Abstract

The low-level endo-lysosomal signaling lipid, phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2), is required for full assembly and activity of vacuolar H+-ATPases (V-ATPases) containing the vacuolar a-subunit isoform Vph1 in yeast. The cytosolic N-terminal domain of Vph1 is also recruited to membranes in vivo in a PI(3,5)P2-dependent manner, but it is not known if its interaction with PI(3,5)P2 is direct. Here, using biochemical characterization of isolated yeast vacuolar vesicles, we demonstrate that addition of exogenous short-chain PI(3,5)P2 to Vph1-containing vacuolar vesicles activates V-ATPase activity and proton pumping. Modeling of the cytosolic N-terminal domain of Vph1 identified two membrane-oriented sequences that contain clustered basic amino acids. Substitutions in one of these sequences (231KTREYKHK) abolished the PI(3,5)P2-dependent activation of V-ATPase without affecting basal V-ATPase activity. We also observed that vph1 mutants lacking PI(3,5)P2 activation have enlarged vacuoles relative to those in WT cells. These mutants exhibit a significant synthetic growth defect when combined with deletion of Hog1, a kinase important for signaling the transcriptional response to osmotic stress. The results suggest that PI(3,5)P2 interacts directly with Vph1, and that this interaction both activates V-ATPase activity and protects cells from stress.

Keywords: vacuolar ATPase; vacuole; phosphatidylinositol signaling; Saccharomyces cerevisiae; proton pump; lysosome; acidification; osmoregulation; osmotic stress; phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate

Introduction

Organelles of the secretory and endocytic pathway perform distinct and compartmentalized functions, many of which are dependent on their luminal pH (1, 2). Luminal pH varies widely. Vacuoles/lysosomes are the most acidic organelles, but the Golgi network, endosomes, and regulated secretory granules are also acidic relative to the cytosol (3, 4). Importantly, pH of these organelles is not static, but rather, dynamic and finely tuned by the coordinate action of pumps and exchangers, and this fine-tuning of their pH is critical to their function (3). Vacuolar H+-ATPases (V-ATPases)2 are highly conserved, multisubunit ATP-driven H+ pumps responsible for organelle acidification (5). In higher organisms V-ATPases are essential for early development and complete loss of function is embryonic lethal (6). Partial or isoform-specific loss of function in different tissues can cause rare congenital human diseases, such as distal renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness (7), osteopetrosis (8, 9), cutis laxa (10), and infertility (11). A pathogenic gain of V-ATPase function is implicated in cancer (12), liver cirrhosis (13), and osteoporosis (14). In addition, V-ATPases regulate the mTORC1, AMP-activated protein kinase, Notch-Delta, and Wnt signaling pathways (15). V-ATPases are composed of a cytosolic V1 domain that contains sites of ATP hydrolysis and a membrane-bound Vo domain that performs H+ translocation (15). In response to intra- and extracellular cues, the V-ATPase can undergo reversible disassembly into inactive V1 and Vo sectors (5). The absolute level of V1-Vo assembly is plastic and can be modulated by different signals, providing condition-specific levels of enzyme activity (16).

All V-ATPase subunits are encoded by single VMA genes in yeast, except for the transmembrane a-subunit of the Vo sector, which is present as two compartment-specific isoforms, Vph1 and Stv1 (17). Vph1 and Stv1 assemble two populations of V-ATPases that vary only in their a-subunit isoform. At steady state, Vph1 localizes to the vacuole and Stv1 localizes to the Golgi network (18). All V-ATPase a-subunits, including Stv1 and Vph1, are predicted to have a similar overall structure, with a cytosolic N-terminal domain (NT) and a C-terminal domain containing multiple transmembrane helices (19, 20). Recent cryo-EM structures of both intact Vph1-containing V-ATPases and isolated Vo complexes indicate that Vph1-NT adopts a dumbbell shape, with two globular domains (designated proximal and distal) connected by a coiled coil (20, 21).

Phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP) lipids help define the identity of many organelles in eukaryotes and act by recruiting peripheral proteins to membranes or changing the conformation of integral membrane proteins (22, 23). PI(4,5)P2 in the plasma membrane and PI(4)P in the Golgi/plasma membrane are the two most abundant PIP lipids in eukaryotes (22). PI(3,5)P2 is a scarce signaling lipid present in the endo/lysosomal system (24). Despite its low abundance, loss of PI(3,5)P2 causes human diseases such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome and ALS (24). PI(3,5)P2 is implicated in glutamate receptor recycling in the mammalian brain, regulation of mTORC1 signaling, autophagy, and activation of ion channels in the endo-lysosome (24–27). Hyperosmotic stress, in both yeast and mammals, raises PI(3,5)P2 levels by about 20-fold, and this rise in PI(3,5)P2 in endo-lysosomal membranes is critical for protection against hyperosmolarity (28, 29). Synthesis of PI(3,5)P2 is entirely dependent on a complex of the PI(3)P-dependent 5-kinase, Fab1/PikFYVE, a scaffolding protein, Vac14, and the PI-5-phosphatase Fig4 (24). In yeast, FAB1, VAC14, and FIG4 are nonessential genes, but deletions in these genes cause growth defects, particularly at high temperature, and growth is severely compromised in hyperosmotic medium (28, 30–32). The fab1Δ and vac14Δ mutants also exhibit massive enlargement in the vacuole (28). Unlike WT vacuoles, the enlarged vacuole of PI(3,5)P2-deficient mutants fails to fragment during hyperosmotic stress (31). Mammalian cells also form large vacuoles upon loss of PI(3,5)P2, possibly due to lysosomal coalescence (33).

Yeast fab1Δ and vac14Δ mutants have significantly reduced V-ATPase assembly and activity, under both iso-osmotic conditions and hyper-osmotic stress (34). In yeast cells, a Vph1-NT-GFP fusion that lacks the membrane domain can be recruited from the cytosol to the vacuole/endosome in a salt and PI(3,5)P2-dependent manner (34), but we were unable to show a direct interaction of Vph1-NT with PI(3,5)P2 liposomes in vitro. In contrast, we have recently shown that the Golgi isoform, Stv1-NT, binds to the Golgi lipid PI(4)P in vitro and in vivo, and this interaction ensures efficient Golgi localization of Stv1-containing V-ATPases (35). Both interaction of Stv1-NT with PI(4)P-containing liposomes in vitro, and Golgi localization of Stv1 in vivo require lysine 84 (Lys-84), which resides in the Golgi retention/retrieval sequence in the proximal domain of Stv1 (35, 36).

The question of whether Vph1 directly binds to PI(3,5)P2 remains unanswered. In this study, we show that exogenous addition of short-chain diC8 PI(3,5)P2 lipids activates Vph1-containing V-ATPases over their basal activity in a cell-free system. Activation is specific to PI(3,5)P2. Using a combination of molecular modeling, sequence comparison, and mutagenesis, we identified a region in the distal domain of VPH1 that is required for PI(3,5)P2-dependent activation but supports basal V-ATPase activity. Mutations in this region allow us to determine the contribution of PI(3,5)P2-dependent interactions with V-ATPases to maintenance of vacuolar morphology and protection from osmotic stress.

Results

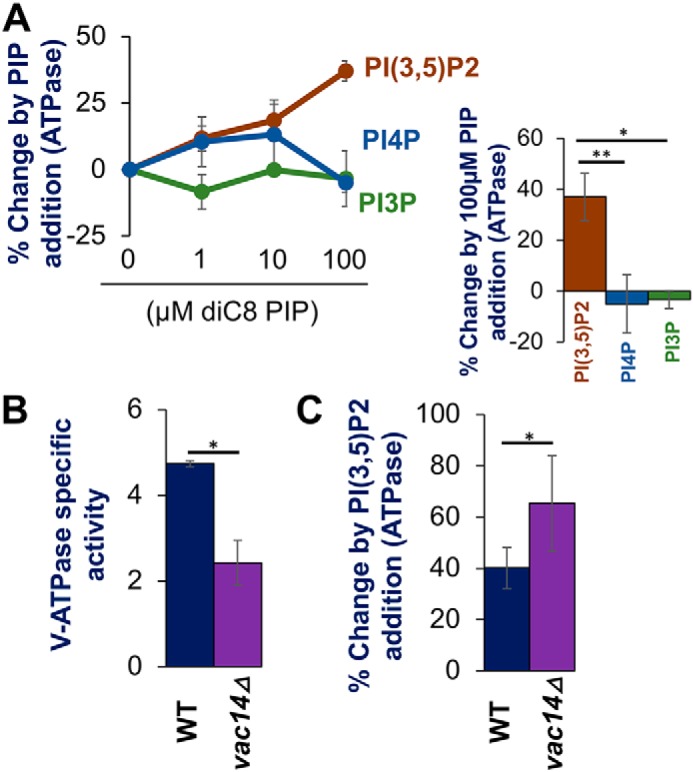

Exogenous PI(3,5)P2 enhances the activity of V-ATPases in isolated vacuolar vesicles

Although PI(3,5)P2 was shown to be necessary for increased V-ATPase activity in cells subjected to salt stress, and expressed Vph1-NT exhibited PI(3,5)P2-dependent membrane recruitment in vivo, it was not possible to distinguish direct effects of PI(3,5)P2 binding from indirect effects (34). In an attempt to assess more directly whether PI(3,5)P2 activates V-ATPases, we isolated vacuolar vesicles from wildtype (WT) yeast cells and examined the effects of adding exogenous short-chain phosphoinositide (PIP) lipids. Short-chain (C8) lipids are water soluble, but can partition into membranes (37). To test the effects of PIP addition, we added water-soluble diC8 PI(3,5)P2 directly to vacuolar vesicles, mixed rapidly, then added the mixture to the ATPase assay mixture, and assessed the rate of ATP hydrolysis. A parallel “mock” sample was treated with water instead of PI(3,5)P2. Addition of 100 μm PI(3,5)P2 activates V-ATPase activity by 37.0 ± 3.8% relative to mock treatment (Fig. 1A, right). Importantly, 100 μm diC8 PI(4)P or diC8 PI(3)P provided significantly less activation than 100 μm PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 1A, right). The proportion of the lipid that partitions into the membrane is affected by multiple factors, so determining the final mole percentage of the added lipid in the membrane is difficult. However, we found a dose-dependent activation in response to diC8 PI(3,5)P2 as shown in Fig. 1A. Specifically, 10 μm PI(3,5)P2 was activated by 18.6 ± 7.5%, and 1 μm PI(3,5)P2 by 11.7 ± 4.8% (Fig. 1A, left). We also did dose-response curves for PI(4)P and PI(3)P. The lower concentrations of PI(4)P did activate ATPase activity to a level comparable with lower concentrations of PI(3,5)P2, but as described below (Fig. 3), the PI(4)P activation may not be physiologically significant. PI(3)P gave no activation at any concentration.

Figure 1.

Exogenous PI(3,5)P2 enhances activity of V-ATPase on vacuolar vesicles isolated from WT and vac14Δ mutant cells. A: left, dose-response curves showing changes in ATPase activity with addition of the indicated concentrations PIP lipids to vacuolar vesicles from WT cells. Right: comparison of change from exogenous addition of 100 μm diC8 PIP lipids. B, V-ATPase–specific activity of WT (black bar) and vac14Δ (purple bar) (in μmol min−1 mg−1) from isolated vacuoles. C, percentage change in V-ATPase activity by exogenous addition of 100 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 to vacuolar vesicles isolated from WT (black bar) and vac14Δ (purple bar) yeast. In each case, values represent a mean value from three or more independent experiments. Error bars indicates mean ± S.E. A paired t test was run to analyze significance in differences of means. * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.005, and *** indicates p < 0.0005.

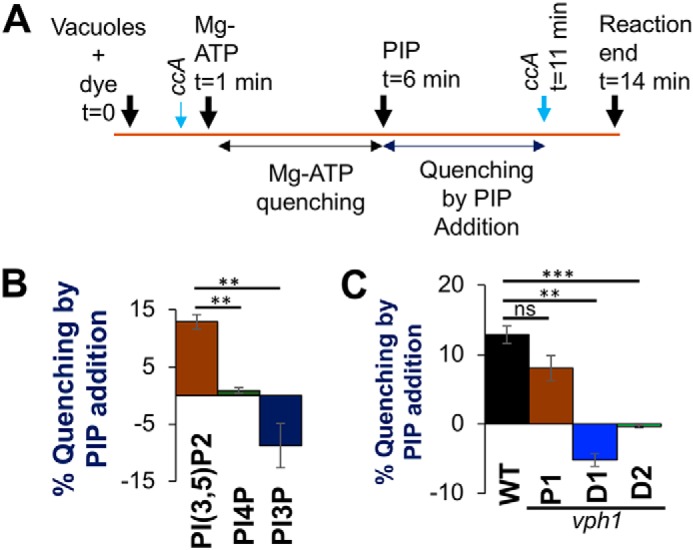

Figure 3.

PI(3,5)P2 promotes ATP-dependent proton pumping in isolated vacuolar vesicles. A, schematic of acridine orange quenching assay: vacuoles were loaded with the dye for 1 min followed by addition of 0.5 mm ATP and 1 mm MgSO4 (MgATP) (t = 1 min). After allowing an initial fluorescence quenching for 5 min, 10 μm diC8 PIP lipid was added to the reaction (t = 6 min) and fluorescent reading was continued. After 5 min (t = 11 min), the V-ATPase inhibitor ConA (ccA) (thick blue arrow) was added to observe de-quenching of fluorescence and the reaction was ended 3 min later (t = 14 min). ConA (thin blue arrow) was added to test if quenching is V-ATPase dependent before Mg-ATP addition. B, percentage fluorescence quenching on 10 μm diC8 PIP addition to vacuole vesicles, isolated from WT yeast, normalized to Mg-ATP dependent fluorescence quenching: PI(3,5)P2 (brown bar), PI(4)P (green bar), and PI(3)P (dark blue bar). C, percentage of fluorescence quenching on addition of 10 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 to vacuoles normalized to MgATP-dependent fluorescence quenching: vacuole vesicles are isolated from WT (black bar), vph1-P1 (brown bar), vph1-D1 (blue bar), and vph1-D2 (green bar) yeast. In each case, values represent a mean value from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± S.E. A paired t test was run to analyze significance in differences of mean. ns indicates p > 0.05, * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.005, and *** indicates p < 0.0005.

Previous studies showed that vac14Δ cells, which synthesize only 2–5% as much PI(3,5)P2 as WT cells (31, 32, 38), have significantly less V-ATPase activity on isolated vacuolar vesicles as well as reduced levels of peripheral V1 subunits. It was suggested that V1 subunits might be more loosely associated with Vo in the absence of PI(3,5)P2, and that PI(3,5)P2-dependent activation of V-ATPases in salt-stressed cells might reflect tightened V1-Vo interactions (34). We hypothesized that despite the partial assembly defect, vacuolar vesicles isolated from vac14Δ cells might contain a population of V-ATPases that could be activated by PI(3,5)P2. Consistent with previous results, vacuolar vesicles isolated from vac14Δ cells had only ∼50% of the V-ATPase activity of WT cells (Fig. 1B). However, addition of diC8 PI(3,5)P2 increased the V-ATPase activity in vac14Δ vacuolar vesicles by 65% (Fig. 1C). This is consistent with vac14Δ vacuolar vesicles retaining a population of assembled V-ATPases with low ATPase activity that can be activated when supplied with PI(3,5)P2.

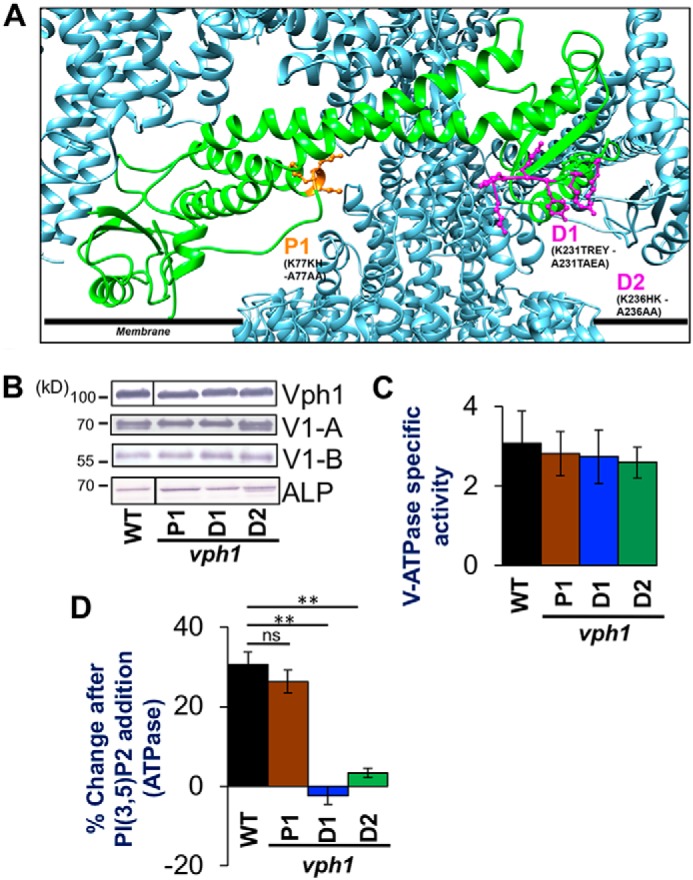

Mutations in Vph1-NT compromise PI(3,5)P2-dependent V-ATPase activation

There is no canonical PIP-binding domain in the available and predicted structures of Vph1-NT or Stv1-NT. We identified the Stv1(K84A) PI(4)P-binding mutation through modeling, sequence comparisons, and mutagenesis (35). We used a similar strategy to identify candidate PIP-binding residues in Vph1-NT that might affect PI(3,5)P2-dependent V-ATPase activation (Fig. S1, A and B). Recent structures indicate Vph1-NT undergoes structural reorganization between the assembled V1-Vo ATPase and the disassembled and autoinhibited Vo (20, 21). However, in the cryo-EM structure of the yeast V-ATPase (21), parts of Vph1-NT, including a large distal loop with sequence differences from Stv1, were unresolved. Therefore, we made a structural model of Vph1-NT using the Phyre2.0 server (39) and inserted the Vph1-NT model into the cryo-EM structure of the assembled V-ATPase, after removing the incomplete Vph1-NT from the original structure (Fig. 2A). Keeping in mind increasing evidence of involvement of basic and aromatic amino acids in noncanonical PIP and PI(3,5)P2 binding, we looked for amino acid patches with these characteristics in regions of Vph1-NT facing the organelle membrane (Fig. 2A) (40, 41). We speculated that residues that are not conserved between Vph1 and Stv1 (Fig. S1) would be most likely to confer PI(3,5)P2-specific binding. Aligning the amino acid sequences encoded by VPH1 genes of related fungal species, we identified residues that are conserved among VPH1 homologues in related fungal species, but not found in STV1 (Fig. S1, B and C). Two sites matched all these criteria: 77KKH in the proximal domain and 231KTREYKHK in the distal domain of Vph1-NT. We generated three mutants: 77AAA in the proximal domain (designated vph1-P1) and 231ATAEA (vph1-D1) and 236AAA (vph1-D2), both in the distal domain of Vph1-NT. We introduced the mutations into the genomic copy of VPH1, and tested the mutants for assembly (Fig. 2B), basal V-ATPase activity (Fig. 2C), and PI(3,5)P2-dependent V-ATPase activation (Fig. 2D). The three mutations did not compromise growth on YEPD + ZnCl2 plates, indicating that there is no gross defect in vacuolar acidification (17). All the mutant Vph1 proteins were transported to the vacuole, where they were present at WT levels, based on immunoblotting of isolated vacuolar vesicles for Vph1. In addition, the mutant Vph1 proteins supported assembly of WT levels of the V1A and V1B subunits (Fig. 2B). V-ATPase activity was also not significantly different between WT and vph1-P1, -D1 or -D2 mutants (Fig. 2C). We next tested these mutants for activation by addition of 100 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 2D). Although V-ATPase activity in vesicles isolated from the vph1-P1 mutant was still activated by diC8 PI(3,5)P2, similar to WT, the vph1-D1 and -D2 mutants failed to be activated by PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 2D). This suggests that the 236KTREYKHK region in the distal loop of Vph1-NT is required for PI(3,5)P2-dependent activation and may act as a PI(3,5)P2-binding site.

Figure 2.

PI(3,5)P2 activation mutations in Vph1 eliminates PI(3,5)P2-dependent V-ATPase activation. A, structural model of PHYRE2.0 generated Vph1-NT (green chain) replacing partial Vph1NT in the available cryo-electron microscope generated structure of the yeast V-ATPase (PDB 3J9T) using Matchmaker (21, 39). Polypeptide chains at the V1-Vo interface are colored in metallic blue. The sites on Vph1-NT that are mutated are indicated in ball and stick as P1 (orange), D1 and D2 (both in purple). The residues and their corresponding mutations are written in black letters. Numbers indicate the position of the amino acid in the polypeptide chain. The black line indicates the approximate position of the cytosolic leaflet of the organelle membrane. B, immunoblots of vacuolar protein samples from WT, vph1-P1, vph1-D1, and vph1-D2 yeast strains separated by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblots were probed for the vacuolar proteins indicated on the right. Lines indicate nonadjacent lanes from the same gel. Alkaline phosphatase is used as loading control. C, V-ATPase-specific activity (μmol min−1 mg−1) of WT (black bar), vph1-P1 (brown bar), vph1-D1 (blue bar), and vph1-D2 (green bar) vacuoles isolated from a corresponding strain. D, percentage change in V-ATPase activity by exogenous addition of 100 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 to vacuoles isolated from WT (black bar), vph1-P1 (brown bar), vph1-D1 (blue bar), and vph1-D2 (green bar) yeast. In each case, values represent a mean value from three or more independent experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± S.E. A paired t test was run to analyze the significance in differences of mean, where indicated. ns indicates p > 0.05 and ** indicates p < 0.005.

PI(3,5)P2 specifically promotes ATP-dependent proton pumping in vacuolar vesicles

Although PI(3,5)P2 enhances V-ATPase activity in isolated vacuolar vesicles, the experiments above do not test whether H+-pumping is affected. To test effects on H+-pumping, we utilized a microplate-based assay system (Fig. 3A, see also “Experimental procedures”). Acidification of vacuolar vesicles is detected by quenching the fluorescent probe acridine orange at an emission wavelength of 520 nm. As diagrammed in Fig. 3A, we first added MgATP to vacuolar vesicles and allowed the establishment of a pH gradient, as measured by acridine orange quenching, over 5 min. We then added the specified PIP and determined whether there was further quenching, which would indicate increased pumping. Additional quenching after addition of PIP was expressed as a percentage of the original MgATP-driven quench. We detected a 13% increase in quenching after addition of 10 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 3B). Although 10 μm diC8 PI(4)P caused a small activation of ATPase activity (Fig. 1A), it failed to enhance quenching, whereas 10 μm diC8 PI(3)P addition partially collapsed the MgATP-dependent gradient (Fig. 3B). Although 100 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 activated ATPase activity, the addition of 100 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 collapsed the pH gradient, possibly because insertion of short-chain lipids can disrupt packing of membrane lipids and render the membrane leaky to protons. MgATP-dependent quenching was prevented if concanamycin A (ConA) was added before MgATP (as diagrammed in Fig. 3A). However, if ConA was added after PIP treatment, acridine orange fluorescence was fully recovered, indicating that the proton gradient is completely dependent on V-ATPase activity. Taken together, these results indicate that V-ATPase–dependent H+-pumping is enhanced by the vacuolar lipid PI(3,5)P2, but not by PI(4)P or PI(3)P.

Next, we tested whether PI(3,5)P2 could enhance H+-pumping in our vph1 mutants. Acidification was increased by diC8 PI(3,5)P2 addition in the vph1-P1 mutant (Fig. 3C). However, although the vph1-D1 and -D2 mutants were able to establish a MgATP-driven proton gradient as indicated by an initial fluorescent quench, PI(3,5)P2 failed to give any significant additional quenching (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that ATP-driven proton pumping is specifically enhanced by PI(3,5)P2 and compromised by mutations that prevented ATPase activation.

Physiological effects of loss of PI(3,5)P2 activation

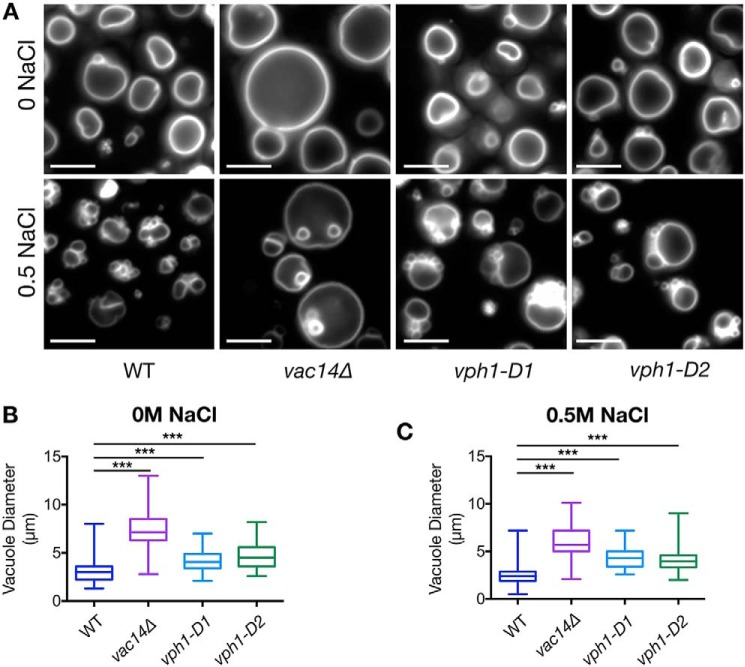

The vph1 mutants that lack PI(3,5)P2 activation, but retain WT levels of basal V-ATPase activity, allow us to test the physiological requirement for PI(3,5)P2 activation of the V-ATPase. One dominant feature of yeast cells lacking PI(3,5)P2 is their enormously enlarged vacuoles (28). The mechanism behind the enlargement is incompletely understood (42, 43). Cells chronically or acutely deprived of V-ATPase activity do not undergo such vacuolar enlargement (43–45). We tested whether V-ATPase activation by PI(3,5)P2 was required to maintain normal vacuolar morphology. We stained yeast vacuoles with FM4-64 and visualized vacuolar morphology under a fluorescent microscope. As shown in Fig. 4, a vac14Δ mutant has the very large vacuoles characteristic of PI(3,5)P2 deficiency. Although vph1-D1 and vph1-D2 mutants do not have the extremely large vacuoles of vac14Δ mutants, when we measured and compared the diameters of the largest vacuole in the different cell types, we found that vacuoles in the vph1-D1 and vph1-D2 mutants are significantly larger than WT vacuoles (Fig. 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Loss of V-ATPase activation by PI(3,5)P2 compromises vacuolar morphology and fragmentation under hypertonic stress. A, fluorescent micrographs of WT, vac14Δ, vph1-D1, and vph1-D2 strains, stained with the vacuolar dye FM4-64. Images of stained cells, either unexposed to NaCl (upper panel) or, briefly exposed to 0.5 m NaCl (lower panel) are presented. White bar on the lower left corner of individual images is a scale bar representing 5 μm dimension. Images are representative of two independent experiments performed using ∼200 cells for each strain on each occasion. B and C, box and whisker plots representing diameters (in μm) of the largest vacuole of yeast cells in the absence (B) and presence of 0.5 m salt (C). The line within the box represent a median value of vacuolar diameter. A paired t test was run to analyze significance in differences of mean. *** indicates p < 0.0005.

PI(3,5)P2 levels transiently increase by up to 20-fold in response to hyperosmotic stress. In WT cells, WT vacuoles fragment over approximately the same time frame (within 15 min) (46). As shown in Fig. 4A, multiple small vacuoles are present in WT cells within ∼10 min of treatment with 0.5 m NaCl, but vac14Δ vacuoles largely fail to fragment (31). Interestingly, the vph1-D1 and vph1-D2 mutants exhibit an intermediate phenotype, maintaining a significantly larger vacuolar diameter than WT cells, but not as large as vac14Δ cells (Fig. 4, B and C). In combination, these results indicate that V-ATPase activation by PI(3,5)P2 may contribute to maintaining vacuolar size and morphology under normal and hyperosmotic conditions but does not fully account for the phenotypes seen when PI(3,5)P2 is missing.

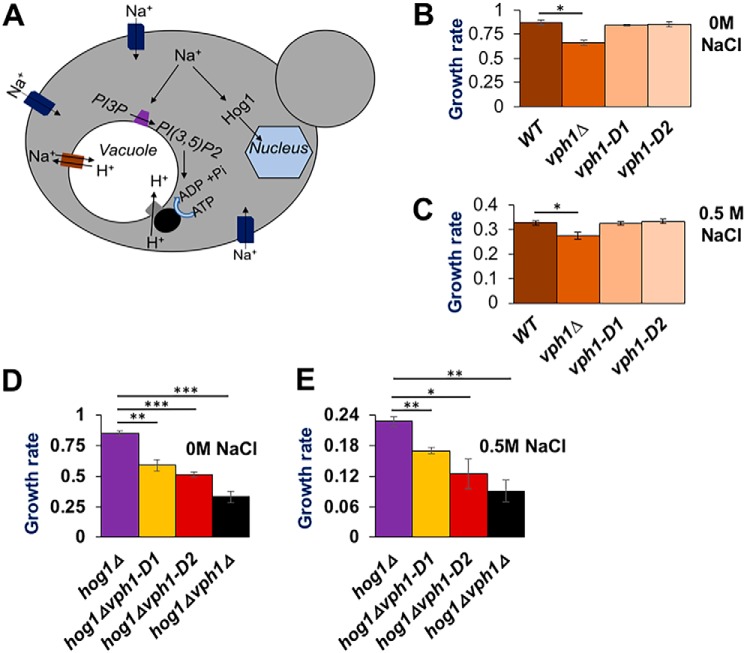

Salt stress activates V-ATPase activity in a PI(3,5)P2-dependent manner (34), so we surmised that mutations in Vph1 that affect PI(3,5)P2 activation of V-ATPases might result in a salt-specific change in growth rate. However, there was no significant decrease in the rate of doubling (doubling/h) between WT and the mutants in either the presence or absence of salt (Fig. 5, B and C). The vph1Δ mutant, which completely lacks V-ATPase activity at the vacuole, does show a significant growth defect relative to WT cells in the absence of added salt, and this defect is aggravated by salt addition (Fig. 5, B and C).

Figure 5.

Synthetic growth defects between vph1-PI(3,5)P2 activation mutations with hog1Δ under hyperosmotic stress. A, cartoon depicts two pathways involved in physiological response of yeast to hyperosmotic stress by Na+ ions: (i) the initial protection pathway that relies on PI(3,5)P2 synthesis and increased assembly and activity of V-ATPase, generating H+ gradient to be utilized for Na+ import to the vacuole via Na+/H+ exchangers. (ii) HOG pathway that relies on activation and nuclear translocation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1, which generates osmo-protective gene regulation. B and C, growth rate (doublings per hour) of wildtype (WT), vph1Δ, vph1-D1, and vph1-D2 yeast strains in medium containing 0 m NaCl (B) and 0.5 m NaCl (C). D and E, growth rate (doublings per hour) of the indicated strains (labeled below corresponding bars on the x axis) with 0 m NaCl (D) and 0.5 NaCl (E) in the growth media. Mean growth rates are obtained from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate the mean ± S.E. ns indicates p > 0.05, * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.005, and *** indicates p < 0.0005.

It has been suggested that vacuolar PI(3,5)P2 increases may act in parallel with the Hog1 MAP kinase pathway to provide an immediate relief from salt stress until transcriptional changes driven by the Hog1 MAP kinase pathway take effect (Fig. 5A) (29, 31). Consistent with this, vma mutations generate synthetic growth defects in combination with mutations in the Hog1 pathway (47). We made double mutants containing vph1-D1, vph1-D2, or vph1Δ mutations along with a hog1Δ mutation. Even in the absence of salt stress, all of the double mutants grew more slowly than the hog1Δ mutant, indicating a synthetic growth defect (Fig. 5D). The growth of the hog1Δ mutant is significantly slowed in the presence of 0.5 m NaCl (Fig. 5, D and E), as observed previously (48). However, the hog1Δvph1-D1 and hog1Δvph1-D2 mutants still exhibit synthetic growth defects (Fig. 5, D and E). This indicates that loss of PI(3,5)P2 activation of V-ATPase activity is important under both high and low salt conditions, particularly if the Hog1 MAP kinase pathway is unavailable. However, under both normal osmotic and hyperosmotic conditions hog1Δvph1-D1 and hog1Δvph1-D2 mutants grow better than hog1Δvph1Δ mutants. This is likely because the vph1-D1 and -D2 mutants maintain a basal level of V-ATPase activity that is lacking in a vph1Δ mutant (47, 49). Overall, our result suggests that failure of PI(3,5)P2-dependent V-ATPase activation can be tolerated, even in the presence of 0.5 m NaCl, but a synthetic growth defect is uncovered upon loss of stress response pathways like the HOG pathway.

Discussion

This work addresses how organelle-specific inputs, specifically, PIP content, can impact V-ATPase activity and induce a response to extracellular stress. When exogenous short-chain lipids were added to vacuolar vesicles, the V-ATPase activity was activated in a PI(3,5)P2-specific manner. Previous work has shown that both assembly and ATP-dependent H+-pumping activity of Vph1-containing V-ATPases are compromised by reduced PI(3,5)P2 synthesis in fab1Δ and vac14Δ mutants (34). Moreover, under hyperosmotic stress, PI(3,5)P2 levels increase rapidly and V-ATPase assembly and activity also increase (34).

Soluble short-chain PIP lipids have been used to assess PIP binding and activation of other membrane proteins (37, 50), but to our knowledge, this is the first time they have been shown to increase activity of any eukaryotic V-ATPase. It is challenging to estimate the percentage of short-chain lipids that partition into the vacuolar vesicle membranes in the absence of any vacuolar membrane model for diC8 PIP lipid partitioning. Biophysical studies in a plasma membrane model suggested that to reach 4 mol % short-chain lipid, ∼340 μm diC8 PI(4,5)P2 had to be added to solution around plasma membrane patches (37). A recent single particle study of a mammalian lysosomal TPC1 channel demonstrated that maximum PI(3,5)P2-dependent channel activity required addition of 10 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 to membrane patches (41). Moreover, 500 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 was used to generate a PI(3,5)P2-bound cryo-EM structure of TPC1 reconstituted into lipid nano-discs (41). These studies suggest that the concentration range used in our study is not unreasonable, even though PI(3,5)P2 is present at very low levels in vivo. We show that increasing concentrations of diC8 PI(3,5)P2 progressively increase the activity of Vph1-containing V-ATPases up to 100 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2, but with an appreciable activation at 10 μm lipid. Addition of 10 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 further increased the pH gradient across vacuolar vesicles after a MgATP-dependent pH gradient was established. Both the initial MgATP-dependent fluorescence quench and the additional quench upon lipid addition were concanamycin A-sensitive, indicating that PI(3,5)P2 activates proton pumping by the V-ATPase as well as ATP hydrolysis. Curiously, 100 μm diC8 PI(3,5)P2 collapsed, rather than increasing, the proton gradient, but this may reflect the loss of membrane integrity in the vesicles upon the integration of high concentrations of short-chain lipid.

How do short-chain PIP lipids exert their effects on V-ATPase activity? Li et al. (34) predicted that a loosely assembled pool of V-ATPase exists in the vacuolar membrane and that this population can be activated by elevated PI(3,5)P2 during hyperosmotic stress. We propose that the exogenous short-chain PIP lipids used here partition into vacuolar membranes, bind to Vph1-NT, and activate V-ATPase activity, possibly by stabilizing a loosely assembled pool of enzyme. Although we have evidence from liposome flotation assays that Stv1-NT binds directly to PI(4)P (35), we did not observe specific binding of bacterially expressed Vph1-NT with PI(3,5)-containing liposomes. We previously demonstrated that Vph1NT-GFP, in the absence of other V-ATPase subunits, can be recruited from cytosol to membranes in a PI(3,5)P2-dependent manner, suggesting that a PI(3,5)P2-binding site is present in Vph1-NT (34), but binding could also be indirect. Although short-chain PI(3,5)P2 activation of Vph1-containing V-ATPases could also be indirect, our structure-based identification of potential PIP-binding residues in Vph1-NT led to design of mutations that abolished PI(3,5)P2-induced activation, supporting a direct effect. Further mutagenesis will be necessary to determine exactly which amino acids are critical for PI(3,5)P2 binding, but the results in Fig. 2 indicate that a contiguous sequence in the distal end of Vph1-NT is important. Like other lysosomal membrane proteins that proved to bind PI(3,5)P2 (26, 51, 52), this sequence does not contain any canonical PIP-binding domain but does include both basic and aromatic amino acids. This sequence is not well-resolved in the cryo-EM structures of the detergent-solubilized yeast V-ATPase, but both the proximal and distal ends of Vph1-NT have critical interactions with peripheral V1 sector that are important for V-ATPase stability. In contrast, both the proximal and distal ends of Vph1-NT collapse toward the center of isolated Vo subdomains during V-ATPase disassembly. Binding to PI(3,5)P2 could activate V-ATPase activity by stabilizing the fully assembled complex and/or destabilizing a partially disassembled (or loosely assembled) complex that has adopted conformational features of free Vo subcomplexes.

Our understanding of how organisms cope with stresses such as unbalanced osmolarity is limited. Yeast cells respond to hyperosmotic stress through several cascades with highly conserved components: transcriptional activation via the HOG MAPK pathway, synthesis of PI(3,5)P2 by the Fab1/Vac14/Fig. 4 complex, and V-ATPase activation (38, 47, 48). During hyperosmotic stress, PI(3,5)P2 levels increase rapidly and V-ATPase assembly and activity increase (31, 34). Increased PI(3,5)P2 at the vacuolar membrane may enhance V-ATPase-dependent H+-pumping, establishing a pH gradient that could be used to sequester ions during the initial stages of hyperosmotic stress. We were able to test the specific requirement for PI(3,5)P2-mediated activation of V-ATPase activity using the vph1 mutants that compromised lipid activation but not V-ATPase activity. We found that these mutants had somewhat enlarged vacuoles in both the presence and absence of salt, but were capable of WT growth rates even in the presence of 0.5 m NaCl. Interestingly, the vph1 lipid activation mutations generated significant synthetic growth defects when combined with a hog1Δ mutation. This suggests that PI(3,5)P2 activation of the V-ATPase is important for growth under salt stress, but the Hog MAP kinase pathway can partially compensate when activation is lost.

Like V-ATPases, PIP lipid species and their organelle enrichment are highly conserved among eukaryotes (22, 23). The idea that PIP lipids might control luminal pH dynamics has been suggested (38, 53) but this idea has been disputed (54) and mechanistic evidence has been limited. Our study strongly suggests that PIP lipids can bind to V-ATPases and regulate their activity. This binding is very likely to contribute toward organelle pH regulation, although it may “fine-tune” pH in specific locations rather than serving as an all-or-none signal, as, notably, Vph1-containing V-ATPases have a basal activity in the absence of activating PIP lipid.

Overall, this study advances the knowledge of how an organelle-enriched PIP lipid regulates the activity of V-ATPases resident in that organelle. Additionally, it demonstrates how eukaryotic organisms can exploit this regulation to cope with stress. PI(3,5)P2 is synthesized in the mammalian late endosomes/lysosomes by a conserved Fab1/PikFYVE kinase (28). Mutations disabling PI(3,5)P2 synthesis cause debilitating diseases such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome and ALS (55). We have limited understanding of how these neurodegenerative diseases arise from PI(3,5)P2 deficiency. Although the diseases are neurodegenerative in nature, extensive vacuolation is found in all studied cell types with a loss of PI(3,5)P2 (24, 45). In yeast and some mammalian cell lines, inhibition of V-ATPase reverses the large vacuolation phenotype of PI(3,5)P2 deficiency (43, 44). These studies highlight the importance of understanding the intricate connections between PIP lipid levels and V-ATPase activity.

Experimental procedures

Media and cell growth

Yeast were either grown on rich media containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose (YEPD) or fully supplemented minimal media containing 2% dextrose (SD + All). Where indicated, YEPD was buffered to pH 5.0 by 50 mm potassium phosphate and 50 mm potassium succinate. YEPD + Zn consisted of 4 mm ZnCl2 in unbuffered YEPD. YEPD + G418, used to select for growth of kanR strains, contained 200 μg/ml of G418 (Gibco Genticin, Thermo Fisher Scientific). YEPD + Nat, used to select for growth of natR strains, contained 100 μg/ml of Nourseothricin (Jena Bioscience). Complementation of ura3 and leu2 auxotrophies was determined by growth on supplemented minimal medium lacking uracil or leucine. Bacteria harboring ampicillin-resistant plasmids were grown on LB broth, Miller powder (Fisher BioReagents) was adjusted to pH 7.0, containing 125 μg/ml of ampicillin (Sigma). Yeast cells were grown to log phase in the indicated media and collected near A600 = 1 for transformation, growth assays, and microscopy. For growth assays, yeast strains were grown overnight in SD + All and diluted to A600 = 0.1 by adding either SD + All or SD + All containing 0.5 m NaCl when indicated. Growth over time was then monitored on a SpectraMax i3X multimode multiplate reader.

Yeast strains

Genotypes of strains used are listed in Table 1. The vph1Δ::LEU2 allele was introduced into the SF838-5Aα background according to Manolson et al. (56). Transformants grew on SD plates lacking leucine, failed to grow on YEPD + Zn plates, and were negative for Vph1 on Western blots of isolated vacuoles. The vph1-P1 (K77KH-A77AA), vph1-D1 (K231TREY-A231TAEA), and vph1-D2 (K236HK-A236AA) mutations were introduced into the VPH1 gene in a pRS316 vector (57), using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis technique (Agilent Technologies). To generate the vph1-P1 mutant, primers Vph1KKH and Vph1KKHreverse were used. (All oligonucleotides used are listed in Table 2.) The vph1-D1 mutant was generated using the primers Vph1frwKTR and Vph1revKTR. The vph1-D2 was generated using the primers Vph1frwKHK and Vph1revKHK. Point mutations were introduced into the genomic copy of VPH1 as described in Banerjee and Kane (35). Briefly, amino acids 50–300 of Vph1-NT were deleted by inserting a URA3 fragment PCR-amplified from a pRS316 template using the primers VPH1NT50aa-URAfwd and Vph1NTaa300URArev, transforming WT cells with this fragment, and selecting transformants on SD-URA. PCR fragments carrying point mutations in VPH1 (vph1-P1, vph1-D1, and vph1-D2) were amplified from the plasmids carrying the indicated mutations using primers Vph1_50–300_F and Vph1_50–300_R. Transformants that had replaced the URA3 allele with the mutant vph1 fragment were selected on media containing 5-fluoroorotic acid. Insertion of each set of mutations was confirmed by sequencing. The hog1Δ::URA3 strain was constructed by amplifying the URA3 gene with primers Hog1D-URA-F and Hog1D-URA-R and transforming into SF838-5Aa yeast cells. Transformants were selected by growth on SD-URA and confirmed by PCR from genomic DNA. The hog1::URA3 allele was inserted similarly in vph1Δ::LEU2, vph1-D1, and vph1-D2 to obtain the double mutants hog1Δvph1Δ, hog1Δvph1-D1, and hog1Δvph1-D2, respectively.

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SF838-5Aα | MATα leu3–2, 112 ura3–52 ade6 gal2 | |

| SF838-5Aa | MATa leu3–2, 112 ura3–52 ade6 his4–519 | |

| vph1Δ | SF838-5Aα vph1Δ::LEU2 | 21 |

| vac14Δ | SF838-5Aα vac14Δ::kanR | 39 |

| hog1Δ | SF838-5Aa hog1Δ::URA3 | This study |

| P1 | SF838-5Aα VPH1(K77KH-A77AA) | This study |

| D1 | SF838-5Aα VPH1(K231TREY-A231TAEA) | This study |

| D2 | SF838–5Aα VPH1(K236HK-A236AA) | This study |

| hog1ΔD1 | SF838-5Aα hog1Δ::URA3 VPH1(K231TREY-A231TAEA) | This study |

| hog1ΔD2 | SF838-5Aα hog1Δ::URA3 VPH1(K236HK-A236AA) | This study |

| hog1Δvph1Δ | SF838-5Aα hog1Δ::URA3 vph1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| Stv1(WT) (or, PTEF-STV1 vph1Δ) | SF838-5Aα vph1Δ::LEU2 PTEF-STV1::kanR | This study |

| Stv1(K84A) (or, PTEF-stv1(K84A) vph1Δ) | SF838-5Aα vph1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| PTEF-STV1(K84A)::kanR |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′->3′) |

|---|---|

| VPH1NT50aa-URAfwd | GCTTACACTTTAGGTCAATTGGGTCTTGTTCAATTCCGTGACTTGAACTCTAAGGTGCGTGCGTACTGAGAGTGCACCACGCT |

| Vph1NTaa300URArev | CGCCTTTTCACGGGTAACATCTTGGAACCAAGAGTCCAATTCTTTGGCAATGGCCAGTTTTTTAGTTTTGCTGGCC |

| Vph1_50–300_F | GGCAGAGAAGGAGGAAGCG |

| Vph1_50–300_R | GGAAGGTAGGTGGAGTGTGG |

| Hog1D-URA-F | CCACTAACGAGGAATTCATTAGGACACAGATATTCGGTACAGTTTTCGAGTACTGAGAGTGCACCACGCT |

| Hog1D-URA-R | CCTGGTTACCGTAGTCCGTAATGGTGTCATTTGCAGCTACATGATCGCTGCAGTTTTTTAGTTTTGCTGGCC |

| Hog1–5' | TAGTGGAAGAGGAATTTGCG |

| URA-int | CCTTAGCATCCCTTCCCTTTG |

| STV1-for-S1 | CCTCGTGACCTCGAGGCTTACATTAAGGTGCATATCATAATTCGCAACAGACGCCGTACGCTGCAGGTCGAC |

| STV1-rev-S4 | AGTTGGACGTACGTCATGTCTGCTGACCGGAATATAGCCTCTTCTTGATTCATCGATGAATTCTCTGTCG |

| STV1-URA-UP | CCAGTTGAGGCGTTTCGATGAAGTGGAAAGGATGGTAGGCTTCTTGAATGAGGTACTGAGAGTGCACCACGCT |

| STV1-URA-DOWN | GGATCAATTCTGTGGAAGGCACCCAACCTTCGGCTATTAGACCCTGTGATCAGTTTTTTAGTTTTGCTGGCC |

| STV1-mut-UP | GAGGCTATATTCCGGTCAGCAGAC |

| STV1-mut-DOWN | AATGGATCAATTCTGTGGAAGGC |

| Vph1–1 | GAGGTATTTAGAAGTGAAGAGAC |

| Vph1-C4 | AACGTTTCATGAGATAAGTTTGGC |

| Vph1frwKTR | ATTGAACAACCTGTTTATGATGTCGCAACCGCGGAGGCTAAACATAAAAATGCTTTTATCGTA |

| Vph1revKTR | AAATACGATAAAAGCATTTTTATGTTTAGCCTCCGCGGTTGCGACATCATAAACAGGTTGTTCAAT |

| Vph1frwKHK | TATGATGTCAAAACCAGGGAGTATGCAGCTGCAAATGCTTTTATCGTATTTTCTCAC |

| Vph1revKHK | GTGAGAAAATACGATAAAAGCATTTGCAGCTGCATACTCCCTTGGTTTTGACATCATA |

| Vph1KKH | GTATCGTTACTTTTATTCTCTTTTGGCGGCAGCCGATATTAAGCTCTACGAAGGAG |

| Vph1KKHreverse | GAGCTTAATATCGGCTGCCGCCAAAAGAGAATAAAAGTAACGATACTGTCTTTC |

Vacuole isolation and biochemical analysis

Vacuole isolations were performed according to Li et al. (34). Log-phase cells were converted to spheroplasts, lysed, and broken by a tight fit Dounce homogenization. Vacuolar vesicles were isolated after two rounds of Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Purified vacuolar vesicles were tested for ATPase activity in a coupled ATPase enzyme assay at 37 °C (59). To assess V-ATPase–specific activity, 330 nm ConA was added. Protein concentration was determined by Lowry assay (60) to determine V-ATPase–specific activity.

Western blots of vacuolar proteins were performed by solubilizing vacuolar membranes in cracking buffer as described (34). Samples containing equal masses of vacuolar protein were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Peripheral V-ATPase subunits V1-A, V1-B, and V1-C, and alkaline phosphatase, used as a vacuolar loading control, were probed on immunoblots as described (34). Vph1 was probed with a mouse monoclonal 7B1H1 primary antibody (61). Representative immunoblots were scanned to obtain images used for figures. Blots were equivalently processed for WT and mutants.

V-ATPase activity assay with PIP addition

Vacuolar vesicles were isolated from yeast cells grown in YEPD medium that was adjusted to pH 5 with HCl before cells were added. Vacuolar vesicles were isolated by flotation as described, but spheroplasts were not recovered in glucose before lysis (62). Each diC8 PIP lipid (Echelon Biosciences) was dissolved to a stock concentration of 2.5 mm in deionized water. 3–5 μl of fresh vacuolar membranes were rapidly mixed with 12 μl of the designated lipids. Mock samples received an equal volume of water. The mixtures were immediately added to 300 μl of the coupled ATPase assay mixture (63) to give final lipid concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μm PIP, and ATPase activity was measured at 37 °C. The percent change in V-ATPase activity from PIP addition was calculated as follows: 100(activity of PIP-treated vacuole − activity of mock-treated vacuole)/(activity of mock-treated vacuole). Concanamycin A was added as described above to test if the activity was specific to V-ATPase.

Acridine orange quenching assay by PIP addition

Acridine orange quenching assays were carried out in a black, 96-well flat-bottom plate with a nonadherent surface at 27 °C. The final reaction volume was 60 μl. 5 μg of vacuole vesicles were equilibrated with 15 μm acridine orange (Sigma) and pre-MgATP readings were taken for 1–2 min. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission of 520 nm in a SpectraMax i3X multi-mode multiplate reader. H+-pumping was triggered by adding 0.5 mm ATP and 1.0 mm MgSO4 and fluorescence was measured for 5 min at a minimum interval setting. The fluorescence quenching after 5 min was measured, then diC8 PI(3,5)P2, PI(3)P, or PI(4)P (final concentration 10 μm) was added to separate wells to test for further quenching of acridine orange after 5 min. ConA was added to a final concentration of 820 nm, either before MgATP, or, after PIP-dependent quenching reached steady state. Readings were taken for 3 min after ConA addition; V-ATPase–specific quenching was indicated by a return to the initial reading. The extent of acridine orange quenching was again calculated after diC8 PIP lipid addition. The percentage change due to lipid addition was determined by dividing the percentage change in fluorescence 5 min after lipid addition by the initial percentage change in fluorescence 5 min after MgATP addition.

Protein structure prediction

The 231KTREYKHK sequence in Vph1 was unresolved in the available assembled model of the V-ATPase (19, 21). We used Phyre2.0 to predict the structure of the NT of Vph1 by homology modeling to the available cryo-EM structure of the yeast V-ATPase state-1 (PDB code 3J9T) (19, 21, 39). The obtained structure (estimated 100% confidence) was superimposed in the V1-Vo structure, removing the Vph1-NT domain in the original structure. This process was performed in UCSF Chimera (64).

Vacuole staining and fluorescent microscopy

After growing yeast cultures to log phase, cells were stained with the vacuolar dye FM4-64 as described in Ref. 35, but using a concentration of 20 μm FM4-64 during the pulse labeling (65). The chase was performed for 2 h at 30 °C in SD + All media to ensure vacuolar staining. Images of live yeast cells were taken in a Zeiss Axio fluorescence microscope with a Hamamatsu EMCCD camera at equal exposure times. Images prepared for figures were equivalently adjusted for brightness and contrast using NIH ImageJ and a representative figure was made using Adobe Illustrator.

Diameter of the largest vacuole of each yeast cell was measured using the line tool of NIH ImageJ. 50 cells were measured in each of two independent experiments (100 cells total) for every cell type and condition. Measurements were converted to a micrometer scale by comparison to a 5-μm standard line. Vacuolar diameters for each cell type were plotted into box and whisker plots using GraphPad Prism software.

Statistical analysis

All bar charts are averages of replicates from biologically independent experiments. All experiments include at least three or more biological replicates. Data are represented as mean ± S.E. To test if two means are significantly different, an unpaired t test was performed with a criterion of p < 0.05 considered as significantly different. In the figures, * represents p < 0.05; ** indicates p < 0.005; and *** indicates p < 0.0005.

Author contributions

S. B. and P. M. K. conceptualization; S. B., K. C., and P. M. K. data curation; S. B., K. C., and P. M. K. formal analysis; S. B. and P. M. K. supervision; S. B. and P. M. K. funding acquisition; S. B. and M. T. validation; S. B., K. C., M. T., and P. M. K. investigation; S. B., K. C., and M. T. methodology; S. B. writing-original draft; S. B. and P. M. K. project administration; S. B. and P. M. K. writing-review and editing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Anne Smardon and Theodore Diakov for introducing the vph1-P1, -D1, and -D2 mutations in the cloned VPH1 gene. We thank Dr. Rutilio Fratti and Greg Miner, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, for sharing the microplate protocol for testing phosphoinositide-dependent proton pumping in vacuolar vesicles.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM50322 and GM126020 (to P. M. K.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Fig. S1.

- V-ATPases

- vacuolar H+-ATPases

- mTOR

- mechanistic target of rapamycin

- NT

- N-terminal domain

- PIP

- phosphatidylinositol phosphate

- ConA

- concanamycin A.

References

- 1. Kane P. M. (2006) The where, when, and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 177–191 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.177-191.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forgac M. (2007) Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 917–929 10.1038/nrm2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casey J. R., Grinstein S., and Orlowski J. (2010) Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 50–61 10.1038/nrm2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brett C. L., Kallay L., Hua Z., Green R., Chyou A., Zhang Y., Graham T. R., Donowitz M., and Rao R. (2011) Genome-wide analysis reveals the vacuolar pH-stat of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 6, e17619 10.1371/journal.pone.0017619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oot R. A., Couoh-Cardel S., Sharma S., Stam N. J., and Wilkens S. (2017) Breaking up and making up: the secret life of the vacuolar H+-ATPase. Protein Sci. 26, 896–909 10.1002/pro.3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun-Wada G., Murata Y., Yamamoto A., Kanazawa H., Wada Y., and Futai M. (2000) Acidic endomembrane organelles are required for mouse postimplantation development. Dev. Biol. 228, 315–325 10.1006/dbio.2000.9963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karet F. E., Finberg K. E., Nelson R. D., Nayir A., Mocan H., Sanjad S. A., Rodriguez-Soriano J., Santos F., Cremers C. W., Di Pietro A., Hoffbrand B. I., Winiarski J., Bakkaloglu A., Ozen S., Dusunsel R., et al. (1999) Mutations in the gene encoding B1 subunit of H+-ATPase cause renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness (see comments). Nat. Genet. 21, 84–90 10.1038/5022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frattini A., Orchard P. J., Sobacchi C., Giliani S., Abinun M., Mattsson J. P., Keeling D. J., Andersson A. K., Wallbrandt P., Zecca L., Notarangelo L. D., Vezzoni P., and Villa A. (2000) Defects in TCIRG1 subunit of the vacuolar proton pump are responsible for a subset of human autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. Nat. Genet. 25, 343–346 10.1038/77131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kornak U., Schulz A., Friedrich W., Uhlhaas S., Kremens B., Voit T., Hasan C., Bode U., Jentsch T. J., and Kubisch C. (2000) Mutations in the a3 subunit of the vacuolar H+-ATPase cause infantile malignant osteopetrosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2059–2063 10.1093/hmg/9.13.2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kornak U., Reynders E., Dimopoulou A., van Reeuwijk J., Fischer B., Rajab A., Budde B., Nürnberg P., Foulquier F., Lefeber D., Urban Z., Gruenewald S., Annaert W., Brunner H. G., van Bokhoven H., et al. (2008) Impaired glycosylation and cutis laxa caused by mutations in the vesicular H+-ATPase subunit ATP6V0A2. Nat. Genet. 40, 32–34 10.1038/ng.2007.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Breton S., and Brown D. (2013) Regulation of luminal acidification by the V-ATPase. Physiology (Bethesda) 28, 318–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stransky L., Cotter K., and Forgac M. (2016) The function of V-ATPases in cancer. Physiol. Rev. 96, 1071–1091 10.1152/physrev.00035.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marrone G., De Chiara F., Böttcher K., Levi A., Dhar D., Longato L., Mazza G., Zhang Z., Marrali M., Fernández-Iglesias A. F., Hall A., Luong T. V., Viollet B., Pinzani M., and Rombouts K. (2018) The AMPK-v-ATPase-pH axis: a key regulator of the pro-fibrogenic phenotype of human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 68, 1140–1153 10.1002/hep.30029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kartner N., and Manolson M. F. (2012) V-ATPase subunit interactions: the long road to therapeutic targeting. Curr. Protein Pept Sci. 13, 164–179 10.2174/138920312800493179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cotter K., Stransky L., McGuire C., and Forgac M. (2015) Recent insights into the structure, regulation, and function of the V-ATPases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40, 611–622 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGuire C., Stransky L., Cotter K., and Forgac M. (2017) Regulation of V-ATPase activity. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 22, 609–622 10.2741/4506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manolson M. F., Wu B., Proteau D., Taillon B. E., Roberts B. T., Hoyt M. A., and Jones E. W. (1994) STV1 gene encodes functional homologue of 95-kDa yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit Vph1p. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14064–14074 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kawasaki-Nishi S., Bowers K., Nishi T., Forgac M., and Stevens T. H. (2001) The amino-terminal domain of the vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase α subunit controls targeting and in vivo dissociation, and the carboxyl-terminal domain affects coupling of proton transport and ATP hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47411–47420 10.1074/jbc.M108310200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Srinivasan S., Vyas N. K., Baker M. L., and Quiocho F. A. (2011) Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic N-terminal domain of subunit I, a homolog of subunit a, of V-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 14–21 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roh S. H., Stam N. J., Hryc C. F., Couoh-Cardel S., Pintilie G., Chiu W., and Wilkens S. (2018) The 3.5-Å cryoEM structure of nanodisc-reconstituted yeast vacuolar ATPase Vo proton channel. Mol. Cell 69, 993–1004.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao J., Benlekbir S., and Rubinstein J. L. (2015) Electron cryomicroscopy observation of rotational states in a eukaryotic V-ATPase. Nature 521, 241–245 10.1038/nature14365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Strahl T., and Thorner J. (2007) Synthesis and function of membrane phosphoinositides in budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 353–404 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Balla T. (2013) Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 93, 1019–1137 10.1152/physrev.00028.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCartney A. J., Zhang Y., and Weisman L. S. (2014) Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate: low abundance, high significance. Bioessays 36, 52–64 10.1002/bies.201300012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jin N., Mao K., Jin Y., Tevzadze G., Kauffman E. J., Park S., Bridges D., Loewith R., Saltiel A. R., Klionsky D. J., and Weisman L. S. (2014) Roles for PI(3,5)P2 in nutrient sensing through TORC1. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1171–1185 10.1091/mbc.e14-01-0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dong X. P., Shen D., Wang X., Dawson T., Li X., Zhang Q., Cheng X., Zhang Y., Weisman L. S., Delling M., and Xu H. (2010) PI(3,5)P(2) controls membrane traffic by direct activation of mucolipin Ca release channels in the endolysosome. Nat. Commun. 1, 38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ferguson C. J., Lenk G. M., and Meisler M. H. (2009) Defective autophagy in neurons and astrocytes from mice deficient in PI(3,5)P2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 4868–4878 10.1093/hmg/ddp460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gary J. D., Wurmser A. E., Bonangelino C. J., Weisman L. S., and Emr S. D. (1998) Fab1p is essential for PtdIns(3)P 5-kinase activity and the maintenance of vacuolar size and membrane homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 143, 65–79 10.1083/jcb.143.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jin N., Jin Y., and Weisman L. S. (2017) Early protection to stress mediated by CDK-dependent PI(3,5)P2 signaling from the vacuole/lysosome. J. Cell Biol. 216, 2075–2090 10.1083/jcb.201611144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Botelho R. J., Efe J. A., Teis D., and Emr S. D. (2008) Assembly of a Fab1 phosphoinositide kinase signaling complex requires the Fig 4 phosphoinositide phosphatase. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 4273–4286 10.1091/mbc.e08-04-0405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bonangelino C. J., Nau J. J., Duex J. E., Brinkman M., Wurmser A. E., Gary J. D., Emr S. D., and Weisman L. S. (2002) Osmotic stress-induced increase of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate requires Vac14p, an activator of the lipid kinase Fab1p. J. Cell Biol. 156, 1015–1028 10.1083/jcb.200201002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duex J. E., Nau J. J., Kauffman E. J., and Weisman L. S. (2006) Phosphoinositide 5-phosphatase Fig 4p is required for both acute rise and subsequent fall in stress-induced phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate levels. Eukaryot. Cell 5, 723–731 10.1128/EC.5.4.723-731.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Choy C. H., Saffi G., Gray M. A., Wallace C., Dayam R. M., Ou Z. A., Lenk G., Puertollano R., Watkins S. C., and Botelho R. J. (2018) Lysosome enlargement during inhibition of the lipid kinase PIKfyve proceeds through lysosome coalescence. J. Cell Sci. 131, pii: jcs213587 10.1242/jcs.213587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li S. C., Diakov T. T., Xu T., Tarsio M., Zhu W., Couoh-Cardel S., Weisman L. S., and Kane P. M. (2014) The signaling lipid PI(3,5)P(2) stabilizes V1-Vo sector interactions and activates the V-ATPase. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1251–1262 10.1091/mbc.e13-10-0563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Banerjee S., and Kane P. M. (2017) Direct interaction of the Golgi V-ATPase α-subunit isoform with PI(4)P drives localization of Golgi V-ATPases in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 2518–2530 10.1091/mbc.e17-05-0316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Finnigan G. C., Cronan G. E., Park H. J., Srinivasan S., Quiocho F. A., and Stevens T. H. (2012) Sorting of the yeast vacuolar-type, proton-translocating ATPase enzyme complex (V-ATPase): identification of a necessary and sufficient Golgi/endosomal retention signal in Stv1p. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 19487–19500 10.1074/jbc.M112.343814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Collins M. D., and Gordon S. E. (2013) Short-chain phosphoinositide partitioning into plasma membrane models. Biophys. J. 105, 2485–2494 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dove S. K., McEwen R. K., Mayes A., Hughes D. C., Beggs J. D., and Michell R. H. (2002) Vac14 controls PtdIns(3,5)P(2) synthesis and Fab1-dependent protein trafficking to the multivesicular body. Curr. Biol. 12, 885–893 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00891-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kelley L. A., Mezulis S., Yates C. M., Wass M. N., and Sternberg M. J. (2015) The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 10.1038/nprot.2015.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baskaran S., Ragusa M. J., Boura E., and Hurley J. H. (2012) Two-site recognition of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate by PROPPINs in autophagy. Mol. Cell 47, 339–348 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. She J., Guo J., Chen Q., Zeng W., Jiang Y., and Bai X. C. (2018) Structural insights into the voltage and phospholipid activation of the mammalian TPC1 channel. Nature 556, 130–134 10.1038/nature26139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yamamoto A., DeWald D. B., Boronenkov I. V., Anderson R. A., Emr S. D., and Koshland D. (1995) Novel PI(4)P 5-kinase homologue, Fab1p, essential for normal vacuole function and morphology in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 525–539 10.1091/mbc.6.5.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wilson Z. N., Scott A. L., Dowell R. D., and Odorizzi G. (2018) PI(3,5)P2 controls vacuole potassium transport to support cellular osmoregulation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 29, 1718–1731 10.1091/mbc.E18-01-0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Compton L. M., Ikonomov O. C., Sbrissa D., Garg P., and Shisheva A. (2016) Active vacuolar H+ ATPase and functional cycle of Rab5 are required for the vacuolation defect triggered by PtdIns(3,5)P2 loss under PIKfyve or Vps34 deficiency. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 311, C366–C377 10.1152/ajpcell.00104.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schulze U., Vollenbroker B., Kuhnl A., Granado D., Bayraktar S., Rescher U., Pavenstadt H., and Weide T. (2017) Cellular vacuolization caused by overexpression of the PIKfyve-binding deficient Vac14L156R is rescued by starvation and inhibition of vacuolar-ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1864, 749–759 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bonangelino C. J., Chavez E. M., and Bonifacino J. S. (2002) Genomic screen for vacuolar protein sorting genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2486–2501 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li S. C., Diakov T. T., Rizzo J. M., and Kane P. M. (2012) Vacuolar H+-ATPase works in parallel with the HOG pathway to adapt Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells to osmotic stress. Eukaryot. Cell 11, 282–291 10.1128/EC.05198-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saito H., and Posas F. (2012) Response to hyperosmotic stress. Genetics 192, 289–318 10.1534/genetics.112.140863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tarsio M., Zheng H., Smardon A. M., Martínez-Muñoz G. A., and Kane P. M. (2011) Consequences of loss of Vph1 protein-containing vacuolar ATPases (V-ATPases) for overall cellular pH homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 28089–28096 10.1074/jbc.M111.251363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hansen S. B., Tao X., and MacKinnon R. (2011) Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature 477, 495–498 10.1038/nature10370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang X., Zhang X., Dong X. P., Samie M., Li X., Cheng X., Goschka A., Shen D., Zhou Y., Harlow J., Zhu M. X., Clapham D. E., Ren D., and Xu H. (2012) TPC proteins are phosphoinositide-activated sodium-selective ion channels in endosomes and lysosomes. Cell 151, 372–383 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jha A., Ahuja M., Patel S., Brailoiu E., and Muallem S. (2014) Convergent regulation of the lysosomal two-pore channel-2 by Mg2+, NAADP, PI(3,5)P(2) and multiple protein kinases. EMBO J. 33, 501–511 10.1002/embj.201387035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Naufer A., Hipolito V. E. B., Ganesan S., Prashar A., Zaremberg V., Botelho R. J., and Terebiznik M. R. (2018) pH of endophagosomes controls association of their membranes with Vps34 and PtdIns(3)P levels. J. Cell Biol. 217, 329–346 10.1083/jcb.201702179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ho C. Y., Choy C. H., Wattson C. A., Johnson D. E., and Botelho R. J. (2015) The Fab1/PIKfyve phosphoinositide phosphate kinase is not necessary to maintain the pH of lysosomes and of the yeast vacuole. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 9919–9928 10.1074/jbc.M114.613984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jin N., Lang M. J., and Weisman L. S. (2016) Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate: regulation of cellular events in space and time. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 44, 177–184 10.1042/BST20150174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Manolson M. F., Proteau D., Preston R. A., Stenbit A., Roberts B. T., Hoyt M. A., Preuss D., Mulholland J., Botstein D., and Jones E. W. (1992) The VPH1 gene encodes a 95-kDa integral membrane polypeptide required for in vivo assembly and activity of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 14294–14303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sikorski R. S., and Hieter P. (1989) A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Deleted in proof.

- 59. Liu M., Tarsio M., Charsky C. M., and Kane P. M. (2005) Structural and functional separation of the N- and C-terminal domains of the yeast V-ATPase subunit H. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36978–36985 10.1074/jbc.M505296200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., and Randall R. J. (1951) J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kane P. M., Kuehn M. C., Howald-Stevenson I., and Stevens T. H. (1992) Assembly and targeting of peripheral and integral membrane subunits of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 447–454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Diakov T. T., and Kane P. M. (2010) Regulation of vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase activity and assembly by extracellular pH. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23771–23778 10.1074/jbc.M110.110122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lötscher H. R., deJong C., and Capaldi R. A. (1984) Interconversion of high and low adenosinetriphosphatase activity forms of Escherichia coli F1 by the detergent lauryldimethylamine oxide. Biochemistry 23, 4140–4143 10.1021/bi00313a020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., and Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vida T. A., and Emr S. D. (1995) A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 128, 779–792 10.1083/jcb.128.5.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.