Abstract

The isolation and structure elucidation of one new fungal metabolite, phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a), and four previously reported metabolites (1b, 2a, 3-4) from the citrus phytopathogen Phyllosticta citricarpa LGMF06 are described. The new dioxolanone phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a) had low phytotoxic activity in citrus leaves and fruits (at dose of 100 μg), and its importance as virulence factor in citrus black spot disease needs to be further addressed. Beside the phytotoxic analysis, we also evaluated the antibacterial (against methicillin sensitive and resistant Staphylococcus aureus) and cytotoxic (A549 non-small cell lung cancer, PC3 prostate cancer and HEL 299 normal epithelial lung) activities of the isolated compounds, which revealed that compounds 1a, 1b and 2a were responsible for the antibacterial activity of this strain.

Introduction

Phyllostica citricarpa is an important pathogen associated with citrus black spot (CBS) disease, causing severe economic losses to citrus producers in South Africa, Brazil and the United States [1, 2]. Besides CBS, Phyllosticta species are responsible for diseases in several crops including grape, horse chestnut, papaya, pomelo fruit and banana [3]. To control diseases caused by Phyllosticta species, it is important to understand the mechanisms involved in this pathosystem. Experiments with pathogen culture filtrates have shown that tissue response in vitro may correlate with disease reaction of the host species and the isolated compounds produced by the phytopathogen may allow to understand the virulence and pathogenicity mechanisms, as well as to select important traits to disease control [4]. The investigation of dioxolanone as a virulence factor in four species of Phyllosticta were performed by Buckel et al. [5]. The authors demonstrated that phenguignardic acid (1c) and guignardic acid are involved in the development of grape black rot, a serious disease in grapes. Guignardic acid was described as the first member of a new class of natural compounds containing a dioxolanone moiety in 2001, since then, dioxolanone derivatives have been isolated from Phyllosticta species and other genera, such as Aspergillus, [6–8] as potential virulence factors. Based on these data we isolated and characterized the secondary metabolites produced by P. citricarpa LGMF06, a fungus strain isolated from lesions of CBS in Brazil, in order to identify the major secondary metabolites produced by this phytopathogen.

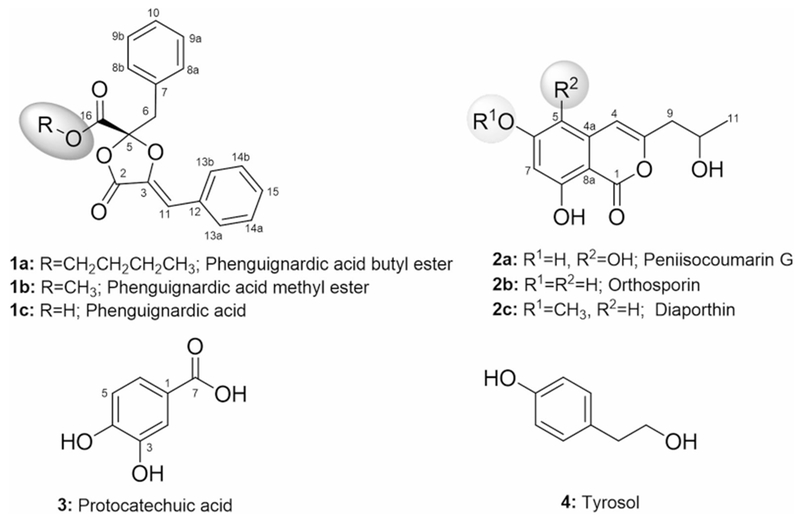

After a large-scale fermentation of the fungus strain LGMF06 in malt extract medium (Fig. S1), the extraction of the filtrate resulted in 752 mg of brown oil crude extract. Purification of the obtained crude extract (752 mg) using various chromatographic techniques afforded one new compound, phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a), along with four previously reported compounds [phenguignardic acid methyl ester (1b), peniisocoumarin G (2a), protocatechuic acid (3) and tyrosol (4)], (Fig. 1 and supplementary file, Fig. S1). The chemical structure of the new metabolite (1a) was determined by cumulative 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy, high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), chemical synthesis and by comparison with related structures [5–9].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of compounds 1a-4

The physicochemical properties of compounds 1a, 1b and 3-4 are summarized in the experimental section (see Supplementary Information). Compound 1b (15.0 mg) was isolated as brown oil using standard chromatographic techniques (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1), and its spectroscopic and spectrometric data were consistent with phenguignardic acid methyl ester, a dioxolanone originally isolated and characterized from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus flavipes AIL8 [8]. The physicochemical properties of compound 1a (6.3 mg) were similar to those of 1b. The molecular formula of 1a was deduced as C22H22O5 on the basis of (+)-HRESI-MS [m/z 384.1809 [M + NH4]+ (calcd for C22H26N1O5, 384.1805)] and NMR, with a molecular mass of 42 amu higher than that of 1b, which is corresponding to C3H6. The proton NMR data of 1a in CD3OD (Table 1) were almost identical to those of 1b, except for the missing of a singlet methoxy at δH 3.84 (in 1b) and the presence of a new signals at δH 4.27 (2H, CH2-18), δH 1.63 (2 H, CH2-19) and δH 1.33 (2H, CH2-20), along with a triplet methyl signal at δH 0.87 (3 H, CH3-21). Likewise, the 13C NMR and HSQC spectra of 1a (Table 1) differed from that of 1b: a methoxy group of 1b (δC 53.9, CH3-18) was replaced by four up-field shifted signals at δC 68.0 (CH2-18), δC 31.6 (CH2-19), δC 20.1 (CH2-20) and δC 14.0 (CH3-21), consistent with the replacement of the methoxy group of 1b (16-OCH3) with an butoxy group (−OCH2CH2CH2CH3) in 1a (Fig. 1, Supplementary Information, Fig. S2, and Table 1). Cumulative analyses of the 1H,1H-COSY/HMBC/TOCSY/NOESY spectra (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2) also confirmed the presence of the butyl group in 1a, and a key 3JC-H HMBC correlation from the methylene group at δH 4.27 (CH2-18) to C-16 (δC 166.8); Fig. S2 confirmed the attachment of the butoxy group at 16-position. All of the remaining HMBC correlations (Fig. S2) and NMR data (Table 1) are in full agreement with structure 1a. The absolute configuration of 1a stereocenter was established by comparison of the NMR shifts, optical rotation to those of 1b (which have been isolated/characterized from the same strain crude extract), and by its total synthesis (Table 1, Experimental Section and Supplementary Information, Fig. S4). Compounds 1a and 1b were chemically synthesized from phenguignardic acid (1c) following the procedure previously described by Stoye et al. [7]. Treatment of 1c with methyl iodide and n-butyl bromide in acetone using K2CO3 as the base yielded the phenguignardic acid methyl ester (1b, 65%) and phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a, 55%), respectively (Fig. S4). The 1H NMR data of 1a and 1b were in full agreement to those of our isolated natural products (Figs S8, S9 and S26, S29) and the reported data of 1b [7, 8]. In summary, cumulative analyses of 1D (1H, 13C) and 2D (HSQC, 1H/1H-COSY, TOCSY, HMBC and NOESY) NMR and chemical synthesis established the structure of 1a (Fig. 1) as a new dioxolanone analogue and was named as phenguignardic butyl ester. It is also important to note that, the NMR assignments of 1b was incorrectly reported in literature [the NMR data at the two aromatic rings were switched (positions C-6 to C-15)] and this has been corrected herein for the first time [8].

Table 1.

13C (100 MHz) and 1H (400 MHz) NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 1a and 1b (δ in ppm)

| Position | Compound 1a (CD3OD) |

Compound 1a (CDCl3) |

Compound 1b (CDCl3) |

Compound 1b (CDCl3) [8]a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, type | δH (mult, J in [Hz]) | δC, type | δH (mult, J in [Hz]) | δC, type | δH (mult, J in [Hz]) | δC, type | δH (mult, J in [Hz]) | |

| 2 | 163.8, C | 162.7, C | 162.6, C | 162.3, C | ||||

| 3 | 136.9, C | 135.6, C | 135.4, C | 135.2, C | ||||

| 5 | 106.9, C | 105.5, C | 105.4, C | 105.2, C | ||||

| 6 | 41.3, CH2 | 3.61 (d, 14.8) | 40.8, CH2 | 3.55 (d, 14.7) | 41.0, CH2 | 3.56 (d, 14.7) | 109.6, CH | 6.33 (s) |

| 3.55 (d, 14.7) | 3.50 (d, 14.6) | 3.50 (d, 14.8) | ||||||

| 7 | 132.6, C | 130.9, C | 130.7, C | 132.2, C | ||||

| 8a/8b | 132.4, CH | 7.30 (m) | 131.2, CH | 7.29-7.20 (m, overlapped) | 131.2, CH | 7.26 (m) | 129.8, CH | 7.67 (d, 7.5) |

| 9a/9b | 129.5, CH | 7.24 (m) | 128.7, CH | 7.29-7.20 (m, overlapped) | 128.7, CH | 7.24 (m) | 128.7, CH | 7.44 (d, 7.5) |

| 10 | 128.9, CH | 7.24 (m) | 128.1, CH | 7.29-7.20 (m, overlapped) | 128.1, CH | 7.24 (m) | 129.0, CH | 7.38 (t, 7.5) |

| 11 | 110.1, CH | 6.30 (s) | 109.7, CH | 6.30 (s) | 109.9, CH | 6.29 (s) | 40.8, CH2 | 3.61 (dd, 15.0) |

| 12 | 133.7, C | 132.4, C | 132.3, C | 130.6, C | ||||

| 13a/13b | 131.0, CH | 7.67 (d, 8.0) | 130.0, CH | 7.61 (dd, 7.0, 1.2) | 130.1, CH | 7.62 (d, 7.2) | 131.0, CH | 7.32 (m) |

| 14a/14b | 129.9, CH | 7.40 (t, 7.4) | 128.9, CH | 7.42-7.32 (m, overlapped) | 129.0, CH | 7.39 (t, 7.2) | 128.4, CH | 7.28 (m) |

| 15 | 130.3, CH | 7.37 (t, 7.2) | 129.2, CH | 7.42-7.32 (m, overlapped) | 129.3, CH | 7.35 (m) | 127.8, CH | 7.28 (m) |

| 16 | 166.8, C | 165.6, C | 166.0, C | 165.8, C | ||||

| 18 | 68.0, CH2 | 4.27 (tt, 6.4, 2.8) | 67.2, CH2 | 4.22 (t, 6.6) | 53.9, CH3 | 3.84 (s) | 53.6, CH3 | 3.87 (s) |

| 19 | 31.6, CH2 | 1.63 (dt, 14.3, 6.6) | 30.5, CH2 | 1.61 (m) | ||||

| 20 | 20.1, CH2 | 1.33 (m) | 19.1, CH2 | 1.29 (m) | ||||

| 21 | 14.0, CH3 | 0.87 (t, 7.4) | 13.7, CH3 | 0.85 (t, 7.4) | ||||

See Supplementary Information for NMR spectra. Assignments supported by 2D HSQC and HMBC experiments.

The NMR assignments of 1b have been wrongly reported in literature [they have switched the NMR data at the two aromatic rings (positions C-6 to C-15)] and this been corrected herein.

Compound 2a was isolated as pale yellow solid using various chromatographic techniques (Fig. S1). The physicochemical properties and UV/VIS spectrum of 2a (λmax 230, 265, 350 nm) suggested an isocoumarin chromophore for 2a, the molecular formula of 2a was deduced as C12H12O6 on the basis of (−)-HRESI-MS [m/z 251.0553 [M − H]− (calcd for C12H11O6, 251.0561), 503.1187 [2M − H]− (calcd for C24H23O12, 503.1195)]. Based on the analyses of 1D and 2D NMR spectra (Fig. S2 and Table S1), the planar structure of 2a appears to be same as penisocoumarin G (5-hydroxy-orthosporin), an isocoumarin recently reported from the endophytic fungus Penicillium commune QQF-3 [10]. Finally, based on the NMR and MS data analyses, compounds 3 and 4 were identified as protocatechuic acid and tyrosol, respectively (Fig. 1), which are common metabolites previously reported from plants and fungi [11, 12].

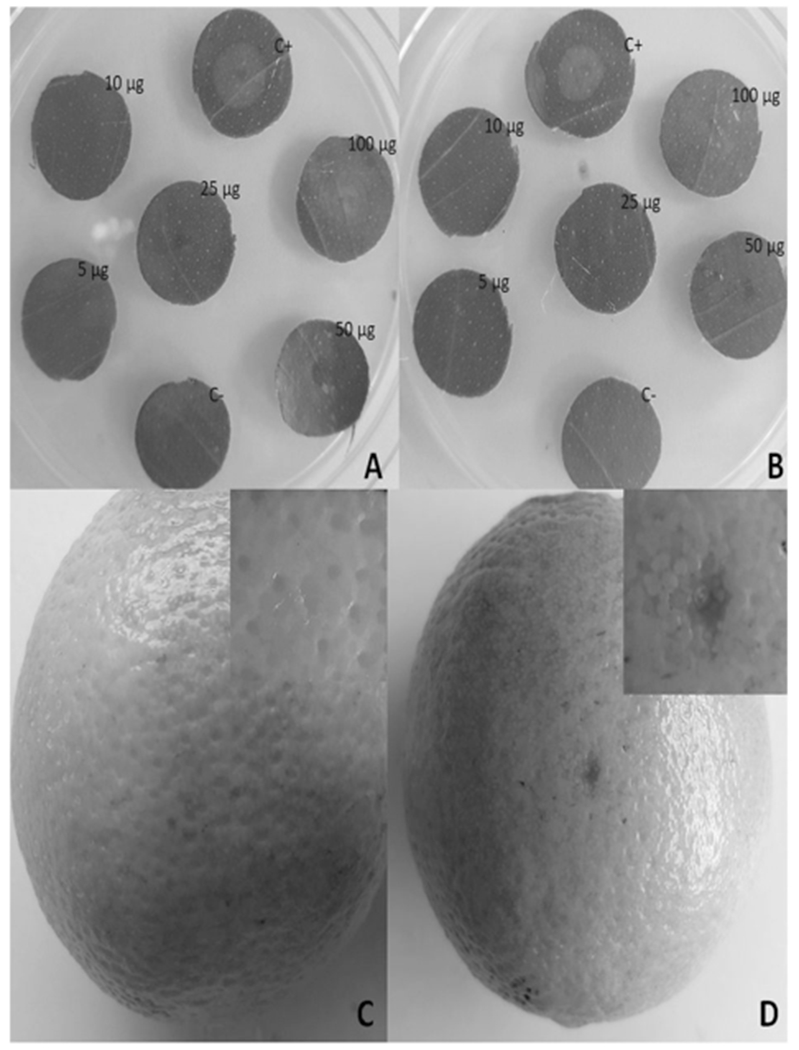

Compound 1b was isolated previously from Aspergillus sp. in 2014, and until now, there was not much information reported regarding the biological activity of this compound, neither antibacterial nor cytotoxicity data were available. Based on this information, and the isolation of a new dioxolanone analogue (1a), we decided to evaluate the phytotoxic activities of these dioxolanones (1a, 1b) and peniisocoumarin G (2a) in the host plant tissues. To avail larger quantities for the biological analysis compounds 1a and 1b were chemically synthetized from phenguignardic acid (1c) (see experimental section), and 1c was synthesized following the procedure previously described by Stoye et al. [7]. The plant assays were conducted using leaf disks of Citrus sinensis, Citrus reticulate and Citrus limon and the treatment with compound 1a, at a dose of 100 μg, resulted in lesion development after 12 h of inoculation in C. sinensis (Fig. 2a, b), C. reticulate, and after 24 h in C. limon (Fig. S52). However, even after 48 h compound 1b did not cause any lesion, even at the higher dose (100 μg), in any of the plants species evaluated. We also assayed the cytotoxicity of phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a) in C. sinensis fruits, and a small necrotic zone, similar to CBS lesion, was observed in the area where compound 1a was deposited (Fig. 2d). The epidemiological and infection processes of CBS were explored in various studies [2, 13]. It was suggested that the production of pycnidia in fruits is related to the disease symptoms, however the impact of phytotoxins in the disease development, to date, has not been addressed. Therefore, it is possible that phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a), a new dioxolanone, is involved in the development of CBS by P. citricarpa, in view of its toxicity in citrus leaves and fruits. Phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a) is closely related to compound phenguignardic acid (1c), with a butoxy group attached at 16-position (instead of an OH group, Fig. 1), and phenguignardic acid (1c) was described as an important virulence factor in the grape black rot disease development, caused by Guignardia bidwellii (P. ampelicida) [5]. Interestingly, the mechanism of action of this class of compounds remains unknown, and some authors suggested that these compounds could be used as an herbicide, because of their non-host specific toxicity [14]. In addition, orthosporin and closely related compounds, such as diaporthin, can be associated with necrosis in some plants [15], however, at 100 μg, 5-hydroxy-orthosporin (2a) did not show any toxicity in citrus leaves or fruits, suggesting that this compound is not related with CBS development.

Fig. 2.

Phytotoxicity assay in Citrus sinensis leaf disks and fruits. a, b cytotoxicity of phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a) and phenguignardic acid methyl ester (1b) in leaves, respectively; c control with methanol; d cytotoxicity of phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a) in fruits. C+ positive control, 10% of lactic acid, c methanol

Compounds 1a, 1b, 2a, 3 and 4 were also evaluated for their antibacterial and cytotoxic activities, i.e. against Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin resistant S. aureus and against three human cancer cell lines (A549, non-small cell lung cancer; PC3, prostate cancer; and HEL 299, normal epithelial lung). None of the compounds demonstrated cytotoxicity to human cancer cells at concentrations below 80 μM (Fig. S3). However, phenguignardic acid butyl ester (1a) displayed low activity against both methicillin sensitive and resistant S. aureus, an MIC value of 111 μg ml−1 (Table S2). Thus, the methoxy group attached at 16-position in 1b reduced its antibacterial activity (MIC of 333 μg ml−1), in comparison with the butoxy group in the same position in 1a (Table S2), which suggest that modifications at 16-position of these molecules influence the antibacterial activity of this class of molecules. Peniisocoumarin G (2a) also displayed antibacterial activity against S. aureus (MIC 333 μg ml−1 - Table S2); however, the closely related compound orthosporin showed even lower activity in the disc diffusion analysis performed by Medeiros et al. [16]. Isocoumarins are common plant metabolites, and were reported having a broad range of biological activities, including antibacterial, anti-fungal and cytotoxic. For example, the isocoumarin NM-3 was in phase I of clinical tests due its antineoplastic effect [17]. Consistent with previous reports [11, 12] protocatechuic acid (3) and tyrosol (4) did not show any biological activity in our assays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants CA 91091, GM 105977 and an Endowed University Professorship in Pharmacy to J.R. This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health grants R24 OD21479 (JST), the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001998). It was also supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico–Brazil grant 424738/2016-3 and CNPq309971/2016-0 to C.G., and CAPES-Brazil – grant to D.C.S. We thank the College of Pharmacy NMR Center (University of Kentucky) for NMR support.

Footnotes

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41429-019-0154-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Glienke C, et al. Endophytic and pathogenic Phyllosticta species, with reference to those associated with citrus black spot. Persoonia. 2011;26:47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guarnaccia V, et al. First report of Phyllosticta citricarpa and description of two new species, P. paracapitalensis and P. paracitricarpa, from citrus in Europe. Stud Mycol 2017; 87:161–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wikee S, et al. Phyllosticta capitalensis, a widespread endophyte of plants. Fungal Div 2013;60:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amusa NA. Microbially produced phytotoxins and plant disease management. Afr J Biotechnol 2006;5:405–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckel I, et al. Phytotoxic dioxolanones are potential virulence factors in the infection process of Guignardia bidwellii. Sci Rep 2017;7:8926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckel I, et al. Phytotoxic dioxolanone-type secondary metabolites from Guignardia bidwelli. Phytochemistry. 2013;89: 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoye A, Kowalczyk D, Opatz T. Total Synthesis of (+)-Phenguignardic acid, a phytotoxic metabolite of Guignardia bidwellii. Eur J Org Chem 2013; 5952–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai Z-Q, et al. New phenyl derivates from endophytic fungus Aspergillus flavipes AIL8 derived of mangrove plant Acanthus ilicifolius. Fitoterapia. 2014;95:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molitor D, et al. Phenguignardic acid and guignardic acid, phytotoxic secondary metabolites from Guignardia bidwelli. J Nat Prod 2012;75:1265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai R, Wu Y, Chen S, Cui H, Liu Z, Li C, She Z. Peniisocoumarins A-J: isocoumarins from Penicillium commune QQF-3, an endophytic fungus of the mangrove plant Kandelia candel. J Nat Prod 2018;81:1376–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meepagala KM, et al. Isolation of a phytotoxic isocoumarin from Diaporthe eres-infected Hedera helix (English Ivy) and synthesis of its phytotoxic analogs. Pest Manag Sci 2018;74:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teichmann K, et al. In vitro inhibitory effects of plant-derived by-products against Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasite. 2016;23:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulin EH, et al. Identification of genes associated with asexual reproduction in Phyllosticta citricarpa mutants obtained through Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformation. Microbiol Res 2016; 192:142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molitor D, Beyer M. Epidemiology, identification and disease management of grape black rot and potentially useful metabolites of black rot pathogens for industrial applications-a review. Appl Biol 2014;165:305–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee IK, Seok SJ, Kim WG, Yun BS. Diaporthin and orthosporin from the fruiting body of Daldinia concentrica. Mycobiology. 2006;34:38–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Medeiros AG, et al. Bioprospecting of Diaporthe terebinthifolii LGMF907 for antimicrobial compounds. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2018;63:499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oikawa T, et al. Effects of cytogenin, a novel microbial product, on embryonic and tumor cell-induced angiogenic responses in vivo. Anticancer Res 1997;17:1881–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.