Abstract

The effects of testing solutions and conditions on hydroxyapatite (HAp) formation as a means of in vitro bioactivity evaluation of B2O3 containing 45S5 bioactive glasses were systematically investigated. Four glass samples prepared by the traditional melt and quench process, where SiO2 in 45S5 was gradually replaced by B2O3 (up to 30%), were studied. Two solutions: the simulated body fluid (SBF) and K2HPO4 solutions were used as the medium for evaluating in vitro bioactivity through the formation of HAp on glass surface as a function of time. It was found that addition of boron oxide delayed the HAp formation in both SBF and K2HPO4 solutions, while the reaction between glass and the K2HPO4 solution is much faster as compared to SBF. In addition to the composition and medium effects, we also studied whether the solution treatments (e.g., adjusting to maintain a pH of 7.4, refreshing solution at certain time interval, and no disturbance during immersion) affect HAp formation. Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) equipped with an attenuated total reflection (ATR) sampling technique and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were conducted to identify HAp formation on glass powder surfaces and to observe HAp morphologies, respectively. The results show that refreshing solution every 24 h produced the fastest HAp formation for low boron-containing samples when SBF was used as testing solution, while no significant differences were observed when K2HPO4 solution was used. This study thus suggests the testing solutions and conditions play an important role on the in vitro bioactivity testing results and should be carefully considered when study materials with varying bioactivities.

Keywords: Bioactive glasses, Boron oxide, In vitro, Hydroxyapatite

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Four bioactive glass compositions with different levels of B2O3 to SiO2 substitution in 45S5 were studied.

-

•

The effect of solution type and solution condition on in vitro bioactivity testing were studied.

-

•

Results show that boron oxide addition increases the tendency of crystallization of the 45S5 bioactive glasses.

-

•

Testing using K2HPO4 solution show faster speed of hydroxyapatite formation than SBF.

-

•

Solution conditions play an important role on in vitro SBF bioactivity testing.

1. Introduction

45S5 Bioglass® with a composition of 46.1SiO2-24.4Na2O-26.9CaO-2.6P2O5 in mol% was discovered by Prof. Larry Hench in 1969 [1,2]. Various clinical products were developed based on 45S5 Bioglass®, such as orthopedics products for trauma, arthroplasty and spine fusion, cranial-facial products for cranioplasty, general oral/dental defect and periodontal repair, and dental-maxillofacial-ENT products (e.g., toothpaste, pulp capping, sinus obliteration, repair of orbital floor fracture) [3]. After the discovery of 45S5, many new bioactive glass compositions have been developed, since the glass matrix can accommodate various elements while maintaining the glass character and properties [4,5]. This composition flexibility enables the possibility to introduce additional functional elements that can potentially benefits to human body [6] such as enhancement of osteo-growth by Sr2+ [[7], [8], [9]], angiogenesis by Cu2+ [[10], [11], [12]], antibacterial by Ag+ [13]. Recently, B2O3 containing bioactive glasses have drawn attention due to its potential effects and consequential biomedical applications, such as osteogenesis [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18]], angiogenesis [19], soft tissue repair [20], supporting tissue infiltration [21], controllable glass dissolution [21,22], improving coating adhesion [23,24], widening the processing window [25] and improving mechanical properties [26]. Accurate evaluation of the compositional effect, in particular the amount of B2O3, on the in vitro and in vivo bioactivity becomes critical while designing bioactive glass compositions for these applications.

Bioactive material is defined as a material that stimulates beneficial responses from the living tissue, organisms or cells, by inducing the formation of hydroxyl apatite (HAp) through which the material bonds to the host tissue [4]. Inorganic glasses in certain compositions such as 45S5 or other bioactive glasses, following the initial dissolution, illicit formation of HAp on the glass surface. The ability to form HAp in biological environment thus presents a means of evaluating the bioactivity of materials. There are generally two ways to evaluate bioactivity: in vitro and in vivo methods. An in vitro method evaluates bioactivity by testing the material in controlled environment outside living organism, such as by immersing materials in solutions such as simulated body fluid (SBF) or cell cultures. In vitro method is in general more economical and easier to implement as compared to an in vivo method which requires living organisms such as animal models. Nevertheless, it was found that bioactivity evaluated in vitro is generally agreeable with in vivo bioactivity with a few exceptions [27,28]. However, many challenges exist in study dissolution and bioactivity of glass materials in vitro [29], where testing conditions (e.g., glass mass [30] or glass surface area [31] to solution volume ratio, particle size [32], SBF preparation [27], medium pH [33], ion concentration [34], buffer type [35] and solution replenishment frequency [36]) directly affect the final results and interpretation of the glass bioactivity. For instance, mixed results were found in terms of bioactivity of boron-containing silicate glasses. Several studies showed that replacing SiO2 with B2O3 produced a more rapid conversion of the glass to HAp [21,22,32], while some studies have also shown that the addition of boron impeded the HAp formation in vitro [31,[37], [38], [39], [40], [41]]. Various testing conditions can be one of the main reasons that caused these non-conclusive results from these studies.

In this work, we adopted a unified evaluation protocol proposed by Macon et al. [29] for bioactivity evaluation of glasses. The main objective is to investigate solution effects on HAp formation of boron-containing glasses in vitro by using both SBF and K2HPO4 with three different treatments. The rest of paper is arranged as following: methodology of glass synthesis procedure, bioactivity evaluation details and characterizations will be reported first. Then the results on characterizations of original glass samples, FTIR spectra of samples after different solution treatments and HAp morphology observed by SEM are presented. This is followed by discussions and conclusions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Glass synthesis procedures

Compositions of the glasses studied in this paper are shown in Table 1. SiO2 was gradually (10, 20 and 30%) replaced by B2O3. The glasses were prepared by thoroughly mixing analytical grade H3BO3, NH4H2PO4, SiO2, NaCO3 and CaCO3 chemicals before melting in an Al2O3 crucible at 1300 °C for 2 h in an electrical furnace (Deltech Furnaces). Molten glasses were poured onto a stainless plate and cooled to room temperature.

Table 1.

Composition (mol%) of the glasses studied.

| Sample | Composition (mol%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2O3 | SiO2 | Na2O | CaO | P2O5 | |

| 0B | 0 | 46.1 | 24.4 | 26.9 | 2.6 |

| 5B | 4.6 | 41.5 | 24.4 | 26.9 | 2.6 |

| 9B | 9.2 | 36.9 | 24.4 | 26.9 | 2.6 |

| 14B | 13.8 | 32.3 | 24.4 | 26.9 | 2.6 |

Powder glass samples were prepared by manually crushing the bulk glass of each composition, grinding with an alumina mortar and pestle, and sieving to 32–45 μm with stainless steel sieves. Glass powders were cleaned in deionized (DI) water and ethanol two times each in an ultrasonic cleanser, respectively. Cleaned glass powders were oven-dried (90 °C) overnight and pending for in vitro tests.

2.2. Bioactivity evaluations

0.02 mol/L K2HPO4 solution was prepared by dissolving reagent grade K2HPO4∙3H2O in DI water, where the starting pH was 9.10 at room temperature, following studies on other boron-containing glasses [[42], [43], [44]]. pH measurements were performed on a bench-top pH/mV meter (Sper Scientific) with an accuracy of ±0.02 pH. Simulated body fluids (SBFs) were prepared according to a study of Kokubo and Takadama [27] by mixing reagent grade chemicals in the following order: NaCl (8.035 g), NaHCO3 (0.355 g), KCl (0.225 g), K2HPO4∙3H2O (0.231 g), MgCl2∙6H2O (0.311 g), 1 mol/L HCl (39 mL), CaCl2 (0.292 g) and Na2SO4 (0.072 g) in DI water (700 mL) with a plastic beaker at 37 °C. After the chemicals completely dissolved, DI water was added up to 900 mL in total, and the pH of the solution was 1.5 ± 0.1 at the time. The fluid was buffered to a pH value of 7.40 at 36 ± 0.5 °C by slowly adding tris (trihydroxymethyl)-aminomethane (total 6.118 g) and drops of 1 mol/L HCl alternately in order to maintain a fluctuation of pH values between 7.40 and 7.45. After dissolving all tris(trihydroxymethyl)-aminomethane, the solution was filled with DI water up to 1 L at room temperature.

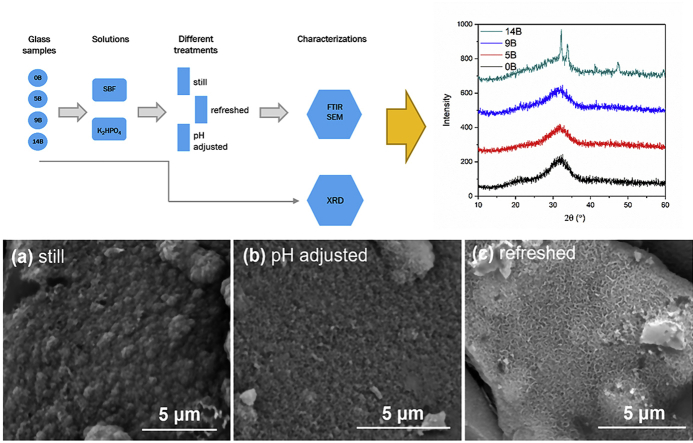

Powder samples were used for in vitro tests, following a unified evaluation proposed by Macon et al. [29]: each 75 ± 0.5 mg glass powder was put in a polypropylene tube (Corning Inc.) with a 50 mL solution at 37 ± 0.2 °C up to 10 days. The tubes were agitated at an interval time throughout the in vitro tests to prevent glass powders from sticking together. Three different solution treatments were conducted on each glass composition: 1) no refreshment or adjustment of solutions was performed (referred as “still treatment”); 2) solutions were adjusted with HCl drops every 24 h to maintain a pH value of 7.4 (referred at “adjusted treatment”); 3) solutions were refreshed every 24 h (referred as “refreshed treatment”). Glass powders were obtained at different time intervals, washed in ethanol and oven-dried (90 °C) overnight. Fig. 1 shows an outline of the experimental details.

Fig. 1.

Outline of the experimental details.

2.3. Glass characterizations

Glass powders were characterized with high-resolution X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Rigaku Ultima III with a scanning speed of 3°/min and a step of 0.03°/point. XRD pattern analysis was performed with JADE 9 software package.

Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) equipped with an attenuated total reflection (ATR) sampling technique was conducted with a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer (Thermo Electron) at room temperature. A diamond substrate was used for the ATR sampling. A total of 32 scans for background and per sample were used with a resolution of 2 cm−1. A commercial HAp powder (calcium phosphate tribasic) obtained from Fisher Scientific was taken as a reference material.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted on a FEI Quanta ESEM to observe surface morphology of SBF treated samples after Au–Pd coating.

3. Results

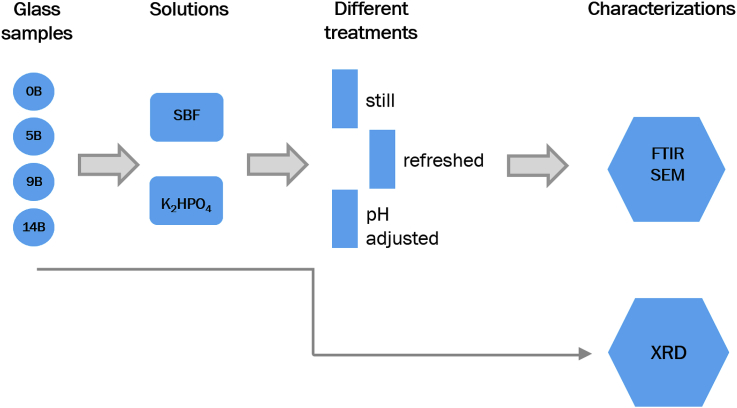

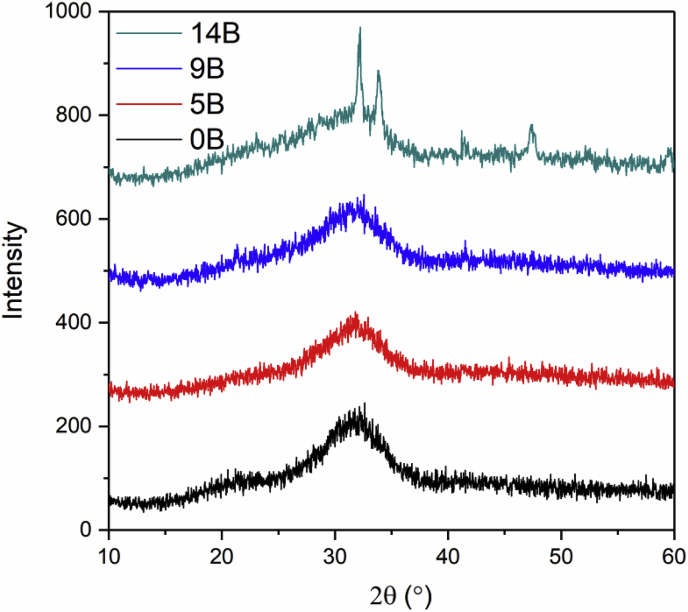

XRD patterns of the four glass samples obtained from the melt-quench process are shown in Fig. 2. 14B sample was partially crystallized as shown in Fig. 2, where the crystalline phases could be Na3Ca6(PO4)5 or hexagonal Na2Ca4(PO4)2SiO4, as studied previously [41]. Fig. 3 presents photos of the glass samples. Even though no crystallization peaks were observed from XRD pattern of 9B, there are heterogeneous phases in 9B as visually observed from the sample (shown in Fig. 3 (c)). In our previous studies [39,41], it was also observed that addition of boron increases the crystallization tendency of both 45S5 and 55S4.3 bioactive glasses at low SiO2/B2O3 substitution, while no crystallization was found at high substitution levels (>50%). It was found that crystallization delayed the initial time of HAp formation on 45S5 but did not inhibit the formation of HAp [45].

Fig. 2.

XRD patterns of the prepared glass samples.

Fig. 3.

Photos of the prepared glass samples.

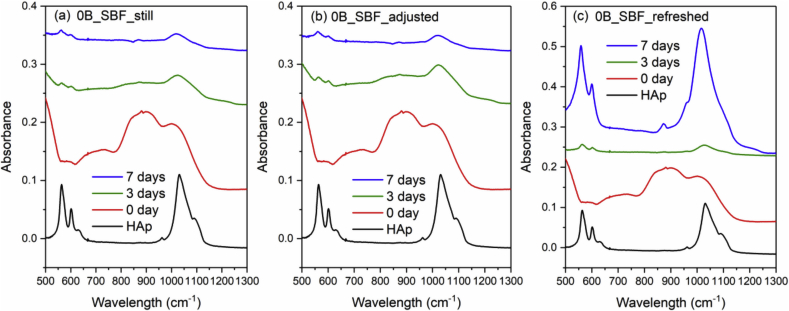

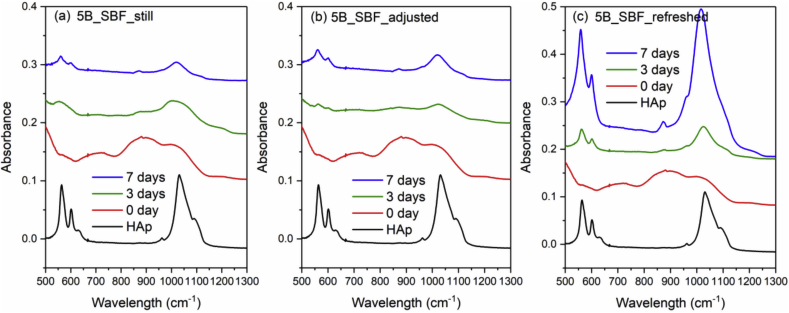

Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 show the FTIR spectra of 0B and 5B after SBF immersion with three different solution treatments (still, adjusted and refreshed), along with a FTIR spectrum of a commercial HAp powder for reference. The appearance of a split phosphate P–O bending band (∼560 and 600 cm−1), P–O stretching band (∼1015 cm−1) and a carbonate band (∼870 cm−1) indicates the formation of HAp [46]. For both 0B and 5B samples, refreshing SBF every 24 h promotes the HAp formation on glass surface, while still and adjusted treatments exhibit slower and similar HAp formation. However, for 9B and 14B samples, no HAp formation was identified by FTIR after SBF treatments for 10 days (shown in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7).

Fig. 4.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 0B after SBF immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

Fig. 5.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 5B after SBF immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

Fig. 6.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 9B after SBF immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

Fig. 7.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 14B after SBF immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

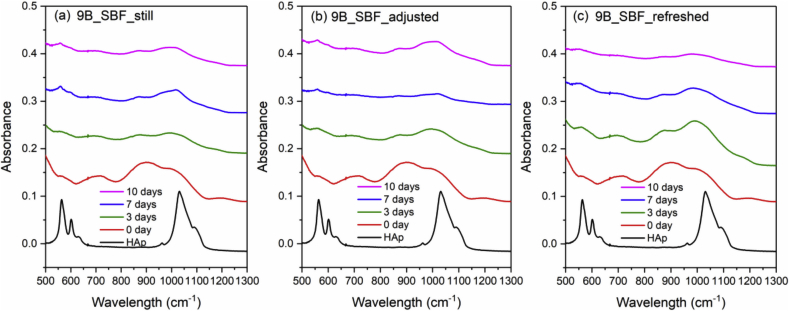

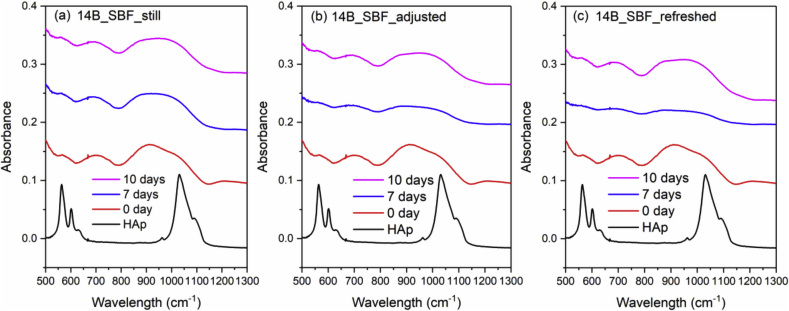

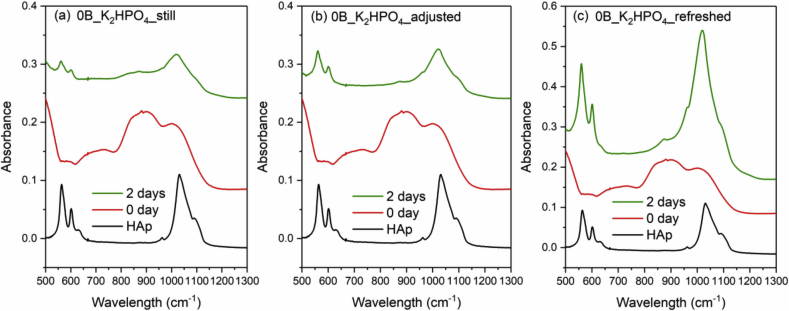

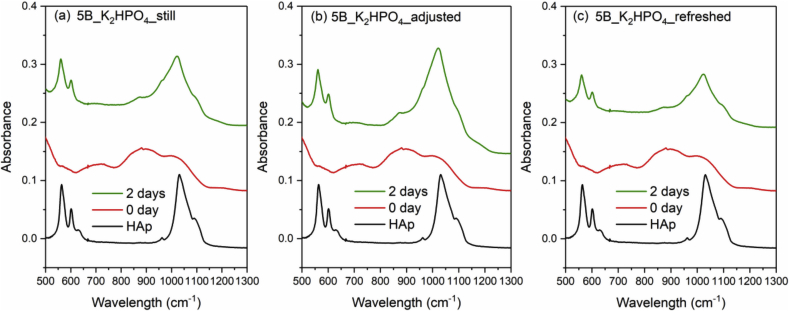

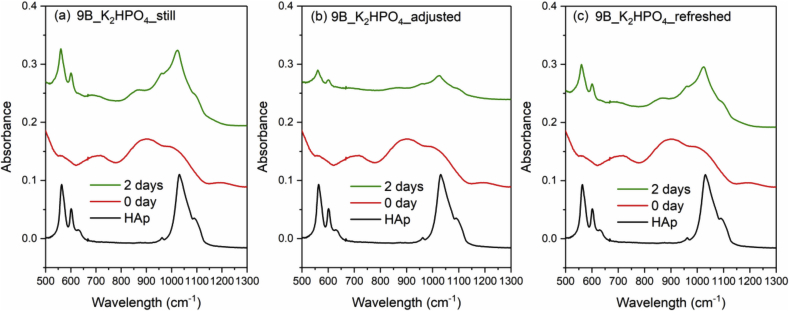

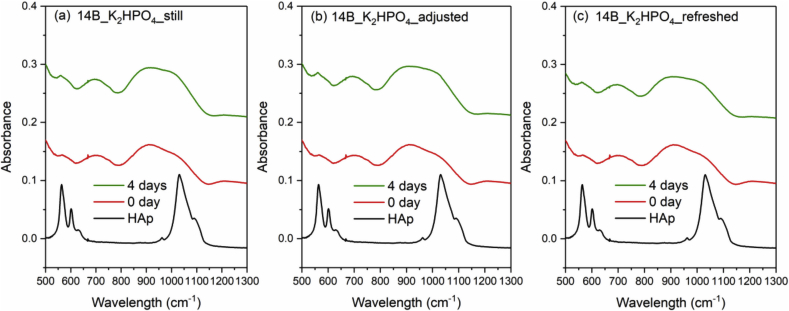

Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10 and Fig. 11 show the FTIR spectra of 0B, 5B, 9B and 14B after K2HPO4 solution immersion with three different solution treatments, respectively. As compared to SBF treatments, HAp formation is much faster in K2HPO4 solution. Except 14B sample, HAp formation was identified by FTIR after 2 days of immersion for all samples among all the solution treatments. For 14B, HAp formation was not identified after 4 days of immersion for all treatments. Shorter sampling points are needed for K2HPO4 solution in order to observe difference between glass compositions and solution treatments.

Fig. 8.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 0B after K2HPO4 solution immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

Fig. 9.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 5B after K2HPO4 solution immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

Fig. 10.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 9B after K2HPO4 solution immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

Fig. 11.

FTIR spectra of the commercial HAp powder and 14B after K2HPO4 solution immersion with three different solution treatments, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

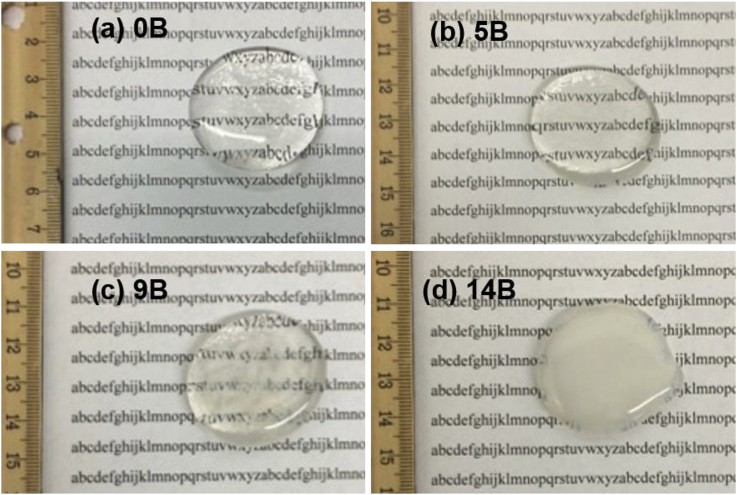

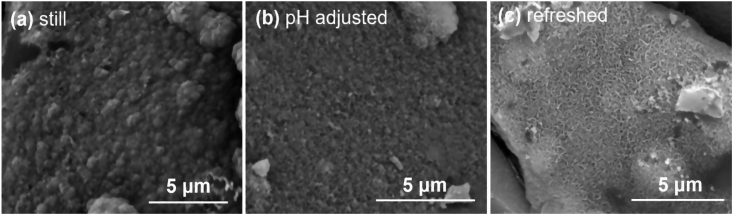

SEM images of 0B after SBF immersion with three different solution treatments are shown in Fig. 12. Different HAp morphology was observed on glass surface after 7 days of SBF treatments. HAp formed after still treatment (Fig. 12 (a)) has a spherical feature in comparison with the other two treatments, which is consistent with a previous study [41]. For refreshed treatment, HAp precipitates have a needle-shaped or a flaky feature (Fig. 12 (c)); whereas, HAp formed after pH adjusted treatment ((Fig. 12 (b)) are more granular and no other distinguishable features were observed.

Fig. 12.

SEM images of 0B after SBF immersion with three different solution treatments for 7 days, where (a), (b) and (c) is still, adjusted and refreshed, respectively.

4. Discussions

Through this study, we found that different HAp growth behaviors and surface morphology during bioactivity testing when different solutions (SBF versus K2HPO4 solution) and testing conditions (e.g. static, refreshing, pH control) were used, suggesting complexity of the testing and calling for protocols to evaluate bioactivity of glass and glass-ceramic materials. The results indicate that solution chemistry has a significant effect on glass dissolution and HAp formation, and consequently the bioactivity. These results are in general consistent with those reported in the literature, where various testing conditions such as glass surface area to solution volume ratio [31], medium pH [33], ion concentration [34], buffer type [35] and solution replenishment frequency [36] were found to affect the final results and interpretation of the glass bioactivity. The mechanism of HAp formation [47,48] generally involves: 1) rapid cation exchange and creating silanol bonds (Si–OH) on the glass surface; 2) breaking Si–O–Si bonds caused by high local pH; 3) condensation of Si–OH groups near the glass surface and repolymerization of the silica-rich layer; 4) migration of Ca2+ and PO43− through the silica-rich layer and from the solution, forming a film rich in amorphous CaO–P2O5 on the silica-rich layer; 5) incorporation of hydroxyls and carbonate from solution and crystallization of the CaO–P2O5 film to HAp. The Si–OH groups in SiO2-rich layer were believed to provide nucleation sites for the apatite formation [49,50]; however, some studies have demonstrated that glasses without Si can form HAp in vitro as well [21,22,31,32,[51], [52], [53], [54]]. Solution chemistry can greatly affect the concentration of the ions (particularly Ca2+, PO43−) critical for HAp formation, dissolution of the glasses, migration of ions from glass and solution, as well as nucleation and crystallization growth of HAp, leading to various results of glass bioactivity evaluations. For example, refreshing the test solutions would provide a constant level of critical ions for HAp formation hence lead to the highest HAp growth rate. This becomes critical when compositions that have low bioactivity are tested. Therefore, choosing the appropriate in vitro testing conditions is critical for evaluation and study the bioactivity of glass materials.

Very different conditions were used in the literature for bioactivity testing. For example, tests using the K2HPO4 solution were usually not buffered while SBF contained TRIS buffer. It was found previously that the TRIS buffer in SBF distorts the assessment of glass-ceramic scaffold bioactivity, where TRIS buffer can increase the dissolving rate (by two times) of the glass and facilitate the HAp formation as compared to SBF solution without TRIS buffer [55]. As compared to SBF, however, HAp formation was found to be much faster in the K2HPO4 solution in our study. For instance, HAp formation of 9B was identified by FTIR after immersion in K2HPO4 solution for 2 days, while no HAp formation was found after SBF immersion for 10 days. This might be caused by the high concentration of HPO42− ions (1.0 mM in SBF [27] and 20 mM in K2HPO4 solution) and the high starting pH value (7.4 for SBF and 9.1 for K2HPO4 solution) of K2HPO4 solution, resulting a faster glass dissolution and HAp precipitation.

It was found that refreshing SBF every 24 h led to a much quicker HAp formation, while the 0B and 5B samples show the fastest HAp growth. The other two conditions, still or pH adjustment treatments, on the other hand, showed no significant effect on the speed of HAp formation. This indicates that ion concentrations in SBF, which provide source of phosphorus and calcium ions, has a far greater impact on HAp formation than the pH variation. On the other hand, no obvious trend was observed for the three treatments tested using the K2HPO4 solution. This might be due to the much higher phosphate concentration in K2HPO4 than SBF, suggesting that shorter sampling intervals are needed for K2HPO4 solution in order to observe differences between glass compositions and solution treatments.

Different HAp crystal morphologies were observed by SEM imaging for 45S5 samples treated in SBF solution with different conditions. Previously, it was found that the morphology of HAp formed depends on the types of immersion solutions [35,36,41]. In this work, even though the same medium (e.g., SBF) was used, different solution treatments were found to have a noticeable impact on the morphology of HAp formed as well, indicating that ion concentrations in solution and pH can also greatly affect HAp nucleation and formation mechanisms. Surface analyzing tests are desired for better study the effect of solution treatments on the composition of calcium phosphate precipitates (e.g., Ca/P ratio) formed. For example, the increased pH of the SBF during in vitro test can affect Ca/P molar ratios and chemical compositions of calcium phosphate precipitates [56]. HCO3− concentration in SBF can affect the thickness of calcium phosphate formed [34], as well as the heterogeneity and the crystal size of the calcium phosphate precipitates [57]. Additionally, it was found that chloride ions in TRIS-HCl butter solution were incorporated in the apatite formation during immersion tests, affecting the final composition of precipitates [46]. Future detailed compositional studies of formed HAp are desired for better understanding the apatite formation mechanism, which can benefit the improvement of in vitro bioactivity evaluation of glass materials, as well as designing new functional biomaterials (e.g., apatite formed matches bone or dentin tissue [58,59]).

5. Conclusions

The effects of three solution treatment conditions: still, pH adjusted, and refreshed for SBF and K2HPO4 solutions on HAp formation for in vitro bioactivity testing were studied on a series of boron oxide containing 45S5 bioactive glasses. It was found that, in general, substituting SiO2 with B2O3 (up to 30%) in 45S5 delayed the HAp formation in both SBF and K2HPO4 solutions. Refreshing SBF was found to lead to the fastest HAp formation for low boron-containing glasses, while refreshing solution was found to have no significant differences on the results while using the K2HPO4 solution. It was also observed that HAp formation is much faster in K2HPO4 solution as compared to SBF. Additionally, different morphologies of HAp precipitates were observed by SEM on the glass surface of 45S5 after immersion in SBF for 7 days, indicating that ion concentrations and solution pH can affect HAp nucleation and formation mechanisms. These results provide insights on understanding the test conditions on in vitro bioactivity testing and how to better evaluate novel bioactive glasses with ever increasing composition domains. Further studies to find out the HAp composition differences would be beneficial to understand the formation mechanisms and how the solution composition affect HAp crystal nucleation and growth.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support of the NSF Ceramics program (project #1508001) and JK acknowledges support of the NSF REU program (project #1461048). SEM, XRD and FTIR experiments were conducted at the Materials Research Facility (MRF), a shared research facility for multidimensional fabrication and characterization at University of North Texas (UNT).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Hench L.L., Splinter R.J., Allen W.C., Greenlee T.K. Bonding mechanisms at the interface of ceramic prosthetic materials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1971;5:117–141. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hench L.L. The story of Bioglass. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006;17:967–978. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0432-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hench L.L. Chronology of bioactive glass development and clinical applications. New J. Glass Ceram. 2013;03:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones J.R. Reprint of: review of bioactive glass: from Hench to hybrids. Acta Biomater. 2015;23:S53–S82. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabiee S.M., Nazparvar N., Azizian M., Vashaee D., Tayebi L. Effect of ion substitution on properties of bioactive glasses: a review. Ceram. Int. 2015;41:7241–7251. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur G., Pandey O.P., Singh K., Homa D., Scott B., Pickrell G. A review of bioactive glasses: their structure, properties, fabrication and apatite formation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2014;102:254–274. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell M.D., Hill R.G., Donnell M.D.O., Hill R.G. Influence of strontium and the importance of glass chemistry and structure when designing bioactive glasses for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2382–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian M., Chen F., Song W., Song Y., Chen Y., Wan C., Yu X., Zhang X. In vivo study of porous strontium-doped calcium polyphosphate scaffolds for bone substitute applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009;20:1505–1512. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakhkar N.J., Abou Neel E.A., Salih V., Knowles J.C. Strontium oxide doped quaternary glasses: effect on structure, degradation and cytocompatibility. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009;20:1339–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raju K.S., Alessandri G., Ziche M., Gullino P.M. Ceruloplasmin, copper ions, and angiogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1982;69:1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahaman M.N., Day D.E., Sonny Bal B., Fu Q., Jung S.B., Bonewald L.F., Tomsia A.P. Bioactive glass in tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2355–2373. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stähli C., James-Bhasin M., Hoppe A., Boccaccini A.R., Nazhat S.N. Effect of ion release from Cu-doped 45S5 Bioglass® on 3D endothelial cell morphogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2015;19:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellantone M., Coleman N.J., Hench L.L. Bacteriostatic action of a novel four-component bioactive glass. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000;51:484–490. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<484::aid-jbm24>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haro Durand L.A., Góngora A., Porto López J.M., Boccaccini A.R., Zago M.P., Baldi A., Gorustovich A. In vitro endothelial cell response to ionic dissolution products from boron-doped bioactive glass in the SiO2-CaO-P2O5-Na2O system. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2:7620–7630. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01043d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorustovich A.A., López J.M.P., Guglielmotti M.B., Cabrini R.L. Biological performance of boron-modified bioactive glass particles implanted in rat tibia bone marrow. Biomed. Mater. 2006;1:100–105. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/1/3/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X., Zhao Y., Geng S., Miron R.J., Zhang Q., Wu C., Zhang Y. In vivo experimental study on bone regeneration in critical bone defects using PIB nanogels/boron-containing mesoporous bioactive glass composite scaffold. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:839–846. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S69001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balasubramanian P., Büttner T., Miguez Pacheco V., Boccaccini A.R. Boron-containing bioactive glasses in bone and soft tissue engineering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018;38:855–869. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu C., Miron R., Sculean A., Kaskel S., Doert T., Schulze R., Zhang Y. Proliferation, differentiation and gene expression of osteoblasts in boron-containing associated with dexamethasone deliver from mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7068–7078. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haro Durand L.A., Vargas G.E., Romero N.M., Vera-Mesones R., Porto-López J.M., Boccaccini A.R., Zago M.P., Baldi A., Gorustovich A. Angiogenic effects of ionic dissolution products released from a boron-doped 45S5 bioactive glass. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:1142–1148. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01840k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marquardt L.M., Day D., Sakiyama-Elbert S.E., Harkins A.B. Effects of borate-based bioactive glass on neuron viability and neurite extension. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2014;102:2767–2775. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu Q., Rahaman M.N., Fu H., Liu X., Bal B.S., Bonewald L.F., Kuroki K., Brown R.F., Fu H., Liu X. Silicate, borosilicate, and borate bioactive glass scaffolds with controllable degradation rate for bone tissue engineering applications. I. Preparation and in vitro degradation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2010;95A:164–171. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao A., Wang D., Huang W., Fu Q., Rahaman M.N., Day D.E. In vitro bioactive characteristics of borate-based glasses with controllable degradation behavior. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2007;90:303–306. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brow R.K., Saha S.K., Goldstein J.I. Interfacial reactions between titanium and borate glass. MRS Online Proc. Libr. Arch. 1993;314:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peddi L., Brow R.K., Brown R.F. Bioactive borate glass coatings for titanium alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008;19:3145–3152. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez O., Curran D.J., Papini M., Placek L.M., Wren A.W., Schemitsch E.H., Zalzal P., Towler M.R. Characterization of silica-based and borate-based, titanium-containing bioactive glasses for coating metallic implants. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2016;433:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie K., Zhang L.L., Yang X., Wang X., Yang G., Zhang L.L., He Y., Fu J., Gou Z., Shao H., He Y., Fu J., Gou Z. Preparation and characterization of low temperature heat-treated 45S5 bioactive glass-ceramic analogues. Biomed. Glas. 2015;1:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kokubo T., Takadama H. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials. 2006;27:2907–2915. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zadpoor A.A. Relationship between in vitro apatite-forming ability measured using simulated body fluid and in vivo bioactivity of biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2014;35:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macon A.L., Kim T.B., Valliant E.M., Goetschius K., Brow R.K., Day D.E., Hoppe A., Boccaccini A.R., Kim I.Y., Ohtsuki C., Kokubo T., Osaka A., Vallet-Regi M., Arcos D., Fraile L., Salinas A.J., Teixeira A.V., Vueva Y., Almeida R.M., Miola M., Vitale-Brovarone C., Verne E., Holand W., Jones J.R., Maçon A.L.B., Kim T.B., Valliant E.M., Goetschius K., Brow R.K., Day D.E., Hoppe A., Boccaccini A.R., Kim I.Y., Ohtsuki C., Kokubo T., Osaka A., Vallet-Regí M., Arcos D., Fraile L., Salinas A.J., Teixeira A.V., Vueva Y., Almeida R.M., Miola M., Vitale-Brovarone C., Verné E., Höland W., Jones J.R. A unified in vitro evaluation for apatite-forming ability of bioactive glasses and their variants. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015;26:115. doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones J.R., Sepulveda P., Hench L.L. Dose-dependent behavior of bioactive glass dissolution. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;58:720–726. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manupriya, Thind K.S., Sharma G., Singh K., Rajendran V., Aravindan S. Soluble borate glasses: in vitro analysis. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2007;90:467–471. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang W., Day D.E., Kittiratanapiboon K., Rahaman M.N. Kinetics and mechanisms of the conversion of silicate (45S5), borate, and borosilicate glasses to hydroxyapatite in dilute phosphate solutions. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006;17:583–596. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-9220-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bingel L., Groh D., Karpukhina N., Brauer D.S. Influence of dissolution medium pH on ion release and apatite formation of Bioglass® 45S5. Mater. Lett. 2015;143:279–282. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorozhkina E.I., Dorozhkin S.V. Surface mineralisation of hydroxyapatite in modified simulated body fluid (mSBF) with higher amounts of hydrogencarbonate ions. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2002;210:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jalota S., Bhaduri S.B., Tas A.C. Effect of carbonate content and buffer type on calcium phosphate formation in SBF solutions. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006;17:697–707. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-9680-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varila L., Fagerlund S., Lehtonen T., Tuominen J., Hupa L. Surface reactions of bioactive glasses in buffered solutions. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2012;32:2757–2763. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebisawa Y., Kokubo T., Ohura K., Yamamuro T. Bioactivity of CaO·SiO2-based glasses:in vitro evaluation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1990;1:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill R. An alternative view of the degradation of bioglass. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1996;15:1122–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu X., Deng L., Kuo P.H., Ren M., Buterbaugh I., Du J. Effects of boron oxide substitution on the structure and bioactivity of SrO-containing bioactive glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 2017;52:8793–8811. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu Y., Edén M. Structure–composition relationships of bioactive borophosphosilicate glasses probed by multinuclear 11B, 29Si, and 31P solid state NMR. RSC Adv. 2016;6:101288–101303. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu X., Deng L., Huntley C., Ren M., Kuo P.H., Thomas T., Chen J., Du J. Mixed network former effect on structure, physical properties, and bioactivity of 45S5 bioactive glasses: an integrated experimental and molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:2564–2577. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang W., Day D.E., Rahaman M.N. Conversion of tetranary borate glasses to phosphate compounds in aqueous phosphate solution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008;91:1898–1904. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang W., Day D.E., Rahaman M.N. Comparison of the formation of calcium and barium phosphates by the conversion of borate glass in dilute phosphate solution at near room temperature. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2007;90:838–844. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang W., Rahaman M.N., Day D.E., Marion N.W., Riley G.C., Mao J.J. Bioactive borate glass scaffold for bone tissue engineering. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2008;354:1690–1696. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Filho O.P., Latorre G.P., Hench L.L., Peitl Filho O., Latorre G.P., Hench L.L. Effect of crystallization on apatite-layer formation of bioactive glass 45S5. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1996;30:509–514. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199604)30:4<509::AID-JBM9>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirste G., Brandt-Slowik J., Bocker C., Steinert M., Geiss R., Brauer D.S. Effect of chloride ions in tris buffer solution on bioactive glass apatite mineralisation. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2017:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hench L.L. Bioceramics: from concept to clinic. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991;74:1487–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clark A.E., Pantano C.G., Hench L.L. Auger spectroscopic analysis of bioglass corrosion films. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1976;59:37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hench L.L., Wilson J. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.; Singapore: 1993. An Introduction to Bioceramics. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brauer D.S., Karpukhina N., O'Donnell M.D., V Law R., Hill R.G. Fluoride-containing bioactive glasses: effect of glass design and structure on degradation, pH and apatite formation in simulated body fluid. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3275–3282. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdelghany A.M. The elusory role of low level doping transition metals in lead silicate glasses. Siliconindia. 2010;2:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manupriya K.S., Thind K., Singh V., Kumar G., Sharma D.P., Singh D.P. Compositional dependence of in-vitro bioactivity in sodium calcium borate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2009;70:1137–1141. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cai S., Xu G.H., Yu X.Z., Zhang W.J., Xiao Z.Y., Yao K.D. Fabrication and biological characteristics of beta-tricalcium phosphate porous ceramic scaffolds reinforced with calcium phosphate glass. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009;20:351–358. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3591-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saranti A., Koutselas I., Karakassides M.A. Bioactive glasses in the system CaO–B2O3–P2O5: preparation, structural study and in vitro evaluation. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2006;352:390–398. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rohanová D., Boccaccini A.R., Yunos D.M., Horkavcová D., Březovská I., Helebrant A. TRIS buffer in simulated body fluid distorts the assessment of glass-ceramic scaffold bioactivity. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2623–2630. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J., Liao H., Sjostrom M. Characterization of calcium phosphates precipitated from simulated body fluid of different buffering capacities. Biomaterials. 1997;18:743–747. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barrere F., Van Blitterswijk C.A., De Groot K., Layrolle P. Influence of ionic strength and carbonate on the Ca-P coating formation from SBF×5 solution. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1921–1930. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wopenka B., Pasteris J.D. A mineralogical perspective on the apatite in bone. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2005;25:131–143. [Google Scholar]

- 59.V Dorozhkin S., Epple M. Biological and medical significance of calcium phosphates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3130–3146. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3130::AID-ANIE3130>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]