Abstract

Background

Systemic inflammation induced by sterile or infectious insults is associated with an enhanced susceptibility to life-threatening opportunistic, mostly bacterial, infections due to unknown pathogenesis. Natural killer (NK) cells contribute to the defence against bacterial infections through the release of Interferon (IFN) γ in response to Interleukin (IL) 12. Considering the relevance of NK cells in the immune defence we investigated whether the function of NK cells is disturbed in patients suffering from serious systemic inflammation.

Methods

NK cells from severely injured patients were analysed from the first day after the initial inflammatory insult until the day of discharge in terms of IL-12 receptor signalling and IFN-γ synthesis.

Findings

During systemic inflammation, the expression of the IL-12 receptor β2 chain, phosphorylation of signal transducer and activation 4, and IFN-γ production on/in NK cells was impaired upon exposure to Staphylococcus aureus. The profound suppression of NK cells developed within 24 h after the initial insult and persisted for several weeks. NK cells displayed signs of exhaustion. Extrinsic changes were mediated by the early and long-lasting presence of growth/differentiation factor (GDF) 15 in the circulation that signalled through the transforming growth factor β receptor I and activated Smad1/5. Moreover, the concentration of GDF-15 in the serum inversely correlated with the IL-12 receptor β2 expression on NK cells and was enhanced in patients who later acquired septic complications.

Interpretation

GDF-15 is associated with the development of NK cell dysfunction during systemic inflammation and might represent a novel target to prevent nosocomial infections.

Fund

The study was supported by the Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery, University Hospital Essen.

Keywords: Natural killer cells, Opportunistic infections, Interferon gamma, Interleukin 12, Transforming growth factor receptor, Immunosuppression

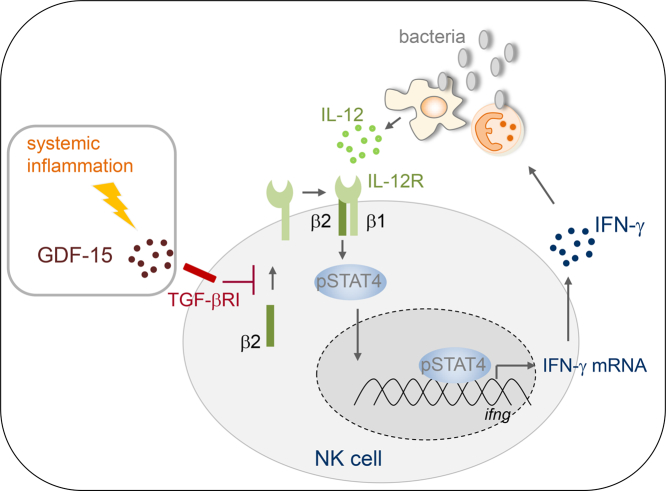

Graphical abstract

Research in context.

Evidence before the study

Critically ill patients who suffer from systemic inflammation (e.g. caused by major traumatic/surgical injuries or severe infections) are highly susceptible to life-threatening nosocomial infections during their stay on the intensive care unit. The pathogenesis of the impaired immune defence during systemic inflammation is still poorly understood. Accordingly, efficient therapeutic interventions that reduce the risk for opportunistic infections are lacking. Moreover, there exists no reliable marker that identifies patients who are at advanced risk for infectious complications.

Added value of this study

Natural killer cells secrete IFN-γ upon stimulation with IL-12 and thereby contribute to the efficient elimination of invading bacteria. In this study, we discovered a profound suppression of the IL-12/IFN-γ axis in circulating human natural killer cells that developed early after a severe inflammatory insult and was maintained for several weeks. The suppression of natural killer cells was largely mediated by a soluble factor in the serum that signalled through the TGF-β receptor I. We provide evidence that this soluble factor was GDF-15 that was released into the blood at high concentration throughout the observation period of the patients and inversely correlated with IL-12 receptor expression on natural killer cells. Importantly, patients who later developed nosocomial infection displayed enhanced levels of GDF-15 as soon as 1 d after the initial inflammatory insult.

Implications of all the available evidence

Natural killer cells rapidly lose their capacity to secrete IFN-γ during systemic inflammation and consequently might fail to support immune defence mechanisms against invading pathogens. Inhibitors of the TGF-β receptor I that are already tested in clinical studies for cancer therapy restore NK cell function and might be appropriate to reduce infectious complications in systemic inflammation. Moreover, GDF-15 that signals through the TGF-β receptor I might serve as an early marker to identify patients at high risk for nosocomial infections.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Systemic inflammation represents a common state of the immune system of critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and can be associated with life-threatening multiple organ failure and poor long-term outcome [[1], [2], [3]]. Peripheral infection and tissue injury (e.g. induced by a mechanical insult or by self-destruction in autoimmunity) induce local inflammation that aims to restore homeostasis [4]. In contrast, severe infectious or traumatic insults induce uncontrolled systemic inflammation due to the acute and massive release of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), respectively, into the circulation [5]. Less appreciated so far is the fact that systemic inflammation, independent of its origin, is paralleled by the development of immunosuppression and thereby accounts for 4 million nosocomial infections in ICUs per year in Europe [6]. Consequently, severe tissue injury e.g. as a result of both surgical intervention as well as accidental trauma, not only enhances the susceptibility of patients to nosocomial infections but also promotes the growth of metastasis in case of cancer patients [7,8]. Why some patients succumb to septic complications while others do not despite a similar degree of injury is still a matter of debate. In addition, no reliable marker exists so far that allows the identification of patients who are prone to infectious complications and accordingly might be stratified for specific therapy.

Anti-inflammatory mechanisms usually arise time-delayed to the onset of inflammation as part of the tightly regulated process of resolution [9]. Thus, the co-existence of systemic inflammation and immunosuppression in critically ill patients represents a particular pattern of immune disturbance that warrants further investigation [10].

Cells of the innate immune system such as neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells play a central role in the defence against bacterial infections. Macrophages and neutrophils are professional phagocytes and efficiently take up and eliminate invading pathogens. However, in the absence of adequate stimulation by Interferon (IFN) γ they possess only limited bactericidal capacity. NK cells are a major source of IFN-γ during bacterial infections [11]. Two major subsets of human NK cells are distinguished in peripheral blood: CD56dim NK cells primarily act as cytotoxic effector cells that eradicate tumour cells and virus-infected cells whereas CD56bright NK cells show weak cytotoxic activity but release substantial amounts of diverse cytokines [12,13]. CD56bright NK cells represent approximately 10% of the human circulating NK cell population and secrete high amounts of IFN-γ in response to interleukin (IL) 12. The corresponding IL-12 receptor (IL-12R) is a heterodimer and consists of a constitutively expressed β1 chain and a β2 chain that is expressed only upon stimulation of the cell [14]. Ligation of the IL-12R induces the phosphorylation of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) 4 that enables the transcription of the IFNG gene [15,16].

Dendritic cells and to a lesser extent monocytes/macrophages serve as accessory cells for NK cell activation as they secrete IL-12 upon contact with PAMPs [17,18]. NK cell-derived IFN-γ further increases the release of IL-12, thus creating a positive feedback loop between accessory cells and NK cells that may be restricted by anti-inflammatory cytokines in the local microenvironment [19,20]. Additionally, the extent of IFN-γ synthesis is regulated by the balance of stimulatory (e.g. NKG2D) and inhibitory receptors (e.g. NKG2A) on the surface of NK cells and the presence of the respective ligands on accessory cells [21,22].

NK cells from patients who suffer from infectious or non-infectious systemic inflammation display a defective IFN-γ production of unknown origin [23,24]. Here, we investigated the mechanisms underlying the disturbed function of NK cells in patients suffering from severe systemic inflammation. We discovered a profound and long-lasting suppression of CD56bright NK cells in terms of IFN-γ synthesis that was associated with an impaired IL-12R signalling due to cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic changes. Moreover, we identified circulating growth/differentiation factor (GDF) 15 as a novel potential target for the restoration of NK cell function and as marker for patients at high risk for nosocomial infections.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and study design

Inclusion criteria for this study were an Injury Severity Score (ISS) ≥16 and age ≥ 18 years. Patients with isolated head injury, HIV infection, and immunosuppressive therapies were excluded. Patients were enrolled at four different level I trauma centres (University Hospital Essen, Germany; University Hospital Dusseldorf, Germany; Ulm University Medical Centre, Germany; and University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland). Group 1: Heparinized blood and serum were obtained from patients (n = 10) who were admitted to the emergency room at the University Hospitals of Essen and Dusseldorf between January and September 2013. Blood was drawn 24 h (40 ml), 4 d (10 ml), 6 d (10 ml), and 8 d (40 ml) after injury as well as on the day of discharge or of the transfer to another hospital or rehabilitation centre (40 ml). The majority of these patients sustained severe to critical injuries of the head/neck, thorax, and extremities due to accidental trauma or to fall. None of the patients suffered from severe basal diseases that required strong medication. At each time point the planned blood withdrawal was approved by the responsible physician. Some blood samples were insufficient to perform all analyses and caused missing values that are indicated in the figure legends. As control, whole blood from healthy volunteers (n = 8) who were recruited from the laboratory staff and from outside was analysed.

For subsequent analyses of circulating factors, sera from patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and who were comparable to the patients in group 1 in terms of age, sex, and morbidity were selected from a collection of samples located at two different sites (the person who selected the sera was blinded to the data obtained from group 1):

Group 2: Serum samples (1 and 5 d after injury) from patients (n = 19) who were admitted to the emergency room at the University Hospital Ulm between December 2013 and July 2016.

Group 3: Serum samples (1 and 5 d after injury) from patients (n = 20) who were admitted to the emergency room at the Division of Trauma Surgery at the University Hospital Zurich from December 2009 to March 2012. Sera from patients who developed a septic complication (n = 10) and patients who remained free of sepsis (n = 10) were selected. Based on the Systemic Inflammation score (SI score), secondary sepsis in injured patients was defined as ΔSI score (difference of SI score between two consecutive time points) ≥ +2 points in concomitance with an infectious focus or positive blood cultures [25,26]. The characteristics of patients of all groups and control subjects are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Group 3 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls n = 8 | Injury n = 10 | Injury n = 19 | Injury n = 20 | |

| Age [y] | 43 (38–47) | 48 (42–58) | 47 (28–56) | 49 (27–63) |

| Sex m/f (% m) | 6/2 (75) | 8/2 (80) | 15/4 (82) | 15/5 (75) |

| Injury severity score (ISS) | 25 (22−30)⁎ | 34 (29–41) | 36 (33–45) | |

| SOFAmax | 11(10–15) | 11(8–13) | 9 (4–14) | |

| ICU length of stay | 27 (14–33) | 15 (6–22) | 15 (3−31) | |

| Sepsis (%) | 0 | 0 | 50 | |

| Sepsis diagnosis [d] | 9 (7–15) | |||

Characteristics of control subjects and recruited patients (groups 1 to 3). Values are given as median (interquartile range). Differences between the three groups of patients were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis Test followed by Dunn's Multiple Comparison test. Differences between controls and patients within group 1 were tested using the Mann Whitney Test. Discrete variables were tested using the χ2 test.

, p < 0·05 vs. group 3; SOFAmax, maximal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score within the first 5 d.

The study was approved by the local ethic committees of the University Hospital Essen, the University Hospital Dusseldorf, the University Ulm, and the University Hospital Zurich. After verification of the inclusion criteria by an independent physician, the written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their legal representatives. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Preparation of mononuclear cells and serum

Heparinized blood was used to isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using a standard protocol for Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and subsequent red blood cell lysis. The PBMC were immediately used for FACS analyses and cell culture.

Sterile serum was obtained from clotted whole blood of patients and healthy control subjects after centrifugation at 2000g for 10 min. The sera were aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until use. For depletion of GDF-15, 96-well flat-bottom plates (MaxiSorp, NUNC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were coated with antibodies against human GDF-15 (2 μg/ml; clone I47627, Biotechne, Abingdon, UK) or with the corresponding mouse IgG2b isotype control antibodies (2 μg/ml; clone 20116, Biotechne) for 18 h. The plates were each washed twice with PBS/0·05% Tween 20 and with PBS. After blocking with 1% BSA for 1 h and washing, serum (20% in PBS v/v) was added to the coated wells for 1 h at 4 °C. Thereafter, the serum was aspirated and transferred into fresh plates coated with identical antibodies. The transfer of the sera into freshly coated wells was performed in total 3 times. After each step, the remaining concentration of GDF-15 in the sera was quantified by ELISA. The efficiency of the depletion of GDF-15 was 100% and 70% for sera from healthy controls and the patients' sera, respectively.

2.3. Cell culture

PBMC were cultured in VLE RPMI 1640 Medium (containing stable glutamine) supplemented with 100 U/ml Penicillin and 100 μg/ml Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Depending on the experimental set up, the culture medium contained 2% or 10% human serum or 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Cultures of PBMC were set up at least in triplicates (4 × 105 cells/well) in 96-well flat bottom plates (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) at a total volume of 200 μl/well and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

PBMC were rested for 30 min before addition of 1 ng/ml recombinant human IL-12, 1 ng/ml recombinant human IL-2, 5 ng/ml IL-15, 5 ng/ml IL-18, 10 ng/ml GDF-15 (all cytokines from Biotechne), 4 μM SB431542 (inhibitor of ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7; Tocris, Biotechne), or 1 μM GW788388 (selective inhibitor of ALK5; Tocris) where indicated. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as the solvent of the inhibitor and served as negative control. Thirty min later, PBMC were stimulated with heat-inactivated S. aureus (Pansorbin Cells Standardized, 0.05% (v/v), Calbiochem, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany or heat-killed S. aureus (HKSA), 0.5 × 106 bacteria /ml, Invivogen, San Diego, CA), inactivated L. monocytogenes (15 × 106/ml; Invivogen, San Diego, CA), or ssRNA40 (250 ng/ml; Invivogen) as indicated. Unstimulated PBMC served as negative control. After 18 h, PBMC were subjected to flow cytometry and the supernatants were harvested and stored at −20 °C.

Monocytes were isolated from PBMC of healthy donors using CD14 MicroBeads (Miltenyi) as recommended by the manufacturer. Monocytes were seeded in 96-well plates (1.5 × 105/well) in medium supplemented with 1 % serum from healthy control subjects or from patients. Monocytes were stimulated with S. aureus in the absence or presence of 10 ng/ml human recombinant IFN-γ (Biotechne). The supernatant was harvested after 18 h and stored at −20 °C.

2.4. Flow cytometry

Cell surface marker staining was performed as described previously [27]. The following fluorochrome-labelled antibodies were used: anti-CD3 (clone MEM-57, fluorescein-labelled, ImmunoTools, Friesoythe, Germany), anti-CD56 (clone CMSSB, allophycocyanin-labelled, eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-IL-12Rβ2 chain (clone 2B6/12β2, phycoerythrin (PE) -labelled, BD Biosciences), anti-CD16 (clone, 3G8, PE-Cy7-labelled, Biolegend, San Diego, CA), anti-NKG2D (clone 1D11, PE-labelled, BioLegend), anti-CD62L (clone DREG-56, PE-labelled, BioLegend), anti-IL-12Rβ1 chain (clone 2.4E6, PE-labelled, BD Biosciences), anti-CD69 (clone FN50, PE-labelled, ImmunoTools), anti-CD25 (clone MEM-181, PE-labelled, ImmunoTools), anti-CD107a (clone H4A3, PE/Cy5-labelled BD Biosciences).

Intracellular staining for phosphorylated STAT4 and Smad1/8 proteins was performed after 18 h of culture using antibodies against phosphorylated STAT4 (pY693; clone 38/p-Stat4, PE-labelled, BD Biosciences), phosphorylated Smad1/8 (cross-reactive with pSmad5; clone N6-1233, PE-labelled, BD Biosciences), and the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) as described previously [27].

For intracellular staining of IFN-γ, GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) was added to the cells for additional 5 h. After surface staining of CD3 and CD56 the cells were fixed and permeabilized using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences). Intracellular staining with PE-labelled antibodies against IFN-γ (clone 4S·B3, BioLegend) was performed in Permeabilization Buffer (BD Biosciences) for 20 min at 4 °C followed by washing with Cell Wash (BD Biosciences).

In general, staining with the corresponding isotype control antibodies was performed to determine the threshold for specific staining. The threshold was set at 1% false positive cells. All Data were acquired using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and were analysed using CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences).

For degranulation assays, PBMC cultures were set up in medium containing 4% FCS. Monoclonal antibodies against CD107a were added and cells were incubated with K562 target cells for 3 h. Control samples were incubated without target cells to detect spontaneous degranulation. Thereafter, samples were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD56 antibodies.

2.5. Quantification of cytokines and C-reactive protein

Supernatants were assessed for the concentration of human IL-12 using a highly sensitive ELISA (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Biotechne) according to manufacturer's instructions. Human GDF-15, IL-6, and TGF-β1 in the sera were quantified by ELISA (DuoSet, R&D Systems, Biotechne). For examination of active TGF-β1 the sera were not acidified. The detection limit was 0.8 pg/ml for GDF-15, 7.8 pg/ml for IL-12, 9.4 pg/ml for IL-6, and 31.3 pg/ml for TGF-β1. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were obtained from routine clinical diagnostics.

2.6. Reporter assay for Smad activation

PBMC were infected with adenoviruses containing the Smad1/5 reporter construct Ad5-BRE-Luc (‘BRE’) or the Smad2/3 reporter construct Ad5-CAGA9-MLP-Luc (‘CAGA’; both kindly provided by Dr. O. Korchinsky and Prof. P. ten Dijke) as previously described [[28], [29], [30]]. The reporter constructs enabled Smad-driven luciferase activity. The mixture of cells and viruses were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2% FCS in a 96-well plate for 24 h. Thereafter, sera or recombinant human GDF-15 (100 ng/ml; Lot STO0917032 and STO2616061, Biotechne), each in the absence or presence of 5 μM SB431542, was added. Where indicated, the sera were depleted of GDF-15 as described above prior to use in the reporter assay. Recombinant bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 2 (10 ng/ml; Peprotech, Hamburg, Germany) or transforming growth factor (TGF) β1 (5 ng/ml; Peprotech) served as positive controls. All samples were set up in quadruplicates. After 48 h, luciferase signals were detected with the help of the Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer. Luciferase signals were measured immediately (Omega plate reader, BMG labtech). The infection efficiency was determined by fluorescence microscopy using viral particles containing an Ad5-GFP construct and ranged between 10 and 15% of PBMC. All values were normalized to PBMC that were cultured in medium only.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Preparation of graphs and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA). Depending on the nature of the data parametric or non-parametric, paired or unpaired tests (two-sided Student's t-test, ANOVA, Mann Whitney U test, Wilcoxon signed rank test, Kruskal-Wallis test, or Friedman test) were used for statistical analyses as indicated in the figure legends. Correlations between two parameters were calculated using Spearman r analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Systemic inflammation impairs S. aureus-induced IFN-γ production by CD56bright NK cells

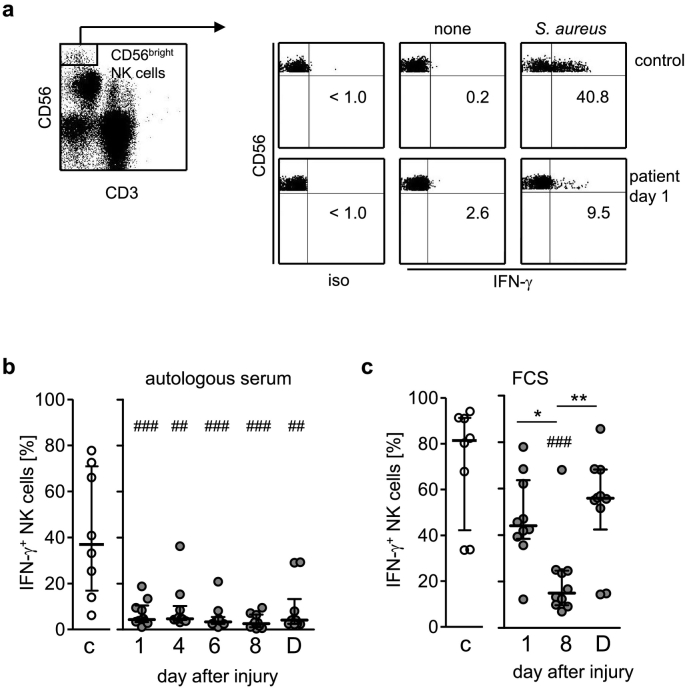

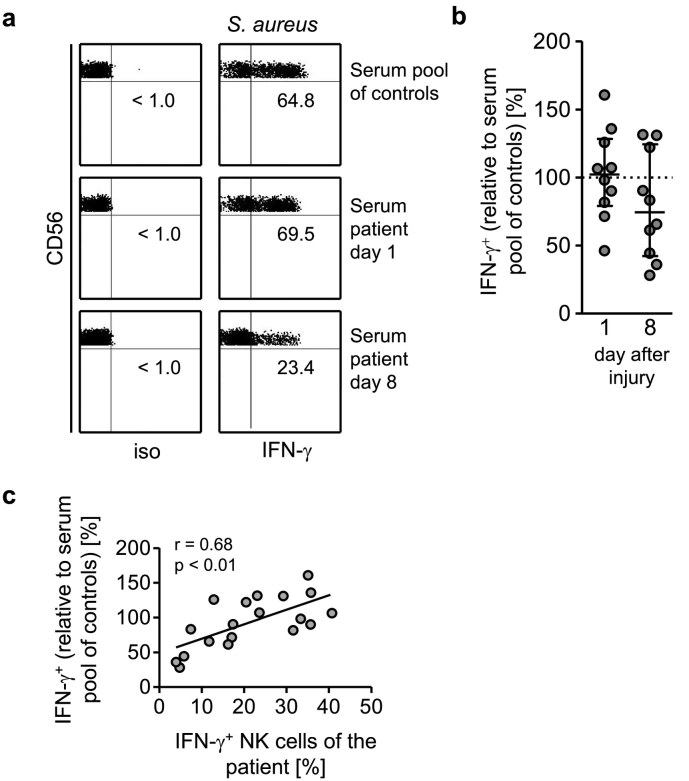

We selected patients who suffered life-threatening severe injury as a model for systemic inflammation with defined onset of the insult. As expected, increased levels of CRP and IL-6 were detected in the sera of the patients indicating ongoing inflammation (Suppl. Fig. 1). We analysed the capacity of CD56bright NK cells to produce IFN-γ upon exposure of PBMC to inactivated S. aureus bacteria. CD56bright NK cells from patients were significantly impaired in IFN-γ production as soon as 1 day after injury and remained suppressed throughout the whole observation period (Fig. 1a, b) which terminated at the day of discharge or of transfer to another hospital approximately 4 weeks later (Table 1). In contrast, the percentage of CD56bright NK cells did not differ throughout the observation period (Suppl. Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Suppressed capacity of CD56bright NK cells to secrete IFN-γ in response to S. aureus in systemic inflammation. PBMC from severely injured patients and from healthy control subjects (group 1; n = 10) were stimulated with heat-inactivated S. aureus in the presence of 10% autologous serum (a, b) or FCS (c). (A) Gating strategy of CD3−CD56bright NK cells and representative dot plots for a control subject and a patient 1 d after injury in the absence (none) or presence of S. aureus. Numbers indicate the percentage of IFN-γ+ cells among gated CD56bright NK cells. (b, c) Cumulative data of the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells from individual control subjects and patients in the presence of autologous serum (b) or FCS (c). For reasons of clarity the values obtained in the absence of S. aureus are not shown as they did not exceed 3%. Horizontal lines indicate the median and interquartile range. Statistical analyses were performed using the Friedman test (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01) for comparison within the group of patients and the Mann Whitney U test (## p < 0.01; ### p < 0.001) for comparison of patients with healthy controls. C, controls; D, day of discharge; iso, isotype control.

The expression of the stimulatory receptor NKG2D on CD56bright NK cells was transiently reduced on day 1 after injury and recovered thereafter (Suppl. Fig. 3a). In contrast, the expression of CD62L that is decreased upon NK cell activation did not differ at any time point (Suppl. Fig. 3b) [31]. Likewise, the expression of CD69 and CD25 did not change significantly after injury (Suppl. Fig. 3c, d).

The suppression of CD56bright NK cell function in systemic inflammation might be mediated by cell-intrinsic changes in PBMC and/or by changes in the microenvironment. When the autologous serum in the cell culture medium was replaced by FCS to generate a microenvironment free of human factors only the IFN-γ production on day 8 after injury significantly differed from control subjects (Fig. 1c). In contrast, the target cell-induced degranulation of CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells after injury (indicated by the expression of CD107a) was not diminished (Suppl. Fig. 4). Thus, systemic inflammation impairs the IFN-γ synthesis of CD56bright NK cells after stimulation of PBMC with S. aureus in both, intrinsic and extrinsic, manner.

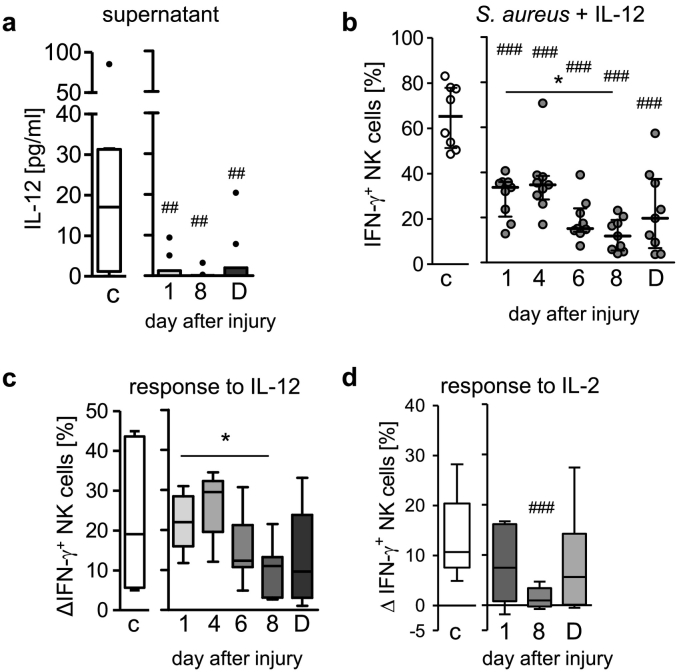

3.2. IL-12 does not restore the IFN-γ production by CD56bright NK cells

IL-12 is indispensable for the S. aureus-induced IFN-γ production by CD56bright NK cells and might play an essential role in the suppressed IFN-γ response in systemic inflammation [27]. Indeed, the patients' PBMC secreted less IL-12 after exposure to S. aureus in autologous serum (Fig. 2a). The addition of recombinant IL-12 increased the frequency of IFN-γ-producing CD56bright NK cells from healthy controls as well as from patients though the latter remained inferior in IFN-γ synthesis especially on day 8 (Fig. 2b). The recombinant IL-12-induced increase in the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells was significantly lower on day 8 than on day 1 after injury (Fig. 2c). The IFN-γ synthesis in CD56dim NK cells was similarly impaired after injury and was not restored by exogenous IL-12 though it was much weaker than in CD56bright NK cells (Suppl. Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 2.

Decreased responsiveness of CD56bright NK cells to IL-12 in systemic inflammation. PBMC from patients and from healthy control subjects (group 1; n = 10) were stimulated with inactivated S. aureus in the presence of 10% autologous serum. (a) Content of IL-12 in the supernatant. (b, c, d) PBMC were stimulated with inactivated S. aureus together with recombinant human IL-12 (n = 9) or IL-2. Percentage of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells upon supplementation with IL-12 (b). IL-12-induced (c) or IL-2-induced (d) increase in the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells expressed as the difference in the percentage of IFN-γ+ cells (Δ) obtained in the presence and absence of the respective cytokine. Data are shown as Tukey box plots. Horizontal lines indicate the median and interquartile range. Statistical analyses were performed using the Friedman test (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01) for comparison within the group of patients and the Mann Whitney U test (## p < 0.01; ### p < 0.001) for comparison of patients with healthy controls. C, controls; D, day of discharge.

Similarly, on day 8 after injury CD56bright NK cells only weakly responded to IL-2 (Fig. 2d) that otherwise led to an increased IFN-γ synthesis in line with previous reports [32]. Importantly, the patients' NK cells strongly responded to a potent cytokine cocktail consisting of IL-12, IL-18, and IL-15 (Suppl. Fig. 6). Thus, suppression of CD56bright NK cells in systemic inflammation is associated with a low responsiveness of the cells to IL-12 and IL-2.

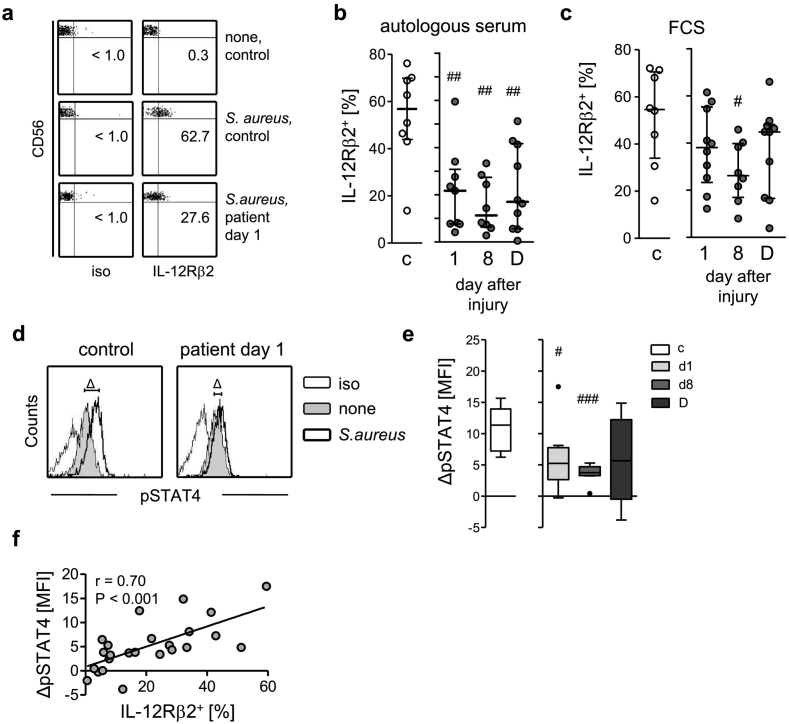

3.3. The impaired IFN-γ synthesis correlates with reduced IL-12Rβ2 expression and STAT4 phosphorylation

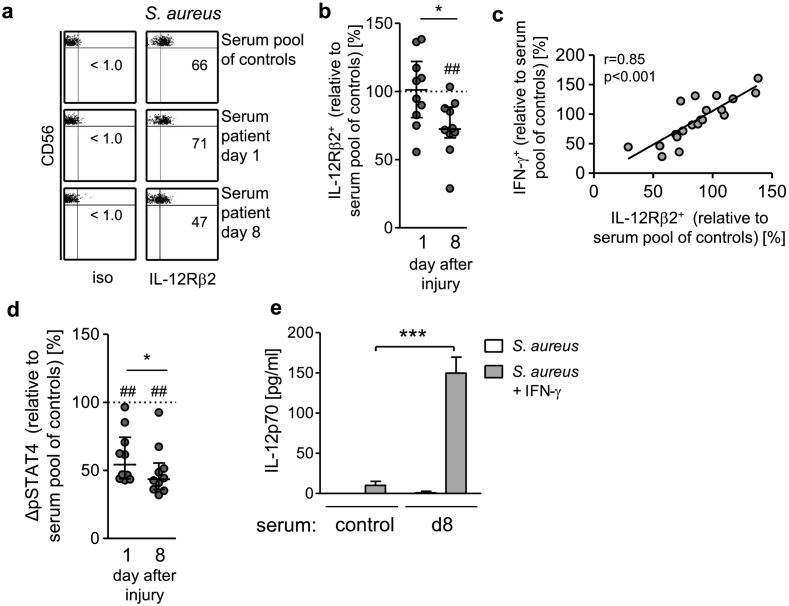

To evaluate the mechanisms underlying the reduced responsiveness of NK cells to IL-12 after injury, we determined their expression of the IL-12 receptor. CD56bright NK cells constitutively expressed the IL-12Rβ1 chain at comparable levels as did cells from healthy control subjects (Suppl. Fig. 3e) whereas the β2 chain was only expressed after exposure to S. aureus (Fig. 3a). In contrast to cells from controls, the patients' NK cells weakly expressed the IL-12Rβ2 chain throughout the whole observation period (Fig. 3b). In the absence of human serum, the suppressed IL-12Rβ2 expression was observed only on day 8 (Fig. 3c). CD56brightCD16+ NK cells display a more mature phenotype and expressed less IL-12Rβ2 (Suppl. Fig. 7a) than CD56brightCD16− NK cells [33]. The percentage of CD16+ cells among CD56bright NK cells did not differ between healthy control subjects and patients (Suppl. Fig. 7b) indicating that the reduced IL-12Rβ2 expression on CD56bright NK cells was not caused by an altered ratio of CD16+ and CD16− cells.

Fig. 3.

Reduced expression of IL-12Rβ2 and phosphorylation of STAT4 on/in CD56bright NK cells in systemic inflammation. PBMC from patients and from healthy control subjects (group 1; n = 10) were stimulated with inactivated S. aureus in the presence of autologous serum (a, b, d–f) or FCS (c). (a) Representative dot plots for staining of IL-12Rβ2 on CD56bright NK cells from a control subject and a patient 1 d after injury. Numbers indicate the percentage of positive cells. (b) Cumulative data of the percentage of IL-12Rβ2+ CD56bright NK cells in the presence of autologous serum. Note, due to insufficient cell numbers only n = 8–9 values were available for d1 and d8. (c) Percentage of IL-12Rβ2+ CD56bright NK cells in the presence of FCS (n = 8 on d8). (d) Representative histograms showing the phosphorylated STAT4 (pSTAT4) expression of unstimulated (none) and stimulated cells from one control subject and one patient on day 1 after injury. ΔMFI depicts the difference between the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of stimulated and unstimulated cells. (e) Cumulative data of the ΔMFI of CD56bright NK cells from controls and patients 1 or 8 d after injury (each n = 8) or at the day of discharge presented as Tukey box plots. Horizontal lines indicate the median and interquartile range. (f) Spearman correlation between the percentage of IL-12Rβ2+ cells (obtained from Fig. 3b) and ΔMFI pSTAT4 (obtained from Fig. 3e). Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann Whitney U test. #, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.01; ###, p < 0.001 versus controls. c, control subjects; D, day of discharge; iso, isotype control.

Engagement of the IL-12Rβ2 chain results in phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT4 that is essential for IFNG gene transcription in the nucleus [15,16]. Exposure of PBMC to S. aureus clearly increased the level of STAT4 phosphorylation in CD56bright NK cells from healthy controls but merely in NK cells 1 d and 8 d after injury (Fig. 3d, e). The expression of the IL-12Rβ2 chain on the cell surface significantly correlated with STAT4 phosphorylation (Fig. 3f). Likewise, CD56dim NK cells displayed reduced IL-12Rβ2 expression and STAT4 phosphorylation after severe injury (Suppl. Fig. 5c, d). Thus, the impaired capacity of CD56bright NK cells to produce IFN-γ in systemic inflammation is associated with suppressed IL-12Rβ2 expression and STAT4 phosphorylation.

3.4. The suppression of CD56bright NK cells is mediated by a circulating factor

The expression of IL-12Rβ2 and the production of IFN-γ by the patients' NK cells were at least partly restored when the stimulation of the cells occurred in the absence of the autologous serum except on day 8. Consequently, we hypothesized that serum acquired a suppressive capacity on NK cells after severe injury. To address this issue, cultures of PBMC from healthy volunteers were set up with pooled serum from the group of healthy control subjects (that served as reference value and was set as 100%) or with serum of individual patients from day 1 and day 8 after injury (termed ‘d1-serum’ and ‘d8-serum’, respectively, hereafter) and were stimulated with S. aureus. In the presence of d8-serum CD56bright NK cells appeared to produce less IFN-γ than in the presence of the corresponding d1-serum though this effect did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4a, b). The IFN-γ production of CD56bright NK cells from healthy donors in the presence of the serum of a given patient correlated with the IFN-γ production of the CD56bright NK cells of the same patient (Fig. 4c). Moreover, the patients' sera did not only suppress the IFN-γ production in response to S. aureus but also in response to other pathogen or pathogen-derived components, i.e. Listeria monocytogenes and viral single-stranded RNA (Suppl. Fig. 8).

Fig. 4.

Serum from injured patients interferes with the IFN-γ synthesis of CD56bright NK cells from healthy donors. PBMC from healthy donors were stimulated with inactivated S. aureus in the presence of 10% pooled sera from healthy control subjects or with serum from individual patients obtained on day 1 and day 8 after injury (group 1; n = 10). (a) Representative dot plots of intracellular staining for IFN-γ. Numbers indicate the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD56bright NK cells. (b) Cumulative data of the IFN-γ expression in the presence of individual sera. The value of the percentage of IFN-γ+ cells obtained in the presence of the pooled sera from controls was set as 100% (indicated as dotted line). Horizontal lines indicate the median and interquartile range. (c) Spearman correlation between the expression of IFN-γ of CD56bright NK cells of a patient on day 1 and day 8 in the presence of IL-12 (to correct for the insufficient release of IL-12 from PBMC; as shown in Fig. 2b) and the expression of IFN-γ of cells from healthy donors in the presence of the corresponding serum of the patient (as shown in Fig. 4b). iso, isotype control.

Further examination of the effect of the patients' sera on CD56bright NK cells from healthy donors revealed a significant decrease in the S. aureus-induced expression of IL-12Rβ2 by d8-serum in comparison to d1-serum or to the pooled serum from healthy control subjects (Fig. 5a, b). Moreover, the expression of IL-12Rβ2 clearly correlated with the production of IFN-γ (Fig. 5c). Remarkably, the d1-sera and even more the d8-sera interfered with the S. aureus-induced phosphorylation of STAT4 (Fig. 5d). There was no correlation between STAT4 phosphorylation and IFN-γ production (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

The suppressive effect of the patients' sera on CD56bright NK cell-derived IFN-γ synthesis correlates with a diminished IL-12Rβ2 expression. PBMC from healthy donors were stimulated with inactivated S. aureus in the presence of 10% pooled sera from healthy control subjects or with serum from individual patients obtained on day 1 and day 8 after injury (group 1; n = 10). (a) Representative dot plots of IL-12Rβ2 staining. Numbers indicate the percentage of IL-12Rβ2+ CD56bright NK cells. (b) Cumulative data of the IL-12Rβ2 expression in the presence of individual sera. The value of the percentage of IL-12Rβ2+ CD56bright NK cells obtained in the presence of the pooled sera from healthy control subjects was set as 100% (indicated as dotted line). (c) Spearman correlation between the expression of IL-12Rβ2 (as shown in Fig. 5b) and the production of IFN-γ (as shown in Fig. 4b). (d) Cumulative data of the activation of STAT4 (pSTAT4) in the presence of individual sera. The value of the ΔMFI in CD56bright NK cells obtained in the presence of the pooled sera from control subjects was set as 100% (indicated as dotted line). Horizontal lines indicate the median and interquartile range of individual values. Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. (e) Isolated monocytes from healthy donors were cultured in the pooled serum from control subjects or from patients 8 d after injury (group 1). The cells were stimulated with inactivated S. aureus alone or together with recombinant IFN-γ and the release of IL-12 was quantified. Bars show mean + SD of triplicate cultures and are representative for 3 separate experiments. Statistically significant differences between control sera and the patients' sera were tested using unpaired Student's t-test. ***, p < 0.001*, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.01 versus serum pool of control subjects.

Next, we asked whether the patients' sera impaired monocytes for IL-12 synthesis that in turn led to a decreased IFN-γ response by CD56bright NK cells. In line with a previous study [20] no IL-12 was released by isolated monocytes from healthy donors after exposure to S. aureus alone. Remarkably, when the monocytes were boosted by the addition of recombinant IFN-γ they secreted much more IL-12 when cultured in the presence of the patients' sera (Fig. 5e). Thus, a circulating factor inhibits the IL-12/IFN-γ axis in CD56bright NK cells after severe injury.

3.5. Signalling through TGF-β receptor I contributes to NK cell suppression

IL-10 and TGF-β are regulatory cytokines that are known to limit the IFN-γ production by NK cells and might contribute to the suppression of CD56bright NK cells in systemic inflammation [34,35]. Blocking of IL-10 during stimulation of PBMC with S. aureus slightly increased the IFN-γ production of CD56bright NK cells from controls but it was ineffective in case of the patients' NK cells (data not shown).

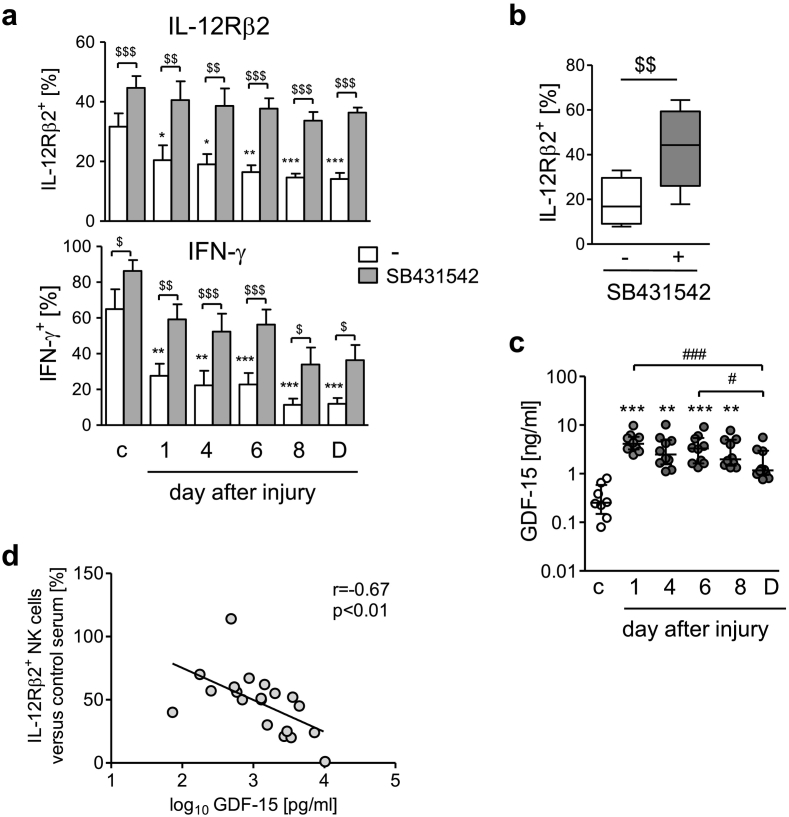

We investigated the potential role of members of the TGF-β family using SB431542, a small molecule inhibitor of the TGF-βRI (also known as activin-like kinase (ALK) 5). To enable parallel analysis, the sera from all patients were pooled for each time point after injury. The expression of IL-12Rβ2 and the production of IFN-γ by CD56bright NK cells were suppressed by each pool of the patients' sera in a TGF-βRI-dependent manner (Fig. 6a). The minor effect of SB431542 on NK cells in the presence of serum from healthy control subjects might be explained by the inhibition of the autoregulatory activity of NK cell-derived TGF-β [36]. Analyses of the patients' individual sera of day 6 after injury confirmed the increased IL-12Rβ2 expression upon inhibition of the TGF-βRI (Fig. 6b). Alternative inhibition of ALK5 by GW788388 likewise restored the IFN-γ synthesis of CD56bright NK cells in the presence of the patients' sera (Suppl. Fig. 9). Importantly, the patients' sera did not generally suppress the function of NK cells as the activity for degranulation remained unchanged (Suppl. Fig. 10).

Fig. 6.

Signalling through TGF-βRI mediates the suppressive effect of the patients' sera on CD56bright NK cells. (a) Cultures of PBMC from healthy donors were set up in 2% pooled sera from patients obtained at different time points after injury or from healthy control subjects (group 1). PBMC were stimulated with inactivated S. aureus in the presence of SB431542 (inhibitor of the TFG-βRI) or of its solvent (−) and the expression of the IL-12Rβ2 and of IFN-γ on/in CD56bright NK cells was determined. Data show mean + SEM of n = 5 independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were tested using paired Student's t-test. (b) PBMC from healthy donors were set up in sera from individual patients 6 d after injury (group 1; n = 10) and were stimulated with S. aureus in the presence of SB431542 or its solvent. Tukey box plots show the cumulative data on the expression of IL-12Rβ2 on CD56bright NK cells. Statistical differences were tested using Wilcoxon signed rank test. (c) Concentration of GDF-15 in the sera of individual patients (n = 10) and healthy control subjects (group 1). Horizontal lines indicate the median and interquartile range of individual values. (d) Spearman correlation between the concentration of GDF-15 in the sera of individual patients (group 2; day 5 serum; n = 19) and the expression of IL-12Rβ2 (normalized to pooled serum from healthy control subjects that was set as 100%) on CD56bright NK cells from healthy donors after exposure to the sera as described above. $, p < 0.05; $$, p < 0.01; $$$, p < 0.001. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus control serum. #, p < 0.05; ###, p < 0.001.

The concentration of TGF-β1 as the major ligand of the TGF-βRI in the patients' sera did not remarkably exceed the levels found in the sera from control subjects at any time point after injury (Suppl. Fig. 11). GDF-15, also known as macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1, is a distant member of the TGF-β family and may signal through the TGF-βRI [[37], [38], [39]]. The concentration of GDF-15 in the serum of healthy control subjects was within the normal range (<1200pg/ml). We found extremely high levels of GDF-15 in the patients' sera as soon as 1 d after injury that exceeded the levels in sera from healthy control subjects by almost 20-fold and remained high at least until day 8 (Fig. 6c). Correlation analyses indicated an inverse relationship between the content of GDF-15 in the serum and the expression of the IL-12Rβ2 (Fig. 6d) and IFN-γ (Suppl. Fig. 12) of CD56bright NK cells from healthy donors upon exposure to this serum and stimulation with S. aureus.

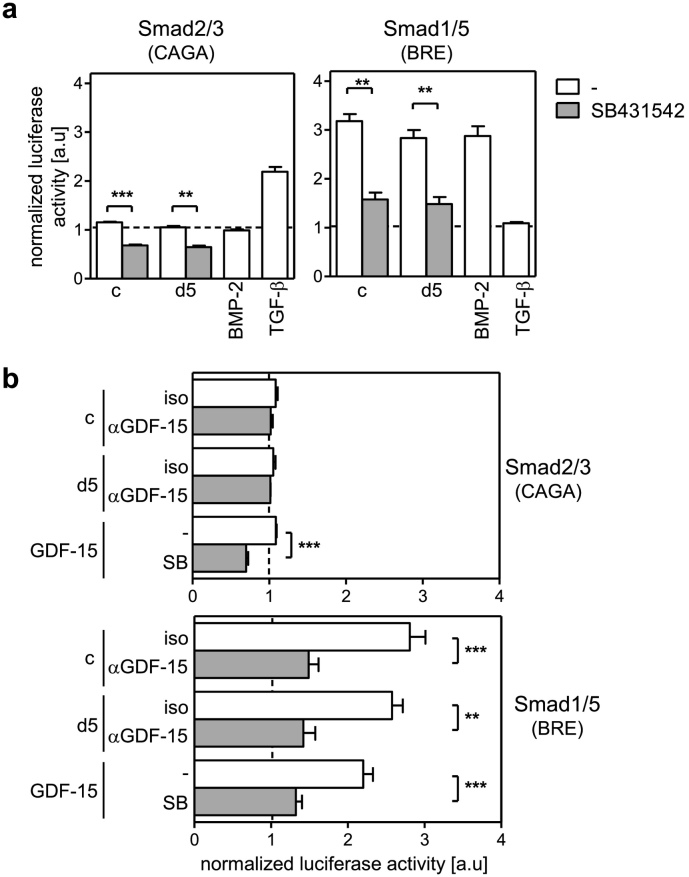

To get insight into the signalling of GDF-15 in PBMC upon their exposure to the sera, the canonical pathway of the TGF-βRI involving the activation of Smad2/3 and/or Smad 1/5/8 was investigated using transfection with specific reporter constructs. According to Fig. 6a the reversal of CD56bright NK cell suppression by inhibition of the TGF-βRI was most prominent for sera obtained on day 4 and 6 after injury. Therefore, d5-serum was selected and applied to the reporter assays. The sera from healthy control subjects and from patients induced the activation of Smad 1/5 that was almost completely blocked in the presence of the TGF-βRI inhibitor (Fig. 7a). In contrast, the sera did not cause the activation of Smad2/3 (Fig. 7a). Prior depletion of GDF-15 from the serum clearly reduced the activation of Smad1/5 (Fig. 7b). Accordingly, recombinant GDF-15 triggered the Smad1/5 reporter construct in a TGF-βRI-dependent manner but not the Smad2/3 reporter construct (Fig. 7b). Moreover, intracellular flow cytometry revealed an increased expression of phosphorylated Smad1/8 in CD56bright NK cells after exposure to the patients' sera (Suppl. Fig. 13).

Fig. 7.

GDF-15 in the serum signals through the canonical TGF-βRI pathway in leukocytes. PBMC from healthy donors were transfected with CAGA or BRE reporter constructs indicating activation of Smad2/3 and Smad1/5, respectively. (a) PBMC were exposed to pooled sera from healthy control subjects or to pooled sera from patients obtained 5 d after injury each in the absence or presence of SB431542 (inhibitor of the TFG-βRI). Recombinant TGF-β and BMP-2 served as positive controls for the activation of Smad2/3 and Smad1/5, respectively. (b) Sera were depleted of GDF-15 (αGDF-15) or were treated with an isotype control antibody (iso) before transfer to the transfected PBMC. Recombinant GDF-15 was added to PBMC in the absence or presence of SB431542 (SB). The luciferase activity representing binding of Smad to the reporter constructs was determined. The luciferase activity in PBMC in the absence of sera or recombinant proteins was set as 1 and was used to normalize all values. Bar graphs show the mean + SEM of n = 5 independent experiments. Significant differences were analysed using the paired Student's t-test. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. c, control sera; a.u., arbitrary units.

The sera that had been depleted of GDF-15 were additionally applied to PBMC to address the IL-12Rβ2 expression. However, we could not draw any conclusions from these experiments since NK cells failed to express the IL-12Rβ2 chain upon stimulation with S. aureus when the serum had been exposed to the isotype control antibodies (data not shown). Thus, GDF-15 circulates at high levels during systemic inflammation, activates Smad1/5 downstream of the TGF-βRI, and is linked with the suppressive activity of the patients' sera on CD56bright NK cells.

3.6. Early elevated levels of GDF-15 are associated with critical illness

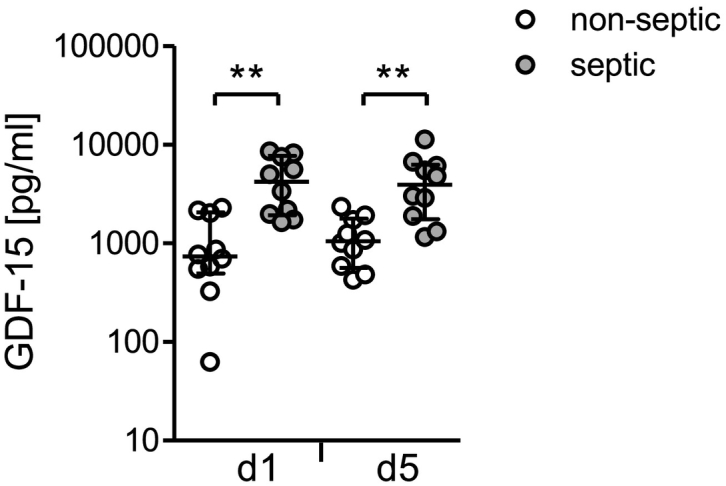

In order to gather information on the clinical relevance of the high levels of circulating GDF-15 in systemic inflammation, we analysed sera of an additional group of patients on day 1 and 5 after injury. These patients were free of signs of sepsis until day 5 but 50% of them developed a septic complication later on (the median time point of sepsis diagnosis was 9 d after injury; see Table 1). Remarkably, as soon as 1 d after injury, patients who later developed sepsis (beyond day 5) displayed significantly higher levels of GDF-15 than those who remained free of septic complications (Fig. 8). Moreover, the GDF-15 levels on day 1 significantly correlated with the degree of morbidity estimated by the maximal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score during the first 5 days (Table 2). No significant correlation of the GDF-15 concentration with the age or with the injury severity of the patients was detected (Table 2). Thus, GDF-15 is associated with enhanced morbidity and risk for septic complication in systemic inflammation.

Fig. 8.

Increased levels of GDF-15 early after injury circulate in patients who later develop a septic complication. The concentration of GDF-15 was determined in sera obtained from patients (group 3; n = 20) 1 d and 5 d after severe injury. The graph depicts individual values from patients who remained free (n = 10; non-septic) or developed sepsis beyond day 6 after injury (n = 10; septic). Horizontal lines indicate the median and interquartile range. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann Whitney U test. **, p < 0.01.

Table 2.

Circulating GDF-15 levels on day 1 after injury correlate with morbidity.

| Age | ISS | SOFAmax | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman r | −0.117 | 0.130 | 0.658 |

| p value | ns | ns | p < 0.0001 |

ns, not significant.

The correlation of the concentration of GDF-15 in the serum of the patients of all groups (n = 49) 1 d after injury with the age, the injury severity score (ISS), and the maximal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFAmax) score during the first 5 d was tested using Spearman correlation analysis.

4. Discussion

The present study shows for the first time that in parallel to ongoing systemic inflammation circulating CD56bright NK cells display a state of deactivation in terms of IFN-γ synthesis that persists for several weeks. Deactivation or exhaustion of NK cells is a well-known phenomenon in cancer. In that case CD56dim NK cells are unable to recognize and kill tumour cells due to insufficient cytotoxicity, cytokine production, and increased expression of inhibitory receptors such as PD-1 [40]. In contrast, degranulation of NK cells was not reduced after severe injury suggesting that diverse pathomechanisms drive the modulation of NK cells during systemic inflammation and in cancer.

In line with a previous study PBMC from severely injured patients released reduced levels of IL-12 after exposure to S. aureus, a finding that has been ascribed to the deactivation of monocytes [41,42]. Moreover, we identified a disturbed expression of the β2 chain of the IL-12R and downstream STAT4 phosphorylation on/in CD56bright NK cells that was associated with impaired IFN-γ synthesis. A selective disorder of the IL-12 signalling pathway might explain why injury did not interfere with degranulation that is triggered by synergistic engagement of activating receptors such as NKG2D in a cytokine-independent manner. Since IFN-γ is required to enable robust IL-12 synthesis by monocytes we assume that both the inappropriate IL-12 secretion by monocytes and the impaired expression of the IL-12Rβ2 chain on NK cells generate a negative feedback loop that further aggravates the dysfunction of accessory cells and CD56bright NK cells during systemic inflammation. Consequently, NK cells that are recruited from the circulation into the infected tissue or into draining lymphoid organs in case of an infectious insult might be unable to support the elimination of the pathogens due to their insufficient IFN-γ production. This assumption is supported by our previous work on a clinically relevant murine model of sterile skeletal muscle injury showing that NK cells are recruited to the lymph node draining the site of injury and interfere with the development of T helper cell type 1 responses [43]. Though, it remains to be elucidated whether the NK cells in this mouse model likewise display an insufficient formation of IFN-γ and/or even acquire regulatory activity through the release of IL-10 [[44], [45], [46]].

Due to the limited sample volume that could be obtained from the patients we focused on the production of IFN-γ as a relevant mediator in the defence against bacterial infections. Therefore, we cannot rule out that after severe injury other mediators such as IL-10 are expressed at enhanced levels while the production of IFN-γ is suppressed, a state that may be termed ‘reprogramming’ rather than ‘deactivation’. Seshadri et al. recently reported an initially decreased but later increased synthesis of TNF-β in NK cells of injured patients in response to Streptococcus pneumoniae as compared with cells from healthy donors [47]. These temporal changes in cytokine synthesis might reflect signs of reprogramming of NK cells after severe injury. In contrast to our findings, the authors did not observe a profound suppression of IFN-γ synthesis. It is possible that due to the lack of discrimination between NK cell subtypes in that study the function of the relatively small population of CD56bright NK cells was blurred by the weak IFN-γ production of CD56dim NK cells.

The risk of patients for infectious complications is known to peak around day 8 after injury while CD56bright NK cells were similarly suppressed in IFN-γ synthesis throughout the whole observation period [48]. Thus, at the first glance the early suppression of NK cell-derived IFN-γ synthesis did not seem to correlate with the delayed onset of infection. We dissected cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic mechanisms that induced qualitative differences in the suppression of CD56bright NK cells. The intrinsic effect became apparent when the cells were analysed in the absence of autologous serum. In this human serum-free microenvironment only CD56bright NK cells from patients 8 d after injury were significantly impaired in IFN-γ synthesis and IL-12Rβ2 expression suggesting that the cells had acquired a state of exhaustion. But unlike NK cells in tumours, the function of CD56bright NK cells at that time point could not be restored by the stimulatory cytokines IL-2 or IL-12 [40]. A global inhibition of the IFN-γ synthesis in the patients' NK cells could be excluded as they strongly responded to a potent cytokine cocktail.

Our previous findings that purified NK cells from severely injured patients do not release IFN-γ after stimulation with IL-12/IL-18 support our hypothesis of intrinsic changes in NK cells 8 d after injury [24]. As mentioned above, monocytes are impaired in IL-12 synthesis after severe injury and might further aggravate the suppression of NK cells [42].

The association between the expression of the IL-12Rβ2 chain and the IFN-γ production implies that the IL-12Rβ2 chain represents a check-point in the activity of CD56bright NK cells in systemic inflammation. The promoter of the IL-12RB2 gene contains several binding sites for diverse activating or repressing transcription factors including T-bet, STAT4, suppressor of cytokine signalling (SOCS) 3, and NFATc2 [[49], [50], [51], [52]]. The binding affinity of some of these transcriptions factors depends on genetic variants and influences the transcriptional activity of the IL-12RB2 gene [53]. Moreover, epigenetic modifications of the IL-12RB2 locus have been reported [54]. Any of these regulatory mechanisms should be considered in future studies on the mechanisms that cause the modulation of CD56bright NK cells in systemic inflammation.

In addition, we recognized a decisive role of the microenvironment in the modulation of CD56bright NK cells after severe injury. When exposed to the patients' sera, CD56bright NK cells from healthy donors displayed a similar phenotype as CD56bright NK cells from patients with regard to inhibition of IL-12Rβ2 chain expression, STAT4 phosphorylation, and IFN-γ production. In contrast, the patients' sera did not affect the activity for degranulation of NK cells arguing against a global inhibition of NK cell function. Importantly, the patients' sera did not disturb but rather increased the capacity of monocytes to produce IL-12 in response to S. aureus for so far unknown reasons. Considering its relevance in the activation of NK cells we, thus, exclude that an insufficient production of IL-12 by monocytes contributed to the inhibitory effect of the sera on CD56bright NK cells.

With regard to the enhanced incidence of nosocomial infections in patients around day 8 after severe injury we propose that the delayed appearance of the exhaustion-like behaviour of NK cells together with the sustained inhibitory activity of the serum worsens the resistance to invading pathogens [48]. In consequence, the restoration of the IL-12Rβ2 expression on CD56bright NK cells during systemic inflammation might represent a therapeutic target to improve immune defence mechanisms.

The suppressive effect of the patients' sera on the IL-12Rβ2 expression of CD56bright NK cells was largely mediated by ALK5/TGF-βRI. In terms of IFN-γ synthesis, the inhibition of the TGF-βRI did not completely restore the function of CD56bright NK cells indicating that additional inhibitory signalling pathway(s) might be triggered by so far unknown factors in the patients' sera. In line with previous reports we did not detect significantly elevated levels of the functionally active form of TGF-β in the serum of the patients [55]. In search of an alternative agonist of the TGF-βRI we found strongly increased levels of circulating GDF-15 within 24 h after severe injury that persisted for at least 8 d and thus resembled the kinetics of IL-6 though at much higher concentration. GDF-15 is considered to limit inflammation while elevated levels of GDF-15 are associated with morbidity such as atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and obesity [37,38,[56], [57], [58], [59], [60]]. Though, mechanistic studies on GDF-15 in human diseases are rare and have not considered NK cells so far. Here, we provide first evidence for an inverse correlation of GDF-15 with the expression of IL-12Rβ2 and IFN-γ of CD56bright NK cells suggesting that GDF-15 is a major player in the extrinsic suppression of NK cells in systemic inflammation. In this context we additionally examined the effect of GDF-15-free sera on purified NK cells that were stimulated with IL-12 and IL-18. However the expression of IL-12Rβ2 on NK cells did not increase in the absence of GDF-15 (Suppl. Fig. 14a) suggesting that the stimulation with cytokines did not appropriately mimic the activation of NK cells after exposure of PBMC to S. aureus. When cultured in the absence of human serum, the addition of recombinant human GDF-15 impaired the expression of IL-12Rβ2 on NK cells from some but not all healthy donors after stimulation with IL-12 and IL-18 (Suppl. Fig. 14b). One explanation could be that GDF-15 requires additional factors in human serum to efficiently mediate NK cell suppression.

GDF-15 triggers diverse signalling pathways including the canonical and non-canonical TGF-βRI pathway in leukocytes and tumour cells and the more recently discovered GDNF-family receptor α-like (GFRAL)-dependent pathway in neurons indicating the large functional plasticity of GDF-15 [56,[61], [62], [63], [64], [65]]. We show here that GDF-15 in human serum as well as human recombinant GDF-15 activated Smad1/5 but not Smad2/3 in PBMC in a TGF-βRI-dependent manner. These findings imply that the Smad2/3 pathway did not play a role in the TGF-βRI-mediated suppression of NK cells by the patients' serum.

Unexpectedly, the patients' serum triggered Smad1/5 to a similar degree as did the serum from healthy control subjects although both strongly differed in their content of GDF-15. But both responses were dependent on GDF-15 as its depletion each abolished Smad1/5 signalling. Therefore, we cannot finally exclude so far unrecognized limitations of the reporter assay regarding the sensitivity or the linearity of detection that might explain the discrepancy between GDF-15 content and the generated signal. An alternative explanation is that components downstream of Smad1/5 (e.g. the balance of co-Smads and inhibitory Smads) or a non-canonical TGF-βRI pathway were responsible for the diverse activities of both sera [66,67]. Nevertheless, this open question does not weaken our conclusion that GDF-15 was the major driver of serum-induced activation of TGF-βRI signalling. We observed an increase in phosphorylated Smad1/8 in CD56bright NK cells after exposure to the patients' sera. The promoter of the human IL12RB2 gene contains several putative binding sites for Smad1/8 (Suppl. Fig. 15). Therefore, activated Smad1/8 might directly regulate the expression of IL-12Rβ2. However, we cannot exclude indirect effects on the expression of IL-12Rβ2 on NK cells through the activation of Smad1/8 in accessory cells. Thus, the precise link between TGF-βRI-induced activation of Smad1/8 and IL-12Rβ2 expression on NK cells upon exposure to the patients' serum remains to be addressed in further studies.

The concentration of GDF-15 in the serum was extraordinarily high after severe injury and reached values that are otherwise found in patients with metastatic colon cancer or with sepsis [68,69]. In this context it is intriguing to speculate that GDF-15 also contributes to the above mentioned suppression of NK cells in patients suffering from systemic inflammation due to sepsis [23]. Thus, the considerable amount of circulating GDF-15 during systemic inflammation might explain the generally increased risk for nosocomial infections despite the large heterogeneity of underlying diseases. Whether GDF-15 is the cause or the consequence of morbidity in humans is still unclear. In case of the present study the level of circulating GDF-15 did not correlate with the extent of tissue injury. The question ‘where’ and ‘why’ GDF-15 was released at these substantial levels after severe tissue damage remains open.

A previous study on a Swedish male cohort demonstrated a large interindividual variation of the GDF-15 concentration in the blood and identified GDF-15 as a predictor for all-cause mortality over 14 years [70]. We observed that patients who later suffered from septic complications displayed higher GDF-15 levels in the blood as soon as 1 d after severe injury than patients who remained free of a septic episode. Due to the lack of serum samples obtained before severe injury it remains unclear whether patients displaying high GDF-15 levels represent individuals with high basal levels of this mediator. We propose that GDF-15 that circulates during systemic inflammation may interfere with the protective immune response to bacterial infections through the extrinsic suppression of CD56bright NK cells. Importantly, the quantification of GDF-15 in the blood early after severe injury might help to identify patients with enhanced risk for septic complications who might be stratified for specific therapies.

In summary, during systemic inflammation TGF-βRI-mediated signals induce a long-lasting suppression of the IL-12/IFN-γ axis in CD56bright NK cells that might interfere with the protective role of NK cells in the immune defence against invading pathogens. We identified GDF-15 not only as an agonist of the TGF-βRI and thereby as a therapeutic target to restore NK cell function in systemic inflammation but moreover as a potential early marker for patients who are prone to nosocomial infections during the course of disease.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff of the intensive care unit for support in blood withdrawal. We thank the patients, their relatives, and healthy donors for providing their consent to participate in this study.

Funding sources

The study was funded by the Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery, University Hospital Essen. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

H. Kleinertz, M. Hepner-Schefczyk, S. Ehnert, M. Claus, and L. Boller designed and performed the experiments, analysed, and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; R. Halbgebauer, M. Huber-Lang, P. Cinelli, C. Kirschning, S. Flohé, A. Sander, C. Waydhas, S. Vonderhagen, M. Jäger, and M. Dudda provided material of the patients and contributed to the study design; C. Watzl interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; S.B. Flohé supervised the study, designed the experiments, analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.018.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Lord J.M., Midwinter M.J., Chen Y.F. The systemic immune response to trauma: an overview of pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet. 2014;384:1455–1465. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timmermans K., Kox M., Scheffer G.J., Pickkers P. Danger in the intensive care unit: DAMPS in critically ill patients. Shock. 2016;45:108–116. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horiguchi H., Loftus T.J., Hawkins R.B. Innate immunity in the persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome and its implications for therapy. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:595. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huber-Lang M., Lambris J.D., Ward P.A. Innate immune responses to trauma. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:327–341. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide. 2011. http://appswhoint/iris/bitstream/10665/80135/1/9789241501507_engpdf

- 7.Tsuchiya Y., Sawada S., Yoshioka I. Increased surgical stress promotes tumor metastasis. Surgery. 2003;133:547–555. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura F., Shimizu H., Yoshidome H., Ohtsuka M., Miyazaki M. Immunosuppression following surgical and traumatic injury. Surg. Today. 2010;40:793–808. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fullerton J.N., Gilroy D.W. Resolution of inflammation: a new therapeutic frontier. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2016;15:551–567. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao W., Mindrinos M.N., Seok J. A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:2581–2590. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodoen M.B., Lanier L.L. Natural killer cells as an initial defense against pathogens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006;18:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caligiuri M.A. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112:461–469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poli A., Michel T., Theresine M., Andres E., Hentges F., Zimmer J. CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: an important NK cell subset. Immunology. 2009;126:458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo S.J., Dighe A.S., Gubler U., Murphy K.M. Regulation of the interleukin (IL)-12R beta 2 subunit expression in developing T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:817–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thierfelder W.E., van Deursen J.M., Yamamoto K. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature. 1996;382:171–174. doi: 10.1038/382171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson N.G., Szabo S.J., Weber-Nordt R.M. Interleukin 12 signaling in T helper type 1 (Th1) cells involves tyrosine phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)3 and Stat4. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1755–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michel T., Hentges F., Zimmer J. Consequences of the crosstalk between monocytes/macrophages and natural killer cells. Front. Immunol. 2013;3:403. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas R., Yang X. NK-DC crosstalk in immunity to microbial infection. J. Immunol. Res. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/6374379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarhan D., Palma M., Mao Y. Dendritic cell regulation of NK-cell responses involves lymphotoxin-alpha, IL-12, and TGF-beta. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015;45:1783–1793. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haller D., Serrant P., Granato D., Schiffrin E.J., Blum S. Activation of human NK cells by staphylococci and lactobacilli requires cell contact-dependent costimulation by autologous monocytes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2002;9:649–657. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.3.649-657.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloss M., Decker P., Baltz K.M. Interaction of monocytes with NK cells upon toll-like receptor-induced expression of the NKG2D ligand MICA. J. Immunol. 2008;181:6711–6719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryceson Y.T., March M.E., Ljunggren H.G., Long E.O. Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood. 2006;107:159–166. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F., Parlato M., Philippart F., Misset B., Cavaillon J.M., Adib-Conquy M. Toll-like receptors expression and interferon-gamma production by NK cells in human sepsis. Crit. Care. 2012;16:R206. doi: 10.1186/cc11838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui R., Rekasi H., Hepner-Schefczyk M. Human mesenchymal stromal/stem cells acquire immunostimulatory capacity upon cross-talk with natural killer cells and might improve the NK cell function of immunocompromised patients. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016;7:88. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rangel-Frausto M.S., Pittet D., Costigan M., Hwang T., Davis C.S., Wenzel R.P. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA. 1995;273:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rittirsch D., Schoenborn V., Lindig S. Improvement of prognostic performance in severely injured patients by integrated clinico-transcriptomics: a translational approach. Crit. Care. 2015;19:414. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1127-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinhardt R., Pohlmann S., Kleinertz H., Hepner-Schefczyk M., Paul A., Flohé S.B. Invasive surgery impairs the regulatory function of human CD56 bright natural killer cells in response to Staphylococcus aureus. Suppression of interferon-gamma synthesis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dennler S., Itoh S., Vivien D., ten Dijke P., Huet S., Gauthier J.M. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF beta-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J. 1998;17:3091–3100. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korchynskyi O., ten Dijke P. Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:4883–4891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehnert S., Baur J., Schmitt A. TGF-beta1 as possible link between loss of bone mineral density and chronic inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frey M., Packianathan N.B., Fehniger T.A. Differential expression and function of L-selectin on CD56bright and CD56dim natural killer cell subsets. J. Immunol. 1998;161:400–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K.S., Frank D.A., Ritz J. Interleukin-2 enhances the response of natural killer cells to interleukin-12 through up-regulation of the interleukin-12 receptor and STAT4. Blood. 2000;95:3183–3190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beziat V., Duffy D., Quoc S.N. CD56brightCD16+ NK cells: a functional intermediate stage of NK cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2011;186:6753–6761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellone G., Aste-Amezaga M., Trinchieri G., Rodeck U. Regulation of NK cell functions by TGF-beta 1. J. Immunol. 1995;155:1066–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aste-Amezaga M., Ma X., Sartori A., Trinchieri G. Molecular mechanisms of the induction of IL-12 and its inhibition by IL-10. J. Immunol. 1998;160:5936–5944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meadows S.K., Eriksson M., Barber A., Sentman C.L. Human NK cell IFN-gamma production is regulated by endogenous TGF-beta. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1020–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bootcov M.R., Bauskin A.R., Valenzuela S.M. MIC-1, a novel macrophage inhibitory cytokine, is a divergent member of the TGF-beta superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997;94:11514–11519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Artz A., Butz S., Vestweber D. GDF-15 inhibits integrin activation and mouse neutrophil recruitment through the ALK-5/TGF-betaRII heterodimer. Blood. 2016;128:529–541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-696617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C., Wang J., Kong J. GDF15 promotes EMT and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:860–872. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bi J., Tian Z. NK cell exhaustion. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:760. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ertel W., Keel M., Neidhardt R. Inhibition of the defense system stimulating interleukin-12 interferon-gamma pathway during critical illness. Blood. 1997;89:1612–1620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spolarics Z., Siddiqi M., Siegel J.H. Depressed interleukin-12-producing activity by monocytes correlates with adverse clinical course and a shift toward Th2-type lymphocyte pattern in severely injured male trauma patients. Crit. Care Med. 2003;31:1722–1729. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063579.43470.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wirsdörfer F., Bangen J.M., Pastille E., Hansen W., Flohé S.B. Breaking the co-operation between bystander T-cells and natural killer cells prevents the development of immunosuppression after traumatic skeletal muscle injury in mice. Clin. Sci. 2015;128:825–838. doi: 10.1042/CS20140835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin-Fontecha A., Thomsen L.L., Brett S. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perona-Wright G., Mohrs K., Szaba F.M. Systemic but not local infections elicit immunosuppressive IL-10 production by natural killer cells. Cell. Host. Microbe. 2009;6:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark S.E., Filak H.C., Guthrie B.S. Bacterial manipulation of NK cell regulatory activity increases susceptibility to listeria monocytogenes infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seshadri A., Brat G.A., Yorkgitis B.K. Phenotyping the immune response to trauma: a multiparametric systems immunology approach. Crit. Care Med. 2017;45:1523–1530. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoover L., Bochicchio G.V., Napolitano L.M. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome and nosocomial infection in trauma. J. Trauma. 2006;61:310–316. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000229052.75460.c2. [discussion 6-7] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Afkarian M., Sedy J.R., Yang J. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naive CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:549–557. doi: 10.1038/ni794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto K., Yamaguchi M., Miyasaka N., Miura O. SOCS-3 inhibits IL-12-induced STAT4 activation by binding through its SH2 domain to the STAT4 docking site in the IL-12 receptor beta2 subunit. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;310:1188–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jamil K.M., Hydes T.J., Cheent K.S. STAT4-associated natural killer cell tolerance following liver transplantation. Gut. 2017;66:352–361. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Rietschoten J.G., Smits H.H., van de Wetering D. Silencer activity of NFATc2 in the interleukin-12 receptor beta 2 proximal promoter in human T helper cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:34509–34516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato-Kogoe N., Ohyama H., Okano S. Functional analysis of differences in transcriptional activity conferred by genetic variants in the 5′ flanking region of the IL12RB2 gene. Immunogenetics. 2016;68:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s00251-015-0882-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LaMere S.A., Thompson R.C., Meng X., Komori H.K., Mark A., Salomon D.R. H3K27 methylation dynamics during CD4 T cell activation: regulation of JAK/STAT and IL12RB2 expression by JMJD3. J. Immunol. 2017;199:3158–3175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Majetschak M., Borgermann J., Waydhas C., Obertacke U., Nast-Kolb D., Schade F.U. Whole blood tumor necrosis factor-alpha production and its relation to systemic concentrations of interleukin 4, interleukin 10, and transforming growth factor-beta1 in multiply injured blunt trauma victims. Crit. Care Med. 2000;28:1847–1853. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ratnam N.M., Peterson J.M., Talbert E.E. NF-kappaB regulates GDF-15 to suppress macrophage surveillance during early tumor development. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:3796–3809. doi: 10.1172/JCI91561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Jager S.C., Bermudez B., Bot I. Growth differentiation factor 15 deficiency protects against atherosclerosis by attenuating CCR2-mediated macrophage chemotaxis. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:217–225. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adela R., Banerjee S.K. GDF-15 as a target and biomarker for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases: a translational prospective. J. Diabetes Res. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/490842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsai V.W., Lin S., Brown D.A., Salis A., Breit S.N. Anorexia-cachexia and obesity treatment may be two sides of the same coin: role of the TGF-b superfamily cytokine MIC-1/GDF15. Int. J. Obes. (2005) 2016;40:193–197. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Corre J., Hebraud B., Bourin P. Concise review: growth differentiation factor 15 in pathology: a clinical role? Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2013;2:946–952. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Y.L., Chang J.T., Lee L.Y. GDF15 contributes to radioresistance and cancer stemness of head and neck cancer by regulating cellular reactive oxygen species via a SMAD-associated signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:1508–1528. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu J., Kimball T.R., Lorenz J.N. GDF15/MIC-1 functions as a protective and antihypertrophic factor released from the myocardium in association with SMAD protein activation. Circ. Res. 2006;98:342–350. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202804.84885.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mullican S.E., Lin-Schmidt X., Chin C.N. GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and the ligand promotes weight loss in mice and nonhuman primates. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1150–1157. doi: 10.1038/nm.4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang L., Chang C.C., Sun Z. GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and is required for the anti-obesity effects of the ligand. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1158–1166. doi: 10.1038/nm.4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Emmerson P.J., Wang F., Du Y. The metabolic effects of GDF15 are mediated by the orphan receptor GFRAL. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1215–1219. doi: 10.1038/nm.4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Massague J., Seoane J., Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sieber C., Kopf J., Hiepen C., Knaus P. Recent advances in BMP receptor signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Welsh J.B., Sapinoso L.M., Kern S.G. Large-scale delineation of secreted protein biomarkers overexpressed in cancer tissue and serum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:3410–3415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530278100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buendgens L., Yagmur E., Bruensing J. Growth differentiation Factor-15 is a predictor of mortality in critically ill patients with Sepsis. Dis. Markers. 2017;2017(527):1203. doi: 10.1155/2017/5271203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wiklund F.E., Bennet A.M., Magnusson P.K. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1/GDF15): a new marker of all-cause mortality. Aging Cell. 2010;9:1057–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material