1.0. Introduction

A more than five-fold increase in opioid overdose deaths from 1999 to 2016 (Hennegan, Warner, & Minnino, 2018) has generated significant media and government attention to opioid use and opioid use disorders (OUDs) (Allen & Kelley, 2017; City of Philadelphia & Mayor James F. Kenney, 2017; State of Wisconsin & Task Force on Opioid Abuse, 2017). Despite federal, state, and community initiatives to halt the epidemic, the opioid overdose death rate per day increased by 91.5% from 2012 (60.1 overdoses per day) to 2016 (115.1 overdoses per day (CDC, 2016). Preventing overdose and reducing OUD require expanded access to opioid agonist therapy (i.e., buprenorphine and methadone) (Jones, Christensen, & Gladden, 2017; Rudd, Seth, David, & Scholl, 2016). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend use of opioid agonist therapy in combination with counseling services to treat OUD (Volkow, Frieden, Hyde, & Cha, 2014; World Health Organization, 2003). Only 35% of individuals with an OUD diagnosis have treatment plans that include opioid agonist therapy in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2017). The persistent low adoption of buprenorphine opioid agonist pharmacotherapy has been tied to payment and reimbursement barriers (Heinrich & Cummings, 2014; Knudsen & Roman, 2012).

Trial Setting

Ohio’s opioid overdose fatality rate increased from 4.2/100,000 in 1999 to 39.1/100,000 in 2016 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2016). The trial team partnered with the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services to test organizational change strategies payers and treatment providers can use to improve access to buprenorphine. The payers in the study were Ohio’s Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS) boards. The 51 ADAMHS boards in Ohio coordinate the state’s public behavioral health system. Each board covers one to six of Ohio’s 88 counties and disperses Mental Health (MH) and Substance Abuse and Prevention and Treatment (SAPT) block grant funds, as well as state funds and local levies supporting mental health and addiction services. The treatment agencies were private non-profit specialty substance use disorder (SUD) providers.

The trial focused on buprenorphine because physicians with a buprenorphine waiver may prescribe the opioid agonist therapy and treat patients with OUDs in medical offices and specialty treatment provider settings. Methadone (another opioid agonist therapy) can only be dispensed in federally regulated opioid treatment programs. Ohio considers buprenorphine therapy a key evidence-based practice for addressing the opioid epidemic (Sherba et al., 2012). An advantage to using buprenorphine in treating OUDs is that it prevents withdrawal symptoms and can be administered within 12 to 24 hours of last opioid use. Extended-release naltrexone (an opioid antagonist therapy), in contrast, requires a 7- to 10-day period of opioid abstinence (Aletraris, Bond Edmond, & Roman, 2015). Disadvantages of using buprenorphine include the risk of diversion for non-medical purposes (Johanson, Arfken, di Menza, & Schuster, 2012). Mediating this risk requires prescribers to implement diversion prevention strategies, such as monitoring urine drug screens and conducting buprenorphine medication reconciliations between prescription refills. Prescribers must also complete special education on treatment of OUDs and request a DATA 2000 waiver from the Controlled Substance Act, which prohibits use of a narcotic to treat narcotic addiction (Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000), 2000).

When the trial began in 2012, 19.0% of 14,311 specialty treatment centers in the U.S. and 18.7% in Ohio used buprenorphine pharmacotherapy (SAMHSA, 2013); nationally, 23.2% of the 455,319 patients with an OUD diagnosis received this therapy (SAMHSA, 2014).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Fourteen of the 51 ADAMHS boards agreed to join the trial. The 14 boards represented 23 of Ohio’s 88 counties. Based on the United State Department of Agriculture (USDA) definitions of Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (U.S. Department of Agriculture & Economic Research Service, 2017) for counties, the study included six metro areas of more than 1,000,000 residents, six metro areas with 250,000 to 1,000,000 residents, five urban areas of more than 20,000 next to a metro area, four urban populations of less than 20,000 next to metro areas, and two entirely rural counties. Each board invited addiction treatment agencies with 75 or more annual admissions to participate in the trial. Forty-eight of the 53 eligible treatment agencies in the 14 ADAMHS board areas enrolled in the trial. During the trial, the composition of key ADAMHS board personnel did not change between the baseline and post-experiment data collection. One participating treatment program closed before study completion.

2.2. Trial design

The trial used a multi-level intervention, called the Advancing Recovery Framework (Molfenter et al. 2013b, Schmidt et al. 2012), directed at both payers and treatment agencies, to study their dual roles in increasing the use of buprenorphine. The cluster randomized control trial placed 14 ADAMHS board payers and their provider treatment agencies into intervention and comparison conditions.

For randomization, seven matched-pair blocks of ADAMHS boards were created based on percentage of opioid admissions, population size, and ratio of OUD treatment admissions to physicians licensed to prescribe buprenorphine in the Board’s jurisdiction. The recruitment began with a convenience sample, and then two ADAMHS Boards were recruited to complete the matched-pair blocks. The matched-pair blocks controlled for environmental variables and created a balanced design. The trial included a two-month baseline period (in 2012), a 24-month experimental period (in 2013 & 2014), and a 12-month post-experimental period (in 2015) to assess sustainability.

Provider treatment agencies in both conditions received education and coaching on implementing the NIATx organizational change model to increase buprenorphine use. The NIATx Model has been shown to successfully improve substance abuse delivery processes (Gustafson et al., 2013; McCarty et al., 2007). Including the NIATx model across both arms was intended to strengthen the rigor of the comparison condition, as opposed to a pure control, and to document the incremental benefit of the Advancing Recovery Framework for system change. The NIATx model is a simplified version of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s organizational change and process improvement strategy (Gustafson et al., 2011; Langley et al., 2009). Participants use plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles to initiate and test changes to organizational workflow and processes. In the comparison condition, intervention activities consisted of an in-person kick-off retreat for treatment agency executives and change leaders at the beginning of the experimental period, followed by monthly coaching calls and e-mail correspondence as needed until the start of the post-experimental period. At the end of the experimental period, the ADAMHS board clinical officer or executive director completed a survey that assessed barriers encountered and strategies applied to address barriers and improve buprenorphine use rates.

The Advancing Recovery Framework’s multi-organizational learning collaborative method delivers technical assistance through coaches (Molfenter, McCarty, Capoccia, & Gustafson, 2013b). The intervention condition included three learning sessions conducted at the beginning, mid-point, and end of the 24-month experimental period, with monthly coaching calls scheduled between each of the learning sessions. The learning sessions included both ADAMHS Board and treatment agencies personnel, with participants from all entities. The boards and the treatment providers had facilitated interactions with each other only in the intervention condition.

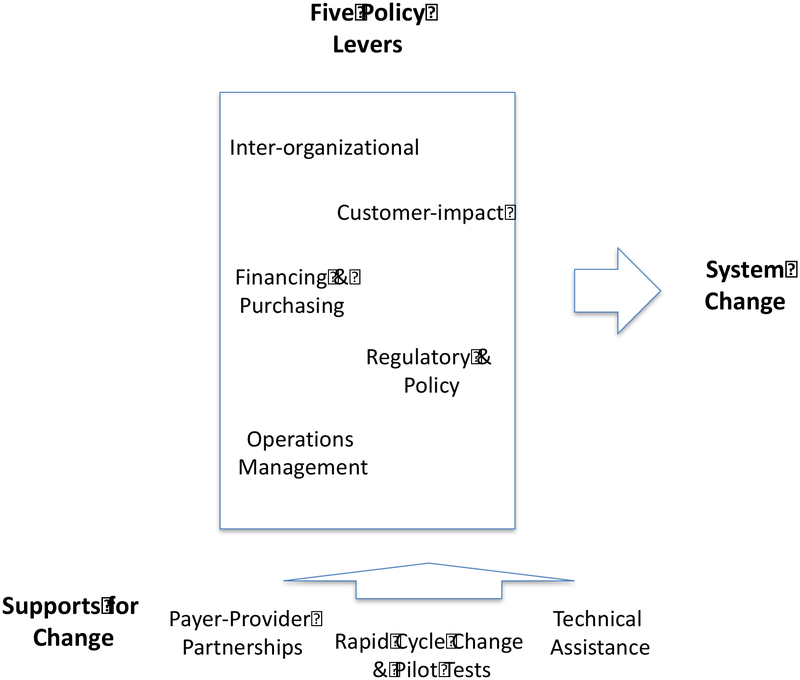

The content in the initial learning session addressed the NIATx model and only differed from the content in the comparison condition in that it included 1) a section on the use of policy levers to activate systems change and 2) time allocated for the payers and providers to discuss barriers and strategies. Between learning sessions, three sets of coach calls were scheduled monthly, one with both the ADAMHS board and their treatment agencies participating, one-on-one calls with each intervention board, and one-on-one calls with each treatment agency. In the learning sessions and monthly calls, ADAMHS Boards and treatment agencies convened to discuss application of the NIATx organizational change model, pilot tests or PDSA cycles being tested, barriers being encountered, new strategies for implementing buprenorphine, and to encourage each other and problem solve. The payers and treatment agencies could also e-mail their coaches as needed. There were across the study two payer coaches and three treatment agency coaches. The two payer coaches were practicing state and county executives from outside of Ohio and had experience with the Advancing Recovery and NIATx models, while the three treatment agency coaches were experienced NIATx coaches with 5+ years of experience each providing NIATx coaching. The coaches followed the same learning session and coach call agendas and met monthly to assure that a standardized approach was applied across treatment agencies. The coaches, who were versed in buprenorphine pharmacotherapy implementation techniques, facilitated these sessions and offered advice on what changes to make and how to make them. The Boards’ role in the intervention, in addition to partnering with provider treatment agencies, was to promote system change by applying the five Advancing Recovery Framework policy levers: a) Increase resources for use of buprenorphine through financing and contracting, b) Set expectations for providers to use buprenorphine, c) Remove or reduce regulatory barriers, d) Provide support to remove operational barriers, and e) Partner with other agencies within the county and the state to increase access to buprenorphine (Figure 1) (Molfenter, et al., 2013b). Advancing Recovery Framework levers have similarities with the strategies identified in a multi-state implementation of evidence-based mental health practices in state public mental health systems (Magnabosco, 2006). The strategies encourage payer practices that extend beyond using payment to promote targeted evidence-based practices.

Figure 1:

Advancing Recovery Framework

2.3. Outcome measures.

The primary outcome variable was the percentage of OUD patients receiving buprenorphine prescriptions per treatment agency. Data were collected monthly during the baseline, experimental, and post-experimental periods. Five sets of variables that may affect buprenorphine use were examined: a) patient gender and ethnicity; b) treatment agency size; c) percent of county admissions for OUD, d) buprenorphine prescribers per treatment agency and e) county age-adjusted unintentional overdose death rates (Knudsen, Abraham, & Oser, 2011; Knudsen, Abraham, & Roman, 2011; Molfenter et al., 2013a; Unick, Rosenblum, Mars, & Ciccarone, 2013). The treatment agencies provided patient-level data via a study-specific report template and agency-level data based on annual surveys of treatment agency characteristics. The Ohio Department of Health provided data on the unintentional overdose death rates by county for 2012–2014 (Ohio Department of Health, 2014). Each coach documented the frequency and duration of coach calls and e-mails. The calls typically lasted about 30 minutes and included the same 1–2 key contacts per board or treatment agency site throughout the intervention period. Coaches made these contacts with the ADAMHS boards in the intervention arm and with the treatment agencies in both arms. The payer coach calls included the monthly individual calls with the ADAMHS Board and the calls between the coach and the combination of the ADAMHS Board and their treatment agencies. The treatment agency counts only included the monthly individual coach calls. All coach calls were supposed to occur monthly, but frequency varied based on availability and interest of the ADAMHS boards and treatment agencies.

At the end of the experimental period, the ADAMHS board clinical officer or executive director completed a survey that assessed barriers encountered and strategies applied to address barriers and improve buprenorphine use rates. The survey items were based on Magnabosco’s payer strategies (Magnabosco, 2006). The barriers and strategies survey used a 7=point Likert Scale (1=Strongly Disagree, and 7=Strongly Agree) and these survey results were not shared with the boards. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the Ohio Department of Health.

2.4. Data Analysis

Demographic variables of gender, ethnicity, and % of opioid admissions of the client populations served by the boards’ participating treatment agencies, as well as other background characteristics, were tested for differences between intervention and comparison condition boards at baseline. Any variables found not to have significant differences were excluded as covariates and successful randomization before treatment resumed. The two study conditions, three periods, and their interactions were included in the analysis models. Main and interaction effects between the two study conditions and time, across each phase, were tested using logistic regression analysis. An ANOVA tested relationships between the frequency of telephone and e-mail coaching activities and changes in the percentage of buprenorphine use for patients with OUD patients within each treatment agency. Kendall’s tau-b for ordinal variables assessed levels of payer strategies and payer perceived barriers between study conditions.

3. Results

During the experimental and maintenance periods, 22,295 individuals with an OUD diagnosis were admitted to care in the participating treatment centers. Trial conditions between study arms were similar for gender (50.0% female; p=.344), ethnicity (24.7% nonwhite, p=.236), treatment agency size (705 mean annual admissions; p=.239), percent opioid admissions per ADAMHS board (33.4%; p=.141), and unintentional county age-adjusted opioid overdose death rates (17.9/100,000; p=.097) (Table 1). The prescriber capacity did not increase in the comparison condition (1.4 prescribers per treatment agency in 2013 versus 1.4 in 2015), while the intervention condition increased from 1.5 to 1.9 prescribers per treatment agency across this time.

Table 1:

County Board Area Characteristics (By Study Arm Agency Sites)

| Intervention (n = 7 County Boards, 28 orgs) | Control (n = 7 County Boards, 20 orgs) | p - Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 50.60% | 48.62% | .344 |

| Male | 49.40% | 51.38% | ||

| Ethnicity Served (All Admissions) | Black/African American | 22.50% | 20.34% | .236 |

| American Indian | 0.43% | 0.33% | ||

| Asian | 0.72% | 0.24% | ||

| Native Hawaiian | 0.32% | 0.21% | ||

| White Caucasian | 72.07% | 75.40% | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3.47% | 3.08% | ||

| More than one race | .49% | .40% | ||

| Treatment Agency Size | <100 | 8.00% | 12.90% | .239 |

| 100–499 | 28.00% | 58.06% | ||

| 500–999 | 40.00% | 19.35% | ||

| 1000+ | 24.00% | 9.68% | ||

| % of Opioid Admissions | <10% | 8.00% | 10.00% | .141 |

| 10–19% | 20.00% | 26.67% | ||

| 20–29% | 20.00% | 20.00% | ||

| 30–39% | 20.00% | 26.67% | ||

| 40–49% | 12.00% | 10.00% | ||

| 50–59% | 4.00% | 3.33% | ||

| 60+% | 16.00% | 3.33% | ||

| Unintentional Age-Adjusted Overdose Death Rates | 1.56/100,000 | 2.06/100,000 | .097 |

The intervention condition experienced a 3.0-fold increase in the percentage of buprenorphine use by OUD patients during the experimental period (9.5% baseline; 28.5% experimental). Comparison ADAMHS boards and their providers experienced a significantly lower increase in percentage of buprenorphine use (10.9% baseline; 19.6% experimental) with an adjusted difference-in-differences of 10.3% (95% CI [9.9%, 10.7%]), p <.001). During the post-experimental period, the intervention condition treatment agencies’ percentage of buprenorphine use by OUD patients increased to 32.8% of patients with OUD. The comparison group declined slightly to 18.6% (Table 2). The interaction terms between the two study conditions and time across each period were not included in the final model because these terms were not significant in the initial analytic models. The difference in the number of OUD patients between the two study conditions in the experimental period (intervention n=11,092; comparison n=5,356) and post-experimental period (intervention n=4,235; comparison n=1,611) was due to more treatment agencies in the experimental group (n = 28) than in the comparison group (n = 20) and greater growth of OUD patients in the experimental treatment agencies. The drop in the number of subjects between the experimental and post-experimental periods occurred due to problems with data collection compliance in the post-experimental period and no meaningful differences in the attrition rates were found, suggesting that the attrition likely occurred at random.

Table 2:

Percentage of Buprenorphine Use by Trial Condition

| Phases | Percentage of Buprenorphine Use for OUD Patients | Treatment Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Intervention | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |

| Baseline | 34/312 (10.89%) |

35/370 (9.46%) |

.85 | (.50, 1.45) | .611 |

| Experimental | 1052/5356 (19.64%) |

3158/11092 (28.48%) |

1.63 | (1.50, 1.76) | .000 |

| Post-Experimental | 300/1611 (18.62%) |

1388/4235 (32.77%) |

2.13 | (1.85, 2.46) | .000 |

The payer phone coach calls had a range of 13–43 calls with a mean of 33.4 (Standard Deviation (SD) of 12.9), and the e-mails had a range of 3–17 e-mails with a mean of 9.9 e-mails (SD of 4.3) over the 24 months. The treatment agency calls across both study conditions had a range of 1–23 with a mean of 13.3 (SD of 7.6), and the e-mails had a range of 0–50 e-mails with a mean of 6.5 (SD of 10.8). There was a significant relationship between the number of coach phone consultations with the ADAMHS (payer) boards and the changes in the percentage of buprenorphine use for patients with OUD diagnoses in the corresponding Board areas (p =0.041). Coaching e-mails with the ADAMHS (payer) boards did not have a significant relationship with change in the percentage of buprenorphine patients (p=.480). Also, there were no significant associations between the number of treatment agency coach calls (p=.100) and e-mails (p=.546) and changes in buprenorphine use across conditions.

In the survey, ADAMHS Boards reported the use of two primary strategies to increase buprenorphine use 1) “We provide reimbursement support for use of buprenorphine” (Likert Score of 6.42, with 7 = strongly agree), and 2) “We provide start-up funds for use of buprenorphine” (Likert Score of 6.19). The intervention and comparison groups did not differ in the use of these strategies. Boards in the intervention condition were more likely to report of utilization of a committee composed of the board and provider representatives to promote the use of buprenorphine and the ADAMHS boards setting expectations for using buprenorphine, as encouraged in the intervention condition (Table 3). These expectations were typically set verbally, and ADAMHS boards reported the expectations were rarely part of contractual obligations.

Table 3:

Payer Strategies means on 7-point scales for intervention and comparison conditions (Grouped by Advancing Recovery Lever)

| Overall | Intervention | Comparison | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financing & Purchasing | ||||

| We provide reimbursement support for use of buprenorphine | 6.42 | 6.14 | 6.75 | .928 |

| We provide start-up funds for use of buprenorphine. | 6.19 | 5.85 | 6.58 | .809 |

| Expectation Setting | ||||

| We inform providers that we expect them to use buprenorphine. | 5.46 | 6.00 | 4.83 | .028* |

| We talk to our providers about community outreach opportunities to promote use of buprenorphine. | 4.89 | 4.85 | 4.93 | .847 |

| Operations Management | ||||

| We have sponsored community events to address buprenorphine concerns. | 4.64 | 5.58 | 3.71 | .165 |

| We use data to monitor the impact of using buprenorphine. | 4.58 | 4.57 | 4.58 | .771 |

| We have engaged the public related to use of buprenorphine. | 4.28 | 4.29 | 4.29 | .894 |

| We instituted a committee with provider representation to assure increased use of buprenorphine. | 3.62 | 5.43 | 1.50 | .000** |

| We instituted a committee to assure increased use of buprenorphine | 3.12 | 4.71 | 1.25 | .000** |

| Inter-organizational Partnering | ||||

| We conducted outreach to other governmental agencies to get buprenorphine paid for | 3.83 | 4.00 | 3.67 | .745 |

: significant at alpha = 0.05

: significant at alpha = 0.01

Survey respondents indicated two perceived barriers to the use of buprenorphine: 1) physicians unwilling to prescribe buprenorphine (Likert Score of 5.8, with 7.0 = strongly agree) and 2) federal limits on the number of patients a physician can prescribe to (Likert Score of 5.73). Before 2017, federal regulations restricted prescribers to a limit of 100 buprenorphine patients (current regulations set the limit at 250 patients). Both of these barriers were significant between the intervention and comparison conditions and more pronounced in the intervention condition than the comparison condition (see Table 4). There were no significant differences for other payer-perceived barriers addressing financial issues (i.e., insufficient funds and buprenorphine cost), attitudes toward use of buprenorphine (i.e., diversion concerns and anti-medication-assisted treatment thinking), and provider knowledge (Table 4).

Table 4:

Payer-Perceived Barriers means on 7-point scales for intervention and comparison groups

| Overall | Intervention | Comparison | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians unwilling to prescribe buprenorphine | 5.80 | 6.75 | 4.71 | .000** |

| Limits on the number of patients a physician can prescribe to | 5.73 | 6.5 | 4.86 | .009** |

| Concerns regarding buprenorphine diversion | 5.47 | 5.25 | 5.71 | .954 |

| Anti-buprenorphine (or opioid treatment pharmacotherapy) thinking | 5.40 | 5.25 | 5.57 | .757 |

| Insufficient funds for buprenorphine | 4.67 | 4.75 | 4.14 | .574 |

| A lack of criminal justice support for buprenorphine | 4.20 | 4.25 | 4.14 | .773 |

| High cost of buprenorphine | 3.80 | 4.00 | 3.57 | .957 |

| Addiction treatment provider’s lack of buprenorphine knowledge | 2.60 | 2.62 | 2.57 | .863 |

4. Discussion:

Payers can leverage their purchasing role to guide provider behavior through their ability to pay or not to pay for services. Payers can discourage a practice through pre-authorization requirements and refusal to cover the service (Korthuis et al., 2017; McCarty, Priest, & Korthuis, 2018). What is less clear is how payers can encourage use of a desired practice through non-financial actions. In this trial, buprenorphine use increased when the ADAMHS boards in both conditions of the trial reimbursed for and provided start-up funds for buprenorphine. However, the condition that included the AR strategy of payer-provider partnering increased use of buprenorphine by an odds ratio of 2.1. The payer-provider partnering process increased payers’ ability to request greater use of buprenorphine. Partnering also led to payers helping link providers to financial and non-financial resources needed to remove barriers and develop buprenorphine treatment infrastructure. Coaching technical assistance during phone calls assisted the payers in creating an environment for greater buprenorphine utilization as a percentage of OUD patients.

The coaching technical assistance in the experimental condition initially focused on increasing the financial resources available to support use of buprenorphine. In qualitative interviews conducted at baseline, providers identified cost of buprenorphine was a primary barrier (Molfenter et al., 2015). Grants from the boards paid for buprenorphine medication and prescriber time for initial patient assessments, writing orders for the prescription, follow-up care, and lab tests for urine drug screens.

It became apparent by the mid-point of the experimental period that financial resources alone were not sufficient to increase buprenorphine use rates. Barriers related to system capacity and workforce development arose at the provider level. System workflow issues included implementing a screening process to identify eligible buprenorphine patients, setting up diversion prevention procedures such as random urine drug screens and medication checks, and developing processes for patients to obtain the medication and access support groups that were accepting of medication pharmacotherapy. Workforce capacity building focused on building prescriber capacity. Shortages of practicing waivered buprenorphine prescribers hindered efforts to expand use of the medication (Stein et al., 2015).

System workflow issues and workforce capacity development provided opportunities where the pilot and rapid cycle tests occurred (described in Figure 1). These treatment agency change practices typically took place in programs once the use of buprenorphine was implemented. Once treatment agencies decided to use buprenorphine, often after a lengthy review process by management and clinicians, there was limited rapid-cycle testing—just a desire to move ahead. The technical assistance the coaches provided during the implementation period focused on imparting educational techniques to get personnel supportive of the practice and implementation policies required for the screening, prescribing, and maintenance of buprenorphine. Post-implementation rapid-cycle tests were used to streamline screening and induction procedures, improve diversion prevention measures, identify alternate sources of buprenorphine payment, increase buprenorphine retention rates, and increase prescriber capacity.

The ADAMHS boards encouraged treatment agencies to make the most of the buprenorphine slots of currently waivered prescribers, and encourage to conduct outreach to increase buprenorphine waiver applications by other staff physicians. The boards also assisted treatment agencies in recruiting additional physicians through public forums and outreach. The analysis of buprenorphine prescriber capacity found capacity did not increase in the comparison condition (1.4 prescribers per treatment agency in 2013 versus 1.4 in 2015), while the intervention condition had an increase from 1.5 to 1.9 prescribers per treatment agency across this time. Despite this growth in prescribers, the two most pronounced barriers in the intervention condition were related to the capacity of buprenorphine prescribers, suggesting a need for even more capacity building.

Significant amounts of state and federal funds address the opioid epidemic. States have used these resources to fund pharmacotherapy for OUD treatment and recovery. Our findings suggest that funding for pharmacotherapy addresses only part of the issue. In our trial, financial resources increased buprenorphine use somewhat. Removing barriers, improving workflow, and developing capacity through targeted technical assistance led to greater improvement in buprenorphine use. As new funds are allocated to pay for treatment and medications to address the opioid epidemic, technical assistance mechanisms should be put in place to assure the investments extend beyond reimbursement. Replicating established OUD pharmacotherapy models could increase the likelihood that applied technical assistance will lead to new prescribers who will continue to prescribe buprenorphine over time (Korthuis et al., 2017; McCarty et al., 2018). Monetary resources should also be invested in technical assistance on how to improve workflows and recruit and train new prescribers so clinical teams can maximize the impact of dollars allocated for the opioid crisis. This assistance will prevent existing funds from being spent solely on traditional training events, which fall short because the participants often fail to apply the content of those programs (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Kaner, Lock, McAvoy, Heather, & Gilvarry, 1999).

4.1. Limitations

While the lessons of this program could have broad practical implications, several limitations should be noted. First, the ADAMHS boards are governmental entities that may not act like private health insurance companies. Private insurance companies tend to have a national presence and fund services through claims submissions, while the ADAMHS boards provide grants-in-aid payments and are accountable to county stakeholders. Second, it should also be noted that the participating treatment agencies have other payers in addition to the ADAMHS boards. Yet, the ADAMHS Boards were the largest payer for most of the participating treatment agencies. Third, while the treatment agencies were exposed both to NIATx Organizational Change Model and to coaching, the ADAMHS boards in the comparison condition were treated as a treatment as usual condition. This resulted in the lack of an “attention control” between payers in the intervention and comparison arms due to coaching to payers in the intervention arm. Fourth, even though the study involved rural and urban counties and the participating counties included 41% of the state’s population, the trial only included 27.5% of the ADAMHS boards. This limited sample could affect the sample’s generalizability. Lastly, these findings are from one state. Environmental conditions and funding mechanisms vary from state to state, and generalizability to other states may be limited. However, successful OUD pharmacotherapy implementation efforts in Vermont and the city of Baltimore demonstrate that both money and technical assistance were ultimately fundamental to the successful provision of buprenorphine (Brooklyn & Sigmon, 2017; Schwartz et al., 2013).

5. Conclusions

This project found that payers should not be “silent partners” in funding OUD treatment services. The funds they distribute are essential to providing health care services, but payers should also interact directly with treatment providers. Partnering increases provider accountability to payers, as well as connections to other resources. Payers can support infrastructure development that in this trial contributed to greater use of the targeted practice: buprenorphine. As new efforts are developed to improve OUD treatment, including payers in capacity building technical assistance efforts could lead to the most efficacious use of these funds. Approaches that include funding, plus technical assistance with provider partnering, should be tested to determine their impact on reducing OUD prevalence and morbidity.

Highlights.

Payers and providers can partner to increase use of opioid agonist therapy for OUD.

Buprenorphine use was greatest when payers worked with providers on removing barriers.

Dose of payer coaching was correlated with the main outcome measure, while provider coaching was not.

The greatest barrier to buprenorphine expansion was the need for more prescribers.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of Funding

The research and preparation of the manuscript were supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA030431) and (R01 DA0414150).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts: The NIATx organizational change model used in part of this trial was developed by the Center for Health Enhancement System Studies (CHESS) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Todd Molfenter, Ph.D., is a faculty member at the CHESS Center. Also, Dr. Molfenter is affiliated with the NIATx Foundation, the organization responsible for making the NIATx organizational change model available to the public. Dr. Molfenter has an institutionally approved plan to manage potential conflicts of interest. The individuals who conducted the data collection and interpretation for this manuscript have no affiliation with the NIATx Foundation.

References

- Aletraris L, Bond Edmond M, & Roman PM (2015). Adoption of injectable naltrexone in U.S. substance use disorder treatment programs. Journal of studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(1), 143–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen G, & Kelley A (2017. October 26). Trump administration declares opioid crisis a public health emergency. Morning Edition, National Public Radio; Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2017/10/26/560083795/president-trump-may-declare-opioid-epidemic-national-emergency. Accessed 10 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, & Kendall PC (2010). Training therapists in evidence-based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology : a publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association, 17(1), 1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooklyn JR, & Sigmon SC (2017). Vermont hub-and-spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: development, implementation, and impact. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 11(4), 286–292. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Retrieved from http://wonder.cdc.gov/. Accessed 10 August 2018.

- City of Philadelphia, & Mayor Kenney James F.. (2017). Mayor’s Task Force to combat the opioid epidemic in Philadelphia. Retrieved from http://dbhids.org/opioid. Accessed 10 August 2018.

- Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000). Public Law No. 106–310, Title XXXV-Waiver authority for physicians who dispense or prescribe certain narcotic drugs for maintenance treatment or detoxification treatment, Public Law No. 106–310 C.F.R. (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Johnson KA, Capoccia V, Cotter F, Ford JH II, Holloway D, … Owens B (2011). The NIATx model: Process improvement in behavioral health. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Quanbeck AR, Robinson JM, Ford JH, Pulvermacher A, French MT, McConnell J, Batalden PB, Hoffman KA & McCarty D (2013). Which elements of improvement collaboratives are most effective? A cluster‐randomized trial. Addiction, 108(6), 1145–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich CJ, & Cummings GR (2014). Adoption and diffusion of evidence‐based addiction medications in substance abuse treatment. Health Services Research, 49(1), 127–152. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Warner M, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 294. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017/CDC. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER) Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson CE, Arfken CL, di Menza S, & Schuster CR (2012). Diversion and abuse of buprenorphine: Findings from national surveys of treatment patients and physicians. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 120(1), 190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Christensen A, & Gladden RM (2017). Increases in prescription opioid injection abuse among treatment admissions in the United States, 2004–2013. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 176, 89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Lock CA, McAvoy BR, Heather N, & Gilvarry E (1999). A RCT of three training and support strategies to encourage implementation of screening and brief alcohol intervention by general practitioners. The British Journal of General Practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 49(446), 699–703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, & Oser CB (2011). Barriers to the implementation of medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders: The importance of funding policies and medical infrastructure. Evaluation and Program Planning, 34(4), 375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, & Roman PM (2011). Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 5(1), 21–27. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d41ddb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, & Roman PM (2012). Financial factors and the implementation of medications for treating opioid use disorders. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 6(4), 280–286. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318262a97a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis PT, McCarty D, Weimer M, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Zakher B, … Chou R (2017). Primary care-based models for the treatment of opioid use disorder: A scoping review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(4), 268–278. doi: 10.7326/m16-2149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, & Provost LP (2009). The improvement guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Magnabosco JL (2006). Innovations in mental health services implementation: A report on state-level data from the US Evidence-Based Practices Project. Implementation Science, 1(13), 13 10.1186/1748-5908-1-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Gustafson DH, Wisdom JP, Ford J, Choi D, Molfenter T, Capoccia V & Cotter F (2007). The Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx): enhancing access and retention. Drug and alcohol dependence, 88(2), 138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Priest KC, & Korthuis PT (2018). Treatment and prevention of opioid use disorder: Challenges and opportunities. Annual Review of Public Health, 39, 525–541. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter T, Kim JS, Quanbeck A, Patel-Porter T, Starr S, & McCarty D (2013a). Testing use of payers to facilitate evidence-based practice adoption: Protocol for a cluster-randomized trial. Implementation Science, 8, 50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter T, McCarty D, Capoccia V, & Gustafson D (2013b). Development of a multilevel framework to increase use of targeted evidence-based practices in addiction treatment clinics. Journal of Public Health Frontier, 2(1), 11–20. doi: 10.5963/phf0201002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter T, Sherbeck C, Zehner M, Quanbeck A, McCarty D, Kim JS, & Starr S (2015). Implementing buprenorphine in addiction treatment: Payer and provider perspectives in Ohio. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 10(1), 13. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0009-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohio Department of Health. (2013). 2013 Ohio Drug Overdose Summary. Columbus, OH: Available at http://www.healthy.ohio.gov/~/media/HealthyOhio/ASSETS/Files/injuryprevention/2013OhioDrugOverdoseSummary.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ohio Department of Health. (2014). 2014 Ohio Preliminary Drug Overdose Report. Columbus, OH: Available at http://www.healthy.ohio.gov/~/media/HealthyOhio/ASSETS/Files/injuryprevention/2014 Ohio Preliminary Overdose Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, & Scholl L (2016). Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(5051), 1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Rieckmann T, Abraham A, Molfenter T, Capoccia V, Roman P, … & McCarty D (2012). Advancing recovery: Implementing evidence-based treatment for substance use disorders at the systems level. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 73(3), 413–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, Sharfstein JM, Warren G, Olsen Y, …. Jaffe JH (2013). Opioid agonist treatments and heroin overdose deaths in Baltimore, Maryland, 1995–2009. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 917–922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2012.301049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherba RT, Massatti RR, Potts L, Adhikari SB, Martt N, Starr S, & Porter Patel T (2012). A review of Ohio’s treatment capacity in addressing the state’s opiate epidemic. Journal of Drug Policy Analysis, 5(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1515/1941-2851.1036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- State of Wisconsin, Task Force on Opioid Abuse. (2017). Task Force to bring hope. Retrieved from https://hope.wi.gov/Pages/Home.aspx Accessed 10 August 2018.

- Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Dick AW, Burns RM, Pacula RL, Farmer CM, … Sorbero M (2015). Supply of buprenorphine waivered physicians: The influence of state policies. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 48(1), 104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2013). The N-SSATS Report: Trends in the use of methadone and buprenorphine at substance abuse treatment facilities: 2003 to 2011. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/NSSATS107/sr107-NSSATS-BuprenorphineTrends.htm. Accessed 10 August 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2002–2012. State admissions to substance abuse treatment services. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2002-2012_TEDS_State/2002_2012_Treatment_Episode_Data_Set_State.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2017). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2005–2015. State admissions to substance abuse treatment services. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Available at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2015TEDS_State Admissions.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture & Economic Research Service. (2017). Documentation. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation.aspx#.U9-B-4Vbw7C. Accessed 10 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, & Ciccarone D (2013). Intertwined epidemics: National demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993–2009. PloS One, 8(2), e54496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, & Cha SS (2014). Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(22), 2063–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley EL, Gay J, Roberts L, Moseley J, Hall O, Beeghly BC, … Somoza E (2012). Prescription drug abuse as a public health problem in Ohio: A case report. Public Health Nursing, 29(6), 553–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2003). Essential medicines: WHO model list (revised March 2005). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2005/a87017_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]