Abstract

The communicative role of ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) in rats is well established, with distinct USVs indicative of different affective states. USVs in the 22kHz range are typically emitted by adult rats when in anxiety- or fear-provoking situations (e.g. predator odor, social defeat), while 55kHz range USVs are typically emitted in appetitive situations (e.g., play, anticipation of reward). Previous work indicates that USVs (real-time and playback) can effectively communicate these affective states and influence changes in behavior and neural activity of the receiver. Changes in cFos activation following 22kHz USVs have been seen in cortical and limbic regions involved in anxiety, including the basolateral amygdala (BLA). However, it is unclear how USV playback influences cFos activity within the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), a region also thought to be critical in processing anxiety-related information, and the nucleus accumbens, a region associated with reward. The present work sought to characterize distinct behavioral, physiological, and neural responses in rats presented with aversive (22kHz) compared to appetitive (55kHz) USVs or silence. Our findings show that rats exposed to 22kHz USVs: 1) engage in anxiety-like behaviors in the elevated zero maze, and 2) show distinct patterns of cFos activation within the BLA and BNST that contrast those seen in 55kHz playback and silence. Specifically, 22kHz USVs increased cFos density in the anterodorsal nuclei, while 55kHz playback increased cFos in the oval nucleus of the BNST, without significant changes within the nucleus accumbens. These results provide important groundwork for leveraging ethologically-relevant stimuli in the rat to improve our understanding of anxiety-related responses in both typical and pathological populations.

Keywords: Ultrasonic vocalizations, basolateral amygdala, anxiety, BNST, c-Fos, Nucleus Accumbens

1. Introduction

The ability to communicate cues of threat and safety is essential to the survival and proliferation of virtually all species. In humans, both verbal and non-verbal (i.e. facial expressions) cues convey a wide range of nuanced emotional states, and it has been shown that viewing emotionally-charged facial expressions induce similar affective states in observers (e.g., Gump and Kulik, 1997; Wild et al., 2001). Conversely, while laboratory model animals – particularly rats - do not have the same capability to transfer information via intricate facial expression like humans, they do produce socially-relevant vocalizations at distinct frequency ranges that can signal information to conspecifics (Adolphs, 2001; Panksepp and Burgdorf, 2003). Indeed, such vocalizations can convey meaning ranging from appetitive to aversive and have been particularly well-characterized in laboratory rats (Knutson et al., 2002; Brudzynski, 2005; Burgdorf et al., 2008; Brudzynski, 2009; Wöhr and Schwarting, 2013; Brudzynski, 2013). Rat vocalizations span both sonic and ultrasonic frequencies (ultrasonic vocalizations; USVs) and can indicate states relating to pain in the sonic range (Jourdan et al., 1995; Han et al., 2005), rewarding pro-social states via emission of USVs in the 55kHz range (Seffer et al., 2014; Kisko et al., 2017), and fear or anxiety-like states via emission of USVs in the 22kHz frequency range (Brudzynski and Chiu, 1995; Kim et al., 2010). Of note, there are at least 14 distinct categories of USVs in the 55kHz range that have been identified in rats varying from 30kHz −90kHz, which appear to be context-dependent (Wright et al., 2010; Burke et al., 2017). These include few 55kHz range vocalizations associated with non-appetitive situations (i.e. an aggressive intruder; Wöhr et al., 2008), though the nuance and meaning of these are not yet well characterized. Conversely, rats reliably emit 22kHz USVs across a variety of fearful and anxiety-provoking situations, some of which include: restraint stress (Reed et al., 2013), swim stress (Drugan et al., 2013), chronic variable stress (Mällo et al., 2009), predator odor/exposure (Blanchard et al., 1991; Fendt et al., 2018), social defeat (Kaltwasser, 1990; Tornatzky and Miczek, 1994; Kroes et al., 2007), drug withdrawal (Vivian et al., 1994; Covington and Miczek, 2003; Williams et al., 2012; Berger et al., 2013), and footshock (De Vry et al., 1993; Wöhr et al., 2005). Indeed, 22kHz USV emissions are thought to serve as alarm calls capable of warning conspecifics of possible danger and/or aversive situations (Blanchard et al., 1991; Litvin et al., 2007).

Previous work elucidating the role of natural USVs – as well as recorded USV playback – on neural and behavioral outcomes in exposed rats indicate a role for USVs in inducing affective states of fear and/or anxiety (Kim et al., 2010; Schwarting and Wöhr, 2012; Wöhr and Schwarting, 2013; Brudzynski, 2013; Briefer et al., 2018). Interestingly, rats that display high levels of anxiety-like behavior in an elevated plus maze (EPM) elicit more 22kHz USVs than those exhibiting less anxiety-like behavior (Borta et al., 2006). This affective state can be transferred via USVs to a listening rat, as observed by Saito and colleagues (2016), where positive or negative cognitive bias was induced via presentation of 55kHz or 22kHz USVs (respectively) in rats in an ambiguous stimulus discrimination task. Additionally, rats exposed to 22kHz USVs show a subsequently enhanced acoustic startle reflex (Inagaki and Ushida, 2017), further suggesting transmission of an anxiety-like behavioral state via auditory playback. While much research has been conducted examining USV generation in behavioral paradigms designed to assess anxiety (e.g., Sales, 1991; Borta et al., 2006), little attention has been explicitly paid to the impact of USV playback on subsequent behaviors in these and similar tasks. Notably, to the best of our knowledge there have been no experimental reports directly assessing the behavioral impact of USV playback in well-characterized and widely used anxiety assays such as the elevated zero maze (EZM), and limited reports with regard to the open field task (OFT; Endres et al., 2007; Sadananda et al., 2008). Therefore, additional playback studies are warranted to determine whether 22kHz USV playback is capable of inducing acute anxiety-like responses in rats across multiple behavioral assays.

Studies employing playback of USVs have revealed changes in brain activity in key brain regions associated with anxiety. These studies have reported significant increases in neural activation (assessed via cFos) in brain regions important for emotional valence, including the basolateral amygdala (BLA), periaqueductal grey, and the hippocampus (Sadananda et al., 2008; Ouda et al., 2016). Furthermore, research by Parsana and colleagues (2012) show that single-unit recordings of amygdala neuron activity differ depending on the type of USV playback, with an increased rate of firing associated with 22kHz USVs, and a tonic decrease in firing rate associated with 55kHz USVs. These findings are in line with those detailing cFos expression (Sadananda et al., 2008) and increased dopamine release (Willuhn et al., 2014) in the nucleus accumbens following 55kHz USV playback, further supporting the role of 55kHz-range USVs as appetitive and socially rewarding stimuli. Interestingly, while there have been exhaustive studies looking at cFos activity following USV playback across multiple brain regions (i.e. Sadananda et al., 2008), there have been no reports on the effect of USVs on neural activation within the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), a region that has been implicated in anxiety generation and suppression (Kim et al., 2013). Here, we expand upon the literature to determine the neural effects of both 22kHz and 55kHz USV playback on BNST cFos activity to more fully characterize their ability to induce affective states. In particular, differences in this region may serve an anxiety-specific role – and different stimuli may be dissociable based on their activation of specific BNST nuclei, as well as other brain regions associated with more appetitive states (i.e. the nucleus accumbens).

The ability for USVs to induce both behavioral and neural changes that parallel their social meaning suggest that playback may be a highly useful tool in rodent research. Indeed, it is likely that experimental presentation of a rat-generated 22kHz USV can produce a state of anxiety in a listening animal, thereby providing a model of acute anxiety-like neural and behavioral responses which can be leveraged as a translational rodent model (Jelen et al., 2003; Wöhr and Schwarting, 2013). Therefore, the present set of experiments sought to further characterize the impact of recorded USV playback – particularly within the 22kHz range – in control adults on: 1) anxiety-like behavior in common and well-characterized behavioral assays (EZM and OFT); 2) changes in neural activation in brain regions associated with anxiety; and 3) physiological changes in heart rate during playback, which have previously been shown to be modulated during anxiety-provoking experiences (e.g., Carnevali et al., 2017). In the present set of experiments, we utilized 55kHz USV playback as an ethologically and socially relevant control to compare with results in 22kHz USV playback. Here, we provide evidence suggesting that playback of 22kHz USVs can induce increased anxiety-like behavior, changes in neural activation, and subtle alterations in physiological (heart rate) responses. These data support the role of 22kHz USVs as a mechanism of inducing a transient state of anxiety in rats.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Animals

Throughout all procedures animals were pair-housed with a same sex littermate in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium (22 ± 2°C), with a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700h) with ad libitum access to food and water. Unless otherwise specified within the sections for each separate experiment below, all animals were left undisturbed in their cages except for normal husbandry procedures when not actively being run in an experiment. All experiments were performed in accordance with the 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH) with approval from Northeastern University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Ultrasonic Vocalization Acquisition & Playback

The 22kHz ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) were recorded from an adult male rat using a condenser ultrasonic microphone (Avisoft-Bioacoustics CM16/CMPA; frequency range 2kHz-200kHz) and analyzed using Avisoft-RECORDER USGH Bioacoustics Recording software (Glienick, Germany). To induce 22kHz vocalizations, the emitting rat was restrained in a DecapiCone (Braintree Scientific) and placed in a cage infused with cat urine odor inside a sound-attenuated box with a conspecific rat anesthetized with 0.3 mL/kg ketamine/xylazine to provide an audience effect (Seagraves et al., 2016). The 22kHz USV recording was high-pass filtered with a cut-off frequency of 15kHz and low-pass filtered with a cut-off frequency of 40kHz to reduce the presence of low and high frequency background noise for experimental playback. The recorded length of the 22kHz USVs was 5min, and in all playback studies the entirety of this recording was played on loop, such that during a 10min behavioral assay (i.e. EZM), the animal would hear the USV train in its entirety twice.

The 55kHz USV file used for playback was generously provided to us from Dr. Markus Wöhr from Philipps University (Marburg, Germany), and this was the same 55kHz USV stimuli utilized in previous work (e.g., Wöhr and Schwarting, 2007). Briefly, the 55kHz USV file was ~3.5 sec long containing complex USVs spanning a variety of different USV categories including complex, inverse U, and short (See Wright et al, 2010 for review on USV categories), and was recorded during exploration of a cage containing the scent of a cage mate. For the purpose of the present work, the 55kHz USV playback is used as an important control that is ethologically relevant, yet communicatively distinct to that of 22kHz USVs.

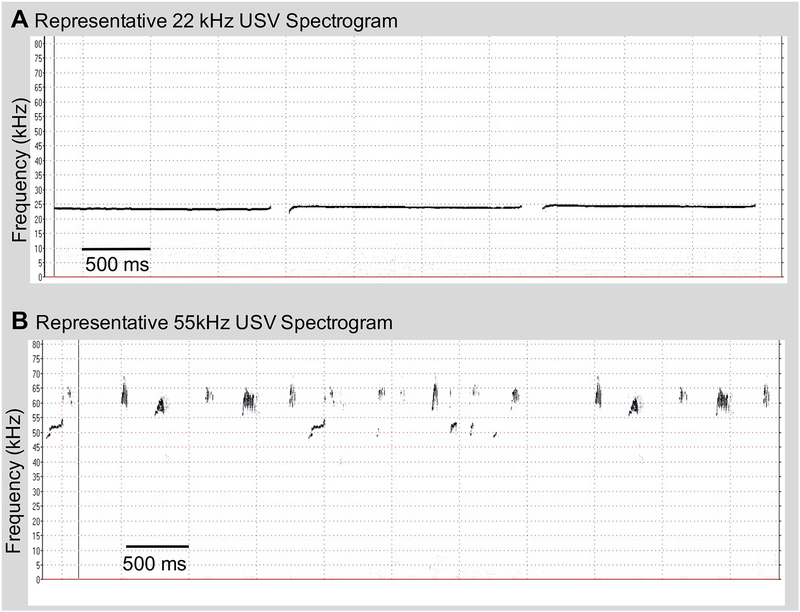

USVs were played back at ~70dB using Avisoft-Bioacoustics portable ultrasonic power amplifier (#70101) and Avisoft-Bioacoustics ultrasonic dynamic speaker (#60108) with a frequency range of ±12dB: 1–120kHz for the duration of the tests described below. Playback of acoustic stimuli was monitored by the UltraSoundGate condenser microphone and sound amplitude was verified using Avisoft-SASLab pro. Prior to playback experiments, sound characteristics (i.e. amplitude, frequency) were evaluated and calibrated via recording at the center of the behavioral assay to ensure equal amplitude across conditions despite distance from the ultrasonic speaker. Representative spectrograms generated by Avisoft software of both the 22kHz aand 55kHz stimuli can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Representative spectrograms of A) 22kHz USV playback, and B) 55kHz USV playback stimuli. These spectrograms show a small portion (approx. 5s) of total playback stimuli.

2.3. Experiment 1: USV-Evoked Changes in Open Field and cFos Expression in cFos-eGFP Rats

2.3.1. Animals & Breeding

Transgenic cFos GFP Long Evans (LE) rats, with the same transgene as the cFos-GFP mice previously described in Barth et al. (2004), were used in Experiment 1. The cFos promotor and the first 4 exons of the cFos transcript were translationally-fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) followed by bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal for sequence termination. A unique advantage of this transgenic rat model is that the GFP signal can be successfully used to identify which neurons were activated during a stimulus presentation. Two hemizygotic LE-Th(cFos-eGFP)2Ottc breeding pairs were purchased from the Rat Resource and Research Center (RRRC; strain #00766; NIDA breeding program) and bred in-house via opposite-sex pair housing for one week to guarantee successful mating. Approximately 3 weeks later, both dams gave birth to litters, with date of birth marked Postnatal Day (PD) 0, and pups and dams were left undisturbed in their cages until offspring genotyping. At PD15, one ~2mm ear punch per pup was collected, with the ear puncher sterilized with 100% EtOH between samples to avoid cross-contamination. Samples were then sent for genotyping (Transnetyx, Inc.) to confirm the presence of the transgene. Rats positive for cFos-eGFP (n=14) were weaned at PD21, housed in same-sex pairs, and left undisturbed until PD60–70, when they were paired with mates from a different litter to make seven new breeding pairs. Rats were bred as described above, with ear punches from subsequent offspring also sent out for genotyping. Offspring positive for cFos-eGFP from these litters were weaned at PD21 and housed in same-sex mixed-litter pairs. For the present study, only male offspring were utilized, with female offspring dedicated to other ongoing studies. Except for normal husbandry, rats were left undisturbed until testing in adulthood (approx. PD100). A total of eighteen male LE transgenic rats were used in Experiment 1 for the Open Field Test (OFT) and subsequent immunohistochemistry analysis, as described below.

2.3.2. Open Field Test (OFT)

For Experiment 1, 18 adult male cFos-eGFP transgenic rats were randomly assigned to one of three stimulus groups: silence, 55kHz USV, or 22kHz USV (n=6/group). On testing day, rats were individually transported into a dimly lit testing room and left undisturbed for 5 minutes to acclimate to the testing environment. For each test, the rat was placed in the same corner of a 100cm × 100cm open field arena facing the wall. Behavior was recorded for 20 minutes via CCTV while the rats were presented with either silence, 55kHz, or 22kHz USV playback for the duration of testing via an elevated ultrasonic speaker (Avisoft Bioacoustics) approximately 30cm away from the arena (therefore maximum distance of the animal from speaker ranged from 30–130cm depending on location within the OFT). Videos were analyzed using EthoVision 9.0 software (Noldus) to determine overall distance traveled (cm), velocity (cm/s), time spent in center (s), and frequency of visits to the 40cm × 40cm center zone. Following testing, rats were returned to their home cage for one hour before euthanasia and tissue collection. It is important to note that these rats were the only cohort tested for cFos immunohistochemistry, as the OFT provided an ideal environment for prolonged (20min) and undisturbed playback with minimal extraneous stimuli.

The first 10 minutes of stimulus presentation in the OFT was used to assess the initial reaction to USV presentation (or silence). Data were initially analyzed in bins of 2 or 5 minutes (data not shown), however since no group differences emerged, the time in the open field is presented for 10 minutes. Since rats were exposed to 20 min of playback, the remaining 10 min in the open field were also recorded, but are presented separately due to a substantial drop in activity following 10 min in all groups. This decrease in activity was likely due to increased habituation to the arena, which has been shown to occur after 5–10 min in a dimly-lit OFT (Mar et al., 2002; Typlt et al., 2013). All dependent measures were subjected to Grubbs’ outlier test, which revealed no significant outliers and thus the findings for all animals are reported.

2.3.3. Tissue Collection and Immunohistochemistry

Perfusion & Tissue Collection:

One hour following the end of USV presentation in the OFT, rats were euthanized with CO2 and transcardially perfused with ice-cold physiological (0.9%) saline followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde fixative solution in 0.1M phosphate buffer with a pH of 7.4. Once fixed, rats were decapitated, and brains were collected, stored in 4% paraformaldehyde solution, and allowed to post-fix for 4 days at 4°C. Brains were then switched to 30% sucrose solution in 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) for cryoprotection at 4°C until ready to section. All brains were sectioned on a freezing microtome (Leica) into 40μm serial coronal sections through the entirety of the brain (excluding olfactory bulbs and cerebellum) and stored in freezing solution at −20°C until immunohistochemical processing.

Immunohistochemistry:

To amplify and increase longevity of the GFP signal in cFos tagged cells of the cFos-eGFP brains, one series of sections from each region of interest (BLA, Auditory Cortex (AU), BNST, Nucleus Accumbens Dorsal Core (AcDC), Nucleus Accumbens Medial Core (AcC), and Nucleus Accumbens Shell (AcS); each section spaced ~240mm apart) were subjected to GFP immunohistochemistry. Free-floating sections were washed 3×15 min in 1x PBS and incubated with blocking buffer (0.3% TritonX-100 PBS with 3% normal donkey serum) for 1.5 hours. They were then incubated in chicken-anti-GFP igY (GFP-1020, Aveslabs) diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer for ~12 hours. The sections were washed 3×15 min in 1x PBS and incubated in donkey anti-chicken Alexa Fluor488 conjugate (703–545–155, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 8 hours, followed by a 3×15 min wash in 1x PBS. For better visualization of the regions of interest, a fluorescent NISSL stain step was added following cFos staining. Sections were incubated in NeuroTrace 530/615 red fluorescent NISSL stain (Invitrogen, N21482) diluted 1:200 in 1x PBS for one hour and then washed 3×15 min in 1x PBS. All aforementioned procedures were done at room temperature. Six slices per region of interest were mounted and coverslipped with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, P36930) for later microscopy.

2.3.4. cFos Imaging and Quantification

Stained sections containing BLA (Bregma −1.72mm to −3.36mm), AU (Bregma −3.48mm to −6.00mm), BNST (Bregma +0.48mm to −1.32mm), and Accumbens regions (Bregma +2.4mm to +1.0mm), were imaged at 20× (AcDc, AcC, AcS), 10x (BLA, AU) or 4x (BNST) magnification using Keyence All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope BZ-X710 (Keyence Corporation of America, USA). Three sections from each region of interest where imaged bilaterally (i.e. 6 images per region; 18 images per animal). Each photomicrograph was analyzed in ImageJ (NIH) for cFos quantification. All images were subjected to the same thresholding and particle analysis parameters (i.e. size and circularity) to ensure consistent quantification across subjects/regions. The number of cFos positive cells in each image was divided by the area of the counted region to determine cFos density. All results were subjected to Grubbs’ outlier test, which revealed one significant outlier in BNST anterodorsal density in the 55kHz stimulus group and one significant outlier in AcDC density in the 22kHz stimulus group, which were therefore excluded from analyses. Nissl-guided delineation of regions of interest were done (with reference to Paxinos and Watson, 1997) to trace each region of interest including the Accumbens, BLA, and BNST, with specific BNST nuclei quantified including the adjacent anterodorsal (anterolateral and anteromedial regions), oval, and fusiform nuclei.

In addition to measuring cFos density in the BLA and BNST, we also examined the average quantification area for each region within each group to control for any discrepancies when outlining these regions for analysis (which would result in inaccurate density measures). This was not necessary for the AU, AcC, AcDC or AcS because the full (i.e. all layers/sampled region) filled the entire 10× or 20× magnification image. No significant differences were observed in area for either of these regions across groups, confirming consistency in quantification across subjects (data shown in Supplementary Figure 1).

2.3.5. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 7 (Graphpad Software) statistical software.

OFT:

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (stimulus x time) was performed to test the main effect of stimulus (silence, 55kHz, 22kHz) on each behavior as well as any change in behavior between the first half and the second half of the OFT. Significant effects were followed up where appropriate with post-hoc Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons tests to determine group differences.

cFos Expression:

A one-way ANOVA was performed to test main effect of stimulus on cFos density for each region of interest (BLA, AU, BNST, and Accumbens subregions). A two-way ANOVA (hemisphere × stimulus) was performed to test effect of stimulus on left AU compared to right AU. Significant effects were followed up where appropriate with post-hoc Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons to determine group differences. Additional one-way ANOVAs were performed to rule out differences in BLA and BNST traced region area between groups, as well as possible differences as a function of hemisphere (where no hemispheric effects were seen, data were collapsed across hemisphere for each subject).

2.4. Experiment 2: USV-Evoked Changes in Elevated Zero Maze

2.4.1. Animals

Twenty-four adult male LE rats (approx. PD80–100, weights 350–450g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Upon arrival, rats were pair-housed and left undisturbed for one week to acclimate to the animal colony before the experiment began.

2.4.2. Elevated Zero Maze (EZM)

Adult male LE rats were randomly assigned to one of three groups: silence, 55kHz or 22kHz USV (n=8/group). EZM was performed on two consecutive days with half of the rats run on each day (4 rats per stimulus group) between the hours of 0800 and 1300h to control for possible circadian effects, with stimulus assignment counterbalanced across testing sessions. Rats were individually transported into a dimly lit testing room in a clean transport cage and left undisturbed for 5 minutes to acclimate to the testing environment. For each test, rats were placed in the same open area facing the closed area. Behavior was recorded for 10 minutes with a CCTV camera placed directly above the EZM, with the assigned USV stimulus (or silence) playing for the duration of testing. Time spent (s) in the open area, and frequency to the open area were calculated in 5 min bins to compare the initial reaction to the stimulus with the final reaction to the stimulus. The ultrasonic speaker (Avisoft Bioacoustics) was elevated and approx. 30 cm away from the arena (therefore at any given time rats could be 30–130cm from the speaker). Videos were analyzed by an experimenter blind to group, with entry into an open area defined as half or more of the rat’s body is in the open arena. Following testing, rats were returned to their home cage.

2.4.3. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 7 (Graphpad Software). A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (stimulus × time) was performed to test the main effect of stimulus on each behavior as well as any change in behavior between the first 5min and the second 5min of the EZM. Significant effects were followed up where appropriate with post-hoc Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons to determine group differences.

2.5. Experiment 3: USV-Evoked Changes in Heart-Rate

2.5.1. Animals & Habituation

Twenty-four adult male LE rats (approx. PD80–100, weights 350–450g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Upon arrival, rats were pair-housed and left undisturbed for one week to acclimate to the animal colony. In order to limit possible artifacts on heart rate variability data based on experimenter handling, and to ensure that the rats were habituated to being in a smaller holding cage for physiological recording, a handling and habituation protocol was implemented as follows: rats were handled for five minutes/day for 7 days to habituate to experimenter contact, which was followed by two days of 5min habituation in the clear plastic recording chamber, and one day of 10min of habituation to the recording chamber, prior to testing day.

2.5.2. Electrocardiogram (ECG) Recording and Analysis

Electrocardiograms (ECGs) were recorded non-invasively using a customized ECGenie apparatus (Mouse Specifics, Inc). To eliminate circadian influences, all ECGs were recorded between 0900h and 1200h over two consecutive days. The ECGenie apparatus was used to record cardiac electrical signals at 2kHz in awake behaving rats by placing the animal in a 20cm × 15cm × 11cm recording chamber that acquires signals through footpad electrodes located on the floor of the box and transmits them to a computer for analysis.

Rats were randomly assigned to one of three groups: silence, 55kHz, or 22kHz USV playback (n=8/group). On test day, each rat was individually transported to the testing room in the ECG recording box and was placed 30cm away from the playback speaker and left undisturbed for a three-minute acclimation period. Following acclimation, ECG signals were recorded during a three-minute baseline period followed by a three-minute test period where they were presented with their assigned stimulus. The recording chamber was cleaned with 40% ethanol solution between each animal. Raw ECG signals were recorded using eMOUSE software (Mouse Specifics, Inc.) and analyzed as reported previously (Chu et al., 2001). ECG signals can be summarized into heart beats, each of which can be segmented into smaller standard waves, depicted as Q, R, S, T. The signal of primary interest was heartrate (HR; BPM) during baseline and test. However, additional cardiac rhythm measures were also analyzed. A representative diagram of normal ECG signals can be seen in Supplemental Figure 2A. Additional parameters analyzed were the time (ms) between subsequent R signals (time between each ventricular blood ejection), QRS complex (ventricular depolarization), ST segment (plateau phase) and QT (total duration of ventricular depolarization and repolarization, and is inversely related to heartrate) which can also be seen in Supplemental Figure 2B–E.

2.5.3. Behavioral Analysis during ECG recordings

In addition to recording ECG signals during baseline and test periods while in the ECG recording box, behavior was recorded via CCTV for later analysis by an experimenter blind to condition. Time spent mobile in the box (index of locomotion) and time spent attending to the stimulus were recorded. Time spent mobile (s) in the box was characterized by the total time spent actively investigating (i.e. general body movement, sniffing, interacting with the enclosure, etc.). Attendance to the stimulus was assessed via the difference in time spent (s) facing the direction of the USV speaker during baseline vs. test playback sessions.

2.5.4. Statistical Analyses

ECG Recordings and Behavior:

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (stimulus × time) was used to test changes in HR, and mobility between baseline and test periods (3 min each). A one-way ANOVA was used to test the change in seconds spent stimulus-oriented to the speaker. Additional ECG (RR, ST, QT, and QRS) signals were analyzed in the same way (Supplemental Figure 2B–E). All significant main effects were followed up with Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Open Field Test

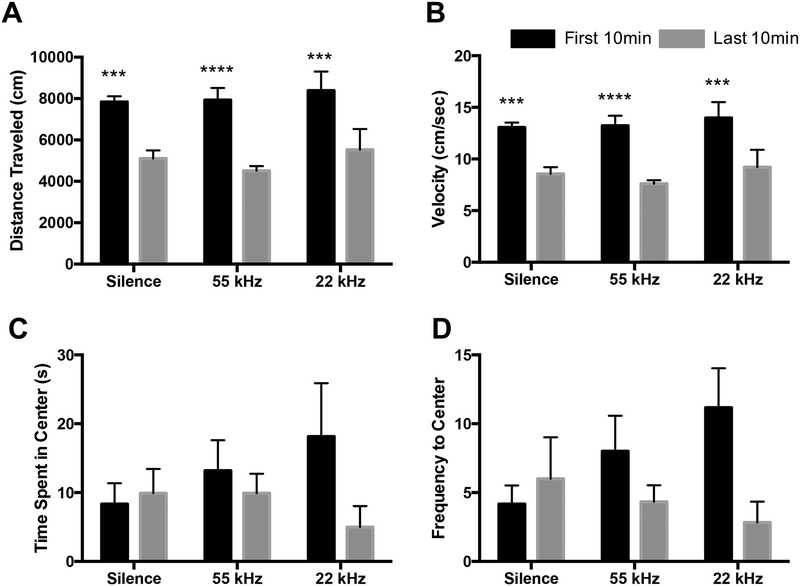

A two-way ANOVA indicated a main effect of time (first 10min vs. last 10min of OFT) on both distance traveled (F1,15 = 91.25, p<0.0001) and velocity (F1,15 = 91.53, p<0.0001). Post-hoc Bonferroni analyses showed a decrease in distance traveled from the first half of the OFT to the second half of the OFT in every group (p<0.001; Figure 2A) as well a decrease in velocity in every group (p<0.001; Figure 2B) suggesting habituation to the environment across all groups (Sestakova et al., 2013). The two-way ANOVA analyses also revealed a trend toward a main effect of time on both seconds spent in the center (F1,15 = 4.17, p=0.058; Figure 2C) as well as frequency of center entries (F1,15 = 4.25, p=0.057; Figure 2D).

Figure 2:

Analysis of anxiety-like behaviors in OFT in response to silence, 22kHz or 55kHz USV playback. A) Distance traveled (cm) during the 20min test decreased from the beginning of the OFT to the end of the OFT in every group. B) Velocity (distance traveled/1200s) decreased from the beginning of the OFT to the end of the OFT in every group. C) While not significant, time spent in the center zone appears to decrease from the beginning of the OFT to the end of the OFT in response to 22 kHz USV playback during last 10min. D) Frequency to the center zone shows a modest (though non-significant) decrease from the beginning of the OFT to the end of the OFT in response to 22 kHz USV playback. Data represent means ± SEM, n=6/group.*** p<0.0005, **** p<0.0001

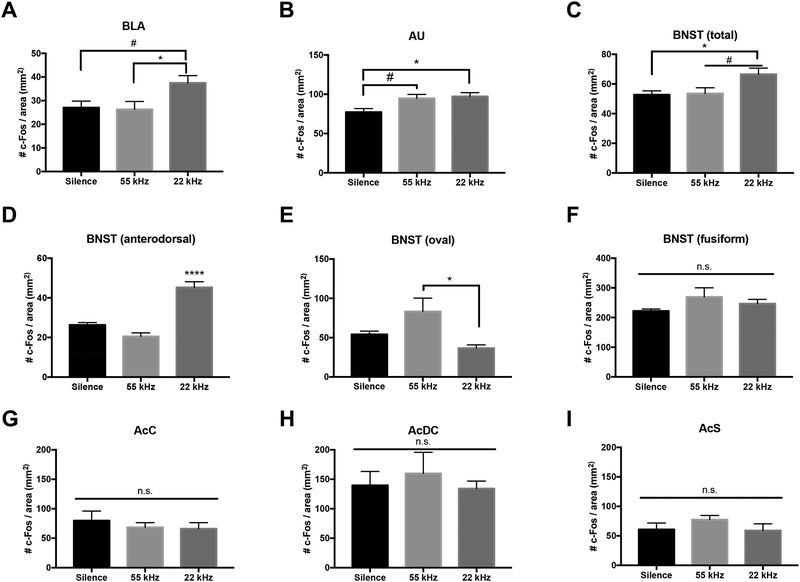

3.1.2. cFos Density

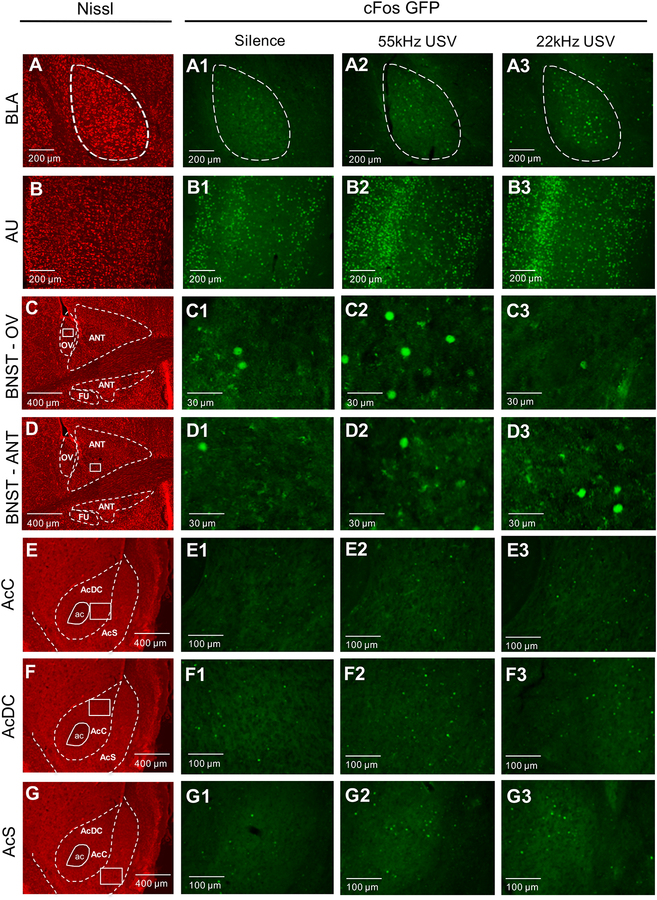

Representative Nissl images of each region of interest can be seen in Figure 3A–G, as well as representative cFos activation in each region in response to each stimulus (Figure 3A1–G3). One-way ANOVA analyses indicated a main effect of stimulus in cFos density in the BLA (F2,15 = 4.18, p=0.03; Figure 4A). BLA cFos+ cell density was significantly increased in rats exposed to 22kHz USVs compared to 55kHz USV playback (p=0.04), with a trend toward a significant increase compared to silence (p=0.058). No significant difference in BLA volume was observed between groups (F2,15 = 0.11, p=0.89; Supplemental Figure 1A).

Figure 3:

Representative images of the BLA, AU, BNST, and Accumbens subregions under different auditory conditions. Nissl images and outlines of the BLA (A) and AU (B) are shown at 10x magnification, with Nissl image of BNST nuclei (C, D), and Accumbens subregions (E, F, G) shown at 4x magnification. To the right of these are corresponding representative images of the BLA, AU, BNST, and Accumbens during playback of either silence (1), 55kHz USV (2), or 22kHz USV (3). See scale bars included in figure for size reference of counted regions.

BNST Abbreviations: OV (oval), ANT (anterodorsal), FU (fusiform).

Accumbens Abbreviations: ac (anterior commissure), AcC (accumbens medial core), AcDC (accumbens dorsal core), AcS (accumbens shell)

Figure 4:

Analysis of cFos expression in the BLA, AU, BNST, AcC, AcDC, and AcS in response to silence, 55kHz USV or 22kHz USV playback during a twenty-minute OFT. A) Density of cFos+ cells in the BLA increased when presented with 22kHz USV playback compared to both silence and 55kHZ USV playback. B) Density of cFos+ cells in the AU increased in response to both 22 and 55kHz USVs when compared to silence. C) Density of cFos+ cells in the BNST is increased in the 22kHz group. D) cFos+ cell density in the BNST anterodorsal nuclei is significantly increased in the 22kHz group compared to both silence and 55kHz. E) cFos+ cell density in the BNST oval nucleus increased in response to 55kHz compared to 22kHz USV presentation. F-I) No differences in cFos+ cell density was seen in the BNST fusiform nucleus, AcC, AcDc, or AcS. Data represent means ± SEM, n=6/group (n=5 in 55kHz group BNST total, BNST anterodorsal analyses, and 22kHz group AcDC). #p<0.06, *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001

Within the AU, a one-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of stimulus on cFos density (F2,15 = 5.19, p=0.01; Figure 4B). Post-hoc Bonferroni analysis of AU indicated that cFos density was significantly increased in rats exposed to 22kHz USVs (p=0.03) and trending an increase in rats exposed to 55kHz USVs (p=0.06) when compared to silence. Additionally, only the left AU showed an effect of stimulus (F2,30 = 5.96, p=0.006), with cFos density increasing in response to 22kHz USVs when compared to silence (p=0.01 in left AU; p=0.09 in right AU), a finding which agrees with previous reports (Sadananda et al., 2008; Supplemental Figure 1B).

One-way ANOVA analysis of cFos+ cell density in the total BNST counted revealed a significant main effect of stimulus (F2,14 = 4.837, p=0.025) with an increase in response to 22kHz USV playback when compared to both silence (p=0.035) and 55kHz USV playback (p=0.06; Figure 4C). Additional analysis within the BNST showed an effect of stimuli in both the anterodorsal nuclei (F2,14 = 38.33, p<0.0001; Figure 4D) and the oval nucleus (F2,15 = 5.143, p=0.019; Figure 4E), but not the fusiform nucleus (F2,15 = 1.447, p=0.266; Figure 4F). Contrasting effects were seen in the anterodorsal nuclei and the oval nucleus. The anterodorsal nuclei showed an increase in cFos+ cell density in response to 22kHz USV playback (p<0.0001) when compared to both silence and 55kHz USVs, while the oval nuclei showed an increase in response to 55kHz USV playback (p=0.018) when compared to 22kHz USVs.

Finally, no significant differences in density were found between stimulus groups in the AcC, AcDc, or AcS (F2,15 = 0.3728, p=0.695; F2,14 = 0.251, p=0.78; F2,15 = 1.048, p=0.375, respectively; Figure 4G–I).

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Elevated Zero Maze

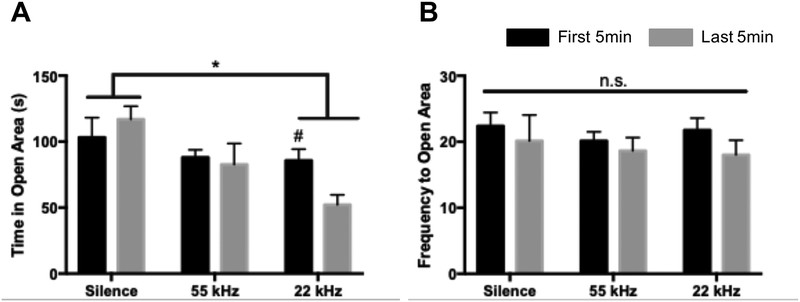

Two-way ANOVA analyses revealed a main effect of stimulus (F2,21 = 5.241, p=0.01) on time spent in the open area of the EZM (Figure 5A). Post-hoc analyses revealed significantly less time spent in the open area when exposed to 22kHz USVs compared to silence (p=0.01). Furthermore, rats in the 22kHz USV group spent less time in open areas during the last five minutes compared to the first five minutes of the test (p=0.05). Additionally, no effect of stimulus (F2,21 = 0.22, p=0.78) or time (F1,21 = 2.58, p=0.12) was found in frequency to the open area of the EZM (Figure 5B).

Figure 5:

Analysis of anxiety-like behaviors during 10min EZM in response to USV playback in first vs. last 5min of testing. A) In general, time (s) spent in the open arena of the EZM in response to 22kHz USVs is significantly less than in response to silence. Time spent in open areas decreased from the first five minutes of the test to the last five minutes of the test in response to 22kHz USVs. B) Frequency to open areas of the EZM does not change as a function of time or stimulus type. Data represent means ± SEM; n=8/group. #p<0.06, *p<0.05

3.3. Experiment 3

3.3.1. ECG recordings & Behavior

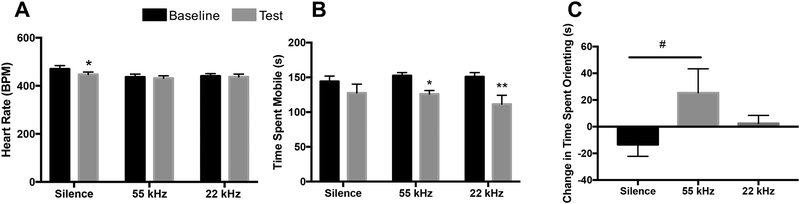

HR analyses revealed a main effect of presentation timeline (F1,21 = 10.20, p=0.004), in addition to a timeline × stimulus interaction (F2,21 = 3.82, p=0.03), with HR decreasing from baseline to test period in the silence group (p=0.001), but not in the 55kHz or 22kHz USV groups (p>0.99; Figure 6A). Similar patterns were detected in QT signals, with an interaction of timeline × stimulus (F2,20 = 4.68, p=0.02), showing an increase in time (ms) between QT signals during stimulus presentation compared to baseline in the silence group (p=0.01), but not in 55kHz or 22kHz USV groups (p>0.99; Supplemental Figure 2B). No significant effects of timeline or stimulus on ST, RR, or QRS ECG signals were identified (Supplemental Figure 2C–E).

Figure 6:

Heart rate and behavioral changes during baseline (3min) and USV playback (3min). A) Heart rate (BPM) decreases only in the silence group from baseline to testing, with no change in 55kHz or 22kHz groups (n=8/group). B) Time (s) spent actively mobile significantly decreased from baseline to test in both the 55kHz and 22kHz groups, with no change seen in the silence group (silence: n=8; 55 and 22kHz USVs: n=7/group) C) Difference in time (s) spent stimulus-oriented toward the speaker from baseline to test/presentation (test(s)-baseline(s); n=8/group). Data represent means ± SEM. #p=0.06; *p<0.05; **p<0.01

Analyses on time spent mobile during ECG recordings show a main effect of time (baseline vs. test; F1,19 = 25.23, p<0.0001) within the testing apparatus (Figure 6B). Rats exposed to 55kHz USV playback and 22kHz USV playback displayed a significant decrease in mobility from baseline to test periods (p=0.039 and p=0.002, respectively). There was a trend toward significance in the change in time spent oriented toward the speaker (stimulus-oriented) during USV playback between stimuli, F2,21 = 2.607, p=0.09), with a notable yet modest increase in time spent stimulus-oriented during playback of 55kHz USVs (p=0.06; Figure 6C).

4. Discussion

The present work provides additional evidence that aversive 22kHz USV playback is capable of inducing an acute state of anxiety in control rats, a finding which is supported by concomitant changes in the BLA and BNST. Importantly, these data are the first to describe 22kHz USV-evoked anxiety-like responses in the EZM, in addition to the first to evaluate the effect of USV playback on BNST cFos activation. Indeed, we describe a robust difference in BNST reactivity to USV playback that suggests a differential role of individual BNST nuclei in processing responses to socially-relevant aversive and appetitive auditory stimuli. The behavioral findings suggesting an increase in anxiety-like behavior in the EZM, paired with the changes seen in BLA and BNST activation, support the ability for 22kHz USV playback to induce an acute state of anxiety.

4.1. 22kHz USVs mediate cFos in brain regions associated with anxiety

The present work demonstrates a role for both 22kHz and 55kHz USVs in mediating cFos density in a region-dependent manner, particularly within anxiety-related brain regions (BLA, BNST). In the BLA, a robust increase in cFos density was observed in response to 22kHz USV playback when compared to both silence and 55kHz USV playback. This finding is supported by previous work indicating that 22kHz, but not 55kHz, USV playback increases overall BLA activation compared to non-social stimuli and/or silence (Ouda et al., 2016; Sadananda et al., 2008). BLA activity has been shown to be indicative of anxiety-like states in the rat (Davis and Whalen, 2001; Vyas et al., 2004; Daskalakis et al., 2014), and therefore this change could be an index of induced anxiety in response to a socially-relevant aversive stimulus. The fact that 55kHz USVs evoked no significant changes in cFos density in comparison to rats exposed to silence further supports this interpretation. Of note, 55kHz USVs did not significantly alter cFos density within any of the quantified regions in the nucleus accumbens. While this is surprising given that previous work with this same stimulus induces approach behavior in listening rats (Wöhr and Schwarting, 2007), it is in line with previous cFos quantification showing no change in accumvens cFos activity following 55kHz playback (Sadananda et al., 2008). It is possible, however, that the stimulus – despite inducing approach behaviors in past work – might not be rewarding enough in and of itself to induce significant changes within the accumbens core or shell. Importantly, it is unlikely that there were fundamental differences in the rats’ ability to perceive the two distinct stimuli that were driving this finding, as both 22kHz and 55kHz USVs showed comparably increased cFos density in the primary AU compared to rats exposed to no stimulus playback.

While the BLA is a well-known and highly studied locus of anxiety-related behavioral states (Tye et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Janak & Tye, 2015; Perusini et al., 2015), the BNST also plays an important role in an organism’s response to anxiety-inducing stimuli (Walker et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2013; Avery et al., 2016). While it has been demonstrated that the BNST nuclei each differentially subserves its highly heterogenous anxiety-regulating functions (Dabrowska et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Gungor and Paré, 2016), there are no reports detailing how the BNST responds to USV playback in the rat. Here, we provide the first report of USV-induced changes in cFos density following both 22kHz and 55kHz USV playback in adult rats. Specifically, our data shows an increase in total BNST cFos density in response to 22kHz USVs compared to both silence and 55kHz USVs; a finding that further supports the capability of 22kHz USVs to induce an anxiety-like state in a listening rat.

In order to understand how this was driven by individual nuclei within the BNST, it was subdivided into 3 regions thought to be involved in anxiety and stress, including: anterodorsal (anterolateral and anteromedial nuclei), oval nucleus, and fusiform nucleus (Daniel and Rainnie, 2016). While no significant differences were found between groups in the fusiform nucleus, the anterodorsal and oval regions showed differential activation patterns. In rats exposed to 22kHz USV playback, a significant increase in cFos density was observed within the anterodorsal region compared to both 55kHz and silent conditions. Conversely, rats exposed to 55kHz USV playback showed a significant increase within the oval nucleus when compared to 22kHz yet was no different to silence. These findings suggest that USV playback – depending on the social relevance – induce opposing patterns of neural activation within the BNST, providing insight into the different roles these nuclei play in moderating both appetitive and anxiety-evoking stimuli. Similarly, Butler and colleagues (2016) found that ferret odor induced increased cFos in the anteromedial nuclei (i.e. anterodorsal), with no changes observed in the oval (which they refer to as the lateral BNST).

Interestingly, past evidence suggests that optogenetic activation of the oval is anxiogenic, whereas activation of the anterodorsal is anxiolytic (Kim et al., 2013). However, it is important to specify that BNST subregions are largely heterogenous with regard to cell type (i.e. CRF, GABA, DA, GLU, etc), and also project to a wide range of brain regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, VTA, etc. (Dong et al., 2001; Larriva-Sahd, 2006; Silberman and Winder, 2013; Partridge et al., 2016), thereby supporting pathways which can either mediate or exacerbate anxiety-like responses. Adding nuance to this narrative, activation of different subtypes of neurons within the BNST lead to dissociable responses, such that activation of GABAergic neurons within the BNST impart anxiolysis, whereas activation of glutamatergic projections from the BNST is anxiogenic (Jennings et al., 2013). Furthermore, within the oval, there is a high concentration of CRF neurons, which are mostly GABAergic (Dabrowska et al., 2013). Although our results do not elucidate on the cell-specific mechanisms by which USV playback is exerting its differential effect, it is possible that the differences in cFos density seen in response to 22kHz and 55kHz playback in the anterodorsal and oval nuclei may be modulated by different cell types. Due to the complexity of the BNST, the specific anxiogenic and/or anxiolytic roles of USV playback within distinct nuclei are difficult to pinpoint without additional cell- and circuit-specific analyses. However, it is clear that the BNST is distinctly sensitive to USVs in the rat, with each vocalization preferentially evoking different neural responses, which we also observed to be reflected in behavior.

Notably, c-fos activation and OFT behavior was assessed in cFos GFP transgenic rats. The advantage of these trangenic rats is that the GFP signal can be used to identify neurons activated during behavior. The current findings suggest that these rats may be used in future studies investigating cellular changes that are specific to the neurons activated during USV presentation. However, we highlight the fact that Long Evans transgenic rats were utilized in Experiment 1, while wild-type Long Evans rats were used in Experiments 2 and 3; we cannot assume that the responses would be identical. Validation studies have previously confirmed the behavioral and physiological similarities between cFos GFP mice and their wild type counterparts (Barth et al., 2004), and the rat line used in the current work has been shown to display typical behavioral responses to stress (Cifani et al., 2012). Therefore the three experiments presented here can be conceptually integrated with the appreciation that they were conducted in different genetic lines.

4.2. Behavioral effects of 22kHz and 55kHz USVs

The present behavioral findings provide evidence that playback of 22kHz USVs – but not 55kHz USVs – induce an acute anxiety-like state in the rat. Two behavioral paradigms (OFT and EZM) were utilized to characterize anxiety-like behaviors in rats in response to USV playback to determine the suitability of 22kHz USV stimuli to instill anxiety in control animals. Previous work suggests that 22kHz USVs decreases overall locomotion in the OFT, while 55kHz USV playback increases locomotion (Wöhr and Schwarting, 2007). However, other groups point to a lack of behavioral effects during USV presentation, with no differences observed in the OFT (Endres et al., 2007). It is important to note here that assays such as the OFT and EZM have limited validity in recapitulating human anxiety, therefore here we used these tasks in conjunction with physiological measures such as neural activation and HR.

Though between-group changes were not seen based on stimulus, this decrease between the first and last 10 min of stimulus presentation on time in – and frequency to – center suggests that the 22kHz USVs induce a differential effect across time. While rats do not initially show an anxiogenic effect of 22kHz presentation in the OFT, our findings suggest that sustained presentation may be capable of inducing anxiety-like behavior. This could be attributed to a variety of factors, including initial novelty of USV playback inducing a moderate increase in time spent in center. There is also evidence suggesting that prior self-eliciting of aversive USVs may be necessary to induce anxiety-like behaviors during playback (Parsana et al., 2012), though our data and research from other groups indicates that this may not actually be needed for anxiety to be induced (Calub et al., 2018).

Our observations with the EZM are the first to show a differential response to the rats’ initial reactions to the 22kHz stimulus compared to a later, secondary response during sustained playback, with rats spending less time in the open areas of the EZM during the last 5min compared to the first 5min during 22kHz playback. This behavioral paradigm showed an overall reduction in the open area time in response to 22kHz USVs when compared to silence, an effect which has also been documented following restraint stress or administration of an anxiogenic drug (Braun et al., 2011). The innate anxiety-provoking effect of the EZM compared to the OFT in control animals might have exacerbated the rats’ responsivity to the 22kHz USVs, making the anxiety-like responses more apparent in this assay. Importantly, this is the first report showing that 22kHz USV playback increases anxiety-like behavior in the EZM in comparison to both silence and 55kHz USVs.

4.3. Effects of USV presentation during ECG recordings

Change in HR is modulation by the sustained regulation of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems. Under resting conditions, the vagal nerve tonically inhibits the parasympathetic nervous system, with low vagal tone associated with increased anxiety in children (El-Sheikh et al., 2001). Thus, successful modulation of the parasympathetic system via the vagal nerve significantly impacts the relationship between HR and anxiety. Here, we show that a decrease in HR from baseline to test only occurs in the group exposed to silence. This decrease in HR is likely a result of decreased physiological arousal, potentially indicating a habituation effect of being in the holding box during the experiment. HR remained unchanged in response to USVs, despite that overall mobility during playback was significantly decreased in both groups compared to baseline. The lack of change in HR in the USV groups is likely indicative of successful activation of the vagal nerve in inhibiting the sympathetic nervous system, with concurrent increased alertness to both stimuli. We hypothesize that this complex modulation would be derailed in rats that exhibit high levels of anxiety following experimental manipulations (i.e. early life adversity, chronic stress, etc.), and would therefore exhibit an increase in HR during aversive USV playback. Rats in the 55kHz condition also show a slight, but notable, increase in time spent stimulus-oriented during playback, which is consistent with an increase in approach behavior in response to an appetitive auditory stimulus (Wöhr and Schwarting, 2007; Sadananda et al., 2008), and may indicate increased attention to the stimulus.

It must be discussed, however, that there are significant limitations that exist with HR analysis. The signals received from the ECG recorder varied extensively between animals during both baseline and test conditions. For example, the range in the number of recorded events over three minutes for each animal was 21–244. Signals are successfully recorded when the rat is on all fours, immobile for at least 3 seconds, and with nothing obstructing the grounding of the ECG electrode pad (i.e. tail movement, urine, stool). Thus, if the animal were to move extensively, groom, defecate, etc., then the signals were difficult to detect. It is likely that this variability may have influenced the ability to interpret the data, and therefore additional research should be done to determine whether USV playback is able to modulate cardiovascular output. Additionally, the decrease in HR in only the silence group from baseline to test could suggest that the initial habituation procedure was insufficient to ameliorate the change in arousal from being held in the small enclosure, which may also explain why baseline HR was ~50BPM higher than has been previously reported for adult rats (Barnard et al., 1976), and might contribute to the lack of change in HR in the USV groups. Importantly, it is worth mentioning that these experiments were conducted in control animals, and that it is likely that rats with pathological anxiety might show differential regulation of HR.

Based on the evidence provided in this manuscript, we suggest that 22kHz USV playback is an effective and ethologically-relevant method of anxiety induction, with the potential to be leveraged to examine differential responses to anxiety in animal models of pathology. We would also like the emphasize that while these results provide compelling additional evidence for the use of USVs to induce acute affective states in rats, future studies are needed to systematically characterize the nuances of different USV frequency ranges and their subsequent effects on brain and behavior. Additionally, systematic manipulation of playback properties (i.e. amplitude changes, frequency modulation, etc.) are still warranted to detail the exact stimulus features that drive social relevance and observed neural and behavioral changes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Markus Wöhr for generously providing the 55kHz USV recordings for use in the present work, and Dr. Thomas G. Hampton of Mouse Specifics for his assistance in the modification and use of his ECGenie system for recording the ECGs for this work. Additionally, we would like to sincerely thank Shayna Peterzell, Kei Inge, Alexa Soares, and Habiba Shaheed for their assistance in collecting and coding behavioral data and Nicholas Tinsley for assistance in USV processing and filtering.

Funding

The research described in this manuscript was supported in part by a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (awarded to JAH), and the National Institutes of Health (5R01MH107556 awarded to HCB).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Adolphs R, The neurobiology of social cognition. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 11 (2) (2001) 231–239. DOI: 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00202-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery SN, Clauss JA, Blackford JU, The human BNST: functional role in anxiety and addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 41 (2016) 128–141. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2015.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard RJ, Corre K, Cho H, Effect of training on the resting heart rate of rats, Eur J Physiol Occup Physiol 35 (4) (1976) 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AL, Gerkin RC, Dean KL, Alteration of neuronal firing properties after in vivo experience in fosGFP transgenic mouse, J Neurosci 24 (2004) 6466–6475. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4737-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AL, Williams AM, McGinnis MM, Walker BM, Affective cue-induced escalation of alcohol self-administration and increased 22-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations during alcohol withdrawal: Role of kappa-opioid receptors, Neuropsychopharmacology 38 (4) (2013) 647–654. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2012.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC, Agullana R, Weiss SM, Twenty-two kHz alarm cries to presentation of a predator, by laboratory rats living in visible burrow systems, Physiol Beh 50 (5) (1991) 967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borta A, Wöhr M, Schwarting RKW, Rat ultrasonic vocalization in aversive situations and the role of individual differences in anxiety-related behavior, Behav Brain Res 166 (2006) 271–280 DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AA, Skelton MR, Vorhees CV, Williams MT, Comparison of the elevated plus and elevated zero mazes in treated and untreated male Sprague-Dawley rats: Effects of anxiolytic and anxiogenic agents, Pharmacol Biochem Behav 97 (3) (2011) 406–415. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briefer EF, Vocal contagion of emotions in non-human animals, Proc Biol Sci, 285 (1873) DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2017.2783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski SM, Chiu EMC, Behavioural responses of laboratory rats to playback of 22 kHz ultrasonic calls, Physiol Behav 57 (6) (1995) 1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski SM, Principles of rat communication: Quantitiative parameters of ultrasonic calls in rats, Behav Genet 35 (2005) 85–92. DOI: 10.1007/s10519-004-0858-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski SM, Communication of adult rats by ultrasonic vocalization: Biological, sociobiological, and neuroscience approaches, ILAR J 50 (2009) 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski SM, Ethotransmission: Communication of emotional states through ultrasonic vocalization in rats, Curr Opin Neurobiol, 23 (3) (2013) 310–317. DOI: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J, Kroes RA, Moskal JR, Pfaus JG, Brudzynski SM, Panksepp J, Ultrasonic vocalizations of rats (Rattus norvegicus) during mating, play, and aggression: Behavioral concomitants, relationships to reward, and self-administration of playback, J Comp Psychol 122 (4) (2008) 357–367. DOI: 10.1037/a0012889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CJ, Kisko TM, Swiftwolfe H, Pellis SM, Euston DR, Specific 50-kHz vocalizations are tightly linked to particular types of behavior in juvenile rats anticipating play, PloS One 12 (5) (2017) e0175841 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RK, Oliver EM, Sharko AC, Parilla-Carrero J, Kaigler KF, Fadel JR, Wilson MA, Activation of corticotropin releasing factor-containing neurons in the rat central amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis following exposure to two different anxiogenic stressors, Behav Brain Res 304 (2016) 92–101. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.01.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calub CA, Furtak SC, Brown TH, Revisiting the autoconditioning hypothesis for acquired reactivity to ultrasonic alarm calls, Physiol Behav 194 (2018) 380–386. DOI: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevali L, Montano N, Statello R, Coudé G, Vacondio F, Rivara S, Ferrari PF, Sgoifo A, Social stress contagion in rats: Behavioural, autonomic and neuroendocrine correlates, Psychoneuroendocrinology 82 (2017) 155–163. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu V, Oter JM, Lopez O, Morgan JP, Amende I, Hampton TG, Method for non-invasively recording electrocardiograms in conscious mice, BMC Physiol 1:6(2001) PMC35354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifani C, Koya E, Navarre BM, Calu DJ, Baumann MH, Marchant NJ, Liu Q-R, Khuc T, Pickel J, Lupica CR, Shaham Y, Hope BT, Medial prefrontal cortex neuronal activation and synaptic alterations after stress-induced reinstatement of palatable food seeking: A study using c-fos-GFP transgenic female rats, J Neurosci 32 (25) (2012) 8480–8490. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5895-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE 3rd, Miczek KA, Vocalizations during withdrawal from opiates and cocaine: Possible expressions of affective distress, Eur J Pharamcol 467 (1–3) (2003) 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska J, Hazra R, Guo JD, Dewitt S, Rainnie DG, Central CRF neurons are not created equal: phenotypic differences in CRF-containing neurons of the rat periventricular hypothalamus and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, Front Neurosci 7:156(2013) DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel SE, Rainnie DG, Stress modulation of opposing circuits in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, Neuropsychopharmacology 41 (2016) 103–125. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2015.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis NP, Diamantopoulou A, Claessens SE, Remmers E, Tjälve M, Oitzl MS, Champagne DL, de Kloet ER, Early experience of a novel-environment in isolation primes a fearful phenotype characterized by persistent amygdala activation, Psychoneuroendocrinology 39 (2014) 39–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Whalen PJ, The amygdala: vigilance and emotion, Mol Psychiatry 6 (2001) 13–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J, Benz U, Schreiber R, Traber J, Shock-induced ultrasonic vocalization in young adult rats: A model for testing putative anti-anxiety drugs, Eur J Pharmacol 249 (3) (1993) 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Petrovich GD, Watts AG, Swanson LW, Basic organization of projections from the oval and fusiform nuclei on the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in adult rat brain, J Comp Neurol 436 (4) (2001) 430–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drugan RC, Christianson JP, Warner TA, Kent S, Resilience in shock and swim stress models of depression, Front Behav Neurosci 7:14(2013) DOI: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger JA, Whitson SM, Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment of physical health: the moderating role of vagal tone, Child Dev 72 (6) (2001) 1617–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres T, Widmann K, Fendt M, Are rats predisposed to learn 22 kHz calls as danger-predicting signals? Behav Brain Res 185 (2) (2007) 69–75. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt M, Brosch M, Wernecke KEA, Willadsen M, Wöhr M, Predator odour but not TMT induces 22-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations in rats that lead to defensive behaviours in conspecifics upon replay, Sci Rep 8 (2018) 11041 DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-28927-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gump BB, Kulik JA, Stress, affiliation, and emotional contagion, J Pers Soc Psychol 72 (2) (1997) 305–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gungor NZ, Paré D, Functional heterogeneity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, J Neurosci 31 (2016) 8038–8049. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0856-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JS, Bird GC, Li W, Jones J, Neugebauer V, Computerized analysis of audible and ultrasonic vocalizations of rats as a strandardized measure of pain-related behavior, Journal of Neuroscience Methods 141 (2) (2005) 261–269. DOI: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki H, Ushida T, Changes in acoustic startle reflex in rats induced by playback of 22-kHz calls, Physiol Behav 169 (2017) 198–194. DOI: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janak PH, Tye KM, From circuits to behavior, Nature 517 (2015) 284–292. DOI: 10.1038/nature14188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelen P, Soltysik S, Zagrodzka J, 22-kHz ultrasonic vocalization in rats as an index of anxiety but not fear: behavioral and pharmacological modulation of affective state, Behav Brain Res 141 (2003) 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JH, Sparta DR, Stamatakis AM, Ung RL, Kash TL, Stuber GD, Distinct extended amygdala circuits for divergent motivational states, Nature 496 (7444) (2013) 224–228. DOI: 10.1038/nature12041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan D, Ardid D, Chapuy E, Eschalier A, Le Bars D, Audible and ultrasonic vocalization elicited by a single electrical nociceptive stimuli to the tail in the rat, PAIN 63 (2) (1995) 237–249. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00049-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltwasser MT, Acoustic signaling in the black rat (Rattus rattus), J Comp Psychol 104 (3) (1990) 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Kim ES, Covey E, Kim JJ, Social transmission of fear in rats: The role of 22-kHz ultrasonic distress vocalization, PLoS One 5 (12) (2010) e15077 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Adhikari A, Lee SY, Marshel JH, Kim CK, Mallory CS, Lo M, Mattis J, Lim BK, Malenka RC, Warden MR, Neve R, Tye KM, Desisseroth K, Diverging neural pathways assemble a behavioural state from separable feature in anxiety, Nature 496 (7444) (2013) 219–223. DOI: 10.1038/nature12018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisko TM, Wöhr M, Pellis VC, Pellis SM, From play to aggression: High-frequency 50-kHz vocalizations as play and appeasement signals in rats, Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 30 (2017) 91–108. DOI: 10.1007/7854_2015_432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Burgdorf J, Panksepp J, Ultrasonic vocalizations as indices of affective states in rats, Psychol Bull 128 (6) (2002) 961–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes RA, Burgdorf J, Otto NJ, Panksepp J, Moskal JR, Social defeat, a paradigm of depression in rats that elicits 22-kHz vocalizations, preferentially activates the cholinergic signaling pathway in the periaqueductal gray, Behav Brain Res 182 (2) (2007) 290–300. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larriva-Sahd J, Histological and cytological study of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis in adult rat. II. Oval nucleus extrinsic inputs, cell types, neuropil, and neuronal modules, J Comp Neurol 497 (2006) 772–807. DOI: 10.1002/cne.21011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvin Y, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ, Rat 22kHz ultrasonic vocalizations are alarm cries, Behav Brain Res, 182 (2) (2007) 166–172. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mällo T, Matrov D, Kõiv K, Harro J, Effect of chronic stress on behavior and cerebral oxidative metabolism in rats with high or low positive affect, Neuroscience 164 (3) (2009) 963–974. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar A, Spreemeester E, Rochford J, Fluoxetine-induced increases in open-field habituation in the olfactory bulbectomized rat depend on test aversiveness but not on anxiety, Pharmacol Biochem Behav 73 (3) (2002) 703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouda L, Jílek M, Syka J, Expression of c-Fos in rat auditory and limbic systems following 22-kHz calls, Behav Brain Res 308 (2016) 196–204. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J, Burgdorf J, “Laughing” rats and the evolutionary antecedent sof human joy? Physiology & Behavior 79 (3) (2003) 533–547. DOI: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00159-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsana AJ, Li N, Brown TH, Positive and negative ultrasonic social signals elicit opposing firing patterns in rat amygdala, Behav Brain Res 226 (2012) 77–86. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge JG, Forcelli PA, Luo R, Cashdan JM, Schulkin J, Valentino RJ, Vicini S, Stress increases GABAergic neurotransmission in CRF neurons of the central amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, Neuropharmacology 107 (2016) 239–250. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C, The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, Academic Press, New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Perusini JN, Fanselow MS, Neurobehavioral perspectives on the distinction between fear and anxiety, Learn Mem 22 (2015) 417–425. DOI: /10.1101/lm.039180.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MD, Pira AS, Febo M, Behavioral effects of acclimatization to restraint protocol used for awake animal imaging, J Neurosci Methods 217 (1–2) (2013) 63–66. DOI: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadananda M, Wöhr M, Schwarting RKW, Playback of 22-kHz and 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations induces differential c-fos expression in the rat brain, Neurosci Lett 435 (2008) 17–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Yuki S, Seki Y, Kagawa H, Okanoya K, Cognitive bias in rats evoked by ultrasonic vocalizations suggests emotional contagion, Behav Processes 132 (2016) 5–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales GD, The effect of 22 kHz calls and artificial 38 kHz signals on activity in rats, Behav Processes 24 (2) (1991) 83–93. DOI: 10.1016/0376-6357(91)90001-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting RKW, Wöhr M, On the relationships between ultrasonic calling and anxiety-related behavior in rats, Braz J Med Biol Res 45 (4) (2012) 337–348. DOI: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seagraves KM, Arthur BJ, Egnor SE, Evidence for an audience effect in mice: male social partners alter the male vocal response to female cues, J Exp Biol 219 (10) (2016) 1437–1448. DOI: 10.1242/jeb.129361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seffer D, Schwarting RK, Wöhr M, Pro-social ultrasonic communication in rats: Insights from playback studies, J Neurosci Methods 234 (2014) 73–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestakova N, Puzserova A, Kluknavksy M, Bernatova I, Determination of motor activity and anxiety-related behavior in rodents: methodological aspects and role of nitric oxide, Interdiscip Toicol 6 (3) (2013) 126–135. DOI: 10.2478/intox-2013-0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberman Y, Winder DG, Emerging role for corticotropin releasing factor signaling in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis at the intersection of stress and reward, Front Psychiatry 29 (2013) 4:42. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky W, Miczek KA, Behavioral and autonomic responses to intermittent social stress: Differential protection by clonidine and metoprolol, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 116 (3) (1994) 346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye KM, Prakash Rl, Kim SY, Fenno LE, Grosenick L, Karabi H, Thompson KR, Gradinaru V, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Amygdala circuitry mediating reversible and bidirectional control of anxiety, Nature 471 (2011) 358–362. DOI: 10.1038/nature09820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Typlt M, Mirkowski M, Azzopardi E, Ruth P, Pilz PK, Schmid S, Habituation of reflextive and motivated behavior in mice with deficient BK channel function, Front Integr Neurosci 19 (2013) 7:19. DOI: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A, Pillai AG, Chattarii S, Recovery after chronic stress fails to reverse amygdaloid neuronal hypertrophy and enhanced anxiety-like behavior, Neuroscience 128 (4) (2004) 667–673. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivian JA, Farrell WJ, Sapperstein SB, Miczek KA, Diazepam withdrawal: Effects of diazepam and gepirone on acoustic startle-induced 22kHz ultrasonic vocalizations, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 114 (1994) 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Toufexis DJ, Davis M, Role of the bed neucleus of the stria terminalis versus the amygdala in fear, stress and anxiety, Eur J Pharmacol 463(1–3) (2003) 199–216. DOI: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01282-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DV, Wang F, Liu J, Zhang L, Wang Z, Lin L, Neurons in the amygdala with response-selectivity for anxiety in two ethologically based tests. PLoS One 6 (4) (2011) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild B, Erb M, Bartels M, Are emotions contagious? Evoked emotions while viewing emotionally expressive faces: quality, quantity, time course and gender differences, Psychiatry Res 102 (2) (2001) 109–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AM, Reis DJ, Powell AS, Neira LJ, Nealey KA, Ziegler CE, Kloss ND, Bilimoria JL, Smith CE, Walker BM, The effect of intermittent alcohol vapor or pulsatile heroin on somatic and negative affective indices during spontaneous withdrawal in Wistar rats, Psychopharmacology (Berl) 223 (2012) 75–88. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-012-2691-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willuhn I, Tose A, Wanat MJ, Hart AS, Hollon NG, Phillips PE, Schwarting RK, Wöhr M, Phasic dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in response to pro-social 50 kHz vocalizations in rats, J Neurosci 34 (32) (2014) 10616–10623. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1060-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöhr M, Borta A, Schwarting RKW, Overt behavior and ultrasonic vocalization in a fear conditioning paradigm: A dose-response study in the rat, Neurobiol Learn Mem 84 (3) (2005) 228–240. DOI: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöhr M, Schwarting RK, Ultrasonic communication in rats: can playback of 50-kHz calls induce approach behavior? PLoS One 2 (12) (2007) e.1365 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöhr M, Houx B, Schwarting RKW, Spruijt B, Effects of experience and context on 50-kHz vocalizations in rats, Physiology & Behavior 93 (4–5) (2008) 766–776. DOI: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöhr M, Schwarting RKW, Affective communication in rodents: Ultrasonic vocalizations as a tool for research on emotion and motivation, Cell Tissue Res 354 (2013) 81–97. DOI 10.1007/s00441-013-1607-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JM, Gourdon JC, Clarke PBS, Identification of multiple call categories within the rich repertoire of adult rat 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations: effects of amphetamine and social context, Psychopharmacology 211 (2010) 1–13. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-010-1859-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.