Abstract

Low-grade albuminuria, determined by the urinary albumin to creatinine ratio, has been linked to systemic vascular dysfunction and is associated with cardiovascular mortality. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is related to mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2, pulmonary vascular dysfunction and is increasingly recognized as a systemic disease. In a total of 283 patients (two independent cohorts) diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, 18 unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and 68 healthy controls, spot urinary albumin to creatinine ratio and its relationship to demographic, functional, hemodynamic and outcome data were analyzed. Pulmonary arterial hypertension patients and unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers had significantly elevated urinary albumin to creatinine ratios compared with healthy controls (P < 0.01; P = 0.04). In pulmonary arterial hypertension patients, the urinary albumin to creatinine ratio was associated with older age, lower six-minute walking distance, elevated levels of C-reactive protein and hemoglobin A1c, but there was no correlation between the urinary albumin to creatinine ratio and hemodynamic variables. Pulmonary arterial hypertension patients with a urinary albumin to creatinine ratio above 10 µg/mg had significantly higher rates of poor outcome (P < 0.001). This study shows that low-grade albuminuria is prevalent in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients and is associated with poor outcome. This study shows that albuminuria in pulmonary arterial hypertension is associated with systemic inflammation and insulin resistance.

Keywords: pulmonary hypertension, albuminuria, BMPR2, outcome

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a devastating condition characterized by increased blood pressure in the pulmonary circulation caused by diseased peripheral pulmonary blood vessels.1 Pulmonary vascular homeostasis can be disrupted due to loss of function mutations in the gene bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2) that are found in more than 75% of familial PAH and in approximately 20% of sporadic cases of idiopathic PAH.2 PAH is increasingly recognized as a systemic illness with abnormalities in immune cells,3 the myocardium,4 skeletal muscle,5 and whole body insulin/glucose balance6 and alterations were found in extra-pulmonary circulatory systems, including brachial, cerebral,7 sublingual,8 and bronchial arteries.9 Recognizing PAH as a systemic cardiovascular disease may have important diagnostic and treatment implications.

Albuminuria has long been recognized as an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease and outcome in individuals with and without cardiovascular co-morbidities.10–13 Notably, it has been shown that urinary albumin excretion is proportional to systemic transvascular albumin leakiness.14 Therefore, it has been proposed that albuminuria reflects an underlying systemic manifestation of vascular dysfunction.15

Albuminuria is currently defined as microalbuminuria (a ratio of albumin (µg/L) to creatinine (mg/L) between 30 and 300), or macroalbuminuria (a ratio of albumin (µg/L) to creatinine (mg/L) above 300 mg).16

The term low-grade albuminuria accounts for the fact that there seems to be a relationship between an albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) below 30 µg/mg of creatinine (microalbuminuria) and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.17,18

While growing evidence supports the presence of systemic vascular dysfunction in PAH and a potential relationship with disease severity, non-invasive measures to assess vascular dysfunction are lacking. Similarly, non-invasive assessments of BMPR2 mutation carriers with PAH risk but without clinically manifest disease are needed and could identify subjects at enhanced PAH risk.

This study aimed to investigate albuminuria as a potential systemic manifestation of vascular dysfunction in patients with PAH. We therefore studied the prevalence and associations of albuminuria with hemodynamics, functional and biochemical variables and outcome. In addition, albuminuria was assessed in a cohort of unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers to investigate a potential link of albuminuria and BMPR2 dysfunction.

Methods

Study population

For this study, two independent cohorts of PAH patients were recruited from Vanderbilt University and Stanford Hospital and Clinics. The Vanderbilt University and Stanford Hospital and Clinics institutional review boards (IRBs) approved this study, and all subjects gave written informed consent (Vanderbilt University IRB numbers 9401 and 111530; Stanford Hospital and Clinics IRB number 14083).

All patients were referred to Vanderbilt University or Stanford Hospital and Clinics between 2008 and 2016. All patients consented to provide a fasting morning urine sample.

The diagnosis of PAH was made either by autopsy results showing plexogenic pulmonary arteriopathy in the absence of alternative causes, such as congenital heart disease, or by clinical and cardiac catheterization criteria. These criteria included a mean pulmonary arterial pressure greater than 25 mmHg with a pulmonary capillary or left atrial pressure less than 15 mmHg, and exclusion of other causes of pulmonary hypertension, in accordance with accepted international standards of diagnostic criteria.19

The unaffected BMPR2 mutation carrier cohort consisted of 18 unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers, each of whom was a relative of a PAH patient(s) with a known BMPR2 mutation detected using multiple screening technologies, including standard sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification techniques as previously described.20 BMPR2 mutation carrier status was confirmed in the laboratory for all unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers as previously described.21 All subjects designated as unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers were seen by a physician within one year of sample acquisition, and without symptoms or signs of PAH.

Healthy controls were individuals over 18 years of age, recruited from the community by the Vanderbilt University subsite of the Researchmatch.org program. Individuals had no past medical history, were on no medications and were apparently healthy.

Exclusion criteria for all groups were: macroalbuminuria (ACR >300 µg/mg), a glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation), a diagnosis of renal disease, hyponatremia (serum sodium <135), a spot urinary creatinine concentration higher than 200 mg/ml, diabetes mellitus or pre-diabetes (defined as a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) >6.5% or two random blood glucose levels >200 mg/dl or by treatment with oral anti-diabetic drugs or insulin), systemic hypertension (as defined by a systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure great than or equal to 90 mmHg22 or treatment with anti-hypertensives) and obesity (as defined by a body mass index greater than or equal to 30).

Urine studies

At the time of acquisition, all urine samples were immediately cooled at 4℃ for 24 hours and then centrifuged at 4℃. Urine samples were aliquoted and frozen at –80℃ for later analysis. The urinary ACR was determined as the ratio between albumin and urinary creatinine in µg/mg. The albumin concentration was determined using a turbidimetric immunoassay with end point determination, and urinary creatinine was determined using a kinetic alkaline picrate assay. All urine assays were performed by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Pathology Laboratory Services.

Hemodynamic, functional and biochemical data

Hemodynamics, functional and biochemical data were obtained by chart review.

All values used for this study were within a three-month range from the obtained urine sample used for ACR analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as absolute numbers, percentages, mean (±SD) and or median with interquartile range. In all parametric tests, preliminary analyses were performed to ensure no violation of the assumption of normality, linearity and homoscedasticity. Differences between baseline variables in PAH patients were assessed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (with Dunn’s multiple comparison) was performed to assess differences between PAH, PAH subgroups, unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and healthy control subjects. ACR according to PAH, unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and control subjects were shown as scatter plots with mean ± SD. The relations between ACR and baseline variables were assessed by Spearman correlation coefficients.

Differences between baseline variables in PAH patients with a ACR below and above 10 µg/mg (the median of the first cohort) were assessed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables.

Months at risk were calculated from acquisition of the urine sample until study end (31 July 2016 for the first cohort and 31 October 2017 for the second cohort). The primary outcome was defined a priori as death or lung transplantation. Estimated event-free survival was calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis for patients with a ACR above or below 10 µg/ml. Statistical differences between both groups were assessed using log rank testing. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Figures were prepared using the GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of both cohorts, unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and controls

The first cohort consisted of 132 patients (75% women) with 28% (37) heritable PAH, 40% (53) idiopathic PAH, 24% (31) PAH associated with connective tissue disease (CTD-PAH), and 6% (8) PAH associated with congenital heart disease (CHD-PAH). The mean age of the PAH patients was 57 years; median follow-up was 33 months. There were 23 events of death (n = 21) or lung transplantation (n = 2).

Eight patients were excluded based on an elevated ACR (macroalbuminuria). The second cohort consisted of 151 patients (80% women) with 1.3% (2) heritable PAH, 24% (37) idiopathic PAH, 43% (65) CTD-PAH and 10% (15%) CHD-PAH. The mean age of this cohort was 51 years; median follow-up was 37 months. There were 25 events of death (n = 19) or lung transplantation (n = 6). The pooled cohort consisted of 283 patients with PAH (78% women) with 13.7% (39) heritable PAH, 31.8% (90) idiopathic PAH, 33.9% (96) CTD-PAH and 8.1% (23) CTD-PAH. The mean age of the pooled cohort was 51 years; mean follow-up was 37 months. There were 48 events of death (n = 40) or lung transplantation (n = 8). Twelve patients in this cohort were excluded based on an elevated ACR (macroalbuminuria).

The unaffected BMPR2 mutation carrier group consisted of 18 unaffected carriers with a confirmed mutation in BMPR2. This group had 72% women, and a mean age of 51 years. The healthy control group contained 69 healthy individuals of mean age 49 years (61% women). No individual in the unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers or healthy control cohort carried a diagnosis of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia or kidney disease nor was on chronic medications. There was no significant difference in age or sex between PAH cohorts, unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, first cohort.

| All patients (n = 283) | First cohort (n = 132) | Second cohort (n = 151) | P valuea | Unaffected mutation carriers (n = 18) | Controls (n = 68) | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54 (14.8) | 57 (14.7) | 51 (14.6) | 0.119 | 51 (13.6) | 49 (14) | 0.122 |

| Women (%) | 78 | 75 | 80 | 0.811 | 72 | 61 | 0.095c |

| NYHA | 0.345 | ||||||

| I | 20 | 2 | 18 | ||||

| II | 104 | 38 | 66 | ||||

| III | 124 | 63 | 61 | ||||

| IV | 35 | 29 | 6 | ||||

| 6MWD (m) | 383 (147) | 345 (121) | 402 (130) | 0.602 | |||

| mRAP (mmHg) | 8.2 (5) | 9.0 (6.2) | 8.6 (4.5) | 0.154 | |||

| mPAP (mmHg) | 48 (16.4) | 54 (17.2) | 46 (14.9) | 0.211 | |||

| SBP (mmHg) | 118 (16) | 121 (20) | 117 (12.7) | 0.865 | |||

| mPCWP (mmHg) | 9.6 (3.3) | 9.3 (3.3) | 9.8 (4.1) | 0.440 | |||

| CI (l/min/m2) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.2 (0.7) | 0.733 | |||

| SCr (mg/dl) | 0.67 (0.5) | 0.97 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.319 | |||

| CRP (mg/l) | 5.8 (7.2) | 7.9 (8.7) | 4.5 (6) | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | 5.4 (0.8) | 5.7 (0.6) | 5.3 (1) | ||||

| ACR (µg/mg) | 22.2 (33) | 17.8 (22) | 26.0 (39) | 0.743 | 10.6 (4.8) | 4.3 (3.0) | 0.003 |

Data are shown as percentage or mean (SD).

aMann–Whitney U-test first versus second cohort.

bOne-way analysis of variance, all patients versus unaffected mutation carriers and controls.

cChi-square test, all patients versus unaffected mutation carriers and controls.

NYHA: New York Heart Association functional class; 6MWD: 6-minute walk distance; mRAP: mean right atrial pressure; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; SBP: systolic systemic blood pressure; mPCWP: mean pulmonary wedge pressure; CI: cardiac index; SCr: serum creatinine; CRP: C-reactive protein; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; ACR: albumin to creatinine ratio.

ACR in PAH, unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and controls

Mean urinary ACR in the first and second cohort were 17.8 µg/mg (22) and 26.0 µg/mg (39), respectively. Twenty-one patients (15.9%) in the first cohort and 36 (23.8%) in the second cohort had microalbuminuria (ACR > 30 µg/mg). Mean urinary ACR in the pooled cohort was 22.2 µg/mg (33) and 57 (20.1%) had microalbuminuria. Mean urinary ACR was 10.6 µg/mg (4.8) in the unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and 4.3 µg/mg (3.0) in the healthy controls. There was no statistically significant difference in the urinary ACR between both PAH cohorts (P = 0.743) nor between the PAH cohorts or unaffected mutation carriers (P = 0.283, Fig. 1). Urinary ACR was statistically significantly different between both PAH cohorts and unaffected mutation carriers when compared to healthy controls (P < 0.001 and P = 0.04; Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in urinary ACR among the different etiologies of PAH patients (P = 0.190 one-way ANOVA, Supplementary Fig. 1 data not shown). In the pooled cohort, 57 PAH patients (20%) had microalbuminuria (ACR >30 µg/mg).

Fig. 1.

Urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) levels according to the two pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) cohorts, unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers and healthy controls. Dot plot of ACR values in all patients, cohort 1, cohort 2, unaffected mutation carriers and controls. Data are shown as individual values, lines represent median with interquartile range. * Indicates P < 0.05 in Dunn’s multiple comparison all patients versus controls and #indicates P < 0.05 in Dunn’s multiple comparison unaffected mutation carriers versus controls, obtained by non-parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing all patients, unaffected mutation carriers and Normal Controls.

ACR in PAH and other variables

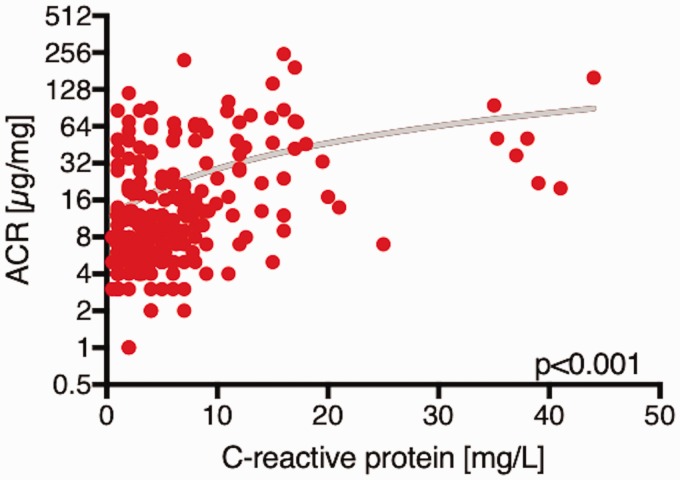

In the pooled cohort, there were significant positive correlations between urinary ACR and C-reactive protein (CRP) (r = 0.44, P < 0.001, Fig. 2), age (r = 0.21, P = 0.001) and HbA1c (r = 0.21, P < 0.001) and a negative correlation with six-minute walking distance (r = –0.26, P < 0.001). In both cohorts, there was no significant association between urinary ACR, hemodynamic parameters or serum creatinine (Table 2). In both cohorts, patients with an elevated urinary ACR above the median of the first cohort (>10 µg/mg) were older (P = 0.008; 0.002), had higher CRP (P < 0.001, respectively) and higher HbA1c levels (P < 0.001, respectively). In both cohorts, there was no significant difference in hemodynamic parameters between patient with a urinary ACR above or below 10 µg/mg (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Relationship of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels to urine albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) in all patients. Scatter plot showing the relation of CRP levels and ACR in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients.

Table 2.

Correlation of urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) with clinical, biochemical and hemodynamic markers.

| ACR |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients |

Cohort 1 |

Cohort 2 |

||||

| Spearman’s rho | P value | Spearman’s rho | P value | Spearman’s rho | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.210 | <0.001 | 0.153 | 0.077 | 0.31 | 0.001 |

| Women (%) | 0.29 | 0.623 | 0.453 | 0.328 | 0.08 | 0.311 |

| NYHA | 0.093 | 0.176 | 0.069 | 0.431 | 0.181 | 0.026 |

| 6MWD (m) | –0.262 | <0.001 | –0.248 | 0.093 | –0.348 | 0.001 |

| mRAP (mmHg) | 0.093 | 0.157 | 0.184 | 0.076 | 0.14 | 0.131 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | –0.018 | 0.793 | –0.040 | 0.702 | 0.19 | 0.121 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.050 | 0.512 | 0.04 | 0.673 | 0.07 | 0.721 |

| mPCWP (mmHg) | 0.035 | 0.157 | 0.10 | 0.325 | 0.21 | 0.225 |

| CI (l/min/m2) | 0.048 | 0.586 | 0.06 | 0.621 | –0.41 | 0.654 |

| SCr (mg/dl) | 0.038 | 0.746 | 0.038 | 0.746 | 0.013 | 0.954 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 0.435 | <0.001 | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 0.210 | <0.001 | 0.312 | 0.002 | 0.363 | 0.033 |

Baseline ACR were correlated with demographic, clinical, hemodynamic and biochemical markers using Spearman’s rank correlation.

NYHA: New York Heart Association functional class; 6MWD: 6-minute walk distance; mRAP: mean right atrial pressure; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; SBP: systolic systemic blood pressure; mPCWP: mean pulmonary wedge pressure; CI: cardiac index; SCr: serum creatinine; CRP: C-reactive protein; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c.

Table 3.

Characteristics of pulmonary arterial hypertension patients with urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) below and above 10 µg/mg.

| All patients |

Cohort 1 |

Cohort 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR < 10 | ACR > 10 | P value | ACR < 10 | ACR > 10 | P value | ACR < 10 | ACR > 10 | P value | |

| Age (years) | 51 (13) | 56 (15) | 0.003 | 53 (14.4) | 59 (14.1) | 0.008 | 52 (14) | 57 (16) | 0.002 |

| Women (%) | 76 | 82 | 0.534 | 76 | 82 | 0.534 | 73 | 84 | 0.566 |

| NYHA | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.8) | 0.432 | 2.8 (0.7) | 3 (0.8) | 0.321 | 2 (0.8) | 3 (0.7) | 0.423 |

| 6MWD (m) | 408 (147) | 356 (144) | 0.067 | 379 (103) | 331 (126) | 0.081 | 448 (152) | 356 (134) | 0.067 |

| mRAP (mmHg) | 8.0 (5) | 8.3 (5) | 0.749 | 8.0 (5) | 9.8 (7) | 0.173 | 8.4 (4.1) | 9.2 (5.1) | 0.155 |

| mPAP (mmHg) | 49 (16) | 48 (17) | 0.533 | 55 (18.0) | 52 (15.9) | 0.054 | 43 (13) | 44 (15) | 0.765 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 116 (15) | 120 (18) | 0.214 | 121 (14) | 125 (26) | 0.138 | 119 (18) | 123 (18) | 0.341 |

| mPCWP (mmHg) | 9.7 (3.4) | 9.5 (3.2) | 0.704 | 8.9 (3.2) | 9.5 (3.6) | 0.504 | 11 (4) | 12 (3) | 0.413 |

| CI (l/min/m2) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.8) | 0.146 | 2.0 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.9) | 0.105 | 2.1 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.7) | 0.284 |

| SCr (mg/dl) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.405 | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.623 | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.791 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 3.1 (3.5) | 8.2 (9.3) | <0.001 | 4.0 (2.5) | 12.3 (10.8) | <0.001 | 4 (2.5) | 7.1 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.3 (0.6) | 5.5 (3) | 0.005 | 5.6 (0.4) | 5.9 (0.8) | 0.005 | 5.0 (0.6) | 5.5 (1.2) | 0.023 |

| ACR (µg/mg) | 6.1 (2.2) | 39.9 (41) | <0.001 | 5.7 (1.9) | 37.9 (57) | <0.001 | 6.0 (2.1) | 52 (56) | <0.001 |

Data are shown as percentage or mean (SD) or percentage.

P values were calculated by Spearman rank correlation for continuous variables, chi-square test for nominal variables, and t test for NYHA class.: 6-minute walk distance; mRAP: mean right atrial pressure; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; SBP:systolic systemic blood pressure; mPCWP: mean pulmonary wedge pressure; CI: cardiac index; SCr: serum creatinine; CRP: C-reactive protein; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c.

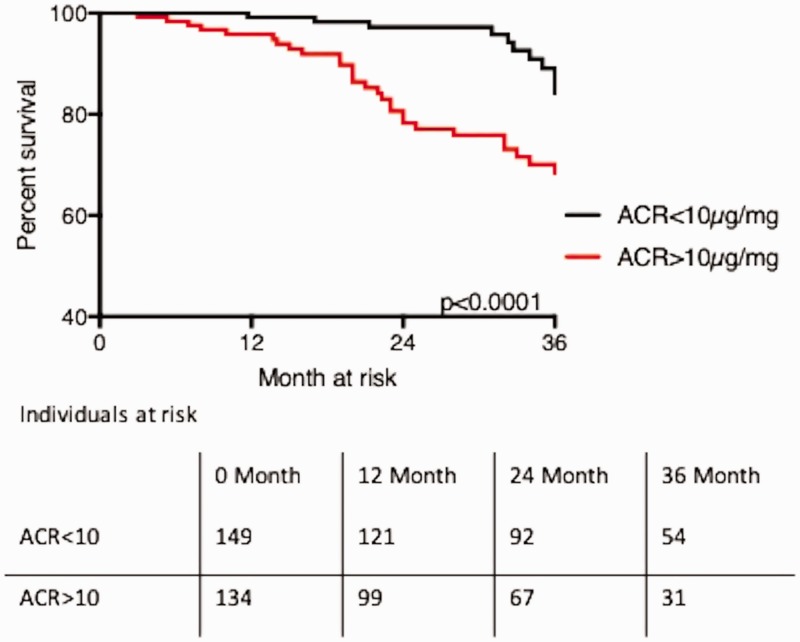

ACR and outcome in PAH

In both cohorts, patients with an elevated urinary ACR (>10 µg/mg, the median of the first PAH cohort) had a statistically higher chance of reaching the primary endpoint of death or lung transplantation. In the first cohort, estimated survival was 53 months (49–56) in patients with a urinary ACR less than 10 µg/mg, versus 46 (41–51) months in patients with a ACR greater than 10 µg/mg (P = 0.001). In the second cohort, estimated survival was 58 months (46–64) in patients with a urinary ACR less than 10 µg/mg, versus 70 months (62–79) in patients with a ACR greater than 10 µg/mg (P = 0.001). Estimated survival in the pooled cohort of patients with a urinary ACR less than 10 µg/mg was 53 months (44–62), versus 68 months (60–75) in patients with a urinary ACR greater than 10 µg/mg (P < 0.001; Table 4, Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 3(a and b)).

Table 4.

Estimated event-free survival according to urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR).

| n | Events | Estimated survival (months) | Mean 95% CI (months) | Log rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | ACR < 10 µg/mg | 149 | 12 | 68 | 60–75 | <0.001 |

| ACR > 10 µg/mg | 134 | 36 | 53 | 44–62 | ||

| Cohort 1 | ACR < 10 µg/mg | 69 | 3 | 53.1 | 49–56 | 0.002 |

| ACR > 10 µg/mg | 63 | 20 | 45.7 | 40–51 | ||

| Cohort 2 | ACR < 10 µg/mg | 80 | 9 | 70.1 | 62–79 | 0.016 |

| ACR > 10 µg/mg | 71 | 16 | 57.7 | 46–64 |

Percentage mean estimated event-free survival (death or transplantation) according to ACR below and above 10 µg/mg.

The difference between the curves was calculated using log-rank testing.

Percentage estimated event-free survival (death or transplantation) according to ACR below and above 10 µg/mg.

The difference between the curves was calculated using log-rank testing.

CI: confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves of 36-month survival estimates according to the urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) below and above 10 µg/mg in all patients. Statistical analysis performed with log rank testing.

In a subgroup analysis, excluding patients with microalbuminuria (ACR >30 µg/mg), estimated survival for patients with a urinary ACR below 10 µg/mg was 68 months (60–76), versus 55 months (45–66) (P = 0.002; Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3(c)).

Discussion

This study has four main findings: (a) In two independent cohorts of PAH patients, low-grade albuminuria, below the currently defined microalbuminuria threshold of 30 µg/mg, was associated with poor clinical outcome. (b) Traditional risk factors for albuminuria, such as systemic hypertension and diabetes were not present in this study population, suggesting other non-classic contributors to albuminuria, such as systemic inflammation and insulin resistance. (c) Low-grade albuminuria was not associated with right heart hemodynamics, suggesting a pathophysiology beyond cardiorenal syndrome. (d) Individuals without evident PAH but with somatic mutations in the BMPR2 gene had higher urinary albumin excretion, when compared to healthy controls, suggesting a contribution of abnormal BMPR2 signaling to low-grade albuminuria.

Low-grade albuminuria is an emerging biomarker for the development and progression of systemic cardiovascular diseases,23,24 even in patients without diabetes and hypertension, major drivers of albuminuria.25 Similarly, we found in two independent PAH cohorts, that a urinary ACR above 10 µg/mg was associated with an increased risk of poor outcome (Table 4, Fig. 3). These results were not driven by the small proportion of patients with microalbuminuria (20% in the pooled cohort, Supplementary Fig. 3(c)), underscoring the notion that albumin excretion far below the current defined threshold of microalbuminuria has important clinical implications in cardiovascular diseases.

While this study was not designed to detect the precise mechanism(s) of albuminuria in PAH, several are possible. Diastolic dysfunction and venous congestion in left heart failure have been associated with altered glomerular hemodynamics and permeability and can contribute to increased albuminuria.26,27 However, albuminuria in left heart failure was not associated with ejection fraction, heart failure etiology or duration, symptomatic severity or neurohormonal activation, suggesting that pathophysiological mechanisms beyond the cardiorenal syndrome can contribute to albuminuria.28,29 In line with that, the lack of an association of albuminuria with right heart hemodynamics in both PAH cohorts suggests that elevated urinary albumin levels might reflect an important pathophysiological process that is not solely attributed to right heart failure and venous congestion. Interestingly, increased albuminuria in left heart failure was linked to elevated HbA1c.30 We found a weak but significant correlation between urinary albumin excretion and HbA1c levels in both PAH cohort that excluded patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes. In line with that, previous studies of non-diabetes subjects without systemic hypertension demonstrated a direct correlation between the degree of insulin resistance and the degree of albuminuria.31 Intriguingly, there is growing evidence for a link between insulin resistance and the pathogenesis of PAH.32

Systemic inflammation has been linked to urinary albumin and is known to be present in PAH patients.33 In fact, we found a correlation between urinary ACR and serum levels of CRP in two independent PAH cohorts. Increasing levels of CRP were associated with an increased risk of microalbuminuria in the general population and individuals with hypertension.33,34 Elevated CRP is an independent risk factor for poor outcome in patients with PAH, and it was suggested that CRP itself might contribute to vascular remodeling and systemic vascular dysfunction in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.35,36

A growing body of literature supports the hypothesis that PAH patients have a systemic vascular defect. Increased levels of von Willebrand factor (vWF), as a marker of systemic endothelial cell injury, have been shown to be associated with the development of albuminuria and were also linked to disease progression in PAH.37,38 The finding that unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers had elevated urinary albumin excretion compared to healthy aged-matched controls suggests a link between renal albumin handling and BMPR2 dysfunction. It is possible that low-grade albuminuria in unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers is a marker of pre-clinical disease, and an increase in albuminuria from baseline might predict progression to PAH. Therefore, serial measurements of urinary ACR in unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers or individuals with a family history of PAH could give important insights about the risk of disease development and more importantly might indicate the need for early initiation of treatment.

The molecular mechanism(s) by which albuminuria is mediated in PAH, and among unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers, remains speculative and is beyond the scope of this study. However, several potential causes exist, for individuals with overt pulmonary vascular disease. The selective proteinuria (albuminuria) in the early stages of patients with type 1 diabetes is suggestive of an abnormality in the charge selectivity of the glomerular barrier and was linked to systemic loss of glycosaminoglycans and heparin sulfates (HSs).39 Even though the role of glycosaminoglycans and HSs in ligand mediated receptor signaling remains controversial,40,41 there is evidence that HSs enhances BMPR2 recruitment and downstream signaling.42 It is possible that a systemic reduction of HSs in PAH is responsible for impaired pulmonary BMPR2 signaling and low-grade albuminuria.

BMPR2 signaling was shown to have impact on multiple pathways that are important for vascular homeostasis, such as the expression of collagen 4, ephrin A1, endothelial nitric oxide,43 caveolin-1,44 and others. Therefore, impaired systemic BMPR2 signaling could affect the perfusion and protein handling of renal glomerulus, leading to albuminuria.

Limitations

While two fairly large independent cohorts of PAH patients are presented, this study is limited by sample size with regard to the unaffected BMPR2 mutation carrier cohort. Although screened by interview and recent medical records review, unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers were not screened with echocardiography for the absence of PAH. While a limitation, we believe that the determination of PAH absence among the unaffected BMPR2 mutation carrier group is mitigated by the low penetrance rate of PAH (∼20%) across the lifetime of unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers, making it unlikely that an individual would have echocardiographic evidence of PAH at any one moment in time.45 In addition, we acknowledge that prospective replication of the findings in the unaffected mutation carriers cohort presented in a subsequent study will strengthen the confidence in the findings present. Going forward, it would be valuable to study a cohort of unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers longitudinally to assess for phenotypic conversion to PAH status regarding the level of urinary albumin.

Conclusions

Low-grade albuminuria is prevalent in patients with PAH and unaffected BMPR2 mutation carriers. We did not find direct evidence of an association of albuminuria with right heart hemodynamics, but with systemic inflammation and insulin resistance. More research is needed to understand better the mechanistic link of albuminuria in PAH. However, given the non-invasive nature of urine albumin measurement, ACR might serve as a useful screening tool for family members of patients with PAH.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Low-grade albuminuria in pulmonary arterial hypertension by Nils P. Nickel, Vinicio A. de Jesus Perez, Roham T. Zamanian, Joshua P. Fessel, Joy D. Cogan, Rizwam Hamid, James D. West, Mark P. de Caestecker, Haichun Yang and Eric D. Austin in Pulmonary Circulation

Acknowledgements

NPN designed the study, and takes responsibility for the data and data analysis integrity. VAJP designed the study and wrote the manuscript. JPF designed the study and wrote the manuscript. JDC helped with sample recruitment and processing and wrote the manuscript. RH designed the study and wrote the manuscript. JDW designed the study and wrote the manuscript. MPC designed the study and wrote the manuscript. HY designed the study and wrote the manuscript. RTZ helped with sample recruitment and study design. EDA designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Archer SL, Weir EK, Wilkins MR. Basic science of pulmonary arterial hypertension for clinicians: new concepts and experimental therapies. Circulation 2010; 121: 2045–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soubrier F, et al. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: D13–D21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinovitch M, Guignabert C, Humbert M, et al. Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res 2014; 115: 165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brittain EL, et al. Fatty acid metabolic defects and right ventricular lipotoxicity in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2016; 133: 1936–1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malenfant S, et al. Impaired skeletal muscle oxygenation and exercise tolerance in pulmonary hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015; 47: 2273–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutendra G, Michelakis ED. The metabolic basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cell Metabolism 2014; 9(4): 558–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malenfant S, et al. Compromised cerebrovascular regulation and cerebral oxygenation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dababneh L, Cikach F, Alkukhun L, et al. Sublingual microcirculation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11: 504–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghigna MR, et al. BMPR2 mutation status influences bronchial vascular changes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 1668–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerstein HC, et al. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA 2001; 286: 421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen JS, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Strandgaard S, et al. Arterial hypertension, microalbuminuria, and risk of ischemic heart disease. Hypertension 2000; 35: 898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager A, et al. Microalbuminuria and peripheral arterial disease are independent predictors of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, especially among hypertensive subjects: five-year follow-up of the Hoorn Study. Arterioscler, Thromb Vasc Biol 1999; 19: 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillege HL, et al. Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation 2002; 106: 1777–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen JS, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen G, et al. Microalbuminuria reflects a generalized transvascular albumin leakiness in clinically healthy subjects. Clin Sci 1995; 88: 629–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deckert T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. Albuminuria reflects widespread vascular damage. The Steno hypothesis. Diabetologia 1989; 32: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson RG, Tuttle KR. NKF releases new KDOQI guidelines for diabetes and CKD. Nephrol News Issues 2006; 20: 29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnlov J, et al. Low-grade albuminuria and incidence of cardiovascular disease events in nonhypertensive and nondiabetic individuals: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2005; 112: 969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka F, et al. Low-grade albuminuria and incidence of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in nondiabetic and normotensive individuals. J Hypertens 2016; 34: 506–512; discussion 512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simonneau G, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: D34–D41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cogan JD, et al. High frequency of BMPR2 exonic deletions/duplications in familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 590–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogan JD, et al. Gross BMPR2 gene rearrangements constitute a new cause for primary pulmonary hypertension. Genet Med: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 2005; 7: 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James PA, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014; 311: 507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stehouwer CD, et al. Microalbuminuria is associated with impaired brachial artery, flow-mediated vasodilation in elderly individuals without and with diabetes: further evidence for a link between microalbuminuria and endothelial dysfunction – the Hoorn Study. Kidney Int Suppl 2004, pp. S42–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Cosmo S, et al. Increased urinary albumin excretion, insulin resistance, and related cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence of a sex-specific association. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 910–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mogensen CE. Systemic blood pressure and glomerular leakage with particular reference to diabetes and hypertension. J Intern Med 1994; 235: 297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz DH, et al. Association of low-grade albuminuria with adverse cardiac mechanics: findings from the hypertension genetic epidemiology network (HyperGEN) study. Circulation 2014; 129: 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masson S, et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of elevated urinary albumin excretion in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the GISSI-Heart Failure trial. Circ Heart Fail 2010; 3: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ataga KI, et al. Association of soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase-1 with pulmonary hypertension and haemolysis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2011; 152: 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van de Wal RM, et al. High prevalence of microalbuminuria in chronic heart failure patients. J Cardiac Fail 2005; 11: 602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson CE, et al. Albuminuria in chronic heart failure: prevalence and prognostic importance. Lancet 2009; 374: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilz S, et al. Insulin sensitivity and albuminuria: the RISC study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 1597–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamanian RT, et al. Insulin resistance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 318–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kshirsagar AV, et al. Association of C-reactive protein and microalbuminuria (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999 to 2004). Am J Cardiol 2008; 101: 401–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuveling EM, et al. C-reactive protein modifies the relationship between blood pressure and microalbuminuria. Hypertension 2004; 43: 791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quarck R, Nawrot T, Meyns B, et al. C-reactive protein: a new predictor of adverse outcome in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53: 1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wynants M, et al. Effects of C-reactive protein on human pulmonary vascular cells in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 886–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stehouwer CD, et al. Urinary albumin excretion, cardiovascular disease, and endothelial dysfunction in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1992; 340: 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawut SM, et al. von Willebrand factor independently predicts long-term survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2005; 128: 2355–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall SM. Diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: has the outlook improved since the 1980s? Diabetologia 2012; 55: 2301–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan SA, Nelson MS, Pan C, et al. Endogenous heparan sulfate and heparin modulate bone morphogenetic protein-4 signaling and activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2008; 294: C1387–C1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernfield M, et al. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem 1999; 68: 729–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuo WJ, Digman MA, Lander AD. Heparan sulfate acts as a bone morphogenetic protein coreceptor by facilitating ligand-induced receptor hetero-oligomerization. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21: 4028–4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhodes CJ, et al. RNA sequencing analysis detection of a novel pathway of endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192: 356–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Austin ED, et al. Whole exome sequencing to identify a novel gene (caveolin-1) associated with human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2012; 5: 336–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larkin EK, et al. Longitudinal analysis casts doubt on the presence of genetic anticipation in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 186: 892–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Low-grade albuminuria in pulmonary arterial hypertension by Nils P. Nickel, Vinicio A. de Jesus Perez, Roham T. Zamanian, Joshua P. Fessel, Joy D. Cogan, Rizwam Hamid, James D. West, Mark P. de Caestecker, Haichun Yang and Eric D. Austin in Pulmonary Circulation