Abstract

Spontaneous uterine rupture during early pregnancy is an extremely rare occurrence and may vary in presentation and course of events, hence the clinical diagnosis is often challenging. We present our experience with two such cases of spontaneous uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy without any identifiable underlying risk factors. The first case was at 12 weeks of gestation and the second case was at 6 weeks gestational age (GA). Both cases were diagnosed and managed by the laparoscopic approach. We are reporting the earliest documented GA in which spontaneous uterine rupture occurred. So far, the earliest GA reported in the literature according to our knowledge was at 7+3 weeks. Access to a laparoscopic facility is crucial in the early definitive diagnosis and prompt management of these cases, since this may significantly reduce the risk of severe morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: pregnancy, ultrasonography

Background

Spontaneous uterine rupture during early pregnancy is an extremely rare but potentially life-threatening condition. The presentation and course of events in these cases vary widely, which makes the clinical diagnosis quite challenging. Imaging modalities may miss the diagnosis of uterine rupture, especially in its early stage. Most commonly, these patients present with a hemoperitoneum of unknown origin in the presence or absence of an intrauterine pregnancy. We report two cases of spontaneous uterine rupture in the first trimester pregnancy without any clear underlying risk factors.

Case presentation

The first case was a G4P2+1 pregnant woman aged 27 years. Her obstetric history consisted of two full-term vaginal deliveries. She had a laparotomy with right salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy 4 years ago. This pregnancy was spontaneous and uneventful until 12 weeks gestational age (GA). The second case was a G4P1+3 pregnant female aged 34 years. Her obstetric history consisted of one full-term vaginal delivery followed by a laparotomy with left-sided salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy; and a laparoscopic right salpingectomy for isthmic tubal pregnancy. The current pregnancy was an IVF conception at 5+5 weeks of GA.

Both cases presented to our emergency department with severe lower abdominal pain of a few hours duration, associated with nausea and vomiting. On examination, they were distressed with pain, mildly distended abdomen with significant lower abdominal tenderness. However, their vital signs and laboratory results were within normal.

Emergency pelvic sonography showed:

First case: moderate pelvic free fluid, and a gravid uterus with intrauterine live fetus; crown rump length (CRL) corresponding to 11+3 weeks.

Second case: small intrauterine sac, likely pseudo sac with right adnexal heterogeneously echogenic collection 6×3 cm suggestive of ruptured right ectopic pregnancy.

Both ultrasounds failed to diagnose or even suspect the uterine rupture.

Differential diagnosis

Such a clinical presentation raises the differential diagnosis of gynaecological incidents such as ruptured adnexal cyst, that is, corpus cyst, or ruptured ectopic pregnancy; and non-gynaecological conditions such as appendicitis. In both cases, the differentiation is usually based on clinical exam and imaging modalities, which is most challenging to the physician. However, laparoscopic diagnosis is a vital step in the clinical approach and timely management of these cases.

Treatment

Emergency laparoscopy was done for the first case due to her persistent and increasing pain and tenderness in the clinical exam without a clear diagnosis. This revealed a hemoperitoneum of 2 L and a 3–4 cm left fundal uterine rupture with protrusion of amniotic sac and placental tissue (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Left fundal uterine rupture of 3–4 cm.

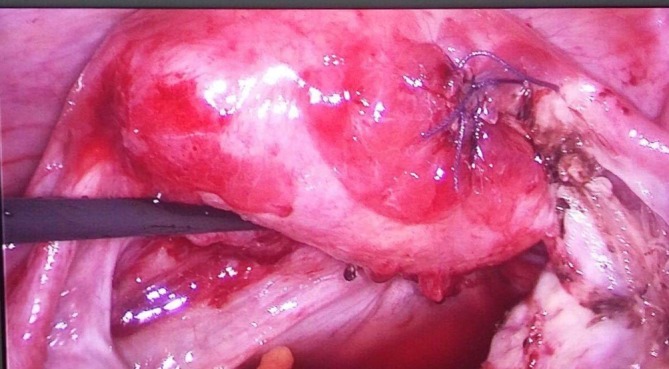

Emergency laparoscopy was also done for the second case due to her preliminary diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy, which revealed a hemoperitoneum of 1.5 L and a 2 cm right fundal uterine rupture (figure 2). No ectopic pregnancy was found.

Figure 2.

Right fundal uterine rupture of 2 cm after suturing.

In both cases, the product of conception were removed and hemostasis secured with laparoscopic suturing of the uterine defect using Vicryl sutures.

Outcome and follow-up

Both women had an uneventful postoperative recovery. Histopathology was consistent with the products of conception with no evidence of molar changes.

Discussion

Uterine rupture is seen usually in a scarred uterus either in late pregnancy or labour.1 First-trimester uterine rupture is very rare and poses a diagnostic dilemma. Few cases have been reported in the literature.1–3 We are reporting the earliest GA encountered at the time of spontaneous rupture according to our review of available literature. The exact aetiology of uterine rupture in our two cases is unclear, but the possibility of trophoblastic invasion at the site of previous uterine wall thinning as a result of either perforation with a manipulator during the previous salpingectomy or inherited myometrial weakness due to collagen disorders cannot be excluded.

Learning points.

Clinicians should be aware of this rare but serious complication of hemoperitoneum in early pregnancy.

Ultrasound findings of hemoperitoneum/fluid collection with an intrauterine pregnancy do not exclude uterine rupture, especially at an early stage.

It is probable that uterine perforation during any gynaecology procedure that involves instrumentation of the uterus is far more common than we recognise and that is why it is recommended to review previous operation notes (if available) in women with atypical presentation who have had such procedures previously, and to have a low threshold for suspecting uterine perforation during any gynaecology surgery.

Access to a laparoscopic facility is essential in the early definitive diagnosis and prompt management is required as this may significantly reduce the risk of severe morbidity and mortality.

Footnotes

Contributors: BA: planning, conduct and reporting. GL: supervision and revising. BA and GL: perform the surgery and management.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Biljan MM, Cushing K, McDicken IW, et al. Spontaneous uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;16:174–5. 10.3109/01443619609004098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nassar AH, Charara I, Nawfal AK, et al. Ectopic pregnancy in a uterine perforation site. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:e15–e16. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh A, Jain S. Spontaneous rupture of unscarred uterus in early pregnancy--a rare entity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:431–2. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079005431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]