Abstract

Depression is a known risk factor for antiretroviral therapy (ART) non-adherence, but little is known about the mechanisms explaining this relationship. Identifying these mechanisms among people living with HIV (PLHIV) after release from prison is particularly important, as individuals during this critical period are at high risk for both depression and poor ART adherence. 347 PLHIV recently released from prison in North Carolina and Texas were included in analyses to assess mediation of the relationship between depressive symptoms at 2 weeks post-release and ART adherence (assessed by unannounced telephone pill counts) at weeks 9-21 post-release by the hypothesized explanatory mechanisms of alcohol use, drug use, adherence self-efficacy, and adherence motivation (measured at weeks 6 and 14 post-release). Indirect effects were estimated using structural equation models with maximum likelihood estimation and bootstrapped confidence intervals. On average, participants achieved 79% ART adherence. The indirect effect of depression on adherence through drug use was statistically significant; greater symptoms of depression were associated with greater drug use, which was in turn associated with lower adherence. Lower adherence self-efficacy was associated with depressive symptoms, but not with adherence. Depression screening and targeted mental health and substance use services for depressed individuals at risk of substance use constitute important steps to promote adherence to ART after prison release.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, adherence, depression, drug use, incarceration, mediation

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of HIV infection among incarcerated persons is several times that of the general population [1,2]. While incarcerated people living with HIV (PLHIV) receive and largely take treatment successfully during incarceration, many have trouble maintaining adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) after release from prison [3–5], increasing their risk of disease progression and transmission to others. Depression is an important risk factor for medication non-adherence [6–8], and is associated with an increased risk of adverse HIV health outcomes including mortality [9–15]. The risk posed by depression for HIV treatment outcomes is of concern for this population, as the prevalence of major depression in U.S. state prisoners is estimated to be between 9% and 29% [16], and may be as high as 45% among prisoners living with HIV [17]. Because of the burden of depression in this population and the risk it poses for ART non-adherence, there is a need to understand how depressive symptoms negatively affect adherence to ART in the critical period after release from prison to inform targeted interventions.

At present, there is limited understanding of the mechanisms explaining the link between depression and ART non-adherence [7]. The few existing studies specifically testing explanatory mechanisms of the relationship between depression and adherence suggest four potential mechanisms: 1) adherence self-efficacy [18–20]; 2) adherence motivation [18]; 3) lifestyle organization and routinization [21], or difficulty fitting ART regimen into daily lifestyle [22]; and 4) substance use [23]. Further studies pertaining to negative affect, rather than depression specifically, suggest that concerns about the adverse effects of ART [24], avoidant coping [25], and difficulty obtaining medication [22] may also help to explain the relationship between negative affect and ART non-adherence. Known barriers to ART adherence including concentration difficulties, sleep disruption, and poor appetite [26] - known symptoms of depression - may also be plausible explanatory mechanisms linking depression and adherence [27]. Importantly, none of these previous mediation studies were conducted among incarcerated persons, a key population for addressing disparities in HIV clinical outcomes in the U.S. Evidence of mechanisms explaining the relationship between depression and ART non-adherence in incarcerated and recently incarcerated PLHIV is needed to understand how to improve treatment outcomes in this important population.

To build this evidence, we aimed to identify explanatory mediators of the relationship between depressive symptoms and ART adherence in an incarcerated population following release from prison using data from a randomized controlled trial of an intervention designed to enhance linkage to care and ART adherence and for newly released prisoners living with HIV [28,29]. We tested the indirect effect of depressive symptoms on adherence to ART through four hypothesized mediators, which were selected on the basis of a review of the current literature and previous qualitative work with the study population [30]: alcohol use, drug use, adherence self-efficacy, and adherence motivation. We specifically hypothesized that all mediators would independently partially mediate the relationship between symptoms of depression two weeks after release from prison and ART adherence through 24 weeks post-release. In testing these mediation hypotheses, our aim was to identify cognitive and behavioral targets for future interventions aiming to promote ART adherence in the context of elevated depressive symptoms at the time of release from prison.

METHODS

Study Context

This study was conducted using data from a randomized controlled trial of a program designed to promote linkage to care and ART adherence among PLHIV newly released from prison, Project imPACT (Individuals Motivated to Participate in Adherence, Care, and Treatment; R01DA030793). The design of the imPACT trial has been described previously [28,29]. Study recruitment took place in the North Carolina and Texas criminal justice systems, which together represent 15% of all persons in U.S. state prisons. Eligible participants were randomized to the imPACT intervention arm or standard care. The intervention was designed to promote rapid engagement in HIV care after release from prison and consisted of three main components: motivational interviewing before and after release, pre-release needs assessment and medical care link coordination, and text message reminders for each antiretroviral medication dose. The data presented in the current study are taken from questionnaires and pill-count measures of ART adherence collected longitudinally after release from prison for the evaluation of this trial.

Study Participants and Procedures

PLHIV incarcerated within the Texas Department of Criminal Justice or North Carolina Department of Public Safety were recruited to participate. To be eligible for enrollment in the imPACT trial, participants had to be English-speaking, at least 18 years of age, treated with ART, virally suppressed (plasma HIV RNA level < 400 copies/mL) within 90 days prior to release, and willing and able to provide written consent. Participants also needed to have an expected prison release date within approximately 12 weeks after enrollment and to not have been convicted of violent offenses in order to minimize risk to study staff. Enrollment began in March 2012 and all study procedures were completed by February 2015. A total of 405 participants were enrolled in Texas (n=242) and North Carolina (n=163), and 381 total participants were randomized to the study arms. There were 24 withdrawals from the study following randomization due to ineligibility (primarily due to sentence extensions or threats to the safety of study staff). Forty-one participants (11%) were reincarcerated by week 9 post-release and 63 (17%) were reincarcerated by 21 weeks post-release. Participants completed a baseline study visit in prison and an additional pre-release visit approximately 2 to 4 weeks before anticipated release. Post-release study visits were scheduled at weeks 2, 6, 14, and 24 after release, at which time participants completed behavioral questionnaires and other study procedures. Unannounced pill counts were conducted by phone at weeks 1, 5, 9, 13, 17, and 21 after release.

Ethical Review

All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Texas Christian University (TCU) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), as well as by human subjects committees at each prison system and authorized by the US Office of Human Research Programs (OHRP). All participants completed individual informed consent.

Measures

Adherence.

The primary outcome of the present analysis was adherence to ART measured by pill counts. Study staff conducted monthly unannounced phone-based pill counts, which have been shown to be a valid, objective measure of ART adherence [31–33]. A baseline pill count was conducted shortly after release to account for all medications. During each monthly pill count, participants were asked to count and report how many pills they had remaining in their monthly pill bottle. The expected number of pills a participant should have had remaining that month was determined using prescription label data and the number of pills dispensed, as reported over the phone by the participant. The observed number of pills taken since the previous count was calculated as the number of counted pills subtracted from the number of pills at the previous count, adjusting for pills dispensed and any other gains and losses. Similarly, the expected number of pills taken since the prior count was calculated based on the number of intervening days and the prescribed number of pills to be taken per day. Adherence was calculated as a ratio of the observed pills taken to expected pills taken, resulting in a continuous proportion ranging from 0 to 1. A mean proportion of adherence was calculated across pill counts taken at weeks 9, 13, 17, and 21 for analysis.

Depressive symptoms were measured at 2 weeks after release using the modified Texas Christian University Psychological Functioning (TCU PSY) Form, which has demonstrated high reliability and validity in this population [34,35]. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which 6 depressive symptoms applied to them on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “disagree strongly” to 5 “agree strongly.” Participants were asked if in general they would say that they: 1) feel interested in life; 2) feel sad or depressed; 3) feel extra tired or run down; 4) worry or brood a lot; 5) feel hopeless about the future; and 6) feel lonely. The depression items showed good internal consistency in the study sample at 2 weeks post-release (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.83). A depressive symptom score for each participant was calculated as the mean of their responses to the 6 items (range 1 to 5, with a higher score indicating a higher level of depressive symptoms).

Hypothesized mediators

Substance use.

Alcohol use was measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [36] at weeks 6 and 14 post-release. Participants were asked a series of 10 questions about the frequency of alcohol use and alcohol-related events over the past 30 days rated on a scale from 0 to 4. A sum score was calculated ranging from 0 to 40 with greater scores indicating more severe alcohol use [36]. A score of 8 or more is associated with harmful or hazardous drinking, and a score of 13 or more in women or 15 or more in men indicates likely alcohol dependence [36]. Drug use over the past 30 days was measured using the TCU Drug Screen [34,37] at weeks 6 and 14 post-release. Participants were asked a set of 9 yes/no questions about their use of illegal drugs or prescription medications for non-medical reasons over the past 30 days. A sum score of “yes” responses was calculated for each participant ranging from 0 to 9 with a score of 3 or greater indicating likely drug dependence [38]. Mean values of alcohol use and drug use scores for weeks 6 and 14 were calculated for analysis.

Cognitive mediators.

Adherence self-efficacy and motivation were each measured at weeks 6 and 14 post-release. Adherence self-efficacy was measured using the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES) [39]. Participants were asked to rate 12 items projecting their perceived self-efficacy to adhere to their ART regimen over the next 30 days (e.g. “In the next 30 days, how confident are you that you can: Fit taking your HIV medicines into your daily routine?”) on a 10-point scale (range: 0 “cannot do at all” to 10 “completely certain can do”), and a mean of the items was taken to create a total score. The adherence self-efficacy items showed good internal consistency in the study sample at baseline (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.93). The adherence motivation measure used was adapted from a measure of motivation to practice safer sex used in the Safe Talk study, with items modified to reflect ART adherence rather than safe-sex practices [40]. Participants were asked to rate 7 items projecting their motivation to adhere to their ART regimen over the next 30 days (e.g. “In the next 30 days, how important or unimportant will it be to you to stop whatever you are doing to take your HIV medicine on time?”) on either a three-point or four-point scale, and a sum of the items was taken to create a total score (Range 0 to 24). The adherence motivation items showed good internal consistency in the study sample at baseline (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.75). Mean values of adherence motivation and self-efficacy scores for weeks 6 and 14 were calculated for analysis.

Analysis

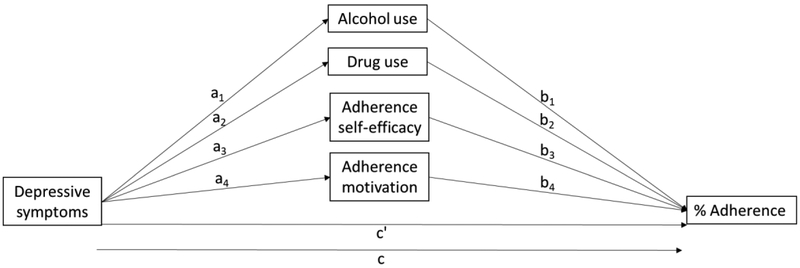

Participants who were not reincarcerated within 9 weeks of release from prison are included in the analyses presented. Descriptive statistics of participant demographic characteristics and key analytic variables were generated in SAS version 9.4. The total effect of depression on ART adherence (c path; see path diagram Figure 1), the direct effect of depression on adherence controlling for all mediators and covariates (c’ path), path effects of depression on each mediator (a paths), path effects of each mediator on ART adherence (b paths), and indirect effects of depression on adherence through each mediator were estimated using structural equation models with maximum likelihood estimation and bootstrapped confidence intervals in Mplus version 8. All models controlled for age, sex, treatment arm, and state of incarceration. The presence of statistical mediation was determined by bootstrapped confidence intervals based on 10,000 bootstrap resamples of each estimated indirect effect.

Figure 1.

Path diagram of mediation hypotheses

We assessed two assumptions necessary for the causal interpretation of observed indirect effects [41]: 1) additivity of mediated effects; and 2) sequential ignorability (no unmeasured pre-exposure confounders). We first assessed the assumption of additivity of indirect effects, or the assumption that there are no interactions or mutual causation between the mediators, and no exposure-mediator interactions [42]. To do this, we tested interaction terms for all combinations of the four hypothesized mediators, and theoretically and quantitatively assessed potential causal relationships between the mediators. No significant interactions between the mediators were found, and while there were significant correlations between some of the mediators (ranging in absolute value from 0.12 to 0.42), based on our review of these potential relationships in the literature, we found that the larger correlations were likely attributable to a common cause, such as depressive symptoms, rather than to mutual causality. There was no significant interaction between the exposure (depressive symptoms) and any mediator. Finally, to assess the robustness of our results to potential unmeasured pre-exposure confounding (sequential ignorability assumption, i.e. no unmeasured confounding variables of the effect of X on M assessed prior to X, and no unmeasured confounding variables of the effect of M on Y assessed prior to X), we conducted sensitivity analyses to estimate the predicted indirect effect for each mediator for which the observed effect was statistically significant at different levels of ρ (residual correlation between M and Y) [43,44].

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

347 participants who were not reincarcerated within 9 weeks of prison release were included in the analyses. The majority were male (78%), and on average 43 years of age. Two-thirds of participants were black (68%) and a quarter were white (24%). Participants had been incarcerated for an average of 2 years. Most participants had a high school education or less (74%) and had never been married (63%).

On average, participants achieved 79% ART adherence over weeks 9-21 post-release. The average depressive symptom score at 2 weeks post-release was 2 (range 1-5, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity). At weeks 6 and 14 post-release, 57% of participants reported any alcohol use and 24% reported any drug use. Thirteen percent of participants had an AUDIT score at either week 6 or 14 indicating hazardous alcohol use (score ≥ 8). Participants’ reported adherence self-efficacy was high at weeks 6 and 14, with a mean score of 9.6 out of a total possible score of 10. Reported adherence motivation was also high, with a mean score of 22 out of a total possible score of 24.

Path effects

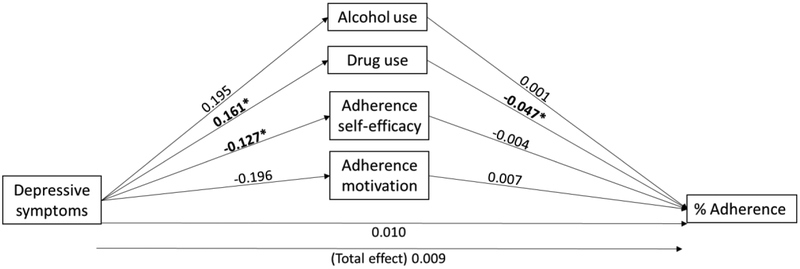

Effects corresponding to the “a” (depression to mediator), “b” (mediator to adherence), and total effect “c” paths are reported in Table 2 (see Figure 2 for path depiction of estimates). The total effect of depressive symptoms on adherence was non-significant (c path: β=0.009; 95% CI: −0.016, 0.035). In the case of a non-significant total effect, mediation is still possible if the direction of the indirect effect is the opposite of the total effect [45]. Alcohol use was not associated with depressive symptoms (a1 path: β=0.195; 95% CI: −0.231, 0.676), or adherence (b1 path: β=0.001; 95% CI: −0.005, 0.006). However, greater depressive symptoms were associated with greater drug use (a2 path: β=0.161; 95%CI: 0.069, 0.280), which was in turn associated with lower adherence (b2 path: β=−0.047; 95%CI: −0.090, −0.005). Adherence self-efficacy was associated with depressive symptoms (a3 path: β=−0.127; 95% CI: −0.230, −0.031), but not with adherence (b3 path: β=−0.004; 95% CI: − 0.034, 0.035). Adherence motivation was not associated with depressive symptoms (a4 path: β=−0.196; 95% CI: −0.535, 0.079), or adherence (b4 path: β=0.007; 95% CI: −0.004, 0.021).

Table 2.

Adjusted coefficient estimates for path, indirect, direct, and total effects

| Mediator (M) | Effect of depression on M (a) |

Effect of M on adherence (b) |

Indirect effect | Total indirect effect |

Direct effect (c') | Total effect (c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alcohol use | 0.195 (−0.231, 0.676) |

0.001 (−0.005, 0.006) |

0.000 (−0.001, 0.003) |

−0.008 (−0.021, −0.001) |

0.010 (−0.005, 0.006) |

0.009 (−0.016, 0.035) |

| drug use |

0.161 (0.069, 0.280) |

−0.047 (−0.090, −0.005) |

−0.007 (−0.019, −0.001) |

|||

| adherence self-efficacy |

−0.127 (−0.230, −0.031) |

−0.004 (−0.034, 0.035) |

0.000 (−0.004, 0.006) |

|||

| adherence motivation | −0.196 (−0.535, 0.079) |

0.007 (−0.004, 0.021) |

−0.001 (−0.006, 0.001) |

Note: All models include age, sex, treatment arm, and state of incarceration as covariates. Bolded estimates are statistically significant (non-zero 95% confidence interval)

Figure 2.

Adjusted coefficient esimates for path, direct, and total effects

*statistically significant (non-zero 95% confidence interval – see Table 2)

Mediation: indirect and direct effects

Despite a non-statistically significant total effect, the total indirect effect for all four mediators was significant (Table 2; β=−0.008; 95% CI: −0.021, −0.001). Most of the total indirect effect was attributable to the significant indirect effect of depression on adherence through drug use (β=−0.007; 95% CI: −0.019, −0.001). No other individual indirect effects were statistically significant. For the total mediated model, the direct effect (effect of depressive symptoms on adherence controlling for all mediators and covariates) was non-statistically significant (c’ path: β=0.010; 95% CI: −0.005, 0.006), slightly larger than the total effect (c path: β=0.009; 95% CI: −0.016, 0.035), and in the opposite direction of the indirect effect, indicating inconsistent mediation or suppression of the relationship between depressive symptoms and ART adherence by drug use [45].

Sensitivity Analysis

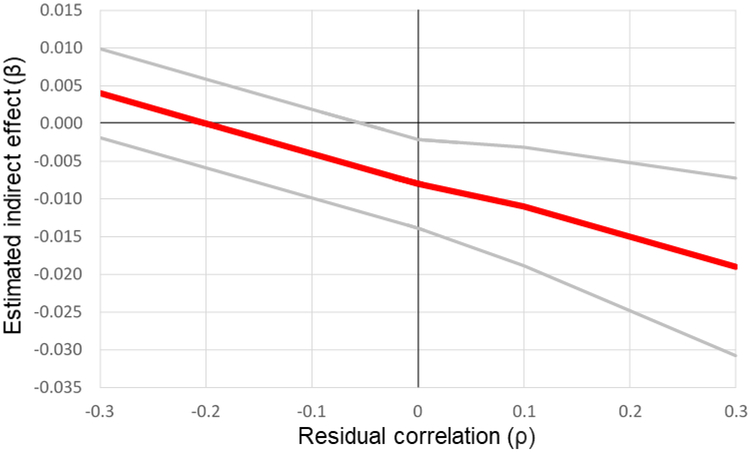

To assess the extent to which the observed indirect effect through drug use was robust to unmeasured pre-exposure confounders, we estimated the predicted indirect effect at various values of ρ, or the correlation of the model residual for adherence and the model residual for drug use. We found that the significance of the observed indirect effect was robust for all positive values of ρ, but that the effect was predicted to be non-significant for negative values of ρ exceeding approximately −0.05 (Figure 3). A negative value of ρ might be expected if individuals had lower drug use than expected given depressive symptoms, and also had higher levels of adherence than would be expected given their levels of drug use and depressive symptoms. This issue could also arise if individuals had higher drug use than expected given depressive symptoms, and also had lower levels of adherence than would be expected given their levels of drug use and depressive symptoms. We have no reason to expect that either of these scenarios would be likely to occur.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis: Estimated indirect effect and confidence interval by values of ρ

DISCUSSION

PLHIV recently released from prison with more severe depressive symptoms reported higher levels of drug use, and those reporting greater drug use in turn had lower levels of adherence to ART. The indirect (mediated) effect of depression on adherence through drug use was statistically significant, while the total effect of depression on ART adherence was not significant in this population. This pattern of mediation, known as suppression [43], indicates the existence of an unobserved alternative pathway by which greater depressive symptoms are associated with higher adherence. We found no evidence to support alcohol use, adherence self-efficacy, or adherence motivation as mediators of the relationship between depression and adherence. We discuss these findings and implications for research and practice in detail below.

Drug use links depression to lower ART adherence

The primary hypothesis supported by the results was that of the mediating role of drug use in the relationship between depressive symptoms and adherence to ART. Participants with greater depressive symptoms reported higher levels of drug use, and those reporting greater drug use in turn had lower levels of adherence to ART. Our results suggest that PLHIV recently release from prison with elevated depressive symptoms may be at risk of greater substance use, and therefore lower ART adherence.

We are aware of only one previous study evaluating drug use as a mediator of the relationship between depression and adherence [23], the results of which did not support drug use as a mechanism explaining this relationship in a population of non-incarcerated men who have sex with men (MSM) in the U.S. Given the preponderance of evidence linking depression and drug use [46], and drug use and adherence [47,48], it would follow that drug use should, at least partially, explain the relationship between depression and adherence. Models of cognitive escape suggest that negative or depressed affect can lead to avoidant coping behaviors [49], such as substance use, which lead to cognitive disengagement that decreases the likelihood of maintaining healthy behaviors, such as medication adherence [50]. In previous qualitative work with the study population, we found that many PLHIV struggle to maintain ART adherence after release from prison, and often link these lapses in adherence to substance use [30]. Participants in the qualitative study described the high availability of drugs and relationships with drug using social networks in their home communities as factors precipitating their drug use [30]. Understanding this context may help to understand why drug use is an important mechanism in the depression-adherence relationship in this population while it may not be in others.

The pattern of mediation by drug use of the relationship between depressive symptoms and ART adherence indicated suppression, or inconsistent mediation, of the relationship by drug use [45], with the indirect effect through drug use being negative, and the direct effect being positive and slightly larger than the total effect (which was non-significant). This pattern of mediation suggests that there are one or more unobserved mechanisms through which greater depressive symptoms may actually be associated with higher ART adherence, explaining the non-significant total relationship observed between depressive symptoms and adherence in this population [45]. While in the present study we are unable to elucidate reasons for which greater symptoms of depression may be associated with higher adherence in some cases, one potential scenario may be that some patients with high levels of depressive symptoms may be likely to be referred to mental health treatment services. Receipt of these services may lead to higher levels of adherence for these individuals as compared to their peers not receiving these services. Few studies have found such a positive association between depression and ART adherence. In one case, ART adherence was higher in PLHIV diagnosed with depression (HIV-infected drug users enrolled in New York State Medicaid) [51]. The authors of this study further found that over 80% of individuals diagnosed with depression received either psychiatric care or antidepressant therapy, and only one-third with no such diagnosis received mental health services. Together, these results suggest that mental health care utilization may help to explain the potential for higher adherence among certain depressed individuals. Intervention studies delivering mental health and substance use services to PLHIV indicate that these strategies can effectively promote adherence among individuals diagnosed with depression [8,52], suggesting that utilization of these services may serve to mitigate (modify) the relationship between depression and ART non-adherence. To formally assess this hypothesis, future studies should test the extent to which receipt of mental health and substance use services modifies the relationship between depression, drug use, and ART adherence.

While this alternative mechanism remains to be understood, our results do indicate that symptoms of depression may be an important risk-factor for drug use following release from prison, and therefore for lower adherence to ART. This mechanism may be salient for other populations, as an estimated one-third of PLHIV suffer from depression [53], and up to 60% of PLHIV will experience a substance use disorder in their lifetime [54–56]. Our results emphasize the importance of considering both depression and substance use history in identifying individuals for targeted adherence interventions during the critical period after release from prison. A number of strategies exist for the treatment of co-occurring mood and substance use disorders, including individual and group counseling [57], contingency management approaches [58], and pharmacotherapies [46]. Successful treatment may allow PLHIV with substance use disorders to achieve similar HIV treatment outcomes to their peers who do not use drugs [59]. While many evidence-based treatments for co-occurring depression and substance use disorders exist, effective strategies to facilitate linkage to these services during community re-entry are needed. One such program for linkage to care is the Assess, Plan, Identify, and Coordinate (APIC) model [60]. In this system-level model, a coordinating committee of prison representatives and community providers coordinate to facilitate access to mental health and substance use treatment during community reentry [60]. The primary elements of this model include a comprehensive needs assessment for each individual prior to reentry, system- and individual-level planning for treatment and service provision, identification of programs responsible for post-release services, and coordination of care as individuals transition from prison to the community [60]. The potential for this and other system-level models to not only increase access to behavioral health services but also to promote retention in and adherence to HIV treatment should be evaluated.

Unsupported mediation hypotheses

We did not find support for the cognitive attributes of adherence self-efficacy and adherence motivation as explanatory mediators in the relationship between depressive symptoms and ART adherence in this population of recently incarcerated PLHIV. Previous studies have found support for adherence self-efficacy as a mediator of this relationship in clinical populations in the U.S. [19,61], and Uganda [18]. While we did find that greater depressive symptoms were associated with lower adherence self-efficacy in this population, greater adherence self-efficacy was not associated with higher ART adherence. We also did not find adherence motivation to be associated with either depressive symptoms or adherence. One previous study found some support for adherence motivation as a mediator of the depression-adherence relationship, but further found that when adherence self-efficacy was introduced as a competing mediator, the indirect effect through adherence motivation was no longer statistically significant [18]. In addition, empirical [19] and theoretical [62] models suggest that adherence motivation may be an important precursor to adherence self-efficacy. Taken together, this suggests that adherence self-efficacy may be a more proximate determinant of adherence behavior than adherence motivation, though we found no support for either mechanism. One reason for this null finding could be the very high self-reported levels of adherence self-efficacy and motivation in this population, creating potential ceiling effects in the ability to observe significant associations with these variables. Alternatively, these cognitive constructs may be less relevant explanatory mechanisms in the link between depressive symptoms and ART adherence in this population than in others. While our results support the relationship between depressive symptoms and lower adherence self-efficacy, it may simply be the case that self-efficacy is not the most important limiting factor in ART adherence in this population.

Our results also did not support alcohol use as a mechanism explaining the depression-adherence relationship. One previous study did find that alcohol use partially explained the relationship between depression and appointment adherence, but not medication adherence, among men living with HIV in Chicago [23]. Other studies support the link between depression and alcohol use [63–65], and between alcohol use and ART non-adherence [66] separately. Given this evidence, it would seem likely that alcohol use would be an important mechanism linking depressive symptoms and ART non-adherence. Though this hypothesis was not supported in this population, it should be noted that the level of reported alcohol use in this population was relatively low. Given the paucity of studies evaluating alcohol use as a mediator of the relationship between depression and adherence, more research is needed to understand the explanatory power of the use of alcohol and other substances in this relationship.

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with key limitations in mind. Depressive symptoms were measured through self-report, thus we cannot assume a clear relationship between the magnitude of these reported symptoms and a clinical diagnosis. About two-fifths of pill counts were missed due to missed contacts, re-incarceration, and loss to follow-up. Potential bias in estimates associated with adherence based on missing pill counts was mitigated through the use of maximum likelihood estimation. Measurement of ART adherence through unannounced telephone pill counts may be imperfect because counts cannot be visually confirmed, but the evidence supports these counts as a valid and reliable measure of adherence [31–33]. In testing hypotheses related to adherence self-efficacy and motivation, there may have been ceiling effects in the ability to detect significant associations given that reported scores on both measures were high. Given that the intervention being evaluated in the parent trial aimed to increase adherence motivation and self-efficacy, treatment group participants may have been particularly susceptible to social desirability bias in reporting these measures. Recently incarcerated persons may also be wary of reporting substance use, but participants were ensured of the confidentiality of their disclosures in response to study questionnaires to encourage candor. The observed associations cannot necessarily be assumed to be causal, but given the temporality of observations and apparent robustness of the observed relationships to unmeasured confounders, there is some ground to infer causal relationships where significant associations were found. The results of this study may not be generalizable to individuals who have not achieved viral suppression while incarcerated, or to individuals convicted of violent crimes. Of the 1802 individuals assessed for eligibility, 307 (17%) were ineligible because they were not virally suppressed (plasma HIV RNA < 400 copies/mL) within 90 days prior to release from prison. Despite this restriction of eligibility, participants in this study did display a wide range of adherence levels during the observation period after release from prison (Mean=79.3%, SD=18.1%). Fourteen percent (247) of individuals approached were ineligible because they had been convicted of violent offenses such as those related to sexual assault, serious injury, or death (to minimize risk to study staff). Finally, the context of incarceration and home communities of recently incarcerated persons in Texas and North Carolina may be qualitatively different than those in other states and regions of the U.S. While we cannot say that the study population is representative of all incarcerated populations in the U.S., it does represent an important incarcerated population as prisoners in these two states represent one-seventh of all prisoners in the country.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that PLHIV recently released from prison who suffer from depression are at increased risk of drug use, and therefore may have lower levels of ART adherence. Given the burden of depression in incarcerated populations, and overwhelming evidence linking depression and ART non-adherence, approaches to mitigate this relationship are needed. Our findings suggest that screening for depression and targeting mental health services to depressed individuals at risk of substance use constitute important steps to promote adherence to ART after prison release.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n=347)*

| No.(%) or Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 42.5 ± 9.6 |

| Male sex | 272 (78.4%) |

| Race | |

| White | 82 (23.9%) |

| Black | 233 (67.9%) |

| Other | 28 (8.2%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 27 (1.8%) |

| Incarceration length (y) | 2.0 ± 3.2 |

| Education level | |

| Some high school | 135 (38.9%) |

| High school/GED | 123 (35.5%) |

| Some college/trade school | 89 (25.7%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 55 (15.9%) |

| Formerly married | 74 (21.3%) |

| Never married | 218 (62.8%) |

| Mean adherence (weeks 9-21) | 79.3% ± 18.1% |

| Depressive symptoms (week 2) | 2.1 ± 0.9 |

| Alcohol use (AUDIT) | |

| Mean score weeks 6 & 14 | 2.3 ± 4.1 |

| Any alcohol use weeks 6 & 14 | 169 (57.1%) |

| Hazardous alcohol use week 6 or 14 (score ≥ 8) | 39 (13.4%) |

| Likely alcohol dependence week 6 or 14 (women≥13; men≥15) | 13 (4.5%) |

| Drug use | |

| Mean score weeks 6 & 14 | 0.2 ± 0.8 |

| Any drug use weeks 6 & 14 | 71 (24.3%) |

| Likely drug dependence (score ≥ 3) | 4 (1.4%) |

| Drug use type (any use in past 30 days at week 6 or 14) | |

| Cannabis | 50 (17.2%) |

| Cocaine (any form) | 43 (14.8%) |

| Other | 23 (7.9%) |

| Adherence self-efficacy (mean weeks 6 & 14) | 9.6 ± 0.8 |

| Adherence motivation (mean weeks 6 & 14) | 21.9 ± 2.1 |

Reported at baseline unless otherwise noted

FUNDING/ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA030793) and the UNC Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410). This research was partially supported by a National Research Service Award Post-Doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (T32 HS000032). Dr. Golin’s salary was partially supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K24 HD069204). Dr. Wohl’s salary (K24 DA037101) and Dr. Gottfredson’s salary (K01 DA035153) were partially supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Ethical approval:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent:

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wohl DA, Golin C, Rosen DL, May JM, White BL. Detection of undiagnosed HIV among state prison entrants. JAMA. 2013;310:2198–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Screening of Male Inmates During Prison Intake Medical Evaluation-Washington, 2006-2010. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2011. June 24;60(24):811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301:848–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Springer SA, Qiu J, Saber-Tehrani AS, Altice FL. Retention on buprenorphine is associated with high levels of maximal viral suppression among HIV-infected opioid dependent released prisoners. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien H-C, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:84–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: an agenda for further research and action. J Urban Health. 2012;89:98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sin NL, DiMatteo MR. Depression treatment enhances adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:259–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burack JH, Barrett DC, Stall RD, Chesney MA, Ekstrand ML, Coates TJ. Depressive symptoms and CD4 lymphocyte decline among HIV-infected men. JAMA. 1993;270(21):2568–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leserman J, Petitto JM, Perkins DO, Folds JD, Golden RN, Evans DL. Severe stress, depressive symptoms, and changes in lymphocyte subsets in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men. A 2-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vedhara K, Nott KH, Bradbeer CS, Davidson EA, Ong EL, Snow MH, et al. Greater emotional distress is associated with accelerated CD4+ cell decline in HIV infection. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, Laurenceau JP, Balbin E, Klimas N, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:1013–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson TL, Shaw WS, Semple SJ. Relationship of psychosocial factors to HIV disease progression. 1996;18:30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.PageShafer K, Delorenze GN, Satariano WA. Comorbidity and survival in HIV infected men in the San Francisco Men’s Health Survey. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001;285:1466–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prins SJ. Prevalence of mental illnesses in US State prisons: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:862–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheyett A, Parker S, Golin C, White B, Davis CP, Wohl D. HIV-infected prison inmates: depression and implications for release back to communities. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:300–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner GJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Robinson E, Ngo VK, Glick P, Mukasa B, et al. Effects of Depression Alleviation on ART Adherence and HIV Clinic Attendance in Uganda, and the Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Motivation. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatum AK, Houston E. Examining the interplay between depression, motivation, and antiretroviral therapy adherence: a social cognitive approach. AIDS Care. 2017;29:306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babowitch J, Vanable PA, Sweeney SM. Self-Efficacy Mediates the Association of Depression to Antiretroviral Medication Adherence among Hiv-Positive Outpatients. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:S2057–S2057. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magidson JF, Blashill AJ, Safren SA, Wagner GJ. Depressive symptoms, lifestyle structure, and ART adherence among HIV-infected individuals: a longitudinal mediation analysis. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker JS, Orlando M, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung F-Y, Gifford AL. Psychosocial mediators of antiretroviral nonadherence in HIV-positive adults with substance use and mental health problems. Health Psychol. 2004;23:363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Bois SN, McKirnan DJ. A longitudinal analysis of HIV treatment adherence among men who have sex with men: a cognitive escape perspective. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1425–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Llabre MM, Durán RE, Antoni MH, Schneiderman N, et al. Physical symptoms, beliefs about medications, negative mood, and long-term HIV medication adherence. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver KE, Llabre MM, Durán RE, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Penedo FJ, et al. A stress and coping model of medication adherence and viral load in HIV-positive men and women on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Health psychology. 2005;24:385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez JS, Psaros C, Batchelder A, Applebaum A, Newville H, Safren SA. Clinician-assessed depression and HAART adherence in HIV-infected individuals in methadone maintenance treatment. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42:120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kidia K, Machando D, Bere T, Macpherson K, Nyamayaro P, Potter L, et al. I was thinking too much ’: experiences of HIV-positive adults with common mental disorders and poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe. Trap Med Int Health. 2015;20:903–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golin CE, Knight K, Carda-Auten J, Gould M, Groves J, L White B, et al. Individuals motivated to participate in adherence, care and treatment (imPACT): development of a multi-component intervention to help HIV-infected recently incarcerated individuals link and adhere to HIV care. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wohl DA, Golin CE, Knight K, Gould M, Carda-Auten J, Groves JS, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intervention to Maintain Suppression of HIV Viremia After Prison Release: The imPACT Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75:81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haley DF, Golin CE, Farel CE, Wohl DA, Scheyett AM, Garrett JJ, et al. Multilevel challenges to engagement in HIV care after prison release: a theory-informed qualitative study comparing prisoners’ perspectives before and after community reentry. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14:1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Cherry C, Flanagan J, Pope H, Eaton L, Kalichman MO, Cain D, Detorio M, Caliendo A, Schinazi RF. Monitoring medication adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV clinical trials. 2008. October 1;9(5):298–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fredericksen R, Feldman BJ, Brown T, Schmidt S, Crane PK, Harrington RD, et al. Unannounced telephone-based pill counts: a valid and feasible method for monitoring adherence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:2265–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalichman SC, Amaral C, Swetsze C, Eaton L, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, Detorio M, Caliendo AM, Schinazi RF. Monthly unannounced pill counts for monitoring HIV treatment adherence: tests for self-monitoring and reactivity effects. HIV clinical trials. 2010. December 1; 11 (6):325–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson DD, Joe GW, Knight K, Rowan-Szal GA, Gray JS. Texas Christian university (TCU) short forms for assessing client needs and functioning in addiction treatment. J Offender Rehabil. 2012;51:34–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowan-Szal GA, Joe GW, Bartholomew NG, Pankow J, Simpson DD. Brief trauma and mental health assessments for female offenders in addiction treatment. Journal of offender rehabilitation. 2012. February 29;51(1-2):57–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters RH, Greenbaum PE, Steinberg ML, Carter CR, Ortiz MM, Fry BC, Valle SK. Effectiveness of screening instruments in detecting substance use disorders among prisoners. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000. June 1;18(4):349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpson DD, Knight K, Broome KM. TCU/CJ forms manual: Drug dependence screen and initial assessment. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, Chesney MA. The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES). J Behav Med. 2007;30:359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chariyeva Z, Golin CE, Earp JA, Maman S, Suchindran C, Zimmer C. The role of self-efficacy and motivation to explain the effect of motivational interviewing time on changes in risky sexual behavior among people living with HIV: a mediation analysis. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:813–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preacher KJ. Advances in mediation analysis: a survey and synthesis of new developments. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:825–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VanderWeele TJ, Vansteelandt S. Mediation Analysis with Multiple Mediators. Epidemiol. Method 2014;2:95–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imai K, Keele L, Yamamoto T. Identification, Inference and Sensitivity Analysis for Causal Mediation Effects. Stat Sci. 2010;25:51–71. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muthén B Applications of causally defined direct and indirect effects in mediation analysis using SEM in Mplus. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1:173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tolliver BK, Anton RF. Assessment and treatment of mood disorders in the context of substance abuse. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2015; 17(2): 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chitsaz E, Meyer JP, Krishnan A, Springer SA, Marcus R, Zaller N, et al. Contribution of substance use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes and antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected persons entering jail. AIDS Behav. 2013; 17 Suppl 2:S118–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Kidder DP. Associations between substance use, sexual risk taking and HIV treatment adherence among homeless people living with HIV. AIDS care. 2009;21(6):692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol Bull. 1991; 110:86–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKirnan DJ, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Sex, drugs and escape: a psychological model of HIV-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS Care. 1996;8:655–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmer NB, Salcedo J, Miller AL, Winiarski M, Arno P. Psychiatric and social barriers to HIV medication adherence in a triply diagnosed methadone population. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17(12):635–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Durvasula R, Miller TR. Substance abuse treatment in persons with HIV/AIDS: challenges in managing triple diagnosis. Behav Med. 2014;40:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, London AS, Caetano R, Burnam MA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, Maisto SA, Crystal S, Day N, et al. A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1190–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pence BW, Miller WC, Gaynes BN, Eron JJ. Psychiatric illness and virologic response in patients initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Kolodziej ME, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, Daley DC, et al. A randomized trial of integrated group therapy versus group drug counseling for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McDonell MG, Srebnik D, Angelo F, McPherson S, Lowe JM, Sugar A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of contingency management for stimulant use in community mental health patients with serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malta M, Strathdee SA, Magnanini MMF, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review. Addiction. 2008;103:1242–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osher F, Steadman HJ, Barr H. A Best Practice Approach to Community Reentry From Jails for Inmates With Co-Occurring Disorders: The APIC Model. Crime & Delinquency. 2003;49:79–96. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Babowitch JD, Sheinfil AZ, Woolf-King SE, Vanable PA, Sweeney SM. Association of Depressive Symptoms with Lapses in Antiretroviral Medication Adherence Among People Living with HIV: A Test of an Indirect Pathway. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:3166–3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25:462–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Algur Y, Elliott JC, Aharonovich E. A Cross-Sectional Study of Depressive Symptoms and Risky Alcohol Use Behaviors Among HIV Primary Care Patients in New York City. 2018;22:1423–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sullivan LE, Saitz R, Cheng DM, Libman H, Nunes D, Samet JH. The impact of alcohol use on depressive symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Addiction. 2008;103:1461–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bryant VE, Whitehead NE, Burrell LE, Dotson VM, Cook RL, Malloy P, et al. Depression and Apathy Among People Living with HIV: Implications for Treatment of HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:1430–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:180–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]