Abstract

Optically-controlled non-genetic neuromodulation represents a promising approach for the fundamental study of neural circuits and the clinical treatment of neurological disorders. Among existing material candidates that can transduce light energy into biologically-relevant cues, silicon (Si) is particularly advantageous due to its highly tunable electrical and optical properties, ease of fabrication into multiple forms, ability to absorb a broad range of light spectrum, and biocompatibility. This protocol describes a rational design principle for Si-based structures, general procedures for material synthesis and device fabrication, a universal method to evaluate material photo-responses, detailed illustrations of all instrumentation used, and demonstrations of optically-controlled non-genetic modulation of cellular calcium dynamics, neuronal excitability, neurotransmitter release from mouse brain slices, and brain activity in the mouse brain in vivo using the aforementioned Si materials. The entire procedure takes ~ 4–8 days in the hands of an experienced graduate student, depending on the specific biological targets. We anticipate that our approach can be adapted in the future to study other systems such as cardiovascular tissues and microbial communities.

Keywords: Bioelectronic interfaces, Neuromodulation, Photostimulation, Silicon, Bioelectronics, Biointerfaces, Neuroengineering

EDITORIAL SUMMARY

This Protocol describes how to fabricate and apply silicon-based structures for optically controlled neuromodulation. The structures can be used for non-genetic neuronal excitation in cultured neurons, brain slices and in vivo applications.

New Protocol for fabricating and applications of silicon-based structures for optically controlled neuromodulation.

Introduction

Electrical neuromodulation constitutes the basis of many implantable medical devices that are valuable in treating debilitating medical conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, clinical depression, and epilepsy1–8. While traditional stimulation electrodes have significantly improved patients’ quality of life, they are often limited by their need to be tethered to electrical wiring and their inability to target single cells. Moreover, the bulky and rigid nature of these electrodes can induce severe inflammation in target tissue9–13. Alternative neuromodulation methods using optical stimuli can significantly alleviate tissue inflammatory responses and offer greater flexibility with even single cell resolution. Over the past decade, optogenetics, or genetic engineering that allows for optical control of cellular activity, has been able to address many of the aforementioned issues with physical electrodes14–17. However, neuromodulation methods that rely on genetic modifications are technically challenging on larger-brained mammals as they may produce unpredictable or even permanent side effects, and are controversial if applied to human subjects. On the other hand, non-genetic photostimulation approaches could revolutionize the field of neuromodulation, especially when minimally invasive, tightly integrated with the target biological system, and able to achieve a high spatiotemporal resolution. Unlike optogenetics that expresses light-gated ion channels or pumps on the cell membrane, non-genetic photostimulation does not alter the biological targets, but instead uses the transient physicochemical outputs from synthetic materials that are attached to the cells or tissues. When the material is illuminated, its light-induced electrical or thermal output yields temporary biophysical responses (e.g., membrane electrical capacitance increase) in neurons, producing a neuromodulation effect in the close proximity to the material.

So far, several light-responsive materials have been utilized for optical neuromodulation, including quantum dots, gold nanoparticles, and semiconducting polymers, and these studies have already suggested the enormous potential of using non-genetic neuromodulation towards fundamental neuroscience and prosthetic applications. For example, cadmium selenide (CdSe) quantum dots in a nanorod geometry were able to efficiently elicit excitation of retinal ganglion cells in light-insensitive chick retinas with photostimulation18. In another study, gold nanoparticles deposited on top of primary dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons from neonatal rats and mouse hippocampal brain slices were used to elicit action potentials in the target neurons via laser stimulation. Furthermore, it was shown that the nanoparticles could be bound to specific cell types of interest via chemical surface modification with neurotoxins and antibodies19. Finally, the production of photocurrents from poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) semiconducting polymer films were used to restore light sensitivity in retinal explants from blind rats and even rescue visual functions in vivo20,21.

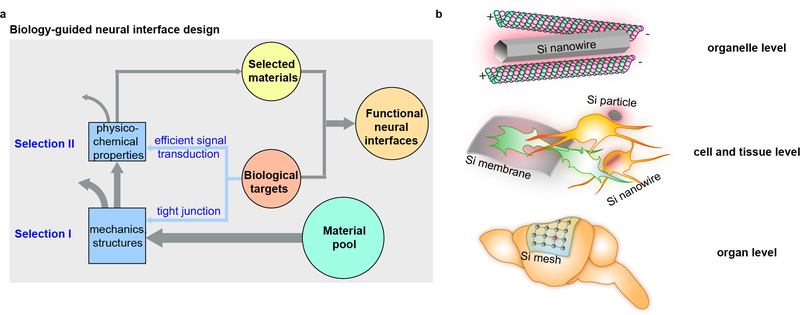

Besides these existing platforms, Si-based nanostructured materials possess some unique properties that are particularly suited for optical neuromodulation. For instance, Si can be easily fabricated into multiple forms with highly tunable chemical and physical properties and good biocompatibility22–26. Si can also absorb a broad band of light up to near infrared (NIR)27,28, which is particularly suitable for in vivo applications given living mammal tissues absorb and scatter less light in this regime29,30. Indeed, the photovoltaic, photoelectrochemical, and thermal properties of Si have been explored thoroughly in the context of energy sciences31–34. However, a precise understanding of Si-based biomaterials and biointerfaces, especially at the nanoscale level, has remained elusive. Recently, we have borrowed concepts from energy sciences and developed a set of Si-based biomaterials, including mesoporous particles35 and coaxial nanowires36, that can achieve optical induction of action potentials in single cells. Furthermore, we have systematically screened a wide variety of Si structures with unique compositions, surface chemistries, and geometries in order to formulate a biological application-guided rational design principle for establishing intra-, inter-, and extracellular neural interfaces (Figure 1a)37. This work has enabled us to non-genetically and optically modulate cellular calcium dynamics, neuronal excitability, neurotransmitter release from brain slices, and brain activity in vivo (Figure 1b)37. In this protocol, we present detailed procedures for 1) the synthesis and fabrication of several unique Si materials, 2) the evaluation of material photo-responses, 3) DRG neuron cell culture and brain tissue harvesting, and 4) optical modulation of single cell and brain tissue excitability, as well as animal behaviors. The entire procedure takes ~ 4–8 days in the hands of an experienced graduate student who has been trained in electrophysiological and optic techniques, depending on the specific biological targets (i.e., single cells, tissue slices or animals). We anticipate that our approach can be adapted to other cellular systems, such as cardiovascular tissues or microbial communities, in the future.

Figure 1. A rational design principle of Si structures for optically-controlled neuromodulation.

a, A schematic diagram illustrating the biology-guided neural interface design. The biological targets place criteria on the material structure (Selection I) and function (Selection II) to establish functional neural with efficient signal transductions across the tight junctions upon light illumination. b, Selected Si structures in this protocol for optically-controlled neuromodulation. They are nanowires (Steps 83–90) for organelle level interfaces, nanowires (Steps 61–75), particles (Steps 61–75), and membranes (Steps 76–82 and Steps 91–105) for cell and tissue level interfaces, and meshes (Steps 106–122) for organ level interfaces. a and b are adapted with permission from Ref.37, Nature Publishing Group.

Overview of the procedure

This protocol comprises of four major blocks that are connected in series (Figure 2). First of all, the material preparation part includes the synthetic methods for a spectrum of Si materials and devices. These include mesoporous Si particles (Steps 1–12), coaxial Si nanowires (Steps 13–18), Si diode junction membranes (Steps 19–24), and distributed Si meshes (Steps 25–43). Specifically, Si particles and nanowires are used for single cells, along with membranes for cell cultures or brain slices, and meshes for brain tissues in vivo (Figure 1b and Figure 2). The photo-response evaluation section introduces a universal measurement and analysis technique that can quantify individual photo-responses of each Si materials (i.e., photocapacitive, photofaradaic, and photothermal), that will form the basis for their corresponding applications (Steps 44–50). We then described the preparation of different neural systems including cultured DRG neurons from rats (Steps 51–60), mouse brain slices (Steps 91–95), and live mouse brains (Steps 106–112). The last part encompasses the detailed procedures of using the aforementioned Si materials for optical neuromodulation (Steps 61–122). These include photostimulation of cultured DRG neurons (Steps 61–90), acute brain slices (Steps 96–105), and brain cortex in vivo (Steps 113–122).

Figure 2. Schematic overview of the entire protocol.

Four major blocks of procedures are illustrated on the left side, with details of different combinations between Si materials and neural systems connected on the right side.

Alternative methods

Current neuromodulation techniques are mostly based on electrical stimulation, such as patch-clamp or multi-electrode arrays (MEA) for cultured neurons and deep brain stimulation for in vivo studies. Patch clamp is highly efficacious, especially in the context of biophysical studies and single ion channel studies, and can be used to both depolarize and hyperpolarize cells38,39. However, patch clamp is a highly invasive technique and is only suitable for short-term experiments. Another significant drawback of patch clamp is that the throughput of this technique is extremely low. It normally takes minutes to patch one single cell and it would be extremely difficult to patch multiple cells at the same time, not to mention large-scale modulation of a cell population or even a small tissue. To address the invasiveness and scalability issues, MEA can be used since extracellular electrode arrays can non-invasively depolarize cell membranes at different locations where cells and electrodes form junctions40–42. However, as MEA has limited electrode number and area coverage in cell cultures, a high-density stimulation with random-access capability is hard to achieve. Deep brain stimulation has already been shown effective in treating a number of neurological disorders1,3 but the approach is limited by the fact that stimulation electrodes need to be tethered to electrical wiring. Furthermore, the bulky and rigid nature of these electrodes can induce severe inflammation in target tissue, which is deleterious for the long-term studies and treatment of diseases.

Given the intrinsic limitations of electrical stimulation approaches, in particular the need for external wiring, wireless neuromodulation techniques have been emerging as promising alternatives towards both cell-level fundamental studies and organ-level therapeutic benefits. Typically, wireless platforms include the use of light18–21,35–37,43, magnetic fields44–46 or acoustic waves47–51. For example, the Anikeeva group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has used the magnetothermal property of ferrite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles to control intracellular calcium fluxes in neurons. By exposing the nanoparticles to alternating magnetic fields, heat-sensitive ion channels open to induce neural actitivity44. This method allows for the remote control of excitability in specific neurons and could be particularly advantageous for deep brain stimulation, because the alternating magnetic fields in the low radiofrequency range penetrate deep into tissue without significant attenuation44. Another methodology that has shown significant promise is ultrasonic neuromodulation. Recent studies from the Tyler group at Arizona State University have demonstrated that focused ultrasound can stimulate neurons in brain slices and even in human brains47,52. Although transcranial ultrasound stimulation can modulate activities as deep as 3 cm in the human somatosensory cortex, it suffers from a limited lateral spatial resolution of several millimeters, which may be insufficient to obtain precise neuromodulation.

Within the area of light-based technologies, the development of optogenetics in the early 2000s represented a huge leap forward14–16. Optogenetics-based neuromodulation is performed by introducing light-activatable ion channels or pumps into target cells that may be either excitatory or inhibitory for neuronal activity15,16. This technique has been used both for single cell studies and tissue-level studies in vivo and has the advantage of being able to target specific cell types with a high spatiotemporal resolution17,53–55. To overcome the need for genetic engineering, which is difficult to implement in humans for the purpose of clinical therapeutics, material-based platforms have emerged in the field of light-based neuromodulation19–21,43,56–62. Two pertinent examples of these methodologies include the use of gold nanoparticles, for photothermal neuromodulation mediated by a change in membrane capacitance (optocapacitance) in both DRG neurons and brain slices19, as well as semiconducting polymers, such as poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT), for photovoltaic restoration of light-sensitivity in retinal slices of blind rats20. These methods are highly versatile in that they can be applied in free-standing or substrate-based configurations, bypassing the need for gene transfection to photo-sensitize the target cells.

We appreciate that the current protocol only describes one system of remotely controlled non-genetic neuromodulations. Future development of other material systems that can effectively convert external physical inputs into output signals that are recognizable by the biological systems—in combination with advanced imaging and recording techniques—may ultimately lead to an integrated system for multimodal neuromodulations.

Applications

Our studies have demonstrated a class of new technologies for use in neural engineering, especially for the control of neuronal membrane potential and excitability, which are broadly applicable to both fundamental electrophysiological studies and light-controlled therapeutics in the clinic. These Si-based materials can be used for the modulation of cellular excitability—not just in the brain or central nervous system—but potentially also in any other electrically active parts of the body such as the peripheral nervous system, the musculoskeletal system, the cardiovascular system, the visual system, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or even the immune system. For potential clinical therapeutics, we have shown that these materials can be implanted surgically. Surface modification of the Si in the future may even realize cell type-specific targeting upon Si administration. Si-based optical modulation of cellular activity could be particularly advantageous in the context of peripheral nerve diseases. These may include diabetic peripheral neuropathy, wound healing processes on the skin, or the restoration of vision as near infrared light can penetrate well into these areas and can be absorbed well by Si. Concerning applications in the deep brain (seizure disorders or Parkinson’s disease), in the GI tract (motility disorders) or in the heart (cardiac arrhythmias), Si materials could provide a less immunogenic way to modulate cellular activity as they are highly biocompatible; however, the implantation of a light source at the site of injury may be required.

Si materials can also revolutionize the ways in which fundamental bioelectric studies are conducted as they can remain inert inside of cells or tissues until being triggered to alter the local electrical environment. This minimal invasiveness allows for minor or no alteration in cellular viability upon interfacing with cellular systems and while modulating cellular activity, thus permitting studies that can connect cellular electrical signatures with other biochemical signal processes. This advantage is particularly relevant in the context of non-excitable cells that do not produce action potentials upon membrane depolarization.

Advantages and limitations

Compared to electrical stimulation for in vitro studies, optical stimulation cannot only function in a minimally invasive manner but also achieve targeted modulation of specific cells with programmed spatiotemporal profiles. In particular, for cells cultured on Si substrates, a focused laser spot can easily move around the substrate using a laser scanning system and, therefore, stimulate any cell of interest at any time. Owing to the high flexibility of optical stimulation, our approach can also be used for the sequential excitation of calcium dynamics from user-defined locations (see Steps 76–82 for this procedure).

Compared to magnetic and ultrasonic stimulation, optical stimulation has several unique advantages. Specifically, the ability to finely focus the size and precisely tune the power and duration of the light stimulus allows for a high spatial resolution and a fast temporal response from target cells. For example, mesoporous Si particle or Si nanowire based optical neuromodulation of cultured neurons can achieve a one light pulse/one neural spike temporal precision and a subcellular resolution35,36. In contrast, existing magnetothermal stimulation methods depend on a high expression level of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) channels and thus may still require genetic transfection of the target cells44. In addition, unlike the rapid photothermal process, magnetothermal stimulation is typically slower and therefore elicits cellular responses with a higher latency. On the other hand, the exact mechanism of ultrasound-based stimulation is still under debate63,64. For the brain, cortical stimulation using distributed p-i-n Si mesh with 500-µm islands, the size of the light-spot is the limiting factor for spatial stimulation resolution, which is typically around 200-µm. This level of spatial precision is substantially better than the alternative ultrasonic or magnetic stimulation, whose resolution is on the order of millimeters47.

The Si-based approach has certain advantages over other optical stimulation approaches, such as optogenetics. The principal advantage being that there is no need for gene transfection, a process that can be difficult to implement in certain cellular systems, animal models, and in human patients. Furthermore, genetic modification may also have unpredictable consequences for the biophysical properties of the target cell membrane and spatial organization of other transmembrane proteins. Given the rich physicochemical properties of Si-based materials, instead of altering the membrane properties of the biological system, the materials themselves can be tailored to exhibit multiple functions that can achieve neuromodulation of native membranes via various mechanisms, such as photocapacitive, photoelectrochemical, and photothermal processes.

Finally, Si is particularly well suited for optically-controlled neuromodulation compared to other materials. As an inorganic semiconductor, Si can produce thermal, capacitive and Faradaic effects in saline, as opposed to metals, such as Au, that typically only yield heat upon illumination19,65. The Si surface chemistry can also be tuned in a wide range to achieve different photo-response profiles20,21,43,61,62. Second, Si materials and devices with various feature sizes and geometries can be fabricated easily following well-established industrial- or lab-scale processes. For other inorganic semiconductors (such as InP) and semiconducting polymers, despite the fact that they can exist in similar forms with Si, their fabrication procedures are usually more costly and sophisticated. This is particularly the case when nanoscale devices are needed for precise subcellular biophysical studies. Lastly, Si is both biocompatible and biodegradable, an important factor that promises for future transient neuromodulation.

Certain limitations of our current method include the shallow penetration depth of the visible light source in brain tissue and the lack of cell-type specific targeting. Given the small bandgap of Si (~ 1.1 eV), it can absorb light up to the NIR region, providing the potential for minimally invasive deep brain neuromodulation using transcranial photostimulation. In the future, we expect that the surface of Si substrates can be modified with antibodies or other membrane affinity moieties to realize targeted non-genetic neuromodulation.

Experimental design

Subjects.

We have previously used our optically-controlled neuromodulation protocols in cultured DRG neurons from rats35,36 (Sprague–Dawley, neonatal pups up to 3 days old), harvested brain slices from euthanized mice37 (C57BL/6J, 6–9 weeks old), and deeply anesthetized mice37 (C57BL/6J, 6–9 weeks old). These subjects were chosen due to the ease of tissue harvesting and surgical procedures. Although we focus on rodents in this protocol, we anticipate that the techniques described here can also be adapted to various other species ranging from Caenorhabditis elegans or zebrafish to non-human primates—or even humans, since there is no need to develop species-specific genetic engineering toolkits. All animal studies described in this Protocol followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and Society for Neuroscience. All rat procedures described here were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Chicago, and all mouse procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Material designs.

As one of the most thoroughly studied semiconductors, Si possesses many unique physical and chemical properties that are suitable for optically-controlled neuromodulation. Si is biocompatible and biodegradable, shows prominent responses upon light illumination, and can be easily fabricated into various forms. Biological systems are hierarchical in nature and span multiple length scales from submicron-scale organelles to centimeter-scale organs. Therefore, efficacious neuromodulation can only be achieved when the structures and properties of Si are compatible with the biological targets.

When designing a Si material, matching the mechanical properties of the material with those of the biological target is the first consideration. For example, the bending stiffness of a 2D sample scales with the cube of its thickness as defined by , where D is the bending stiffness, E is the Young’s modulus, h is the thickness, and ν is the Poisson ratio66. Therefore, only a thin membrane of Si can form a conformal interface with a soft and curvilinear tissue, such as a brain cortex. In another scenario, to enable intracellular biointerfaces, Si nanowires can be considered since they may be readily trapped within the cytoskeletal filaments due to their nanoscale anisotropic geometries.

After the material/device geometries are determined, another crucial criterion for neuromodulation is the fundamental photo-response produced by the Si material, a process that is the driving force in the modulation of activity of the target biological system. Our recent studies demonstrated that Si can induce different processes near its surface upon light illumination, such as capacitive coupling, redox reaction, and local heating37. We later uncovered that it is possible to skew the output of a Si material towards one of these processes by altering fundamental components of the Si materials, including size, doping profiles, and surface chemistry. Finally, we formulated a generalized biology-guided rational design principle for Si structures to form tight junctions with biological systems in order to promote efficient signal transduction across the resultant bio-interfaces.

Preparation of Si materials.

In prior works, we used chemical vapor deposition (CVD) to directly grow Si from a gaseous precursor, silane (SiH4)35–37,67. It is a highly versatile approach that may be extended to a wide variety of substrates to prepare different Si structures such as nanowires, mesoporous particles, and diode junctions (Figure 3). During the synthesis process, a number of parameters such as the chamber temperature and pressure, gas flow rates, and dopant concentrations can be controlled to precisely tune the structures and properties of the resultant Si material. Besides home-built CVD systems, commercial ones with proper gas inlet and temperature control can also work for the Si growth (see Equipment). Other synthetic methods such as chemical reduction and electrochemical etching may also be adopted to expand the Si material library for neuromodulation.

Figure 3. Experimental setup for the CVD growth of Si materials.

a, A schematic diagram of the home-build CVD system. Three subsystems for gas delivery, reactor, and pumping are highlighted. b, A schematic diagram of the gas flow valve manifolds, including the pneumatic valves, mass flow controllers, and manual valves. c, A photograph of the CVD control modules for the vacuum level, gas flow rates, and valves of the growth chamber. d, A photograph of the growth chamber (i.e., a quartz tube), the tube furnace for temperature control, gas flow valve manifolds, vacuum and pressure transducer, and the vacuum sensor. The orange box marks the region with detailed schematics in b. e, Photographs showing the growth substrates for Si materials. Mesoporous SiO2 template inside an inner quartz test tube can be used for porous particle growths. A Si wafer placed at the center of the quartz tube can be used for both nanowire or membrane growths. a is adapted with permission from Ref.67, Nature Publishing Group.

For mesoporous Si particles (Steps 1–12), a hard-template nanocasting process is adopted by decomposing SiH4 inside the channels of pre-formed mesoporous silica (SiO2) templates, including but not limited to SBA-1568 or KIT-669. Removal of the SiO2 template then yields an amorphous and mesoporous Si with the inverse structure (Figure 4a). The as-prepared Si particles have both structural and chemical heterogeneity within the porous framework and display a significant reduction in surface stiffness when compared to solid single crystalline Si.

Figure 4. Structural characterizations of Si material building blocks.

a, Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image (left), transmission electron microscope (TEM) image (middle), and atom probe tomography (APT) reconstruction (right) of mesoporous Si particles produced in Steps 1–12. The particles are consisting of aligned Si nanowire bundles with a hexagonal mesoscale ordering. Scale bars, 100 nm (left); 100 nm (middle); 20 nm (right). b, SEM (left), side-view TEM (middle), cross-sectional TEM (upper right), and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern (lower right) of coaxial Si nanowires produced in Steps 13–18. These nanowires have a single crystalline core and a nanocrystalline shell. Notably, both the dopant type and concentration can be controlled during the CVD growth to yield uniformly doped or diode junction structures. Scale bars, 1 µm (left); 100 nm (middle); 50 nm (upper right). c, TEM, SEM, and SAED of a p-i-n Si diode junction produced in Steps 19–22. The nanocrystalline intrinsic and the n-type layers were grown epitaxially from a single crystalline p-type SOI wafer as evidenced by the SAED patterns taken at different locations of the diode junction. Scale bars, 200 nm (upper left); 200 nm (upper right). a is adapted with permission from Ref.35, Nature Publishing Group. b and c are adapted with permission from Ref.37, Nature Publishing Group.

For Si nanowires (Steps 13–18) to promote light absorption, we grow nanocrystalline coaxial nanowires instead of single crystalline ones31. Briefly, after the gold-nanocluster catalyzed vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) growth of the single-crystalline core, nanocrystalline shell layers are deposited through a vapor-solid (VS) mechanism at a higher temperature (Figure 4b). Besides uniformly doped Si structures, p-i-n coaxial nanowires can also be synthesized by sequentially flowing in dopant gases such as diborane (B2H6) and phosphine (PH3).

For Si diode junctions (Steps 19–22), a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer is used as a substrate where polycrystalline Si is directly deposited onto the device layers of SOI wafers (Figure 4c). After the CVD growth, post-treatment of the Si surfaces can provide another dimension of control for the material photo-responses. For example, electroless deposition of noble metals such as gold (Au), platinum (Pt), and silver (Ag) can be performed through galvanic displacements to tune the surface chemistry (Steps 23–24). The as-synthesized Si diode junctions can be microfabricated into various geometries, such as meshes, through standard photolithography, metallization, and etching procedures to create a flexible form of Si devices (Steps 25–43) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The fabrication process of the PDMS-supported Si mesh (Steps 25–43).

Fabrication of the distributed Si mesh through photolithography (Steps 25–29), RIE (Steps 30–31), and wet etching (Steps 32–33) processes. Fabrication of the holey PDMS membrane using soft lithography (Steps 34–39). Transfer of the Si mesh onto the PDMS membrane (Steps 40–43) and corresponding photos and SEM image of the final device. Photomask designs for the Si mesh and the SU-8 pillar array are included. Black denotes chromium; White denotes the exposed area on the soda lime glass mask. Scale bars in 7/VII, 500 µm (left); 2 mm (upper right); 200 µm (lower right). Adapted with permission from Ref.37, Nature Publishing Group.

Assessment of Si photo-responses.

In this protocol, we also describe our measurement and analysis procedures that can quantify individual photo-responses of Si materials (Steps 44–50). Experimentally, we evaluated the light-triggered physicochemical processes from the Si surfaces using the patch clamp technique, since it is capable of detecting subtle changes of electrical currents in a highly localized area. Typically, Si materials with different compositions or structures were first immersed into a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution before glass micropipette electrodes were positioned at the close proximity to the material surfaces (~2 µm). Ionic flows through the pipette tips were then continuously monitored in the voltage-clamp mode. In the middle of a trial, light pulses from either a laser or a LED were delivered through a microscope objective onto the Si material while the ionic current dynamics was recorded under different pipette holding levels (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Experimental setup of the photo-response measurement (Steps 44–50).

a, Schematic diagrams illustrating the measurement configuration. Light pulses (530 nm LED or 532 nm laser) are delivered through a water-immersion objective to the Si material immersed in a PBS solution. A glass micropipette is placed near the material surface with a ~ 2 µm distance. Light-induced currents are recorded at different pipette command potentials (Vp) under a voltage-clamp mode. Rfeedback is the resistance of a feedback resistor for the amplifier. b, Front view of an upright microscope showing the light path for the laser stimulation. c, Side view of the microscope showing the light path for the LED stimulation. d, A photograph of a micro-manipulator controller (to move the micropipette), an amplifier (to record ionic currents), and a digitizer (to send TTL signals for light pulse controls and to interface the amplifier and the computer). a is adapted with permission from Ref.37, Nature Publishing Group.

For Si materials, our measurements suggest that a p-i-n diode junction is critical to producing pronounced capacitive currents37. Compared to a uniformly doped p-type Si, the built-in electric field of the diode junction can effectively separate light-generated charge carriers, and result in more charges being accumulated at the Si/saline interface. With the deposition of metallic species over the Si surfaces, both the capacitive and Faradaic effects can be further enhanced, likely due to a more efficient charge carrier collection and solution injection37. Next, with the fixed composition, the reduction of Si sizes will promote the photothermal effect and thwart the photovoltaic effect since Si with a smaller dimension will naturally have a deficiency of available carriers and an impeded heat dissipation within the confined volume of Si37. Therefore, a Si nanowire will exhibit a substantially higher thermal output upon light illumination when compared to a bulk Si. In addition to size reduction, the introduction of porosity can also significantly improve the Si photothermal effect by promoting light absorption and reducing thermal conductivity and heat capacity35,70 (BOX 1).

BOX 1. Analysis of the photo-response measurement.

In a typical measurement, the pipette potential is first held at a fixed level (Vp) and gives rise to a dark state current (I0). In the middle of the trial, a light pulse with a certain duration is delivered to the Si material to induce the light-generated current (ΔIlight(t)). One important note is that, during the light illumination period, both the photovoltaically-induced currents and the photothermal heating due to the Si material can contribute to (ΔIlight(t)). The first part is apparent since the counterions in the saline will naturally be attracted due to the photovoltaically-induced surface potential changes. The second part is implicit since the photothermal effect itself does not directly induce ion flows. Rather, the locally elevated saline temperature will increase the ion mobility, and therefore result in a reduced pipette resistance R. Under the fixed Vp, the current flowing through the tip during the light illumination period will be higher than I0. Governed by the Ohm’s law, the amplitude of the photothermally-induced ionic current (ΔIthermal(t)) will be proportional to the holding potential Vp while the photovoltaically-induced ionic currents (ΔIelectric(t)) is only a function of the carrier dynamics on the Si surface and independent of the pipette holding level.

Given the drastically different dependence on the holding potential, the photovoltaic and the photothermal effects of Si may be potentially decoupled by analyzing the recorded currents at different holding potentials. During the light illumination, the recorded current (I0+ ΔIlight(t)) at a given time point excluding the photovoltaically-induced current (ΔIelectric(t)), and the pipette tip resistance R(t) will follow the Ohm’s law when the holding potential Vp is fixed.

| (1) |

Eq. 1 can be rearranged to better describe the relationship between the light-induced current ΔIlight(t) and the holding current I0 that

| (2) |

As shown in Eq. 2, the photovoltaic effect is clearly shown by the intercept of the curve. Depending on the temporal scale and the amplitude of the currents, two subtypes of the photo-responses, i.e., capacitive and Faradaic, can be further defined. Briefly, the spiky features near the onset and offset points of the light illumination are capacitive currents from the capacitive charging/discharging processes at the Si/saline interface (BOX Figure panel a, top). A long-lasting current with a lower amplitude is the Faradaic current from the surface redox reactions (BOX Figure panel b, top).

The photothermal effect, however, is implicitly embedded in the fitted slope as the pipette resistance is a function of temperature (BOX Figure panel c, top). The amplitude of the photothermally-induced temperature change from the surrounding medium can be calculated as long as relationship between the pipette resistance and the temperature is calibrated, which typically follows the Arrhenius equation85 that

| (3) |

where a and c are the slope and intercept values, respectively. Combining with the slope k(t) from the ΔIlight(t) - I0 plot that

| (4) |

the temperature value of the surround medium due to the photothermal heating can be expressed using the slopes of the ΔIlight(t) - I0 and the lnR - 1/T curves as well as the initial temperature that

| (5) |

Taken together, plotting the ΔIlight(t) - I0 curve can serve as a general method to assess the photo-responses of various Si materials and, most importantly, it can be applied to virtually all kinds of materials other than just Si. Since the photothermal effect is a function of the illumination duration (i.e., the heat source for Fourier thermal conduction), the slope of the ΔIlight(t) - I0 plot is also time dependent. The maximal temperature is reached at the end point of illumination so one can simply plot the ΔIlight,t(end) - I0 curve to assess the photothermal responses of the material. The following four categories summarize the possible photo-responses of the ΔIlight(t) - I0 plotted at the end point of the light illumination tend.

1) In one extreme scenario where the material has only the photovoltaic effect without any photothermal effect, i.e., , Eq. 2 can be written as

| (7) |

The plot will be a horizontal line with a non-zero intercept. For example, pure capacitive responses generated from p-i-n diode junction membranes under LED illumination (BOX Figure panel a, bottom) or both capacitive and Faradaic responses generated from metal-decorated p-i-n diode junction membranes under LED illumination (BOX Figure panel b, bottom).

2) In another extreme case where the material has only the photothermal effect without any photovoltaic effect, i.e., ΔIelectric = 0 at all time, Eq. 2 will be reduced to

| (6) |

The plot will be a slanted line with a zero intercept. For example, the pure thermal responses generated from intrinsic coaxial nanowires or mesoporous particles under laser illumination (BOX Figure panel c, bottom).

3) If a material does not have any photo-responses, Eq. 2 will be

| (8) |

The plot will be a horizontal line with a zero intercept.

4) In any intermediate situations where both the photovoltaic and the photothermal effects coexist, the original form of Eq. 2 applies that

| (9) |

The plot will be a slanted line with a non-zero intercept.

Fundamental physicochemical processes occurring at the Si surface upon light illumination and general strategies to promote individual photo-responses are summarized in BOX Figure panel d as a selection guide for particular neuromodulation applications33.

Besides the intrinsic properties of Si itself, another important factor that can significantly affect the Si photo-response is the light source, especially for Si structures with smaller dimensions. For a coaxial nanowire or a mesoporous particle, only tightly focused lasers can generate pronounced photo-responses; LED illumination, on the other hand, does not induce any detectable signals. Correspondingly, laser illumination on these small objects will evoke a higher thermal response due to the substantial number of photons being absorbed and the lack of efficient heat dissipation. For a bulk Si diode junction membrane, however, even diffused LED illumination can generate a high amplitude of photocurrent with almost no thermal response (BOX 1).

In vitro experiments on neuron cultures.

In vitro experimentations on cultured neurons is the easiest way to test the feasibility of Si-based photostimulation (Steps 51–90). Using DRG neurons harvested from neonatal rats, we previously demonstrated the successful modulation of cultured neural activities by eliciting action potentials and calcium dynamics. Compared to hippocampal or cortical neurons in the brain, DRG neurons can easily be extracted from the spine without the need for complicated dissections of other parts of the central nervous system (Steps 51–60). For nanostructured materials (e.g., mesoporous Si articles, coaxial Si nanowires), an aqueous suspension of Si is applied to the DRG culture in a drug-like fashion and the Si materials are let to settle onto the cells. Normally, extracellular interfaces with neurons can be formed within ~ 30 min and target cells are then photostimulated by delivering a laser pulse to a cell membrane-supported Si material interacting with a single cell (Steps 61–75) (Figures 7a–c). Due to the unique anisotropic geometry of Si nanowires, they can also be internalized by glial cells, naturally occurring in culture, after ~ 24 h of coculture to form intracellular biointerfaces (Steps 83–90).

Figure 7. Experimental setups for the in vitro photostimulation of cultured neurons (Steps 51–90).

a, Schematic diagrams illustrating the connections between individual pieces of equipment of the patch clamp setup. Si particles and Si nanowires can be applied onto a cultured DRG neuron for the photostimulation with laser pulses. A1 and A3 are high gain amplifiers whereas A2 has gain of one and it just works as a differential amplifier. b, Photographs of the associated amplifier, AD/DA converter, waveform generator, and the AOM controller (left) and the inverted microscope equipped with a laser setup for the photostimulation experiment (right). c, Photographs highlighting important components of the setup, including the 532 nm laser and the AOM (left), the ND filters (middle), and the electrodes (right). d, Photographs of an inverted laser scanning confocal microscope that can monitor calcium dynamics during the photostimulation experiment (top). A 592 nm stimulated emission depletion (STED) laser is used as the stimulation light source, and the laser scanner allows arbitrary aiming of the laser spot onto the point of interest for the stimulation (bottom). a is adapted with permission from Refs.35,36, Nature Publishing Group.

In a typical extracellular photostimulation experiment, the electrophysiological responses of the cell can be investigated using the patch clamp technique. When the neuron under illumination is patched in whole cell current clamp mode, by sweeping the laser duration or power, the cell membrane can be passively depolarized to its excitability threshold for action potential firing (Steps 64–75). For the intracellular biointerfaces with glial cells, calcium imaging is typically used to study the stimulation effect since a network level calcium wave propagation can better demonstrate the remote neuromodulation through natural junctions between glia and neurons (Steps 83–84) (Figure 7d). Wafer-scale Si diode junctions can directly serve as the substrate for neuron culture. One advantage of this two-dimensional biointerface is that the laser spot can be arbitrarily aimed at different positions where the cell and the Si form a junction. In this way, we were able to show that calcium waves can be sequentially initiated with a high spatiotemporal resolution (Steps 76–82).

Ex vivo experiment on brain slices.

Utilizing the information from cultured neurons, photostimulation of a small tissue, such as a brain slice, is also possible. In this case, we used a Si mesh fabricated from a p-i-n diode junction (from Steps 25–33) for the photostimulation. In principle, the diode junction does not need to be lifted off the handling wafer. In our particular setup, however, the infrared (IR) light for the brain slice imaging comes from the bottom of the microscope such that the Si material should be at least partially transparent to form a decent cell image (Figure 8). The Si membrane is placed underneath a 300-μm slice and the membrane current of a neuron in the middle of the slice is recorded under the voltage clamp mode (Steps 91–105). In this configuration, the recorded neuron is not in direct contact with the Si membrane. Immediately after illuminating the Si mesh, both the photocapacitive artifacts and the excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) can be recorded with short temporal delays, meaning that the photostimulation only excites the presynaptic neurons to induce ESPCs, rather than directly evoking spikes, in the recorded postsynaptic neuron. This suggests the possibility of using the Si diode junction as a localized neurostimulator for high spatiotemporal resolution mapping of functional neural circuits.

Figure 8. Experimental setup for the photostimulation of acute brain slices (Steps 91–105).

a, A schematic diagram of the photostimulation setup and optical micrographs showing the Si/slice interface and the patched neuron. Scale bars, 250 µm (upper right); 10 µm (lower right). b, A photograph of an upright microscope equipped with an 850 nm IR LED for imaging. c, A photograph of external devices to control the stimulation light sources (473 nm laser or multi-wavelength LEDs), the Pockels cell for laser modulation, the stage heater, and the micro-manipulator for the photostimulation experiment. d, Side views of the microscope showing the light paths for LED (top) and laser (bottom) stimulation. The laser scanning system allows the photostimulation of multiple sites of the Si mesh for functional circuit mapping. a is adapted with permission from Ref.37, Nature Publishing Group.

In vivo experiment on brain cortex.

An important potential application of Si-based neuromodulation is in intact brain circuits, which entails translating the methodology to a live animal model. Compared to the deep brain regions, the brain cortex is easier to access with the Si diode junction thin membranes and the photostimulation platform. Since the traditional stimulation electrode for excitable tissue typically require high capacitive and Faradaic currents for efficacious neuromodulation, we use the Au-decorated p-i-n diode junction (from Steps 19–22) as it outputs the maximal currents under light illumination. In addition, we adopt a bilayer device layout consisting of an Au-decorated Si mesh and a holey polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane (Steps 25–43), a configuration that allows both high flexibility and good handling capability. Notably, the p-type side of the diode junction is in contact with the PDMS membrane while the n-type side faces the brain cortex to photocathodically modulate neural activities37, similar to the cathodic electrical stimulation71. The holey structure of the PDMS not only reduces the bending stiffness of the membrane, but also provides paths for the artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) to contact the p-side of the Si mesh and consume the excess holes under illumination.

In our in vivo photostimulation experiments, we use a laser scanning system that can easily move the light spot to stimulate different brain regions, such as the somatosensory and the motor cortices, with a single Si mesh attached. To read out the brain activities, extracellular linear arrays are inserted to record neural activities following laser illumination of the somatosensory cortex (Figure 9). In individual trials, enhanced neural activities are evident during the illumination period—with significant photocapacitive artifacts at the light onset and offset points. Importantly, parametric stimulations show that the evoked neural response rate is highly correlated with the stimulation strength, which is essential to using the Si mesh as a precise neuromodulator37. For the motor cortex, evoked movements can serve as direct evidence of the stimulation effect; in the example in our studies we focus on forelimb movements for the ease of video capture (see Anticipated Results).

Figure 9. Experimental setup for the in vivo photostimulation experiment (Steps 106–122).

a, A block diagram of the entire setup combining the laser scanning photostimulation (LSPS) system, the linear array system with five probes for electrophysiology, the video system, the input/output (I/O) interface, and the graphical user interface (GUI). b, A schematic diagram highlighting the layout of the photostimulation experiment. The mouse brain covered by the Si mesh is stimulated by the laser from the scanning assembly and a linear array recording electrode is inserted into the nearby cortex. c, Photographs of the operating platform overview (left), highlighting the laser scanning assembly (middle), and the electrophysiological recording geometry (right). d, Photographs of the I/O interface (left) and the GUI (right) for controls of manipulators, laser scanning, electrophysiology, camera, and data analysis. b is adapted with permission from Ref.37, Nature Publishing Group.

Materials

Biological materials

-

Rats for cultured neuron photostimulation (Sprague-Dawley, P0-P3, Charles River Laboratories)

!CAUTION: All experiments involving rats must conform to relevant institutional and national regulations. All animal procedures that we describe here were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Chicago.

-

Mice for brain slice and in vivo photostimulation (wild-type C57BL/6J, 6–9 weeks old, Jackson Laboratory)

!CAUTION: All experiments involving mice must conform to relevant institutional and national regulations. Animal studies followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and Society for Neuroscience, and were approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were maintained as in-house breeding colonies.

Reagents

General Reagents for multiple parts of the procedure

-

Ethanol (200 proof, Decon Labs, cat. no. 2701)

!CAUTION: Ethanol is flammable. Avoid any open flame when handling ethanol.

-

Isopropanol (IPA; Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. A451SK-4)

!CAUTION: IPA is flammable. Avoid any open flame when handling ethanol.

Hydrofluoric acid (48% (wt/vol) HF in H2O; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 30107)

-

! CAUTION: HF is extremely corrosive. Wear heavy-duty nitrile gloves, acid resistant apron and goggles when using HF. Always have Calgonate first aid and spill kits aside before handling HF. Silane (SiH4; Airgas)

!CAUTION: SiH4 is extremely flammable and toxic when inhaled. Must use specialized safety cabinets for storage and usage.

-

Hydrogen (H2; Airgas)

!CAUTION: B2H6 is extremely flammable. Must use specialized safety cabinets for storage and usage.

-

Diborane (B2H6; 100 ppm in H2, Airgas)

!CAUTION: B2H6 is extremely flammable and fatal when inhaled. Must use specialized safety cabinets for storage and usage.

-

Phosphine (PH3; 1000 ppm in H2, Airgas)

!CAUTION: PH3 is extremely flammable and fatal when inhaled. Must use specialized safety cabinets for storage and usage.

Synthesis of mesoporous Si particles

Pluronic P123 (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 435465)

-

Hydrochloric acid (HCl; 37% (wt/wt), Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 320331)

!CAUTION: Concentration HCl is corrosive. Use it only inside a well-ventilated hood.

Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 131903)

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. H9151)

n-butanol (BuOH; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. B7906)

Quartz test tube (Quartz Scientific Inc., cat. no. 315020)

Stericup Filter Units (Millipore, cat. no. SCVPU02RE)

Synthesis of coaxial Si nanowires

Poly L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. P8920)

50 nm gold colloidal nanoparticles (Ted Pella Inc., cat. no. 15708–5)

Si wafer (Nova Electronic Materials, cat. no. DN03–10624)

Tungsten carbide scriber (Ted Pella Inc., cat. no. 829)

Carbon-tipped tweezer (Ted Pella Inc., cat. no. 5052)

Synthesis of p-i-n Si diode junctions

Silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer (Ultrasil, cat. no. 6–9263)

Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4; cat no. 50790)

Potassium tetrachloroplatinate(II) (K2PtCl4; cat. no. 206075)

Silver nitrate (AgNO3; cat. no. 209139)

Fabrication of distributed Si meshes supported on holey PDMS membranes

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; World Precision Instruments, cat. no. SYLG184)

MCC primer 80/20 (MicroChem)

LOR-3A (MicroChem)

SU-8 2005 (MicroChem)

SU-8 2050 (MicroChem)

SU-8 developer (MicroChem)

Tetrafluoromethane (CF4; Airgas)

Argon (Ar; Airgas).

Remover-PG (MicroChem)

Hexane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. H292–4)

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP; average Mw ~29,000, Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 234257)

Photo-response measurement

1× Phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. SH3025602)

Dorsal Root Ganglion neuron isolationDMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 11320033)

Penicillin/Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. P4333)

Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 10438–026)

Earle’s Balanced Salt Solution (EBSS; no calcium, magnesium, and phenol red, Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 14155–063)

Trypsin (Worthington, cat. no. TRL3)

Immunofluorescence

-

4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS (with magnesium and EGTA, Alfa Aesar, cat. no. J62478)

!CAUTION: PFA is flammable and toxic. Use it only inside a well-ventilated hood.

Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. X100)

Bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A2153)

GFAP (GA5) Mouse mAb (Cell Signaling, cat. no. 3670T)

NeuN (D4G40) XP Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling, cat. no. 24307T)

Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Superclonal Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, cat. no. A28181)

Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, cat. no. R37116)

S100 Polyclonal Antibody (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, cat. no. PA5–16257)

Neurofilament-H (RMdO 20) Mouse mAb (Cell Signaling, cat. no. 2836)

Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, cat. no. A11008)

Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, cat. no. A21235)

Antifade mountant (SlowFade Diamond, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, cat. no. S36967)

Nail polish (Electron Microscopy Sciences, cat. no. 72180)

In vivo experiment preparation

-

Ketamine-xylazine cocktail (ketamine 80–100 mg/kg, xylazine 5–15 mg/kg)

!CAUTION: This is a controlled substance in many countries; in the United States, researchers must register with the DEA and obtain the applicable state license before ordering and using it.

Equipment

General Equipment for multiple parts of the procedure

KimWipes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kimberly-Clark, cat. no. 06–666)

1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific cat. no. 3448)

Si material synthesis (mesoporous particles, coaxial nanowires, diode junctions)

CVD system (Home-built). !CRITICAL Besides home-built CVD systems, commercial ones with proper gas inlet and temperature control can also work for the Si growth. Examples include systems manufactured by FirstNano or Structured Materials Industries.

Vacuum and pressure control module (MKS Instruments, cat. no. 250E-4-D)

Flow control and readouts module (MKS Instruments, cat. no. 247D)

Pirani pressure meter (MKS Instruments, cat. no. 945-A-120-TR)

Pirani vacuum sensor (MKS Instruments, cat. no. 103450214)

Automated control valve (MKS Instruments, cat. no. 148JA14CR1M)

Vacuum and pressure transducer (Baratron® Capacitance Manometer, MKS Instruments, cat. no. 626B)

Mass flow controllers (MFCs, MKS Instruments, cat. no. 1479A)

Gas flow manual valves (Swagelok Company, cat. no. 6LVV-DPFR4-P)

Pneumatic valves (Swagelok Company, cat. no. 6L VV-P1V222P-AA, 6L VV-DPC232P-C)

Tube furnace (Lindberg/Blue, Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. TF55030A-1)

Dry vacuum pump (Kashiyama-USA, Inc., cat. no. SDE120TX)

Quartz tubes (Quartz Plus, Inc., 25.3 mm OD, 22 mm ID)

Muffle furnace (Barnstead International, cat. no. FB1415M)

Si mesh fabrication

Oxygen plasma etcher (Plasma Etch, PE-100LF)

Spin coater (Laurell, WS-650)

Mask aligner (EV Group, EVG 620)

Reactive ion etcher (Oxford Instruments, Plasma Pro NGP80 ICP)

Photo-response measurement

Borosilicate patch pipettes (4-inch thin wall with 1.5-mm outer diameter (OD) and 1.12-mm inner diameter (ID), World Precision Instruments, cat. no. TW150F-4)

Upright microscope (Olympus, BX61WI)

532 nm DPSS laser (Laserglow Technologies, LRS-0532-PFM-00300–05)

Fiber port (FC/PC, f=11.0 mm, 350 – 700 nm, Ø1.80 mm waist, Thorlabs, cat. no. PAF-X-11-PC-A)

Single mode patch cables (405 – 532 nm FC/PC, 2m, Thorlabs, cat. no. P1–405B-FC-2)

FC/PC fiber adapter plate (with external SM1 thread, Thorlabs, cat. no. SM1FC)

Cage Plate (SM1-threaded 30 mm, 0.35” thick, 2 retaining rings, 8–32 tap, Thorlabs, cat. no. CP02)

Cage assembly rod (3” long, Ø6 mm, 4 pack, Thorlabs, cat. no. ER3-P4)

Achromatic doublet lens (f=45 mm, Ø1”, SM1-threaded mount, ARC: 400–700 nm, Thorlabs, cat. no. AC254–045-A-ML)

Neutral density filters (twelve station dual filter wheel for Ø1” filters with base assembly, 10 ND filters include, Thorlabs, cat. no. FW2AND)

Right-angle kinematic mirror mount (with tapped cage rod holes, 30 mm cage system and SM1 compatible, 8–32 and ¼”−20 mounting holes, Thorlabs, cat. no. KCB1)

Ø1” Broadband dielectric mirror (400 – 750 nm Thorlabs, cat. no. BB1-E02)

Lens tube spacer (SM1 without internal threads, 2.5” long, Thorlabs, cat. no. SM1S25)

Kinematic fluorescence filter cube (30 mm cage compatible, left-turning, ¼”−20 tapped holes, Thorlabs, cat. no. DFM1L)

Dichroic filter (TRITC, reflection band = 525–556 nm, transmission band = 580–650 nm, Thorlabs, MD568)

530 nm LED (mounted, Thorlabs, cat. no. M530L3)

Adjustable collimation adapter (with Ø25 mm lens, AR coating: 350 – 700 nm, Thorlabs, cat. no. SM1P25-A)

Water-immersion lens (Olympus, UMPLFLN20X/W NA0.5)

Micro-manipulator (Scientifica, PatchStar)

Headstage (Axon Instruments, CV203BU)

Amplifier (Axon Instruments, Axopatch 200B)

Digitizer (Axon Instruments, Digidata 1550B)

Automatic temperature controller (Warner Instrument, TC-344B)

Micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument, P-97)

Data acquisition software (Molecular Devices, pClamp)

Dorsal Root Ganglion neuron isolation

Glass bottom dishes (Cellvis, cat. no. D35–10-1-N or World Precision Instruments, cat. no. FD35–100)

Glass Pasteur pipets (disposable 9” borosilicate glass, Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 13–678-20D)

Forceps (Dumont #5, cat. no. RS-5035-Carbon)

Glass flat bottom vial (20 mL disposable scintillation vial, cat. no. FS74504–30)

0.22 µm filter (Millex GP, cat. no. SL9P033RS)

10 mL syringe (LuerLock Norm-ject, cat. no. 4100-X00V0)

2”×2” cotton gauze sponges (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 22–362-178)

Cell culture incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, HERACell 150i)

37 °C shaker (Denville Scientific Inc., Incu-Shaker Mini)

Alcohol burner (Hach, cat. no. 2087742)

Centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 75004505)

Cultured neuron photostimulation

Sonicator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. FB11203)

532 nm DPSS laser (Ultralasers, CST-H-532nm-500mW)

Neutral density filters (Thorlabs, cat. no. TRF90)

Pipette puller (Sutter Instrument Co., P-2000)

Borosilicate patch pipettes (4-inch thin wall with 1.5-mm outer diameter (OD) and 1.12-mm inner diameter (ID), World Precision Instruments, cat. no. TW150F-4)

Safety glasses (Thorlabs, cat. no. 390507)

Silver wire (0.005-inch diameter, World Precision Instruments, cat. no. AGT0510)

Acousto-optical-modulator (AOM) (NEOS Technologies, N48062–2.5-.55-W-10W)

Analog-to-digital/digital-to-analog (AD/DA) converter board (Innovative Integration, SBC-6711-A4D4)

Arbitrary waveform generator (BK Precision, 4075B)

Inverted microscope (Zeiss, IM 35)

Dichroic mirror (Chroma Technology Corporation)

785 nm notch filter (Chroma Technology Corporation)

Headstage (Axon Instruments, CV302BU)

Motorizers (Newport Corporation, 860)

Motorizer controllers (Newport Corporation, 860MC3)

2 mL glass syringe (Becton and Dickinson Cornwall, 3425)

Micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument, P-87)

Micro-manipulator (Newport)

Amplifier (Axon Instruments, Axopatch 200B)

Inverted confocal microscope (Leica, SP5 II STED-CW)

Data acquisition software (custom-written for electrophysiology; Leica, LAS AF for calcium imaging)

Brain slice preparation

Vibratome (Leica, VT1200S)

Brain slice photostimulation

Borosilicate glass (inner diameter 0.86, outer diameter 1.5 mm, with filament; Warner Instrument)

Upright microscope (Olympus, BX51WI)

Video camera (Q-Imaging, Retiga 2000R)

Infrared LED (850 nm, Thorlabs, M850L2)

Low-magnification objective lens (Olympus, UPlanSApp 4×/NA 0.16)

High-magnification water-immersion lens (Olympus, LUMPlanFLN 60×/NA 1.00)

In-line feedback-controlled heater (Warner Instrument, TC 324B)

Micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument, P-97)

Micro-manipulators (Sutter Instrument, MP-225, ROE-200, MPC-200)

Amplifier (Axon Instruments, Multiclamp 700B)

Blue laser (473 nm, 50 mW, CNI Laser, MLL-FN473;)

Laser scan system (Cambridge Technologies, 6210 galvanometer pairs)

Electro-optical modulator (Conoptics, 302 RM)

Mechanical shutter (Uniblitz, LS2ZM2, VCM-D1)

Data acquisition software (Vidrio Technologies, Ephus)

In vivo experiment preparation

Stainless-steel set screw (single-ended #8–32, Thorlabs, cat. no. SS8S050)

Spade terminal (non-insulated, McMaster-Carr, cat. no. 69145K438)

Optical post (1/2ʺ diameter, Thorlabs, cat. no. TR3)

Feedback-controlled heating pad (Bowdoin, FHC)

In vivo photostimulation

Blue-laser source (473-nm wavelength, ~100-mW maximum power, ~2-mm beam diameter, Aimlaser, LY473III-100)

Three-dimensional linear stage (Thorlabs, cat. no. PT3)

AOM with driver (1 µs rise time, AA Opto-Electronic, MTS110-A3-VIS)

Iris (Thorlabs, cat. no. SM1D12D)

Galvanometer scanner pairs (300 µs step response, Thorlabs, cat. no. GVSM002)

Plano-convex spherical lens (Thorlabs, cat. no. LA1484-A)

Optical post (1.5ʺ diameter, Thorlabs, cat. no. DP12A)

Bracket (Thorlabs, cat. no. C1515)

Multifunction (analogue and digital) interface board (National Instruments, NI USB 6229)

Optical power meter kit (Thorlabs, cat. no. PM130D)

Graphical user interface (GUI) control software (written in National Instruments LabVIEW program)

Microelectrode array Si probes (NeuroNexus, A1×32–6mm-50–177)

Motorized four-axis micromanipulator, assembled by mounting a linear translator (Thorlabs, cat. no. MTSA1) onto a three-axis manipulator (Sutter Instrument, MP285)

Stereoscope (AmScope, SM-4TPZ)

Amplifier board (Intan Technologies, RHD2132)

USB Interface Board (Intan Technologies, RHD2000)

Experimental interface software (Intan Technologies)

CMOS camera (FLIR Systems, CM3-U3–13Y3M-CS)

Fixed focal length lens (Navitar, 35 mm EFL, f/2.0)

Reagent Setup

Modified Tyrode’s buffer. 132 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 4 mM potassium chloride (KCl), 1.8 mM calcium chloride (CaCl2), 1.2 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 10 mM (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), 5 mM glucose, pH 7.4, 300 mOsm. This buffer can be stored up to multiple weeks at 4 oC.

Internal patch pipette solution for DRG.150 mM potassium fluoride (KF), 10 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP), 9 mM (ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid) (EGTA), 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 310 mOsm. This solution can be stored as small aliquots up to 6 months at −20 oC.

Chilled cutting solution. 110 mM choline chloride, 11.6 mM sodium L-ascorbate, 3.1 mM pyruvic acid, 25 mM sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), 25 mM D-glucose, 2.5 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM monosodium phosphate (NaH2PO4); aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2. !CRITICAL This solution can be stored up to 1 week at 4 oC but we recommend making it fresh each time before slicing.

Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). 127 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM D-glucose, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4.This solution can be stored up to multiple weeks at 4 oC.

Cesium- or potassium-based internal solution for brain slice. 128 mM cesium or potassium methanesulfonate, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM phosphocreatine, 4 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, 0.4 mM guanosine triphosphate (GTP), 3 mM ascorbate, 1 mM EGTA, 0.05 mM Alexa Fluor hydrazide; 4 mg/ml biocytin; pH 7.25, 290–295 mOsm. This solution can be stored as small aliquots up to 6 months at −20 oC.

Procedure

Synthesis of Si materials: mesoporous Si particles. Timing: 1 day

!CRITICAL Mesoporous Si is typically prepared by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) of Si inside mesoporous SiO2 templates, followed by HF etching to remove the template (Figure 3). We demonstrated the feasibility of CVD to grow mesoporous Si using a widely-used template, i.e., wheat-like SBA-15 (Ref.68) although templates with different geometries and porosities can also be used in the future.

-

1

Dissolve 4.0 g Pluronic P123 in a mixture of 108.3 g deionized (DI) water and 24.3 g concentrated HCl solution (37%, wt/wt) in a capped glass bottle at 35 oC.

-

2

After the P123 is completely dissolved, add 8.3 g TEOS and stir the mixture at 35 oC for 24 h.

-

3

Age the reaction mixtures in a sealed graduated laboratory glass bottle under static condition at 100 oC for 24 h.

-

4

Use a 0.22-µm vacuum filter to collect the white product and let it air dry.

-

5

Place the sample in an alumina crucible with a ramp rate of 100 oC min−1 until 500 oC and maintain at 500 oC for 6 h in air.

-

6

Characterize the SBA-15 template using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Expected results include wheat-like morphologies under SEM, hexagonal (end view) or parallel (side view) channels under TEM, and first three diffraction peaks with scattering vectors q following 1::2 under SAXS35.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

PAUSE POINT: Store the SBA-15 template in a dry box to avoid moisture trapping in the pores. The sample can be stored indefinitely as long as the humidity is controlled.

-

7

Load the as-synthesized mesoporous SiO2 powder close to the bottom of a quartz test tube (diameter: ~1.5 cm), which serves as the inner reactor.

-

8

Place the inner tube containing SiO2 template into the center of an outer quartz tube (diameter: ~2.5 cm), which serves as the main chamber for CVD (Figure 3c, left). During the pump down process, slowly evacuate the chamber by setting a minimal value (~ 5×10−4 Torr) for the pressure control.

! CRITICAL STEP: Avoid directly turn on the vacuum valve, which may push the inner tube off the center due to the sudden pressure imbalance.

-

9

Deposit Si at 500 oC and 40 torr using SiH4 as the Si precursor and H2 as the carrier gas. In a typical synthesis, we use 200 mg of SiO2 template, with flow rates of H2 and SiH4 set at 60 and 2 standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm), and a total CVD duration of 120 min.

-

10

Use 48% (wt/vol) HF to remove the template for 5–10 min at room temperature (20–25 °C).

-

11

Use a vacuum filter set to collect the etched sample and rinse it with DI water, IPA and dry in air. The final product is in a brownish powered form.

-

12

Characterize the mesoporous Si particles using SEM, TEM, SAXS, and atom probe tomography (APT). Expected results include wheat-like particles with aligned nanowire bundles under SEM (Figure 4a, left), hexagonal (end view in Figure 4a, middle) or parallel (side view in Ref. 35) features under TEM, first three diffraction peaks with scattering vectors q following 1::2 under SAXS35, and hexagonal organization of Si atoms under APT (Figure 4a, right).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

PAUSE POINT

Synthesis of Si materials: coaxial Si nanowires. Timing: 1 day

! CRITICAL Coaxial Si nanowires are synthesized using a gold (Au) nanocluster-catalyzed CVD growth (Figure 3). A single crystalline core is typically grown at a lower temperature (e.g., 470~485 oC) through a vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) process and nanocrystalline shells can be deposited at a higher temperature (e.g., 600~750 oC) with a vapor-slid (VS) process. During the synthesis, the dopant concentration and sequence can be controlled by the gas flow system to yield a broad spectrum of combinations such as i-i (Step 18A) and p-i-n (Step 18B) coaxial nanowires for cellular level neuromodulations (Steps 83–84 for i-i ones and Steps 61–75 for p-i-n ones).

-

13

Substrate preparation (Steps 13–18): Use a tungsten carbide scriber to cut smaller pieces of Si chips from a whole wafer (e.g., an n-type <100> substrate) as the growth substrates. A typical size of the substrate is 2×6 or 2×8 cm2 for coaxial Si nanowire growth.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

14

For a newly cut substrate, use a N2 stream to remove debris or dust. This is typically enough to clean the surface. Immerse the clean substrates into 48% (wt/vol) HF to remove the native oxide layers and blow-dry the substrate using N2.

-

15

Prepare an Au solution by mixing citrate-stabilized Au colloidal nanoparticles (e.g., 50 nm in diameter), HF, and H2O with a volume ratio of 1:4.5:4.5. The dilution ratio is empirically determined and should be re-evaluated when starting with Au nanoparticles of a diameter or concentration. Apply the mixture onto the Si substrates and wait for ~ 15 min to ensure that Au can settle down on to the Si surface without native oxide.

-

16

Gently rinse the substrate by immersing it into a DI water bath. Avoid directly squeezing water onto the substrate since this can wash away the Au catalyst. Use a N2 gun to blow dry the substrate after rinsing.

! CRITICAL STEP: Avoid using organic solvents (e.g., IPA or acetone) that may deactivate the Au catalyst.

-

17

Place the growth substrate near the center of the quartz tube and evacuate the chamber to its base pressure before ramping up the temperature to 470 oC (Figure 3c, right).

! CRITICAL STEP: Once the temperature reaches the set point, avoid excessive waiting before introducing gases to the growth chamber to minimize undesired migration and aggregation of the Au catalyst.

-

18

Preparing the nanowires (Step 18): For preparing i-i Si nanowires, follow Option A. For preparing p-i-n nanowires, follow Option B. The i-i Si nanowires have purely the photothermal effect whereas the p-i-n ones can have the photovoltaic effect on top of the photothermal one.

A). i-i Si nanowires

For an intrinsic-intrinsic coaxial nanowire growth, first synthesize the core by delivering SiH4 and H2 at flow rates of 2 and 60 sccm, respectively, and maintain the growth chamber at 40 torr under 470 oC for 20 min.

-

After the core growth, switch the SiH4 flow off and keep the chamber under a H2 atmosphere (60 sccm, 15 torr) while increasing the temperature to 600 °C for the subsequent shell deposition.

! CRITICAL STEP: The H2 atmosphere instead of vacuum during the temperature ramping can minimize Au diffusion along the nanowire.

-

At 600 oC, deposit the intrinsic shell with flow rates of H2 and SiH4 at 0.3 and 60 sccm, respectively, and a chamber pressure of 15 torr for 40 min.

PAUSE POINT

B). p-i-n Si nanowires

To synthesize the p-type core of p-i-n coaxial nanowires, introduce SiH4, B2H6 and H2 at flow rates of 2, 10 and 60 sccm, respectively, to the chamber at 40 torr under 470 oC for 30 min.

-

After the core growth, maintain the chamber in a vacuum for 20 min while increasing the tube furnace temperature to 750 °C.

! CRITICAL STEP: This vacuum annealing is critical to the Au diffusion process72.

-

For the intrinsic Si shell deposition, use 0.3 and 60 sccm flow rates of SiH4 and H2, respectively, under 750 °C at a pressure of 20 torr for 15 min. The introduction of a 1.5-sccm flow rate of PH3 for another 15 min will create the final n-type shell.

PAUSE POINT

Synthesis of Si materials: p-i-n Si diode junctions. Timing: 1 day in total

! CRITICAL Si diode junctions are prepared using the CVD method by directly depositing intrinsic and n-type layers of Si onto commercial p-type SOI wafers through a VS process. Besides doping profiles and crystallinity, the surface chemistry of the diode junction can also be tuned by post-synthesis surface treatment through electroless deposition of metallic species for in vivo applications (Steps 106–122) due to its prominent photocapacitive and photofaradaic responses (BOX 1).

-

19

For a newly cut substrate, use a N2 stream to remove debris or dust. This is typically enough to clean the surface. Immerse the clean substrates into 48% (wt/vol) HF for ~ 5 min to remove the native oxide layers and blow-dry the substrate using N2.

-

20

Place the substrate inside a quartz tube for evacuation right after the cleaning process (Figure 3c, right). This step is critical to a good photovoltaic output of the diode junction.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

21

Increase the temperature to 650 oC and, after the temperature has stabilized and the pressure reaches the minimal, deposit the intrinsic layer by introducing 0.3 and 60 sccm flow rates of SiH4 and H2, respectively, at 15 torr for 20 min.

-

22

Deposit the n-type layer with the same flow rates of H2 and SiH4 during the intrinsic layer growth plus a 1.5-sccm flow rate of PH3.

! CRITICAL STEP The as-grown diode junction can be used as it is or be surface modified to further improve its photo-response. A simple yet effective way to change the Si surface property is to perform galvanic displacement by reducing metallic precursors with surface silicon hydrides (Si-H). The metal-containing solutions can be aqueous dispersion of HAuCl4, K2PtCl4, and AgNO3 at different concentrations (0.01 mM, 0.1 mM, or 1 mM).

-

23

Prepare a plating solution by mixing the metal precursor with HF. The typical metal concentration is 0.01 mM, 1 mM, or 1 mM while the final HF concentration is 1% (wt/vol).

! CRITICAL STEP: The presence of HF is critical to ensure an oxide-free surface of Si for an efficient reduction of metal precursors.

-

24

Dip the p-i-n diode junction from Step 22 into the plating solution and wait for 3 min at room temperature to finish the electroless deposition.

PAUSE POINT

Synthesis of Si materials: PDMS-supported Au-decorated Si meshes. Timing: 2 days in total!

CRITICAL The fabrication process for PDMS-supported Au-decorated Si meshes is divided into two processes that can be executed in parallel; the preparation of distributed Si meshes (Steps 25–33) and porous PDMS membranes (Steps 34–39). The fabrication of distributed Si meshes is performed with a combination of photolithography and etching techniques while the PDMS membrane is prepared using a soft-lithography technique (Figure 5). The assembled flexible device can be laminated onto the mouse brain cortex for in vivo neuromodulation (Steps 106–122).

-

25

Fabrication of Si meshes (Steps 25–33): Prepare a p-i-n Si diode junction SOI wafer as described in Step 19–22. Cut the wafer into small pieces (e.g., 2×2 cm2) using a tungsten carbide scriber.

-

26

Treat the surface of the substrate with mild O2 plasma (100 W for 1 min) and spin-coat the wafer with MCC primer (500 rpm for 5 s followed by 3000 rpm for 30 s) to promote the adhesion between Si and the subsequent photoresists.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

27

Spin coat a LOR-3A layer on the as-prepared diode junction SOI wafer (500 rpm for 5 s followed by 3000 rpm for 30 s). Bake the substrate at 190 oC for 10 min on a hot plate.

-

28

Spin coat a SU-8 2005 photoresist layer on the LOR-3A layer (500 rpm for 5 s followed by 3000 rpm for 30 s). Bake the substrate first at 65 oC for 3 min and then at 95 oC for 3 min.

-

29

Pattern the distributed mesh structure of SU-8 (Supplementary Data File 1) with a standard photolithography process consisting of ultraviolet (UV) light exposure (200 mJ cm−2), post-exposure baking (65 oC for 3 min and then at 95 oC for 3 min), and developing in the SU-8 developer for 1 min. Rinse the substrate in copious amount of DI water and blow dry by N2 guns. The as-patterned SU-8 mesh will serve as an etch mask for the subsequent reactive ion etching (RIE) process of Si.

! CRITICAL STEP: To ensure a good mechanical robustness of the mesh, wider interconnecting bridges are desired. In the particular design, 80-µm wide bridges are adopted to connect all the 500×500 µm2 islands. Additionally, the sharp necks between the bridges and the islands will be the most strained region of the entire device. Curved necks with quarter circle arcs with an 80-µm radius of curvature are introduced to mitigate the strain. Finally, 20-µm diameter holes are evenly distributed within the Si islands to facilitate ion flows for the photostimulation experiment (Figure 5).

-

30

Hard bake the SU-8 mesh pattern under 180 oC for 20 min to improve its stability under the RIE.

-

31

During the RIE, introduce CF4 (45 sccm) and Ar (5 sccm) to etch the unprotected p-i-n Si layers. It typically takes 10 min to completely remove the ~ 2.3 μm of Si under a radiofrequency (RF) power of 100 W and an inductive-coupled plasma (ICP) power of 400 W.

-

32

Lift off the SU-8 protection layer by dissolving the underlying LOR-3A layer using Remover-PG overnight. Rinse the substrate in copious amount of DI water and blow dry using an N2.

-

33

Perform a final wet etching step of the oxide layer with 48% (wt/vol) HF to release the as-patterned Si diode junction.

-

34

Fabrication of porous PDMS membranes (Steps 34–39): Cut a n-type Si wafer into small pieces (e.g., 2×2 cm2) using a tungsten carbide scriber.

-

35