Abstract

Objectives:

The current study examined race and gender effects on initial levels and trajectories of self-reported physical and mental health, as well as the potential moderating role of personality. We hypothesized that health disparities would remain stable or decrease over time, and that at-risk personality traits (e.g., high neuroticism) would have a more robust negative impact on health for Black participants.

Methods:

Analyses utilized six waves of data from a community sample of 1,577 Black and White adults (mean age 60), assessed every 6 months for 2.5 years. Using multigroup latent growth curve modeling, we examined initial levels and changes in health among White men (n=482), White women (n=578), Black men (n=226), and Black women (n=291).

Results:

Black participants reported lower initial physical health than White participants; women’s physical health was stable over time whereas men’s declined. There were no disparities in self-reported mental health. Higher agreeableness was associated with higher initial levels of physical health only among Black men and White women. All other personality traits were associated with physical and mental health similarly across race and gender.

Conclusions:

Race and gender influence health trajectories. Personality-health associations largely replicated across race and gender, though some associations differed across groups. Results suggest that an intersectional framework considering more than one aspect of social identity is crucial to understanding health disparities. Future studies may benefit from including large, diverse samples of participants and further examining the moderating effects of race and gender on personality associations with a variety of health outcomes.

Keywords: health disparities, health trajectories, personality, race, gender

Disparities in health between Black and White Americans are pervasive across a range of health outcomes and throughout the lifespan (Dressler, Oths, & Gravlee, 2005). Compared with White adults, Black adults have higher mortality rates from several leading causes of death (e.g., heart disease, certain cancers, diabetes), and experience earlier illness onset, greater severity of illness, poorer perceptions of health, worse physical functioning, and steeper increases in chronic illness onset over time (Brown, O’Rand, & Adkins, 2012; Cunningham et al., 2017; Kochanek, Arias, & Anderson, 2013; Warner & Brown, 2011). Based on national epidemiological studies, Black individuals are found to be equally or less likely to suffer from major mental disorders, but tend to report greater chronicity and severity of illness and a higher burden of unmet mental health needs (SAMHSA, 2015; Ault-Brutus, 2012; Hahm, Cook, Ault-Brutus, & Alegría, 2015; Wang et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2007). Despite organized efforts to understand Black-White health disparities and achieve health equity, these disparities remain inadequately understood and pressing public health concerns (Dressler et al., 2005; Williams & Mohammed, 2010).

Research to date has focused heavily on understanding the contributions of socioeconomic factors and health behaviors (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use) to racial disparities in health. This research shows that in many instances, these factors do not fully explain disparities (Lillie-Blanton, Parsons, Gayle, & Dievler, 1996; Richardson & Brown, 2016; Warner & Brown, 2011). Other factors that may contribute to health disparities may arise from the unique experiences of marginalized groups in the United States, which shape access to health-promoting resources and exposure to health risk factors (Brown et al., 2012). An intersectional approach suggests that multiple social identities, such as race and gender, mutually influence an individual’s health via access and exposure.

The intersection of race and gender may influence health through their impact on the associations among health risk factors and health outcomes. Personality traits are constructs that are robustly associated with health outcomes (Weston, Hill, & Jackson, 2015), but have been understudied in relation to health disparities (Chapman, Roberts, & Duberstein, 2011). Personality traits may be conceptualized as psychosocial resources that advantage or disadvantage health, and may interact with or intervene in the associations among race and health outcomes. The current study examines race and gender effects on initial levels and trajectories of self-reported physical health and mental health, as well as the potential moderating effects of personality traits, in a community sample of older Black and White adults.

Disparities in health trajectories

It is important to study the progression of health disparities during middle age and beyond, as this is when the lifetime accumulation of health risk factors most markedly results in health problems (Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, & Bound, 2006). The relative impact of health-related risk factors and resources among demographic groups may shift and change as individuals age, influencing the nature of health disparities over the life span. To date, studies of racial disparities in health trajectories during middle age have examined whether disparities remain stable (persistent inequality), grow narrower (aging-as-leveler), or grow wider (cumulative disadvantage) over time (Brown et al., 2012; Kim & Miech, 2009; Shuey & Willson, 2008; Warner & Brown, 2011).

The persistent disadvantage hypothesis posits that social determinants and resources have relatively invariant socially-patterned impacts on health throughout the life span, leading to stable disparities over time (Ferraro & Farmer, 1996). The aging-as-leveler hypothesis postulates that health disparities will decline as individuals age, possibly through the more even distribution of health-promoting resources (e.g., Medicare and social security), or the leveling effects of aging on biological vulnerability to disease (House et al., 1994; Kim & Miech, 2009). Conversely, the cumulative disadvantage hypothesis posits that disparities increase over time, indicating an accumulation of disparities in health-promoting resources over the life span (Kim & Miech, 2009).

Research suggests that by the time they reach mid-life, women and Black adults experience more physical health problems than men and Whites (Brown et al., 2012; Kim & Miech, 2009; Richardson & Brown, 2016; Rohlfsen & Kronenfeld, 2014; Warner & Brown, 2011). During early mid-life (mid-40’s to early 60’s), evidence suggests that some health outcomes (i.e., physical functioning and serious illness onset) follow a cumulative disadvantage trajectory, as health declines more rapidly for Black than for White participants. Then, during late mid-life (late 50’s/early 60’s and beyond), the magnitude of these disparities either remains constant, following a persistent inequality trajectory, or converges, following an aging-as-leveler trajectory (Brown et al., 2012; Brown, Richardson, Hargrove, & Thomas, 2016; Kim & Miech, 2009; Warner & Brown, 2011).

Research examining gender differences in health trajectories among American mid-life adults suggest that women have poorer initial physical functioning than men, a disparity which follows a persistent inequality trajectory (Rohlfsen & Kronenfeld, 2014; Warner & Brown, 2011). Some studies find a combined effect of gender and race such that being Black and female is associated with worse initial health than either alone, and Black women experience a distinct pattern of health change over time compared with other racial/ethnic groups (Richardson & Brown, 2016; Warner & Brown, 2011).

Research on race/gender differences in mental health trajectories is limited. One study found that, following traumatic brain injury, elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among Black as compared with White participants followed a persistent inequality pattern over two years (Perrin et al., 2015). Other cross-sectional research suggests that compared with White adults, Black adults have similar or lower rates of most mental disorders and greater levels of psychological flourishing (Gibbs et al., 2013; Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Himle, Baser, Taylor, Campbell, & Jackson, 2009; Keyes, 2009; Williams et al., 2007), but greater chronicity and severity of mental illness (Himle et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2007).

Personality Traits and Health Disparities

Personality traits are psychosocial constructs that represent a collection of relatively stable and global traits that influence thoughts, feelings and behaviors (Chapman et al., 2011). In personality and health research, personality traits are frequently defined in terms of the five-factor model (FFM). The FFM includes five major domains of personality (i.e., Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness) (Costa Jr. & McCrae, 1992; Ferguson, 2013). Neuroticism is the tendency to experience negative emotions; Extraversion is the tendency to seek stimulation and engage socially; Openness is the tendency to prefer a variety of experiences and ideas; Agreeableness is the tendency to be trusting and cooperative; and Conscientiousness is the tendency to be thoughtful and goal-directed.

Personality traits predict a range of health outcomes, including subjective mental and physical health, illness onset, mortality, physical functioning, health care utilization, and health trajectories. In general, higher levels of neuroticism, and lower levels of conscientiousness, extraversion, openness and agreeableness are associated with poorer physical and mental health outcomes (Ferguson, 2013; Hampson, 2012; Iacovino, Bogdan, & Oltmanns, 2016; Jackson, Weston & Schultz, 2017; Lamers, Westerhof, Kovács, & Bohlmeijer, 2012; Letzring, Edmonds, & Hampson, 2014; Löckenhoff, Sutin, Ferrucci, & Costa, 2008; Magee, Heaven, & Miller, 2013; Turiano et al., 2012; Weston et al., 2015).

The social context of exclusion and marginalization that is associated with having a marginalized identity may influence the nature of personality-health associations (Chapman, Fiscella, Kawachi, & Duberstein, 2010; Chapman et al., 2011; Elliot, Turiano, & Chapman, 2016; Jonassaint & Siegler, 2011). In other words, race and gender may exacerbate or attenuate (i.e., moderate) the impact of personality traits on health. To date, few studies have examined this question. This is a crucial step as personality and health researchers begin to consider the role of personality traits in personalizing medicine (Israel et al., 2014).

This approach to examining the replicability of personality-health associations across demographic groups can be summarized via the selective vulnerability hypothesis, which posits that social disadvantage has a more robust negative impact on health among individuals with personality traits that are associated with poorer health outcomes (Chapman et al., 2011). Stated differently, having a marginalized social identity may accentuate the impact of “at-risk” personality traits, such as neuroticism, on health. Conversely, personality traits found to be associated with better health, such as conscientiousness, may have a less positive impact on health among those with marginalized identities, also contributing to health disparities.

Mechanistically, personality traits that are associated with poorer health outcomes may increase the occurrence of stressors or may enhance stress reactivity among individuals from disadvantaged social groups, whom already experience a higher stress burden, more intensely than among those from dominant social groups. This may lead to greater biological and psychological wear and tear, leading to adaptations over time that cause poorer health outcomes (e.g., the allostatic load process for physical health) (McEwen, 1998; Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011).

Though there is limited research on the selective vulnerability hypothesis, some findings support it. An epidemiological longitudinal study conducted with adults ages 25 to 64 at baseline found that negative affect, which the authors assessed as a symptom-based measure related to neuroticism (i.e., depression and anxiety symptoms), had a more robustly detrimental impact on subjective and objective measures of hypertension in Black as compared to White participants, both cross-sectionally and over a follow-up period lasting up to 22 years (Jonas & Lando, 2000). Studies of FFM personality traits in this arena are rare. One cross-sectional study found that lower extraversion was associated with higher inflammation, which is associated with a range of chronic illnesses, more robustly among minority women as compared with White women (Chapman, Khan, & Harper, 2009). Another cross-sectional study focused on socioeconomic health disparities found that socioeconomic status (SES) was more strongly associated with higher inflammation at higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of conscientiousness (Elliot et al., 2016). There is also some support for the selective vulnerability hypothesis for mental health; one cross-sectional study found that higher neuroticism had a more detrimental impact on mental health functioning in Black as compared with White older adults undergoing cancer treatment (Krok-Schoen & Baker, 2014).

Current Study

Extensive research linking personality and health, and race and health, as well as the small amount of research on personality and health disparities suggests that further research is warranted. The current study examines two research questions: (1) Are there race and gender effects on initial levels and trajectories of health during late mid-life? (2) Are there race and gender differences in the magnitude of personality-health associations? We investigate these questions in regard to self-reported physical and mental health over 2.5 years in a longitudinal community sample of late mid-life adults (aged 55-64 at wave 1).

We hypothesize that Black participants will report lower initial levels of physical and mental health than White participants, and that the magnitude of disparities will remain stable over time, following the persistent inequality pattern. Furthermore, we hypothesize that Black women will show significantly lower levels of physical health than all other groups. It is difficult to make hypotheses about the moderating effects of personality on health disparities given the lack of research in this area. However, we explored the selective vulnerability hypothesis by examining whether at-risk personality traits (e.g., higher neuroticism, lower extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness and openness) were more strongly associated with lower initial levels of health and greater declines in health among Black as compared with White participants, and whether the intersection of race and gender further influenced personality-health associations.

We assess personality using both self and informant reports. Informant reports of personality are being increasingly used in health psychology research because they independently predict a range of health outcomes, thus enhancing the robustness and meaningfulness of conclusions (Huprich, Bornstein, & Schmitt, 2011; Jackson, Connolly, Garrison, Leveille, & Connolly, 2015). We examine disparities by race and gender groups (i.e., Black women, Black men, White women, and White men), in order to consider the combined influence of these social identities on health. Race and gender shape access to resources and life experiences, both independently and through mutually reinforcing one another, thus jointly impacting health (Warner & Brown, 2011). Considering both simultaneously is important to accurately characterize the nature of health disparities.

Method

Participants

Black (n=517) and White (n=1060) participants taking part in the ongoing longitudinal St. Louis Personality and Aging Network (SPAN) study were included in the current analyses (Oltmanns, Rodrigues, Weinstein, & Gleason, 2014). Exclusion criteria included lacking a permanent residence, a lower than 6th grade reading level, and active psychotic symptoms at the time of the wave 1 assessment. These exclusion criteria were chosen so that participants could read the questionnaires and would be less likely to be lost to follow-up. The total attrition rate (i.e., those who were no longer enrolled in the study by wave 6) for Black (8.4%) and White (6.6%) participants over the first six waves of the study did not differ significantly (χ2=1.76; p=.19). Demographic characteristics and descriptive statistics for all variables by race and gender are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, Health Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Men n (%) | Black Women n (%) | White Men n (%) | White Women n (%) | |

| Annual Household Income | ||||

| Under $20,000 | 42 (19.8) | 66 (23.4) | 35 (7.5) | 41 (7.5) |

| $20,000 – $39,999 | 50 (23.6) | 89 (31.6) | 46 (9.8) | 99 (18.0) |

| $40,000 - $59,999 | 42 (19.8) | 76 (27.0) | 72 (15.4) | 138 (25.0) |

| $60,000 – $79,999 | 33 (15.6) | 24 (8.5) | 65 (13.9) | 81 (14.7) |

| $80,000 – $99,999 | 16 (7.5) | 17 (6.0) | 62 (13.2) | 61 (11.1) |

| Above $100,000 | 29 (13.7) | 10 (3.5) | 188 (40.2) | 130 (23.6) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 8 (3.6) | 10 (3.5) | 3 (.6) | 6 (1.0) |

| High school diploma or GED | 52 (23.3) | 61 (21.3) | 40 (8.3) | 62 (10.8) |

| Post-secondary education | 76 (34.1) | 102 (35.5) | 80 (16.6) | 112 (19.4) |

| College degree | 67 (30.0) | 80 (27.9) | 168 (34.9) | 217 (37.7) |

| Graduate degree | 20 (9.0) | 34 (11.8) | 190 (39.5) | 179 (31.1) |

| Descriptive Statistics for Wave 1 Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Men M (SD) | Black Women M (SD) | White Men M (SD) | White Women M (SD) | |

| Age | 60.1 (2.8)a | 60.0 (2.7)a | 60.0 (2.8)a | 60.2 (2.8)a |

| Self-reported Physical Health | 51.3 (12.3)b | 50.8 (12.7)b | 58.1 (9.4)a | 56.6 (10.4)a |

| Self-reported Mental Health | 57.0 (13.9)b | 56.2 (13.3)b | 59.9 (11.4)a | 58.2 (12.7)a,b |

| Neuroticism | 71.0 (16.0)a | 73.0 (17.9)a | 73.2 (20.7)a | 77.8 (21.3)b |

| Extraversion | 107.9 (15.0)a,b | 110.3 (14.9)b | 106.1 (18.9)a | 110.5 (18.2)b |

| Openness | 103.3 (12.9)c | 105.0 (13.4)c | 108.9 (18.3)a | 113.2 (17.1)b |

| Agreeableness | 121.8 (16.9)a | 128.1 (14.7)c | 123.1 (16.7)a | 131.8 (14.8)b |

| Conscientiousness | 125.1 (15.9)a,b | 128.0 (16.0)b | 123.7 (19.6)a | 124.8 (19.4)a,b |

Different superscripts denote significant differences after bonferroni correction.

Group differences tested with pairwise independent samples t-test.

Procedure

Participants were recruited using listed phone numbers that were crossed with current census data in order to identify households with at least one member in the eligible age range (see Oltmanns et al., 2014 for a detailed explanation of recruiting methods). An over-sampling procedure was employed during recruitment to increase representation of Black men. During the first few months of the study, 31% of Black participants were males, compared with 46% of White participants. To increase the number of Black male participants, we mailed modified letters to homes located in predominantly Black zip codes and for which the phone number was listed under a man’s name (see Spence & Oltmanns, 2011). At the end of baseline recruitment, men comprised 43% of the Black sample.

Data from the first six waves of data collection are included in current analyses. Each participant completed two 3-hour in person assessments, one at baseline (wave 1) and one approximately 2.5 years later (wave 6), as well as a shorter sequence of mailed self-report questionnaires every 6 months (waves 2 – 5) in between the two major assessments. A demographics questionnaire administered at wave 1 assessed self-reported race, annual household income, and education. Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to the wave 1 assessment. Each participant received $60 compensation to complete each 3-hour assessment and $20 to complete each follow-up assessment packet. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Participation at each wave was as follows: wave 2 n=l,434; wave 3 n=l,380; wave 4 n=l,329; wave 5 n=l,250; wave 6 n=l,260.1 Approximately 20% of participants (n=263) experienced a delay in completion of the wave 6 assessment because of a temporary lapse in funding for the project. This subset completed wave 6 more than 2.5 years after wave 1 (range: 3.5 - 6.7 years). In order to control for the effects of the timing of wave 6 completion, a variable representing the time at which participants completed this wave (i.e., ≤2.5 years or >2.5 years) was included as a predictor in all models that included wave 6 data.

The majority of participants (88%) chose at least one person who knew them best to provide data about the participant’s personality. Ninety-six percent of White participants and 95% of Black participants matched their informant in race. Participants had known their informants for an average of 30 years. The majority of White participants’ informants were significant others (55.1%), and the majority of Black participants’ informants were family members (42.5%). Black and White participants knew their informants equally well. Informants were compensated $30 for the wave 1 assessment and $10 for subsequent assessments.

Personality

Personality was measured at wave 1 using the NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO PI-R; Costa Jr. & McCrae, 1992). The NEO-PI-R is a widely used 240-item assessment of five personality domains: Neuroticism (e.g., “I often worry about things that might go wrong”), Extraversion (e.g., “I am a warm and friendly person”), Openness (e.g., “I am intrigued by the patterns I find in art and nature”), Agreeableness (e.g., “I think most of the people I deal with are honest and trustworthy”), and Conscientiousness (e.g., “I am a productive person who always gets the job done”). Each domain is made up of six facets. NEO-PI-R items are rated on a 5-point scale, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Adequate reliability and validity have been shown for both clinical and community samples, including for older Black American adults (Savla, Davey, Costa, & Whitfield, 2007). Participants and informants completed the NEO-PI-R about participants. The Cronbach reliabilities of the NEO domains in this sample ranged from .86 to .92, with similar reliabilities across race and gender groups. The five personality domains were calculated as an average of the participant and informant scales.

Health

Self-reported health.

The RAND Short Form 36 Health Status Inventory (HSI; Hays & Morales, 2001) is a self-report questionnaire that was used to measure health-related quality of life within physical and emotional health spheres. The Cronbach reliabilities of the wave 1 physical health scale for this sample ranged from .75 to .92, and for mental health ranged from .79 to .87, with similar reliabilities across race and gender, and across waves.

The physical health scales assess four aspects of health over the previous 4 weeks. Physical Functioning items ask participants to rate how much their health has limited their functioning in daily activities (e.g., “Does your health now limit you in bending, kneeling or stooping? How much?”). Role Limitations Due to Physical Health Problems items measure whether or not physical problems have limited work or other regular daily activities (e.g., “During the past 4 weeks, have you accomplished less than you would like as a result of your physical health?”). General Health Perceptions items include questions about self-rated health (ranging from “poor” to “excellent”) and general health (e.g., “I seem to get sick easier than other people”). Pain items ask participants to rate the amount of bodily pain experienced, as well as how much this pain interfered with work and activities (e.g., “How much does pain interfere with your normal work?”).

The mental health scales also span 4 weeks. Role limitations due to emotional problems assess the extent to which emotional problems have limited work or other activities (e.g., “During the past 4 weeks, have you accomplished less than you would like as a result of emotional problems?”). Social functioning assesses the extent to which emotional problems interfered with social activities (e.g., “To what extent have your emotional problems interfered in your normal activities with family, friends, neighbors or groups?”). Emotional well-being assesses emotional state (e.g., “How much time during the past 4 weeks have you felt downhearted or blue?”). Energy/fatigue assesses the extent to which participants felt energetic and tired (e.g., “How much time during the past 4 weeks did you feel worn out?”). Self-reported physical health and self-reported mental health were each calculated as an average of the items used to create their subscales.

Statistical Analyses

Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used for all analyses, which enables the inclusion all available data, even from participants who did not complete every follow-up. All significant results are at the p<.05 level.

Latent growth curve modeling (LGCM).

LGCM for longitudinal data was conducted using lavaan in R (Rosseel, 2012). LGCM takes full advantage of repeated measures to model individual differences in change over time. In LGCM, two parameters, the intercept (initial status) and slope (rate of change/trajectory) for each person, are treated as latent variables. Predictors of each parameter can be identified, and the putative processes (i.e., mediation or moderation) by which each predictor exerts its effects may be tested (Jackson & Allemand, 2014).

Wave 1 self-reported physical health or mental health was used to define the latent intercept. Waves 1 through 6 physical health or mental health with equally spaced intervals were used to define the latent linear slope. Using multigroup LGCM, we examined race and gender effects on the mean intercepts and slopes by comparing nested models among White men (n=482), White women (n=578), Black men (n=226), and Black women (n=291). All continuous covariates were mean-centered and categorical covariates were dummy coded.

To examine race and gender effects on the mean latent intercepts and slopes of each health outcome (i.e., physical health and mental health), we first examined an unconditional model which included no predictors of the latent intercept and slope. These analyses demonstrated that means and variances of the latent intercepts and slopes were significantly different from zero across all groups (all p’s < .001). Further, likelihood ratio tests comparing random versus fixed slope models were significant (PHC: χ2[2] = 84.07; MHC: χ2[2] = 57.94; p’s<.001), indicating that it is warranted to model the latent intercepts and slopes as random.

Next, we fit an unconstrained multigroup model that included covariates (i.e., age, income, education and timing of wave 6 assessment). In order to test for significant race and gender effects on the latent mean intercepts and slopes, we fit a fully constrained model (i.e., all parameters set equal across groups) and then tested this model against models in which the constraints on the latent intercepts and slopes were relaxed based on hypotheses and patterns of differences in mean intercepts and slopes seen in the unconstrained models.

A similar approach was taken for personality models. As for the previous models, we fit fully constrained models that included covariates (i.e., those used in previous models) and the FFM personality domain of interest as the predictor of the latent intercept and slope. Then, based on the selective vulnerability hypothesis and patterns of differences in personality-health associations seen in unconstrained models, we compared the fully constrained model to nested models that relaxed constraints for specific personality-health regression coefficients. For model comparison analyses, the model with lower degrees of freedom (i.e., less constrained) was accepted when a likelihood ratio test was significant at p<.05.

Results

Demographics and Descriptive statistics

Demographics and descriptive statistics for wave 1 variables are reported in Table 1. There were no significant differences among race/gender groups in age (χ2[30]=26.56, p=.65). Black participants had significantly lower self-reported physical health and openness. Zero-order correlations among wave 1 variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Zero-order Correlations for Wave 1 Variables

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical Health | .70* | −.38* | −.33* | .16* | .10* | .14* | .23* | .35* | .30* |

| 2. Mental Health | −.28* | −.49* | .29* | .08* | .18* | .33* | .28* | .16* | |

| 3. Doctor Visits (wave 2) | .14* | −.01 | −.02 | −.02 | −.04 | −.07* | −.08* | ||

| 4. Neuroticism | −.36* | −.08* | −.34* | −.56* | −.21* | −.13* | |||

| 5. Extraversion | .38* | .21* | .29* | .16* | .09* | ||||

| 6. Openness | .20* | .05* | .15* | .30* | |||||

| 7. Agreeableness | .32* | .05* | .08* | ||||||

| 8. Conscientiousness | .20* | .17* | |||||||

| 9. Income | .48* | ||||||||

| 10. Education |

p<.05

Are there race and gender effects on initial levels and trajectories of health?

White men had the highest mean intercept for self-reported physical health and mental health, followed by White women, Black men, and Black women. Mean slopes for physical health and mental health were not significantly different from zero for Black men, Black women and White women, whereas the mean slopes were significantly negative for White men. Parameter estimates for covariates in these models are included in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates for Constrained LGC Trajectory Models

| Physical Health | Mental Health | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Wave 5 completion time | −.01 | −.07 | −.03 | −.02 |

| Education | .15* | .05 | .05 | .03 |

| Income | .21* | .05 | .25* | .04 |

| Age | .01 | .15* | .09* | −.17 |

p≤.05; Standardized estimates

Physical health.

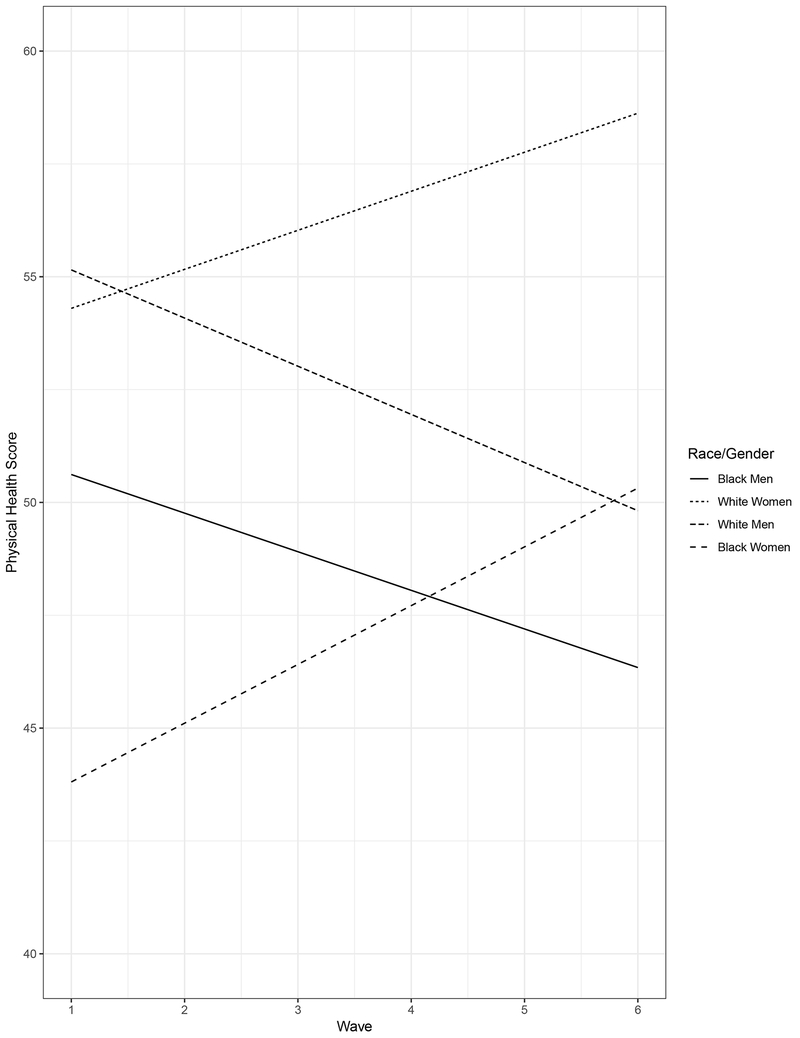

For self-reported physical health, a likelihood ratio test suggested that, compared with the fully constrained model (χ2[185] = 769.807; CFI = .89, RMSEA = .09), a model in which the intercepts and slopes varied freely among race/gender groups was a better fit for the data (likelihood ratio test: χ2[6]=59.38; p<.001). Compared with this latter model, the best fit to the data was one in which the intercepts were set equal between Black men and women and between White men and women, and the slopes were set equal between Black and White men and between Black and White women (likelihood ratio test: χ2[4]=4.96; p=.29). These analyses suggest that Black participants had significantly lower initial levels of self-reported physical health, compared with White participants. The magnitude of physical health change differed significantly between men and women, such that women’s health remained stable whereas men’s health declined. Physical health trajectories are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Physical Health Trajectories by Race and Gender

Mental health.

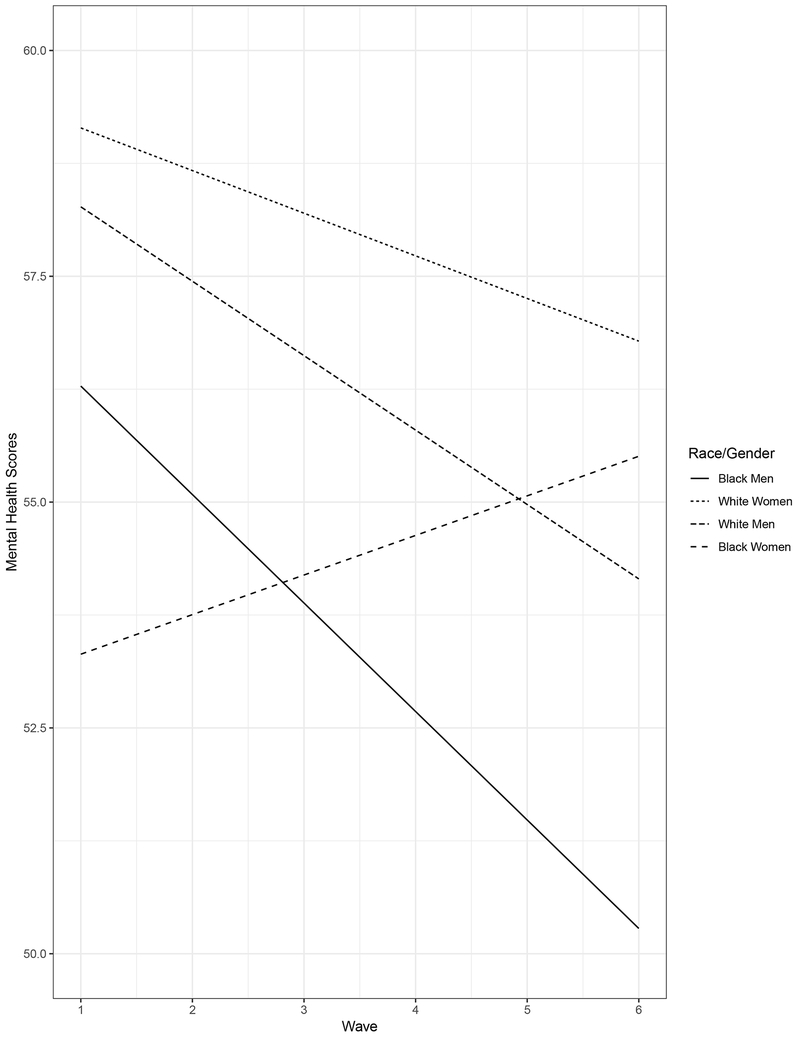

For self-reported mental health, the fully constrained model (χ2[185] = 445.14, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .06) was found to be a better fit for the data when compared to a model in which the intercept and slope were allowed to vary freely across race/gender groups (likelihood ratio test: χ2[6]=2.23, p=.89). These analyses suggest that initial levels and trajectories of self-reported mental health did not differ significantly among race/gender groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mental Health Trajectories by Race and Gender

Are there personality by race interaction effects on health?

Physical health.

Neuroticism was significantly negatively associated with the latent intercept of physical health for all race/gender groups, and was positively associated with the latent slope of physical health for White women. The fully constrained model (χ2[207]=448.54, CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05) was found to be the best fit for the data. Conscientiousness was significantly positively associated with the latent intercept for all groups, and the fully constrained model was the best fit for the data (χ2[207]=427.48, CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Extraversion was significantly positively associated with the latent intercept for White men and women, and negatively associated with the slope for White women. The fully constrained model was the best fit for the data (χ2[207]=414.458, CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Openness was not significantly associated with the latent intercepts or slopes, and the fully constrained model was the best fit for the data (χ2[207]=410.92, CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Agreeableness was significantly positively associated with the latent intercepts for Black men and White women. A likelihood ratio test indicated that a better fit for the data was a model in which the equality constraints were removed for the regression coefficient of the intercept on agreeableness (likelihood ratio test: χ2[3]=11.41; p=.01), and in addition were set equal between Black men and White women, and equal between White men and black women (likelihood ratio test: χ2[2]=.90; p=.64).

Overall, these results suggest that the positive association between agreeableness and the intercept of physical health was significant and of similar magnitude for Black men and White women, whereas this association was not significant for Black women and White men. There were no significant group differences in the magnitude of the associations among neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness or openness with the intercept or slope of physical health (Table 5).

Table 5.

Regression Estimates for Personality Traits

| Physical Health | Mental Health | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Neuroticism | −.27* | .09* | −.51* | .04 |

| Conscientiousness | .16* | −.05 | .27* | .02 |

| Extraversion | .11* | −.06 | .21* | −.00 |

| Openness | .00 | −.02 | −.01 | −.03 |

| Agreeableness (Black men & White women) | .20* | −.02 | .14* | .02 |

| Agreeableness (Black women & White men) | .05 | −.01 | .14* | .02 |

p<.05; Standardized estimates; Covariates: Wave 5 completion time, income, education, age

Note: Personality domains examined in separate models.

Mental health.

Neuroticism was significantly negatively associated, and conscientiousness and extraversion positively associated, with the latent intercept of mental health for all race/gender groups. For these personality traits, the fully constrained models fit the data best (neuroticism: χ2[207]=505.57; conscientiousness: χ2[207]=476.46; extraversion: χ2[207]=492.91; all models: CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Openness was not significantly associated with the latent intercept or slope, and the fully constrained model was the best fit for the data (χ2[207]=466.55, CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Agreeableness was significantly positively associated with the latent intercept for Black men, White women and White men. The fully constrained model was the best fit for the data (χ2[207]=475.71, CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Overall, results suggest that there were no significant group differences in the magnitude of the associations among any of the five personality domains with the intercepts or slopes of mental health (Table 5).

Discussion

The current study examined race and gender disparities in self-reported physical and mental health, and the moderating effects of personality, in a sample of late mid-life Black and White adults. Several findings are notable. Black participants reported lower initial self-reported physical health than White participants; over time, women’s physical health was stable while men’s declined. There were no racial or gender disparities in self-reported mental health. Personality associations with health were of similar magnitude across race and gender, with the exception of the association between agreeableness and initial levels of physical health, which were positively associated only for Black men and White women.

Do race and gender groups differ in initial levels of health and health trajectories?

As in previous research, our analyses found support for the persistent inequality hypothesis between racial groups within the same gender (Brown et al., 2012, 2016; Kim & Miech, 2009; Warner & Brown, 2011). That is, Black men had lower initial self-reported physical health than White men, and the magnitude of this disparity remained stable over time. A similar pattern was seen for Black and White women. These results suggest that demographic disparities in the distribution of health-promoting resources and health risk factors, which contribute to health disparities, remain stable during late mid-life. This appears to be specific to within gender groups in the current sample. On the other hand, when considering disparities in health trajectories between Black women and White men, we found support for the aging-as-leveler hypothesis. We found that physical health trajectories converge between these two groups, whereby Black women initially reported worse physical health than White men, then this health gap closed as White men reported worsening health and Black women reported stable health. These findings are in line with past research showing that some racial/gender disparities in health decline as people age (Brown et al., 2016).

In contrast to past research, we also found support for the cumulative disadvantage hypothesis during mid-life, which previously had been found for physical functioning during early middle-age (45-60 years) and for serious illness trajectories during later mid-life. This hypothesis was supported by disparities between gender groups (within racial groups) such that Black men and women reported similar levels of physical health initially, then their trajectories diverged as self-reported physical health declined for Black men. This is striking given previous research suggesting that Black women experience the greatest declines in health compared with White adults and Black men (e.g., Warner and Brown, 2011). These findings may be particularly stark to areas like St. Louis with high levels of racial inequality. In such areas, the prominent criminalization of Black men, as well as high residential segregation, unemployment, and community violence, may lead Black men experience a higher stress burden than women – even despite Black women’s doubly-marginalized identities – which may, in turn, exacerbate declines in their health over time.

Mental health trajectories support a persistent equality pattern, whereby there are no significant racial differences initially, which then persists over time. These findings are in line with past research showing that compared with White adults, Black adults report similar prevalence of most major mental disorders, and that racial differences in psychological distress are eliminated when accounting for income and education (Hasin et al., 2005; Himle et al., 2009; Keyes, 2009; Lincoln et al., 2010; Tran et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2007, 1997). Current findings may reflect actual equality between Black and White adults in the prevalence of psychological distress and/or mental illness. However, higher levels of mental health stigma among Black adults may influence reporting of distress or symptoms (Thompson, Noel, Campbell, & Jeffrey, 2004; Thornicroft, 2008), suppressing the association between race and psychological distress. Future studies may find racial disparities in other types of mental health trajectories, for example, mental illness severity or chronicity, which have been found to be exacerbated among Black as compared with White adults (Himle et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2007). Nonetheless, our findings suggest that patterns should be considered in which racial groups have similar levels of health at baseline, which then remain similar over time (persistent equality), particularly when studying mental health. Past studies have not considered this type of trajectory pattern, most likely because of their focus on physical health outcomes, which by and large are characterized by racial disparities.

Overall, current results suggest that it is crucial to investigate disparities in health trajectories from an intersectional perspective that considers the contribution of our multiple identities to health and well-being. An intersectional approach takes into account the combined and interactive effects of multiple social identities (e.g., race and gender) on important life outcomes. Social identity impacts individuals’ daily experiences and access to resources throughout their lives, making one’s identity an essential influence on all aspects of development, including personality and health. To date, research has tended to take a unidimensional approach to examining health disparities (i.e., focusing on one identity at a time), obscuring the potential additive or multiplicative effects of multiple identities on outcomes. Intersectional studies are growing in number. The current study helps to fill a gap in the literature on longitudinal race/gender health disparities in the context of aging.

Do personality traits moderate the impact of race on health?

Contrary to the selective vulnerability hypothesis, which posits that specific personality traits will more robustly impact the health of individuals from disadvantaged groups, the relationship of lower initial levels of self-reported physical health with higher neuroticism, and lower conscientiousness and extraversion was of similar magnitude across all race/gender groups. A negative association between neuroticism and physical health is one of the most robust findings in personality and health research (Ferguson, 2013; Hampson, 2012). Individuals with higher levels of neuroticism are at higher risk for experiencing stressful life events (Iacovino et al., 2016; Kendler, Gardner, & Prescott, 2003), may be more likely to use unhealthy coping mechanisms (e.g., tobacco and alcohol) (Korotkov, 2008), and/or may have less access to social support (Michal, Wiltink, Grande, Beutel, & Brahler, 2011). Each of these factors may be pathways by which neuroticism influences physical or mental health (Cummings, Neff, & Husaini, 2003; Iacovino et al., 2016; Keyes, Barnes, & Bates, 2011; Miller et al., 2011; Takahashi, Edmonds, Jackson, & Roberts, 2013; Taylor, Repetti, & Seeman, 1997). Current results suggest that neuroticism, conscientiousness and extraversion have similar associations with health among White and Black men and women, though future work is needed to examine whether the specific mechanisms of these associations are similar across groups.

Agreeableness was positively associated with physical health only for Black men and White women. Agreeableness represents individual differences in interpersonal connectedness, warmth, trust, and low hostility (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Hampson, 2012). Agreeableness has been associated with self-rated health and health-related factors (e.g., obesity) in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Letzring et al., 2014; Sutin, Ferrucci, Zonderman, & Terracciano, 2011). Current findings suggest that interpersonal cooperation may be particularly beneficial for the physical health of Black men and White women. Black men are often stereotyped as threatening or aggressive (Wilson, Hugenberg, & Rule, 2017). Thus, higher agreeableness may lead others to be perceive Black men as more socially “acceptable,” potentially reducing psychosocial and physiological stress in social settings, particularly in inter-racial interactions. A similar “social acceptability” effect may be seen for White women, whom are often expected to be agreeable (Ghavami & Peplau, 2013). Since this is the first study to find such race/gender differences in the association between agreeableness and health, more research is needed to buttress and expand current findings. Future work may examine potential mechanisms of this association, as well as race/gender differences in personality associations with other health outcomes (e.g., mortality, illness onset).

Personality-health associations were found for the health intercepts rather than slopes, suggesting that these associations are cross-sectional in nature. This opens the possibilities that health impacts personality, that the relationship is transactional, and/or that there is some third variable that accounts for both. Current findings controlled for various major factors associated with health, such as SES and age, but other factors such as childhood adversity may impact both personality and health, leading to current findings. Further research is needed to examine these possibilities and to clarify the nature of associations among race, gender, personality and health.

Current results suggest that personality traits are psychosocial resources that impact health similarly across race and gender. Past studies have rarely examined the intersection of race and gender as moderators of personality-health effects. As researchers begin to investigate the possibility of modifying personality traits in order to personalize medicine and influence health outcomes (Israel et al., 2014; Jackson, Hill, Payne, Roberts, & Stine-Morrow, 2012), it is crucial to establish that personality-health effects operate similarly across race and gender. In addition, future research may better elucidate whether the mechanisms by which personality impacts health differ across demographic groups.

Limitations and future directions

The current study is not without limitations. Health change was examined over a relatively short time period; thus, analyses may not have detected race/gender differences and personality effects that may emerge over a longer follow-up period. In addition, the current sample is restricted both by age and geography. Patterns seen here may not be replicated in samples from other regions of the United States or in other countries. However, the frequent overlap between current findings and past studies utilizing nationally representative samples suggest that current patterns are representative of a large swath of adults in the United States. We also did not have the ability to examine our hypotheses in other racial/ethnic groups, given the composition of the community in which our study was conducted. Our sample was representative, however, of the regional population from which it was drawn.

Further limitations include the lack of objective health measures, such as blood pressure or cholesterol levels. We also did not examine trajectories of diagnosed physical or mental illnesses. Social desirability factors and stigmatization of illness may lead individuals to underreport health problems, particularly individuals with marginalized identities. Past research suggests that self-reports of physical and mental health tend to be strongly associated with objective health measures (Idler, Hudson, & Leventhal, 1999). Nonetheless, future research should examine the role of personality in racial/ethnic disparities in health trajectories using more objective measures of illness and additional health outcomes, such as mortality and illness onset.

Strengths of our study include the examination of a large sample of Black and White late mid-life adults. Black people are often underrepresented in studies of personality and health, making it difficult to draw any conclusions about the impact of personality on health within this important racial group. The current study starts to fill this gap in the literature. In addition, few studies have examined racial disparities in both static levels of health and health trajectories as well as the impact of personality on these disparities. Even fewer have considered the range of outcomes examined in the current study, focusing typically on physical functioning and/or cardiovascular disease. Current analyses also took an intersectional approach to understanding health disparities, which enables a more appropriately nuanced view of health disparities and their determinants. Finally, the use of comprehensive personality questionnaires based on both self-reports and informant-reports strengthens current analyses by improving the reliability and validity of personality measurements and therefore, personality effects.

Conclusions

Our findings have implications for the study of health disparities as well as personality and health. First, our findings show that racially diverse samples are crucial in personality and health research. In recent years, samples of participants have become more representative of the U.S. population, a trend that must continue. Our findings furthermore suggest that an intersectional framework is needed to accurately characterize disparities in health trajectories, as well as the contribution of risk factors to these disparities. In addition, our findings show that examining race and gender as moderators of personality-health associations is warranted. Doing so will enable a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of how personality influences health. Finally, within the framework of more inclusive samples and intersectional approaches, both racial disparities and personality and health research would benefit from more closely evaluating potential mechanisms of action that explain the impacts of race and/or personality on health. This will involve analytical methods that can model both simple and complex mediating and moderating relationships among risk and protective factors that link race and/or personality with health, including psychological, social, biological, and environmental variables.

Table 3.

Latent Variable Estimates for Constrained LGC Trajectory Models

| Black Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | Mental Health | |||

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Mean | 50.43* | −.16 | 57.60* | −.60 |

| Variance | 70.94* | 2.37* | 57.18* | 2.12* |

| Black Women | ||||

| Mean | 50.43* | −.07 | 57.60* | −.60 |

| Variance | 70.94* | 2.37* | 57.18* | 2.12* |

| White Men | ||||

| Mean | 52.99* | −.16 | 57.60* | −.60 |

| Variance | 70.94* | 2.37* | 57.18* | 2.12* |

| White Women | ||||

| Mean | 52.99* | −.07 | 57.60* | −.60 |

| Variance | 70.94* | 2.37* | 57.18* | 2.12* |

p≤.05; All estimates standardized; Covariates included in analyses: age, income, education and timing of wave 6 assessment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Sherman James and Dr. Vetta Sanders-Thompson for their helpful guidance in interpreting the results of this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of SPAN staff and participants. This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants NIA 1F31AG048729, NIA 3R01AG045231, NIA 3R01AG045231-01A1S1 and NIMH R01MH077840.

Footnotes

Wave participation rates differ from attrition rates because some participants missed a follow-up assessment and then returned for the next one. These participants were not considered to have dropped out from the study and were not included in total attrition rates.

References

- SAMHSA (2015). Racial/Ethnic differences in mental health service use among adults. HHS Publication No. SMA-15-4906 Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Ault-Brutus AA (2012). Changes in racial-ethnic disparities in use and adequacy of mental health care in the United States, 1990–2003. Psychiatric Services, 63(6), 531 10.1176/appi.ps.201000397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TH, O’Rand AM, & Adkins DE (2012). Race-ethnicity and health trajectories: tests of three hypotheses across multiple groups and health outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(3), 359–77. 10.1177/0022146512455333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TH, Richardson LJ, Hargrove TW, & Thomas CS (2016). Using Multiple-hierarchy stratification and life course approaches to understand health inequalities: The intersecting consequences of race, gender, SES, and age. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 57(2), 200–222. 10.1177/0022146516645165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B, Khan A, & Harper M (2009). Gender, race/ethnicity, personality, and Interleukin-6 in urban primary care patients. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23(5), 636–642. 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.009.Gender [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Fiscella K, Kawachi I, & Duberstein PR (2010). Personality, socioeconomic status, and all-cause mortality in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(1), 83–92. 10.1093/aje/kwp323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Roberts B, & Duberstein P (2011). Personality and longevity: Knowns, unknowns, and implications for public health and personalized medicine. Journal of Aging Research, 2011, 759170 10.4061/2011/759170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT Jr., & McCrae RR (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13. 10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings S, Neff J, & Husaini B (2003). Functional impairment as a predictor of depressive symptomatology: The role of race, religiosity, and social support. Health & Social Work, 28(1), 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, & Giles WH (2017). Vital signs: Racial disparities in age-specific mortality among Blacks or African Americans — United States, 1999–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(17), 444–456. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler WW, Oths KS, & Gravlee CC (2005). Race and ethnicity in public health research: Models to explain health disparities. Annual Review of Anthropology, 34(1), 231–252. 10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot AJ, Turiano NA, & Chapman BP (2016). Socioeconomic status interacts with conscientiousness and neuroticism to predict circulating concentrations of inflammatory markers. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 1–11. 10.1007/s12160-016-9847-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson E (2013). Personality is of central concern to understand health: Towards a theoretical model for health psychology. Health Psychology Review, 7(Suppl 1), S32–S70. 10.1080/17437199.2010.547985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, & Farmer MM (1996). Double jeopardy, aging as leveler, or persistent health inequality? A longitudinal analysis of white and black Americans. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51(6), S319–S328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, & Bound J (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–33. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami N, & Peplau LA (2013). An intersectional analysis of gender and ethnic stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1), 113–127. 10.1177/0361684312464203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs TA, Okuda M, Oquendo MA, Lawson WB, Wang S, Thomas YF, & Blanco C (2013). Mental health of African Americans and Caribbean blacks in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. American Journal of Public Health, 103(2), 330–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Cook BL, Ault-Brutus A, & Alegría M (2015). Intersection of race-ethnicity and gender in depression care: Screening, access, and minimally adequate treatment. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 66(3), 258–64. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE (2012). Personality processes: Mechanisms by which personality traits “get outside the skin”. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 315–39. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2005). Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(10), 1097–106. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, & Morales LS (2001). The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 350–357. 10.3109/07853890109002089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle JA, Baser RE, Taylor RJ, Campbell RD, & Jackson JS (2009). Anxiety disorders among African Americans, blacks of Caribbean descent, and non-Hispanic whites in the United States. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(5), 578–90. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J, Lepkowski J, Kinney A, Mero R, Kessler R, & Herzog A (1994). The social stratification of aging and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35(3), 213–234. 10.2307/2137277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huprich SK, Bornstein RF, & Schmitt TA (2011). Self-report methodology is insufficient for improving the assessment and classification of Axis II personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(5), 557–70. 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.5.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovino JM, Bogdan R, & Oltmanns TF (2016). Personality predicts health declines through stressful life events during late mid-life. Journal of Personality, 84(4), 536–46. 10.1111/jopy.12179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Hudson SV, & Leventhal H (1999). The meanings of self-ratings of health: A qualitative and quantitative approach. Research on Aging, 21(3), 458–476. 10.1177/0164027599213006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israel S, Moffitt TE, Belsky DW, Hancox RJ, Poulton R, Roberts B, … Caspi A (2014). Translating personality psychology to help personalize preventive medicine for young adult patients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(3), 484–98. 10.1037/a0035687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JJ, Weston SJ & Schultz L (2017). Health and personality development In Specht J (Ed.), Handbook of Personality Development. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JJ, & Allemand M (2014). Moving personality development research forward: Applications using structural equation models. European Journal of Personality, 28(3), 300–310. 10.1002/per.1964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JJ, Connolly JJ, Garrison SM, Leveille MM, & Connolly SL (2015). Your friends know how long you will live: A 75-year study of peer-rated personality traits. Psychological Science, 26(3), 335–40. 10.1177/0956797614561800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JJ, Hill PL, Payne BR, Roberts BW, & Stine-Morrow EAL (2012). Can an old dog learn (and want to experience) new tricks? Cognitive training increases openness to experience in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 27(2), 286–92. 10.1037/a0025918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas BS, & Lando JF (2000). Negative affect as a prospective risk factor for hypertension. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(2), 188–96. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10772396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassaint C, & Siegler I (2011). Low life course socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with negative NEO PI-R personality patterns. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18(1), 13–21. 10.1007/s12529-009-9069-x.Low [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, & Prescott CA (2003). Personality and the experience of environmental adversity. Psychological Medicine, 33(7), 1193–202. http://doi.org/0.1017/S003329170300829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM (2009). The Black-White paradox in health: Flourishing in the face of social inequality and discrimination. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1677–706. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes K, Barnes D, & Bates L (2011). Stress, coping, and depression: Testing a new hypothesis in a prospectively studied general population sample of US-born Whites and Blacks. Social Science & Medicine, 72(5), 650–659. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.005.Stress [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, & Miech R (2009). The Black-White difference in age trajectories of functional health over the life course. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 68(4), 717–25. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek KD, Arias E, & Anderson RN (2013). How did cause of death contribute to racial differences in life expectancy in the United States in 2010? NCHS Data Brief, (125), 1–8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24152376 [PubMed]

- Korotkov D (2008). Does personality moderate the relationship between stress and health behavior? Expanding the nomological network of the five-factor model. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1418–1426. 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers SMA, Westerhof GJ, Kovács V, & Bohlmeijer ET (2012). Differential relationships in the association of the Big Five personality traits with positive mental health and psychopathology. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(5), 517–524. 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letzring TD, Edmonds GW, & Hampson SE (2014). Personality change at mid-life is associated with changes in self-rated health: Evidence from the Hawaii Personality and Health Cohort. Personality and Individual Differences, 58, 60–64. 10.1016/j.paid.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie-Blanton M, Parsons PE, Gayle H, & Dievler A (1996). Racial differences in health: Not just black and white, but shades of gray. Annual Review of Public Health, 17(1), 411–448. 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.002211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chae DH, & Chatters LM (2010). Demographic correlates of psychological well-being and distress among older African Americans and Caribbean Black adults. Best Practices in Mental Health, 6(1), 103–126. Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3134829&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Sutin AR, Ferrucci L, & Costa PT (2008). Personality traits and subjective health in the later years: The association between NEO-PI-R and SF-36 in advanced age is influenced by health status. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(5), 1334–1346. 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magee CA, Heaven PCL, & Miller LM (2013). Personality change predicts self-reported mental and physical health. Journal of Personality, 81(3), 324–334. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00802.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 171–179. 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michal M, Wiltink J, Grande G, Beutel ME, & Brähler E (2011). Type D personality is independently associated with major psychosocial stressors and increased health care utilization in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 134(1–3), 396–403. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, & Parker KJ (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(6), 959–97. 10.1037/a0024768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Rodrigues MM, Weinstein Y, & Gleason MEJ (2014). Prevalence of personality disorders at midlife in a community sample: Disorders and symptoms reflected in interview, self, and informant reports. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(2), 177–188. 10.1007/s10862-013-9389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin PB, Krch D, Sutter M, Snipes DJ, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Kolakowsky-Hayner Stephanie A, Wright J, & Lequerica A. (2015). Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health over the first 2 years after traumatic brain injury : A model systems study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95(12), 2288–2295. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.07.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LJ, & Brown TH (2016). (En)gendering racial disparities in health trajectories: A life course and intersectional analysis. SSM - Population Health, 2, 425–435. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfsen LS, & Kronenfeld JJ (2014). Gender differences in functional health: Latent curve analysis assessing differential exposure. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(4), 590–602. 10.1093/geronb/gbu021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savla J, Davey A, Costa PT, & Whitfield KE (2007). Replicating the NEO-PI-R factor structure in African-American older adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(5), 1279–1288. 10.1016/j.paid.2007.03.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shuey KM, & Willson AE (2008). Cumulative disadvantage and Black-White disparities in life-course health trajectories. Research on Aging, 30(2), 200–225. 10.1177/0164027507311151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spence CT, & Oltmanns TF (2011). Recruitment of African American men: Overcoming challenges for an epidemiological study of personality and health. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 377–380. 10.1037/a0024732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, & Terracciano A (2011). Personality and obesity across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 579–592. Retrieved from 10.1037/a0024286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Edmonds GW, Jackson JJ, & Roberts BW (2013). Longitudinal correlated changes in conscientiousness, preventative health-related behaviors, and self-perceived physical health. Journal of Personality, 81(4), 417–427. 10.1111/jopy.12007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Repetti RL, & Seeman T (1997). Health psychology: What is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 411–47. 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson VLS, Noel JG, Campbell J, & Jeffrey G (2004). Stigmatization, discrimination, and mental health : The impact of multiple identity status. Identity, 74(4), 529–544. 10.1037/wO2-9432.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G (2008). Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 17, 14–19. 10.1017/S1121189X00002621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TV, DeMarco R, Chan K, & Nguyen T-N (2015). Race, age and serious psychological distress in the USA. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 8(2), 162–175. 10.1080/17542863.2014.913644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turiano N, Pitzer L, Armour C, Karlamangla A, Ryff C, & Mroczek D (2012). Personality trait level and change as predictors of health outcomes: Findings from a national study of Americans (MIDUS). The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 67(1), 4–12. 10.1093/geronb/gbr072.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, & Kessler RC (2005). Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 629–40. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, & Brown TH (2011). Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 72(8), 1236–48. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston SJ, Hill PL, & Jackson JJ (2015). Personality traits predict the onset of disease. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 309–317. 10.1177/1948550614553248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, & Mohammed S (2010). Race, socioeconomic status and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186, 69–101. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x.Race [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, & Jackson JS (2007). Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(3), 305–15. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson S, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JP, Hugenberg K, & Rule NO (2017). Racial bias in judgments of physical size and formidability: From size to threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(6), 629–40. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]