Abstract

Removal of introns by pre-mRNA splicing is fundamental to gene function in eukaryotes. However, understanding the mechanism by which exon-intron boundaries are defined remains a challenging endeavor. Published reports support that the recruitment of U1 snRNP at the 5′ss marked by GU dinucleotides defines the 5′ss as well as facilitates 3′ss recognition through cross-exon interactions. However, exceptions to this rule exist as U1 snRNP recruited away from the 5′ss retains the capability to define the splice site, where the cleavage takes place. Independent reports employing exon 7 of Survival Motor Neuron (SMN) genes suggest a long-distance effect of U1 snRNP on splice site selection upon U1 snRNP recruitment at target sequences with or without GU dinucleotides. These findings underscore that sequences distinct from the 5′ss may also impact exon definition if U1 snRNP is recruited to them through partial complementarity with the U1 snRNA. In this review we discuss the expanded role of U1 snRNP in splice-site selection due to U1 ability to be recruited at more sites than predicted solely based on GU dinucleotides.

Keywords: U1 snRNP, splicing, cryptic splice site, ISS-N1, SMN, SMA

1. Introduction

Pre-mRNA splicing is an essential process by which non-coding (intronic) sequences are removed and coding (exonic) sequences are ligated to produce mRNAs in all eukaryotes [1]. Process of pre-mRNA splicing is also central to the generation of non-coding RNAs and circular RNAs (circRNAs) [2-4]. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing expands the coding potential of eukaryotic genomes by producing a vast repertoire of transcripts, both linear and circular, from a single gene. Pre-mRNA splicing requires accurate recognition of the 5′ and 3′ splice sites (5′ss and 3′ss) that mark the beginning and the end on an intron, respectively [4-6]. An adenosine residue generally located between 20 and 50 nucleotides (nts) upstream of the 3′ss serves as the branchpoint that initiates the catalysis of pre-mRNA splicing [7]. The mechanism of pre-mRNA splicing bears striking similarity to group II intron self-splicing in lower organisms [1,8]. Both pre-mRNA and group II introns are removed by two RNA-catalyzed transesterification steps. The first transesterification step cleaves the phosphodiester bond at the 5′ss and generates an intermediate lariat molecule by joining the 5′-end of the cleaved intron to a 2′-hydroxyl group of an adenosine residue at the branchpoint [1,8]. The second transesterification step employs the freed 3′-hydroxyl group of the 5′ exon to cleave the phosphodiester bond at the downstream intron-exon junction and ligate the 5′ exon with the 3′ exon releasing an intron in its lariat form [8]. While RNA structure alone is sufficient to drive both transesterification steps in case of group II intron splicing, factors recruited away from the splice sites can influence splicing reactions [8,9]. In case of pre-mRNA splicing, participation of the spliceosome, a macromolecular machine, is essential for intron removal [10,11]. Core components of the spliceosome include five uridine-rich small ribonucleoproteins (U snRNPs), namely U1, U2, U4, U5 and U6 snRNPs [10]. Additional proteins not associated with U snRNPs also play an important role in splicing, constitutive and alternative [12]. An early study using HeLa cells revealed that U1 snRNP is produced in much higher amount than other snRNPs [13], suggesting the role of this snRNP in processes other than pre-mRNA splicing. Consistently, U1 snRNP has been implicated in polyadenylation, 3′-end processing, telescripting and transcription [14-19].

All mammalian genes with more than two exons are alternatively spliced [20]. However, rules of how the splice sites of an alternative exon are defined remain elusive. There is a growing appreciation of the role of pre-mRNA context in defining exon boundaries [21-23]. Splicing regulatory information within pre-mRNA includes but is not limited to positioning and accessibility of multiple overlapping cis-elements [24-26]. RNA structures and long-distance interactions bring an additional layer of complexity to the context-specific regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing [27-32]. In this review, we focus on a very important but less appreciated role of U1 snRNP in splice site selection from a distance. This review is inspired by recent studies employing engineered U1 (eU1) snRNPs that modulate splicing by annealing to sequences away from the 5′ splice sites [33-39]. All eU1s described here harbor mutations (base substitutions) within their 5′-ends, which enable their annealing to the intended target sequences within pre-mRNAs.

2. Components of U1 snRNP

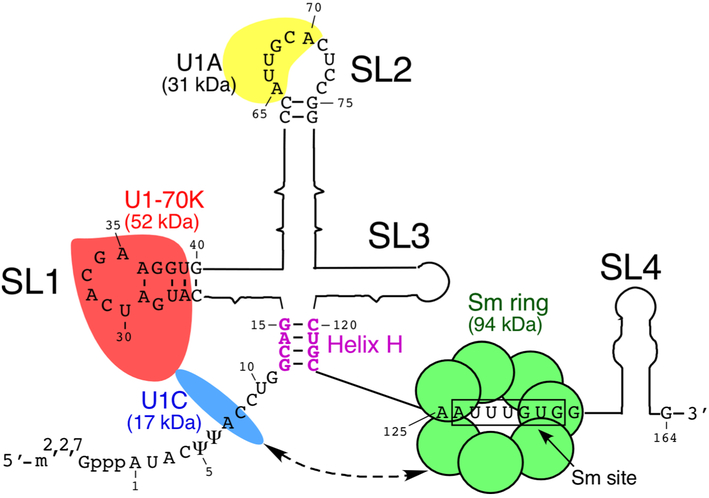

Human U1 snRNP consists of a U-rich non-coding RNA, which is 164 nt-long, Sm proteins that are common between all U-rich snRNPs and three U1-specific proteins, U1A, U1C and U1-70K (Fig. 1) [40]. Seven Sm proteins form a ring-like structure around the so-called Sm site (Fig. 1) [41]. Assembly of the Sm proteins on U1 snRNA takes place in the cytoplasm, while loading of U1A and U1-70K on U1 snRNA happens in the nucleus [40]. U1C does not bind U1 snRNA directly, instead it is recruited to U1 snRNP complex through protein:protein interactions [42,43]. Several U1 snRNP proteins are posttranslationally modified, [40]. The significance of these modifications is unclear, but they might affect protein:protein interactions and change the splicing activity of U1 snRNP. RNA component of U1 snRNP is modified as well. For example, U at positions +5 and +6 are converted to pseudouridines (ψ) (Fig. 1) [44]. The presence of these pseudouridines is thought to contribute to the local RNA structure as well as base pairing with the 5′ss of exons [40].

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of human U1 snRNP. U1 snRNP is composed of one U1 snRNA, seven common Sm proteins and three U1 snRNP-specific proteins (U1-70K, U1A and U1C) [49]. The 5′ end of U1 snRNA is tri-methyl-guanosine-capped. ψ indicates post transcriptional modification, pseudo-Uridine. Secondary structure of U1 snRNA consists of four stem-loops (SL) and an H helix highlighted in purple. Nucleotides forming H helix are shown. In addition, U1 snRNA sequences relevant to RNA:protein or RNA:5′ss interactions are given as well [42]. The loop portion of SL1 is drawn according to the crystal structure described in [42]. It is closed by a trans WC/Hoogsteen base pair formed between A29 and A36 [42]. Protein components of U1 snRNP, their sizes and their approximate locations are shown as well [49]. The Sm ring formed by the Sm proteins shown as green circles bind to the Sm site, which is boxed. U1-70K shown in red recognizes SL1. U1A shown in yellow binds SL2. U1C shown in blue is recruited to U1 snRNP through protein:protein interactions with U1-70 K and Sm proteins. The broken arrow signifies interactions between U1C and Sm ring.

U1 snRNA folds to form four stem-loops and a short helix, helix H (Fig. 1). The first stem-loop (SL1) is bound by U1-70K, the second stem-loop (SL2) by U1A and the third stem-loop (SL3) makes extensive contacts with the Sm ring [45-49]. The fourth stem-loop (SL4) contacts SF3A1, a component of U2 snRNP [50]. There are 30 functional U1 genes [51], although their significance is not fully understood. The first crystal structure of the functional core of U1 snRNP was reported in 2009 [52]; a higher resolution crystal structure of U1 snRNP was published in 2015 [42]. One of the interesting outcomes from this study is that U1C does not recognize the 5′ss in a sequence-specific manner, independently of U1 snRNA, as previously proposed [53]. Instead, it stabilizes the U1 snRNA:5′ss duplex through hydrogen bonds with the sugar-phosphate backbone [42]. Of note, prevailing differences in register of base pairing between the 5′ss and the 5′-end of U1 snRNA suggest lack of any strict rules by which U1 snRNP defines the 5′ss of an exon in humans [54,55]. A change in register may create a break or a bulge in the U1 snRNA:5′ss duplex [55]. Based on the crystal structure published in 2015, it is proposed that U1C may stabilize mismatched base pairing (or bulge) within the U1 snRNA:5′ss duplex [42]. However, it is not known if U1C may also stabilize a discontinuous (or broken) U1 snRNA:5′ss duplex.

In addition to the spliceosome, U1 snRNP is detected in the supraspliceosome, a high-order pre-assembled macromolecular complex comprised of four spliceosomes, each containing all five U snRNPs [56,57]. Other RNA:protein complexes associated with transcription and/or transcription-coupled events also harbor U1 snRNP [58-61]. The idea that U1 snRNP recognizes the 5′ss through base pairing was first put forward in 1980 [62,63], and experimentally validated in 1986 [64]. Subsequent studies supported the hypothesis that base-pairing interactions between the 5′ss and the 5′-end of U1 snRNA is critical for the early events in pre-mRNA splicing, although there are enough evidence to support that the recognition of the 5′ss can occur without the involvement of U1 snRNP [40]. As per prevailing model, recruitment of U1 snRNP at the 5′ss triggers step-wise assembly of the spliceosome, which undergoes massive remodeling to become catalytically active [65]. In specific contexts, auxiliary factors, such as TIA1, TIAR (TIAL), SFPQ (PSF), p54(nrb) are known to facilitate recruitment of U1 snRNP at the 5′ss of exons [66-69].

3. Role of U1 snRNP in splice site selection from a distance

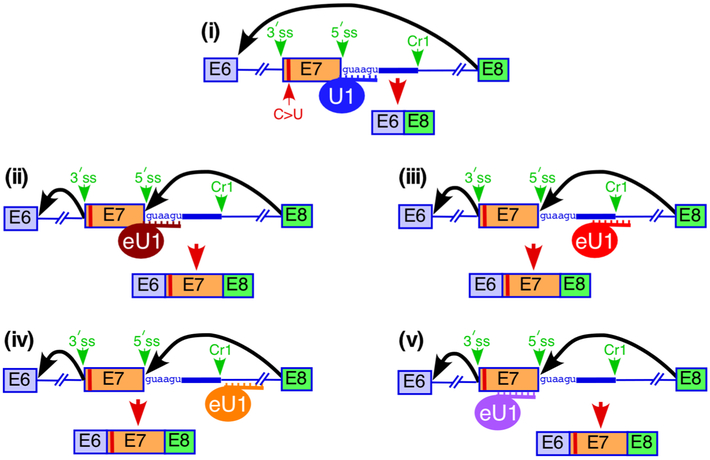

In the late 80s several reports indicated that so called compensatory/suppressor U1 snRNAs designed to rescue defective splicing by forming perfect complementarity with the mutated 5′ss sites due to compensatory mutations introduced within the 5′-end of U1 snRNA, activated cleavage outside of their annealing area in yeast system (70-73). Later, somewhat similar observations were made in mammalian system. Here, exon inclusion through usage of a mutated authentic 5′ss was rescued by U1 snRNAs designed to base pair to sequences located downstream and sometimes upstream of this site. These engineered U1 snRNAs (eU1s) were called shift U1 snRNAs. The property of a shift U1 snRNP to modulate splicing from a distance was first reported about a quarter century ago in the context of a minigene expressed in human 293 cells [74]. The study employed a panel of shift U1s that induced usage of a weak 5′ss of an exon of the H-ras gene upon annealing to sequences upstream or downstream of this splice site [74]. Subsequent studies employing eUs, which were also called exon-specific U1s (ExSpeU1s), showed that these eU1s promoted inclusion of different exons through usage of authentic 5′ss in the contexts of exonic/intronic mutations that induced exon skipping associated with a number of human diseases. For example, eU1s targeting different intronic sequences downstream of the 5′ss of SPINKS exon 11 that carried the most frequent mutation found in Netherton syndrome patients of European origin, rescued inclusion of this exon [34]. Similarly, targeting of intronic sequences downstream of Survival Motor Neuron 2 (SMN2) exon 7, skipping of which is linked to Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), promoted exon 7 inclusion [33,35,36] (Fig. 2). In another example, a set of eU1s annealing to a broad region from position −7 to position +63 relative to exon/intron junction of the coagulation factor IX exon 5 were shown to promote its inclusion in the context of the mutated 5′ss linked to haemophilia B [37]. It has also been shown that overexpression of eU1, which annealed to an intronic region located 10 nts downstream of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator exon 12 caused a significant increase in exon inclusion from near complete skipping to 70 % in the context of the mutated 5′ss associated with cystic fibrosis [33]. In the context of another pathological mutation at the 5′ss of ELP1 exon 20, a panel of eU1s targeting an intronic region from position +4 to +81 relative to exon/intron junction rescued exon 20 splicing [38]. Of note, this 5′ss mutation in both alleles of ELP1 gene is found in more than 99% of patients with Familial dysautonomia [38]. Finally, eU1s targeting an intronic region downstream of the authentic 5′ss caused some increase in Phenylalanine Hydroxylase exon 11 inclusion in the context of two pathological intronic mutations associated with Phenylketonuria [39]. It should be noted that for some eU1, the therapeutic potential of rescuing exon inclusion was subsequently confirmed in mouse models [35,37,38]. Here we focus on exon 7 of SMN supporting the role of U1 snRNP in splice site selection from a distance. We chose SMN exon 7 due to the vast repertoire of cis-elements, including structural elements, implicated in regulation of splicing of this exon. Findings from recent studies provide novel insights into a potential role of endogenous U1 snRNP in exon definition from a distance.

Fig. 2.

Diagrammatic representation of the splice site selection from a distance in an SMN2 exon 7 model system. Three eU1s indicated in different colors were designed to form maximum possible number of base pairs with their intended targets. Sizes of exons and introns and the relative positioning of the splice sites are not to the scale. Cr1 refers to the cryptic 5′ss located 23 nts downstream of the authentic 5′ss of exon 7 [36]. Splice sites and Cr1 are indicated by green arrows. Black arrows represent the major splicing events. Red arrows represent splicing events with the major splice products shown. C>U refers to C-to-U transition at the 6th exonic position that distinguishes SMN2 from SMN1. (i) Overexpression of wild type U1 snRNA shown in blue is unable to rescue exon 7 inclusion. eU1s annealing to the authentic 5′ss of exon 7 (ii), to the Cr1 site (iii), as well as upstream (iv) and downstream (v) of Cr1, promote SMN2 exon 7 inclusion through activation of the authentic 5′ss. Models are based on results reported in [36].

3.1. Poor accessibility renders the 5′ss of SMN exon 7 suboptimal

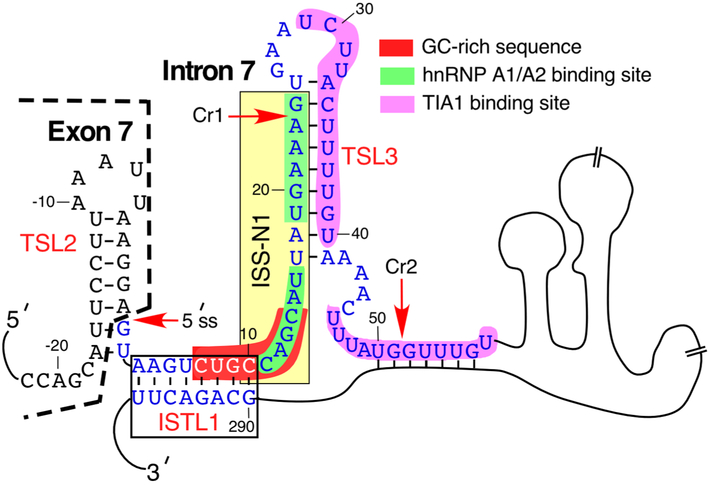

Humans carry two nearly identical copies of SMN gene: SMN1 and SMN2 [75]. Low levels of SMN due to deletions or mutations of SMN1 cause SMA, one of the leading genetic diseases of children and infants [75]. SMN is an essential protein involved in most if not all aspects of RNA metabolism, including snRNP biogenesis, transcription, splicing, translation, stress granule formation and mRNA RNA trafficking [76]. SMN2 does not compensate for the loss of SMN1 due to predominant skipping of exon 7 [75,77,78]. Considering SMN2 is universally present in SMA patients, strategies aimed at the correction of SMN2 exon 7 splicing remain one of the promising avenues for the treatment of SMA [79-81]. While a C-to-T mutation at the 6th position of exon 7 (C to U substitution in RNA) is the major cause of SMN2 exon 7 skipping [77,78] (Fig. 2), regulation of this exon splicing is very complex [82,83]. About forty transacting factors and multiple cis-elements located within exon 7 and the flanking intronic sequences have been implicated in modulation of its splicing [84,85]. Structural studies confirm sequestration of the 5′ss of exon 7 within a terminal stem-loop (TSL2) formed by both exonic and intronic sequences (Fig. 3) [28]. Mutations that disrupt TSL2 promote SMN2 exon 7 inclusion [28]. In vivo selection that tested the position-specific significance of every exonic residue in regulation of exon 7 splicing revealed an A residue at the last exonic position as highly inhibitory [86]. Indeed, an A-to-G substitution at the last position of exon 7 fully restored SMN2 exon 7 inclusion even in the absence of the exonic splicing enhancers [86]. The stimulatory effect of this A-to-G substitution was attributed at least in part to an increase in a number of base pairs formed between U1 snRNA and the 5′ss of exon 7. Consistently, an eU1 with “perfect” complementarity to the 5′ss of exon 7 fully restored SMN2 exon 7 inclusion [28]. This eU1 also obviated the need for the positive cis-elements located within exon 7 [28]. These results underscored poor recruitment of U1 snRNP at the 5′ ss of SMN2 exon 7 as the limiting factor for exon inclusion in mRNA.

Fig. 3.

Diagrammatic representation of SMN intron 7 secondary structure. It is based on experimental structure probing results [28]. Last twenty-two nucleotides of exon 7 are given as well. Exonic sequences are shown in black, intronic, in blue. Negative and neutral numbering of nucleotides starts from the end of exon 7 and the beginning of intron 7, respectively. Regulatory cis-element that affect exon 7 splicing, including ISS-N1 with its hnRNP A1/A2 binding sites, GC-rich sequence and TIA1 binding sites, are highlighted with colors [85]. Structural elements that contribute to exon 7 skipping, including terminal stem loops (TSL) 2 and 3 as well as internal stem formed by long-distance interactions (ISTL) 1, are shown [85]. The authentic and the cryptic (Cr1 and Cr2) 5′ splice sites are indicated by red arrows. Cr1 and Cr2 are described in [36].

3.2. Multiple cis-elements determine the accessibility of the 5′ss of SMN exon 7

The discovery of the intronic splicing silencer N1 (ISS-N1) located immediately downstream of the 5′ss of exon 7 suggested additional constraints in the recruitment of U1 snRNP (Fig. 3) [87]. Supporting this argument, deletion of ISS-N1 or an antisense-oligonucleotide (ASO)-mediated sequestration of ISS-N1 fully restored SMN2 exon 7 inclusion [87]. Deletion of ISS-N1 also obviated the requirement for the positive cis-elements within SMN exon 7. These surprising findings earned ISS-N1 the status of the “master checkpoint” of exon 7 splicing regulation [88]. Interestingly, ISS-N1-targeting ASOs showed better efficacies than several hundred ASOs tested against SMN2 exon 7 and the flanking intronic sequences [89-91]. These observations led to the development of an ASO-based therapy for SMA. The currently approved drug for SMA, Nusinersen (also known as Spinraza™), is an ASO that targets ISS-N1 [92,93]. The proposed mechanisms by which an ISS-N1-targteing ASO restores SMN2 exon 7 inclusion involve displacement of the inhibitory factors interacting with ISS-N1 as well as structural rearrangements that favor recruitment of the U1 snRNP at the 5′ss of exon 7 [90,94]. Inspired by the discovery of ISS-N1, subsequent studies attempted to define the optimum size for an ISS-N1-targeting ASO for maximum stimulation of SMN2 exon 7 inclusion [95-97]. While both longer and shorter ASOs that targeted ISS-N1 and overlapping sequences showed efficacy in splicing correction [96,98], in order to promote exon 7 inclusion, they had to sequester the first position of ISS-N1, which happens to be a C residue at the 10th intronic position (10C) [98]. It was subsequently shown that 10C is involved in the formation of a unique RNA structure, ISTL1 (intronic structure through a long-distance interaction 1), formed by a long-distance interaction (Fig. 3) [98]. Disruption of ISTL1 by an ASO annealing to a deep intronic sequence promoted SMN2 exon 7 inclusion [98]. Of note, a previously reported short ASO that promoted SMN2 exon 7 inclusion is also predicted to disrupt ISTL1 [95]. Similar to the ISS-N1-targeting ASOs [99,100], short and long ASOs that disrupt ISTL1 conferred therapeutic efficacies in mouse models of SMA [101,102]. Analogous to the ISS-N1 targeting ASOs, ISTL1-targeting ASOs are proposed to promote SMN2 exon 7 inclusion via improving the accessibility of the 5′ss of exon 7 for U1 snRNA annealing [94].

3.3. U1 snRNP-dependent exon definition from a distance model

In addition to ASOs, eU1s targeting ISS-N1 as well as sequences located upstream and downstream of this cis-element have been shown to promote SMN2 exon 7 inclusion (Fig. 2) [33,35,36,103]. Recently we identified two novel cryptic 5′ss, Cr1 and Cr2, located 23 and 51 nts downstream of the authentic 5′ss of exon 7, respectively (Fig. 3) [36]. Cr1 partially overlaps with ISS-N1 and can be activated by eU1s when the authentic 5′ss of exon 7 is abrogated or weakened (Figs. 4 and 5) [36]. Of note, usage of Cr1 has been confirmed for a subset of the recently reported SMN circRNAs [104]. In the context of SMN2, eU1 annealing to sequences downstream of Cr1 overwhelmingly activated the authentic 5′ss of exon 7, supporting the role of eU1 in selection of the 5′ss from a distance (Fig. 2) [36]. These results independently validate a previous study in which eU1s annealing to sequences away from the authentic 5′ss of SMN2 exon 7 stimulated usage of this site for exon inclusion [103]. The authors in this study also showed that the eU1 stimulatory effect was independent of the endogenous U1 snRNP [103]. Consistent with the effect of U1 snRNP from a distance, eU1s annealing upstream of Cr1 activated this site when the authentic 5′ss of exon 7 was mutated (Figs. 4 and 5). Also, the effect of eU1s on the activation of Cr1 did not depend on the presence of a GU dinucleotide at the site of eU1 recruitment [36]. These findings are consistent with previous reports for in vitro and naturally occurring systems, which suggest that the base pairing between the U1 snRNA and the 5′ss is not always essential for the 5′ss recognition and splicing [105-115]. It has been previously shown that TIA1 stimulates SMN2 exon 7 inclusion through interaction with a U-rich sequence downstream of ISS-N1 (Fig. 3) [116]. Interestingly, eU1s recruited at this U-rich site as well as at downstream intronic sequences also promoted SMN2 exon 7 inclusion, suggesting that in some contexts, eU1 can exert its impact on splice site selection from a distance of about 100 nts away from the 5′ss (Fig. 2) [36]. The above findings may also suggest that TIA1 affects splice site selection by recruiting U1 snRNP to sites located away from the 5′ss. An eU1 interacting within exon 7 close to the 5′ss also promoted SMN2 exon 7 inclusion [36], suggesting that the exon-interacting stimulatory factors may impact splice site selection by recruiting U1 snRNP to exonic sites.

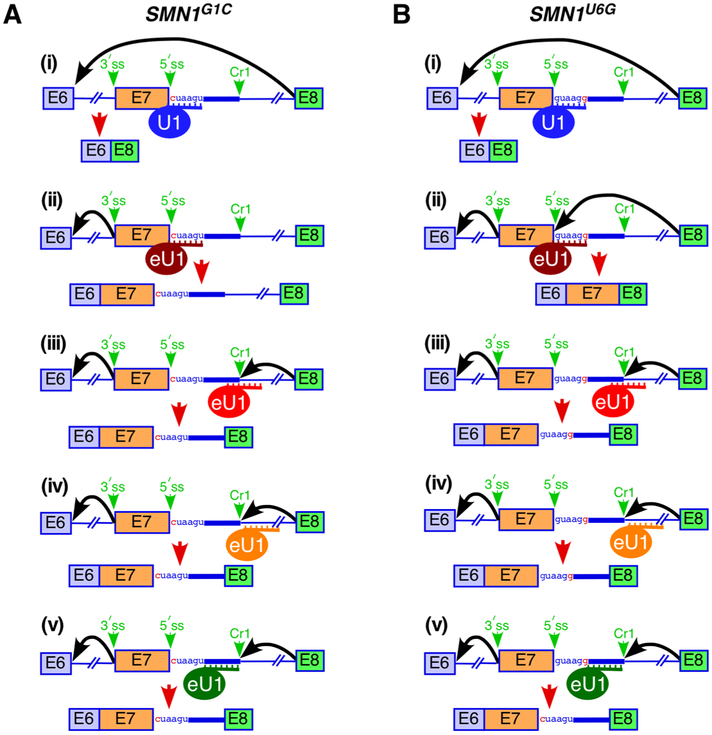

Fig. 4.

Diagrammatic representation of splice site selection from a distance in the context of SMA-associated site-specific mutations within the 5′ss of SMN1 exon 7. Three eU1s indicated in different colors were designed to form maximum possible number of base pairs with their intended targets. Sizes of exons and introns and the relative positioning of the splice sites are not to the scale. Mutated nucleotides are highlighted in red. Abbreviations and markings are the same as in Fig. 2. (A) Effect of eU1s on activation of the 5′ss (authentic or cryptic) from a distance in the context of SMN1 carrying a pathogenic G-to-C mutation at the 1st position of intron 7. (i) Overexpression of wild type U1 snRNA (in blue) is unable to rescue exon 7 inclusion. (ii) eU1 (in brown) annealing to the mutated authentic 5′ss of exon 7 promotes intron 7 retention. (iii) eU1 (in red) annealing to the Cr1 site promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (iv) eU1 (in orange) annealing downstream of Cr1 promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (v) eU1 (in green) annealing upstream of Cr1 promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (B) Effect of eU1s on activation of the 5′ss (authentic or cryptic) from a distance in the context of SMN1 carrying a pathogenic U-to-G mutation at the 6th position of intron 7. (i) Overexpression of wild type U1 snRNA (in blue) is unable to rescue exon 7 inclusion. (ii) eU1 (in brown) designed to anneal to the wild type authentic 5′ss of exon 7 promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of the mutated 5′ss. (iii) eU1 (in red) annealing to the Cr1 site promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (iv) eU1 (in orange) annealing downstream of Cr1 promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (v) eU1 (in green) anneals upstream of Cr1 and promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. Models are based on the results reported in [36].

Fig. 5.

Diagrammatic representation of splice site selection from a distance in the context of SMA-associated deletion mutations at the 5′ and 3′ss of SMN1 exon 7. Three eU1s indicated in different colors were designed to form maximum possible number of base pairs with their intended targets. Sizes of exons and introns and the relative positioning of the splice sites are not to the scale. Abbreviations and markings are the same as in Fig. 2. (A) Effect of eU1s on activation of the cryptic 5′ss (Cr1) from a distance in SMN1 carrying a pathogenic deletion at the 5′ss of exon 7. The 4-nt deletion is indicated by red dashes. (i) Overexpression of wild type U1 snRNA (in blue) is unable to rescue exon 7 inclusion. (ii) eU1 (in light blue) annealing to the mutated authentic 5′ss of exon 7 promotes intron 7 retention. (iii) eU1 (in red) annealing to the Cr1 site promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (iv) eU1 (in orange) annealing downstream of Cr1 promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (B) Effect of eU1s on activation of the 5′ss from a distance in the context of SMN1 carrying a pathogenic deletion at the 3′ss of exon 7. Δ refers to a 7-nt deletion within the polypyrimidine tract of the 3′ss of exon 7. (i) Overexpression of wild type U1 snRNA (in blue) is unable to rescue exon 7 inclusion. (ii) eU1 (in brown) annealing to the authentic 5′ss of exon 7 promotes its inclusion through activation of this site. (iii) eU1 (in red) annealing to the Cr1 site promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of Cr1. (iv) eU1 (in orange) annealing downstream of Cr1 promotes exon 7 inclusion through activation of the authentic 5′ss. Models are based on the results reported in [36].

The effect of U1 snRNP from a distance depends on several factors, including strength of both the 5′ and 3′ss as well as presence of the putative cryptic 5′ss. In case of a lethal G-to-C mutation at the first position (G1C) of intron 7 of SMN1, an eU1 targeting ISS-N1 or nearby sequences activated Cr1 (Fig. 4) [36]. Similar results were obtained in the context of a U-to-G mutation at the sixth position (U6G) of intron 7 of SMN1 (Fig. 4). In addition to Cr1 activation, most eU1s also caused intron 7 retention in SMN1 carrying G1C or U6G mutation within intron 7 (36). These results supported the ability of U1 snRNP to define the 3′ss of an exon in the instance when the 5′ss of the exon is mutated. When the 3′ss of SMN1 exon 7 was weakened by a 7-nt deletion within the polypyrimidine tract, eU1s targeting ISS-N1 or downstream sequences promoted exon 7 inclusion through usage of the authentic 5′ss of exon 7 (Fig. 5). These results confirm the effect of eU1 in splice site selection from a distance in the context of a weak 3′ss. Importantly, based on foot-printing experiments, U1 snRNP is estimated to occupy at least 26 nts, including 20 nts upstream and 6 nts downstream of the 5′ss on a pre-mRNA [117]. Authentic 5′ss of exon 7 and Cr1 are separated from each other by 23 nucleotides. Hence, it is highly unlikely that U1 snRNP and eU1 are simultaneously recruited at the authentic 5′ss and Cr1, respectively.

Usage of the authentic 5′ss upon eU1 recruitment at Cr1 does not fall within the traditional “exon definition model” in which recruitment of U1 snRNP at the authentic 5′ss defines the upstream 3′ss through cross-exon communication [118]. Considering retention of intron 7 was frequently observed in the presence of eU1s targeting different sites within intron 7, the results also fall outside the purview of “intron definition model” in which recruitment of U1 and U2 snRNPs at the beginning and the end of an intron, respectively, defines this intron [118]. Hence, an alternative “exon definition from a distance” model in which recruitment of U1 snRNP away from an exon/intron junction appears to be in play for defining the boundary of an exon.

3.4. Mechanism of U1 snRNP-dependent exon definition from a distance

The role of U1 snRNP in pre-mRNA splicing is limited to the formation of the early spliceosomal E complex at the beginning of the step-wise assembly of the spliceosome on a pre-mRNA [65]. U1 snRNP remains the component of the pre-spliceosomal complex A and complex pre-B. During subsequent spliceosome maturation when extensive conformational and compositional remodeling takes place, U1 is displaced and the spliceosome catalytically activated [65]. It has been suggested that the 5′ and 3′ss are brought in close proximity early in spliceosome assembly and that interactions between U1 and U2 snRNPs form one of the molecular links that pairs the two splice sites (50,119-121). Recently, it has been shown that U1/U2 interaction is facilitated by the SF3A1 protein, a component of the U2 snRNP, that binds to the stem-loop 4 (SL4) of U1 snRNA [50]. Interestingly, mutations in SL4 of an eU1 (SM25) that targets sequences downstream of the ISS-N1, inactivated eU1s [103], suggesting the important role of SF3A1 in conferring U1 snRNP function from a distance. Depletion of U1-70K protein that interacts with SL1 also adversely affected activity of eU1s [103]. This is likely due to the role U1-70K plays in making the 5′-end of U1 snRNA available for interactions with a target site. It is also possible that U1-70K provides stability to U1 snRNP. At the same time, depletion of U1A or U1C proteins did not affect the activities of eU1s [103], suggesting that these proteins are dispensable for providing stability to U1 snRNP or making the 5′-end of U1 snRNA accessible. Overall, findings support that a partially assembled U1 snRNP with preserved capability to interact with U2 snRNP via SF3A1 is necessary for U1 snRNP-associated definition of exonic boundaries from a distance. It should be noted that using a different technical approach, single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET), it was shown that, at least in yeast, the 5′ ss and the branch point are brought into close proximity much later: they are kept physically separate until the spliceosome is activated for catalysis (122). Furthermore, the recent cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the entire human pre-B complex indicated that, at this stage of the spliceosome assembly, U1 and U2 snRNPs do not interact with each other and are separated by a gap of 60 to 100 Å (123). At the same time, another study supported U1 snRNP placement in the vicinity of SF3A1 in the human pre-B complex (124). This difference in results could be explained by several possibilities, including lesser ability of some techniques to accurately capture the highly dynamic U1 and U2 interactions. It should also be noted that the interrogated spliceosomal complexes used for the cryo-EM were assemble on a pre-mRNA containing only two exons separated by a rather short intron (123). Future studies employing diverse pre-mRNAs will provide additional insights into our understanding of U1-U2 interactions.

4. Conclusions

U1 snRNP is the universally expressed RNP complex in eukaryotes and is considered essential for the removal of introns from pre-mRNAs. The core structure of U1 snRNP, including the “accessible” 5′-end of U1 snRNA, is evolutionary conserved from yeast to humans. As per prevailing understanding, base pairing between the 5′-end of U1 snRNA and the 5′ss of an exon defines an exon-intron boundary. However, exceptions to this general rule exist as U1 snRNP also defines the 5′ss used for cleavage by interacting with sequences away from the 5′ss. In this case, the recruitment site of U1 snRNP does not even have to be a 5′ss-sequence-like, including the presence of a GU dinucleotide. Further, it is also possible that the presence of multiple U1 snRNA genes in humans serve specialized purpose of splice site selection from a distance. Findings employing eU1s support that a partially assembled U1 snRNP containing U1-70K and SF3A1 protein binding sites is sufficient to define the exonic boundaries from a distance. Also, accessibility of the 3′ss for interaction with U2 snRNP appears to be necessary for the stimulatory effect elicited by eU1s annealing upstream or downstream of 5′ splice sites. In agreement with this argument, recruitment of U1 snRNP to an exonic site located close to the 3′ss has been shown to suppress exon definition [125]. Consistently, removal of intron 6 of SMN was strongly stimulated by eU1s targeting downstream intron 7 sequences, resulting in the accumulation of the intron 7-retained transcripts [36]. Furthermore, a recent report suggests that a strong 3′ss serves as the driver of the recursive splicing used for removal of large introns [126]. In the recursive splicing, the removal of the upstream intronic portion precedes the removal of the downstream intronic portion. Future studies will determine if the eU1-dependent exon definition from a distance is particularly useful for promoting recursive splicing. It will be also interesting to see if the role of U1 snRNP in exon definition from a distance overlaps with that of the non-splicing-associated functions of U1 snRNP, including transcription, telescripting and the 3′-end processing. Future studies aimed at deciphering the mechanisms of the U1 snRNP-induced exon definition from a distance will refine our understanding of alternative splicing and open up novel targets for the eU1-based therapies for a growing number of genetic disorders caused by aberrant splicing. Several small compounds that modulate SMN2 exon 7 splicing have been recently proposed to work through enhanced recruitment of U1 snRNP at the authentic 5′ss of exon 7 [127-129]. Based on these developments, it is tempting to speculate that small molecules may also hold enormous therapeutic potential for context-specific splicing modulation through recruitment of the endogenous U1 snRNP to sites other than the authentic 5′ss.

Highlights:

Engineered U1 snRNP dictates 5′ splice site (5′ss) selection from a distance

Effect of U1 snRNP from distance does not require 5′ss-like sequence

U1 snRNP recruitment upstream or downstream of the authentic 5′ss can activate this 5′ss

Engineered U1 snRNP-induced 5′ss selection from a distance has broad therapeutic implications

Acknowlegements

Authors acknowledge Dr. Joonbae Seo for the critical reading of the manuscript and for valuable suggestions. Authors have attempted to include most contributions on U1 snRNP-dependent splice site selection and have provided references to review articles on specific topics. Authors acknowledge and regret for not being able to include several related references due to the lack of space.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS055925 and R21 NS101312).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures and competing interests: ISS-N1 target (US patent # 7,838,657) mentioned in this review was discovered in the Singh lab at UMASS Medical School (Worcester, MA, USA). Inventors, including RNS, NNS and UMASS Medical School, are currently benefiting from licensing of ISS-N1 target (US patent # 7,838,657) to IONIS Pharmaceuticals/Biogen, which is marketing SpinrazaTM (Nusinersen), the FDA-approved drug, based on ISS-N1 target.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Sharp PA, Split genes and RNA splicing, Cell 77 (1994) 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ebbesen KK, Kjems J, Hansen TB, Circular RNAs: Identification, biogenesis and function, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1859 (2016) 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wilusz JE, A 360° view of circular RNAs: From biogenesis to functions, Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 9 (2018), e1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yang L, Splicing noncoding RNAs from the inside out, Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 6 (2015), 651–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kelemen O, Convertini P, Zhang Z, Wen Y, Szhen M, Falaleeva M, Stamm S, Function of alternative splicing, Gene 514 (2013), 1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barrie ES, Smith RM, Sanford JC, Sadee W, mRNA transcript diversity creates new opportunities for pharmacological intervention. Mol Pharmacol. 81 (2012) 620–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Baralle M, Baralle FE, The splicing code, Biosystems. 164 (2018) 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Novikova O, Belfort M, Mobile Group II Introns as Ancestral Eukaryotic Elements, Trends Genet. 33 (2017) 773–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Singh RN, Saldanha RJ, D'Souza LM, Lambowitz AM. Binding of a group II intron-encoded reverse transcriptase/maturase to its high affinity intron RNA binding site involves sequence-specific recognition and autoregulates translation. J Mol Biol. 318 (2002) 287–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Papasaikas P, Valcárcel J, The Spliceosome: The Ultimate RNA Chaperone and Sculptor, Trends Biochem. Sci 41 (2016) 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shi Y, The Spliceosome: A Protein-Directed Metalloribozyme, J Mol Biol. 429 (2017), 2640–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen W, Moore MJ, Spliceosomes, Curr. Biol 25 (2015) R181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Baserga SJ, Steitz JA, The diverse world of small ribonucleoproteins In: The RNA world, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, (1993) 359–381. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wassarman KM, Steitz JA, Association with terminal exons in pre-mRNAs: a new role for the U1 snRNP? Genes Dev. 7 (1993) 647–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ashe MP, Pearson LH, Proudfoot NJ, The HIV-1 5' LTR poly(A) site is inactivated by U1 snRNP interaction with the downstream major splice donor site, EMBO J. 16 (1997) 5752–5763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vagner S, Rüegsegger U, Gunderson SI, Keller W, Mattaj IW, Position-dependent inhibition of the cleavage step of pre-mRNA 3'-end processing by U1 snRNP, RNA 6 (2000) 178–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kaida D, Berg MG, Younis I, Kasim M, Singh LN, Wan L, Dreyfuss G, U1 snRNP protects pre-mRNAs from premature cleavage and polyadenylation, Nature 468 (2010) 664–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Almada AE, Wu X, Kriz AJ, Burge CB, Sharp PA, Promoter directionality is controlled by U1 snRNP and polyadenylation signals, Nature 499 (2013) 360–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chiu AC, Suzuki HI, Wu X, Mahat DB, Kriz AJ, Sharp PA, Transcriptional Pause Sites Delineate Stable Nucleosome-Associated Premature Polyadenylation Suppressed by U1 snRNP, Mol. Cell 69 (2018) 648–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Raj B, Blencowe BJ. Alternative splicing in the mammalian nervous system: recent insights into mechanisms and functional roles. Neuron. 2015; 87:14–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Erkelenz S, Mueller WF, Evans MS, Busch A, Schöneweis K, Hertel KJ, Schaal H, Position-dependent splicing activation and repression by SR and hnRNP proteins rely on common mechanisms, RNA 19 (2013) 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fu XD, Ares M Jr., Context-dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA-binding proteins, Nat. Rev. Genet 15 (2014) 689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wong MS, Kinney JB, Krainer AR, Quantitative Activity Profile and Context Dependence of All Human 5' Splice Sites, Mol. Cell 71 (2018) 1012–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Martinez-Contreras R, Fisette JF, Nasim FU, Madden R, Cordeau M, Chabot B, Intronic binding sites for hnRNP A/B and hnRNP F/H proteins stimulate pre-mRNA splicing, PLoS Biol. 4 (2006) e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ule J, Stefani G, Mele A, Ruggiu M, Wang X, Taneri B, Gaasterland T, Blencowe BJ, Darnell RB, An RNA map predicting Nova-dependent splicing regulation, Nature 444 (2006) 580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang Z, Kayikci M, Briese M, Zarnack K, Luscombe NM, Rot G, Zupan B, Curk T, Ule J, iCLIP predicts the dual splicing effects of TIA-RNA interactions. PLoS Biol. 8(2010)e1000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hiller M, Zhang Z, Backofen R, Stamm S, Pre-mRNA secondary structures influence exon recognition, PLoS Genet. 3 (2007) e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Singh NN, Singh RN, Androphy EJ, Modulating role of a RNA structure in skipping of a critical exon in the spinal muscular atrophy genes, Nucleic Acids Res. 35 (2007) 371–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Buratti E, Dhir A, Lewandowska MA, Baralle FE, RNA structure is a key regulatory element in pathological ATM and CFTR pseudoexon inclusion events, Nucleic Acids Res. 35 (2007) 4369–4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Warf MB, Berglund JA, Role of RNA structure in regulating pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 35 (2010) 169–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pervouchine DD, Khrameeva EE, Pichugina MY, Nikolaienko OV, Gelfand MS, Rubtsov PM, Mironov AA, Evidence for widespread association of mammalian splicing and conserved long-range RNA structures, RNA 18 (2012) 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Singh NN, Lee BM, Singh RN, Splicing regulation in spinal muscular atrophy by a RNA structure formed by long distance interactions, Annals of NY Academy of Sciences 1341 (2015) 176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fernandez Alanis E, Pinotti M, Dal Mas A, Balestra D, Cavallari N, Rogalska ME, Bernardi F, Pagani F, An exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) strategy to correct splicing defects, Hum Mol Genet. 21 (2012) 2389–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dal Mas A, Fortugno P, Donadon I, Levati L, Castiglia D, Pagani F, Exon-Specific U1s Correct SPINK5 Exon 11 Skipping Caused by a Synonymous Substitution that Affects a Bifunctional Splicing Regulatory Element, Hum Mutat. 36 (2015) 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dal Mas A, Rogalska ME, Bussani E, Pagani F, Improvement of SMN2 pre-mRNA processing mediated by exon-specific-U1-small nuclear RNA, Am J Hum Genet. 96 (2015)93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Singh NN, Del Rio-Malewski JB, Luo D, Ottesen EW, Howell MD, Singh RN, Activation of a cryptic 5' splice site reverses the impact of pathogenic splice site mutations in the spinal muscular atrophy gene, Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (2017) 12214–12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Balestra D, Scalet D, Pagani F, Rogalska ME, Mari R R, Bernardi F, Pinotti M, An Exon-Specific U1snRNA Induces a Robust Factor IX Activity in Mice Expressing Multiple Human FIX Splicing Mutants. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 5 (2016) e370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Donadon I, Pinotti M, Rajkowska K, Pianigiani G, Barbon E, Morini E, Motaln H, Rogelj B, Mingozzi F, Slaugenhaupt SA, Pagani F, Exon-specific U1 snRNAs improve ELP1 exon 20 definition and rescue ELP1 protein expression in a familial dysautonomia mouse model, Hum Mol Genet. 27 (2018) 2466–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Martínez-Pizarro A, Dembic M, Pérez B, Andresen BS, Desviat LR, Intronic PAH gene mutations cause a splicing defect by a novel mechanism involving U1snRNP binding downstream of the 5' splice site, PLoS Genet. 14 (2018) e1007360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Guiro J, O'Reilly D, Insights into the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex superfamily, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 6 (2015) 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Weber G, Trowitzsch S, Kastner B, Lührmann R, Wahl MC, Functional organization of the Sm core in the crystal structure of human U1 snRNP, EMBO J. 29 (2010) 4172–4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kondo Y, Oubridge C, van Roon AM, Nagai K, Crystal structure of human U1 snRNP, a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle, reveals the mechanism of 5' splice site recognition, Elife 4 (2015) doi: 10.7554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Nelissen RL, Will CL, van Venrooij WJ, Lührmann R, The association of the U1-specific 70K and C proteins with U1 snRNPs is mediated in part by common U snRNP proteins, EMBO J. 13 (1994) 4113–4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Reddy R, Henning D, Busch H, Pseudouridine residues in the 5'-terminus of uridine-rich nuclear RNA I (U1 RNA), Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 98 (1981) 1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Query CC, Bentley RC, Keene JD, A specific 31-nucleotide domain of U1 RNA directly interacts with the 70K small nuclear ribonucleoprotein component, Mol Cell Biol. 9 (1989) 4872–4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Scherly D, Boelens W, van Venrooij WJ, Dathan NA, Hamm J, Mattaj IW, Identification of the RNA binding segment of human U1 A protein and definition of its binding site on U1 snRNA, EMBO J. 8 (1989) 4163–4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hamm J, Dathan NA, Scherly D, Mattaj IW, Multiple domains of U1 snRNA, including U1 specific protein binding sites, are required for splicing, EMBO J. 9 (1990) 1237–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nilsen TW, An intimate view of a spliceosome component, Elife 4 (2015) e06200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].van der Feltz C, Anthony K, Brilot A, Pomeranz Krummel DA, Architecture of the spliceosome, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 3321–3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sharma S, Wongpalee SP, Vashisht A, Wohlschlegel JA, Black DL, Stem-loop 4 of U1 snRNA is essential for splicing and interacts with the U2 snRNP-specific SF3A1 protein during spliceosome assembly, Genes Dev. 28 (2014) 2518–2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Dahlberg JE, Lund E, Structure and function of major and minor small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (ed. Birnstiel ML), Springer, Berlin: (1988) 38–70. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pomeranz Krummel DA, Oubridge C, Leung AK, Li J, Nagai K, Crystal structure of human spliceosomal U1 snRNP at 5.5 A resolution, Nature 458 (2009) 475–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Du H, Rosbash M, The U1 snRNP protein U1C recognizes the 5' splice site in the absence of base pairing, Nature 419 (2002) 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Roca X, Akerman M, Gaus H, Berdeja A, Bennett CF, Krainer AR, Widespread recognition of 5′ splice sites by noncanonical base-pairing to U1 snRNA involving bulged nucleotides, Genes Dev. 26 (2012) 1098–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Tan J, Ho JX, Zhong Z, Luo S, Chen G, Roca X, Noncanonical registers and base pairs in human 5' splice-site selection, Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (2016) 3908–3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sperling R, Spann P, Offen D, Sperling J, U1, U2, and U6 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) are associated with large nuclear RNP particles containing transcripts of an amplified gene in vivo, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 83 (1986) 6721–6725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kotzer-Nevo H, de Lima Alves F, Rappsilber J, Sperling J, Sperling R, Supraspliceosomes at defined functional states portray the pre-assembled nature of the pre-mRNA processing machine in the cell nucleus, Int. J. Mol. Sci 15 (2014) 11637–11664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Leichter M, Marko M, Ganou V, Patrinou-Georgoula M, Tora L, Guialis A, A fraction of the transcription factor TAF15 participates in interactions with a subset of the spliceosomal U1 snRNP complex, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814 (2011) 1812–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pabis M, Neufeld N, Steiner MC, Bojic T, Shav-Tal Y, Neugebauer KM KM, The nuclear cap-binding complex interacts with the U4/U6·U5 tri-snRNP and promotes spliceosome assembly in mammalian cells, RNA 19 (2013) 1054–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Chi B, O'Connell JD, Yamazaki T, Gangopadhyay J, Gygi SP, Reed R, Interactome analyses revealed that the U1 snRNP machinery overlaps extensively with the RNAP II machinery and contains multiple ALS/SMA-causative proteins, Sci Rep. 8 (2018) 8755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Chi B, O'Connell JD, Iocolano AD, Coady JA, Yu Y, Gangopadhyay J, Gygi SP, Reed R, The neurodegenerative diseases ALS and SMA are linked at the molecular level via the ASC-1 complex, Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (2018) 11939–11951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lerner MR, Boyle JA, Mount SM, Wolin SL, Steitz JA, Are snRNPs involved in splicing? Nature 283 (1980) 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rogers J, Wall R, A mechanism for RNA splicing, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 77 (1980) 1877–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zhuang Y, Weiner AM, A compensatory base change in U1 snRNA suppresses a 5' splice site mutation, Cell 46 (1986) 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Will CL, Lührmann R, Spliceosome structure and function, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Förch P, Puig O, Martínez C, Séraphin B, Valcárcel J, The splicing regulator TIA-1 interacts with U1-C to promote U1 snRNP recruitment to 5' splice sites, EMBO J. 21 (2002) 6882–6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Aznarez I, Barash Y, Shai O, He D, Zielenski J, Tsui LC, Parkinson J, Frey BJ, Rommens JM, Blencowe BJ, A systematic analysis of intronic sequences downstream of 5' splice sites reveals a widespread role for U-rich motifs and TIA1/TIAL1 proteins in alternative splicing regulation, Genome Res. 18 (2008) 1247–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Gal-Mark N, Schwartz S, Ram O, Eyras E, Ast G, The pivotal roles of TIA proteins in 5' splice-site selection of alu exons and across evolution, PLoS Genet. 5 (2009) e1000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kameoka S, Duque P, Konarska MM, p54(nrb) associates with the 5' splice site within large transcription/splicing complexes. EMBO J. 23 (2004) 1782–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Séraphin B, Kretzner L, Rosbash M, A U1 snRNA:pre-mRNA base pairing interaction is required early in yeast spliceosome assembly but does not uniquely define the 5' cleavage site, EMBO J. 7 (1988) 2533–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Siliciano PG, Guthrie C, 5' splice site selection in yeast: genetic alterations in base-pairing with U1 reveal additional requirements, Genes Dev. 2 (1988) 1258–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Séraphin B, Rosbash M, Exon mutations uncouple 5' splice site selection from U1 snRNA pairing, Cell 63 (1990) 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Romfo CM, Alvarez CJ, van Heeckeren WJ, Webb CJ, Wise JA, Evidence for splice site pairing via intron definition in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Mol Cell Biol. 20 (2000)7955–7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Cohen JB, Snow JE, Spencer SD, Levinson AD, Suppression of mammalian 5' splice-site defects by U1 small nuclear RNAs from a distance, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 91 (1994) 10470–10474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lefebvre S, Bürglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Benichou B, Cruaud C, Millasseau P, Zeviani M, Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene, Cell 80 (1995) 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Singh RN, Howell MD, Ottesen EW, Singh NN, Diverse role of survival motor neuron protein, Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 1860 (2017) 299–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Lorson CL, Hahnen E, Androphy EJ, Wirth B, A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 11 (1999) 6307–6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Monani UR, Lorson CL, Parsons DW, Prior TW, Androphy EJ, Burghes AH, McPherson JD, A single nucleotide difference that alters splicing patterns distinguishes the SMA gene SMN1 from the copy gene SMN2, Hum Mol Genet. 8 (1999) 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Seo J, Howell MD, Singh NN, Singh RN, Spinal muscular atrophy: An update on therapeutic progress, Biochim Biophys Acta 1832 (2013) 2180–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Howell MD, Singh NN, Singh RN, Advances in therapeutic development for spinal muscular atrophy, Future Med Chem. 6 (2014) 1081–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Parente V, Corti S S, Advances in spinal muscular atrophy therapeutics. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 11 (2018) 1756285618754501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Singh RN, Evolving concepts on human SMN pre-mRNA splicing, RNA Biol. 4 (2007) 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Singh NN, Singh RN, Alternative splicing in spinal muscular atrophy underscores the role of an intron definition model, RNA Biol. 8 (2011) 600–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Singh NN, Howell MD, Singh RN, Transcription and splicing regulation of spinal muscular atrophy genes, in: Sumner CJ, Paushkin S, Ko C-P (Eds.), Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Disease Mechanisms and Therapy, Academic Press, London, (2017) 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- [85].Singh RN, Singh NN, Mechanism of Splicing Regulation of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Genes, Adv Neurobiol. 20 (2018) 31–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Singh NN, Androphy EJ, Singh RN, In vivo selection reveals features of combinatorial control that defines a critical exon in the spinal muscular atrophy genes, RNA 10 (2004) 1291–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Singh NK, Singh NN, Androphy EJ, Singh RN, Splicing of a critical exon of human Survival Motor Neuron is regulated by a unique silencer element located in the last intron, Mol Cell Biol. 26 (2006) 1333–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Buratti E, Baralle M, Baralle FE, Defective splicing, disease and therapy: searching for master checkpoints in exon definition, Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (2006) 3494–3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Hua Y, Vickers TA, Baker BF, Bennett CF, Krainer AR, Enhancement of SMN2 exon 7 inclusion by antisense oligonucleotides targeting the exon, PLoS Biol. 5 (2007) e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hua Y, Vickers TA, Okunola HL, Bennett CF, Krainer AR, Antisense masking of an hnRNP A1/A2 intronic splicing silencer corrects SMN2 splicing in transgenic mice, Am. J. Hum. Genet 82 (2008) 834–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Sivanesan S, Howell MD, DiDonato CJ, Singh RN, Antisense oligonucleotide mediated therapy of spinal muscular atrophy, Transl Neurosci. 4 (2013) 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ottesen EW, ISS-N1 makes the First FDA-approved Drug for Spinal Muscular Atrophy, Transl Neurosci. 8 (2017) 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Singh NN, Howell MD, Androphy EJ, Singh RN, How the discovery of ISS-N1 led to the first medical therapy for spinal muscular atrophy, Gene Ther. 24 (2017) 520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Singh NN, Lee BM, DiDonato CJ, Singh RN, Mechanistic principles of antisense targets for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy, Future Med. Chem 7 (2015) 1793–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Singh NN, Shishimorova M, Cao LC, Gangwani L, Singh RN, A short antisense oligonucleotide masking a unique intronic motif prevents skipping of a critical exon in spinal muscular atrophy, RNA Biol. 6 (2009) 341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Singh NN, Hollinger K, Bhattacharya D, Singh RN, An antisense microwalk reveals critical role of an intronic position linked to a unique long-distance interaction in pre mRNA splicing, RNA 16 (2010) 1167–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Zhou H, Janghra N, Mitrpant C, Dickinson RL, Anthony K, Price L, Eperon IC, Wilton SD, Morgan J, Muntoni F, A novel morpholino oligomer targeting ISS-N1 improves rescue of severe spinal muscular atrophy transgenic mice, Hum. Gene. Ther 24 (2013) 331–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Singh NN, Lawler MN, Ottesen EW, Upreti D, Kaczynski JR, Singh RN, An intronic structure enabled by a long-distance interaction serves as a novel target for splicing correction in spinal muscular atrophy, Nucleic Acids Res. 41 (2013) 8144–8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Hua Y, Sahashi K, Rigo F, Hung G, Horev G, Bennett CF, Krainer AR, Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model, Nature 478 (2011) 123–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Porensky PN, Mitrpant C, McGovern VL, Bevan AK, Foust KD, Kaspar BK, Wilton SD, Burghes AH, A single administration of morpholino antisense oligomer rescues spinal muscular atrophy in mouse, Hum Mol Genet. 21 (2012) 1625–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Keil JM, Seo J, Howell MD, Hsu WH, Singh RN, DiDonato CJ, A short antisense oligonucleotide ameliorates symptoms of severe mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy, Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 3 (2014) e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Howell MD, Ottesen EW, Singh NN, Anderson RL, Singh RN, Gender-Specific Amelioration of SMA Phenotype upon Disruption of a Deep Intronic Structure by an Oligonucleotide, Mol Ther. 25 (2017) 1328–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Rogalska ME, Tajnik M, Licastro D, Bussani E, Camparini L, Mattioli C, Pagani F, Therapeutic activity of modified U1 core spliceosomal particles, Nat. Commun 7 (2016) 11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Ottesen EW, Luo D, Seo J, Singh NN, Singh RN, Human Survival Motor Neuron genes generate a vast repertoire of circular RNAs, Nucleic Acids Res. 2019. January 30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Du H, Rosbash M, Yeast U1 snRNP-pre-mRNA complex formation without U1 snRNA-pre-mRNAbase pairing, RNA 7 (2001) 133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Crispino JD, Blencowe BJ, Sharp PA PA, Complementation by SR proteins of pre-mRNA splicing reactions depleted of U1 snRNP, Science 265 (1994) 1866–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Tarn WY, Steitz JA, SR proteins can compensate for the loss of U1 snRNP functions in vitro, Genes Dev. 8 (1994) 2704–2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Raponi M, Buratti E, Dassie E, Upadhyaya M, Baralle D, Low U1 snRNP dependence at the NF1 exon 29 donor splice site, FEBS J. 276 (2009) 2060–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Fukumura K, Taniguchi I, Sakamoto H, Ohno M, Inoue K, U1-independent pre-mRNA splicing contributes to the regulation of alternative splicing, Nucleic Acids Res. 37 (2009) 1907–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Lund M, Kjems J, Defining a 5′ splice site by functional selection in the presence and absence of U1 snRNA 5′ end, RNA 8 (2002) 166–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Crispino JD, Sharp PA, A U6 snRNA:pre-mRNA interaction can be rate-limiting for U1- independent splicing, Genes Dev. 9 (1995) 2314–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Crispino JD, Mermoud JE, Lamond AI, Sharp PA, Cis- acting elements distinct from the 5′ splice site promote U1- independent pre- mRNA splicing, RNA 2 (1996) 664–673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Roca X, Krainer AR, Eperon IC, Pick one, but be quick: 5′ splice sites and the problems of too many choices, Genes Dev. 27 (2013) 129–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Lund M, Kjems J, Defining a 5′ splice site by functional selection in the presence and absence of U1 snRNA 5′ end, RNA 8 (2002) 166–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Fukumura K, Inoue K, Role and mechanism of U1-independent pre-mRNA splicing in the regulation of alternative splicing, RNA Biol. 6 (2009) 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Singh NN, Seo J, Ottesen EW, Shishimorova M, Bhattacharya D, Singh RN, TIA1 prevents skipping of a critical exon associated with spinal muscular atrophy, Mol. Cell. Biol 1 (2011)935–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Nilsen TW, RNase footprinting to map sites of RNA-protein interactions, Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 6, (2014):677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].De Conti L, Baralle M, Buratti E, Exon and intron definition in pre-mRNA splicing, Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 4 (2013) 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Dönmez G, Hartmuth K, Kastner B, Will CL, Lührmann R, The 5' end of U2 snRNA is in close proximity to U1 and functional sites of the pre-mRNA in early spliceosomal complexes, Mol Cell. 25 (2007) 399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Kent OA, MacMillan AM, Early organization of pre-mRNA during spliceosome assembly, Nat Struct Biol. 9 (2002) 576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Shao W, Kim HS, Cao Y, Xu YZ, Query CC, A U1-U2 snRNP interaction network during intron definition, Mol Cell Biol. 32 (2012) 470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Crawford DJ, Hoskins AA, Friedman LJ, Gelles J, Moore MJ, Single-molecule colocalization FRET evidence that spliceosome activation precedes stable approach of 5' splice site and branch site, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110 (2013) 6783–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Zhan X, Yan C, Zhang X, Lei J, Shi Y, Structures of the human pre-catalytic spliceosome and its precursor spliceosome, Cell Res. 28 (2018) 1129–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Plaschka C, Lin PC, Nagai K, Structure of a pre-catalytic spliceosome, Nature 546 (2017) 617–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Pagani F, Buratti E, Stuani C, Bendix R, Dörk T, Baralle FE, A new type of mutation causes a splicing defect in ATM, Nat Genet 30 (2002), 426–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Pai AA, Paggi JM, Yan P, Adelman K, Burge CB, Numerous recursive sites contribute to accuracy of splicing in long introns in flies, PLoS Genet, 14 (2018), e1007588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Palacino J, Swalley SE, Song C, Cheung AK, Shu L, Zhang X, Van Hoosear M, Shin Y, Chin DN, Keller CG, Beibel M, Renaud NA, Smith TM, Salcius M, Shi X, Hild M, Servais R, Jain M, Deng L, Bullock C, McLellan M, Schuierer S, Murphy L, Blommers MJ, Blaustein C, Berenshteyn F, Lacoste A, Thomas JR, Roma G, Michaud GA, Tseng BS, Porter JA, Myer VE, Tallarico JA, Hamann LG, Curtis D, Fishman MC, Dietrich WF, Dales NA, Sivasankaran R, SMN2 splice modulators enhance U1-pre-mRNA association and rescue SMA mice, Nat Chem Biol. 11 (2015) 511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Sivaramakrishnan M, McCarthy KD, Campagne S, Huber S, Meier S, Augustin A, Heckel T, Meistermann H, Hug MN, Birrer P, Moursy A, Khawaja S, Schmucki R, Berntenis N, Giroud N, Golling S, Tzouros M, Banfai B, Duran-Pacheco G, Lamerz J, Hsiu Liu Y, Luebbers T, Ratni H, Ebeling M, Cléry A, Paushkin S, Krainer AR, Allain FH, Metzger F, Binding to SMN2 pre-mRNA-protein complex elicits specificity for small molecule splicing modifiers, Nat Commun. 8 (2017) 1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Garcia-Lopez A, Tessaro F, Jonker HRA, Wacker A, Richter C, Comte A, Berntenis N, Schmucki R, Hatje K, Petermann O, Chiriano G, Perozzo R, Sciarra D, Konieczny P, Faustino I, Fournet G, Orozco M, Artero R, Metzger F, Ebeling M, Goekjian P, Joseph B, Schwalbe H, Scapozza L, Targeting RNA structure in SMN2 reverses spinal muscular atrophy molecular phenotypes, Nat Commun. 9 (2018), 2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]