Abstract

Invasive cardiac aspergillosis has been rarely described in immunocompromised patients. This disease is difficult to diagnose by conventional laboratory, microbiologic, and imaging techniques, and is often recognized only post-mortem. The authors present the case of a 60-year-old woman admitted with an exacerbation of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitiis (EGPA) who subsequently died from Aspergillus myocarditis, and compare the patient’s case to prior literature. This serves as an up-to-date literature review on the topic of invasive cardiac aspergillosis.

Keywords: aspergillus myocarditis, Angioinasive aspergillosis, Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Introduction

Invasive aspergillosis from one of several species of Aspergillus fungi is a well-described, common, and morbid disease in immunocompromised hosts [1]. Infective endocarditis from aspergillosis has also been extensively described, and is second only to Candida species as a fungal etiology of infective endocarditis [2]. However, myocarditis from aspergillosis, describing aspergillus invading into the parenchyma of the heart, has been very rarely described, and remains a notably uncommon manifestation of angioinasive aspergillosis [[3], [4], [5]].

What limited prior literature exists on aspergillosis myocarditis suggests that the host is invariable significantly immunocompromised and that outcomes are poor. Risk factors have included solid-organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy, high-dose glucocorticoids, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [[6], [7], [8]]. In prior reports, the presentation of aspergillosis myocarditis is variable, including cardiac tamponade5, myocardial infarction [[9], [10], [11], [12]], and complete heart block [12]. The clinical course is often fulminant and mortality exceeds 90%(8) and there are often concomitant widespread metastatic foci of infection. In the majority of published cases, the diagnosis of cardiac-invasive aspergillosis was not made until postmortem autopsy examination. Here, we describe the case of a patient who died as a result of aspergillosis myocarditis, and review prior literature on this morbid fungal infection.

Case report

A 60-year-old woman with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome) and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy presented with three weeks history of progressive exertional dyspnea and bilateral lower extremity swelling. Two years prior, in work-up for her dilated cardiomyopathy, a left heart catheterization revealed normal coronary arteries and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and myocardial biopsy revealed no specific etiology. Medications on admission were notable for albuterol, fluticasone-salmeterol, metoprolol succinate, spironolactone, and torsemide. Her social history was notable for previous employment as an artist making mobiles, minimal alcohol use, and no history of tobacco or recreational drug use. Family history was remarkable for a father who died of colon cancer.

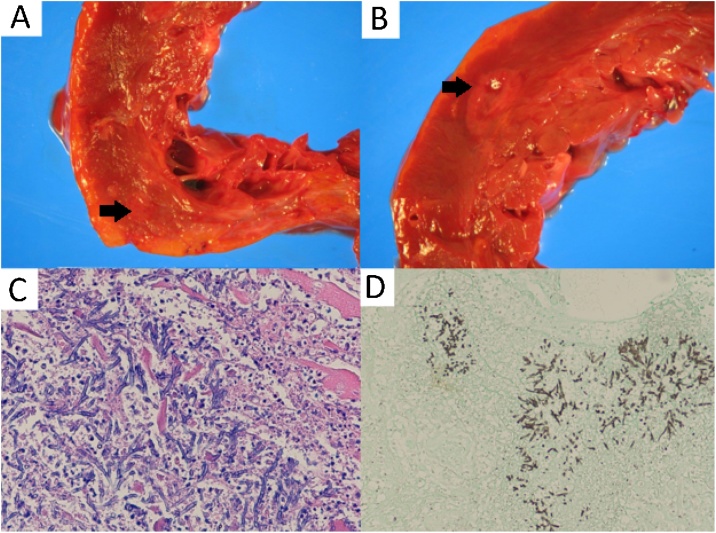

On initial presentation, vital signs were temperature 36.8 °C, blood pressure 93/55 mmHg, pulse 114 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Physical examination revealed tachycardia with normal heart sounds without appreciable murmur, normal work of breathing with clear lung fields, and 1+ bilateral lower extremity edema. Laboratory testing revealed white blood cell count of 7 × 103 cells/μL with a differential of 64% neutrophils, 18% lymphocytes, 11% monocytes, and 6% eosinophils. Hemoglobin was 12.8 g/dL, and platelet count was 262 × 103/ μL. Chest X-ray revealed cephalization of pulmonary vasculature, suggestive of hydrostatic pulmonary edema. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 15%, significantly reduced from one year prior (LVEF of 35%), without valvular vegetations or intracardiac abscesses. She was treated with diuretics and methylprednisolone 250 mg every six hours for suspected EGPA flare, with plan for repeat cardiac MRI. However, on hospital day three, she suffered an acute respiratory decompensation requiring endotracheal intubation. Chest X-ray revealed new left upper lobe infiltrates and bilateral pleural effusions, and she was started on ceftriaxone 1 g intravenous daily and azithromycin 500 mg orally daily for presumed community-acquired pneumonia. Bronchoscopy with alveolar lavage (BAL) showed no evidence of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and no overt evidence of infection. Infectious work-up including (1–3)-beta-d-glucan, urine antigens for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella, and blood and sputum cultures, was unrevealing. Given ongoing concern for EGPA flair, she was given rituximab 540 mg and corticosteroids were increased to methylprednisolone 1000 mg daily. She rapidly developed anuric renal failure and cardiogenic shock requiring inotropic support. Her condition continued to deteriorate and in consultation with her family, the decision was made to transition to a comfort-directed plan of care and she expired. The family requested autopsy, which revealed invasive myocarditis secondary to Aspergillus fumigatus as well as multiple myocardial abscesses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A, B: Gross photographs of coronal sections of the heart ventricles with myocardial abscesses (pale, soft regions with surrounding erythema indicated by arrows), C: Photomicrograph of edge of myocardial abscess (100x magnification) hematoxylin and eosin stain. Hyphae with 45-degree angle branching are seen, with acute inflammation and injured myocytes, D: Gomori Methenamine-Silver stain of lung tissue (100x magnification) that highlights fungal organisms with 45-degree angle branching, consistent with Aspergillus.

Discussion

We present the case of an unfortunate immunocompromised 60-year-old woman with EGPA who died of aspergillus myocarditis and pneumonia that was not diagnosed until after her death. Unfortunately, as this case demonstrates, afulminant fatal course and missed diagnosis pre-mortem is emblematic of the disease. We reviewed PubMed and identified 39 prior cases of aspergillus myocarditis. Results of literature review are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Published case reports of aspergillus myocarditis 1955–2019.

| Author | Year published | Number of Cases | Age: mean years (range) | % male / % female | % with positive blood cultures with Aspergillus | Case fatality rate | %pre-mortum diagnosis | Immunocompromising conditions (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh et al. [22] | 1955 | 1 | 18 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | Primary splenic neutropenia s/p splenectomy, corticosteroids |

| Fraumeni et al. [23] | 1962 | 1 | 41 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | Hematologic malignancy, corticosteroids, chemotherapy |

| Burke et al. [20] | 1970 | 1 | 51 | 100 / 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | corticosteroids, antimicrobials |

| Castleman et al. [21] | 1971 | 1 | 33 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | corticosteroids, antimicrobials |

| Williams et al. [3] | 1973 | 2 | 63 (60–66) | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | Chemotherapy, corticosteroids |

| Walsh et al. [25] | 1980 | 6 | 30 (16–61) | 0 / 100 | 0 | 100 | 16 (1/6) | Solid organ transplant, hematologic malignancy, corticosteroids |

| Ross et al. [10] | 1985 | 1 | 31 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | Hematologic malignancy |

| Andersson et al. [11] | 1986 | 3 | 34 (21–48) | 33 / 66 | 0 | 100 | 0 | Hematologic malignancy, chemotherapy |

| Rogers et al. [12] | 1990 | 1 | 69 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | corticosteroids, broad-spectrum antimicrobials |

| Carrel et al. [26] | 1991 | 1 | 68 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | corticosteroids |

| Cishek et al. [9] | 1996 | 1 | 40 | 0 / 100 | 0 | 100 | 0% | corticosteroidsand 6-MP |

| Rouby et al. [24] | 1998 | 1 | 75 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | corticosteroids, broad-spectrum antimicrobials |

| Xie et al. [8] | 2005 | 11 | 41 (29–62) | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 9% (1/11) | AIDS with CD4 T-cells 10-121 cells/uL |

| Kemdem et al. [4] | 2008 | 1 | 19 | 0 / 100 | 0 | 100 | 100% | corticosteroids, hematologic malignancy |

| Yano et al. [18] | 2010 | 1 | 74 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0% | None (tobacco use felt to be contributory) |

| Yoshino et al. [5] | 2013 | 2 | 79 (76–81) | 100 / 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | Hematologic malignancy, broad-spectrum antimicrobials |

| Dang-Tran et al. [7] | 2014 | 1 | 68 | 100 / 0 | 100 | 100 | 100% | Solid-organ transplant, corticosteroids |

| Kim et al. [19] | 2014 | 1 | 63 | 0 / 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | Aplastic anemia |

| Kupsky et al. [13] | 2016 | 1 | 18 | 100 / 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% | Solid-organ transplant |

| Bullis et al. | 2019 | 1 | 61 | 0 / 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | corticosteroids, Rituximab |

| Total | N/A | 39 | 45 (16–81) | 69 / 31 | 5 | 95 | 18 |

The majority of published cases of aspergillus myocarditis affected men and the median age was 41 (range 16–81) years old. Risk factors include chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy, glucocorticoids, and poorly-controlled AIDS - the latter of which was historically not considered a common association for invasive aspergillosis [15], but represented a significant percentage (28%) in this series. While widespread concomitant sites of infection were commonly observed, most had no pre-mortem suggestive cardiac imaging findings and only 18% were diagnosed pre-mortem. Aspergillus is rarely isolated from premortem blood cultures [8], which was observed in the Xie et al. series in which only 12% of cases had positive blood cultures. Aspergillus fumigatus was the most commonly observed species (44%), followed by A. flavus (38%), and A. terreus (5%). A fatal course was observed in 95% of cases.

Definitive diagnosis of disseminated aspergillosis requires culture from a normally sterile site with histopathologic evidence of tissue invasion. The galactomannan enzyme immunoassay (GM) tests for a polysaccharide component of the cell wall of Aspergillus spp. and can be used on both serum and BAL specimens as a diagnostic aid. The sensitivity and specificity of serum GM are 82% and 81%, respectively, and a galactomannan test is most useful in patients with hematologic malignancies or those who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [16,17]. A number of limitations exist including reduced sensitivity in patients on mold-active therapy, false positive results with use of certain antimicrobials such as piperacillin-tazobactam or those with graft-versus-host disease, and cross-reacting antigens with other fungal organisms (Fusarium, Penicillium, and Histoplasma). (1–3)-beta-d-glucan is another component of many fungal cell walls. Assaying for this antigen is non-specific and can be positive in many invasive fungal infections. The 1-3-beta-d-glucan assay can show false positive results in patients exposed to cellulose filters, those receiving intravenous immunoglobulin or albumin, or those with infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa [16]. Newer modalities to detect aspergillosis under study include detection via a monoclonal antibody of a mannoprotein produced only by actively growing Aspergillus spp., as well as a breath test for secondary metabolites using thermal-desorption-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, although the clinical utility of these tests remains to be proven.

A number of treatment options exist for management of invasive aspergillosis including triazoles such as voriconazole, amphotericin B, and echinocandins. Initial monotherapy with voriconazole has been shown in a large randomized, controlled trial to be superior with respect to survival and reduced adverse effects compared to amphotericin B [18]. Treatment duration of 6–12 weeks is the standard, however, this is based on low-quality evidence and a number of factors must be considered including degree of immunosuppression, disease site, and overall clinical trajectory [16]. Following treatment, secondary prophylaxis is warranted with subsequent periods of immunosuppression [17].

Conclusion

The present case highlights the diagnostic challenge of Aspergillus myocarditis as well as its fulminant nature and high mortality. Blood cultures are typically negative and isolation from sputum is often of unclear clinical significance. Non-invasive tests including serum galactomannan and (1–3)-beta-d-glucan assays are imperfectly sensitive and specific and a number of factors may cause false-positive results. Our patient’s poor outcome demonstrates that improved diagnostics are needed, and physicians caring for immunocompromised hosts must have a high index of suspicion for invasive aspergillosus in all its permutations.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interests

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

Authorship verification

All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and have contributed significantly to the work.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Patterson T. Bennett J, Dolin R, and Blaser M. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. updated edition. 8th ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2015. Aspergillus species; pp. 2895–2908. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis M., Al-Abdely H., Sandridge A., Greer W., Ventura W. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(1):50–62. doi: 10.1086/317550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams A. Aspergillus myocarditis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1974;61(2):247–256. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/61.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemdem A., Ahmad I., Ysebrand L., Nouar E., Silance P., Aoun M., Bron D., Vandenbossche J. An aspergillus myocardial abscess diagnosed by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21(10) doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.10.010. 1177.e3-1177.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshino T., Nishida H., Takita T., Nemoto M., Sakauchi M., Hatano M. A report of 2 cases of disseminated invasive aspergillosis with myocarditis in immunocompromised patients. Open J Pathol. 2013;03(04):166–169. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson R. Isolated cardiac aspergillosis after bone marrow transplantation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(11):1942–1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dang-Tran K., Chabbert V., Esposito L., Guilbeau-Frugier C., Dedouit F., Rostaing L. Isolated aspergillosis myocardial abscesses in a liver-transplant patient. Case Rep Transplant. 2014:1–3. doi: 10.1155/2014/418357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie L., Gebre W., Szabo K., Lin J. Cardiac aspergillosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(4):511–515. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-511-CAIPWA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cishek M., Schaefer S., Yost B. Cardiac aspergillosis presenting as myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 1996;19(10):824–827. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960191012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross E., Macher A., Roberts W. Aspergillus fumigatus thrombi causing total occlusion of both coronary arterial ostia, all four major epicardial coronary arteries and coronary sinus and associated with purulent pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56(7):499–500. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90904-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson B., Luna M., McCredie K. Systemic aspergillosis as cause of myocardial infarction. Cancer. 1986;58(9):2146–2150. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861101)58:9<2146::aid-cncr2820580931>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers J., Windle J., McManus B., Easley A. Aspergillus myocarditis presenting as myocardial infarction with complete heart block. Am Heart J. 1990;120(2):430–432. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90092-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupsky D., Alaswad K., Rabbani B. A rare case of aspergillus pericarditis with associated myocardial abscess and echocardiographic response to therapy. Echocardiography. 2016;33(7):1085–1088. doi: 10.1111/echo.13214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Heer K., Gerritsen M., Visser C., Leeflang M. Galactomannan detection in broncho-alveolar lavage fluid for invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(5):1–100. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012399.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patterson T., Thompson G., Denning D., Fishman J.A., Hadley S., Herbrecht R. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):1–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbrecht R., Denning D., Patterson T., Bennett J.E., Greene R.E., Oestmann J.W. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(25):2080–2081. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yano S. Dilated cardiomyopathy may develop in patients with Aspergillus infection. Respir Med CME. 2010;3(4):220–222. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H., Moon M., Lee J. Myocardial abscess, a rare form of cardiac aspergillosis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;107(6-7):415–417. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke B., Storring F., Parry T. Disseminated aspergillosis. Thorax. 1970;25(6):702–707. doi: 10.1136/thx.25.6.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabot R., Castleman B., McNeely B., Moellering R., Nash G. Case records of the Massachusetts general hospital: case 31-1971. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(6):337–346. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welsh R., Buchness J. Aspergillus endocarditis, myocarditis and lung abscesses: report of a case. Am J Clin Pathol. 1955;25(7):782–786. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/25.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraumeni J. Purulent pericarditis in aspergillosis. Ann Intern Med. 1962;57(5):823. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-57-5-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouby Y., Combourieu E., Perrier-Gros-Claude J., Saccharin C., Huerre M. A case of aspergillus myocarditis associated with septic shock. J Infect. 1998;37(3):295–297. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)92262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh T., Bulkley B. Aspergillus pericarditis: clinical and pathologic features in the immunocompromised patient. Cancer. 1982;49(1):48–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820101)49:1<48::aid-cncr2820490112>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrel T., Schaffner A., Schmid E., Schneider J., Bauer E.P., Laske A. Fatal fungal pericarditis after cardiac surgery and immunosuppression. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(1):161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]