Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine whether an early increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) following the deflation of a tourniquet is related to the tourniquet time (TT) or tourniquet pressure (TP) and to identify a safe cut-off value for TT or TP.

Materials and Methods

Patients who underwent elective orthopedic lower-extremity surgery under general anesthesia were randomized into 2 groups: group A (inflation with a pneumatic TP of systolic blood pressure + 100 mm Hg; n = 30) and group B (inflation using the arterial occlusion pressure formula; n = 30). The initial and maximum TPs, TT, and sonographic measurements of optic-nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) and end-tidal CO2 values were taken at specific time points (15 min before the induction of anesthesia, just before, and 5, 10, and 15 min after the tourniquet was deflated).

Results

The initial and maximum TPs were found to be significantly higher in group A than in group B. At 5 min after the tourniquet deflation, there was a significant positive correlation between TT and ONSD (r = 0.57, p = 0.0001). When ONSD ≥5 mm was taken as a standard criterion, the safe cut-off value for the optimal TT was found to be < 67.5 min (sensitivity 87% and specificity 59.5%).

Conclusion

The ICP increase in the early period after tourniquet deflation was well correlated with TT but not with TP. TT of ≥67.5 min was found to be the cut-off value and is considered the starting point of the increase in ICP after tourniquet deflation.

Keywords: Tourniquet, Intracranial pressure, Arterial occlusion pressure, Optic nerve sheath diameter

Significance of the Study

In this study, increases in intracranial pressure (ICP) in the early period after tourniquet deflation are associated with tourniquet time but not with tourniquet pressure. We also found that a tourniquet application time of ≥67.5 min was the cut-off value, and this is considered the starting point of the increase in ICP after tourniquet deflation.

Introduction

Tourniquets are routinely applied in orthopedic extremity surgery due to their advantages [1, 2]. The use of a tourniquet in orthopedic interventions provides a bloodless surgical site, providing protection against surgical complications and shortening the operation time, and consequently shortening the length of hospital stay [3].

Local and systemic complications that develop secondary to a high cuff pressure and a long duration of tourniquet use include nerve damage, vascular injuries, ischemia/reperfusion injury, and increased intracranial pressure (ICP) [4, 5]. In recent years, minimal tourniquet inflation pressure has been used instead of traditional tourniquet pressure (TP) values to reduce complications caused by excessive TP. Bloodless surgical fields can be achieved at a much lower pressure than conventional TP by using a method formulated with arterial occlusion pressure (AOP), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and tissue padding coefficient (KTP) values according to the circumference of the extremity (AOP = [SBP + 10]/KTP) [6, 7].

Studies on the relationship between tourniquet-related complications and tourniquet time (TT) have generally involved experimental animal models, and there are a limited number of human studies in the literature [8, 9]. Studies on healthy volunteers have suggested that the TT should be limited to 2 h [1, 4, 10]. The risk of systemic complications increases with time, especially in patients with morbid obesity, a history of peripheral vascular surgery, and severe left-ventricular dysfunction, as well as in elderly and trauma patients [1]. A high TP causes more metabolite accumulation in the ischemic area, and during the deflation period, more metabolites are released into the systemic circulation. In particular, the increase in carbon dioxide (CO2) from the ischemic metabolic products released during the reperfusion period after the tourniquet is deflated in patients with head trauma and multiple-extremity trauma is significant in ICP. This increase causes cerebral vasodilatation and an increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF). Ultimately, an increase in ICP occurs [11]. The increased ICP following tourniquet application may alter the patient's condition by causing cerebral shift and potential permanent cerebral injury in orthopedic patients with extremity trauma and head trauma.

Although invasive methods are considered the gold standard in ICP monitoring, they are associated with significant risks such as bleeding and infection [12, 13]. Recently, many studies in the literature have shown that the ultrasonographic measurement of optic-nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) is a noninvasive and rapid technique for monitoring ICP changes [14, 15]. The primary aim of our study was to ascertain whether an early increase in ICP following tourniquet deflation is related to the TT or TP. The secondary aim of our study was to determine a cut-off value of the TT, which is considered an indicator for the increase in ICP in the early period after tourniquet deflation.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out in the Orthopedic Operating Theater after obtaining the approval of the local ethics committee at Karadeniz Technical University's Faculty of Medicine, and the written consent of all the patients included in the study. This study included a total of 60 American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification (ASA) I–II patients, aged 18–65 years, who were scheduled for elective orthopedic intervention with tourniquet application of a lower extremity.

Patients excluded from this study include those with a known history of orbital trauma, ophthalmic diseases, and surgery, conditions that could cause ICP changes (cerebrovascular events, hemorrhage, intracranial space-occupying tumors, etc.), or coagulopathy, as well as those who refused to participate in the study, had any contraindication to general anesthesia or tourniquet use, or had previous adverse reactions to the medications used in the study.

After the preoperative evaluation, the patients were ready for anesthesia after 8 h of fasting and monitoring including electrocardiography (ECG) and heart rate (HR), noninvasive mean arterial pressure (MAP), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) (Spacelabs Medical, USA), bispectral index (BIS) (Aspect Medical Systems XP, USA), and neuromuscular monitoring. After premedication with 0.03 mg/kg midazolam and 3 min of preoxygenation, anesthesia was induced by intravenous administration of 2–3 mg/kg propofol and 1 μg/kg fentanyl, muscle relaxation achieved with 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium, and endotracheal intubation carried out when the BIS value reached < 60. After successful intubation was confirmed, mechanical ventilation was set to achieve a tidal volume of 6–8 mL/kg and a respiratory rate of 10–12 min. Anesthesia was maintained with a BIS of 40–60, a total gas flow rate of 4 L/min using sevoflurane in a concentration of 1–2%, an O2/medical air ratio of 1: 1, a continuous remifentanil infusion of 0.1–0.5 μg/kg/min, and muscle relaxants when needed.

In a total of 60 orthopedic surgical patients, a standard pneumatic tourniquet with an 11-cm-wide cuff was placed so that the distal tip was at a distance 15 cm from the proximal pole of the patella. Computer-assisted randomization was used to assign patients to either group A (inflation with a pneumatic TP of SBP + 100 mm Hg; n = 30) or group B (inflation using the AOP formula; n = 30). A consort flow diagram of the study is shown in Figure 1. Randomization was performed before group assignment using computer-assisted random numbers from www.randomization.com. The allocation list was generated before the study and packed in an envelope. The envelope was opened only when adding a new patient who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram of the study.

In the group inflated according to the AOP formula, the equation “SBP + 10 mm Hg/KTP” was used. The initial SBP was measured, and the corresponding tissue padding coefficient value (KTP) was used [6]. A final TP was achieved by adding 20 mm Hg to the AOP value for safety purposes. The tourniquet was inflated after exsanguination of the limb using an Esmarch bandage or elevation of the limb for 3 min. During the operation, the TP was increased by 10 mm for each 10-mm Hg increase in the SBP during the measurements performed at 10-min intervals. If there was an increase in initial TP and SBP, the value obtained was recorded as maximum TP.

Sonographic measurement of ONSD was performed by 2 anesthesiologists experienced in ultrasonography in accordance with studies reported in the literature [16]. Four measurements were performed separately in the transverse and sagittal planes for both eyes. The average of these 4 measurements was accepted as the final value.

The values were recorded separately at 5 different time points: 15 min before the induction of anesthesia (T0), immediately before deflating the tourniquet (Ti), and 5, 10, and 15 min after the tourniquet was deflated (Td5, Td10, and Td15, respectively). In addition, the general characteristics, operation, and TT, AOP, and initial and maximum TP of each patient were recorded. At the end of the operation, the surgeon, who was blinded to the TP, rated the performance of the tourniquet as excellent (no blood in the surgical field), good (some blood in the surgical field but not interfering with surgery), or bad (the blood in the surgical field obscured the view), and the results were recorded.

Statistical Analyses

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) v23.0 was used for the statistical analysis of the data obtained in the study. Descriptive statistical expressions (frequency, mean, and standard deviation [SD]) were used to assess the data. For the comparison of descriptive values, the χ2 test was used. Normal distribution of values was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnow test, and Student's t test was used for all measures fulfilling the parametric test hypothesis. Repeated-measures ANOVA and the Bonferroni correction were preferred for comparison of the parameters of the 2 groups. The Pearson correlation analysis was used for intermeasure comparisons.

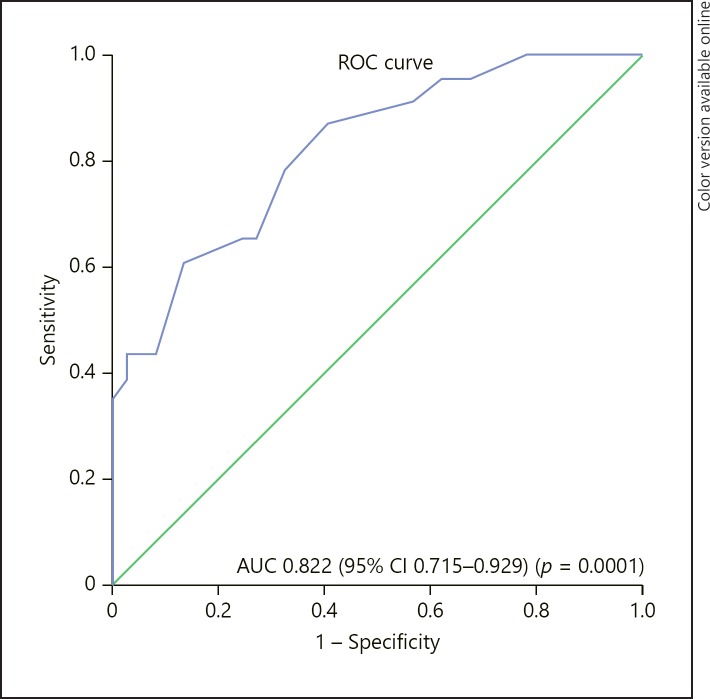

Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curves were generated to determine the ONSD and the cut-off point of EtCO2 measurements in patients with a TT of ≥60 min. ROC analysis was used to determine the cut-off values in diagnostic tests. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) were calculated according to the cut-off. The results were within the 95% confidence interval (CI), with a significance level of p < 0.05.

The following values were used for the calculation of sample size. A total of 60 cases (23 from the test positive group [ONSD ≥5 mm at 5 min after tourniquet deflation] and 37 from the negative group [ONSD < 5 mm at 5 min after tourniquet deflation]) achieved a 53% power to detect a difference of 0.1500 between the area under the ROC curve (AUC) under the null hypothesis (i.e., patients having a short operation time would not have a high ICP) of 0.6500, and an AUC under the alternative hypothesis (i.e., patients having a long operation time would have a high ICP) of 0.8000 using a two-sided z test at a significance level of 0.05000. The data are discrete (rating scale) responses. The AUC is computed between false-positive rates of 0.000 and 1.000. The ratio of the SD of the responses in the negative group to that of the responses in the positive group was 1.000.

Results

The general characteristics and intraoperative data of the patients are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of HR, MAP, SpO2, BIS, and ONSD and EtCO2 values (p > 0.05) (Table 2). The initial and maximum TPs were found to be significantly higher in group A than in group B (p = 0.0001 for all).

Table 1.

General characteristics of patients and intraoperative data

| Parameter | Group A (n = 30) | Group B (n = 30) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 34.3±16.8 | 34.1±13.1 | 0.959a |

| Gender (male/female) | 21/9 | 15/15 | 0.118b |

| BMI | 24.6±3.1 | 24.2±2.8 | 0.556a |

| ASA I/II | 23/7 | 21/9 | 0.771b |

| Operation time, min | 87.0±28.1 | 91.8±31.4 | 0.535a |

| Tourniquet time, min | 75.5±27.6 | 72.3±26.2 | 0.643a |

| Initial SBP, mm Hg | 109.6±6.3 | 108.5±5.3 | 0.495a |

| Initial tourniquet pressure, mm Hg | 221.2±12.4 | 180.5±10.2 | 0.0001a |

| Maximal tourniquet pressure, mm Hg | 230.1±15.9 | 187.7±11.9 | 0.0001a |

| Satisfaction of surgeon (I/II/III) | 27/3/0 | 26/3/1 | 0.601b |

| Surgical procedures | |||

| Arthroscopic knee surgery | 26 (86%) | 25 (83%) | <0.05b |

| Removal of internal fixation | 2 (7%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Achill tendon repair | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | |

Data are expressed as n or mean ± SD. BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Student t test used for comparison

χ2 test used for comparison.

Table 2.

Intraoperative variables

| Parameter | Group A | Group B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | |||

| MAP, mm Hg | 92.3±10.3 | 92.2±10.6 | 0.835 |

| HR, bpm | 74.5±11.7 | 74.3±5.8 | 0.912 |

| Saturation, % | 97.7±1.6 | 97.6±0.9 | 0.903 |

| BIS | 97.7±0.6 | 97.7±0.5 | 0.814 |

| EtCO2, mm Hg | 0 | 0 | - |

| ONSD, mm | 3.7±0.02 | 3.7±0.02 | 0.768 |

| Ti | |||

| MAP, mm Hg | 89.7±9.01 | 90.7±6,6 | 0.626 |

| HR, bpm | 77.5±12.9 | 77.2±11.2 | 0.924 |

| Saturation, % | 98.5±0.9 | 98.6±1.4 | 0.911 |

| BIS | 53.1±3.9 | 52.2±3.2 | 0.311 |

| EtCO2, mm Hg | 32.5±0.9 | 33.1±1.6 | 0.097 |

| ONSD, mm | 3.9±0.02 | 3.7±0.03 | 0.061 |

| Td5 | |||

| MAP, mm Hg | 76.3±10.4 | 78.8±9.7 | 0.332 |

| HR, bpm | 74.7±8.9 | 72.8±6.9 | 0.351 |

| Saturation, % | 98.9±0.9 | 99.1±1.0 | 0.686 |

| BIS | 50.2±4.5 | 49.1±3.4 | 0.293 |

| EtCO2, mm Hg | 41.1±3.1 | 40.4±3.3 | 0.252 |

| ONSD, mm | 4.8±0.05 | 4.7±0.04 | 0.618 |

| Td10 | |||

| MAP, mm Hg | 78.5±11.8 | 78.8±7.5 | 0.906 |

| HR, bpm | 73.2±7.3 | 70.2±6.9 | 0.108 |

| Saturation, % | 99.0±0.7 | 99.2±0.9 | 0.532 |

| BIS | 51.9±3.9 | 51.6±4.3 | 0.781 |

| EtCO2, mm Hg | 35.6±0.9 | 35.2±1.6 | 0.227 |

| ONSD, mm | 4.2±0.03 | 4.1±0.04 | 0.710 |

| Td15 | |||

| MAP, mm Hg | 79.7±10.8 | 80.6±7.7 | 0.702 |

| HR, bpm | 74.6±7.6 | 72.1±7.2 | 0.196 |

| Saturation, % | 98.9±0.8 | 99.2±0.9 | 0.145 |

| BIS | 52.7±3.9 | 51.8±3.6 | 0.362 |

| EtCO2, mm Hg | 34.1±1.7 | 33.6±1.3 | 0.205 |

| ONSD, mm | 3.8±0.02 | 3.8±0.03 | 0.959 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. MAP, mean arterial pressure, HR, heart rate; BIS, bispectral index; EtCO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide; ONSD, optic-nerve sheath diameter. p > 0.05, Student's t test was used for comparison.

There was a significant positive correlation of TT and the ONSD and EtCO2 measurements at 5 min after tourniquet deflation (r = 0.57, p = 0.0001 for ONSD and r = 0.35, p = 0.006 for EtCO2). However, there was no statistically significant correlation between maximum TP and the ONSD and EtCO2 measurements at this time point.

Taking ONSD ≥5 mm as a standard criterion, ROC analysis was performed to determine the TT cut-off value when the ONSD was ≥5 mm. The AUC was 0.82 (95% CI 0.71–0.93) in the ROC created, and the cut-off value for the optimal TT was ≥67.5 min (sensitivity 87%, specificity 59.5%, PPV 57.1%, and NPV 88%; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The ROC curve created for the tourniquet time at 5 min after tourniquet deflation.

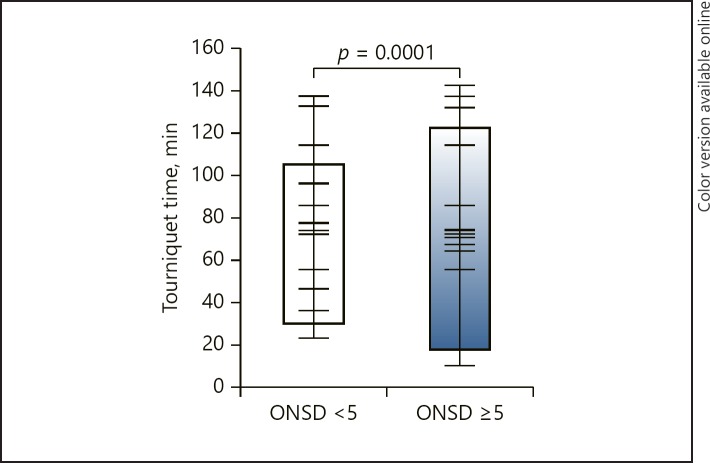

The evaluation of all cases showed a significant difference in TT value between the groups assigned an ONSD value of ≥5 mm and < 5 mm at 5 min after tourniquet deflation (92.7 ± 24.4 and 62.3 ± 21.1, respectively; p = 0.0001; Fig. 3). During the same period, there was no significant difference in maximum TP between the groups (207.86 ± 26.2 and 210.65 ± 24.8, respectively; p = 0.684).

Fig. 3.

Tourniquet time of the groups assigned ONSD values of ≥5 mm and < 5 mm at 5 min after tourniquet deflation.

During the study, there were no complications associated with ultrasonographic ONSD measurements.

Discussion

Our major finding was that the increase in ICP in the early period after tourniquet deflation (after 5 min) was associated with TT but not with TP. We also found that a TT of ≥67.5 min was the cut-off value and is considered the starting point of the increase in ICP after tourniquet deflation.

In orthopedic surgery, tourniquets are often used to reduce hemorrhage in the operative field, improve the visualization of important structures, and expedite the surgical procedure [3]. All pneumatic tourniquets including the new generation of automated devices can lead to a wide range of complications, from minor and self-limiting to life-threatening [1].

Local complications may be due to either direct pressure to, or tissue ischemia in, the underlying tissues, whereas systemic effects are usually associated with TT and ischemia-reperfusion following tourniquet deflation [1]. It has been recommended that TT be limited to 2 h in human studies due to the increase in postoperative complications caused by an extended TT [10]. Investigating the relationship between TT and postoperative complications in arthroplastic knee surgery, Olivecrona et al. [17] found an increase in postoperative complications including wound leakage, local injury due to TP, nerve damage, compartment syndrome, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism with every 10-min increment in TT.

The use of the lowest effective inflation pressure is aimed at minimizing the local complications associated with tourniquet use, such as nerve damage. Orthopedic surgeons often apply a constant inflation pressure (typically, 250 mm Hg for the upper arm and 300 mm Hg for the thigh), or a constant pressure over the systolic arterial pressure (typically, + 100 mm Hg for the upper arm and 100–150 mm Hg for the thigh) [18].

When compared to conventional methods, studies have shown that the TP is reduced by 19–42% according to the AOP calculated just prior to surgery [19]. It has also been determined that these pressures are sufficient to provide a bloodless surgical site [6]. Olivecrona et al. [20] compared tourniquet applications by SBP and AOP and found that an adequate bloodless surgical site could be provided with lower pressure and that the postoperative complication rate was lower in patients who underwent the AOP technique. In our study, we found that TP at the beginning of the operation and maximum TP were significantly lower in group B than in group A, and that there was no difference between the groups in terms of satisfaction with the surgical field. In addition, we found there was no difference between the groups in term of ICP.

The metabolic effects of tourniquet use are usually due to ischemia-reperfusion injury after tourniquet deflation. After 1–2 h of ischemia, a modest increase in arterial plasma potassium, lactate levels, oxygen consumption, and CO2 production, and a transient decrease in arterial pH levels occur following tourniquet deflation [21, 22]. The potent vasodilator effect on the veins of elevated CO2 following tourniquet deflation results in a 50% increase in middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity, which peaks after approximately 2–4 min and returns to baseline value within 8–10 min [23, 24, 25].

There are a limited number of studies in the literature evaluating ICP changes after tourniquet deflation. Eldridge and Williams [26] reported that an increase in EtCO2 level was accompanied by an increase in ICP after tourniquet deflation, according to invasive ICP monitoring inserted in the preoperative period in a patient with traumatic brain injury who had a tourniquet applied during orthopedic surgery. With tourniquet deflation, the concomitant increase in CO2 level can cause a dangerous increase in ICP. This situation may have serious consequences in patients with traumatic brain injury or an intracranial space-occupying lesion.

In ICP monitoring, the intraventricular catheter technique is accepted as the gold standard despite being invasive. Therefore, in our study, we determined ICP changes after tourniquet deflation using serial ultrasonographic ONSD measurement, which is a noninvasive, safe, and rapid technique for showing ICP changes. Based on results reported in other studies, the optimal cut-off value of ONSD for predicting intracranial hypertension ranges from 5.0 to 5.9 mm [27, 28, 29]. We therefore chose an ONSD cut-off value of 5 mm in our study.

We determined that ICP increase due to the increase of CO2 associated with ischemia-reperfusion, especially in the early period after tourniquet deflation, was not affected by TP but was correlated with TT. A review of the literature did not reveal any studies on cut-off point and onset of ICP increase (> 5 mm) or on TT and TP. In our study, the ONSD value at the point when the ICP increase started 5 min after tourniquet deflation was found to be correlated with TT but not with TP. It should be taken into consideration that the ICP increase may already start in the early period following tourniquet deflation after a TT exceeding 67.5 min in patients with an intracranial space-occupying lesion or traumatic brain injury who undergo tourniquet application of a lower extremity.

The most important limitation of our study was the use of noninvasive, serial ultrasonographic ONSD measurements because of the potential for ethical problems related to surgical intervention, even though invasive methods that directly measure ICP values are the gold standard. Additionally, the sample size should be larger in order to obtain more precise results for determining a cut-off value for the TT, which is the limit of the ICP increase. The third limitation of the study was its low power.

Conclusion

(1) Does TT or TP cause ICP increase after pneumatic tourniquet deflation in lower-extremity surgery? (2) What is a safe cut-off value for TT or TP? In this study, we found that the increase in ICP in the early period after tourniquet deflation was associated with TT but not with TP. We also believe that clinicians should be cautious about the start of ICP increase after tourniquet deflation when the TT exceeds 67.5 min.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Suleyman Guven from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon, Turkey, for her help with the statistics and her support for this study.

References

- 1.Kam PC, Kavanagh R, Yoong FF. The arterial tourniquet: pathophysiological consequences and anaesthetic implications. Anaesthesia. 2001 Jun;56((6)):534–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith TO, Hing CB. Is a tourniquet beneficial in total knee replacement surgery? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Knee. 2010 Mar;17((2)):141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estebe JP, Davies JM, Richebe P. The pneumatic tourniquet: mechanical, ischaemia-reperfusion and systemic effects. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011 Jun;28((6)):404–11. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328346d5a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noordin S, McEwen JA, Kragh JF, Jr, Eisen A, Masri BA. Surgical tourniquets in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Dec;91((12)):2958–67. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparling RJ, Murray AW, Choksey M. Raised intracranial pressure associated with hypercarbia after tourniquet release. Br J Neurosurg. 1993;7((1)):75–7. doi: 10.3109/02688699308995059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuncalı B, Boya H, Kayhan Z, Araç Ş, Çamurdan MA. Clinical utilization of arterial occlusion pressure estimation method in lower limb surgery: effectiveness of tourniquet pressures. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2016;50((2)):171–7. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2015.15.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuncali B, Karci A, Tuncali BE, Mavioglu O, Ozkan M, Bacakoglu AK, et al. A new method for estimating arterial occlusion pressure in optimizing pneumatic tourniquet inflation pressure. Anesth Analg. 2006 Jun;102((6)):1752–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000209018.00998.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nitz AJ, Matulionis DH. Ultrastructural changes in rat peripheral nerve following pneumatic tourniquet compression. J Neurosurg. 1982 Nov;57((5)):660–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.5.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedowitz RA, Gershuni DH, Schmidt AH, Fridén J, Rydevik BL, Hargens AR. Muscle injury induced beneath and distal to a pneumatic tourniquet: a quantitative animal study of effects of tourniquet pressure and duration. J Hand Surg Am. 1991 Jul;16((4)):610–21. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(91)90183-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgibbons PG, Digiovanni C, Hares S, Akelman E. Safe tourniquet use: a review of the evidence. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012 May;20((5)):310–9. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-05-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirst RP, Slee TA, Lam AM. Changes in cerebral blood flow velocity after release of intraoperative tourniquets in humans: a transcranial Doppler study. Anesth Analg. 1990 Nov;71((5)):503–10. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Brain Trauma Foundation The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Recommendations for intracranial pressure monitoring technology. J Neurotrauma. 2000 Jun-Jul;17((6-7)):497–506. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilberger JE., Jr Outcomes analysis: intracranial pressure monitoring. Clin Neurosurg. 1997;44:439–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajajee V, Vanaman M, Fletcher JJ, Jacobs TL. Optic nerve ultrasound for the detection of raised intracranial pressure. Neurocrit Care. 2011 Dec;15((3)):506–15. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Li Z, Zhang X, Zhao L, Jia J, Sun F, et al. Assessment of intracranial pressure with ultrasonographic retrobulbar optic nerve sheath diameter measurement. BMC Neurol. 2017 Sep;17((1)):188. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0964-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geeraerts T, Merceron S, Benhamou D, Vigué B, Duranteau J. Non-invasive assessment of intracranial pressure using ocular sonography in neurocritical care patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008 Nov;34((11)):2062–7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olivecrona C, Lapidus LJ, Benson L, Blomfeldt R. Tourniquet time affects postoperative complications after knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013 May;37((5)):827–32. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1826-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deloughry JL, Griffiths R, Arterial tourniquets Continuing Education in Anesthesia. Crit Care Pain (Indian Edition) 2009;2:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Younger AS, McEwen JA, Inkpen K. Wide contoured thigh cuffs and automated limb occlusion measurement allow lower tourniquet pressures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Nov;428:286–93. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000142625.82654.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivecrona C, Blomfeldt R, Ponzer S, Stanford BR, Nilsson BY. Tourniquet cuff pressure and nerve injury in knee arthroplasty in a bloodless field: a neurophysiological study. Acta Orthop. 2013 Apr;84((2)):159–64. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.782525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modig J, Kolstad K, Wigren A. Systemic reactions to tourniquet ischaemia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1978;22((6)):609–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1978.tb01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoka S, Yoshitake J, Arakawa S, Ohta K, Yamaoka A, Goto T. VO2 and VCO2 following tourniquet deflation. Anaesthesia. 1992 Jan;47((1)):65–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadoi Y, Ide M, Saito S, Shiga T, Ishizaki K, Goto F. Hyperventilation after tourniquet deflation prevents an increase in cerebral blood flow velocity. Can J Anaesth. 1999 Mar;46((3)):259–64. doi: 10.1007/BF03012606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam AM, Slee T, Hirst R, Cooper JO, Pavlin EG, Sundling N. Cerebral blood flow velocity following tourniquet release in humans. Can J Anaesth. 1990 May;37((4 Pt 2)):S29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doblar DD, Frenette L, Poplawski S, Gelman S, Boyd G, Ranjan D, et al. Middle cerebral artery transcranial Doppler velocity monitoring during orthotopic liver transplantation: changes at reperfusion—a report of six cases. J Clin Anesth. 1993 Nov-Dec;5((6)):479–85. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(93)90065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eldridge PR, Williams S. Effect of limb tourniquet on cerebral perfusion pressure in a head-injured patient. Anaesthesia. 1989 Dec;44((12)):973–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1989.tb09199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimberly HH, Shah S, Marill K, Noble V. Correlation of optic nerve sheath diameter with direct measurement of intracranial pressure. Acad Emerg Med. 2008 Feb;15((2)):201–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geeraerts T, Launey Y, Martin L, Pottecher J, Vigué B, Duranteau J, et al. Ultrasonography of the optic nerve sheath may be useful for detecting raised intracranial pressure after severe brain injury. Intensive Care Med. 2007 Oct;33((10)):1704–11. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0797-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moretti R, Pizzi B. Optic nerve ultrasound for detection of intracranial hypertension in intracranial hemorrhage patients: confirmation of previous findings in a different patient population. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009 Jan;21((1)):16–20. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e318185996a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]