Abstract

Ciguatera is a common but underreported tropical disease caused by the consumption of coral reef fish contaminated by ciguatoxins. Gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms predominate, but may be accompanied by cardiovascular features such as hypotension and sinus bradycardia. Here, we report an unusual case of junctional bradycardia caused by ciguatera in the Caribbean; to our knowledge, the first such report from the region. An increase in global sea temperatures is predicted to lead to the spread of ciguatera beyond traditional endemic areas, and the globalisation of trade in coral reef fish has resulted in sporadic cases occurring in developed countries far away from endemic areas. This case serves as a reminder to consider environmental intoxications such as ciguatera within the differential diagnosis of bradycardias.

Keywords: arrhythmias, poisoning

Background

An estimated 50 000–5 00 000 cases of ciguatera occur annually in tropical and subtropical regions associated with coral reefs.1 The uncertainty regarding the true incidence is due to the remoteness of many ciguatera endemic areas, and to the fact that many cases are mild and never present to healthcare facilities.1 However, an increase in global sea temperatures is predicted to lead to the spread of ciguatera beyond traditional endemic areas,2 and the globalisation of trade in coral reef fish for human consumption has resulted in sporadic cases occurring in developed countries far away from endemic areas.1 2 We describe the case of a 58-year-old man who presented to the emergency department of a Caribbean hospital with gastrointestinal symptoms following a meal of barracuda and was found to have a junctional bradycardia. The presence of gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms in multiple family members who shared the meal was highly suggestive of the diagnosis of ciguatera intoxication. Although hypotension and sinus bradycardia are well recognised in ciguatera, conduction blocks may also occur, and the case serves as a reminder to consider environmental intoxications in the differential diagnosis of bradycardias.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old man presented to the emergency department of a hospital in Aruba (Southern Caribbean) with diarrhoea, light-headedness and a feeling of intense cold. He reported no chest pain, shortness of breath or other cardiorespiratory or neurological symptoms. Nine hours earlier, the patient and five family members had shared a meal of barracuda. The fish had been bought from a street seller and cooked at home. Profuse, watery diarrhoea had developed in all six family members within a few hours of the meal.

The patient had no previous medical or surgical history, took no regular medications and had no known allergies. He drank alcohol occasionally, did not smoke and denied illicit drug use. One week previously, he had eaten barracuda bought from the same seller. He had experienced diarrhoea and pruritus, but had not felt unwell enough to seek medical attention.

On examination, he was alert and appeared well. His heart rate was 45 beats per minute and regular, blood pressure 88/54 mmHg, capillary refill <2 s and temperature 36.8°C. There were no cardiac murmurs, and breath sounds were vesicular throughout. The abdomen was diffusely tender with no guarding or rebound; bowel sounds were normal and there was no organomegaly.

Investigations

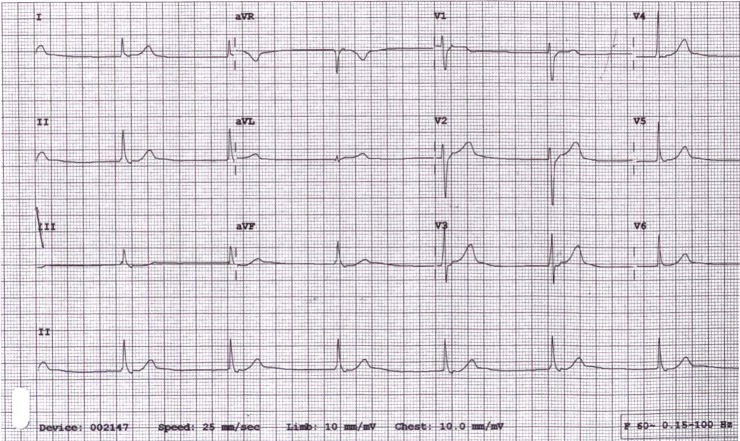

Electrocardiography showed a junctional bradycardia of 45/min with sinus node arrest and retrograde atrial depolarisation, normal axis, normal QRS morphology, normal QTc interval and no ischaemic changes (figure 1).

Figure 1.

ECG at presentation showing junctional bradycardia of 45/min with sinus node arrest and retrograde atrial depolarisation.

Serum levels of sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, calcium, phosphate, magnesium and C-reactive protein were within normal limits. The white cell count was 14.4×109/L and haemoglobin was 142 g/L.

The patient’s five family members were invited to attend the emergency department. All reported watery diarrhoea. A woman in her thirties reported headache, muscle weakness, a burning sensation in the limbs and the strange sensation of all her teeth being loose in her mouth. A man in his thirties reported a burning sensation in the hands and feet. All five had normal electrocardiograms.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of junctional bradycardia is broad. The most common causes are ischaemia of the atrioventricular node (usually in the setting of inferior myocardial infarction), electrolyte abnormalities and drug toxicity. Less common causes include myocarditis, infiltrative cardiac disease, acute rheumatic fever, infections (in particular diphtheria, Chagas disease and Lyme disease) and environmental toxins. Our patient gave no history of chest pain and there was no evidence of ischaemia on electrocardiography. Electrolytes were normal, and there was no history of drug exposure. Chagas and Lyme disease do not occur on the islands of the Caribbean, and there was neither fever nor pharyngitis to suggest diphtheria. The acute onset of diarrhoea after a meal suggested a food-related intoxication. Two seafood-related intoxications may cause prominent cardiovascular symptoms: neurotoxic shellfish poisoning and ciguatera.

Further history was obtained. The meal had consisted of a Great Barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda) bought from a street seller and cooked at home. No remnants of the fish were available for analysis. Shellfish had not been consumed.

The constellation of gastrointestinal, neurological and cardiovascular symptoms following consumption of a coral reef fish is highly suggestive of ciguatera; as no laboratory assay currently exists for ciguatoxins in human tissue samples, this remains a clinical diagnosis in the vast majority of cases.

Treatment

A clinical diagnosis of junctional bradycardia secondary to ciguatera intoxication was made, and the patient was admitted to the coronary care unit for observation and rehydration. He received 5000 mL intravenous crystalloid with potassium supplementation over the following 72 hours. During the first 48 hours, his heart rate varied from 45 to 80 beats per minute with periods of sinus bradycardia, junctional bradycardia and normal sinus rhythm. Blood pressure ranged from 100/55 to 120/70 mmHg. The patient maintained normal cognition, respiratory function and urine output, and did not require administration of atropine, vasopressors or inotropes.

Outcome and follow-up

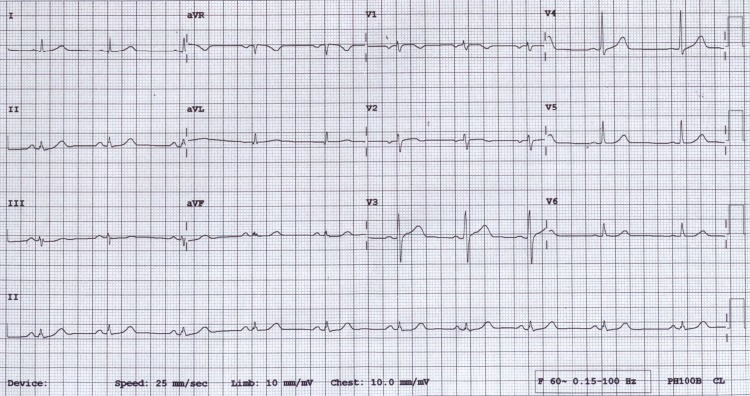

By day 3 of admission, persistent sinus rhythm was sustained at a rate of 66–68 beats per minute and he was discharged. At follow-up 5 months later, he remained asymptomatic. His ECG showed normal sinus rhythm at 60 beats per minute (figure 2).

Figure 2.

ECG at follow-up, showing normal sinus rhythm at 60/min.

Discussion

Ciguatera is a complex syndrome caused by large molecular weight polyether toxins synthesised by marine algae of the genus Gambierdiscus.1 2 The algae are consumed by herbivorous fish, which are in turn consumed by carnivorous fish. The toxins are modified and concentrated as they pass up the food chain,2 with the highest concentrations found in large predatory fish such as jacks and barracuda. Human consumption of these fish results in ciguatera intoxication. At least 12 different ciguatoxins have been characterised,1 with Pacific ciguatoxins showing significantly greater potency than Caribbean ciguatoxins.3

Symptoms of ciguatera begin 30 min to 24 hours after consumption of toxin-containing fish.1 2 A range of gastrointestinal, neurological and cardiovascular manifestations occur (table 1). Sensitisation is reported, whereby a second episode of poisoning is more severe than the first.3 In our case, this may explain the greater severity of symptoms following a second ingestion of barracuda.

Table 1.

Common symptoms of ciguatera intoxication1–3

| Gastrointestinal | Diarrhoea |

| Nausea and vomiting | |

| Abdominal pain | |

| Neurological | Paraesthesiae (limbs, perioral) |

| Dental symptoms (pain, ‘looseness’) | |

| Cold allodynia | |

| Pruritus | |

| Numbness | |

| Fatigue | |

| Myalgia | |

| Headache | |

| Cardiovascular | Bradycardia |

| Hypotension |

Ciguatoxins bind to voltage-gated sodium channels, triggering repetitive action potentials in nerve and muscle cells.1–3 This explains the positive neurological symptoms that are often reported. The principal cardiovascular manifestations of ciguatera are hypotension and sinus bradycardia. These are thought to occur due to excessive parasympathetic stimulation, hence responding well to treatment with atropine.4 5 Hypotension and bradycardia may be severe6 7 and can persist over several days. In the case described, we presume that profound parasympathetic stimulation resulted in sinus node arrest with high AV nodal block and junctional escape. Narrative reviews of ciguatera mention conduction abnormalities including atrioventricular blocks,3 but specific reports are lacking in the literature. To our knowledge, only one previous case of junctional bradycardia has been published.7 This was a case from Hong Kong, therefore presumed to be attributable to the more potent Pacific ciguatoxins.

Such guidelines as exist on ciguatera relate to fishing and processing practices aimed at preventing human cases, and there are at present no evidence-based guidelines on treatment. Aside from intravenous fluids, atropine is by far the most common treatment administered for the cardiovascular complications of ciguatera, and is sometimes required at high doses and for prolonged periods.8 Two small randomised controlled trials of intravenous mannitol5 9 reported conflicting results with regard to neurological symptoms, and no discernible effect on the cardiovascular sequelae of ciguatera. In the case presented, bradycardia was self-limiting and did not require specific therapy beyond the administration of intravenous fluids. The patient’s heart rate and blood pressure stabilised over a period of 2–3 days with complete resolution of electrocardiographic abnormalities, as would be expected for this temporarily incapacitating but generally self-limited illness.

With the documented spread of ciguatera beyond traditional endemic areas and sporadic cases appearing as far afield as Europe and North America, we suggest that generalist physicians should have some awareness of this unusual disease and of its rare but potentially serious cardiovascular manifestations.

Learning points.

Ciguatera is an environmental intoxication caused by consumption of coral reef fish, and is increasingly being reported beyond traditional endemic areas.

The combination of gastrointestinal, neurological or cardiovascular symptoms with a history of coral reef fish consumption should suggest the diagnosis of ciguatera.

Bradycardias can occur as part of ciguatera intoxication, but are rare. Other causes of bradycardias including ischaemia, electrolyte abnormalities and drug toxicity should be excluded. Management is supportive and includes administration of atropine and intravenous fluid in cases of bradycardia associated with cardiovascular compromise.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr William Jenkins for valuable comments on the manuscript, and Captain Paul Bracken for providing an excellent introduction to ciguatera in the Caribbean region. The comments of our anonymous reviewer were gratefully received and incorporated into the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: RR, SC and TH initially assessed and managed the patient in the emergency department. CL was the consultant who admitted and managed the patient in the coronary care unit and arranged subsequent follow-up. RR conceived the case report and wrote the clinical history and background. SC reviewed and summarised the literature on ciguatera presentation, and commented on other sections. TH reviewed and summarised the literature on management, and commented on other sections. CL oversaw the writing of the report and made comments on each section, all of which were incorporated in the final report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Heimann K, Sparrow L. Ciguatera: tropical reef fish poisoning Kim S-K, Handbook of marine microalgae. London: Elsevier, 2015:547–58. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedman MA, Fernandez M, Backer LC, et al. An updated review of ciguatera fish poisoning: clinical, epidemiological, environmental, and public health management. Mar Drugs 2017;15:72 10.3390/md15030072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pottier I, Vernoux JP, Lewis RJ. Ciguatera fish poisoning in the Caribbean islands and Western Atlantic. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2001;168:99–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Geller RJ, Benowitz NL. Orthostatic hypotension in ciguatera fish poisoning. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:2131–3. 10.1001/archinte.1992.00400220135023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schnorf H, Taurarii M, Cundy T. Ciguatera fish poisoning: a double-blind randomized trial of mannitol therapy. Neurology 2002;58:873–80. 10.1212/WNL.58.6.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan TY. Severe bradycardia and prolonged hypotension in ciguatera. Singapore Med J 2013;54:e120–e122. 10.11622/smedj.2013095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chan TY. Epidemiology and clinical features of ciguatera fish poisoning in Hong Kong. Toxins 2014;6:2989–97. 10.3390/toxins6102989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Senthilkumaran S, Meenakshisundaram R, Michaels AD, et al. Cardiovascular complications in ciguatera fish poisoning: a wake-up call. Heart Views 2011;12:166–8. 10.4103/1995-705X.90905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bagnis R, Spiegel A, Boutin JP, et al. [Evaluation of the efficacy of mannitol in the treatment of ciguatera in French Polynesia]. Med Trop 1992;52:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]