Abstract

Support for research involving children has a complicated history. Pediatricians and families have a unique opportunity to share perspectives about the relevance of pediatric clinical research. A national broadcast film on pediatric clinical research was developed to improve knowledge about and willingness to consider a clinical study. The film was delivered to a public audience employing a pre-post design comparing knowledge about clinical research before and after watching If Not for Me: Children and Clinical Studies. Change was measured by difference in number of questions answered correctly prior to and after viewing the film. Engagement was measured by survey and a live feedback qualitative component. Adults viewing the program demonstrated a significant (<.0001) difference in knowledge about pediatric clinical research across all domains. This format appears to be a viable approach for improving public education and as a support tool for pediatricians and pediatric researchers about this topic.

Keywords: pediatric disease, mixed-methods, documentary-style film, children, clinical studies, pediatric research

Introduction

We have enormous success when we are able to communicate to parents and to adults that participating in research is a contribution to the well-being of humanity.

Dr. Fernando Martinez, If Not for Me

Excellence in research is essential to our health and quality of life, yet while many potential participants recognize the need for clinical studies, they avoid participating. An overwhelming majority of people (77%), say that they would consider getting involved in a clinical research study if asked; however, only 10% of those eligible to participate actually do so.1 Recruitment for pediatric clinical trials presents unique challenges, including a lack of information for parents faced with a decision about whether to allow a child to participate. Only one in four U.S. adults would consider allowing their children to participate in clinical research studies.2

Despite best efforts of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to improve and standardize clinical trial recruitment, these efforts have had limited impact on parents who may be asked to enroll their child in a clinical trial. Misperceptions, fears and myths about the well-known (but not representative) mistakes, misconduct or abuse from the earliest days of clinical research persist regardless of much improved safety measures now in place. Lack of sufficient information to counteract misperceptions contributes to low rates of participation.1,3 Pediatricians and pediatric nurses agree that research is important but report that their role as caregivers makes them less willing to encourage parents to participate in pediatric research.4,5 We developed the film, If Not for Me, a national broadcast documentary film, to address this gap. This film presents the journeys of families involved in four different clinical studies as they share their experiences. The objective of the film is to inform the public about the important role clinical studies play in improving treatments of childhood illnesses and to provide a tool for pediatricians to educate their patients and families. The film reveals the emotional challenges the families face related to pediatric clinical research, as they and others in the medical community share their stories about their experience with clinical trials for children.

Educating families about clinical research requires a variety of tools, and a national broadcast program is a widely accessed tool that can hold viewer attention unlike other programs. It also provides an avenue to develop content that can be re-purposed for a variety of audiences including parents of pediatric patients, pediatricians and researchers. Gaining understanding of the concept of clinical studies through a film has the potential to reduce barriers to decisions around participation.

Research Goals/Objectives

The objective of our study was to develop a full length (47-minute) original narrative documentary-style film and to evaluate knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about pediatric clinical research with a general public audience. We also sought to explore participant levels of engagement with this approach.

Study Design/Methods

A mixed-methods study was designed and performed May 2016 – December 2016. The design consisted of three parts where participants: 1) completed the pre-test assessment about clinical research, 2) watched the documentary film with a live feedback qualitative component, and 3) completed the post-test assessment. The post-test assessment was the same survey as the pre-test with additional questions specifically about the film.

Sample

A total of 210 subjects were recruited through Qualtrics (a customer engagement research platform) based on the study recruitment requirement of a broad national sample representative of a general public audience. Participants were asked to access an online portal to complete a screener, and if eligible, the consent form. Eligibility criteria included that the participant had to be 21 years of age or older, had access to a mobile device with internet connection and could understand and read English. Upon consent, participants were asked to complete a pre-test assessing demographic information, knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about clinical research with pediatric populations. The pre-test assessment consisted of 17 True/False questions, 25 Agree/Disagree questions, 19 multiple choice attitudes/beliefs questions, and demographic questions. After completion of the pre-test, participants were provided a link to watch the film, If Not for Me via a private YouTube link and were asked to engage in real-time feedback via comment box. After viewing the film, participants were asked to complete a post-test assessment which included the same True/False, Agree/Disagree, and multiple choice questions, as well as an additional 23 questions specifically about their impressions of the film. After completing the study participants received reimbursement in the form of incentives and cash honorarium through Qualtrics and included a choice of gift cards, PayPal, flight miles, and other similar rewards. The research study was approved by the New England Research Institutes, Inc. Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Analysis

Quantitative

Pre and post test data were collected and analyzed to examine the effectiveness of a national broadcast film to educate about pediatric clinical research. The primary outcome was the change in number of questions answered correctly immediately prior to viewing the program to the number of questions answered correctly after viewing the program.

To estimate the change in knowledge in our sample, we compared pre- and post-test survey scores using a paired t-test. Subjects were asked the same set of questions on the pre- and post-tests in order to eliminate any differences due to variation in question difficulty. A one-sample, one-sided t-test with a 5% type 1 error was performed to test H0: vs. H1: , where is the number of questions answered correctly on the post-test minus the number of question answered correctly on the pre-test. With 210 analyzable subjects, the study had 85% power to detect an effect size of approximately 0.20. This is equivalent to answering one additional question correctly on the post-test compared to the pre-test assuming a standard deviation of five questions. Only subjects who completed both tests were included in the analysis. An additional 58 participants who did not complete the post-test were considered unanalyzable and excluded from analysis.

Secondary analyses on perceptions of clinical studies were conducted on all Agree/Disagree and multiple choice attitudes/beliefs questions. For Agree/Disagree questions, McNemar’s test was used to measure whether a significant proportion of participants moved from agreement to disagreement (or vice versa) from pre- to post-test. For multiple choice attitudes/beliefs questions, the generalized McNemar/Stuart-Maxwell test was used to determine significant changes between agree, neutral, and disagree from pre- to post-test.

Qualitative

While viewing If Not for Me, participants were asked to provide open-ended feedback in real-time. An analyst performed line-by-line “open coding” to develop a codebook for this data. Throughout coding, the analyst tagged emerging themes and summarized the open-ended comments using these descriptive measures.

Results/Discussion

Quantitative Results

Of the ~2100 participants who were invited to participate in the study, 342 participants engaged in the recruitment materials demonstrating interest. Of these, 64 screened out due to a validity check (speeding through materials or inattention/timing out) and 68 dropped out of the study, resulting in 210 active participants. The remaining 210 participants completed the demographic survey, pre-test, viewed the film, and completed the post-test survey. Of the 210 participants, 170 (81%) also provided real time qualitative feedback during the period they watched the film. Demographic characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Sample

| Variable | Response | % (n) | Mean | Std Dev | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–29 | 15.7% (33) | 0.85 | 3.01 | 0.9972 |

| 30–39 | 30.5% (64) | 0.94 | 2.22 | ||

| 40–49 | 16.7% (35) | 1.14 | 2.34 | ||

| 50–59 | 19.5% (41) | 0.93 | 2.04 | ||

| 60–69 | 11.4% (24) | 0.83 | 2.33 | ||

| 70+ | 5.7% (12) | 0.83 | 1.80 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 0.5% (1) | 0.00 | . | ||

| Race | White | 81.0% (170) | 0.94 | 2.29 | 0.8933 |

| Black or African American | 9.5% (20) | 0.90 | 2.88 | ||

| Asian | 7.1% (15) | 0.67 | 2.09 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2.4% (5) | 1.60 | 1.52 | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 7.2% (15) | 0.00 | 2.78 | 0.2471 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 91.9% (192) | 1.02 | 2.27 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 1.0% (2) | 1.50 | 2.12 | ||

| Missing | 1 | . | . | ||

| Gender | Male | 35.9% (75) | 0.37 | 1.92 | 0.0262 |

| Female | 63.6% (133) | 1.26 | 2.47 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 0.5% (1) | 0.00 | . | ||

| Missing | 1 | . | . | ||

| Education | Less than high school | 2.9% (6) | 0.83 | 2.23 | 0.2372 |

| High school graduate | 17.1% (36) | 0.39 | 2.43 | ||

| Technical school or some college | 29.0% (61) | 0.74 | 2.58 | ||

| College graduate or beyond | 51.0% (107) | 1.23 | 2.09 | ||

| Marital Status | Single | 26.0% (54) | 0.98 | 2.62 | 0.1935 |

| Living with partner | 11.5% (24) | 0.29 | 3.07 | ||

| Married | 52.9% (110) | 0.87 | 1.95 | ||

| Divorced or separated | 6.7% (14) | 2.14 | 2.60 | ||

| Widowed | 2.9% (6) | 1.50 | 0.55 | ||

| Missing | 2 | . | . | ||

| Has Children Under Age of 21 | Yes | 50.0% (105) | 0.90 | 2.60 | 0.8121 |

| No | 50.0% (105) | 0.97 | 2.00 | ||

Our sample was generally representative of a broad public audience, with some notable differences. Our sample were more likely to be female (63.6%, compared with 50.8% of the US population), and had higher overall educational attainment than the general population (51.0% college graduate or beyond, compared with 29.8% of the US population).6 Our participants were also slightly more likely to be white (81.0%, compared with 76.9% of the US population) and not Hispanic/Latino (91.9%, compared with 82.2% of the US population).

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the mean score for knowledge of pediatric clinical trials (Table 2) before and after viewing If Not for Me. Participants significantly improved from pre-test (t=5.845, p<0.001) to post-test (M=12.595, SD=2.015). These results suggest that If Not for Me was successful in improving overall knowledge of pediatric clinical trials.

Table 2.

Outcomes: Pre-test and post-test results for the two groups

| Measure | N | mean | std dev | min | max | t stat | p-value |

| Pre-test score (# correct out of 29 questions) | 210 | 12.595 | 2.015 | 6 | 17 | ||

| Post-test score (# correct out of 29 questions) | 210 | 13.529 | 2.418 | 3 | 17 | ||

| Change in score, pre-test to post-test | 210 | 0.933 | 2.314 | −9 | 9 | 5.845 | <0.0001 |

Female participants saw significantly greater improvement from pre- to post-test compared to their male counterparts (Table 1). There were no other differences is performance from pre- to post- by a range of demographics, including age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, or having children under 21.

Participants reported several significant change in attitudes and beliefs about clinical trials when asked a series of questions about pediatric clinical studies (Table 3). Nineteen attitudes/beliefs questions were asked of all participants at pre- and post-test. Of those, sixteen were selected for analysis (study measures were designed prior to completion of film production, and were reviewed for relevancy after study completion. Three questions were deemed unrelated to film content and were not examined). For 13 of the 16 items, attitudes significantly changed after viewing If Not for Me. These attitude/belief changes included participants confidence in research findings (p=0.0011), understanding of the risks associated with participating in a clinical study (p=0.0211), and comfort with the idea of clinical studies (p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Outcomes: Attitudes & Beliefs (n=210)

| Measure | GMN | DF | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I would discuss clinical studies with my child’s pediatrician | 4.33 | 2 | 0.1151 |

| I understand what it means to enroll my child in a clinical study | 12.92 | 2 | 0.0016 |

| I have confidence in research findings | 9.55 | 2 | 0.0084 |

| I have concerns about my child’s information being confidential in a study | 12.66 | 2 | 0.0011 |

| My child would be a guinea pig in a clinical study | 10.51 | 2 | 0.0052 |

| Getting a placebo means my child wouldn’t get good care | 10.75 | 2 | 0.0046 |

| Participating in a clinical study would take too much time | 10.17 | 2 | 0.0062 |

| The risks of participating in a clinical study outweigh the benefits | 7.72 | 2 | 0.0211 |

| Clinical researchers are looking out for my child’s interests | 26.35 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| Researchers do not explain clinical studies in a way that makes sense to me | 19.42 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| Clinical studies should only be conducted in children for very serious, life-threatening illnesses | 0.91 | 2 | 0.6360 |

| If my physician suggested a clinical study for my child, I would trust his/her recommendation | 12.43 | 2 | 0.0020 |

| I am uncomfortable with the idea of clinical studies | 14.83 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| Everyone should have the opportunity to participate in clinical studies | 15.89 | 2 | 0.0004 |

| We have an obligation to do our part by participating in research | 10.02 | 2 | 0.0067 |

| Studies focusing specifically on children are very important | 11.17 | 2 | 0.0038 |

Similarly, we assessed change in perceptions about clinical research focusing on the technical aspects of clinical studies, such as role of healthy volunteers, types of conditions, and differences between adults and children. Of the 25 questions included in the pre- and post-test surveys, 21 questions were selected for analysis as potentially addressed, and thus modifiable, by the film.

Results suggest that after watching the film, participants were significantly more likely to understand many of these technical aspects of clinical research when compared to the pretest survey (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes: Agree/Disagree (n=210)

| Measure | Statistic | DF | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s diseases are not so different from adult diseases that they need to be studied separately | 0.83 | 1 | 0.7728 |

| Children’s treatments are similar to adult treatments for the same diseases | 3.56 | 1 | 0.0593 |

| Medicines that treat symptoms in childhood could prevent diseases in adults | 14.30 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| Clinical studies for children involve only new drugs or treatments | 0.28 | 1 | 0.5994 |

| Clinical studies can be used to improve medications that are already working with some groups of patients | 0.00 | 1 | 1.0000 |

| Participation in research studies is always voluntary | 0.69 | 1 | 0.4054 |

| Studies can empower participants to be more involved in their disease | 0.00 | 1 | 1.0000 |

| Participation in a clinical study can give patients more control over their condition | 11.65 | 1 | 0.0006 |

| Healthy children can participate in a clinical research study | 6.10 | 1 | 0.0136 |

| Children or their parents always have a say in what they are asked to do in a study | 4.17 | 1 | 0.0411 |

| Treatment is different for adults versus children with asthma | 7.81 | 1 | 0.0052 |

| An intervention group is the group that gets the drug or treatment | 4.74 | 1 | 0.0295 |

| It is important to conduct research specifically in underserved or minority populations | 6.42 | 1 | 0.0113 |

| Studies that ask questions through surveys are not considered clinical research | 6.45 | 1 | 0.0111 |

| The only reason to participate in a clinical study is so a child receives better treatment | 3.27 | 1 | 0.0704 |

| There is no reason to conduct research in healthy children | 0.50 | 1 | 0.4795 |

| It is unethical to ask families to participate in research while their children are hospitalized | 0.81 | 1 | 0.3692 |

| Research with children is important because treatments work differently for children than for adults | 3.00 | 1 | 0.0833 |

| Participation in clinical research provides education even if the treatment doesn’t work | 0.47 | 1 | 0.4913 |

| Clinical study participants can’t control who gets to see their personal information | 1.65 | 1 | 0.1985 |

| Mental health conditions cannot be studied in a clinical study | 168 | 1 | <0.0001 |

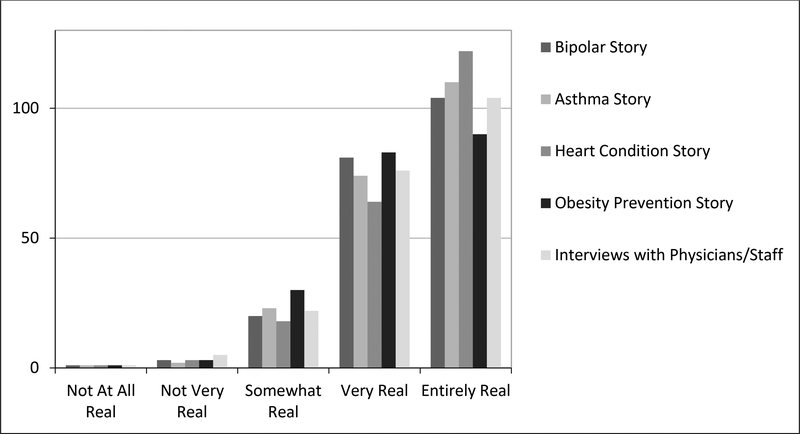

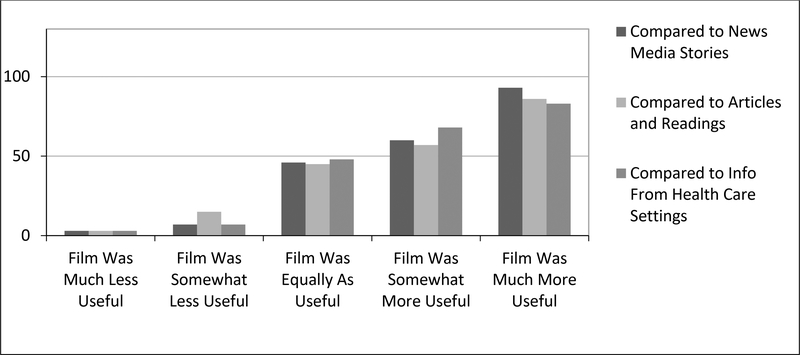

A majority of participants (94.7%) who watched the film reported that it was excellent, very good or good compared with 5.2% who reported it to be fair or poor. Asked if they would recommend the film, 91.4% said they would recommend it to friends, family or co-workers and 57% would talk about it on social media. Figure 1 shows how realistic participants felt the film was. Figure 2 demonstrates how engaged participants felt they were compared to other forms of media to deliver the same message.

Figure 1.

Participant Perceptions of How Realistic the Film Was

Figure 2.

Participant Perceptions of Film Format Compared to Alternate Approaches

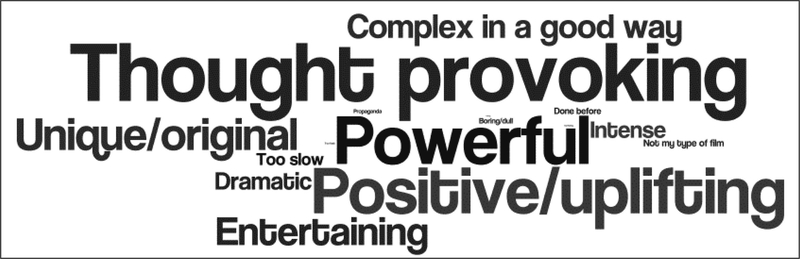

Figure 3 illustrates the words participants felt best described their experience – the larger the word suggests it was selected by more users. When asked how relevant the film was with regard to taking part in a clinical study, 69.5% indicated it was extremely or very relevant compared with 20.5% who reported it was somewhat relevant, and 10% who reported it was not very or not at all relevant.

Figure 3.

Word Cloud of Participant Descriptions

Qualitative Results

The qualitative analysis summarizes real time comments made during the film, and support the quantitative results. Overall, participants who viewed the film found it to be very engaging and educational. Participants learned new information and gained different perspectives on clinical studies. Participants found the film to be interesting, informative, and well done.

“This is so informative about how children are not little adults. All these parents are so brave willing to help science. These stories are so emotional and evocative.”

“A very powerful, motivating and compelling video. A must-see for anyone that has a child or little loved one.”

“This was a very informative video. I’m glad there are parents out there that are willing to have their children participate in these studies to learn more about these diseases to help educate themselves and others and to help them understand these diseases.”

Participants learned new facts and saw the application in terms of clinical studies and the impact clinical research can have in the future.

“These clinical studies will help save lives and help other children. This is important. I love how simple it is. The woman in this film said that the clinical study her son is in is like going to the clinic. That just goes to show that clinical studies are different from what i initially thought.”

“there has been many a study that has all but eradicated certain conditions and diseases. We’d be dealing with way more complications if not for clinical studies.”

“I was under the mistaken view that clinical studies are for testing drugs when, in fact, drug testing is only a part of it. The video was entertaining, inspiring and very informative.”

Participants gained a new perspective for clinical studies. Many found the Asthma trial to be empowering for the trial participants who learned about and how to manage their disease. The GROW obesity prevention trial also provided a new perspective of clinical trials for participants who learned that lifestyle intervention is also considered research.

“I found the Asthma study to be quite interesting and I really like the part where it is empowering to kids in the study to get a grasp of there disease.”

“The obesity study/grow program was different than what I normally think of as far as a study shows goes and I can see the benefits that study will have in the long term on children in America schools and daycares.”

Several participants felt empathy towards the families in the film from either personal experiences with a sick child, being a parent, or just in general feeling empathy for these families enduring such challenges. As one participant summarized, “I really liked this film. Love how the parent were open and honest”. A few participants mentioned how they trusted the experts and doctors shown in the film, sharing sentiments such as “It’s amazing what doctors are able to do... This doctor understands parents and their worries” and “This is heartbreaking, but it sounds like the doctors really care”.

There were a few participants who shared the concerns of one of the families in the film, about being approached to partake in a research study at such a sensitive time, yet many of these participants understood the timeliness of the request. A few participants also shared concerns regarding clinical trials more generally. Overall, they understood the benefits of a clinical trial but had reservations in enrolling themselves or their children in a study, depending on the institution, sponsor, and other factors.

“i tend to agree with the parents that I would be very overwhelmed if a doctor came up to me in such a moment as this and asked me if my child could be part of a study… stating that it’s voluntary is very important and the parents do need to be encouraged during the process and reassured that they will just be monitoring the child and it will not affect them or harm them”

“The film seems a bit long and might be a bit too detailed, but it does a good job of showing families and children for whom participating in research trials was a very positive experience. I am still worried about cases where research is done or controlled by drug and medical device companies, rather than by universities and hospitals”

“My heart goes out to the parents of this child and what they have gone through. I agree with their reasoning on why it is important to enter the clinical trial, but I am not sure I could make the same decision if it were my child”

A few participants shared they would be interested in now participating in a clinical study or enrolling their child in a clinical study, after viewing the film.

“Gives me food for thought about joining a study”

“it would be difficult but i think if this happened to my child i would participate in the study so that the information might help other children and families that might go through this same situation”

Overall, many participants who viewed the film understood the importance of clinical studies, and reflected on how the film changed their perceptions of clinical research in children.

“Clinical research can be a helpful way to find alternate solution to a health problem. But like any studies, outcome is not guaranteed to be beneficial. However, it can also provide a new chance of getting better. This film provide a good example of working together to find solution between doctor and patient.”

“Research is help for a whole array of life styles and diseases. Being part of a clinical is much more than I ever thought it was!”

Discussion

Our findings suggest that a broadcast film can provide a broad platform to educate about pediatric clinical research, both in the public domain and as a tool for pediatricians and pediatric researchers. For more than half a century, we have recognized the challenges of connecting the concept of research to the impact for the general public. Dr. R. Slater (1962) asked a simple question during the Symposium for Clinical Research in the early days of the field, “From the patient’s point of view, what is the difference between a basic scientist and a clinical scientist to whom he looks for mental and physical care?” He concluded, the core difference is that “the results of a clinical scientist’s work directly benefit the patients and others like him”. 7 Our film aims to bridge the gap between the perceived distance from scientific research to clinical care. It demonstrates how scientific research underpins clinical care which, together research can result in saving lives, improving quality of life, and eradicating disease. Over the past half century, clinical trials have become the gold standard for generating robust, unbiased results which compare treatment options for a given condition8 to benefit research subjects and the general public. Numerous published research findings from pediatric trials demonstrate the importance of clinical research, and these results have had significant implications for patient outcomes, health care policy, and health care costs. Yet, two thirds of clinical trials, many addressing challenging or devastating pediatric conditions, fail to reach their recruitment target.9. The result is lack of a robust evidence base for many widely used medications and treatments for childhood diseases. Without broad public understanding of the reasons for, complexities of conducting, and outcomes associated with clinical research, acceptance and participation in clinical trials remains severely threatened.

There are limitations of this study that should be noted. We developed the survey instruments from known or validated measures about clinical trial knowledge. However, there are very limited metrics for general knowledge about pediatric clinical trials, and therefore we had to adapt survey measures to our study. We worked with an established recruitment organization for our sample, although it is possible that participants who are more interested in this format would elect to participate. We report a broad and relatively generalizable sample (although we had more female participants in our sample) which suggests consistency with a general broadcast audience.

Conclusion

Broadcast media has an important role to play in improving education and perceptions about clinical research. It has the power to address the prevailing and enduring fears, mistakes, and myths established from the earliest days of clinical research. The soundbite media barrage of information presenting selective risk factors and often promoted as ‘resulting from a recent clinical study’ further entrenches a skewed view of research outcomes. This type of information impedes the ability to recruit and retain subjects - a key obstacle to clinical research success. Our findings demonstrate that a scientifically solid broadcast media approach can improve knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about pediatric clinical research. Through our companion qualitative data, it also demonstrates that delivering this message through genuine and emotionally connected stories are important contributors to these significant changes. Our findings support that a better informed audience is more likely to report interest in learning about and possibly participating in clinical research. This format also provides an opportunity to assist pediatricians and pediatric researchers in educating families and study participants.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by Grant # R44HL118798, National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to our colleague Victoria Pemberton RNC, MS, CCRC, our clinical collaborators Dr. John Berger, Dr. Shari Barkin, Dr. Fernando Martinez, Dr. Daniel Dickstein, Dr. Francis Moler and Dr. Michael Dean who provided their expertise throughout the process of filming, and our film crews who made the family stories possible. Without these collaborations, this manuscript would not be possible.

Grant Number and/or Funding Institution:

Grant # R44HL118798, National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Center for Information & Study on Clinical Research Participation (CISCRP). Clinical Trial Facts & Figures. 2012; http://www.ciscrp.org/professional/facts_pat.html. Accessed March, 2013.

- 2.HarrisInteractive. Only a quarter (25%) of US adults would consider allowing a child of theirs to participate in a clinical research study. Health Care News. 2004;4(17):1–9. http://www.harrisinteractive.com/news/newsletters/healthnews/HI_HealthCareNews2004Vol4_Iss17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.HarrisInteractive. Misconceptions And Lack of Awareness Greatly Reduce Recruitment For Cancer Clinical Trials Health Care News. 2001;1(3):1–3. http://www.harrisinteractive.com/news/newsletters/healthnews/HI_HealthCareNews2001Vol1_iss3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caldwell PH, Murphy SB, Butow PN, Craig JC. Clinical trials in children. Lancet. 2004;364(9436):803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhal N, Oberle K, Darwish A, Burgess E. Attitudes of health-care providers towards research with newborn babies. J Perinatol. 2004;24(12):775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Population Estimates: United States. 2016. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045216.

- 7.Slater RJ. The importance of clinical research in the care of the patient. Canadian Medical Association journal. April 14 1962;86:683–685. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, Bakai A, eds. Clinical Trials. Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, National Institutes of Health; 2012. McKinlay JBML, ed. http://www.esourceresearch.org. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell B, Kenyon S, Shakur H. Managing clinical trials. Trials. 2010;11:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]