Key Points

Question

What are the clinical and genetic features of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy with only-unilateral abnormalities in a cohort of Han Chinese patients?

Findings

In this study involving 621 patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, 20 were identified with only-unilateral abnormalities, in which the LRP5 gene was identified in more than half of all mutations.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that identification of unilateral peripheral retinal abnormalities should also consider familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and variable phenotypic penetrance of the retinal abnormalities can lead to seemingly unilateral disease.

Abstract

Importance

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) with only-unilateral abnormalities may masquerade as other vitreoretinal disorders. Clinicians should be vigilant of patients with unilateral FEVR, recognizing that the relatively normal vision of the fellow eye could compromise a patient’s attention to the decreasing vision of the affected eye.

Objective

To describe the clinical findings and genetic spectrum of patients with FEVR and only-unilateral abnormalities.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A medical records review included all patients (N = 621) with a diagnosis of FEVR between January 1, 2010, and October 31, 2017, from Xinhua Hospital in Shanghai, China. Patients were excluded if retinal abnormalities were noted in both eyes or if a diagnosis of FEVR could not be confirmed by genetic testing. Inclusion criteria included clinical diagnosis of FEVR with only-unilateral features on widefield angiography and confirmed mutations in 5 FEVR targeted genes (LRP5, FZD4, ZNF408, NDP, and TSPAN12).

Exposures

Clinical data were collected from patient medical records. Widefield angiography and targeted gene sequencing were performed in all patients of this cohort.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinical findings and genetic spectrum.

Results

Of the 621 patients with a clinical diagnosis of FEVR, 20 with unilateral FEVR (3.22%; 95% CI, 1.83%-4.61%; 18 males [90%] and a mean [SD] age at presentation of 2.6 [2.7] years) were identified. All patients were Han Chinese. The most common clinical presentations were total retinal detachment (12 [60%]) and retinal fold (6 [30%]). Mutations in the LRP5 gene were the most prevalent (11 [55%]), followed by the genes FZD4 (4 [20%]), ZNF408 (2 [10%]), TSPAN12 (2 [10%]), and NDP (1 [5%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that the identification of unilateral peripheral retinal abnormalities should include a consideration of FEVR, perhaps more often seen with mutations in the LRP5 gene; variable phenotypic penetrance of the retinal abnormalities can lead to seemingly unilateral disease.

This study describes the clinical features of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy along with the angiographic and genetic screening available to detect and manage this hereditary disease.

Introduction

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) is a rare inheritable disorder of retinal vascular development, first described by Criswick and Schepens in 1969.1 It has been demonstrated that patients with FEVR can have variable presentations, ranging from subtle avascularity of peripheral retina to retinal folds.2,3 Two prominent features of FEVR are intrafamilial variability and disease asymmetry.4,5,6,7,8,9

Typically, ophthalmologists may think of FEVR in the differential diagnosis of peripheral retinal abnormalities, which are similar to retinopathy of prematurity in the absence of a history of prematurity with bilateral features, given the genetic origin of the disease. However, variable phenotypic expressivity of the retinal abnormalities could result in one eye showing no retinal abnormalities in an individual with FEVR findings in the fellow eye.

To our knowledge, limited investigations have been conducted to date into the clinical features of FEVR, especially in an era of widefield fluorescein angiography, which can be sensitive for detecting subtle retinal abnormalities from FEVR and has the ability to perform genetic analyses of these patients. Because appropriate diagnosis of FEVR can be important for the appropriate management of both eyes in patients who might present with unilateral abnormalities that are consistent with FEVR, we undertook a study to describe the clinical spectrum of only-unilateral FEVR with the availability of widefield imaging and targeted gene sequencing.

Methods

A retrospective medical records review was conducted of all patients who received a FEVR diagnosis between January 1, 2010, and October 31, 2017, at Xinhua Hospital in Shanghai, China. The aim was to identify those with only-unilateral abnormalities in the setting of bilateral widefield fluorescein angiographic features. This study was approved with a waiver of informed patient consent by the ethics committee of Xinhua Hospital and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.10

The diagnosis of FEVR with only-unilateral abnormalities was based on the characteristic fundus findings of the affected eye, birth history, family history, and gene testing results. In our clinic, all patients with a clinical diagnosis of FEVR routinely underwent a complete ophthalmologic evaluation (eMethods in the Supplement).

The eyes with FEVR were staged using the clinical staging criteria for FEVR described previously.11

Results

A total of 20 patients (3.22%; 95% CI, 1.83%-4.61%; 18 males [90%]) with only-unilateral abnormalities were identified from 621 patients with a clinical diagnosis of FEVR. We excluded 7 patients with a clinical diagnosis of unilateral FEVR but who had no related gene mutation. The clinical characteristics of the patients with unilateral FEVR and corresponding genetic mutations are described in the Table. All patients were of Han Chinese ethnicity. Patients had a mean (SD) gestational age of 39.1 (0.89) weeks, mean (SD) birth weight of 3.42 (0.29) kg, and a mean (SD) age at presentation of 2.6 (2.7) years. A positive family history of FEVR was in 9 (45%) of 20 families.

Table. Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of the Only-Unilateral Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy in This Cohort.

| Patient No./Gestational Age, wk/Birth Weight, g | Age at Presentation | Affected Eye | Family History | Initial Diagnosis | Visual Acuity | Clinical Presentation | Disease Stage | Gene | Mutation | Type | Minor Allele Frequency | In Silico Analysis Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIFT | Poly-Phen 2 | Mutation-Taster | GERP++ | ||||||||||||

| 1/40/3250 | 2 y | OD | Positive | FEVR | LP | Temporal retinal fold | 4A | LRP5 | c.1801G>A; p.G601Ra | Missense mutation | NA | D | Pd | Dc | C |

| 2/39/3450 | 6 y | OS | Negative | PFVS | NLP | Total RD | 5B | LRP5 | c.3361A>G; p.N1121Da | Missense mutation | 0.003 | T | B | Dc | C |

| 3/38/3300 | 2 y | OS | Negative | FEVR | NLP | Total RD | 5B | LRP5 | c.G3977A;p.R1326Ha | Missense mutation | NA | T | B | P | C |

| 4/37/3100 | 2 mo | OD | Negative | PFVS | NLP | Total RD | 5B | LRP5 | c.266A>G;p.Q89R | Missense mutation | 0.003 | T | B | Dc | C |

| 5/40/3150 | 4 y | OS | Negative | FEVR | FC/BE | Temporal retinal fold | 4B | LRP5 | c.2872C>T;p.R958Wa | Missense mutation | NA | D | Pd | Dc | C |

| 6/38/3000 | 2 y | OS | Positive | RD | NA | ERD; flat AC | 5A | LRP5 | c.1969A>G;p.R657Ga | Missense mutation | NA | D | B | Dc | NC |

| 7/40/3600 | 1 y | OD | Negative | RD | NA | ERD | 5B | LRP5 | c.920C>A;p.S307Ya | Missense mutation | NA | D | Pd | Dc | C |

| 8/39/3200 | 7 y | OD | Positive | Toxocariasis | 0.6 | Nasal drag disc | 3B | LRP5 | c.1193G>A;p.R398Ha | Missense mutation | NA | D | Pd | Dc | C |

| 9/40/3450 | 2 y | OD | Negative | Coats | Temporal retinal fold; exudate | 3B | LRP5 | c.290C>T;p.A97Va | Missense mutation | 0.0008 | T | B | P | NC | |

| 10/39/3300 | 5 mo | OS | Positive | RD | NA | Total RD | 5B | LRP5 | c.893G>A;p.R298Ha | Missense mutation | 0.0008 | T | B | P | NC |

| 11/39/3600 | 3 mo | OD | Negative | FEVR | LP | Temporal retinal fold | 4B | LRP5 | c.C290T;p.A97Va | Missense mutation | 0.0008 | T | B | P | NC |

| 12/39/3600 | 8 mo | OD | Positive | PFVS | NA | Total RD | 5B | FZD4 | c.217-234del;p.73-78dela | Deletion mutation | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 13/40/3400 | 1 y | OS | Positive | PFVS | LP | Total RD | 5B | FZD4 | c.747dupC;p.Y250fsa | Frameshift mutation | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 14/39/3800 | 7 mo | OS | Negative | FEVR | FC/BE | Temporal retinal fold; exudate | 4B | FZD4 | c.686T>C; p.L229Pa | Missense mutation | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 15/38/3400 | 11 y | OD | Negative | Maculopathy | 0.25 | Peripheral vascular abnormalities and macular exudation | 1B | FZD4 | c.C205T;p.H69Y | Missense mutation | 0.0002 | D | B | Dc | C |

| 16/39/3200 | 4 y | OS | Positive | PFVS | NLP | Total RD | 5A | ZNF408 | c.1083delG;p.K361fsa | Frameshift mutation | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 17/40/3450 | 2 y | OS | Positive | PFVS | HM | Temporal retinal fold | 4B | ZNF408 | c.2125G>A;p.E709Ka | Missense mutation | NA | D | B | Dc | C |

| 18/38/3300 | 2 y | OS | Positive | RD | NLP | Total RD | 5B | NDP | c.258G>T;p.K86Na | Missense mutation | NA | D | Pd | Dc | C |

| 19/40/3500 | 2 y | OS | Negative | PFVS | NLP | Total RD | 5B | TSPAN12 | c.715A>T; p.I239Fa | Missense mutation | NA | T | B | Dc | C |

| 20/40/4300 | 1 y | OS | Negative | RD | NLP | Total RD | 5B | TSPAN12 | c.*44C>T;/ | NA | 0.0002 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: AC, anterior chamber; B, benign; BE, before eye; C, conserved; D, damaging; Dc, disease-causing, ERD, exudative retinal detachment; FC, figure counting; FEVR, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy; GERP ++, genomic evolutionary rate profiling; HM, hand moving; LP, light perception; NA, none available; NC, nonconserved; NLP, no light perception; Pd; probably damaging; PFVS, persistent fetal vasculature syndrome; RD, retinal detachment; SIFT, sorting intolerant from tolerant; T, tolerated.

The mutation site is novel that has not been reported in patients with FEVR.

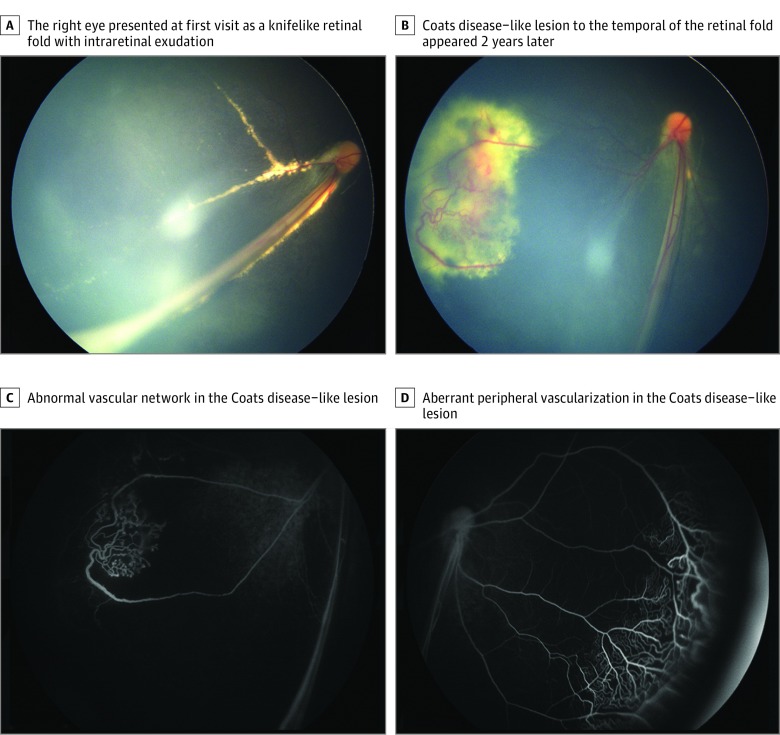

Only 5 (25%) of 20 patients received a FEVR diagnosis at the first visit. The referring diagnosis was made without genetic testing. The most common referring diagnoses were persistent fetal vasculature syndrome (PFVS; 7 patients [35%]), retinal detachment (5 [25%]), toxocariasis (1 [5%]), Coats disease (1 [5%]), and maculopathy (1 [5%]). Stage 1 FEVR was identified in 1 patient (5%), stage 3 in 2 patients (10%), stage 4 in 5 patients (25%), and stage 5 in 12 patients (60%). The most common clinical presentations were total retinal detachment (12 [60%]) and retinal fold (6 [30%]) (eFigure in the Supplement); Figure 1 illustrates representative images of the affected eyes.

Figure 1. Color and Fluorescein Angiography of Patient 9 With Coats Disease–Like Presentation Secondary to Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy.

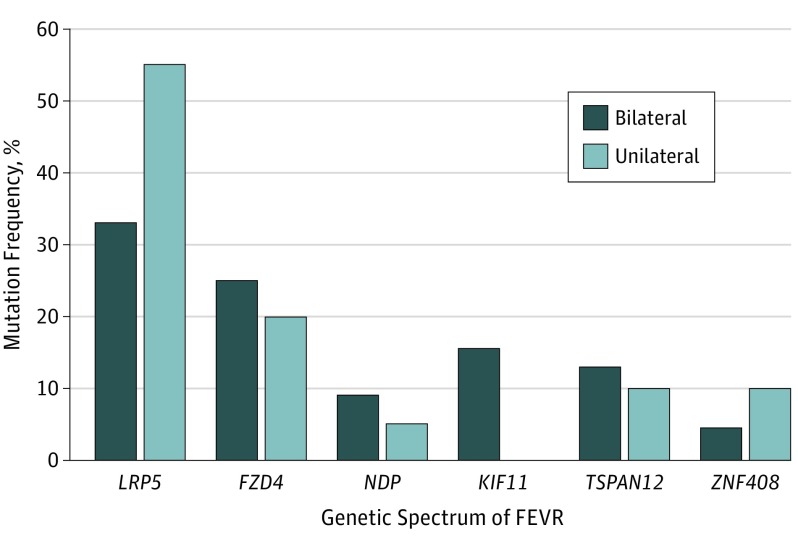

Of the 621 patients with a clinical diagnosis of FEVR, 516 patients (83.1%) underwent genetic testing. The genetic mutations were identified in 284 patients (55.0%) with bilateral FEVR and in 20 patients (3.9%) with unilateral FEVR. The genetic spectrum of bilateral and unilateral FEVR is shown in Figure 2. For the 20 patients with unilateral FEVR, mutations in the LRP5 (OMIM 603506) gene were the most frequent, which affected 11 patients (55%), followed by the genes FZD4 (OMIM 604579), with 4 (20%); ZNF408 (NCBI 79797), with 2 (10%); TSPAN12 (OMIM 613138), with 2 (10%); and NDP (OMIM 300658), with 1 (5%).

Figure 2. Genetic Spectrum in Patients With the Bilateral or the Only-Unilateral Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy (FEVR).

Among 20 patients with unilateral FEVR, LRP5 was the most frequently mutated gene in 11 (55%) patients, followed by genes FZD4 (4 [20%]), ZNF408 (2 [10%]), TSPAN12 (2 [10%]), and NDP (1 [5%]). Among 284 patients with bilateral FEVR, the most frequently mutated gene was LRP5 (93 [33%]), followed by genes FZD4 (71 [25%]), KIF11 (44 [15.5%]), TSPAN12 (37 [13%]), NDP (26 [9%]), and ZNF408 (13 [4.5%]).

Discussion

To our knowledge, limited information on FEVR with only-unilateral abnormalities existed before the present study. Widefield fluorescein angiography was used to confirm only-unilateral abnormalities, and targeted gene sequencing for FEVR was available.

In the current cohort, the rate of only-unilateral FEVR was 3.22% and the LRP5 gene was identified in more than half of all mutations. The mild unilateral FEVR makes it difficult to arouse patients’ concern to go to the hospital because the condition allowed normal vision of the fellow eye (ie, visual acuity appropriate for patient age), especially for young patients. We excluded patients who were clinically considered as having FEVR but had no mutations in related genes. These factors may be associated with the underestimation of the only-unilateral FEVR rate in this cohort.

Unilateral FEVR may easily masquerade as other vitreoretinal disorders. In this study, the most common referring diagnosis of unilateral FEVR was PFVS. Persistent fetal vasculature syndrome is a congenital disorder in which the hyaloid vasculature and primary vitreous fail to regress. Unlike the falciform fold in FEVR, the stalk in PFVS is not a retinal fold but a hyaloid stalk of persistent tissue that extends from the optic nerve to the posterior lens surface. In addition, the stalk in PFVS can insert eccentrically on the posterior lens surface, thus sparing the central visual axis and allowing for lens-sparing vitrectomy in the setting of epipapillary traction and retinal detachments. This study reminds ophthalmologists to be aware of the different diagnosis of unilateral FEVR and PFVS.

It has been reported that retinal detachments can occur in approximately 21% to 64% of individuals with FEVR.12,13,14 In this unilateral FEVR case series, 60% of patients presented with total retinal detachment with or without exudates. The high rate of patients with advanced unilateral FEVR may be because patients’ attention after birth was more heightened, and more chances were available for the unilateral FEVR to be identified in conventional fundus screening. This high rate might also reflect that the patients in this cohort were generally young on presentation. Only 1 patient presented with a mild stage of FEVR; however, his visual acuity decreased substantially, owing to the macular exudation. In a comprehensive review, Benson14 estimated that approximately 50% of patients are asymptomatic. Thus, only severe cases with unilaterally low visual acuity or abnormal performance may have an opportunity to be referred to the clinic.

The mechanisms of the only-unilateral FEVR are not yet clear. In this study, no retinal abnormalities were observed in the fellow eyes, and presentations of the affected eyes ranged from avascular periphery to drag disc to retinal fold to total retinal detachment. These findings could suggest differences in epigenetic regulations between the 2 eyes during ocular development. In this cohort, the LRP5 gene was the most frequently mutated, occurring in more than half of the patients. Through comprehensive screening, we revealed for the first time, to our knowledge, the mutation spectrum of patients of Han Chinese ethnicity who had unilateral FEVR. No clear genotype-phenotype correlation was observed in this cohort.

Conclusions

Unilateral FEVR may masquerade as other vitreoretinal disorders. This study suggests that examinations are warranted for patients with unexplained unilateral vitreoretinal disorders. These examinations may include widefield angiographic screening and targeted gene sequencing of patients and their family members to exclude FEVR.

eMethods. Criteria, Evaluation, Testing, Analysis, Validation

eFigure. Pedigrees, Chromatograms, and Clinical Presentations of Representative Patients With Entirely Unilateral Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy

References

- 1.Criswick VG, Schepens CL. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969;68(4):578-594. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(69)91237-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Nouhuys CE. Dominant exudative vitreoretinopathy and other vascular developmental disorders of the peripheral retina. Doc Ophthalmol. 1982;54(1-4):1-414. doi: 10.1007/BF00183127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gow J, Oliver GL. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. An expanded view. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;86(2):150-155. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1971.01000010152007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robitaille JM, Wallace K, Zheng B, et al. . Phenotypic overlap of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) with persistent fetal vasculature (PFV) caused by FZD4 mutations in two distinct pedigrees. Ophthalmic Genet. 2009;30(1):23-30. doi: 10.1080/13816810802464312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger W, Kloeckener-Gruissem B, Neidhardt J. The molecular basis of human retinal and vitreoretinal diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29(5):335-375. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikopoulos K, Venselaar H, Collin RW, et al. . Overview of the mutation spectrum in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and Norrie disease with identification of 21 novel variants in FZD4, LRP5, and NDP. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(6):656-666. doi: 10.1002/humu.21250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmour DF. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and related retinopathies. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(1):1-14. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gal M, Levanon EY, Hujeirat Y, Khayat M, Pe’er J, Shalev S. Novel mutation in TSPAN12 leads to autosomal recessive inheritance of congenital vitreoretinal disease with intra-familial phenotypic variability. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(12):2996-3002. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashani AH, Brown KT, Chang E, Drenser KA, Capone A, Trese MT. Diversity of retinal vascular anomalies in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2220-2227. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pendergast SD, Trese MT. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Results of surgical management. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(6):1015-1023. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranchod TM, Ho LY, Drenser KA, Capone A Jr, Trese MT. Clinical presentation of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(10):2070-2075. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shukla D, Singh J, Sudheer G, et al. . Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR). Clinical profile and management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003;51(4):323-328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benson WE. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1995;93:473-521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Criteria, Evaluation, Testing, Analysis, Validation

eFigure. Pedigrees, Chromatograms, and Clinical Presentations of Representative Patients With Entirely Unilateral Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy