Abstract

Objective

Advance care planning (ACP) is a core quality measure in caring for individuals with Parkinson disease (PD) and there are no best practice standards for how to incorporate ACP into PD care. This study describes patient and care partner perspectives on ACP to inform a patient- and care partner-centered framework for clinical care.

Methods

This is a qualitative descriptive study of 30 patients with PD and 30 care partners within a multisite, randomized clinical trial of neuropalliative care compared to standard care. Participants were individually interviewed about perspectives on ACP, including prior and current experiences, barriers to ACP, and suggestions for integration into care. Interviews were analyzed using theme analysis to identify key themes.

Results

Four themes illustrate how patients and care partners perceive ACP as part of clinical care: (1) personal definitions of ACP vary in the context of PD; (2) patient, relationship, and health care system barriers exist to engaging in ACP; (3) care partners play an active role in ACP; (4) a palliative care approach positively influences ACP. Taken together, the themes support clinician initiation of ACP discussions and interdisciplinary approaches to help patients and care partners overcome barriers to ACP.

Conclusions

ACP in PD may be influenced by patient and care partner perceptions and misperceptions, symptoms of PD (e.g., apathy, cognitive dysfunction, disease severity), and models of clinical care. Optimal engagement of patients with PD and care partners in ACP should proactively address misperceptions of ACP and utilize clinic teams and workflow routines to incorporate ACP into regular care.

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process that supports adults in understanding and sharing their values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care.1 ACP is associated with increased patient satisfaction and quality of life, fewer unwanted hospitalizations, and greater use of palliative care (PC) and hospice.2,3 In Parkinson disease (PD), advance discussion and planning that acknowledges future changes related to the illness may help affected patients and care partners focus on quality of life. Recognizing the importance of ACP as part of high-quality PD care, which includes documentation of care preferences in advance directives, the American Academy of Neurology Parkinson's Disease Updated Quality Measurement Set recommended patients with PD have an advance directive or designated medical power of attorney within the prior 12 months.4 Current care of individuals with PD does not routinely address ACP.5–9 In addition, given the high potential for loss of decision-making capacity, early ACP is important to ensure that end-of-life preferences are honored.10

ACP includes multiple steps such as identifying a surrogate decision-maker, discussing personal values, documenting preferences in an advance directive, and translating preferences into medical care plans, including out-of-hospital orders (i.e., POLST form).11,12 Published rates of advance directive completion or report of ACP conversations in individuals with PD varies, ranging from 68% to 95%, with the highest rate related to a study of proxy decision-making for patients with advanced PD.13–15 Because there are no best practice standards for integrating ACP as a core quality measure into neurologic care for individuals with PD, the objectives of this study are to elicit perspectives from patients and care partners on ACP to inform a patient- and care partner–centered framework for PD clinical care and research.

Methods

Design

This qualitative descriptive study leverages a large, multisite, randomized clinical trial of interdisciplinary outpatient neuropalliative care compared to standard neurologic care for individuals with PD and care partners. In the trial, patients and care partners, if care partners were available, were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to (1) standard care (includes a primary care provider and neurologist) or (2) outpatient, interdisciplinary team–based, PC augmenting standard care. This qualitative study includes 60 participants who were interviewed following the final data collection point at 12 months.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and participant consents

All participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site. The clinical trial identifier is NCT02533921.

Setting and participants

Study participants were drawn from 210 patients with PD and care partners from the University of Colorado, University of Alberta, and University of California San Francisco. Patients were included if they were fluent in English, over age 40, met UK Brain Bank criteria for a diagnosis of probable PD,16 and had moderate to high PC needs as assessed by the Needs Assessment Tool: Parkinson's Disease,17 a modified version of the Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool18 that includes PD-specific criteria including disease severity and motor and nonmotor symptoms (available upon request). For qualitative interviews, patients had to complete the 12-month visit. Patients were excluded if they had urgent PC needs, had another diagnosis requiring PC support (e.g., metastatic cancer), or were unwilling to comply with study procedures including randomization. Care partners were identified by asking the patient “Could you tell us the one person who helps you the most with your PD outside of the clinic?” Having a care partner was not a requirement for participation. Participants were compensated for participating in the randomized clinical trial, including for these 12-month visit interviews.

For this qualitative study, interviews were conducted between September 2017 and March 2018. During this period, 137 participants (81 patients and 56 care partners) had reached the 12-month visit. The study planned a goal of 60 interviews to allow sufficient opportunity to sample across trial sites and across participant type (patient or care partner). Patients and care partners were purposefully selected for interviews from each site, study arm, and sex to ensure representation across these populations. Other efforts to maximize the variance in the sample included specifically including individuals with cognitive impairment, high disease severity (based on Hoehn & Yahr score), or lacking a care partner. Importantly, patients and care partners were invited separately, rather than as a dyad. Thus, some patients participated independent of a care partner, and vice versa. All participants, whether a patient or care partner, were interviewed separately. Site investigators provided input to guide maximum variation sampling,19,20 including whether a patient or care partner was no longer appropriate for an interview. Fifty-three individuals were not contacted due to severe dementia, relocation to a long-term care facility, medical comorbidities such that the interview could be burdensome, deceased, dropped out, unable to be reached, or declined to participate (n = 4) due to time constraints or discomfort.

Data collection

An interview guide (available upon request) related to patient and care partner perspectives on ACP, including barriers and prior experiences, was developed and revised iteratively by the research team with input from the scientific literature, a multidisciplinary scientific advisory board with movement disorders and PC expertise, and a Parkinson's Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council (PDPFAC). The guide addresses experiences with ACP, planning for the future, planning in the context of potential future cognitive changes or dementia, and barriers related to ACP. The guide uses words, definitions, and descriptions of ACP that participants would be familiar with based on their geographic location. For example, words such as “goals of care designations” or “green sleeve” were used for Alberta, Canada, participants. The green sleeve holds a copy of a personal directive, a goals of care designation, and a tracking record.21 Likewise, out-of-hospital orders were referred to as POLST or Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment (MOST) forms for California and Colorado participants, respectively.22 The research team maintained detailed interview field notes that informed interview guide changes and refinement. Interviews lasted between 15 minutes and 2 hours and were completed over the telephone or via secure, video-assisted virtual calling. To help individuals with PD participate to the best of their ability, a one-page introduction of the interview topics was emailed to participants before the interview (available upon request). Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Patient and care partner sociodemographic characteristics, study participation details, self-report of PD-related characteristics, self-report by care partner of relationship to the patient, and other care partner characteristics were collected, and missing data account for fewer than 5% of demographic self-reported characteristics.

Data analysis

The analysis used a team-based, inductive, and deductive approach to identify key themes.23 Transcripts were de-identified with the exception of participant type (patient or care partner), study site, and study arm (PC or standard care) and read individually by each team member. A code book was defined and agreed upon, and 3 coders each coded roughly one-third of the data. Intercoder reliability was accomplished by continuous iterative consensus building with regular team meetings. The team examined the transcripts, codes in context, and emergent themes and meanings within and across all transcripts, and within and across study arm (PC or standard care), to extract meaningful content and determine relationships across the data. Meaningful content was then organized into themes that reflected participant perspectives and experiences related to ACP. Analytic decisions on emerging themes were tracked using an audit trail, reflexive team notes, and meeting minutes. Triangulation is a qualitative research strategy of using multiple methods or data sources to develop a comprehensive understanding to increase reliability of results.24 Triangulation was conducted by discussing early themes with the larger multidisciplinary team and the PDPFAC, as these individuals were involved in various aspects of the research study, are affected by PD, or read the interviews from a layperson's perspective.25 Informational saturation is a qualitative research determination where no new information was emerging. Reaching saturation is important in determining whether the research questions have been comprehensively explored. In this study, saturation occurred for the research questions and analysis related to ACP prior to completing the planned 60 interviews of clinical trial participants.26 Atlas.ti Version 7.5.18 software was used for data management.

Data availability statement

Anonymized data are available and will be shared upon reasonable request from any qualified investigator.

Results

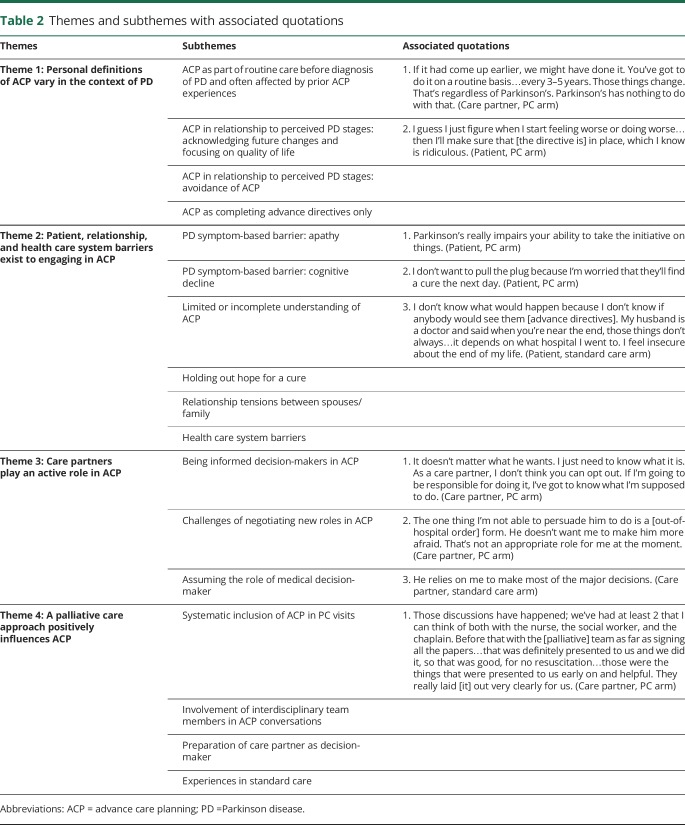

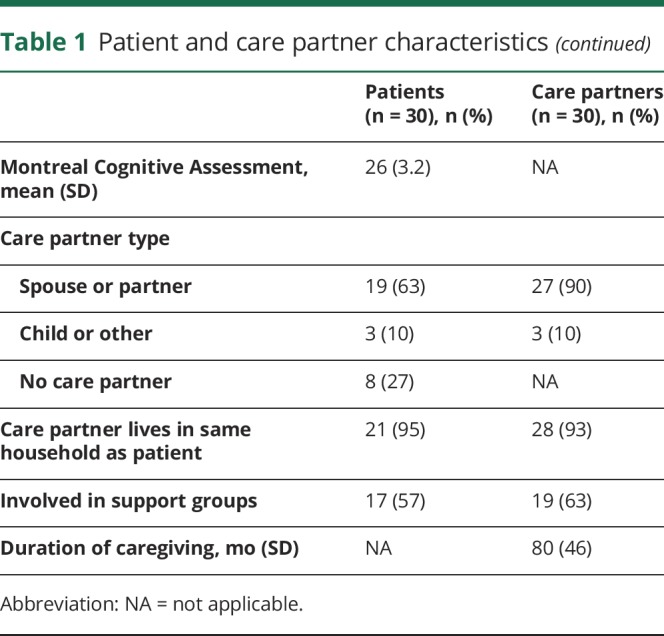

Sixty individuals were interviewed, including 30 patients and 30 care partners. There were 15 patient–care partner dyads and 30 participants who either did not have a care partner or were interviewed without inclusion of their respective care partner or patient. Participant characteristics, including sampling from each of the 3 sites, are presented in table 1. Although we attempted to interview patients with all levels of PD severity, those who were able to participate tended to have less severe Hoehn & Yahr level.

Table 1.

Patient and care partner characteristics

Synthesis of themes

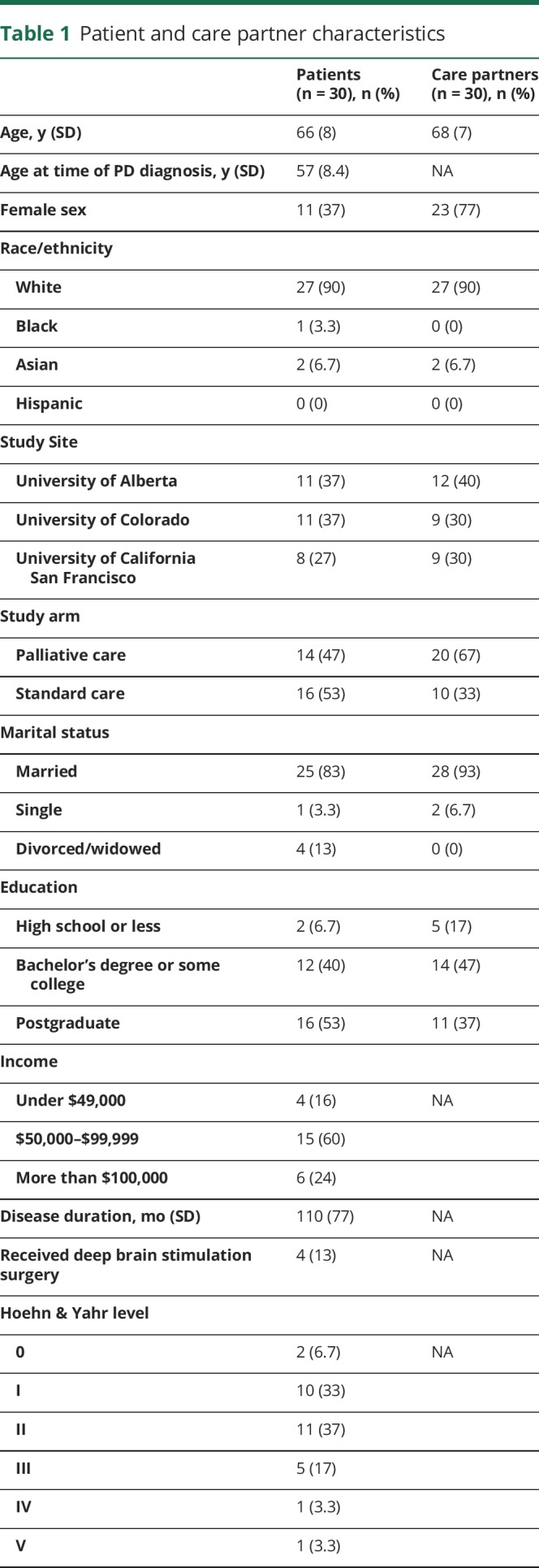

Four key themes emerged about opportunities and challenges that influence ACP for patients with PD and their care partners. The themes are (1) personal definitions of ACP vary in the context of PD; (2) patient, relationship, and health care system barriers exist to engaging in ACP; (3) care partners play an active role in ACP; and 4) a palliative care approach positively influences ACP. Table 2 summarizes the themes and subthemes that frame ACP in PD care. Taken together, patients had a variety of personal definitions of ACP and barriers to engaging in ACP that influenced whether they were willing to engage in ACP. Care partners had varying degrees of preparation and willingness to participate in ACP, but often still played an active role in ACP. Physician initiation of ACP discussions and interdisciplinary support in the context of outpatient neuropalliative care helped provide support and education for ACP conversations. Additional illustrative quotations are available in the e-appendix (doi.org/10.5061/dryad.t8m55vv). In each theme, the participants' perspectives on approaches to ACP did not vary by study site, study arm, or sex. Patient–care partner dyads did have related perspectives given their shared context; however, the participants' experiences, opinions, and responses were unique.

Table 2.

Themes and subthemes with associated quotations

Theme 1: Personal definitions of ACP vary in the context of PD

Patients and care partners affected by PD described a variety of personal definitions of ACP. These personal definitions or viewpoints were often shaped by their experience of PD or by other ACP or end-of-life experiences prior to PD diagnosis. The existence of these working definitions of ACP influenced their prior engagement in ACP, current willingness to discuss ACP, and were sometimes inaccurate or incomplete definitions of ACP compared to a traditional medical definition.

One personal definition of ACP was that it should be a part of routine care. Participants with this view of ACP often described engaging in ACP prior to their PD diagnosis because they had witnessed or were involved in someone else's end-of-life experience. Some participants who had ACP conversations before the time of PD diagnosis described the necessity and benefits of engaging in ACP on a routine basis. Others held personal definitions of ACP that acknowledged the potential for future PD-related changes; these individuals often chose to focus on ways to maximize their current quality of life given the uncertainties about future decline. For example, this view of ACP led to planning trips or enjoying activities that contributed to personal fulfillment. The emphasis on quality of life plans was often associated with engaging in ACP discussions and decisions about future medical care planning and documentation as part of routine medical care.

In contrast, some individuals considered ACP in relationship to their perception of their PD illness stage, but with an emphasis on avoiding ACP conversations. This personal definition of ACP described ACP as primarily end-of-life planning, and patients often perceived that ACP was unnecessary because they were not at that stage in the illness trajectory. While patients described worry, distress, or fear about PD-related changes, they still chose to avoid ACP conversations. Other participants had a personal definition of ACP that was very broad and focused especially on nonmedical planning; even when asked specifically about future medical care planning, participants instead described prioritizing planning for changes in living situations, finances, and caregiving needs. Finally, in contrast to ACP as a comprehensive process that includes multiple discussions, decisions, and documentation about ACP, some patients and care partners defined ACP as completing advance directives only and then believing that the document alone was sufficient. In these situations, having an advance directive present seemed to limit discussions about life values, and the rationale or implications of the ACP document.

Theme 2: Patient, relationship, and health care system barriers exist to engaging in ACP

Patients and care partners described multiple barriers to engaging in ACP that were related to their experiences of PD. These barriers were at the patient level, patient and care partner relationship level, and health care system level. At the patient level, PD-related symptoms were barriers to engaging in the ACP process. Specifically, apathy or being in a stuck place influenced patients' difficulties in discussing their values and documenting care preferences. Patients described lacking motivation or initiative to follow through with ACP actions, whereas they had been able to accomplish similar activities prior to having PD. In some cases, patients or care partners recognized that inability to engage in ACP was related to the presence of cognitive decline, as well as feeling overwhelmed by PD symptoms and disease progression. Another patient-level barrier to ACP was a limited or incomplete understanding of ACP. For example, patients made some choices for medical decisions about medical procedures like cardiopulmonary resuscitation or artificial nutrition without a complete understanding of the choices they were making and next steps to discuss with decision-makers or clinicians. A final patient-level barrier emerged where patients expressed difficulty making end-of-life decisions due to hoping that their PD would potentially be curable at the last minute. This sense of hope and denial of the potential for death due to PD prevented some patients and care partners from making concrete decisions about life-sustaining treatment or resuscitation.

At the patient and care partner level, relational issues between the patient and partner or family were another barrier. Both patients and care partners separately described the challenges of desiring to talk about future medical care planning but facing resistance from the other person. Others were concerned about protecting the emotional well-being of their partner, family members, or young children. For individuals who described this barrier, having care partners who were willing to play an active role in ACP and having interdisciplinary team-based approaches helped to navigate the tensions between a patient and care partner.

Finally, there were also health care system–level barriers, including patients' lack of trust that ACP preferences would be honored by clinicians or the health care system. Participants were concerned that regardless of prior documentation regarding ACP preferences for future medical care, their actual end-of-life situation was too dependent on the decisions of hospitals or clinicians. This perceived barrier was common among patients and care partners receiving standard care, though it also concerned PC arm participants.

Theme 3: Care partners play an active role in ACP

Both patients and care partners described specific roles that care partners played as active participants in the patient's ACP process. Instead of passively accompanying the patient, some care partners readily took on the role of being informed decision-makers. Patients expressed confidence in their care partners as decision-makers, trusting that the care partner would know what to do in the moment of a medical decision. Similarly, care partners who were chosen as medical decision-makers felt responsible for being informed about the patient's preferences.

Other care partners described challenges of negotiating new roles in ACP. In these cases, care partners navigated initiating ACP discussions and documentation, even when the patient was not ready to discuss ACP. For example, care partners recognized the patient's need for help with ACP but were unsure how much to encourage patients to talk about ACP when it seemed distressing or difficult. Some care partners identified their own personal feelings and preferences as influencing ACP and struggled with how to best respect the patient's unwillingness to discuss end-of-life preferences for quality of life and other decisions. These care partners expressed awareness that these decisions should be made by the patient but also that ultimately they would be responsible for making decisions in the future based on the patient's values and previously expressed wishes if the patient became incapacitated. Finally, some care partners described a transition to assuming the role as the patient's legally designated medical decision-maker. These care partners described needing to make current medical decisions as the health care agent and actively carry out their role based on previously completed advance directives when the patient no longer had the capacity to make decisions.

Theme 4: A palliative care approach positively influences ACP

Patients and care partners described the influence of PC on their experiences with ACP and planning for the future in the context of this neuropalliative care study. Many in the PC arm described receiving help with discussing preferences for their health care and completing advance directives. Two specific aspects of the PC approach were helpful to patients: (1) systematic and routine inclusion of ACP in PC visits with clear and open conversations and (2) involvement of trained interdisciplinary team members in facilitating ACP conversations. Participants described how these approaches were beneficial to not feeling alone and facilitating important conversations between care partners and patients. The PC approach often led to having a clear plan with tangible resources and guidance towards discussions and documentation, which ultimately gave them peace of mind. The PC approach also routinely included preparation of the care partner for their role as an informed medical decision-maker. Conversely, many in the standard care arm shared clinical experiences where ACP was poorly integrated into clinical care. For example, in standard care settings, some described lack of physician support for the ACP process, mixed messages about its necessity, and time constraints to discuss ACP in clinic visits. Among standard care patients, if an ACP conversation occurred, it was common for it to be a one-time conversation, often with lawyers and without medical input.

Discussion

This is the first study to identify opportunities and barriers to ACP from the perspectives of patients and care partners affected by PD. In acknowledgment of the role of ACP in improving consideration of patients' treatment preferences and goals of care, and data showing that patients in general (including those with PD) desire ACP discussions, the American Academy of Neurology Parkinson's Disease Updated Quality Measurement Set recommends that patients with PD have an advance directive or designated medical power of attorney completed within the prior 12 months.4 This study outlines opportunities to integrate ACP into clinical care through the recognition of patient, care partner, physician, and interdisciplinary team member characteristics (i.e., social worker, nurse, chaplain, others). Taken together, these findings describe key factors that influence how patients with PD and care partners engage in future medical planning discussions, and highlight the potential influence of a neuropalliative care approach on ACP.

Clinicians should initiate at least annual assessments of patient readiness to discuss ACP.11 In the context of PD, physicians should seek to understand the patient's or care partner's personal definition of ACP, barriers to ACP, and perceptions of individual PD trajectory. In this study, the most strongly positive examples of ACP were seen in patients who defined ACP as part of routine care, and often had engaged in ACP prior to their PD diagnosis. The experiences of these patients demonstrate the benefit of routinely assessing readiness for ACP and offering opportunities to have ongoing conversations about preferences for future medical care as an important systematic approach to engaging patients with PD and care partners in ACP.11,27 Routine integration is important because research has shown that in ambulatory health settings, physicians miss opportunities to initiate ACP discussions.28

Because personal definitions of ACP vary, there is a clear need for clinicians to assess the individual's understanding of ACP and provide patient and care partner education about the purpose of ACP. Many patients believed that ACP documents alone are sufficient and were reluctant to discuss the role of the decision-maker, potential PD-related changes with disease progression, prognosis, and the outcomes of potential medical treatments such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Individuals with PD have unique barriers to engaging in ACP that differ from barriers that affect the general population. PD can cause apathy and severe executive dysfunction that can limit decision-making capacity.29,30 In addition, dementia, depression, and psychosis are burdensome symptoms that can affect a patient's ability to participate in ACP. The clinician's role is to initiate ACP discussions early due to the high prevalence of future communication limitations and cognitive issues in PD,10 even if the patient or care partners are initially resistant.

A PC approach that includes routine exploration of ACP and quality of life preferences is an important aspect of patient and care partner engagement in ACP and may benefit from being integrated into primary care.9,31,32 PC is holistic, patient- and care partner–centered care that addresses physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and practical needs. Through its emphasis on effective communication skills in particularly difficult health-related conversations, PC can help identify personal definitions and barriers that may limit effective ACP. The variability in what information was desired and what decisions patients and care partners were ready to make demonstrates the importance of asking permission and eliciting current knowledge and needs for effective goals of care or ACP discussions.33 Neurologists can advocate for team-based and whole-person care that supports the patient and care partner to optimize ACP discussions, and clarifies that ACP discussions do not require an attorney.34

This study provides rich descriptions of ACP experiences from both patients with PD and care partners. In line with other ACP studies of seriously ill patients, we describe the nuanced, important, and challenging roles that care partners play as active participants in ACP, especially when patients faced barriers to ACP and preferred to postpone planning until a time of crisis.35,36 In such cases, many care partners recognized the need to participate as an informed decision-maker prior to a medical crisis, initiate honest conversations with their loved ones, and assist with ACP documentation. This study emphasizes engagement of care partners as participants who influence ACP for the person with PD. Because this study is in the context of a neuropalliative care study, this sample of care partners may be biased toward being prepared and willing decision-makers, though another survey of PD medical decision-makers also showed a preference for being involved in shared decision-making with family members and physicians.14

While other studies have suggested patient openness to early ACP, even at the time of PD diagnosis,15 our data show that some patients were reluctant to discuss ACP even in later stages of PD with moderate to high palliative needs. In this study, especially in the standard care arm, patients and some of their physicians did not feel that their PD illness stage, severity, or potential for future morbidity and mortality related to PD warranted a need for ACP.37,38 Physicians need to skillfully communicate about prognosis and provide education about common aspects of the PD illness trajectory for shared decision-making to occur.33,39 In addition, future studies should investigate cognitive impairment, spirituality, involvement of a care partner, involvement in a PD support group, or access to other support, as moderators of patient readiness for ACP.

This study has several limitations. While attempts were made to ease the burden of the phone interview, PD-related fatigue, dysarthria, and low speech volume affected patients with PD. In addition, some patients with PD described feeling anxious about what the detailed interview would consist of, and this could have influenced their ability to participate. Finally, while this qualitative study is large and aimed to include as much variation in patient and care partner perspectives as possible, the study population includes predominantly white, married, highly educated fluent English-speaking individuals, likely related to the referral patterns to the study. These clinical trial participants also may not be representative of persons not participating in clinical research.

This study describes PD patient and care partner perspectives on what influences or facilitates experiences related to ACP. Patients with PD and care partners describe unique definitions of ACP, barriers to ACP, roles of care partners in ACP, and the positive influence of a neuropalliative care approach on ACP engagement. This research adds suggestions for best practices to engage patients and families with PD in ACP. Patients with PD and care partners have unique barriers to ACP that may be overcome through ongoing discussions. Successful integration of ACP into neurologic practice can improve person-centered care as well as patient and care partner outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Parkinson's Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council stakeholders: Fran Berry, Anne Hall, Kirk Hall, Linda Hall, Carol Johnson, Patrick Maley, and Malenna Sumrall; and Laura Palmer, Etta Abaca, Francis Cheung, Jana Guenther, Claire Koljack, Chihyung Park, Stefan Sillau, and Raisa Syed for their assistance as part of the larger study team.

Glossary

- ACP

advance care planning

- PC

palliative care

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PDPFAC

Parkinson's Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council

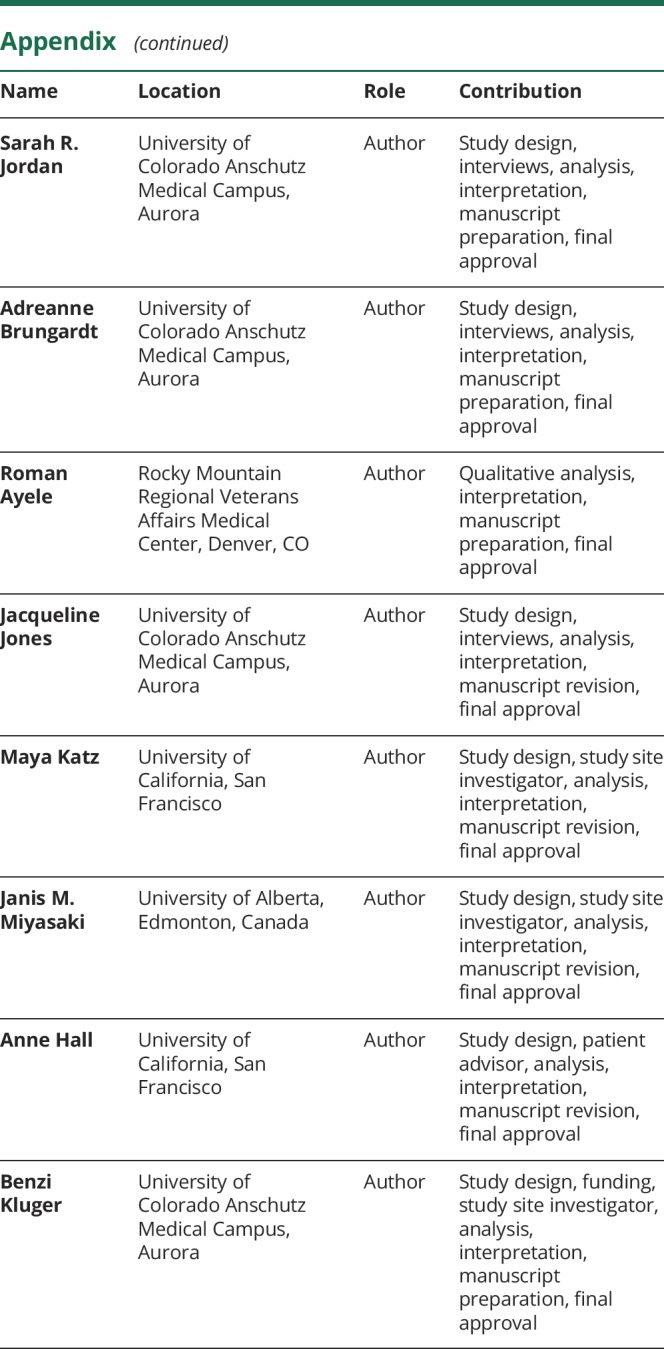

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 1039

Study funding

Research reported in this publication was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IHS-1408-20134) and by the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group funded by National Institute of Nursing Research U24NR014637. The statements presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Disclosure

H. Lum is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (K76AG054782). S. Jordan, A. Brungardt, R. Ayele, M. Katz, and J. Miyasaki report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. A. Hall reports receiving reimbursement for participating as a member of the PCORI-funded Parkinson's Disease Patient and Family Advisory Council. J. Jones and B. Kluger report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014;28:1000–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houben CH, Spruit MA, Groenen MT, Wouters EF, Janssen DJ. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Factor SA, Bennett A, Hohler AD, Wang D, Miyasaki JM. Quality improvement in neurology: Parkinson disease update quality measurement set: executive summary. Neurology 2016;86:2278–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanoix M. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: managing the chronic-palliative interface. Chronic Illn 2009;5:46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richfield EW, Jones EJ, Alty JE. Palliative care for Parkinson's disease: a summary of the evidence and future directions. Palliat Med 2013;27:805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu M, Cooper J, Beamish R, et al. How well do we recognise non-motor symptoms in a British Parkinson's disease population? J Neurol 2011;258:1513–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Martin P, Arroyo S, Rojo-Abuin JM, et al. Burden, perceived health status, and mood among caregivers of Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord 2008;23:1673–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyasaki JM, Kluger B. Palliative care for Parkinson's disease: has the time come? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2015;15:26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu Snineh M, Camicioli R, Miyasaki JM. Decisional capacity for advanced care directives in Parkinson's disease with cognitive concerns. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;39:77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lum HD, Sudore RL, Bekelman DB. Advance care planning in the elderly. Med Clin North Am 2015;99:391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Physicians Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm. Available at: polst.org/. Accessed July 26, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kluger BM, Persenaire MJ, Holden SK, et al. Implementation issues relevant to outpatient neurology palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwak J, Wallendal MS, Fritsch T, Leo G, Hyde T. Advance care planning and proxy decision making for patients with advanced Parkinson disease. South Med J 2014;107:178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuck KK, Brod L, Nutt J, Fromme EK. Preferences of patients with Parkinson's disease for communication about advanced care planning. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55:181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richfield E, Girgis A, Johnson M. Assessing Palliative Care in Parkinson's Disease - Development of the NAT: Parkinson's Disease. Palliat Med. 2014;28:540–913. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waller A, Girgis A, Currow D, Lecathelinais C. Development of the palliative care needs assessment tool (PC-NAT) for use by multi-disciplinary health professionals. Palliat Med 2008;22:956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research: purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997;26:623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trotter RT II. Qualitative research sample design and sample size: resolving and unresolved issues and inferential imperatives. Prev Med 2012;55:398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Advance Care Planning. Available at: myhealth.alberta.ca/Alberta/Pages/advance-care-planning-green-sleeve.aspx. Accessed November 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson CJ, Newman J, Tapper S, et al. Multiple locations of advance care planning documentation in an electronic health record: are they easy to find? J Palliat Med 2013;16:1089–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2010;5:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum 2014;41:545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320:50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sudore RL, Stewart AL, Knight SJ, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to detect behavior change in multiple advance care planning behaviors. PLoS One 2013;8:e72465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radakovic R, Davenport R, Starr JM, Abrahams S. Apathy dimensions in Parkinson's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018;33:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valentino V, Iavarone A, Amboni M, et al. Apathy in Parkinson's disease: differences between caregiver's report and self-evaluation. Funct Neurol 2018;33:31–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boersma I, Jones J, Carter J, et al. Parkinson disease patients' perspectives on palliative care needs: what are they telling us? Neurol Clin Pract 2016;6:209–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirk H, Malenna S, Gil T, Benzi MK. Palliative care for Parkinson's disease: suggestions from a council of patient and carepartners. NPJ Parkinson's Dis 2017;3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.You JJ, Fowler RA, Heyland DK; (CARENET) CRatEoLN. Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ 2014;186:425–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, Clayton JM. A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho GW, Skaggs L, Yenokyan G, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics related to completion of advance directives in terminally ill patients. Palliat Support Care 2017;15:12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fried T, Zenoni M, Iannone L. A dyadic perspective on engagement in advance care planning. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CDC/NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2015. LCWK9: Deaths, Percent of Total Deaths, and Death Rates for the 15 Leading Causes of Death: United States and Each State, 2015. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK9_2015.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Backstrom D, Granasen G, Domellof ME, et al. Early predictors of mortality in parkinsonism and Parkinson disease: a population-based study. Neurology 2018;91:e2045–e2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernacki RE, Block SD; Force ACoPHVCT. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data are available and will be shared upon reasonable request from any qualified investigator.