Abstract

Background

Usher syndrome (USH) is a recessive inherited disease characterized by sensorineural hearing loss, retinitis pigmentosa, and sometimes, vestibular dysfunction. Although the molecular epidemiology of Usher syndrome has been well studied in Europe and United States, there is a lack of studies in other regions like Africa or Central and South America.

Methods

We designed a NGS panel that included the 10 USH causative genes (MYO7A, USH1C, CDH23, PCDH15, USH1G, CIB2, USH2A, ADGRV1, WHRN, and CLRN1), four USH associated genes (HARS, PDZD7, CEP250, and C2orf71), and the region comprising the deep-intronic c.7595-2144A>G mutation in USH2A.

Results

NGS sequencing was performed in 11 USH patients from Cuba. All the cases were solved. We found the responsible mutations in the USH2A, ADGRV1, CDH23, PCDH15, and CLRN1 genes. Four mutations have not been previously reported. Two mutations are recurrent in this study: c.619C>T (p.Arg207∗) in CLRN1, previously reported in two unrelated Spanish families of Basque origin, and c.4488G>C (p.Gln1496His) in CDH23, first described in a large Cuban family. Additionally, c.4488G>C has been reported two more times in the literature in two unrelated families of Spanish origin.

Conclusion

Although the sample size is very small, it is tempting to speculate that the gene frequencies in Cuba are distinct from other populations mainly due to an “island effect” and genetic drift. The two recurrent mutations appear to be of Spanish origin. Further studies with a larger cohort are needed to elucidate the real genetic landscape of Usher syndrome in the Cuban population.

Keywords: retinitis pigmentosa, sensorineural hearing loss, Usher syndrome, deaf-blindness, molecular genetics

Introduction

Usher syndrome (USH, OMIM 276900, OMIM 276905, OMIM 605472, ORPHA: 886) is the most prevalent deaf-blindness of genetic origin. It is a recessive inherited disease characterized by sensorineural hearing loss (HL), visual loss due to retinitis pigmentosa (RP), and, in some cases, vestibular dysfunction. Prevalence estimates range from 3.2 to 6.2/100,000 (Espinós et al., 1998; Keats and Corey, 1999).

Patients with USH are classified into three clinical subtypes (USH1, USH2, or USH3), based on the severity and progression of hearing impairment and the presence or absence of vestibular dysfunction. Usher syndrome type I (USH1) is the most severe type, characterized by severe to profound congenital sensorineural hearing loss, vestibular dysfunction, and prepubertal onset of RP eventually leading to legal blindness. USH2 is characterized by moderate to severe hearing impairment, normal vestibular function and later onset of retinal degeneration. USH3 displays progressive hearing loss, RP and variable vestibular phenotype (Saihan et al., 2009; Millán et al., 2010).

Currently, up to 13 genes have been associated with Usher syndrome: MYO7A, USH1C, CDH23, PCDH15, USH1G, and CIB2 are responsible for USH1, although the role of CIB2 in the Usher syndrome has recently been put on doubt (Booth et al., 2018). USH2A, ADGRV1, and WHRN are the three genes responsible for USH2, and the CLRN1 gene is the only one associated with USH3 cases to date. Besides, PDZD7 has been reported to behave as a modifier of the retinal phenotype in conjunction with USH2A, and a contributor to digenic inheritance with ADGRV1 (Ebermann et al., 2010). In addition, HARS was postulated as a novel causative gene of USH3, based on a mutation found in two patients (Puffenberger et al., 2012). Finally, mutations in CEP250 have been reported to cause cone-rod dystrophy, isolated RP and atypical forms of USH, characterized by early onset hearing loss and mild RP (Khateb et al., 2014; Fuster-García et al., 2018; Kubota et al., 2018).

In the last years, next generation sequencing (NGS) techniques have revolutionized the world of the molecular genetic diagnosis, allowing the whole genome, whole exome and targeted gene sequencing more feasible, and making easier, rapid and cost-effective the identification of disease genes and the underlying mutations. It has been especially useful in genetically heterogeneous diseases, such as hearing loss or retinal dystrophies (Choi et al., 2013; Fu et al., 2013; Mutai et al., 2013; Glöckle et al., 2014). We previously developed a targeted next generation sequencing method for Usher syndrome that proved to be highly efficient (Aparisi et al., 2014; Fuster-García et al., 2018).

Although the molecular epidemiology of the Usher syndrome and the distribution of mutations causing the disease among these genes has been well studied in Europe and United States, there is a lack of studies in other regions like Africa or Central and South America.

Here, we show for the first time a molecular landscape of the Usher syndrome in Cuba, and we provide as well a clinical description of all the cases.

Materials and Methods

Patients

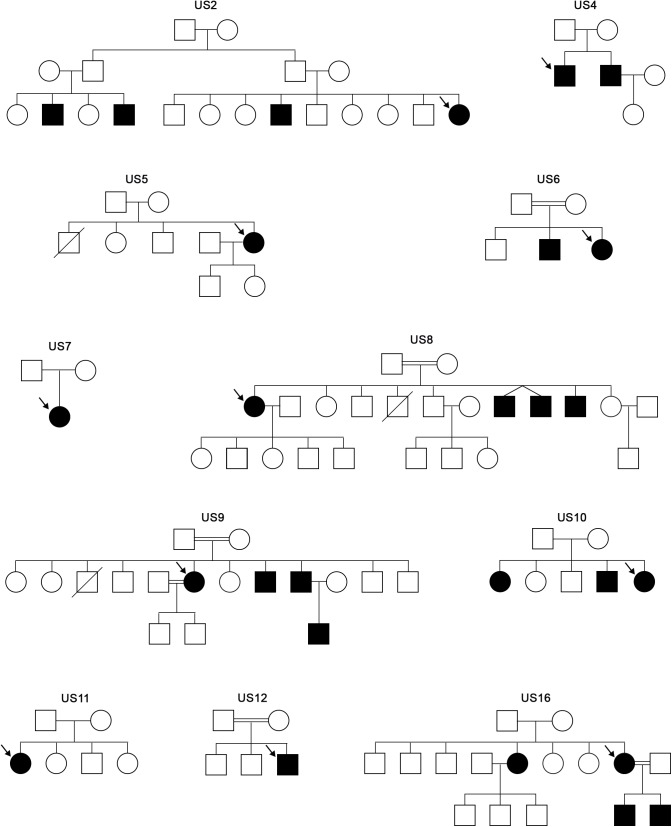

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out in a series of 11 families from Holguin (Cuba) with patients diagnosed clinically as Usher syndrome. All the 11 patients were Caucasian. The family trees of the families are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Family trees of the Usher families analyzed in this study. Arrows indicate the proband that was studied through the USH targeted panel.

The variables collected in this study were: age, sex, ethnicity, birthplace of the patients and their ancestors, consanguinity, age of onset HL and at diagnosis, HL degree, age of the first symptoms of RP and current clinical stage, and vestibular function. The institutional board of both the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital La Fe and the University of Holguín approved the study, according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and reviews. A survey assessed by the researchers was used in compliance after signing informed consent.

Ophthalmological examination included visual acuity, funduscopy, visual field test with Goldmann perimetry, and electroretinogram (ERG). The Audiological examination consisted of the vestibular function study through the caloric test and study of brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAEP).

Hearing loss evaluation was carried out using a radio audiometer MA31 (Grosses Klinisches Audiometer, Germany) in the Hospital “Vladimir Ilich Lenin.” The BAEPs were obtained in response to the monaural stimulation through TDH-39 hearing aids, with condensation clicks with a duration of 100 μsec and an intensity of 95 dB pSPL. The hearing loss of each affected individual was quantified by performing a complete tonal audiometry. Hearing loss was classified as: Mild (20–40 dB), moderate (40–70 dB), severe (70–90 dB), or profound (more than 90 dB).

Peripheral blood was obtained and DNA was extracted in the National Center for Medical Genetics in Havana, and sent to the University Hospital La Fe in Valencia (Spain).

Targeted Exome Sequencing Design

We designed a customized AmpliSeq panel using Ion AmpliSeq Designer tool from Thermo Fisher Scientific1 to generate the targeted library composed of all exons contemplated in all isoforms with 10 bp padding of the flanking intron regions, and the additional locus comprising the c.7595-2144A>G intronic mutation (Vaché et al., 2012). These target regions were covered by 810 amplicons of 125–175 bp length range, computing a total panel size of 147.95 kb. The designed panel (Table 1) included 14 genes, 10 USH causative genes (MYO7A, USH1C, CDH23, PCDH15, USH1G, CIB2, USH2A, ADGRV1, WHRN, and CLRN1) and four USH associated genes (HARS, PDZD7, CEP250, and C2orf71).

Table 1.

Details of the target region studied in this study.

| Chr | Gene/locus | Coding exons | Size (bp) | Number of amplicons | Design coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | ADGRV1 | 90 | 20721 | 181 | 99.4% |

| 1 | USH2A | 72 | 17043 | 134 | 98.9% |

| 10 | CDH23 | 73 | 11849 | 120 | 99.5% |

| 10 | PCDH15 | 43 | 8284 | 67 | 98.2% |

| 20 | CEP250 | 32 | 7969 | 58 | 100% |

| 11 | MYO7A | 51 | 7642 | 88 | 98.6% |

| 2 | C2orf71 | 2 | 3907 | 23 | 99.6% |

| 10 | PDZD7 | 17 | 3474 | 31 | 97.5% |

| 11 | USH1C | 29 | 3334 | 38 | 94.2% |

| 9 | WHRN | 14 | 2964 | 26 | 100% |

| 5 | HARS | 15 | 1790 | 14 | 100% |

| 17 | USH1G | 4 | 1446 | 12 | 100% |

| 3 | CLRN1 | 9 | 1051 | 9 | 100% |

| 15 | CIB2 | 7 | 684 | 8 | 95% |

| 1 | ∗chr1: 216064460-216064620 | – | 160 | 1 | 100% |

Chr, chromosome number. ∗Region of the USH2A PE (Pseudo-exon 40) where mutation c.7595-2144A>G is located. Targets are arranged according to the size of the covered region.

Sequence Enrichment and Next Generation Sequencing

The amplification of the targets was performed according to the Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for Ion Torrent sequencing. The sequencing was carried out with a theoretical minimum coverage of 500× either on the PGM or Proton system.

Variant Filtering and Analysis

The resulting sequencing data were analyzed with the Ion Reporter Software tool 2 in regards to the human assembly GRCh37 (also known as hg19). The annotated variants were filtered according to a Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) value ≤0.01, their annotation in the dbSNP3, their description in the Usher syndrome mutation database4 and the mutation type. Those disease-causing and suspected-to-be pathogenic variants were validated through conventional Sanger sequencing. For this, each DNA locus comprising a selected mutation was amplified by PCR with specific primers, and both forward and reverse strands were sequenced using the Big Dye 3.1 Terminator Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) after enzymatic PCR clean up with illustra ExoProStar 1-Step (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The purified sequence products were analyzed on a 3500xL ABI instrument (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The novel variants found in the cohort of probands were categorized based on the guidelines of the clinical and molecular genetics society5 and the Unknown Variants classification system (see text footnote 4) as pathogenic, probably pathogenic (UV4), possibly pathogenic (UV3), possibly non-pathogenic (UV2), and neutral (UV1), according to the type of mutation, bioinformatic predictions and segregation analysis. The four novel mutations were frameshift or nonsense mutations. Hence, they were automatically stated as pathogenic variants.

The annotation of the variants was performed according to following isoform reference sequences for each gene: MYO7A (NM_000260.3), USH1C (NM_153676), CDH23 (NM_022124.5), PCDH15 (NM_033056.3), USH1G (NM_173477), CIB2 (NM_006383.2), USH2A (NM_206933), ADGRV1 (NM_032119.3), WHRN (NM_015404), CLRN1 (NM_174878), HARS (NM_002109), PDZD7 (NM_001195263.1), CEP250 (NM_007186.4), and C2orf71 (NM_001029883.2).

MLPA Complementary Analysis

In order to ascertain if homozygous mutations could truly be masked cases of a large deletion comprising a heterozygous variant, we performed pertinent multiplex Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA; MRC-Holland) analysis for the only USH genes available, USH2A and PCDH15.

Results

Eleven index cases diagnosed of Usher syndrome from the province of Holguín, Cuba, were screened for mutations in the USH-associated genes of our home-designed panel.

Details of the genes, number of amplicons or coverage are described in Table 1.

Five cases were diagnosed of USH1, whereas four cases were USH2, and two cases were difficult to classify clinically. All the eleven cases were solved and the specific causative mutations can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genetic findings of the patients screened in this study, mutations, their effect on the protein, genes mutated, and nature of the mutations.

| Patient | Diagnosis | Mutations | Effect on protein | Gene | Type of mutation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US-2 | USH2 | c.15448_15449delCT | p.Leu5150Hisfs∗6 | ADGRV1 | Frameshift | This study |

| c.15448_15449delCT | p.Leu5150Hisfs∗6 | |||||

| US-4 | USH1 | c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | CDH23 | Splice site | Bolz et al., 2001 |

| c.7730_7734delTCAGT | p.Phe2577Serfs∗28 | Frameshift | This study | |||

| US-5 | USH1 | c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | CDH23 | Splice site | Bolz et al., 2001 |

| c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | |||||

| US-6 | USH1 | c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | CDH23 | Splice site | Bolz et al., 2001 |

| c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | |||||

| US-7 | USH1 | c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | CDH23 | Splice site | Bolz et al., 2001 |

| c.1624G>T | p.Glu542∗ | Nonsense | This study | |||

| US-8 | USH? | c.619C>T | p.Arg207∗ | CLRN1 | Nonsense | García-García et al., 2012 |

| c.619C>T | p.Arg207∗ | |||||

| US-9 | USH2 | c.2299delG | p.Glu767Serfs∗21 | USH2A | Frameshift | Liu et al., 1999 |

| c.2299delG | p.Glu767Serfs∗21 | |||||

| US-10 | USH2 | c.3661C>T | p.Gln1221∗ | PCDH15 | Nonsense | This study |

| c.3661C>T | p.Gln1221∗ | |||||

| US-11 | USH1 | c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | CDH23 | Splice site | Bolz et al., 2001 |

| c.4488G>C | p.Gln1496His | |||||

| US-12 | USH? | c.619C>T | p.Arg207∗ | CLRN1 | Nonsense | García-García et al., 2012 |

| c.619C>T | p.Arg207∗ | |||||

| US-16 | USH2 | c.1841-2 A>G | p.Gly614Aspfs∗6 | USH2A | Splice site | Jaijo et al., 2010 |

| c.1841-2 A>G | p.Gly614Aspfs∗6 |

Six families were consanguineous (54.5%) and another two were probably consanguineous (18.2%), since the parents come from the same small village. In total, the consanguinity or probable consanguinity in the cohort is over 70%.

Among the USH1 cohort, two pathogenic mutations were found in CDH23 (US-4, US-5, US-6, US-7, and US-11). In the USH2 cohort, two pathogenic mutations were found in ADGRV1 (US-2) and USH2A (US-16 and US-9), and PCDH15 (US-10). Regarding the unclassified cases, two mutations were found in CLRN1 (US-8 and US-12). Patient US-2, who carried the mutation c.15448_15449delCT in homozygosis in the ADGRV1 gene, carried the additional c.3242G>A (p.Arg1081Gln) missense mutation in CDH23 in heterozygous state, which is predicted to probably damaging according to PolyPhen-2 and benign as SIFT and PROVEAN.

Four mutations are reported in this study for the first time, namely c.15448_15449delCT (p.Leu5150Hisfs∗6) in ADGRV1, c.7730_7734delTCAGT (p.Phe2577Serfs∗28) in CDH23, c.1624G>T (p.Glu542∗) in CDH23, and c.3661C>T (p.Gln1221∗) in PCDH15.

Two mutations have been found in several USH alleles in this study. The p.Arg207∗ mutation in CLRN1 was found in homozygous state in two different families, both of them consanguineous. That means 18.2% of the total mutated alleles and 40% among the non-USH1 mutated alleles. Among the USH1 cases, p.Gln1496His accounted for 80% of the USH1 alleles (eight out of 10) and 36.4% of the total USH alleles. All the USH1 patients bear mutations in CDH23.

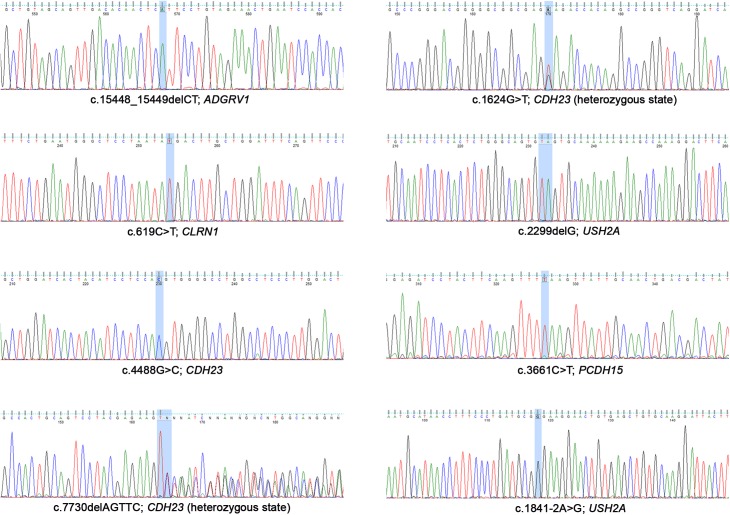

The sequences of each mutation are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Sanger electropherograms of the mutations detected in this study.

MLPA assays in the patients US-9, US-10, and US-16, with homozygous mutations in either USH2A or PCDH15, revealed no copy number variations.

Clinical Description

The clinical features of the 11 index patients are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinical features of the Cuban patients.

| Family | Consanguinity | Case (age) | Type | Audiological findings | Vestibular function | Ophthalmological findings |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | RP Dx | Clinical findings | ERG | ||||||

| US-2 | No | III:2 (76) | USH2 | Moderate SNHL; postlingual (adolescence); non-progressive | Normal | 8 yo | 14 yo | VF constriction (tunnel vision); pallor of the optic nerve; attenuated vessels; BLSP | Altered |

| US-4 | No | II:1 (42) | USH1 | Severe SNHL; prelingual | Altered | 18 yo | 27 yo | VF constriction (tunnel vision); pallor of the optic nerve; severe thinning of vessels; BLSP | Altered |

| US-5 | No | II:5 (58) | USH1 | Profound SNHL; prelingual | Altered | 9 yo | 21 yo | VF constriction (tunnel vision), right eye more affected; pallor of the optic nerve; thinning of the vessels; retinal and choroidal degeneration; BLSP in the posterior region | Abolished |

| US-6 | Yes (1st cousins) | II:2 (43) | USH1 | Severe SNHL; prelingual | Altered | 7 yo | 10 yo | Early onset RP; total amaurosis, no VF left; waxy pallor of the optic nerve; optic disc drusen; attenuated vessels; BLSP | Abolished |

| US-7 | Not reported ∗1000–2000 population | II:1 (10) | USH1 | Severe SNHL; prelingual; cochlear implant | Altered | 7 yo | 8 yo | VF and VA remain unaffected; mild thinning of the vessels; normal macula; fine colorless particles in the vitreous; few pigment accumulations | Altered |

| US-8 | Yes (1st cousins) | II:1 (80) | USH? | Moderate SNHL; postlingual (adolescence); progressive in the last 10 years | Normal | 10 yo | 16 yo | VF constriction (tunnel vision); low VA; attenuated vessels; pallor of optic nerve; macular edema and cysts; choroidal vascular fibrosis; BLSP | Abolished |

| US-9 | Yes (2nd cousins) | II:6 (61) | USH2 | Mild SNHL; postlingual (adulthood); progressive | Normal | 20 yo | 30 yo | VF constriction (mid-peripheral ring scotoma); attenuated vessels; pallor of optic nerve; BLSP | Abolished |

| US-10 | No | II:1 (59) | USH2 | Moderate SNHL; postlingual (adolescence); non-progressive | Normal | 19 yo | 28 yo | VF constriction (tunnel vision); thinning and atrophy of | Abolished |

| US-11 | Not reported ∗500–1000 population | II:1 (41) | USH1 | Profound SNHL; prelingual | Altered | 9 yo | 10 yo | VF constriction (tunnel vision), right eye more affected; waxy pallor of the optic nerve; macular degeneration, BLSP | Altered |

| US-12 | Yes (2nd cousins) | II:3 (47) | USH? | Severe SNHL; prelingual | Altered | 18 yo | 17 yo | VF constriction (tunnel vision), pallor of optic nerve; attenuated vessels; BLSP | Abolished |

| US-16 | Yes, in the third generation (1st cousins) | II:5 (50) | USH2 | Moderate SNHL; postlingual (adolescence); non-progressive | Normal | 14 yo | 26 yo | Severe VF reduction; severe thinning of vessels; pallor of optic nerve; BLSP | Abolished |

?, unclear USH category; SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss; NB, night blindness; yo, years old; Dx, diagnosis; VF, visual field; VA, visual acuity; ERG, electroretinogram. Asterisk indicates that the parents come from the same town with the specified number of inhabitants.

Mutation: c.15448_15449delCT (p.Leu5150Hisfs∗6) in ADGRV1

Proband of family US-2: The subject comes from a non-consanguineous family (father from Mexico and mother from Cuba) and displays a typical USH2 phenotype. She presented with a postlingual moderate non-progressive HL, no vestibular dysfunction and postpubertal onset of RP. This patient carries the mutation p.Leu5150Hisfs∗6 in ADGRV1 in homozygosis.

Mutation: c.619C>T (p.Arg207∗) in CLRN1

Proband of family US-8: Patient coming from a consanguineous family, harboring the mutation p.Arg207∗ in CLRN1 in homozygous state. She has a postlingual moderate HL with a progression in the last 10 years. This subject is 81 years old and the progression of the HL may be due to age-related hearing impairment. She noticed nyctalopia at 8 years old and the visual field was much reduced by the age of diagnosis. She did not report any balance problems.

Proband of family US-12: Patient carries the p.Arg207∗ mutation in CLRN1 in homozygous state. The family is also consanguineous, since the parents are second cousins. HL is postlingual and severe. RP signs were similar than those of US-8, yet with a later age of onset of symptoms and reduced visual field at age 24. ERG is abolished for this subject. In addition, the delayed walking onset and the reported difficulties in holding the head up as a baby suggest balance dysfunction.

Mutation: c.1841-2 A>G (p.Gly614Aspfs∗6) in USH2A

Proband of family US-16: The subject has a typical USH2A phenotype with a moderate postlingual non-progressive HL and typical RP of onset in the puberty.

Mutation: c.2299delG (p.Glu767Serfs∗21) in USH2A

Proband of family US-9: The patient harbors the most common mutation in USH2A patients of European origin, namely the c2299delG in USH2A. She displays a typical USH2 phenotype milder that US-16 with a mild postlingual HL and later onset of RP symptoms.

Mutation: c.3661C>T (p.Gln1221∗) in PCDH15

Proband of family US-10: This patient carries the p.Gln1221∗ mutation in PCDH15 in homozygous state. PCDH15 is associated to USH1 phenotype, however, this subject displayed postlingual moderate HL, normal vestibular function and relatively late-onset of RP.

Mutation: c.7730_7734delTCAGT (p.Phe2577Serfs∗28) in CDH23

Proband of family US-4: The patient is a compound heterozygote for the CDH23 mutations p.Phe2577Serfs∗28 and p.Gln1496His. He displays a typical USH1 phenotype with a prelingual, severe hearing loss RP onset al puberty and vestibular dysfunction.

Mutation: c.1624G>T (p.Glu542∗) in CDH23

Proband of family US-7: Compound heterozygote for the CDH23 mutations p.Glu542∗ and p.Gln1496His. Symptoms are distinctive of typical USH1 phenotype with a prelingual severe HL, early onset of RP and vestibular dysfunction.

Mutation: c.4488G>C (p.Gln1496His) in CDH23

Besides the compound heterozygotes US-4 and US-7, that carry p.Gln1496His together with other CDH23 mutations, three more patients carry the mutation in homozygous state, namely those from families US-5, US-6, and US-11. All of them displayed a typical USH1 phenotype.

Discussion

In this work, we report the first study in a cohort of Usher syndrome patients from Cuba. We found a total of eight mutations in 11 cases, four of which are novel (p.Leu5150Hisfs∗6 in ADGRV1, p.Phe2577Serfs∗28 and p.Glu542∗ in CDH23, and p.Gln1221∗ in PCDH15).

The presence in homozygosis of p.Gln1221∗ in PCDH15 led to a typical USH2 phenotype with a severe HL of postlingual onset, no vestibular dysfunction and late onset RP, and despite being the causative mutation a nonsense variant. Although it is not common, mutations in genes that usually lead to USH1 and cause a USH2 phenotype, and vice-versa, have been reported (Bonnet et al., 2011; Aparisi et al., 2014; Fuster-García et al., 2018).

The mutations c.1841-2A>G (p.Gly614Asp∗fs6) and c.2299delG (p.Glu767Serfs∗21) in USH2A have been reported many times in the literature as pathogenic in many populations.

Noteworthy, two mutations are recurrent in this study. The c.619C>T mutation (p.Arg207∗) in CLRN1 was described by García-García et al. and Licastro et al. almost simultaneously in two a priori unrelated Spanish families of Basque origin and one family of Italian origin, respectively (García-García et al., 2012; Licastro et al., 2012). This mutation was found in homozygous state in two Cuban families. In the first family reported by García-García et al., the only affected member carried the p.Arg207∗ mutation together with p.Tyr63∗. The patient displayed bilateral severe progressive sensorineural HL corrected with hearing aids and was a candidate for cochlear implantation. She showed a delay in gait development and a vestibular hyporeflexia and she displayed typical symptoms of RP since young. The onset of her RP was at 9 years old, including night blindness and peripheral visual loss. Fundus ophthalmoscopy showed pigmentary anomalies typical of RP with a visual acuity of 0.4 in both eyes and a rapid progression of the visual loss.

In the second family there were two affected sibs who were compound heterozygotes for p.Arg207∗ and p.Ile168Asn. They displayed very discordant phenotypes. One brother had a typical RP and normal speech acquisition and motor milestones. At 13 years old he displayed a progressive bilateral HL that ranged 79–80 dB in the last clinical examination, and the vestibular function was normal. The other brother presented with a typical RP as well, but displayed a prelingual severe HL that required deaf school education.

These findings illustrate the impressive wide spectrum of sensorineural hearing impairment in type and degree, and the high degree of intersubject and intrafamiliar variability due to CLRN1 mutations, as previously reported (Pennings et al., 2003).

The other mutation, c.4488G>C (p.Gln1496His) in CDH23, was described by Bolz et al. (2001) in a large Cuban family. That study allowed the identification of the CDH23 gene as responsible of Usher syndrome type 1. Although c.4488G>C is a missense mutation (p.Gln1496His), the G>C change affects the last exon nucleotide and computational predictions and in vitro studies support the hypothesis of a splicing alteration leading to a truncated protein (Bolz et al., 2001).

Additionally, c.4488G>C has been reported two more times in the literature in two unrelated families of Spanish origin showing a typical USH1 phenotype (Astuto et al., 2002; Oshima et al., 2008).

It is noteworthy that the frequency of the mutated genes varies significantly when compared to other countries. In most populations MYO7A is the most prevalent gene among USH1 patients accounting for about 50% of the cases, except in some endogamic populations (Roux et al., 2011; Le Quesne Stabej et al., 2012; Glöckle et al., 2014; Yoshimura et al., 2014; Bonnet et al., 2016; Dad et al., 2016; Eandi et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018). However, all the USH1 patients in this cohort carry mutations in CDH23. Furthermore, c.4488G>C accounts for 80% of USH1 alleles and no MYO7A mutations were detected in the cohort.

No conclusions can be obtained from the USH2 mutation distribution given the small size of the sample. Two out of the three clear USH2 patients are caused by mutations in USH2A, whereas the remaining is due to a mutation in ADGRV1. Both USH2A mutations have been reported many times in the literature, being c.2299delG the most frequent USH2 mutation in populations of European origin (Dreyer et al., 2000).

The frequency of Usher syndrome due to mutations in CLRN1 in our sample is 18% (two out of 11), considerably higher than the 5% or less in other populations. Usher syndrome resulting from mutations in CLRN1 is rare except in Finland and among the Ashkenazi jews, and its high frequency among USH3 patients in these populations is due to founder mutations (Joensuu et al., 2001; Ness et al., 2003). Here, the apparently high frequency of CLRN1 is attributable to the presence of another unique mutation that probably has a Spanish origin.

It must be remarked that most of the mutations found in this study are homozygous, yet it could be possible that these were in fact heterozygous variants in concurrence of a large deletion, even when consanguinity is at stake. MLPA could be performed for mutations in USH2A and PCDH15, but there is no kit available to analyze the other implicated genes ADGRV1, CLRN1, and CDH23.

Segregation analysis would also help to unveil this issue and also to confirm if the compound heterozygous mutations are indeed in trans and, thus, causative of the disease. However, the obtainment of DNA samples of the relatives was not available.

Although the sample size is very small, it is tempting to speculate that the gene frequencies in Cuba are distinct from other populations, mainly due to an “island effect” and genetic drift. Further studies with a larger sample comprising different geographical regions of Cuba are needed to elucidate the real genetic landscape of Usher syndrome in the Cuban population.

Ethics Statement

The institutional board of the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital La Fe and the University of Holguín, respectively, approved the study, according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and reviews.

Author Contributions

JM and AL conceived, designed, and supervised the study. AL provided the samples. ES did the clinical data curation. CF-G, GG-G, and BG-B performed the molecular experiments and analyzed the sequencing data. EA and TJ did the results validations. JM and GG-G obtained the funding. ES and CF-G wrote the initial manuscript. JM, AL, and GG-G reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer CG declared a past co-authorship with several of the authors TJ and JM to the handling Editor.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge the patients for their voluntary participation.

Funding. This work was financially supported by a grant of the Institute of Health Carlos III (ISCIII; Ref.: PI16/00539). CF-G is a recipient of a fellowship from the ISCIII (Ref.: IFI14/00021).

References

- Aparisi M. J., Aller E., Fuster-García C., García-García G., Rodrigo R., Vázquez-Manrique R. P., et al. (2014). Targeted next generation sequencing for molecular diagnosis of Usher syndrome. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 9:168. 10.1186/s13023-014-0168-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astuto L. M., Bork J. M., Weston M. D., Askew J. W., Fields R. R., Orten D. J., et al. (2002). CDH23 mutation and phenotype heterogeneity: a profile of 107 diverse families with Usher syndrome and non-syndromic deafness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71 262–275. 10.1086/341558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolz H., von Brederlow B., Ramírez A., Bryda E. C., Kutsche K., Nothwang H. G., et al. (2001). Mutation of CDH23, encoding a new member of the cadherin gene family, causes Usher syndrome type 1D. Nat. Genet. 27 108–112. 10.1038/83667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet C., Grati M., Marlin S., Levilliers J., Hardelin J.-P., Parodi M., et al. (2011). Complete exon sequencing of all known Usher syndrome genes greatly improves molecular diagnosis. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 6:21. 10.1186/1750-1172-6-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet C., Riahi Z., Chantot-Bastaraud S., Smagghe L., Letexier M., Marcaillou C., et al. (2016). An innovative strategy for the molecular diagnosis of Usher syndrome identifies causal biallelic mutations in 93% of European patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 24 1730–1738. 10.1038/ejhg.2016.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth K. T., Kahrizi K., Babanejad M., Daghagh H., Bademci G., Arzhangi S., et al. (2018). Variants in CIB2 cause DFNB48 and not USH1J. Clin. Genet. 93 812–821. 10.1111/cge.13170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B. Y., Park G., Gim J., Kim A. R., Kim B.-J., Kim H.-S., et al. (2013). Diagnostic application of targeted resequencing for familial nonsyndromic hearing loss. PLoS One 8:e68692. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dad S., Rendtorff N. D., Tranebjærg L., Grønskov K., Karstensen H. G., Brox V., et al. (2016). Usher syndrome in Denmark: mutation spectrum and some clinical observations. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 4 527–539. 10.1002/mgg3.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer B., Tranebjaerg L., Rosenberg T., Weston M. D., Kimberling W. J., Nilssen O. (2000). Identification of novel USH2A mutations: implications for the structure of USH2A protein. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 8 500–506. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eandi C. M., Dallorto L., Spinetta R., Micieli M. P., Vanzetti M., Mariottini A., et al. (2017). Targeted next generation sequencing in Italian patients with Usher syndrome: phenotype-genotype correlations. Sci. Rep. 7:115681. 10.1038/s41598-017-16014-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebermann I., Phillips J. B., Liebau M. C., Koenekoop R. K., Schermer B., Lopez I., et al. (2010). PDZD7 is a modifier of retinal disease and a contributor to digenic Usher syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 120 1812–1823. 10.1172/JCI39715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinós C., Millán J. M., Beneyto M., Nájera C. (1998). Epidemiology of Usher syndrome in Valencia and Spain. Commun. Genet. 1 223–228. 10.1159/000016167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q., Wang F., Wang H., Xu F., Zaneveld J. E., Ren H., et al. (2013). Next-generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of a Chinese patient cohort with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54 4158–4166. 10.1167/iovs.13-11672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster-García C., García-García G., Jaijo T., Fornés N., Ayuso C., Fernández-Burriel M., et al. (2018). High-throughput sequencing for the molecular diagnosis of Usher syndrome reveals 42 novel mutations and consolidates CEP250 as Usher-like disease causative. Sci. Rep. 8:17113. 10.1038/s41598-018-35085-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-García G., Aparisi M. J., Rodrigo R., Sequedo M. D., Espinós C., Rosell J., et al. (2012). Two novel disease-causing mutations in the CLRN1 gene in patients with Usher syndrome type 3. Mol. Vis. 183070–3078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckle N., Kohl S., Mohr J., Scheurenbrand T., Sprecher A., Weisschuh N., et al. (2014). Panel-based next generation sequencing as a reliable and efficient technique to detect mutations in unselected patients with retinal dystrophies. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 22 99–104. 10.1038/ejhg.2013.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaijo T., Aller E., García-García G., Aparisi M. J., Bernal S., Avila-Fernández A., et al. (2010). Microarray-based mutation analysis of 183 Spanish families with Usher syndrome. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51 1311–1317. 10.1167/iovs.09-4085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joensuu T., Hämäläinen R., Yuan B., Johnson C., Tegelberg S., Gasparini P., et al. (2001). Mutations in a novel gene with transmembrane domains underlie Usher syndrome type 3. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69 673–684. 10.1086/323610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keats B. J., Corey D. P. (1999). The usher syndromes. Am. J. Med. Genet. 89 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khateb S., Zelinger L., Mizrahi-Meissonnier L., Ayuso C., Koenekoop R. K., Laxer U., et al. (2014). A homozygous nonsense CEP250 mutation combined with a heterozygous nonsense C2orf71 mutation is associated with atypical Usher syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 51 460–469. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota D., Gocho K., Kikuchi S., Akeo K., Miura M., Yamaki K., et al. (2018). CEP250 mutations associated with mild cone-rod dystrophy and sensorineural hearing loss in a Japanese family. Ophthalm. Genet. 39 500–507. 10.1080/13816810.2018.1466338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Quesne Stabej P., Saihan Z., Rangesh N., Steele-Stallard H. B., Ambrose J., Coffey A., et al. (2012). Comprehensive sequence analysis of nine Usher syndrome genes in the UK National Collaborative Usher Study. J. Med. Genet. 49 27–36. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licastro D., Mutarelli M., Peluso I., Neveling K., Wieskamp N., Rispoli R., et al. (2012). Molecular diagnosis of Usher syndrome: application of two different next generation sequencing-based procedures. PLoS One 7:e43799. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Z., Hope C., Liang C. Y., Zou J. M., Xu L. R., Cole T., et al. (1999). A mutation (2314delG) in the Usher syndrome type IIA gene: high prevalence and phenotypic variation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64 1221–1225. 10.1086/302332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millán J. M., Aller E., Jaijo T., Blanco-Kelly F., Gimenez-Pardo A., Ayuso C., et al. (2010). An update on the genetics of usher syndrome, an update on the genetics of usher syndrome. J. Ophthalmol. 2011:e417217. 10.1155/2011/417217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutai H., Suzuki N., Shimizu A., Torii C., Namba K., Morimoto N., et al. (2013). Diverse spectrum of rare deafness genes underlies early-childhood hearing loss in Japanese patients: a cross-sectional, multi-center next-generation sequencing study. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 8:172. 10.1186/1750-1172-8-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness S. L., Ben-Yosef T., Bar-Lev A., Madeo A. C., Brewer C. C., Avraham K. B., et al. (2003). Genetic homogeneity and phenotypic variability among Ashkenazi Jews with Usher syndrome type III. J. Med. Genet. 40 767–772. 10.1136/jmg.40.10.767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima A., Jaijo T., Aller E., Millan J. M., Carney C., Usami S., et al. (2008). Mutation profile of the CDH23 gene in 56 probands with Usher syndrome type I. Hum. Mutat. 29 E37–E46. 10.1002/humu.20761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings R. J. E., Fields R. R., Huygen P. L. M., Deutman A. F., Kimberling W. J., Cremers C. W. (2003). Usher syndrome type III can mimic other types of Usher syndrome. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 112 525–530. 10.1177/000348940311200608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puffenberger E. G., Jinks R. N., Sougnez C., Cibulskis K., Willert R. A., Achilly N. P., et al. (2012). Genetic mapping and exome sequencing identify variants associated with five novel diseases. PLoS One 7:e28936. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux A.-F., Faugère V., Vaché C., Baux D., Besnard T., Léonard S., et al. (2011). Four-year follow-up of diagnostic service in USH1 patients. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52 4063–4071. 10.1167/iovs.10-6869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saihan Z., Webster A. R., Luxon L., Bitner-Glindzicz M. (2009). Update on Usher syndrome. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 22 19–27. 10.1097/wco.0b013e3283218807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T., Xu K., Ren Y., Xie Y., Zhang X., Tian L., et al. (2018). Comprehensive molecular screening in chinese usher syndrome patients. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59 1229–1237. 10.1167/iovs.17-23312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaché C., Besnard T., le Berre P., García-García G., Baux D., Larrieu L., et al. (2012). Usher syndrome type 2 caused by activation of an USH2A pseudoexon: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Hum. Mutat. 33 104–108. 10.1002/humu.21634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura H., Iwasaki S., Nishio S.-Y., Kumakawa K., Tono T., Kobayashi Y., et al. (2014). Massively parallel DNA sequencing facilitates diagnosis of patients with Usher syndrome type 1. PLoS One 9:e90688. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]