Abstract

Objective:

HIV stigma undermines health and well-being of people living with HIV (PLWH). Conceptual work on stigma mechanisms suggests that experiences of stigma or discrimination increase internalised stigma. However, not all PLWH may internalise the HIV discrimination they experience. We aimed to investigate the role of stress associated with events of HIV-related discrimination on internalised HIV stigma, as well as the downstream effects on depressive symptoms and alcohol use severity.

Design:

199 participants were recruited from an HIV clinic in the southeastern United States.

Main Study Measures:

HIV-related discrimination was assessed using items adapted from measures of enacted HIV stigma and discrimination. Participants rated perceived stress associated with each discrimination item. Internalised HIV stigma was assessed using the internalised stigma subscale of the HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Index. Alcohol use severity was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Results:

In serial mediation models, HIV-related discrimination was indirectly associated with both depressive symptoms and alcohol use severity through its associations with stress and internalised HIV stigma.

Conclusions:

Understanding the mechanisms through which PLWH internalise HIV stigma and lead to poor health outcomes can yield clinical foci for intervention.

Keywords: HIV, discrimination, internalised stigma, stress, depression, alcohol use

Introduction

Stigma functions as a chronic stressor in the lives of those who are stigmatised, undermining health and driving health inequalities (Phelan, Link, & Tehranifar, 2010). HIV stigma – defined as the social devaluation and discrediting of people living with HIV (PLWH) – is a significant barrier to improving the health and wellbeing of PLWH (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013; Link and Phelan, 2001; Mahajan et al., 2008). Consequences of HIV stigma and discrimination include higher levels of depression (Chaudoir et al., 2012; C. Logie and Gadalla, 2009; Vanable, Carey, Blair, & Littlewood, 2006), and problematic alcohol use (Rendina, Millar, & Parsons, 2018; Wardell, Shuper, Rourke, & Hendershot, 2018) that can negatively impact health outcomes and quality of life among PLWH.

In their synthesis of the HIV stigma measurement literature, Earnshaw, Chaudoir, and colleagues clarified that PLWH experience HIV-related stigma through different stigma mechanisms that differentially impact health-related outcomes(Earnshaw and Chaudoir, 2009; Earnshaw, Smith, Chaudoir, Amico, & Copenhaver, 2013). Such mechanisms include internalised stigma, the extent to which PLWH apply negative beliefs and feelings (e.g., shame, disgust) about HIV to themselves, and enacted stigma that encompasses discrimination, prejudice, and stereotypes that are experienced by PLWH. This model for understanding the different effects of HIV stigma mechanisms moved researchers toward building an understanding of who is most affected by HIV stigma, and what the outcomes of HIV stigma mechanisms are at the individual level. Turan and colleagues moved this line of research forward by investigating the ways different stigma mechanisms interact with one another to affect health outcomes (Turan et al., 2017). Specifically, they found that perceived community stigma affects psychosocial outcomes and antiretroviral treatment adherence through its effects first on internalised stigma. They also found that daily experiences of discrimination increased subsequent ratings of internalised HIV stigma within-persons using an experience sampling method (Fazeli et al., 2017). This work provided a useful framework for linking different manifestations of HIV-related stigma.

Discrimination is widely conceptualised as a stressor in the areas of racial and sexual minority discrimination (M.Berger and Sarnyai, 2015; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009), though not fully applied to HIV research. HIV-related discrimination has increased as a focus in quantitative research. Yet, the available tools for measuring HIV-related discrimination capture frequency of experiences rather than the impact or stress related to experiences of HIV-related discrimination. Of the available tools for measuring HIV-related discrimination among PLWH, response options range from yes or no responses whether discrimination occurred over a discrete time period (Bogart, Landrine, Galvan, Wagner, & Klein, 2013), frequency measures from (very) often to not at all/never (Earnshaw, et al., 2013; Holzemer et al., 2007; Sowell et al., 1997), or 4-point Likert responses (B. E. Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001; Bunn, Solomon, Miller, & Forehand, 2007; Fife and Wright, 2000). Some items measured in these scales may occur infrequently (e.g., “People have physically backed away from me when they learn I have HIV.” or “I have been physically assaulted or beaten up.”) but can be very impactful, stressful, or traumatic. However, in quantitative studies these experiences are often given the same weight as other events measured, or perhaps less weight since they would be rated as occurring less frequently (rarely/not often) in many cases. HIV-related discrimination measures do not appear to capture the psychological impact specific to discrimination experiences. Thus, from a stress and coping framework perspective (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), the appraisal of stress associated with HIV-related discrimination is not well understood.

Among the stigma mechanisms, internalised stigma is the most widely measured and may be the most detrimental to mental health (Earnshaw and Chaudoir, 2009; Earnshaw, et al., 2013). Internalised stigma is associated with greater psychological distress (Boone, Cook, & Wilson, 2016), negative emotional states (Earnshaw, et al., 2013), and depression (Earnshaw and Chaudoir, 2009; Mak, Poon, Pun, & Cheung, 2007; Simbayi et al., 2007). HIV-related discrimination appears to be a risk factor for internalizing HIV stigma (Fazeli, et al., 2017). Furthermore, individuals with internalised stigma may be more sensitive to experiences of discrimination (Chesney and Smith, 1999), and they may have fewer interpersonal resources to cope with the stress of discrimination (Helms et al., 2017). A feedback loop can occur whereby people with internalised stigma are more likely to perceive discrimination and ineffectively cope with those experiences, which then increases internalised stigma (Wardell, et al., 2018). However, not all PLWH are impacted by discrimination in the same way and may be more resilient to internalizing HIV stigma. Some researchers have examined potential protective factors for the harmful effects of stigma and discrimination, but it may also be worthwhile to examine whether appraisals of discrimination relate to internalised HIV stigma and thereby poorer mental health or substance abuse.

In the present study we aim to contribute to the literature on the effects of HIV-related discrimination by comprehensively assessing recent experiences of HIV-related discrimination, and the perceived impact of those experiences. Building upon prior stigma mechanism models (Earnshaw and Chaudoir, 2009; Earnshaw, et al., 2013; Fazeli, et al., 2017; Turan, et al., 2017), we will also examine the relationships between HIV-related discrimination, stress associated with discrimination, internalised HIV stigma, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use severity in a sample of PLWH residing in a low-resource area in the southeast United States.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited from a Ryan White (a federal program supporting HIV-related health services for uninsured and underinsured) funded clinic located in central Georgia between February and May 2016. To be included in the study, participants had to be 1) 18 years or older, 2) able to understand all study procedures and provide informed consent, 3) HIV-positive, and 4) a clinic patient attending an initial or update appointment. Patients were approached by a research staff member in the clinic waiting area and informed about the opportunity to participate in the study. To reduce any pressure on patients to participate in the clinic survey, no clinic staff members were involved in recruiting participants. If a patient expressed interest, they were provided an e-tablet with headphones that administered the consent form via audio-computer assisted self-interview (ACASI). After reading and/or listening to the consent form participants were invited to ask any questions and then signed a consent form if they agreed to the study procedures. A total of 257 people were approached, 58 individuals refused to participate, and 199 patients agreed to complete study procedures (77%).

Following consent, participants were again provided with an e-tablet with headphones and completed their ACASI survey that was de-identified with a participant identification number. The survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Participants were each compensated for their time with a $15 gift card. The Institutional Review Boards at the author’s institution and the clinic-associated institution approved all study procedures. In addition, a Certificate of Confidentiality was sought to protect participants’ information.

Measures

Socio-demographic Information.

Participants were asked their age, year of HIV diagnosis, self-identified gender, race, sexual orientation, and employment status.

Experiences of HIV-related Discrimination.

HIV-related discrimination was assessed using 20 questions adapted from multiple enacted HIV stigma and discrimination measures. Items were selected from the enacted stigma subscale of the HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale (Earnshaw, et al., 2013), the HIV Stigma Scale (Berger, et al., 2001; Bunn, et al., 2007), and the Multiple Discrimination Scale – HIV version (Bogart, et al., 2013). Participants were asked about the frequency with which they experienced any of the items in the past year due to their HIV-positive status on a scale: 5: almost everyday, 4: at least once a week, 3: a few times a month, 2: a few times this year, 1: about once this year, 0: never. Responses across the 20 items were averaged to create a composite score, with higher scores indicating greater frequency of HIV-related discrimination. Reliability of items was very good in this sample, Cronbach’s α = .93.

Impact of HIV-related Discrimination.

For every item on the enacted HIV stigma checklist that participants endorsed in the past year, they rated the negative impact (stress) they associated with that event. This involved asking one item using a numeric rating scale: “Please rate the level of negative impact this event had on you on a scale from 0: no negative impact at all, to 10: the most severely negative event you can imagine. This stress item is adapted from the UCLA Life Event Stress Interview (Hammen et al., 1987), which is an interview schedule designed to assess chronic and acute life events/stressors. A composite stress score was calculated for each participant by averaging their stress scores across the 20 enacted stigma items.

Internalised HIV Stigma.

The HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale (Earnshaw, et al., 2013), internalised stigma subscale (6 items) was used to assess internalised HIV stigma. Participants responded to items assessing their negative feelings about living with HIV (e.g., I feel ashamed about having HIV) on a Likert scale. Higher scores indicate greater internalised stigma (greater agreement with negative statements). In accordance with scoring procedures carried out by the scale authors, responses across the 6 items were averaged to create a composite score. Internal consistency of items in the subscale was very good in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Depressive Symptoms.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale (CES-D; (Radloff, 1977) includes 20 items assessing cognitive, affective, and vegetative symptoms of depression experienced during the past week on a scale from 0 = rarely or none of the time (0 days) to 3 = most or all of the time (5–7 days). Responses across items were summed to yield a total score of depressive symptoms, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. For reference, Radloff suggested a clinical cutoff of 16 to indicate possible depression, or a stricter cutoff of 23 to indicate probable depression. We also computed a separate cognitive/affective symptom score that excluded somatic symptoms (restless sleep, poor appetite, lack of energy, poor concentration, fatigue) for a sensitivity analysis (Ickovics, Hamburger, Vlahov, & et al., 2001; Kalichman, Rompa, & Cage, 2000). Reliability of the CES-D was good in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .89; cognitive/affective items Cronbach’s α = .87).

Alcohol Use Severity.

Alcohol use and symptoms of alcohol dependence were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De la Fuente, & Grant, 1993; Schmidt, Barry, & Fleming, 1995) The AUDIT, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), includes 10 items used to assess alcohol use and problematic behaviors resultant of alcohol use. A cutoff score of 8 or above is suggested to identify individuals who have problematic patterns of alcohol use. This scale also showed good internal consistency in the present sample, Cronbach’s α = .85.

Data Analysis

Prior to analysis, all data was cleaned and checked for technical or computational errors. All analyses were done in SPSS version 23. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were carried out to assess the distribution of study variables and to describe the sample.

Multivariate analyses were carried out using path analysis via the regression-based Process tool (Hayes, 2013). Covariates in all models tested included age, gender (dichotomised as 0: male, 1: female), race (dichotomised as 0: white, 1: black and other people of color), sexual orientation (dichotomised as 0: heterosexual, 1: gay or bisexual), and employment status (dichotomised as 0: not currently working, 1: working). Missing data was minimal (<1%) and handled using listwise deletion. Bootstrapping was used to test for effects without assuming normality in the sampling distribution (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Serial mediation assumes multiple mediators are related, and specifies a chain in which a predictor affects the outcome through its effects first on a mediator, which then affects another mediator (Hayes, 2013). Thus, multiple indirect effects are estimated to yield an overall indirect effect of the multiple mediator model. We tested two serial mediation models examining pathways from HIV-related discrimination, to stress related to discrimination, to internalised HIV stigma on two separate outcomes: CES-D depression symptoms, and AUDIT total score. There was no evidence of multicollinearity between the variables included in the serial mediation models indicated with tolerance values greater than 0.2 and variance inflation factor (VIF) values less than 5 (O’brien, 2007). In mediation models, an indirect effect was judged as significant when the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero. Results are reported as unstandardised beta coefficients to facilitate interpretation of findings based on the measures used in this study.

Results

A description of the sample’s (N=199) demographic information can be found in Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 77 (M: 45.7, SD: 12.0), and years since HIV diagnosis was between 0 and 36 years (M: 13.5, SD: 8.7). The majority of the sample identified their gender as male (62%), and their race as African American/black or other people of color (87%), and 56% identified their sexual orientation as heterosexual. Approximately 23% were working full or part time.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of socio-demographic characteristics and correlations of key study variables (N=199).

| Characteristic | n (%) or M ± SD, range |

Correlation Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc | Stress | Int. Stigma |

CES-D | AUDIT | ||

| Age (M ± SD, range) | 45.7 ± 12.0, 18–77 | −.03 | −.08 | −.21* | −.06 | −.06 |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 13.5 ± 8.7, 0–36 | −.01 | −.03 | −.21* | −.09 | −.09 |

| Gender | .01 | −.04 | .07 | .14 | −.09 | |

| Male† | 123 (62%) | |||||

| Female | 74 (37%) | |||||

| Transgender | 9 (5%) | |||||

| Race | −.02 | .00 | .07 | .07 | .10 | |

| White, non-Hispanic† | 25 (13%) | |||||

| African American/black and other people of color |

167 (87%) | |||||

| Sexual Orientation | −.16* | −.02 | −.11 | −.04 | .03 | |

| Heterosexual† | 112 (56%) | |||||

| Gay or Bisexual | 81 (41%) | |||||

| Employment | −.15* | −.16* | −.02 | −.23* | −.05 | |

| Not currently working† | 153 (77%) | |||||

| Working full or part time | 45 (23%) | |||||

| Study Variable | M ± SD, range | |||||

| HIV-related Discrimination | 0.37 ± 0.77, 0–5 | --- | .65** | .38** | .36** | .13 |

| Stress related to Discrimination | 2.14 ± 3.09, 0–10 | --- | .40** | .41** | .18* | |

| Internalised HIV Stigma | 2.42 ± 1.17, 1–5 | --- | .43** | .21* | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (CES-D total score) | 15.58 ± 11.53, 0–52 | --- | .20* | |||

| Alcohol Use Severity (AUDIT total score) | 3.63 ± 5.45, 0–33 | --- | ||||

Note: Disc= HIV-related Discrimination; Stress= Stress related to Discrimination; Int. Stigma= Internalised HIV Stigma; CES-D= Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; AUDIT= Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test.

Indicates reference category (0) for dichotomous variables.

p<.05;

p<.001

Participants reported a mean CES-D depression score of 15.58 (SD: 11.53, Range: 0–52), with 79 participants meeting or exceeding the cutoff of 16 (40%) for possible depression, and 48 meeting or exceeding the cutoff for probable depression (24%). Participants reported a mean AUDIT score of 3.63 (SD: 5.45, Range: 0–33), with 34 (17%) participants meeting or exceeding the suggested cutoff for problematic drinking behaviors. The prevalence of depression appeared consistent with other estimates of depression in HIV populations (Bengtson et al., 2018; Bing et al., 2001), and alcohol use was within the range of estimates of problematic drinking in PLWH (Chander et al., 2008; Crane et al., 2017).

In bivariate analyses of the associations between demographic variables and continuous study variables, heterosexual-identified individuals endorsed more HIV-related discrimination in the past year. Internalised stigma was associated with younger age, and less time living with HIV. Not working was associated with endorsement of HIV-related discrimination, more stress associated with discrimination, as well as greater depressive symptoms.

Stigma Endorsement

A description of HIV-related discrimination items are presented in Table 2 with item endorsement, average stress reported across items, and average frequency of items. A total of 96 (48%) participants endorsed at least one HIV-related discrimination event in the past year. Differences between groups of participants that endorsed discrimination in the past year versus those who did not were compared, and neither group differed significantly on any demographic variable. Those who endorsed an event of HIV-related discrimination in the past year had higher levels of depression (F(1,190)=10.1, p=.002); they had greater alcohol use severity (F(1, 195)=7.1, p=.008), and they had higher internalised HIV stigma (F(1, 195)=13.7, p<.001).

Table 2.

HIV-related discrimination items endorsed in the past year.

| In the past year… | n (%) | Mean Frequency a (SD) |

Mean Stress b (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| People have treated me differently | 61 (31%) | 2.90 (1.76) | 4.24 (2.81) |

| Family members have avoided me | 23 (12%) | 3.87 (2.16) | 5.26 (2.86) |

| Family members have looked down on me | 26 (13%) | 3.73 (2.15) | 5.69 (3.38) |

| Community/social workers have discriminated

against me |

22 (11%) | 2.82 (1.82) | 5.91 (2.76) |

| Healthcare workers have avoided touching me | 17 (9%) | 2.59 (2.03) | 5.00 (4.05) |

| I have lost friends by telling them I have HIV | 29 (15%) | 2.38 (1.76) | 6.07 (3.32) |

| People seem afraid of me | 32 (16%) | 2.75 (2.08) | 5.34 (3.61) |

| People have physically backed away from me | 35 (18%) | 2.97 (2.02) | 5.66 (3.46) |

| People who know I have HIV ignore my good

points |

35 (18%) | 2.97 (2.07) | 5.31 (3.14) |

| People don’t want me around their children | 28 (14%) | 3.00 (2.11) | 5.83 (3.31) |

| I have been treated with hostility or coldness by

strangers |

27 (14%) | 3.00 (2.00) | 7.04 (2.69) |

| I have been ignored, excluded or avoided by

people close to me |

29 (15%) | 2.69 (1.78) | 5.97 (3.03) |

| I have been rejected by a potential sexual or

romantic partner |

45 (23%) | 2.64 (1.87) | 5.36 (3.54) |

| Someone acted as if I could not be trusted | 25 (13%) | 3.40 (2.22) | 6.31 (3.46) |

| I was denied a place to live or lost a place to live | 9 (5%) | 3.22 (1.99) | 6.70 (2.71) |

| I was treated poorly or made to feel inferior

when receiving healthcare |

18 (9%) | 1.72 (1.18) | 6.47 (3.26) |

| I was denied a job or lost a job | 12 (6%) | 2.50 (2.15) | 6.54 (3.76) |

| Someone insulted or made fun of me | 28 (14%) | 2.11 (1.42) | 5.66 (3.44) |

| My personal property was damaged or stolen | 3 (2%) | 1.33 (0.58) | 5.75 (2.50) |

| I was physically assaulted or beaten | 5 (3%) | 1.20 (0.45) | 7.20 (1.92) |

Note: Frequency and stress means computed only for participants who endorsed each event.

Frequency measure range: 1: once this year to 6: almost everyday.

Stress Measure range 0: no negative impact to 10: most severely negative impact.

On average, participants reported experiencing between two and three different types of HIV-related discrimination events (range: 0–20) in the past year. They endorsed being treated differently by people most (31%), followed by being rejected by a potential sexual or romantic partner (23%). Events with the least frequency of endorsement were having one’s personal property stolen or damaged (2%), and being physically assaulted or beaten (3%). On average, events occurred more than once per year among those who endorsed discrimination, and stress associated with each event was in the moderate range on average.

Mediation Analyses

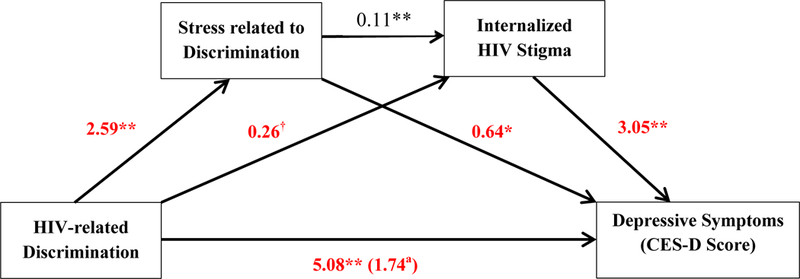

The serial mediation path model with depressive symptoms as the outcome is shown in Figure 1, and results are described in Table 3. The total effect of HIV-related discrimination on depressive symptoms was significant (b (se) = 5.08 (1.00), p<.001, 95% CI [3.10, 7.06]). In the serial mediation model, HIV-related discrimination was significantly associated with stress (b (se) = 2.59 (0.23), p<.001, 95% CI [2.13, 3.06]), and marginally associated with internalised HIV stigma (b (se) = 0.26 (0.13), p=.05, 95% CI [0.00, 0.53]). Stress was significantly associated with internalised HIV stigma (b (se) = 0.11 (0.03), p<.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.18]) and depressive symptoms (b (se) = 0.64 (0.31), p=.04, 95% CI [0.03, 1.25]). Internalised HIV stigma was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (b (se) = 3.05 (0.69), p<.001, 95% CI [1.68, 4.41]). The direct effect of HIV-related discrimination was no longer significant when the mediators were included in the model (b=1.74, p=0.16). The indirect effect of the serial mediation model was significant (b (se) = 0.87 (.37), 95% CI [.31, 1.80]), suggesting that frequency of experiences of HIV-related discrimination relate to greater perceived stress associated with HIV-related discrimination events, which in turn increases internalised HIV stigma and results in greater symptoms of depression. The model results were similar when the cognitive/affective item score of the CES-D were entered as the outcome variable (indirect effect: b (se) = 0.56 (.23), 95% CI [.21, 1.13]).

Figure 1.

Serial mediation model depicting pathways between HIV-related discrimination in the past year, stress related to experiences of discrimination, internalised HIV stigma, and depressive symptoms. The following covariates were included: age, years since HIV diagnosis, race, gender, sexual orientation, employment status. Pathways shown are unstandardised beta coefficients.a Denotes when mediators are included in model (direct effect).Statistical significance is denoted as follows: †p<.10; *p<.05; **p<.001

Table 3.

Results from serial mediation models on the associations between HIV-related discrimination and depressive symptoms and alcohol use, mediated by stress related to discrimination and internalised HIV stigma.

| Outcomes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Stress Related to Discrimination | Internalised HIV Stigma | Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

| Variables | Coefficient (se) |

p | 95% CI | Coefficient (se) |

p | 95% CI | Coefficient (se) |

p | 95% CI |

| HIV-related discrimination | 2.59 (.23) | <.001 | 2.13, 3.06 | 0.26 (.13) | .05 | .00, .53 | 1.74 (1.23) | .16 | −.68, 4.16 |

| Stress related to discrimination | --- | --- | --- | 0.11 (.03) | <.001 | .05, .18 | 0.64 (.31) | .04 | .03, 1.25 |

| Internalised HIV stigma | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3.05 (.69) | <.001 | 1.68, 4.41 |

| Indirect Effect | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.87 (.37) | --- | .31, 1.80 |

| Constant | 1.46 (1.09) | .18 | −.70, 3.62 | 2.91 (.48) | <.001 | 1.96, 3.85 | 5.65 (4.81) | .24 | −3.84, 15.15 |

| Model 2 | Stress Related to Discrimination | Internalised HIV Stigma | Alcohol Use Severity | ||||||

| Coefficient (se) |

p | 95% CI | Coefficient (se) |

p | 95% CI | Coefficient (se) |

p | 95% CI | |

| HIV-related discrimination | 2.62 (0.23) | <.001 | 2.16, 3.07 | 0.26 (.13) | .05 | −.00, .52 | 0.16 (.67) | .82 | −1.17, 1.48 |

| Stress related to discrimination | --- | --- | --- | 0.11 (.03) | .001 | .04, .17 | 0.18 (.17) | .28 | −.15, .51 |

| Internalised HIV stigma | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.79 (.37) | .04 | .05, 1.52 |

| Indirect Effect | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.22 (.14) | --- | .02, .59 |

| Constant | 1.40 (1.07) | .19 | −.72, 3.52 | 2.86 (.47) | <.001 | 1.92, 3.79 | −1.07 (2.60) | .68 | −6.20, 4.06 |

Note: The following covariates were included: age, years since HIV diagnosis, race, gender, sexual orientation, employment status.

Pathways shown are unstandardised beta coefficients.

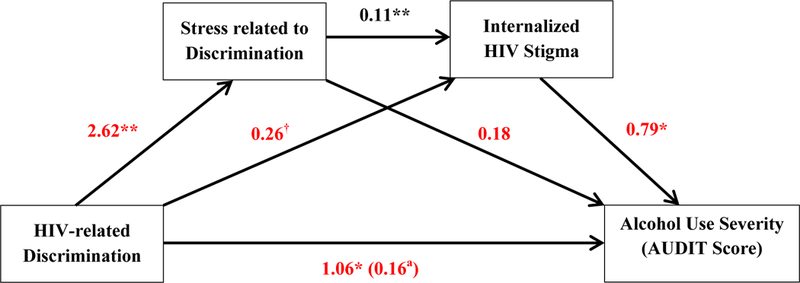

Serial mediation was also supported when alcohol use severity was entered as the outcome. The total effect of HIV-related discrimination on alcohol use severity was significant (b (se) = 1.06 (0.51), p=.04, 95% CI [0.05, 2.07]). In the serial mediation model, HIV-related discrimination was again significantly associated with stress (b (se) = 2.62 (0.23), p<.001, 95% CI [2.16, 3.07]), and marginally associated with internalised HIV stigma (b (se) = 0.26 (0.13), p=.05, 95% CI [−0.00, 0.52]). Stress was significantly associated with internalised HIV stigma (b (se) = 0.11 (0.03), p<.001, 95% CI [0.04, 0.17]), but not associated with alcohol use severity (b= 0.18, p=.28). Internalised HIV stigma was significantly associated with alcohol use severity (b (se) = 0.79 (0.37), p=.04, 95% CI [0.05, 1.52]). The direct effect of HIV-related discrimination was not significant when the mediators were included in the model (b=0.16, p=0.82). The indirect effect of the serial mediation model was significant (b (se) = 0.22 (.14), 95% CI [.02, 0.59]), suggesting that frequency of HIV-related discrimination is related to greater perceived stress associated with discrimination events, which in turn increases internalised HIV stigma and results in greater alcohol use severity.

Discussion

Most research on HIV-related discrimination assesses the frequency with which discrimination occurs that may underestimate the psychological impact of HIV-related discrimination. We expanded an examination of recent events of HIV-related discrimination in terms of frequency and stress appraisal, and used those variables to examine relationships between internalised HIV stigma, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use severity. We found that stress appears to mediate the relationship between experiences of HIV-related discrimination and internalised HIV stigma to ultimately affect depressive symptoms and alcohol use severity.

These findings bring together useful conceptualizations on the relationships between stigma mechanisms (Earnshaw, et al., 2013; Fazeli, et al., 2017; Turan, et al., 2017) and stress appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) to expand upon current measures of HIV-related discrimination and describe how people appraise experiences of discrimination in terms of negative impact or stress. Increased frequency of HIV-related discrimination was associated with higher levels of stress indexed on events of HIV-related discrimination. However, some discrimination events occurred with low frequency but relatively higher stress appraisal (e.g., “I was physically assaulted or beaten.”). Future investigations may need to consider how to address the impact of discrimination when measuring HIV-related discrimination quantitatively. The psychological stress associated with HIV-related discrimination may translate to physiological stress consequences. Research on racial discrimination has linked discrimination to allostatic load (Berger and Sarnyai, 2015), and translating this work to HIV research could provide valuable information linking stress processes specific to HIV-related discrimination and health outcomes.

In addition, the degree to which people perceive discrimination as impactful increases internalised stigma and relates to greater depression and alcohol use. Providing outlets for PLWH to process experiences of discrimination is needed and may not be widely available in many care settings that are low in psychosocial resources. Indeed, PLWH may be resorting to maladaptive forms of coping (i.e., avoidance, substance use) to deal with the stress associated with HIV-related discrimination and internalised HIV stigma, which may explain both outcomes of the present study. Future research should explore whether specific support and coping aimed at dealing with the stress of discrimination experiences has effects on reducing depressive symptoms and curbing alcohol use. Stigma interventions to date do not appear to map intervention effects on health outcomes, which challenges their relevance to public health efforts (Sengupta, Banks, Jonas, Miles, & Smith, 2011). More importantly, systemic and structural changes are needed to reduce stigma at the community level, which would likely have effects on reducing experiences of HIV-related discrimination, stress, and internalised HIV stigma. Increased collaboration is needed across disciplines to develop feasible multilevel interventions that address individual, interpersonal, and structural factors (Cook, Purdie-Vaughns, Meyer, & Busch, 2014).

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. The primary limitation is the cross-sectional retrospective design, which limits interpretation of directionality in relationships between variables or ability to make causal inferences. Paths presented here are suggestions for future prospective and longitudinal investigations. The paths between stigma mechanisms are most likely bidirectional as supported by a recent longitudinal investigation linking stigma and alcohol use (Wardell, et al., 2018), which should also be considered in future research. Additionally, this study only assessed HIV-related discrimination and internalised HIV stigma and cannot account for other forms of stigma and discrimination this sample may experience (e.g., racial discrimination, SES-related stigma, stigma related to sexual minority status, gender-related discrimination, mental health stigma, substance use stigma) and impact their psychological well-being (Bogart, et al., 2013; Logie et al., 2017). Future research could extend this work to explore the differential psychological impact of multiple forms of discrimination that PLWH may experience. Study participants were recruited from an HIV care clinic in a small metropolitan area in central Georgia; thus these findings may not generalise to people in other geographical areas. Findings also may not capture the experience of PLWH who are not engaged or lapsed in care and who may be most vulnerable to stigma and discrimination.

In summary, this study contributes to greater understanding of a stress appraisal process associated with HIV-related discrimination that may make people more likely to internalise HIV stigma and ultimately contribute to disparities in depression and alcohol use among PLWH. Depression and alcohol use are important clinical foci that translate to poorer treatment adherence, disease progression, and greater health burden (Gonzalez, Batchelder, Psaros, & Safren, 2011; Leserman, 2003; Vagenas et al., 2015). From a clinical intervention perspective, HIV stigma, mental health, and substance use are important pieces of the context of health disparities for PLWH that should be attended to in health interventions. One small step could be to assess experiences of discrimination in similar ways that clinicians assess life stressors to provide an opportunity for PLWH to process those experiences. More importantly however, stigma reduction is needed at the structural and community level to interrupt the cycle of experienced HIV-related discrimination that can lead to negative outcomes and deter quality of life.

Figure 2.

Serial mediation model depicting pathways between HIV-related discrimination in the past year, stress related to experiences of discrimination, internalised HIV stigma, and alcohol use severity. The following covariates were included: age, years since HIV diagnosis, race, gender, sexual orientation, employment status. Pathways shown are unstandardised beta coefficients.a Denotes when mediators are included in model (direct effect).Statistical significance is denoted as follows: †p<.10; *p<.05; **p<.001

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by funds from NIH/NIAAA R01-AA023727 (PI: Seth Kalichman, Co-I: Harold Katner, MD) and pre-doctoral fellowship awarded to Kaylee Burnham NIH/NIMH T32 MH074387 (PI: Seth Kalichman). We would also like to thank Christopher Conway Washington, Chauncey Cherry, and Ellen Banas for their assistance with data collection. We appreciate the time and effort of the participants in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Note KBC moved institutions since completion of this study.

References

- Bengtson AM, Pence BW, Powers KA, Weaver MA, Mimiaga MJ, Gaynes BN, . . . Mugavero M (2018). Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms Among a Population of HIV-Infected Men and Women in Routine HIV Care in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2109-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, & Lashley FR (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(6), 518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, & Sarnyai Z (2015). “More than skin deep”: Stress neurobiology and mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Stress, 18(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, . . . Vitiello B (2001). Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus–infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(8), 721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Landrine H, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, & Klein DJ (2013). Perceived discrimination and physical health among HIV-positive Black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 17(4), 1431–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone MR, Cook SH, & Wilson PA (2016). Sexual identity and HIV status influence the relationship between internalized stigma and psychological distress in black gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care, 28(6), 764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller C, & Forehand R (2007). Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: A reexamination of the HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Education & Prevention, 19(3), 198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Josephs J, Fleishman J, Korthuis PT, Gaist P, Hellinger J, . . . Network HR (2008). Alcohol use among HIV‐infected persons in care: Results of a multi‐site survey. HIV Medicine, 9(4), 196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Norton WE, Earnshaw VA, Moneyham L, Mugavero MJ, & Hiers KM (2012). Coping with HIV stigma: Do proactive coping and spiritual peace buffer the effect of stigma on depression? AIDS and Behavior, 16(8), 2382–2391. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0039-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, & Smith AW (1999). Critical delays in HIV testing and care: The potential role of stigma. American BehavioralSscientist, 42(7), 1162–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, & Busch JT (2014). Intervening within and across levels: A multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane HM, McCaul ME, Chander G, Hutton H, Nance RM, Delaney JA, . . . Mugavero MJ (2017). Prevalence and factors associated with hazardous alcohol use among persons living with HIV across the US in the current era of antiretroviral treatment. AIDS and Behavior, 21(7), 1914–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, & Chaudoir SR (2009). From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS and Behavior, 13(6), 1160–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, & Copenhaver MM (2013). HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS and Behavior, 17(5), 1785–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli PL, Turan JM, Budhwani H, Smith W, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, & Turan B (2017). Moment-to-moment within-person associations between acts of discrimination and internalized stigma in people living with HIV: An experience sampling study. Stigma and Health, 2(3), 216–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife BL, & Wright ER (2000). The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(1), 50–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, & Safren SA (2011). Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 58(2). doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Adrian C, Gordon D, Burge D, Jaenicke C, & Hiroto D (1987). Children of depressed mothers: Maternal strain and symptom predictors of dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96(3), p 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helms CB, Turan JM, Atkins G, Kempf M-C, Clay OJ, Raper JL, . . . Turan B (2017). Interpersonal mechanisms contributing to the association between HIV-related internalized stigma and medication adherence. AIDS Behav, 21(1), 238–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Uys LR, Chirwa ML, Greeff M, Makoae LN, Kohi TW, . . . Phetlhu RD (2007). Validation of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument—PLWA (HASI-P). AIDS Care, 19(8), 1002–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, & et al. (2001). Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: Longitudinal analysis from the HIV epidemiology research study. JAMA, 285(11), 1466–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, & Cage M (2000). Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188(10), 662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Coping and adaptation. The handbook of behavioral medicine, pp. 282–325. [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J (2003). HIV disease progression: depression, stress, and possible mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry, 54(3), 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Logie C, & Gadalla T (2009). Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care, 21(6), 742–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie CH, Wang Y, Lacombe-Duncan A, Wagner AC, Kaida A, Conway T, . . . Loutfy MR (2017). HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Preventive Medicine, 107, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Ortiz D, Szekeres G, & Coates TJ (2008). Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS, 22(Suppl 2), S67–S79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak WW, Poon CY, Pun LY, & Cheung SF (2007). Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 65(2), 245–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’brien RM (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, & Tehranifar P (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Suppl 1), S28–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rendina H, Millar BM, & Parsons JT (2018). Situational HIV stigma and stimulant use: A day-level autoregressive cross-lagged path model among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Addictive Behaviors, 83, 109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption‐II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Barry KL, & Fleming MF (1995). Detection of problem drinkers: the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). Southern Medical Journal, 88(1), 52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Banks B, Jonas D, Miles MS, & Smith GC (2011). HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: a systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 15(6), 1075–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, & Mqeketo A (2007). Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 64(9), 1823–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell RL, Lowenstein A, Moneyham L, Demi A, Mizuno Y, & Seals BF (1997). Resources, stigma, and patterns of disclosure in rural women with HIV infection. Public Health Nursing, 14(5), 302–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, & Turan JM (2017). Framing Mechanisms Linking HIV-Related Stigma, Adherence to Treatment, and Health Outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 107(6), 863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagenas P, Azar MM, Copenhaver MM, Springer SA, Molina PE, & Altice FL (2015). The impact of alcohol use and related disorders on the HIV continuum of care: a systematic review. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 12(4), 421–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, & Littlewood RA (2006). Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior, 10(5), pp. 473–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Shuper PA, Rourke SB, & Hendershot CS (2018). Stigma, coping, and alcohol use severity among people living with HIV: A prospective analysis of bidirectional and mediated associations. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, doi: 10.1093/abm/kax050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]