Abstract

Aim:

This study evaluated the relationship between missing posterior teeth and body mass index with regard to age and socioeconomic state in a sample of the suburban south Indian population.

Materials and Methods:

The 500 individuals of both males and females aged 40 years and older with missing posterior teeth and not rehabilitated with any prosthesis were gone through a clinical history, intraoral examination, and anthropometric measurement to get information regarding age, sex, socioeconomic status, missing posterior teeth, and body mass index (BMI). Subjects were divided into five groups according to BMI (underweight > 18.5 kg/m2, normal weight 18.5–23 kg/m2, overweight 23–25 kg/m2, obese without surgery 25–32.5 kg/m2, obese with surgery < 32.5 kg/m2). Multivariate logistic regression was used to adjust data according to age, sex, number of missing posterior teeth, and socioeconomic status.

Results:

People with a higher number of tooth loss were more obese. Females with high tooth loss were found to be more obese than male. Low socioeconomic group obese female had significantly higher tooth loss than any other group. No significant relation between age and obesity was found with regard to tooth loss.

Conclusion:

The BMI and tooth loss are interrelated. Management of obesity and tooth loss can help to maintain the overall health status.

KEYWORDS: Body mass index, obesity, oral health, socioeconomic status, tooth loss

INTRODUCTION

The loss of teeth causes a considerable impact on mastication, digestion, phonation, and aesthetics.[1] The functional impairment depends on the location, distribution, and extension of the tooth loss, which might ultimately affect the quality of life.[2] Individuals having less number of teeth adapt to softer and processed food more than fibrous food such as fruits, raw vegetables, meat, and dry foods.[3,4] The processed and softer food has a fairly high quantity of fat and cholesterol, and lacks in vitamins and minerals, which can lead to chronic illnesses such as stroke, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and physical disability.[4] Chauncey et al.[5] in their study concluded that “shifts in food selection patterns result from impairments in masticatory ability due to edentulism and appears to be dependent on the degree of impairment.”

The earlier studies showed an association between edentulousness and chewing problems to malnutrition in independent living, hospitalized, and institutionalized older people.[6,7,8,9] Studies also showed that the presence of 20 or more teeth increases the chance of having an adequate body mass index (BMI) among independent living elderly people.[7,10] However, these studies were carried out mainly in populations from well-developed countries, where the tooth loss is more frequently rehabilitated with dental prostheses. There is limited information in the literature on South Asian population like India where experiencing significant tooth losses were not replaced by dental prostheses due to various reasons and with the greater chance for obesity, underweight, or malnutrition. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether tooth loss is a potential contributor to changes in BMI or vice versa in south Indian suburban individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was a randomized cross-sectional study for evaluating the association between oral health and obesity (BMI). The sample was composed of 500 free-living individuals including both males and females aged 40 years and older. The selection criteria include the persons should not have any acute infection recently (not less than 6-month period) or any chronic systemic illness such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and tumors. The period of edentulousness should not be less than 6 months and the person should have at least one missing posterior occluding unit and without any prosthesis replacement. The physically and mentally challenged individuals were excluded. The ethical clearance for the study was obtained and informed consent was taken from all the participants before starting the study. All the subjects underwent a recording of clinical history, oral clinical examination, and anthropometric measurement. Clinical history: The age, gender, socioeconomic status, marital status, and smoking status of the individuals were recorded. Oral clinical examination: The subjects were seated in a dental chair and oral examination was performed with help of two trained dental surgeons. The number of missing teeth and posterior missing occluding unit in all the four quadrants of the maxillary and mandibular arch were assessed and noted. Anthropometric measurements: Height and weight of each subject were measured. Height was measured with the help of wall-mountable Bio Plus Stature Meter (Bharat Enterprises [Bio Plus], Delhi, India) and weight was measured using platform weighing scale (Sansui Electronics, Pune, India). After recording the weight and height of each subject, BMI was calculated using the metric-imperial formula BMI (kg/m2) = weight in kilograms/(height in meters)2. Subjects were divided into five groups according to BMI cutoffs set by Health Ministry of India in 2008 in the consensus guidelines for prevention and management of obesity and metabolic syndrome for the country (underweight >18.5 kg/m2, normal weight 18.5–23 kg/m2, overweight 23-25 kg/m2, obese without surgery 25–32.5 kg/m2, obese with surgery <32.5 kg/m2).[11,12] Data were adjusted according to age (<50 years, 50–60 years, 61–70 years, >70 years), sex, missing posterior teeth (low <4 teeth, medium 5–10 teeth, high >10 teeth), and socioeconomic status. Multivariable analysis was performed using logistic regression.

RESULTS

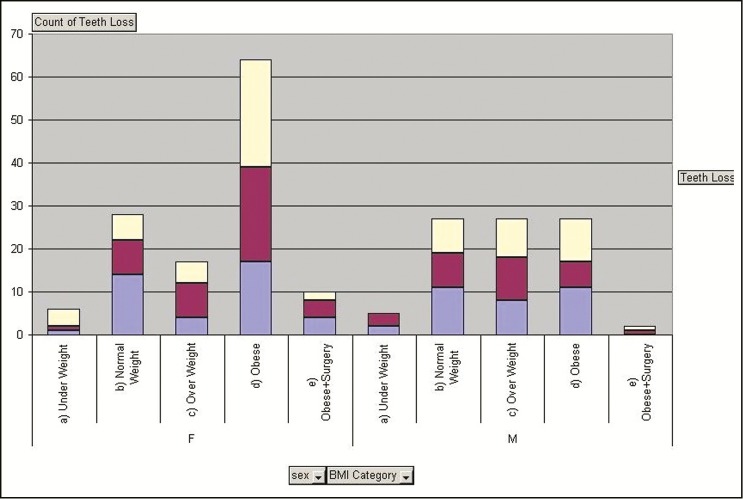

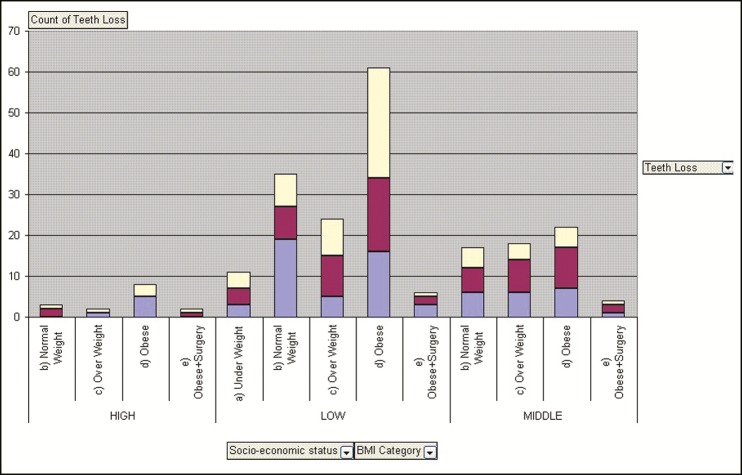

Of 500 individuals, 260 were females and 240 were males. Obesity was found to be increased in people with a higher number of teeth loss (>10). Of the 500 total subjects, 32.8% had a higher number of tooth loss and 50% of that were obese. Overall data show the prevalence of higher tooth loss was 31.8% in male and 33.6% female and the prevalence of obesity was 51.2% in females and 30.6% in male, which is a significant difference [Table 1]. Females with high tooth loss group were found to be more obese than their male counterpart. Of the females, 59.5% were obese with high tooth loss as compared to 35.7% males [Figure 1]. Of the females with obesity, 70% belonged to a low socioeconomic group, which is significantly higher than any other group [Figure 2]. There was no significant relationship between age groups and obesity with regard to tooth loss.

Table 1.

Demographic data presenting male and female subjects according to body mass index (BMI) and number of tooth loss

| Sex | BMI category | Posterior tooth loss | Grand total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |||

| Female | (a) Under weight | 7 | 4 | 2 | 13 |

| (b) Normal weight | 29 | 20 | 9 | 58 | |

| (c) Over weight | 7 | 15 | 13 | 35 | |

| (d) Obese | 35 | 46 | 52 | 133 | |

| (e) Obese + surgery | 5 | 5 | 11 | 21 | |

| Total | 83 | 90 | 87 | 260 | |

| Male | (a) Under weight | 5 | 8 | 0 | 13 |

| (b) Normal weight | 30 | 22 | 22 | 74 | |

| (c) Over weight | 22 | 27 | 25 | 74 | |

| (d) Obese | 30 | 16 | 27 | 73 | |

| (e) Obese + surgery | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Total | 87 | 76 | 77 | 240 | |

| Grand total | 170 | 166 | 164 | 500 | |

Figure 1.

A bar graph showing the relationship between tooth loss and body mass index with regard to sex

Figure 2.

A bar graph showing the relationship between tooth loss and body mass index with regard to socioeconomic status

DISCUSSION

Obesity or overweight is a cause for a number of disorders including life-threatening ones as found in the literature.[13,14] The risk stratification is based on the Quetelet’s Index (or BMI), which is commonly a surrogate measure of fatness.[15] In Indian population, the diagnostic cutoff for BMI is lowered to 23 kg/m2 as opposed to 25 kg/m2 globally because studies have shown that Indian body composition and genetics are different from their western counterparts and are more prone for abdominal obesity.[11,12] The results of this cross-sectional study suggest that a poor oral status represented by partial or complete tooth loss is associated with obesity in independent living persons from the suburban south India. In this study, 59.5% of females had high tooth loss and were found to be obese whereas only 35.7% of males were obese with high tooth loss. This shows a significant number of female populations in suburban India are obese, which agrees with the previous reports.[11] It is seen in recent studies that females are more prone to high tooth loss than males.[16] Overall data suggested obesity was associated with higher number of tooth loss. Marcenes et al.[10] found that the people with less than 20 teeth were at a risk to be obese three times greater than the ones with 31–32 teeth.

There is no known mechanism that explains the exact relationship between obesity, tooth loss, and gender differences related to these factors. It has been speculated that these changes are mediated by eating behavior of the individual.[17] An impaired dental status can lead to altered food patterns.[18,19] Edentulism has been shown to increase the chance for both underweight as well as obesity depending on the population characteristics.[20] A few studies have been carried out in a population experiencing extensive tooth loss whether the oral health status was associated with body composition.

Several studies have shown that dental caries and periodontal diseases are the main causative factors for tooth loss.[21,22] Recent research by Forsyth Institute found a link between the obesity and a particular periodontal-disease-causing bacterium named Tannerella forsythia, which is found in the oral flora in an otherwise healthy mouth.[23] The 40 bacterial species were studied and the only species found in different proportion in obese individuals than others was T. forsythia. This may suggest that the metabolic changes that occur due to obesity might change the microbial colonization patterns altering the progression the periodontal diseases leading to tooth loss.[24] A study by Chitsazi et al. showed that obesity, weight circumference, and overweight are also associated with C-reactive protein (CRP) in both male and female gender but it is more prominent in females.[25] It is well-known that CRP is an acute phase inflammatory mediator produced by liver.[26] It is also elevated in periodontitis caused by gram-negative pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and T. forsythia.[23,27,28] This suggests that in obese females, the risk of periodontitis is higher than male leading to more tooth loss. But all the local factors also have to be taken into consideration.

The findings suggest that individuals living partially edentulous without any replacement with the prosthesis are at risk for both malnutrition as well as obesity. Obesity and tooth loss seem to be interrelated in a more complex way. The effects of the oral health status on body composition indicate the maintenance of a healthy and functional dentition into old age may have an important additional effect in maintaining a healthy BMI. The limitations of this study are self-reported measures of the medical diseases and no assessment of physical activity, food preferences of the individuals, and level of education was performed. A case–control study with more samples may give us better conclusive evidence.

CONCLUSION

The BMI and tooth loss are interrelated. Compared to males, females with high tooth loss are found to be more obese. Females belonging to a low socioeconomic group and having high tooth loss are more obese, which is significantly higher than any other group. There is no significant relationship between age groups and obesity with regard to tooth loss.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liedberg B, Norlén P, Owall B. Teeth, tooth spaces, and prosthetic appliances in elderly men in Malmö, Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:164–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:126. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kagawa R, Ikebe K, Inomata C, Okada T, Takeshita H, Kurushima Y, et al. Effect of dental status and masticatory ability on decreased frequency of fruit and vegetable intake in elderly Japanese subjects. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:368–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.N’gom PI, Woda A. Influence of impaired mastication on nutrition. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:667–73. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.123229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chauncey HH, Muench ME, Kapur KK, Wayler AH. The effect of the loss of teeth on diet and nutrition. Int Dent J. 1984;34:98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikebe K, Matsuda K, Morii K, Furuya-Yoshinaka M, Nokubi T, Renner RP. Association of masticatory performance with age, posterior occlusal contacts, occlusal force, and salivary flow in older adults. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:475–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheiham A, Steele JG, Marcenes W, Finch S, Walls AW. The relationship between oral health status and body mass index among older people: A national survey of older people in Great Britain. Br Dent J. 2002;192:703–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahyoun NR, Lin CL, Krall E. Nutritional status of the older adult is associated with dentition status. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:61–6. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dormenval V, Mojon P, Budtz-Jørgensen E. Associations between self-assessed masticatory ability, nutritional status, prosthetic status and salivary flow rate in hospitalized elders. Oral Dis. 1999;5:32–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcenes W, Steele JG, Sheiham A, Walls AW. The relationship between dental status, food selection, nutrient intake, nutritional status, and body mass index in older people. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:809–16. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh SP, Sikri G, Garg MK. Body mass index and obesity: Tailoring “cut-off” for an Asian Indian male population. Med J Armed Forces India. 2008;64:350–3. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(08)80019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla HC, Gupta PC, Mehta HC, Hebert JR. Descriptive epidemiology of body mass index of an urban adult population in western India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:876–80. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.11.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kopelman P. Health risks associated with overweight and obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8(Suppl 1):13–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maric-Bilkan C. Obesity and diabetic kidney disease. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey KV, Ferro-Luzzi A. Use of body mass index of adults in assessing individual and community nutritional status. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:673–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George B, John J, Saravanan S, Arumugham IM. Prevalence of permanent tooth loss among children and adults in a suburban area of Chennai. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:364. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.84284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Neill BV, Bullmore ET, Miller S, McHugh S, Simons D, Dodds CM, et al. The relationship between fat mass, eating behaviour and obesity-related psychological traits in overweight and obese individuals. Appetite. 2012;59:656–61. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie CS, Joshipura K, Hung HC, Douglass CW. Nutrition as a mediator in the relation between oral and systemic disease: Associations between specific measures of adult oral health and nutrition outcomes. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:291–300. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutton B, Feine J, Morais J. Is there an association between edentulism and nutritional state? J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida M, Suzuki R, Kikutani T. Nutrition and oral status in elderly people. Japanese Den Sci Rev. 2014;50:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ong G, Yeo JF, Bhole S. A survey of reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Singapore. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:124–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ong G. Periodontal disease and tooth loss. Int Dent J. 1998;48:233–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Relation of body mass index, periodontitis and Tannerella forsythia. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suresh S, Mahendra J. Multifactorial relationship of obesity and periodontal disease. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZE01–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7071.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chitsazi MT, Pourabbas R, Shirmohammadi A, Ahmadi Zenouz G, Vatankhah AH. Association of periodontal diseases with elevation of serum C-reactive protein and body mass index. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2008;2:9–14. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2008.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebersole JL, Cappelli D. Acute-phase reactants in infections and inflammatory diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2000;23:19–49. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2230103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dye BA, Choudhary K, Shea S, Papapanou PN. Serum antibodies to periodontal pathogens and markers of systemic inflammation. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1189–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winning L, Patterson CC, Cullen KM, Stevenson KA, Lundy FT, Kee F, et al. The association between subgingival periodontal pathogens and systemic inflammation. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:799–806. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]