Abstract

Membrane proteins, including G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), present a challenge in studying their structural properties under physiological conditions. Moreover, to better understand the activity of proteins requires examination of single molecule behaviors rather than ensemble averaged behaviors. Force-distance curve-based AFM (FD-AFM) was utilized to directly probe and localize the conformational states of a GPCR within the membrane at nanoscale resolution based on the mechanical properties of the receptor. FD-AFM was applied to rhodopsin, the light receptor and a prototypical GPCR, embedded in native rod outer segment disc membranes from photoreceptor cells of the retina in mice. Both FD-AFM and computational studies on coarsegrained models of rhodopsin revealed that the active state of the receptor has a higher Young’s modulus compared to the inactive state of the receptor. Thus, the inactive and active states of rhodopsin could be differentiated based on the stiffness of the receptor. Differentiating the states based on the Young’s modulus allowed for the mapping of the different states within the membrane. Quantifying the active states present in the membrane containing the constitutively active G90D rhodopsin mutant or apoprotein opsin revealed that most receptors adopt an active state. Traditionally, constitutive activity of GPCRs has been described in terms of two-state models where the receptor can achieve only a single active state. FD-AFM data are inconsistent with a two-state model, but instead require models that incorporate multiple active states.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, G protein-coupled receptor, membrane protein, phototransduction, protein conformation, receptor activation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Rhodopsin is a prototypical G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), one of the largest family of cell surface receptors and targets for drugs 1-2. This GPCR is expressed in photoreceptor cells of the retina and is embedded at high concentrations in the membrane. Activation of rhodopsin by light initiates vision via a G protein-mediated signaling cascade called phototransduction. While rhodopsin must be activated by light to initiate vision, constitutive activity (i.e., receptor activation in the absence of light stimulation) of the receptor can cause a range of inherited retinal diseases with variable phenotypes 3. The molecular basis of these diseases is still unclear.

Although significant advances have been made in our understanding about the mechanism of action of GPCRs, further details about receptor activation are still required to better understand receptor function and the molecular basis of disease. Traditionally, the activity of GPCRs has been assessed using approaches that provide ensemble averaged behaviors. More recently, approaches that can assess the behavior of single molecules have become available and are beginning to reveal the complexity masked by traditional approaches such as those present in GPCR complexes, GPCR signaling dynamics and GPCR conformational states 4-5. GPCRs do not exist in a homogeneous state and signaling is highly localized within nanoscale regions of the membrane 6. Moreover, the requirement of membrane proteins such as GPCRs to be embedded within a lipid bilayer for native function presents a challenge to study their structures and biophysical properties. To overcome this challenge, the receptor is often extracted from the membrane by detergent and/or labeled to facilitate examination by biophysical or structural means. Currently, there is no approach to monitor and localize the conformational states of a GPCR within the membrane at nanoscale resolution. This type of detailed information will be required to advance our understanding about the mechanism of action of GPCRs under both normal and pathological conditions.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a multifunctional nanoscopic tool useful for the study of biological samples 7. Initially, AFM was used primarily as an imaging tool in biology but has now evolved to include many more modalities to probe the structure and function of biological systems. It has been shown to be particularly useful in the study of membrane proteins since the proteins can be examined within the native membrane environment in physiological buffers 8-9. Several applications of AFM have been used to probe the structure and function of GPCRs. For example, topographical images of rod outer segment (ROS) disc membranes have revealed the oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin and the formation of nanodomains 10-13. AFM-based single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) has been applied to rhodopsin, the β2 adrenergic receptor, and protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) to determine kinetic, energetic, and mechanical changes promoted by ligands and mutation 14-18. The free energy landscape has been determined for the binding of a ligand to PAR-1 using force-distance (FD) curve-based AFM (FD-AFM)19.

Since AFM provides nanoscale imaging capabilities in combination with determining various physical and chemical properties of a biological sample 7, it may be suitable for monitoring and localizing conformational states of GPCRs at the nanoscale. Moreover, AFM provides the added benefit that the receptor does not need to be modified and can be investigated within the context of a lipid bilayer or, in some instances, the native membrane obtained from tissues or cells of an organism. The suitability of AFM to monitor and localize different conformational states of a GPCR is dependent on the ability of the AFM probe to distinguish between states based on some sort of difference in physical or chemical property. Previous SMFS studies on constitutively active forms of rhodopsin in native ROS disc membranes revealed a receptor structure that was more rigid along the vertical axis compared to that of inactive rhodopsin when probed from the extracellular surface 14-15. Similar to the active state of rhodopsin, agonist-activated β2 adrenergic receptors also exhibit increased rigidity along the vertical axis when examined by SMFS from the extracellular surface 16. These observations by SMFS indicate that the inactive and active state of GPCRs may be distinguished by the relative stiffness of the structure.

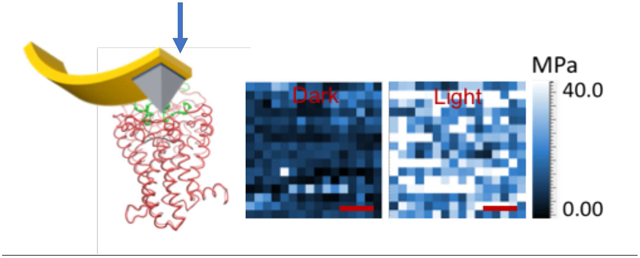

FD-AFM allows for the determination of the mechanical properties of biological samples, such as proteins, cells, and viruses, and the mapping of those properties onto a topographical image 20. Thus, FD-AFM should be able to differentiate between inactive and active GPCRs embedded in a membrane based on the relative stiffness of the structure. To test whether or not an FD-AFM-based approach is suitable to monitor and map the inactive and active states of a GPCR within the membrane, rhodopsin embedded in native ROS disc membranes isolated from the retina of mice was examined. FD-AFM was applied to wild-type rhodopsin and constitutively active forms of the light receptor to map the stiffness, as indicated by the Young’s modulus, of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes and quantify the proportion of receptors exhibiting different Young’s modulus values. Characterization of ROS disc membranes containing different forms of the receptor by FD-AFM demonstrated that the inactive and active states of rhodopsin can be distinguished by their relative stiffness and that the constitutively active state of the receptor may be different from the light-activated state of the wild-type receptor.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

FD-AFM characterization of ROS disc membranes.

AFM was utilized to first image samples and then to map out the stiffness of the sample by computing the Young’s modulus. Force-distance (FD) curves were collected at each pixel of the image and were used to compute the Young’s modulus (Fig. 1). To validate the FD-AFM procedure to determine the Young’s modulus, control studies were conducted on mica and purple membrane containing bacteriorhodopsin, a membrane protein extensively studied by AFM. The Young’s modulus for mica was 531 ± 101 MPa (n = 23) and that of purple membrane containing bacteriorhodopsin was 11 ± 2 MPa (n = 22). Reported Young’s modulus values for mica and bacteriorhodopsin determined by FD-AFM range from 500-8,000 MPa for the former and 10-50 MPa for the latter21-25. Young’s modulus values determined by FD-AFM in the current study are within the range of values reported previously.

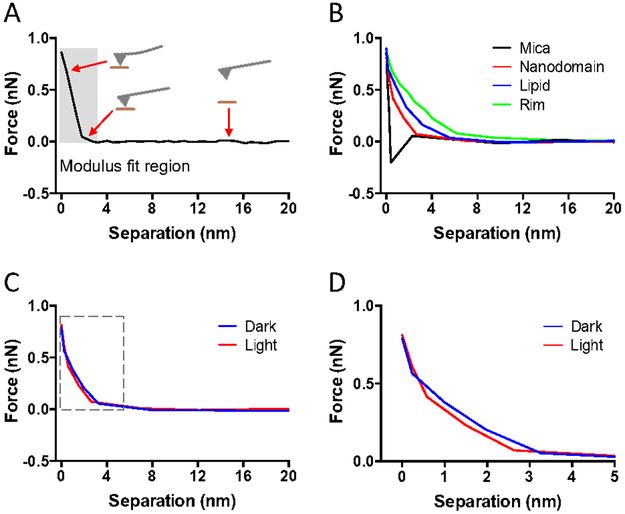

Figure 1.

A sample of FD curves collected in FD-AFM experiments on ROS disc membranes. FD curves shown were adjusted for the cantilever deflection so that the distance represents the tip-sample separation. A. Example of an approach FD curve. The approach curve records the force applied as the AFM probe approaches and then presses into the sample surface. The position of the AFM probe in relation to the sample surface is illustrated at different points of the approach curve. The Young’s modulus is computed by fitting the curve in the region highlighted by the shaded box. B. Sample of approach FD curves obtained from mica (black), rhodopsin nanodomains (red), lipid bilayer (blue), and the rim region of the ROS disc (green). C. Sample of approach FD curves obtained from rhodopsin nanodomains in the dark (blue) or after photobleaching (red). The region of the curve highlighted by the box is presented in panel D. D. Zoomed in view of the FD curve in panel C that includes the region used to fit the data to compute the Young’s modulus.

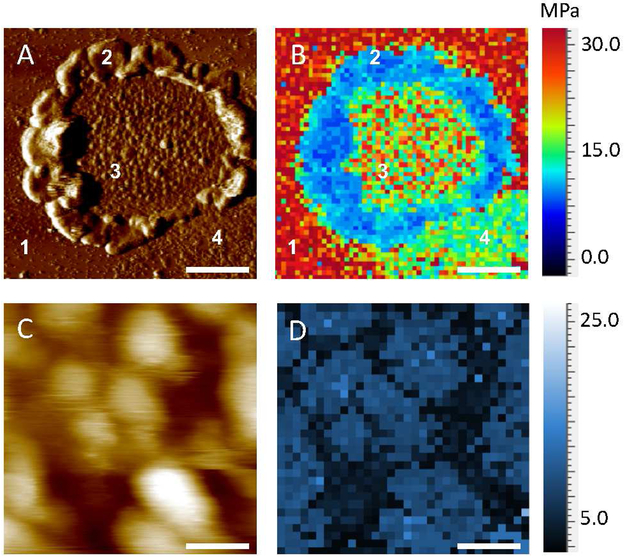

FD-AFM was then applied to ROS disc membranes from the retina of C57B1/6J (B6) mice. AFM imaging revealed the characteristic features of the ROS disc membrane described previously 11-12. ROS disc membranes exhibited a rim region, that is largely absent of rhodopsin, and a lamellar region containing nanodomains of rhodopsin surrounded by a lipid bilayer (Fig. 2A). FD-AFM was applied to compute the Young’s modulus from FD curves (e.g., Fig. 1B) and then to map the Young’s modulus of each of these regions (Fig. 2B). The rim region exhibited the lowest Young’s modulus value at 1 ± 0.1 MPa (n =25). The lipid bilayer exhibited a Young’s modulus of 5 ± 1 MPa (n = 26), which is similar to the Young’s modulus reported for the lipid bilayer in purple membrane 23. Rhodopsin nanodomains exhibited the highest Young’s modulus with a value of 12-19 MPa (Figs. 2B and 2D, Table 1). This Young’s modulus is similar to that of bacteriorhodopsin, which is also a membrane protein with 7 α-helical transmembrane domains.

Figure 2.

FD-AFM of a ROS disc membrane. A. A deflection AFM image of a ROS disc membrane is shown. The mica surface (1), rim region (2), lamellar region with rhodopsin nanodomains (3), and empty lipid bilayer (4) are noted. Scale bar, 500 nm. B. The Young’s modulus was determined in each pixel of the image and mapped onto the image of the ROS disc membrane shown in panel A. The Young’s modulus map consists of 64×64 pixels. C. A zoomed in height AFM image of rhodopsin nanodomains and lipid bilayer present in the lamellar region of the ROS disc. Scale bar, 100 nm. D. Mapping of the Young’s modulus in the lamellar region of the ROS disc membrane shown in panel C. The Young’s modulus map consists of 32×32 pixels.

Table 1.

Young’s modulus of rhodopsin nanodomains in B6, Rpe65−/−, Rho-G90D+/+, and Rho-G90D+/− mice.

| Mice | Young’s modulus (MPa)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| Dark | Light | |

| B6 | 11.7 ± 1.6 (n = 36) |

19.3 ± 2.3 (n = 28) |

| B6 (pH 4.0) | 11.4 ± 1.2 (n = 20) |

19.0 ± 2.1 (n = 21) |

| B6 (all-trans-retinal) | 11.3 ± 1.2 (n = 20) |

18.7 ± 1.9 (n = 24) |

| Rpe65−/− | 19.1 ± 2.5 (n = 30) |

19.5 ± 2.5 (n = 36) |

| Rho-G90D+/+ | 18.6 ± 2.1 (n = 35) |

19.2 ± 2.6 (n = 32) |

| Rho-G90D+/− | 15.7 ± 3.7 (n = 45) |

19.2 ± 2.0 (n = 33) |

Determining the Young’s modulus of unbleached and bleached rhodopsin.

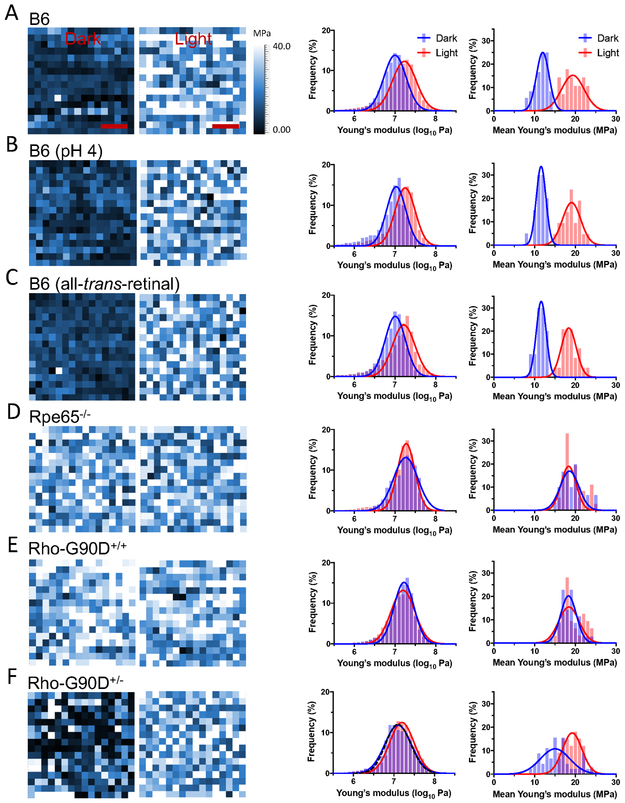

Rhodopsin is locked in the inactive state in the dark by the covalently bound inverse agonist 11-cis-retinal and becomes active upon absorption of a photon of light, forming the metarhodopsin II (MII) state 3. To determine whether or not the inactive and active states of rhodopsin can be differentiated by their stiffness, as indicated in previous AFM-based SMFS studies 14-15, FD-AFM was performed on ROS disc membranes from B6 mice that were conducted in the dark or after photobleaching. Rhodopsin is embedded in the membrane forming nanodomains within the lamellar region of ROS discs 10-11 (Figs. 2A and 2C). FD-AFM was conducted on a 20 × 20 nm2 area of a single nanodomain, and FD-AFM conducted to determine the Young’s modulus in each pixel of the image (Fig. 3). An increase in the Young’s modulus is observed upon photobleaching rhodopsin. The Young’s modulus of rhodopsin in the dark state increased from 12 MPa to 19 MPa upon photobleaching (Fig. 3A, Table 1), a 1.6-fold increase. A clear shift is observed in histograms, where the population of receptors with lower Young’s modulus values in the dark shift to a population of receptor with higher Young’s modulus values after photobleaching (Fig. 3A). Thus, different states of rhodopsin do indeed exhibit different stiffness, which can be detected by FD-AFM.

Figure 3.

Young’s modulus of rhodopsin nanodomains in the dark state and after photobleaching. Representative Young’s modulus maps of a single rhodopsin nanodomain is shown in the first set of images. The Young’s modulus was determined for each pixel in a 20×20 nm2 area (16×16 pixels) of a rhodopsin nanodomain in ROS disc membranes from B6 mice (A), B6 mice at acidic pH (B), B6 mice in the presence of all-trans-retinal (C), Rpe65−/− mice (D), homozygous G90D rhodopsin (Rho-G90D+/+) mice (E), or heterozygous G90D rhodopsin (Rho-G90D+/−) mice (F). The Young’s modulus maps are of rhodopsin nanodomains investigated under dark conditions (left map) or after photobleaching (right map). Scale bar, 5 nm. Histograms were generated from Young’s modulus map data obtained under dark conditions (blue) or after photobleaching (red). The histograms on the left-hand side are those of individual Young’s modulus values determined from each pixel in all Young’s modulus maps generated. The number of pixels analyzed under dark and light conditions are as follows: B6, 7420 and 6134; B6 (pH 4), 5371 and 5620; B6 (all-trans-retinal), 5317 and 5617; Rpe65−/−, 5364 and 5565; Rho-G90D+/+, 5888 and 5184; Rho-G90D+/− 12259 and 5374. The black dashed line in the histogram for heterozygous G90D rhodopsin mice (F) represents a simulated double Gaussian curve generated using parameters from the Gaussian function fit of histograms for B6 mice under dark and light conditions (A). Mean Young’s modulus values were also computed for each individual map and histograms generated. The histograms on the right-hand side are those of mean Young’s modulus values in individual Young’s modulus maps. Histograms of mean Young’s modulus values on the right-hand side are presented in addition to histograms of individual Young’s modulus values on the left-hand side since they better illustrate the difference in Young’s modulus exhibited by inactive and active rhodopsin. The number of maps analyzed under dark and light conditions are as follows: B6, 36 and 28; B6 (pH 4), 20 and 21; B6 (all-trans-retinal), 20 and 24; Rpe65−/−, 30 and 36; Rho-G90D+/+, 35 and 32; Rho-G90D+/−, 45 and 33, respectively. All histograms were fit with a Gaussian function and the fitted parameters are reported in Tables S4 and S5.

Photobleaching of rhodopsin results in the formation of the active Mil state, which decays resulting in the release of all-trans-retinal and formation of the apoprotein opsin 3. The time required to collect data by FD-AFM on photobleached samples likely results in the formation of an appreciable population of opsin in addition to the light-activated MII state 26. Under acidic conditions, opsin adopts a conformation that resembles the active MII state 27-28. Since FD-AFM was conducted at neutral pH, it is ambiguous what state is adopted when opsin is present. Thus, to ensure the determination of the stiffness of the active MII state rather than the state adopted by opsin at neutral pH, photobleached rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes of B6 mice were examined by FD-AFM under acidic conditions to promote the active MII state in any opsin that may have formed. Acidic conditions did not alter the stiffness of the inactive dark state of rhodopsin (Fig. 3B, Table 1). Photobleached rhodopsin under acidic conditions exhibited increased Young’s modulus similar to that of photobleached rhodopsin under neutral pH conditions. Interestingly, the similar Young’s modulus attained after photobleaching at both neutral and acidic pH indicates that opsin exhibits an active state under both conditions. The state adopted by opsin is tested more directly in a later section. Photobleaching was also performed under acidic conditions in the presence of all-trans-retinal to ensure that the active MII state of rhodopsin bound to the chromophore was being probed 26,29. Under these conditions as well, photobleaching of rhodopsin resulted in a similar increase in the Young’s modulus (Fig. 3C, Table 1). Thus, the active MII state of rhodopsin appears to have increased stiffness compared to the inactive state of rhodopsin.

Computational determination of the Young’s modulus of inactive and active rhodopsin.

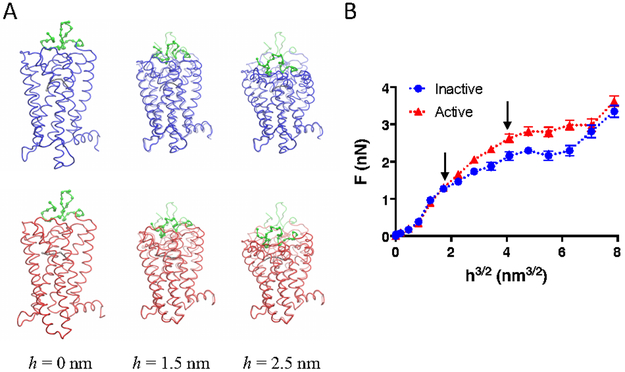

To confirm FD-AFM results indicating an increased stiffness in the structure of rhodopsin upon activation, nanoindentation studies were carried out computationally on coarse-grained (CG) models of inactive and active rhodopsin, which were based on crystal structures 30-31. Similar computational nanoindentation experiments were successfully conducted previously on CG models of cellulose and other protein systems to obtain estimates of Young’s moduli 32-33. Nanoindentation was performed by pressing a sphere into the extracellular surface of rhodopsin (Fig. 4A). Different indentation depths (h) were tested and the resulting force of reaction (F) exerted by the rhodopsin molecule determined to construct a plot of F versus h3/2 (Fig. 4B). The nanoindentation profiles were similar for the inactive and active states of rhodopsin up to an indentation depth of 1.5 nm but began to deviate at greater indentation depths.

Figure 4.

Computational nanoindentation experiments. A. Snapshots of the nanoindentation process from the extracellular side of inactive (blue) and active (red) rhodopsin. The deformation of the rhodopsin molecule is shown for an indentation depth (h) of 0, 1.5, and 2.5 nm. The native conformation of rhodopsin prior to nanoindentation is shown in shadow color. Retinal is shown in CG representation in grey and the amino terminal region of rhodopsin is shown in CG representation in green. B. Nanoindentation profile for inactive (blue) and active (red) rhodopsin. The force of reaction (F) exerted by the rhodopsin molecule at different indentation depths (h) was determined computationally. The mean F is plotted with the standard deviation (n = 40). The linear part of the curve up to h = 2.5 nm was fit to determine the Young’s modulus. The Young’s modulus was 70 and 120 MPa for the inactive and active forms of rhodopsin, respectively. The arrows indicate h = 1.5 nm and h =2.5 nm.

The nanoindentation profile curves were fitted to obtain estimates of the Young’s modulus. The Young’s modulus for the inactive and active states of rhodopsin was 70 and 120 MPa, respectively. These estimates of the Young’s modulus were 6-fold greater than those obtained by FD-AFM. A variety of factors can affect estimates of the Young’s modulus 34, including the speed of nanoindentation. Since the speed of nanoindentation was 10-fold faster in simulations compared to FD-AFM experiments, estimates of the Young’s modulus from simulations is predicted to be higher than those from FD-AFM-experiments 34. A pyramidal AFM tip was used in FD-AFM experiments and therefore data were fit using a Hertzian model for pyramidal AFM tips to determine the Young’s modulus. The geometry of the region of the AFM tip that contacts the sample at the small indentation depths used in FD-AFM experiments may not be well-defined and therefore lead to errors in estimates of the Young’s modulus. FD curves were also fit to a Hertzian model for spherical AFM tips to see if estimates of the Young’s modulus became more similar to those derived computationally. Estimates of the Young’s modulus was 4.6 ± 0.7 and 7.2 ± 1.1 MPa for dark state and photobleached rhodopsin, respectively. These values are lower than those obtained from fits using a Hertzian model for pyramidal tips (Table 1) and deviate even more from the estimates determined computationally.

Further studies are required to determine whether or not there are other factors that contribute to the observed differences in estimates of the Young’s modulus obtained from FD-AFM and simulations. Despite this difference in estimates, computational nanoindentation experiments showed a 1.7-fold increase in the Young’s modulus for the active state of rhodopsin compared to the inactive state of rhodopsin, which is similar to the increase observed from estimates obtained by FD-AFM. Thus, both FD-AFM and computational nanoindentation experiments indicate that the active state of rhodopsin exhibits increased stiffness over the inactive state of the receptor. For the purposes of the current study, it is the relative rather than absolute Young’s modulus value that is critical. The consistency in estimates of the relative Young’s modulus values demonstrates the utility of using the stiffness of the receptor molecule as an indicator of the state of the receptor.

FD-AFM characterization of constitutively active forms of rhodopsin.

Several point mutations in rhodopsin have been identified to cause constitutive activity and retinal diseases 3, but the molecular basis of these diseases is still unclear. Previously, two constitutively active forms of rhodopsin, the apoprotein opsin and G90D mutant rhodopsin, were investigated by SMFS to reveal a more rigid structure compared to the inactive state of the wild-type receptor 14-15. These constitutively active forms were examined here by FD-AFM to deter mine whether or not these constitutively active receptors adopt a stiffer structure, which is indicative of an active state, and to quantify the proportion of receptors adopting an inactive or active state.

To study the apoprotein opsin by FD-AFM, ROS disc membranes from Rpe65−/− mice were examined. These knockout mice are a model for Leber congenital amaurosis and do not express the enzyme retinal pigment epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein (RPE65), which is a critical enzyme required for the regeneration of 11-cis-retinal 35. The absence of RPE65 in this knockout mouse prevents the formation of rhodopsin and only the apoprotein opsin is present in ROS disc membranes. The constitutively active G90D rhodopsin mutant causes congenital night blindness 36. G90D rhodopsin was examined by FD-AFM from ROS disc membranes prepared from a transgenic mouse expressing the G90D mutant on a rhodopsin knockout background (Rho-G90D+/+) 37. FD-AFM of opsin or G90D rhodopsin in the nanodomains of ROS disc membranes revealed that both constitutively active forms exhibited a Young’s modulus of 19 MPa, both when experiments were conducted in the dark or after photobleaching (Figs. 3D and 3E, Table 1). Both constitutively active receptor forms exhibited the same stiffness as photobleached rhodopsin from B6 mice, indicating that they both adopt an active state independent of light. Thus, this increase in Young’s modulus is intrinsic to the state achieved by the receptor molecules rather than some non-specific effect caused by photobleaching.

Since inactive and active states of rhodopsin are distinguishable by monitoring the Young’s modulus, a mixture of inactive and active states was examined to determine whether or not they could be distinguished within a single nanodomain image. Heterozygous mice that express both wild-type and G90D rhodopsin (Rho-G90D+/−) were examined by FD-AFM. In experiments conducted in the dark, wild-type rhodopsin is expected to be inactive while G90D rhodopsin is expected to be active. In experiments conducted in the dark, the Young’s modulus maps of nanodomains revealed that there was a mixture of inactive and active states of the receptor (Fig. 3F). This map contrasts with those obtained with other mice, which displayed only a single state of the receptor (Figs. 3A-3E). Consistent with a mixture of inactive and active forms of the receptor within a nanodomain, the average Young’s modulus value was 16 MPa (Table 1), which was intermediate between that of the inactive and active states. Since the difference in Young’s modulus is not that large between inactive and active rhodopsin, histograms of the Young’s modulus do not exhibit a distinct bimodal distribution (Fig. 3F). However, simulating a double Gaussian function based on parameters obtained from the Gaussian fitting of Young’s modulus values for the inactive and active states of the wild-type receptor (Fig. 3A) generated an almost identical distribution as that observed in samples from Rho-G90D+/− mice (Fig. 3F). These studies demonstrate that a mixture of states can be distinguished and mapped. Nanodomains consist of oligomeric rhodopsin 10. Wild-type and G90D rhodopsin appear to be randomly incorporated into the oligomers forming nanodomains. Wild-type rhodopsin remains inactive even in the presence of the constitutively active G90D mutant. Upon photobleaching samples, all receptors adopt the active state with a higher Young’s modulus of 19 MPa (Fig. 3F, Table 1).

Conformational state of constitutively active forms of rhodopsin.

Examining both photobleached rhodopsin and constitutively active forms of the light receptor indicate that the active state of rhodopsin adopts a stiffer structure when probed from the extracellular surface. The origin of the increased stiffness is unclear. The crystal structure of the active MII state of rhodopsin exhibits an extensive hydrogen bond network, presumably important for activation of the receptor, that propagates throughout the length of the receptor that is not present in the inactive rhodopsin structure 31. This hydrogen bond network may contribute to the increased stiffness observed by FD-AFM. Light-activation of rhodopsin is known to allow water to access the interior of the rhodopsin molecule, allowing the hydrolysis of the chromophore 38. A study using small-angle neutron scattering with quasielastic neutron scattering indicated that light-activation of rhodopsin results in the penetration of water into the interior of the receptor, which results in a more tightly packed interior and more compact core structure that can facilitate the movement of transmembrane helices and coupling to signaling partners 39. This compact core would exhibit higher stiffness when pressed by the AFM probe. Thus, the stiffness measured by FD-AFM appears to be a result of changes in receptor structure required for activation.

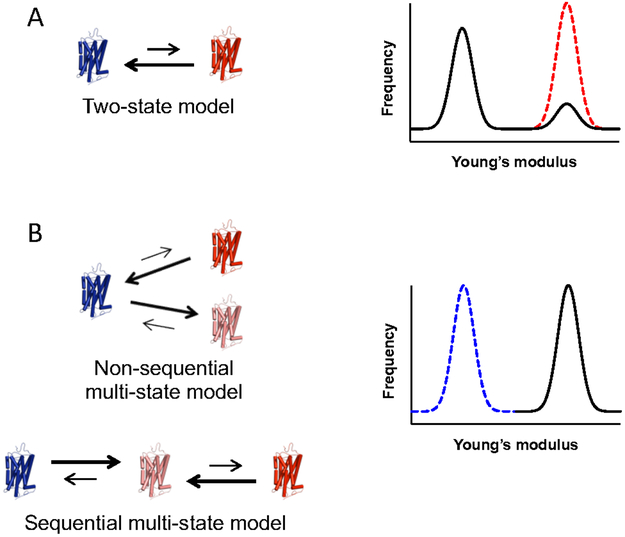

A major unanswered question is whether or not the light-activated state in wild-type rhodopsin is the same as the constitutively active state. To address this question, two models of GPCR activation are considered to describe the mechanism of constitutive activity. The action of GPCRs is often described in terms of models where different states of the receptor are in equilibrium. The most commonly used model is the classical two-state model 40, where the receptor can form either a single inactive state or a single active state (Fig. 5A). Constitutive activity of GPCRs is often rationalized within the context of the two-state model 41-42. Within the context of this model, constitutive activity arises from a shift in equilibrium in favor of the active state in the absence of agonist, or light in the case of rhodopsin. A more recent update has been made to the classical two-state model description of GPCR activity referred to as functional selectivity or biased agonism 43-46, where the receptor can adopt multiple active states with unique signaling properties. Multiple active states can arise sequentially or nonsequentially (Fig. 5B). Within the context of multi-state models, constitutive activity can arise from a shift in equilibrium in favor of either the agonist/light-activated state or a distinct active state.

Figure 5.

Models of receptor activation to describe low levels of constitutive activity. A. The classical two-state model of receptor activation. The receptor exists in equilibrium between a single inactive state (blue) and single active state (red). Low levels of constitutive activity arise from a small population of receptors adopting an active state. In this scenario, Young’s modulus histograms are predicted to exhibit a large population corresponding to the inactive state and a small population corresponding to an active state. The dashed red line represents a scenario where all receptors adopt an active conformation. B. Multi-state models. In either non-sequential or sequential multi-state models, the receptor can adopt multiple active states (red and pink). Low constitutive activity can arise even when the equilibrium is completely shifted to a low activity active state (pink). In this scenario, Young’s modulus histograms are predicted to exhibit a single population of receptors in the active conformation (black line). The dashed blue line represents a scenario where all receptors adopt an inactive conformation.

The activity of G90D rhodopsin or opsin in vivo is estimated to be less than 1 % of that originating from the MII state after light activation of wild-type rhodopsin 37, 47-49. The two-state model is restrictive in describing constitutive activity as the level of constitutive activity can only be modulated by the shift in equilibrium at the basal state. Thus, a low level of constitutive activity can occur only if a small population of receptors adopts the active state while most of the receptor remains in an inactive state (Fig. 5A). This distribution is not observed for either G90D rhodopsin or opsin (Figs. 3D and 3E). In these instances, most receptors adopt an active state indicated by the increase in Young’s modulus, which cannot be accommodated by the classical two-state model. In contrast, within the context of multi-state models, low constitutive activity not only can arise from changes in equilibrium but also the particular active state that is formed. The constitutively active form could be an active state with low activity, and therefore low activity can be achieved even if all receptors adopt this particular active state, which is indicated by the FD-AFM data. Thus, in contrast to the classical two-state model, the multistate models are consistent with the FD-AFM data indicating most of the G90D rhodopsin or opsin adopt an active state.

While constitutive activity of GPCRs is often rationalized within the context of the two-state model 41-42, the FD-AFM data here on constitutively active forms of rhodopsin point to a multi-state model where constitutively active rhodopsin achieves an alternate active state to the light-activated MII state. The notion of multiple active states implied here for rhodopsin is consistent with other GPCRs that display functional selectivity or biased agonism 43-46. It is unclear what the precise structural differences are that define the various active states in rhodopsin implied by the data presented in the current study. The ability of rhodopsin to adopt multiple active states has been demonstrated by double electron-electron resonance spectroscopy on rhodopsin reconstituted into nanodiscs 50. Electrophysiological measurements in photoreceptor cells expressing G90D rhodopsin have demonstrated the possibility that G90D rhodopsin adopts an active conformation different from the light-activated MII state 47. While G90D rhodopsin is expected to have some similarities to the MII state, as demonstrated by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy 51, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy studies indicate that the mutant has distinct structural changes from that of the MII state 52. Nonetheless, the MII state and constitutively active states examined in the current study all exhibit increased Young’s modulus as measured by FD-AFM. The active state of other GPCRs may also be detectable by FD-AFM since agonist-activated β2 adrenergic receptors also exhibit increased rigidity along the vertical axis when examined by SMFS 16. FD-AFM data here supports the notion of GPCRs adopting multiple active states. This expanded view of GPCR activity can provide important insights into how different constitutively active forms of rhodopsin can cause a range of inherited retinal disease with variable phenotypes 3.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

ROS disc membrane preparation.

ROS disc membranes were isolated from C57Bl/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), Rpe65−/− mice 35, transgenic mice expressing G90D rhodopsin on a rhodopsin knockout background (Rho-G90D+/+), or transgenic mice heterozygous for G90D rhodopsin and wild-type rhodopsin (Rho-G90D+/−) 37. ROS disc membranes were prepared under dim red light conditions. Mice were maintained under cyclic light conditions and were sacrificed at 6 weeks of age. All animal studies reported here were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. ROS disc membranes were prepared from 9-15 mice as described previously 53-55. ROS disc membranes were resuspended in Ringer's buffer (10 mM Hepes, 130 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 2.4 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, and 0.02 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). 2-3 different preparations of the same mouse line were examined by FD-AFM.

F-D AFM.

ROS disc membranes or purple membrane from H. salinarum (MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO) were prepared for AFM by adsorption onto freshly cleaved mica and washing in Ringer’s buffer as described previously 55-56. ROS disc membranes were diluted 50-fold in Ringer’s buffer prior to adsorption on mica. To examine the dark state of rhodopsin, experiments were carried out under dim red light conditions. To examine the photobleached state of rhodopsin, ROS disc membranes were exposed to white light (~600 lux) for 5 min, adsorbed onto freshly cleaved mica, and then examined by AFM under the same white light conditions. AFM experiments were conducted in Ringer’s buffer at room temperature. Experiments under acidic conditions were conducted in Ringer’s buffer with the pH adjusted to 4.0 by HCl. Experiments conducted in the presence of all-trans-retinal were also conducted using acidic Ringer’s buffer. Stock solutions of all-trans-retinal (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). 1 μL of ROS disc membranes was added to 50 μL acidic Ringer’s buffer containing 200 μM all-trans-retinal. Photobleaching was conducted on this diluted solution as described above. Samples were adsorbed on freshly cleaved mica and rinsed in acidic Ringer’s buffer containing 200 μM all-trans-retinal. AFM experiments were conducted in this buffer.

Contact mode imaging and FD-AFM experiments were conducted on a Keysight 5500 AFM (Keysight Technologies, Santa Rosa, CA) equipped with an infrared laser using PicoView 1.20 software. Silicon nitride tips (DNP-S, Bruker Corporation, Camarillo, CA) with nominal spring constants of 0.058-0.062 N/m were used for AFM experiments. The spring constant and deflection sensitivity was determined for each tip used. The spring constant of the cantilever was determined by Thermal K method using PicoView 1.20 software 57. The deflection sensitivity was determined from FD curves obtained from mica. Deflection and height topographic images were first collected using contact mode imaging 55. For FD-AFM, an area of 20×20 nm2 was selected and a topographic image obtained. Each topographic image was divided into an area consisting of 16×16 pixels and FD curves were obtained for each pixel using an applied force of ~800 pN and a tip speed of 6.25 μm/s. Indentation depths of 2-3 nm were used for rhodopsin nanodomains. The Young’s modulus was computed for each pixel of a topographic image using a plug-in package from Keysight Technologies (pico-café.com). The Young’s modulus was computed by fitting the approach FD curve (Fig. 1A), as described previously 58. The approach FD curve was fitted using Eq. 1 to determine the Young’s modulus, which is based on a Hertzian model for pyramidal AFM tips 58-59.

| (1) |

F is the loading force on the contact area, E is the Young’s modulus of the sample, ν is the Poisson’s ratio of the sample, h is the deformation of the sample, and θ is the opening angle of the pyramidal tip (18.75° for DNP-S tips), and the effective radius of contact is given by htanθ /21/2. The Poisson’s ratio (ν) for soft biological samples is considered to be 0.5 60-61. Analysis of FD-AFM data was performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

For some data, a Hertzian model for spherical AFM tips was considered. In those instances, the approach FD curve was fitted using Eq. 2, as described previously 58. Rind is the radius of the AFM tip and was set at 10 nm, the nominal tip radius for DNP-S AFM tips.

| (2) |

Computational nanoindentation method.

CG models of rhodopsin were generated based on crystal structures of the inactive state (PDB: 1U19)30 and the active state (PDB: 3PXO)31. The CG model employed represented each amino acid by beads located at the Cα atom position and the potential energy as defined by Eq. 3.

| (3) |

The first three terms on the right-hand side in Eq. 3 correspond to the harmonic pseudo-bond, bond angle, and dihedral potentials. Values of the elastic constants are Kr = 10,000 kcal/mol/nm2 (69.5 N/m), Kθ = 45 kcal/mol/rad2, and Kϕ = 5.0 kcal/mol/rad2, which were derived from all-atom simulations 62. The values for r0, θ0, and ϕ0 correspond to the native distances between two, three, and four Caα atoms, respectively, and they favor the native geometry. The fourth term on the right-hand side of Eq. 3 considers the non-bonded contact interactions, as described by the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potentials. Here, εij was assumed to be uniform and equal to ε = 1.5 kcal/mol, which was also derived from all-atom simulations 62. This approach works well when comparing the theoretical results on protein stretching to experimental data and on nanoindentation of biological fibrils and virus capsids 32, 63-65. The strength, έ, of the repulsive non-native term was set to equal ε.

The CG models of the inactive and active states of rhodopsin take into account native distances as in Gō-like models, which were determined by the overlap criterion 66. In practice, each heavy atom was assigned a van der Waals radius as determined previously 67. A sphere with the radius enlarged by 1.24 was built around the atom. If two amino acids had heavy atoms with overlapping spheres, this was denoted as a native contact formed between those two Cα atoms. These native contacts represent hydrophobic and ionic bridge interactions. Only contacts with ∣i – j∣ > 4 were considered. The parameter σij is equal to rij0/21/6, where rij0 is the distance between two Cα atoms that form native contacts. The last term in Eq. 3 describes the repulsion between non-native contacts, where rcut = 0.4 nm. The CG models for the retinal molecules comprises four CG beads, which were derived in a similar manner as that of hexaose-Man5B complex determined previously 62. The interactions between retinal and the rhodopsin protein in the CG models were determined using the overlap criterion as described above. The backbone stiffness for the retinal molecules were Kr = 2,500 kcal/mol/nm2 (17.4 N/m), Kθ = 25 kcal/mol/rad2, and Kϕ = 0.46 kcal/mol/rad2. The equilibrium distances, r0, θ0, and ϕ0, were taken from the PDB structures.

The CG models do not explicitly take into account the membrane. To capture the effects of the lipid bilayer, the position was restrained of Cα atoms predicted to be inside the membrane and equidistant from the axial center of the protein confined between two concentric cylinders with radii of r – σ = 10 Å and r + σ = 1.4 nm. The ideal radii were determined by constructing histograms of the perpendicular distance towards the cylinder axis for all CG beads. The mean (r), equal to 1.2 nm, which represents the average distance of Cα atoms that are symmetrically distributed inside a cylinder, and the standard deviation (σ), equal to 0.2 nm, were determined from fitting histograms to a Gaussian function. The restraints were applied to the position of the Cα atoms using a harmonic potential centered at the equilibrium position of the Cα atoms. The value of the spring constant was Krest = 1,000 kcal/mol/nm2 (6.95 N/m), which is a typical value used for restraining particles in umbrella sampling simulations and is weak enough to mimic the lipid bilayer environment.

In nanoindentation simulations, rhodopsin was placed above a repulsive plate and the deformation was induced towards the plate along the z-direction. The interaction with the flat plate was described by a repulsive potential that scales as z0−10, where z0 is the distance between the plate and the Cα atom. The dynamic role of the indenter was described by a sphere that generates a purely repulsive potential: Vind = 4εtip[(σ0/r)12] for r < Rind and σ0 = Rind/21/6. Rind defines the curvature of the indenter and was set at 10 nm. The value of εtip was determined to be 20 kcal/mol. The indentation process was implemented at a speed of νind = 5 × 105 nm/τ (~ 50 μm/s). The characteristic time scale, τ, was in the order of 1 ns.

CG simulations were carried out with an implicit solvent at 300 K, which corresponds to kBT = 0.59 kcal/mol, where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T the temperature. Langevin velocity-dependent (over) damping and random forces were used to represent effects related to the solvent. The integration step was 0.005 τ. The systems were studied typically for a duration of 1000 τ after equilibrating them for 100 τ. To capture characteristic thermal fluctuations for each system, results were averaged over 40 independent trajectories. The forces were monitored at time intervals of τ and were averaged over an interval of 10 τ, which corresponds to the typical displacement of a Cα atom of 0.1 nm. This was sufficient to capture the characteristic information to generate F versus h3/2 nanoindentation curves. The Young’s modulus (E) was computed by fitting the slope of the linear part of the nanoindentation curve (Fig. 4B) to Eq. 2, which is based on a Hertzian model for spherical AFM tips. The Poisson coefficient (ν) was taken as the experimental value of 0.5, which corresponds to isotropic deformation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Heather Butler and Kathryn Zongolowicz for maintaining mouse colonies and John Denker for genotyping mice. We thank T. Michael Redmond (National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD) for providing Rpe65−/− mice and Paul A. Sieving (National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD) for providing Rho-G90D+/+ mice. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01EY021731 and P30EY011373), Research to Prevent Blindness (Unrestricted Grant), National Science Centre, Poland (2017/26/D/NZ1/00466, 2015/19/P/ST3/03541, and 2014/15/Z/NZ1/00037), European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 665778), and PLGrid Infrastructure.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: “Just Accepted” manuscripts have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication. They are posted online prior to technical editing, formatting for publication and author proofing. The American Chemical Society provides “Just Accepted” as a service to the research community to expedite the dissemination of scientific material as soon as possible after acceptance. “Just Accepted” manuscripts appear in full in PDF format accompanied by an HTML abstract. “Just Accepted” manuscripts have been fully peer reviewed, but should not be considered the official version of record. They are citable by the Digital Object Identifier (DOI®). “Just Accepted” is an optional service offered to authors. Therefore, the “Just Accepted” Web site may not include all articles that will be published in the journal. After a manuscript is technically edited and formatted, it will be removed from the “Just Accepted” Web site and published as an ASAP article. Note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the manuscript text and/or graphics which could affect content, and all legal disclaimers and ethical guidelines that apply to the journal pertain. ACS cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in these “Just Accepted” manuscripts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sriram K; Insel PA, G Protein-Coupled Receptors as Targets for Approved Drugs: How Many Targets and How Many Drugs? Mol Pharmacol 2018, 95 (4), 251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauser AS; Attwood MM; Rask-Andersen M; Schioth HB; Gloriam DE, Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16 (12), 829–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park PS, Constitutively active rhodopsin and retinal disease. Advances in pharmacology 2014, 70, 1–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian H; Furstenberg A; Huber T, Labeling and Single-Molecule Methods To Monitor G Protein-Coupled Receptor Dynamics. Chem Rev 2017, 117 (1), 186–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calebiro D; Sungkaworn T, Single-Molecule Imaging of GPCR Interactions. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2018, 39 (2), 109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sungkaworn T; Jobin ML; Burnecki K; Weron A; Lohse MJ ; Calebiro D, Single-molecule imaging reveals receptor-G protein interactions at cell surface hot spots. Nature 2017, 550 (7677), 543–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dufrene YF; Ando T; Garcia R; Alsteens D; Martinez-Martin D; Engel A; Gerber C; Muller DJ, Imaging modes of atomic force microscopy for application in molecular and cell biology. Nat Nanotechnol 2017, 12 (4), 295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whited AM; Park PS, Atomic force microscopy: a multifaceted tool to study membrane proteins and their interactions with ligands. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1838 (1 Pt A), 56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller DJ, AFM: a nanotool in membrane biology. Biochemistry 2008, 47 (31), 7986–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang Y; Fotiadis D; Filipek S; Saperstein DA; Palczewski K ; Engel A, Organization of the G protein-coupled receptors rhodopsin and opsin in native membranes. J Biol Chem 2003, 278 (24), 21655–21662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whited AM; Park PSH, Nanodomain organization of rhodopsin in native human and murine rod outer segment disc membranes. Bha-Biomemhranes 2015, 1848 (1), 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakshit T; Senapati S; Sinha S; Whited AM; Park PS-H, Rhodopsin forms nanodomains in rod outer segment disc membranes of the cold-blooded Xenopus laevis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10 (10), e0141114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buzhynskyy N; Salesse C; Scheuring S, Rhodopsin is spatially heterogeneously distributed in rod outer segment disk membranes. J Mol Recognit 2011, 24 (3), 483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawamura S; Colozo AT; Ge L; Muller DJ; Park PS, Structural, energetic, and mechanical perturbations in rhodopsin mutant that causes congenital stationary night blindness. J Biol Chem 2012, 287 (26), 21826–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawamura S; Gerstung M; Colozo AT; Helenius J; Maeda A; Beerenwinkel N; Park PS; Muller DJ, Kinetic, energetic, and mechanical differences between dark-state rhodopsin and opsin. Structure 2013, 21, 426–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zocher M; Fung JJ; Kobilka BK; Muller DJ, Ligand-specific interactions modulate kinetic, energetic, and mechanical properties of the human beta2 adrenergic receptor. Structure 2012, 20 (8), 1391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawamura S; Colozo AT; Muller DJ; Park PS, Conservation of molecular interactions stabilizing bovine and mouse rhodopsin. Biochemistry 2010, 49 (49), 10412–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spoerri PM; Kato HE; Pfreundschuh M; Mari SA; Serdiuk T; Thoma J; Sapra KT; Zhang C; Kobilka BK; Muller DJ, Structural Properties of the Human Protease-Activated Receptor 1 Changing by a Strong Antagonist. Structure 2018, 26 (6), 829–838 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alsteens D; Pfreundschuh M; Zhang C; Spoerri PM; Coughlin SR; Kobilka BK; Muller DJ, Imaging G protein-coupled receptors while quantifying their ligand-binding free-energy landscape. Nat Methods 2015, 12 (9), 845–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dufrene YF; Martinez-Martin D; Medalsy I; Alsteens D; Muller DJ, Multiparametric imaging of biological systems by force-distance curve-based AFM. Nat Methods 2013, 10 (9), 847–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinckier A; Semenza G, Measuring elasticity of biological materials by atomic force microscopy. FEBS Lett 1998, 430 (1-2), 12–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voss A; Dietz C; Stocker A; Stark RW, Quantitative measurement of the mechanical properties of human antibodies with sub-10-nm resolution in a liquid environment. Nano Res 2015, 8 (6), 1987–1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong M; Husale S; Sahin O, Determination of protein structural flexibility by microsecond force spectroscopy. Nat Nanotechnol 2009, 4 (8), 514–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medalsy I; Hensen U; Muller DJ, Imaging and quantifying chemical and physical properties of native proteins at molecular resolution by force-volume AFM. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2011, 50 (50), 12103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfreundschuh M; Martinez-Martin D; Mulvihill E; Wegmann S; Muller DJ, Multiparametric high-resolution imaging of native proteins by force-distance curve-based AFM. Nat Protoc 2014, 9 (5), 1113–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schafer CT; Fay JF; Janz JM; Farrens DL, Decay of an active GPCR: Conformational dynamics govern agonist rebinding and persistence of an active, yet empty, receptor state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113 (42), 11961–11966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel R; Siebert F, Conformations of the active and inactive states of opsin. J Biol Chem 2001, 276 (42), 38487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheerer P; Park JH; Hildebrand PW; Kim YJ; Krauss N; Choe HW; Hofmann KP; Ernst OP, Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature 2008, 455 (7212), 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jager S; Palczewski K; Hofmann KP, Opsin/all-trans-retinal complex activates transducin by different mechanisms than photolyzed rhodopsin. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (9), 2901–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada T; Sugihara M; Bondar AN; Elstner M; Entel P; Buss V, The retinal conformation and its environment in rhodopsin in light of a new 2.2 A crystal structure. J Mol Biol 2004, 342 (2), 571–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choe HW; Kim YJ; Park JH; Morizumi T; Pai EF; Krauss N; Hofmann KP; Scheerer P; Ernst OP, Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature 2011, 471 (7340), 651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poma AB; Chwastyk M; Cieplak M, Elastic moduli of biological fibers in a coarse-grained model: crystalline cellulose and beta-amyloids. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2017, 19 (41), 28195–28206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poma AB; Guzman HV; Li MS; Theodorakis PE, Mechanical and thermodynamic properties of Abeta42, Abeta40, and alpha-synuclein fibrils: a coarse-grained method to complement experimental studies. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 2019, 10, 500–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medalsy ID; Muller DJ, Nanomechanical properties of proteins and membranes depend on loading rate and electrostatic interactions. ACS Nano 2013, 7 (3), 2642–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redmond TM; Yu S; Lee E; Bok D; Hamasaki D; Chen N; Goletz P; Ma JX; Crouch RK; Pfeifer K, Rpe65 is necessary for production of 11-cis-vitamin A in the retinal visual cycle. Nat Genet 1998, 20 (4), 344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sieving PA; Richards JE; Naarendorp F; Bingham EL; Scott K; Alpern M, Dark-light: model for nightblindness from the human rhodopsin Gly-90-->Asp mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92 (3), 880–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sieving PA; Fowler ML; Bush RA; Machida S; Calvert PD; Green DG; Makino CL; McHenry CL, Constitutive "light" adaptation in rods from G90D rhodopsin: a mechanism for human congenital nightblindness without rod cell loss. J Neurosci 2001, 21 (15), 5449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wald G; Brown PK, The molar extinction of rhodopsin. J Gen Physiol 1953, 37 (2), 189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perera S; Chawla U; Shrestha UR; Bhowmik D; Struts AV; Qian S; Chu XQ; Brown MF, Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Reveals Energy Landscape for Rhodopsin Photoactivation. J Phys Chem Lett 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leff P, The two-state model of receptor activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1995, 16 (3), 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samama P; Cotecchia S; Costa T; Lefkowitz RJ, A mutation-induced activated state of the b2-adrenergic receptor. Extending the ternary complex model. J Biol Chem 1993, 268 (7), 4625–4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spalding TA; Burstein ES; Wells JW; Brann MR, Constitutive activation of the M5 muscarinic receptor by a series of mutations at the extracellular end of transmembrane 6. Biochemistry 1997, 36 (33), 10109–10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park PS, Ensemble of G protein-coupled receptor active states. Curr Med Chem 2012, 19 (8), 1146–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajagopal S; Rajagopal K; Lefkowitz RJ, Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010, 9 (5), 373–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa-Neto CM; Parreiras ESLT; Bouvier M, A Pluridimensional View of Biased Agonism. Mol Pharmacol 2016, 90 (5), 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobilka BK; Deupi X, Conformational complexity of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2007, 28 (8), 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dizhoor AM; Woodruff ML; Olshevskaya EV; Cilluffo MC; Cornwall MC; Sieving PA; Fain GL, Night blindness and the mechanism of constitutive signaling of mutant G90D rhodopsin. J Neurosci 2008, 28 (45), 11662–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan J; Woodruff ML; Cilluffo MC; Crouch RK; Fain GL, Opsin activation of transduction in the rods of dark-reared Rpe65 knockout mice. J Physiol 2005, 568 (Pt 1), 83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melia TJ Jr.; Cowan CW; Angleson JK; Wensel TG, A comparison of the efficiency of G protein activation by ligand-free and light-activated forms of rhodopsin. Biophys J 1997, 73 (6), 3182–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Eps N; Caro LN; Morizumi T; Kusnetzow AK; Szczepek M; Hofmann KP; Bayburt TH; Sligar SG; Ernst OP; Hubbell WL, Conformational equilibria of light-activated rhodopsin in nanodiscs. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2017, 114 (16), E3268–E3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zvyaga TA; Fahmy K; Siebert F; Sakmar TP, Characterization of the mutant visual pigment responsible for congenital night blindness: a biochemical and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy study. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (23), 7536–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim JM; Altenbach C; Kono M; Oprian DD; Hubbell WL; Khorana HG, Structural origins of constitutive activation in rhodopsin: Role of the K296/E113 salt bridge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101 (34), 12508–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nickell S; Park PS; Baumeister W; Palczewski K, Three-dimensional architecture of murine rod outer segments determined by cryoelectron tomography. J Cell Biol 2007, 177 (5), 917–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park PS; Sapra KT; Jastrzebska B; Maeda T; Maeda A; Pulawski W; Kono M; Lem J; Crouch RK; Filipek S; Muller DJ; Palczewski K, Modulation of molecular interactions and function by rhodopsin palmitylation. Biochemistry 2009, 48 (20), 4294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Senapati S; Park PS, Investigating the Nanodomain Organization of Rhodopsin in Native Membranes by Atomic Force Microscopy. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1886, 61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park PS; Muller DJ, Dynamic single-molecule force spectroscopy of rhodopsin in native membranes. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1271, 173–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hutter JL; Bechhoefer J, Calibration of Atomic-Force Microscope Tips. Review of Scientific Instruments 1993, 64 (7), 1868–1873. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fuhrmann A; Staunton JR; Nandakumar V; Banyai N; Davies PCW; Ros R, AFM stiffness nanotomography of normal, metaplastic and dysplastic human esophageal cells. Physical Biology 2011, 8 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rico F; Roca-Cusachs P; Gavara N; Farre R; Rotger M; Navajas D, Probing mechanical properties of living cells by atomic force microscopy with blunted pyramidal cantilever tips. Physical Review E 2005, 72 (2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dimitriadis EK; Horkay F; Maresca J; Kachar B; Chadwick RS, Determination of elastic moduli of thin layers of soft material using the atomic force microscope. Biophys J 2002, 82 (5), 2798–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yokokawa M; Takeyasu K; Yoshimura SH, Mechanical properties of plasma membrane and nuclear envelope measured by scanning probe microscope. J Microsc 2008, 232 (1), 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poma AB; Chwastyk M; Cieplak M, Polysaccharide-Protein Complexes in a Coarse-Grained Model. J Phys Chem B 2015, 119 (36), 12028–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sulkowska JI; Cieplak M, Selection of optimal variants of Go-like models of proteins through studies of stretching. Biophys J 2008, 95 (7), 3174–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sikora M; Sulkowska JI; Witkowski BS; Cieplak M, BSDB: the biomolecule stretching database. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39 (Database issue), D443–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cieplak M; Robbins MO, Nanoindentation of 35 virus capsids in a molecular model: relating mechanical properties to structure. PLoS One 2013, 8 (6), e63640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolek K; Gomez-Sicilia A; Cieplak M, Determination of contact maps in proteins: A combination of structural and chemical approaches. J Chem Phys 2015, 143 (24), 243105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsai J; Taylor R; Chothia C; Gerstein M, The packing density in proteins: standard radii and volumes. J Mol Biol 1999, 290 (1), 253–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.