Abstract

AKI is a global concern with a high incidence among patients across acute care settings. AKI is associated with significant clinical consequences and increased health care costs. Preventive measures, as well as rapid identification of AKI, have been shown to improve outcomes in small studies. Providing high-quality care for patients with AKI or those at risk of AKI occurs across a continuum that starts at the community level and continues in the emergency department, hospital setting, and after discharge from inpatient care. Improving the quality of care provided to these patients, plausibly mitigating the cost of care and improving short- and long-term outcomes, are goals that have not been universally achieved. Therefore, understanding how the management of AKI may be amenable to quality improvement programs is needed. Recognizing this gap in knowledge, the 22nd Acute Disease Quality Initiative meeting was convened to discuss the evidence, provide recommendations, and highlight future directions for AKI-related quality measures and care processes. Using a modified Delphi process, an international group of experts including physicians, a nurse practitioner, and pharmacists provided a framework for current and future quality improvement projects in the area of AKI. Where possible, best practices in the prevention, identification, and care of the patient with AKI were identified and highlighted. This article provides a summary of the key messages and recommendations of the group, with an aim to equip and encourage health care providers to establish quality care delivery for patients with AKI and to measure key quality indicators.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury; acute renal failure; ADQI; Prevention; Management; Quality Improvement; Incidence; Pharmacists; Acute Disease; Goals; Inpatients; Patient Discharge; Quality of Health Care; hospitalization; Health Care Costs; Nurse Practitioners; Emergency Service, Hospital

Introduction

AKI is a common complication of acute illnesses with a substantial impact on clinical outcomes and health care costs (1–3). Literature highlights that AKI and its progression could be prevented in some circumstances, and its consequences could be mitigated by timely and effective care measures (4–6). However, care pathways for patients with AKI are not well defined. It is very likely that considerable variability in clinical practices has led to differences in the incidence and outcomes of AKI in different medical centers (7,8). In addition, most institutions do not track adherence with process measures that might impact on the care of patients with AKI. Thus, a critical step in improving the outcome of patients at risk of or with AKI is to identify quality indicators and care pathways that optimize care (Figure 1, Supplemental Appendix 1) (9).

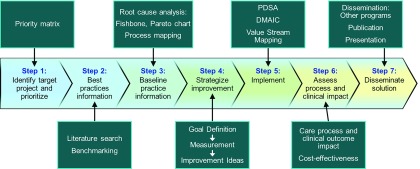

Figure 1.

Seven steps need to be taken for a successful quality improvement project. Supplemental Appendix 1 provides definitions, templates, and examples. DMAIC, Define, Measure, Analyze, Implement, Control; PDSA, Plan, Do, Study, Act. Reprinted from Acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) (12), with permission.

Quality indicators represent the measurement, monitoring, evaluation, and communication of targeted areas of care processes that assess whether and how often the system does what it is intended to do. Quality indicators are framed as determining the structure (i.e., where health care is delivered), process (i.e., how health care is provided), and outcomes (i.e., the effects of health care delivery) of health care systems (Table 1) (10). A challenge in the field of AKI care has been identifying evidence-based quality indicators that guide optimal care as well as recognize opportunities for continuous quality improvement (11). The lack of quality indicators contributes to considerable variation in care and difficulty in studying what interventions may lead to improved outcomes. For instance, patients with AKI often have missed opportunities that otherwise may limit their risk of AKI development or progression. These missed opportunities could be recognized and measured to facilitate development of process improvement strategies. Development of quality indicators must be conducted in a comprehensive manner and started at the community level and continued through and after hospital admission as this represents the spectrum of AKI care continuity (Figure 2). In addition, AKI quality improvement should be evidence-based where possible and responsive to emerging data, despite the fact that current level of knowledge may be limited in its scope for prevention, management, and treatment of AKI.

Table 1.

Quality indicators

| Quality Indicators | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Structure measures | Structure of care is a feature of a health care organization related to the capacity to provide high-quality health care | Does the health care organization or unit use a Computerized Physician Order Entry? |

| Does the health system have an electronic health record system? | ||

| Do AKI care pathways/bundles exist in the health care system? | ||

| Process measures | A health care–related activity performed for, on behalf of, or by a patient | Percentage of patients who were correctly identified as patients at risk of AKI at hospital admission |

| Outcome measures | An outcome of care is a state of health of a patient resulting from health care | Percentage of patients who developed AKI among the patients at risk of AKI |

| Percentage of patients with AKI that had a medication review for nephrotoxicity | ||

| Access measures | Access to care is the attainment of timely and appropriate health care by patients or enrollees of a health care organization or clinician | Percentage of patients who had a timely nephrology consult |

| Patient experience measures | Experience of care is a patient’s or enrollee’s report of observations of and participation in health care, or any resulting change in their health | Percentage of patients who reported how often their doctors communicated well |

| Balancing measures | Unintended and/or wider consequences of the change that can be positive or negative | Overwhelming nephrology clinics by referring patients with AKD for follow-up |

AKD, acute kidney disease.

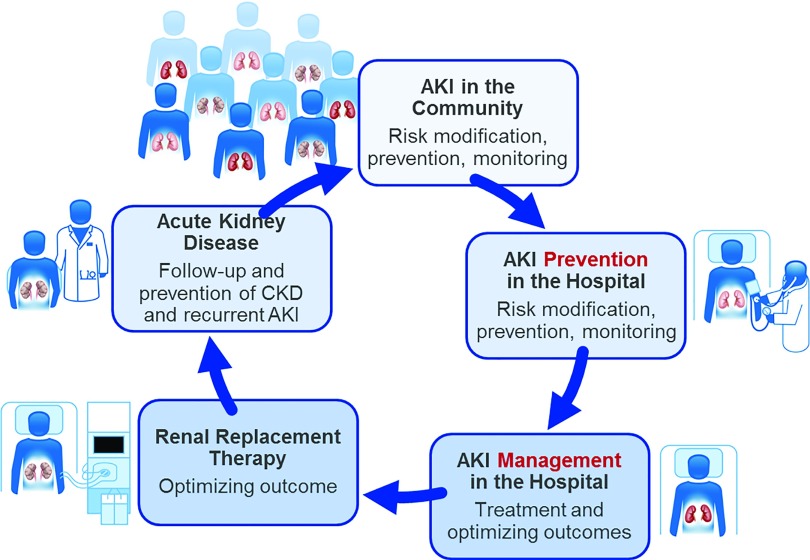

Figure 2.

AKI quality care in a continuity. Reprinted from Acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) (12), with permission.

To achieve a framework for improvement in AKI care, the 22nd Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) conference was convened. The work was divided into five separate groups that captures the spectrum of AKI care (Figure 2, Table 2). Supplemental Appendix 2 provides details on the ADQI consensus conference, Supplemental Table 1 provides definitions, and Supplemental Table 2 outlines requirements for AKI quality care that were developed as a framework for quality indicators.

Table 2.

22nd ADQI groups and objectives

| Group | Assignment | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| I | Primary prevention: community | Provide consensus recommendation to mitigate the risk of AKI in the populations of resource-limited or resource sufficient environments |

| Current best practices at the community levels | ||

| Novel strategies to detect higher risk patients, raising awareness, communicating with primary physicians, and legislative strategies to achieve the goals | ||

| II | Primary prevention: hospital | Provide recommendations regarding the AKI risk modification and primary prevention following medical encounters |

| Strategies for optimization of AKI prevention before its occurrence | ||

| Risk stratification, early detection, use of biomarkers or other novel risk detecting tools, and optimal management | ||

| III | Secondary prevention | Provide recommendations about quality indicators to mitigate the effect of AKI after its occurrence (secondary prevention) |

| Indicate the best practices in the management of patients with AKI in different stages | ||

| IV | Quality improvement of KRT programs | Provide an approach to improve quality of care and safety measures of KRT provided for AKI |

| Recommendations regarding how to enhance the quality of KRT to comply with current or future knowledge | ||

| Structure, process, and outcomes of KRT Programs | ||

| V | Tertiary prevention after hospital | Provide recommendations regarding the quality of care and safety measures for the care of patients during AKD phase (7–90 d after AKI) |

| Identify the quality indicators that are acceptable for the management of patients with AKI beyond the index hospitalization (tertiary prevention) | ||

| Standardized to optimize the follow-up visits and short- and long-term outcomes of patients with AKI |

ADQI, Acute Disease Quality Initiative; AKD, acute kidney disease; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

Community Health Care Standards for AKI

Question 1: At the Community Level, What Are the Roles and Responsibilities of Clinicians and Health Care Systems in AKI Risk Monitoring and Mitigation?

Consensus Statement A.

Healthcare systems and healthcare professionals should identify populations and patients at risk of AKI and implement monitoring and preventive interventions to decrease the incidence of AKI.

Consensus Statement B.

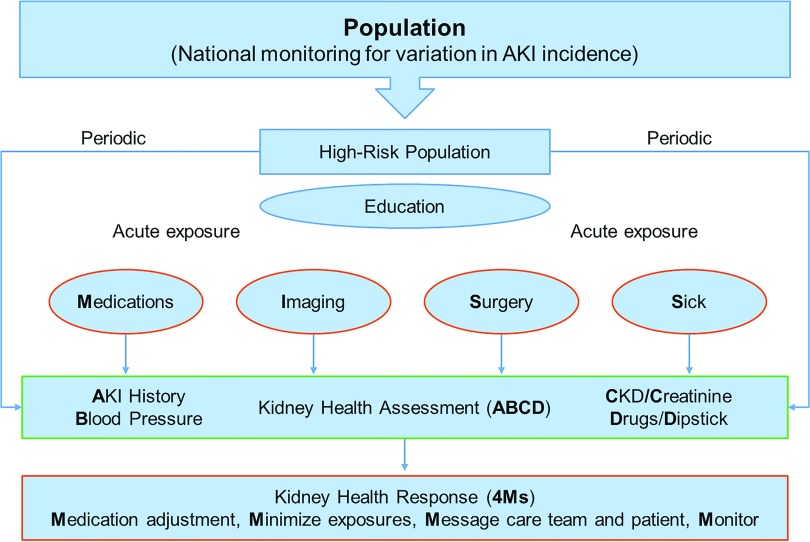

We suggest that a minimum set of baseline risk factors and acute exposures (Figure 3) be considered for AKI risk stratification.

Figure 3.

KHA and response. KHA includes AKI history, BP, CKD, serum Creatinine level, Drug list, and urine Dipstick (ABCD). Exposures include Nephrotoxic Medications, Imaging, Surgery, Sickness (NISS). KHR (4Ms) that encompasses Medication review to withhold unnecessary medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [16,17]), the Minimization of nephrotoxic exposures (e.g., intravenous contrast [18]), Messaging the healthcare team and patient to alert the high risk of AKI, and Monitoring for AKI and its consequences. Reprinted from Acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) (12), with permission.

At least 50% of AKI episodes begin in the community setting (13,14). The initial step toward quality improvement in this setting begins with identifying high-risk populations (defined in Supplemental Table 1) for which monitoring and preventive strategies should be targeted (Figure 3). The definition of high risk may vary according to the local prevalence of different AKI risk factors. These risks can be categorized into five dimensions of inherent and nonmodifiable (for example, age), exposure-based (such as administration of nephrotoxic medications), processes of care (such as failure to identify AKI), socioeconomic-cultural (such as access to care), and environmental (such as exposure to environmental toxins) (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1) (15). Although governmental systems should focus on identifying and managing environmental and socioeconomic-cultural risks, clinicians should focus on individual patient risks that may be detectable and modifiable. Raising awareness regarding AKI risk factors among health care professionals and patients by education and establishment of tools that measure these risk profiles for each individual are considered crucial steps in mitigating AKI incidence.

Question 2: How Should AKI High-Risk Populations Be Monitored?

Consensus Statement A.

We suggest populations/patients at high risk for developing AKI should have a Kidney Health Assessment (KHA) at least every 12 months to define and modify their AKI risk profile.

Consensus Statement B.

We suggest that high-risk patients have another KHA at least 30 days before AND again 2–3 days after a planned exposure that carries AKI risk. The KHA can be tailored to the clinical context and clinician/health care system judgment.

Consensus Statement C.

We suggest that clinicians review a patient’s KHA immediately after an unplanned acute exposure that carries AKI risk.

Literature is limited regarding AKI risk monitoring (19). We suggest that basic risk assessment and care management elements relevant to high-risk patients be considered the minimum standard of care. These elements are synthesized into a KHA. The minimal KHA is outlined in Figure 3. Adherence with and timeliness of the KHA could be used as a quality indicator measurement. For instance, practices should monitor the proportion of patients at high risk for AKI who have documented KHA in their health records.

Question 3: How Can AKI Preventive Strategies Be Implemented within High-Risk Populations?

Consensus Statement A.

KHA should be followed by a Kidney Health Response (KHR) after acute exposure to risk factors of AKI.

Consensus Statement B.

We suggest raising awareness of the definition, signs, symptoms, and acute exposures associated with AKI among clinicians and high-risk patients/populations.

Consensus Statement C.

We suggest enhanced coordination between all stakeholders to monitor the rate, causes, and outcomes of AKI to identify variations in care and outcomes across and between the populations.

The KHA is a “living document” and should be reviewed after acute AKI exposures (20) and updated with new knowledge. This step should then be followed by a KHR (Figure 3). Quality indicators could include adherence with key elements of the KHR as well as the rate of AKI after high-risk exposures. With the emergence of new knowledge, components of KHA (related to patient and population condition) and KHR (indicator of physician task list) need to be updated. The national/local health care system engagement in quality improvement projects is of importance (Figure 3) (21). The effect of environmental factors (e.g., climate, water quality) and the social and behavioral determinants of health (e.g., nutrition, health insurance) on the incidence of AKI are well documented (15,22), and governing bodies have a responsibility to monitor AKI risks and coordinate preventive strategies (23).

Primary Prevention of AKI during a Hospital Encounter

Question 1: How and When Should the Risk for AKI Be Identified among Hospitalized Patients?

Consensus Statement A.

All patients at hospital admission should be screened for risk of AKI. Screening should occur at the earliest possible time throughout the patient’s hospital stay.

Consensus Statement B.

All patients at risk for AKI should at least have an assessment of serum creatinine, urine dipstick analysis, and urine output. Complementary diagnostic tests depending on local availabilities, risk factors, clinical context, and clinician judgment should be considered.

Consensus Statement C.

All hospitalized patients should have periodic risk reassessment using appropriate clinical or electronic models before and after risk exposure or change in clinical status.

Because of multiple exposures, hospitalized patients are at higher risk of AKI in comparison with individuals in the community, regardless of their baseline risk. Therefore, hospitalized patients require more detailed and frequent evaluation when compared with high-risk individuals in the community. Early and frequent screening of hospitalized patients for the risk of AKI should occur. This screening may use validated risk assessment models (24) or automated surveillance tools (25), but at a minimum an assessment should identify susceptibilities and exposures that could lead to AKI (Table 3) (26,27). The intensity, frequency, and duration of monitoring should be individualized according to patient characteristics and local resources.

Table 3.

AKI risk assessment among hospitalized patients

| Risk Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Comorbid conditions | CKD |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Heart failure | |

| Liver disease | |

| History of AKI | |

| Anemia | |

| Neurologic for cognitive impairment or disability | |

| Illnesses | Sepsis |

| Rhabdomyolysis | |

| Hemorrhage | |

| Hemolysis | |

| ARDS | |

| Severe diarrhea | |

| Hematologic malignancy | |

| Trauma | |

| Symptoms and signs | Hypotension and hypovolemia |

| Hypertension and fluid overload | |

| Oliguria (urine output <0.5 ml/kg per h) | |

| Symptoms/history of urological obstruction or conditions that may lead to obstruction | |

| Symptoms or signs of glomerulo-interstitial nephritis (e.g., edema, hematuria) | |

| Others | Use of KENDs within a week before admission |

KEND medications include (1) cleared by the kidney but not nephrotoxic (e.g., digoxin), (2) cleared by the kidney and nephrotoxic (e.g., vancomycin), and (3) not cleared by the kidney but are nephrotoxic (e.g., calcineurin inhibitors). KEND, kidney eliminated and nephrotoxic drugs; ARDS, adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Question 2: What Core Preventive Measures Should Be Considered as a Target for Quality Improvement Projects?

Consensus Statement A.

Early correction or mitigation of context-specific modifiable risk factors of AKI should be considered for all high-risk patients.

AKI has been shown to be preventable in recent studies (4,5). Increasing awareness among clinicians regarding the risks and management strategies would most likely result in improved care. The most common conditions leading to AKI include (1) critical illnesses, (2) major surgical procedures, and (3) exposure to nephrotoxic drugs. Optimization of hemodynamic and volume status and avoidance of nephrotoxic insults remain the mainstay of primary prevention. However, to understand the optimal management strategies and targets, further studies are required (26,28).

Question 3: What Are the Quality Indicators for Assessing Risk of AKI?

Consensus Statement A.

The quality indicators for AKI prevention in the hospital should include (1) proportion of patients screened for AKI risk among all admissions, (2) proportion of identified AKI high-risk patients among all screened patients, (3) proportion of AKI high-risk exposures (e.g., medication, contrast, surgery) among all hospitalized population and all high-risk patients, (4) proportion of patients who received an appropriate intervention around a high-risk exposure, and (5) proportion of patients who developed AKI (community- or hospital-acquired; as defined in Supplemental Table 1) among all admissions (in different subpopulations) and all high-risk patients.

Consensus Statement B.

The quality indicators should be reviewed and utilized to identify areas of improvement and action. The frequency of reporting should be defined according to local resources and regulatory requirements.

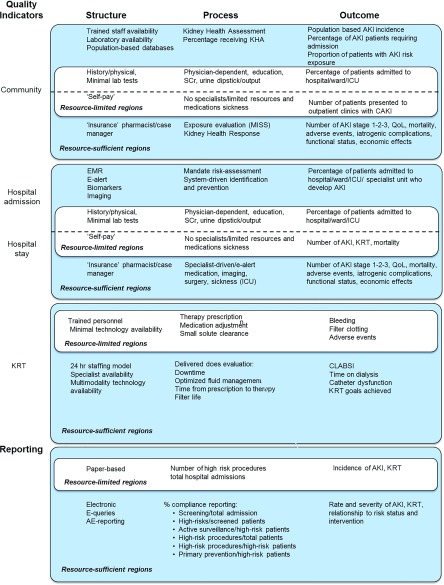

Identification of valid quality indicators of care is essential to measure, monitor, benchmark, and target the improvement. Quality indicators may include health care infrastructure and access, processes of care, outcomes, and clinician or patient experience (Supplemental Figure 2). It is recognized that these measures vary depending on the health care system, local resources, geography, and socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors (Figure 4). Future investigations should focus on identifying valid and globally applicable AKI risk scoring systems using available and novel tools (e.g., electronic health records, biomarkers).

Figure 4.

Factors related to quality indicators and reporting can be divided in structure, process, and outcome in community, hospital, and after initiation of KRT. Clearly, different levels exist depending on resource possibilities. For example, resource-sufficient areas may have access electronic medical records, allowing system-driven identification and prevention and more detailed outcome reporting of patients with AKI. Embedded in these is a basic level of quality measures and level of reporting that should be feasible in both resource-limited and research-sufficient areas (white boxes). AE, adverse event; EMR, Electronical Medical Record; ICU, intensive care unit; Scr, serum creatinine; QoL, quality of life; KRT, kidney replacement therapy. Reprinted from Acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) (12), with permission.

Secondary Prevention of AKI

Question 1: What Are the Key Considerations for Developing Quality Programs that Evaluate Contributors to an Episode of AKI?

Consensus Statement A.

We propose that for each patient diagnosed with AKI during hospitalization, the goal is recovery to baseline kidney function in the shortest period of time with minimum number of complications. This is best achieved by timely and accurate diagnosis and management of AKI, and prevention of complications. These goals might be achieved by using a Recognition-Action-Results framework (Table 4).

Table 4.

Recognition-Action-Result framework for secondary prevention of AKI, including diagnosis and evaluations, limiting duration and severity of AKI, and prevention of avoidable complications associated with AKI

| Framework | Diagnosis and Evaluation | Limiting Severity and Duration of AKI | Prevention of Avoidable AKI Complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition | AKI stage-dependent threshold met | Nephrotoxin or contributing medication | AKI has occurred |

| Poor hemodynamics | High frequency of hyperkalemia in patients with AKI | ||

| Cause-specific diagnosis delayed | Poor extubation rates in patients with AKI due to volume overload | ||

| Adverse drug events | |||

| Action | Context-appropriate evaluation | “Nephrotoxin stewardship” | Improved monitoring for complications (e.g., BMP/bicarbonate/phosphorus measurement) |

| Physical examination | Asses and optimize hemodynamics | Risk reduction strategies (e.g., reduced potassium intake, unnecessary maintenance fluids, review of appropriate dosing of meds) | |

| History | Invasive/noninvasive | Management of complications (e.g., treatment of hyperkalemia, fluid removal) | |

| Kidney function and injury biomarkers | Avoid hyperglycemia | ||

| Urine analysis | Nephrology referral guidelines | ||

| Hemodynamic variables | Monitoring of kidney function with serum creatinine and urine output | ||

| Radiology and serology tests | |||

| Kidney biopsy | |||

| Other context-specific tests | |||

| Results | Improved frequency of context-appropriate diagnostic evaluation | Improved rates of nephrotoxin alerting/evaluation/discontinuance | Process (improved monitoring/detection, reduction in unnecessary potassium supplementation, med reconciliation/evaluation) |

| Improved recognition of cause-specific AKI | Hemodynamic intervention applied | Clinical (reduced incidence of severe hyperkalemia, treatment of severe acidosis pH<7.2, less adverse drug events related to inappropriate drug dosing/selection in AKI) | |

| Improved timeline of cause-specific diagnosis/interventions | |||

| Reduced duration and severity of AKI (e.g., maximum stage, length, recovery) |

BMP, basic metabolic panel.

Consensus Statement B.

Quality improvement surrounding the diagnostic evaluation of AKI should attempt to maximize the proportion of patients who undergo a context-appropriate and timely evaluation while avoiding unnecessary testing.

The timely and accurate identification of reversible causes of AKI, if promptly addressed, potentially reduces the severity and duration of disease and associated complications (secondary prevention of AKI) (29). Quality improvement initiatives surrounding the diagnostic evaluation of AKI should be developed within the contexts of clinical setting (e.g., community- versus hospital-acquired, medical versus postsurgical); the distribution of underlying causes, trajectory, and severity at the time of AKI identification; and the goals and capabilities of the health care systems (30). Although the heterogeneity of AKI and lack of available evidence do not support the notion that all patients with AKI require the same breadth or intensity of evaluation, clinical practice guidelines and expert opinion generally favor a stepwise approach (Table 4) (15,26,29,31–34). We recommend development of quality initiatives surrounding diagnostic evaluation considering the clinical context and the likelihood of identifying actionable causes in a timely and context-specific manner (Supplemental Table 3, Table 4).

Question 2: What Are the Key Considerations for Developing Quality Improvement Programs Focused on Limiting the Duration and Severity of AKI?

Consensus Statement A.

Quality improvement programs should include the implementation and reporting of the proportion of patients that receive timely and diagnosis-appropriate interventions. Adherence with the locally agreed upon preventive interventions should be audited and shared with clinicians periodically.

Reducing the severity and duration of AKI rests on timely and effective management of the underlying causes and reduction in modifiable determinants of ongoing injury. Quality programs may focus on instituting general “nephroprotective” interventions, such as timely hemodynamic resuscitation, nephrotoxin stewardship, or cause-specific interventions (e.g., relief of obstruction, immunosuppression, and others) (4,5,35). Recently, “bundled AKI care pathways” have shown promise in preventing AKI and reducing its severity, but more research is required to better define effective care components (4,36,37). In cases where context-appropriate evaluation identifies a cause warranting targeted therapy, the timeliness and appropriate application of cause-specific management could be measured as quality indicators (Supplemental Table 4, Table 4).

Nephrotoxin exposure accounts for up to 28% of potential adverse drug events leading to AKI and is a potential target for quality improvement (38). Analogous to antimicrobial stewardship programs, the concept of nephrotoxin stewardship encompasses coordinated interventions designed to decrease nephrotoxin exposure among patients at risk for or with AKI (39,40). This provides a framework for the development of institution-specific guidelines for the safe and effective use of Kidney Excreted and Nephrotoxic Drugs. Recently, the Nephrotoxic Injury Negated by Just-in-time Action program demonstrated that the systematic review of nephrotoxins by a multidisciplinary care team resulted in a sustained reduction in nephrotoxin exposure, AKI rate, and severity (41). Similar programs have been tested in adults and resulted in favorable outcomes (4,5,33,42,43). The implementation of these programs must consider the health care system capabilities and the risk–benefit of withholding potentially beneficial nephrotoxins used to treat serious conditions. Within resource-limited areas, dedicating efforts in training appropriate staff (e.g., house staff, nurses, etc.) and reviewing medication lists could potentially provide a similar benefit.

Question 3: What Are the Key Considerations for Developing Quality Improvement Programs Focused on Reducing the Complications of AKI?

Consensus Statement A.

Quality indicators for prevention of avoidable AKI-related complications include monitoring, reporting the context-specific adverse events (to patient advocates, clinicians, administrators, and regulatory bodies), and implementation of risk reduction strategies.

Uremic related complications of AKI and risks associated with initiation of KRT (bloodstream infection, electrolyte abnormalities, hypotension, etc.) or other AKI-related management options (diuresis, withholding nephrotoxins, etc.) should be monitored and reported. We propose that quality programs focus on determining the incidence of complications to appropriately guide effort allocation to the monitoring complications (i.e., recognition of hyperkalemia), the response (e.g., action to treat it), and whether risk reduction strategies are in place (e.g., low potassium diet, no potassium maintenance in fluids) (Supplemental Table 5, Table 4).

Kidney Replacement Therapy Quality Indicators

Consensus Statement A.

Quality indicators should integrate structure, process, and outcome indicators for each therapeutic modality.

There is limited data on acute kidney replacement therapy (KRT) quality indicators, along with numerous challenges with respect to quality and safety in the provision of acute KRT care (44). All institutions that provide acute KRT should adopt and implement a quality framework around these services. This should include integration, monitoring, and reporting of structure, process, and outcome indicators across all forms of acute KRT therapies (Figure 4) (45). Benchmarks for each quality indicator should be determined to provide information about patient-specific and aggregate institutional quality of care. Multicenter, acute KRT registries should be created to further develop and refine quality improvement projects that develop target benchmarks for clinical practice guidelines.

Question 2: What Are the Minimum Structure Quality Indicators that Should Be Implemented for Acute KRT?

Consensus Statement A.

Structural quality indicators should specifically target clinician, nursing, and allied health professionals’ capacity and expertise for providing acute KRT and identify a responsible team to implement and report quality metrics for acute KRT services.

Institutions that provide acute KRT should establish standards for structural quality indicators that incorporate evaluation of resource availability and the infrastructure needed for acute KRT. At a minimum, this should include a dedicated team comprising expert clinicians, nurses, and allied professionals (i.e., biomedical engineer, pharmacist) that are responsible for patient monitoring, reporting data, and design and implementation of quality care processes for each acute KRT modalities.

Question 3: What Are the Minimum Process Quality Indicators that Should Be Implemented for the Provision of Acute KRT?

Consensus Statement A.

Process quality indicators should incorporate methodologies that lead to standardized protocols and procedures, allowing for increased efficiency and consistency in care and safety, and should be specific to each KRT modality.

Institutions providing acute KRT should incorporate standardized clinical protocols and procedures for each KRT modality to deliver consistent and safe care. Key measures of KRT adequacy should be measured routinely (Figure 4). Implementation of quality improvement methodologies should be conducted when there are significant deviations in the provided care (Supplemental Figure 3). Root cause analyses should be used to investigate deviations in practice and to identify care gaps when they occur (Supplemental Figure 4). Future studies should further evaluate, validate, and prioritize specific process quality indicators.

Question 4: What Are the Minimum Outcome Indicators that Should Be Implemented for the Provision of Acute KRT?

Consensus Statement A.

Outcome quality indicators should include patient-centered outcomes, including clinician and patient satisfaction, mortality, and quality of life among survivors; dialysis liberation rates; and health-economic outcomes.

Programs providing acute KRT should integrate, monitor, and report outcome indicators for acute KRT. The monitoring of adverse events is vital to ensure that acute KRT is being delivered in a safe and high-quality manner. Future work should evaluate the association of specific outcome quality and value indicators (i.e., health care costs) for patients, institutions, and health care systems. Evaluating target benchmarks for each quality indicator that can inform patient-specific and aggregate institutional quality of care is crucial for future work.

Tertiary Prevention of AKI Short- and Long-Term Complications

Question 1: How Should the Appropriate Post-AKI/Acute Kidney Disease Care Be Measured?

Consensus Statement A.

Health care systems need to quantitate the proportion of patients who need post-AKI/acute kidney disease (AKD) follow-up, those who receive any post-AKI/AKD follow-up, and evaluate quality of care for those who received post-AKI/AKD follow-up.

Tertiary prevention of AKI should focus on maintenance and/or improvement in quality of life after AKI to mitigate long-term disabilities resulting from AKI. In this regard, current data on post-AKI/AKD follow-up is very limited. The first step to improve quality in this domain is to systematically measure the proportion of patients who receive post-AKI/AKD follow-up care. There is no current standardized definition of “appropriate” AKI-AKD follow-up care, and it varies from no follow-up to a simple serum creatinine check to a nephrology clinic visit. In a report of post-AKI care, only 3% (low-risk patients) to 24% (individuals with both diabetes and CKD) were followed by a nephrologist within 6 months of their AKI episode (46,47). Furthermore, rates of kidney-related laboratory testing after hospital discharge are low. For example, in the United States in 2013, follow-up creatinine measurements occurred only in 54% of patients (46). In addition to determination of those who need follow-up, the setting (i.e., dedicated post-AKI nephrology clinic versus primary care follow-up), timeline (e.g., immediately after hospital discharge or 3 months after AKI episode), and frequency (e.g., weekly or annually) of appropriate post-AKI follow-up also depends on the severity of the initial AKI/AKD and the health care system resources (Figure 5). In follow-up, a multidisciplinary approach (pharmacy, dietician, social work, primary care, nephrology, non-nephrology subspecialists) is recommended. We recommend all patients with dialysis-requiring AKI/AKD or patients with AKI/AKD superimposed on advanced CKD should be followed by a nephrologist at least within 2–3 months after their hospitalization, depending on the severity and acute needs. Future research should focus on the definition of appropriate AKI-AKD follow-up on the basis of severity and cause of AKI, and health care system capabilities. Identifying the patients/populations who benefit the most from follow-up (e.g., AKI cause and severity) and barriers to post-AKI/AKD follow-up care are critical next steps in AKI research and quality improvement.

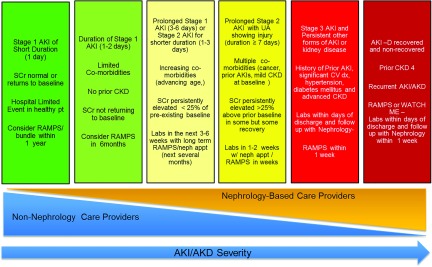

Figure 5.

Schematic for AKI/AKD follow-up. The figure displays a potential paradigm for the care of patients who experience AKI/AKD. The degree of nephrology-based follow-up increases as the duration and severity of AKI/AKID increases. The timing and nature of follow up are suggestions as there is limited data to inform this process. Future research effort should work to clarify the timing and health care providers who should be providing AKI/AKD follow-up. The items in each bucket follow the “OR” rule; therefore, each patient should follow the most severe bucket if even meet one criteria of that bucket (e.g., patient with CKD stage 4 regardless of severity of AKI should be followed by nephrologist in 1 week). Reprinted from Acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) (12), with permission.

Question 2: What Are the Key Elements of an Appropriate Post-AKI/AKD Care Bundle?

Consensus Statement A.

Quality indicators should at least include structure (needed personnel and resources), process for follow-up (who and by whom, what, where, when, why, and how), and outcome indicators (CKD progression, continued or new need for dialysis, mortality, etc.).

We recommend the following key components for a post-AKI/AKD bundle that should be a more comprehensive version of KHR: (1) KAMPS (Kidney function, Advocacy, Medications, Pressure, Sick day protocol) for all patients with AKI, and (2) WATCH-ME (Weight assessment, Access, Teaching, Clearance, Hypotension, Medications) for patients with AKI who require dialysis (Table 5). For patients with AKI who require dialysis, care bundles that are appropriate for ESKD may not apply (e.g., early placement of an arteriovenous fistula or graft may be inappropriate for AKI). Quality indicators should be tied to patient and hospital-centered outcomes such as readmission rate and quality of life.

Table 5.

Post AKI/AKD kidney health care bundle

| Framework | Components |

|---|---|

| KAMPS | |

| Kidney function check | Kidney function measurement by serum creatinine or cystatin C; measured GFR or eGFR |

| Proteinuria/albuminuria | |

| When available consider biomarkers, imaging and other tests as feasible and indicated | |

| Advocacy | Patient and caregiver education about AKI and CKD |

| Communication with other care providers (i.e., general practitioners, dieticians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers) | |

| Medications | Medication reconciliation, review, and management |

| Specifically discuss risk benefits of ACEI/ARB/MRA/diuretics | |

| Review RENDs and over the counter medications | |

| Pressure | Ensure patient understands BP goals and targets |

| Discuss fluid status, ideal weight, role of diuretics | |

| Sick day protocols | Educate patients on medications that need monitoring during acute illnessesa |

| Consider protocols to withhold KENDs | |

| WATCH-ME | |

| Weight assessment | Discuss dry weight monitoring and permissive hypervolemia |

| Discuss the role for diuretics in maintaining urine output and ideal volume status | |

| Access | Educate patients about the care of central venous catheters |

| Vein preservation protocols/awareness | |

| When appropriate begin to plan and educate about the role of arteriovenous access and other KRT modalities | |

| Teaching | Patient and caregiver education about dialysis requiring AKD and short- and long-term risks and consequence |

| Communication with other care providers (e.g., general practitioners, dieticians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers) about patient needs (e.g., alterations in medication regimens in the setting of new KRT). | |

| Clearance | Frequent assessments of underlying kidney function (via predialysis laboratory tests or timed clearances) |

| Frequent assessments of the quality of the KRT being provided to ensure adequate clearance | |

| Hypotension | Patient education and optimization of care to avoid intradialytic about hypotension |

| Education around BP medications administration in the peri-KRT period | |

| Medications | Medication reconciliation, review, and management |

| Specifically discuss risk benefits of ACEI/ARB/MRA | |

| Review KENDs and over the counter medications |

AKD, acute kidney disease; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; KEND, kidney eliminated and nephrotoxic drugs; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

Patient education should include but not limited to the signs of AKI recurrence or CKD progress, potential need for future dialysis modalities and its alternatives, information about their medications, and contact information for the clinicians in case of question.

Future research should include the use of measures of kidney functional reserve, real-time GFR monitoring, and other novel biomarkers in the post-AKI/AKD setting that correlate with outcomes of interest. In addition, research should focus on optimal management strategies for each component of the KAMPS/WATCH-ME bundles and the development and validation of novel and effective bundle components.

Determination of factors that predict and promote kidney recovery and mitigate CKD development and appropriate implementation of such interventions would also improve quality of care after AKI.

Conclusions

Strategizing improvement in care for AKI requires prioritization and implementation of focused quality improvement projects including all types of health care providers along with change management to leverage the current and future knowledge in the betterment of care. The AKI care process starts with the community, continues in the hospital, and ends in community, and each of these phases requires specific intervention. The group has suggested outlines for the care of individuals in each phase, to focus, enhance, and study quality indicators.

Disclosures

Dr. Bagshaw reports grants and personal fees from Baxter Healthcare Corp., during the conduct of the study. Dr. Barreto reports personal fees from FAST Biomedical, outside the submitted work. Dr. Bihorac reports grants from Astute Medical, grants from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, grants from La Jolla Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Atox Bio, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Bihorac has a patent 1. Method and Apparatus for Prediction of Complications after Surgery Application Number PCT/IB2018/053956; Filed June 1, 2018/IB 049648/514983; pending, a patent 2. Method and Apparatus for Pervasive Patient Monitoring Application Number 62/659,948, filed April 19, 2018 A&B 049648/513825 pending, and a patent 1. Systems and Methods for Providing an Acuity Score for Critically Ill or Injured Patients Provisional Application Number 62/809,159, filed February 22, 2019 A&B Ref. 049648/526813 pending. Dr. Forni reports grants from Baxter, personal fees from Biomerieux, personal fees from Medibeacon, personal fees from Baxter, other from Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, outside the submitted work. Dr. Haase reports personal fees from Abbott, personal fees from Alere, personal fees from Astute, personal fees from Baxter, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Siemens, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kellum reports grants and personal fees from Astute Medical, grants and personal fees from Baxter, grants from Bioporto, personal fees from Adrenomed, personal fees from Davita, personal fees from NxStage, grants from RenalSense, outside the submitted work. Dr. Koyner reports personal fees from Astute Medical, personal fees from Baxter, personal fees from Sphingotec, grants from Nxstage Medical, grants from Satellite Health Care, personal fees from American Society of Nephrology, outside the submitted work. Dr. Liu reports personal fees from Durect, personal fees from Z S Pharma, personal fees from Theravance, personal fees from Quark, personal fees from Potrero Med, other from Amgen, personal fees from American Society of Nephrology, personal fees from National Kidney Foundation, personal fees from National Policy Forum on Critical Care and Acute Renal Failure, personal fees from Baxter, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, outside the submitted work. Dr. Mehta reports other from Astute Medical Inc., other from Baxter, grants from Fresenius, grants from Fresenius-Kabi, grants from Grifols, grants from Relypsa, other from Mallinckrodt, other from CSL Behring, other from Sphingotec, other from Regulus, other from Intercept, other from Quark, other from AM-Pharma, outside the submitted work. Dr. Nadim reports personal fees from Baxter, outside the submitted work. Dr. Palevsky reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from GE Healthcare, personal fees from Baxter, personal fees from Durect, personal fees from HealthSpan Dc, grants from Dascena, outside the submitted work. Dr. Rewa reports personal fees from Baxter Healthcare Inc, outside the submitted work. Dr. Rosner reports other from American Society of Nephrology, other from Retrophin, other from Baxter, other from Reata Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. Dr. Zarbock reports grants from German Research Foundation, BMBF, Else-Kröner Fresenius Stiftung, GIF, Astute Medical, Astellas, personal fees from Astellas, Astute Medical, Fresenius, Braun, bioMerieux, Baxter, Ratiopharm, Amomed, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Ding, Dr. Juncos, Dr. Kane-Gill, Dr. Kashani, Dr. Lewington, Dr. Macedo, Ms. Mottes, O'Donoghue, Dr. Ostermann, Dr. Pickkers, Dr. Ronco, Dr. Siew, Dr. Silver, Dr. Tolwani, Dr. Wilson, and Dr. Wu have nothing to disclose.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01250119/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Definitions.

Supplemental Table 2. Care needed for AKI prevention and management.

Supplemental Table 3. Example quality improvement initiatives for diagnostic evaluation of AKI.

Supplemental Table 4. Example quality initiations to avoid the progression and duration of AKI.

Supplemental Table 5. Examples of monitoring, management, and documentation of AKI complications.

Supplemental Figure 1. Risk dimensions and risk factors.

Supplemental Figure 2. Quality measures of care for AKI primary prevention.

Supplemental Figure 3. Control-run chart for finding outliers and the need for policy changes.

Supplemental Figure 4. Root-cause analysis.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Quality Improvement Frameworks.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Acute Disease Quality Initiative Consensus Conference Methodology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kashani, Dr. Rosner, and Dr. Haase served as organizers of the 22nd Acute Disease Quality Initiative consensus meeting and participated in the all group discussions and preparation of the draft and edition of this manuscript. All other authors actively participated in the group and plenary conversations and attributed to this script.

The 22nd Acute Disease Quality Initiative consensus meeting received unrestricted grants from Baxter International Inc., La Jolla Pharmaceutical Company, Astute Medical Inc., MediBeacon Inc., AM-Pharma B.V., and AbbVie Inc. Dr. Bihorac reports grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), during the conduct of the study. Dr. Liu reports grants from NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK). Dr. Silver received a new investigator award funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Kidney Foundation of Canada, and the Canadian Society of Nephrology Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training Program. Dr. Wilson reports grants from NIDDK, during the conduct of the study.

Corporate sponsors were allowed to attend all meeting sessions as observers but were not allowed to participate in the consensus process. Corporate sponsors had no input into the preparation of final recommendations or this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cely CM, Colman R, Cruz DN, Edipidis K, Forni LG, Gomersall CD, Govil D, Honoré PM, Joannes-Boyau O, Joannidis M, Korhonen AM, Lavrentieva A, Mehta RL, Palevsky P, Roessler E, Ronco C, Uchino S, Vazquez JA, Vidal Andrade E, Webb S, Kellum JA: Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: The multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med 41: 1411–1423, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silver SA, Long J, Zheng Y, Chertow GM: Cost of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med 12: 70–76, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riffaut N, Moranne O, Hertig A, Hannedouche T, Couchoud C: Outcomes of acute kidney injury depend on initial clinical features: A national French cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 2218–2227, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meersch M, Schmidt C, Hoffmeier A, Van Aken H, Wempe C, Gerss J, Zarbock A: Prevention of cardiac surgery-associated AKI by implementing the KDIGO guidelines in high risk patients identified by biomarkers: The PrevAKI randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med 43: 1551–1561, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Göcze I, Jauch D, Götz M, Kennedy P, Jung B, Zeman F, Gnewuch C, Graf BM, Gnann W, Banas B, Bein T, Schlitt HJ, Bergler T: Biomarker-guided intervention to prevent acute kidney injury after major surgery: The prospective randomized BigpAK study. Ann Surg 267: 1013–1020, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selby NM, Casula A, Lamming L, Stoves J, Samarasinghe Y, Lewington AJ, Roberts R, Shah N, Johnson M, Jackson N, Jones C, Lenguerrand E, McDonach E, Fluck RJ, Mohammed MA, Caskey FJ: An organizational-level program of intervention for AKI: A pragmatic stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 505–515, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Stewart J, Findlay G, Smith N, Kelly K, Mason M: Acute Kidney Injury: Adding Insult To Injury, London, National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2009. Available at: https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2009aki.html. Accessed April 9, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srisawat N, Sileanu FE, Murugan R, Bellomod R, Calzavacca P, Cartin-Ceba R, Cruz D, Finn J, Hoste EE, Kashani K, Ronco C, Webb S, Kellum JA; Acute Kidney Injury-6 Study Group: Variation in risk and mortality of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: A multicenter study. Am J Nephrol 41: 81–88, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James MT, Pannu N: Can acute kidney injury be considered a clinical quality measure. Nephron 131: 237–241, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donabedian A: Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q 44[Suppl]: 166–206, 1966 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rewa OG, Villeneuve PM, Lachance P, Eurich DT, Stelfox HT, Gibney RTN, Hartling L, Featherstone R, Bagshaw SM: Quality indicators of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) care in critically ill patients: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med 43: 750–763, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Quality Improvement Goals for Acute Kidney Injury; ADQI XXII. Acute disease quality initiative (ADQI), 2019. Available at: http://www.adqi.org/Home-Call.htm. Accessed April 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha V, Parameswaran S: Community-acquired acute kidney injury in tropical countries. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 278–290, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawhney S, Fluck N, Fraser SD, Marks A, Prescott GJ, Roderick PJ, Black C: KDIGO-based acute kidney injury criteria operate differently in hospitals and the community-findings from a large population cohort. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 922–929, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kashani K, Macedo E, Burdmann EA, Hooi LS, Khullar D, Bagga A, Chakravarthi R, Mehta R: Acute kidney injury risk assessment: Differences and similarities between resource-limited and resource-rich countries. Kidney Int Rep 2: 519–529, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapi F, Azoulay L, Yin H, Nessim SJ, Suissa S: Concurrent use of diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: Nested case-control study. BMJ 346: e8525, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dreischulte T, Morales DR, Bell S, Guthrie B: Combined use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with diuretics and/or renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in the community increases the risk of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 88: 396–403, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell AM, Jones AE, Tumlin JA, Kline JA: Incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy after contrast-enhanced computed tomography in the outpatient setting. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 4–9, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emmett L, Tollitt J, McCorkindale S, Sinha S, Poulikakos D: The evidence of acute kidney injury in the community and for primary care interventions. Nephron 136: 202–210, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duceppe E, Parlow J, MacDonald P, Lyons K, McMullen M, Srinathan S, Graham M, Tandon V, Styles K, Bessissow A, Sessler DI, Bryson G, Devereaux PJ: Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines on perioperative cardiac risk assessment and management for patients who undergo noncardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol 33: 17–32, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silver SA, McQuillan R, Harel Z, Weizman AV, Thomas A, Nesrallah G, Bell CM, Chan CT, Chertow GM: How to sustain change and support continuous quality improvement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 916–924, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta RL, Burdmann EA, Cerdá J, Feehally J, Finkelstein F, García-García G, Godin M, Jha V, Lameire NH, Levin NW, Lewington A, Lombardi R, Macedo E, Rocco M, Aronoff-Spencer E, Tonelli M, Zhang J, Remuzzi G: Recognition and management of acute kidney injury in the International Society of Nephrology 0by25 Global napshot: A multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet 387: 2017–2025, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes SL, Mann MK, Morgan FM, Kelly MJ, Weightman AL: Collaboration between local health and local government agencies for health improvement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10: CD007825, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra R, Kashani KB, Macedo E, Kim J, Bouchard J, Wynn S, Li G, Ohno-Machado L, Mehta R: A risk prediction score for acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 814–822, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koyner JL, Carey KA, Edelson DP, Churpek MM: The development of a machine learning inpatient acute kidney injury prediction model. Crit Care Med 46: 1070–1077, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.KDIGO: Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2: 1–138, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Clinical Guideline Centre: Acute Kidney Injury: Prevention, Detection and Management Up to the Point of Renal Replacement Therapy, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance, London, Royal College of Physicians, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joannidis M, Druml W, Forni LG, Groeneveld ABJ, Honore PM, Hoste E, Ostermann M, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Schetz M: Prevention of acute kidney injury and protection of renal function in the intensive care unit: Update 2017: Expert opinion of the Working Group on Prevention, AKI section, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 43: 730–749, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore PK, Hsu RK, Liu KD: Management of acute kidney injury: Core curriculum 2018. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 136–148, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanagasundaram S: The NICE acute kidney injury guideline: Questions still unanswered. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 74: 664–665, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobson C, Ruchi R, Bihorac A: Perioperative acute kidney injury: Risk factors and predictive strategies. Crit Care Clin 33: 379–396, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ftouh S, Lewington A; Acute Kidney Injury Guideline Development Group convened by the National Clinical Guidelines Centre and commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, in association with The Royal College of Physicians’ Clini: Prevention, detection and management of acute kidney injury: Concise guideline. Clin Med (Lond) 14: 61–65, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hobson C, Lysak N, Huber M, Scali S, Bihorac A: Epidemiology, outcomes, and management of acute kidney injury in the vascular surgery patient. J Vasc Surg 68: 916–928, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostermann M, Joannidis M: Acute kidney injury 2016: Diagnosis and diagnostic workup. Crit Care 20: 299, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selby NM, Casula A, Lamming L, Mohammed M, Caskey F; Tackling AKI Investigators: Design and rationale of ‘tackling acute kidney injury’, a multicentre quality improvement study. Nephron 134: 200–204, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolhe NV, Reilly T, Leung J, Fluck RJ, Swinscoe KE, Selby NM, Taal MW: A simple care bundle for use in acute kidney injury: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 1846–1854, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebah L, Hanumapura P, Waring D, Challiner R, Hayden K, Alexander J, Henney R, Royston R, Butterworth C, Vincent M, Heatley S, Terriere G, Pearson R, Hutchison A: A multifaceted quality improvement programme to improve acute kidney injury care and outcomes in a large teaching hospital. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 6: u219176.w7476, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox ZL, McCoy AB, Matheny ME, Bhave G, Peterson NB, Siew ED, Lewis J, Danciu I, Bian A, Shintani A, Ikizler TA, Neal EB, Peterson JF: Adverse drug events during AKI and its recovery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1070–1078, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barreto EF, Mueller BA, Kane-Gill SL, Rule AD, Steckelberg JM: β-Lactams: The competing priorities of nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and stewardship. Ann Pharmacother 52: 1167–1168, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostermann M, Chawla LS, Forni LG, Kane-Gill SL, Kellum JA, Koyner J, Murray PT, Ronco C, Goldstein SL; ADQI 16 workgroup: Drug management in acute kidney disease - Report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative XVI meeting. Br J Clin Pharmacol 84: 396–403, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldstein SL, Mottes T, Simpson K, Barclay C, Muething S, Haslam DB, Kirkendall ES: A sustained quality improvement program reduces nephrotoxic medication-associated acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 90: 212–221, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schanz M, Wasser C, Allgaeuer S, Schricker S, Dippon J, Alscher MD, Kimmel M: Urinary [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7]-guided randomized controlled intervention trial to prevent acute kidney injury in the emergency department [published online ahead of print June 28, 2018]. Nephrol Dial Transplant 10.1093/ndt/gfy186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barreto EF, Rule AD, Voils SA, Kane-Gill SL: Innovative use of novel biomarkers to improve the safety of renally eliminated and nephrotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy 38: 794–803, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rewa O, Mottes T, Bagshaw SM: Quality measures for acute kidney injury and continuous renal replacement therapy. Curr Opin Crit Care 21: 490–499, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rewa OG, Eurich DT, Noel Gibney RT, Bagshaw SM: A modified Delphi process to identify, rank and prioritize quality indicators for continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) care in critically ill patients. J Crit Care 47: 145–152, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.United States Renal Data System: USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018, Available at: https://www.usrds.org/2018/view/v1_05.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karsanji DJ, Pannu N, Manns BJ, Hemmelgarn BR, Tan Z, Jindal K, Scott-Douglas N, James MT: Disparity between nephrologists’ opinions and contemporary practices for community follow-up after AKI hospitalization. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1753–1761, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.