Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA), a leading cause of disability and pain, affects 32.5 million Americans, producing tremendous economic burden. While some findings suggest that racial/ethnic minorities experience increased OA pain severity, other studies have shown conflicting results. This meta-analysis examined differences in clinical pain severity between African Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites with osteoarthritis. Articles were initially identified October 1–5, 2016, and updated May 30, 2018 using PubMed®, Web of Science™, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. Eligibility included English-language peer-reviewed articles comparing clinical pain severity in adult Black/African American and Non-Hispanic White/Caucasian patients with osteoarthritis. Non-duplicate article abstracts (N=1,194) were screened by four reviewers, 224 articles underwent full text review, and 61 articles reported effect sizes of pain severity stratified by race. Forest plots of standard mean difference showed higher pain severity in African-Americans for studies using the Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) (0.57; 95%CI: 0.54, 0.61) and non-WOMAC studies (0.35; 95%CI: 0.23, 0.47). African-Americans also showed higher self-reported disability (0.38; 95%CI: 0.22, 0.54) and poorer performance testing (−0.58; 95%CI: −0.72,−0.44). Clinical pain severity and disability in OA is higher amongst African Americans and future studies should explore the reasons for these differences to improve pain management.

Perspective

This meta-analysis shows that differences exist in clinical pain severity, functional limitations and poor performance between African Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites with osteoarthritis. This research may lead to better understanding of racial/ethnic differences in OA-related pain.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Race/Ethnicity, Pain, Disability, Meta-Analysis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) affects 32.5 million individuals and is among the leading causes of pain and disability in the United States, with annual direct (i.e., medical expenditure) and indirect (i.e., loss earnings) costs estimated at $16,000 per patient and an annual societal economic impact of $486 billion.134 OA is a significant cause of musculoskeletal pain, stiffness, swelling, and restricted range of motion 37, and adversely impacts mobility 15, activities of daily living 127, quality of life 2, and psychological functioning.54 Although any joint can develop OA, the knee, hand, and hip joints are typically affected, with the knee being the most commonly affected joint.36 In addition, older women aged ≥55 have a higher prevalence and severity of OA.132

There is considerable evidence that pain severity and disability vary considerably across people and often correlate poorly with the severity of joint changes observed radiographically.16,90 The discordance between radiographic findings and OA-related pain and disability suggests that factors other than joint pathology influence OA-related pain and disability.70 While the mechanisms underlying OA-related pain and disability remain poorly understood, OA progression can be influenced by person-level risk factors such as age, sex, obesity, genetics, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, in addition to joint-level risk factors such as injury, occupational, malalignment, and abnormal loading of the joints.6,77,92,109,111

One risk factor that appears to contribute importantly to OA-related pain and disability is racial and ethnic background.3,5,52,79,108 For instance, a greater proportion of racial/ethnic minorities, specifically African Americans (AAs), have both radiographic and symptomatic knee OA, compared to their non-Hispanic White (NHW) counterparts.39,79,108 Moreover, several studies have reported greater pain severity 5,34,52,56,113 and greater pain-related disability 22,49,113,129 among AA, compared to NHW individuals with OA. Furthermore, older AA women are disproportionately affected by functional limitations and disability from OA in comparison to other NHW women with OA 7,22,46 Longitudinal data from the 1998–2004 Health and Retirement Study, revealed that AA women with arthritis but no disability at baseline experienced disability at almost twice the rate of their NHWs counterparts over the ensuing 6-year period.126 However, other studies have found conflicting results, with some findings showing NHWs having higher incidence of hand or hip OA 38,103 and pain severity 122,139 compared to AAs, while other studies found equivalent pain severity among AA and NHW individuals with OA.11,20 In light of the conflicting evidence in the literature, it is important to better characterize racial/ethnic differences in OA-related pain.

The objectives of the current meta-analytic review were to systematically examine differences in clinical pain severity between AAs and NHWs with OA and to quantify the magnitude of these effects. A secondary aim was to examine race group differences in OA-related disability in these same studies.

Methods

Information Sources

Articles were initially identified October 1–5, 2016 using MEDLINE® (PubMed®), Web of Science™ Core Collection, PsycINFO (EBSCOhost Web), and the Cochrane Library. The search process was again repeated November 9, 2017 and May 30, 2018 to identify additional articles published since the initial literature search. Backward and forward references of key articles were investigated in Web of Science for additional studies. Major concepts of chronic pain, racial disparities, and osteoarthritis were searched in combinations of MeSH terms, PsycINFO descriptors, and truncated or phrase searched keywords in the title and abstract when permitted. The detailed search strategies employed for each data source are included in the Appendix.

Articles from data sources were selected for screening if they involved osteoarthritis, chronic pain, older adults and examined racial or ethnic differences. Candidate articles were randomly divided amongst four reviewers and screened for eligibility.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion:

Eligibility included all English-language peer-reviewed articles from clinical trials and observational studies on clinical pain severity and race. Patient populations were adults ≥ 18 years with osteoarthritis that included both Black/African-Americans and Non-Hispanic White/Caucasians patients. The use of the WOMAC (Western Ontario McMaster Osteoarthritis Index) or other standard measure such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) or Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2 (AIMS2) was required for clinical pain severity.17,99,138 Articles that reported bivariate effect sizes of clinical pain severity stratified by race were included in final qualitative synthesis. Quantitative analysis used forest plots and consisted of unique studies reporting standard mean, standard deviation and sample size.

Exclusion:

Study populations with only one racial/ethnic group were not included, nor were studies comparing other racial groups (e.g. Whites vs. Asians). Only publications reporting primary data were included; thus review articles, meta-analyses, and grey literature were excluded from the review.

Data Extraction & Measures

The primary outcome of this study was standard mean difference (SMD) of clinical pain severity between Black/African-Americans and White/Caucasians. The SMD and 95% confidence interval was calculated using Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager (RevMan v 5.3).118 The unadjusted mean pain score, standard deviation, and sample size were extracted for each article included and used to generate forest plots. Articles that had missing data were kept for qualitative synthesis, along with articles that had odds ratio, proportions or other type of effect size instead of mean pain score. The type of assessment used to evaluate pain severity was categorized as Western Ontario McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Visual Analog Scale (VAS), or Other.17,99,138

The following study characteristics were extracted during article review: name of first author, journal, title and year of publication, study design, type of osteoarthritis, and source of data or study population. To investigate additional characteristics, each article was assessed for whether pain was treated as a primary outcome or a secondary outcome, and race was treated as a primary predictor variable or a control variable. We also assessed if the study reported on disability and socioeconomic status like income, education or employment.

Data Synthesis

Studies using WOMAC to assess pain were assumed to have a fixed distribution of effect sizes. When calculating non-WOMAC studies, a random distribution was assumed since the pooled effect size reflected multiple types of pain scales. For most pain measures, higher scores indicate worse outcome or most severe pain. To permit consistent interpretation, self-reported pain scales for which higher scores reflect better outcomes were recalculated by subtracting the mean score from the maximum possible value for that scale (e.g. SF-36v2). Self-reported disability scales were treated in a similar manner and recalculated as needed. However, for performance testing measures (e.g. Short Physical Performance Battery) lower scores are indicative of worse outcome or level of functioning, and the original values were retained. Any article using a single composite scale for both pain and disability was only attributed to the pain analyses. If an article reported using a pain and/or disability subscale, then it was reported in the pain and disability forest plots, respectively.

To assess evidence of bias, RevMan 5.3 was used to generate funnel plots of the standard error by SMD. Funnel plots for pain and disability measures are in the Appendix.

Results

Study Selection

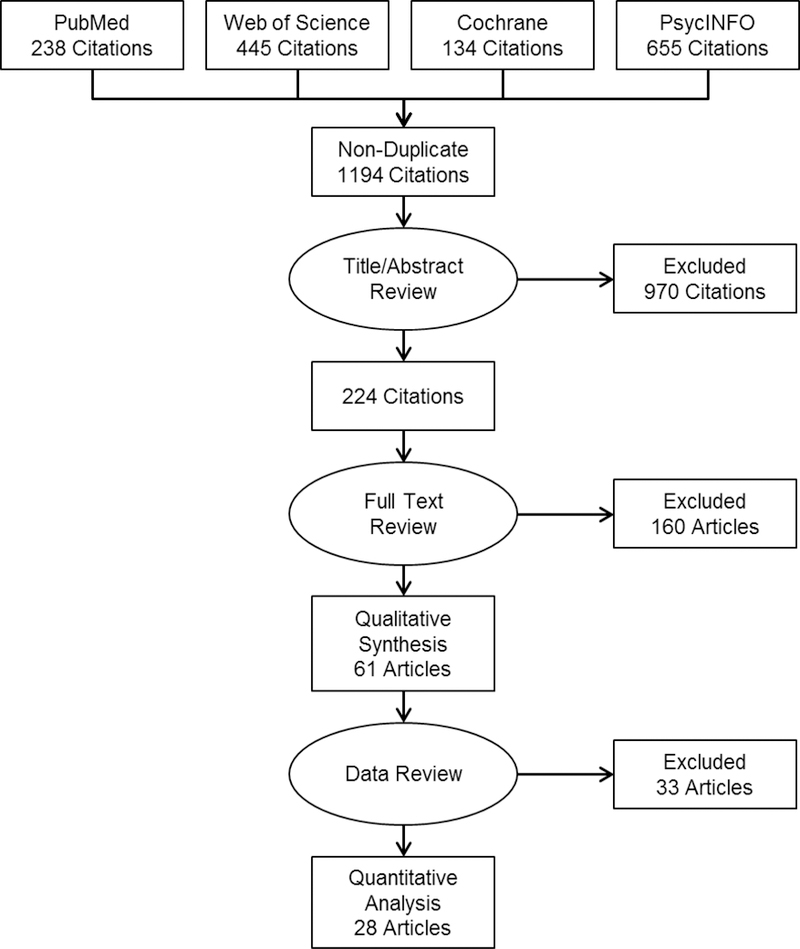

A total of 1,194 non-duplicate articles were screened and 224 articles underwent full text review (Figure 1). Of these, 61 articles reported effect sizes of pain severity stratified by race, 42 articles reported mean pain scores, and 28 unique studies were identified for quantitative analysis. No unique, eligible articles were discovered from reference lists.

Figure 1:

PRISMA Diagram

Study Characteristics

The most common clinical pain measure (N=31) was the WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index); both the pain subscale and full scale were used.17 Several articles (N=40) used other pain scales to assess pain including VAS/NRS (N=12), Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS2; N=4), Lequesne Index of Severity for Osteoarthritis (N=2), Philadelphia Geriatric Center (PGC) Pain Scale (N=2), and Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form (SF-36v2) Bodily Pain subscale (N=2).91,96,99,138 In some articles (N=9), a single pain question was utilized. Examples include: “On most days do you have pain, aching, or stiffness in your [study joint]?”; “Have you had any joint pain in your [study joint] in the last month lasting most of the month?”; “Have you had any pain in your [study joint] on most days for at least 6 weeks?”; “Do you have any chronic, recurrent, or long-lasting pain, more than aches and pains that are fleeting and minor?”. For a complete list of clinical pain measures and study characteristics, refer to Table 1.

Table 1 :

Summary of Included Articles

| Author | Journal | Year | OA Site | Dataset/ Population |

Race | Sample Size |

Parameter | Disab | SES | Pain Scale |

Forrest Plot? |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albert1 | J Cross Cult Gerontol |

2008 | Hip, Knee |

Allegheny County, PA |

Primary predictor |

B:284, W:267 |

Mean Pain Score |

No | No | VAS | Yes | B>W |

| Allen7 | Osteoarthritis Cartilage |

2009 | Hip ,knee |

JoCo OA Project | Primary predictor |

B:442, W:926 |

Mean Pain Score, Mean Difference(β) |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes | B>W* |

| Allen8 | Osteoarthritis Cartilage |

2010 | Hip, Knee |

SeMOA, Durham VAMC |

Primary predictor |

B:221, W:270 |

Mean Pain Score, Mean Difference(β) |

Yes | Yes | AIMS2 | Yes | B>W* |

| Allen5 | J Rheumatol | 2012 | Knee | JoCo OA Project | Primary predictor |

B:891, W:1857 |

Mean Difference(β) |

No | Yes | WOMAC | No | B>W* |

| Ang12 |

Med Care | 2002 | Hip, Knee |

Cleveland VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:262, W:334 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, Lequesne |

Yes† | B=W |

| Ang10 |

J Rheumatol | 2003 | Hip, Knee |

Cleveland VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:262, W:334 |

Mean Pain Score, Mean Difference(β) |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, Lequesne |

Yes | B=W |

| Ang13 |

J Rheumatol | 2009 | Hip, Knee |

Indianapolis VAMC, Wishard Hospital |

Primary predictor |

B:260, W:425 |

Proportion by pain status |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | No | B=W |

| Blanco20 | J Am Geriatr Soc |

2012 | Unspec | EAS | Primary predictor |

B:56, W:157 |

Median Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | TPI | No | B=W |

| Burns22 | J Natl Med Assoc |

2007 | Knee | FAST | Primary predictor |

B:131, W:387 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | Knee Pain Scale |

Yes | B=W |

| Cano26 | J Pain | 2006 | Unspec | Detroit Metropolitian, MI |

Primary predictor |

B:58, W:69 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | MPI | Yes | B>W* |

| Colbert31 | Artdritis Care Res (Hoboken) |

2013 | Knee | OAI | Primary predictor |

B:595, W:3100 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes | B>W* |

| Collins32 | Osteoartdritis Cartilage |

2014 | Knee | OAI | Control | B:413, W:1290 |

Prevalence by pain status (mild, mod, severe) |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | No | B>W |

| Conroy33 | Artdritis Care Res (Hoboken) |

2012 | Knee | Healtd ABC Study | Control | B:381, W:477 |

Proportion w/ radiographic OA pain |

No | No | WOMAC | No | B<W |

| Cruz-Almeida35 | Artdritis Rheumatol |

2014 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Primary predictor |

B:147, W:120 |

Mean Pain Score, Mean Difference(β) |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC,V AS, GCPS |

Yes | B>W* |

| Dillon38 | Am J Phys Med Rehabil |

2007 | Hand | NHANES III | Control | B:486, W:1379 |

Proportion w/ Symp OA |

Yes | Yes | ACR/ NHANES criteria |

No | B<W |

| Dominick42 | J Natl Med Assoc |

2004 | Unspec | Durham VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:61, W:141 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes† | B>W* |

| Eberly45 | PLos One | 2018 | Knee | UNM Ortdopaedics Clinic |

Primary predictor |

B:10, W:191 |

Mean Pain Score |

No | No | NRS | Yes | B>W |

| Flowers48 | Arthritis Res Tder |

2018 | Knee, Hip Spine |

JoCo OA Project | Primary predictor |

B:735, W:1410 |

Proportion w/ Symptoms |

No | No | Single pain question |

No | B>W |

| Gandhi51 | J Rheumatol | 2008 | Hip, Knee |

Toronto Western Hospital |

Primary predictor |

B:20, W:1488 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | WOMAC | Yes | B>W |

| Glover52 | Arthritis Rheum |

2012 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Primary predictor |

B:45, W:49 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | WOMAC | Yes† | B>W* |

| Glover53 | Clin J Pain | 2015 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Control | B:141, W:115 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | WOMAC | Yes† | B>W* |

| Golightly56 | Aging Clin Exp Res |

2005 | Hip, Knee, Back, Foot, Ankle |

Durham VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:61, W:141 |

Mean Pain Score, Mean Difference(β) |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes | B>W* |

| Golightly55 | Int J Behav Med |

2015 | Hip, Knee, Hand |

JoCo OA Project, Durham VAMC |

Control | B:59, W:94 | Mean Pain Score |

No | No | VAS | Yes | B>W* |

| Goodin58 | Health Psychol | 2013 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Primary predictor |

B:67, W:63 | Mean Pain Score |

No | Yes | WOMAC | Yes† | B>W* |

| Goodin57 | Psychosom Med |

2014 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Primary predictor |

B:122, W:103 |

Mean Pain Score |

No | Yes | VAS | Yes | B>W* |

| Groeneveld60 | Arthritis Rheum |

2008 | Hip, Knee |

Philadelphia VAMC, Pittsburg |

Primary predictor |

B:450, W:459 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, VAS |

Yes | B>W* |

| Han63 | Am J Phys Med Rehabil |

2018 | Knee | OAI | Control | B:237, W:749 |

Proportion by pain severity |

Yes | Yes | KOOS Pain |

No | B>W* |

| Hausmann66 | Race Soc Probl |

2013 | Hip, Knee |

Philadelphia VAMC, Pittsburgh VAMC |

Primary predictor |

B:127, W:303 |

Proportion by pain severity quartile |

No | Yes | WOMAC | No | B>W |

| Hausmann65 | Arthritis Care Res(Hoboken) |

2017 | Knee | VA Musculoskeletal Disorders Cohort |

Primary predictor |

B: 50,172, W:473,170 |

Proportion by pain severity |

No | No | NRS | No | B>W* |

| Herbert68 | Ann of Behav Med |

2014 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Control | B:81, W:87 | Interclass Correlation |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | No | B>W* |

| Herbert67 | Clin J Pain | 2017 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Primary predictor |

B:56, W:35 | Mean Pain Score, Mean Difference(β) |

No | Yes | VAS | Yes† | B>W* |

| Ibrahim72 | Artdritis Care Res (Hoboken) |

2001 | Hip, Knee |

Cleveland VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:260, W:332 |

Mean Pain Score |

No | Yes | WOMAC | Yes | B=W |

| Ibrahim74 | Med Care | 2002 | Hip, Knee |

Cleveland VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:262, W:334 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, Lequesne |

Yes† | B=W |

| Ibrahim73 | Arthritis Rheum |

2002 | Hip, Knee |

Cleveland VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:262, W:334 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, Lequesne |

Yes† | B=W |

| Ibrahim71 | J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci |

2003 | Hip, Knee |

Cleveland VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:135, W:165 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, VAS |

Yes† | B=W |

| Johannes76 | J Pain | 2010 | Unspec | US Households | Control | B:2073, W:21,992 |

Proportion w/ chronic pain |

No | Yes | Single pain question |

No | B<W* |

| Jones78 | J Cross Cult Gerontol |

2008 | Unspec | Philadelphia VAMC, Pittsburgh VAMC |

Primary predictor |

B:459, W:480 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes† | B>W* |

| Jordan80 | J Rheumatol | 2009 | Hip | JoCoOA Project | Control | B:999, W:2069 |

Proportion w/ Symp OA |

No | No | ACR/ NHANES criteria |

No | B>W* |

| Kwoh86 | Arthritis Res Ther |

2015 | Knee | Pittsburgh VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:285, W:514 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes | B>W* |

| Lachance87 | Osteoartdritis Cartilage |

2001 | Knee | MBHS, SWAN- Michigan Center |

Primary predictor |

B:323, W:506 |

Proportion w/ pain and OA |

No | No | Arthritis Questionn aire |

No | B>W* |

| Lavernia89 | J Artdroplasty | 2004 | Hip, Knee |

Orthopedic Institute at Mercy Hospital |

Primary predictor |

B:88, W:157 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, VAS, SF-36 |

Yes | B>W |

| Lavernia88 | Clin Ortdop Relat Res | 2010 | Hip, Knee |

Orthopedic Institute at Mercy Hospital |

Primary predictor |

B:49, W:282 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | WOMAC, SF-36 |

Yes | B>W* |

| MacFarlane95 | J Clin Rheumatol |

2018 | Knee | VITAL Trial | Primary predictor |

B:285, W:785 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes | B>W* |

| McIlvane97 | Aging Ment Healtd |

2007 | Knee, Back, Hand |

Tampa Metropolitan, FL |

Primary predictor |

B:77, W:98 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | AIMS2 | Yes† | B>W |

| Mcllvane98 | J Gerontol Psych Soc Sci |

2008 | Unspec | Tampa Metropolitan, FL |

Primary predictor |

B:77, W:98 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | AIMS2 | Yes | B>W |

| Mingo101 | J Nat Med Assoc |

2008 | Unspec | Tampa Metropolitan, FL |

Primary predictor |

B:77, W:98 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | AIMS2 | Yes† | B>W |

| Moss102 | Osteoarthrisis Cartlidge |

2016 | Hip | JoCo OA Project | Control | B:500, W:2278 |

Incidence Rate Symp OA |

No | Yes | Single pain question |

No | B<W* |

| Murphy104 | Osteoarthrisis Cartlidge |

2010 | Hip | JoCo OA Project | Control | B:496, W:2260 |

Incidence Rate Symp OA |

No | Yes | Single pain question |

No | B>W |

| Murphy106 | Arthritis Care Res |

2016 | Knee | JoCo OA Project | Primary predictor |

B:319, W:1199 |

Lifetime Risk Symp OA |

No | Yes | Single pain question |

No | B<W |

| Neuburger110 | J Public Health (Oxf) |

2012 | Hip, Knee |

PROMs; HES Database |

Control | B:995, W:107176 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | OHS, OKS | Yes | B>W* |

| Parmelee114 | J Aging Health | 2012 | Knee | Philadelphia Metropolitan, PA; Philadelphia VAMC |

Primary predictor |

B:94, W:269 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | PGC | Yes | B>W |

| Parmelee112 | Sleep Health | 2017 | Knee | Western/Central Alabama; Long Island, NY |

Primary predictor |

B:96, W:128 |

Mean Pain Score |

No | Yes | 5-point scale |

Yes | B>W* |

| Petrov115 | J Pain | 2015 | Knee | UPLOAD Study | Control | B:88, W:52 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC | Yes† | B>W |

| Siedlecki123 | Pain Manag Nurs |

2009 | Unspec | Nortdeast Ohio | Primary predictor |

B:36, W:24 | Mean Pain Score |

No | Yes | VAS, MPQ-SF |

Yes | B>W; B<W |

| Smitd125 | Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) |

2016 | Knee | Western Alabama; Long Island, NY |

Control | B:39, W:81 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | PGC | Yes | B>W* |

| Song128 | Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) |

2013 | Knee | OAI | Primary predictor |

B:286, W:1603 |

Mean Pain Score |

No | Yes | WOMAC | Yes | B>W* |

| Sowers130 | Am J Epidemiol |

2006 | Knee | MBHS, SWAN- Michigan Center |

Control | B:211, W:669 |

Proportion w/ pain |

Yes | No | Single pain question |

No | B>W* |

| Vina135 | Osteoarthrisis Cartlidge |

2018 | Knee | OAI | Primary predictor |

B:778, W:3498 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | WOMAC, NRS |

Yes | B>W* |

| Weng137 | Arthritis Rheum |

2007 | Knee | Los Angeles VAMC | Primary predictor |

B:54, W:48 | Mean Pain Score |

Yes | No | WOMAC | No | B>W* |

| Wright140 | J Musculoskelet Pain |

2015 | Neck, Should er |

JoCo OA Project | Control | B:523; W:1149 |

Proportion w/ symptoms |

Yes | No | Single pain question |

No | B<W* |

| Yang141 | BMC Complement Alt Med |

2012 | Knee | OAI | Primary predictor |

B:508, W:2075 |

Mean Pain Score |

Yes | Yes | KOOS Pain |

Yes | B>W* |

Met eligibility, but removed from final analysis due to duplicate data

Indicates statistical significance

Dataset Abbreviations:Einstein Aging Study(EAS), Fitness Arthritis in Seniors Trial(FAST), Health, Aging and Body Composition(Health ABC), Study, Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project(JoCo OA), Michigan Bone Health Study(MBHS),National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey(NHANES),National Health Service Hospital Episode Statistics(HES), database, National Health Service Patient Reported Outcome Measures Programme(PROMs), Osteoarthritis Initiative(OAI), Self-Management of OsteoArthritis in Veterans Study(SeMOA), Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation(SWAN-Michigan Center), University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Orthopaedic Clinic(UMN Orthopaedics Clnics), Understanding Pain and Limitations in Osteoarthritic Disease(UPLOAD), Study, VITamin D and OmegA-3 Trial(VITAL)

Pain Scale Abbreviations:American College of Rheumatology(ACR), Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales(AIMS2), Graded Chronic Pain Scale(GCPS), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score(KOOS), Lequesne Index of Severity for Osteoarthritis(Lequesne), McGill Pain Questionnaire Short Form(MPQ-SF), Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form(SF-36v2), Numeric Rating Scale(NRS), Oxford Hip Score(OHS), Oxford Knee Score(OKS), Philadelphia Geriatric Center Pain Scale(PGC), Sickness Impact Profile(SIP) , Total Pain Index(TPI), Visual Analog Scale(VAS), Western Ontario Macmaster University Osteoarthritis Index(WOMAC)

Among our sample, 45 articles treated race as a primary predictor, while 16 articles treated race as a control variable. Predominantly, race was a dichotomous variable of African-American/Black versus White/Caucasian; however, a few studies included additional stratification by Hispanic ethnicity (N=15) or race as a categorical variable that included Asian/Pacific Islander or Other (N=6).38,45,53,57,58,63,65,67,68,76,89,110,112,115,125,135

A large subset of articles (N=40) assessed disability or functional limitations through self-report, performance testing or a combination of modalities. Most articles measured function simultaneous with pain using the same composite scales. Function-specific assessments included WOMAC, AIMS2, Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form (SF-12) Physical Component, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function (KOOS-PF), Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) Questionnaire, Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ) and SF-36v2 Physical Function.17,18,50,61,62,69,96,99,119,136 Performance testing included timed walking, gait, stair climb, standing, and grip strength.

SES was reported in 43 articles using a combination of different measures. Education (N=41), income (N=27) and employment status (N=16) were most commonly reported as dichotomous or categorical measures. Health insurance status was reported by 4 articles; additional characteristics included geographic region and internet access.8,13,45,76,86,89,95 One study calculated the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), a scale based on zip code that incorporates a multiple SES factors previously mentioned along with environment, crime and barriers to housing and other social services.110

Synthesis of Results

The qualitative synthesis included 61 articles reporting analyses of pain stratified by race. Of these, 46 showed higher pain severity in Blacks/African Americans, but only 32 were statistically significant. Contrastingly, 7 articles reported higher pain in Whites/Caucasians, with 3 having a statistically significant difference. One article reported higher pain scores in African-Americans using the VAS and in Caucasians using the MPQ-SF.123 The remaining 9 articles concluded that there was no race group difference in pain.

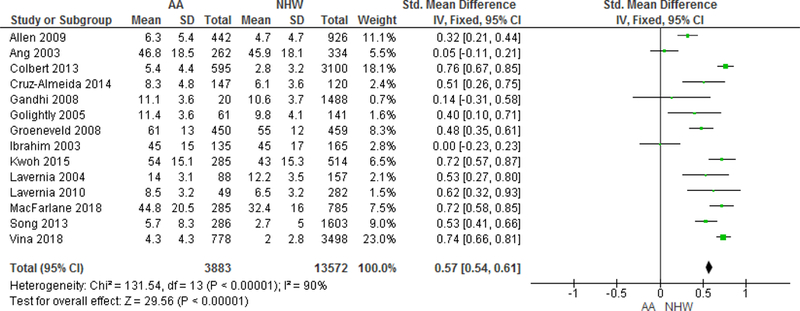

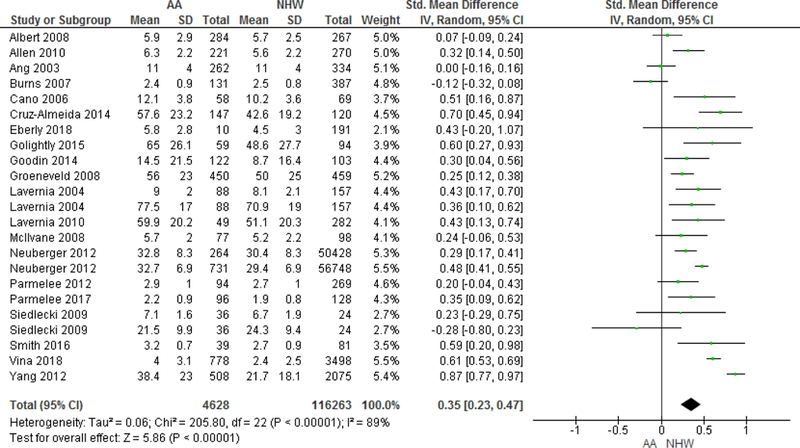

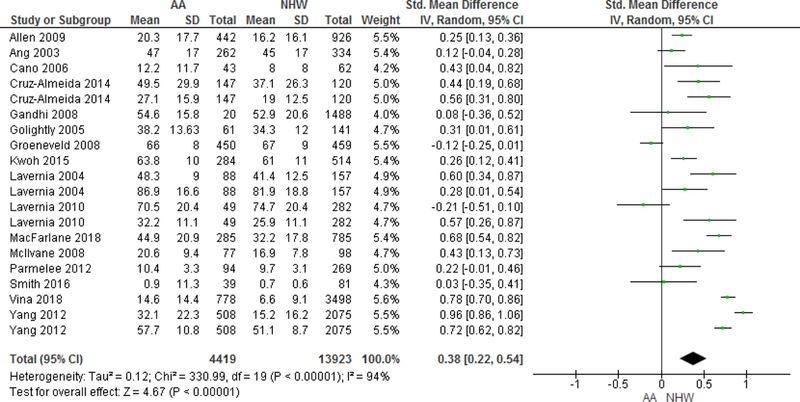

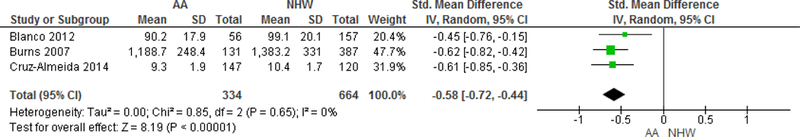

In the quantitative analysis, forest plots were created from 28 studies reporting mean pain scores. Among WOMAC studies (Figure 2), the overall standard mean difference showed higher pain severity in African-Americans with a moderate effect size (0.57; 95%CI: 0.54, 0.61). Similar results were found in non-WOMAC studies, but with a slightly lower effect size (0.35; 95%CI: 0.23, 0.47) (Figure 3). The forest plots of 21 studies from our secondary analysis of disability measures are presented in Figures 4 and 5. The findings were similar to those observed for pain measures, with African-Americans showing higher, moderate effect size for self-reported disability (0.38; 95%CI: 0.22, 0.54) and poorer performance testing (−0.58; 95%CI: −0.72,−0.44).

Figure 2:

Forest Plot of WOMAC Pain Measures Higher scores=worst outcome/most severe pain

Figure 3:

Forest Plot of Non-WOMAC Pain Measures Studies that reported using more than one pain scale are listed multiple times. Higher scores=worst outcome/most severe pain. Scales used by Lavernia 2004, 2010 (SF-36v2), Neuberger 2012 (OHS, OKS), and Yang 2012 (KOOS) are reverse coded, therefore mean scores were recalculated by subtracting from the maximum possible value for that scale.

Figure 4:

Forest Plot of Self-Reported Disability Measures Studies using WOMAC: Allen 2009; Ang 2003; Cruz-Almeida 2014; Gandhi 2008; Golightly 2005; Lavernia 2004; Lavernia 2010; MacFarlane 2018; Vina 2018. Studies using AIMS2: McIlvane 2008, Parmelee 2012; Smith 2016. Studies using SF-12 or SF-36v2: Groeneveld 2008; Kwoh 2015; Yang 2012. Other scales used include SIP: Cano 2006; GCPS: Cruz-Almeida 2014; and KOOS: Yang 2012. Studies the reported using more than one pain scale are listed multiple times. Higher scores=worst outcome/less mobility; The SF-12, SF-36v2 and KOOS are reverse coded, therefore mean scores were recalculated by subtracting from the maximum possible value for that scale.

Figure 5:

Forest Plot of Performance Testing Disability Measures Performance measures include Gait velocity: Blanco 2012; Walking test: Burns 2007; and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): Cruz-Almeida 2014. Lower scores= worst outcome/less mobility.

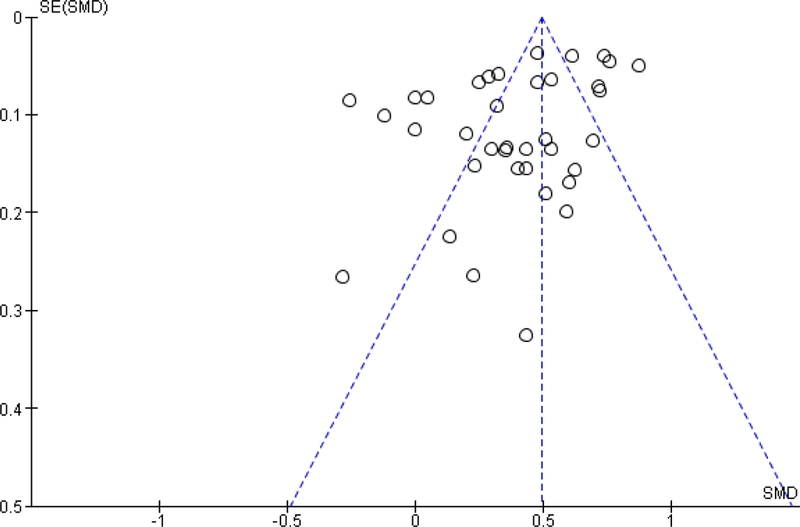

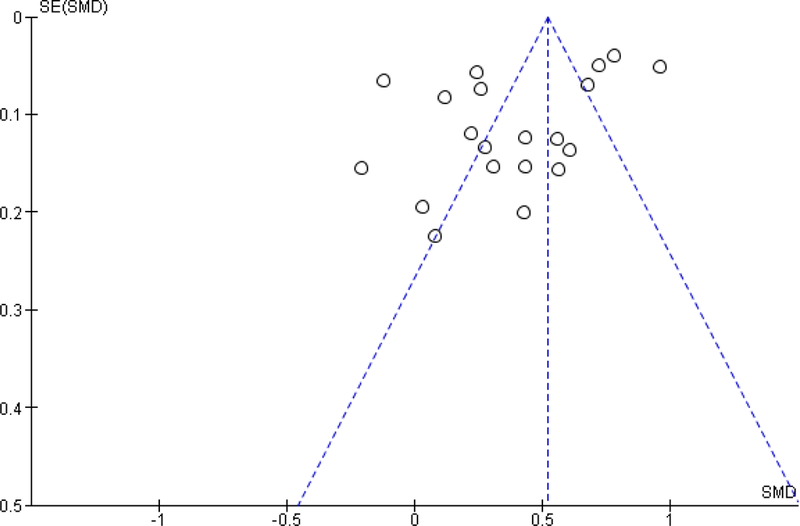

Visual inspection of funnel plots for pain and disability showed a high concentration of studies fell within the 95% CI line. Minimal horizontal scatter was present; a result of heterogeneity. Studies with larger sample sizes closer to apex had a smaller standard error; therefore, exhibited more precision. Both plots were symmetrical around the SMD; however, the absence of studies near the middle and bottom of the funnel indicate the presence of publication bias.

Discussion

The objectives of this meta-analytic review were to characterize differences in clinical pain severity and disability between AAs and NHWs with OA and to quantify the magnitude of these effects. Overall, clinical pain severity in OA was higher amongst AAs with studies using WOMAC and non-WOMAC scales. Similarly, AAs had greater self-reported disability than NHWs, greater disability in performing and doing functional tasks (e.g. timed walking test). On average, the effect sizes for the observed race differences in both pain and disability were moderate in magnitude, indicating that AAs with OA are more likely to experience significantly greater pain and disability, compared to their NHW counterparts.

Several large representative studies provide evidence that AAs are more likely to have radiographic and symptomatic OA and greater severity of knee/hip OA than NHWs.38,39,79,80,131 The current findings reveal that, in addition to differences in prevalence, AAs with OA also report greater pain and disability, and these racial/ethnic differences are moderate in magnitude. However, there was some variability in the findings across studies. Of the 61 studies included in the current meta-analysis, 75% observed higher pain severity among AAs, whereas 11% found that NHWs experienced higher pain, and 15% found no difference in pain between the races. Inconsistencies in race differences in OA-related pain may emerge due to a variety of methodological factors, including sample characteristics, measures of pain used, and analytic approach, like variables being controlled for in the analyses. Specifically, the populations from which samples are recruited (e.g. clinic vs. community, veteran vs. civilian), health status, comorbidities, and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., income, educational attainment) may differentially impact outcomes.81 For example, several studies that found no race differences in pain were based on veteran samples and enrolled patients only with moderate to severe symptoms.10,12,13,71–74 Such sampling methods may be important for achieving other study aims, but they would likely attenuate the magnitude of observed race group differences in pain. Also, the studies using the WOMAC (Figure 2) showed larger group differences than studies using other measures. However, this could reflect the influence of the affected joint, since the WOMAC is used exclusively for lower extremity OA (hip and knee) while studies in Figure 3 reflect multiple OA sites. Regarding analytic approaches, some studies have controlled for a variety of potential confounders, including radiographic measures, and SES, while others have not. Hence, the analytic approach may contribute to the inconsistent findings. Given that OA-related pain contributes to greater functional limitation and disability 75, understanding the potential mechanisms underlying racial/ethnic differences in OA is important to improve pain management.

Disparities in pain management among racial/ethnic minorities, specifically AAs have been documented.9,40 Despite higher rates of OA-related pain and disability, AAs undergo hip and knee joint replacements at lower rates than NHWs.29,44,133 Moreover, racial disparities in prescribing medications for OA have been documented.41,59,100,121 The unmet need of pain management in AA compared to NHW likely contributes to higher levels of pain and disability in this cohort.

Obesity is a risk factor that contributes to the development of OA 19,124, as well as increases the risk of radiographic progression.43,120 JoCoOA and Framingham found that obesity was independently associated with disability and compounded disability from knee pain.28,47,82 In light of higher rates of obesity in AAs than NHWs with OA, studies have investigated the extent to which racial/ethnic differences in obesity contribute to disparities in OA-related pain.7,32,53,82,104,128 Furthermore, BMI and depression were important factors in explaining racial differences in pain and physical function.7

Differences in OA disease severity and phenotype may contribute to race group differences. Some evidence suggests that genetic influence on the etiology of OA may contribute to race differences in diseases outcomes.93,142 A genome-wide association study of knee OA provided evidence for differences in the genetic architecture of knee OA between race groups.93 Racial differences in the radiographic features of knee 21, hip 107 and hand 38,131 OA have been documented in AAs which may contribute to race differences in OA severity. Specifically, AAs have more severe tibiofemoral OA, tricompartmental OA’ and lateral joint-space narrowing, as well as a higher prevalence and severity of osteophytes and higher frequency of sclerosis than NHWs. 21 Similarly, compared to NHW, AAs were more likely to have a valgus thrust during walking, which could increase the risk of lateral knee OA and were more likely to have joint space narrowing, osteophytes, and cysts compared to NHWs.27,107

Beyond differences in the OA disease process, race group differences in pain processing could contribute to greater pain severity among AAs. Indeed, considerable evidence from quantitative sensory testing (QST) in healthy adults demonstrates lower pain thresholds and tolerances, and greater experimental pain sensitivity among AAs with knee OA compared to their NHW counterparts.14,35,83,84,117

Socioeconomic status (SES) represents another important explanatory variable in understanding racial disparities in OA-related pain and disability. Lower SES is associated with poorer health outcomes and increased morbidity 116 and is a risk factor for the development and or progression of OA.94 It has been widely documented that AAs on average have a lower socioeconomic status compared to NHWs.4,23,59,64,94,116 Whether the greater OA-related pain observed in AAs is accounted for by SES has not been adequately addressed. Studies that control for SES often simultaneously adjust for other variables (e.g., BMI, age, sex); therefore, independent contribution of SES is not discernable. However, even after controlling for these characteristics, race differences in OA-related pain and disability have not been completely explained. Thus, it is well documented that low SES is an independent predictor of OA risk and confers poorer OA-related pain and disability outcomes.30,85,94,103,105 Low SES likely contributes to poorer pain outcomes via multiple mechanisms, including: 1) less access to optimal medical care, 2) increased levels of environmental and psychosocial stress, or 3) lower availability of beneficial resources such as exercise facilities, dietary nutrients, among others.94 However, the extent to which SES drives racial/ethnic differences and OA pain remains unknown. Several factors may contribute to this lack of information: 1) many researchers do not adequately control for SES, 2) researchers adjust for other variables (e.g., age, BMI, sex), so it is hard to know what SES contributes, and 3) studies operationalize SES in different ways, so it is unknown which variables are important. Stratifying analyses using a standard set of SES measures could help disentangle the complex effects of race and SES.35

Limitations

There are several limitations of this systematic review and meta-analysis. To improve the quality of data, sources were restricted to journal articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Including data from grey literature such as dissertations, and scientific proceedings, might have provided additional insight into the results and reduced publication bias. Additionally, race was classified using different terminology across studies (e.g., whites and other), and more consistent approaches to race classification are needed to ensure comparability of findings. Moreover, many studies did not report on race groups when reporting demographic characteristics of participants, which limited inclusion of studies in the meta-analysis. As previously mentioned, studies evaluated pain using a wide variety of pain scales, such that 31 studies used the WOMAC, 12 studies used VAS or NRS, and a handful of studies evaluated pain using a single question. Therefore, separate effect sizes were calculated for studies using the WOMAC and non-WOMAC pain scales. Lastly, although several studies have evaluated the impact of SES on OA, 24,25 few studies have evaluated how SES impact race differences and OA-related pain outcomes.

Conclusions

Future research should investigate the mechanisms underlying these differences, including the extent to which SES affects race differences and OA-related clinical pain severity. We provide meta-analytic evidence for higher clinical pain severity among AAs compared to NHWs with knee OA, regardless of pain scale. Similarly, AAs with knee OA reported more functional limitations and showed poorer performance on functional tasks (e.g., timed walking test) compared to NHWs with knee OA. On average, the effect sizes for the observed race group differences in both pain and disability were moderate in magnitude, indicating that AAs with OA are more likely to experience significantly greater pain and disability, compared to their NHW counterparts. The first step in successfully reducing racial disparities in pain and osteoarthritis research requires adhering to consistent definitions of racial categories, as well as, making the appropriate distinction between race and ethnicity. Such research may lead to better understanding of racial/ethnic differences in OA-related pain and inform future interventions to reduce these disparities and improve pain management.

Appendix

Figure A1:

Funnel Plot of WOMAC & Non-WOMAC Pain Measures

Figure A2:

Funnel Plot of Disability Measures

Table A1:

Detailed Search Strategy by Data Source

| Data Source | Search String |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE® (PubMed®) Filters: English |

“African Continental Ancestry Group”[MH] OR “black men”[TIAB] OR negroid[tiab] OR (negro [tiab] NOT (river OR rio)) OR blacks [TIAB] OR “black man”[TIAB] OR “black woman”[TIAB] OR “black women”[TIAB] OR “black population”[TIAB] OR “black populations”[TIAB] OR “black community”[TIAB] OR “black communities”[TIAB] OR “black patients”[TIAB] OR “black patient”[TIAB] OR “black race”[tiab] OR “black person”[tiab] OR “black persons”[tiab] OR “black people”[tiab] OR “white men”[TIAB] OR “white man”[TIAB] OR “white woman”[TIAB] OR “white women”[TIAB] OR “white population”[TIAB] OR “white populations”[TIAB] OR “white community”[TIAB] OR “white communities”[TIAB] OR “white patients”[TIAB] OR “white patient”[TIAB] OR “European Continental Ancestry Group”[Mesh] OR caucasoid [tiab] OR Caucasian* [tiab] OR Caucasians [TIAB] OR “white race”[tiab]OR “white person”[tiab] OR “white persons”[tiab] OR “white people”[tiab] OR “ethnic group” [TIAB] OR “ethnic groups” [TIAB] OR “Ethnic Groups” [MH] OR “ethnic population” [TIAB] OR “ethnic populations” [TIAB] OR Hispanic [TIAB] OR Hispanics [TIAB] OR Latino [TIAB] OR Latinos [TIAB] OR Latina [TIAB] OR Latinas [TIAB] OR “minority group” [TIAB] OR “minority groups” [MH] OR “minority groups” [TIAB] OR “minority population” [TIAB] OR “minority populations” [TIAB] OR “people of color” [TIAB] OR “ethnic minority”[tiab] OR “ethnic minorities”[tiab] OR whites [TIAB] OR “ethnic disparities” [TIAB] OR “ethnic disparity” [TIAB] OR “Minority Health” [MH] OR “minority health” [TIAB] OR “racial disparities” [TIAB] OR “racial disparity” [TIAB]OR “ethnic difference”[tiab] OR “ethnic differences”[tiab]) AND (“pain”[mesh] or pain[tiab]) AND (“Osteoarthritis”[Mesh] or osteoarth*[tiab]) |

| Web of Science™ Core Collection Language: English Document Types: Article |

#1: TS=(“minority health” OR (minority AND health) OR “minority group*” OR “ethnic group*” OR “health disparit*” OR “African American*” OR negroid OR colored OR “people of color” OR latino* OR latina* OR hispanic* OR chicano* OR chicana* OR Mexicans OR “Mexican American*” OR caucasian* OR whites OR Caucasoid) #2: TS=(pain) AND TS=(osteoarthrit*) #3: #1 and #2 |

| PsycInfo (EBSCOhost Web) Source Type: Academic Journals Language: English |

((AB osteoarth* OR TI osteoarth*) AND (( DE “Pain” OR DE “Aphagia” OR DE “Back Pain” OR DE “Chronic Pain” OR DE “Myofascial Pain” OR DE “Neuralgia” OR DE “Neuropathic Pain” OR DE “Somatoform Pain Disorder OR DE “Muscle Contraction Headache” OR DE “Trigeminal Neuralgia” ) AND ( DE “Racial and Ethnic Differences” OR DE “Health Disparities” OR DE “Latinos/Latinas” OR DE “Mexican Americans” OR DE “Blacks” OR DE “Whites” OR DE “Hispanics”) OR (AB (osteoarth* AND pain) OR TI ( osteoarth* AND pain )) AND AB (“minority health” OR (minority AND health) OR “minority group*” OR “ethnic group*” OR “health disparities” OR “African American* OR negroid OR colored OR “people of color” OR latinos OR latinas OR hispanics OR chicanos OR chicanas OR Mexicans OR “Mexican American*” OR caucasian* OR whites OR caucasoid) OR TI (“minority health” OR (minority AND health) OR “minority group*” OR “ethnic group*” OR “health disparities” OR “African American* OR negroid OR colored OR “people of color” OR latinos OR latinas OR hispanics OR chicanos OR chicanas OR Mexicans OR “Mexican American*” OR caucasian* OR whites OR caucasoid)) |

| Cochrane Library | #1: MeSH descriptor: [Osteoarthritis] explode all trees #2: MeSH descriptor: [Pain] explode all trees #3: MeSH descriptor: [Minority Groups] explode all trees #4: MeSH descriptor: [Minority Health] explode all trees #5: MeSH descriptor: [African Continental Ancestry Group] explode all trees #6: MeSH descriptor: [Ethnic Groups] explode all trees #7:“African American” or “African Americans” or “African ancestry” or black or blacks or Caucasian or Caucasians or “ethnic group” or “ethnic groups” or “ethnic population” or “ethnic populations” or Hispanic or Hispanics or Latino or Latinos or Latina or Latinas or “minority group” or “minority groups” or “minority population” or “minority populations” or “people of color” or white or whites or “ethnic disparities” or “ethnic disparity” or “minority health” or “racial disparities” or “racial disparity”:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #8: osteoarth*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #9:pain:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #10: #1 or #8 #11: #2 or #9 #12: #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 #13: #10 and #11 and #12 |

Databases searched October 1–6, 2016, November 9, 2017, and May 30, 2018

Footnotes

Disclosures: Funding for this project was provided by the National Institute on Aging (3R37AG033906-12S1, 5K07AG046371, K99AG052642, T32AG049673) and the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1K22NS102334).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Albert SM, Musa D, Kwoh K, Silverman M. Defining optimal self-management in osteoarthritis: racial differences in a population-based sample. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 23:349–360, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkan BM, Fidan F, Tosun A, Ardifoğlu Ö. Quality of life and self-reported disability in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 24:166–171, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen KD. Racial and ethnic disparities in osteoarthritis phenotypes. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 22:528–532, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen KD, Chen J-C, Callahan LF, Golightly YM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Associations of occupational tasks with knee and hip osteoarthritis: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 37:842–850, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen KD, Chen J-C, Callahan LF, Golightly YM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Jordan JM. Racial differences in knee osteoarthritis pain: potential contribution of occupational and household tasks. J Rheumatol. 39:337–344, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen KD, Golightly YM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: state of the evidence. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 27:276, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen KD, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, DeVellis RF, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Racial differences in self-reported pain and function among individuals with radiographic hip and knee osteoarthritis: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 17:1132–1136, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen KD, Oddone EZ, Coffman CJ, Keefe FJ, Lindquist JH, Bosworth HB. Racial differences in osteoarthritis pain and function: potential explanatory factors. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18:160–167, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain. 10:1187–1204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ang DC, Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Is there a difference in the perception of symptoms between african americans and whites with osteoarthritis? J Rheumatol. 30:1305–1310, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ang DC, Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Is there a difference in the perception of symptoms between african americans and whites with osteoarthritis? J Rheumatol. 30:1305–1310, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang DC, Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Siminoff LA, Kwoh CK. Ethnic differences in the perception of prayer and consideration of joint arthroplasty. Med Care. 40:471–476, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ang DC, Tahir N, Hanif H, Tong Y, Ibrahim SA. African Americans and Whites are equally appropriate to be considered for total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 36:1971–1976, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, Graven-Nielsen T. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 149:573–581, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badley EM, Wagstaff S, Wood P. Measures of functional ability (disability) in arthritis in relation to impairment of range of joint movement. Ann Rheum Dis. 43:563–569, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMCMusculoskelet Disord. 9:116, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 15:1833–1840, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 19:787–805, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan K. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18:24–33, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanco I, Verghese J, Lipton RB, Putterman C, Derby CA. Racial Differences in Gait Velocity in an Urban Elderly Cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 60:922–926, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braga L, Renner J, Schwartz T, Woodard J, Helmick C, Hochberg M, Jordan J. Differences in radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis in African-Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 17:1554–1561, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burns R, Graney MJ, Lummus AC, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J. Differences of self-reported osteoarthritis disability and race. Journal of the National Medical Association. 99:1046, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callahan LF, Cleveland RJ, Shreffler J, Schwartz TA, Schoster B, Randolph R, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Associations of educational attainment, occupation and community poverty with knee osteoarthritis in the Johnston County (North Carolina) osteoarthritis project. Arthritis Res Ther. 13:R169, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Callahan LF, Martin KR, Shreffler J, Kumar D, Schoster B, Kaufman JS, Schwartz TA. Independent and combined influence of homeownership, occupation, education, income, and community poverty on physical health in persons with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 63:643–653, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callahan LF, Shreffler J, Siaton BC, Helmick CG, Schoster B, Schwartz TA, Chen JC, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Limited educational attainment and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional analysis using data from the Johnston County (North Carolina) Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Res Ther. 12:R46, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cano A, Mayo A, Ventimiglia M. Coping, pain severity, interference, and disability: The potential mediating and moderating roles of race and education. J Pain. 7:459–468, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang A, Hochberg M, Song J, Dunlop D, Chmiel JS, Nevitt M, Hayes K, Eaton C, Bathon J, Jackson R, Kwoh CK, Sharma L. Frequency of Varus and Valgus Thrust and Factors Associated With Thrust Presence in Persons With or at Higher Risk of Developing Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 62:1403–1411, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 66:433–439, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cisternas M, Murphy L, Croft J, Helmick C. Racial disparities in total knee replacement among medicare enrollees-United States, 2000–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 58:133–138, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleveland RJ, Luong M-LN, Knight JB, Schoster B, Renner JB, Jordan JM, Callahan LF. Independent associations of socioeconomic factors with disability and pain in adults with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 14:297, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colbert CJ, Almagor O, Chmiel JS, Song J, Dunlop D, Hayes KW, Sharma L. Excess body weight and four-year function outcomes: comparison of African Americans and whites in a prospective study of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 65:5–14, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins JE, Katz JN, Dervan EE, Losina E. Trajectories and risk profiles of pain in persons with radiographic, symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 22:622–630, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conroy MB, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E, Nevitt MC, Boudreau R, Carbone LD, Chen H, Harris TB, Newman AB, Goodpaster BH. Muscle strength, mass, and quality in older men and women with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 64:15–21, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Hochberg M. Determinants of pain severity in knee osteoarthritis: effect of demographic and psychosocial variables using 3 pain measures. J Rheumatol. 26:1785–1792, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz-Almeida Y, Sibille KT, Goodin BR, Petrov ME, Bartley EJ, Riley JL 3rd, King CD, Glover TL, Sotolongo A, Herbert MS, Schmidt JK, Fessler BJ, Staud R, Redden D, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Racial and ethnic differences in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66:1800–1810, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cushnaghan J, Dieppe P. Study of 500 patients with limb joint osteoarthritis. I. Analysis by age, sex, and distribution of symptomatic joint sites. Ann Rheum Dis. 50:8–13, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet. 365:965–973, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dillon CF, Hirsch R, Rasch EK, Gu Q. Symptomatic hand osteoarthritis in the United States: prevalence and functional impairment estimates from the third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1991–1994. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 86:12–21, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, Hirsch R. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991–94. J Rheumatol. 33:2271–2279, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dominick KL, Baker TA. Racial and ethnic differences in osteoarthritis: prevalence, outcomes, and medical care. Ethn Dis. 14:558–566, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dominick KL, Bosworth HB, Dudley TK, Waters SJ, Campbell LC, Keefe FJ. Patterns of opioid analgesic prescription among patients with osteoarthritis. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 18:31–46, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dominick KL, Bosworth HB, Hsieh JB, Moser BK. Racial differences in analgesic/anti-inflammatory medication use and perceptions of efficacy. J Natl Med Assoc. 96:928–932, 2004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nguyen M, Thiesce A, Listrat V, Jacob L, Nakache J, Gabriel K, Lequesne M, Amor B. Longitudinal radiologic evaluation of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 19:378–384, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Song J, Sohn M-W, Feinglass JM, Chang HJ, Chang RW. Age and racial/ethnic disparities in arthritis-related hip and knee surgeries. Med Care. 46:200–208, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eberly L, Richter D, Comerci G, Ocksrider J, Mercer D, Mlady G, Wascher D, Schenck R. Psychosocial and demographic factors influencing pain scores of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Plos One. 13:e0195075, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elliott AL, Kraus VB, Fang F, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Salazar A, Huguenin T, Hochberg MC, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Joint-specific hand symptoms and self-reported and performance- based functional status in African-Americans and Caucasians: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Ann Rheum Dis. 66:1622–1626, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, Naimark A, Anderson JJ. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in womenThe Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 116:535–539, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flowers PPE, Cleveland RJ, Schwartz TA, Nelson AE, Kraus VB, Hillstrom HJ, Goode AP, Hannan MT, Renner JB, Jordan JM, Golightly YM. Association between general joint hypermobility and knee, hip, and lumbar spine osteoarthritis by race: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 20:76, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foy CG, Penninx BW, Shumaker SA, Messier SP, Pahor M. Long-Term Exercise Therapy Resolves Ethnic Differences in Baseline Health Status in Older Adults with Knee Osteoarthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 53:1469–1475, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 23:137–145, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gandhi R, Razak F, Davey JR, Mahomed NN. Ethnicity and patient’s perception of risk in joint replacement surgery. J Rheumatol. 35:1664–1667, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glover TL, Goodin BR, Horgas AL, Kindler LL, King CD, Sibille KT, Peloquin CA, Riley JL 3rd, ]Staud R, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB Vitamin D, race, and experimental pain sensitivity in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 64:3926–3935, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glover TL, Goodin BR, King CD, Sibille KT, Herbert MS, Sotolongo AS, Cruz-Almeida Y, Bartley EJ, Bulls HW, Horgas AL, Redden DT, Riley JL, Staud R, Fessler BJ, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. A Cross-sectional Examination of Vitamin D, Obesity, and Measures of Pain and Function in Middle-aged and Older Adults With Knee Osteoarthritis. Clin J Pain. 31:1060–1067, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldenberg DL. The interface of pain and mood disturbances in the rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 40:15–31, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golightly YM, Allen KD, Stechuchak KM, Coffman CJ, Keefe FJ. Associations of coping strategies with diary based pain variables among Caucasian and African American patients with osteoarthritis. Int J Behav Med. 22:101–108, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golightly YM, Dominick KL. Racial variations in self-reported osteoarthritis symptom severity among veterans. Aging clinical and experimental research. 17:264–269, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodin BR, Bulls HW, Herbert MS, Schmidt J, King CD, Glover TL, Sotolongo A, Sibille KT, Cruz- Almeida Y, Staud R, Fessler BJ, Redden DT, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Temporal summation of pain as a prospective predictor of clinical pain severity in adults aged 45 years and older with knee osteoarthritis: ethnic differences. Psychosom Med. 76:302–310, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodin BR, Pham QT, Glover TL, Sotolongo A, King CD, Sibille KT, Herbert MS, Cruz-Almeida Y, Sanden SH, Staud R, Redden DT, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Perceived racial discrimination, but not mistrust of medical researchers, predicts the heat pain tolerance of African Americans with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Health Psychol. 32:1117–1126, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 4:277–294, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Groeneveld PW, Kwoh CK, Mor MK, Appelt CJ, Geng M, Gutierrez JC, Wessel DS, Ibrahim SA. Racial differences in expectations of joint replacement surgery outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 59:730–737, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gummesson C, Atroshi I, Ekdahl C. The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome questionnaire: longitudinal construct validity and measuring self-rated health change after surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 4:11, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 49:M85–94, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Han A, Gellhorn AC. Trajectories of quality of life and associated risk factors in patients with knee osteoarthritis: findings from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hannan MT, Anderson JJ, Pincus T, Felson DT. Educational attainment and osteoarthritis: differential associations with radiographic changes and symptom reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 45:139–147, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hausmann LRM, Brandt CA, Carroll CM, Fenton BT, Ibrahim SA, Becker WC, Burgess DJ, Wandner LD, Bair MJ, Goulet JL. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Total Knee Arthroplasty in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System, 2001–2013. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 69:1171–1178, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hausmann LRM, Kwoh CK, Hannon MJ, Ibrahim SA. Perceived racial discrimination in health care and race differences in physician trust. Race Soc Probl. 5:113–120, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herbert MS, Goodin BR, Bulls HW, Sotolongo A, Petrov ME, Edberg JC, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Ethnicity, Cortisol, and Experimental Pain Responses Among Persons With Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis. Clin J Pain. 33:820–826, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herbert MS, Goodin BR, Pero STt, Schmidt JK, Sotolongo A, Bulls HW, Glover TL, King CD, Sibille KT, Cruz-Almeida Y, Staud R, Fessler BJ, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Pain hypervigilance is associated with greater clinical pain severity and enhanced experimental pain sensitivity among adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 48:50–60, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am J Ind Med. 29:602–608, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hunt MA, Birmingham TB, Skarakis-Doyle E, Vandervoort AA. Towards a biopsychosocial framework of osteoarthritis of the knee. Disabil Rehabil. 30:54–61, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Mercer MB, Siminoff LA, Kwoh CK. Older patients’ perceptions of quality of chronic knee or hip pain: differences by ethnicity and relationship to clinical variables. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 58:M472–477, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Variation in Perceptions of Treatment and Self-Care Practices in Elderly With Osteoarthritis: A Comparison Between African American and White Patients. Arthritis Rheum. 45:340–345, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Differences in expectations of outcome mediate African American/white patient differences in “willingness” to consider joint replacement. Arthritis Rheum. 46:2429–2435, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Understanding ethnic differences in the utilization of joint replacement for osteoarthritis: the role of patient-level factors. Med Care. 40:I44–51, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P. Osteoarthritis as a public health problem: the impact of developing knee pain on physical function in adults living in the community: (KNEST 3). Rheumatology. 46:877–881, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in united states adults: Results of an internet-based survey. J Pain. 11:1230–1239, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 28:5–15, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jones AC, Kwoh CK, Groeneveld PW, Mor M, Geng M, Ibrahim SA. Investigating racial differences in coping with chronic osteoarthritis pain. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 23:339–347, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, Fang F, Schwartz TA, Abbate LM, Callahan LF. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 34:172–180, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, Fang F, Schwartz TA, Nelson AE, Abbate LM. Prevalence of hip symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 36:809–815, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jordan JM, Linder GF, Renner JB, Fryer JG. The impact of arthritis in rural populations. Arthritis Care Res. 8:242–250, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jordan JM, Luta G, Renner JB, Linder GF, Dragomir A, Hochberg MC, Fryer JG. Self-reported functional status in osteoarthritis of the knee in a rural southern community: the role of sociodemographic factors, obesity, and knee pain. Arthritis Care Res. 9:273–278, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim HJ, Yang GS, Greenspan JD, Downton KD, Griffith KA, Renn CL, Johantgen M, Dorsey SG. Racial and ethnic differences in experimental pain sensitivity: systematic review and metaanalysis. Pain. 158:194–211, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.King CD, Sibille KT, Goodin BR, Cruz-Almeida Y, Glover TL, Bartley E, Riley JL, Herbert MS, Sotolongo A, Schmidt J, Fessler BJ, Redden DT, Staud R, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Experimental pain sensitivity differs as a function of clinical pain severity in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 21:1243–1252, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Knight JB, Callahan LF, Luong M-LN, Shreffler J, Schoster B, Renner JB, Jordan JM. The association of disability and pain with individual and community socioeconomic status in people with hip osteoarthritis. Open Rheumatol J. 5:51, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kwoh CK, Vina ER, Cloonan YK, Hannon MJ, Boudreau RM, Ibrahim SA. Determinants of patient preferences for total knee replacement: African-Americans and whites. Arthritis Res Ther. 17:348, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lachance L, Sowers M, Jamadar D, Jannausch M, Hochberg M, Crutchfield M. The experience of pain and emergent osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 9:527–532, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lavernia CJ, Alcerro JC, Rossi MD. Fear in arthroplasty surgery: the role of race. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 468:547–554, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lavernia CJ, Lee D, Sierra RJ, Gomez-Marin O. Race, ethnicity, insurance coverage, and preoperative status of hip and knee surgical patients. J Arthroplasty. 19:978–985, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lawrence J, Bremner J, Bier F. Osteo-arthrosis. Prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis. 25:1, 1966 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lequesne MG, Mery C, Samson M, Gerard P. Indexes of severity for osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Validation--value in comparison with other assessment tests. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 65:85–89, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 105:185–199, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu Y, Yau MS, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Duggan DJ, Renner JB, Hochberg MC, Mitchell BD, Jackson RD, Jordan JM. Genetic Determinants of Radiographic Knee Osteoarthritis in African Americans. J Rheumatol. 44:1652–1658, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Luong ML, Cleveland RJ, Nyrop KA, Callahan LF. Social determinants and osteoarthritis outcomes. Aging health. 8:413–437, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.MacFarlane LA, Kim E, Cook NR, Lee IM, Iversen MD, Katz JN, Costenbader KH. Racial Variation in Total Knee Replacement in a Diverse Nationwide Clinical Trial. J Clin Rheumatol. 24:1–5, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr., Raczek AE The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 31:247–263, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McIlvane JM. Disentangling the effects of race and SES on arthritis-related symptoms, coping, and well-being in African American and White women. Aging Ment Health. 11:556–569, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McIlvane JM, Baker TA, Mingo CA. Racial differences in arthritis-related stress, chronic life stress, and depressive symptoms among women with arthritis: A contextual perspective. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 63:S320–S327, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Guccione AA, Kazis LE. AIMS2. The content and properties of a revised and expanded Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Health Status Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 35:1–10, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meghani SH. Corporatization of pain medicine: implications for widening pain care disparities. Pain Med. 12:634–644, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mingo CA, McIlvane JM, Baker TA. Explaining the relationship between pain and depressive symptoms in African-American and white women with arthritis. J Natl Med Assoc. 100:996–1003, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Moss AS, Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Barbour KE, Renner JB, Kalsbeek W, Jordan JM. Annual incidence rates of hip symptoms and three hip OA outcomes from a U.S. population-based cohort study: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 24:1518–1527, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moss AS, Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Barbour KE, Renner JB, Kalsbeek W, Jordan JM. Annual incidence rates of hip symptoms and three hip OA outcomes from a US population-based cohort study: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 24:1518–1527, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Renner JB, Tudor G, Koch GG, Dragomir AD, Kalsbeek WD, Luta G, Jordan JM. One in four people may develop symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in his or her lifetime. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18:1372–1379, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Murphy LB, Moss S, Do BT, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Barbour KE, Renner J, Kalsbeek W, Jordan JM. Annual incidence of knee symptoms and four knee osteoarthritis outcomes in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care & Research. 68:55–65, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Murphy LB, Moss S, Do BT, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, Barbour KE, Renner J, Kalsbeek W, Jordan JM. Annual Incidence of Knee Symptoms and Four Knee Osteoarthritis Outcomes in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 68:55–65, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nelson AE, Braga L, Renner JB, Atashili J, Woodard J, Hochberg MC, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Characterization of individual radiographic features of hip osteoarthritis in African American and White women and men: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 62:190–197, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nelson AE, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Kraus VB, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Differences in multijoint radiographic osteoarthritis phenotypes among African Americans and Caucasians: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis project. Arthritis Rheum. 63:3843–3852, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Neogi T, Zhang Y. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 39:1, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Neuburger J, Hutchings A, Allwood D, Black N, van der Meulen JH. Sociodemographic differences in the severity and duration of disease amongst patients undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery. J Public Health (Oxf). 34:421–429, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Palazzo C, Nguyen C, Lefevre-Colau M-M, Rannou F, Poiraudeau S. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 59:134–138, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Parmelee PA, Cox BS, DeCaro JA, Keefe FJ, Smith DM. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep quality among older adults with osteoarthritis. Sleep Health. 3:163–169, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Parmelee PA, Harralson TL, McPherron JA, DeCoster J, Schumacher HR. Pain, disability, and depression in osteoarthritis: effects of race and sex. Journal of aging and health. 24:168–187, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Parmelee PA, Harralson TL, McPherron JA, DeCoster J, Schumacher HR. Pain, disability, and depression in osteoarthritis: effects of race and sex. J Aging Health. 24:168–187, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Petrov ME, Goodin BR, Cruz-Almeida Y, King C, Glover TL, Bulls HW, Herbert M, Sibille KT, Bartley EJ, Fessler BJ, Sotolongo A, Staud R, Redden D, Fillingim RB, Bradley LA. Disrupted sleep is associated with altered pain processing by sex and ethnicity in knee osteoarthritis. J Pain. 16:478–490, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Poleshuck EL, Green CR. Socioeconomic disadvantage and pain. Pain. 136:235, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL 3rd, Williams AK, Fillingim RB. A quantitative review of ethnic group differences in experimental pain response: do biology, psychology, and culture matter? Pain Med. 13:522–540, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Review. Review Manager (RevMan). Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)--development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 28:88–96, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schouten J, Van den Ouweland F, Valkenburg H. A 12 year follow up study in the general population on prognostic factors of cartilage loss in osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis. 51:932–937, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB. Race, ethnicity, and pain among the U.S. adult population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 21:177–220, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Siedlecki SL. Racial variation in response to music in a sample of African-American and Caucasian chronic pain patients. Pain Management Nursing. 10:14–21, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Siedlecki SL. Racial Variation in Response to Music in a Sample of African-American and Caucasian Chronic Pain Patients. Pain Manag Nurs. 10:14–21, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Silverwood V, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan J, Protheroe J, Jordan K. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 23:507–515, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Smith DM, Parmelee PA . Within-Day Variability of Fatigue and Pain Among African Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites With Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 68:115–122, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Song J, Chang HJ, Tirodkar M, Chang RW, Manheim LM, Dunlop DD. Racial/ethnic differences in activities of daily living disability in older adults with arthritis: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheum. 57:1058–1066, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Song J, Chang RW, Dunlop DD. Population impact of arthritis on disability in older adults. Arthritis Rheum. 55:248–255, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Song J, Hochberg MC, Chang RW, Hootman JM, Manheim LM, Lee J, Semanik PA, Sharma L, Dunlop DD. Racial and ethnic differences in physical activity guidelines attainment among people at high risk of or having knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 65:195–202, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sowers M, Jannausch ML, Gross M, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Palmieri RM, Crutchfield M, Richards-McCullough K. Performance-based physical functioning in African-American and Caucasian women at midlife: considering body composition, quadriceps strength, and knee osteoarthritis. American journal of epidemiology. 163:950–958, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sowers M, Jannausch ML, Gross M, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Palmieri RM, Crutchfield M, Richards-McCullough K. Performance-based physical functioning in African-American and Caucasian women at midlife: considering body composition, quadriceps strength, and knee osteoarthritis. Am J Epidemiol. 163:950–958, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sowers M, Lachance L, Hochberg M, Jamadar D. Radiographically defined osteoarthritis of the hand and knee in young and middle-aged African American and Caucasian women. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 8:69–77, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, Winzenberg TM, Hosmer D, Jones G. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 13:769–781, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]