Abstract

The progress of schizophrenia at various stages is an intriguing question, which has been explored to some degree using single-modality brain imaging data, e.g. gray matter (GM) or functional connectivity (FC). However it remains unclear how those changes from different modalities are correlated with each other and if the sensitivity to duration of illness and disease stages across modalities is different. In this work, we jointly analyzed FC, GM volume and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) data of 159 individuals including healthy controls (HC), drug-naïve first-episode schizophrenia (FESZ) and chronic schizophrenia patients (CSZ), aiming to evaluate the links among SNP, FC and GM patterns, and their sensitivity to duration of illness and disease stages in schizophrenia. Our results suggested: 1) both GM and FC highlighted impairments in hippocampal, temporal gyrus and cerebellum in schizophrenia, which were significantly correlated with genes like SATB2, GABBR2, PDE4B, CACNA1C etc. 2) GM and FC presented gradually decrease trend (HC > FESZ>CSZ), while SNP indicated a non-gradual variation trend with un-significant group difference observed between FESZ and CSZ; 3) Group difference between HC and FESZ of FC was more remarkable than GM, and FC presented a stronger negative correlation with duration of illness than GM (p = 0.0006). Collectively, these results highlight the benefit of leveraging multimodal data and provide additional clues regarding the impact of mental illness at various disease stages.

Keywords: Multimodal fusion, SNP-FC-GM, Schizophrenia stages, Sensitivity, Duration of illness, ICA

Highlights

-

•

Investigation of linked SNP, GM and FC pattern through parallel ICA method;

-

•

SNP indicated a non-gradual variation trend, highlighted genes like GABBR2 etc.;

-

•

GM and FC exhibited greater deficits at late disease stages (HC > FESZ>CSZ);

-

•

FC presented a stronger negative correlation with duration of illness than GM.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a severe mental illness with high heritability, as well as structural and functional brain impairments. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) from Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) have announced landmark findings (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, 2014), which highlighted a list of susceptible loci. The disease-related abnormalities in brain regions were also demonstrated by many previous studies. For instance, gray matter (GM) volumes of the temporal and prefrontal gyrus were largely reported to be impaired (Asami et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2018a; Sui et al., 2018). Functional connectivity (FC) computed from functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data, which measures interregional temporal correlations of blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal fluctuations, has been reported disabilities involving a number of brain regions, including the frontal lobe, sensory-motor areas, limbic structures and temporal gyrus(Kaufmann et al., 2015; Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2005; Venkataraman et al., 2012).

As different modalities may be related to each other constituting complementary observations of the same phenomenon, many multimodal methods have been developed and applied into analysis of mental disease (Chen et al., 2012; Liu and Calhoun, 2014; Liu et al., 2019; Meng et al., 2017; Sui et al., 2012). For example, Sui et al. developed a multimodal canonical correlation analysis plus joint independent component analysis (mCCA+jICA) method to reveal that GM density abnormalities in default model network (DMN) were related to white-matter impairments in anterior thalamic radiation in schizophrenia (Sui et al., 2013). Chen et al. used a parallel independent component analysis (para-ICA) method to reveal that higher activation in precentral and postcentral gyri was observed in SZ with higher loadings of the linked SNP component (Chen et al., 2012). Nervertheless, there are few studies combining structural, functional and genomic data to analyze schizophrenia.

Moreover, it's still not clear whether there are progressive changes in each modality and the time at which for changes in different modalities are first evident. Previous studies have explored the progressive changes primarily based on single modality. For example, the progressive decreases of GM volumes were pronounced mainy in the temporal and prefrontal gyrus, while increase in the lateral ventricle (Hilleke and Hulshoff Pol, 2008). Another recent study consisting of 39 medication naïve, first-episode schizophrenia and 31 matched controls revealed that first-episode patients presented reduced global efficiency and decreased regional nodal efficiency in hippocampal and precuneus (Meiling Li et al., 2019). Li et al. demonstrated that 90% of the FC changes during the first-episode stage of SZ were centered on the inferior frontal gyrus, while more thalamus-related connectivity were extended to show FC differences in chronic SZ patients (Li et al., 2017a). However, the direct comparison of progressive impairments among different modalities are not largely explored. Based on the linked SNP-FC-GM pattern identified from the multimodal fusion method, we can further compare the modality-specific sensitivity to the disease progression.

Overall, in this study, we performed a multimodal analysis (Vergara et al., 2014) of first-episode SZ patients (FESZ), chronic SZ patients (CSZ) and healthy controls (HC) with three features, i.e., GM volume, FC and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), aiming to evaluate the links among the three modalities, and their association with duration of illness (DOI) and disease stages. Note that we preselected SNPs from PGC's SCZ2 database based on the p-value, while these SNPs are not functionally homogeneous. Since our recent study has proved that no reliable SNP-imaging association was noted in the polygenic risk score (PGRS) analyses when calculating PGRS on SNPs with high heterogeneity (Chen et al., 2019). The multimodal data-driven method would slove this by computing subgroups of all SNPs first and then inverstigate the associated structural and functional brain impairments based on the subgroups. These subgroup SNPs are more likely to converge within brain regions. We hypothesized that a significant correlated SNP-FC-GM pattern would be revealed, as well as significant group differences among HC, FESZ and CSZ in each modality. More importantly, different sensitivity to DOI and disease stages (i.e., the order of feature impairment) would be revealed for different modalities, which may provide us additional clues regarding the impact of mental illness at various disease stages.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

159 subjects were recruited from Wuxi Mental Health Center, consisting of eighty-seven HC, twenty drug-naïve FESZs and fifty-two CSZs. Table 1 describes the demographic information of the data. Patients who have DOI ≤ 2 years were definded as FESZ patients (0.96 ± 0.85), others were identified as chronic patients (20.63 ± 9.84). Subjects were excluded if they had any current or past neurological illness, substance abuse or head injury resulting in loss of consciousness. All the patients were diagnosed according to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria by at least two qualified psychiatrists.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the subjects in the present study.

| Demographics | HC | FESZ | CSZ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 87 | 20 | 52 | ||

| Gender | M/F | 47/40 | 10/10 | 30/22 | 0.83 |

| Age (y) | Mean ± SD | 39.91 ± 14.84 | 33.60 ± 10.80 | 46.12 ± 11.38 | 0.0011 |

| Education | Mean ± SD | 12.67 ± 4.28 | 10.65 ± 4.65 | 10.75 ± 2.69 | 0.0091 |

| Duration of Illness (y) | Mean ± SD | NA | 0.96 ± 0.85 | 20.63 ± 9.84 | |

| Chlorpromazine Equivalent | Mean ± SD | NA | Drug-naïve | 17.26 ± 9.44 | |

| PANSS positive | Mean ± SD | NA | 27.8 ± 4.64 | 19.62 ± 3.82 | 9.20E-08 |

| PANSS negative | Mean ± SD | NA | 19.65 ± 4.78 | 24.40 ± 3.52 | 3.87E-04 |

| PANSS general | Mean ± SD | NA | 46.45 ± 7.49 | 41.77 ± 5.11 | 0.016 |

Note: Chlorpromazine equivalent = Chlorpromazine total (standardized current dose of antipsychotic medication). P values represent the results of chi-square test for gender, analysis of variance (ANOVA) test for age and education, two sample t-test for PANSS scores. HC: healthy control subjects; FESZ: first-episode schizophrenia; CSZ: chronic schizophrenia; F: female; M: male; NA: not applicable.

2.2. Data collection

All subjects were scanned by structural MRI and resting-state functional MRI on a 3.0-Tesla Magnetom TIM Trio (Siemens Medical System) at the Department of Medical Imaging, Wuxi People's Hospital, Nanjing Medical University. Foam pads were used to reduce head motion and scanner noise. Prior to the scan, the subjects were instructed to keep their eyes closed, relax but not fall asleep, and move as little as possible during data acquisition. fMRI: Resting-state scans were acquired using a single-shot gradient-echo echo-planar-imaging sequence as (Tian et al., 2016) with the following parameters: TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, matrix size = 64 × 64, FOV = 220 × 220 mm2, 33 axial slices, slice thickness = 4 mm, acquisition voxel size = 3.4 × 3.4 × 4 mm3, resulting in 240 volumes. sMRI: Three-dimensional T1-weighted images were acquired by employing a 3D-MPRAGE sequence as (Tian et al., 2016) with the following parameters: time repetition (TR) = 2530 ms, time echo (TE) = 3.44 ms, flip angle = 7°, matrix size = 256 × 256, field of view (FOV) = 256 × 256 mm2, 192 sagittal slices, slice thickness = 1 mm, acquisition voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, total acquisition time = 649 s.

All participants provided blood samples for genetic analysis. Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted according to the standard protocol by protease K digestion, phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Afterwards, whole-genome genotyping was conducted on 571,054 loci using Illumina human PsychArray-24.

2.3. Data preprocessing

The structural MRI data and functional MRI data were preprocessed using the SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8) voxel based morphometry module and the Brant software (http://brant.brainnetome.org/en/latest/, Xu et al., 2018), respectively (see supplementary file for more details). A mask for the preprocessed structural data was then generated to include voxels with a mean value larger than 0.2 across all the subjects (Sui et al., 2015). Based on the 116 × 116 automatic anatomical labelling (AAL) atlas, FC network was constructed upon computing pearson correlation of averaged BOLD signals between all pairs of regions, resulting in 6786 edges. The genetic data were preprocessed using PLINK following the quality control procedures in (Anderson et al., 2010; Purcell et al., 2007) and further overlaped with PGC's SCZ2 database (p < 0.01), resulting in 4937 SNPs (see supplementary file). Discrete numbers were assigned to the categorical genotypes: 0 for no minor allele, 1 for one minor allele, and 2 for two minor alleles.

Accordingly, the three feature matrices included: FC (subjects by voxels: 159 × 6786), GM (subjects by voxels: 159 × 77,122) and SNPs (subjects by alleles:159 × 4937). The feature matrices were then normalized to ensure that all modalities had the same average sum-of-squares (computed across all subjects and all voxels/SNPs for each modality). Medication information (chlorpromazine equivalent) was regressed out for the chronic patients prior to additional analyses.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Three-way para-ICA

We firstly applied three-way para-ICA to identify a linked SNP-FC-GM pattern as shown in Fig. 1. Three-way para-ICA is a multivariate association analysis method that estimates maximally independent components within each modality using Infomax ICA separately and maximizes the sum of pair-wise correlations between modalities (Method details are provided in the supplementary file) (Luo et al., 2018b; Vergara et al., 2014). The code is open through the Fusion ICA Toolbox (FIT, http://mialab.mrn.org/software/fit). The number of components was measured to be 14 for FC and GM modalitites through a modified minimum description length (MDL) criterion (Li et al., 2007), an efficient method as discussed in previous ICA associated studies (Calhoun et al., 2001; Calhoun and Sui, 2016; Du et al., 2016). A consistency-based method was used to identify number of components for the SNP modality (Chen et al., 2012), which ran ICA decompositions across a range of numbers of components and determined the comoponent number with the most reliable results (in our case the final model order was estimated to be 6).

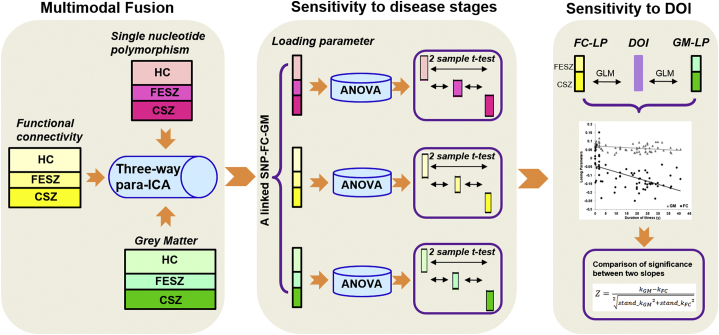

Fig. 1.

Analysis pipeline of the study. We firstly applied three-way para-ICA on the healthy controls (HC), first-episode schizophrenia (FESZ) and chronic schizophrenia (CSZ) subjects with three modalities [Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), functional connectivity (FC) and gray matter (GM)] to identify a linked SNP-FC-GM pattern. Afterwards, ANOVA analysis and two sample t-test were used to measure the group difference across groups for the linked SNP-FC-GM pattern. We further plotted the relationship between the identified imaging modalities and duration of illness (DOI), and used the slopes to compare sensitivity for FC and GM.

2.4.2. Correlation and group difference analysis

Cross correlations among the loading parameters of the three modalities were assessed, and the significant levels were adjusted using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. To measure the consistency of the identified joint pattern across participants, we applied a ten-fold cross validation method to replicate the associations (Chen et al., 2012). Moreover, in order to evaluate the stability of the linked SNP-FC-GM pattern, we conducted 1000 permutation tests to investigate the possibility of overfitting. Particularly, we randomly permuted subjects of all the three modalities and ran three-way para-ICA again on the permuted subjects. Then we extracted the top correlated SNP-FC-GM pair in each of the 1000 permutation tests and calculated the tail probability to evaluate the significance level of the identified SNP-FC-GM association. Finally, the sptial maps of the SNP-FC-SNP pattern were transformed to Z scores and the top contributing brain regions, FC and SNPs were selected and plotted.

2.4.3. Sensitivity to disease stages and DOI

To investigate the different sensitivities to diease stages and DOI, we applied analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis and two sample t-test to measure the group difference across different disease stages within each modality for the linked SNP-FC-GM pattern (Fig. 1). Then we calculated the relationship between the identified imaging modalities and DOI, and used Z value to compare the difference between slopes of the two modalities. Specifically, we first applied generalized linear regression (GLM) model to identify a regression line for the relationship between imaging modalitites and DOI. Then the slope of the regression line was the corresponding beta value of the loading parameter of each modality (kGM for the GM modality and kFC for the FC modality). Z value was computed as the difference between the two slopes divided by the standard error of the difference between the slopes. As the GLM model gave us the standard error of each slope (stand_kGM for the GM modality and stand_kFC for the FC modality), then the standard error of the difference between the two slopes can be computed as . Then we calculated the Z value as Eq. (1):

| (1) |

Afterwards, we computed the two-tailed p-value corresponding to the Z value to evaluate the significance of the two slopes.

2.4.4. Genetic pathway analysis

After converting the spatial map of the SNP component to Z scores, the high-ranking SNPs (|Z| > 2) were annotated to genes. To further interpret the relationship between the SNP component and schizophrenia, we fed these top contributing genes to the WebGestalt software for Gene Ontology (GO) analysis (Wang et al., 2013), which used a hypergenometrix test to detect overrepresentation of the genes among the whole genome in a GO category.

3. Results

3.1. SNP-FC-GM multivariate linkage

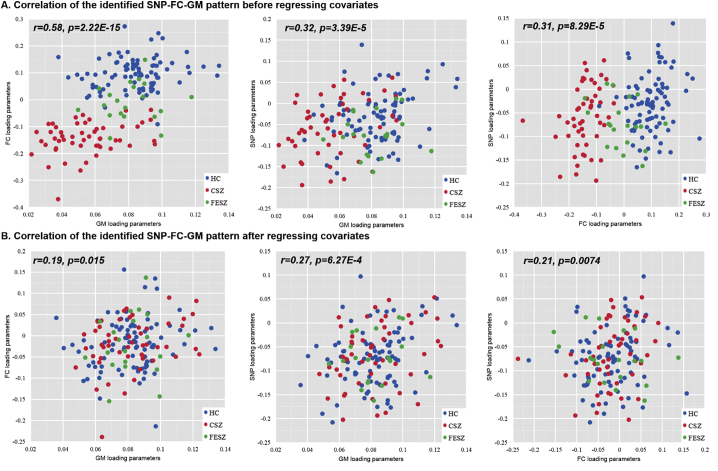

The strongest connected SNP-FC-GM triplet from the three-way para-ICA was identified, which presented significant pair-wise correlations (FC-GM: r = 0.58, p < 10−12; SNP-FC: r = 0.31, p = 8.83 × 10−5; SNP-GM: r = 0.32, p = 3.39 × 10−5, passing the Bonferroni correction) as shown in Fig. 2A. Ten-fold analysis revealed that the correlations were stable with averge correlation of 0.58 ± 0.08(FC-GM), 0.28±0.04(SNP-FC), 0.27±0.06(SNP-GM). Permutation tests further indicated the significance of the links with empirical p-values of 0.001(FC-GM), 0.03(SNP-FC), 0.01(SNP-GM).

Fig. 2.

The pairwise correlation plots of the identified SNP-FC-GM component. (A) The correlation among FC, GM and SNP modalities before regressing out any variables. (B) The correlation among FC, GM and SNP modalities after regressing out age, gender, education and diagnosis. Note: The blue dots represent the healthy controls(HC). The red dots represent the chronic schizophrenia patients (CSZ). The green dots represent the first-episode schizophrenia patients(FESZ).

Partial correlations of the linked SNP-FC-GM pattern were still significant when controlling for diagnosis, age, education and gender (SNP-FC: r = 0.21, p = 0.0074; SNP-GM: r = 0.27, p = 6.27 × 10−4, FC-GM: r = 0.19, p = 0.015) as shown in Fig. 2B, passing Bonferroni correction. The positive correlations of SNP-FC and SNP-GM indicated that higher allele counts for the positively contributing SNPs were associated with an increase of both FC and GM; higher allele counts for the negatively contributing SNPs were associated with a decrease of both FC and GM. The positive correlations between FC and GM revealed that FC decrease was related with GM volume reduction.

3.2. Different sensitivity to disease stages and DOI

Group differences across HC, FESZ and CSZ measured by ANOVA in FC (p = 6.09 × 10−49), GM(p = 2.82 × 10−15) and SNP(p = 0.0024) were significant. Fig. 3A further despicts the results of two sample t-test comparison between groups within each modality. Both FC and GM displayed evidence of greater deficits at late disease stage compare to healthy controls and early stage (HC > FESZ>CSZ). Notably, significant group differences were observed in all pairs for the FC component (HC-FESZ: p = 2.26 × 10−6, HC-CSZ: p < 1 × 10–10, FESZ-CSZ: p = 2.05 × 10−8), while the GM component only presented obvious significance in HC-CSZ (p < 1 × 10−10) and FESZ-CSZ (p = 5.34 × 10−7). Compared to the imaging modalities, no significant group difference between FESZ and CSZ in the SNP component was revealed, but group difference between HC and FESZ (p = 0.0023), or HC and CSZ (p = 0.0083) was significant.

Fig. 3.

Different sensitivity to disease stages and DOI. (A) ANOVA and two-sample t-tests within each modality. Note: The p-values display results of ANOVA analysis. The red violin plot represents healthy controls (HC). The green violin plot represents first-episode schizophrenia patients (FESZ). The blue violin plot represents the chronic schizophrenia patients (CSZ). *represent 0.00001 < p < 0.05, ** represents 1e-5 < p < 1e-10, **represents p < 1e-10. (B)Different sensitivity comparison between the GM and FC modality to DOI. Note: the gray and black dots represent correlation between GM, FC loadings and DOI respectively. The gray and black regression lines represent the slope of the correlation. The two-tailed p-value of the z values between two slopes is significant (p = 0.00063).

Moreover, Fig. 3B displays the relationship between imaging loadings and DOI. FC (k = −0.0036) presented a sharper slope than GM (k = −0.0006), which means FC deteriorates faster than GM with the same DOI. The z-value of the two slopes was −3.42 with a corresponding two-tailed p-value as 0.00063, which indicated that FC presented a stronger negative correlation with DOI than GM.

3.3. The linked imaging modalities

As shown in Fig. 4, the GM component and FC component were converted into Z scores and displayed at |Z| > 2.5. Since the components have been adjusted as HC > SZ on the mean of loading parameters as shown in Fig. 3, the red regions/connections in Fig. 4 indicated higher contribution in HC than SZ, and the blue regions/connections indicated higher contribution in SZ than HC (Sui et al., 2015). Accordingly, GM decrease in patients centered on amygdala, temporal gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, postcentral gyrus, and increase in inferior parietal gyrus and cerebellum as shown in Fig. 4A. The detailed anatomical information of the abnormal brain regions are listed in Table S2. As shown in Fig. 4B, SZ patients present lower FC primarily in amygdala, postcentral, hippocampus/parahippocampus, temporal gyrus, and higher FC primarily in cerebellare and inferior parietal related connectivity.

Fig. 4.

The abnormal brain regions and functional connectivity revealed by three-way para-ICA. (A) Brain regions showing gray matter abnormalities in the SNP-FC-GM pattern. The red regions represent gray matter decrease in SZ while the blue regions represent gray matter increase in SZ. (B) Imparied FC identified from the SNP-FC-GM pattern. The red connecting lines represent FC decrease in SZ, while the blue connecting lines represent FC increase in SZ.

3.4. The joint SNP component and pathway analysis

Similarly, the SNP component was also transformed to Z scores and visualized at |Z| > 2, which highlighted 258 risk SNPs as listed in Table S2. Fig. 5A displays a Manhattan plot for the SNP component. After annotating the 258 high-ranking SNPs, 101 genes were revealed, including SATB2, GABBR2, PDE4B and CACNA1C et al. Fig. 5B depicts the significant GO results, including cell junction, perinuclear region of cytoplasm, neuron part, synapse, postsynapse, neuron projection, plasma membrane receptor complex, postsynaptic density and postsynaptic specialization. Note that the p-vlaues shown in Fig. 5B were all FDR corrected. The included genes for each GO function are listed in Table S3.

Fig. 5.

Mahattan plot and GO analysis of the joint SNP component. (A) Manhattan plot of the identified SNP component. (B) GO analysis results of the high-ranking SNP with |Z-scores| > 2; P-values are all FDR corrected.

4. Discussion

This study first jointly analyzed correlation between FC, GM volume and SNP in schizophrenia and further evaluated the different sensitivity to DOI and disease stages for imaging modalities. Results revealed a linked SNP-FC-GM pattern, with significant group differences among HC, FESZ and CSZ of each modality. Impairments of GM and FC were centered on hippocampal, temporal gyrus and cerebellum in schizophrenia. These changes were further significantly associated with SNPs residing in genes like SATB2, GABBR2, PDE4B and CACNA1C et al., involved in pathways of cell junction formation, and synapse and neuron projection. Moreover, post-hoc analysis revealed that both GM and FC presented greater deficits at later disease stages (HC > FESZ>CSZ), and FC presented a stronger negative correlation with DOI than GM.

4.1. Linked SNP-FC-GM pattern

We first identified the most significantly correlated SNP-FC-GM pattern using three-way para-ICA, which passed the significant levels after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Then partial correlation on the identified SNP-FC-GM pattern (using diagnosis, age, education and gender as covariates) revealed a weak but still significant correlation among the three modalities. We found decreased GM volume in the temporal gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, postcentral gyrus and amygdala-hippocampus complex, consistent with the previous studies in (Glahn et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 2009), coaltered with the low FC strength in prefrontal, temporal, hippocampus/parahippocampus and amygdala (Lawrie et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2008). Increased GM were revealed mainly in cerebellum and inferior parietal lobule(Salgado-Pineda et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2002) in patients, as well as increased FC in these two brain regions(Alalade et al., 2011; Venkataraman et al., 2012). Shared impaired brain regions between GM and FC modalities focused on hippocampus, temporal gyrus, cerebellum and parietal gyrus. The decreased GM volumes of temporal gyrus are implicated for the impairment in sensory integration, storage of language and voice information, and higher-order cognitive functions (Pobric et al., 2007). Amygdala and hippocampus are critical for memory functions and affect perception(Yoshida et al., 2009). The parahippocampal gyrus is part of the medial temporal lobe, which receives input from heteromodal association areas of the cortex and projects into the limbic circuit for information transmission (McDonald et al., 2000). The cerebellum has been revealed to primarily coordinate motor activity for years and viewed as a key cognitive region in the brain which is impaired in schizophrenia by the previous study(Andreasen and Pierson, 2008). The parietal lobe is important in processes of language, attention and spatial working memory, which are likely to be disturbed in schizophrenia (Tek et al., 2002).

The joint SNP component primarily highlighted SZ-susceptible genes including PDE4B, EGF, SATB2, PPP1R16B, GABBR2 and CACNA1C etc., which have been reported to be significantly associated with schizophrenia in previous studies. For example, PDE4B interacts with DISC1 to regulate cAMP signaling, which is impared in schizophrenia (Millar et al., 2005). Patients with mutations or deletions within the SATB2 locus exhibit severe learning difficulties and profound mental retardation (Lieden et al., 2014). Devor et al. has found PP1 subunits including PPP1R16B plays a central role in the integration of fast and slow neurotransmission(Devor et al., 2017). The CACNA1C is also revealed as a SZ-susceptible gene in (Green et al., 2010). Further GO analysis of the annotated top contributing genes revealed a significant enrichment of cell junction, synapse and neuron projection. Consistently, reduced neuron projection of schizophrenia patients in the hippocampus and thalamocortex has also been revealed in previous studies (Danos et al., 1998; Heckers and Konradi, 2002). Synapse primarily participates in the information transmission process (Fukata and Fukata, 2010). Impairment of synaptic transmission during childhood and adolescence would lead to altered synapse formation or pruning (Mirnics et al., 2001). Moreover, the SNP component was significantly correlated with the imaging impairments, supported by previous studies. For example, GABBR1 and GABBR2 were revealed to be altered significantly in the lateral cerebellum of SZ patients (Thuras et al., 2013). SATB2 has been reported to control the hippocampal levels of a large cohort of miRNAs, many of which are implicated in synaptic plastic and memory formation(Jaitner et al., 2016). The CACNA1C gene is widely expressed in the entire nervous system, especially the thalamus and hippocampus areas (Narayanan et al., 2010). Decreased expression of PDE4B has been observed in the tissues of Brodmann's area 6 of frontal cortex and cerebellum(Fatemi et al., 2008).

4.2. Different sensitivity to disease stage and DOI

Post-hoc 2-sample t-test revealed that GM impairments in FESZ were not significant compared to HC, while CSZ exhibited significant group difference compared to both FESZ and HC. Unlike GM, FC presented significant group difference between FESZ and HC, and a larger impairment in CSZ. We have noticed that there were some literatures in schizophrenia stating that notable GM and FC deficits were revealed in the early stage of the disease. However, in current work, we only observed moderately decreased GM in FESZ, due to the following potential reasons.1) The first-episode patients collected in current study have a relatively short duration of illness (≤ 2 years), less than those FESZ reported with DOI≤5 years, and previous studies (Jiang et al., 2018; Klauser et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2018) also reported un-significant GMV reduction in the high-risking patients and progressive GMV reductions in schizophrenia patients, supporting our findings. 2) Earlier age of onset of schizophrenia has been reported to be associated with larger regional GM deficits(Torres et al., 2016) and worse outcome(Clemmensen et al., 2012). In this study, the FESZ patients are primarily middle-aged adults (33.60 ± 10.80 years old) rather than adolescents, which may infer less GM impairments in the patients compared to other studies. 3) We only focused on the subgroups of the GM and FC data which were simultaneously related with the SNP cluster. For example, lower gray matter volumes in FESZ reported in previous studies were mostly found in the anterior cingulate, insula, caudate and putamen (Fan et al., 2019; Radua et al., 2012). While in this study, the peak regions were observed in the amygdala, temporal pole, parahippocampal gyrus, postcentral gyrus, primarily reported in chronic patients (Chan et al., 2011; Shepherd et al., 2012), which may lead to the un-significant group difference in FESZ.

Notably, these impaired regions were also identified in the FC component, which presented significant group difference between FESZ and HC. Previous studies supported this by reporting abnormalities in these regions at first-episode stages, for example the middle temporal gyrus (Lawrie et al., 2002; Li et al., 2017a; Zhang et al., 2014) and parahippocampus areas (Du et al., 2018; McGuire et al., 2009). Accordingly, we suggested that functional connectivity presented a greater gradient of decline to duration of illness than GMV in specific brain regions at the early stage of the disease, including the parahippocampus, inferior temporal gyrus and postcentral gyrus. More importantly, even though these results are statistically significant, further validation based on longitude subjects and larger dataset were also awaited.

A limitation in this study is that all the chronic patients received medication, and even though we have regressed out the medication effect before conducting analysis, the differences between FESZ and chronic patients could still be influenced by the antipsychotic medication and/or symptom severity. A second limitation is that our sample size, especially FESZ, is relatively small and the absence of a replication dataset with all 3 modalities; however, these findings still provide important clues for the study of schizophrenia progression. Another limitation is that we preselected the risk SNPs based on the PGC's GWAS results rather than Chinese Han GWAS study. However, Li et al. has recently demonstrated that the top risk loci from PGC's GWAS are largely consistent between the two populations(Li et al., 2017b), which provide support for our preselecting SNPs from PGC and analyzing them on the Chinese Han dataset. Future work should validate the results using Chinese GWAS results when the summary data of the Chinese GWAS study is available to the public.

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to evaluate the associations between the SNP-FC-GM patterns in schizophrenia and compare the sensitivity to DOI and disease stages for imaging modalities. Results suggested that: 1) GM volume impairments and FC abnormalities in hippocampus, temporal gyrus, parietal and cerebellum are revealed in schizophrenia, which were associated with genetic factors e.g., SATB2, GABBR2, PDE4B, CACNA1C etc. 2) GM and FC showed evidence of greater deficits at later disease stages (HC > FESZ>CSZ), while SNP indicated a non-gradual variation trend with un-significant group difference observed between FESZ and CSZ; 3) Group difference between HC and FESZ of FC was more obvious than GM, and FC presented a stronger negative correlation with DOI than GM. Collectively, these results deep our understandings of impaired SNP-FC-GM correlation towards schizophrenia and provide important clues regarding the impact of mental illness at various disease stages.

Fundings

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61773380, 81871081), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDB32040100), and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. Z181100001518005), the Primary Research & Development Plan of Jiangsu Province (BE2016630), National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0112000), and NIH grants (R56MH117107, R01EB005846, P20GM103472, R01REB020407).

Author contribution

JS and NL designed the research; NL conducted the analyses; NL and JS wrote the paper. LT and FZ recruited and collected the data. The remaining authors contributed to paper revision and discussion.

Declarations of interests

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

All subjects provided written informed consent under institutional board approval. All procedures involving human participants performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional or national research committee and Helsinki declaration.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101887.

Contributor Information

Fuquan Zhang, Email: zhangfq@njmu.edu.cn.

Jing Sui, Email: kittysj@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Alalade E., Denny K., Potter G., Steffens D., Wang L. Altered cerebellar-cerebral functional connectivity in geriatric depression. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C.A., Pettersson F.H., Clarke G.M., Cardon L.R., Morris A.P., Zondervan K.T. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5:1564–1573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N.C., Pierson R. The role of the cerebellum in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asami T., Bouix S., Whitford T.J., Shenton M.E., Salisbury D.F., McCarley R.W. Longitudinal loss of gray matter volume in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: DARTEL automated analysis and ROI validation. Neuroimage. 2012;59:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun V.D., Sui J. Multimodal fusion of brain imaging data: a key to finding the missing link(s) in complex mental illness. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2016;1:230–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun V.D., Adali T., Pearlson G.D., Pekar J.J. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2001;14:140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R.C.K., Di X., McAlonan G.M., Gong Q.Y. Brain anatomical abnormalities in high-risk individuals, first-episode, and chronic schizophrenia: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of illness progression. Schizophr. Bull. 2011;37:177–188. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Calhoun V.D., Pearlson G.D., Ehrlich S., Turner J.A., Ho B.C., Wassink T.H., Michael A.M., Liu J. Multifaceted genomic risk for brain function in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2012;61:866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.Y., Calhoun V.D., Lin D.D., Perrone-Bizzozero N.I., Bustillo J.R., Pearlson G.D., Potkin S.G., van Erp T.G.M., Macciardi F., Ehrlich S., Ho B.C., Sponheim S.R., Wang L., Stephen J.M., Mayer A.R., Hanlon F.M., Jung R.E., Clementz B.A., Keshavan M.S., Gershon E.S., Sweeney J.A., Tamminga C.A., Andreassen O.A., Agartz I., Westlye L.T., Sui J., Du Y.H., Turner J.A., Liu J.Y. Shared genetic risk of schizophrenia and gray matter reduction in 6p22.1. Schizophr. Bull. 2019;45:222–232. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmensen L., Vernal D.L., Steinhausen H.C. A systematic review of the long-term outcome of early onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danos P., Baumann B., Bernstein H.G., Franz M., Stauch R., Northoff G., Krell D., Falkai P., Bogerts B. Schizophrenia and anteroventral thalamic nucleus: selective decrease of parvalbumin-immunoreactive thalamocortical projection neurons. Psychiatry Res. 1998;82:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(97)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor A., Andreassen O.A., Wang Y., Maki-Marttunen T., Smeland O.B., Fan C.C., Schork A.J., Holland D., Thompson W.K., Witoelar A., Chen C.H., Desikan R.S., McEvoy L.K., Djurovic S., Greengard P., Svenningsson P., Einevoll G.T., Dale A.M. Genetic evidence for role of integration of fast and slow neurotransmission in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:792–801. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y., Allen E.A., He H., Sui J., Wu L., Calhoun V.D. Artifact removal in the context of group ICA: A comparison of single-subject and group approaches. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016;37:1005–1025. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y., Fryer S.L., Fu Z., Lin D., Sui J., Chen J., Damaraju E., Mennigen E., Stuart B., Loewy R.L., Mathalon D.H., Calhoun V.D. Dynamic functional connectivity impairments in early schizophrenia and clinical high-risk for psychosis. Neuroimage. 2018;180:632–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F., Xiang H., Tan S., Yang F., Fan H., Guo H., Kochunov P., Wang Z., Hong L.E., Tan Y. Subcortical structures and cognitive dysfunction in first episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging. 2019;286:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi S.H., King D.P., Reutiman T.J., Folsom T.D., Laurence J.A., Lee S., Fan Y.T., Paciga S.A., Conti M., Menniti F.S. PDE4B polymorphisms and decreased PDE4B expression are associated with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2008;101:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata Y., Fukata M. Protein palmitoylation in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:161–175. doi: 10.1038/nrn2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn D.C., Laird A.R., Ellison-Wright I., Thelen S.M., Robinson J.L., Lancaster J.L., Bullmore E., Fox P.T. Meta-analysis of gray matter anomalies in schizophrenia: application of anatomic likelihood estimation and network analysis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E.K., Grozeva D., Jones I., Jones L., Kirov G., Caesar S., Gordon-Smith K., Fraser C., Forty L., Russell E., Hamshere M.L., Moskvina V., Nikolov I., Farmer A., McGuffin P., Holmans P.A., Owen M.J., O'Donovan M.C., Craddock N., Consor W.T.C.C. The bipolar disorder risk allele at CACNA1C also confers risk of recurrent major depression and of schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2010;15:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckers S., Konradi C. Hippocampal neurons in schizophrenia. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2002;109:891–905. doi: 10.1007/s007020200073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilleke E., Hulshoff Pol R.S.K. What happens after the first episode? a review of progressive brain changes in chronically ill patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2008;34:354–366. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaitner C., Reddy C., Abentung A., Whittle N., Rieder D., Delekate A., Korte M., Jain G., Fischer A., Sananbenesi F., Cera I., Singewald N., Dechant G., Apostolova G. Satb2 determines miRNA expression and long-term memory in the adult central nervous system. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.17361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Luo C., Li X., Duan M., He H., Chen X., Yang H., Gong J., Chang X., Woelfer M., Biswal B.B., Yao D. Progressive reduction in gray matter in patients with schizophrenia assessed with MR imaging by using causal network analysis. Radiology. 2018;287:633–642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017171832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann T., Skatun K.C., Alnaes D., Doan N.T., Duff E.P., Tonnesen S., Roussos E., Ueland T., Aminoff S.R., Lagerberg T.V., Agartz I., Melle I.S., Smith S.M., Andreassen O.A., Westlye L.T. Disintegration of sensorimotor brain networks in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2015;41:1326–1335. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauser P., Zhou J., Lim J.K.W., Poh J.S., Zheng H., Tng H.Y., Krishnan R., Lee J., Keefe R.S.E., Adcock R.A., Wood S.J., Fornito A., Chee M.W.L. Lack of evidence for regional brain volume or cortical thickness abnormalities in youths at clinical high risk for psychosis: findings from the longitudinal youth at risk study. Schizophr. Bull. 2015;41:1285–1293. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie S.M., Buechel C., Whalley H.C., Frith C.D., Friston K.J., Johnstone E.C. Reduced frontotemporal functional connectivity in schizophrenia associated with auditory hallucinations. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;51:1008–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.O., Adali T., Calhoun V.D. Estimating the number of independent components for functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007;28:1251–1266. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Wang Q., Zhang J., Rolls E.T., Yang W., Palaniyappan L., Zhang L., Cheng W., Yao Y., Liu Z., Gong X., Luo Q., Tang Y., Crow T.J., Broome M.R., Xu K., Li C., Wang J., Liu Z., Lu G., Wang F., Feng J. Brain-wide analysis of functional connectivity in first-episode and chronic stages of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2017;43:436–448. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Chen J., Yu H., He L., Xu Y., Zhang D., Yi Q., Li C., Li X., Shen J., Song Z., Ji W., Wang M., Zhou J., Chen B., Liu Y., Wang J., Wang P., Yang P., Wang Q., Feng G., Liu B., Sun W., Li B., He G., Li W., Wan C., Xu Q., Li W., Wen Z., Liu K., Huang F., Ji J., Ripke S., Yue W., Sullivan P.F., O'Donovan M.C., Shi Y. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 30 new susceptibility loci for schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1576–1583. doi: 10.1038/ng.3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieden A., Kvarnung M., Nilssson D., Sahlin E., Lundberg E.S. Intragenic duplication-a novel causative mechanism for SATB2-associated syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2014;164:3083–3087. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.Y., Calhoun V.D. A review of multivariate analyses in imaging genetics. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics. 2014;8 doi: 10.3389/fninf.2014.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Tang Y., Womer F., Fan G., Lu T., Driesen N., Ren L., Wang Y., He Y., Blumberg H.P., Xu K., Wang F. Differentiating patterns of amygdala-frontal functional connectivity in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 2014;40:469–477. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.F., Wang H.Y., Song M., Lv L.X., Cui Y., Liu Y., Fan L.Z., Zuo N.M., Xu K.B., Du Y.H., Yu Q.B., Luo N., Qi S.L., Yang J., Xie S.M., Li J., Chen J., Chen Y.C., Wang H.N., Guo H., Wan P., Yang Y.F., Li P., Lu L., Yan H., Yan J., Wang H.L., Zhang H.X., Zhang D., Calhoun V.D., Jiang T.Z., Sui J. Linked 4-way multimodal brain differences in schizophrenia in a large chinese han population. Schizophr. Bull. 2019;45:436–449. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo N., Sui J., Chen J.Y., Zhang F.Q., Tian L., Lin D.D., Song M., Calhoun V.D., Cui Y., Vergara V.M., Zheng F.F., Liu J.Y., Yang Z.Y., Zuo N.M., Fan L.Z., Xu K.B., Liu S.F., Li J., Xu Y., Liu S., Lv L.X., Chen J., Chen Y.C., Guo H., Li P., Lu L., Wan P., Wang H.N., Wang H.L., Yan H., Yan J., Yang Y.F., Zhang H.X., Zhang D., Jiang T.Z. A schizophrenia-related genetic-brain-cognition pathway revealed in a large Chinese population. Ebiomedicine. 2018;37:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo N., Tian L., Calhoun V.D., Chen J., Lin D., Vergara V.M., Rao S., Zhang F., Sui J. 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 2018. Exploring different impaired speed of genetic-related brain function and structures in schizophrenic progress using multimodal analysis*; pp. 4126–4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B., Highley J.R., Walker M.A., Herron B.M., Cooper S.J., Esiri M.M., Crow T.J. Anomalous asymmetry of fusiform and parahippocampal gyrus gray matter in schizophrenia: A postmortem study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:40–47. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire P., Benetti S., Mechelli A., Picchioni M., Broome M., Williams S. Functional integration between the posterior hippocampus and prefrontal cortex is impaired in both first episode schizophrenia and the at risk mental state. Brain. 2009;132:2426–2436. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiling Li B.B., Zheng Junjie, Zhang Yan, Chen Heng, Liao Wei, Duan Xujun, Liu Hesheng, Zhao Jingping, Chen Huafu. Dysregulated maturation of the functional connectome in antipsychotic-naïve, first-episode patients with adolescent-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2019;45:689–697. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Jiang R., Lin D., Bustillo J., Jones T., Chen J., Yu Q., Du Y., Zhang Y., Jiang T., Sui J., Calhoun V.D. Predicting individualized clinical measures by a generalized prediction framework and multimodal fusion of MRI data. Neuroimage. 2017;145:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A.S., Olsen R.K., Kohn P.D., Brown T., Egan M.F., Weinberger D.R., Berman K.F. Regionally specific disturbance of dorsolateral prefrontal-hippocampal functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:379–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar J.K., Pickard B.S., Mackie S., James R., Christie S., Buchanan S.R., Malloy M.P., Chubb J.E., Huston E., Baillie G.S., Thomson P.A., Hill E.V., Brandon N.J., Rain J.C., Camargo L.M., Whiting P.J., Houslay M.D., Blackwood D.H.R., Muir W.J., Porteous D.J. DISC1 and PDE4B are interacting genetic factors in schizophrenia that regulate cAMP signaling. Science. 2005;310:1187–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1112915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirnics K., Middleton F.A., Lewis D.A., Levitt P. Analysis of complex brain disorders with gene expression microarrays: schizophrenia as a disease of the synapse. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01862-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan D., Xi Q., Pfeffer L.M., Jaggar J.H. Mitochondria control functional CaV1.2 expression in smooth muscle cells of cerebral arteries. Circ. Res. 2010;107:631–641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobric G., Jefferies E., Ralph M.A.L. Anterior temporal lobes mediate semantic representation: Mimicking semantic dementia by using rTMS in normal participants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:20137–20141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707383104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radua J., Borgwardt S., Crescini A., Mataix-Cols D., Meyer-Lindenberg A., McGuire P.K., Fusar-Poli P. Multimodal meta-analysis of structural and functional brain changes in first episode psychosis and the effects of antipsychotic medication. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012;36:2325–2333. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Pineda P., Baeza I., Perez-Gomez M., Vendrell P., Junque C., Bargallo N., Bernardo M. Sustained attention impairment correlates to gray matter decreases in first episode neuroleptic-naive schizophrenic patients. Neuroimage. 2003;19:365–375. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, C Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd A.M., Laurens K.R., Matheson S.L., Carr V.J., Green M.J. Systematic meta-review and quality assessment of the structural brain alterations in schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012;36:1342–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Adali T., Yu Q., Chen J., Calhoun V.D. A review of multivariate methods for multimodal fusion of brain imaging data. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2012;204:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., He H., Yu Q., Chen J., Rogers J., Pearlson G.D., Mayer A., Bustillo J., Canive J., Calhoun V.D. Combination of Resting State fMRI, DTI, and sMRI Data to Discriminate Schizophrenia by N-way MCCA + jICA. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013;7:235. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Pearlson G.D., Du Y.H., Yu Q.B., Jones T.R., Chen J.Y., Jiang T.Z., Bustillo J., Calhoun V.D. In search of multimodal neuroimaging biomarkers of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;78:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Qi S.L., van Erp T.G.M., Bustillo J., Jiang R.T., Lin D.D., Turner J.A., Damaraju E., Mayer A.R., Cui Y., Fu Z.N., Du Y.H., Chen J.Y., Potkin S.G., Preda A., Mathalon D.H., Ford J.M., Voyvodic J., Mueller B.A., Belger A., McEwen S.C., O'Leary D.S., McMahon A., Jiang T.Z., Calhoun V.D. Multimodal neuromarkers in schizophrenia via cognition-guided MRI fusion. Nat. Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05432-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M., Nohara S., Hagino H., Kurokawa K., Yotsutsuji T., Kawasaki Y., Takahashi T., Matsui M., Watanabe N., Seto H., Kurachi M. Regional changes in brain gray and white matter in patients with schizophrenia demonstrated with voxel-based analysis of MRI. Schizophr. Res. 2002;55:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tek C., Gold J., Blaxton T., Wilk C., McMahon R.P., Buchanan R.W. Visual perceptual and working memory impairments in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:146–153. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuras P.D.R.R., Fatemi S.H., Folsom T.D. Expression of GABA A α2-, β1-and ɛ-receptors are altered significantly in the lateral cerebellum of subjects with schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 2013;3(9) doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Meng C., Jiang Y., Tang Q., Wang S., Xie X., Fu X., Jin C., Zhang F., Wang J. Abnormal functional connectivity of brain network hubs associated with symptom severity in treatment-naive patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder: a resting-state functional MRI study. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2016;66:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres U.S., Duran F.L.S., Schaufelberger M.S., Crippa J.A.S., Louzã M.R., Sallet P.C., Kanegusuku C.Y.O., Elkis H., Gattaz W.F., Bassitt D.P., Zuardi A.W., Hallak J.E.C., Leite C.C., Castro C.C., Santos A.C., Murray R.M., Busatto G.F. Patterns of regional gray matter loss at different stages of schizophrenia: a multisite, cross-sectional VBM study in first-episode and chronic illness. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2016;12:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman A., Whitford T.J., Westin C.F., Golland P., Kubicki M. Whole brain resting state functional connectivity abnormalities in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2012;139:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara V.M., Ulloa A., Calhoun V.D., Boutte D., Chen J.Y., Liu J.Y. A three-way parallel ICA approach to analyze links among genetics, brain structure and brain function. Neuroimage. 2014;98:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Duncan D., Shi Z., Zhang B. WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W77–W83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright I.C., Rabe-Hesketh S., Woodruff P.W., David A.S., Murray R.M., Bullmore E.T. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:16–25. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhang Y., Yang Y., Lu X., Fang Z., Huang J., Kong L., Chen J., Ning Y., Li X., Wu K. Structural and functional brain abnormalities in drug-naive, first-episode, and chronic patients with schizophrenia: a multimodal MRI study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018;14:2889–2904. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S174356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Kaibin. BRANT: A Versatile and Extendable Resting-State fMRI Toolkit. Frontiers in neuroinformatics. 2018;12:52. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2018.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T., McCarley R.W., Nakamura M., Lee K., Koo M.S., Bouix S., Salisbury D.F., Morra L., Shenton M.E., Niznikiewicz M.A. A prospective longitudinal volumetric MRI study of superior temporal gyrus gray matter and amygdala-hippocampal complex in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2009;113:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Qiu L., Yuan L., Ma H., Ye R., Yu F., Hu P., Dong Y., Wang K. Evidence for progressive brain abnormalities in early schizophrenia: a cross-sectional structural and functional connectivity study. Schizophr. Res. 2014;159:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Shu N., Liu Y., Song M., Hao Y., Liu H., Yu C., Liu Z., Jiang T. Altered resting-state functional connectivity and anatomical connectivity of hippocampus in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2008;100:120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material