Abstract

Background:

Worldwide, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer affecting women. The five most frequent cancers affecting women in India are breast, cervical, oral cavity, lung, and colorectal cancer. More women die from cervical cancer in India than in any other country. Cancers of major public health relevance such as breast, oral, cervical, gastric, lung, and colorectal cancer can be cured if detected early and treated adequately. The objective of this study was to assess the knowledge and attitudes toward cervical cancer screening and prevention.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 100 professional college female students to obtain information about their knowledge and attitudes on cervical cancer screening and prevention.

Results:

In this study, we intended to assess the knowledge and attitudes toward cervical cancer screening and prevention among 100 professional college female students with a mean age of 18 years. All the respondents were single. Majority of the respondents were not aware about the cervical cancer, PAP smear testing, and human papillomavirus vaccine.

Conclusion:

These results indicate that most of the students participated in our study were not aware about the cervical cancer screening and prevention. Deaths resulting from cervical cancer are tragic as this type of cancer develops slowly, which is treatable and can be prevented through screening. Therefore, it is important that negative attitudes and gaps in knowledge should be addressed early before the women reach suitable ages for screening and vaccination.

KEYWORDS: Cervical cancer, HPV vaccine, PAP smear

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer affecting women and the seventh most common cancer overall; however, the burden of cervical cancer is not equal globally. Around 85% of the global burden occurs in the less-developed regions, where cervical cancer accounts for almost 12% of all female cancers.[1] Cancer is the second most common cause of death in India (after cardiovascular disease). The five most frequent cancers affecting women in India are breast, cervical, oral cavity, lung, and colorectal cancer. More women die from cervical cancer in India than in any other country. Cancers of major public health relevance such as breast, oral, cervical, gastric, lung, and colorectal cancer can be cured if detected early and treated adequately. In India, there is need for more health education to sensitize the public of the health effects of cervical cancer. Although cervical cancer screening has been offered in India, only a few females know about it.[2] Those who are aware of it have different perceptions or attitudes toward cervical cancer screening. The objective of this study was to assess the knowledge and attitudes toward cervical cancer screening and prevention.

PRIMARY CAUSE OF CERVICAL CANCER

The primary cause of cervical cancer is human papillomavirus (HPV). Infection with one or more of these oncogenic HPV types is the underlying cause of almost all cases of cervical cancer. It has been demonstrated that more than 99.7% cervical cancers test positive for HPV DNA worldwide. Currently, 15 oncogenic types of HPV are recognized. HPV types 16, 18, and 45 are most predominantly associated with cervical cancer.[3] Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and cleared by the immune system within a year. However, in up to 10% women, the infection can persist, and in a very small number of women, persistent infection with oncogenic HPV may eventually lead to cervical cancer.[4]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

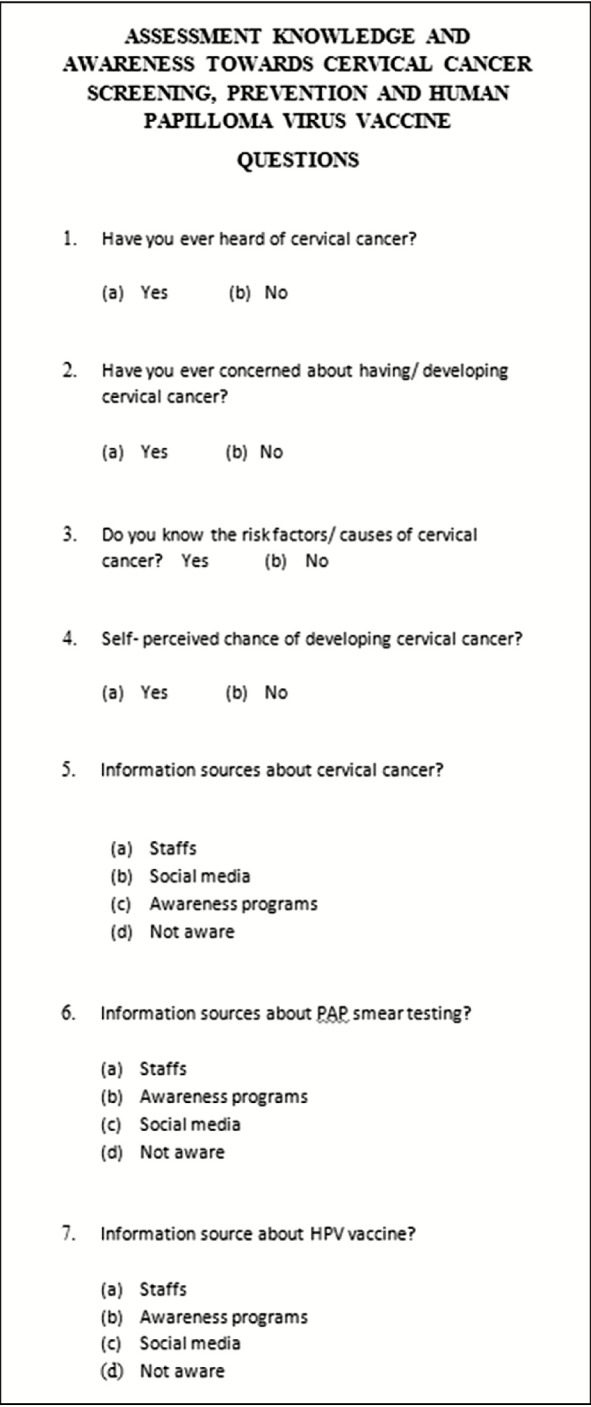

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in October 2018 among 100 female students who were aged between 18 and 24 years. The samples were selected using multistage sampling technique. The students were asked to complete the questionnaire [Figure 1]. Informed consent was obtained from the participants at the time of completing the questionnaire. The survey was self-administered and anonymous, and the completed surveys were returned to research assistants.

Figure 1.

Awareness questionnaire

Data collection methods

Self-administered structured questionnaires were used to collect information from the students. The questionnaires collected data from individuals to assess the knowledge, attitude, and utilization of cervical cancer screening among the students. The information collected was used to answer the objective of study and to recommend the intervention necessary to increase the cervical cancer screening among females. The questionnaires were all in English as all respondents were proficient in the language.

Data management

The data collected were entered and analyzed using SPSS software, version 20 (IBM, Chicago, IL). Entered data were checked for completeness; incomplete data were not computed.

RESULTS

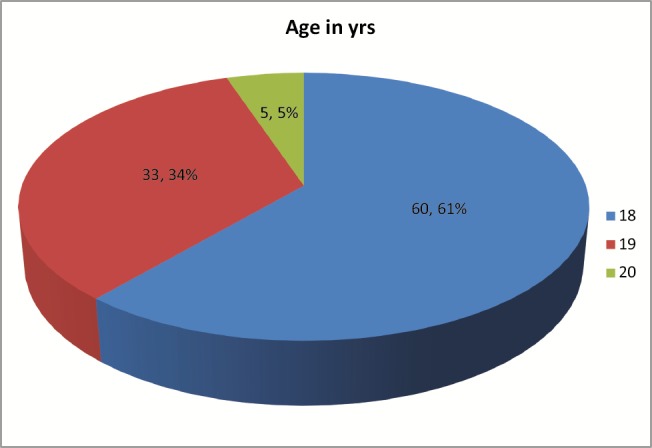

In this study, we intended to assess the knowledge and attitudes toward cervical cancer screening and prevention among 100 students studying in a professional college for women. A total of 100 questionnaires were completed and returned. The mean age of the students was 18 years (Table 1, Graph 1). All the respondents were single.

Table 1.

Distribution of age of the students

| Age (years) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 18 | 60 | 61.22 |

| 19 | 33 | 33.67 |

| 20 | 5 | 5.10 |

| Total | 98 | 100.00 |

Graph 1.

Distribution of age of the students

Awareness about cervical cancer

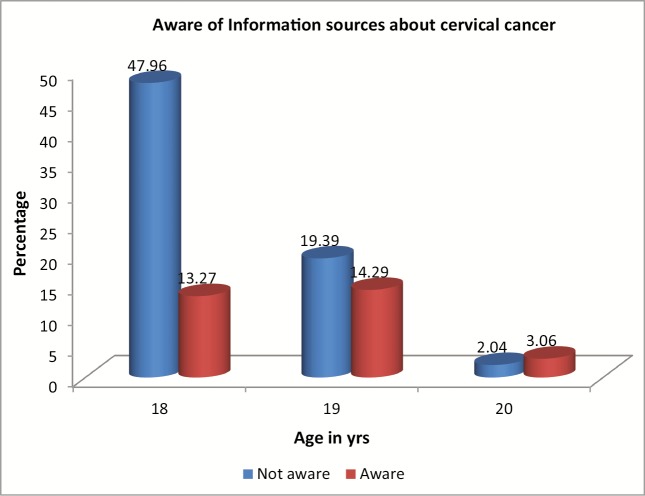

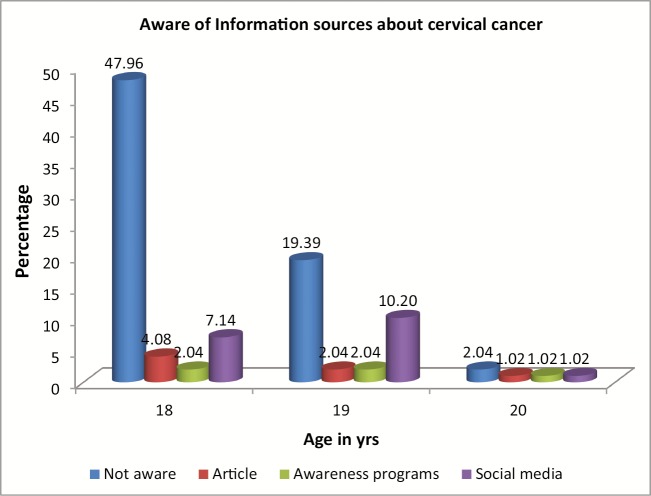

As shown in Table 2 and Graph 2, 68 (69.39%) respondents indicated that they were not aware about cervical cancer, whereas 30 (30.61%) respondents indicated that they had some awareness about cervical cancer and they indicated getting knowledge about cervical cancer from articles 7 (7.14%), awareness programs 5 (5.10%), and from social media 18 (18.37%) as shown in Table 3 and Graph 3 (P = 0.131).

Table 2.

Distribution of awareness about cervical cancer

| Age (years) | Aware of information sources about cervical cancer | Total | Chi square | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 18 | 47 | 47.96 | 13 | 13.27 | 60 | 61.22 | 6.46 | 0.040* |

| 19 | 19 | 19.39 | 14 | 14.29 | 33 | 33.67 | ||

| 20 | 2 | 2.04 | 3 | 3.06 | 5 | 5.10 | ||

| Total | 68 | 69.39 | 30 | 30.61 | 98 | 100.00 | ||

*Significant at 5%.

Graph 2.

Distribution of awareness about cervical cancer

Table 3.

Distribution of information sources about cervical cancer

| Age (years) | Information sources about cervical cancer | Total | Chi square | P | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Article | Awareness | Social media | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 18 | 47 | 47.96 | 4 | 4.08 | 2 | 2.04 | 7.00 | 7.14 | 60.00 | 61.22 | 9.84 | 0.131 |

| 19 | 19 | 19.39 | 2 | 2.04 | 2 | 2.04 | 10.00 | 10.20 | 33.00 | 33.67 | ||

| 20 | 2 | 2.04 | 1 | 1.02 | 1 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 5.00 | 5.10 | ||

| Total | 68 | 69.39 | 7 | 7.14 | 5 | 5.10 | 18.00 | 18.37 | 98.00 | 100.00 | ||

Graph 3.

Distribution of information sources about cervical cancer

Knowledge about the risk factors/causes of cervical cancer

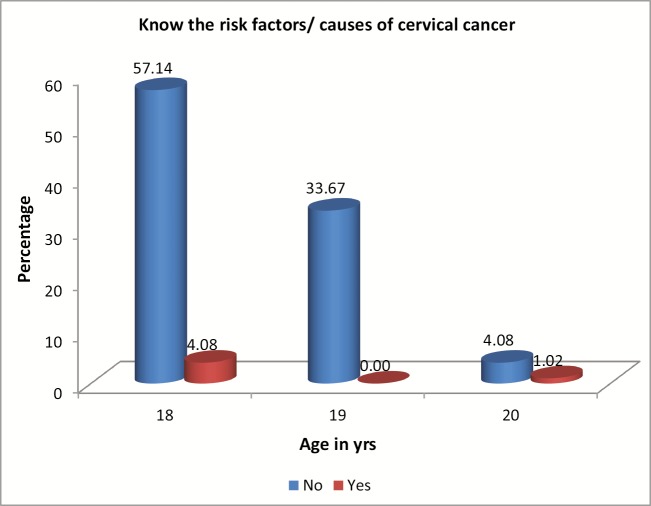

As shown in Table 4 and Graph 4, only 5 respondents (5.1%) were aware about the risk factors and causes of cervical cancer, whereas the majority of respondents were not aware about them (P = 0.112).

Table 4.

Distribution of knowledge about the risk factors/causes of cervical cancer

| Age (years) | Know the risk factors/causes of cervical cancer | Total | Chi square | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 18 | 56 | 57.14 | 4 | 4.08 | 60 | 61.22 | 4.37 | 0.112 |

| 19 | 33 | 33.67 | 33 | 33.67 | ||||

| 20 | 4 | 4.08 | 1 | 1.02 | 5 | 5.10 | ||

| Total | 93 | 94.90 | 5 | 5.10 | 98 | 100.00 | ||

Graph 4.

Distribution of knowledge about the risk factors/causes of cervical cancer

Awareness of information sources about PAP smear testing

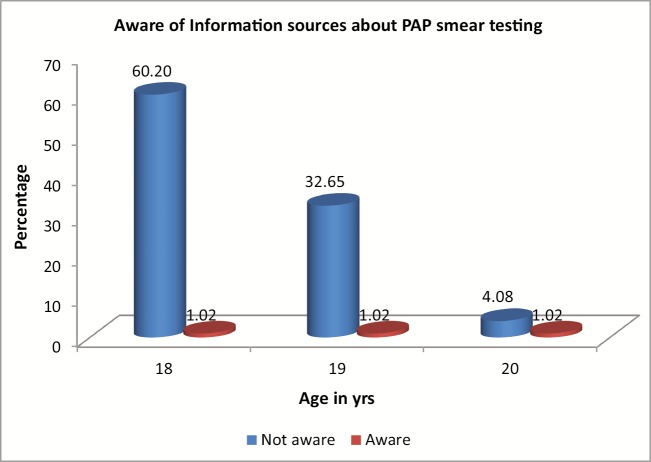

As shown in Table 5 and Graph 5, 96 (97.96%) respondents indicated that they were not aware about PAP smear testing, whereas 2 (2.04%) respondents indicated that they had some awareness about it (P = 0.073).

Table 5.

Distribution of awareness of information sources about PAP smear testing

| Age (years) | Aware of information sources about PAP smear testing | Total | Chi square | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 18 | 59 | 60.20 | 1 | 1.02 | 60 | 61.22 | 5.23 | 0.073 |

| 19 | 33 | 33.67 | 33 | 33.67 | ||||

| 20 | 4 | 4.08 | 1 | 1.02 | 5 | 5.10 | ||

| Total | 96 | 97.96 | 2 | 2.04 | 98 | 100.00 | ||

Graph 5.

Distribution of awareness of information sources about PAP smear testing

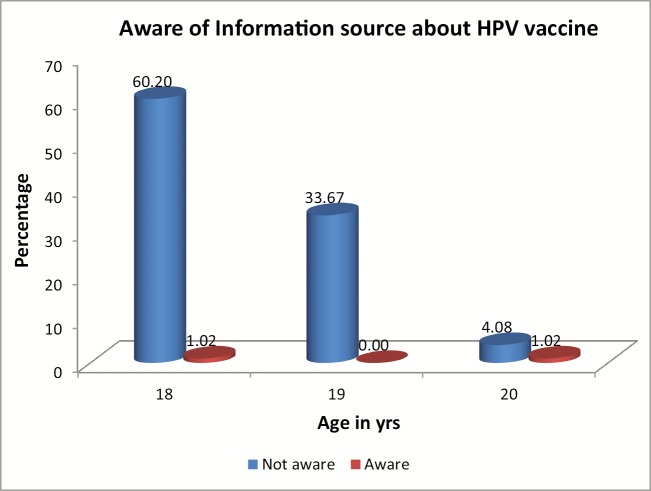

Awareness of information sources about HPV vaccine

As shown in Table 6 and Graph 6, 96 (97.96%) respondents indicated that they were not aware about HPV vaccine, whereas 2 (2.04%) respondents indicated that they had some awareness about it (P = 0.012).

Table 6.

Distribution of awareness of information source about HPV vaccine

| Age (years) | Aware of information source about HPV vaccine | Total | Chi square | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 18 | 59 | 60.20 | 1 | 1.02 | 60 | 61.22 | 8.80 | 0.012* |

| 19 | 33 | 33.67 | 33 | 33.67 | ||||

| 20 | 4 | 4.08 | 1 | 1.02 | 5 | 5.10 | ||

| Total | 96 | 97.96 | 2 | 2.04 | 98 | 100.00 | ||

*Significant at 5%.

Graph 6.

Distribution of awareness of information source about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine

DISCUSSION

Cervical cancer is largely preventable. The role of HPV in the development of cervical cancer allows for the implementation of the prevention of cervical cancer. Primary prevention of cervical cancer is through vaccination against HPV, via the National HPV Vaccination Program, to prevent women being infected with oncogenic HPV types that cause the majority of cervical cancer.[5] Secondary prevention of cervical cancer is through cervical screening, via the National Cervical Screening Program, to detect and treat abnormalities while they are in the precancerous stage, before possible progression to cervical cancer.[6] This is possible because cervical cancer is one of the few cancers that have a precancerous stage that lasts for many years prior to the development of invasive disease, which provides an opportunity for detection and treatment. The strength of cervical screening comes from repeating the screening test at agreed rescreening intervals, which allows more accurate detection of precancerous abnormalities over the long preinvasive stage of squamous cervical cancers.[7] Recognition of cervical screening as a program of rescreening at regular intervals rather than as a single opportunistic test was important.[8] Detection of precancerous abnormalities through cervical screening used cytology from the Papanicolaou smear, or “PAP test,” as the screening tool, with cells collected from the transformation zone of the cervix—the area of the cervix where the squamous cells from the outer opening of the cervix and glandular cells from the endocervical canal meet (where most cervical abnormalities and cancers are detected).[9] The aim of the screening PAP test was to identify those women who may have a cervical abnormality (as indicated by the presence of abnormal cells in the specimen collected) and therefore require further diagnostic testing.[10] Detecting precancerous changes to cells allows for intervention before cervical cancer develops; however, it is important to recognize that some cervical cancers do not have a precancerous stage, and therefore, cannot be detected by cervical screening. These tend to be rare but aggressive cancers, such as neuroendocrine cancer of the cervix.[11] The two most aggressive types are small- and large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, neither of which appears to have a preinvasive stage. In 2018, use of the new nonavalent HPV vaccine, Gardasil9, replacing the quadrivalent vaccine, Gardasil, thereby protecting against an additional six strains of HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), was recommended. The program began in line with the school year and reduced the number of doses from three to two(spaced 6–12 months apart).[12] The introduction of this vaccine will further improve the protection that females vaccinated against HPV have against the development of cervical intra epithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. In addition, by moving to the nonavalent vaccine, and decreasing the number of recommended doses, the rate of compliance with the vaccination schedule is expected to increase. Most of the participants did not undergo PAP smear screening because they thought they were underaged, 35% did not see the need for a PAP smear test, and 16.5% did not know where it was done; this may be because they perceived themselves as not at risk of developing cervical cancer.[13]

Most students thought that the purpose of a PAP smear test is to detect existing cervical cancer. Many of the reasons advanced by respondents can be labeled as misconceptions that require widespread public education, with a new emphasis on the crucial fact that PAP smear screening is targeted primarily at detecting precursor lesions that occur early in the course of the disease, and subsequent timely treatment would thus impede progress toward invasive cancer.[14] Women should be encouraged to take responsibility for their own health and be active participants in the screening program.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study revealed the limited knowledge about the susceptibility of cervical cancer and the necessity for cervical cancer screening and prevention among the female students. We should thus concentrate on informing students about the risk factors for cervical cancer by carrying out awareness campaigns, every semester of which should focus more or make emphasis on the benefits of screening and vaccination. As a way of increasing screening among the students, screening services should be incorporated into the existing medical services. It is important to offer students emotional support, as they might be experiencing fear and anxiety on the results of the PAP smears should they take the test. National HPV vaccination coverage for female adolescents turning 15 years of age is highly recommended.[15]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Nov 20]. Available from: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs380/en/

- 2.Hoque E, Hoque M. Knowledge of and attitude towards cervical cancer among female university students in South Africa: Original research. S Afr J Infect Dis. 2009;24:21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blödt S, Holmberg C, Müller-Nordhorn J, Rieckmann N. Human papillomavirus awareness, knowledge and vaccine acceptance: A survey among 18-25 year old male and female vocational school students in Berlin, Germany. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:808–13. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abotchie PN, Shokar NK. Cervical cancer screening among college students in Ghana: Knowledge and health beliefs. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:412–6. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a1d6de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Second edition—Summary document. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:448–58. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker E. Assessing the impact of new cervical cancer screening guidelines. Med Lab Obs. 2013;45:28–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahmani A, Baghianimoghadam MH, Enjezab B, Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Askarshahi M. Factors affecting cervical cancer screening behaviors based on the precaution adoption process model: A qualitative study. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8:211–8. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canavan TP, Doshi NR. Cervical cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis SA, Nelson J, Liverpool J, Soogun S, Mofammere N, Thorpe RJ., Jr Examining attitudes and knowledge about HPV and cervical cancer risk among female clinic attendees in Johannesburg, South Africa. Vaccine. 2010;28:8026–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibekwe CM, Hoque ME, Ntuli-Ngcobo B. Perceived barriers of cervical cancer screening among women attending Mahalapye district hospital, Botswana. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2011;2:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okore O. Africa: University of Limpopo (Medunsa Campus); 2011. The use of health promotion to increase the uptake of cervical cancer screening program in Nyangabgwe Hospital, Botswana [Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saha A, Chaudhury AN, Bhowmik P, Chatterjee R. Awareness of cervical cancer among female students of premier colleges in Kolkata, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1085–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong LP, Wong YL, Low WY, Khoo EM, Shuib R. Knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer and screening among Malaysian women who have never had a Pap smear: A qualitative study. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis MA, Gray RH, Grabowski MK, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, et al. Male circumcision decreases high-risk human papillomavirus viral load in female partners: A randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1247–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]