track (Figure 6). This microscopic data representing the morphological defects in C. elegans during toxin exposure are corroborated with the mass spectrometric data where the downregulation of muscle and cuticle collagen related genes (dpy-18, ifb-1, mua-6, unc-15, myo-2, act-1, dim-1, tba-2, cct-1, cutl-5, tba-1, tba-8, pfn-1, and pfn-2) was ascertained.

Figure 6.

(A) Microscopic images of C. elegans exposed with E. coli OP50. (B) C. elegans exposed with PemKSa toxin (concentration 100–200 μg/mL) showed full swollen body morphology, damaged and disintegrated underlying inner body tissues.

Regulation of Oxidant and Antioxidant Proteins of C. elegans

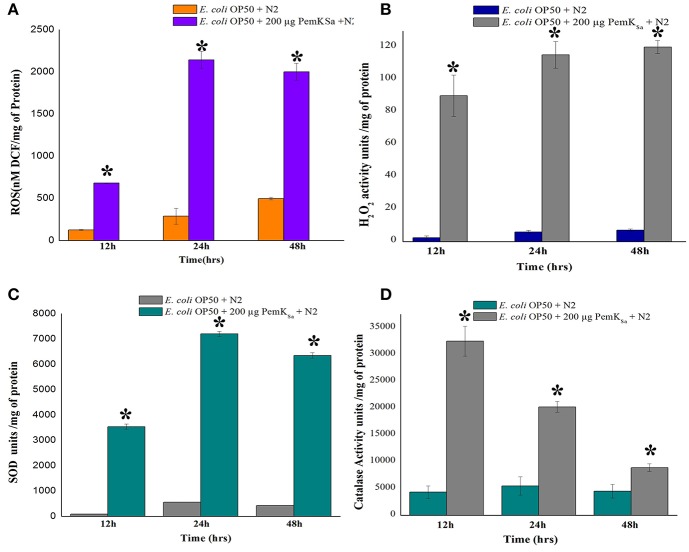

Several stress and chaperones proteins (PDI-2, ENPL, HSPs, PDI-1/2/3, SODH-1, CCT-1/2/3/7, TRX-4, DAF-21, GST-5/36, CDC-48.1, IIF-2, KAT-1, and RNP-6) were identified to be differentially regulated during PemKSa exposure to C. elegans. This result lead us to suspect whether expression of oxidant proteins in nematode during intoxication have induced the generation of ROS as a protective measurement. To investigate this, we determined the levels of ROS using 2′, 7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) staining. ROS induction was examined at three-time points (12, 24, and 48 h), it was found that ROS generation was higher in worms exposed to PemKSa toxin compared with that of control (fed with OP50 food source) as presented in Figure 7A. To assess the hydrogen peroxide level of the PemKSa toxin exposed C. elegans at three time points (12, 24, and 48 h). It was found that H2O2 generation was significantly higher in exposed samples compared with that of control worms, for all the three time points as presented in Figure 7B.

Figure 7.

Quantitative analysis of oxidant and antioxidant proteins of control and treated C. elegans. (A) ROS estimation, (B) H2O2 estimation, (C) Quantification of SOD activity, and (D) Quantification of catalase activity. Data were expressed as mean value of three experiments and the error bars represent Mean ± SD (*p < 0.05).

The antioxidant enzymatic proteins serve as a key factor to maintain the redox homeostasis. In this study the expression of antioxidant proteins viz, glutathione reductase (GSR-1), peroxiredoxin (PRDX-3), probable glutathione S-transferase 5/36 (GST-5/36), superoxide dismutase enzyme (SOD), peroxidise (SKPO-1), thioredoxin (TRX) have corroborated well with the in vivo detection of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) associated ROS generation which directly leads to the accumulation of molecular damage. The expression levels of antioxidant enzymes (SOD and CTL) were also measured to determine the extent to which increased antioxidant defenses could account for the observed levels of oxidative damage in L4 stage worms. The estimation of SOD was evaluated in both control and treated samples at three different time points (12, 24, and 48 h). The measurement of SOD alone showed significant increase of 10-fold in treated L4 stage animals, compared with that of control as presented in Figure 7C. SOD acts as a scavenger for toxic superoxide radical, which is concerned in lipid peroxidation. The significantly increased activity of SOD may be due to compensatory efforts generated by SOD to combat oxidative stress. Quantitative spectrophotometric analysis of catalase activity of L4 stage nematodes exposed to PemKSa toxin protein showed significantly high catalase activity at 12 and 24 h time points compared with that of control fed with E. coli OP50 as presented in Figure 7D. The mean activity values of catalase enzyme were decreased in treated samples at 48 h. The decreased activity of catalase at 48 h treated samples compared with that of controls, suggested the rescue against hydrogen peroxide free radicals and other oxidative stresses appeared to be reduced in C. elegans.

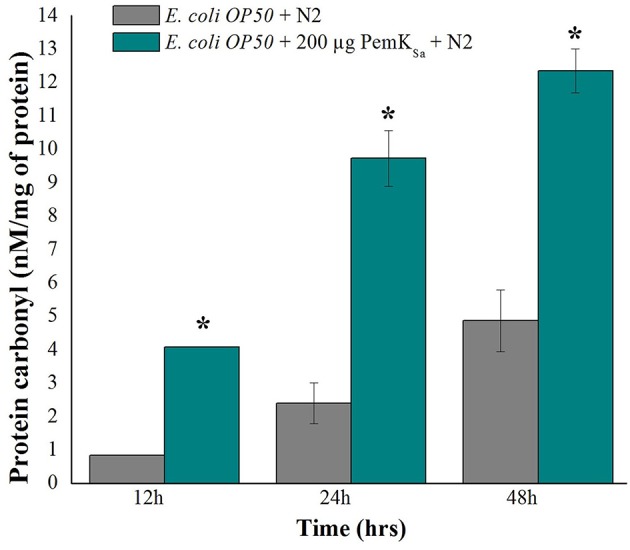

Estimation of C. elegans Protein Carbonyl Content

The protein carbonyl content is a molecular marker to test SOD. The protein carbonyl contents were evaluated in both control and treated samples at three different time points (12, 24, and 48 h) by 2, 4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine. Worms exposed with PemKSa toxin protein extensively showed an enhanced level of protein carbonyl content 12.3 ± 1.20 nM/mg compared with that of the control C. elegans as presented in Figure 8. Prominent high levels of protein carbonyls in treated sample could be caused by a decrease in the turnover rate of the oxidized proteins or by an increase in protein oxidation. In the present study, a number of identified proteins appear to be responsible for amino acid degradation and some marker proteins were regulated in this study which plays a key role to degrade (proteasome activity) the oxidized proteins.

Figure 8.

Protein carbonyls content quantification of control and PemKSa treated C. elegans for three time points (12, 24, and 48 h) showed significant low carbonyl content in control fed with E. coli OP50. Data were expressed as mean value of three experiments and the error bars represent SD ± mean (*p < 0.05).

PemKSa Toxin Regulated the Lipid Metabolism Related Proteins

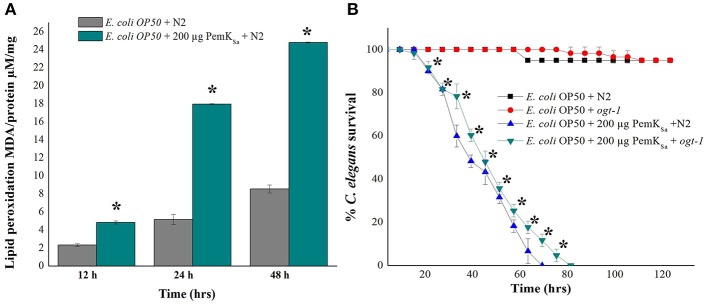

Lipid metabolism related proteins which were identified to be regulated in this study include: ADS-1, DHS-28, NPA-1, POD-2, ACBP-1, AAGR-4, PCK-1, TPI-1, T25B9.9, DLAT-1, LBP-6, NMT-1, ALH-9, IBP-6, RIBO-1, SUP-46, FBP-1, FAT-6, PCK-1/2, ADS-1, PGK-1, GSY-1, ACS-11, and Y37D8A.2. Regulation of these proteins indicated an alteration of fat storage molecules in living organism. To validate the fat and lipid deposition change in exposed C. elegans, lipid peroxidation assay was performed. Quantifying a lipid peroxidation is an effective way to measure the effect of oxidative damage. Concurrent estimation of C. elegans lipid peroxidation for both control and treated samples at three time points (12, 24, and 48 h) showed the significantly higher level of Thiobarbituric acid (TBARS) formation by H2O2 induced lipid peroxidation in the treated C. elegans samples compared with that of control as presented in Figure 9A. C. elegans ogt-1 mutant encodes truncated O-linked N-acetylglucosamine proteins that lacks catalytic activity to promote glycosylation as well as the storage of fats and lipid. In liquid a killing assay, toxin protein exposed ogt-1 mutant worms showed complete mortality at 75 ± 5 h, where the mean life span of ogt-1 mutant is higher than mean life span of wild type N2 worms exposed to toxin proteins. On the other hand, the wild type N2 and mutant ogt-1 worms fed with E. coli OP50 food source showed zero mortality as presented in Figure 9B.

Figure 9.

(A). Lipid peroxidation quantification of control and treated C. elegans for three time points (12, 24, and 48 h) showed high lipid peroxidation in toxin exposed C. elegans samples compared with that of control. (B) In liquid killing assay PemKSa toxin protein exposed ogt-1 mutant worm showed significant (p < 0.05) more survival rate 80 ± 5 h compared with that of wild type N2 worms. However, the mutant and wild type N2 worms fed with E. coli OP50 showed normal life. Data were expressed as mean value of three experiments and the error bars represent SD ± mean (*p < 0.05).

FT-IR Analysis of C. elegans Lipids

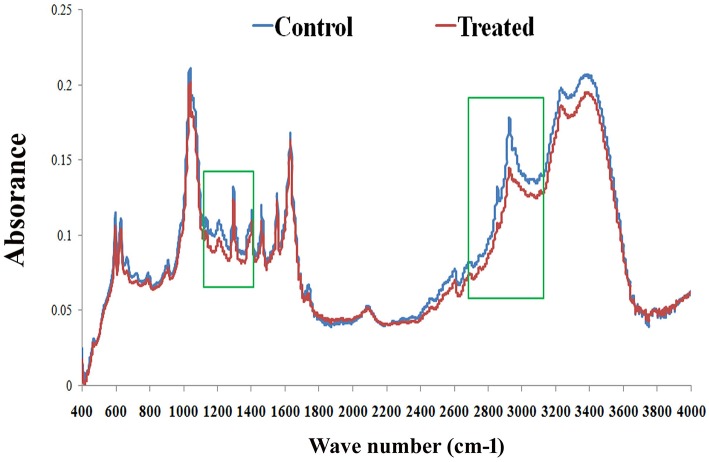

FT-IR analysis was carried out to examine the effect of PemKSa treatment on C. elegans lipids. FT-IR has been used as a potent tool to study biomolecular complex structures (Stuart, 2012). The FT-IR analysis of C. elegans fatty acids showed prominent intensity peak differences between the control and treated samples (Figure 10). The results showed major signature peak difference at 3,000–2,800 cm−1 corresponding to fatty acids (Helm et al., 1991), compared to control. The treated sample showed lower intensity at 3,100 cm−1 (N-H stretching of proteins attached with lipids) (Akkas et al., 2007), 2,930 cm−1 (CH2 anti-symmetric stretch of lipids), 2,870 cm−1 (CH3 symmetric stretching of lipids) (Melin et al., 2000; Toyran and Severcan, 2003), 2,450 cm−1 (C-O-C asymmetric stretching of glycogen and nucleic acids) C = O cm−1 (stretching of phospholipids compared with that of control), and 1,250–1,150 cm−1(PO2 asymmetric stretching of phospholipids). It evidenced that the spectral differences were observed to be in the C. elegans fatty acids region. These findings suggested that the impact of toxin protein on fat molecules in a host system. Variation in the FT-IR spectra of toxin treated sample has corroborated the results of LC-MS/MS and lipid peroxidation assay.

Figure 10.

FT-IR analysis of C. elegans lipids. The representative FT-IR spectra of lipids (control and treated) in the 4,000–400 cm−1 region. However, the average FT-IR spectra of the control and treated showed major signature peak difference at 3,000–2,800 cm−1 (fatty acids). Data were expressed as mean value of three experiments and the error bars represent SD ± mean (*p < 0.05).

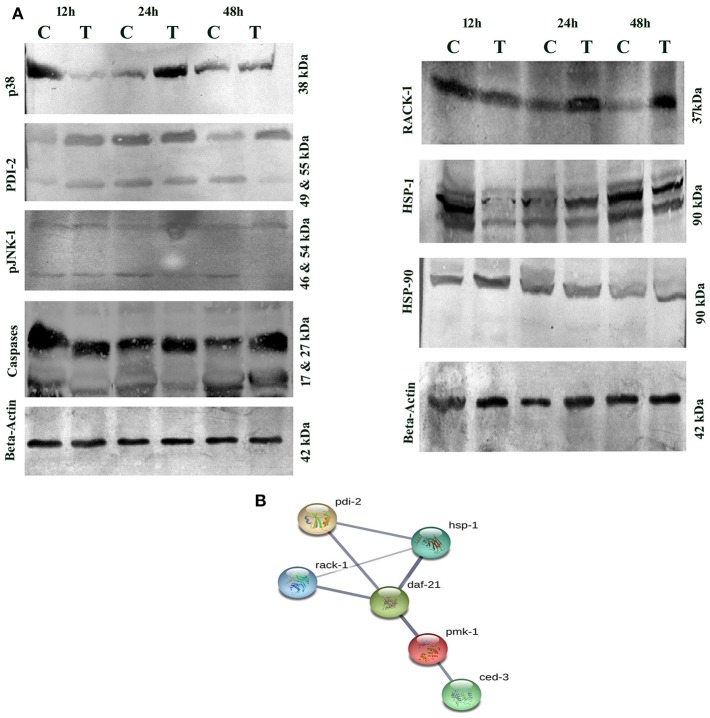

PemKSa Toxin Regulated Innate Immunity Proteins Validated by Western Blotting

Several host immune-responses (JNK and MAP Kinase pathways) proteins were differentially regulated and validation analysis of these proteins was performed through Western blotting analysis. Inadequate or excessive expressions of JNK and MAP Kinase pathway specific proteins have adverse immune response consequences. The expression patterns of p38 and JNK-MAPK pathway coupled proteins through Western blotting analysis showed high abundance of p38 upto 24 h and low abundance at 48 h. Beta-actin was used as the internal control as presented in Figure 11A. During host-toxin interaction several stress proteins were regulated [for example, PDI-1/2/36/ CRT-1, TPI-1, NHR-57, CST-1, CBS-1, GSR-1, GST-5/36, PRDX-3, PPTRA-1, KAT-1, SODH-1]. PDI-2 encodes disulfide isomerase, assist in protein folding and stress. The PDI-2 in particular, was detected and monitored by immunoblotting. The study showed high abundance of PDI-2 in treated sample compared with that of control. The Western blot results clearly supported the differential expression of PDI-2 during toxin exposure as presented in Figure 11A. PDI-2 results showed that the relative fold change of three isoforms of PDI-2 protein in worms during exposure with PemKSa toxin in a time course manner. PDI-2 protein regulates expression of the HSP-4 and HSP-1. RACK protein showed upregulation, whereas HSP-90 showed downregulation. The isoform of pJNK-1 protein (46 kDa) was downregulated at 12 and 24 h, whereas protein had diminished as the exposure time of PemKSa toxin was exceeded upto 48 h.

Figure 11.

(A) Western blotting analysis of C. elegans JNK and MAP Kinase pathway specific proteins (p38, PDI-2, pJNK, caspases, RACK-1, HSP-1/90, and SGK) were performed. C. elegans exposed with E. coli OP50 and toxin proteins at 12, 24, and 48 h a pathway specific proteins were detected using the specific antibodies. The protein expression level at each time point was normalized to that of β-actin. PDI-2 is stress responsible protein which is found to assist in protein folding. (B). UniportKB protein-protein interaction showed close association and interaction between PMK-1(p38), RACK-1, PDI-2, HSF-1, and HSF-4 Proteins.

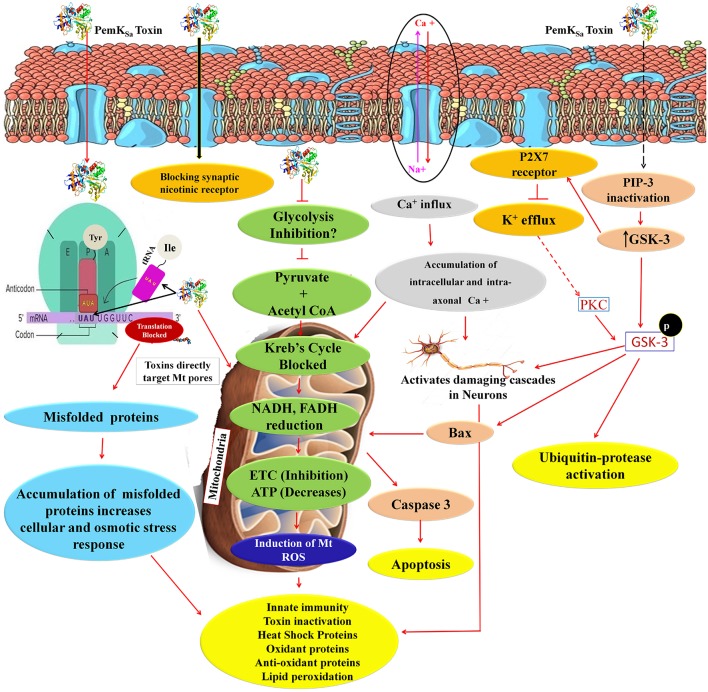

Altered metabolic process and the extent of an oxidative stress induce native apoptotic pathways. Several proteins responsible for phagocytosis and apoptosis (NDK-1, TFG-1, CDKR-1 ASP-1, CCM-3, IFF-2, CAR-1, ICD-1, DYN-1, and ARF-1.2) were found to be regulated in our study. The caspases-3 (CED-3) in particular, was detected and monitored by immunoblotting and p38 (PMK-1) protein showed interaction with CED-3 as presented in Figure 11B. The study showed upregulation of CED-3 protein (active caspases) in treated samples compared with that of the controls. The molecular weight of two active caspases isoforms are 17 and 27 kDa, respectively, as presented in Figure 11A. An overview of proteins and pathways activated and targeted by the PemKSa toxin in C. elegans are presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

An overview of proteins and pathways activated and targeted by PemKSa toxin in C. elegans. PemKSa is sequence-specific endoribonuclease recognizing the tetrad sequence UAUU mRNA and cut it between U and A nucleotides. Chances are that PemKSa in present study might targeted the codon of Tyrosine and anticodon of Isoleucine UAU, it either degrade the mRNA or stopped the protein synthesis, or generate mutated proteins which lack the native confirmation. Toxins are directly targeting the host cell mitochondria and blocks the voltage gated channels and other important pores. Inhibition of glycolysis will also decrease coenzyme NADH and FADH which act as reduced powers and inhibit the ETC. PemKSa might be blocking synaptic nicotinic receptor and affect or degenerate the C. elegans neurons. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), is a component of cell membrane that activates numerous signaling pathways resulting in cell proliferation, growth, survival, glucose transport and protein synthesis. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), a serine-threonine kinase, is an important component of the glycogen metabolism pathway. It is highly expressed in neurons for development and repair which activates ubiquitin-protease for degradation. GSK-3 inhibiting phase II gene expression in the oxidative stress defense. Inhibition or blockage of voltage gated Na2+, Ca2+, and K2+ channels play a critical role in the generation and propagation of action potentials in neurons and muscle cells. Protein kinase C (PKC-1) phosphorylates a range of cellular proteins. Which acts as an extracellular signal regulated mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK), in response to diverse sensory neurons. Its role in regulation differs depending on the neuron in which it is acting. Required for incomplete resistance to antimitotic toxins. In C. elegans an increased ROS, H2O2 and expression of other oxidant proteins activates innate immunity and anti-oxidant proteins for toxin inactivation.

Discussion

In this study, we have assessed the impact of S. aureus PemK toxins on the C. elegans. The studies have revealed toxin does not merely affect the nematode lifespan/ survival and fertility and survival, but also causes significant damage to the nematode intestine and fat storage. In survival assays, E. coli DE3 expressing PemKSa toxin protein caused significant mortality in C. elegans. We have also analyzed the C. elegans proteome to decipher the key differentially regulated players responsible for mediating virulent toxin determinants. A unique aspect in our experimental setup is constant presence of laboratory food source (bacterium E. coli OP50) even during toxin proteins exposure which avoided starvation-induced stress-responses in C. elegans. Hence, it appears that most, if not all the identified differentially regulated 601 proteins in our study are attributed to the PemKSa toxin interaction with the host system. This data infers C. elegans cells devote such a large portion of their proteins for defensive roles against toxins which also appear to cause membrane damage. The antioxidant enzymatic proteins were upregulated in treated samples might be to defend and counteract with ROS hydroxyl radicals (OH) and superoxide anions (O2-), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

The highest confidence interaction map of downregulated proteins displayed the relationship between proteins responsible for generation and hydrolysis of ATP (ATP-2, VH-13), protein synthesis (eEF-2), carbohydrate metabolic process (MDH-2), fatty acid biosynthetic process (D1005.1), chaperonins (CCT-7), heat shock proteins (HSP), neuro transmission (GTA-1), and stress proteins (PDI). STRING analysis of upregulated proteins showed relationship between DAF-21, oxidative stress, protein folding, dephosphorylation, metabolic process, lipid transport activity, nutrient reservoir activity and oxidation-reduction process. Based on interactome analyses, the requirement of p38 and JNK MAPK pathways for PemKSa toxin defenses were examined. MAPK pathway is induced in mammalian and C. elegans cells by pore forming toxins PFTs (Stassen et al., 2003; Aguilar et al., 2009). RACK protein which is a multifaceted regulator and essential factor of C. elegans innate immunity against infection was downregulated in our study (Marudhupandiyan et al., 2017).

PemKSa toxin protein downregulates several molecular players related to lipid metabolism indicate alteration of C. elegans lipid metabolism. POD-2 encodes acetyl-CoA carboxylase, the rate limiting enzyme of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis (Shi et al., 2016). The ADS-1 (Alkyl-Dihydroxyacetone phosphate synthase) protein is an ortholog of human AGPS (Alkylglyceron phosphate synthase). The ads-1 gene is encoding the protein required for ether lipid biosynthetic pathway initial steps (Shi et al., 2016). The dhs-28 causes negative regulation of lipid storage (Joo et al., 2009). The acbp-1 encodes acyl-CoA-binding protein required for lipid storage and transport (Elle et al., 2011). Several downregulated proteins responsible for lipid catabolic reactions, gluconeogenesis, carbohydrate degradation, and activation of pentose phosphate pathway predict degradation or peroxidation of lipids.

FT-IR data revealed the dramatically altered of C. elegans LPS constituents, the polysaccharide (1,250–1,150 cm−1), fatty acid (3,000–2,800 cm−1), and glycoprotein (1,200–900 cm−1) regions during the toxin exposure. Modification of C. elegans LPS and glycoproteins might be due to enhance the efficacy of the toxins or could be due to severity of toxin action on host. Glycosylation is a specific enzymatic process which involves many functional proteins resulting in a great diversity of carbohydrate-protein bonds and glycan structures. Various proteins responsible for the addition of sugars to the N- or the C-terminus of protein to form N- and O-glycans are found to be downregulated in this study (RIBO-1, OSTD-1, CRT-1, NMT-1, and LBP-1). RIBO-1 and OSTD-1 are an essential subunit of the N-oligosaccharyl transferase complex which catalyzes the transfer of a high mannose oligosaccharide from a lipid-linked oligosaccharide donor to an asparagine residue within an Asn-X-Ser/Thr consensus motif in nascent polypeptide chains.

Galectins are a group of lectins that bind β-galactoside-containing carbohydrates. The interaction of lectins with its target carbohydrate can be highly specific and allows this class of protein to participate in development, immunity, and cancer defense (Yang et al., 2008; Boscher et al., 2011). In addition, some of the C. elegans galectins have been confirmed to confer the diverse range of stress responses (Ideo et al., 2009). In this study, four galectins were regulated in which LEC-2, and LEC-4 were downregulated and LEC-1 and LEC-5 were upregulated at total protein, implying that galectin appears to be involved in the defense response of worm against toxin. Our studies are corroborated with the previous reports where it is stated that galectins (LEC-1, LEC-2, LEC-5, LEC-6, LEC-8, LEC-9, LEC-10, LEC-1081, and LEC-182) provide an immediate response during toxin exposure and oxidative stress (Griffitts et al., 2005; Ideo et al., 2009; Nemoto-Sasaki and Kasai, 2009; Takeuchi et al., 2013) Thus, our findings also supported the earlier studies on the regulatory roles of galectins of the host during the defense against toxins.

In this study, PemKSa intoxication has remarkably downregulated the expression level of HSP (HSP-3/6/12.2/60/70/110, ENPL-1, CCT-3/4/5/7/8, CYN-7, and GPD-3), whereas, HSP-4 and HSP-90 were highly abundant. C. elegans upon interaction with adverse environmental stimulator, bacterial infection and even physiological stressor, respond through rapid molecular changes for survival. HSPs are highly evolutionarily conserved molecular chaperones, which gives immediate responses during any stress, tissue damage, or bacterial infection (Frydman, 2001; Prithika et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). PemKSa intoxication has altered the expression level of HSPs and other proteins which play crucial role in pathological conditions by modulating the structurally denatured or misfolded proteins and prevent the proteins that retain its native conformation (Soti et al., 2005; Powers et al., 2010). Moreover, our C. elegans protein analysis during PemKSa exposure also identified stress-specific and immune response proteins (SODH-1, NHR-57, LYS-1, MOAC-1, and PYP-1), apoptosis-specific proteins (NDK-1, FEH-1, TGF-1, CDKR-3, DYN-1, and CCM-3) and another 35 proteins that are differentially regulated, all are responsible for cytoskeleton.

In conclusion, this study provided a preliminary view of molecular response of C. elegans toward a toxin at protein level, and provided insight into highly complex host-toxin interactions. Regulation of MAPK signal pathway, JNK, galectins, HSPs were observed for the first time to participate in the defense responses of worms against toxin proteins. This provided a novel insight into the mechanism of how eukaryotic system might respond to toxin. Our data indicate that PemKSa toxin causes paralysis, oxidative stress; protein misfolding and neuronal toxicity in the host system and triggers activation of cell death pathways.

Author Contributions

DM designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data. KB wrote the manuscript in consultation with DM.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institute of Health, National Center for Research Resources for providing the nematode strains. We also thank Dr. Benedykt Wladyka Malopolska, Center of Biotechnology, Gronostajowa Krakow, Poland for kind gift of pETDuet1-PemKSa vector. We also wholeheartedly thank Dr. Kamaladevi A for submission of our proteomics data on PRIDE public repository. Mr. Dilawar Ahmad Mir gratefully acknowledges the University Grants Commission (UGC) of India for the computational facility provided by the Bioinformatics Infrastructure Facility, Alagappa University funded by the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India [Grant No.BT/BI/25/015/2012 (BIF)] are thankfully acknowledged. We are also grateful for the Instrumentation Facility provided by Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India through DST PURSE [Grant No. SR/S9Z-415 23/2010/42(G)], DST FIST [Grant No.SR-FST/LSI-087/2008] and UGC through SAP-DRS1 [Grant No.F. 3-28/2011(SAP-II)] and RUSA 2.0.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00172/full#supplementary-material

(A,B) Transformation of pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Plasmids were inserted into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells using calcium chloride mediated heat shock method. Transformed cells were selected in LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 mg/L). plates-A contains, plates-B contains the DE3 transformed cells by pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid (C) Confirmation of pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid by restriction digestion. Lane-1 contains 1 kb ladder, lane-2 undigested pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid, and lane-3 pETDuet-PemKSa digested plasmid (by EcoR1, size: 5.5 kb). (D) Double digested plasmid by (EcoR1 and Sac1), forms band at the position of 1,500 and 700 bp.

C. elegans total proteome (SDS-PAGE) after interaction with PemKSa toxin proteins. Lane (1 and 3) is N2 control sample exposed by E. coli OP50 and Lane (2 and 4) is N2 treated sample exposed by PemKSa toxin proteins.

List of downregulated proteins present in C. elegans (control sample) identified using LC-MS/MS.

List of upregulated proteins present in C. elegans (treated sample) identified using LC-MS/MS.

References

- Aebi H. (1984). Catalase in vitro. Meth. Enzymol. 105, 121–126. 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar J. L., Kulkarni R., Randis T. M., Soman S., Kikuchi A., Yin Y., et al. (2009). Phosphatase-dependent regulation of epithelial mitogen-activated protein kinase responses to toxin-induced membrane pores. PLoS ONE 4:e8076. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkas S. B., Severcan M., Yilmaz O., Severcan F. (2007). Effects of lipoic acid supplementation on rat brain tissue: an FTIR spectroscopic and neural network study. Food Chem. 105, 1281–1288. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alouf J. E. (2003). Molecular features of the cytolytic pore-forming bacterial protein toxins. Folia Microbiol. 48, 5–16. 10.1007/BF02931271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. L., Cole R. D., Williams P. L. (2004). Assessing behavioral toxicity with Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 23, 1235–1240. 10.1897/03-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian R., Van Der Goot F. G. (2007). Pore-forming toxins and cellular non-immune defenses (CNIDs). Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 57–61. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellier A., Chen C. S., Kao C. Y., Cinar H. N., Aroian R. V. (2009). Hypoxia and the hypoxic response pathway protect against pore-forming toxins in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000689 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof L. J., Kao C. Y., Los F. C., Gonzalez M. R., Shen Z., Briggs S. P., et al. (2008). Activation of the unfolded protein response is required for defenses against bacterial pore-forming toxin in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000176. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscher C., Dennis J. W., Nabi I. R. (2011). Glycosylation, galectins and cellular signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 383–392. 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd W. A., Cole R. D., Anderson G. L., Williams P. L. (2003). The effects of metals and food availability on the behavior of Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22, 3049–3055. 10.1897/02-565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo A., de Torrontegui G., Díaz R. (1987). Identification of components of a new stability system of plasmid R1, ParD, that is close to the origin of replication of this plasmid. Mol. Gen. Genet. 210, 101–110. 10.1007/BF00337764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo A., Gill S. S., Soberón M. (2007). Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt toxins and their potential for insect control. Toxicon 49, 423–435. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974).The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski M., Lyzen R., Helbin W. M., Bonar E., Szalewska-Palasz A., Wegrzyn G., et al. (2013). A regulatory role for Staphylococcus aureus toxin-antitoxin system PemIKSa. Nat. Commun. 4:2012. 10.1038/ncomms3012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlinson P., Studholme D., Cambray-Young J., Heavens D., Rathjen J., Hodgkin J., et al. (2013). Pseudomonas fluorescens NZI7 repels grazing by Caenorhabditis elegans, a natural predator. ISME J. 7, 1126–1138. 10.1038/ismej.2013.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmaprakash A., Mutt E., Jaleel A., Ramanathan S., Thomas S. (2014). Proteome profile of a pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus SC192 strain in the planktonic and biofilm condition. Biofouling 30, 729–739. 10.1080/08927014.2014.916696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durai S., Singh N., Kundu S., Balamurugan K. (2014). Proteomic investigation of Vibrio alginolyticus challenged Caenorhabditis elegans revealed regulation of cellular homeostasis proteins and their role in supporting innate immune system. Proteomics 14, 1820–1832. 10.1002/pmic.201300374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elle I. C., Simonsen K. T., Olsen L. C., Birck P. K., Ehmsen S., Tuck S., et al. (2011). Tissue-and paralogue-specific functions of acyl-CoA-binding proteins in lipid metabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. J. 437, 231–241. 10.1042/BJ20102099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J. (2001). Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 603–647. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M. R., Bischofberger M., Pernot L., Van Der Goot F. G., Freche B. (2008). Bacterial pore-forming toxins: the (w) hole story? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 493–507. 10.1007/s00018-007-7434-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath V., Raghunandanan S., Gomez R. L., Jose L., Surendran A., Ramachandran R., et al. (2015). Profiling the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during dormancy and reactivation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 2160–76. 10.1074/mcp.M115.051151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffitts J. S., Haslam S. M., Yang T., Garczynski S. F., Mulloy B., Morris H., et al. (2005). Glycolipids as receptors for Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin. Science 307, 922–925. 10.1126/science.1104444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasshoff M., Böhnisch C., Tonn D., Hasert B., Schulenburg H. (2007). The role of Caenorhabditis elegans insulin-like signaling in the behavioral avoidance of pathogenic Bacillus thuringiensis. FASEB J. 21, 1801–1812. 10.1096/fj.06-6551com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm D., Labischinski H., Schallehn G., Naumann D. (1991). Classification and identification of bacteria by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Microbiology 137, 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz H. R. (2003). Worms, life, and death (Nobel lecture). Chembiochem 4, 697–711. 10.1002/cbic.200300614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman D. L., Abrami L., Sasik R., Corbeil J., van der Goot F. G., Aroian R. V. (2004a). Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways defend against bacterial pore-forming toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10995–11000. 10.1073/pnas.0404073101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman D. L., Bischof L. J., Griffitts J. S., Aroian R. V. (2004b). Pore worms: using Caenorhabditis elegans to study how bacterial toxins interact with their target host. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293, 599–607. 10.1078/1438-4221-00303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideo H., Fukushima K., Gengyo-Ando K., Mitani S., Dejima K., Nomura K., et al. (2009). A Caenorhabditis elegans glycolipid-binding galectin functions in host defense against bacterial infection. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26493–26501 10.1074/jbc.M109.038257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JebaMercy G., Vigneshwari L., Balamurugan K. (2013). A MAP Kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans is required for defense against infection by opportunistic Proteus species. Microbes Infect. 15, 550–568. 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo H. J., Yim Y. H., Jeong P. Y., Jin Y. X., Lee J. E., Kim H., et al. (2009). Caenorhabditis elegans utilizes dauer pheromone biosynthesis to dispose of toxic peroxisomal fatty acids for cellular homoeostasis. Biochem. J. 422, 61–71. 10.1042/BJ20090513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen E. M., Mango S. E. (2002). The art and design of genetic screens: Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 356–369. 10.1038/nrg794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaletta T., Hengartner M. O. (2006). Finding function in novel targets: Caenorhabditis elegans as a model organism. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 387–399. 10.1038/nrd2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C. (2005). The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell 120, 449–460 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. L., Garland D., Oliver C. N., Amici A., Climent I., Lenz A.-G., et al. (1990). Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 186, 465–478. 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marudhupandiyan S., Prithika U., Balasubramaniam B., Balamurugan K. (2017). RACK-1, a multifaceted regulator is required for Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity against S. flexneri M9OT infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 74, 227–236 10.1016/j.dci.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarrese P., Falzano L., Fabbri A., Gambardella L., Frank C., Geny B., et al. (2007). Clostridium difficile toxin B causes apoptosis in epithelial cells by thrilling mitochondria involvement of ATP-sensitive mitochondrial potassium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9029–9041. 10.1074/jbc.M607614200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin A. M., Perromat A., Deleris G. (2000). Pharmacologic application of Fourier transform IR spectroscopy: in vivo toxicity of carbon tetrachloride on rat liver. Biopolymers 57, 160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melstrom P. C., Williams P. L. (2007). Measuring movement to determine physiological roles of acetylcholinesterase classes in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Nematol. 39, 317–320. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J. S., von Lersner A. K., Robbins C. J., Sang Q. X. A. (2015). Differentially expressed genes and signature pathways of human prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 10:e0145322. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi M., Selin C., Brassinga A. K. C., Belmonte M. F., Fernando W. D., Loewen P. C., et al. (2015). Pyrrolnitrin and hydrogen cyanide production by Pseudomonas chlororaphis strain PA23 exhibits nematicidal and repellent activity against Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 10:e0123184. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto-Sasaki Y., Kasai K. I. (2009). Deletion of lec-10, a galectin-encoding gene, increases susceptibility to oxidative stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 32, 1973–1977. 10.1248/bpb.32.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yagi K. (1979). Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 95, 351–358. 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti F., Mocali A. (1990). Determination of superoxide dismutase activity by purely chemical system based on NAD (P) H oxidation. Methods Enzymol. 186, 209–220. 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86110-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Lopez L., Soberon M., Bravo A. (2012). Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal three-domain Cry toxins: mode of action, insect resistance and consequences for crop protection. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 3–22. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers M. V., Jones K., Barillari C., Westwood I., Montfort R. L. V., Workman P. (2010). Targeting HSP70: the second potentially druggable heat shock protein and molecular chaperone? Cell Cycle 9, 1542–1550. 10.4161/cc.9.8.11204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prithika U., Deepa V., Balamurugan K. (2016). External induction of heat shock stimulates the immune response and longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans towards pathogen exposure. Innate Immun. 22, 466–478. 10.1177/1753425916654557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajini P. S., Melstrom P., Williams P. L. (2008). A comparative study on the relationship between various toxicological endpoints in Caenorhabditis elegans exposed to organophosphorus insecticides. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 71, 1043–1050. 10.1080/15287390801989002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2006). Preparation and transformation of competent E. coli using calcium chloride. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2006:pdb-prot3932. 10.1101/pdb.prot3932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz-Shouval R., Shvets E., Fass E., Shorer H., Gil L., Elazar Z. (2007). Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 26, 1749–1760. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A., Forne I., Imhof A. (2014). Bioinformatic analysis of proteomics data. BMC Syst. Biol. 8:S3. 10.1186/1752-0509-8-S2-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg H., Müller S. (2004). Natural variation in the response of Caenorhabditis elegans towards Bacillus thuringiensis. Parasitology 128, 433–443. 10.1017/S003118200300461X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M., Gorzsás A., Tuck S. (2016). Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy for the analysis of the biochemical composition of Caenorhabditis elegans worms. Worm 5:e1132978). 10.1080/21624054.2015.1132978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Tarazona P., Brock T. J., Feussner I., Watts J. L. (2016). A Caenorhabditis elegans model for ether lipid biosynthesis and function. J. Lipid Res. 57, 265–275. 10.1194/jlr.M064808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soti C., Nagy E., Giricz Z., Vígh L., Csermely P., Ferdinandy P. (2005). Heat shock proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 146, 769–780. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stassen M., Muller C., Richter C., Neudörfl C., Hultner L., Bhakdi S., et al. (2003). The streptococcal exotoxin streptolysin O activates mast cells to produce tumor necrosis factor alpha by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-and protein kinase C-dependent pathways. Infect. Immun. 71, 6171–6177. 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6171-6177.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiernagle T. (2006). Maintenance of Caenorhabditis elegans WormBook: The Online Review of Caenorhabditis elegans Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart B. H. (2012). “Infrared spectroscopy of biological applications,” in Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry: Applications, Theory and Instrumentation (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.). 10.1002/9780470027318.a0208.pub2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J. E. (2003). Caenorhabditis elegans the cell lineage and beyond (Nobel lecture). Chembiochem 4, 688–696. 10.1002/cbic.200300577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T., Nemoto-Sasaki Y., Sugiura K. I., Arata Y., Kasai K. I. (2013). Galectin LEC-1 plays a defensive role against damage due to oxidative stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biochem. 154, 455–464. 10.1093/jb/mvt074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M. W. (2002). Identification of host and pathogen factors involved in virulence using Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Enzymol. 358, 13–28. 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)58078-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyran N., Severcan F. (2003). Competitive effect of vitamin D2 and Ca2+ on phospholipid model membranes: an FTIR study. Chem. Phys. Lipids 123, 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaveces J. M., Koti P., Habermann B. H. (2015). Tools for visualization and analysis of molecular networks, pathways, and-omics data. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. 8:11. 10.2147/AABC.S63534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Wang H., Xiong J., Zhou Q., Wu H., Xia L., et al. (2017). A proteomic analysis provides novel insights into the stress responses of Caenorhabditis elegans towards nematicidal Cry6A Toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis. Sci. Rep. 7:14170. 10.1038/s41598-017-14428-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J. Z., Hale K., Carta L., Platzer E., Wong C., Fang S. C., et al. (2003). Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins that target nematodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2760–2765. 10.1073/pnas.0538072100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S. P. (1994). Ferrous ion oxidation in presence of ferric ion indicator xylenol orange for measurement of hydroperoxides. Meth. Enzymol. 233, 182–189. 10.1016/S0076-6879(94)33021-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R. Y., Rabinovich G. A., Liu F. T. (2008). Galectins: structure, function and therapeutic potential. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 10:e17. 10.1017/S1462399408000719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Luo H., Xiong J., Zhou Q., Xia L., Sun M., et al. (2014). Bacillus thuringiensis Cry6A exhibits nematicidal activity to Caenorhabditis elegans bre mutants and synergistic activity with Cry5B to Caenorhabditis elegans. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 58, 511–519. 10.1111/lam.12219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Peng D., Ye X., Yu Z., Hu Z., Ruan L., et al. (2012). In vitro uptake of 140 kDa Bacillus thuringiensis nematicidal crystal proteins by the second stage juvenile of Meloidogyne hapla. PLoS ONE 7:e38534. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A,B) Transformation of pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Plasmids were inserted into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells using calcium chloride mediated heat shock method. Transformed cells were selected in LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 mg/L). plates-A contains, plates-B contains the DE3 transformed cells by pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid (C) Confirmation of pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid by restriction digestion. Lane-1 contains 1 kb ladder, lane-2 undigested pETDuet-PemKSa plasmid, and lane-3 pETDuet-PemKSa digested plasmid (by EcoR1, size: 5.5 kb). (D) Double digested plasmid by (EcoR1 and Sac1), forms band at the position of 1,500 and 700 bp.

C. elegans total proteome (SDS-PAGE) after interaction with PemKSa toxin proteins. Lane (1 and 3) is N2 control sample exposed by E. coli OP50 and Lane (2 and 4) is N2 treated sample exposed by PemKSa toxin proteins.

List of downregulated proteins present in C. elegans (control sample) identified using LC-MS/MS.

List of upregulated proteins present in C. elegans (treated sample) identified using LC-MS/MS.