Abstract

Depressive symptoms are common among pregnant women living with HIV, and an unintended pregnancy may heighten vulnerability. HIV-status disclosure is thought to improve psychological well-being, but few quantitative studies have explored the relationships among disclosure, pregnancy intention and depression. Using multivariable linear regression models, we examined the impact of disclosure on depressive symptoms (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; EPDS) during pregnancy and postpartum among women who tested HIV-positive during the pregnancy in South Africa; and explored the role of pregnancy intention in this relationship. Among 350 women (median age: 27 years; 70% reporting that their current pregnancy was unintended), neither disclosure to a male partner nor disclosure to ≥1 family/community member had a consistent effect on depressive symptoms. However, pregnancy intention modified the association between disclosure to a male partner and depression during pregnancy: disclosure was associated with higher depression scores among women who reported that their current pregnancy was unintended but was associated with lower depression scores among women who reported that their pregnancy was intended. During the early postpartum period, disclosure to ≥1 family/community member was associated with higher depression scores. Counselling around disclosure in pregnancy should consider the heightened vulnerability that women face when experiencing an unintended pregnancy.

Keywords: HIV, disclosure, depression, pregnancy intention, South Africa

Introduction

Pregnant women living with HIV experience high rates of depressive symptoms globally (Kapetanovic, Dass-Brailsford, Nora, & Talisman, 2014). In general populations of pregnant women, antenatal depression has well-documented negative effects on maternal health (World Health Organization & United Nations Population Fund, 2009) and child health and development (Stein et al., 2014); in the context of HIV, depression may have additional negative effects on the uptake of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission services (Gourlay, Birdthistle, Mburu, Iorpenda, & Wringe, 2013; O’Hiarlaithe, Grede, de Pee, & Bloem, 2014). In South Africa, women undergo routine HIV testing when entering antenatal care, and a new HIV diagnosis during pregnancy may lead to heightened vulnerability. In this context, women face a ‘triple burden’ of transitioning into pregnancy, accepting their HIV diagnosis, and accepting the urgent need to start lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Stinson & Myer, 2012). This vulnerability may be further heightened by an unintended pregnancy. Unintended pregnancies are common among women living with HIV in South Africa (Adeniyi et al., 2018; Iyun et al., 2018) and may lead to considerable disruption in women’s lives (Crankshaw et al., 2014) as well as antenatal depression (Brittain et al., 2015; Howard et al., 2014; Peltzer, Rodriguez, & Jones, 2016).

Self-disclosure of HIV status to others within an individual’s social network is widely encouraged in counselling services for people living with HIV, and is thought to have beneficial effects on psychological well-being. However, the evidence for this association is mixed (Chaudoir, Fisher, & Simoni, 2011). Among adults living with HIV, cross-sectional studies have reported that disclosure is associated with either higher (Seth et al., 2014; Shacham, Small, Onen, Stamm, & Overton, 2012) or lower (Farley et al., 2010; Vyavaharkar et al., 2011) levels of depression; other studies have found no association (Daskalopoulou et al., 2017; Mello, Segurado, & Malbergier, 2010; Patel et al., 2012). In longitudinal studies, depression appears to be associated with lower levels of disclosure to sexual partners among men who have sex with men (Abler et al., 2015) as well as among women living with HIV (Ojikutu et al., 2016), with higher levels of depression associated with a longer time to first disclosure among women living with HIV in the United States (Liu et al., 2017). It has been suggested that the association between disclosure and lower levels of depression is mediated by social support (Vyavaharkar et al., 2011), with disclosure being beneficial only to the extent to which it alleviates psychological stress or provides a mechanism to obtain social support (Chaudoir et al., 2011). In contrast, negative responses to disclosure may be associated with lower levels of perceived social support and higher levels of psychological distress (Cama, Brener, Slavin, & de Wit, 2017).

Qualitative work among pregnant and postpartum women living with HIV in Uganda has documented an evolution of coming to terms with an HIV diagnosis and developing coping strategies, with disclosing and receiving support described as integral to this process (Medley, Kennedy, Lunyolo, & Sweat, 2009). However, few quantitative studies have examined the role of pregnancy intention in the relationship between disclosure and psychological well-being among pregnant women living with HIV. In the context of an unintended pregnancy and an HIV diagnosis during pregnancy, women must negotiate a dual disclosure: disclosure of the unintended pregnancy as well as disclosure of their HIV status (Crankshaw et al., 2014). Given the well-documented negative effects of antenatal depression among pregnant women living with HIV, and heightened vulnerability due to an unintended pregnancy, studies are needed to examine the relationships among disclosure, pregnancy intention and depression. We thus examined the impact of HIV-status disclosure on depression during pregnancy and postpartum among women who tested HIV-positive during the pregnancy; and explored the role of the intendedness of the current pregnancy in this relationship.

Materials and methods

Study design

These analyses use data from a multi-phase implementation science study, the MCH-ART study, which evaluated strategies for delivering HIV care and treatment services during pregnancy and the postpartum period in Cape Town, South Africa (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01933477). The design and primary results of the study have been previously described (Myer et al., 2016; Myer et al., 2018). Briefly, the study was conducted at one antenatal care clinic in the former township of Gugulethu, where an antenatal HIV prevalence of ~30% has been documented (Myer et al., 2015). The study included a cross-sectional evaluation of all pregnant women living with HIV who were entering antenatal care; an observational cohort following women who initiated ART during the pregnancy through their first postpartum clinic visit; and an intervention study evaluating strategies for delivering HIV care and treatment services to breastfeeding women through 12 months postpartum. ART eligibility was determined based on local guidelines in this setting: until June 2013, eligibility was determined based on CD4 cell count or clinical disease staging; from July 2013 onward, all pregnant women living with HIV were eligible to initiate lifelong ART under the World Health Organization’s Option B+ guidelines (World Health Organization, 2016).

Participants

For the broader MCH-ART study, women who initiated ART during the pregnancy were followed through delivery, and women opting to breastfeed were followed through 12 months postpartum. For the current analyses, we included women who had tested HIV-positive during the pregnancy and who were initiating ART in analyses through 12 months postpartum. Participants were enrolled into the study between March 2013 and April 2014. All women provided written informed consent prior to enrolment, and the study was approved by the University of Cape Town’s Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee and by Columbia University Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board in New York.

Measures

Participants attended study measurement visits that were separate from routine HIV or antenatal/postpartum care. Study measures were administered by trained interviewers in isiXhosa, the predominant local language. Measures were translated from English into isiXhosa and were back-translated prior to the study using standard procedures to ensure accuracy (Preciago & Henry, 1997). Basic sociodemographic characteristics were assessed at enrolment into the study, which coincided with participants’ entry into antenatal care, and included age, educational attainment and relationship status. The intendedness of the current pregnancy was assessed by asking women whether or not they were trying to have a baby when they found out that they were pregnant. A composite poverty score was calculated in order to categorise participants according to relative levels of disadvantage, and was based on current employment, housing type and access to household assets (Brittain et al., 2017). At entry into antenatal care, women underwent phlebotomy for CD4 enumeration via flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter), and gestation was assessed using ultrasound.

HIV-status disclosure was self-reported at all study visits using a tool previously described (Brittain et al., 2018). Briefly, disclosure was assessed by asking women whether they had told their male partner about their HIV status, as well as whether they had told family/community members, including their mother, father, sister, brother, uncle, aunt, male cousin, female cousin, other male family member, other female family member, friend, or spiritual leader. This list of individuals was developed for the purposes of this study, and disclosure to each category was assessed using response options of ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Not Applicable’; we combined the response options ‘No’ and ‘Not applicable’ in analyses.

Self-reported depressive symptoms were assessed at three timepoints (participants’ 2nd antenatal visit and at 6 weeks and 12 months postpartum) using the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). The EPDS was originally developed as a screening tool for possible depressive disorders among postpartum women, but has been validated for use in pregnancy (Murray & Cox, 1990) and in a sample of postpartum women in South Africa (Lawrie, Hofmeyr, de Jager, & Berk, 1998). Based on the original development of the scale, each item was assessed on a frequency scale ranging from 0 to 3, and a total score was obtained by summing individual item responses, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. We used a threshold value of ≥13 as suggestive of elevated depressive symptoms in descriptive analyses, as recommended in the original development of the scale (Cox et al., 1987).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata 14 (StataCorp Inc, College Station, Texas, USA). Baseline sociodemographic characteristics were summarised and were compared across pregnancy intention using Wilcoxon rank sum (Mann-Whitney) tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. For each timepoint at which depressive symptoms were assessed, we used multivariable linear regression models to explore the associations between cumulative reports of disclosure up to that study visit and depressive symptoms, adjusting for potential confounding by sociodemographic characteristics and, at postpartum timepoints, design effect. We explored the impact of the intendedness of the current pregnancy in stratified models and using interaction terms. Throughout, we explored disclosure using two separate constructs: (i) disclosure to a male partner and (ii) disclosure to ≥1 family/community member, based on previous analyses suggesting that these disclosure events form separate dimensions in this sample (Brittain et al., 2018). Continuous depressive symptom scores were used in all analyses, although the proportion of participants with elevated scores on the EPDS was calculated at each timepoint using the suggested threshold value described above. Finally, we repeated our analysis restricted to women who had completed assessments at all three timepoints in order to assess potential changes in results (n=208). This restriction did not change results, thus we present results from the total sample below.

Results

Participant characteristics, disclosure and depressive symptoms

A total of 350 women (median age: 26.9 years) who had tested HIV-positive during the pregnancy, were eligible to initiate ART, and completed assessments at the 2nd antenatal study visit were included in analyses. A total of 258 women (74%) completed assessments at the 6 week postpartum study visit, and 213 (61%) completed assessments at 12 months postpartum. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1, stratified by pregnancy intention. Most participants reported a previous pregnancy, and reported low levels of educational attainment and employment; 70% of women reported that their current pregnancy was unintended. Women who reported an unintended pregnancy were significantly less likely to be married and/or cohabiting with their partner (p<0.001) and had entered antenatal care at a significantly later gestation (p=0.006).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, HIV-status disclosure and depressive symptoms (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; EPDS), by intendedness of the current pregnancy

| Variable | Total sample – n (%) |

Pregnancy intention |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unintended – n (%) |

Intended – n (%) |

|||

| Number of women | 350 | 244 | 106 | |

| Participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at entry into antenatal care | ||||

| Median [IQR] age in years | 26.9 [23.5, 31.5] | 26.7 [23.1, 31.4] | 27.5 [24.3, 31.6] | 0.268 |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Primary/some secondary | 241 (69) | 167 (68) | 74 (70) | 0.799 |

| Completed secondary/any tertiary | 109 (31) | 77 (32) | 32 (30) | |

| Currently employed | 146 (42) | 103 (42) | 43 (41) | 0.774 |

| Poverty level (assets + employment) | ||||

| Most disadvantaged | 123 (35) | 88 (36) | 35 (33) | 0.857 |

| Moderately disadvantaged | 116 (33) | 80 (33) | 36 (34) | |

| Least disadvantaged | 111 (32) | 76 (31) | 35 (33) | |

| Married and/or cohabiting | 130 (37) | 72 (30) | 58 (55) | <0.001 |

| First pregnancy | 95 (27) | 65 (27) | 30 (28) | 0.748 |

| Median [IQR] gestation in weeks | 21 [16, 26] | 22 [17, 28] | 20 [15, 24] | 0.006 |

| Median [IQR] CD4 cell count (n=337) | 352 [247, 504] | 352 [248, 513] | 351 [247, 504] | 0.602 |

| HIV-status disclosure | ||||

| Disclosed to male partner by 2nd antenatal visit | 188 (54) | 120 (49) | 68 (64) | 0.010 |

| Disclosed to male partner by 6 weeks postpartum (n=258) | 150 (58) | 101 (54) | 49 (68) | 0.045 |

| Disclosed to male partner by 12 months postpartum (n=213) | 127 (60) | 85 (57) | 42 (67) | 0.175 |

| Disclosed to ≥1 family/community member by 2nd antenatal visit | 202 (58) | 141 (58) | 61 (58) | 0.967 |

| Disclosed to ≥1 family/community member by 6 weeks postpartum (n=258) | 169 (66) | 119 (64) | 50 (69) | 0.407 |

| Disclosed to ≥1 family/community member by 12 months postpartum (n=213) | 155 (73) | 107 (71) | 48 (76) | 0.467 |

| Depressive symptoms | ||||

| EPDS score ≥13 at 2nd antenatal visit | 41 (12) | 30 (12) | 11 (10) | 0.608 |

| EPDS score ≥13 at 6 weeks postpartum (n=258) | 11 (4) | 8 (4) | 3 (4) | 0.962 |

| EPDS score ≥13 at 12 months postpartum (n=213) | 10 (5) | 7 (5) | 3 (5) | 0.976 |

Reported disclosure to a male partner increased from 54% of participants at the 2nd antenatal study visit to 60% at 12 months postpartum; disclosure to ≥1 family/community member increased from 58% to 73% (Table 1). Few sociodemographic or clinical characteristics were associated with disclosure, but women who were married and/or cohabiting were more likely to report having disclosed to their male partner and less likely to report having disclosed to ≥1 family/community member (both p<0.001) at the 2nd antenatal study visit. Women who reported that their current pregnancy was intended were also more likely to report having disclosed to a male partner by their 2nd antenatal study visit compared to women who reported that their current pregnancy was unintended (p=0.010). The proportion of women scoring above threshold for depressive symptoms decreased from 12% at the 2nd antenatal study visit, to 4% and 5% at the 6 week and 12 month postpartum study visits, respectively; levels of depressive symptoms were similar when restricted to women with complete data across all three timepoints. No differences in depressive symptoms were observed across the intendedness of the current pregnancy.

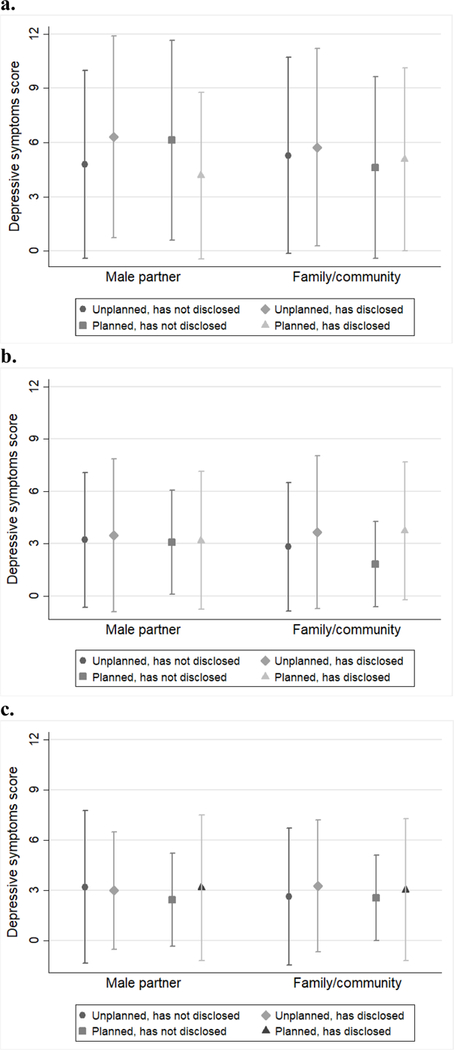

Impact of disclosure on antenatal depressive symptoms

Overall, neither disclosure to a male partner nor disclosure to ≥1 family/community member was associated with depressive symptoms at the 2nd antenatal study visit (Table 2), with results unchanged when stratified by relationship status and by age categories. However, pregnancy intention appeared to modify the association between disclosure to a male partner and depressive symptoms. Among women who reported that their current pregnancy was unintended, disclosure to a male partner was associated with higher depression scores in both unadjusted models [regression coefficient (β): 1.53; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.17, 2.89] and after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics (β: 1.59; 95% CI: 0.21, 2.97). Conversely, disclosure to a male partner was associated with lower depression scores among women who reported that their current pregnancy was intended after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (β: −2.27; 95% CI: −4.48, −0.07). Effect modification by pregnancy intention was clearly observed in a graphical portrayal of mean depressive symptom scores: on average, depressive symptom scores were highest among women who reported that the current pregnancy was unplanned and disclosed to their male partner, and among women who reported that the current pregnancy was planned but did not disclose to their male partner (Figure 1a). Stratification by pregnancy intention did not change the null association between disclosure to ≥1 family/community member and depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Impact of disclosure on depressive symptoms at 2nd antenatal visit, overall and by intendedness of the current pregnancy (n=350)

| Variable | Mean (SD) EPDS score a | Unadjusted β [95% CI] b | P-value | Adjusted β [95% CI] c | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All women | |||||

| Disclosure to a male partner | |||||

| Has not disclosed | 5.1 (5.3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Has disclosed | 5.5 (5.3) | 0.44 [−0.68, 1.56] | 0.443 | 0.51 [−0.65, 1.67] | 0.388 |

| Disclosure to family/community members | |||||

| Disclosed to none | 5.1 (5.3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Disclosed to ≥1 person | 5.5 (5.3) | 0.45 [−0.68, 1.58] | 0.435 | 0.45 [−0.70, 1.60] | 0.443 |

| Women reporting unintended pregnancy at 1st antenatal visit | |||||

| Disclosure to a male partner | |||||

| Has not disclosed | 4.8 (5.2) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Has disclosed | 6.3 (5.6) | 1.53 [0.17, 2.89] | 0.027 | 1.59 [0.21, 2.97] | 0.025 |

| Disclosure to family/community members | |||||

| Disclosed to none | 5.3 (5.4) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Disclosed to ≥1 person | 5.7 (5.5) | 0.44 [−0.95, 1.83] | 0.532 | 0.53 [−0.89, 1.94] | 0.463 |

| Women reporting intended pregnancy at 1st antenatal visit | |||||

| Disclosure to a male partner | |||||

| Has not disclosed | 6.1 (5.5) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Has disclosed | 4.2 (4.6) | −1.97 [−3.96, 0.03] | 0.053 | −2.27 [−4.48, −0.07] | 0.043 |

| Disclosure to family/community members | |||||

| Disclosed to none | 4.6 (5.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Disclosed to ≥1 person | 5.1 (5.1) | 0.47 [−1.50, 2.43] | 0.640 | 0.25 [−1.81, 2.30] | 0.813 |

SD: standard deviation; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

β: regression coefficient

adjusted for age, poverty and relationship status.

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) depressive symptom scores at the (a) 2nd antenatal, (b) 6 week postpartum and (c) 12 month postpartum study visit by disclosure to a male partner and to ≥1 family/community member, stratified by intendedness of the current pregnancy.

Impact of disclosure on postpartum depressive symptoms

At 6 weeks postpartum, no associations were observed between disclosure to a male partner and depressive symptoms in unadjusted models or after adjustment for age, poverty, relationship status and design effect; these null results persisted when stratified by pregnancy intention. However, disclosure to ≥1 family/community member was associated with higher depression scores at this timepoint (β: 1.10; 95% CI: 0.07, 2.12 in unadjusted model; and β: 0.94; 95% CI: −0.11, 1.99 after adjustment for age, poverty, relationship status and design effect); this association was stronger among women who reported that the current pregnancy was intended (β: 1.92; 95% CI: 0.10, 3.74 in unadjusted model; and β: 1.94; 95% CI: −0.03, 3.91 after adjustment for age, poverty, relationship status and design effect; Figure 1b). In the total sample at 12 months postpartum, neither disclosure to a male partner nor disclosure to ≥1 family/community member was associated with depressive symptoms in unadjusted models or after adjustment for age, poverty, relationship status and design effect; these null results persisted when stratified by pregnancy intention (Figure 1c).

Discussion

This research examined the impact of HIV-status disclosure on depression during pregnancy and postpartum among women who had tested HIV-positive during the pregnancy; and explored the role of the intendedness of the current pregnancy in this relationship. The proportion of women with elevated depressive symptoms was high antenatally, but decreased during the postpartum period. Both unintended pregnancy and disclosure were common, and neither disclosure to a male partner nor disclosure to ≥1 family/community member was consistently associated with antenatal or postpartum depressive symptoms in the overall sample. However, the association between disclosure to a male partner and antenatal depressive symptoms was modified by the intendedness of the current pregnancy: disclosure was associated with higher depression scores among women who reported that their current pregnancy was unintended, but was associated with lower depression scores among women who reported that their current pregnancy was intended. During the early postpartum period, disclosure to ≥1 family/community member was associated with higher depression scores, but this association did not persist at 12 months postpartum.

Several key findings warrant further discussion. First, women receiving a new HIV diagnosis in the context of an unintended pregnancy face additional vulnerability. Fears about disclosing are common among women living with HIV, with women fearing abandonment and intimate partner violence after disclosing to a partner, and gossip and discrimination after disclosing to community members (Ashaba et al., 2017). In the context of an unintended pregnancy as well as a new HIV diagnosis, the dual disclosure that women must negotiate has been described as a ‘double disclosure bind’ (Crankshaw et al., 2014). We have previously shown that disclosure to a male partner during pregnancy and postpartum is more common among women reporting an intended pregnancy (Brittain et al., 2018). Here, we have demonstrated that the intendedness of the pregnancy additionally modifies the impact of disclosure to a male partner on depressive symptoms. In the context of an unintended pregnancy, women who disclosed their HIV status to their male partner reported higher levels of depressive symptoms during pregnancy compared to women who did not disclose. This effect did not persist during the postpartum period, and we hypothesise that this may indicate an evolution of coming to terms both with a new HIV diagnosis and with an unintended pregnancy. Further research is needed to explore this possibility, and to explore the causality of our findings.

Second, these results highlight the importance of considering women’s relationships with the person(s) to whom they disclose. Most existing research operationalises disclosure as any versus no disclosure (Dima, Stutterheim, Lyimo, & de Bruin, 2014), or focusses only on disclosure to a partner. Our findings suggest that disclosure to different individuals may have different effects on depression; previous research has similarly shown that the impact of disclosure depends on women’s relationships with the person(s) to whom they have disclosed (Miller et al., 2016). Further, our findings may explain the mixed evidence in the existing literature, where studies have mostly used simplified measures of disclosure as well as cross-sectional analyses. Finally, we observed a reduction in the proportion of women with elevated depressive symptoms in the postpartum compared to antenatal period, similar to findings from Malawi (Harrington et al., 2018). We included only women who had been diagnosed HIV-positive during the pregnancy in analyses, and thus hypothesise that a new HIV diagnosis may have led to a high prevalence of antenatal depressive symptoms, but that this prevalence decreased during the postpartum period as women came to terms with their diagnosis. Further research is needed to explore the evolution of depressive symptoms over time in this population.

A strength of the present study is the inclusion of longitudinal data as well as the use of disclosure measures that allowed for the consideration of women’s relationships to the person(s) to whom they had disclosed. In addition, we included a large sample of women who tested HIV-positive at a primary care facility, and our findings are likely to be generalizable to other communities of pregnant and postpartum women in the region. A limitation of this analysis is the use of self-report to measure disclosure. In addition, depressive symptoms were assessed using self-report and not a diagnostic interview. Self-reported disclosure may be subject to recall and social desirability bias, although this is common to all disclosure research, and the EPDS has been validated in pregnancy and in postpartum women in South Africa. A further limitation of this analysis is that we did not assess responses to disclosure, which may be critical determinants of subsequent psychological well-being or distress. Finally, we did not examine associations between disclosure and other psychosocial variables, and our findings should be extrapolated to other markers of psychological well-being with caution.

Despite some limitations, these results are novel and the findings notable. There is limited quantitative evidence for a beneficial effect of disclosure on depression among pregnant women living with HIV, and a dearth of research examining the role of the intendedness of the pregnancy in this relationship. Our findings suggest that disclosure does not have a consistent effect on depression; rather, disclosure to a male partner appears to have an adverse effect during the antenatal period among women experiencing an unintended pregnancy, and a beneficial effect among women experiencing an intended pregnancy. Although these findings did not persist during the postpartum period, we argue that they have important implications for counselling services during pregnancy, given the well-documented adverse effects of antenatal depression. Without consideration of pregnancy intention, as well as women’s relationships to the person(s) to whom they disclose, counselling services may be encouraging women to disclose when this may have negative repercussions. Our findings suggest that counselling messaging around HIV-status disclosure in pregnancy should consider the heightened vulnerability that women face when experiencing an unintended pregnancy, and that disclosure may not be beneficial for all women.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in this study, as well as the study staff for their support of this research. This research was supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), grant number 1R01HD074558. Additional funding comes from the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. Ms. Brittain is supported by the South African Medical Research Council under the National Health Scholars Programme. Drs. Mellins and Remien are supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies (P30-MH45320).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abler L, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Hansen NB, Wilson PA, & Kochman A (2015). Depression and HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(10), 550–558. 10.1089/apc.2015.0122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeniyi OV, Ajayi AI, Moyaki MG, Goon DT, Avramovic G, & Lambert J (2018). High rate of unplanned pregnancy in the context of integrated family planning and HIV care services in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 140 10.1186/s12913-018-2942-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashaba S, Kaida A, Coleman JN, Burns BF, Dunkley E, O’Neil K, … Psaros C (2017). Psychosocial challenges facing women living with HIV during the perinatal period in rural Uganda. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0176256 10.1371/journal.pone.0176256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K, Mellins CA, Phillips T, Zerbe A, Abrams EJ, Myer L, & Remien RH (2017). Social support, stigma and antenatal depression among HIV-infected pregnant women in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 274–282. 10.1007/s10461-016-1389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K, Mellins CA, Remien RH, Phillips T, Zerbe A, Abrams EJ, & Myer L (2018). Patterns and predictors of HIV-status disclosure among pregnant women in South Africa: dimensions of disclosure and influence of social and economic circumstances. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 3933–3944. 10.1007/s10461-018-2263-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K, Myer L, Koen N, Koopowitz S, Donald KA, Barnett W, … Stein DJ (2015). Risk factors for antenatal depression and associations with infant birth outcomes: results from a South African birth cohort study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 29(6), 505–514. 10.1111/ppe.12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cama E, Brener L, Slavin S, & de Wit J (2017). The relationship between negative responses to HIV status disclosure and psychosocial outcomes among people living with HIV. Journal of Health Psychology, 10.1177/1359105317722404 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD, & Simoni JM (2011). Understanding HIV disclosure: a review and application of the Disclosure Processes Model. Social Science & Medicine, 72, 1618–1629. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, & Sagovsky R (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crankshaw TL, Voce A, King RL, Giddy J, Sheon NM, & Butler LM (2014). Double disclosure bind: complexities of communicating an HIV diagnosis in the context of unintended pregnancy in Durban, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 18(Suppl 1), S53–S59. 10.1007/s10461-013-0521-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalopoulou M, Lampe FC, Sherr L, Phillips AN, Johnson MA, Gilson R, … ASTRA Study Group. (2017). Non-disclosure of HIV status and associations with psychological factors, ART non-adherence, and viral load non-suppression among people living with HIV in the UK. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 184–195. 10.1007/s10461-016-1541-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dima AL, Stutterheim SE, Lyimo R, & de Bruin M (2014). Advancing methodology in the study of HIV status disclosure: the importance of considering disclosure target and intent. Social Science & Medicine, 108, 166–174. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley J, Miller E, Zamani A, Tepper V, Morris C, Oyegunle M, … Blattner W(2010). Screening for hazardous alcohol use and depressive symptomatology among HIV-infected patients in Nigeria: prevalence, predictors, and association with adherence. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care, 9(4), 218–226. 10.1177/1545109710371133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mburu G, Iorpenda K, & Wringe A (2013). Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16, 18588 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington BJ, Hosseinipour MC, Maliwichi M, Phulusa J, Jumbe A, Wallie S, … S4 Study team. (2018). Prevalence and incidence of probable perinatal depression among women enrolled in Option B+ antenatal care in Malawi. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 115–122. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis C-L, Rochat T, Stein A, & Milgrom J (2014).Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1775–1788. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyun V, Brittain K, Phillips TK, le Roux S, McIntyre JA, Zerbe A, … Myer L(2018). Prevalence and determinants of unplanned pregnancy in HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8, e019979 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Dass-Brailsford P, Nora D, & Talisman N (2014). Mental health of HIV-seropositive women during pregnancy and postpartum period: a comprehensive literature review. AIDS and Behavior, 18(6), 1152–1173. 10.1007/s10461-014-0728-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie TA, Hofmeyr GJ, de Jager M, & Berk M (1998). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale on a cohort of South African women. South African Medical Journal, 88(10), 1340–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Goparaju L, Barnett A, Wang C, Poppen P, Young M, & Zea MC (2017). Change in patterns of HIV status disclosure in the HAART era and association of HIV status disclosure with depression level among women. AIDS Care, 29(9), 1112–1118. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1307916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley AM, Kennedy CE, Lunyolo S, & Sweat MD (2009). Disclosure outcomes, coping strategies, and life changes among women living with HIV in Uganda. Qualitative Health Research, 19(12), 1744–1754. 10.1177/1049732309353417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello VA, Segurado AA, & Malbergier A (2010). Depression in women living with HIV: clinical and psychosocial correlates. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13, 193–199. 10.1007/s00737-009-0094-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ES, Yee LM, Dorman RM, McGregor DV, Sutton SH, Garcia PM, & Wisner KL (2016). Is maternal disclosure of HIV serostatus associated with a reduced risk of postpartum depression? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 215, 521. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D, & Cox JL (1990). Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression scale (EDDS). Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 8(2), 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Phillips TK, Hsiao N-Y, Zerbe A, Petro G, Bekker L-G, … Abrams EJ (2015). Plasma viraemia in HIV-positive pregnant women entering antenatal care in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18, 20045 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Phillips TK, Zerbe A, Ronan A, Hsiao N-Y, Mellins CA, … Abrams EJ (2016). Optimizing antiretroviral therapy (ART) for maternal and child health (MCH): rationale and design of the MCH-ART study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72, S189–196. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Phillips TK, Zerbe A, Brittain K, Lesosky M, Hsiao N-Y, … Abrams EJ(2018). Integration of postpartum healthcare services for HIV-infected women and their infants in South Africa: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 15(3), e1002547 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hiarlaithe M, Grede N, de Pee S, & Bloem M (2014). Economic and social factors are some of the most common barriers preventing women from accessing maternal and newborn child health (MNCH) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services: a literature review. AIDS and Behavior, 18, S516–S530. 10.1007/s10461-014-0756-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojikutu BO, Pathak S, Srithanaviboonchai K, Limbada M, Friedman R, Li S, … HIV Prevention Trials Network 063 Team. (2016). Community cultural norms, stigma and disclosure to sexual partners among women living with HIV in Thailand, Brazil and Zambia (HPTN 063). PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0153600 10.1371/journal.pone.0153600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R, Ratner J, Gore-Felton C, Kadzirange G, Woelk G, & Katzenstein D (2012).HIV disclosure patterns, predictors, and psychosocial correlates among HIV positive women in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care, 24(3), 358–368. 10.1080/09540121.2011.608786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Rodriguez VJ, & Jones D (2016). Prevalence of prenatal depression and associated factors among HIV-positive women in primary care in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 13(1), 60–67. 10.1080/17290376.2016.1189847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preciago J, & Henry M (1997). Linguistic barriers in health education and services. In Garcia JG & Zea MC (Eds.), Psychological interventions and research with Latino populations Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Kidder D, Pals S, Parent J, Mbatia R, Chesang K, … Bachanas P (2014). Psychosocial functioning and depressive symptoms among HIV-positive persons receiving care and treatment in Kenya, Namibia, and Tanzania. Prevention Science, 15(3), 318–328. 10.1007/s11121-013-0420-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham E, Small E, Onen N, Stamm K, & Overton ET (2012). Serostatus disclosure among adults with HIV in the era of HIV therapy. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 26(1), 29–35. 10.1089/apc.2011.0183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, … Pariante CM (2014). Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1800–1819. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson K, & Myer L (2012). Barriers to initiating antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy: a qualitative study of women attending services in Cape Town, South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research, 11(1), 65–73. 10.2989/16085906.2012.671263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Corwin S, Tavakoli A, Saunders R, & Annang L(2011). HIV-disclosure, social support, and depression among HIV-infected African American women living in the rural Southeastern United States. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23(1), 78–90. 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016). Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection Geneva: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, & United Nations Population Fund. (2009). Mental health aspects of women’s reproductive health: a global review of the literature Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]