Abstract

Kabuki syndrome (KS) is a multiple congenital anomaly syndrome with diversified ophthalmological manifestations. We report a case of a boy with bilateral features of Salzmann nodular degeneration (SND) associated with KS. An 18-year-old Caucasian man with KS presented for a second opinion regarding incapacitating photophobia in his right eye, refractory to medical therapy. Biomicroscopy revealed bilateral subepithelial nodules in the midperiphery of the cornea, less extensive in the left eye, consistent with SND. Symptomatic improvement was achieved after superficial keratectomy, manually performed with a blade and adjuvant application of mitomycin C. We report a rare case of a KS patient with SND. Since KS manifestations may vary widely, it is important to perform an early ophthalmological examination for prompt detection and treatment of ocular abnormalities and thus improve life quality in these patients.

Keywords: eye, genetics, ophthalmology, anterior chamber, congenital disorders

Background

Kabuki syndrome (KS), also known as Kabuki make-up syndrome or Niikawa-Kuroki syndrome, is a rare disease with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 32 000 births in Japan.1 It was first described by two groups in 19812 3 and is one of the most common causes of genetic developmental delay. A wide genetic heterogeneity of the disease has been demonstrated. Some authors describe cytogenetic abnormalities that involve the X chromosome,4 5 although many believe that most occurrences are either first-time or sporadic mutations, without sex predilection.1 6–8 In a recently published series, de novo or autosomal dominant mutations in KMT2D, also known as MLL2 (OMIM#602113), were identified as a major genetic cause of KS, with a prevalence that can be as high as 76%.7–14 Up to 5% of cases seem to be caused by KDM6A mutations, as reported previously.8 9

The clinical variability is extensive, usually comprising: (1) characteristic facial features, namely eversion of the lower lateral eyelid, arched eyebrows with the lateral third sparse, depressed nasal tip and prominent ears, presenting in almost 100% of cases; (2) skeletal abnormalities; (3) dermatoglyphic abnormalities such as fingertip pads, absence of digital triradius and increased digital ulnar loop; (4) intellectual disability of variable degree and (5) short stature.6 9 15 16 Other features can include hypodontia, congenital heart defects, renourinary malformations, recurrent infections, micrognathia, cleft/highly arched palate, obesity and deafness.17

The reported prevalence of ophthalmological abnormalities in KS is around 38%–61%, although severe visual impairment is rare.6 18 It most often includes strabismus, ptosis and retina coloboma, with reported prevalence of 20.5%, 14.4% and 3.2%, respectively. Blue sclera, coloboma of the iris, refractive anomalies, cataracts, nystagmus, Peter’s anomaly, congenital corneal staphyloma, optic nerve hypoplasia, microphthalmos, microcornea, megalocornea, palsy of the third cranial nerve, Marcus Gunn’s phenomenon and retinal telangiectasia have also been described.14 15 18–23

Salzmann nodular degeneration (SND) is a non-inflammatory progressive corneal degenerative condition, characterised by elevated, single or multiple whitish-grey subepithelial nodules, commonly in the midperiphery of the cornea, in a circumferential configuration.24 25 It is more prevalent in females and in the sixth decade of life, although it can appear at any age and frequently has bilateral involvement.24 26 Clinical symptoms may vary from asymptomatic to decreased visual acuity, irregular astigmatism, hyperopia, glare, foreign body sensation, severe pain and photophobia.24 25 The exact aetiology is not known but evidence points to it being triggered by chronic ocular surface inflammation.24 27 28

We describe a case of a patients with KS who presented with bilateral whitish-grey subepithelial nodules in the midperipheral cornea with a circumferential configuration, consistent with SND. To our knowledge, there is only one similar case described in the literature.29

Case presentation

A 18-year-old Caucasian man with KS was admitted to the ophthalmology department for a second opinion, regarding subepithelial nodules in the midperiphery of the cornea in the right eye that induced severe photophobia that was refractory to ocular lubrication, eyelid hygiene and topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment. The lesions were also observed to a lesser extent in his left eye and were consistent with SND. He had been having successive follow-ups in our paediatric ophthalmology department since he was 3 years old. His clinical record reported bilateral corneal subepithelial nodules, horizontal nystagmus, pulverulent cataract and unremarkable funduscopy. His visual acuity was 20/80 in his right eye and 20/63 in his left eye, with hyperopic correction lenses. External ophthalmic examination revealed arched eyebrows, eversion of the lateral portion of the lower eyelids, prominent eyelashes and long palpebral fissures. The patient also presented with peculiar facial features, namely a depressed nasal tip and low-set deformed ears, as well as fingertip pads and short stature (figure 1). Other congenital malformations were also present, including a large ventricular septal defect, hypospadias, cryptorchidism and a single umbilical artery.

Figure 1.

External photograph showing arched eyebrows, long palpebral fissures, a nasal tip and low-set ears.

Family history was unremarkable with respect to consanguinity, intellectual disability and peculiar facies. Chromosomal studies showed a normal 46XY pattern, and the MLL2 gene mutation was not detected.

Investigations

The patient was examined by slit-lamp biomicroscopy, anterior segment photography (figure 2), corneal topography and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), performed with Spectralis anterior segment module (Heidelberg Engineering, Germany). AS-OCT showed prominent bright subepithelial deposits in the cornea, leading to localised elevation of the anterior corneal surface and epithelial thinning. The posterior stroma and the Descemet membrane were unremarkable (figure 3).

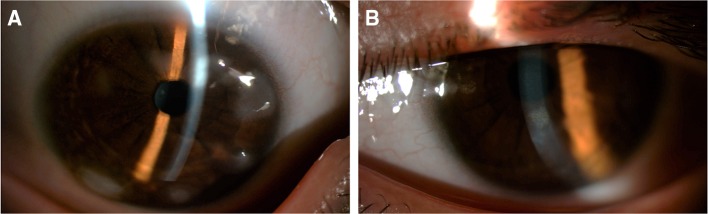

Figure 2.

Anterior segment photos showing subepithelial nodules in the mid periphery of the cornea in the right eye (A) and, to a lesser extent, in the left eye (B).

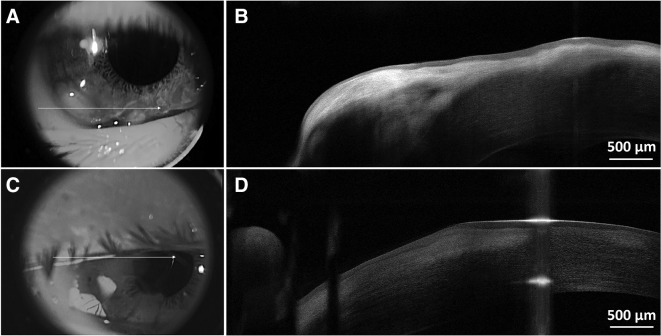

Figure 3.

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography showing prominent bright subepithelial deposits in the cornea, the anterior corneal surface elevation and epithelial thinning in these locations, in the right eye (A and B) and in the left eye (C and D).

Differential diagnosis

The bilateral subepithelial corneal opacifications and their circumferential configuration observed in our patient are consistent with the diagnosis of SND. Because the gender and age are not characteristic of SND, other entities should be considered. Peripheral hypertrophic subepithelial corneal degeneration should also be suspected since it is characterised by subepithelial areas of opacification, often bilateral. However, it predominates in elderly women.30 Spheroidal degeneration (also known as climatic droplet keratopathy) is unlikely, since in this entity corneal deposits are homogeneous, translucent, yellowish gold, have an interpalpebral distribution and are located in the corneal stroma and Bowman membrane, rather than in the epithelium.31 Furthermore, it is more common in tropical areas, with high exposure to ultraviolet radiation.31 32

Treatment

Since there was exacerbation of the right photophobia, despite conservative therapy, we performed superficial keratectomy with a scalpel blade No° 15 and adjuvant application of mitomycin C for 30 s.

Outcome and follow-up

In the postoperative period, topical fluorometholone 0.1% three times a day, cyclosporine 1% twice a day and artificial tears were prescribed. One month after surgery, the patient reported great improvement of photophobia, without changes in visual acuity or refraction. After 8-month follow-up, the patient mentioned less photophobia and had slight improvement in visual acuity of his right eye to 20/50. Subepithelial nodules were less elevated at biomicroscopy. Currently, he is on topical cyclosporine 0.05% twice a day and artificial tears once a day, bilaterally.

Discussion

KS is a multisystem congenital disorder with a wide genetic heterogeneity.1 4 5 According to the clinical criteria suggested by Niikawa et al,4 our patient presented with all but one criteria: he did not have intellectual disability. He did present with congenital heart defects and renourinary malformations, previously described in this syndrome.17 Ocular manifestations are reported in up to half of the patients.6 18 21 To the best of our knowledge, there is only one case describing SND in a patient with KS.29 Although the prevalence of SND is higher in middle-aged women with previous history of ocular surface inflammation, it can appear at any age, and the aetiology is often unknown. In this case report, ophthalmological follow-up began at the age of 3 years, when the peripheral corneal nodules were reported. It is known that patients with KS have immunological dysfunction and increased infection risk,17 thus we cannot exclude the possibility that previous corneal inflammation could have triggered the corneal degeneration. The clinical diagnosis of SND is based primarily on slit-lamp examination; however, AS-OCT may be a valuable tool in the diagnosis, management and follow-up of these cases. We hypothesise that the immunological dysfunction might have predisposed to corneal inflammation, with subsequent corneal degeneration. Management of SND using conservative therapy with ocular lubrication, eyelid hygiene and ocular NSAID therapy is generally sufficient.24 In situations that require surgical intervention, manual superficial keratectomy is usually effective, as shown in the case described. Phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK), penetrating keratoplasty, lamellar keratoplasty or anterior keratectomy have also been used.25 26 33

This report documents the association of SND with KS. We aim to draw attention to the primordial importance of an early ophthalmological evaluation of all children with KS, due to the high prevalence of ocular anomalies in these patients. Prompt detection and treatment may well prevent visual impairment.

Learning points.

About half of patients with Kabuki syndrome have ophthalmological involvement.

This is a case report of Salzmann nodular degeneration (SND) in a patient with KS, a rarely documented association.

SND usually responds favourably to conservative therapy, although superficial keratectomy is sometimes required.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM contributed to the follow-up of the patient during the postoperative period, to the data collection and to the writing of manuscript. MAO contributed to the preoperative evaluation of the patient, data collection, including the anterior segment photographs, and was the assistant surgeon. AR was the main surgeon, contributed to data collection and interpretation of the anterior segment OCT images. JM contributed to the follow-up of the patient during the preoperative and the postoperative period and helped in the therapeutic decision. All authors contributed to development of the manuscript or provided critical content revisions.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Matsumoto N, Niikawa N. Kabuki make-up syndrome: a review. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2003;117C:57–65. 10.1002/ajmg.c.10020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuroki Y, Suzuki Y, Chyo H, et al. . A new malformation syndrome of long palpebral fissures, large ears, depressed nasal tip, and skeletal anomalies associated with postnatal dwarfism and mental retardation. J Pediatr 1981;99:570–3. 10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80256-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Niikawa N, Matsuura N, Fukushima Y, et al. . Kabuki make-up syndrome: a syndrome of mental retardation, unusual facies, large and protruding ears, and postnatal growth deficiency. J Pediatr 1981;99:565–9. 10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80255-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Niikawa N, Kuroki Y, Kajii T, et al. . Kabuki make-up (Niikawa-Kuroki) syndrome: a study of 62 patients. Am J Med Genet 1988;31:565–89. 10.1002/ajmg.1320310312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Digilio MC, Marino B, Toscano A, et al. . Congenital heart defects in Kabuki syndrome. Am J Med Genet 2001;100:269–74. 10.1002/ajmg.1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adam MP, Hudgins L. Kabuki syndrome: a review. Clin Genet 2004;67:209–19. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hannibal MC, Buckingham KJ, Ng SB, et al. . Spectrum of MLL2 (ALR) mutations in 110 cases of Kabuki syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2011;155A:1511–6. 10.1002/ajmg.a.34074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Banka S, Lederer D, Benoit V, et al. . Novel KDM6A (UTX) mutations and a clinical and molecular review of the X-linked Kabuki syndrome (KS2). Clin Genet 2014:1––7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lederer D, Grisart B, Digilio MC, et al. . Deletion of KDM6A, a histone demethylase interacting with MLL2, in three patients with Kabuki syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2012;90:119–24. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Y, Bögershausen N, Alanay Y, et al. . A mutation screen in patients with Kabuki syndrome. Hum Genet 2011;130:715–24. 10.1007/s00439-011-1004-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Micale L, Augello B, Fusco C, et al. . Mutation spectrum of MLL2 in a cohort of kabuki syndrome patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2011;6(Mll:1––8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ, et al. . Exome sequencing identifies MLL2 mutations as a cause of Kabuki syndrome. Nat Genet 2010;42 10.1038/ng.646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paulussen AD, Stegmann AP, Blok MJ, et al. . MLL2 mutation spectrum in 45 patients with Kabuki syndrome. Hum Mutat 2011;32:E2018–E2025. 10.1002/humu.21416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McVeigh TP, Banka S, Reardon W. Kabuki syndrome: expanding the phenotype to include microphthalmia and anophthalmia. Clin Dysmorphol 2015;24:135–9. 10.1097/MCD.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen Y-H, Sun M-H, Hsia S-H, et al. . Rare ocular features in a case of Kabuki syndrome (Niikawa-Kuroki syndrome). BMC Ophthalmol 2014;14:2––4. 10.1186/1471-2415-14-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Turner C, Lachlan K, Amerasinghe N, et al. . Kabuki syndrome: new ocular findings but no evidence of 8p22-p23.1 duplications in a clinically defined cohort. Eur J Hum Genet 2005;13:716–20. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kluijt I, van Dorp DB, Kwee ML, et al. . Kabuki syndrome - report of six cases and review of the literature with emphasis on ocular features. Ophthalmic Genet 2000;21:51–61. 10.1076/1381-6810(200003)2111-IFT051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Evans SL, Kumar N, Rashid MH, et al. . New ocular findings in a case of Kabuki syndrome. Eye 2004;18:322–4. 10.1038/sj.eye.6700649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bögershausen N, Wollnik B. Unmasking Kabuki syndrome. Clin Genet 2013;83:201–11. 10.1111/cge.12051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawame H, Hannibal MC, Hudgins L, et al. . Phenotypic spectrum and management issues in Kabuki syndrome. J Pediatr 1999;134:480–5. 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70207-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ming JE, Russell KL, Bason L, et al. . Coloboma and other ophthalmologic anomalies in Kabuki syndrome: distinction from charge association. Am J Med Genet A 2003;123A:249–52. 10.1002/ajmg.a.20277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anandan M, Porter NJ, Nemeth AH, et al. . Coats-type retinal telangiectasia in case of Kabuki make-up syndrome (Niikawa-Kuroki syndrome). Ophthalmic Genet 2005;26:181–3. 10.1080/13816810500374433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chaudhry IA, Shamsi FA, Alkuraya HS, et al. . Ocular manifestations in Kabuki syndrome: the first report from Saudi Arabia. Int Ophthalmol 2008;28:131–4. 10.1007/s10792-007-9118-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Graue-Hernández EO, Mannis MJ, Eliasieh K, et al. . Salzmann nodular degeneration. Cornea 2010;29:283–9. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181b7658d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hurmeric V, Yoo SH, Karp CL, et al. . In vivo morphologic characteristics of Salzmann nodular degeneration with ultra-high-resolution optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:248–56. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maharana PK, Sharma N, Das S, et al. . Salzmann’s Nodular Degeneration. Ocul Surf [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farjo AA, Halperin GI, Syed N, et al. . Salzmann’s nodular corneal degeneration clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes. Cornea 2006;25:11–15. 10.1097/01.ico.0000167879.88815.6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stone DU, Astley RA, Shaver RP, et al. . Histopathology of Salzmann nodular corneal degeneration. Cornea 2008;27:148–51. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31815a50fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krassin JG, Affeldt JC. Corneal Findings in Kabuki’s Syndrome. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 2007;48:5873. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maust HA, Raber IM. Peripheral hypertrophic subepithelial corneal degeneration. Eye Contact Lens 2003;29:266–9. 10.1097/01.icl.0000087489.61955.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Magovern M, Wright JD, Mohammed A. Spheroidal degeneration of the cornea: a clinicopathologic case report. Cornea 2004;23:84–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jaworski A, Arvanitis A. Salzmann’s nodular degeneration of the cornea. Clin Exp Optom 1999;82:14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khaireddin R, Katz T, Baile RB, et al. . Superficial keratectomy, PTK, and mitomycin C as a combined treatment option for Salzmann’s nodular degeneration: a follow-up of eight eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011;249:1211–5. 10.1007/s00417-011-1643-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]