Abstract

Since the approval in 2017 and the outstanding success of Kymriah® and Yescarta®, the number of clinical trials investigating the safety and efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor-modified autologous T cells has been constantly rising. Currently, more than 200 clinical trials are listed on clinicaltrial.gov. In contrast to CAR-T cells, natural killer (NK) cells can be used from allogeneic donors as an “off the shelf product” and provide alternative candidates for cancer retargeting. This review summarises preclinical results of CAR-engineered NK cells using both primary human NK cells and the cell line NK-92, and provides an overview about the first clinical CAR-NK cell studies targeting haematological malignancies and solid tumours, respectively.

Keywords: Chimeric antigen receptor, Natural killer cells, NK-92, CAR-NK cell, Solid tumour, Haematological malignancies

Introduction

As an essential part of the innate immune system, natural killer (NK) cells play a pivotal role as the body's first-line defence against virally infected and malignant cells. During the last 15 years, several clinical trials with do nor NK cells have shown their safety and feasibility [1, 2], but limitations appeared due to tumour immune escape mechanisms (TIEM). To overcome TIEMs, NK cells can be modified by retroviral or lentiviral vector transduction to express antibody-derived single-chain variable fragments (scFv) for cancer retargeting. The backbone chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) design contains an antigen recognition domain derived from an scFv antibody connected to a hinge and transmembrane domain mediating an anchorage to the cell membrane and, in the case of first-generation CARs, a cluster of differentiation (CD) 3 zeta (ζ) chain-derived signalling domain responsible for effector cell activities. Additionally, second- and third-generation CARs include either one or two costimulatory domains, respectively [3]. In comparison to the outstanding clinical results with CAR-engineered T cells, CAR-modified NK cells can reveal some advantages by additional cancer-killing mechanisms, especially antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). In terms of safety conditions, unwanted adverse effects are avoided by short-term persistence and the lack of antigen clonality of CAR-modified NK cells [4, 5, 6]. CAR-redirected NK cells appear to have a beneficial impact and improved effects in immunosurveillance. Similar to CAR-T cells, they were shown to mediate potent anti-tumour activity against CD19-positive cells in vitro and in a Raji lymphoma mouse model [7]. Currently, this leads to first immunotherapeutic approaches to cure both lymphomas of B cell origin and acute lymphoid leukaemia (ALL). This includes human NK cells of different origins, such as the NK cell line NK-92, primary cord blood (CB)-derived as well as peripheral blood (PB) NK cells, which have recently entered clinical implementation testing the effectiveness in different phase I/II studies (Table 1) [4, 8, 9, 10]. Other than primary NK cells collected from CB or PB, the transformed cell line NK-92 originated from undifferentiated NK-cell precursors [11, 12, 13]. The malignant origin of NK-92 constituted an obstacle in the development of NK-92-based cell therapeutics which was conquered by irradiation [14, reviewed in 6]. The infusion of irradiated unmodified NK-92 cells was shown to be safe in patients suffering from “advanced, treatment-resistant malignancies” [15]. Furthermore, several groups impressively showed in vitro and in vivo that the cytotoxic activity of CAR-engineered NK-92 cells was preserved despite a proliferation-limiting irradiation [reviewed in 6]. Other than NK-92 cells, which can be expanded in cell culture, limiting amounts of primary NK cells challenged the development of NK cell-based therapeutic approaches. To solve this problem, a dose escalation phase I/II study with umbilical CB-derived CAR-engineered NK cells was authorised for patients with relapsed and refractory B-lymphoid malignancies (NCT03056339; Table 1) [4, 9]. In addition, the first clinical CAR-NK cell trials targeting antigens such as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), CD33, Mucin-1 (MUC1), CD7, and NK group 2, member D (NKG2D) ligands have been initiated (Table 1). In this respect, we discuss both the advantages and probable disadvantages of primary human CAR-NK cells and CAR-modified NK-92 as a meaningful alternative or complementary strategy for an immunotherapeutic approach towards CAR-modified T cells.

Table 1.

CAR-NK cells in clinical trials

| Clinical trial identifier | Target | Condition/disease | Origin of NK cells | Phase | Status | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03579927 | CD19 | Lymphoma and leukaemia | Umbilical cord blood | I/II | Not yet recruiting | Houston, TX, USA |

| NCT03056339 | CD19 | Lymphoma and leukaemia (relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancy) | Umbilical cord blood | I/II | Recruiting | Houston, TX, USA |

| NCT02892695 | CD19 | Lymphoma and leukaemia | NK-92 | I/II | Recruiting | Suzhou, Jiangsu, China |

| NCT01974479 | CD19 | ALL | Haploidentical donor NK cells | I | Suspended | Singapore |

| NCT00995137 | CD19 | ALL | Expanded donor NK cells | I | Completed | Memphis, TN, USA |

| NCT02742727 | CD7 | Lymphoma and leukaemia | NK-92 | I/II | Unknown | Suzhou, Jiangsu, China |

| NCT02944162 | CD33 | Acute myeloid leukaemia | NK-92 | I/II | Unknown | Suzhou, Jiangsu, China |

| NCT02839954 | MUC1 | Solid tumours | Not specified | I/II | Unknown | Suzhou, Jiangsu, China |

| NCT03383978 | HER2 | Glioblastoma | NK-92 | I | Recruiting | Frankfurt, Germany |

| NCT03415100 | NKG2D ligands | Solid tumours | Autologous or allogeneic NK cells | I | Recruiting | Guangzhou, Guangdong, China |

| NCT03656705 | - | Non-small cell lung cancer | Chimeric costimulatory converting receptor-modified NK-92 cells | I | Recruiting | Xinxiang, Henan, China |

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; NK, natural killer; MUC1, Mucin-1; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; NKG2D, NK group 2, member D; ALL, acute lymphoid leukaemia.

CAR-Modified NK Cells against Leukaemia and Lymphoma

In preclinical and clinical trials, CAR-engineered NK cells targeting several different antigens, such as CD19, CD20, CD33, CD138, CD319 (also known as signalling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 7, SLAMF7), CD3, CD5, and CD123, were investigated for their anti-tumour activity in vitro and in vivo [reviewed in 16]. Due to the tremendous therapeutic efficiency of CD19-directed CAR-modified T cells and their clinical use, data regarding the side effects and toxicity of CAR-T cell therapy are routinely obtained. Since T cell infusion as a therapeutic approach can lead to a broad variety of severe side effects (cytokine release syndrome, febrile neutropenia, hypotension, decreased blood cell counts, neurological events, infections, tumour lysis syndrome, etc. [17]), other immune cell populations such as NK cells were discussed for CD19-directed CAR therapy. In 2004, Tonn and colleagues [18] presented data of a genetically modified NK cell line, NK-92, which harboured a first-generation CAR directed against CD19. Furthermore, in 2016, the group published in vitro data showing increased specific cytotoxic activity of CD19-directed CAR-NK-92 cells compared to unmodified NK-92 against cells expressing the target antigen [19]. The necessity for NK cell stimulation and activation by cytokines to improve their proliferation and persistence led to the development of optimised CAR constructs. CB-derived NK cells transduced with a construct harbouring coding sequences for a CD19-directed scFv, interleukin (IL)-15 (to enhance the cells' activity), and a suicide gene (inducible caspase-9; iC9) not only revealed anti-tumour activity but also showed extended persistence of the CAR-modified NK cells resulting in prolonged survival of mice using an aggressive Raji lymphoma mouse model [7]. To control their cytotoxic activity, iC9-bearing CAR-modified CB-derived NK cells could be efficiently eliminated upon rimiducid addition in vitro and in vivo [7].

Several different NK cell-based therapeutics targeting CD19 are in clinical trials by now, one of which is the aforementioned CB-NK cell therapeutic (iC9/CAR.19/IL-15-transduced CB-NK cells) adopted for use in humans and designed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center of the University of Texas (NCT03056339; Table 1). Additionally, a phase I/II clinical trial of a third-generation CAR (CD19-4-1BB-CD28-ζ)-transduced NK-92 cell line was enrolled in 2016 and is still ongoing (NCT02892695; https://clinicaltrials.gov; Table 1). In the manufacturing of CAR-T cells, lentiviral transduction is the method of choice since persistence is prolonged when memory T cell subsets, i.e., resting cells, are transduced [20, clinical use of lentiviral vectors summarised in 21]. In contrast, CAR-NK cell transduction rates are elevated due to optimised cultivation procedures opening an opportunity to use retroviral systems [22], whose good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant production is easier and cheaper [23]. Alpha-retroviral vectors hold attractive features for the manufacture of gene therapeutics regarding their integration pattern into the host genome. In 2004, a study was published where DNA integration of different retroviruses was compared, revealing that the avian sarcoma-leukosis virus (alpha-retrovirus) showed “the weakest bias toward integration in active genes and no favouring of integration near transcription start sites” [24]. A study from 2016 validated retroviral vector systems for the manufacture and modification of NK cells in order to obtain efficient transduction rates [22]. When alpha-retro-, gamma-retro-, and lentiviral vectors were compared, the designed alpha-retroviral vectors showed significantly increased transduction rates of over 90% when an NK cell line was used and up to 60% when primary NK cells were genetically modified [22]. Moreover, the expression profile and degranulation activity of alpha-retroviral-modified NK cells were unaffected, confirming the eligibility of this transduction tool in the manufacture of CAR-modified NK cells [22]. The authors argued that many factors influence transduction efficacy (e.g., transduction method and codon optimisation of the construct) and speculated that primary NK cells may exert specific responses against viral particles of certain pseudotypes [22]. Moreover, an advanced alpha-retroviral system was used in these works, which might tip the balance in favour of this approach [22, 25, 26]. However, it would be too early to speculate that different retroviral properties and elicited anti-viral responses correlate with the retrovirus-specific differences in transduction efficiencies, with RD114/TR pseudotyped alpha-retroviral particles, and with improved gene transfer in NK cells.

Besides the promising preclinical data obtained from CD19-directed CAR-NK cells, the cytotoxic effect of CD20-targeting CAR-NK-92 cells against primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells was evaluated in vitro and in a Daudi mouse model [27]. When compared to rituximab- and ofatumumab-induced ADCC, anti-CD20 CAR-NK-92 cells showed increased anti-tumour activity against primary CLL cells in vitro [27]. Although CD20-directed NK cells – both stably transduced NK-92 and mRNA-transfected PB-NK cells – showed in vivo anti-tumour activity in localised tumour xenograft mouse models [27, 28], their transfer into clinical trials has not been successful yet. More recently, combination therapy of anti-CD20-CAR mRNA electroporated PB-NK cells and romidepsin was shown to induce synergistic anti-tumour effects both in vitro and in vivo using a localised Raji lymphoma model [28].

For the treatment of leukaemia and lymphoma, CD7 is under investigation regarding its potential for CAR-based therapeutic approaches (Table 1). Due to a stable expression of the antigen on leukaemic T cells [29], CAR-T cells were designed against CD7 for the treatment of T-ALL and T-cell lymphomas [30]. However, since CD7 is expressed by all T and NK cells including CAR-modified T cells, T cell expansion was precluded during manufacturing of CD7-directed CAR-T cells due to “substantial fratricide of T cells” [31]. To overcome the limitations of this therapeutic approach, several groups of scientists tested different methodical concepts. The first strategy was using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and CRISPR-associated (CRISPR/Cas) 9 in order to knock out CD7 in those T cells which were used for subsequent CAR modification. The absence of CD7 ensured fratricide prevention and CD7-directed CAR-T cells showed cytotoxic activity against target antigen-expressing cells [30, 31]. In another approach, a protein expression blocker was used to downregulate CD7 expression by transducing CD7-specific endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi retention peptide-coding plasmids in T cells prior to transient CD7-directed CAR-modification [32]. The phenotype and cytokine profile of CD7-downregulated T cells were comparable to control-transduced T cells. Additionally, CAR-carrying and CD7-downregulated T cells showed potent cytotoxic activity against leukaemic cells in vitro and in xenograft T-ALL mouse models [32]. Eventually, a clinical trial was enrolled in 2016 investigating the safety and toxicity of CD7-directed CAR-NK cells (Table 1). Only the outcome of the clinical trial will give hints as to whether an NK cell-based CD7-directed cellular therapeutic can overcome the aforementioned hindrances.

Another potential target for T-cell lymphoma and T-ALL therapy is CD5. Approaches directed against this antigen face the same difficulties as CD7-directed approaches since CD5 is also a pan T-cell marker. Two studies showed that NK-92 expressing CD5-directed CARs were efficient in vitro against CD5-positive cell lines and primary tumour cells, and developed anti-tumour activity in vivo [33, 34]. Additionally, the use of anti-CD3 CAR-equipped NK-92 against primary peripheral T-cell lymphoma cells and T-cell leukaemia cell lines was investigated showing cytotoxic activity in vitro and against Jurkat cells in a xenogeneic mouse model [35].

Therapeutic NK Cells in the Treatment of AML

In 2017, gemtuzumab ozogamicin was re-approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia [36]. Studies showing that CD33-binding antibodies were efficiently internalised upon antigen binding [37, 38] paved the way for therapeutic targeting of CD33. The humanised CD33-directed IgG4 antibody gemtuzumab ozogamicin is conjugated to a bacterial toxin, which binds to DNA, thereby mediating DNA damage in targeted cells [39]. CD33 is expressed on both healthy and malignant myeloid cells [39 and references therein]. For the targeting of CD33, several different therapeutic approaches are under current investigation, including antibody-drug conjugates and bispecific antibodies [reviewed in 40]. Additionally, CD33-directed CAR-modified T cells carrying an scFv derived from gemtuzumab ozogamicin were shown to mediate potent in vitro and in vivo anti-tumour activity [41]. Since these CAR-T cells were produced by electroporation of in vitro transcribed mRNA, cytotoxic anti-tumour effects were induced only transiently to “[…] minimise the risk of long-term hematopoietic toxicity” [41]. In another study, the persistence and safety of CD33-directed CAR-T cells were compared between constructs harbouring different costimulatory domains within the CAR [42]. Regarding their efficacy, the examined anti-CD33-CAR-T cells were shown to induce similar anti-tumour activity in vitro as well as in a xenograft tumour mouse model [42]. Due to their shorter life span in comparison to T cells, CD33-directed CAR-modified NK-92 cells (second-generation CAR, CD28-CD3ζ) were designed and exerted potent cytotoxic activity against target cells in chromium-51-release assays [43]. Efficacy and safety data of allogeneic or haploidentical NK cell transplantations including NK-92 have been obtained from several clinical trials [reviewed in 44, 45]. However, a clinical phase I/II trial was enrolled in 2016 testing the safety and toxicity of CD33-directed NK-92 cell infusions (CD33-CD3ζ-CD28-4-1BB) in patients whose leukaemic disease relapsed (after stem cell transplantation and chemotherapy) or appeared refractory to treatment (NCT02944162; https://clinicaltrials.gov; Table 1). The outcome of this and other clinical trials of CAR-modified NK cells can shed light on toxicity, safety, and efficacy aspects of NK cell-based therapeutics.

Besides the therapeutic targeting of CD33, CD123 was investigated regarding its feasibility as an immuno-oncological target in the treatment of AML. Other than CD33, which is expressed on malignant cells and healthy haematopoietic stem cells [46], CD123 expression is increased in malignant haematological cells but rather low on haematopoietic stem cells [47]. Despite the favourable expression profile of CD123, T cells expressing CD123-guided CARs were shown to induce severe haematological off-target toxicities in AML mouse models [48, 49]. For further studies, strategies to either eradicate CAR-modified T cells from the periphery or to transiently express CARs are urgently needed. In the case of CD123, a CAR-NK cell-based concept would be a more practical approach. The GMP-compliant clinical-grade manufacturing of expanded and activated NK cells expressing CD123-directed CARs was proven feasible and the produced CAR-modified effector cells showed in vitro activity against both an AML cell line and patient samples [50].

Other CARs targeting AML, yet focussing on CAR-T therapy, are directed against folate receptor-β (FRβ), C-type lectin-like molecule-1 (CLL1, also known as CLEC12A), fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3, CD135), B7H6, NKG2D, and Lewis Y antigen (LeY), and some have already been transferred to clinical trials [reviewed in 44].

CAR-NK Cells in Multiple Myeloma

As the progression of multiple myeloma (MM) is connected to NK cell impairment by tumour escape mechanisms [51, 52, 53, 54] and the biomolecular action of anti-myeloma agents involves NK-cell responses [also reviewed in 55], enhancing NK cell-mediated anti-tumour activity is an apparent strategy in cellular MM therapy. Although some data indicate that many primary MM tumours are insensitive to NK-92-mediated killing [54], the NK-92 cell line was investigated in a phase I clinical trial showing “some evidence of efficacy” [56]. Upgrading this approach, two CARs against CD319 (also known as CS1 or SLAMF7) and CD138 were inserted into NK-92 and NK-92MI (derived from NK-92, IL-2-independent), respectively, and were successfully tested in vitro and in vivo against cell lines and primary MM cancer cells [57, 58]. CD138 is the main diagnostic MM marker [reviewed in 59]. The safety of SLAMF7 as an MM target is well supported since it is targeted by a therapeutic antibody (elotuzumab, previously known as HuLuc63), which mediates NK-cell-dependent ADCC against cells expressing the target antigen [60, 61], as well as by CAR-T and CAR-NK cells [57, 62]. Besides CD138 and SLAMF7, preclinical studies with CAR-T cells for the treatment of MM concentrated on antigens such as CD38, CD44v6, B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA, CD269), and κ-light chains [reviewed in 55], thereby holding potential for further CAR-NK cell candidates. Until now, CAR-equipped NK cells targeting MM have not entered clinical trials.

Recently, SLAMF7-directed CAR-NK cells were combined with the therapeutic CD38-directed antibody daratumumab for the treatment of relapsed MM [63]. The authors hypothesised synergistic effects on tumour eradication only in the presence of both SLAMF7-directed CD38-negative CAR-NK cells and daratumumab, indicating the combination of conventional with novel treatment options as an appealing approach [63].

Effectiveness of CAR-Engineered Primary NK Cells against Solid Tumours

Primary human CAR-NK cells have a high potential for use as both autologous or allogeneic cytotoxic CAR effector cells in immunotherapeutic approaches [8]. However, compared to vulnerable/sensitive lymphomas with stable overexpression of B-cell antigens, most antigens used for solid tumour therapy show alternating surface expression levels with heterogeneity even within the tumour or between primary and metastatic lesions [64, reviewed in 65, 66, 67]. In preclinical studies, it could be shown that disialoganglioside- (GD2; expressed on tumours of neuroectodermal origin [68]) positive Ewing sarcoma (ES) cells could be used for the engineering of a second- and third-generation anti-GD2-CAR. This led to an improvement of the NK cell-driven cytotoxicity against several cancer cell lines in vitro and resulted in effective counteraction against ES tumour resistance [69, 70]. However, adoptive transfer of anti-GD2-CAR-NK cells in GD2-expressing ES xenograft models could not confirm previous in vitro experiments [70]. Furthermore, the diminished anti-tumour response of those CAR-modified NK cells was connected to increased expression levels of immunosuppressive human leukocyte antigen G (HLA-G) on ES cells, thereby mediating tumour immune escape [71]. The authors concluded that HLA-G represents a potential checkpoint, which would have to be inhibited before initiating therapies based on CAR-NK cells [70].

Another innovative approach to restore specific anti-tumour reactivity is the genetic manipulation of primary NK cells by generation of DNAX-activation protein (DAP)-12 based CARs, also referred to as anti-prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA)-DAP12, for retargeting primary NK cells towards PSCA-positive bladder tumours [72]. PSCA shows low-to-moderate expression levels on normal prostate tissue, but is highly expressed on primary prostate tumours and prostate cancer metastases [73, 74]. Unlike several other CAR-specialised research groups working with common activation domains (e.g., CD3ζ-signalling domain), this preclinical study was focused on a novel strategy for the stimulation of signal transduction pathways to trigger NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity by using DAP12 as a cell type-specific intracellular signalling domain [72, 75]. The key signal transduction receptor DAP12 is usually found in NK cells and induces surface expression of the associated activating receptor NKG2C (NK group 2, member C) [76] and the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp44 [77, 78]. PSCA-DAP12-engineered NK cells showed retargeted killing activities after antigen binding via intracellular ζ-chain-associated protein kinase 70 phosphorylation and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) secretion against PSCA-positive tumour cells, which was markedly improved by killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR)-HLA mismatch [72]. These data underline the hypothesis that NK cell-specific activation domains (e.g., DAP12) are essential for a powerful, redirected CAR-NK cell cytotoxicity and, thus, for an improved immunotherapy against solid tumours. Besides NKG2C activation, which is responsible for immunosurveillance of cytomegalovirus infections in humans and mice [79, 80, 81], it is also advisable to recruit additional activating receptors such as NKG2D. NKG2D recognises multiple ligands, such as major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related peptides A/B (MICA, MICB), and several UL-16-binding proteins (ULBP), which are preferentially expressed after cellular stress on malignant and transformed tumour cells [82, 83], thus resulting in an NKG2D-mediated anti-tumour activity [84, 85, 86, 87]. The NKG2D target-associated antigen (TAA)-crosslink leads to activating signals via phosphorylation of NK-typical DAP10, inducing NK cell-dependent cytotoxicity against tumour cells [88, 89]. As NKG2D – already expressed by NK cells – recognises tumour antigens of the NKG2D ligand families induced after DNA damage, for example, it is attractive to fuse this natural cancer-targeting molecule to signal enhancers. Those activation cascades have been used successfully in a preclinical study to generate a retroviral construct encoding a chimeric receptor containing NKG2D, DAP10, and CD3ζ [90]. Activated NK cells were transduced with the NKG2D-DAP10-CD3ζ expression vector and tested for their anti-tumour activity in vitro and in vivo [90]. The cells showed increased NKG2D surface expression, enhanced tumour necrosis factor-α and IFN-γ release, and improved, redirected anti-tumour response against several tumour entities (prostate, colon, gastric, lung squamous cell, hepatocellular and breast carcinomas), and, in particular, to osteosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and neuroblastoma cells without mediating adverse effects against non-malignant cells, such as mesenchymal cells [90]. Since NKG2D-DAP10-CD3ζ-modified NK cells showed improved anti-tumour activity and off-target safety in vitro, they may be an interesting format for further approaches in the treatment of cancer and as a therapeutic option for infectious diseases [90]. Regarding their nomenclature, NKG2D-CARs are not “classical” CARs since NKG2D is not an scFv, but are referred to as “CARs” in the literature [90].

Recently, a novel, single-centre pilot study by mRNA-electroporated CAR-NK cells with transiently increased specificity and cytotoxicity against NKG2D-ligand was initiated in cancer patients diagnosed with metastatic NKG2D ligand-positive solid tumours. The goal is to evaluate and assess the safety and feasibility aspects of those autologous or allogeneic CAR-transfected NK cells (NCT03415100; https://clinicaltrials.gov; Table 1).

Compared to monotherapies with CAR-NK cells, combinations of second-generation designed epidermal growth factor receptor-CAR-NK cells and oncolytic Herpes simplex virus led to higher killing rates against breast cancer cell lines and enhanced inhibition of the tumour progression in a breast cancer mouse model [91]. This seems to be an extensible application for CAR-NK cells in combination with oncolytic viruses to effectively eliminate resistant solid tumours [91]. Moreover, it is urgent to include predominantly overexpressed TAAs from resistant cancer identities for the generation of target-oriented CAR constructs to induce redirected NK cell responses. CAR-driven NK cell cytotoxicity depends on stable and moderate surface expression levels of the retargeted antigen. If the antigen expression is too low, tumour cells can escape the monitoring of CAR-engineered effector cells. However, the enhanced optimisation of CAR-TAA-mediated molecule affinity to recognise and crosslink very low antigen surface levels on target cells would lead to undesirable side effects against healthy tissue and non-transformed cells, resulting in on-target/off-tumour interactions. Therefore, in case of resistant tumour cells, a solution to known limitations could be the development of dual-specific CAR-NK cells for recognition and crosslinking of both corresponding TAAs in order to minimise the observed adverse side effects against normal tissue and healthy cells.

CAR-Expressing NK-92 Cells for Retargeting of Solid Tumours

In the past and present, it has often been shown that the NK-92 cell line can be effectively transduced with several different CARs against several malignancies for testing in preclinical approaches and currently in first clinical studies. CAR-NK-92 cells were quite successful in overcoming the tumour barrier and retargeted anti-tumour cytotoxicity against several resistant solid tumours, including epithelial cancers by targeting of human epidermal growth factor receptors (HER1 [ErbB1], HER2 [ErbB2]), neuroectodermal tumours by GD2, brain tumours by HER1 and HER2, and ovarian carcinomas also by HER2 [4, 6, 92, 93]. However, there are some limitations to using this cell line. Since the transformed NK-92 cell line originated from undifferentiated NK-cell precursors [11, 12, 13], these NK cells lack ADCC-inducing CD16 receptors, which is also the case in other NK cell lines [94]. Consequently, these effector cells are unable to recognise tumour-targeted antigens by ADCC mechanisms. To overcome these cytotoxic limitations, NK-92 cells were genetically manipulated to express the high-affinity V158 variant of the Fc-gamma receptor (FcγRIIIa/CD16a, termed haNKTM) and to produce endogenous, intracellularly retained IL-2 [95, 96]. In an ongoing phase I trial it will be evaluated whether infused haNKTM cells are safe and potent in the treatment of patients with histologically confirmed, non-resectable, and locally advanced or metastatic solid tumours (NCT03027128; https://clinicaltrials.gov; Table 1).

Another unfavourable aspect is the absence of some KIRs, with the exception of KIR2DL4 (CD158d) on the surface of NK-92, which may contribute to a possible stimulation of graft-versus-host disease [12, 97, 98, 99]. Thus, it should be noted that activated CAR-modified NK-92 cells must be irradiated with at least 10 Gy before infusion in tumour patients, resulting in a lower cell persistence and a loss of effector-mediated anti-tumour functions [99]. Despite these disadvantages, preclinical results were described for CAR-expressing NK-92 cells targeting a wide range of tumour antigens [100, 101]. To date, only a few clinical trials using CAR-modified NK cells against haematological malignancies and especially against solid tumours have been initiated (Table 1). Recently, a phase I/II trial aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of CAR-NK cells in patients with overexpressed MUC1-positive relapsed or refractory solid tumours, especially carcinomas (hepatocellular/pancreatic/breast/colorectal/gastric), non-small cell lung cancer, and glioblastoma (NCT02839954; https://clinicaltrials.gov; Table 1) [reviewed in 92].

Conclusion and Outlook

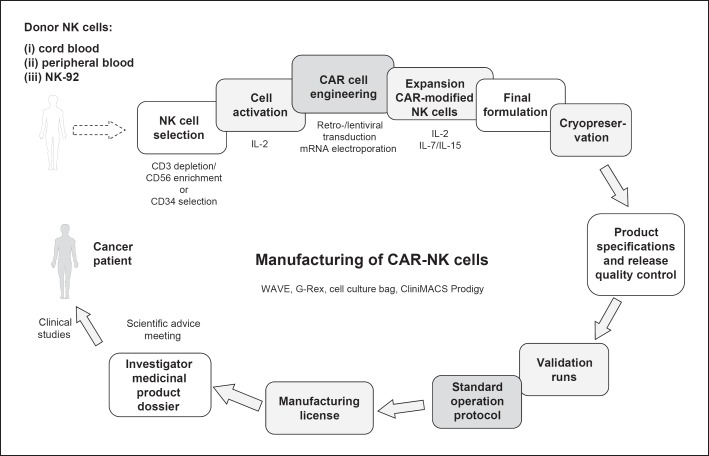

Both CB- and PB-derived primary human CAR-NK cells as well as CAR-NK-92 cells are complex medicinal products combining important features: cell products that are genetically modified and applicable as cellular immunotherapy. The entire manufacturing process following GMP requires between 10 days and several weeks using bags or more harmonised automation platforms like the CliniMACS Prodigy® (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH). These different strategies allow NK cell activation, transduction, amplification, and final harvesting of CAR-NK cells with high transduction frequencies and mostly efficient cell numbers (Fig. 1). In contrast to CAR-T cells, CAR-NK cells have the advantage of “off-the-shelf” manufacturing, but still face several challenges. This includes the improvement in cell numbers, making the intracellular signalling more specific for NK cells, as reviewed by Oberschmidt et al. [9], and finally, finding the best source of NK cells. Also, the question of whether long-living immature or short-living mature CAR-NK cells are more suitable as therapeutic products has not been answered yet.

Fig. 1.

GMP-compliant manufacturing of CAR-T cells.

Other concepts are aiming to combine the advantages of T and NK cells, leading to the development of the so-called T-cell receptor (TCR)-CARs, which, like NKG2D-CARs, do not contain scFv antibody domains [102]. The stable expression of a functional peptide-specific TCR-CAR in NK-92 cells was proven feasible [102]. Moreover, TCR-CAR NK-92 were highly cytotoxic against formerly almost NK-insensitive cancer cell lines, whereas the recognition of unloaded major histocompatibility complex resulted in killing only at high effector:target ratios [102]. Notably, TCR-CAR NK-92 cells, like T cells, redirected other killer cells [102].

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation for the SFB738, a network grant of the European Commission (H2020-MSCA-MC-ITN-765104-MATURE-NK) and in part by the Alfred und Angelika Gutermuth Stiftung and the Adolf-Messer Stiftung. Furthermore, we want to thank the colleagues from the Fraunhofer Cluster of Immune Mediated Diseases (IMD) for critical discussion regarding the manuscript.

References

- 1.Koehl U, Kalberer C, Spanholtz J, Lee DA, Miller JS, Cooley S, et al. Advances in clinical NK cell studies: donor selection, manufacturing and quality control. OncoImmunology. 2015 Nov;5((4)):e1115178. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1115178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta RS, Randolph B, Daher M, Rezvani K. NK cell therapy for hematologic malignancies. Int J Hematol. 2018 Mar;107((3)):262–70. doi: 10.1007/s12185-018-2407-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abate-Daga D, Davila ML. CAR models: next-generation CAR modifications for enhanced T-cell function. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2016 May;3:16014. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu Y, Tian ZG, Zhang C. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-transduced natural killer cells in tumor immunotherapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018 Feb;39((2)):167–76. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rezvani K, Rouce RH. The Application of Natural Killer Cell Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Cancer. Front Immunol. 2015 Nov;6:578. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C, Oberoi P, Oelsner S, Waldmann A, Lindner A, Tonn T, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered NK-92 Cells: An Off-the-Shelf Cellular Therapeutic for Targeted Elimination of Cancer Cells and Induction of Protective Antitumor Immunity. Front Immunol. 2017 May;8:533. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu E, Tong Y, Dotti G, Shaim H, Savoldo B, Mukherjee M, et al. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia. 2018 Feb;32((2)):520–31. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oei VY, Siernicka M, Graczyk-Jarzynka A, Hoel HJ, Yang W, Palacios D, et al. Intrinsic Functional Potential of NK-Cell Subsets Constrains Retargeting Driven by Chimeric Antigen Receptors. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 Apr;6((4)):467–80. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberschmidt O, Kloess S, Koehl U. Redirected Primary Human Chimeric Antigen Receptor Natural Killer Cells As an “Off-the-Shelf Immunotherapy” for Improvement in Cancer Treatment. Front Immunol. 2017 Jun;8:654. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glienke W, Esser R, Priesner C, Suerth JD, Schambach A, Wels WS, et al. Advantages and applications of CAR-expressing natural killer cells. Front Pharmacol. 2015 Feb;6:21. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonn T, Becker S, Esser R, Schwabe D, Seifried E. Cellular immunotherapy of malignancies using the clonal natural killer cell line NK-92. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2001 Aug;10((4)):535–44. doi: 10.1089/15258160152509145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maki G, Klingemann HG, Martinson JA, Tam YK. Factors regulating the cytotoxic activity of the human natural killer cell line, NK-92. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2001 Jun;10((3)):369–83. doi: 10.1089/152581601750288975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong JH, Maki G, Klingemann HG. Characterization of a human cell line (NK-92) with phenotypical and functional characteristics of activated natural killer cells. Leukemia. 1994 Apr;8((4)):652–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klingemann HG, Wong E, Maki G. A cytotoxic NK-cell line (NK-92) for ex vivo purging of leukemia from blood. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1996 May;2((2)):68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonn T, Schwabe D, Klingemann HG, Becker S, Esser R, Koehl U, et al. Treatment of patients with advanced cancer with the natural killer cell line NK-92. Cytotherapy. 2013 Dec;15((12)):1563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta RS, Rezvani K. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Expressing Natural Killer Cells for the Immunotherapy of Cancer. Front Immunol. 2018 Feb;9:283. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb;378((5)):439–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romanski A, Uherek C, Bug G, Muller T, Rossig C, Kampfmann M, et al. Re-Targeting of an NK Cell Line (NK92) with Specificity for CD19 Efficiently Kills Human B-Precursor Leukemia Cells. Blood. 2004;104:2747. Available from: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/104/11/2747. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romanski A, Uherek C, Bug G, Seifried E, Klingemann H, Wels WS, et al. CD19-CAR engineered NK-92 cells are sufficient to overcome NK cell resistance in B-cell malignancies. J Cell Mol Med. 2016 Jul;20((7)):1287–94. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011 Aug;3((95)):95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milone MC, O'Doherty U. Clinical use of lentiviral vectors. Leukemia. 2018 Jul;32((7)):1529–41. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suerth JD, Morgan MA, Kloess S, Heckl D, Neudörfl C, Falk CS, et al. Efficient generation of gene-modified human natural killer cells via alpharetroviral vectors. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016 Jan;94((1)):83–93. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olbrich H, Slabik C, Stripecke R. Reconstructing the immune system with lentiviral vectors. Virus Genes. 2017 Oct;53((5)):723–32. doi: 10.1007/s11262-017-1495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell RS, Beitzel BF, Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry CC, et al. Retroviral DNA integration: ASLV, HIV, and MLV show distinct target site preferences. PLoS Biol. 2004 Aug;2((8)):E234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suerth JD, Maetzig T, Galla M, Baum C, Schambach A. Self-inactivating alpharetroviral vectors with a split-packaging design. J Virol. 2010 Jul;84((13)):6626–35. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00182-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suerth JD, Maetzig T, Brugman MH, Heinz N, Appelt JU, Kaufmann KB, et al. Alpharetroviral self-inactivating vectors: long-term transgene expression in murine hematopoietic cells and low genotoxicity. Mol Ther. 2012 May;20((5)):1022–32. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boissel L, Betancur-Boissel M, Lu W, Krause DS, Van Etten RA, Wels WS, et al. Retargeting NK-92 cells by means of CD19- and CD20-specific chimeric antigen receptors compares favorably with antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. OncoImmunology. 2013 Oct;2((10)):e26527. doi: 10.4161/onci.26527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu Y, Yahr A, Huang B, Ayello J, Barth M, S Cairo M. Romidepsin alone or in combination with anti-CD20 chimeric antigen receptor expanded natural killer cells targeting Burkitt lymphoma in vitro and in immunodeficient mice. OncoImmunology. 2017 Jun;6((9)):e1341031. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1341031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coustan-Smith E, Mullighan CG, Onciu M, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Pei D, et al. Early T-cell precursor leukaemia: a subtype of very high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Feb;10((2)):147–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomes-Silva D, Srinivasan M, Sharma S, Lee CM, Wagner DL, Davis TH, et al. CD7-edited T cells expressing a CD7-specific CAR for the therapy of T-cell malignancies. Blood. 2017 Jul;130((3)):285–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-01-761320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomes-Silva D, Tashiro H, Srinivasan M, Lulla P, Brenner MK, Mamonkin M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Therapy for CD7-Positive Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:2642. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Png YT, Vinanica N, Kamiya T, Shimasaki N, Coustan-Smith E, Campana D. Blockade of CD7 expression in T cells for effective chimeric antigen receptor targeting of T-cell malignancies. Blood Adv. 2017 Nov;1((25)):2348–60. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raikar SS, Fleischer LC, Moot R, Fedanov A, Paik NY, Knight KA, et al. Development of chimeric antigen receptors targeting T-cell malignancies using two structurally different anti-CD5 antigen binding domains in NK and CRISPR-edited T cell lines. OncoImmunology. 2017 Dec;7((3)):e1407898. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1407898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen KH, Wada M, Pinz KG, Liu H, Lin KW, Jares A, et al. Preclinical targeting of aggressive T-cell malignancies using anti-CD5 chimeric antigen receptor. Leukemia. 2017 Oct;31((10)):2151–60. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen KH, Wada M, Firor AE, Pinz KG, Jares A, Liu H, et al. Novel anti-CD3 chimeric antigen receptor targeting of aggressive T cell malignancies. Oncotarget. 2016 Aug;7((35)):56219–32. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA approves Mylotarg for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. FDA News Release, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017 https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm574507.htm (accessed June 6, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheinberg DA, Lovett D, Divgi CR, Graham MC, Berman E, Pentlow K, et al. A phase I trial of monoclonal antibody M195 in acute myelogenous leukemia: specific bone marrow targeting and internalization of radionuclide. J Clin Oncol. 1991 Mar;9((3)):478–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter RB, Raden BW, Zeng R, Häusermann P, Bernstein ID, Cooper JA. ITIM-dependent endocytosis of CD33-related Siglecs: role of intracellular domain, tyrosine phosphorylation, and the tyrosine phosphatases, Shp1 and Shp2. J Leukoc Biol. 2008 Jan;83((1)):200–11. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godwin CD, Gale RP, Walter RB. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2017 Sep;31((9)):1855–68. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter RB. Investigational CD33-targeted therapeutics for acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2018 Apr;27((4)):339–48. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1452911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenderian SS, Ruella M, Shestova O, Klichinsky M, Aikawa V, Morrissette JJ, et al. CD33-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells exhibit potent preclinical activity against human acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2015 Aug;29((8)):1637–47. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Tao Z, Xu Y, Liu J, An N, Wang Y, et al. CD33-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells with Different Co-Stimulators Showed Potent Anti-Leukemia Efficacy and Different Phenotype. Hum Gene Ther. 2018 May;29((5)):626–39. doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rafiq S, Purdon TJ, Schultz L, Klingemann H, Brentjens RJ. NK-92 cells engineered with anti-CD33 chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) for the treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Cytotherapy. 2015;17((6)):S23. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Przespolewski A, Szeles A, Wang ES. Advances in immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Future Oncol. 2018 Apr;14((10)):963–78. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suck G, Linn YC, Tonn T. Natural Killer Cells for Therapy of Leukemia. Transfus Med Hemother. 2016 Mar;43((2)):89–95. doi: 10.1159/000445325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taussig DC, Pearce DJ, Simpson C, Rohatiner AZ, Lister TA, Kelly G, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005 Dec;106((13)):4086–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muñoz L, Nomdedéu JF, López O, Carnicer MJ, Bellido M, Aventín A, et al. Interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain (CD123) is widely expressed in hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2001 Dec;86((12)):1261–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tasian SK, Kenderian SS, Shen F, Ruella M, Shestova O, Kozlowski M, et al. Optimized depletion of chimeric antigen receptor T cells in murine xenograft models of human acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017 Apr;129((17)):2395–407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-736041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gill S, Tasian SK, Ruella M, Shestova O, Li Y, Porter DL, et al. Preclinical targeting of human acute myeloid leukemia and myeloablation using chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Blood. 2014 Apr;123((15)):2343–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-529537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klöß S, Oberschmidt O, Morgan M, Dahlke J, Arseniev L, Huppert V, et al. Optimization of Human NK Cell Manufacturing: Fully Automated Separation, Improved Ex Vivo Expansion Using IL-21 with Autologous Feeder Cells, and Generation of Anti-CD123-CAR-Expressing Effector Cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2017 Oct;28((10)):897–913. doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jurisic V, Srdic T, Konjevic G, Markovic O, Colovic M. Clinical stage-depending decrease of NK cell activity in multiple myeloma patients. Med Oncol. 2007;24((3)):312–7. doi: 10.1007/s12032-007-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernal M, Garrido P, Jiménez P, Carretero R, Almagro M, López P, et al. Changes in activatory and inhibitory natural killer (NK) receptors may induce progression to multiple myeloma: implications for tumor evasion of T and NK cells. Hum Immunol. 2009 Oct;70((10)):854–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Costello RT, Boehrer A, Sanchez C, Mercier D, Baier C, Le Treut T, et al. Differential expression of natural killer cell activating receptors in blood versus bone marrow in patients with monoclonal gammopathy. Immunology. 2013 Jul;139((3)):338–41. doi: 10.1111/imm.12082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maki G, Hayes GM, Naji A, Tyler T, Carosella ED, Rouas-Freiss N, et al. NK resistance of tumor cells from multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients: implication of HLA-G. Leukemia. 2008 May;22((5)):998–1006. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pittari G, Vago L, Festuccia M, Bonini C, Mudawi D, Giaccone L, et al. Restoring Natural Killer Cell Immunity against Multiple Myeloma in the Era of New Drugs. Front Immunol. 2017 Nov;8:1444. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams BA, Law AD, Routy B, denHollander N, Gupta V, Wang XH, et al. A phase I trial of NK-92 cells for refractory hematological malignancies relapsing after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation shows safety and evidence of efficacy. Oncotarget. 2017 Jul;8((51)):89256–68. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chu J, Deng Y, Benson DM, He S, Hughes T, Zhang J, et al. CS1-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered natural killer cells enhance in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against human multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2014 Apr;28((4)):917–27. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang H, Zhang W, Shang P, Zhang H, Fu W, Ye F, et al. Transfection of chimeric anti-CD138 gene enhances natural killer cell activation and killing of multiple myeloma cells. Mol Oncol. 2014 Mar;8((2)):297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lutz RJ, Whiteman KR. Antibody-maytansinoid conjugates for the treatment of myeloma. MAbs. 2009 Nov-Dec;1((6)):548–51. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.6.10029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tai YT, Dillon M, Song W, Leiba M, Li XF, Burger P, et al. Anti-CS1 humanized monoclonal antibody HuLuc63 inhibits myeloma cell adhesion and induces antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in the bone marrow milieu. Blood. 2008 Aug;112((4)):1329–37. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Einsele H, Schreder M. Treatment of multiple myeloma with the immunostimulatory SLAMF7 antibody elotuzumab. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016 Oct;7((5)):288–301. doi: 10.1177/2040620716657993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gogishvili T, Danhof S, Prommersberger S, Rydzek J, Schreder M, Brede C, Einsele H, Hudecek M. SLAMF7-CAR T cells eliminate myeloma and confer selective fratricide of SLAMF7+ normal lymphocytes. Blood. 2017;130:2838–2847. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-778423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, Zhang Y, Bnson D, Caligiuri M, Yu J. Abstract 4617: daratumumab combined with CD38(-) natural killer cells armed with a CS1 chimeric antigen receptor for the treatment of relapsed multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. 2017;77(13 Supplement):4617. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caruso HG, Hurton LV, Najjar A, Rushworth D, Ang S, Olivares S, et al. Tuning Sensitivity of CAR to EGFR Density Limits Recognition of Normal Tissue While Maintaining Potent Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res. 2015 Sep;75((17)):3505–18. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Visvader JE. Cells of origin in cancer. Nature. 2011;469:314. doi: 10.1038/nature09781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Newick K, Moon E, Albelda SM. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for solid tumors. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2016;3:16006. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmidts A, Maus MV. Making CAR T cells a solid option for solid tumors. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2593. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kailayangiri S, Altvater B, Meltzer J, Pscherer S, Luecke A, Dierkes C, et al. The ganglioside antigen G(D2) is surface-expressed in Ewing sarcoma and allows for MHC-independent immune targeting. Br J Cancer. 2012 Mar;106((6)):1123–33. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Esser R, Müller T, Stefes D, Kloess S, Seidel D, Gillies SD, et al. NK cells engineered to express a GD2 -specific antigen receptor display built-in ADCC-like activity against tumour cells of neuroectodermal origin. J Cell Mol Med. 2012 Mar;16((3)):569–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kailayangiri S, Altvater B, Spurny C, Jamitzky S, Schelhaas S, Jacobs AH, et al. Targeting Ewing sarcoma with activated and GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor-engineered human NK cells induces upregulation of immune-inhibitory HLA-G. OncoImmunology. 2016 Oct;6((1)):e1250050. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1250050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spurny C, Kailayangiri S, Altvater B, Jamitzky S, Hartmann W, Wardelmann E, et al. T cell infiltration into Ewing sarcomas is associated with local expression of immune-inhibitory HLA-G. Oncotarget. 2017 Dec;9((5)):6536–49. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Töpfer K, Cartellieri M, Michen S, Wiedemuth R, Müller N, Lindemann D, et al. DAP12-based activating chimeric antigen receptor for NK cell tumor immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2015 Apr;194((7)):3201–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reiter RE, Gu Z, Watabe T, Thomas G, Szigeti K, Davis E, et al. Prostate stem cell antigen: a cell surface marker overexpressed in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998 Feb;95((4)):1735–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lam JS, Yamashiro J, Shintaku IP, Vessella RL, Jenkins RB, Horvath S, et al. Prostate stem cell antigen is overexpressed in prostate cancer metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Apr;11((7)):2591–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Campbell KS, Colonna M. DAP12: a key accessory protein for relaying signals by natural killer cell receptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999 Jun;31((6)):631–6. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lanier LL, Corliss B, Wu J, Phillips JH. Association of DAP12 with activating CD94/NKG2C NK cell receptors. Immunity. 1998 Jun;8((6)):693–701. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Campbell KS, Yusa S, Kikuchi-Maki A, Catina TL. NKp44 triggers NK cell activation through DAP12 association that is not influenced by a putative cytoplasmic inhibitory sequence. J Immunol. 2004 Jan;172((2)):899–906. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hershkovitz O, Jivov S, Bloushtain N, Zilka A, Landau G, Bar-Ilan A, et al. Characterization of the recognition of tumor cells by the natural cytotoxicity receptor, NKp44. Biochemistry. 2007 Jun;46((25)):7426–36. doi: 10.1021/bi7000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gumá M, Angulo A, López-Botet M. NK cell receptors involved in the response to human cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;298:207–23. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27743-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gumá M, Angulo A, Vilches C, Gómez-Lozano N, Malats N, López-Botet M. Imprint of human cytomegalovirus infection on the NK cell receptor repertoire. Blood. 2004 Dec;104((12)):3664–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gumá M, Budt M, Sáez A, Brckalo T, Hengel H, Angulo A, et al. Expansion of CD94/NKG2C+ NK cells in response to human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts. Blood. 2006 May;107((9)):3624–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cosman D, Müllberg J, Sutherland CL, Chin W, Armitage R, Fanslow W, et al. ULBPs, novel MHC class I-related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity. 2001;14:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, Steinle A, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999 Jul;285((5428)):727–9. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kloess S, Huenecke S, Piechulek D, Esser R, Koch J, Brehm C, et al. IL-2-activated haploidentical NK cells restore NKG2D-mediated NK-cell cytotoxicity in neuroblastoma patients by scavenging of plasma MICA. Eur J Immunol. 2010 Nov;40((11)):3255–67. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Giannattasio A, Weil S, Kloess S, Ansari N, Stelzer EH, Cerwenka A, et al. Cytotoxicity and infiltration of human NK cells in in vivo-like tumor spheroids. BMC Cancer. 2015 May;15((1)):351. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1321-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Klöss S, Chambron N, Gardlowski T, Weil S, Koch J, Esser R, et al. Cetuximab Reconstitutes Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Secretions and Tumor-Infiltrating Capabilities of sMICA-Inhibited NK Cells in HNSCC Tumor Spheroids. Front Immunol. 2015 Nov;6:543. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Klöß S, Chambron N, Gardlowski T, Arseniev L, Koch J, Esser R, et al. Increased sMICA and TGFβ1 levels in HNSCC patients impair NKG2D-dependent functionality of activated NK cells. OncoImmunology. 2015 May;4((11)):e1055993. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1055993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu J, Song Y, Bakker AB, Bauer S, Spies T, Lanier LL, et al. An activating immunoreceptor complex formed by NKG2D and DAP10. Science. 1999 Jul;285((5428)):730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Upshaw JL, Arneson LN, Schoon RA, Dick CJ, Billadeau DD, Leibson PJ. NKG2D-mediated signaling requires a DAP10-bound Grb2-Vav1 intermediate and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase in human natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2006 May;7((5)):524–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chang YH, Connolly J, Shimasaki N, Mimura K, Kono K, Campana D. A chimeric receptor with NKG2D specificity enhances natural killer cell activation and killing of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2013 Mar;73((6)):1777–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen X, Han J, Chu J, Zhang L, Zhang J, Chen C, et al. A combinational therapy of EGFR-CAR NK cells and oncolytic herpes simplex virus 1 for breast cancer brain metastases. Oncotarget. 2016 May;7((19)):27764–77. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Del Zotto G, Marcenaro E, Vacca P, Sivori S, Pende D, Della Chiesa M, et al. Markers and function of human NK cells in normal and pathological conditions. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2017 Mar;92((2)):100–14. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schönfeld K, Sahm C, Zhang C, Naundorf S, Brendel C, Odendahl M, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor growth by clonal NK cells expressing an ErbB2/HER2-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Mol Ther. 2015 Feb;23((2)):330–8. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matsuo Y, Drexler HG. Immunoprofiling of cell lines derived from natural killer-cell and natural killer-like T-cell leukemia-lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2003 Oct;27((10)):935–45. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jochems C, Hodge JW, Fantini M, Fujii R, Morillon YM, 2nd, Greiner JW, et al. An NK cell line (haNK) expressing high levels of granzyme and engineered to express the high affinity CD16 allele. Oncotarget. 2016 Dec;7((52)):86359–73. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Klingemann H, Boissel L, Toneguzzo F. Natural Killer Cells for Immunotherapy - Advantages of the NK-92 Cell Line over Blood NK Cells. Front Immunol. 2016 Mar;7:91. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cooley S, Xiao F, Pitt M, Gleason M, McCullar V, Bergemann TL, et al. A subpopulation of human peripheral blood NK cells that lacks inhibitory receptors for self-MHC is developmentally immature. Blood. 2007 Jul;110((2)):578–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Faure M, Long EO. KIR2DL4 (CD158d), an NK cell-activating receptor with inhibitory potential. J Immunol. 2002 Jun;168((12)):6208–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Suck G, Odendahl M, Nowakowska P, Seidl C, Wels WS, Klingemann HG, et al. NK-92: an ‘off-the-shelf therapeutic’ for adoptive natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016 Apr;65((4)):485–92. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1761-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Boissel L, Betancur M, Wels WS, Tuncer H, Klingemann H. Transfection with mRNA for CD19 specific chimeric antigen receptor restores NK cell mediated killing of CLL cells. Leuk Res. 2009 Sep;33((9)):1255–9. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Uherek C, Tonn T, Uherek B, Becker S, Schnierle B, Klingemann HG, et al. Retargeting of natural killer-cell cytolytic activity to ErbB2-expressing cancer cells results in efficient and selective tumor cell destruction. Blood. 2002 Aug;100((4)):1265–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Walseng E, Köksal H, Sektioglu IM, Fåne A, Skorstad G, Kvalheim G, et al. A TCR-based Chimeric Antigen Receptor. Sci Rep. 2017 Sep;7((1)):10713. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11126-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]