Abstract

Bladder Cancer (BC) is one of the most common cancers in the world. Recent studies show that non-coding RNAs such as lncRNAs and circRNAs play critical roles in the progression of this cancer, but their regulatory relationships and functions are still largely unknown. As a new regulatory process within the cell, the coding and non-coding RNAs compete with each other to sponge their target miRNAs. This mechanism is described as “the competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis” which provides a new perspective to understand the regulation of gene expression in health and diseases such as cancer. In this study, to investigate the role of non-coding RNAs in BC, a new approach was used to reconstruct the ceRNA network for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) based on the expression data of coding and non-coding genes. Analysis of ceRNA networks in the early stage of BC led to the detection of an important module containing the lncRNA MEG3 as the central gene. The results show that the lncRNAs CARMN, FENDRR and ADAMTS9-AS2 may regulate MEG3 in NMIBC through sponging some important miRNAs such as miR-143-3p, miR-106a-5p and miR-34a-3p. Also, the lncRNA AC007608.2 is shown to be a potential BC related lncRNA for the first time based on ceRNA stage-specific network analysis. Furthermore, hub and altered genes in stage-specific and between stage networks led to the detection of hsa_circ_0017586 and hsa_circ_0001741 as novel potential circRNAs related to NMIBC. Finally, the hub genes in the networks were shown to be valuable candidates as biomarkers for the early stage diagnosis of BC.

Subject terms: Urological cancer, Biochemical networks

Introduction

Bladder Cancer (BC) is one of the most common cancers in men and women. This cancer is the 10th common cancer worldwide with about 200,000 people dying every year1. It has been estimated that there were 79,030 new cases of BC and 16,870 BC deaths in the United States in 20172. In China, the mortality rate of BC patients has significantly increased in recent years, and 32,900 deaths were estimated in 20153. Furthermore, due to the complex progression process and molecular interactions linked to the disease, the mechanism of BC remains poorly understood4.

Recent studies demonstrate that non-coding RNAs are closely related to BC progression and tumorigenesis5,6. Non-coding RNAs construct 80–90 percent of human transcripts7. This type of RNA is involved in many gene regulation processes in the cell, and any change in these processes can trigger complex disorders especially cancer8. Coding and non-coding RNAs regulate the expression of each other through common miRNAs that target them. This mechanism is known as the competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA)9,10. More precisely, transcripts with the same miRNA response elements (MREs) that are targeted by common miRNAs compete with each other to decoy or sponge shared miRNAs (these transcripts are called ceRNAs)9. This competition affects gene expression in the cell. Recent studies have shown that ceRNA interactions control many important biological processes and alteration in these interactions may cause diseases such as cancer11–13.

Based on previous studies, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) and transcribed pseudogenes are the most important non-coding RNAs involved in the ceRNA mechanism10,14. lncRNAs are RNAs longer than 200 nucleotides and play pivotal roles in many complex diseases15. In the past decade, the role of many lncRNAs has been studied in various cancer types. For example, lncRNA H19 is involved in metastasis, tumor initiation, and progression of many cancers16. HOTAIR, a well-known lncRNA, is overexpressed in lung cancer and correlates with its metastasis and poor prognosis17. Another type of non-coding RNA with very important regulatory functions are circRNAs18. These RNAs are constructed as a result of back-splicing from pre-mRNAs19. The conservation, stability, and tissue specificity properties of circRNAs make them valuable candidates for biomarker discovery in cancer research18,20. For instance, circRNA hsa_circ_0003221 promotes the proliferation and migration of BC cells21, and the expression of circRNA Hsa_circ_0000190 correlates with tumor size, metastasis, and disease stage of gastric cancer20. The pivotal non-coding RNAs in the ceRNA hypothesis are miRNAs. These non-coding RNAs are involved in post-transcriptional regulatory processes. They bind to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of mRNAs and prevent translation22. miRNAs dysregulation affects many critical biological processes such as cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis23. The expression of miRNAs significantly change in many cancerous tissues24, and these non-coding RNAs can act as both tumor suppressor or oncogene in cancer25.

The ceRNA interactions can be modeled as a network in which each node represents a ceRNA, and each interaction represents the competing relationship between two ceRNAs based on common miRNAs as mediators14. Reconstructing and analysis of such networks is a very fascinating approach to identify key genes in complex diseases to understand disease mechanism. Since the function of many non-coding RNAs (especially lncRNAs and circRNAs) in cancer remain unclear, the ceRNA network analysis can be helpful to discover novel cancer related non-coding RNAs as biomarkers or therapeutic targets. To understand the post-translation mechanism and non-coding RNA roles in BC, the ceRNA network analysis has been a desirable approach in recent years4,6,7,26. For instance, Zhu et al. proposed six lncRNAs as potential biomarkers for BC based on ceRNA network analysis4. Also, they found one miRNA and six differentially expressed mRNAs that correlated with BC patient survival rates. The ceRNA network reconstructed by Li et al. revealed that lncRNA MIR194-2HG, AATBC, and circRNA PGM5 could sponge the BC related miRNAs6. In7 constructing and analyzing the ceRNA network indicated that lncRNA H19 and circRNA MYLK compete with each other to decoy miRNA-29a-3p and increase the expression of its target genes DNMT3B, VEGFA and ITGB1. Moreover, in the same study, Wang et al. reconstruct the BC related ceRNA network based on 322 muscle-invasive bladder cancer tissues and 19 normal tissues26. Consequently, they proposed 5 BC related lncRNAs as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Although many studies have assessed the role of non-coding RNAs in BC, the molecular mechanism remain mostly unclear. To tackle this problem, in this study, we reconstruct and analyze a ceRNA network based on lncRNA, circRNA, transcribed pseudogene, and mRNA expression data from two early-stage urothelial carcinomas. A new computational approach was used to select disease-related mRNAs. Consequently, the stage-specific and the between stage ceRNA networks were reconstructed and examined. Finally, the hub nodes in the networks were analyzed as candidate prognostic biomarkers to detect BC at the early stages.

Results

Gene set enrichment

We selected the disease-related mRNAs based on their expression and interaction at the protein level for further analysis. Two approaches were used to this end: the PPR algorithm and the DNR approach (Eq. 2). Ten percent of the mRNAs with the highest rank (605 mRNAs) were selected in each approach, and about 70% of mRNAs chosen by the two methods were the same.

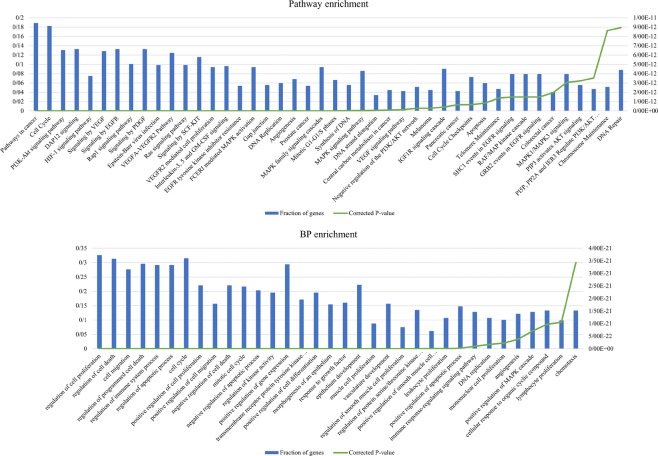

To evaluate our new approach for selecting cancer-related mRNAs, we extracted those genes selected by our method that they were not in the DEGs set. Subsequently, the biological process, pathway, and disease enrichment analysis were applied to these extracted genes (Supplementary Files 2–4). The results show that the selected genes were associated to critical cancer-related pathways and processes such as “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway”, “Rap1 signaling pathway”, “Ras signaling pathway”, “regulation of cell proliferation”, “programmed cell death”, “cell cycle” and “DNA Repair” (Fig. 1, Supplementary File 1 and Fig. S1). Furthermore, we investigated the relationship between these genes and BC using PubMed enrichment analysis in ToppFun and literature search. For the genes selected by DNR and PPR method, 62 and 45 articles about BC were found, respectively. Also, 107 and 81 genes of the genes selected by DNR and PPR respectively were studied in those mentioned articles (Supplementary File 5). These results show that there are many BC related genes in our samples that are not differentially expressed, but our new approach may be able to find them. For example, Michiels et al.27 investigated the role of 85 DNA repair genes in BC. Among the genes significantly related to BC in this study, six genes were found by our approach (CDKN2A, FANCD2, LIG1, POLR2K, RFC2, and RFC5). In a recent study, Books et al.28 experimentally found a significant association between the expression of COL1A1 and COL1A2 mRNAs and NMIBC. These genes are also found by the PPR method. MDM2, HMOX1, and SDC1 are other examples of the NMIBC related genes29,30 that are not differentially expressed in the samples but are found by our ranking methods.

Figure 1.

Some of the most critical enriched pathways and processes belonging to the mRNAs selected by DNR approach that they are not in the DEGs set.

Stage-specific ceRNA networks

Considering selected key mRNAs based on PPR and DNR methods, two ceRNA networks for each stage of BC were reconstructed (Supplementary File 1, Figs S2 and S3):

DNR-Ta: the network of ceRNAs that was reconstructed based on the mRNAs selected by the DNR method based on stage Ta expression data.

DNR-T1: the network of ceRNAs that was reconstructed based on the mRNAs selected by the DNR method based on stage T1 expression data.

PPR-Ta: the network of ceRNAs that was reconstructed based on the mRNAs selected by the PPR method based on stage Ta expression data.

PPR-T1: the network of ceRNAs that was reconstructed based on the mRNAs selected by the PPR method based on stage T1 expression data.

Table 1 shows the global properties of these networks. The degree distribution of the networks follows the power low mode (Supplementary File 1, Figs S2 and S3). It is clear that the networks are scale-free and their connections are not organized randomly.

Table 1.

Global properties of the stage-specific networks.

| Network | # nodes | # edges | # mRNAs | # lncRNAs or Pseudogenes | # circRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNR-Ta | 1692 | 32478 | 529 | 910 | 253 |

| PPR-Ta | 1655 | 31311 | 494 | 909 | 252 |

| DNR-T1 | 1295 | 13899 | 491 | 624 | 180 |

| PPR-T1 | 1283 | 15010 | 469 | 632 | 182 |

Stage-specific modules

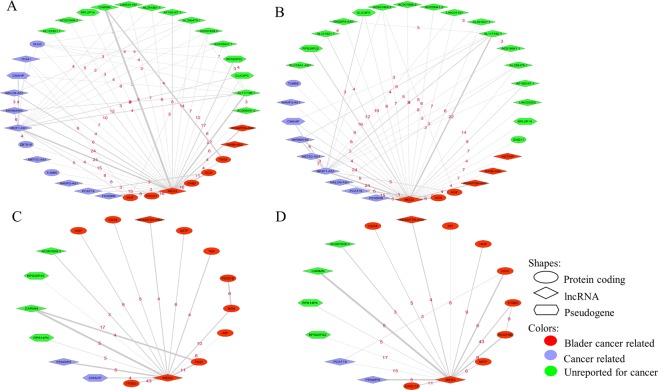

To find important functional blocks in each stage-specific network, the MCL algorithm was used to cluster the networks and detect modules. Consequently, the ToppFun web tool was used to perform GO, pathway, and disease enrichment analysis on the modules. Considering the modules with a size larger than three nodes, 55 and 83 modules were detected in DNR-T1 and DNR-Ta networks, respectively (48 and 90 modules in PPR-T1 and PPR-Ta networks, respectively). Although the enrichment tools could not find any significant process and pathway for many non-coding modules, we found some significant cancer-related pathways and processes in the modules based on enrichment analysis on coding genes (Supplementary Files 6–9). The most important modules (called MEG3 modules) detected in stage-specific networks are the modules depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

MEG3 module in stage-specific ceRNA networks ((A): DNR-Ta, (B): PPR-Ta, (C): DNR-T1, (D): PPR-T1). The thickness of the edges shows the correlation, and the number on each edge is the number of shared miRNAs between two genes.

As is shown in Fig. 2, many of the genes in the modules are the same (almost 75–80 percent of genes in modules detected by two approaches in each stage are common). This shows that in fact, we found one module by two approaches, altered when the disease has progressed from stage Ta to T1. Searching in the literature shows that there are many cancer-related genes in this module (Supplementary File 1, Table S1). Also, the biological process and pathway enrichment analysis of the protein-coding genes in this module showed that it is involved in many important processes and pathways in human cells (Supplementary File 10). The genes in this module could be interesting candidates for therapeutic targets.

Stage-specific key genes

Key genes in the stage-specific networks were detected using the degree, and betweenness centrality measures. The degree of each gene in the network demonstrates the number of genes that are connected with it and the betweenness centrality measures the amount of shortest path that passes from the genes. Therefore, the genes with high degree and betweenness centralities can be important because these genes compete with many other genes and play a pivotal role to construct pathways in the network, respectively. Accordingly, we selected the top 10 genes with the highest degree and betweenness centrality in each stage-specific network as key genes and analyzed cancer relativity of them based on literature searches (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Key nodes in stage Ta networks based on Degree and Betweenness centrality measures.

| Gene name | Gene type | DNR-Ta network* | PPR-Ta network* | Some related cancers | Reference (PMID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRAS | Protein coding | D, B | D, B | Bladder, Colorectal, Melanoma |

21072204 22820081 28074351 |

| PDIA6 | Protein coding | D, B | — | Bladder, Breast |

27760590 26125904 |

| CCNG1 | Protein coding | D, B | — | Bladder, Ovarian |

27982046 25981880 |

| hsa_circ_0000591 | circRNA | D | D | — | — |

| hsa_circ_0000592 | circRNA | D | D, B | — | — |

| RPLP0P6 | Pseudogene | D, B | D, B | — | — |

| PARPBP | Protein coding | D | D | Pancreatic | 23436799 |

| CCNT2 | Protein coding | D | — | leukemia | 28409330 |

| MSH6 | Protein coding | D | D, B | Bladder, colorectal |

20591884 21642682 |

| hsa_circ_0003221 | circRNA | D | D | Bladder | 29125888 |

| KCNQ1OT1 | lncRNA | B | B | Breast, Lung |

30157476 28600629 |

| PWAR6 | lncRNA | B | B | Glioma, Breast |

30472640 30297886 |

| WEE1 | Protein coding | B | B | Breast, Leukemia, Melanoma, Brain | 27427153 |

| HCG18 | lncRNA | B | B | Bladder | 30426533 |

| AC015813.1 | lncRNA | B | B | — | — |

| NCAPD2 | Protein coding | B | — | Bladder | 21982874 |

| RFC3 | Protein coding | — | D | Breast, Ovarian, Esophageal |

27888707 26464638 22328562 |

| CCNA2 | Protein coding | — | D | Bladder, Breast, Colorectal |

30138038 24622579 30464611 |

| hsa_circ_0017586 | circRNA | — | D | — | — |

| NAMPTP1 | Pseudogene | — | B | — | — |

*D: Degree, B: Betweenness.

Table 3.

Key nodes in stage T1 networks based on Degree and Betweenness centrality measures.

| Gene name | Gene type | DNR-T1 network* | PPR-T1 network* | Some related cancers | Reference (PMID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCNA2 | Protein coding | D | D | Bladder, Breast, Colorectal |

30138038 24622579 30464611 |

| CCNB1 | Protein coding | D | D | Bladder, Breast, Gastric |

30170380 28821558 30518842 |

| PARPBP | Protein coding | D | D | Pancreatic | 23436799 |

| NCAPD2 | Protein coding | D | D | Ovarian | 21423607 |

| RFC3 | Protein coding | D | D | Breast, Ovarian, Esophageal |

27888707 26464638 22328562 |

| MCM7 | Protein coding | D | D | Bladder, Lung |

23201130 27797825 |

| KPNA2 | Protein coding | D | D | Bladder, Lung, Colorectal |

27611951 27009856 26663089 |

| ASF1B | Protein coding | D | D | Breast | 21179005 |

| LMNB1 | Protein coding | D | — | Liver, Cervical |

19522540 30394198 |

| CDC25A | Protein coding | — | D | Bladder, Breast, Ovarian |

29246203 30443946 30405749 |

| NUP214 | Protein coding | B | — | Leukemia | 25120641 |

| RPLP0P6 | Pseudogene | B | B | — | — |

| NR2F1-AS1 | lncRNA | B | — | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 29602203 |

| YWHAH | Protein coding | B | — | Glioma | 26370624 |

| GAPDHP1 | Pseudogene | D, B | B | — | — |

| NRAS | Protein coding | B | B | Bladder, Colorectal, Melanoma |

21072204 22820081 28074351 |

| LINC01355 | lncRNA | B | — | Lung | 28949095 |

| GLI2 | Protein coding | B | — | Bladder, Gastric |

27465044 28975979 |

| CCNT2 | Protein coding | B | — | leukemia | 28409330 |

| EEF1A1P13 | Pseudogene | B | — | — | — |

| FASN | Protein coding | — | D | Bladder, Breast |

30221356 28922023 |

| ANXA2P2 | Pseudogene | — | B | — | — |

| HCG18 | lncRNA | — | B | Bladder | 30426533 |

| NCOR2 | Protein coding | — | B | Lung | 29764865 |

| COL1A2 | Protein coding | — | B | Bladder, Gastric |

27655672 28401451 |

| MEG3 | lncRNA | — | B | Bladder, Gastric, Esophageal, Glioma, Breast, Ovarian |

30461333 30417553 30310931 28975980 28539329 30389444 |

| ENO1 | Protein coding | — | B | Pancreatic, Gastric, Colorectal |

28086938 29986635 26097998 |

| CDC25B | Protein coding | — | B | Bladder, Endometrial, Gastric |

29234286 29353204 27863420 |

*D: Degree, B: Betweenness.

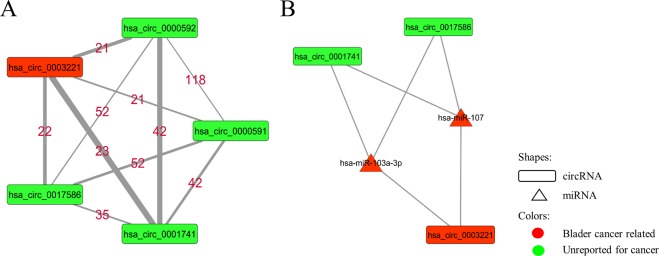

As shown in Table 3, no circRNA is detected as a hub in T1 networks, but in Ta networks, the circRNAs are seen in the hub nodes set. If 13 and 12 nodes with the highest degree are considered in PPR-Ta and DNR-Ta networks respectively, five circRNAs (hsa_circ_0000591, hsa_circ_0000592, hsa_circ_0003221, hsa_circ_0017586, hsa_circ_0001741) are seen as hub nodes in both networks. hsa_circ_0000591, hsa_circ_0000592, and hsa_circ_0003221 are derived from the PTK2 gene and hsa_circ_0017586, and hsa_circ_0001741 are derived from GDI2 and TNPO3, respectively. Interestingly, all of these transcripts interact with each other in Ta networks (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the circRNA hsa_circ_0003221 has been recently reported as a novel biomarker in BC that promotes the migration and proliferation of BC cells21. hsa_circ_0003221, hsa_circ_0017586 and hsa_circ_0001741 share 2 miRNAs that are involved in multiple cancers including BC (Fig. 3B)31–38.

Figure 3.

The module constructed from 5 hub circRNAs in Ta networks.

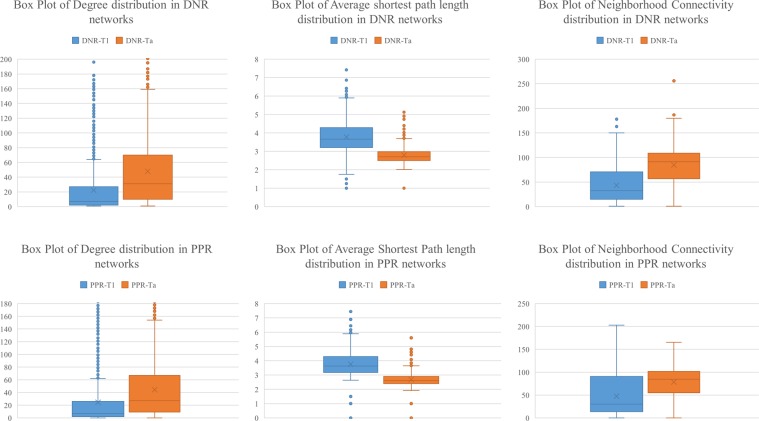

Between stage networks

To investigate how the connections of the ceRNAs change between stage Ta and T1, we compared the degree, shortest path and neighborhood connectivity of the genes in stage-specific networks (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4, the degree and neighborhood connectivity of the genes in Ta networks are higher than T1. Also, the average shortest path of the genes in T1 networks is higher than Ta. These results show that many of the ceRNAs connections are lost when the tumor progresses from Ta to T1 stage. To determine which connection is altered and which genes have the most changes in their connections, we reconstructed the between stage networks through calculating the difference of edges. Two network types were defined: Lose Interaction Network (LIN = Ta − T1) and Gain Interaction Network (GIN = Ta − T1).

Figure 4.

Comparing the connection between genes in Ta and T1 networks. The node degree, average shortest path and neighborhood connectivity distributions in all stage-specific networks show that many of connections have been lost in T1 networks relative to Ta.

Subsequently, the most important genes in these networks (genes with the most connection changes from stage Ta to T1) were detected using degree and betweenness centrality measures (top 10 genes with the highest rank based on each measure were selected). The results show that most of the important genes in the between stage networks, especially the genes with the most altered connections (high degree or hub genes) are critical in cancer (Tables 4 and 5). These genes could be potential biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis. For example, circRNA hsa_circ_0003221 is one of the hub genes in DNR-LIN and PPR-LIN networks. Recently, Xu et al.21 have demonstrated that this circRNA promotes the proliferation and migration of BC cells.

Table 4.

Key nodes in stage LIN networks based on Degree and Betweenness centrality measures.

| Gene name | Gene type | DNR-LIN network* | PPR-LIN network* | Some related cancers | Reference (PMID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa_circ_0000591 | circRNA | D, B | D, B | — | — |

| CCNT2 | Protein coding | D, B | — | Leukemia | 28409330 |

| hsa_circ_0000592 | circRNA | D | D, B | — | — |

| NRAS | Protein coding | D, B | D, B | Bladder, Colorectal, Melanoma |

21072204 22820081 28074351 |

| WEE1 | Protein coding | D, B | D, B | Breast, Leukemia, Melanoma, Brain | 27427153 |

| CCNG1 | Protein coding | D, B | — | Bladder, Ovarian |

27982046 25981880 |

| hsa_circ_0001741 | circRNA | D | D | — | — |

| hsa_circ_0017586 | circRNA | D | D | — | — |

| hsa_circ_0007646 | circRNA | D | D | Hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, Pancreatic |

28514762 29922161 |

| hsa_circ_0003221 | circRNA | D | D | Bladder | 29125888 |

| MDM2 | Protein coding | B | B | Bladder, Ovarian |

28498468 28817834 |

| PWAR6 | lncRNA | B | B | Glioma, Breast |

30472640 30297886 |

| KCNQ1OT1 | lncRNA | B | B | Breast, Lung |

30157476 28600629 |

| hsa_circ_0008345 | circRNA | — | D | — | — |

| AC015813.1 | lncRNA | B | B | — | — |

| IGF1R | Protein coding | B | — | Bladder, Colon |

27470393 28882129 |

| NEAT1 | lncRNA | — | B | Bladder, thyroid |

30349370 30596336 |

| GABPB1-AS1 | lncRNA | — | B | — | — |

| hsa_circ_0011536 | circRNA | — | D | — | — |

*D: Degree, B: Betweenness.

Table 5.

Key nodes in stage GIN networks based on Degree and Betweenness centrality measures.

| Gene name | Gene type | DNR-GIN network* | PPR-GIN network* | Some related cancers | Reference (PMID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FADD | Protein coding | D, B | — | Pancreatic, Lung |

28454341 30190126 |

| PSMC4 | D | D | Breast | 18042273 | |

| GAPDHP1 | Pseudogene | D, B | D | — | — |

| PDIA5 | Protein coding | D | — | Melanoma | 25912252 |

| SLC25A1 | Protein coding | D | — | Lung | 29651165 |

| TFRC | Protein coding | D | D | Melanoma | 28551638 |

| SNRPA | Protein coding | D | — | Gastric | 30039889 |

| MYC | Protein coding | D, B | D, B | Bladder, Prostate |

29463565 27159573 |

| MCM3 | Protein coding | D | D | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 30363964 |

| HSPA1A | Protein coding | D | Bladder, Ovarian |

23874968 26868087 |

|

| NR3C1 | Protein coding | B | — | Bladder, Gastric |

29991691 29285253 |

| NUP214 | Protein coding | B | — | Leukemia | 25120641 |

| NR2F1-AS1 | lncRNA | B | B | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 29602203 |

| GLI2 | Protein coding | B | — | Bladder, Gastric |

27465044 28975979 |

| NCOR2 | Protein coding | B | — | Lung | 29764865 |

| ADCY7 | Protein coding | B | B | Leukemia | 26220344 |

| FASN | Protein coding | — | D, B | Bladder, Breast |

30221356 28922023 |

| CBX2 | Protein coding | — | D | Ovarian | 30478317 |

| CDC25B | Protein coding | — | D, B | Bladder, Endometrial, Gastric |

29234286 29353204 27863420 |

| ADCY3 | Protein coding | — | D | Gastric | 24113161 |

| DAG1 | Protein coding | — | D | Leukemia | 28591567 |

| STAT1 | Protein coding | — | B | Bladder, Breast, Lung, Melanoma, Gastric, Colorectal, Esophageal |

27080594 28950072 |

| ANXA2P2 | Pseudogene | — | B | — | — |

| CDK6 | Protein coding | — | B | Bladder, Esophageal |

30362519 30551480 |

| IL10 | Protein coding | — | B | Bladder, Melanoma, Lung |

27987237 26188281 |

| PART1 | lncRNA | B | — | Esophageal, Lung, Prostate |

30049286 28819376 29261512 |

| LINC02607 | lncRNA | — | B | — | — |

*D: Degree, B: Betweenness.

Potential biomarker detection

As mentioned in section 2.8, we analyzed the hub nodes (nodes with the highest degree) as candidate biomarkers to investigate which hubs were able to separate Ta and T1 samples based on their expression patterns. Since the expression of circRNAs relative to other RNAs is very low in the samples (Supplementary File 1, Fig. S4), we analyzed circRNAs separately. Overall, 48 gene sets from 8 networks were analyzed (16 circRNA sets and 32 other RNA sets from DNR and PPR networks). Note that there were no circRNAs as a hub in the GIN and T1 networks.

None of the circRNA sets were able to separate Ta and T1 samples significantly. Among all circRNA hubs, five circRNAs (Fig. 3A) with the highest degree in Ta networks (DNR-Ta and PPR-Ta) showed approximately good clustering, but validation results demonstrated that these genes are not able to separate samples based on their expression pattern or maybe our clustering method is not sensitive enough for the circRNAs (Supplementary File 1, Fig. S5). These transcripts are seen in the top ten circRNAs with the highest degree in all networks (except T1 and GIN networks that do not have any circRNAs in their highest degree genes).

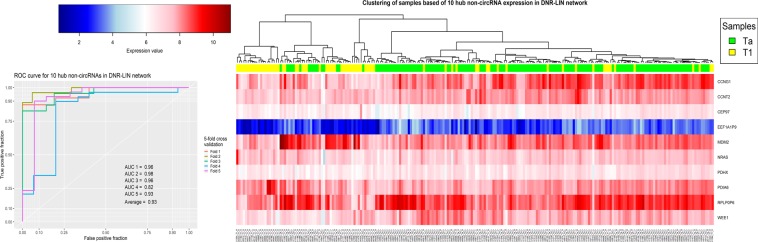

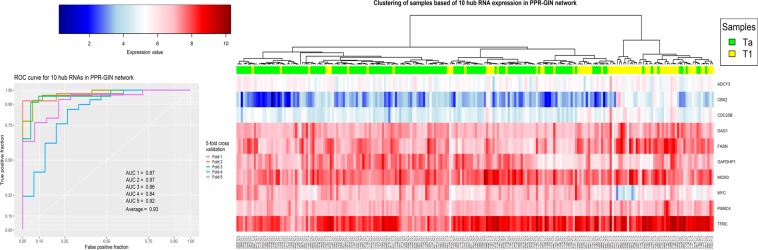

In the LIN networks, the set of 10 non-circRNAs with the highest degree in the DNR-LIN network showed an acceptable clustering result on all samples (Fig. 5). The validation results for these genes were also satisfactory and the average AUC in the 5-fold cross validation was 0.93 for these genes. For the GIN networks, the best clustering result was obtained from the 10 RNAs with the highest degree in the PPR-GIN network (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

The clustering and Validation results for ten non-circRNAs with the highest degree in the DNR-LIN network.

Figure 6.

The clustering and Validation results for ten genes with the highest degree in the PPR-GIN network.

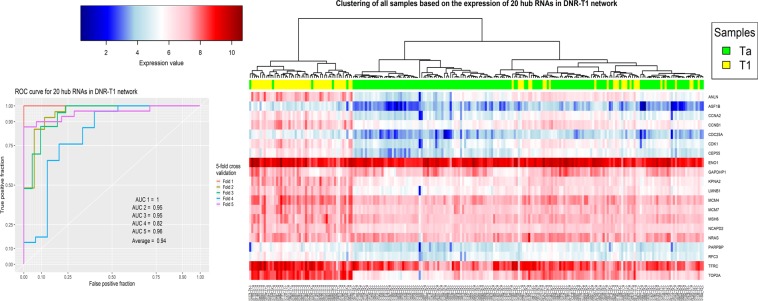

The clustering result for 20 genes with the highest degree in DNR-T1 networks was interesting, and the validation showed that these genes could be a bona fide potential biomarker set to separate Ta and T1 bladder cancer stages from each other (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The clustering and Validation results for 20 genes with the highest degree in the DNR-T1 network.

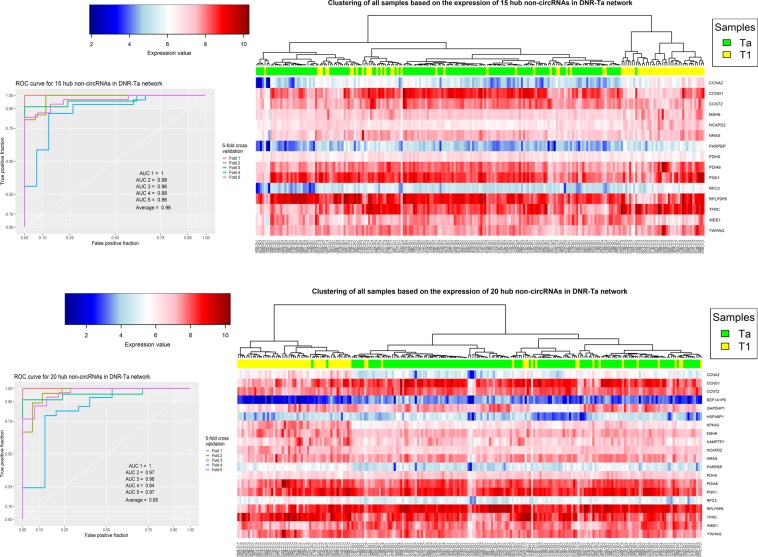

The results show that the hub genes in the Ta networks are interesting to further investigate as biomarkers. The best validation result was acquired from the set of 15 and 20 high degree non-circRNA genes in the DNR-Ta network (Fig. 8). The average AUCs for these sets in the 5-fold cross validation were 0.96 and 0.95, respectively. Approximately the same results were acquired from the PPR-Ta network (Supplementary File 1, Fig. S6).

Figure 8.

The clustering and validation results for 15 and 20 genes with the highest degree in DNR-Ta network.

Discussion

Reconstructing the ceRNA networks based on differentially expressed genes is widely used in the researches but the expression difference is not the only key factor in the ceRNAs activity. For instance, a gene may decoy a large number of miRNAs through a large number of MREs while its expression may not be changed significantly14. To challenge those mentioned limitations and reconstruct ceRNA network for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC), we used the expression data of four RNA types (mRNA, lncRNA, pseudogene, and circRNA) in stages of Ta and T1 in bladder cancer transcriptomics data. Additionally, we integrated gene expression data with PPI scaffold to select the ceRNAs based on both expression changes and interactions at the protein level.

The stage-specific network analysis led to the prediction of an important module, entitled the MEG3 module, containing some key cancer-related coding and non-coding genes. As shown in Fig. 2, indeed four modules in four networks were predicted but many of the genes in these modules are the same. More precisely, there is one module (detected by two computational approaches) that has its genes and interactions rewired when the disease progresses from stage Ta to T1. Many of the genes in the MEG3 module are cancer-related (more than 80% in T1 and more than 50% in Ta networks), and interestingly in T1 networks, all protein-coding genes detected in the module are bladder cancer-related. This proves that our suggested approach enjoys significant power to predict disease-related genes.

lncRNA MEG3 is the core gene in this module that interacts with all other genes (except PDGFB and AC018647.1 in DNR-T1 and PPR-Ta networks, respectively). This is a very important cancer-related lncRNA that acts as a tumor suppressor in many cancers including bladder cancer5,39–41. Strong correlated competing interactions are observed between this gene and some other bladder cancer-related genes in this module that has not yet been reported for NMIBS. For example, ADAMTS9-AS2 is a bladder cancer-related lncRNA4 that interacts with MEG3 in both Ta and T1 networks through sharing four miRNAs (hsa-miR-148b-3p, hsa-miR-143-3p, hsa-miR-574-5p and hsa-miR-4701-3p). Among these miRNAs, miR-574-5p is an important cancer-related miRNA that shows oncogenic function in thyroid, breast, and lung cancers42,43 but has been not reported in NMIBC. CARMN (or miR143HG) is another bladder cancer related lncRNA44 that has a strong connection with MEG3 (correlation 0.76) via sharing 5 miRNAs (hsa-miR-148b-3p, hsa-miR-106a-5p, hsa-miR-9-5p, hsa-miR-148a-3p, hsa-miR-501-3p). miR-106a-5p is significantly associated with tumor grade in NMIBC45 and miR-148a-3p suppresses Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and cell proliferation in bladder cancer46.

An example of a bladder cancer-related mRNA that is found in the MEG3 module is Decorin47. In our results, the lncRNA MEG3 competes with Decorin through sponging 6 miRNA including hsa-miR-122-5p, hsa-miR-484, hsa-miR-338-3p, hsa-miR-30a-3p, hsa-miR-30e-3p, hsa-miR-224-5p. miR-484 is a tumor suppressor miRNA between MEG3 and Decorin in our module. Also, the lncRNA ZFAS1 promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation via sponging this miRNA48. Furthermore, ZFAS1 recently has been detected as an oncogenic lncRNA in BC49. Therefore, miR-484 can be introduced as an important NMIBC related miRNA.

FENDRR is another key lncRNA in MEG3 module. This gene has a suppressive function in non-small cell lung cancer, and downregulation of it correlates with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma50,51. We found just one study by Suqing et al.52 reporting it as a significantly downregulated lncRNA in bladder cancer. Five miRNAs are shared between FENDRR and MEG3 in our networks (hsa-miR-148a-5p, hsa-miR-106b-5p, hsa-miR-4705, hsa-miR-20a-5p, hsa-miR-34a-3p). Interestingly, all of these miRNAs (except miR-4705) are bladder cancer related53–55, and one of them (miR-34a-3p) has been reported as a biomarker of NMIBC recurrence56. These results indicate that the lncRNA FENDRR can potentially be a novel candidate lncRNA related to NMIBC.

As shown in Fig. 2, there are some cancer-related genes in the MEG3 module that highly correlate and interact with bladder cancer genes, but no report was found about the activity of these genes in bladder cancer. These genes are potentially related to NMIBC and should be investigated as future work. For instance, NR2F1-AS1 was strongly connected with MEG3 in Ta networks. This gene is relevant to oxaliplatin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma57. Furthermore, some other genes in the module such as lncRNA AC007608.2 and AL117190.1 have a strong connection with MEG3 and some other cancer-related genes, but we did not find any report about their roles in cancer. These genes could be candidate genes to investigate their function in bladder cancer especially NMIBC. Taking a closer look at these interactions and shared miRNAs can help to select a better candidate gene. For instance, there are three shared miRNAs between AC007608.2 and MEG3 and one of them (miR-324-3p) is bladder cancer related58 and two others (miR- 365a-3p, miR-365b-3p) are involved in other cancer types59,60. Therefore, the lncRNA AC007608.2 is another novel candidate gene potentially related to NMIBC.

Change in ceRNA interactions is one of the key features of cancer11,13. Therefore, we reconstructed between-stage networks (LIN and GIN) by calculating the difference between the edge set of Ta and T1 networks. Subsequently, the top 10 hub genes (10 genes with the highest degree) in these networks were detected as the genes with the most connection rewiring when the disease progressed from Ta to T1 stage. In the LIN and Ta networks, five circRNAs had the highest degrees simultaneously (Fig. 3A). Among these hub circRNAs, hsa_circ_0003221, hsa_circ_0000591, and hsa_circ_0000592 were derived from one gene (PTK2), and hsa_circ_0003221 recently has been reported as a potential biomarker for bladder cancer that promotes proliferation and migration of cancer cells21. We did not find any report about the four other circRNAs in this set but closely looking in the module constructed by these transcripts revealed that there are only two important miRNAs (miR-103a-3p, miR-107) shared between hsa_circ_0003221, hsa_circ_0017586, and hsa_circ_0001741 (Fig. 3B). These two miRNAs have recently been reported as regulators to promote proliferation and migration of BC cells through ceRNA activity of circTCF25 and CDK631. miR-107 is one of the most important miRNAs in cancer36. This miRNA is sponged by the lncRNA RP11-79H23.3 and regulates PTEN in BC cells34. This process can suppress BC development via inactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway35. The tumor suppressor function of miR-107 via ceRNA activity has also been demonstrated by Su et al. in another recent study32. Therefore, hsa_circ_0017586 and hsa_circ_0001741 may have oncogenic functions in BC through sponging miR-107. Furthermore, miR-103a-3p, another miRNA shared between the three mentioned circRNAs, is also involved in BC and some other cancer types such as Gastric and Glioma33,37,38.

The last analysis in this study was to evaluate the hub genes as potential biomarkers to design a diagnostic panel. To this end, the set of hub genes in each network were analyzed using hierarchical clustering with correlation based distance and SVM classifier with 5-fold cross validation (see section Materials and method). As shown in Figs 5–8 and Supplementary File 1, Fig. S6, the results show the power of hub genes to separate Ta and T1 samples based on their expression patterns.

The results of our study demonstrate that the selection of genes via a computational manner such as mapping the expression difference of genes on PPI data and ranking them based on their connection and expression could be an alternative approach to find significant disease-related genes. Also, the ceRNA hypothesis and its novel perspective to the gene regulatory system could be very helpful to understand complex disease mechanisms such as cancer.

Material and Method

Data collection

Total RNA sequencing of 457 Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) samples (348 samples in stage Ta and 109 samples in stage T1) were selected from the ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress)61 under accession number E-MTAB-432162. circRNA expression data was obtained from Okholm et al.63.

Preprocessing and normalization

Based on the ceRNA hypothesis, lncRNAs, transcribed pseudogenes, circRNAs, and mRNAs are four key RNA categories that act as ceRNAs14,64. Therefore, we selected only these types of RNAs for further analysis. The BioMart tool65 from the Ensembl genome browser (www.ensembl.org)66 was used to select the gene types.

In the next step, the genes with low expression in all samples were removed. To this end, we filtered out each gene that had an average count in all samples of less than one67. Furthermore, the genes with low standard deviation (lower than the first quartile of the standard deviation of all genes) in all samples were also filtered out. Additionally, the genes with a high standard deviation of their count in T1 or Ta stages were also filtered out (threshold was the third quartile of the standard deviation of all genes in each group).

Considering all samples of a stage of the disease, if the average Pearson correlation of a sample with other samples was less than the first quartile of Pearson correlations between all sample pairs, then this sample was ignored as a within stage outlier. After all preprocessing steps, 220 samples (148 Ta and 72 T1) were selected for further analysis. The ceRNA count data was normalized using the TMM method68 implemented in the edgeR package69 and the log-transformed normalized count table used for further analysis.

Key mRNA selection

Generally, due to a large number of genes, the ceRNA networks are reconstructed based on Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs), but it is obvious that DEGs are not the only actors in this process14. Therefore, we tried to find key disease-related mRNAs based on expression data and physical interactions at the protein level. To this end, firstly we applied differential expression analysis to get the fold change and p-value of all mRNAs (the edgeR package was used). After that, a combined weight was assigned to each mRNA based on Eq. 1:

| 1 |

where g is a protein-coding gene or mRNA in the data.

In the next step, the Protein-Protein Interactions (PPI) of all weighted mRNAs were extracted from the STRING database70 with a minimum interaction confidence score of 0.5. The weighted nodes in the PPI network were ranked based on their weights and connections. Finally, 10 percent of the nodes with the highest ranks were selected for further analyses. Two ranking methods were applied: the Personalized PageRank (PPR) algorithm71 (implemented by the igrapg package72) and our proposed method based on Eq. 2 (entitled Depth Neighborhood Ranking or DNR):

| 2 |

where g is a vertex in the PPI network (a protein-coding gene), w(g) is the weight of vertex g calculated by Eq. 1, is the set of neighbors of vertex g that the shortest path of g to them is equal to d.

In this new approach, we tried to add a fraction of total weights of the neighbors to the initial weight of each vertex. This fraction is the square root of the number of neighbors because the slope of the square root function grows softly by increasing the number of neighbors. Concerning “d” as a depth threshold, the effect of farther neighbors can be applied. However, the greater the distance from g the lower the effect as neighbors weights are divided by d threshold (The d threshold was set to 2 as default).

ceRNA network reconstruction and Module Detection

The miRNAs that target the key mRNAs were extracted from the TarBase73 mirTarBase74 and RAID75 databases. In addition to the mRNA-miRNA bipartite network obtained from the key mRNAs and abovementioned databases, three other ceRNA-miRNA bipartite networks (lncRNA-miRNA, pseudogenes-miRNA, and circRNA-miRNA) were reconstructed based on the extracted miRNAs and the experimentally validated data from the RAID, lncBase76 and StarBase77 databases. The ceRNA-miRNA bipartite networks were merged and reconstructed to form a basic ceRNA-ceRNA interaction network. In this network, the nodes represent ceRNAs (mRNA, lncRNA, circRNA or pseudogene) and two ceRNAs are connected if they have common miRNAs in bipartite networks. All edges with less than three shared miRNAs were removed from the network. The hypergeometric test was applied to all ceRNA-ceRNA interactions based on Eq. 312:

| 3 |

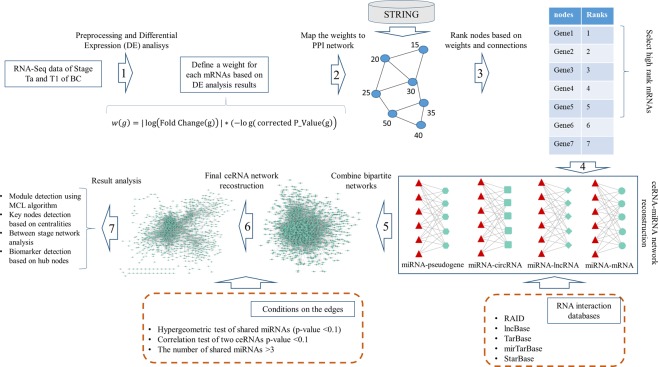

where, s is the number of miRNAs shared between ceRNA1 and ceRNA2, c1 is the number of miRNAs targeting ceRNA1, c2 is the number of miRNAs targeting ceRNA2 and T is the total number of miRNAs in the human genome. All edges with a hypergeometric test p-value higher than 0.01 were removed from the basic network. Next, the normalized ceRNA count table was used to implement the Pearson correlation test for all interactions in the basic ceRNA-ceRNA interaction network. All edges with a correlation test p-value larger than 0.01 were removed from the network. Since the Pearson correlation test for each interaction was applied based on Ta and T1 samples separately, two final ceRNA-ceRNA interaction networks (Ta ceRNA network and T1 ceRNA network) were obtained for further analysis. Figure 9 shows the overall process of our study.

Figure 9.

The overall process of our study.

Additionally, we reconstructed between stage ceRNA network from Ta and T1 networks using the difference of edge sets. Cytoscape version 3.278 was applied to visualize and reconstruct the network differences.

The Markov CLuster (MCL) algorithm79 via the ClusterMaker Cityscape application80 was used to detect modules in the networks.

Enrichment analysis

The Gene Ontology (GO), disease and pathway enrichment analyses were performed using the ToppFun web tool81.

Centrality calculation

The critical genes in the networks were predicted based on degree and betweenness centrality measures. The CytoNCA82 tool was applied to calculate centralities.

Potential biomarker detection

For potential biomarker detection, 5, 10, 15 and 20 hub genes (genes with the highest degree) in the networks were selected. After that, all samples were clustered based on the expression pattern of each chosen gene set (hierarchical clustering with ward.D2 method83 and 1-Pearson correlation as the distance). The gene sets that significantly separated the Ta and T1 samples based on expression pattern were selected as candidate biomarker sets.

To validate biomarkers, we used SVM classifier and 5-fold cross-validation. Consequently, by calculating the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and Area Under the Curve (AUC) the best gene sets were selected as final potential biomarkers to detect BC in the early stage. The e107184, plotROC85 and ggplot286 R packages were used to apply the SVM algorithm and calculate and visualize ROC curves.

Supplementary information

Supplementary file 1 (Supplementary Figures and Tables)

Supplementary file 2 (mRNAs Disease enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 3 (mRNAs BP enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 4 (mRNAs Pathway enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 5 (mRNAs PubMed enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 6 (DNR-Ta network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 7 (DNR-T1 network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 8 (PPR-Ta network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 9 (PPR-T1 network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 10 (MEG3 module enrichment analysis results)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks Dr. Jakob Hedegaard, Dr. Soren Vang, Dr. Trine Line Hauge Okholm and their team from the Department of Molecular Medicine (MOMA), Aarhus University Hospital for providing the data and valuable collaborations during the project.

Author Contributions

Morteza Kouhsar: Conceptualization, implementation, formal analysis, investigation, writing-review & editing. Sadegh Azimzadeh Jamalkandi: Conceptualization, result analysis, writing-review & editing. Ali Moeini: writing-review & editing. Ali Masoudi-Nejad: Conceptualization, Supervision, project administration, writing-review & editing.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-44944-3.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N, et al. Integrated analysis of a competing endogenous RNA network reveals key lncRNAs as potential prognostic biomarkers for human bladder cancer. Medicine. 2018;97:e11887. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng, S., Zhang, X., Fan, H., Sun, Q. & Zhang, M. Up-regulation of LncRNA MEG3 inhibits cell migration and invasion and enhances cisplatin chemosensitivity of bladder cancer cells. Neoplasma (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Li M, Liu Y, Zhang X, Liu J, Wang P. Transcriptomic analysis of high-throughput sequencing about circRNA, lncRNA and mRNA in bladder cancer. Gene. 2018;677:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang M, et al. Comprehensive analysis of differentially expressed profiles of lncRNAs and circRNAs with associated co-expression and ceRNA networks in bladder carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:47186. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anastasiadou E, Jacob LS, Slack FJ. Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2018;18:5. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo L-L, et al. Competing endogenous RNA networks and gastric cancer. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015;21:11680. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi X, et al. ceRNA in cancer: possible functions and clinical implications. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2015;52:710–718. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song C, et al. The global view of mRNA-related ceRNA cross-talks across cardiovascular diseases. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:10185. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10547-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang C, et al. Competing endogenous RNA networks in human cancer: hypothesis, validation, and perspectives. Oncotarget. 2016;7:13479. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le TD, Zhang J, Liu L, Li J. Computational methods for identifying miRNA sponge interactions. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2016;18:577–590. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martens-Uzunova ES, et al. Long noncoding RNA in prostate, bladder, and kidney cancer. European urology. 2014;65:1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raveh E, Matouk IJ, Gilon M, Hochberg A. The H19 Long non-coding RNA in cancer initiation, progression and metastasis–a proposed unifying theory. Molecular cancer. 2015;14:184. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0458-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loewen G, Jayawickramarajah J, Zhuo Y, Shan B. Functions of lncRNA HOTAIR in lung cancer. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2014;7:90. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng S, et al. CircRNA: functions and properties of a novel potential biomarker for cancer. Molecular cancer. 2017;16:94. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L-L, Yang L. Regulation of circRNA biogenesis. RNA biology. 2015;12:381–388. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S, Li T, Zhao Q, Xiao B, Guo J. Using circular RNA hsa_circ_0000190 as a new biomarker in the diagnosis of gastric cancer. Clinica chimica acta. 2017;466:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu ZQ, Yang MG, Liu HJ, Su CQ. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0003221 (circPTK2) promotes the proliferation and migration of bladder cancer cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2018;119:3317–3325. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2014;15:509. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin VY, Chu K-M. MiRNA as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for gastric cancer. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2014;20:10432. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iorio MV, Croce CM. MicroRNA dysregulation in cancer: diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics. A comprehensive review. EMBO molecular medicine. 2012;4:143–159. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng Y, Croce CM. The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2016;1:15004. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2015.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of aberrantly expressed profiles of lncRNAs and miRNAs with associated ceRNA network in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:86174. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michiels S, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in 85 DNA repair genes and bladder cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:763–768. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks M, et al. Positive association of collagen type I with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer progression. Oncotarget. 2016;7:82609. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JH, Park J. Prognostic significance of heme oxygenase-1, S100 calcium-binding protein A4, and syndecan-1 expression in primary non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Human pathology. 2014;45:1830–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie L, et al. Association between MDM2 SNP309 T > G polymorphism and the risk of bladder cancer: new data in a chinese population and an updated meta-analysis. OncoTargets and therapy. 2015;8:3679. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S95353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong Z, Lv M, Chen J. Screening differential circular RNA expression profiles reveals the regulatory role of circTCF25-miR-103a-3p/miR-107-CDK6 pathway in bladder carcinoma. Scientific reports. 2016;6:30919. doi: 10.1038/srep30919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su H, et al. Circular RNA cTFRC acts as the sponge of MicroRNA-107 to promote bladder carcinoma progression. Molecular cancer. 2019;18:27. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0951-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang X, et al. Serum microRNA expression signatures as novel noninvasive biomarkers for prediction and prognosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:36733. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chi H, et al. LncRNA RP11-79H23. 3 Functions as a Competing Endogenous RNA to Regulate PTEN Expression through Sponging hsa-miR-107 in the Development of Bladder Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018;19:2531. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Q, et al. MiR-103/107 induces tumorigenicity in bladder cancer cell by suppressing PTEN. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2018;22:8616–8623. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201812_16625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo Z, Zheng Y, Zhang W. Pleiotropic functions of miR107 in cancer networks. OncoTargets and therapy. 2018;11:4113. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S151236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He Q, et al. MOV10 binding circ-DICER1 regulates the angiogenesis of glioma via miR-103a-3p/miR-382-5p mediated ZIC4 expression change. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2019;38:9. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0990-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu X, et al. miRNA-103a-3p promotes human gastric cancer cell proliferation by targeting and suppressing ATF7 in vitro. Molecules and cells. 2018;41:390. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2018.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu M, et al. MEG3 overexpression inhibits the tumorigenesis of breast cancer by downregulating miR-21 through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2019;661:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Xu W, He Y, Xia Q, Liu S. LncRNA MEG3 impacts proliferation, invasion, and migration of ovarian cancer cells through regulating PTEN. Inflammation Research. 2018;67:927–936. doi: 10.1007/s00011-018-1186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu, D. H., Chi, G. N., Zhao, C. H. & Li, D. Y. Long noncoding RNA MEG3 inhibits proliferation and migration but induces autophagy by regulation of Sirt7 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in glioma cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Zhang Z, Li X, Xiao Q, Wang Z. MiR-574-5p mediates the cell cycle and apoptosis in thyroid cancer cells via Wnt/β-catenin signaling by repressing the expression of Quaking proteins. Oncology letters. 2018;15:5841–5848. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, P.-S. et al. A novel long non-coding RNA linc-ZNF469-3 promotes lung metastasis through miR-574-5p-ZEB1 axis in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene, 1 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Xie, H. et al. LncRNA miR143HG suppresses bladder cancer development through inactivating Wnt/β-catenin pathway by modulating miR-1275/AXIN2 axis. Journal of cellular physiology (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Mearini E, et al. Expression of urinary miRNAs targeting NLRs inflammasomes in bladder cancer. OncoTargets and therapy. 2017;10:2665. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S132680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, et al. miR-148a-3p represses proliferation and EMT by establishing regulatory circuits between ERBB3/AKT2/c-myc and DNMT1 in bladder cancer. Cell death & disease. 2016;7:e2503. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Appunni S, et al. Altered expression of small leucine-rich proteoglycans (Decorin, Biglycan and Lumican): Plausible diagnostic marker in urothelial carcinoma of bladder. Tumor Biology. 2017;39:1010428317699112. doi: 10.1177/1010428317699112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie S, Ge Q, Wang X, Sun X, Kang Y. Long non-coding RNA ZFAS1 sponges miR-484 to promote cell proliferation and invasion in colorectal cancer. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:154–161. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1407895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang, H., Li, G., Cheng, B. & Jiang, R. ZFAS1 functions as an oncogenic long noncoding RNA in bladder cancer. Bioscience reports, BSR20180475 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Zhang M, Zhang Z, Cui H, Wang R, Fu L. Long non-coding RNA FENDRR inhibits NSCLC cell growth and aggressiveness by sponging miR-761. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2018;22:8324–8332. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201812_16530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He W, et al. Downregulation of long noncoding RNA FENDRR predicts poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Oncology letters. 2019;17:103–112. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li S, et al. Exploring functions of long noncoding RNAs across multiple cancers through co-expression network. Scientific reports. 2017;7:754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00856-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang X, Zhao H, Qian X, Qiu J. MiR-20a in cell-free urine as a potential diagnostic biomarker for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a Chinese population-based study. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2018;11:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee E, et al. Identification of microR-106b as a prognostic biomarker of p53-like bladder cancers by ActMiR. Oncogene. 2018;37:5858. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lombard AP, et al. miR-148a dependent apoptosis of bladder cancer cells is mediated in part by the epigenetic modifier DNMT1. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2016;55:757–767. doi: 10.1002/mc.22319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juracek, J. et al. In Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. (Elsevier).

- 57.Huang H, et al. Lnc RNA NR 2F1-AS 1 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma oxaliplatin resistance by targeting ABCC 1 via miR-363. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2018;22:3238–3245. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ratert N, et al. Reference miRNAs for miRNAome analysis of urothelial carcinomas. PloS one. 2012;7:e39309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geng J, et al. MicroRNA-365a-3p promotes tumor growth and metastasis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncology reports. 2016;35:2017–2026. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, Wang X, Wu G, Hou D, Hu Q. MiR-365b-3p, down-regulated in retinoblastoma, regulates cell cycle progression and apoptosis of human retinoblastoma cells by targeting PAX6. FEBS letters. 2013;587:1779–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kolesnikov N, et al. ArrayExpress update—simplifying data submissions. Nucleic acids research. 2014;43:D1113–D1116. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hedegaard J, et al. Comprehensive transcriptional analysis of early-stage urothelial carcinoma. Cancer cell. 2016;30:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okholm TLH, et al. Circular RNA expression is abundant and correlated to aggressiveness in early-stage bladder cancer. NPJ genomic medicine. 2017;2:36. doi: 10.1038/s41525-017-0038-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng D-L, Xiang Y-Y, Ji L-J, Lu X-J. Competing endogenous RNA interplay in cancer: mechanism, methodology, and perspectives. Tumor Biology. 2015;36:479–488. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3093-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kinsella, R. J. et al. Ensembl BioMarts: a hub for data retrieval across taxonomic space. Database2011 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Kersey PJ, et al. Ensembl Genomes 2018: an integrated omics infrastructure for non-vertebrate species. Nucleic acids research. 2017;46:D802–D808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li X, et al. A comparison of per sample global scaling and per gene normalization methods for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. PloS one. 2017;12:e0176185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome biology. 2010;11:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein–protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic acids research, gkw937 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Page, L., Brin, S., Motwani, R. & Winograd, T. The PageRank citation ranking: Bringing order to the web. (Stanford InfoLab, 1999).

- 72.Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Systems. 2006;1695:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vlachos IS, et al. DIANA-TarBase v7. 0: indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA: mRNA interactions. Nucleic acids research. 2014;43:D153–D159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chou C-H, et al. miRTarBase update 2018: a resource for experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic acids research. 2017;46:D296–D302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yi Y, et al. RAID v2. 0: an updated resource of RNA-associated interactions across organisms. Nucleic acids research. 2016;45:D115–D118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paraskevopoulou MD, et al. DIANA-LncBase v2: indexing microRNA targets on non-coding transcripts. Nucleic acids research. 2015;44:D231–D238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li J-H, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu L-H, Yang J-H. starBase v2. 0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein–RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic acids research. 2013;42:D92–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morris JH, et al. clusterMaker: a multi-algorithm clustering plugin for Cytoscape. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12:436. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:W305–W311. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tang Y, Li M, Wang J, Pan Y, Wu F-X. CytoNCA: a cytoscape plugin for centrality analysis and evaluation of protein interaction networks. Biosystems. 2015;127:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murtagh F, Legendre P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? Journal of classification. 2014;31:274–295. doi: 10.1007/s00357-014-9161-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meyer, D., Dimitriadou, E., Hornik, K., Weingessel, A. & Leisch, F. (2015).

- 85.Sachs, M. C. plotROC: A Tool for Plotting ROC Curves. Journal of Statistical Software79 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. (Springer, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1 (Supplementary Figures and Tables)

Supplementary file 2 (mRNAs Disease enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 3 (mRNAs BP enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 4 (mRNAs Pathway enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 5 (mRNAs PubMed enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 6 (DNR-Ta network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 7 (DNR-T1 network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 8 (PPR-Ta network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 9 (PPR-T1 network modules enrichment analysis results)

Supplementary file 10 (MEG3 module enrichment analysis results)