Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) due to chronic lung disease (Group 3 PH) have poor long-term outcomes. However, predictors of survival in Group 3 PH are not well described.

METHODS:

We performed a cohort study of Group 3 PH patients (n = 143; mean age 65 ± 12 years, 52% female) evaluated at the University of Minnesota. The Kaplan–Meier method and Cox regression analysis were used to assess survival and predictors of mortality, respectively. The clinical characteristics and survival were compared in patients categorized by PH severity based on the World Health Organization (WHO) classification and lung disease etiology.

RESULTS:

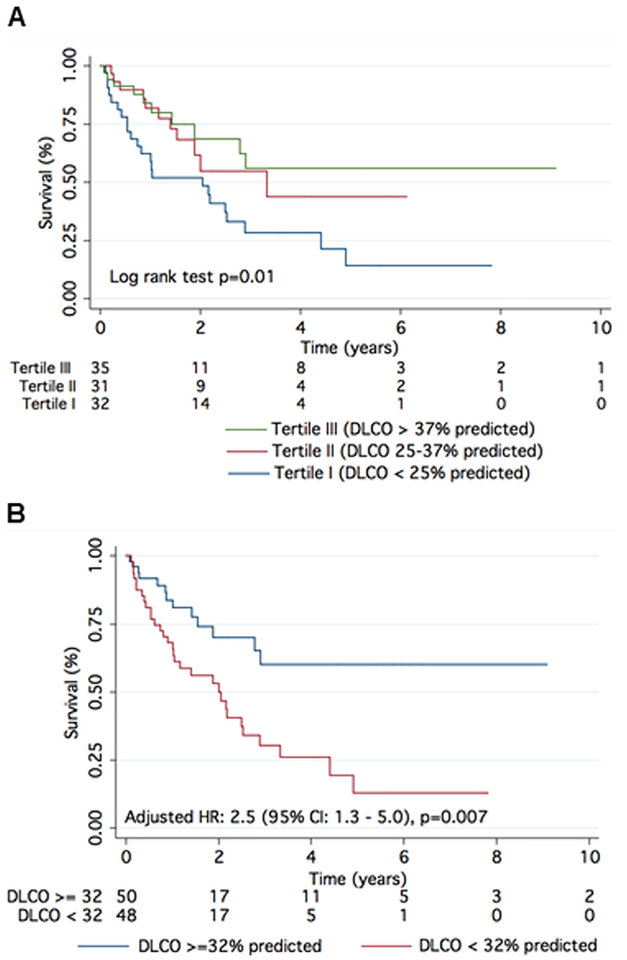

After a median follow-up of 1.4 years, there were 69 (48%) deaths. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 79%, 48%, and 31%. Age, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, Charlson comorbidity index, serum N-terminal pro‒brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), creatinine, diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO), total lung capacity, left ventricular ejection fraction, right atrial and right ventricular enlargement on echocardiography, cardiac index, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) were univariate predictors of survival. On multivariable analysis, DLCO was the only predictor of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] for every 10% decrease in predicted value: 1.31 [95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.47]; p = 0.003). The 1-/5-year survival by tertiles of DLCO was 84%/56%, 82%/44%, and 63%/14% (p = 0.01), respectively. On receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis, DLCO < 32% of predicted had the highest sensitivity and specificity for predicting survival. The 1- and 5-year survival in patients with a DLCO ≥ 32% predicted was 84% and 60% vs 68% and 13% in patients with a DLCO < 32% predicted (adjusted HR: 2.5 [95% confidence interval 1.3 to 5.0]; p = 0.007). Lung volumes and DLCO were not related, but higher PVR was strongly associated with reduced DLCO. There was increased mortality in interstitial lung disease‒PH as compared with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease‒PH, but PH severity based on the WHO classification did not alter survival.

CONCLUSIONS:

Low DLCO is a predictor of mortality and should be used to risk-stratify Group 3 PH patients.

Keywords: COPD, Emphysema, Interstitial lung disease, right ventricle, Cor pulmonale, pulmonary function test

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the setting of chronic lung disease or World Health Organization (WHO) Group 3 PH is the second most common cause of PH after left heart disease.1,2 Group 3 patients have a high symptom burden3 and poor long-term outcomes with a median survival of only 2 to 5 years after diagnosis.2,4–8 Furthermore, there are no approved treatments for Group 3 PH, and pulmonary vasodilator therapy does not improve exercise capacity or reduce symptom burden.9 Despite its high prevalence and mortality, little is known about the prognostic factors in Group 3 PH. The high prevalence, poor survival rates, and lack of treatment options in the Group 3 PH population make it critical to further define the prognostic indicators that could potentially lead to a novel therapeutic approach and improved outcomes.

The Fifth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension classified Group 3 patients into 2 categories based on hemodynamic criteria: mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) and cardiac index (mild PH: mPAP 25 to 34 mm Hg; severe PH: mPAP ≥ 35 mm Hg or mPAP ≥ 25 mm Hg and cardiac index: ≤ 2.0 liters/min/m2).10 These definitions are based on studies that showed patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and a mPAP ≥ 40 mm Hg had greater circulatory limitations to their exercise capacity than patients with mild PH.11 Likewise, those with interstitial lung disease (ILD) and a mPAP > 35 mm Hg have worse exercise capacity, lower diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and worse oxygenation as compared with those with mPAP ≤ 35 mm Hg independent of lung function.12,13 Although these definitions are based on clear functional differences, a comprehensive comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes of Group 3 patients with mild vs severe PH is lacking. Likewise, there are few comparisons of clinical characteristics and outcomes of Group 3 PH patients based on the etiology of the underlying chronic lung disease.

Accordingly, our aims in this study were to: (1) identify predictors of survival in Group 3 PH patients; (2) characterize the clinical phenotypes and survival differences between patients with mild and severe Group 3 PH; and (3) evaluate how the etiology of lung disease impacts patient profile and survival.

Methods

Study population

We identified adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) with Group 3 PH in the Minnesota Pulmonary Hypertension Repository (MPHR).14 This is a prospective registry initiated in 2014 to collect data on all consecutive PH patients treated at the University of Minnesota pulmonary hypertension center. Patients who received a diagnosis before March 2014 were entered retrospectively. All patients gave informed consent for participation in the MPHR. The University of Minnesota institutional review boards approved the MPHR. Group 3 PH was defined as mPAP ≥ 25 mm Hg at rest with a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≤ 15 mm Hg in patients with 1 or more of the following lung conditions in the absence of other etiologies to explain PH: (1) COPD, diagnosed by reduced expiratory flow rates (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC] < 70% predicted) and/or moderate to severe emphysema on a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest, as per the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) recommendations15; (2) ILD, as diagnosed by reduced total lung capacity (TLC) < 60% and/or evidence of moderate to severe interstitial fibrosis of lung parenchyma by CT scan of the chest; (3) combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE), based on CT scan of the chest and pulmonary function test; or (4) obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2)‒related lung disease, including obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed by overnight sleep study and obesity hypo-ventilation syndrome. Patients with Group 3 PH were divided into mild and severe Group 3 PH groups for analysis purposes. This categorization was based on the most recent WHO guideline definitions: mild PH (mPAP of 25 to 34 mm Hg); severe PH (mPAP ≥ 35 mm Hg or mPAP ≥ 25 mm Hg and low cardiac index ≤ 2.0 liters/min/m2).10

Covariates

The following baseline variables were analyzed at the time of referral for characterization of clinical phenotype: demographic data, including age and sex; smoking status; coexisting illnesses; WHO functional class; concomitant medications; pulmonary arterial hypetension (PAH)‒specific medications (prostacyclins, endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, warfarin and calcium channel blockers [CCBs]); baseline laboratory tests, including serum hemoglobin, serum creatinine, and serum N-terminal pro‒brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP); and assessment of exercise capacity by 6-minute walk test (6MWT). The Charlson comorbidity index was calculated, as described elsewhere,16 to quantify burden of medical complexity.

Pulmonary function test data were collected for all available patients (n = 117). The majority of the patients (81.2%) had their testing done at the University of Minnesota and met ATS criteria for acceptability and repeatability.17,18 Spirometry, lung volumes, and DLCO measurements were performed at the same time and location. DLCO was measured by the single-breath technique and was corrected for hemoglobin as recommended by the ATS/ERS.19 Of the 117 patients with pulmonary function test data, DLCO measurements were available for 98 patients (84%). The remaining 19 patients (16%) could not complete DLCO measurements. We did not collect carbon monoxide transfer coefficient data (DLCO/alveolar volume).

We collected data on the following baseline echocardiographic variables among available patients: left ventricular mass; left ventricular ejection fraction; presence of left or right atrial enlargement; right ventricular size; and pericardial effusion. Right ventricular size was semi-quantitatively described as normal size (two thirds or less of the left ventricular size), or as mildly (right ventricle similar size as the left ventricle size), moderately (right ventricle larger than the left ventricle), or severely enlarged (right ventricle much larger than the left ventricle), as previously described.20 We quantified right ventricular function by calculating right ventricular fractional area change (RVFAC).21 Right ventricular function was categorized as reduced if RVFAC was < 35%.22 Data on all echocardiographic variables were not available for some study patients due to unsatisfactory image quality (20%).

All patients being evaluated for PH in our clinic undergo right heart catheterization the University of Minnesota cardiac catheterization laboratory. The following hemodynamic variables were recorded at the end of expiration and the mean value derived from 3 beats was reported: right atrial pressure; right ventricular systolic and end-diastolic pressures; systolic pulmonary artery pressure; diastolic pulmonary artery pressure; mPAP; and PCWP. Cardiac output was determined as the mean of 3 measurements using the thermodilution method or indirect Fick method based on total body oxygen consumption estimated via the formula of LaFarge and Miettinen.23 Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was calculated in Wood units as the difference between mPAP and PCWP divided by cardiac output. The diastolic pressure gradient was calculated as the difference between diastolic pulmonary artery pressure and PCWP. Pulmonary arterial compliance (PAC) (ml/mm Hg) was calculated as the ratio of stroke volume to pulmonary artery pulse pressure.24 Acute vasodilator response was assessed during right heart catheterization with 80 parts per million (ppm) of inhaled nitric oxide for 5 minutes (n = 88). A positive vasodilator response was defined as a > 10 mm Hg decrease in mPAP to a value of < 40 mm Hg, with an unchanged or improved cardiac output. All hemodynamic assessments were performed at the cardiac catheterization lab at the University of Minnesota, except in 1 case where cardiac catheterization was performed the referring facility within 3 months of referral.

Vital statistics

All patients were followed regularly at the University of Minnesota PH clinic every 3 to 6 months. Vital statistics were obtained for all patients by chart review and Minnesota Death Index (MDI). For each death, the date and cause of death was collected. In all patients who were not identified as deceased using the MDI, it was possible to establish vital status by chart review.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are expressed as frequency and proportion, whereas continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as median with interquartile range (IQR). Unpaired t-test or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used to compare means of 2 groups with continuous variables. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare proportions for categorical variables. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, with entry into the study defined as the date of diagnostic right heart catheterization. The primary end-point was all-cause mortality. Patients were censored at lung transplantation or study completion (February 1, 2018). Between group survival was compared using the log-rank test. Univariate Cox proportional hazards analyses were performed with all baseline characteristic variables to determine the predictors of survival in patients with Group 3 PH. Variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were tested in stepwise forward Cox regression multivariable analyses to determine independent predictors of survival. The proportional hazards assumption was tested in all models. Functional capacity and 6-minute walk distance were highly correlated (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.3, p < 0.001). Hence, functional class alone was retained in the multivariable model to avoid collinearity. TLC was not included in the multivariable model to retain statistical power, as many patients did not have data on this parameter. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to define the most sensitive and specific cut-off values of DLCO for predicting mortality. To understand the determinants of DLCO, we performed uni- and multivariate linear regression analyses with DLCO as the dependent variable. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 143 patients with Group 3 PH were enrolled in our registry. PH was mild in 43 (30%) patients and severe in 100 (70%) patients. PH was associated with COPD (COPD-PH) in 53 patients (37%), ILD (ILD-PH) in 62 patients (43%), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in 14 patients (10%), and CPFE in 14 patients (10%). Clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic characteristics of the whole study cohort are summarized in Table 1. Of the 62 patients with ILD-PH, 14 (23%) had connective tissue disease: 2 had scleroderma; 2 had rheumatoid arthritis; 1 had polymyositis; 1 had dermatomyositis; 1 had mixed connective disease; and 1 had overlap of scleroderma, polymyositis, and dermatomyositis. The median follow-up time was 1.4 years (IQR 0.7 months to 3.0 years) with a maximum follow-up of 10.1 years. No patient was lost to follow-up. There were 69 (48%) deaths during the follow-up period. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 79%, 48%, and 31%, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical, Echocardiographic, and Hemodynamic Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Characteristics | Total cohort (n = 143) | Mild PH (n = 43) | Severe PH (n = 100) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65 ± 12 | 64 ± 12 | 65 ± 11 | 0.467 |

| Female, n (%) | 74 (52) | 22 (51) | 52 (52) | 0.927 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30 ± 7 | 30 ± 7 | 30 ± 7 | 0.985 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current or former smoker, n (%) | 106 (74) | 33 (77) | 73 (73) | 0.639 |

| Pack-years, n = 98 | 29 (15 to 46) | 25 (12 to 60) | 31 (15 to 43) | 0.619 |

| WHO functional class (n = 119), n (%) | 0.271 | |||

| II | 13 (11) | 6 (19) | 7 (8) | |

| III | 91 (76) | 23 (72) | 68 (78) | |

| IV | 15 (13) | 3 (9) | 12 (14) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 99 (69) | 31 (72) | 68 (68) | 0.627 |

| Diabetes | 40 (28) | 8 (19) | 32 (32) | 0.102 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 74 (52) | 20 (47) | 54 (54) | 0.411 |

| Coronary artery disease | 42 (30) | 9 (21) | 33 (33) | 0.146 |

| Atria I fibrillation | 28 (20) | 8 (19) | 20 (20) | 0.847 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 4.9 ± 2.6 | 5.0 ± 2.2 | 0.709 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| Oxygen | 89 (62) | 27 (63) | 62 (62) | 0.929 |

| Diuretics | 71 (50) | 20 (47) | 51 (51) | 0.623 |

| Digoxin | 12 (8) | 3 (7) | 9 (9) | 0.487 |

| Coumadin | 20 (14) | 6 (14) | 14 (14) | 0.994 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 27 (19) | 10 (23) | 17 (17) | 0.381 |

| Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors | 14 (10) | 4 (9) | 10 (10) | 0.583 |

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.512 |

| Prostacyclins | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| 6-minute walk test | ||||

| Distance, meters (n = 86) | 240 ± 104 | 287 ± 113 | 215 ± 92a | 0.002a |

| Rest oxygen saturation, % (n = 85) | 97 ± 2 | 98 ± 2 | 97 ± 3 | 0.051 |

| Nadir exercise oxygen saturation, % (n = 85) | 88 ± 5 | 88 ± 5 | 88 ± 5 | 0.906 |

| Baseline heart rate (beats/min) (n = 82) | 84 ± 16 | 85 ± 17 | 84 ± 16 | 0.828 |

| Peak heart rate (beats/min) (n = 82) | 117 ± 20 | 122 ± 21 | 116 ± 19 | 0.174 |

| Time taken for heart rate recovery, seconds | 119 ± 67 | 118 ± 66 | 120 ± 68 | 0.833 |

| Pulmonary function test, % predicted | ||||

| FEV1 (n = 117) | 54 ± 23 | 47 ± 21 | 57 ± 23a | 0.039a |

| FVC (n = 116) | 63 ± 22 | 59 ± 21 | 64 ± 23 | 0.235 |

| FEV1/FVC (n = 116) | 69 ± 20 | 67 ± 22 | 69 ± 19 | 0.602 |

| TLC (n = 78) | 80 ± 26 | 76 ± 28 | 81 ± 25 | 0.441 |

| DLCO (n = 98) | 36 ± 19 | 36 ± 19 | 35 ± 19 | 0.774 |

| Lab | ||||

| Serum hemoglobin, g/dl (n = 142) | 13.6 ± 2.1 | 13.1 ± 1.6 | 13.8 ± 2.3 | 0.086 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl (n = 142) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.1) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 0.482 |

| Serum NT-proBNP, pg/dl (n = 122) | 1,020 (245 to 3,270) | 295 (114 to 1,324) | 2,189 (425 to4,570)a | < 0.001a |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| Left ventricular EF, % (n = 135) | 60 ± 9 | 62 ± 5 | 60 ± 10 | 0.255 |

| Left ventricular mass index, g/m2 (n = 103) | 155 ± 55 | 163 ± 51 | 152 ± 57 | 0.379 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, cm (n = 119) | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 0.110 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm (n = 87) | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 0.146 |

| Right ventricular enlargement (n = 133) | 95 (71) | 17 (45) | 78 (82)a | <0.001a |

| Right atrial enlargement (n = 131) | 78 (60) | 14 (37) | 64 (69)a | 0.001a |

| Right ventricular FAC (n = 86) | 28 ± 10 | 34 ± 9 | 26 ± 10a | 0.001a |

| Right ventricular FAC < 35% (n = 86) | 58 (67) | 8 (35) | 50 (79)a | < 0.001a |

| Pericardial effusion (n = 133) | 12 (9) | 1 (3) | 11 (12) | 0.083 |

| TAPSE, cm (n = 91) | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.053 |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| Heart rate, beats/min (n = 119) | 78 ± 15 | 77 ± 14 | 79 ± 16 | 0.442 |

| Mean right atrial, mm Hg (n = 142) | 7 ± 4 | 5 ± 3 | 8 ± 5a | < 0.001 |

| Mean PAP, mm Hg (n = 143) | 40 ± 10 | 30 ± 3 | 44 ± 9a | < 0.001 |

| PCWP, mm Hg (n = 143) | 10 ± 3 | 10 ± 3 | 10 ± 3 | 0.667 |

| Cardiac output, liters/min (n = 142) | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 4.5 ± 1.5a | 0.011a |

| Cardiac index, liters/min/m2 (n = 138) | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.8a | 0.006a |

| PVR, Wood units (n −142) | 6.9 ± 3.4 | 4.1 ± 1.3 | 8.1 ± 3.3a | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic pulmonary gradient, mm Hg (n = 143) | 15 ± 8 | 10 ± 5 | 18 ± 8a | < 0.001a |

| PAC, ml/mm Hg (n = 118) | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 0.7a | < 0.001a |

| Vasodilator response, % (n = 88) | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 5 (7) | 0.583 |

Data are presented as number (%) for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation or median (25–75th percentiles) for continuous variables. Mild WHO Group 3 PH: mean pulmonary artery pressure < 35 mm Hg in the setting of chronic lung disease; severe WHO Group 3 PH: mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 35 mm Hg or ≥ 25 mm Hg in the presence of cardiac index < 2 liters/min/m2. PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; DLCO, diffusion lung capacity of carbon monoxide; EF, ejection fraction; FAC, fractional area change; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro‒brain natriuretic polypeptide; PAC, pulmonary arterial compliance; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TLC, total lung capacity; WHO, World Health Organization.

Indicates a significant difference between mild and severe Group 3 PH.

Predictors of survival in Group 3 PH

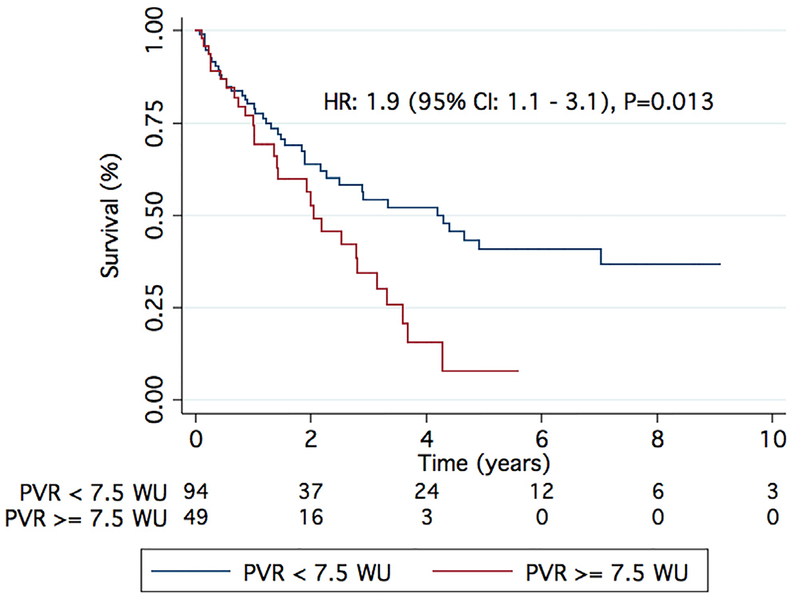

On univariate analysis, age, WHO Functional Class IV, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, Charlson comorbidity index, 6MWD, serum NT-proBNP and creatinine, DLCO, total lung capacity, left ventricular ejection fraction, right atrial and right ventricular enlargement on echocardiography, cardiac index, and PVR were the univariate predictors of survival (Table 2). On multivariable analysis, DLCO was the only independent predictor of survival after adjusting for all univariate predictors (Table 2). Each percent decrease in age and gender predicted value of DLCO was associated with a 4% increase in hazard of death (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.04 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.06]; p = 0.003). Every 10% decrease in age and gender predicted value of DLCO was associated with a 32% increase in hazard of death (adjusted HR 1.31 [95% CI 1.12 to 1.47]; p = 0.003). Survival by tertiles of DLCO is shown in Figure 1A. The 1- and 5-year estimated survival by tertiles of DLCO (highest, middle, and lowest) were 84%, 82%, and 63% (p = 0.01, log-rank test) and 56%, 44%, and 14% (p = 0.01, log-rank test), respectively. DLCO < 32% of predicted had the highest sensitivity and specificity for predicting survival, with an area under the curve of 0.74 on ROC analysis. One- and 5-year survival in Group 3 patients with a DLCO ≥ 32% predicted was 84% and 60%, respectively, as compared with 68% and 13%, respectively, in patients with a DLCO < 32% predicted (age, gender, and Charlson comorbidity index adjusted: HR 2.5 [95% CI 1.3 to 5.0]; p = 0.007) (Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Predictors of Mortality in Group 3 PH

| Characteristics | Univariate predictors Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariable predictorsa Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.57 (1.22 to 2.01) | < 0.001 | ||

| WHO FC IV | 2.31 (1.23 to 4.36) | 0.009 | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.88 (1.16 to 3.05) | 0.010 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.76 (1.02 to 3.01) | 0.040 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index (per unit increase) | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.21) | 0.041 | ||

| 6-minute walk distance (per 10-meter increase) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.009 | ||

| TLC (for every 10% decrease) | 1.21 (1.08 to 1.32) | 0.003 | ||

| DLCO (for every 10% decrease) | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.49) | < 0.001 | 1.31 (1.12 to 1.47) | 0.003 |

| Serum creatinine (per mg/dl increase) | 1.31 (1.03 to 1.66) | 0.029 | ||

| Serum NT-proBNP (per 100 pg/dl increase) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.006 | ||

| Left ventricle ejection fraction (per 1% decrease) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.05) | 0.020 | ||

| Right ventricular enlargement | 1.92 (1.05 to 3.53) | 0.035 | ||

| Right atrial enlargement | 2.16 (1.27 to 3.67) | 0.004 | ||

| Cardiac index (per liter/min/m2 decrease) | 1.36 (1.08 to 1.56) | 0.021 | ||

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (per 1 WU increase) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.19) | 0.005 |

CI, confidence interval; DLCO, diffusion lung capacity of carbon monoxide; FC, functional class; PH, pulmonary hypertension; TLC, total lung capacity; WHO, World Health Organization.

Adjusted for all characteristics associated with DLCO on univariate regression analysis with p < 0.05, other than 6-minute walk distance and TLC. Six-minute walk distance not included in the multivariable model, as there was multicollinearity with WHO FC. Hence, only WHO FC was retained in the multivariable model. TLC was not included in the multivariable analysis due to > 50% missing variables.

Figure 1.

Survival stratified by DLCO in Group 3 PH. (A) There was a linear relationship between survival and tertiles of DLCO in Group 3 PH. (B) DLCO of 32% predicted provides significant separation in survival in Group 3 PH. Age, gender, and Charlson comorbidity index adjusted HR: 2.5 (95% CI 1.3 to 5.0); p = 0.007.

Determinants of DLCO in Group 3 PH

On univariate regression analysis, reduced DLCO was associated with lower body mass index (Table 3). Obesity-related PH etiology was associated with higher DLCO. On echocardiography, lower left ventricular ejection fraction and lower left ventricular mass index were associated with reduced DLCO (Table 3). Importantly, there was no relationship between DLCO and lung volumes on pulmonary function testing, but reduced DLCO was associated with lower cardiac output and higher PVR, both hemodynamic measures of right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary vascular disease (Table 3). On multivariate linear regression with DLCO as the dependent variable, we found that lower body mass index and higher PVR were independently associated with reduced DLCO (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Determinants of DLCO on Univariate and Multivariable Regression Analysis Characteristics

| Univariate predictors | Multivariable predictorsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | β-coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Body mass index | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.8) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (0.3 to 1.7) | 0.004 |

| Obesity-related Lung disease | 20.6 (4.9 to 36.3) | 0.011 | ||

| Left ventricle ejection fraction | 0.5 (0.02 to 0.9) | 0.039 | ||

| Left ventricular mass | 0.1 (0.01 to 0.2) | 0.035 | ||

| Cardiac output | 3.4 (0.8 to 5.9) | 0.010 | ||

| Pulmonary vascular resistance | −1.4 (−2.5 to-0.3) | 0.011 | −1.5 (−2.7 to −0.2) | 0.020 |

Adjusted for all characteristics associated with DLCO on univariate regression analysis with a p < 0.05.

Mild vs severe Group 3 PH5

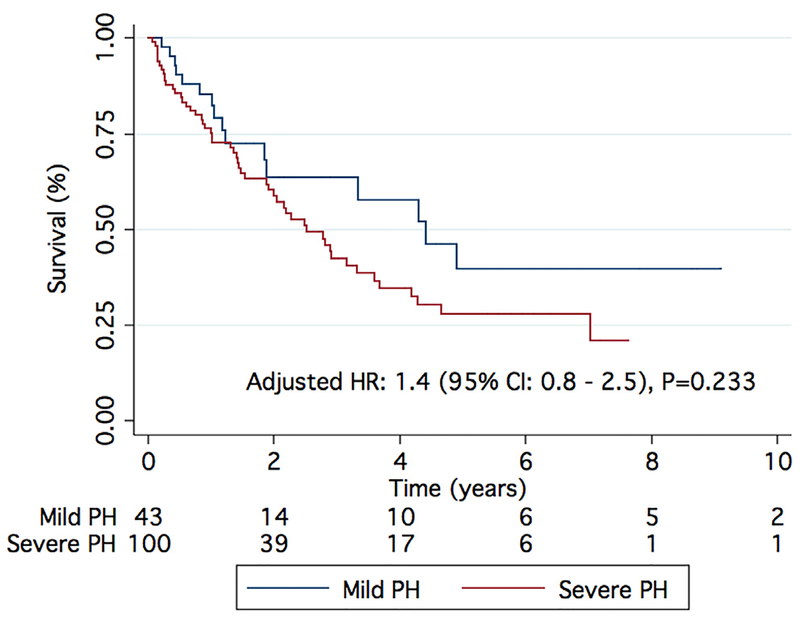

There was no difference in the etiology of underlying lung disease between patients with mild and severe Group 3 PH, nor did they differ in age, sex distribution, concomitant medical therapy, comorbidities, and Charlson comorbidity index (Table 1). However, patients with severe PH had a higher FEV1, shorter 6MWD, and lower resting oxygen saturation than those with mild PH, although they had similar oxygen desaturation with exercise (Table 1). There was no difference in DLCO between mild and severe PH groups (36 ± 19% vs 35 ± 19%, p = 0.774). NT-proBNP levels were significantly higher and, on echocardiographic analysis, more patients had right atrial enlargement, moderate to severe RV enlargement, and lower RVFAC in the severe Group 3 cohort. Severe PH patients had higher mPAP, PVR, diastolic pulmonary vascular gradient (DPG), and right atrial pressure with lower PAC and cardiac index than the mild PH cohort (Table 1). Despite the worse RV function and more severe PH, there was no difference in age-, gender-, and Charlson comorbidity index‒adjusted survival between patients with mild and severe Group 3 PH (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of survival between mild and severe Group 3 PH. There are no differences in survival after adjustment for age, gender, and Charlson comorbidity score between patients with mild and severe Group 3 PH.

Comparing Group 3 PH by etiology of lung disease

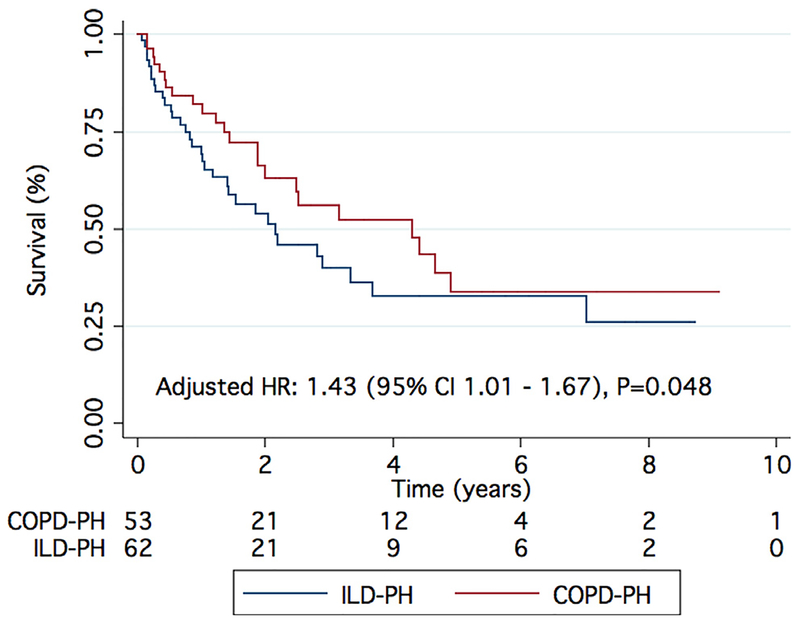

To further characterize the Group 3 population, we compared patients based on the etiology of their underlying lung pathology (Table 4). There were no significant differences in age, sex, WHO functional class, prevalence of comorbid conditions, Charlson comorbidity index, 6MWD, oxygenation during exertion, serum creatinine, or NT-proBNP between the Group 3 subgroups. Patients with COPD-PH had a higher pack-year smoking history when compared with patients with ILD-PH. CPFE patients had a higher serum hemoglobin than patients with COPD-PH and ILD-PH. As expected, body mass index was higher in the obesity-related PH group, and there were significant differences in FVC, FEV1/FVC, and TLC on pulmonary function tests between the groups (Table 4). Patients with ILD-PH and CPFE-PH had a significantly lower DLCO when compared with patients with obesity-related PH. There were no differences in echocardiographic characteristics between the different types of lung disease. On hemodynamic assessment, patients with CPFE had a significantly lower cardiac index when compared with COPD-PH patients (Table 4). Finally, there was lower age-, gender-, and Charlson comorbidity index‒adjusted survival in patients with ILD-PH when compared with COPD-PH patients (adjusted HR 1.43 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.67]; p = 0.048) (Figure 3). This difference in survival was lost when ILD-PH and CPFE-PH were grouped together and compared with patients with COPD-PH (see Figure S1 in Supplementary Material available online at www.jhltonline.org/). We did not compare survival in patients with obesity-related PH and CPFE-PH separately due to the small sample size.

Table 4.

Clinical and Hemodynamic Characteristics of Group 3 PH Based on Etiology of Chronic Lung Disease

| Characteristics | COPD(n = 53) | ILD (n = 62) |

0SA (n = 14) |

CPFE (n = 14) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67 ± 11 | 64 ± 12 | 59 ± 12 | 65 ± 11 | 0.120 | |

| Female, n (%) | 25 (47) | 38 (61) | 9 (64) | 2 (14) | 0.009 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29 ± 7 | 29 ± 7 | 38 ± 7a,b,f | 29 ± 5 | < 0.001 | |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Current or former smoker | 45 (85) | 38 (61) | 11 (79) | 11 (86) | 0.023 | |

| Pack-years, median (25—75th percentile), n = 98 | 42 (28 to 60)c | 20 (10 to 32) | 13 (6 to 40) | 20 (11 to 46) | < 0.001 | |

| WHO functional class, n (%) N = 119 | 0.762 | |||||

| I-II | 5 (11) | 6 (12) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | ||

| III-IV | 39 (89) | 45 (88) | 11 (85) | 11 (100) | ||

| Comorbidities %) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 37 (70) | 43 (69) | 9 (64) | 10 (71) | 0.982 | |

| Diabetes | 15 (28) | 15 (24) | 6 (43) | 4 (29) | 0.541 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 31 (59) | 27 (44) | 7 (50) | 9 (64) | 0.328 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 16 (30) | 17 (27) | 2 (14) | 7 (50) | 0.239 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13 (25) | 8 (13) | 2 (14) | 5 (36) | 0.159 | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 5.6 ± 2.7 | 4.6 ± 1.9 | 4.3 ± 2.2 | 4.7 ± 2.4 | 0.076 | |

| Medications, % | ||||||

| Oxygen | 33 (62) | 41 (66) | 4 (29) | 11 (79) | 0.039 | |

| Diuretics | 36 (68) | 22 (36) | 6 (43) | 7 (50) | 0.006 | |

| Digoxin | 3 (6) | 4 (7) | 1 (7) | 4 (29) | 0.076 | |

| Coumadin | 9 (17) | 6 (10) | 1 (7) | 4 (29) | 0.228 | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 10 (19) | 12 (19) | 2 (14) | 3 (21) | 1.000 | |

| Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors | 6 (11) | 6 (10) | 1 (7) | 1 (7) | 1.000 | |

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.490 | |

| 6-minute walk test | ||||||

| Distance, meters (n = 86) | 233 ± 110 | 244 ± 104 | 233 ± 91 | 237 ± 114 | 0.978 | |

| Rest oxygen saturation, % (n = 85) | 97 ± 2 | 98 ± 3 | 97 ± 1 | 97 ± 2 | 0.343 | |

| Nadir oxygen saturation, % (n = 85) | 88 ± 6 | 88 ± 5 | 90 ± 6 | 87 ± 4 | 0.841 | |

| Pulmonary function test, % | ||||||

| FEV1 (n = 117) | 44 ± 24c,e | 58 ± 18 | 49 ± 22 | 76 ± 24 | < 0.001 | |

| FVC (n = 116) | 68 ± 23 | 55 ± 18c | 50 ± 20 | 83 ± 23d,f | < 0.001 | |

| FEV1/FVC (n = 116) | 49 ± 16a,c,e | 81 ± 9 | 79 ± 19 | 70 ± 18 | < 0.001 | |

| TLC (n = 78) | 104 ± 21a,c,e | 64 ± 17 | 75 ± 28 | 78 ± 16 | < 0.001 | |

| DLC0 (n = 98) | 39 ± 24 | 32 ± 13 | 59 ± 17a,f | 31 ± 14 | 0.004 | |

| Lab | ||||||

| Serum hemoglobin (n = 142) | 13.3 ± 2.1 | 13.4 ± 2.1 | 13.7 ± 1.7 | 15.1 ± 2.5d,e | 0.029 | |

| Serum creatinine (n = 142) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 0.9 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.2) | 0.587 | |

| Serum NT-proBNP (n = 122) | 1,442 (254 to 2, | .832) 751 (223 to 3,200) | 484 (319 to 3,080) | 2,693 (893 to 3,480) | 0.570 | |

| Echocardiography | ||||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction,% (n = 135) | 61 ± 8 | 61 ± 11 | 62 ± 7 | 57 ± 8 | 0.466 | |

| Left ventricular mass, g (n = 103) | 155 ± 67 | 150 ± 47 | 169 ± 57 | 167 ± 20 | 0.739 | |

| Left atrial size, mm (n = 87) | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 0.915 | |

| Right ventricular enlargement, % (n = 133) | 37 (74) | 37 (64) | 9 (82) | 12 (86) | 0.333 | |

| Right atrial enlargement, % (n = 131) | 31 (63) | 29 (51) | 7 (58) | 11 (85) | 0.139 | |

| Right ventricular FAC, % (n = 86) | 28 ± 9 | 30 ± 12 | 29 ± 12 | 21 ± 7 | 0.303 | |

| Pericardial effusion, % (n = 133) | 5 (10) | 4 (7) | 3 (25) | 0 (0) | 0.163 | |

| TAPSE, cm (n = 91) | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.708 | |

| Hemodynamics | ||||||

| Heart rate, beats/min (n = 119) | 83 ± 15 | 76 ± 15 | 72 ± 20 | 81 ± 10 | 0.045 | |

| Mean right atrial pressure, mm Hg (n = 142) | 7 ± 4 | 7 ± 4 | 9 ± 6 | 7 ± 5 | 0.163 | |

| Mean PAP, mmHg (n = 143) | 40 ± 10 | 38 ± 9 | 40 ± 10 | 41 ± 11 | 0.602 | |

| PCWP, mmHg (n = 143) | 11 ± 3 | 9 ± 4 | 11 ± 3 | 9 ± 3 | 0.597 | |

| Cardiac output, liters/min (n = 142) | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 0.380 | |

| Cardiac index, liters/min/m2 (n = 138) | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.5e | 0.008 | |

| PVR, Wood units (n −142) | 6.9 ± 3.9 | 6.9 ± 3.1 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 7.8 ± 3.7 | 0.567 | |

| Diastolic pulmonary gradient, mm Hg (n = 143) | 15 ± 8 | 16 ± 13 | 14 ± 7 | 17 ± 7 | 0.730 | |

| PAC, ml/mm Hg (n = 118) | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 0.674 | |

| Vasodilator response, % (n = 88) | 2 (8) | 1 (2) | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | 0.296 | |

Data are presented as number (%) for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation or median (25–75th percentiles) for continuous variables. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPFE, combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema; DLCO, diffusion lung capacity of carbon monoxide; EF, ejection fraction; FAC, fractional area change; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ILD, interstitial lung disease; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro‒brain natriuretic polypeptide; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PAC, pulmonary arterial compliance; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TLC, total lung capacity; WHO, World Health Organization.

p < 0.05 for OSA-PH vs COPD-PH using Bonferroni’s post hoc test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

p < 0.05 for OSA-PH vs ILD-PH using Bonferroni’s post hoc test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

p < 0.05 for COPD-PH vs ILD-PH using Bonferroni’s post hoc test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

p < 0.05 for ILD-PH vs CPFE using Bonferroni’s post hoc test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

p < 0.05 for COPD-PH vs CPFE using Bonferroni’s post hoc test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

p < 0.05 for OSA-PH vs CPFE using Bonferroni’s post hoc test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Figure 3.

Comparison of survival between ILD-PH and COPD-PH. There is reduced survival in ILD-PH as compared with COPD-PH.

Discussion

We have shown that low DLCO identifies Group 3 PH patients at the highest risk of mortality. Every 10-unit decrease in DLCO is associated with a 31% increased risk of mortality. In addition, patients with DLCO < 32% predicted had a 2.5-fold increased hazard of mortality when compared to patients with DLCO ≥ 32% predicted. Our results differ slightly from those of Brewis et al, as DLCO was a predictor of mortality in the univariate analysis but not in the multivariate analysis.25 One possible explanation for the divergent results is the patient population analyzed. Brewis et al included only severe Group 3 PH, whereas we included patients with a broader spectrum of Group 3 PH severity. Although DLCO was not a multivariate predictor of mortality in the Brewis et al study, their results also suggest that low DLCO identifies Group 3 PH patients at increased risk of mortality. In the Hoeper et al study of 151 patients with PH secondary to chronic fibrosing idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis (PH-IIP), DLCO was not an independent predictor of mortality.26 Unlike Hoeper et al, who included only patients with PH-IIP, we studied patients with all etiologies of Group 3 PH, which may explain the differing observations. In addition, in the Hoeper et al study, TLC was the only lung function testing variable that was an independent predictor of mortality. In our study, TLC was a univariate predictor of mortality.

DLCO is an established predictor of mortality in Group 1 and Group 2 PH patients.27,28 The reduction in DLCO in our Group 3 PH cohort was greater when compared with the reduction in DLCO reported previously in Group 127 and Group 228 PH patients. This is likely a manifestation of both lung parenchymal and pulmonary vascular disease affecting DLCO in Group 3 PH. Although the risk of death associated with reduced DLCO in our Group 3 PH cohort was higher than our previously published risk of death in Group 1 PH (39% vs 20%),27 it is lower than the risk of death reported by Hoeper et al in Group 2 PH (39% vs 60%).28 Moreover, impaired DLCO is associated with increased mortality in ILD patients without definitive PH.29 Thus, it is likely that DLCO provides an integrated measure of cardiopulmonary limitations, reflecting loss of alveolar surface areas as well as reduced microvascular bed. Future studies investigating low DLCO in Group 3 PH may yield a more mechanistic understanding in Group 3 PH and possible therapeutic targets moving forward.

Although both parenchymal lung disease and pulmonary vascular disease can decrease DLCO due to loss of alveolar‒capillary surface area and loss of pulmonary capillary surface area,30 respectively, our data suggest that DLCO is, at least in part, a surrogate marker for pulmonary vascular disease rather than parenchymal lung disease in patients with Group 3 PH. Consistent with this, in our cohort, PVR was significantly associated with DLCO, yet there was no relationship between lung volumes (FEV1, FVC, and TLC) and DLCO. Another possibility is that DLCO is a reflection of pulmonary venous remodeling, as it is reduced in pulmonary venous hypertension.28 However, we did not observe a link between elevated pulmonary venous pressures and DLCO, as the correlation between DLCO and PCWP (β-coefficient 1.01 [95% CI ‒0.20 to 2.24]; p = 0.101) in our cohort was not significant. Unfortunately, we did not have detailed pulmonary venous assessment on our lung CT scans to investigate this possibility further.

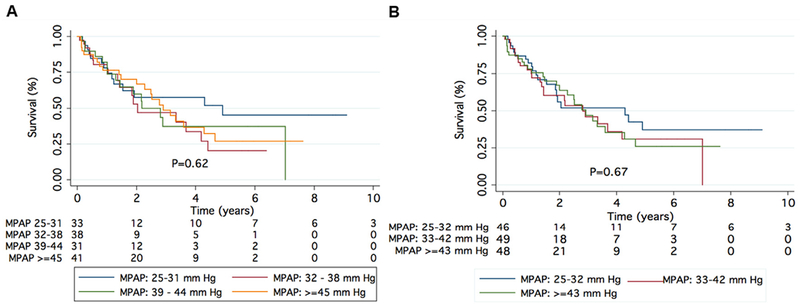

As expected, severe Group 3 PH patients have a higher burden of pulmonary vascular disease, greater RV dysfunction, and worse exercise capacity as compared with patients with mild Group 3 PH, but there are no differences in demographics or other clinical characteristics, including co-morbidities and concomitant medication use. It is unclear why some patients with chronic lung disease develop severe intrinsic pulmonary vascular disease while others do not. Although Group 3 PH patients with mPAP > 35 mm Hg have more cardiopulmonary limitations with exercise11–13 than those with less severe hemodynamic compromise, this is not associated with increased mortality. This is true both when we analyzed mPAP as a continuous variable (HR 1.01 [0.98 to 1.04]; p = 0.441; Table 4) and in tertiles or quartiles (Figure 4A and B), consistent with findings by Corte et al.31

Figure 4.

Survival in Group 3 PH by tertiles (A) and quartiles (B) of mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP). There was no difference in survival when the Group 3 PH cohort was divided into tertiles and quartiles of mPAP.

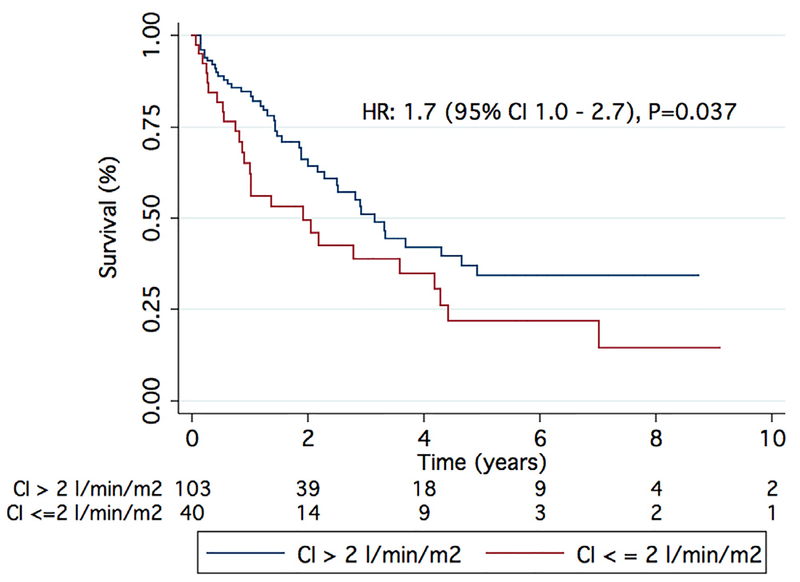

We have also shown that elevated PVR (HR 1.11 [95% CI 1.03 to 1.19]; p = 0.005; Table 4) and low cardiac index (HR 1.36 [95% CI 1.08 to 1.56]; p = 0.021; Table 4) were the only hemodynamic variables associated with worse survival in Group 3 PH, albeit only as univariate predictors. This is consistent with the results of Corte et al, who found that patients with diffuse lung disease and a PVR of > 6.23 Wood units have a worse 1-year survival than those with a PVR < 6.23 Wood units.31 In our cohort, patients with a PVR in the highest tertile (PVR ≥ 7.5 Wood units) had worse survival compared with those with PVR < 7.5 Wood units (Figure 5), and those with a cardiac index in the lowest tertile (< 2 liters/min/m2) had a higher mortality than those with a cardiac index of > 2 liters/min/m2 (Figure 6). Perhaps PVR and cardiac index are better hemodynamic markers than mPAP for categorizing patients with Group 3 PH.

Figure 5.

Elevated PVR is associated with increased mortality in Group 3 PH. A PVR of > 7.5 Wood units resulted in increased mortality as compared with a PVR of < 7.5 Wood units.

Figure 6.

Low cardiac index was associated with increased mortality in Group 3 PH. A cardiac index of < 2 liters/min/m2 resulted in increased mortality as compared with a cardiac index of > 2 liters/min/m2.

In our cohort, ILD-PH patients had only slightly worse survival than COPD-PH patients (Figure 2). This differs somewhat from findings observed in 2 European Registry studies. First, Brewis et al showed ILD-PH was associated with much worse survival than COPD-PH in the Scottish Pulmonary Vascular Unit Center Group 3 PH cohort.25 Moreover, Gall et al demonstrated ILD-PH patients had significantly worse survival than COPD-PH patients in the Giessen Pulmonary Hypertension Registry.5 A potential explanation for the modest differences between our results and those of Brewis et al and Gall et al could be the degree of adverse pulmonary vascular remodeling at the time of referral. Because we (see Figure 5) and Corte et al31 showed elevated PVR is associated with increased mortality in Group 3 PH, differences in PVR at the time of referral may help explain the divergent survival observations. ILD-PH patients in the study by Brewis et al had a higher PVR than our ILD-PH cohort (10.0 ± 3.0 vs 6.9 ± 3.1 Wood units). Moreover, our COPD-PH population had a wider PVR range than the Giessen COPD-PH population (median [IQR]: 5.8 [3.2] vs 5.2 [3.1] Woodunits). Thus, the higher PVR in ILD-PH patients from the Brewis et al study and the lower PVR in COPD-PH patients from the Gall et al study may explain why they observed larger differences in survival between COPD-PH and ILD-PH than we did.

Although not proven to be effective,9 many centers use PAH-specific therapy in Group 3 PH.32 At our center, patients with Group 3 PH are not routinely treated with pulmonary vasodilator therapy. Of the 143 patients in our cohort, only 15 patients received pulmonary vasodilator therapy. In these 15 patients, pulmonary vasodilator therapy had no effect on DLCO (baseline DLCO vs DLCO at 1 year on pulmonary vasodilator therapy: 31 ± 14% predicted vs 29 ± 14% predicted, p = 0.264). Finally, patients were on CCBs for other clinical indications, such as coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, or hypertension, and not for vasoreactivtiy. Therefore, we could not assess the effect CCBs have on DLCO.

Limitations

The MPHR is a single-center, longitudinal, observational study with data collection that started in 2014. Thus, many of the patients were entered retrospectively into the database. However, the MPHR is one of the largest studies to comprehensively describe the clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic characteristics and long-term outcomes in patients with Group 3 PH. In addition, we collected baseline variables at the time of the original referral to our practice instead of the variables at the time of enrollment in the registry. This approach reduced survival bias. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in clinic characteristics and outcomes between the incident and the prevalent cohort (data not presented). We lacked data for some of the variables, which could have affected our multivariate analysis. Next, our study grouped different etiologies of Group 3 PH together. To address this, we compared clinical characteristics and survival based on the etiology of the underlying chronic lung disease (Table 4 and Figure 3). A similar approach has been used in patients with WHO Group 1 PAH, who also differ in clinical characteristics and survival based on the underlying etiology of the disease.33,34 Finally, most of the Group 3 patients had severe PH, and thus our data reflect referral bias to an academic PH program and are not representative of a population-based Group 3 PH cohort.

In conclusion, in Group 3 patients, DLCO is a major indicator of mortality and in the future could be useful for identifying the highest risk Group 3 patients. Severe Group 3 patients have more cardiac impairment, but long-term survival between mild and severe Group 3 PH patients is equivalent. Finally, there is a tendency toward poorer survival in ILD-PH compared with COPD-PH.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. TT received modest honorarium from Gilead sciences and Acte-lion for serving on the advisory board. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH F32 HL129554 and NIH K08 HL140100 to K.W.P., and NIH RO1 HL113003 to SLA); the Canada Foundation for Innovation (229252 and 33012 to SLA); a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Mitochondrial Dynamics and Translational Medicine (950–229252 to SLA); the William J Henderson Foundation to SLA; and the American Heart Association (Scientist Development Grant 15SDG25560048 to T.T.).

Footnotes

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at www.jhltonline.org/.

References

- 1.Strange G, Playford D, Stewart S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: prevalence and mortality in the Armadale echocardiography cohort. Heart 2012;98:1805–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijeratne DT, Lajkosz K, Brogly SB, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of World Health Organization Groups 1 to 4 pulmonary hypertension: a population-based cohort study in Ontario. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e003973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barberà JA, Blanco I. Gaining insights into pulmonary hypertension in respiratory diseases. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prins KW, Rose L, Archer SL, et al. Disproportionate right ventricular dysfunction and poor survival in group 3 pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197:1496–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gall H, Felix JF, Schneck FK, et al. The Giessen Pulmonary Hypertension Registry: survival in pulmonary hypertension subgroups. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:957–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen KH, Iversen M, Kjaergaard J, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and survival in pulmonary hypertension related to end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura M, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a prognostic indicator at the initial evaluation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration 2013;85:456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lettieri CJ, Nathan SD, Barnett SD, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2006;129:746–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prins KW, Duval S, Markowitz J, et al. Chronic use of PAH-specific therapy in World Health Organization group III pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulm Circ 2017;7:145–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seeger W, Adir Y, Barberà JA, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:D109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boerrigter BG, Bogaard HJ, Trip P, et al. Ventilatory and cardiocirculatory exercise profiles in COPD: the role of pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2012;142:1166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minai OA, Santacruz JF, Alster JM, et al. Impact of pulmonary hemo-dynamics on 6-min walk test in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2012;106:1613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boutou AK, Pitsiou GG, Trigonis I, et al. Exercise capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the effect of pulmonary hypertension. Respirology 2011;16:451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prins KW, Weir EK, Archer SL, et al. Pulmonary pulse wave transit time is associated with right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 2016;6:576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celli BR, MacNee W, Force AET. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23:932–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culver BH, Graham BL, Coates AL, et al. Recommendations for a Standardized Pulmonary Function Report. An official American Thoracic Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1463–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. Executive summary: 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2017;49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammed SF, Hussain I, AbouEzzeddine OF, et al. Right ventricular function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. Circulation 2014;130:2310–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39. e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaFarge CG, Miettinen OS. The estimation of oxygen consumption. Cardiovasc Res 1970;4:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahapatra S, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, et al. Relationship of pulmonary arterial capacitance and mortality in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brewis MJ, Church AC, Johnson MK, et al. Severe pulmonary hyper-tension in lung disease: phenotypes and response to treatment. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1378–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoeper MM, Behr J, Held M, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with chronic fibrosing idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandra S, Shah SJ, Thenappan T, et al. Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010;29:181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoeper MM, Meyer K, Rademacher J, et al. Diffusion capacity and mortality in patients with pulmonary hypertension due to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:441–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamada K, Nagai S, Tanaka S, et al. Significance of pulmonary arterial pressure and diffusion capacity of the lung as prognosticator in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;131:650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes JM, Pride NB. Examination of the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DL (CO)) in relation to its KCO and VA components. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corte TJ, Wort SJ, Gatzoulis MA, et al. Pulmonary vascular resistance predicts early mortality in patients with diffuse fibrotic lung disease and suspected pulmonary hypertension. Thorax 2009;64:883–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trammell AW, Pugh ME, Newman JH, et al. Use of pulmonary arterial hypertension-approved therapy in the treatment of non-group 1 pulmonary hypertension at US referral centers. Pulm Circ 2015;5:356–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 2010;122:164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weatherald J, Boucly A, Chemla D, et al. Prognostic value of follow-up hemodynamic variables after initial management in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2018;137:693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.