Abstract

Proline-rich proteins (PRPs) play multiple physiological and biochemical roles in plant growth and stress response. In this study, we reported that the knockout of OsPRP1 induced cold sensitivity in rice. Mutant plants were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 technology to investigate the role of OsPRP1 in cold stress and 26 mutant plants were obtained in T0 generation with the mutation rate of 85% including 15% bi-allelic, 53.3% homozygous, and 16.7% heterozygous and 16 T-DNA-free lines in T1 generation. The conserved amino acid sequence was changed and the expression level of OsPRP1 was reduced in mutant plants. The OsPRP1 mutant plants displayed more sensitivity to cold stress and showed low survival rate with decreased root biomass than wild-type (WT) and homozygous mutant line with large fragment deletion was more sensitive to low temperature. Mutant lines accumulated less antioxidant enzyme activity and lower levels of proline, chlorophyll, abscisic acid (ABA), and ascorbic acid (AsA) content relative to WT under low-temperature stress. The changes of antioxidant enzymes were examined in the leaves and roots with exogenous salicylic acid (SA) treatment which resulted in increased activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT) under cold stress, while enzyme antioxidant activity was lower in untreated seedlings which showed that exogenous SA pretreatment could alleviate the low-temperature stress in rice. Furthermore, the expression of three genes encoding antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD4, POX1, and OsCAT3) was significantly down-regulated in the mutant lines as compared to WT. These results suggested that OsPRP1 enhances cold tolerance by modulating antioxidants and maintaining cross talk through signaling pathways. Therefore, OsPRP1 gene could be exploited for improving cold tolerance in rice and CRISPR/Cas9 technology is helpful to study the function of a gene by analyzing the phenotypes of knockout mutants generated.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-019-1787-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cold Stress, CRISPR/Cas9, Mutation, Rice, OsPRP1, Proline

Introduction

Cold stress has an adverse effect on plant development, growth, and yield which leads to physiological and structural alterations such as osmotic pressure imbalance, ice crystal formation, and elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) resulted in deterioration of membrane integrity, impairment of cell viability, and, finally, leads to cell death (Kanneganti and Gupta 2008; Kim et al. 2009; Miller et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2014). Various stress-inducible proteins are responsible to enhance the plant tolerance to low-temperature stress. Proline concentration is important in the osmotic adjustment in plants and compatible solute responsible to maintain membrane integrity to avoid cellular dehydration and serves as an osmoprotectant under cold stress (Siripornadulsil et al. 2002). Proline has been related to soluble sugars’ content and cold tolerance in mutant plants which ultimately contribute to osmotic adjustment (Kandpal and Rao 1985). Antioxidant enzyme activity increased under cold stress to scavenge ROS and protect rice plants against oxidative damage (Sato et al. 2011). Physiological activities of antioxidant enzymes such as peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) can also be used to evaluate cold tolerance and the higher activities of antioxidant enzymes indicate relatively improved cold tolerance in rice by maintaining the functions of other associated genes during cold stress (Huang et al. 2009; Kim and Tai 2011; Bonnecarrère et al. 2011; Sato et al. 2011; Xie et al. 2012). Proline-rich proteins (PRPs) have been reported with roles involved in cold tolerance in rice. PRPs are the structural cell wall proteins identified in response to stress (Showalter 1993; Tierney et al. 1988) and have been shown to be expressed in many plant species. The precise function of PRP genes is unknown, but their expression is associated with biotic and abiotic stresses and may have vital roles in normal development of the plant, integrity of cell wall, and maintenance of organs (Nicholas et al. 1993; Akiyama and Pillai 2003). PRPs have multiple functions and implicated in the integrity of cell wall and structural maintenance of organs and have been identified in several plants including rice, wheat, and maize (Brisson et al. 1994; Fowler et al. 1999; Wu et al. 2003). The OsPRP1 is mainly expressed in rice roots, spikelets, and shoots encoding a protein consisting of 224 amino acids with proline content and most likely a cell wall protein, accounting for 14.29%, and consists of a 21-amino acid signal peptide, an N-terminal domain, and a C-terminal domain. There are four copies of OsPRP1 in the rice genome, which are located on the 20 kb DNA fragment on chromosome 10 (Wu et al. 2003).

The research on the problem of low-temperature chilling injury in rice can help to increase the planting area, economic benefits and help to ensure quality of rice. With the development of some new molecular biology techniques such as CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regulatory interspersed short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated proteins), a lot of achievements have been made in plants and animals (Gaj et al. 2013; Gupta et al. 2018). CRISPR/Cas9 technology is widely used to study the gene function and regarded as the third-generation genome editing tool established after ZFN (zinc-finger nucleases) and TALEN (transcription activator-like effector nucleases), based on gRNA (guided RNA)-engineered nucleases, which is most applicable due to their simplicity, efficiency, and versatility (Qi et al. 2016; Jung et al. 2018). In recent years, CRISPR/Cas9 technology has also made remarkable achievements in the study of rice gene function, and has been widely used in human cells, mice, zebrafish, yeast, fruit flies, nematodes, tobacco, and Arabidopsis thaliana (Feng et al. 2013; Jiang et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2015a, b; Bortesi and Fischer 2015). CRISPR/Cas9 technology is frequently used in rice crop for improving several agronomic traits by targeted mutations in single or multiple major genes (Zhou et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2015; Ikeda et al. 2015; Li et al. 2016; Osakabe et al. 2016; Sun et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2016; Han et al. 2018). To improve the efficiency of animal and plant gene editing, the researchers developed engineered endonuclease (EEN), which produces DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) at the target site and repair pathway enables targeted editing of the genome (Chen et al. 2017). DSBs produced after DNA damage can activate the intrinsic repair mechanism of non-homologous ending-joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR) (Zheng et al. 2016).

In this work, we undertook the preliminary approach to study the role of OsPRP1 in cold tolerance and growing mutant plants in the presence and absence of cold stress. The OsPRP1 gene was edited in India rice variety using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique and mutant plants were evaluated under cold stress. Changes in antioxidant enzyme activities were analyzed to gain insight into the mechanism underlying cold stress in rice. We found that the OsPRP1 gene is responsible for cold tolerance in rice. Mutant plants were susceptible to cold stress, while wild-type plants showed tolerance. This study provides some insights into the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying the rice response to low-temperature stress.

Materials and methods

Test materials

In this study, indica rice variety GXU2-44 was used for genetic transformation and seeds were collected from the Rice Research Institute of Guangxi University. The wild-type and transgenic material was planted at the Guangxi University experimental area. In this study, the promoters gRNA-U6a, gRNA-U6b, and pYLCRISPR/Cas9 vector were provided by Professor Liu Yaoguang’s lab, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China. The experimental reagents were included pYL-U3/U6a-b-gRNAs, KOD-Plus, T4 DNA ligase, BasI-HF, kanamycin, ampicillin, MluI, Plasmid Mini Kit, and PCR Purification Kit. The primers used in the experiment were synthesized by Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI).

gRNA target selection and synthesis of oligonucleotide strands

Two target sites were designed in the second exon according to the OsPRP1 sequence provided by the Rice Data website (http://www.ricedata.cn/gene/index.htm). The online software CRISPR-GE (http://skl.scau.edu.cn/home/) was used to select the two targets with high efficiency. Both targets were 20 bp long and were followed by the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) CGG and GGG respectively. The target specificity of designed gRNA sequences was checked using NCBI against the rice genome (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) including PAM and gRNA efficiency was predicted on the base of nucleotide sequence and it was confirmed that U6 terminator was absent and cumulative p value score was high for both targets for high efficiency. Cas-OFFinder (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/) analysis and rice genome BLAST analysis were validated. The structure of gRNA (Additional file 2, Fig. S1) was developed using online tool CRISPR-P (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/cgi-bin/CRISPR2/CRISPR). The sequences of Target1 and Target2 are given in (Additional file 3). The physico–chemical properties that can be deduced from a protein sequence were predicted using online protein identification and analysis tool on the ExPASy Server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) (Additional file 5). The embedded view of plasmids (pYLsgRNA-OsU6a and pYLsgRNA-OsU6b) was developed using SnapGene Viewer version 4.0.

Construction of sgRNA expression cassette

The expression cassette of sgRNA for both target sites was constructed by overlapping PCR and two pairs of primers were used in each reaction in which 2–5 ng of pYLgRNA-OsU6a and pYLgRNA-OsU6b were used as templates (Additional file 1, Fig. S1, S2). For first PCR reaction 0.6 μl of U-F and gR-R, 0.3 μl of U6aT1PRP1-1-R and gRTPRP1-1-F and in second PCR 0.6 μl of U-F and o.6 μl gR-R, and 0.3 μl of U6bT1PRP1-2-R and gRTPRP-2-F were used, respectively. The PCR thermocycling profiles obtained with an initial denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 25 cycles of 10 s at 94 °C, 15 s at 58 °C annealing temperature, and 20 s at 68 °C. The second-step PCR was performed for reaction 1 and reaction 2, respectively, for the amplification of restriction enzyme cutting site. Both targets were purified using TaKaRA MiniBest DNA Fragment Purification Kit Ver 4.0. The sgRNA were constructed according to the previous report (Liang et al. 2016). All mentioned primers are given in Additional file 3.

Cloning of sgRNA expression cassette

The 20 μl restriction–ligation reactions were set up for cloning with 60 ng of pYL CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid, sgRNA-OsU6a, OsU6b, 2 μl of expression cassette mixture, 10 × CutSmart buffer 4 μl, 10 mmol/L ATP 4 μl, 10 U BsaI-HF 0.6 μl, 35 U T4 DNA ligase 0.4 μl, and ddH2O 7 μl were enzymatically ligated and reactions were incubated for 15 cycles (5 min at 37 °C, 5 min at 10 °C, 5 min at 20 °C, and 5 min at 37 °C) (Ma et al. 2015b). The ligation product was transformed into Escherichia coli (DH5α) by heat shock method, and the bacterial solution was applied to an LB plate containing 50 ug/mL kanamycin for about 12 h. Single colony was picked that grows on the plate and PCR was performed using the bacterial solution as a template and the primer combinations PB-L and PB-R. The plasmid of the positive strain was extracted, and PCR was carried out using the above primers. The plasmid was sent to BGI for sequencing. The confirmed positive plasmid was transferred to Agrobacterium EHA105 (Figs. 1, 2).

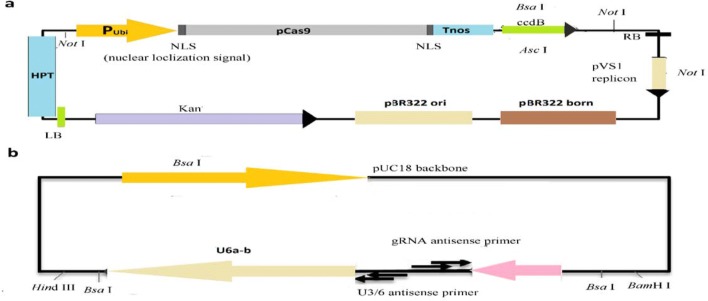

Fig. 1.

a Maps of pYLCRISPR/Cas9-MT(I) (~ 16.5 kb) and b pYL-U6a-b-gRNA (~ 3 kb) vectors

Fig. 2.

Target selections for vector construction. a Location of two targets (Target1 and Target2) and RT-qPCR primers (PRP1-F and PRP1-R) in PRP1 gene, PAM sequence in green, while target regions are shown in black letters with red background and first exon on left and second exon on right side are shown in black region; b linking sequence of two expression cassettes U6a-driven Target1 and U6b-driven Target2 on pYLCRISPR/Cas9 vector; c PRP1 gene sequence; yellow sequences represent the upstream and downstream primers of PRP1 partial gene sequence; blue sequences represent the PRP1 gene target site sequence and position. d detection of expression cassettes after transformation of DH5α; M: DL2000 DNA marker; 1–17: PCR amplification with 1144 bp amplified length of U6a and U6b expression cassette assembly

Cloning and identification of sgRNA expression cassette into pYL CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector

Restriction–ligation reactions of 20 μl were set up with 60 ng of pYL CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid, sgRNA-OsU6a, OsU6b, 10 ng of expression cassette mixture, 10 × CutSmart buffer, 10 mmol/L ATP, 10 U BsaI-HF, and 35 U T4 DNA ligase were enzymatically ligated and reactions were incubated for 15 cycles (5 min at 37 °C, 5 min at 10 °C, 5 min at 20 °C 5 min, and 5 min at 37 °C). The constructed pYLCRISPR/Cas9 vector with two sgRNA targets was confirmed to check the accuracy using U6am and U6bm primers and results were analyzed to assure that both target sequences were consistent with the designed target sequences (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

a Schematic diagram of sgRNA assembly and CRISPR/Cas9-gRNA. T-DNA of two targets assembled into pYLCRISPR/Cas9 vector. b Identification of pYLCRISPR/Cas9-PRP1-gRNA digested plasmid with the Asc I. M: DNA Marker 1 kB; 1: pYLCRISPR/Cas9-PRP1-gRNA

Preparation of Agrobacterium competent cells

The Agrobacterium competent cells were prepared by the procedure given as follows: 25 μl of Agrobacterium liquid was inoculated into 5 ml of YEP/Str+ liquid medium (containing streptomycin 50 μg m/l) and was incubated overnight at 28 °C and 230 RPM, and 1 mL of fresh bacterial solution was inoculated into 200 mL of YEP/Str+ liquid medium, and again incubated at 28 °C and 230 RPM. The sample was centrifuged at 4 °C for 4000 RPM for 10 min and supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in 20 ml freshly prepared HEPES (1 mmol/l, pH 7.0). After washing three times, the sample was again resuspended with 10% glycerol in 8 ml ice bath and was finally dispensed it into a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube and 100 μl was added in each tube and treated with liquid nitrogen for quick freezing and stored at − 80 °C for further use.

Conversion and detection of ligated products

10 μl of plasmid was added to the competent cell (DH5α) and culture medium was spread evenly on LB medium-containing 5 μg/ml Kan, and incubated at 37 °C. After 16 h, the single colony was carefully picked in Eppendorf tubes containing 2 mL of 5 μg/mL kanamycin and moved to the 1 mL of LB culture medium. LB medium was cultured for 4 h at 37 °C and 200 RPM and transformation was performed. PCR was performed for the bacterial liquid to amplify respective genes by using PB-L and PB-R primers for testing positive clone (Additional file 3). The colonies with amplification of 1144 bp were taken and sent to Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) for sequencing analysis. At the same time, bacterial liquid-containing positive colonies were incubated for 12 h and plasmids were extracted.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation

The plasmid DNA of the constructed CRISPR/Cas9 expression vector was transferred into Agrobacterium strain DH5α by electric shock. Competent cells were liquefied on ice during electroporation and 2 μL of purified plasmid DNA was added to competent cells and added to a pre-cooled electric shock cup, and an Eppendorf Eporator was used at 12,500 V/cm. 800 μl of antibiotic-free Yeast Extract and Peptone (YEP) medium was quickly added after the electric shock and transferred to a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube and shaken at 28 °C for 230 RPM, and after 2 h, 100 μL of bacterial solution was applied and coated. It was placed on YEP/K+ plate (containing kanamycin 50 μg/ml) and cultured in an incubator at 28 °C for 24–48 h. Transformation of rice calli was performed according to Hiei et al. (1994) and calli were transferred to regeneration media to obtain green plants.

Identification of Cas9-PRP1-positive colonies

Primer SP-L and SP-R (Additional file 3) were used for the bacterial liquid PCR and positive colonies were screened for sequencing analysis. The target sequence was successfully ligated to the vector. The correct recombinant plasmids of the positive colonies were selected and submitted to BGI for sequencing analysis. The confirmation of the exactness of the sequence was done by comparison.

Genotyping of T0 generation

The genomic DNA of T0 generation was extracted with the established CTAB method (Xu et al. 2005). The site-specific primers PRP1T1-F and PRP1T1-R and PRP1T2-F and PRP1T2-R (Additional file 3) were designed to conduct PCR amplification on the two target sites. The product confirming the target fragment size was sent to the BGI for sequencing, and the sequencing result was decoded and analyzed using online analysis tool DSDecode (http://skl.scau.edu.cn/dsdecode/) (Ma et al. 2015a). The multiple-nucleotide sequence alignment was performed using Clustal Omerga online tool (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The amplified nucleotide sequences of were converted to amino acid sequence using online ExPASy tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/). Multiple amino acid sequence alignment was performed using online TCOFFEE tool (http://tcoffee.crg.cat/). Bioedit v.7.0.5 software was used to visualize the sequencing results of wild and mutant lines to get clear peaks. Amino acid sequences contain information of transcription and translation and contained various important information such as molecular weight, instability index, grand average of hydropathicities (GRAVY), and aliphatic index. The physiochemical properties of amino acid sequence and protein modeling were performed by translating the targeted nucleotide sequences of WT and mutant lines using online ExPASy protparam online server (https://web.expasy.org/translate/) and the best open reading frame (ORF) sequences were selected to predict the secondary structure and disorder of protein using PSI-blast-based secondary structure PREDiction (PSIPRED) online server (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/).

Screening of T-DNA-free T1 generation

The DNA of T1 CRISPR mutants was extracted using the CTAB method. The T-DNA free lines were screened by amplifying the genomic DNA of T1 generation using Cas9 gene-specific primers (Cas9-F/Cas9-R) (Additional file 3). The T-DNA free lines were selected for sequencing of the target regions.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from the fresh leaves of both the cold-treated and control plants of wild-type and mutant lines. Total RNA was extracted using TaKaRa MiniBEST Plant RNA Extraction Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of RNA was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis and concentration (ng/μL) was measured using TIANGEN TGem spectrophotometer Plus. All samples of RNA were treated with RNAase-free DNAase Kit (Takara). cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript™ first-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Expression analysis of PRP1 and antioxidant genes

The rice actin gene (actin-7, LOC4349863) was used as a control and specific amplification primers were designed according to the gene sequence (Additional file 3). RT-qPCR was performed in a total volume of 10 μl containing 0.3 μl of reverse-transcribed product, 0.08 μM gene-specific primers, and 5.0 μl of ChamQ™ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme). PCR amplification and fluorescence detection were performed using a Real-Time (Roche) LC480. PCR cycles were programmed as initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 58 °C for 10 s, and extension at 72 °C for 10 s with 45 cycles. Specific primers (PRP1-F and PRP1-R) for OsPRP1 and (SODF/SODR, PODF/PODR, and CATF/CATR) were designed for antioxidant genes using online GenScript website tool (https://www.genscript.com/) (Additional file 3). The relative expression level was calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method and three biological replicates per sample were used.

Phenotyping of morphological traits

The survival rate of wild and mutant plants was calculated from total ten plants of each line under normal (25 °C) and low temperature (5 °C). The unstressed and stressed seedlings were randomly selected to measure the fresh shoot weight, dry shoot weight, fresh root weight, and dry root weight. Dry weight was determined by drying samples in an aerated oven at 70 °C for 72 h.

Biochemical analysis of WT and mutant plants

WT and mutant plants seeds were planted in an experimental area of Guangxi University in the same season. The plants were subjected to cold stress in growth chamber and after 25 days of germination. The proline content was measured according to (Bates et al. 1973) and for the measurement of endogenous ABA levels the 0.2 g of rice seedlings were homogenized in 1 mL of distilled water and kept on shaker for overnight at 4 °C and homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was used for ABA assay according to Quarrie et al. (1988) and Ren et al. (2007). Total chlorophyll contents were measured from the rice leaves according to Arnon (1949) and AsA was measured by following the Hewitt and Dickes (1961) and Forcat et al. (2008). Graphs for each character were developed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.0, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

Antioxidant enzyme assays with exogenous SA

Rice seedlings were cultivated in a chamber (25–27 °C) to the second leaf, and after that, the seedlings were kept at low-temperature treatment for 5 days at 6 °C and 0.5 mmol/L SA was applied equally to the plants and each treatment was repeated three times. The controlled and low-temperature treated seedlings were crushed into a powder in a mortar with pestle with liquid nitrogen. The crude enzyme of the powder was extracted in 50 mM chilled sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and 1% (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) at 4 °C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000g at 4 °C for 15 min. In the supernatant, SOD, CAT, and POD enzyme activity was immediately determined. The SOD enzyme activity was estimated according to Aebi (1984) and Zhu et al. (2004). Absorbance was recorded at 560 nm with a UV–visible spectrophotometer. Specific enzyme activity was expressed as units per milligram of protein. The CAT enzyme activity was estimated according to Aebi (1984). The POD enzyme activity was estimated according to Beffa et al. (1990). Absorbance was measured at 460 nm with a UV–visible spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 Statistical Software Program. The graphs were constructed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.0, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Detection of transformed plants in T0 generation

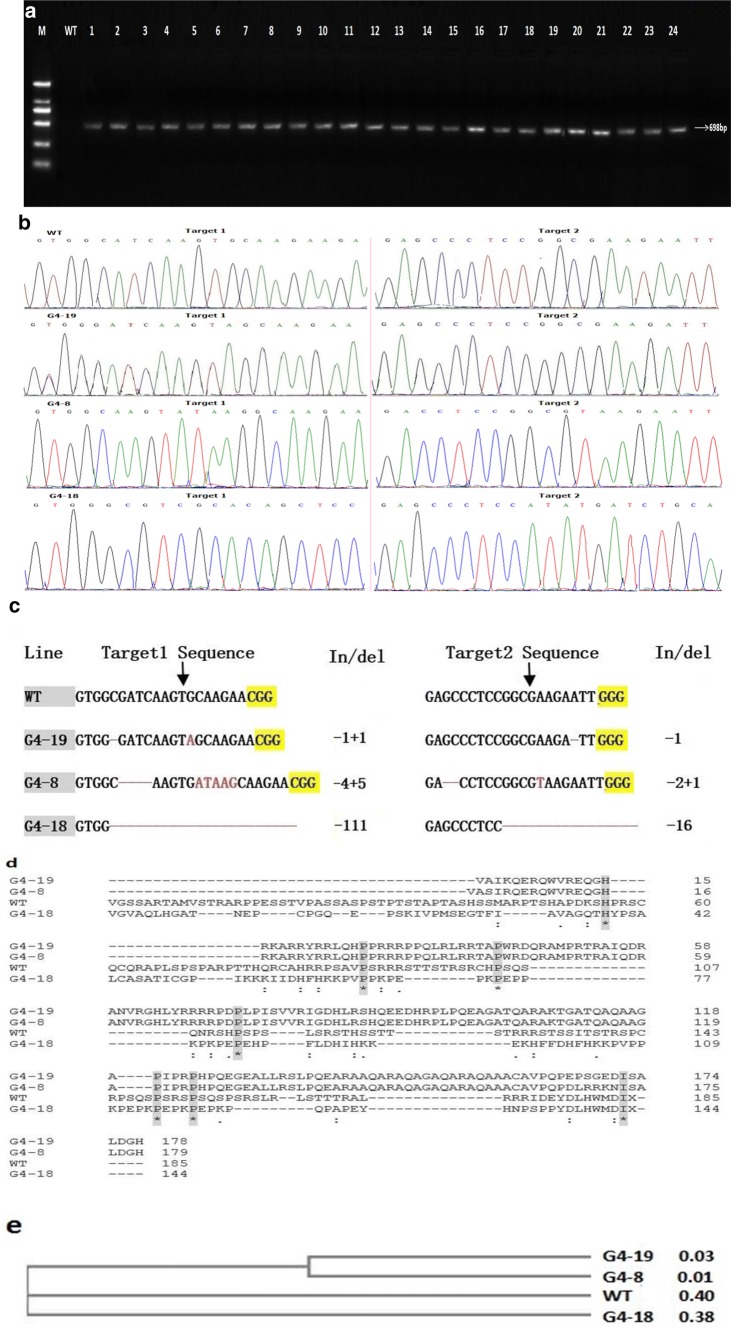

Total 30 independent transgenic plants were obtained for both target sites and the T0 generation sequencing results showed that were 26 mutants found in Target1 with the mutation rate of 86.7%; among them, 19 plants with homozygous mutations, 4 with heterozygous mutations, and 3 with bi-allelic mutations. The total 25 mutant plants in Target2 have mutation rate of 83.3% with 13 homozygous, 6 heterozygous, and 6 with bi-allelic mutations. The plants with homozygous mutations were more than heterozygous mutants in both targets (Table 1). The sequencing results of the amplified products showed that the G4-19 showed single base insertion and deletion in Target1 and single base deletion in Target2. G4-8 showed 4 base deletion and 5 base insertion in Target1, while two bases deletion in target 2 with the addition of 1 base. G4-18 mutant lines showed large fragment deletion of 111 bp in Target1 and 16 bp deletion in Target2 (Fig. 4c). The amino acid sequence alignment clearly showed the deletions and insertions in the specific regions (Additional file 2, Fig. S2). Amino acid alignment revealed that the translation in mutant lines was terminated prematurely (Fig. 4d) and phylogenetic tree showed that G4-19 was more divergent to WT (Fig. 4e).

Table 1.

Mutation frequency of T0 generation

| Target site | Mutation type | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi-allelic | Homozygous | Heterozygous | Wild | ||

| Target1 | |||||

| Number of plants | 3.0 | 19.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 30.0 |

| Mutation rate (%) | 10.0 | 63.3 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 100.0 |

| Target2 | |||||

| Number of plants | 6.0 | 13.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 30.0 |

| Mutation rate (%) | 20.0 | 43.3 | 20.0 | 16.7 | 100.0 |

Fig. 4.

Analysis of positive mutant lines. a Detection of T0-positive mutant strains; M: DNA marker DL2000; WT: Control; 1–24 (T0 transgenic strains). b Sequencing peak map of wild and mutant lines for Target1 and Target2, respectively. c DNA sequence alignment of target regions for wild-type and the three mutant lines in T 0 generation. Deletions and insertions are indicated by red dashes and letters, while yellow highlighted is PAM sequence. The numbers on the right side show the sizes of the indels, with “−” and “+” indicating deletion and insertion of the nucleotides involved, respectively. d Amino acid sequence alignment for wild type and three mutant lines in T0 generation. Dark gray frames with an asterisk (*) symbols indicate the similar sequences. Each of the mutated sequence codes for the disrupted protein. e Neighbor-joining phylogeny analysis. G4-19 and G4-8 mutant lines showed more diversity than other G4-18

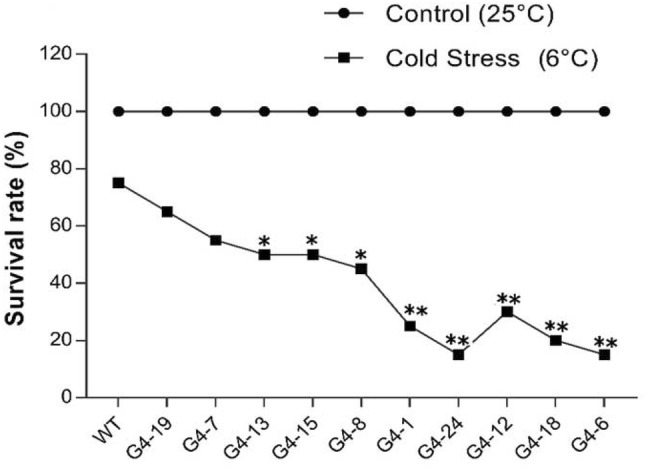

Survival rate of T0 generation under cold stress

To evaluate the role of PRP1 expression effect on cold tolerance, the plants were subjected to cold stress to examine the survival rate of the WT and mutant lines. Seedlings were grown in a growth chamber, and after 2 weeks, seedlings of WT and mutant lines were exposed to a temperature of 6 °C for 4 days under 16 h light and 8 h dark conditions. The plants were also grown in a growth chamber at 25 °C under normal light and dark conditions as a control, after which the survival rates were calculated. Plants of mutant lines G4-24, G4-6, and G4-18 with large fragment deletion showed 15, 15, and 20% survival rate, while WT showed 75% survival rate (Fig. 5). This decreased survival rate demonstrates that mutations of OsPRP1 regulate the cold tolerance in rice and plays significance role in cold stress tolerance.

Fig. 5.

Survival rate of WT and mutant plants under normal and low-temperature stress. Data are the mean of five independent values (p ≤ 0.05)

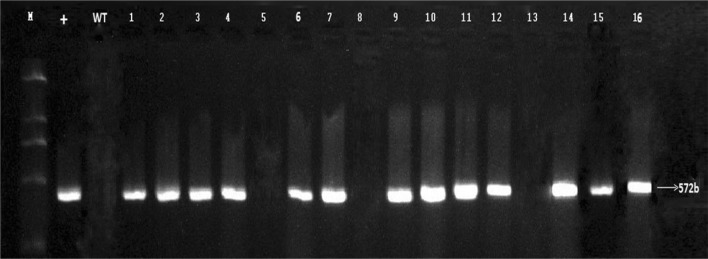

T-DNA-free mutants in T1 generation and physico-chemical characterization of amino acid sequences

Homozygous mutants of T0 and T1 were planted and 85 plants were screened to analyze their genetic transformation pattern. T-DNA-free mutants were selected using cas9-specific detection primers cas9-F and Cas9-R (Additional file 3). The results showed that 62 mutants were amplified to Cas9 vector sequence with 572 bp fragment and 17 strains were not amplified to the corresponding fragment and, thus, termed as T-DNA-free plants (Fig. 6). T-DNA-free strain appeared with a frequency of 20%. To characterize a specific protein, the physico-chemical composition is very important, and the results showed that the amino acid composition was different among WT and mutant lines. The total number of amino acids was different in WT and mutant lines. WT and mutant plants showed different theoretical pI, aliphatic index, GRAVY, instability index, total number of positive charges (Arg + Lys), and negatively charged (Asp + Glu) residues (Additional file 5). WT and mutant plants also showed difference in secondary structure and disorder confidence level of protein. The secondary structure of the amino acid sequence of WT and mutant lines was elaborated, and no disorder protein-binding sites were discovered in WT structure, while all mutant lines showed disorder protein binding (Additional file 6, Fig. S1).

Fig. 6.

Detection of T1-positive lines (1–16); M: DL2000 DNA marker; +: control of mutant positive strains; WT: negative control of unmarked gene

The survival rate of T-DNA-free mutant plants

The survival rate of rice seedlings was measured after 25 days of germination. WT and all mutant plants showed no difference in phenotype and survival rate under normal temperature, while the cold-treated WT and transgenic plants showed significant difference and WT plants showed 70% survival rate under cold stress, whereas mutant plants showed lower survival rate and homozygous mutant line G4-18-3 with large fragment deletion showed 60% lower survival rate (10%) than WT, while G4-1-3, G4-1-7, G4-6-6, G4-6-7, G4-7-3, G4-7-5, G4-8-4, G4-8-6, G4-12-1, G4-12-2, G4-13-1, G4-13-3, G4-15-2, G4-15-5, G4-18-6, G4-19-3, G4-19-5, G4-24-3, and G4-24-6 showed survival rate of 25%, 30%, 15%, 20%, 40%, 50%, 20%, 35%, 25%, 15%, 35%, 40%, 35%, 15%, 15%, 50%, 55%, 20%, and 25%, respectively. Homozygous mutant line G4-19-5 with single base deletion showed maximum survival rate (55%) than other mutant lines. The survival rate of the WT plants was more than 70% under cold stress, whereas survival rate of the mutant lines was much lower, and plants were turned to yellow (Fig. 7b). All mutant lines showed less survival rate than WT, which confirmed that OsPRP1 regulates the cold tolerance in rice and result showed that mutations were consistent with the T0 generation, indicating that the T1 generation has stabilized (Fig. 7a).

Fig. 7.

Survival rate of WT and T-DNA-free mutant plants under normal and controlled conditions (a). Appearance of WT and CRISPR mutant rice seedlings under cold stress (b). Data are the mean of three independent replications (p ≤ 0.05)

PRP1 and antioxidant gene expression level

Rice actin gene was used in RT-qPCR as a reference to normalize PRP1 expression between samples. Results showed that mutation is highly correlated with expression level of PRP1. PRP1 expression level in WT was relatively higher compared to those of other mutant T1 Lines. The mutant line G4-18 of T0 generation showed minimum expression level than WT and other mutant lines, while mutant G4-19 of T0 generation showed maximum expression level among T0 mutants but lower than WT. Results clearly revealed that the expression level was lower in mutant plants and the mutant with large mutations showed lower expression level than wild-type and single target mutant line (Fig. 8a). In consistent with the results of antioxidant enzyme assays, the expression level of the antioxidant genes was significantly lower in transgenic rice lines under stress conditions (Fig. 8b–d). The expression level of PRP1 was increased under cold stress with the increase in time (Fig. 8e).

Fig. 8.

PRP1 and antioxidant gene expression level of WT and T0 mutant plants by RT-qPCR analysis after 25 days of germination. a Expression level of PRP1 in WT showed maximum expression, while mutant plants (G4-19, G4-8, and G4-18) showed relatively low expression level than WT. Expression level of b SOD4, c POX1, and d OsCAT3 in WT and mutant lines. e Expression level of OsPRP1 under cold stress in different time intervals. Data are means ± SD (n = 3), (p ≤ 0.05)

Changes in root and shoot biomass under cold stress

The nutrients are absorbed by the roots, so the root structure can affect the plant growth indirectly. Shoot and root growth of rice seedlings grown at 6 °C was substantially retarded compared to seedlings grown at 25 °C. The results showed that, after cold stress treatment for 5 days, the shoot FW, shoot DW, root FW, and root dry weight showed obvious change and the mutant line G4-18-3 showed minimum root FW (8.68 mg) and root DW (1.04 mg) under cold stress, while mutant lines G4-19-5 and G4-8-6 showed biomass than WT and other mutant lines (Fig. 9). The biomass of the root and shoot of the plant was higher under normal temperature (Additional file 6, Fig. S2). The vigorous root system and more healthy shoots make rice plant more tolerant to cold stress.

Fig. 9.

Root and shoot DW and FW under cold stress of WT and homozygous mutant lines: a root fresh weight (mg), b root dry weight (mg), c shoot fresh weight (mg), and d shoot dry weight (mg). Data are means ± SD of three values (p ≤ 0.05)

Effect of exogenous SA on antioxidant enzyme activity under cold stress

Compared with normal, the CAT activity was higher under the cold treatment with SA application than normal controlled treatment, as shown in (Fig. 10a–f). At 5 °C, the CAT activity under controlled treatment of the mutant line G4-18-3 showed minimum CAT activity, while G4-19-5 showed maximum CAT activity than other mutant plants. The CAT activity was higher in leaves and roots of WT than all mutant plants. Compared with normal, the CAT activity was higher with exogenous SA treatment under the cold treatment. Increased CAT activity contributed to cold tolerance of rice seedlings under cold stress. SOD and POD activity of mutant and WT plants by SA foliar application during the whole period of low-temperature stress showed significantly higher enzyme activity than the low temperature under controlled conditions. Cold stress also induces the evident accumulation of free radicals and causes an oxidative burst in plant cells. The antioxidant enzyme activity is simultaneously activated to eliminate the ROS. Results showed a significant increase in SOD, CAT, and POD activities with SA application (Fig. 10a–f). Overall, increased activity in all the antioxidant enzymes was induced in all the genotypes with SA treatment as compared with the controlled seedlings. Antioxidant enzyme activity, such as SOD, CAT, and POD, increased significantly in both genotype groups under stress. Cold tolerance or genotype sensitivity was correlated with antioxidant enzyme responses. The mutant plant G4-18 showed less cold tolerance and SOD activity under controlled conditions than other mutant and WT plants (Fig. 10e, f). The CAT and POD activity of WT seedlings approximately had a higher rate increase than mutant line seedlings compared with control seedlings (Fig. 10a–d).

Fig. 10.

Specific antioxidant enzyme activities in roots and shoots under low temperature (6 °C) of rice seedlings with exogenous SA treatment and controlled conditions. The antioxidant activity was measured in U/mg FW/min; a CAT activity in leaves, b CAT activity in roots, c POD activity in leaves, d POD activity in roots, e SOD activity in leaves, and f SOD activity in roots. Values are means ± SD at p ≤ 0.05 significance level

Physio-chemical changes under low-temperature stress

Chlorophyll content, ABA content, AsA content, and proline content were measured in T1-screened homozygous mutant plants and WT. After chilling stress, chlorophyll content of rice seedlings was decreased and mutant plants showed significant difference with WT. Mutant lines and WT showed the non-significant difference in chlorophyll content under normal temperature, while significant differences in chlorophyll content were found under low-temperature treatment. Compared with the WT rice, the mutant lines G4-19-5, G4-8-6, and G4-18-3 showed reduction in chlorophyll content of 1.68 mg/g, 2.08 mg/g, and 2.53 mg/g respectively under cold stress (Fig. 11b). All three mutant lines showed low chlorophyll content than WT, while homozygous mutant line G-18-3 showed minimum chlorophyll content under cold stress (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Physio-chemical response of WT and transgenic plants. Plants were grown under normal temperature (25–30 °C) for 20 days and then exposed to low-temperature stress (6 °C). Data are means ± SD (n = 5) and significance level at p ≤ 0.05

WT and mutant lines showed no difference in ABA content under controlled temperature (25 °C) (Fig. 11c), while ABA content was decreased under cold stress (6 °C) in WT and mutant plants. Mutant plants showed significant difference in ABA content under low temperature and G4-18-3 showed low level of ABA than WT and other mutant lines. Proline content under low temperature was substantially increased as compared to seedlings grown at 25 °C (Fig. 11a). WT and mutant plant showed a significant difference in proline content under low temperature and mutant line G4-18-3 showed low proline content than WT and other mutant lines (Fig. 11a). AsA contents were decreased after cold treatment and constant under controlled temperature (25 °C) (Fig. 11c). Mutant line G4-18-3 showed lower AA content than WT and other mutant lines under cold stress.

Discussion

With the rapid development of science and technology, the research has entered to the new era of big data and massive information on various species and the genome targeted editing technology. CRISPR/Cas9 has become simple, fast, versatile, and efficient tool that demonstrated strong performance in whole genome-wide gene knockout in plants. The results of this study indicate that the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology can successfully edit rice targeting DNA sequences with high efficiency and multiple mutations can be generated at the same target site, and base deletion or insertion occurs before the target site PAM. In addition, we also found that the different mutation in the same gene resulted in homozygous mutant plants exhibiting different phenotypes and genetic material developed often showed different mutation modes and provides rich genetic material for further research. The total mutation frequency was up to 90%, wherein PRP1 homozygous mutations were about 51%, which indicate that the CRISPR/Cas9 editing facilitates homozygous mutations in the T0 generation. The comparison of T0 and T1 generations showed that the mutation frequency of homozygotes was stably inherited regardless of whether T-DNA is present. The conserved amino acid sequence was totally changed in mutant plants and mutant plants showed divergence to WT in the amino acid sequence alignment. The amino acid composition was also totally changed in mutant plants (Additional file 5, Table S1). The structure and function of protein are changed with mutation in a single nucleotide of a gene and the residue location is affected if stereochemical nature of amino acid replaced with another amino acid. Selecting several indicators with excellent performance, and the identification results of the indicators are basically consistent as the final screening of low-temperature resistant plants and mutant lines with large differences in biochemical and enzymatic activities can be further explored. The amino acid composition and protein secondary structure were different among WT and mutant lines, and mutant lines showed disordered protein-binding sites. To detect the conformational changes within the target protein, the secondary structural elements are helpful (Roy et al. 2015).

The CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutants were analyzed under low-temperature stress with WT and the growth performance under stress conditions was used to identify the cold tolerance function of PRP1 gene. The WT and PRP1 mutant plants were analyzed under cold stress (6 °C for 3 days), and phenotypic and physiological results showed that the mutant plants showed less tolerance to low-temperature stress and semi-quantitative expression analysis confirmed that rice PRP1 expression was down-regulated in mutant plants than WT. It is speculated that PRP1 may play a role in cold tolerance control network of cold-tolerant rice. The low-temperature injury is the largest abiotic disaster resulted in reduced yield and sometimes no harvest. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanism of rice cold damage and breeding new cold-tolerant rice varieties are the key to solving the impact of cold damage on rice production. RT-qPCR was used to analyze the expression pattern of OsPRP1 in WT and mutant lines according to the previous studies (Jang et al. 2016; Han et al. 2018). Our results showed that expression of a single gene can initiate a signaling network so to study the gene functions is an important key to improve the cold tolerance of plants by utilizing the favorable genes. In our study, the expression level of PRP1 was decreased in mutant plants. The survival rate of mutant plants was lower than wild type under low temperature and PRP1 mutants were very sensitive to low temperature, while, under normal temperature, WT and mutant plants showed 100% survival rate. Low temperature prevents the differentiation of plastids to mature organelles and gene expression is suppressed, particularly of genes involved in transcription and translation and chlorophyll biosynthesis.

The fresh and dry shoot and root weight of mutant plants and WT were decreased under cold stress (6 °C) conditions as compared with controlled conditions and mutant plants showed significant difference with WT, while there was no difference under normal temperature (25 °C). Mutant line G4-19-5 showed higher value of fresh and dry root weight among other mutant plants and G4-18-3 showed minimum, while WT showed higher fresh and dry shoot weight than mutant plants under normal and low temperature. Cold stress affects the seed germination and subsequent root system development during the early seedling stage and it directly affects the uptake and upward transport of nutrients and water (Aroca et al. 2001), biomass partitioning, and leaf and shoot growth (Engels 1994; Poire et al. 2010; Sakamoto and Suzuki 2015).

In this experiment, the SOD, POD, and CAT activity were selected as physiological indexes for low-temperature tolerance evaluation of rice seedlings. The enzymes reflected the integrity of cell membrane in rice (Alscher et al. 2002; Cook et al. 2004; Miller et al. 2010), and low-temperature tolerance showed a significant correlation between cold tolerance and enzyme activity, and believed that the rice seedlings showed increased enzyme activity rapidly under the low temperature of severe injury and showed obvious differences between different cold resistant varieties. The results of this experiment also show that the POD, SOD, and CAT activity of the mutant plant was significantly lower than the WT, indicating that PRP1 gene is responsible for the signaling of cold stress in rice and a hypothetical model was developed according to results (Additional file 4, Fig. S1). Evaluation of antioxidant enzyme activities could reveal the cold tolerance mechanism in plants and lower antioxidant activities indicate relatively decreased cold tolerance (Huang et al. 2009; Bonnecarrère et al. 2011). The mutant plants showed low level of proline content, AsA content, chlorophyll content, and ABA content, while the WT showed significant higher level of these compounds. Moreover, cold stress resulted in enhanced proline accumulation which is widely observed in rice plant under cold stress. Proline stabilizes the polyribosome, maintains the protein synthesis, and protects the denaturation of cellular enzymes (Kandpal and Rao 1985; Shah and Dubey 1997; Kim and Tai 2011) by maintaining the oxidative respiration and hydrophobic interactions with the surface residues of proteins (Venekamp 1989). AsA and ABA also played an important role in photosynthesis regulation and metabolic adaptation and scavenge ROS by cold stress to protect rice plants against oxidative damage (Kim and Tai 2011) and such antioxidants are crucial for plant defense (Noctor and Foyer 1998; Mittler 2002; Zhang et al. 2014). The results also showed that PRP1 knockout may enhance the cold stress by modulating gas-antioxidant machinery, and expression of genes that are involved in this pathway. SOD destroys radicals which are normally produced within the cells and which are toxic to biological systems and played role in detoxification of ROS by halophytes respond to stress at different levels and can be a model for increasing tolerance in crop plants (Modarresi et al. 2012). The genes related to POD in rice, such as OsAPX1 and OsAPX2, were induced after rice plants were exposed to low temperatures (Caverzan et al. 2012). The transgenic rice plants overexpressing a cytosolic Ascorbate peroxidase1 (APX1) gene (OsAPXa) which exhibited higher APX activity in spikelets than in WT plants, sustained higher levels of APX activity under cold stress, resulting in enhanced cold tolerance at the booting stage (Sato et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2012). The mutations in catalase3 (OsCAT3), in rice, resulted in an increase of H2O2 in the leaves, which consequently promoted Nitric oxide (NO) production via the activation of nitrate reductase. The removal of excess NO reduced cell death in both leaves and suspension cultures derived from noe1 plants, implicating NO as an important endogenous mediator of H2O2-induced leaf cell death (Lin et al. 2012). Here, we also analyzed the expression level of SOD-, POD-, and CAT-related genes (SOD4, POX1, and OsCAT3) in WT and mutant lines, and found that the expression level of these genes was significantly reduced in mutant plants. Collectively, our data suggest that these genes are important in mediating the response to leaf cell death in rice under cold stress.

The results showed that the WT with strong cold tolerance had higher levels of protective enzymes and proline content and antioxidant activity of low-temperature rice seedlings was positively correlated with the low-temperature resistance of the plants. The results obtained in this study by the combination of physiological and biochemical effects were correlated and regulated by the expression level of PRP1 gene. The morphological, physiological, and biochemical indicators and degree of low-temperature tolerance of mutant plants and WT were different, and finally, the stress tolerance was lower in mutant plants than WT as physiological and biochemical indicators were better in WT than mutant plants. The study showed that the genetic mutations are not only helpful to improve the plant characters, but it also helps to understand the mechanism underlying the biochemical behavior changes in cell of the plants.

Conclusion

The PRP1 mutants with different level of mutations were obtained which laid an important material basis for further evaluation of PRP1 gene function and signaling mechanism. CRISPR/Cas9 provides an important theoretical and practical significance and reference for the rapid creation of excellent rice mutant plants with important application value to elucidate gene function and is expected to provide a safe and efficient new way for rice germplasm resources innovation. The lower relative growth rate level, constitutive enzyme antioxidant activities, and total antioxidant capacity in the cold-induced mutant rice seedlings indicated that cold tolerant genotypes had a high free radical degradation content and strong physiological and molecular mechanism. These results collectively suggested that the knowledge of these parameters in responses to cold stress may be further applied as criteria to cold-tolerant screening in rice genotypes or other plant species.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Liu Yaoguang from South China Agricultural University, who provided us pYCRISPR/Cas9 and gRNA vectors (pYL-U6a-b-gRNAs). We would also like to thank Mr. Mohsin Niaz and Mr. Zhao Neng for the helpful discussion and invaluable comments to make this research meaningful.

Author contributions

GN and YH conceived, designed, and performed the experiments. BU was responsible for vector construction and wrote the paper. GN and BU were responsible for final data analysis and wrote the final draft. BQ and FL participated in the experimental design, result analysis, and field trials. RL visualized the project, supervised the methodology, given feedback on data presentation, and reviewed the final draft. All the authors have read the manuscript and approved the submission.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Technology Research and Development Program Guike, Guangxi (Guike AB16380066; Guike AB16380093).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank data library under accession numbers GenBank: KR029105 and KR029107 for the sgRNA intermediate plasmid and GenBank: KR029109 for the CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector.

References

- Aebi Hugo. Methods in Enzymology. 1984. [13] Catalase in vitro; pp. 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Pillai MA. Isolation and characterization of a gene for a repetitive proline rich protein (OsPRP) down-regulated during submergence in rice (Oryza sativa) Physiol Plant. 2003;118(4):507–513. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00104.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alscher RG, Erturk N, Heath LS. Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J Exp Bot. 2002;53(372):1331–1341. doi: 10.1093/jxb/53.372.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon DI. Copper enzyme in isolated chloroplast: polyphenol oxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Phyisol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroca R, Tognoni F, Irigoyen JJ, Sánchez-Díaz M, Pardossi A. Different root low temperature response of two maize genotypes differing in chilling sensitivity. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2001;39(12):1067–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0981-9428(01)01335-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39(1):205–207. doi: 10.1007/bf00018060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beffa R, Martin HV, Pilet PE. In vitro oxidation of indoleacetic acid by soluble auxin-oxidases and peroxidases from maize roots. Plant Physiol. 1990;94(2):485–491. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnecarrère V, Borsani O, Díaz P, Capdevielle F, Blanco P, Monza J. Response to photoxidative stress induced by cold in japonica rice is genotype dependent. Plant Sci. 2011;180(5):726–732. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortesi L, Fischer R. The CRISPR/Cas9 system for plant genome editing and beyond. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(1):41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson LF, Tenhaken R, Lamb C. Function of oxidative cross-linking of cell wall structural proteins in plant disease resistance. Plant Cell. 1994;6(12):1703–1712. doi: 10.2307/3869902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caverzan A, Passaia G, Rosa SB, Ribeiro CW, Lazzarotto F, Margis-Pinheiro M. Plant responses to stresses: role of ascorbate peroxidase in the antioxidant protection. Genet Mol Biol. 2012;35(4):1011–1019. doi: 10.1590/s1415-47572012000600016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wang S, Zhang YH, Li J, Xing ZH, Yang J, Huang T, Cai YD. Identify key sequence features to improve CRISPR sgRNA efficacy. IEEE Access. 2017;5:26582–26590. doi: 10.1109/access.2017.2775703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, Fowler S, Fiehn O, Thomashow MF. A prominent role for the CBF cold response pathway in configuring the low-temperature metabolome of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101(42):15243–15248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406069101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels C. Effect of root and shoot meristem temperature on shoot to root dry matter partitioning and the internal concentrations of nitrogen and carbohydrates in maize and wheat. Ann Bot. 1994;73(2):211–219. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1994.1025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Zhang B, Ding W, Liu X, Yang DL, Wei P, Cao F, Zhu S, Zhang F, Mao Y, Zhu JK. Efficient genome editing in plants using a CRISPR/Cas system. Cell Res. 2013;23(10):1229. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcat S, Bennett MH, Mansfield JW, Grant MR. A rapid and robust method for simultaneously measuring changes in the phytohormones ABA, JA and SA in plants following biotic and abiotic stress. Plant Methods. 2008;4(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler TJ, Bernhardt C, Tierney ML. Characterization and expression of four proline-rich cell wall protein genes in Arabidopsis encoding two distinct subsets of multiple domain proteins. Plant Physiol. 1999;121(4):1081–1091. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.4.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF., III ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31(7):397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Susa K, Yoda Y, Bonventre JV, Valerius MT, Morizane R. CRISPR/Cas9-based targeted genome editing for the development of monogenic diseases models with human pluripotent stem cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2018;45(1):e50. doi: 10.1002/cpsc.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Luo D, Usman B, Nawaz G, Zhao N, Liu F, Li R. Development of high yielding glutinous cytoplasmic male sterile rice (Oryza sativa L.) lines through CRISPR/Cas9 based mutagenesis of Wx and TGW6 and proteomic analysis of anther. Agronomy. 2018;8:290. doi: 10.3390/agronomy8120290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt EJ, Dickes GJ. Spectrophotometric measurements on ascorbic acid and their use for the estimation of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid in plant tissues. Biochem J. 1961;78(2):384–391. doi: 10.1042/bj0780384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y, Ohta S, Komari T, Kumashiro T. Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 1994;6(2):271–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6020271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Sun SJ, Xu DQ, Yang X, Bao YM, Wang ZF, Tang HJ, Zhang H. Increased tolerance of rice to cold, drought and oxidative stresses mediated by the overexpression of a gene that encodes the zinc finger protein ZFP245. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389(3):556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T, Tanaka W, Mikami M, Endo M, Hirano HY. Generation of artificial drooping leaf mutants by CRISPR-Cas9 technology in rice. Genes Genet Syst. 2015;90(4):231–235. doi: 10.1266/ggs.15-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang G, Lee S, Um TY, Chang SH, Lee HY, Chung PJ, Kim JK, Do Choi Y. Genetic chimerism of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated rice mutants. Plant Biotech Rep. 2016;10(6):425–435. doi: 10.1007/s11816-016-0414-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):233–239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YJ, Nogoy FM, Lee SK, Cho YG, Kang KK. Application of ZFN for site directed mutagenesis of rice SSIVa gene. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2018;23(1):108–115. doi: 10.1007/s12257-017-0420-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandpal RP, Rao NA. Alterations in the biosynthesis of proteins and nucleic acids in finger millet (Eleucine coracana) seedlings during water stress and the effect of proline on protein biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 1985;40(2):73–79. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(85)90044-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti V, Gupta AK. Overexpression of OsiSAP8, a member of stress associated protein (SAP) gene family of rice confers tolerance to salt, drought and cold stress in transgenic tobacco and rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66(5):445–462. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SI, Tai TH. Evaluation of seedling cold tolerance in rice cultivars: a comparison of visual ratings and quantitative indicators of physiological changes. Euphytica. 2011;178(3):437–447. doi: 10.1007/s10681-010-0343-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Lee SC, Hong SK, An K, An G, Kim SR. Ectopic expression of a cold-responsive OsAsr1 cDNA gives enhanced cold tolerance in transgenic rice plants. Mol Cells. 2009;27(4):449–458. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Choi HS, Cho YC, Kim SR. Cold-responsive regulation of a flower-preferential class III peroxidase gene, OsPOX1, in rice (Oryza sativa L.) J Plant Biol. 2012;55(2):123–131. doi: 10.1007/s12374-011-9194-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhang D, Chen M, Liang W, Wei J, Qi Y, Yuan Z. Development of japonica photo-sensitive genic male sterile rice lines by editing carbon starved anther using CRISPR/Cas9. J Genet Genomics. 2016;43(6):415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G, Zhang H, Lou D, Yu D. Selection of highly efficient sgRNAs for CRISPR/Cas9-based plant genome editing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21451. doi: 10.1038/srep21451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Wang Y, Tang J, Xue P, Li C, Liu L, Hu B, Yang F, Loake GJ, Chu C. Nitric oxide and protein S-nitrosylation are integral to hydrogen peroxide-induced leaf cell death in rice. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(1):451–464. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.184531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Chen L, Zhu Q, Chen Y, Liu YG. Rapid decoding of sequence-specific nuclease-induced heterozygous and bi-allelic mutations by direct sequencing of PCR products. Mol plant. 2015;8(8):1285–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Zhang Q, Zhu Q, Liu W, Chen Y, Qiu R, Wang B, Yang Z, Li H, Lin Y, Xie Y. A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol plant. 2015;8(8):1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz SU, Mittler RO. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33(4):453–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(9):405–410. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modarresi M, Nematzadeh GA, Moradian F, Alavi SM. Identification and cloning of the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene from halophyte plant Aeluropus littoralis. Genetika. 2012;48(1):130–134. doi: 10.1134/s1022795411100127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas CD, Lindstrom JT, Vodkin LO. Variation of proline rich cell wall proteins in soybean lines with anthocyanin mutations. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;21(1):145–156. doi: 10.1007/bf00039625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Foyer CH. Ascorbate and glutathione: keeping active oxygen under control. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 1998;49(1):249–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakabe Y, Watanabe T, Sugano SS, Ueta R, Ishihara R, Shinozaki K, Osakabe K. Optimization of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to modify abiotic stress responses in plants. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26685. doi: 10.1038/srep26685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poire R, Wiese-Klinkenberg A, Parent B, Mielewczik M, Schurr U, Tardieu F, Walter A. Diel time-courses of leaf growth in monocot and dicot species: endogenous rhythms and temperature effects. J Exp Bot. 2010;61(6):1751–1759. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W, Zhu T, Tian Z, Li C, Zhang W, Song R. High-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex gene editing using the glycine tRNA-processing system-based strategy in maize. BMC Biotechnol. 2016;16(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s12896-016-0289-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarrie SA, Whitford PN, Appleford NE, Wang TL, Cook SK, Henson IE, Loveys BR. A monoclonal antibody to (S)-abscisic acid: its characterisation and use in a radioimmunoassay for measuring abscisic acid in crude extracts of cereal and lupin leaves. Planta. 1988;173(3):330–339. doi: 10.1007/bf00401020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H, Gao Z, Chen L, Wei K, Liu J, Fan Y, Davies WJ, Jia W, Zhang J. Dynamic analysis of ABA accumulation in relation to the rate of ABA catabolism in maize tissues under water deficit. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(2):211–219. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Banerjee V, Das KP. Understanding the physical and molecular basis of stability of arabidopsis DNA Pol λ under UV-B and high NaCl stress. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M, Suzuki T. Effect of root-zone temperature on growth and quality of hydroponically grown red leaf lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. cv. Red Wave) Am J Plant Sci. 2015;6(14):2350–2360. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2015.614238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Masuta Y, Saito K, Murayama S, Ozawa K. Enhanced chilling tolerance at the booting stage in rice by transgenic overexpression of the ascorbate peroxidase gene, OsAPXa. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(3):399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah K, Dubey RS. Effect of cadmium on proline accumulation and ribonuclease activity in rice seedlings: role of proline as a possible enzyme protectant. Biol Plant. 1997;40(1):121–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1000956803911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter AM. Structure and function of plant cell wall proteins. Plant Cell. 1993;5(1):9. doi: 10.2307/3869424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siripornadulsil S, Traina S, Verma DP, Sayre RT. Molecular mechanisms of proline-mediated tolerance to toxic heavy metals in transgenic microalgae. Plant Cell. 2002;14(11):2837–2847. doi: 10.1105/tpc.004853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Zhang X, Wu C, He Y, Ma Y, Hou H, Guo X, Du W, Zhao Y, Xia L. Engineering herbicide-resistant rice plants through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination of acetolactate synthase. Mol Plant. 2016;9(4):628–631. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney ML, Wiechert J, Pluymers D. Analysis of the expression of extensin and p33-related cell wall proteins in carrot and soybean. Mol Gen Genet MGG. 1988;211(3):393–399. doi: 10.1007/bf00425691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venekamp JH. Regulation of cytosol acidity in plants under conditions of drought. Physiol Plant. 1989;76(1):112–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1989.tb05461.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Wang C, Liu P, Lei C, Hao W, Gao Y, Liu YG, Zhao K. Enhanced rice blast resistance by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the ERF transcription factor gene OsERF922. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0154027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XH, Mao AJ, Wang R, Wang T, Song Y, Tong Z. Cloning and characterization of OsPRP1 involved in anther development in rice. Chin Sci Bull. 2003;48:2458–2465. doi: 10.1360/03wc0299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie G, Kato H, Imai R. Biochemical identification of the OsMKK6–OsMPK3 signalling pathway for chilling stress tolerance in rice. Biochem J. 2012;443(1):95–102. doi: 10.1042/bj20111792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Kawasaki S, Fujimura T, Wang C. A protocol for high-throughput extraction of DNA from rice leaves. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2005;23(3):291–295. doi: 10.1007/bf02772759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu RF, Li H, Qin RY, Li J, Qiu CH, Yang YC, Ma H, Li L, Wei PC, Yang JB. Generation of inheritable and “transgene clean” targeted genome-modified rice in later generations using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11491. doi: 10.1038/srep11491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Yang Y, Qin R, Li H, Qiu C, Li L, Wei P, Yang J. Rapid improvement of grain weight via highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex genome editing in rice. J Genet Genomics. 2016;43(8):529–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Chen Q, Wang S, Hong Y, Wang Z. Rice and cold stress: methods for its evaluation and summary of cold tolerance-related quantitative trait loci. Rice. 2014;7(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12284-014-0024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Yang S, Zhang D, Zhong Z, Tang X, Deng K, Zhou J, Qi Y, Zhang Y. Effective screen of CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutants in rice by single-strand conformation polymorphism. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35(7):1545–1554. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-1967-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Peng Z, Long J, Sosso D, Liu B, Eom JS, Huang S, Liu S, Vera Cruz C, Frommer WB, White FF. Gene targeting by the TAL effector PthXo2 reveals cryptic resistance gene for bacterial blight of rice. The Plant J. 2015;82(4):632–643. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Wei G, Li J, Qian Q, Yu J. Silicon alleviates salt stress and increases antioxidant enzymes activity in leaves of salt-stressed cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Plant Sci. 2004;167(3):527–533. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.04.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.