Abstract

We describe a family with a novel TNPO3 mutation of limb–girdle muscular dystrophy D2 (or LGMD 1F), a rare muscle disorder with autosomal dominant inheritance, first identified in an Italo-Spanish family where the causative defect has been found to be due to TNPO3 gene mutation, encoding transportin-3 protein (TNPO3). We present the clinical, histopathological and muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features in two patients, mother and son Hungarian origin, affected by LGMD D2 and correlate their clinical, MRI and histopathological data found in this condition. The affected son presented early pelvic girdle muscle weakness and thin muscles similar to a congenital myopathy; the mother was less compromised and had an LGMD phenotype. Muscle MRI showed a very pronounced lower limb muscle atrophy in both patients. The most relevant change obtained in the child muscle biopsy was a generalized type 1 fibre atrophy. The two patients presented the same mutation, but a different phenotype has been observed in mother and son.

Keywords: LGMD, TNPO3, transportinopathy

Introduction

The limb–girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMDs) are a group of genetically heterogeneous disorders characterized by predominant proximal muscle weakness with histopathological signs of progressive degeneration in muscle.1 The estimated incidence for all forms of LGMDs is 1:100,000, the clinical spectrum of LGMDs can vary from severe childhood forms with early loss of independent ambulation to milder adult-onset slowly progressive subtypes.2 They are divided into two major groups according to the hereditary trait: autosomal dominant (AD) forms that are indicated as LGMD type D, autosomal recessive (AR) forms that are classified as LGMD type R.1

One subtype of dominant LGMD is due to a mutation of TNPO3 gene (LGMD D2). This rare disorder was first identified in a large Italo-Spanish family3 in which patients presented proximal limb–girdle muscles weakness with variable onset ranging from 1 to 58 years.4 In this family, the disease locus has been mapped to chromosome 7q32.1-32.2.4 In 2013, using the next-generation sequencing (NGS) technique we identified a heterozygous frame-shift variant in the Transportin-3 (TNPO3) gene, that encodes Transportin-3.5,6 Transportin-3 is a nuclear protein member of the importin beta superfamily that imports serine–arginine-rich proteins into the nucleus, which is important for mRNA splicing. The clinical phenotype of LGMD D2 is characterized by severe weakness occurring first in the pelvic girdle muscle, then the shoulder girdle. In severe clinical cases, distal muscle weakness, winging scapulae, scoliosis and occasional facial weakness are present. No cognitive impairment or cardiac involvement has been observed (Table 1). Only in the juvenile-onset severe phenotype, respiratory involvement has been reported.7

Table 1.

The genetic and clinical data in limb–girdle muscular dystrophy type D2 (LGMD D2).

| LGMD D2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Disease symbol | LGMD D2 or 1F | |

| Gene symbol | TPNO3 | |

| Protein | Transportin-3 | |

| Chromosome locus | 7q32.1-q32.2 | |

| Inheritance | Autosomal dominant | |

| Principal clinical features | ||

| Early onset | Late onset | |

| Age | 5–15 years | 20–30 years |

| Phenotype | Similar to congenital myopathy | LGMD phenotype |

| Scapular winging | 30% | - |

| Dysphagia | 30% | - |

| Respiratory involvement | 30% | No |

| Finger contracture | Yes | No |

| Wheelchair bound age | 30 years | Over 30 years |

| Creatine kinase level | Mildly elevated | Slightly elevated |

| Muscle biopsy | Central nuclei, muscle fibres atrophy | Fibre degeneration atrophy, increased acid phosphatase |

| Quality of life | Mildly impaired | Slightly impaired |

We present a family with a congenital myopathy-LGMD phenotype in a child and his mother of Hungarian origin. A written informed consent was obtained from the mother (Patient 1) to publish the medical data and images of both her and her son (Patient 2).

Molecular analysis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), histopathological study, and a assessment of quality of life were performed in this new family of LGMD D2 and compared with previous findings in the first reported family.8,9

Case report

Patient 1

Patient 1, a 43-year-old woman of Hungarian origin, had two sons, the first, Patient 2, affected by LGMD D2, whereas the second, 10 years old, is healthy. Her parents were reported to be unaffected, but refused further DNA investigation.

The woman presented the first symptoms during her childhood: she started walking at 15 months and was always weak compared with peers. Electromyography (EMG) was performed at age 6 and myopathic alterations were found. During her second pregnancy at 30 years, she underwent a C-section, presented difficulty breathing and felt ‘paralyzed’. At age 41, she had elevated creatine kinase (CK) then she presented decreased muscle strength in the forearm and finger extensors and in the back muscles. She had also a proximal weakness primarily affecting proximal lower limb muscles.

On the last exam at age 43, she was able to walk, but had difficulty running. She complained of frequent falls, had difficulty keeping legs elevated or raising from the floor (Gower’s manoeuvre) and had to climb stairs using the handrail. She has reduced forced vital capacity (FVC) on spirometry (57%) and presented difficulty in her speech and swallowing. She had no cardiac involvement or cognitive impairment.

On last neuromuscular evaluation (IRCCS San Camillo Hospital, March 2018), specific clinical myopathic signs were observed such as pigeon toe–feet and kyphoscoliosis.

Muscle strength graded by Medical Research Council (MRC) scale10 showed severe muscle weakness of triceps and deltoid (2/5), neck flexors 3/5, neck extensors 4/5, biceps 4/5, wrist extensors 4/5 and pectoralis 3/5. In lower limbs, quadriceps and ileo-psoas had 3/5 score, semitendinous and semimembranous 4/5 and tibial anterior 3/5.

Patient 2

Patient 2, a 12-year-old child, presented weakness since the first year of life. He walked at 18 months but could not raise easily from the floor. At 10 years, he walked with a slow gait up to about 3 km, but then he felt fatigued and fell frequently. At 12 years, he walked only 50–100 m because he had become weaker in recent years. He could not rise from a laying position without grasping his knees and presented a weak grip. He had difficulty swallowing with moderate dysphagia. CK was normal. He did not present any respiratory or cardiac problem. He goes to school by car and has no learning difficulties.

On the last examination at IRCCS San Camillo Hospital in March 2018, he had a waddling gait, Gowers sign and climbed stairs using the handrail. He presented a myopathic face and moderate scapular winging. He was not able to stand from the floor and was unable to lift legs from the bed. He appeared thin, frail and weak (Figure 1A–C). Deep tendon reflexes were absent. Muscle strength assessed by MRC scale showed a pronounced weakness of triceps (2/5), deltoid (3/5), wrist extensor (3/5) and neck flexor muscles (3/5). In lower limbs, he had low MRC score in quadriceps, iliopsoas, semitendinous and semimembranous muscles (3/5).

Figure 1.

The child, 12 years old, was thin and weak and presented flat feet and short fingers with weak extensor indicis and carpi ulnaris muscles.

Quality of life

Quality of life (QoL) was assessed in patient 1 using an Individualized Neuromuscular Quality of Life (INQoL) test, validated in Italian11 and UK populations12 in a variety of muscular diseases. Patient 1 self-evaluation on the impact of muscle disease on her physical, psychological and social functioning in INQoL showed a mild impairment.

Laboratory exams

Muscle biopsy histopathology was performed in both patients according to standard procedures. A biopsy was performed in the child at 5 years of age and histochemistry and electron microscopy were diagnosed as compatible with congenital myopathy. The mother underwent three muscle biopsies at different ages (24, 36 and 38 years), that showed aspecific myopathic signs such as type 1 fibre predominance and changes in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide tetrazolium reductase (NADH-TR) stain similar to ‘cores’.

In March 2018 mother and son came for diagnostic purposes to the IRCCS San Camillo Hospital because transportinopathy was suspected and where clinical, biomedical, molecular, muscle MRI and a skin biopsy were performed. Muscle MRI was evaluated according to Mercuri scale. A skin biopsy was performed in patient 1 and fibroblast collected and cultured; the pellet of fibroblasts was sent to the Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine (TIGEM) for genetic analysis.

Histopathological studies

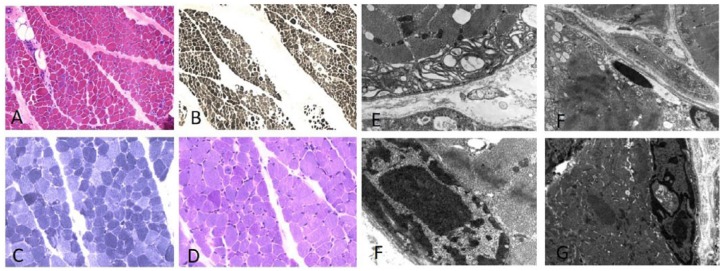

In the child muscle biopsy, morphologic findings by haematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining showed prominent fibre atrophy with acid ATPase stain (pH 4) with a 92% type 1 fibre predominance (Figure 2A and B) was observed. NADH-TR showed the abnormal presence of mitochondrial rims and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reaction detected focal glycogen accumulation in some fibres (Figure 2C and D). Ultrastructural analysis showed abnormal mitochondrial accumulation, myelinoid bodies and occasional cytoplasmic bodies; several abnormal nuclei had a fenestrated appearance (Figure 2E–G).

Figure 2.

Muscle biopsy of patient 2 shows diffuse fibre atrophy and some central nuclei with haematoxylin–eosin stain (A). Acid ATPase (pH 4) shows 92% type 1 fibre predominance (B). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide tetrazolium reductase (NADH-TR) showed abnormal nuclei and mitochondrial accumulation (C), periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain shows deposit of glycogen localized in some fibres (D). Ultrastructural analysis shows atrophic fibres with myelinoid body in subsarcolemmal position (E), cytoplasmatic body with mitochondrial alterations and vacuoles in nuclei (F). Abnormal dense nuclei with central vacuoles can be seen in (F, G).

Muscle MRI

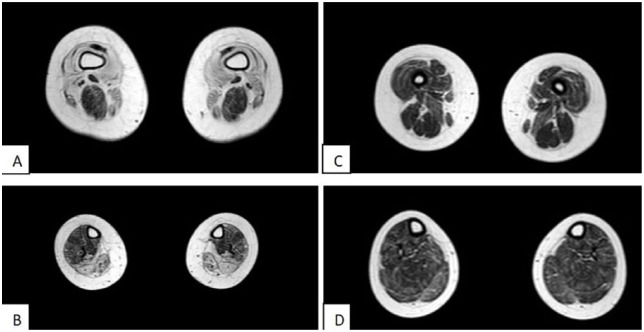

Muscle MRI was performed in both patients using a 1.5-T MRI scanner in T1-weighted sequences; muscle pattern was ranked according to Mercuri scale.13

Muscle MRI of patient 1 revealed marked atrophy, fatty tissue replacement in the pelvic girdle and anterior thigh muscles, especially in vastus lateralis, vastus medialis and intermedius, whereas in posterior thigh semitendinous and semimembranous muscles were relatively spared (Figure 3A). Posterior leg muscles were characterized by marked atrophy, in particular, soleus and gastrocnemius muscles were completely replaced by fatty infiltration (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in lower limbs in patients 1 and 2 according to the Mercuri score. (A) Slight atrophy was found in both legs and thighs of the female patient (mother of patient 2). Vastus lateralis, medialis and intermedius presented a 4 Mercuri score; semitendinous and semimembranous muscles were spared with Mercuri 1 score. (B) Advanced atrophy was present, in posterior compartment where soleus and gastrocnemius muscles were completely substituted with fatty infiltration. (C) Muscles of patient 1 were characterized by hypotrophy in the anterior thigh compartment. (D) Leg muscle mass was less compromised.

In patient 2, muscle MRI showed a pronounced hypotrophy of anterior thigh muscles, whereas leg muscles were preserved (Figure 3C and D).

Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from cultured fibroblasts of patient 1, analysed by whole exome sequencing (WES) and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. A heterozygous frameshift single base pair deletion c.2767delC (p.Arg923Aspfs*17) in exon 23 of TNPO3 gene was identified in both the mother and son genomic DNA. The number associated to the reference sequence is NM_012470.3: c.2767del; NP_036602.1: p.(Arg923Aspfs*17). This variant has not previously been reported and in silico predicted to be damaging (PoliPhen score 0.992; sensitivity 0.49; specificity 0.95).

The mutation identified is very similar and close to the first described mutation5 because it always involves the C-terminal therefore the final effect might be the same. The deletion of the base is in the codon immediately preceding to the other family variant (base position chr7: 128,597,310; NM_012470.3: c.2771delA, NP_036602.1p. (Ter924Cys)) and could be resulting in a longer protein (15 aa longer) than the wild type.

Discussion

Clinical, molecular, histopathological and radiological data, along with electron microscopy findings have been described so far only in a TNPO3 family.9,6

This dominant LGMD is characterized by clinical heterogeneity. The disorder has onset in childhood or adolescence, but also frequently in adulthood; in adults, it has a benign course compatible with a normal life. In the Italo-Spanish family, the main characteristic features and possible clues for diagnosis observed were abnormally long finger (arachnodactyly), pes cavus, Achilles retraction, and kyphoscoliosis (Table 1). On the other hand, the main clinical signs observed in Hungarian patients were the difficulty in lifting arms over the head, due to scapular winging, and inability to lift legs from the bed. Respiratory insufficiency might occur around 20–30 years in early onset cases:3 the mother had severe impairment of the respiratory function, while the son presented normal spirometry.

Gamez et al.3 in the biopsy of the Italo-Spanish LGMD patients observed diffuse atrophic fibres, basophilic cytoplasmic regions with spots of cytoplasmic lysosomal acid phosphatase reaction. By an ultrastructural study, Cenacchi et al.8 showed fibre atrophy, abnormal mitochondria accumulations with rare paracrystalline-like inclusions and autophagosomal vacuoles containing cytoplasmic debris and myeloid bodies. Similar histopathological and ultrastructural changes were observed in the biopsy of the son such as fibre atrophy, mitochondrial accumulation, myelinoid bodies, autophagosomal vacuoles and central fenestrated nuclei.

In the Italo-Spanish family, the mutation was identified as a single nucleotide deletion (c.2771delA, p.X924C, exon 22) in the TNPO3 gene not present in databases, which determines a nonstop mutation and consequently a 15-aminoacid extension of the C-terminus of the protein.5,6 Molecular analysis showed that the causative mutation of LGMD D2 in the Hungarian patients is due to a single nucleotide deletion in the termination codon of transportin 3 in exon 23 and might result in TNPO3 reduction. In this infantile-onset case, there was a congenital myopathy phenotype. The neurological examination highlighted this peculiar aspect: the child presented a severe phenotype with hypotonia and had thin and weak muscles.

Data derived from MRI study in our cases of this new family confirm a pattern of early onset and a late onset with proximal muscle involvement. The MRI changes in the mother at age 43 were more marked than in her son and were compatible with an LGMD phenotype.9

This AD disorder has been previously demonstrated to have incomplete penetrance in the original family.14 The lack of clinical signs in the parent(s) of patient 1 could be due to an incomplete penetrance rather than being a spontaneous mutation.

Transportin 3 orchestrates nuclear import of splicing factors and it is implicated in HIV resistance.15 The role of TNPO3 protein in muscle is unknown, but its involvement in nuclear import of splicing factors and protein involved in the RNA metabolism leads to a hypothesis about how TNPO3 mutation can cause LGMD D2.

The mutations abolish the stop codon, therefore the synthesis of a limited amount of TNPO3 protein with increased molecular weight is expected to occur in association with the mutation found in this family: a perturbed nuclear–myofibrillar interaction could result in myofibrillar disarray.

Regarding INQoL in our LGMD case, the results are consistent with those published by Peric et al.16 in 46 patients with LGMD. In both cases, the scores were similar, showing worse self-reported evaluation for weakness and fatigue and better results for social relationships and emotions. There was no effect on independent life.

The clinical features in these two patients of Hungarian family add new data to the spectrum of the clinical phenotypes so far described in LGMD D2. In particular, the clinical features appear severe in this family because the onset of symptoms was in the first year of life, including distal, axial, facial and bulbar weakness. However, onset in the first years of childhood,3,4,6,9 delayed motor skills,6 distal leg weakness,3,6,9 axial weakness,9 facial weakness3,9 and bulbar signs9 are also a feature of previously reported cases, and epigenetic and genetic modifiers are probably important in determining the onset, the characteristics and the progression of this disorder.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received grants from Conquistando Escalones Association, Telethon GGP14066, AFM, Eurobiobank and BBMRNR.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

ORCID iD: Corrado Angelini  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9554-8794

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9554-8794

Contributor Information

Corrado Angelini, IRCCS San Camillo Hospital, Via Alberoni 70, Venice, 30126, Italy.

Roberta Marozzo, IRCCS San Camillo Hospital, Venice, Italy.

Elena Pinzan, IRCCS San Camillo Hospital, Venice, Italy.

Valentina Pegoraro, IRCCS San Camillo Hospital, Venice, Italy.

Maria Judit Molnar, Institute of Genomic Medicine and Rare Disorders, Budapest, Hungary.

Annalaura Torella, TIGEM (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine), University at Campania, Naples, Italy.

Vincenzo Nigro, TIGEM (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine), University at Campania, Naples, Italy.

References

- 1. Straub V, Murphy A, Udd B; LGMD Workshop Study Group. 229th ENMC international workshop: limb girdle muscular dystrophies – nomenclature and reformed classification, Naarden, the Netherlands, 17-19 March 2017. Neuromuscul Disord 2018; 28: 702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magri F, Nigro V, Angelini C, et al. The Italian limb girdle muscular dystrophy registry: relative frequency, clinical features, and differential diagnosis. Muscle Nerve 2017; 55: 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gamez J, Navarro C, Andreu AL, et al. Autosomal dominant limb-girdle muscular dystrophy: a large kindred with evidence for anticipation. Neurology 2001; 56: 450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palenzuela L, Andreu AL, Gàmez J, et al. A novel autosomal dominant limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD 1F) maps to 7q32.1–32.2. Neurology 2003; 61: 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Torella A, Fanin M, Mutarelli M, et al. Next-generation sequencing identifies transportin 3 as the causative gene for LGMD1F. PLoS One 2013; 8: e63536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Melià MJ, Kubota A, Ortolano S, et al. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 1F is caused by a microdeletion in the transportin 3 gene. Brain 2013; 136: 1508–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Angelini C. Genetic Neuromuscular Disorders: A Case-based Approach. Berlin: Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cenacchi G, Peterle E, Fanin M, et al. Ultrastructural changes in LGMD1F. Neuropathology 2013; 33: 276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peterle E, Fanin M, Semplicini C, et al. Clinical phenotype, muscle MRI and muscle pathology of LGMD1F. J Neurol 2013; 260: 2033–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vlak M, Van Der Kooi E, Angelini C. Correlation of clinical function and muscle CT scan images in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Neurol Sci 2000; 21(5 Suppl.): S975–S977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sansone VA, Panzeri M, Montanari M, et al. Italian validation of INQoL, a quality of life questionnaire for adults with muscle diseases. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17: 1178–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vincent K, Vincent K, Carr J, et al. Construction and validation of a quality of life questionnaire for neuromuscular disease (INQoL). Neurology 2007; 68: 1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mercuri E, Pichiecchio A, Counsell S, et al. A short protocol for muscle MRI in children with muscular dystrophies. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2002; 6: 305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fanin M, Peterle E, Fritegotto C, et al. Incomplete penetrance in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 1F. Muscle Nerve 2015; 52: 305–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maertens GN, Cook NJ, Wang W, et al. Structural basis for nuclear import of splicing factors by human Transportin 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 2728–2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peric M, Peric S, Stevanovic J, et al. Quality of life in adult patients with limb-girdle muscular dystrophies. Acta Neurol Belg. 2018; 118(2): 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]