Abstract

Ileosigmoid knotting (ISK) is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction rapidly progressing to bowel gangrene. It is characterised by the wrapping of loops of ileum and sigmoid colon around each other. The condition often remains undiagnosed preoperatively; however, it can be suspected by the triad of small bowel obstruction, radiographic features suggestive of predominately large bowel obstruction and inability to deflate the intestine by a sigmoidoscope. We are reporting a case of 56-year-old man who presented with features of acute intestinal obstruction and compensated shock within 24 hours of onset of symptoms. Exploratory laparotomy revealed ISK resulting in gangrene of ileum and sigmoid colon. In view of haemodynamic instability, end ileostomy was done after excising gangrenous segments. The patient improved and stoma closure and ileocolic anastomosis were done after 3 months in follow-up.

Keywords: gastrointestinal system, emergency medicine, general surgery

Background

Ileosigmoid knotting (ISK), also known as compound volvulus or double volvulus, is a rare cause of acute intestinal obstruction.1 It is the result of the ileum wrapping around the base of sigmoid colon forming a knot, predisposing ileum as well as sigmoid colon to become gangrenous.2 ISK is a diagnostic challenge and timely suspicion and intervention are crucial to prevent morbidity and mortality. We are reporting this case due to its rare presentation and challenges faced during its management.

Case presentation

A 56-year-old man presented with acute onset colicky abdominal pain, distension, vomiting and obstipation for 1 day. General examination showed tachycardia with normal blood pressure and pallor. The abdomen was tense, distended and tender with guarding and rigidity. Organomegaly could not be examined due to tenderness. Cough impulse on all the potential hernia orifices was negative. Digital rectal examination revealed an empty rectum. Bowel sounds were absent.

Investigations

Blood investigations revealed a total blood count of 15.2×103/µL with neutrophil 76%, haemoglobin level 13.6 g/dL and platelet count 217×103/µL. Renal function tests results showed sodium of 136 mmol/L, potassium of 4.5 mmol/L, chloride 104 mmol/ L, urea of 28 mg/dL and creatinine of 0.8 mg/dL. Abdominal X-ray showed gaseous distension of large bowel with no pneumoperitoneum. CT scan could not be done as the patient was unstable.

Treatment

In view of the possibility of acute large bowel obstruction with the possibility of perforation with compensated shock, laparotomy was planned after fluid resuscitation guided by central venous pressure. On surgical exploration, knotting of the sigmoid colon by the ileum with gangrene of ileum, ileocaecal junction and sigmoid colon was found (figures 1 and 2). Resection of gangrenous bowel was done followed by an end-to-end anastomosis of the sigmoid colon and end ileostomy. We chose to perform terminal ileostomy instead of ileocolic anastomosis with lateral loop ileostomy which is the more widely used procedure because in this case, ileum including ileocaecal junction was gangrenous and had to be resected. Moreover, the patient was haemodynamically unstable. He developed secondary chest infection on postoperative day 3. So he was shifted and managed in the intensive care unit for a week. Also, he developed high output stoma, which was managed conservatively along with total parenteral nutrition.

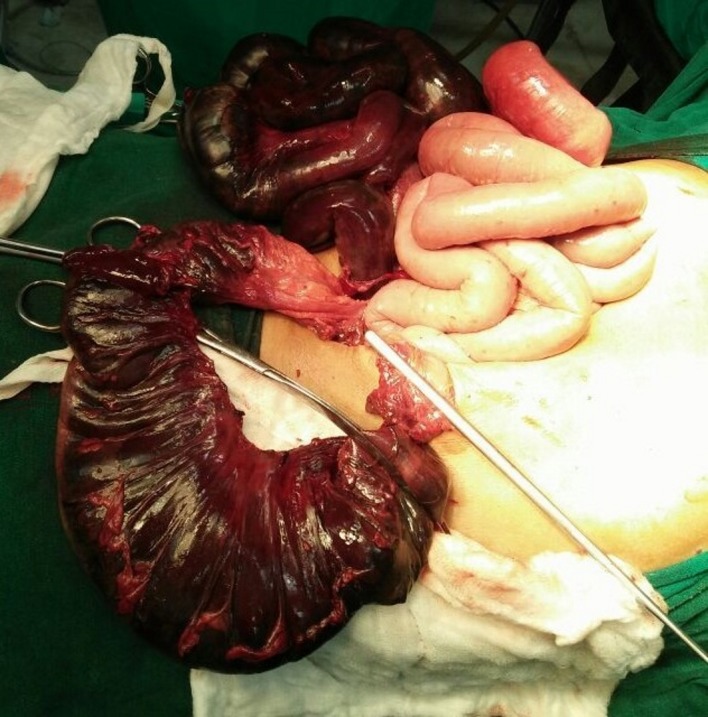

Figure 1.

Intraoperative findings of gangrenous ileum and sigmoid colon in a case of ileosigmoid knotting.

Figure 2.

Gangrenous ileum and sigmoid colon seen along with viable loops of jejunum.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged after 3 weeks of hospitalisation. He remained well in follow-up; ileostomy closure and ileocolic anastomosis were done after 3 months when stoma output got normalised.

Discussion

ISK results from the wrapping of the base of the sigmoid colon by the ileum. The exact incidence of ISK is not known, but it is high in African, Asian, Middle Eastern, South American and Eastern and Northern European countries.1 It predominantly affects men with peak incidence during the third to fifth decade of life and pregnant women.1 3 ISK contributes to 18%–50% of sigmoid volvulus cases in Eastern countries and only 5%–8% in the Western world.2

Three factors implicated in the pathophysiology of ISK are a long sigmoid colon, freely movable small bowel and consumption of a bulky vegetarian diet in the presence of an empty small bowel.4 Other predisposing factors are late pregnancy, transmesenteric herniation, Meckel diverticulitis with a band, ileoceacal intussusception and floating caecum.5

ISK has been broadly categorised into three types. Type 1 is characterised by the wrapping of the sigmoid colon base by ileum as active component either in clockwise (type 1A) or anticlockwise direction (type 1B). In type 2, sigmoid colon is the active component wrapping around the ileal base. Type 2A results from sigmoid colon wrapping the ileal base in a clockwise direction and counter-clockwise version of type 2A is type 2B. In type 3, ileoceacal segment wraps itself around the sigmoid colon. The most common variant is type 1 (53.9%–57.5%), followed by type 2 (18.9%–20.6%) with type 3 (1.5%) being the least frequent. Bowel twists in the clockwise direction in 60.9%–63.2% of cases.5 6 In the present case, we encountered type 1B knot with two 360° turns of the ileum over the sigmoid colon.

ISK presents an acute abdominal event with an average duration of symptoms being 46.5 hours.7 Clinical features include colicky abdominal pain with tenderness (100.0%), obstipation (100.0%), asymmetrical abdominal distention (27.3%–100.0%), vomiting (83.6%–100.0%), rebound tenderness (36.8%–50.8%), melanotic stools (14.3%–16.4%) and decreased or exaggerated bowel sounds in 25.0%–27.4% and 64.4%–65.6% of the cases, respectively.7 Overall gangrene complicates 73.5%–79.4% cases and both ileum and sigmoid colon are gangrenous in 52.9%–60.3% of the patients. Gangrene is paradoxically more common in the cases presenting within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms probably indicating more severe nature of the disease among patients manifesting early.6 8 Preoperative diagnosis of ISK is difficult as clinical features like vomiting suggest small bowel obstruction, but radiographic findings resemble colonic obstruction. Diagnostic triad providing a clue to ISK includes a clinical picture of small bowel obstruction, radiographic evidence of predominately large bowel obstruction and inability to deflate the bowel by a sigmoidoscope.9 Typical radiographic findings of ISK are dilated double loop of sigmoid, medially deviated and distended descending colon and multiple dilated loops of the small intestine, but it is seldom noticed because of the rarity of the condition.1

CT scan is an emerging tool for the diagnosis of ISK. The characteristic signs on CT scan include ‘whirl sign’ created by twisted mesocolon, mesenteric vessels and intestines. CT also reveals medial deviation of descending colon with the pointed appearance of its medial border caused by traction on the peritoneum of left paracolic gutter and interposition of ileal loops between descending and proximal sigmoid colon and left body wall. Caecum may deviate medially with the pointed appearance of its medial border.10

Initial management of ISK includes judicious fluid resuscitation, antibiotics and correction of acid–base and fluid electrolyte imbalance. Combinations of surgical procedures have been described in the literature for the management of ISK but most widely performed surgery is ileal resection +primary anastomosis+sigmoid colon resection +Hartmann’s procedure/colostomy. Type of procedure is guided by bowel viability. If both the loops or only ileum is viable but sigmoid colon is gangrenous, the knot is relieved by sigmoid colon enterotomy and resection of the sigmoid colon loop. In case of gangrene of the ileal loops, intestinal clamps are applied before resection of the knot followed by resection of both the loops. Primary anastomosis is done unless terminal ileum is gangrenous within 10 cm of the ileoceacal valve.5 Our patient had gangrene of both the loops including ileoceacal junction. In view of haemodynamic instability, resection of the gangrenous bowel was done along with the end-to-end sigmoid colon anastomosis and end ileostomy. The average mortality rate of ISK is 0%–47% with the most common cause of death being septic shock leading to multiple organ failure. Factors associated with mortality include age (>60 years), duration of symptoms (>24 hours since the onset of symptoms) and the extent of gangrene.11 Atamanalp et al proposed a new classification system for ISK based on patient’s age >60 years, the presence of associated disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiac failure, coronary disease, diabetes mellitus and so on), shock and gangrene with treatment option and associated mortality for each class.12

Learning points.

Ileosigmoid knotting is a rare and life-threatening cause of intestinal obstruction.

Diagnosis can be expedited by the triad of the clinical picture of small bowel obstruction, radiographic features suggestive of predominately large bowel obstruction and inability to deflate the bowel by sigmoidoscope and CT scan.

Aggressive fluid resuscitation and prompt surgical intervention are critical to improving the outcome.

Footnotes

Contributors: BKS and RK: collected the clinical details and photographs of the patient’s report. PKSK, RK, KM and BKS: clinical management. BKS and PKSK: performed the literature review and drafted the initial manuscript. KM and RK: verified the diagnosis and other scientific facts. KM and RK: revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. No grant was received for this report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Correct

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Atamanalp SS, Oren D, Başoğlu M, et al. Ileosigmoidal knotting: outcome in 63 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:906–10. 10.1007/s10350-004-0528-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Machado NO. Ileosigmoid knot: a case report and literature review of 280 cases. Ann Saudi Med 2009. 29:402–6. 10.4103/0256-4947.55173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atamanalp SS. Ileosigmoid knotting in pregnancy, Turk. J Med Sci 2012;42:553–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaez-Zadeh K, Dutz W. Ileosigmoid knotting. Ann Surg 1970;172:1027–33. 10.1097/00000658-197012000-00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mandal A, Chandel V, Baig S. Ileosigmoid knot. Indian J Surg 2012;74:136–42. 10.1007/s12262-011-0346-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alver O, Oren D, Tireli M, et al. Ileosigmoid knotting in Turkey. Review of 68 cases. Dis Colon Rectum 1993;36:1139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Atamanalp SS. Ileosigmoid knotting: clinical appearance of 73 cases over 45.5 years. ANZ J Surg 2013;83:70–3. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shepherd JJ. Ninety-two cases of ileosigmoid knotting in Uganda. Br J Surg 1967;54:561–6. 10.1002/bjs.1800540615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raveenthiran V. The ileosigmoid knot: new observations and changing trends. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1196–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee SH, Park YH, Won YS. The ileosigmoid knot: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:685–7. 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mallick IH, Winslet MC. Ileosigmoid knotting. Colorectal Dis 2004;6:220–5. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atamanalp SS, Ozturk G, Aydinli B, et al. A new classification for ileosigmoid knotting. Turk J Med Sci 2009;39:541–5. [Google Scholar]