Abstract

Purpose:

The oral cavity is the most common site for squamous cell carcinoma, which has a distinct predilection for lymphatic spread before distant systemic metastasis. The cervical lymph node status is a very important consideration in the assessment of squamous cell carcinoma. Ultrasound is a noninvasive and inexpensive technique that can be used to differentiate between the benign and metastatic nodes. So the aim of this study was to evaluate reliability of ultrasound for such differentiation and to correlate them with histopathological finding.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 200 lymph nodes from 38 patients histopathologically proven for oral squamous cell carcinoma who underwent surgical neck dissection were considered. The patients underwent ultrasound examination of cervical lymph nodes prior to surgical neck dissection. The lymph nodes were differentiated into benign and metastatic based on the assessment of size, shape, shortest diameter/longest diameter (S/L ratio), margin, and internal architecture, and also the internal echo structure of the lymph nodes and histopathological findings were analyzed.

Results:

On correlation of ultrasonographic diagnosis with histopathological evaluation for metastatic lymph nodes, the overall accuracy of ultrasonographic analyses was 77.83%, and the sonographic criterion of irregular margin showed the highest predictability followed by the size. The correlation of internal echo structure with histopathological findings was highly variable.

Conclusion:

The ultrasound parameters such as size, shape, margin, S/L ratio, and internal echo structure might assist in differentiation between benign and metastatic lymph nodes. Combining these findings should raise the accuracy, as each sonographic parameter has some limitation as a sole criterion.

KEYWORDS: Histopathology, lymph nodes, oral cancer, ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer has a great potential for metastasis to cervical lymph nodes. The status of cervical lymph nodes is the single most important prognostic factor in head and neck cancer. The number of metastatic lymph nodes was found to be an important factor in determining the disease-free interval and overall survival rates. The preoperative assessment of the cervical lymph node status helps in planning suitable surgical management of the neck, wherein the justification to operate the neck is being questioned more often than not, owing to the fact that only about 30% of clinically negative necks are histopathologically positive once operated.

Several radiologic investigative techniques have proven their role in detecting lymph node spread in oral cancer. Modern radiologic imaging has provided the means to maximize the information available to clinicians during treatment planning process.

Ultrasonography (USG) represents a noninvasive, well-tolerated, and inexpensive method in detecting locoregional recurrences. Benign as well as metastatic lymph nodes have typical ultrasonographic characteristics and echogenic criteria that can help in their differentiation. Although ultrasonographic criteria were used in the evaluation of cervical lymphadenopathy, the diagnostic accuracy has not been assessed. So this study evaluated the reliability of ultrasound in differentiation between benign and metastatic lymph nodes and to analyze the ultrasonographic characteristic of cervical lymph nodes in correlation with histopathological findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, 200 lymph nodes of head and neck region were obtained from patients who were hospitalized with oral squamous cell carcinoma and who underwent surgical neck dissection, after informed consent. Among the patients, 20 males and 18 females were included with an average age of 30–79 years (mean age 53.6 years).

Method of collection of data

For each patient, a detailed history was taken including chief complaint, history of presenting illness, medical history, and personal history, and a thorough clinical examination including palpation of cervical lymph nodes was performed bilaterally. The site, size, consistency, and fixity of all the clinically palpable nodes were documented, and a standard pro forma was used to record the clinical signs and symptoms. Patients were then subjected to routine blood investigations after which biopsy was carried out to confirm the diagnosis, and histopathologically proven cases were taken for the study after informed consent.

The patients underwent ultrasound examination of cervical lymph nodes, using GE Voluson 730, 3D, 4D ultrasound machine with 5–10 MHz multifrequency linear probe prior to surgical neck dissection. The neck was hyperextended and turned to the opposite side of examination during scanning to optimally visualize the lymph nodes and examined longitudinally and transversely in a continuous sweep technique covering the neck from level I to level V, the inferior border of the mandible up to the level of the clavicle.

The lymph nodes were assessed ultrasonographically for their size, shape, shortest diameter/longest diameter (S/L ratio), margin, and internal architecture. The longest diameter (L) was defined as the maximum diameter of the longitudinal plane and the shortest diameter (S) was defined as the minimum diameter of the transverse plane. The size was assessed by measuring the shortest diameter. The longest and the shortest diameters were measured and S/L ratio was calculated. The margin was also assessed and lymph nodes were separated into regular and irregular margin. The internal echo structure was divided into five patterns, which had to be correlated with the histopathological findings.

A total of 42 neck dissections were performed, among which radical neck dissection was performed in 17 patients, supraomohyoid neck dissection was performed in 21 patients, and bilateral supraomohyoid neck dissection was performed in 4 patients. The resected neck specimens were oriented anatomically and markings for each lymph node level were carried out. Those lymph nodes that were evaluated by ultrasound based on their size and location were separated into benign, and metastatic and also the internal echo structure of the lymph nodes and histopathological findings were analyzed. The presence of metastatic lymph nodes in any lymph node level was considered as the positive criteria for diagnosing the neck as positive for metastasis. Histopathology was considered as the gold standard in evaluating the neck for metastasis. The results of ultrasonographic evaluation were correlated with histopathological finding.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistical analysis has been carried out. Confidence intervals (90%) were computed. Chi-square test has been used to find the significance of data to analyze cervical lymph node metastasis. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy were computed to find the diagnostic performance of USG as against the histopathological findings for metastasis.

RESULTS

This study was undertaken to study the efficacy of ultrasound in differentiating between benign and metastatic lymph nodes and to correlate the internal echo structure with histopathological findings.

This study included 200 lymph nodes from 38 patients with histopathologically proven oral squamous cell carcinoma who underwent surgical neck dissection. Correlation of stage of tumor with lymph node metastasis in all the five levels of cervical lymph node revealed that level 5 involvement was seen even in stage II and III tumors but stage IV tumors with no level 5 nodal metastasis, thus showing that stage of tumor had less predictability to assess the prevalence of nodal metastasis.

Results of ultrasonographic evaluation of lymph nodes

Correlation of ultrasonographic diagnosis with histopathological evaluation for metastatic lymph nodes includes true positive value of 61 (30.5%), false positive value of 23 (11.5%), false negative value of 21 (10.5%), true negative value of 95 (47.5%) with a sensitivity of 73.81% and a specificity of 80.67%, and the overall accuracy of ultrasonographic analyses of 77.83%.

Results of efficacy of five different ultrasonographic parameters as a better predictor for evaluation of lymph node metastasis

Shape

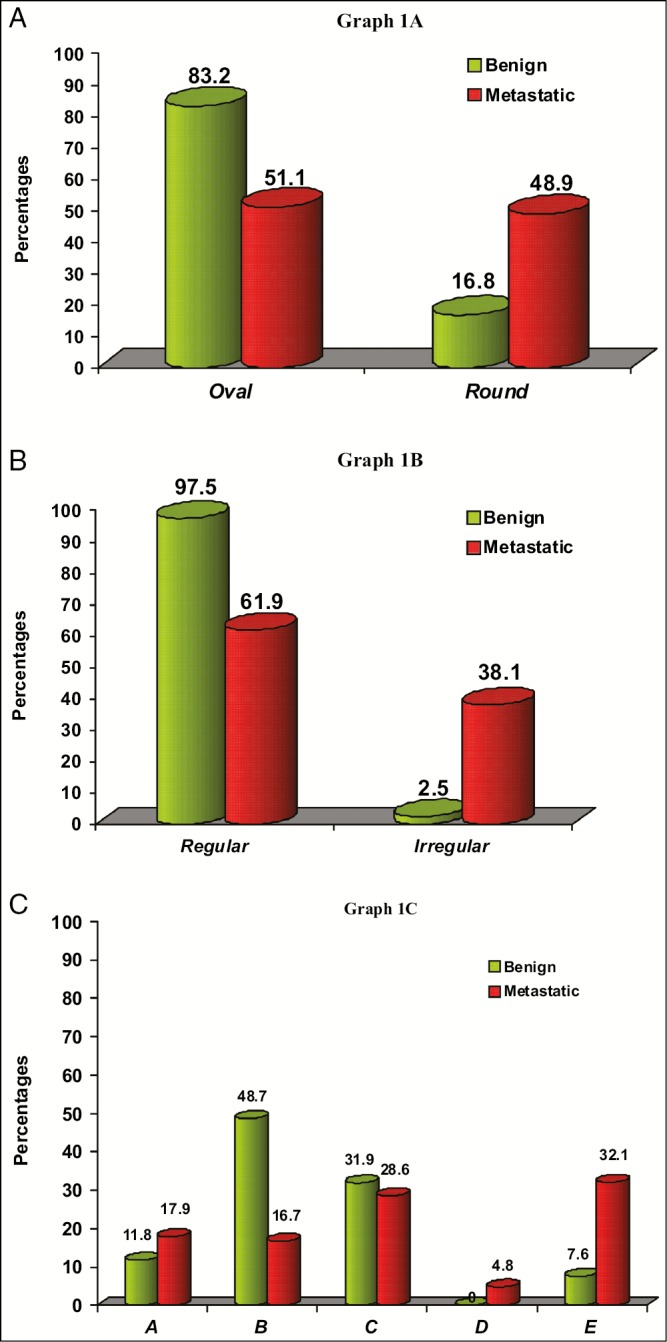

The shape of the lymph nodes as analyzed by ultrasound included 139 (69.5%) lymph nodes with oval shape and 61 (30.5%) lymph nodes with round shape. In 83.2% of benign lymph nodes, the shape was oval and in 48.9% of metastatic lymph nodes the shape was round [Table 1; Graph 1 A].

Table 1.

Association of ultrasonographic parameters with histopathologic results of lymph node metastasis

| Lymph node analysis | Benign (n = 118) | Metastatic (n = 82) | P value | OR | 90% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Shape | |||||||

| Oval | 98 | 83.2 | 43 | 52.5 | <0.001** | 0.21 | 0.12–0.36 |

| Round | 20 | 16.8 | 39 | 47.5 | <0.001** | 4.71 | 2.75–8.09 |

| Margin | |||||||

| Regular | 115 | 97.5 | 51 | 62.2 | <0.001** | 0.04 | 0.02–0.12 |

| Irregular | 3 | 2.5 | 31 | 37.8 | <0.001** | 23.79 | 8.49–66.68 |

| Echo structure | |||||||

| Homogenous hyper echoic | 14 | 11.8 | 15 | 17.9 | 0.222 | 1.63 | 0.84–3.16 |

| Homogenous hypo echoic | 58 | 48.7 | 14 | 16.7 | <0.001** | 0.21 | 0.12–0.37 |

| Eccentric hyper echoic | 38 | 31.9 | 24 | 28.6 | 0.609 | 0.86 | 0.51–1.43 |

| Centric hyper echoic | 0 | — | 3 | 4.8 | 0.028* | — | — |

| Heterogeneous | 8 | 7.6 | 26 | 32.1 | <0.001** | 5.78 | 2.91–11.51 |

| Size | |||||||

| <1 | 74 | 63.1 | 14 | 19.1 | <0.001** | 0.14 | 0.08–0.24 |

| ≥1 | 44 | 36.9 | 68 | 80.9 | <0.001** | 7.24 | 4.16–12.60 |

| S/L ratio | |||||||

| <0.67 | 77 | 64.7 | 18 | 21.4 | <0.001** | 0.15 | 0.08–0.27 |

| ≥0.67 | 41 | 35.3 | 64 | 78.6 | <0.001** | 6.72 | 3.92–11.52 |

CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation, No. = number

P value <= 0.01

Graph 1.

Comparison of shape in benign and metastatic lymph node (A), comparison of margin in benign and metastatic lymph node (B), and comparison of internal echo structure in benign and metastatic lymph node (C). A = homogenous hyperechoic, B = homogenous hypoechoic, C = eccentric hyperechoic, D = centric hyper echoic E = heterogeneous pattern

Margin

The margin of the lymph nodes varied between 166 (83%) with regular margins and 34 (17%) with irregular margin. Of 118 benign lymph nodes, 115 (97.5) were having regular margins, and out of 82 metastatic lymph nodes, 31 (38.1%) were with irregular margin [Table 1; Graph 1 B].

Size

The size of the lymph nodes varied between 3 groups with 22 lymph nodes (11%) up to 0.75 cm, 87 (43.5%) lymph nodes between 0.75 and 1 cm, and 91 (45.8%) lymph nodes slightly greater than 1 cm with mean size of 1.03 cm.

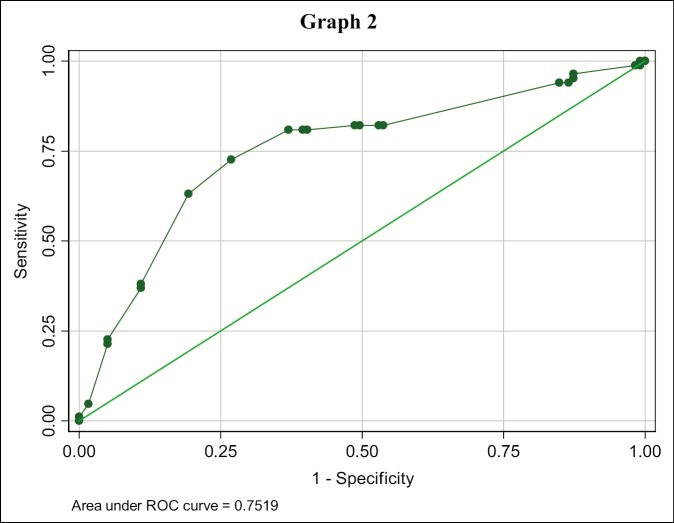

Of 88 lymph nodes with size <1 cm, 74 (84%) were benign and 68 (60.7%) out of 112 lymph nodes with size greater than or equal to 1 cm were metastatic [Table 1]. Further the, predictability of size was analyzed with receiving operating characteristic (ROC) curve that established a cutoff value for size for benign and metastatic lymph node, which was found to be greater than or equal to 1 cm with 80.95% sensitivity and 63.03% specificity, and an accuracy of 70.44% [Table 2; Graph 2].

Table 2.

Evaluation of lymph node size for metastasis

| Size | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >= 0.1 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 41.38 | 1 | |

| >= 0.65 | 100.00 | 0.84 | 41.87 | 1.0085 | 0 |

| >= 0.67 | 98.81 | 0.84 | 41.38 | 0.9965 | 1.4167 |

| >= 0.7 | 98.81 | 1.68 | 41.87 | 1.005 | 0.7083 |

| >= 0.71 | 96.43 | 12.61 | 47.29 | 1.1034 | 0.2833 |

| >= 0.73 | 95.24 | 12.61 | 46.80 | 1.0897 | 0.3778 |

| >= 0.75 | 94.05 | 13.45 | 46.80 | 1.0866 | 0.4427 |

| >= 0.85 | 82.14 | 47.06 | 61.58 | 1.5516 | 0.3795 |

| >= 0.88 | 82.14 | 50.42 | 63.55 | 1.6568 | 0.3542 |

| >= 0.9 | 82.14 | 51.26 | 64.04 | 1.6853 | 0.3484 |

| >= 0.93 | 80.95 | 59.66 | 68.47 | 2.0069 | 0.3192 |

| >= 0.96 | 80.95 | 60.50 | 68.97 | 2.0496 | 0.3148 |

| >= 1 | 80.95 | 63.03 | 70.44 | 2.1894 | 0.3022 |

| >= 1.1 | 72.62 | 73.11 | 72.91 | 2.7005 | 0.3745 |

| >= 1.2 | 63.10 | 80.67 | 73.40 | 3.2645 | 0.4575 |

| >= 1.4 | 21.43 | 94.96 | 64.53 | 4.25 | 0.8274 |

| >= 1.5 | 4.76 | 98.32 | 59.61 | 2.8333 | 0.9687 |

| >= 1.7 | 1.19 | 100.00 | 59.11 | 0.9881 | |

| > 1.7 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 58.62 | 1 | |

| Area under curve | 0.7519; 95% CI (0.68–0.82) | ||||

CI = confidence interval, LR = likelihood ratio

Graph 2.

Receiving operating characteristics (ROC-curve) of lymph node size for diagnosing metastasis. Each point on the ROC curve represents a sensitivity specificity pair corresponding to a decision threshold. A test with perfect discrimination (no overlap in two distributions) has a ROC curve that passes through upper left corner and corresponds with bold values for Size (Table 1).

S/L ratio

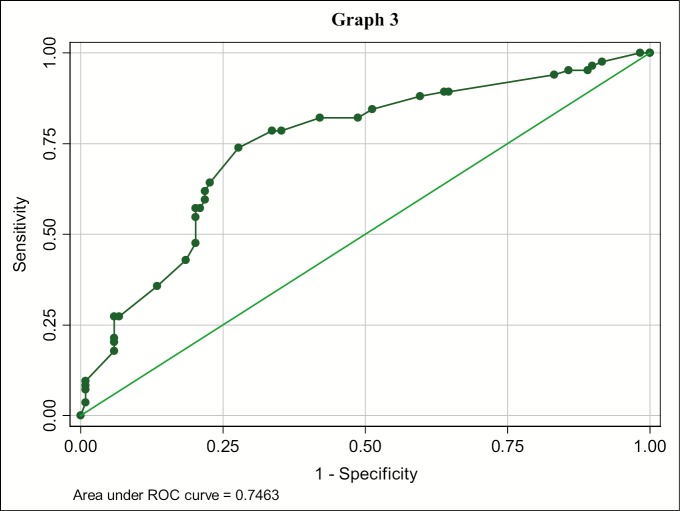

Of 95 lymph nodes with S/L ratio less than 0.67, 77 (81%) were benign and 64 (61%) out of 105 lymph nodes with ratio greater than or equal to 0.67 were metastatic [Table 1]. Further the predictability of S/L ratio was analyzed with ROC curve that established a cutoff value for benign and metastatic lymph node, which was found to be greater than or equal to 0.67 with 78.57% sensitivity and 64.71% specificity, and an accuracy of 70.44% [Table 3; Graph 3].

Table 3.

Evaluation of S/L ratio of lymph node for metastasis

| SL ratio | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >= 0.56 | 95.24 | 10.92 | 45.81 | 1.0692 | 0.4359 |

| >= 0.58 | 95.24 | 14.29 | 47.78 | 1.1111 | 0.3333 |

| >= 0.6 | 94.05 | 16.81 | 48.77 | 1.1305 | 0.3542 |

| >= 0.61 | 89.29 | 35.29 | 57.64 | 1.3799 | 0.3036 |

| >= 0.62 | 89.29 | 36.13 | 58.13 | 1.398 | 0.2965 |

| >= 0.64 | 84.52 | 48.74 | 63.55 | 1.6489 | 0.3175 |

| >= 0.65 | 82.14 | 51.26 | 64.04 | 1.6853 | 0.3484 |

| >= 0.66 | 82.14 | 57.98 | 67.98 | 1.955 | 0.308 |

| >= 0.67 | 78.57 | 64.71 | 70.44 | 2.2262 | 0.3312 |

| >= 0.68 | 78.57 | 66.39 | 71.43 | 2.3375 | 0.3228 |

| >= 0.7 | 73.81 | 72.27 | 72.91 | 2.6616 | 0.3624 |

| >= 0.71 | 64.29 | 77.31 | 71.92 | 2.8333 | 0.462 |

| >= 0.73 | 59.52 | 78.15 | 70.44 | 2.7244 | 0.5179 |

| >= 0.74 | 57.14 | 78.99 | 69.95 | 2.72 | 0.5426 |

| >= 0.76 | 54.76 | 79.83 | 69.46 | 2.7153 | 0.5667 |

| >= 0.77 | 47.62 | 79.83 | 66.50 | 2.3611 | 0.6561 |

| >= 0.78 | 42.86 | 81.51 | 65.52 | 2.3182 | 0.701 |

| >= 0.8 | 35.71 | 86.55 | 65.52 | 2.6563 | 0.7427 |

| >= 0.81 | 27.38 | 93.28 | 66.01 | 4.0729 | 0.7785 |

| Area under curve | 0.7463; 95% CI (0.67–0.81) | ||||

CI = confidence interval

Graph 3.

Receiving operating characteristics (ROC-curve) of lymph node S/L ratio for diagnosing metastasis. Each point on the ROC curve represents a sensitivity specificity pair corresponding to a decision threshold. A test with perfect discrimination (no overlap in two distributions) has a ROC curve that passes through upper left corner and corresponds with bold values for S/L ratio (Table 2).

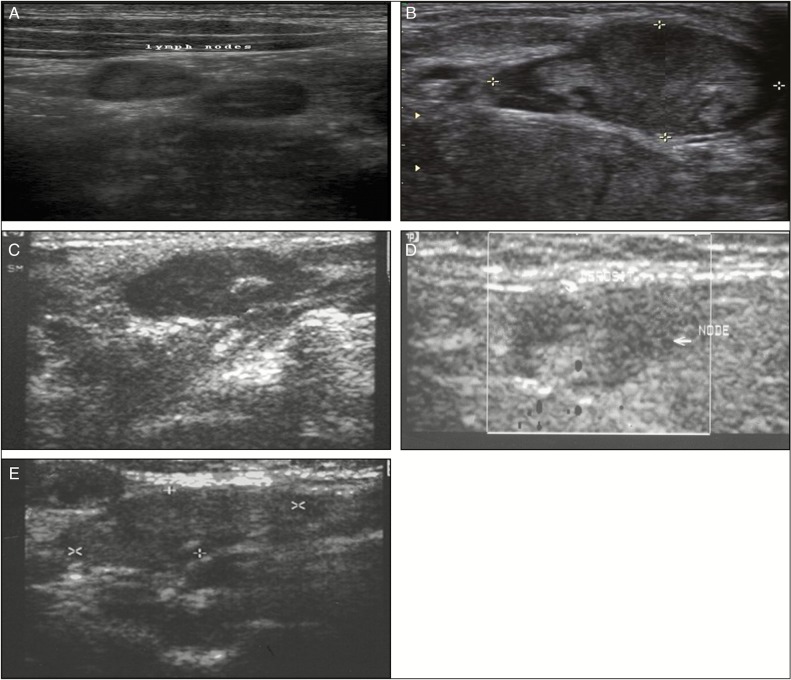

Fourteen (51.7%) out of 29 lymph nodes with homogenous hyperechoic pattern and 58 (80.5%) out of 72 lymph nodes with homogenous hypoechoic pattern were benign. All the 3 lymph nodes with centric hyperechoic pattern and 26 (75%) out of 34 lymph nodes with heterogeneous pattern were metastatic and 38 (61.2%) out of 62 lymph nodes with eccentric hyperechoic pattern were benign. The differences between benign and metastatic lymph nodes regarding the distribution of three internal echo patterns of homogenous hypoechoic, centric hyperechoic pattern, heterogeneous pattern were statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 1; Graph 1C].

Results of correlation of internal echo structure with histopathological findings

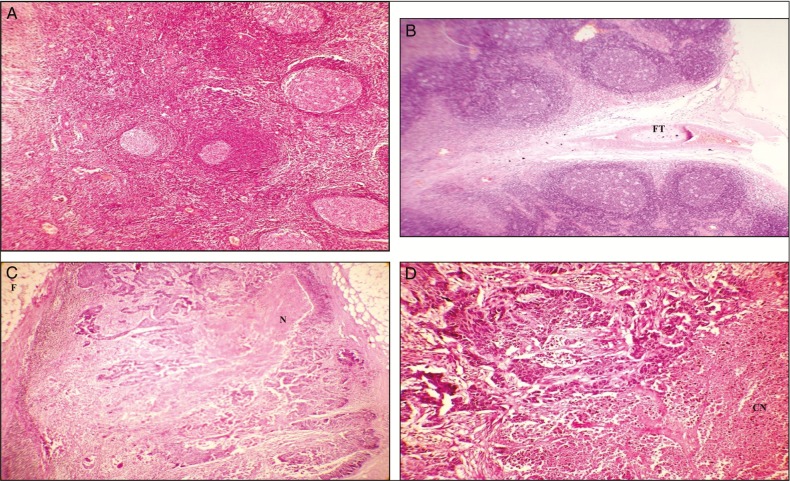

Among the 58 benign lymph nodes with homogenous hypoechoic pattern [Figure 1A], the hypoechoic areas were normal lymphatic tissue [Figure 2A], and in 14 lymph nodes that were metastatic, the normal architecture was destroyed with small metastatic foci or mild fibrosis was found [Figure 2C]. In all the 3 lymph nodes with centric hyperechoic [Figure 1C] pattern, the hyperechoic area was of coagulation necrosis [Figure 2D].

Figure 1.

Ultrasonograph showing homogenous hypoechoic pattern (A), heterogeneous pattern (B), centric hyperechoic pattern (C), homogenous hyperechoic pattern (D), and eccentric hyperechoic pattern (E)

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing normal lymphatic tissue seen as the hypoechoic areas in benign nodes (A), photomicrograph showing central hilus with surrounding fatty tissue (FT) seen as the hyperechoiec areas in benign nodes. (B), areas of necrosis (N) or fibrosis (F) seen as hyperechoic areas of metastatic nodes (C), and area of coagulation necrosis (CN) seen in hyperechoic areas of metastatic node (D)

The heterogeneous pattern [Figure 1B] was a mixture of necrosis and fibrosis [Figure 2C]. The hyperechoic areas of eccentric hyperechoic [Figure 1E] and homogenous hyperechoic pattern [Figure 1D] were either necrosis or fibrosis [Figure 2C], and in benign lymph nodes, they corresponded to hilus and surrounding fatty tissue [Figure 2B]. Thus histopathological pattern of corresponding internal echo structure was highly variable, and the small metastatic foci and mild fibrosis cannot be distinguished from normal lymphatic tissue in the echo pattern and hence the histopathological correlation was not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The presence of cervical metastatic nodal disease is a major prognostic determinant for patients with oral cavity cancer, significantly reducing patient survival. Ultrasound, with its multidirectional scanning options, seems to be an ideal complementary examination technique for the neck. Enlarged cervical lymph nodes can be recognized sonographically and differentiated from other structures. The pathologic lymph nodes are mostly larger than 5 mm in both malignant and benign inflammatory diseases.[1] Ultrasound criteria to characterize a lesion as malignant based on size and differentiation between malignant and benign inflammatory conditions are impossible. This study established a cutoff value of 1 cm for metastatic nodes and was used along with other parameters to establish metastatic cervical lymph nodes.

Small nodes, up to 10 mm in diameter, are encountered in most normal subjects, especially in the submandibular, internal jugular, and spinal accessory chains. Size criteria cannot be relied on solely for distinguishing nonmalignant nodes, because some small nodes (<1 cm) harbor metastatic disease whereas some nodes in excess of 1.5 cm in diameter are histologically benign. Thus, an appropriate radiologic criteria has to be established.[2] This study analyzed size, S/L ratio, margin, and internal echo structure, which showed a sensitivity of 73.8% and an accuracy of 77.83%.

In the study done to assess the accuracy of radiologic criteria to assess metastatic lymph nodes the nodes with a minimal axial diameter larger than 12 mm were metastatic and is most effective size criterion. Although metastatic lymph nodes with a minimal axial diameter smaller than 10 mm made up 58% of all malignant nodes. In this respect, the use of the maximal axial diameter (3–43 mm) was not significantly more accurate. At a maximal axial diameter of 14–15 mm, which is often used as a size criterion, only 45% of the nodes contained tumor. In this study, the minimal axial diameter of metastatic lymph node was found to be greater than or equal to 1 cm with 80.95% sensitivity and 63.03% specificity and an accuracy of 70.44%.[3]

In a study the internal echo pattern and homogeneity were compared between metastatic and reactively enlarged nodes. Although large metastatic nodes often exhibited heterogeneous pattern due to necrotic tumor, lymphatic tissue, solid tumor, fat, or keratinizing tumor, these heterogeneous ultrasonographic patterns were less frequently encountered in small nonpalpable lymph nodes and areas of hyperechogenicity could represent fatty tissue or keratinizing tumor[4]; thus, the internal echo structure was nonspecific in prediction of metastasis

The short axis diameter in the our study was 10 mm with a sensitivity of 80.95%, and an S/L ratio of 0.67 will thus be a better predictor of cervical lymph node metastasis also as stated in another study,[5,6] which stated S/L ratio of ≥ 0.5 to be reliable criterion.

The hyperechoic areas corresponded to coagulation necrosis in metastatic nodes whereas it was attributed to fatty tissue around hilus or fibrosis in benign ones. Further in metastatic nodes showing hypoechoic pattern, the normal lymph node architecture was destroyed with small metastatic foci or fibrosis.[7,8] So internal echo structure could not specifically distinguish benign and metastatic lymph nodes in correlation to this study.

In this study, the sonographic criterion of irregular margin was highly statistically significant and that established a cutoff value for metastatic lymph node, which was found to be ≥0.67 with 78.57% sensitivity and 64.71% specificity and an accuracy of 70.44%. The irregular margin in the metastatic node may be attributed to extra nodular infiltration, and small metastasis may not influence a nodal margin.[8] The differences in the specificity and a selected sonographic criterion between the series and our study were probably caused by difference in the patient populations.[9]

A study was performed to establish sonographic criteria for distinguishing normal from abnormal lymph nodes, which included size, shape, echogenic hilus, nodal border, and distribution, and reliability of these criteria has been assessed. In the assessment of the cervical lymph nodes, the short axis was more accurate (91%) for the parotid nodes; the nodal shape was more reliable (82%) when the upper cervical nodes were assessed.[10,11]

Although various parameters have been valuable in predicting the possibility of metastatic nodes, no single parameter has shown a clear cutoff point in differentiating metastasis in lymph nodes as each parameter has some limitation as a sole criterion, so diagnostic criteria composed of various combinations of several parameters have been proposed but most of it shows low diagnostic accuracy because of the overlap in the sonographic findings.[12] Various studies suggest that sonographic findings of metastasis, such as a change in lymph node size or internal echogenicity, may change relatively quickly, even within a 2- to 4-week period. Sonography is especially useful for monitoring the status of early detection of cervical lymph nodes within a short interval of post therapeutic follow-up to ensure that additional therapy is not delayed.[13]

In a study to evaluate ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) in detecting lymph nodes in the neck in oral squamous cell carcinoma, for all levels ultrasound yielded a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 87%, whereas CT showed a sensitivity of 32% and a specificity of 96%. The sensitivity of ultrasound decreased from level I to IV, whereas the specificity increased from level I to level IV. The false negative results in ultrasound may be lymph node metastases less than 10 mm or might be due to fusion of several small affected lymph nodes and due to low resolution USG of 7.5 MHz.[14]

However, evaluation of submandibular nodes by ultrasound is fraught with difficulties, and the low sensitivity may be due to various reasons. There is a technical difficulty in ultrasound assessment of the submandibular nodes because some of the nodes are situated in the submandibular niche and are hidden by the body of mandible. These nodes cannot be adequately evaluated by ultrasound. It is generally agreed that different imaging modalities, including ultrasound, have limited value in the detection of micrometastases because the first evidence of metastatic infiltrates in lymph nodes may be minimal without change in size, macroscopic morphology, or consistency of the node.[15]

Several studies have shown that ultrasound and US-guided fine-needle aspiration are similar or superior to magnetic resonance imaging or CT for the detection of malignant nodes. Further research in the area for better information about the use of three-dimensional ultrasound in the assessment of cervical lymph nodes, which is more accurate than three-dimensional ultrasound in volumetric measurements, is to be considered.[16,17]

CONCLUSION

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity is a challenging entity to the oral and maxillofacial surgeon and represents a public health problem of enormous dimension. For determining the right strategy toward treatment, a thorough assessment of the tumor as well as regional and distant spread is essential to obtain optimum results. This study is based on the efficacy of ultrasound as an investigative modality to assess the regional lymph node metastasis with regard to oral squamous cell carcinoma and to correlate the internal echo structure with histopathological findings.

In this study, the sonographic criterion of irregular margin showed the highest predictability followed by the size for which the cutoff value was established for metastatic lymph node, which was found to be ≥ 1 cm. The S/L ratio that established a cutoff value for metastatic lymph node, which was found to be ≥ 0.67, is the next better predictor followed by heterogeneous internal echo structure and the round shape of the metastatic lymph node. The accuracy of imaging techniques is, to a far extent, determined by the criteria used for detecting lymph node metastases; hence, it was concluded that combining the ultrasonographic parameters should raise the accuracy. In general, none of the currently available imaging techniques are able to depict micrometastasis and histopathological examination remains the gold standard. There is always a need for further refinement of the imaging techniques and criteria that can provide accurate information that approaches this gold standard.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hajek P, Salomonowitz E, Turk R, Tscholakoff D, Kumpan W, Czembirek H. Lymph nodes of the neck: Evaluation with US. Radiology. 1986;158:739–42. doi: 10.1148/radiology.158.3.3511503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jhonson JT. A surgeon looks at cervical lymph nodes. Radiology. 1990;175:607–10. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.3.2188292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Den Brekel MWM, Stel HV, Castelinjns JS, Nauta JJ, Vander Waal I, Valk J, et al. Cervical lymph node metastasis: Assessment of radiologic criteria. Radiology. 1990;177:379–84. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.2.2217772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Den Brekel MW, Stel HV, Castelinjns JS, Luth WJ, Valk J, van der Waal I. Occult metastatic neck disease: Detection with US and US-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology. Radiology. 1991;180:457–61. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.2.2068312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinkamp HJ, Cornehl M, Hosten N, Pegios W, Vogl T, Felix R. Cervical lymphadenopathy: Ratio of long- to short axis diameter as a predictor of malignancy. Br J Radiol. 1995;68:807. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-68-807-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahuja A, Ying M, Yang WT, Evans R, King W, Metreweli C. The use of sonography in differentiating cervical lymphomatous lymph nodes from cervical metastatic lymph nodes. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:186–90. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(96)80321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim SC, Zhang S, Ishii G, Endoh Y, Kodama K, Miyamoto S, et al. Predictive markers for late cervical metastasis in Stage I and II Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:166–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0533-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toriyabe Y, Nishimura T, Kita S, Saito Y, Miyokawa N. Differentiation between benign and metastatic cervical lymph nodes with ultrasound. Radiology. 1997;52:927–32. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(97)80226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takashima S, Sone S, Nomura N, Tomiyama N, Kobayashi T, Nakamura H. Nonpalpable lymph nodes of the neck: Assessment with US and US-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25:283–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199707)25:6<283::aid-jcu1>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Den Berkel MW, Castelijns JA, Snow GB. The size of lymph nodes in the neck on sonograms as a radiologic criterion for metastasis: How reliable is it? ANJR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:695–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ying M, Ahuja A, Metreweli C. Diagnostic accuracy of sonographic criteria for evaluation of cervical lymphadenopathy. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:437–45. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.7.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yusa H, Yoshida H, Ueno E. Ultrasonographic criteria for diagnosis of cervical lymph node metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma in the oral and maxillofacial region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:41–8. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuasa K, Kawazu T, Kunitake N. Sonography for the detection of cervical lymph node metastases among patients with tongue cancer: Criteria for early detection and assessment of the follow-up examination intervals. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1127–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuasa K, Kawazu T, Nagata T, Kanda S, Ohishi M, Shirasuna K. Computed tomography and ultrasonography of metastatic cervical lymph nodes in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2000;29:238–44. doi: 10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.To EW, Tsang WM, Cheng J, Lai E, Pang P, Ahuja AT, et al. Is neck ultrasound necessary for early stage oral tongue carcinoma with clinically N0 neck? Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2003;32:156–9. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/20155904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King AD, Gary MK, Ahuja AT, Yuen EH, Vlantis AC, To EW, et al. Necrosis in metastatic neck nodes: Diagnostic accuracy of CT, MR imaging and US. Radiology. 2004;230:720–26. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303030157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ying M, Ahuja AT. Ultrasound of neck lymph nodes: How to do it and how do they look? Radiology. 2006;12:105–17. [Google Scholar]