Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, have significantly improved cancer patient outcome. Toxicities are usually moderate and manageable. However, some adverse events, if not early recognised, could be life-threatening. We report a patient with non-small cell lung cancer who received treatment with pembrolizumab and developed multiple immune-related adverse events both during and after completing treatment, including rash, pericarditis, colitis and myasthenia gravis.

Keywords: pericardial disease, gastrointestinal system, immunological products and vaccines, neuromuscular disease, lung cancer (oncology)

Background

Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) is an inhibitory receptor expressed on the surface of activated T cells. The binding of PD-1 to its ligand (PD-L1), which is expressed on the surface of antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, transmits an inhibitory signal into T cells, reducing cytokine production and suppressing T-cell proliferation. Multiple cancer cells highly express PD-L1 on their surface, allowing mechanism to escape immune system. Pembrolizumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor. By inhibiting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, this antibody may enable the activation of T cells, restoring their ability to efficiently detect and attack tumour cells.1 However, although better tolerated and with less adverse events (AEs) than classical chemotherapeutic agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been reported to induce severe and potentially life-threatening immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

The most frequent include rash, colitis, pneumonitis, hepatitis and endocrinopathy.2 We report the case of a patient who presented with multiple irAEs both during and after pembrolizumab treatment. This highlights the importance to closely follow our patients during ICI administration.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-woman was treated with pembrolizumab for lung cancer. Her medical history included asthma and hypertension. In 2015, a lobectomy was performed for an adenocarcinoma of the lung, classified pT1a pN1 M0. There was no adjuvant treatment. In 2016, mediastinal lymph nodes appeared and biopsy, through endobronchoscopy ultrasonography (US), confirmed resurgence of the disease with a high PD-L1 expression (100% at immunohistochemistry). Pembrolizumab was therefore initiated at standard dose (200 mg every 3 weeks).

One week after the first administration, she developed a grade 2 rash (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5), appearing as erythematous macules and patches recovering 20% of body with pruritus. These lesions were predominantly localised to the extremities (lower>upper) (figure 1). There was no vitiligo. At the time of eruption, haemogram was normal, as well as eosinophil counts. There was no sign of infection. This rash was well controlled with the association of oral antihistaminic and topical corticosteroids and decreased to grade 1 progressively, without disappearing and an oral antihistaminic was continuously taken by the patient.

Figure 1.

Grade 2 rash occurring in the first 2 weeks of pembrolizumab initiation.

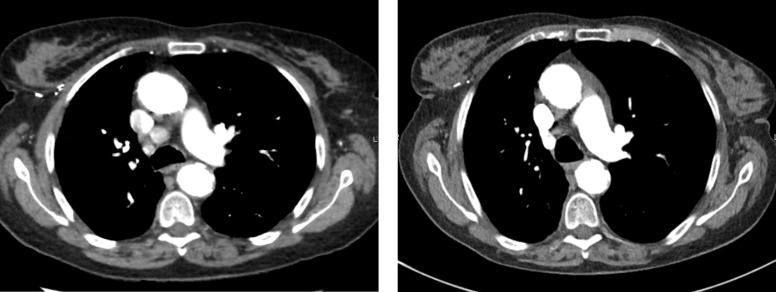

One week after the third infusion (week 10 after treatment initiation), the patient described brutal apparition of isolated thoracic pain, increasing when leaning. Clinical examination was normal; there was no hepato-jugular reflux, no abnormal cardiac sound. In biology, haemogram, electrolytes, renal and liver tests were within normal range, as well as some cardiac specific tests such as creatine kinase phosphate and troponine. There was aspecific repolarisation anomaly on EKG. Thoracic CT scan excluded pulmonary embolism and pleural effusion but detected pericardial effusion; mediastinal lymph nodes had completely disappeared (figure 2). A cardiac US confirmed a pericardial effusion of 8 mm without any haemodynamic repercussion. There was no history or clinical sign of viral infection. Methylprednisolone 16 mg once a day reversed completely the symptom after 48 hours; after 7 days, pericardical effusion had completely disappeared and corticosteroids were stopped. Pembrolizumab was reintroduced 3 weeks later with close cardiac follow-up (cardiac US every 2 weeks) and no resurgence.

Figure 2.

Mediastinal tumour lymph nodes before pembrolizumab (left) and at 3 months of pembrolizumab treatment (right).

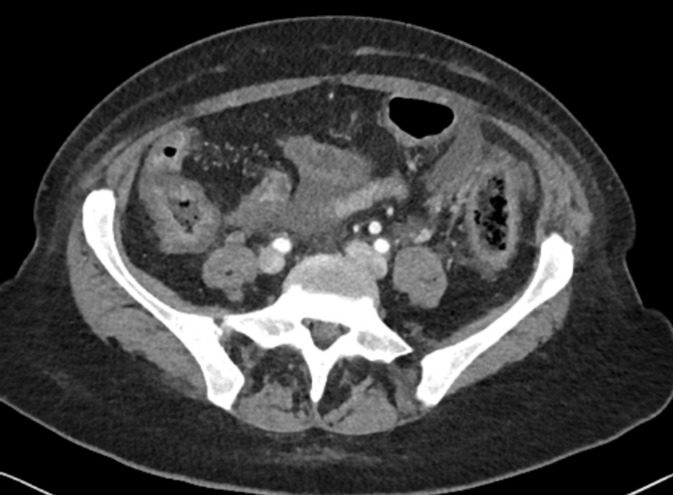

After the sixth injection (week 22 after treatment initiation), grade 3 diarrhoea (>8 stools/day) occurred, without any abdominal pain, bloody stools, fever or clinical dehydration. There was no biological sign of infection and coprocultures were negative. Abdominal CT scan did not demonstrate any ischaemic sign but a diffuse colitis pattern with thickness of colon wall (figure 3). Intravenous methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg daily was rapidly initiated and diarrhoea stopped after 24 hours. As symptoms disappeared rapidly with corticosteroids, colonoscopy was not performed. As thoraco-abdominal CT scan confirmed a complete oncological response, pembrolizumab was stopped definitely and corticosteroids were tapered in 3 weeks.

Figure 3.

Colitis pattern at abdominal CT scan.

Three months after pembrolizumab arrest, she was admitted for general weakness. Fatigue was present at rest, and increased at mild exercise, at speaking and eating. Clinical examination showed bilateral ptosis and dysarthria, as well as a proximal weakness; strength loss was evaluated at 3/5 following the manual muscle testing grading system. Biology was normal, including endocrine tests (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH), T4 and cortisolaemia) as well as creatinine phosphokinase and lactate dehydrogenase. Electromyography showed a positive decrement reflecting a neuromuscular junction trouble that suggested diagnosis of myasthenia gravis (MG). Auto-antibodies against acetylcholine receptor, Hu, Ri, Yo, Ma2/Ta, CV2, amphiphysin, recoverin, SOX 1, titin, Zic4 and Tr were all negative. Cerebral MRI was normal and thoraco-abdominal CT demonstrated persistence of oncologic complete remission. Oral pyridostigmine (30 mg, five times daily) was started; after 7 days, due to deterioration of strength loss (evaluated at 2/5), pyridostigmine was increased (60 mg, five times daily) in association with intravenous methylprednisolone (80 mg daily). Neurological symptoms deteriorated with increasing muscle weakness, including respiratory muscles that resulted in breathlessness at rest. Five courses of plasmapheresis were administered with rapid clinical improvement within 3 days.

Outcome and Follow-up

Three months after the plasmapheresis (6 months after ceasing pembrolizumab), the irAEs had completely resolved and the patient remained physically well without corticosteroids. Six months later, our patient remains alive and CT scans demonstrate persistence of complete oncological response to treatment. She remains on pyridostigmine which we plan to progressively taper. She also remains on an antihistaminic as the pruritus has not completely resolved.

Discussion

We report multiple irAEs occurring sequentially in a patient, even after the stopping of pembrolizumab.

The first AE reported in our patient was skin toxicity, which is a well known irAE observed with ICIs. Skin toxicity is usually one of the first AEs reported with ICIs, developing early in the course of treatment, within the first few weeks after initiation. Low grade (1–2) rash is reported in around 15% whereas grade 3-4 rashes are rare, with an incidence of less than 3%. Pruritus is reported in 20% of patients treated with pembrolizumab but reaches a grade 3 and 4 in only <2.5%.3 In our patient, rash appeared within the first 2 weeks of pembrolizumab onset and did not really disappear, even after treatment interruption, suggesting a sustained immunologic stimulation in this patient. Systemic corticosteroids were not started in the absence of grade 3 AE, according to American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines.4

Pericarditis occurred also rapidly in the pembrolizumab course. Cardiac disorders related to ICIs are rare (around 1%–2%) and include pericarditis, myocarditis and cardiomyopathy; they are reported to occur between 2 and 17 weeks after treatment onset.5 6 In our patient, we assumed that pericarditis was induced by pembrolizumab due to the close time relationship with its initiation, the absence of other aetiology and the rapid and complete reversal of symptoms with methylprednisolone. Even if ASCO guidelines recommend to permanently discontinue ICIs after cardiac G1 AEs, this recommendation is based on anecdotal evidence.4 As there was no haemodynamic repercussion and a rapid complete resolution of symptoms, we continue pembrolizumab with a frequent cardiac control.

Diarrhoea occurs in 20% of patients treated with ICIs but only 2% of patients present with grade 3–4 colitis.7 The median time to onset of diarrhoea is usually 3–6 months for anti-PD-1 such as pembrolizumab, which was consistent with our patient case.8 In our patient, colitis was suspected to be immune-related due to absence of other identified cause and rapid improvement on corticosteroid. We decided to not perform colonoscopy in our patient; corticosteroids had already been started for several days, symptoms had completely disappeared and this endoscopic technic would not have changed our management. Furthermore, it has been shown that endoscopic and histopathological features had no association with different types of ICIs.8 In our patient, the severity of the colitis, particularly in a context of complete remission, led us to stop definitely pembrolizumab.

ASCO guidelines recommend a corticosteroid duration of 2–4 weeks for moderate (grade 2) irAEs and 4–8 weeks for severe (grade 3–4) irAEs. Corticosteroids were tapered probably too quickly in our patient, in less than 1 month for pericarditis and colitis. It could be hypothesised that a longer duration of corticosteroids for these toxicities could have prevented subsequent IrAEs, but it still remains unknown.4

MG is very rarely described with ICIs; to date, pembrolizumab has been associated with very few de novo MG presentation, meaning that this irAE is very rare or may be underdiagnosed.9–16 MG appears usually rapidly after the initiation of pembrolizumab, within the first weeks to first months.9–16 However, in our patient, MG occurred up to 3 months after the stopping of pembrolizumab, which was not yet reported. The hypothesis of an immune-related aetiology is supported by the absence of predisposing other factors such as thymoma and by the complete remission of cancer that excludes a paraneoplastic syndrome. Even if antibodies are frequently observed in MG, up to 20% of immune-related MG are seronegative, as observed in our patient.17 Prognosis of these patients remains poor with a 30% of MG-specific-related mortality described in some reviews.10 11 16 In our case, pyridostigmine insufficiently reversed MG evolution and plasmapheresis was thus initiated with successful outcome.

Our case is interesting for different reasons. This is the first time that so many serious AEs are described in a patient treated with pembrolizumab, reflecting the importance to closely follow our patients during the ICI treatment. Occurrence of one irAE could suggest a high sensitivity to develop new irAEs and any complaint should be suspected to be immune related. It is unclear why some patients develop irAEs and others do not. To date, no association was found between one specific genotype (Human Leukocyte Antigen A (HLA-A status) and the risk of irAEs. In addition to genetic factors, some investigations have asked whether the microbiologic composition of a patient’s gastrointestinal flora is related to the development of irAE.18–24

The second important point is that severe AEs can appear several months after the interruption of ICI, which is very rarely described. However, irAEs can be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed after the stopping of ICI due to evolution of cancer or initiation of a new cytotoxic therapy that can mimic toxicity related to previous ICI. As ICIs are more and more evaluated in adjuvant setting for a limited duration, it is important to carefully follow our patients, even after the interruption of the treatment.

Third, pembrolizumab resulted in our patient in a complete and long-lasting remission; whether there is an association between incidence of irAEs and ICI efficacy remains unclear but some retrospective and prospective reports describe a potential positive association.25–27 In a small cohort (43 patients treated with nivolumab), the objective response and disease control rates were higher in patients with irAEs than in those without irAEs. Furthermore, they showed that early irAEs (occurring within the first 2 weeks) were strongly associated with better patient outcome.27 Even if this requires further confirmation, it is interesting to note that in our rapidly responding patient, the first irAE occurred within the first 2 weeks of pembrolizumab administration and that the delayed apparition of MG could also reflect a residual hyperactivity of the immune system that results in the continuous control of the cancer we observe. Finally, corticosteroids should be tapered very progressively, in order to reduce the chance of irAEs relapsing.

Patient’s perspective.

Pembrolizumab gave me a complete response but also gave me some toxicities. These toxicities are sometimes difficult to explain and all complaint should be explored in order to exclude adverse event related to immunotherapy.

Learning points.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) improve considerably patient outcome but can can cause immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Cascade of multiple irAEs can occur in one patient, even after the ICI interruption.

Patient who presented a first irAE should be closely followed and any complaint should be suspected to be immune related.

Corticosteroids should be tapered progressively, with a recommended corticosteroid duration of 2–4 weeks for moderate irAEs and 6–8 weeks for severe irAEs in order to reduce the risk of irAEs relapsing.

Footnotes

Contributors: AD reported the case and wrote the manuscript. VS and SL wrote and revised the manuscript. ES planned, reported, wrote and revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Swaika A, Hammond WA, Joseph RW. Current state of anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 agents in cancer therapy. Mol Immunol 2015;67:4–17. 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018;360:k793 10.1136/bmj.k793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boutros C, Tarhini A, Routier E, et al. Safety profiles of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone and in combination. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:473–86. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1714–68. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang DY, Okoye GD, Neilan TG, et al. Cardiovascular Toxicities Associated with Cancer Immunotherapies. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017;19:21 10.1007/s11886-017-0835-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oristrell G, Bañeras J, Ros J, et al. Cardiac tamponade and adrenal insufficiency due to pembrolizumab: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2018;2:1–5. 10.1093/ehjcr/yty038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang DY, Ye F, Zhao S, et al. Incidence of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis in solid tumor patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology 2017;6:e1344805 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1344805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Geukes Foppen MH, Rozeman EA, van Wilpe S, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000278 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zimmer L, Goldinger SM, Hofmann L, et al. Neurological, respiratory, musculoskeletal, cardiac and ocular side-effects of anti-PD-1 therapy. Eur J Cancer 2016;60:210–25. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. March KL, Samarin MJ, Sodhi A, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced myasthenia gravis: A fatal case report. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2018;24:146–9. 10.1177/1078155216687389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gonzalez NL, Puwanant A, Lu A, et al. Myasthenia triggered by immune checkpoint inhibitors: New case and literature review. Neuromuscul Disord 2017;27:266–8. 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nguyen BH, Kuo J, Budiman A, et al. Two cases of clinical myasthenia gravis associated with pembrolizumab use in responding melanoma patients. Melanoma Res 2017;27:152–4. 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alnahhas I, Wong J. A case of new-onset antibody-positive myasthenia gravis in a patient treated with pembrolizumab for melanoma. Muscle Nerve 2017;55:E25–E26. 10.1002/mus.25496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huh SY, Shin SH, Kim MK, et al. Emergence of Myasthenia Gravis with Myositis in a Patient Treated with Pembrolizumab for Thymic Cancer. J Clin Neurol 2018;14:115–7. 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.1.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hibino M, Maeda K, Horiuchi S, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced myasthenia gravis with myositis in a patient with lung cancer. Respirol Case Rep 2018;6:e00355 10.1002/rcr2.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makarious D, Horwood K, Coward JIG. Myasthenia gravis: An emerging toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer 2017;82:128–36. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suzuki S, Ishikawa N, Konoeda F, et al. Nivolumab-related myasthenia gravis with myositis and myocarditis in Japan. Neurology 2017;89:1127–34. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Hamid O, et al. Ipilimumab efficacy and safety in patients with advanced melanoma: a retrospective analysis of HLA subtype from four trials. Cancer Immun 2010;10:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vétizou M, Pitt JM, Daillère R, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015;350:1079–84. 10.1126/science.aad1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015;350:1084–9. 10.1126/science.aac4255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubin K, Callahan MK, Ren B, et al. Intestinal microbiome analyses identify melanoma patients at risk for checkpoint-blockade-induced colitis. Nat Commun 2016;7:10391 10.1038/ncomms10391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Champiat S, Lambotte O, Barreau E, et al. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann Oncol 2016;27:559–74. 10.1093/annonc/mdv623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schindler K, Harmankaya K, Kuk D, et al. Correlation of absolute and relative eosinophil counts with immune-related adverse events in melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 2014;32(15_suppl):9096 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.9096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tarhini AA, Zahoor H, Lin Y, et al. Baseline circulating IL-17 predicts toxicity while TGF-β1 and IL-10 are prognostic of relapse in ipilimumab neoadjuvant therapy of melanoma. J Immunother Cancer 2015;3:39 10.1186/s40425-015-0081-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hasan Ali O, Diem S, Markert E, et al. Characterization of nivolumab-associated skin reactions in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1231292 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1231292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Osorio JC, Ni A, Chaft JE, et al. Antibody-mediated thyroid dysfunction during T-cell checkpoint blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2017;28:583–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdw640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Teraoka S, Fujimoto D, Morimoto T, et al. Early Immune-Related Adverse Events and Association with Outcome in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Nivolumab: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:1798–805. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]