Abstract

Background

Adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) frequently fail to achieve remission with an initial treatment. The sequential addition of psychotherapy after failure to remit with an antidepressant medication can target residual symptoms and protect against recurrence, but the utility of adding antidepressant medication after non-remission with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) has received little study.

Method

Previously untreated adults with MDD randomized to receive escitalopram, duloxetine, or CBT monotherapy who completed 12 weeks of treatment without achieving remission entered an additional 12 weeks of combination treatment. Non-remitters to CBT added escitalopram (CBT+MED group), and non-remitters to the antidepressants added CBT (MED+CBT group). Responders to combination treatment entered an 18-month follow-up phase to assess recurrence risk.

Results

One hundred twelve non-remitters entered combination treatment: 41 non-remitting responders, and 71 non-responders. Overall combination remission rates were significantly higher among previously non-remitting responders (61%) than among non-responders (41%). Among non-remitting responders to monotherapy, the remission rate in the CBT+MED group (89%) was higher than in the MED+CBT group (53%). However, among non-responders to monotherapy, rates of response and remission were similar between the treatment arms. Higher levels of anxiety, both prior to monotherapy and prior to beginning combination treatment, predicted poorer outcomes for both treatment groups.

Conclusion

The order in which CBT and antidepressant medication are sequentially combined does not appear to affect outcomes at the end of combination treatment. Addition of an antidepressant is an effective approach to treating the residual symptoms after non-remission to CBT, and vice versa. Patients who fail to respond to one monotherapy treatment modality warrant consideration for adding the alternative modality.

Keywords: Antidepressants, CBT, treatment resistance, anxiety, duloxetine, escitalopram, depression

Introduction

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and antidepressant medications are equally efficacious in the acute treatment of outpatients with major depressive disorder (MDD) (1). Unfortunately, non-remission is the rule for both treatments, with approximately 60-70% of patients completing acute treatment with significant ongoing symptoms. Because achieving remission is associated with better role functioning (2,3) and reduced risk of depressive episode relapse (4), treatment combinations are often implemented to achieve remission. Several studies have compared a single modality treatment (i.e., medication or psychotherapy) versus their combination from the initiation of treatment, finding small but significant effect sizes in favor of combination (5). However, cost and feasibility issues have led several authors to recommend a sequential combination treatment approach for most patients (6–9).

In the most common form of sequential combination treatment, a second treatment is added if a patient does not remit after an adequate trial with the initial intervention. Most sequential treatment studies have examined the efficacy of augmenting an initial antidepressant with a second psychopharmacological agent (10), with a smaller body of literature examining the addition of psychotherapy (8). Adding a course of evidence-based psychotherapy to antidepressant medication after non-remission improves depression scores and reduces[ the probability of recurrence over the subsequent 1-2 years (8,11). The protective effect of CBT against recurrence is particularly evident if the antidepressant medication is discontinued during maintenance treatment (12,13). A related, less-common, sequential treatment model involves adding a second treatment, usually psychotherapy, to prevent recurrence after remission with the initial treatment (8). Remarkably, although most depressed patients prefer psychotherapy (14) and leading treatment guidelines recommend an evidence-based psychotherapy as an initial intervention for all but the most severely ill patients (15,16), only one prior randomized trial has examined the value of adding antidepressant medication to psychotherapy, finding improved outcomes among 17 non-responders to psychodynamic psychotherapy (17). Thus, the evidence base is very limited regarding whether adding an antidepressant to CBT non-remitters improves acute outcomes and protects against depression recurrence.

Further, it is uncertain whether sequential combination treatments’ efficacy differ based on the order in which the psychotherapy and antidepressant medication treatments are conducted, and whether there are predictors for the efficacy of combination treatments. Although several clinical moderators of differential response to psychotherapy or antidepressants have been reported (18–21), replication of moderators across studies is rare and have seldom been examined for sequential combination treatments (22).

Herein we report the results of Phase II of the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) study. In Phase I, patients were randomly assigned to a 12-week course of CBT or antidepressant medication. Non-remitters to this monotherapy in Phase I were provided a second 12-week course of treatment, Phase II, in which the complementary treatment was added to their initial treatment. Demographic, clinical, and patient preference variables were examined as potential predictors and moderators of outcomes. Responders and remitters at the end of Phase II were eligible to enter an 18-month follow-up phase assessing relapse and recurrence. The outcomes from the follow-up phase and the impact of residual symptoms on relapse/recurrence were also explored.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board and the Grady Hospital Research Oversight Committee, and all patients provided written, informed consent prior to beginning study procedures. The design and results of the acute phase treatment of the PReDICT study have been previously published (23,24). Briefly, PReDICT enrolled 344 adults aged 18-65 years who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD without psychotic features. Key eligibility criteria included being treatment naïve, defined as never (lifetime) having received treatment for a mood disorder with either: (i) a marketed antidepressant at a minimum effective dose for ≥4 weeks; or (ii) ≥4 sessions of an evidence-based and structured psychotherapy for MDD (CBT, IPT or behavioral marital therapy). Key exclusion criteria included: a significant medical condition that could affect study participation or data interpretation; diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder, eating disorder, substance dependence, or dissociative disorder in the 12 months prior to screening; or substance abuse within the 3 months prior to baseline. A Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 17-item (HAM-D) (25) total score of ≥18 at screening and ≥15 at baseline were required for randomization.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 manner to 12 weeks of acute treatment with escitalopram (10-20 mg/day), duloxetine (30-60 mg/day), or 16 one-hour individual sessions of protocol-based CBT (26). Prior to randomization in Phase 1, patients indicated whether they would prefer to receive CBT, an antidepressant medication, or had no treatment preference. At Week 12, non-remitting patients (defined as a HAM-D total score >7 at either the week 10 or week 12 ratings visit) were offered the option of entering phase 2, a 12-week treatment period in which they received a combination of medication and CBT. In this second phase, patients who initially received escitalopram or duloxetine continued their medication and added 16 sessions of CBT. Patients who initially received CBT received 3 booster CBT sessions and 1 possible crisis session during the 12 weeks, and added escitalopram (10-20 mg/day). The study design did not include duloxetine as an add-on medication in Phase II due to the expectation of an insufficient number Phase I CBT non-remitters to power meaningful comparisons between the two medications. Assessments of depression (HAM-D) and anxiety (Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety, HAM-A) (27) severity were conducted at weeks 13-18, 20, 22, and 24.

Visits with the study physicians administering the pharmacotherapy were conducted in accord with the ‘Clinical Management Manual’ developed by Fawcett and colleagues (28). Other than general psychoeducation, physicians were prohibited from providing specific evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions, including those related to CBT. For the CBT therapists, competence of administration of the protocol-based CBT (26) was assessed by independent raters at the Beck Institute using the Cognitive Therapy Scale (29). On this measure, the rater assessed three of the therapists’ video-recorded sessions (session numbers 2, 8, and 12) on 11 components of CBT treatment, with each item rated 0-6. Total scores ≥40 reflect good therapist delivery of CBT. Any therapist whose rating for a session dropped below 40 received additional training and supervision at that time. Other psychotropic medications were prohibited throughout the study, with the exception of hypnotics, used up to three times per week, including eszopiclone, zaleplon, zolpidem, diphenhydramine, and melatonin, but excluding benzodiazepines

Non-responders at the end of Phase II ended their study participation and were referred for additional care. Responders and remitters at the end of Phase II (week 24) were eligible to enter an 18-month follow-up phase, during which assessments occurred every 3 months using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE) (30), HAM-D, and HAM-A. CBT booster sessions were offered during follow-up, with 3 per year, as well as one “crisis” session per year, if needed. Patients were encouraged to remain on their antidepressant until at least 12 months after the baseline visit (i.e., 12 months for patients initially randomized to antidepressant medication; 9 months for patients initially randomized to CBT). At the month 12 visit, patients discussed with a study physician the relative pros and cons of continuing medication during the second year of follow-up, with the decision determined by the patient’s preference. Regardless of when the patient discontinued their antidepressant or psychotherapy booster sessions, all patients continued in the Follow-up Phase until they dropped out, experienced relapse/recurrence or completed the follow-up period.

Outcomes

This analysis examined two primary outcomes: remission at the end of Phase II combination treatment and relapse/recurrence during the Follow-up Phase. Remission was defined as a HAM-D total score ≤7 at the final two Phase II ratings visits (week 22 and week 24 for completers), and response was defined as a HAM-D score ≤50% of their Phase 1 baseline score at the Phase II final rating visit (week 24 for completers). Inter-rater reliability for the HAMD-D was assessed using video-recorded interviews. The HAM-D intraclass correlation coefficient across the 14 masked raters was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.75-0.99). Relapse/recurrence was defined as meeting any of the following four criteria after entering the follow-up phase: 1) meeting criteria for a major depressive episode based on a LIFE score of 3 or greater; 2) a HAM-D score ≥14 for two consecutive weeks (patients with an HAM-D ≥14 at a follow-up visit were asked to return the following week for an additional rating); 3) a HAM-D score ≥14 at any follow-up visit and at which time the patient requested an immediate change in treatment; and 4) high risk of suicide, as determined by the study psychiatrist (23).

Analysis

Analyses were performed on the two Phase II groups: CBT+MED, comprising those who were initially randomized to CBT and had escitalopram added in Phase II, and MED+CBT, comprising those who were initially randomized to either escitalopram or duloxetine and had CBT added in Phase II. Due to the nonrandomized nature of these groups (i.e., group membership is dependent on previous treatment response), the group outcomes were not directly compared statistically but instead were analyzed separately or combined into one group. All patients who entered Phase II were non-remitters in Phase I, and for subgroup analyses they were divided into two groups based on their percentage improvement from Phase I baseline to Week 12: 1) non-responders (<50% improvement), and 2) non-remitting responders (i.e., ≥50% reduction). SPSS Version 24 was used to conduct all analyses. All missing data for non-completers (and otherwise) were imputed using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) multiple imputation method (31) using five imputations. Results presented are based on pooled test statistics across all imputations. Chi-square tests of independence were used to compare groups on categorical variables (i.e., remission, response, recurrence, or completion). Comparison of groups on continuous variables without covariates was performed using independent-sample t tests, or ANOVA. We also conducted an exploratory analysis predictor variables using generalized linear models, specifying a binary logistic model and including categorical predictors as factors and continuous predictors as covariates. Relapse/recurrence rates and mean number of days to recurrence were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier package in SPSS.

RESULTS

Patient Flow During Combination Treatment

The disposition of patients through the study is presented in Figures S1 and S2 in the online data supplement. There were 251 monotherapy treatment completers in Phase 1, including 114 remitters (32). Of the remaining 137, 13 non-remitters were not offered combination treatment because the second phase of the study had not yet been initiated, and 12 non-remitters declined to continue into combination, resulting in 112 participants entering Phase II. Of these Phase II participants, 37 had received CBT in Phase I and had escitalopram added in Phase II (CBT+MED). Seventy-five patients (30 duloxetine and 45 escitalopram) had received medication in Phase I and had CBT added in Phase II (MED+CBT). Fifteen (13.4%) individuals did not complete Phase II of treatment

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Phase II baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. Among the 112 patients starting Phase II treatment, 71 were non-responders and 41 were responders at the end of Phase I. During Phase I, the non-responders had experienced a significantly smaller percentage reduction in HAM-D scores than the responders (20.6 ± 21.2% vs 61.5 ± 9.7% respectively, p<.001), and had significantly higher Week 12 HAM-D scores (15.3 ± 4.6 vs 7.9 ± 2.4 respectively, p<.001). Those in the CBT+MED group had significantly higher depression scores on the HAM-D (t = 2.30, p = .021) and anxiety scores on the HAM-A (t = 1.97, p = .049) than those in the MED+CBT group at Phase II baseline. Importantly, we did not compare outcomes or moderators of response between the groups due to the nonrandomized nature of Phase II.

Table 1.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics at Phase II Baseline

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 112) | CBT + MED Group (N = 37) | MED + CBT Group (N = 75) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 41.7 | 11.7 | 40.4 | 11.6 | 42.4 | 11.6 |

| Age at first episode (years) | 32.4 | 14.9 | 33.1 | 13.7 | 32.1 | 15.5 |

| Measure | ||||||

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (17-item) | 12.6 | 5.3 | 14.1 | 5.0 | 11.7 | 5.3 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 12.4 | 7.6 | 14.9 | 9.1 | 11.6 | 6.8 |

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale | 10.8 | 5.1 | 12.3 | 5.2 | 10.1 | 5.0 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 60 | 54 | 16 | 43 | 44 | 59 |

| Female | 52 | 46 | 21 | 57 | 31 | 41 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 59 | 53 | 21 | 57 | 38 | 51 |

| Black | 21 | 19 | 4 | 11 | 17 | 23 |

| Other | 32 | 28 | 12 | 32 | 20 | 26 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 31 | 28 | 11 | 30 | 20 | 73 |

| Non-Hispanic | 81 | 72 | 26 | 70 | 55 | 27 |

| Married/cohabitating | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 48 | 15 | 41 | 39 | 52 |

| No | 58 | 52 | 22 | 59 | 36 | 48 |

| Education level | ||||||

| ≤12 years or trade school | 28 | 25 | 10 | 27 | 18 | 24 |

| Some college | 33 | 29 | 12 | 32 | 21 | 28 |

| ≥4-year college degree | 51 | 46 | 15 | 41 | 36 | 48 |

| Employed full-time | ||||||

| Yes | 52 | 47 | 15 | 41 | 37 | 49 |

| No | 60 | 54 | 22 | 59 | 38 | 51 |

| Current anxiety disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 57 | 51 | 18 | 51 | 39 | 52 |

| No | 55 | 49 | 19 | 49 | 36 | 48 |

| No. Lifetime episodes | ||||||

| 1 | 58 | 52 | 21 | 57 | 37 | 49 |

| 2 | 16 | 14 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 16 |

| ≥3 | 38 | 34 | 12 | 32 | 26 | 35 |

| Chronic episodes (≥2 years) | 35 | 31 | 8 | 22 | 27 | 36 |

| History of suicide attempt | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Insurance status | ||||||

| Private | 48 | 43 | 14 | 38 | 34 | 45 |

| Public | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| None | 63 | 56 | 23 | 62 | 40 | 53 |

CBT+MED: Cognitive behavior therapy in Phase I, with addition of escitalopram in Phase II

MED+CBT: Escitalopram or duloxetine in Phase I, with addition of cognitive behavior therapy in Phase II

Treatment Features

In Phase II the mean number of CBT sessions attended in the MED+CBT group was 13.4±2.9; for the CBT+MED group, the mean number of CBT booster sessions attended was 2.08±1.04. Of the 15 therapists who delivered CBT, the average independently-rated Cognitive Therapy Scale scores were above 40 for all but two, whose average was just slightly below 40. Among the patients starting Phase II, the mean doses of escitalopram and duloxetine at the beginning of Phase II were 17.6 ± 0.4 mg/day and 53.4 ± 1.2 mg/day, respectively. Seventy-nine percent of patients were titrated to the maximum dose (escitalopram 20 mg or duloxetine 60 mg daily) at some point during Phase II. The daily number of pills taken did not significantly differ across the groups, both at the end of Phase II and at the final visit during follow-up (p’s>.05). Mean Phase II endpoint medication doses for the CBT+escitalopram, escitlopram+CBT, and duloxetine+CBT groups were 16.1 ± 0.5 mg/day, 18.0 ± 0.4 mg/day, and 55.5 ± 1.0 mg/day, respectively. The proportions of long-term follow-up patients who discontinued the antidepressant during Phase II combination or during the follow-up phase, and the mean duration of antidepressant use during follow-up, did not meaningfully differ between CBT+MED and MED+CBT groups (Tables S1 and S2).

Completion Rates

Completion rates were similar in both treatment groups (CBT+MED: 84%; MED+CBT: 88%). Completers, compared with non-completers, did not differ significantly in their mean HAM-D score at Phase II baseline (12.4±5.4 versus 13.7±SD=4.4, respectively, t = .906, df = 110, p = .37). However, anxiety at Phase II baseline was significantly lower among completers than non-completers (10.4±4.9 versus 13.9±5.3, respectively, t = 2.48, df = 110, p = .015).

Outcomes

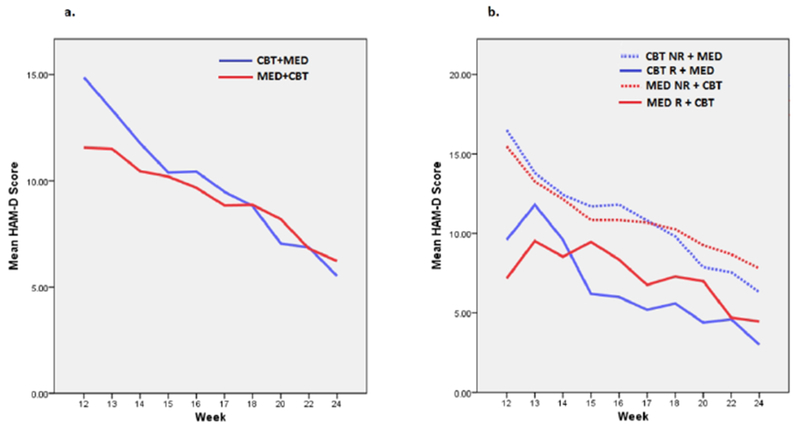

The mean estimated overall improvement on the primary outcome of the HAM-D was 8.2 (±2.0) for the CBT+MED group (t = 8.28, p<.0001) and 5.3 (±1.2) in the MED+CBT group (t = 8.85, p<.0001). The raw data HAM-D means over Phase II for the two treatment arms are shown in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

a) Change in mean HAM-D score during Phase II combination treatment by treatment group

b) Change in mean HAM-D score during combination treatment, stratified by level of response to monotherapy treatment

CBT+MED: Cognitive behavior therapy in Phase I, with escitalopram added in Phase II

MED+CBT: Escitalopram or duloxetine in Phase I, with CBT added in Phase II

CBT NR: Non-responder to CBT in Phase I; CBT R: Responder to CBT in Phase I

MED NR: Non-responder to antidepressant medication in Phase I; MED R: Responder to antidepressant medication in Phase I

Using the protocol definition of remission, 54/112 (48.2%) achieved remission during Phase II (CBT+MED: 20/37, 54.1%; MED+CBT: 34/75, 45.1%), and an additional 31 patients (27.6%) achieved response without remission. Response rates were 76% in both the CBT+MED group (28/37) and the MED+CBT group (57/75). Using the last observation carried forward and defining remission as a final visit HAM-D score ≤7 resulted in remission rates of 24/37 (64.9%) for the CBT+MED group and 45/75 (60%) for the MED+CBT group.

Table 2 shows the Phase II outcomes by level of response in Phase I. Overall, Phase I non-remitting responders had significantly better outcomes in Phase II than non-responders (χ2 = 6.01, df = 2, p = .049). Trajectories of treatment response during Phase II are shown in Figure 1b.

Table 2.

Categorical Phase II outcomes of sequential combination treatments by level of Phase I (monotherapy) response.

| Phase II Outcome |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remit | Response without remission | Non-Response | ||||

| End of Phase I Outcome | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Overall | ||||||

| Response without Remission (n=41) | 25 | 61 | 11 | 27 | 5 | 12 |

| Non-Response(n=71) | 29 | 41 | 20 | 28 | 22 | 31 |

| CBT+MED | ||||||

| Response without Remission (n=9) | 8 | 89 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| Non-Response(n=28) | 12 | 43 | 8 | 29 | 8 | 29 |

| MED+CBT | ||||||

| Response without Remission (n=32) | 17 | 53 | 11 | 34 | 4 | 13 |

| Non-Response(n=43) | 17 | 40 | 12 | 28 | 14 | 33 |

CBT+MED: Cognitive behavior therapy in Phase I, with addition of escitalopram in Phase II

MED+CBT: Escitalopram or duloxetine in Phase I, with addition of cognitive behavior therapy in Phase II

Predictors of Remission

Table 3 presents the predictive significance for Phase II remission of the demographic and clinical variables using an alpha level of 0.0047 to account for multiple testing. (HAM-D: Estimate = −0.127, SE = 0.045, p = .004; HAM-A: Estimate = −0.180, SE = 0.048, p = .0001). The severity of HAM-D scores and HAM-A scores at Phase II baseline were the only significant predictors of remission (HAM-D: Estimate = −0.127, SE = 0.045, p = .004; HAM-A: Estimate = −0.180, SE = 0.048, p = .0001). Table S3 in the data supplement contains test statistics of the prediction of remission during either Phase I or Phase II (N = 251). In addition to baseline HAM-D scores (χ2 = 6.44, df =1, p = .011) and baseline HAM-A scores (χ2 = 11.11, df =1, p = .001), the presence of a current anxiety disorder also predicted non-remission (χ2 = 6.86, df =1, p = .009).

Table 3.

Predictors of Phase II Remission to Combination Treatments

| Predictor effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Parameter estimate | SE | p |

| Severity (HAM-D) at Phase I Baseline | −0.019 | 0.060 | 0.748 |

| Severity (HAM-D) at Phase II Baseline | −0.127 | 0.045 | 0.004* |

| Chronic episode | 0.353 | 0.434 | 0.311 |

| Age | −0.015 | 0.017 | 0.380 |

| Anxiety (HAM-A) at Phase I Baseline | 0.005 | 0.046 | 0.910 |

| Anxiety (HAM-A) at Phase II Baseline | −0.180 | 0.048 | 0.0001* |

| Current Anxiety Disorder | −0.369 | 0.386 | 0.340 |

| Gender | −0.197 | 0.391 | 0.615 |

| Race | 0.470 | 0.997 | 0.637 |

| Married/cohabitating | 0.235 | 0.395 | 0.551 |

| Employed full time | 0.381 | 0.406 | 0.349 |

p<.0047

Due to the strong predictive effects of both depression and anxiety severity on remission, we examined whether significance for each persisted when controlling for the other. After controlling for the HAM-A score, the prediction of remission by HAM-D score at Phase II baseline was no longer significant (Estimate = −0.040, SE = 0.057, p = .485). In contrast, the prediction of remission by HAM-A score remained significant when controlling for HAM-D score (Estimate = −0.155, SE = 0.059, p = .009).

To evaluate whether anxiety was associated with treatment exposure, we examined the intensity of treatment exposure for anxious patients, defined as having a comorbid current anxiety disorder, or as a higher than median value HAM-A total score. During Phase I treatment, medication-treated patients with a comorbid current anxiety disorder received significantly higher doses than those without a comorbid anxiety disorder (1.72 ± .47 vs 1.54 ± .52 pills/day, respectively, p=.009). The higher doses were present for both escitalopram and duloxetine treated patients. No association with dose in Phase I was found using a median split of baseline HAM-A scores. During Phase II neither anxiety definition was associated with differences in medication dose. For patients receiving psychotherapy, neither definition of anxiety was significantly associated with CBT session attendance during Phase I or Phase II.

Effects of Preferences on Outcomes

Preference data at Phase I baseline were obtained for all but one of the 112 participants. 74 (66%) participants expressed a treatment preference (CBT: N=41, 36.6%; medication: N=33, 29.7%). To determine whether treatment preference led to drop out, we examined whether entry into Phase II was more or less likely among patients who received their preferred treatment in Phase I. There was no difference in Phase II participation between participants who received their preference in Phase I and those who did not (χ2 = 0.01, df =1, p = .94).

Nineteen (46.3%) of the CBT-preferring and 22 (66.7%) of the medication-preferring patients received their preferred treatment in Phase II. Drop out occurred in 5/35 (14.3%) patients who did not receive their preferred treatment in Phase II, versus 4/39 (10.3%) who did receive their preference and 6/37 (16.2%) who did not express a preference. There were no significant differences between patients who did versus those who did not receive their preferred treatment during Phase II in the rates of response (29/39, 74.4% vs. 25/35, 71.4%, χ2 = 0.08, df =1, p = .78), remission (16/39, 41.0% vs. 14/35, 40.0%, χ2 = 0.01, df =1, p = .93 or endpoint HAM-D score (7.9 ± 5.7 vs. 7.7 ± 6.4, p = .84).

Recurrence during Long Term Follow Up

Among the 97 Phase II completers, 80 (82%) participated in at least one follow up assessment of relapse/recurrence (CBT+MED: N=26; MED+CBT: N=53, Figure S2). Sixteen experienced recurrence of depression (20%), four (15.4%) were from the CBT+MED group and 12 (22%) were from the MED+CBT group. Fifty (62.5%) of the 80 follow-up participants had achieved remission at the end of Phase II. In an exploratory analysis of this subsample, the relapse/recurrence rate among responders who did not remit by the end of Phase II (N=9/30, 30%) trended toward being significantly higher than the rate among remitters (N=7/50, 14%) (χ2 = 3.00, df =1, p = .083). The overall mean number of days until relapse/recurrence was 226.8, (CBT+MED: 262.5±225.8; MED+CBT: 214.9±134.9) (Figure 2). The difference in anxiety scores at the end of Phase II between those who experienced recurrence during follow-up did not differ from those who remained recovered (mean HAM-A score: 4.20 vs 5.69, respectively, t=1.45, df =78, p=.15).

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier curve for relapse/recurrence by Phase II treatment group

Taking both treatment phases into account, there were 174 patients (94 Phase I remitters plus 80 responders or remitters from Phase II) who provided long-term follow-up data. In total, 29 (16.7%) met relapse/recurrence criteria across the 18-21 months of follow-up.

Outcomes from Phase I Baseline to Week 24

Finally, we examined the degree of improvement in HAM-D score after 24 weeks of treatment between those originally randomized to CBT, duloxetine, or escitalopram, regardless of whether they remitted in Phase I or continued to Phase II. 190 individuals had Week 24 data available, 93 of whom remitted in Phase I and 97 of whom completed Phase II. We conducted a one-way ANOVA of improvement scores and found no group differences between individuals who received the three treatments (F = 0.873, df = 2, p = .423); this indicates the degree of improvement was roughly equivalent regardless of initial treatment modality within a protocol initiating one treatment (either CBT or medication) followed by the addition of a complementary treatment upon non-remission at 12 weeks.

Using the last HAM-D observation carried forward from the beginning of Phase I in the PReDICT study’s total modified intent-to-treat sample (N=316), 205 (64.9%) patients achieved remission (defined as last observed HAM-D score ≤7) and an additional 29 (9.2%) attained response without remission, with 82 (25.9%) being non-responders.

DISCUSSION

Phase II of the PReDICT study was the first large trial to examine the sequential combination of CBT added to medication non-remitters versus antidepressant medication added to CBT non-remitters. The results provide highly relevant information for practicing clinicians. First, sequential addition of CBT after non-remission to antidepressant medication is an effective approach, as suggested by prior studies (8). Second, antidepressant medication was effective for both CBT non-responders and for non-remitting responders, indicating that antidepressants have efficacy even for residual symptoms in CBT non-remitters. Third, remission rates were similar regardless of the sequence of treatments administration. Fourth, both treatment sequences proved equally helpful in preventing relapse/recurrence. Thus, the sequential order for applying CBT and medication does not meaningfully affect acute or long-term treatment goals. Fifth, patient preferences for a specific treatment modality did not affect outcomes to combination treatment, consistent with small or negligible effects found in monotherapy comparisons (24,33) and meta-analyses (34,35), though one large trial did find preferences exerted a strong effect (36). Finally, after controlling for depression severity, the level of anxiety at the time of starting combination treatment significantly predicted non-remission, as reported in other trials (37,38), indicating the need to incorporate interventions targeting anxiety among depressed patients.

The outcomes from the combination treatments in Phase II of PReDICT differed based on the level of improvement with the first treatment. Among non-responders to the first treatment, the addition of the second treatment resulted in remission rates of about 40%, regardless of whether the first treatment was CBT, escitalopram, or duloxetine. In contrast, non-remitting responders to the first treatment had substantially better outcomes with the addition of the second treatment, with 61% remitting after addition of CBT to medication, and 89% remitting after addition of escitalopram to CBT. This finding that non-remitting responders improve more than non-responders replicates the effect found among medication-treated patients in the large REVAMP trial (39), and the current results extend that conclusion to patients initially treated with psychotherapy.

Several previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of adding psychotherapy to an antidepressant to address residual depressive symptoms (8). In contrast, there is a dearth of studies examining the addition of medication to psychotherapy responders. In our sample, 89% (8/9) of Phase I CBT responders achieved remission in Phase II, indicating that antidepressants are effective for converting CBT responders into remitters. Although this finding may seem to contradict the meta-analyses that suggest antidepressants are only more effective than placebo among severely ill patients (40,41), results from other analyses (42,43) and from studies of dysthymia (44) demonstrate efficacy of antidepressants in patients with milder forms of depression. The efficacy of antidepressants for mild symptoms also find support from a non-randomized study of recurrently depressed women by Frank and colleagues, who observed a 67% remission rate after addition of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) to ongoing interpersonal psychotherapy after non-remission to the therapy alone (45).

In comparison, trials in which non-responders or non-remitters to an antidepressant or psychotherapy were switched to the alternative treatment have generally found lower rates of improvement. Among chronically depressed patients initially randomized to 16 weeks of cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) or nefazodone and who failed to respond, remission rates among those switched to the psychotherapy were non-significantly higher than those switched to nefazodone (36% versus 27%, respectively) (46). This result differs from ours, but the studies are not directly comparable because in PReDICT the initial treatment was continued during the second phase, whereas in the nefazodone/CBASP trial the initial treatment was terminated when the second treatment was started. In STAR-D, among non-remitters to 12-14 weeks of citalopram who were randomized to switch to either CBT or an alternative antidepressant medication, remission rates were also relatively low (25% and 28%, respectively) (47). The substantially lower remission rates observed in these switch trials compared to the combination trials reviewed above suggest that psychotherapy-medication combination treatment may be superior to switching between these modalities for most non-remitting patients. However, not all sequential combination trials have found high levels of remission. In STAR-D, citalopram non-remitters experienced relatively low remission rates whether they were randomized to sequential addition of CBT or augmentation of citalopram by buspirone or bupropion (CBT addition: 23%, medication augmentation: 33%) (47). In the REVAMP study, recurrent depressed patients who did not remit after 12 weeks of pharmacotherapy were randomized to an additional 12 weeks of added CBASP, supportive therapy, or continued pharmacotherapy alone, finding roughly equivalent remission rates (approximately 40%) across the three treatment arms (39). Thus, although the weight of the evidence supports sequential combination over switching for monotherapy non-remitters, differences in the types of interventions and characteristics of the patients analyzed across studies prohibit definitive conclusions, particularly considering the difference in prior levels of treatment exposure across the study samples.

For the prevention of relapse/recurrence, the benefits of sequentially adding psychotherapy after monotherapy with medication are well-established, and are supported by the current study results. This preventive efficacy of CBT-based psychotherapies is most evident if the antidepressant is discontinued during follow-up (11,13). As with acute treatment outcomes, the benefits of added medication to prevent relapse/recurrence are less well established. Some support is found from a large randomized trial by Jarrett and colleagues of acute CBT responders who were considered to be at “higher risk” for relapse. In these patients, continued CBT or switch to fluoxetine produced equally low rates of relapse/recurrence (about 18%), and both were superior to placebo (33%), during 8 months of maintenance treatment; by the end of an additional 24 months of observational follow-up, relapse/recurrence rates still did not significantly differ between the two active treatment arms (48). The maintenance benefits of an antidepressant were also demonstrated in the two-year follow-up phase of the previously cited study by Frank and colleagues (45). In that study, patients requiring an SSRI+IPT to achieve remission experienced a 50% recurrence rate after tapering the SSRI, roughly double the 26% rate among those patients who remitted with IPT alone (45). These findings, combined with the results from the present analysis, justify the addition of antidepressant medication to reduce relapse/recurrence risk among CBT-non-remitters.

In a previous PReDICT study report, we found that the rate of relapse/recurrence among 94 remitters to Phase I monotherapy was 15.5%, with no difference between the treatment arms (32). This rate is only marginally lower than the overall 20% rate observed here among patients who responded after combination treatment, though Phase II patients who achieved remission relapsed half as often (14%) as those who were non-remitting responders (30%). These data reinforce the importance of remission as an important goal for long-term outcomes, and indicate that patients requiring combination treatment to achieve remission are about as likely to remain recovered over two years of follow-up as patients who remit with a monotherapy.

The current study found that pre-treatment anxiety predicted lower probability of remission for both the CBT+MED and MED+CBT combinations. Substantial evidence indicates that comorbid anxiety disorders and higher anxiety rating scale scores predict poorer outcomes to pharmacotherapy (37,38), though negative findings have also been reported (49,50). In contrast, several studies have failed to find an impact of anxiety on acute outcomes from CBT treatment for depression (18,51), though one large study had mixed findings (52). The recent CANMAT depression guideline asserts that insufficient evidence exists to support a predictive effect of anxiety symptoms or disorders on psychotherapy treatment outcomes for depression (53). Anxiety was not found to moderate outcomes in trials comparing patients randomized to CBT and antidepressant medication (18,54), though a recent analysis of three trials found that for chronically depressed patients with high levels of both depression and anxiety, CBASP was less effective than antidepressant medication, which in turn was less effective than the combination of the two treatments (55). In contrast, patients with moderate depression and low anxiety did better with the psychotherapy than medication (55). In one of the few studies of the impact of anxiety on depression recurrence after CBT treatment, Fournier and colleagues found that patients with anxiety level at baseline relapsed sooner than patients without anxiety (18). However, the effect of anxiety did not differ between CBT and medication treatment groups. Taken together, these results suggest that the presence of anxiety is a negative predictor of acute treatment outcomes for MDD, though its role as a moderator remains unclear..

An additional finding of interest was that although depression severity (HAM-D score) was a predictor of improvement, once the level of anxiety was controlled for, depression severity no longer predicted outcomes. Conversely, the negative predictive value of anxiety on outcomes persisted even after controlling for the effect of depression on anxiety scores. These results suggest that prior studies that identified depression severity as a negative predictor of outcome should be reanalyzed to examine whether the results persist after controlling for anxiety.

Although it is possible that discontinuation symptoms after stopping an SSRI (56) or SNRI (57) may be mistaken for depressive relapse (58), these concerns did not affect our data. Of the 16 patients who experienced recurrence during the follow-up phase, only 3 had discontinued the medication: one recurrence occurred 3 weeks after last dose; the other two occurred ≥8 months later. These data are similar to those observed in the Phase I remitters to medication alone; in that phase, of the 20 remitters who discontinued medication during follow-up, three experienced recurrence, and all three recurrences occurred ≥6 months after last dose (32).

A notable result was that 90.3% (112/124) of the non-remitting patients at the end of phase 1 accepted entry into Phase II. Furthermore, the completion rate of patients entering Phase II was 86%, with negligible difference between the phase II treatment arms. We speculate that these high rates stemmed from the requirement for study entry that patients be willing to be randomized to medication or psychotherapy treatment, and from trust built with the treatment team during Phase I. Clinicians should remain mindful of the utility evidence-based psychotherapies can provide to patients who do not remit with an antidepressant, and vice versa.

There are limitations to the generalizability of these results. First, of the enrolled adults, none had previously received an evidence-based treatment for depression and the comorbidity was limited; it is likely that response and remission rates would be lower among more complex patients and those with prior treatment histories. On the other hand, the medication doses were capped at the maximums recommended by the FDA for MDD, and thus below those often used in clinical practice, which may have limited the number of potential remitters to the medication treatments. Second, the patients enrolled in PReDICT were considered by the study psychiatrist to have MDD as their primary diagnosis requiring treatment. In clinical practice, patients presenting with MDD may have an anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder that is deemed more significant than the depression. In such cases, the outcomes from combination treatments may differ. In addition, although the effect size of adding antidepressant medication to non-remitting responders to CBT was large, the number of patients in this subgroup was small. Without a control condition, one cannot exclude the possibility that much of the patients’ improvements in Phase II were simply due to the passage of time while in treatment. PReDICT excluded individuals who were suicidal or depressed with psychotic features, for whom the order effects and overall efficacy of treatment combinations might differ. Finally, in phase II, patients who received CBT initially received only monthly booster sessions of CBT along with medication; this intensity of CBT in phase II may have been lower than necessary to see the full effects of combination treatment in these patients.

The results of this analysis indicate that CBT and pharmacotherapy are roughly equally efficacious for achieving remission when sequentially combined to non-responders or non-remitting responders to single-modality treatment. The only similar prior published trial, which evaluated the sequential addition of psychodynamic psychotherapy or antidepressant medication after poor response to single modality treatment in 29 patients, also found that both treatment combinations were effective (17). These studies support the conclusions of a recent meta-analysis of combination treatments that the effects of pharmacotherapy and those of psychotherapy on depression are largely independent (59). Taken together, the existing data support the rationale for combining treatments with differing mechanisms of action, and differing efficacy based on patients’ brain activity patterns (21,60,61), to optimize treatment outcomes. The sequential combination of CBT or antidepressant medication after non-remission to monotherapy is an effective approach for outpatients with MDD, and the sequence in which the treatments are applied does not appear to affect end-of-treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Leslie Sokol, PhD, and Jesus Salas, PhD, for performing the Cognitive Therapy Scale competency ratings.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants: P50 MH077083; R01 MH080880; UL1 RR025008; M01 RR0039; K23 MH086690; and the Fuqua family foundations. Forest Labs and Elli Lilly Inc. donated the study medications, escitalopram and duloxetine, respectively, and were otherwise uninvolved in study design, data collection, data analysis, or interpretation of findings. We thank Flavia Mercado, MD, for her assistance in operationalizing the study at the Grady Hospital location. We also thank the four reviewers whose guidance proved very helpful in improving this manuscript.

BWD has received research support from Acadia, Assurex Health, Axsome, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, , National Institute of Mental Health, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Takeda. He has served as a consultant to Assurex Health and Aptinyx.

CBN has received funding from National Institutes of Health and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. In the last 3 years he has served as a consultant to Xhale, Takeda, Taisho Pharmaceutical Inc., Bracket (Clintara), Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG) Healthcare & Biomedical Council, Fortress Biotech, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Janssen Research & Development LLC, Magstim, Inc., Navitor Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Intra-cellular Therapies, and served on the Board of Directors for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Gratitude America, and the Anxiety Disorders Association of America. CBN is a stockholder in Xhale, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Abbvie, OPKO Health, Inc., Bracket Intermediate Holding Corp., Network Life Sciences Inc., Antares, and serves on the Scientific Advisory Boards of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF), Xhale, Anxiety Disorders Association of America, Skyland Trail, Bracket (Clintara), RiverMend Health LLC, and Laureate Institute for Brain Research, Inc. CBN reports income sources or equity of $10,000 or more from American Psychiatric Publishing, Xhale, Bracket (Clintara), CME Outfitters, and Takeda, and has patents on the method and devices for transdermal delivery of lithium (US 6,375,990B1) and the method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy via transport inhibition of monoamine neurotransmitters by ex vivo assay (US 7,148,027B2).

SPC has received research support from EPA/SARE and has consulted on studies funded by Emory University, Georgia Department of Human Resources, NIH, NIMH, NSF, and the University of Wisconsin.

HSM has received consulting fees from St. Jude Medical Neuromodulation and Eli Lilly (2013 only) and intellectual property licensing fees from Abbott Labs.

WEC is a board member of Hugarheill ehf, an Icelandic company dedicated to the prevention of depression, and he receives book royalties from John Wiley & Sons. His research is also supported by the Mary and John Brock Foundation and the Fuqua family foundations. He is a consultant to the George West Mental Health Foundation and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America and the AIM for Mental Health Foundation.

DL, TMC, and BK report no competing interests

References

- 1.Weitz E, Hollon SD, Twisk J, et al. : Does baseline depression severity moderate outcomes between CBT and pharmacotherapy? An individual participant data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72:1102–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romera I, Perez V, Menchón JM, et al. : Social and occupational functioning impairment in patients in partial versus complete remission of a major depressive disorder episode. A six-month prospective epidemiological study. Eur Psychiatry 2010; 25:58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, Chelminski I: Heterogeneity among depressed outpatients considered to be in remission. Compr Psychiatry 2007; 48:113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nierenberg AA, Husain MM, Trivedi MH, et al. : Residual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D report. Psychol Med 2010; 40:41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuijpers P, De Wit L, Weitz E, et al. : The combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of adult depression: a comprehensive meta-analysis. J Evid-Based Psychot 2015; 15:147–168 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segal Z, Vincent P, Levitt A: Efficacy of combined, sequential and crossover psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in improving outcomes in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2002; 27:281–290 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craighead WE, Dunlop BW: Combination psychotherapy and antidepressant medication for depression: For whom, when and how. Ann Rev Psychol 2014; 65:267–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidi J, Tomba E, Fava GA: The sequential integration of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of the sequential model and a critical review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173:128–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunlop BW: Evidence-based applications of combination psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. FOCUS 2016; 14:156–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ionescu DF, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert JE: Pharmacological approaches to the challenge of treatment-resistant depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015; 17:111–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, et al. : Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: An individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73:565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, et al. : Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007; 75:475–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, van Straten A, et al. : Does cognitive behaviour therapy have an enduring effect that is superior to keeping patients on continuation pharmacotherapy? A meta-analysis BMJ Open 2013; 3(4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. : Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74:595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, 3rd ed Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2010, pp 17 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depression in Adults: Recognition and Management (Update). Clinical guideline 90 London, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009. www.nice.org.uk/CG90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dekker J, Van HL, Hendriksen M, et al. : What is the best sequential treatment strategy in the treatment of depression? Adding pharmacotherapy to psychotherapy or vice versa? Psychother Psychosom 2013; 82:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, et al. : Prediction of response to medication and cognitive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009; 77:775–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace ML, Frank E, Kraemer HC: A novel approach for developing and interpreting treatment moderator profiles in randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70:1241–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeRubeis RJ, Cohen ZD, Forand NR, et al. : The Personalized Advantage Index: translating research on prediction into individualized treatment recommendations. A demonstration. PLoS One 2014; 9:e83875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunlop BW, Rajendra JK, Craighead WE, et al. : Functional connectivity of the subcallosal cingulate cortex identifies differential outcomes to treatment with cognitive behavior therapy or antidepressant medication for major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2017; 174:533–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Thase ME, et al. : Predictors of longitudinal outcomes after unstable response to acute-phase cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder. Psychother 2015; 52:268–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunlop BW, Binder EB, Cubells JF, et al. : Predictors of remission in depression to individual and combined treatments (PReDICT): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012; 13:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Aponte-Rivera V, et al. : Effects of patient preferences on outcomes in the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) study. Am J Psychiatry 2017, 174:546–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al. : Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: Guilford; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fawcett J, Epstein P, Fiester SJ, Elkin I, Autry JH: Clinical management – imipramine/placebo administration manual: NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Psychopharm Bull 1987; 23:309–324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young J, Beck AT: Cognitive Therapy Scale: Rating manual. Unpublished manuscript, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al. : The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schafer JL: Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy JC, Dunlop BW, Craighead LW, Nemeroff CB, Mayberg HS, Craighead WE. Follow-up of monotherapy remitters in the PReDICT study: Maintenance treatment outcomes and clinical predictors of recurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol 2018; 86:189–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Mletzko TC, et al. : Depression beliefs, treatment preferences and outcomes in a randomized trial for major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2012; 46:375–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swift JK, Callahan JL: The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 2009; 65:368–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindhiem O, Bennett CB, Trentacosta CJ, et al. : Client preferences affect treatment satisfaction, completion, and clinical outcome: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2014; 34:506–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Markowitz JC, et al. : Patient preference as a moderator of outcome for chronic forms of major depressive disorder treated with nefazodone, cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, or their combination. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70: 354–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. : Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165: 342–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiethoff K, Bauer M, Baghai TC, et al. : Prevalence and treatment outcome in anxious versus nonanxious depression: results from the German Algorithm Project. J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 71:1047–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kocsis JH, Gelenberg AJ, Rothbaum BO, et al. : Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and brief supportive psychotherapy for augmentation of antidepressant nonresponse in chronic depression: the REVAMP Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:1178–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, et al. : Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med 2008; 5(2):e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. : Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA 2010; 303:47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, et al. : Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69:572–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perahia DGS, Kajdasz DK, Walker DJ, et al. : Duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of milder major depressive disorder. Int J Clin Pract 2006; 5:613–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levkovitz Y, Tedeschini E, Papakostas GI: Efficacy of antidepressants for dysthymia: a metaanalysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72:509–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, Spanier CA, et al. : Interpersonal psychotherapy and antidepressant medication: evaluation of a sequential treatment strategy in women with recurrent major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:51–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schatzberg AF, Rush AJ, Arnow BA, et al. : Chronic depression: medication (nefazodone) or psychotherapy (CBASP) is effective when the other is not. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thase ME, Friedman ES, Biggs MM, et al. : Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:739–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jarrett RB, Minhajuddin A, Gershenfeld H, Friedman ES, Thase ME. Preventing depressive relapse and recurrence in higher-risk cognitive therapy responders: a randomized trial of continuation phase cognitive therapy, fluoxetine, or matched pill placebo. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70:1152–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Papakostas GI, Larsen K: Testing anxious depression as a predictor and moderator of symptom improvement in major depressive disorder during treatment with escitalopram. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011; 261:147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nelson JC: Anxiety does not predict response to duloxetine in major depression: results of a pooled analysis of individual patient data from 11 placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety 2010; 27:12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McEvoy PM, Nathan P: Effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for diagnostically heterogeneous groups: a benchmarking study. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007; 75:344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. : Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parikh SV, Quilty LC, Ravitz P, et al. : Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 2. Psychological Treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2016; 61:524–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sotsky SM, Glass DR, Shea MT, et al. : Patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: findings in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:997–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furukawa TA, Efthimiou O, Weitz ES, et al. : Cognitive-Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy, drug, or their combination for persistent depressive disorder: Personalizing the treatment choice using individual participant data network metaregression. Psychother Psychosom 2018; 87:140–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C, Guidi J, Offidani E. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: A systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2015; 84:72–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fava GA, Benasi G, Lucente M, Offidani E, Cosci F, Guidi J. Withdrawal symptoms after serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: Systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2018; 87:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fava GA, Belaise C: Discontinuing antidepressant drugs: lesson from a failed trial and extensive clinical experience. Psychother Psychosom 2018; 87:257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, et al. : Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2014; 13:56–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McGrath CL, Kelley ME, Holtzheimer PE, et al. : Toward a neuroimaging treatment selection biomarker for major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 2013; 70:821–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, McGrath CL, Craighead WE, Mayberg HS: Preliminary findings supporting insula metabolic activity as a predictor of outcome to psychotherapy and medication treatments for depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2015; 27:237–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.