Abstract

Purpose

Psychiatric illness can pose serious risks to pregnant and postpartum women and their infants. There is a need for screening tools that can identify women at risk for postpartum psychosis, the most dangerous perinatal psychiatric illness.

Methods

This study used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and Rasch item response theory (IRT) models to evaluate the psychometric properties and construct validity of the Spanish language version of the 16-item Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16) as a screening tool for psychosis in a population of pregnant Peruvian women.

Results

The EFA yielded a four-factor model, which accounted for 44% of the variance. Factor 1, representing “unstable sense of self,” accounted for 22.1% of the total variance; Factor 2, representing “ideas of reference/paranoia,” for 8.4%; Factor 3, representing “sensitivity to sensory experiences,” accounted for 7.2%; and Factor 4, possibly representing negative symptoms, accounted for 6.3%. Rasch IRT analysis found that all of the items fit the model.

Conclusions

These findings support the construct validity of the PQ-16 in this pregnant Peruvian population. Also, further research is needed to establish definitive psychiatric diagnoses to determine the predictive power of the PQ-16 as a screening tool.

Keywords: Exploratory factor analysis, pregnant, prodromal questionnaire, psychosis, Rasch item response theory

Introduction

From 1990 to 2015, the global maternal mortality rate declined by 44% (WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, & United Nations, 2015). As maternal mortality rates around the global have fallen with improved access to medical care, psychiatric causes account for a greater proportion of total mortality. In fact, suicide is now the leading cause of maternal death in some countries (CEMD, 2001, 2004; Gelaye, Kajeepeta, & Williams, 2016; Oates, 2003). In most cases, maternal suicide is associated with serious mental illness, either psychosis or severe depression (CEMD, 2004; Oates, 2003).

Postpartum psychosis (PP) is a rare but devastating medical emergency affecting 0.1 to 0.2% of all pregnancies (Sit, Rothschild, & Wisner, 2006; VanderKruik et al., 2017). Each year there are more than 6,000 cases in the United States and 200,000 globally (Sit et al., 2006). One in 500 women who develop PP will die by suicide; this is 100-fold greater than the overall maternal suicide risk of 1:50,000 (CEMD, 2001). For women with histories of bipolar disorder or previous episodes of PP, the risk of PP is 30% (Jones & Craddock, 2001; Robling, Paykel, Dunn, Abbott, & Katona, 2000; Sit et al., 2006). Women with histories of major depression also face an elevated risk of PP, on the order of 2–23% (Di Florio et al., 2012; Mighton et al., 2016). In nearly half of cases, PP represents the first psychotic episode for the patient (Valdimarsdottir, Hultman, Harlow, Cnattingius, & Sparen, 2009). Three-quarters of patients will go on to experience further episodes outside the postpartum period, and most of these patients receive a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Bergink, Rasgon, & Wisner, 2016; Robling et al., 2000). PP usually occurs early, within 30 days after delivery (Bergink et al., 2016). The onset is rapid, so prompt intervention is needed to mitigate escalation of symptoms. With early intervention, which usually includes inpatient hospitalization, pharmacotherapy, and psychotherapy, three-quarters of patients will make a functional recovery within nine months (Burgerhout et al., 2017; Meltzer-Brody & Jones, 2015).

A screening instrument that could identify pregnant women at high risk for PP would thus be useful for preventing PP and its sequelae. Screening pregnant and postpartum women for depression has been found to be cost-effective for early diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression and psychosis (Wilkinson, Anderson, & Wheeler, 2017). This suggests that screening for psychosis, which is associated with greater morbidity and mortality, could be indicated from a public health standpoint.

Other studies have examined the validity of a number of screening instruments for identifying psychiatric illness in pregnant women. While these studies have attempted to identify women at risk for a range of postpartum psychopathology, they have primarily utilized depression screening instruments, including the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987; Quispel, Schneider, Hoogendijk, Bonsel, & Lambregtse-van den Berg, 2015), the Beck Depression Inventory (Holcomb, Stone, Lustman, Gavard, & Mostello, 1996), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Altshuler et al., 2008), and the Inventory of Depression Symptomatology (Brunoni et al., 2013). One study assessed the efficacy of using maternal demographics and exposure to stressful life events, in addition to the EPDS, to screen for a spectrum of psychiatric disorders in pregnancy, including depression and psychosis. Overall, the instrument had 82% sensitivity and 86% specificity. However, 25% of cases of psychosis were missed (Quispel et al., 2015). To the best of our knowledge, no one has examined the validity of the PQ-16 or any other versions of the prodromal questionnaire among pregnant women.

The 16-item prodromal questionnaire (PQ-16) is a brief version of the 92-item prodromal questionnaire, which has been validated for screening patients for prodromal and psychotic symptoms (Loewy, Bearden, Johnson, Raine, & Cannon, 2005). The PQ-16 consists of 9 items out of the perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations subscale, 5 items including unusual thought content/delusional ideas/paranoia, and 2 negative symptoms (Ising et al., 2012). The PQ-16 has demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients who are at high-risk for developing psychosis, and it is a brief and simple instrument. In a population seeking psychiatric services, one study found both sensitivity and specificity of 87% using a cutoff score of ≥6 (Ising et al., 2012). A study of a non-clinical population found a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 63%, using the same cutoff (Chen et al., 2014; Kline & Schiffman, 2014). A similar screening instrument for psychosis, the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B) is a 21-item assessment that has been validated in Spanish (Fonseca-Pedrero, Gooding, Ortuno-Sierra, & Paino, 2016).

The PQ-16 has not been previously studied in pregnant populations as a tool for predicting first episode psychosis in the postpartum period. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, item response theory (IRT) approaches have never been used to evaluate the validity of the PQ-16. The classic test theory (CTT) or traditional psychometric approaches often hide the heterogeneity that exists in each specific item. The Rasch IRT analysis is the most robust method to examine the measurement properties of rating scales (Hobart, Cano, Zajicek, & Thompson, 2007). The application of Rasch IRT models for analysis of the PQ-16 would make it possible to identify and thus reduce bias when using the instrument in novel cultural settings, thus increasing its validity. This study will use exploratory factor analysis and Rasch IRT models to evaluate the validity of the Spanish language version of the PQ-16 as a screening instrument for prenatal psychotic symptoms in a population of pregnant Peruvian women.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants in this cross-sectional study were women who received prenatal care at the Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal (INMP) from October 2014 through November 2015 and who enrolled in the ongoing Pregnancy Outcomes, Maternal and Infant Cohort Study (PrOMIS). The INMP is the primary reference establishment for maternal and perinatal care operated by the Ministry of Health of the Peruvian Government. It serves low-income women who are publicly-insured. In 2015, 18,512 women gave birth at INMP. Eligible participants were pregnant women who were at least 18 years of age, initiated prenatal care prior to 16 weeks of gestational age, and could speak and read Spanish. Pregnant women were excluded if they had intellectual disabilities, twins, fetal malformation or a history of chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, sepsis or renal failure. All participants provided written informed consent prior to interview. The institutional review boards of the INMP, Lima, Peru and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Office of Human Research Administration, Boston, MA, approved all procedures used in this study.

Our study population is derived from information collected from participants who enrolled in the PrOMIS cohort. During the study period, 2,068 participants completed the structured interview, approximately 81% of eligible women who were approached. Details of the study setting and data collection procedures have been described previously (Barrios et al., 2015). Briefly, each participant was interviewed in a private setting at INMP by trained research personnel using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was used to elicit information regarding maternal sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics, histories of childhood abuse and intimate partner violence, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and psychosis-like experiences (PLEs). Nine participants were excluded from the analysis described here because of missing or incomplete psychosis assessment. The final analysis included 2,059 participants.

Measures

The 16-item version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16) was used to assess the presence of attenuated psychotic symptoms (Ising et al., 2012). It was developed as a brief version of the 92-item Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-92) (Loewy et al., 2005). The PQ-16 is a self-report screening questionnaire that assesses lifetime symptoms of psychosis-like experiences (PLEs) on a two-point scale (true/false). PQ-raw scores, indicating number of PLEs endorsed, were summed by totaling the number of “true” responses. Women who had PQ-raw scores ≥ 6 were classified as at “high risk for psychosis.” For each endorsed experience, the PQ-16 then assesses the degree of distress caused by each item (0–3) on a Likert scale. PQ-total scores were summed by totaling the Likert scale distress ratings for each endorsed experience. Participants’ “average distress” was calculated by dividing each participant’s PQ-total by her PQ-raw score, to provide a measure of each participant’s average degree of distress per item endorsed. The average distress had a potential range of zero (for participants endorsing no PLEs) to 3 (for participants who marked “severe” on the distress scale for every endorsed PLE) (Kline et al., 2014). The PQ-16 has been found to be a useful screening instrument for psychosis with good psychometric properties among patients seeking mental health care (Ising et al., 2012). For this study, the PQ-16 was translated into Spanish by a team of bilingual Peruvian clinicians, including co-author SES. It was then back-translated into English and the process was repeated until there was agreement among the translators.

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item, depression-screening scale (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001; R. L. Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999). In our study, this questionnaire assessed nine depressive symptoms experienced by participants in the 14 days prior to evaluation. Each item was rated on the frequency of a depressive symptom. The PHQ-9 score was calculated by assigning a score of 0, 1, 2, or 3 to the response categories of “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day,” respectively.

The GAD-7 is a 7-item questionnaire developed to identify probable cases of GAD and measure the severity of GAD symptoms (Robert L Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006). The GAD-7 asks participants to rate how often they have been bothered by each of these 7 core symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Response categories are “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day,” scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

The PCL-C uses 17 items designed to assess posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DMS-IV) criteria (Weathers, 1991). Each item assesses PTSD symptoms experienced over the past month on a 5-point Likert scale, with a total score ranging from 17–85. The PCL-C has demonstrated internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity among both clinical and non-clinical populations (Wilkins, Lang, & Norman, 2011).

Maternal sociodemographic and other characteristics were categorized as follows: age (18–19, 20–29, 30–34, and ≥35 years); educational attainment (≤6, 7–12, >12 completed years of schooling); maternal ethnicity (Mestizo vs. others); marital status (married/living with partner vs. others); employment during pregnancy (employed vs. not employed); access to basics including food and medical care (very hard/hard/somewhat hard vs. not very hard); smoking prior to and during pregnancy (yes vs. no); alcohol consumption prior to and during pregnancy (yes vs. no); parity (multiparous vs. nulliparous ); planned pregnancy (yes vs. no); and gestational age at interviews (weeks).

Data Analysis

We first examined the frequency distributions of maternal characteristics according to psychotic risk status. We used Chi-square test when comparing categorical variables, and Student’s t test when comparing continuous variables. In addition, we reported mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for each item. We conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine the underlying constructs of the PQ-16. Prior to performing EFA, we assessed the suitability of the data for performing factor analysis. This assessment showed that it was appropriate to proceed with factor analysis (Bartlett test of sphericity, p value < 0.001; and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = 0.84). We conducted the EFA using principal component analysis with orthogonal rotation. Factors with eigenvalues > 1 were assumed to be meaningful and were retained for rotation. Rotated factor loadings of ≥ 0.4 were considered sufficient, while items with factor loadings ≥ 0.4 on more than one factor were considered cross loading.

Additionally, we performed a Rasch item response theory (IRT) analysis (Bond & Fox, 2015) to evaluate the extent to which items from the Spanish-language version of the PQ-16 questionnaire are reliable and valid in detecting PLEs in this population of Peruvian pregnant women. The Rasch IRT is a one-parameter logistic item response model used to determine the fitness and internal validity of screening instruments (Bond & Fox, 2015). The Rasch IRT model assumes that the items within the questionnaire are unidimensional, measure the same construct and are independent of one another. The first two assumptions are assessed by mean square infit and outfit statistics, which measure the difference in the expected and the actual responses. The infit statistic is a weighted mean square residual value, which is more sensitive to the unexpected response of an individual’s ability level (i.e., intensity level of PLEs). The outfit statistic is the usual unweighted mean square residual, which is more sensitive to unexpected observations or outliers. Values of infit mean square and outfit mean square should range from 0.6 to 1.4, and from 0.5 to 1.7, respectively (Linacre, 2017). Fit statistics outside these ranges indicate that an item has too much or too little variation in response patterns and should be considered for removal from the instrument to improve fit. In addition to the fit of the data and the model, we also evaluated the hierarchy of the item difficulties. We plotted the Item Characteristic Curve (ICC) for the PQ-16, a graphical representation of the expected probability of endorsing an item as a function of participants’ intensity level of PLEs. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2016) and R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015). The level of statistical significance was set at p values < 0.05, and all tests were two-tailed.

Results

Selected sociodemographic and reproductive characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 27.91 years (SD 6.28 years), and the mean gestational age was 11.09 weeks (SD 3.95 weeks). The majority of participants were Mestizo (80.5%), married (82.7%), and with >12 years of education (55.9%). Difficulty accessing basic needs, including food, was reported by 43% of participants, and 62.9% of pregnancies were unplanned. Approximately 27% of study participants were at high risk for psychosis. Characteristics of study participants by psychosis risk are also presented in Table 1. Overall, those at high risk of psychosis were more likely to have completed fewer years of education and have experienced child abuse and intimate partner violence. They were also more likely to report symptoms of depression and anxiety. One quarter of participants screened positively for depression on the PHQ-9. Of those, 39% were identified as high risk on the PQ-16. Thirty-two percent of participants screened positively for generalized anxiety (of those, 39% also had a positive PQ-16), and 31% met criteria for PTSD on the PCL-C (of those, 44% screened positively on the PQ-16).

Table 1.

Demographics characteristics of the study population according to psychosis risk status (N=2059)

| Characteristics | All Participants (N=2059) |

Low risk for psychosis (N=1490) |

High risk for psychosis b (N=569) |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) a | 27.91 (6.28) | 28.03 (6.32) | 27.62 (6.18) | 0.18 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–19 | 131 | 6.36 | 93 | 6.24 | 38 | 6.68 | 0.52 |

| 20–29 | 1144 | 55.56 | 815 | 54.70 | 329 | 57.82 | |

| 30–34 | 431 | 20.93 | 321 | 21.54 | 110 | 19.33 | |

| ≥35 | 353 | 17.14 | 261 | 17.52 | 92 | 16.17 | |

| Education (years) | |||||||

| ≤6 | 25 | 1.21 | 15 | 1.01 | 10 | 1.76 | <0.0001 |

| 7–12 | 876 | 42.54 | 592 | 39.73 | 284 | 49.91 | |

| >12 | 1150 | 55.85 | 877 | 58.86 | 273 | 47.98 | |

| Mestizo ethnicity | 1657 | 80.48 | 1223 | 82.08 | 434 | 76.27 | 0.002 |

| Married/living with a partner | 1703 | 82.71 | 1240 | 83.22 | 463 | 81.37 | 0.34 |

| Employed | 1020 | 49.54 | 759 | 50.94 | 261 | 45.87 | 0.04 |

| Difficulty paying for basics | 885 | 42.98 | 613 | 41.14 | 272 | 47.80 | 0.005 |

| Difficulty paying for medical care | 838 | 40.70 | 589 | 39.53 | 249 | 43.76 | 0.08 |

| Smoked prior to this pregnancy | 296 | 14.38 | 209 | 14.03 | 87 | 15.29 | 0.47 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 42 | 2.04 | 30 | 2.01 | 12 | 2.11 | 0.89 |

| Alcohol consumption prior to this pregnancy | 649 | 31.52 | 480 | 32.21 | 169 | 29.70 | 0.27 |

| Alcohol consumption during pregnancy | 109 | 5.29 | 74 | 4.97 | 35 | 6.15 | 0.27 |

| Nulliparous | 943 | 45.80 | 692 | 46.44 | 251 | 44.11 | 0.34 |

| Planned pregnancy | 785 | 38.13 | 577 | 38.72 | 208 | 36.56 | 0.36 |

| Gestational age (weeks) at interview a | 11.09 (3.95) | 11.09 (3.94) | 11.07 (3.98) | 0.89 | |||

| Childhood abuse | 817 | 39.68 | 523 | 35.10 | 294 | 51.67 | <0.0001 |

| Lifetime intimate partner violence | 504 | 24.48 | 307 | 20.60 | 197 | 34.62 | <0.0001 |

| PHQ-9a | 7.00 (4.37) | 6.43 (4.09) | 8.50 (4.71) | <0.0001 | |||

| GAD-7a | 5.24 (3.84) | 4.69 (3.66) | 6.68 (3.95) | <0.0001 | |||

| PCL-Ca | 23.72 (7.73) | 22.37 (6.56) | 27.27 (9.29) | <0.0001 | |||

Mean (Standard Deviation)

PQ-raw ≥6

For continuous variables, P-value was calculated using the Student’s t test; for categorical variables, P-value was calculated using the Chi-square test.

Abbreviations: PHQ-9, The Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item; PCL-C, PTSD CheckList – Civilian Version.

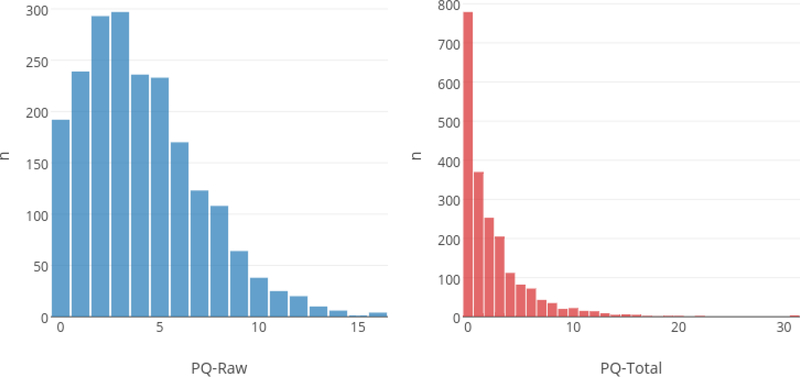

PQ-raw scores (PQ-raw) ranged from zero to 16, and PQ-total distress ratings (PQ-total) ranged from zero to 31. The mean PQ-raw was 4.05 (SD 2.96); and mean PQ-total was 2.53 (SD 3.37). The mean distress score per item endorsed (PQ-total divided by PQ-raw) was 0.44 (SD 0.49).

Table 2 shows the item characteristics for the PQ-16. Of the 16 items, the mean scores for PQ-raw ranged from 0.052 (#6: “When I look at a person, or look at myself in a mirror, I have seen the face change right before my eyes.”) to 0.693 (#16: “I feel that parts of my body have changed in some way, or that parts of my body are working differently than before”). Mean distress ratings for each item ranged from 0.363 to 0.997. The least distressing item was #3: “I sometimes smell or taste things that other people can’t smell or taste.” The most distressing item was #15: “I have had the sense that some person or force is around me, even though I could not see anyone.” In general, the fewer participants who endorsed an item, the more distressing it was. The distributions of the total PQ-raw and PQ-total are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Item characteristics of the PQ-16 scores among pregnant Peruvian women (N=2059)

| Items | PLEs |

Distress level |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 1. I feel uninterested in the things I used to enjoy. | 0.464 | 0.499 | 0.527 | 0.697 |

| 2. I often seem to live through events exactly as they happened before (de ja vu). | 0.229 | 0.420 | 0.590 | 0.693 |

| 3. I sometimes smell or taste things that other people can’t smell or taste. | 0.540 | 0.499 | 0.363 | 0.667 |

| 4. I often hear unusual sounds like banging, clicking, hissing, clapping or ringing in my ears. | 0.174 | 0.380 | 0.622 | 0.730 |

| 5. I have been confused at times whether something I experienced was real or imaginary. | 0.143 | 0.350 | 0.761 | 0.728 |

| 6. When I look at a person, or look at myself in a mirror, I have seen the face change right before my eyes. | 0.052 | 0.223 | 0.713 | 0.762 |

| 7. I get extremely anxious when meeting people for the first time. | 0.287 | 0.452 | 0.376 | 0.609 |

| 8. I have seen things that other people apparently can’t see. | 0.088 | 0.284 | 0.508 | 0.672 |

| 9. My thoughts are sometimes so strong that I can almost hear them. | 0.162 | 0.369 | 0.485 | 0.672 |

| 10. I sometimes see special meanings in advertisements, shop windows, or in the way things are arranged around me. | 0.268 | 0.443 | 0.372 | 0.580 |

| 11. Sometimes I have felt that I’m not in control of my own ideas or thoughts. | 0.206 | 0.405 | 0.685 | 0.698 |

| 12. Sometimes I feel suddenly distracted by distant sounds that I am not normally aware of | 0.174 | 0.379 | 0.506 | 0.612 |

| 13. I have heard things other people can’t hear like voices of people whispering or talking | 0.140 | 0.347 | 0.597 | 0.692 |

| 14. I often feel that others have it in for me. | 0.209 | 0.407 | 0.963 | 0.767 |

| 15. I have had the sense that some person or force is around me, even though I could not see anyone | 0.306 | 0.461 | 0.997 | 0.826 |

| 16. I feel that parts of my body have changed in some way, or that parts of my body are working differently than before | 0.603 | 0.489 | 0.534 | 0.742 |

Abbreviations: PLEs, psychosis like experiences

Figure 1.

Distributions for the PQ-16 scores among pregnant Peruvian women (N=2059)

EFA results for the PQ-16 are displayed in Table 3. The EFA yielded a four-factor model. Factor 1, representing “unstable sense of reality”, accounted for 22.1% of the total variance; Factor 2, representing “ideas of reference/paranoia”, accounted for 8.4%; Factor 3, representing “sensitivity to sensory experiences”, accounted for 7.2%; and Factor 4, which was difficult to characterize, accounted for 6.3%. Factor 4 included the following three items: #1: “I feel uninterested in the things I used to enjoy”; #2: “I often seem to live through events exactly as they happened before (de ja vu)”; #3: “I sometimes smell or taste things that other people can’t smell or taste.” Item #1 describes a symptom of depression, #2 suggests a supernatural experience, and #3 describes sensitivity to sensory experiences, like Factor 3.

Table 3.

Factor loadings in exploratory factor analysis of the PQ-16 scores among pregnant Peruvian women (N=2059)

| Factor loadings |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Unstable sense of reality | Ideas of reference/ paranoia | Sensitivity to sensory experiences | Other |

| 1. I feel uninterested in the things I used to enjoy. | 0.315 | 0.085 | −0.219 | 0.509 |

| 2. I often seem to live through events exactly as they happened before (de ja vu). | −0.027 | −0.003 | 0.159 | 0.717 |

| 3. I sometimes smell or taste things that other people can’t smell or taste. | 0.070 | 0.125 | 0.135 | 0.635 |

| 4. I often hear unusual sounds like banging, clicking, hissing, clapping or ringing in my ears. | 0.222 | 0.055 | 0.584 | 0.298 |

| 5. I have been confused at times whether something I experienced was real or imaginary. | 0.547 | −0.084 | 0.462 | 0.075 |

| 6. When I look at a person, or look at myself in a mirror, I have seen the face change right before my eyes. | 0.506 | −0.077 | 0.268 | −0.012 |

| 7. I get extremely anxious when meeting people for the first time. | 0.575 | 0.071 | −0.004 | −0.016 |

| 8. I have seen things that other people apparently can’t see. | 0.109 | 0.340 | 0.609 | 0.026 |

| 9. My thoughts are sometimes so strong that I can almost hear them. | 0.513 | 0.146 | 0.223 | 0.127 |

| 10. I sometimes see special meanings in advertisements, shop windows, or in the way things are arranged around me. | 0.137 | 0.558 | −0.351 | 0.226 |

| 11. Sometimes I have felt that I’m not in control of my own ideas or thoughts. | 0.651 | 0.208 | 0.055 | 0.076 |

| 12. Sometimes I feel suddenly distracted by distant sounds that I am not normally aware of. | 0.446 | 0.231 | 0.122 | 0.084 |

| 13. I have heard things other people can’t hear like voices of people whispering or talking. | 0.100 | 0.708 | 0.328 | −0.028 |

| 14. I often feel that others have it in for me. | 0.352 | 0.485 | 0.149 | −0.004 |

| 15. I have had the sense that some person or force is around me, even though I could not see anyone. | 0.089 | 0.733 | 0.035 | 0.124 |

| 16. I feel that parts of my body have changed in some way, or that parts of my body are working differently than before. | 0.471 | 0.150 | −0.095 | 0.154 |

| % of the variance | 0.221 | 0.084 | 0.072 | 0.063 |

Kaiser’s Measure of Sampling Adequacy: Overall MSA = 0.83654312

Bartlett’s test of sphericity: p<0.0001

PCA with varimax rotation

“The 16-item PQ consists of 9 items out of the perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations subscale, 5 items including unusual thought content/delusional ideas/paranoia, and 2 negative symptoms.” (Ising, H.K. et al., 2012. The validity of the 16-item version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16) to screen for ultra-high risk of developing psychosis in the general help-seeking population. Schizophrenia bulletin, 38(6), pp.1288–1296.)

Table 4 indicates the item fit summary statistics for the PQ-16 questionnaire using the Rasch IRT analysis. None of the items misfit the model according to criteria set a priori, with infit mean square values ranging from 0.84 to 1.14 and outfit mean square values ranging from 0.68 to 1.22. The item difficulties in logits ranged from −2.04 (the highest level of symptomatology) for item 16 to 1.93 (the lowest level of symptomatology) for item 6 (Table 4, Figure 2).

Table 4.

Item hierarchy and fit statistics of the PQ-16 under the Rasch Rating Scale Model among pregnant Peruvian women (N=2059)

| Items | Item Difficulty in Logits | Model SE | Infit a |

Outfit a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnSq | Zstd | MnSq | Zstd | |||

| 1. I feel uninterested in the things I used to enjoy. | −1.33 | 0.05 | 1.11 | 5.12 | 1.17 | 5.11 |

| 2. I often seem to live through events exactly as they happened before (de ja vu). | 0.00 | 0.06 | 1.14 | 4.44 | 1.22 | 3.91 |

| 3. I sometimes smell or taste things that other people can’t smell or taste. | −1.71 | 0.05 | 1.08 | 3.59 | 1.14 | 4.00 |

| 4. I often hear unusual sounds like banging, clicking, hissing, clapping or ringing in my ears. | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.93 | −1.94 | 0.86 | −2.21 |

| 5. I have been confused at times whether something I experienced was real or imaginary. | 0.67 | 0.07 | 0.88 | −2.96 | 0.76 | −3.34 |

| 6. When I look at a person, or look at myself in a mirror, I have seen the face change right before my eyes. | 1.93 | 0.10 | 0.86 | −1.82 | 0.71 | −2.05 |

| 7. I get extremely anxious when meeting people for the first time. | −0.37 | 0.05 | 1.05 | 1.77 | 1.06 | 1.37 |

| 8. I have seen things that other people apparently can’t see. | 1.30 | 0.08 | 0.86 | −2.54 | 0.68 | −3.29 |

| 9. My thoughts are sometimes so strong that I can almost hear them. | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.86 | −3.80 | 0.70 | −4.63 |

| 10. I sometimes see special meanings in advertisements, shop windows, or in the way things are arranged around me. | −0.26 | 0.05 | 1.11 | 3.89 | 1.09 | 1.93 |

| 11. Sometimes I have felt that I’m not in control of my own ideas or thoughts. | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.84 | −5.28 | 0.68 | −6.23 |

| 12. Sometimes I feel suddenly distracted by distant sounds that I am not normally aware of | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.92 | −2.19 | 0.83 | −2.59 |

| 13. I have heard things other people can’t hear like voices of people whispering or talking | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.86 | −3.43 | 0.73 | −3.80 |

| 14. I often feel that others have it in for me. | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.90 | −3.32 | 0.78 | −4.16 |

| 15. I have had the sense that some person or force is around me, even though I could not see anyone | −0.49 | 0.05 | 0.97 | −1.19 | 0.93 | −1.90 |

| 16. I feel that parts of my body have changed in some way, or that parts of my body are working differently than before | −2.04 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 2.42 | 1.04 | 1.02 |

| Mean | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.96 | −0.45 | 0.90 | −1.05 |

| SD | 1.04 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 3.40 | 0.19 | 3.46 |

Infit MnSq value and outfit MnSq value should range from 0.6 to 1.4, and from 0.5 to 1.7, respectively. SE, standard error, SD, standard deviation, MnSq, mean square, Zstd, z-standardized.

Figure 2.

Item Characteristic Curve of the PQ-16 under the Rasch Rating Scale Model among pregnant Peruvian women (N=2059)

Discussion

This study assessed the psychometric properties of the PQ-16 in a population of pregnant Peruvian women. We used PQ-raw ≥6 as the cutoff score for high risk of psychosis, as this cutoff has been established in other populations (Ising et al., 2012; Kline et al., 2014). Consistent with the existing literature (Bebbington et al., 2011; Salokangas et al., 2016; Souery et al., 2012), women experiencing financial stress, intimate partner violence, or other psychiatric symptoms were more likely to be identified as high-risk for psychosis. Other studies of the psychometric properties of the PQ-16 have been conducted in study populations seeking psychiatric care and thus have found higher PQ-raw scores and higher distress scores (Ising et al., 2012; Kline et al., 2014). While this study found an average PQ-raw score of 4.05 and an average distress score of 0.44, another study reported an average PQ-raw score of 8.67 and an average distress score of 2.73 (Kline et al., 2014). The lower average raw score and particularly the lower average distress score, which means that experiencing these symptoms was not as distressing, suggest that clinical interview is needed to better understand the significance of these symptoms as endorsed by pregnant Peruvian women.

The EFA identified four distinct factors within the PQ-16: “unstable sense of reality”; “ideas of reference/paranoia”; “sensitivity to sensory experiences”; and a fourth factor that was difficult to characterize. None of these factors correspond directly to any single subscale of the PQ-16. They all draw from at least two of the subscales; Factors 1 and 4 contain items from all three.

Factor 4 has features of sensitivity to sensory experiences, as well as supernatural experiences and depression. It includes one item from each of the three subscales of the PQ-16: “perceptual abnormalities,” “unusual thought content,” and “negative symptoms.” Symptoms such as flat affect, amotivation and social withdrawal, common symptoms of depression, are referred to as negative symptoms in patients with psychotic disorders. Item #1 (“I feel uninterested in the things I used to enjoy.”) describes anhedonia, which is a hallmark of depression and a negative symptom. Item #2 (“I often seem to live through events exactly as they happened before.”) describes de ja vu, which, in the European and North American context, is understood as an unusual perceptual experience. In Perú, there is a similar concept. However, this could also be understood to mean that the subject experiences her life as everything feeling the same, which could indicate lack of interest, anhedonia, or frank despair. Finally, Item #3 (“I sometimes smell or taste things that other people can’t smell or taste.”) would appear to fit better under Factor 3, “sensitivity to sensory experiences.” Consider, however, that change in appetite is often a symptom of depression. The item could be understood to mean, “things don’t taste the way they used to,” or “I don’t think things taste the same way to me as they do to other people,” which could impact appetite.

Thus, one possibility is that Factor 4 represents depression. The three items that loaded to Factor 4, #1, #2, and #3, were the 3rd, 7th, and 2nd most frequently endorsed items, respectively. Item #3 was endorsed by more than half of participants, and item #1 was endorsed by nearly half. In this study population, which was not presenting for psychiatric care, participants are more likely to have depression, which is both more common and less impairing, than to have a psychotic disorder. Indeed, 25% of participants screened positive for depression on the PHQ-9, and 10% screened positive on both the PQ-16 and the PHQ-9.

Given that the EFA demonstrated construct validity, the question of whether these items can be understood differently through a distinct cultural lens must be considered. It is also significant that 69% of women in this population report a history of childhood abuse (Barrios et al., 2015), as childhood adversities is associated with the development of psychosis later in life (Morgan & Gayer-Anderson, 2016). There is some evidence to suggest that while trauma is a risk factor of psychotic symptoms, these symptoms are more likely to be associated with a post-traumatic disorder than a primary psychotic disorder (Johnstone, 2011; Morgan & Gayer-Anderson, 2016). This may impact the type of symptoms endorsed and their diagnostic significance.

Some limitations of this study should be considered. First, the Rasch model is a one-parameter IRT model that assumes the item discrimination is the same for all items. Under this model, commonly endorsed items and rarely endorsed items have the same discriminatory power for women with low-level psychotic symptoms. Additionally, the Rasch IRT was performed for the yes/no responses for each item but not for the stress level score. Second, despite the fact that the study population was not presenting for psychiatric care, the identified rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD were significantly higher than what has been documented in the general population in the US (Alegria et al., 2008; Eaton et al., 1989). This may be explained in part by the high rate of trauma in this population but needs to be further explored, as it has implications for the generalizability of these findings. Finally, to determine the predictive value of this instrument as a screening tool for PP risk, the results will need to be compared with postpartum psychiatric diagnoses. The fact that 27% of participants met criteria for high risk, while the prevalence of PP is 0.1–0.2%, suggests that the cutoff score to be used for identifying PP risk might need to be adjusted based upon the findings of postpartum psychiatric assessments.

In summary, EFA and Rasch IRT analysis have supported the construct validity of the PQ-16 among pregnant Peruvian women. The Rasch IRT model has provided further evidence to the reliability and validity of the Spanish language version of the PQ-16 scale. Further research is needed to compare the PQ-16 findings to definitive psychiatric diagnoses in this population and then to reassess women in the postpartum period to determine the predictive power of the PQ-16 as a screening tool. Psychiatric illness can pose serious risks to pregnant and postpartum women and their infants. There is a need for screening tools that can identify women at risk for PP, the most dangerous perinatal psychiatric illness.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (T32-MH-093310 and R01-HD-059835). The NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors wish to thank the dedicated staff members of Asociacion Civil Proyectos en Salud (PROESA), Peru and Instituto Materno Perinatal, Peru for their expert technical assistance with this research.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: No disclosures.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research involving human participants: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Alegria M, Canino G, Shrout PE, Woo M, Duan N, Vila D, … Meng XL (2008). Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am J Psychiatry, 165(3), 359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Vitonis AF, Faraone SV, Harlow BL, Suri R, … Stowe ZN (2008). The Pregnancy Depression Scale (PDS): a screening tool for depression in pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health, 11(4), 277–285. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0020-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios YV, Gelaye B, Zhong Q, Nicolaidis C, Rondon MB, Garcia PJ, … Williams MA (2015). Association of childhood physical and sexual abuse with intimate partner violence, poor general health and depressive symptoms among pregnant women. PLoS One, 10(1), e0116609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, King M, Cooper C, Brugha T, … Jenkins R (2011). Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry, 199(1), 29–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergink V, Rasgon N, & Wisner KL (2016). Postpartum Psychosis: Madness, Mania, and Melancholia in Motherhood. Am J Psychiatry, 173(12), 1179–1188. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16040454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond T, & Fox C (2015). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (3 ed.). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brunoni AR, Benute GR, Fraguas R, Santos NO, Francisco RP, de Lucia MC, & Zugaib M (2013). The self-rated Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology for screening prenatal depression. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 121(3), 243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgerhout KM, Kamperman AM, Roza SJ, Lambregtse-Van den Berg MP, Koorengevel KM, Hoogendijk WJ, … Bergink V (2017). Functional Recovery After Postpartum Psychosis: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. J Clin Psychiatry, 78(1), 122–128. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CEMD. (2001). Why Mothers Die 1997–1999. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. [Google Scholar]

- CEMD. (2004). Why Mothers Die 2000–2002. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Wang L, Heeramun-Aubeeluck A, Wang J, Shi J, Yuan J, & Zhao X (2014). Identification and characterization of college students with attenuated psychosis syndrome in China. Psychiatry Res, 216(3), 346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, & Sagovsky R (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio A, Forty L, Gordon-Smith K, Heron J, Jones L, Craddock N, & Jones I (2012). Perinatal episodes across the mood disorder spectrum. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Kramer M, Anthony JC, Dryman A, Shapiro S, & Locke BZ (1989). The incidence of specific DIS/DSM-III mental disorders: data from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 79(2), 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Gooding DC, Ortuno-Sierra J, & Paino M (2016). Assessing self-reported clinical high risk symptoms in community-derived adolescents: A psychometric evaluation of the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief. Compr Psychiatry, 66, 201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelaye B, Kajeepeta S, & Williams MA (2016). Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: an epidemiologic review. Arch Womens Ment Health, 19(5), 741–751. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0646-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobart JC, Cano SJ, Zajicek JP, & Thompson AJ (2007). Rating scales as outcome measures for clinical trials in neurology: problems, solutions, and recommendations. Lancet Neurol, 6(12), 1094–1105. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70290-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb WL Jr., Stone LS, Lustman PJ, Gavard JA, & Mostello DJ (1996). Screening for depression in pregnancy: characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory. Obstet Gynecol, 88(6), 1021–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising HK, Veling W, Loewy RL, Rietveld MW, Rietdijk J, Dragt S, … van der Gaag M (2012). The validity of the 16-item version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-16) to screen for ultra high risk of developing psychosis in the general help-seeking population. Schizophr Bull, 38(6), 1288–1296. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone L (2011). Can traumatic events traumatise people? Trauma, madness, and ‘psychosis’ In Rapley M, Moncreiff J, & Dillon J (Eds.), De-medicalising misery: psychiatry, psychology, and the human condition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Jones I, & Craddock N (2001). Familiality of the puerperal trigger in bipolar disorder: results of a family study. Am J Psychiatry, 158(6), 913–917. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline E, & Schiffman J (2014). Psychosis risk screening: a systematic review. Schizophr Res, 158(1–3), 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline E, Thompson E, Bussell K, Pitts SC, Reeves G, & Schiffman J (2014). Psychosis-like experiences and distress among adolescents using mental health services. Schizophr Res, 152(2–3), 498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med, 16(9), 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM (2017). Ministep Rasch-Model Computer Programs (Version 3.93.0): Winsteps. Retrieved from http://www.winsteps.com/winman/copyright.htm

- Loewy RL, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, Raine A, & Cannon TD (2005). The prodromal questionnaire (PQ): preliminary validation of a self-report screening measure for prodromal and psychotic syndromes. Schizophr Res, 77(2–3), 141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, & Jones I (2015). Optimizing the treatment of mood disorders in the perinatal period. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 17(2), 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mighton CE, Inglis AJ, Carrion PB, Hippman CL, Morris EM, Andrighetti HJ, … Austin JC (2016). Perinatal psychosis in mothers with a history of major depressive disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health, 19(2), 253–258. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0561-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, & Gayer-Anderson C (2016). Childhood adversities and psychosis: evidence, challenges, implications. world psychiatry, 15(2), 93–102. doi: 10.1002/wps.20330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M (2003). Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull, 67, 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quispel C, Schneider TA, Hoogendijk WJ, Bonsel GJ, & Lambregtse-van den Berg MP (2015). Successful five-item triage for the broad spectrum of mental disorders in pregnancy - a validation study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 15, 51. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0480-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (2015). R software (Version 3.1.2). Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Robling SA, Paykel ES, Dunn VJ, Abbott R, & Katona C (2000). Long-term outcome of severe puerperal psychiatric illness: a 23 year follow-up study. Psychol Med, 30(6), 1263–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salokangas RK, Schultze-Lutter F, Hietala J, Heinimaa M, From T, Ilonen T, … Group E (2016). Depression predicts persistence of paranoia in clinical high-risk patients to psychosis: results of the EPOS project. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 51(2), 247–257. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1160-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. (2016). SAS Analytics Pro 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sit D, Rothschild AJ, & Wisner KL (2006). A review of postpartum psychosis. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 15(4), 352–368. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souery D, Zaninotto L, Calati R, Linotte S, Mendlewicz J, Sentissi O, & Serretti A (2012). Depression across mood disorders: review and analysis in a clinical sample. Compr Psychiatry, 53(1), 24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, & Williams JB (1999). Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. Jama, 282(18), 1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Löwe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdimarsdottir U, Hultman CM, Harlow B, Cnattingius S, & Sparen P (2009). Psychotic illness in first-time mothers with no previous psychiatric hospitalizations: a population-based study. PLoS Med, 6(2), e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderKruik R, Barreix M, Chou D, Allen T, Say L, Cohen LS, & Maternal Morbidity Working, G. (2017). The global prevalence of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 272. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1427-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FH, JA; Keane TM. (1991). PCL-C for DSM-IV (B. S. Divison, Trans.). Boston: National Center for PTSD - Behavioral Science Division. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, & United Nations. (2015). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, & Norman SB (2011). Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depress Anxiety, 28(7), 596–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson A, Anderson S, & Wheeler SB (2017). Screening for and Treating Postpartum Depression and Psychosis: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Matern Child Health J, 21(4), 903–914. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2192-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]